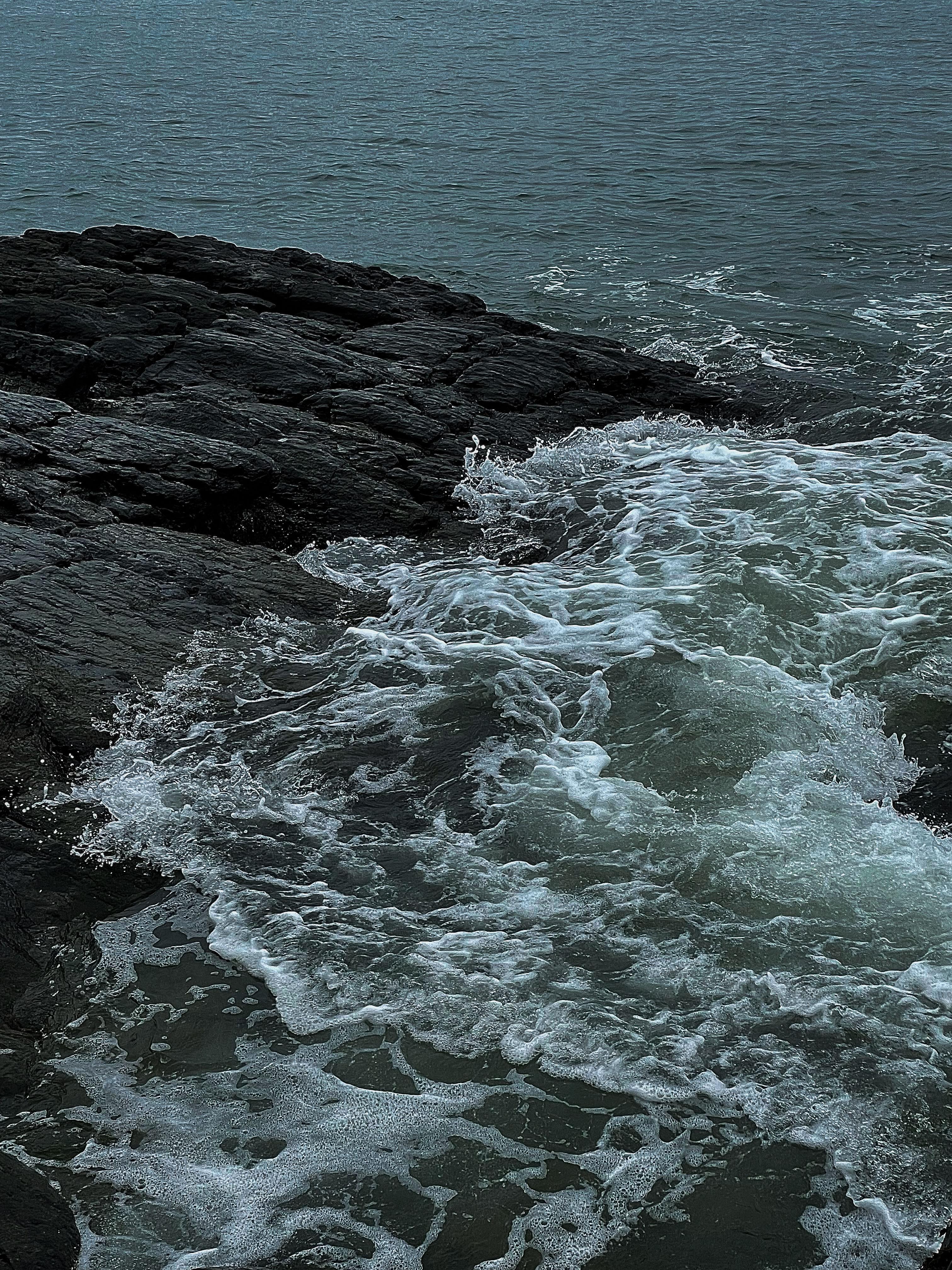

Cover Art by Liliana Stinson ‘23

Cover Art by Liliana Stinson ‘23

2022-2023

Virginia “Ginny”Hopkins ‘23

Liliana Stinson ‘23

Dr. Mary Edmonds <3

Sophie Croker Poole ‘23

Marisol Helms ‘23

Fish Leineweber ‘23

Han “Taylor” Xu ‘23

Shanming “Sunny” Xu ‘23

Zhaojiayi “Tina” Zhang ‘23

Ellery Blurton ‘24

Hongyi “Krystal” Lin ‘24

Catherine Nichols ‘24

Isabella Croker Poole ‘25

Sophia Hurst ‘25

CR ‘25

Annie Wells ‘25

The surdo beats

Undulating cries

Rushing energy to fill every muscle fiber

As dancing herds elephants across the floor their steps reverberating in your bones

Lights dance in time behind your eyes

As streets fill with color, life, light, and music serenades your mind

Porta-bandeiras breezing past

The brush of a Passista’s plumes

Against flushed skin

But as the night fades and the stars take their turn lighting the way the music smooths

Strings hum in time with the jungles thundering breath

Lyrics like the softly beating waves

Which blow the body into a gentle dance

Gliding through air and music

Until you take your leave

Cocooned by the sweet humid and draped netting

Drifted to sleep with the hum of life light and music

All wrapped into the gentle song of night

V Edwards ‘23 Samba

Nighttime Meals

Yiru “Angelina” Jin ‘23

Goonches live in the murky depths, where sunlight filters in past the silt and only shadows can be seen when you look up. Goonches can’t see the stars, but they don’t mind; they feel along the bottom with whiskers, their rubbery, slippery skin scraping along the sand. They don’t need to look up.

I look down at the water, mottled with algae and ugly, my reflection swirling in an oily sky. And then I see the goonch and it sees me. Its black eyes reflect the stars pale reminders of a larger existence and it said to me: we are one.

And I, lost in the wonders of the darkened world, lost from the doom of tomorrow, know deep in my aching heart that tonight will be beautiful.

Marisol Helms ‘23

I see you in cherry blossoms

I feel you in the wind

I see you in my future

You are my best friend

I see you in ponds

With ducks swimming peacefully

You make me feel comfortable

Like a leaf gliding dreamingly

I never saw you coming

And yet I see you everywhere

Like a wonderful surprise

Like the cool, autumn air

You break down my walls

And build up my hopes

Like the best mason

The world could ever know

If you ever get pulled from me

I hope the cherry tree never grows

I pray the ducks fly away

I hope the wind never blows

I see you in the morning

I feel you in my mind

I see you in my dreams

I feel you all the time

It’s a sound so familiar, so constant.

It’s a sound that raised me, celebrating my victories, surfacing my mistakes.

It’s the sound of my grandmother’s voice, feeling her shadow as the sun hangs low in the sky.

It’s a feeling so gentle, so loving.

It’s a feeling so moving, you can’t help but run screaming towards it, hoping you are one of the lucky ones it calls back to.

It’s the feeling of uncertainty, but the hope that you are right where you need to be.

Annie Wells ‘25 Luyi “Lucia” Yang ‘25

Luyi “Lucia” Yang ‘25

Catherine Nichols ‘24

Catherine Nichols ‘24

Eleanor Butterfield ‘25

Eleanor Butterfield ‘25

I was as hollow and empty as the spaces between stars. Of course I don’t really know what stars look like, I don’t know what much of anything looks like but I can imagine. I see five-pointed gold lights hanging from strips of ribbon pulled up everyday as the sun rises, I know what the sun looks like. I saw it once briefly, I thought it was beautiful. I’ve been cursed with a terrible memory, and I don’t remember much, but I do remember the sun.

Life in this bowl is very quiet, the kind of quiet that clings to a room, the quiet of the lonely or in my case the exceptional. I don’t have much company. I have a team of seven doctors who arrive promptly at 6:30 each day. They climb the worn marble stairs that are as shimmering as the day they were first laid down but betray their age with slight depressions. The doctors walk through halls filled with the bones of the long dead; it’s a museum of dead things.

They walk past the mammoths and the stegosauruses until they reach the main attraction, the thing that hundreds of people flock to see each day-me. My name is George and I am the world’s oldest living goldfish.

Ginny Hopkins ‘23In the midst of chaos and raging war, She caught a glimpse of him on the jungle floor. A soldier, new to uniform and strife, And in that moment, she glimpsed a new life.

Then the war ended and he went away, Leaving behind the girl he once had sworn. To love and cherish, each and every day, But now she was left with a heart forlorn.

Their eyes met in a fleeting, hopeful glance, And in that spark of hope, she found a light. A chance to leave behind the war’s cruel trance, And embark on a journey towards a brighter sight. They met beside a gentle, babbling stream, And danced to music only they could hear. Her heart filled with a hope she’d never dreamt, Of a life beyond the ruin and the fear.

She clung to hope that he would soon return, Her faith in him unyielding and strong. And even as her homeland began to burn, Her spirit refused to accept defeat’s song.

So she waited by the river at break of day, But only the setting sun’s glow would show. Then years slipped by, and hope began to fray, Yet she clung to a promise, made long ago.

In his embrace, she found a tranquil peace, Protected from the raging fires and flames. And in his smile, she found a comforting solace, Shielded from the world’s cruel games.

Until her heart shattered into countless shards, All wistful dreams now only dust and debris. As death swooped down with no regards, Leaving a heart that would no longer beat.

Their love blossomed, despite the war’s despair, As they held on to each other’s tender hands. He vowed to take her with him anywhere, Far from the chaos of her war-torn lands.

In Vietnam, a tale of tragic woe, Of a love that blossomed, then was slain. A reminder of the wounds that war can sow, Of promises made, but made in vain.

The war raged on, with battles fierce and grim, But in his words, she found a glimmer of hope. A promise of a life beyond war’s terrible hymn, And in his love, she found a reason to cope.

Amidst the weeping trees of that mournful land, Lies a girl whose love was crushed by a ruthless hand.

A symbol of the relentless pain that wars can bring, Of dreams and hopes that never once took wing.

Mia Swanson ‘24

I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning

Distance blurs the details

Creating a vague shape

One cannot ascertain what lies ahead when in fog

Not until they stand face to face

The distance between you and me cast a blue haze

Atmospheric perspective muted me

You could not make out my face

Twisted and panicked in a space too big

My tongue was a weak pitcher in vastness

Too much water between us

Too little strength in your arms and mine

Distance we could not close

Even if you knew how much life depended on it

Not before fatigue surrendered me to the depth

Nothing to have been done

Even if you knew the help that was needed

The distance between us was too far

Comprehension of my drowning wouldn’t have saved me

Not against an impossible expanse

Sophie Croker Poole ‘23

The land creatures call me Blue, but that is not my name. Their voices echo through the air like a prison guard’s whistle, “Blue, it’s show time!” I sink to the bottom of my tank, a small, cramped world of familiar white walls that I have known for 4,818 days. The white walls of my prison seem to close in on me, suffocating me with their stark emptiness. This tank is my home, but it’s also my prison. The voice belongs to one of my captors, who tower above, their gaze fixed on my every move like a predator stalking its prey. I am a prisoner, but not a willing one. I close my eyes, letting my body drift with the gentle currents that swirl around me, tuning out the calls of the land creatures in favor of the water’s soothing, silent symphony.

I have a name, but it is lost in the abyssal depths of the sea and carried away by the ethereal whispers of the wind. I was born in deep emerald green water far from the shore, and I took my first breath in the bitter cold of the star-specked night. A delicate nudge tickled the tip of my tail, and I flailed my flippers, spinning clumsily to confront the culprit. She looked like me - the color of the night sky, painted with soft spots of white - and she was Mother. I bounded forward and slipped under the warm blanket of her flipper that was the size of my entire body, and pressed myself against her warm white underbelly. The steady, even rhythm of her heartbeat beat in sync with my own, like a soothing duet that enveloped us in a cocoon of warmth and security. Beneath the blanket of twinkling stars, I was nestled in my mother’s loving arms as she bestowed upon me a name. My name is not just a simple word, but a symphony of sound, a melodic song that resonates deep within my being. Though I cannot recall the words or their meaning, the tune remains etched in my memory. It starts with a soft, mournful murmur, akin to the hushed whispers of the night. Slowly it builds, crescendoing into a trilling whistle, like the glittering of stars in the dark sky. The notes flow and intertwine with each other, mimic ing the undulating motion of the ocean’s tranquil waves, reaching toward the dazzling sunrise on the horizon.

The sea was my home, a boundless expanse of blue and green, where the sun never set and the water sparkled like diamonds. Mother engulfed me in the presence of others with a slippery black body and spots of blinding white. She called them Family, and Family meant warmth in freezing waters and safety from the sharp-toothed sharks that lurked below. We swam as one, darting and playing, our songs filling the air with a symphony of clicks and whistles. At night, we huddled close together, our bodies entwining for warmth and comfort. For days on end, I soared through the currents, my fins slicing through the water with effortless grace. The sea was a never-ending wonderland, each dive revealing new wonders and secrets. Alongside Mother and Family, I flew through the flowing currents of the unending ocean.

I have not seen Mother for 4,818 days. The floating beasts enslaved the wild wind and chased after Family as their spinning fins sliced through the water. Mother raced forward, her great tail splashing wildly through the thick currents, clearing a path for me to follow. The sea thrashed and wailed alongside panicked screams and frightened trills, several voices joining into one song of despair. The beast’s low rumble increased to a raging roar as its towering shadow caught the edge of my tail. A web of thin thread wrapped around my flailing fins, branding its claws into my supple skin and dragging me past the water’s surface and into the freezing air. I cried out for my mother one last time, but she was gone, her song drowned out by the sorrow of the sea. I do not remember the days that follow. In their place is an empty pit of despair.

The land creatures never again allow me to touch the sea. My name is lost to the icy wind, and my song is silenced under mourning waves. Now I am Blue, for Blue is all that remains. I spend my days staring blankly at familiar white walls, my only company the echoes of Family’s voices within the gray confines of my mind. The melody is a haunting reminder of everything I’ve lost. I long for the freedom of the open ocean, the taste of salt on my tongue, and the warmth of Mother’s loving embrace. My longing is meaningless. I am doomed to spend the rest of my days trapped in this prison, a lonely and forgotten creature, my name and my song lost forever in the abyssal depths of the sea.

Mia Swanson ‘24

An iced chai latte spills down your coat.

I’ve seen this before.

The light drink seeps into each fiber as you stare in lighthearted shock. You offer me a short sigh, tapping away with a napkin, brown on brown on brown.

I’ve been here before.

Chatter spirals in, moving back and forth and around, consuming, engulfing, tearing apart. I fall into it as it takes my head in its shaky hands, pulling my hair from my face. My eyes track the dark spots from the latte. Green on brown on brown.

This has happened before.

Your voice is muffled, swept into the chaos of the cafe and pulled into the tide, rocking and swaying and tugging in and out and in and out. My own phantom limbs wrap around your drink, your neck, my neck. My hands remain in my pockets; my eyes remain on the floor—still gray. Still moving gray.

I am a visitor to this moment. I stand outside of it.

You don’t notice when my eyes begin to focus again. Green returns to brown on brown, the voices of the customers press a smile onto my face as a parting gift from their long fingertips.

I am with you now.

My lips lose the feeling of their touch as my head returns from foreign grip and their nails slip from my hair once again. I hear you harshly. Your laugh pulls my head in and forces its own fingers into my mouth, my ears, the holes in my skull left behind by every lost thought. A spider that only I can see scuttles across the back of my neck and I look away from you. Green falls from blue in a landslide. My eyes rest on a fault line disturbed by the brittle touch of your laughter—a chasm in the gray tile.

I am here now.

The pull of your presence forces clouds around the edges of my consciousness, an approaching fog that leaves no choice but to focus on what is right in front of me. In a blurry haze that begs for a different sharp touch, I meet your hands. I cannot yet meet your eyes for fear of falling, but I meet the ground beneath my feet with quiet acquiescence as it builds itself back up against the soles of my shoes.

The walls cool their temper and the earthquake that never was falls silent. Your coat is dry now. I track the napkin one last time as you throw it into the trash, green on brown then nothing at all.

Catherine Nichols ‘24

Window & Peg Sophia Hurst ‘24

Window & Peg Sophia Hurst ‘24

Luyi “Lucia” Yang ‘24

Luyi “Lucia” Yang ‘24

Luyi “Lucia” Yang ‘25 and Shijun “Jessica” Ge ‘23

Luyi “Lucia” Yang ‘25 and Shijun “Jessica” Ge ‘23

Luyi “Lucia” Yang ‘25 and Shijun “Jessica” Ge ‘23

Holdyourbreath.Holdyourbreath,it’sfine,justbequiet,berealquiet.

Your hand is shaking so badly that your rings knock against the floor board, clatter clatterclatter,and you have to move to curl your arms in on yourself. But no, that’s not right, that’s not smart, because what if you look under the bed and you’re not ready No. Not you. It .

There’s twins at your school. Brother and sister, paternal, but the bond must still be the same. You remember wishing that you’d had a twin, but an identical one, to make it more interesting. To have a best friend for life. From birth until death.

Forlife.‘Tilldeath.But you’re an only child.

A whirring sound shatters the silence, deafening in the unnatural quiet. It’sthefrontdoorlockbeingdeactivated.

Your body reacts of its own accord, flooded with enough relief to drown you. Your blood rushes in your ears, thankGodsomeone’shome.And in spite of the adrenaline still burning in your bloodstream, shaking your limbs and pounding your heart, you twitch involuntarily, force of habit momentarily overruling force of nature as you prepare to slide out from beneath the bed.

The whirring stops. The apartment is hurled back into terrible silence. You freeze where you lay, shoulder and hip pressed up uncomfortably against the floor. The edge of the carpet is digging into your hip, acutely painful, but you don’t move. Whatareyou doing?

The door creaks open. It’s so loud, like fingernails raking down your eardrums. You squeeze your eyes shut. Your whole body’s trembling now, and your throat feels tight and painful. Every breath you release feels like a solid mass. You’re not ready to die.

The door shuts. You didn’t hear anybody come in. Maybe you’re safe. Maybe it was a fluke. Maybe it’s the police, doing routine checks, or a neighbor—

The floorboards of the hallway shriek with the weight of a body. You force your eyes open, staring out of the crack between the floor and your blankets. Your hip is throbbing, chest aching, eyes stinging. You don’t want to die.

There’s a shadow in the doorway, the silhouette of two feet. Youshould’veshutthedoor. It’s so dark, so quiet, and you can’t even begin to tell who those feet belong to. Your breath squeezes through your throat, threatening a whimper, and you hold your breath. Holdon,holdon,you’refine,everything’sfine—

The feet step into your room. Either they’re absolutely silent, or your heart is beating too frantically for you to really tell. Thisisit.Thisiswhatitfeelslike,huh? You’re about to die. Your life doesn’t flash before you. All you can think about is the school literary magazine, how you didn’t make it onto the editor’s board. Youshould’vetriedharder. Goddammit.

Another step. You can’t even feel the floor vibrating. It’sokayit’sokayit’sokayjustholdon it’sokayit’sokayit’sokayand they’re so close now, how did they get so close, how didn’t you hear it—

The sound that escapes your throat is accidental. Your ears are ringing now, and your hands are shaking so hard that you can’t really feel them anymore. You think you might be crying.

“Please,” you whisper, it’sokayholdonit’sokayit’sfineand a hand is gripping onto your blankets now, the only thing shielding you from whatever horror is waiting just inches away, and you recognize that ring on the middle finger. Even in the dark, paralyzed by fear, you would recognize your class ring anywhere. Youknowthem,youknowthem, breathe,it’sokay

And now there are two blue eyes staring at you, piercing and flat and terrifyingly familiar. Even in the dark, paralyzed by fear, you recognize your own face.

You shut your eyes. Sothisiswhatitfeelslike,huh?

And then you’re gone.

Fish Leineweber ‘23 Color Zhaojiayi “Tina” Zhang ‘23

Color Zhaojiayi “Tina” Zhang ‘23

Fire had always scared her. Her nights, suffocated by figments of smoke Running down the halls carpeted in flame; The groaning steps always moments away from catching her in its desperate grasp And never letting go.

Drowned.

A portrait of a dining room eaten alive is the only thing that stopped her Before she swam towards the door.

She used to light matches with oven mitts, Dousing each in a jar of water before the flame could kiss the candle’s wick. A line of blackened matches marching across the dining room table; A little girl made commander of this army

Manifested by fear

Back then, the fiery table was only a thought: A low hum from a wrought chandelier— Her heat could warp its wires with just a flick of the wrist And a matchbox.

The taste of the marble air above the gas stove— Oh how she wanted to lick the fumes from her fingertips. It didn’t take long for her to yearn for the warmth of the stars And long exploded suns.

But her plans, ingrained in the muddled irises of her eyes, Would offer no respite

When the candles tipped with a fiery grin Wax pooling upon the carpet, Broken glass offering up the dripping flame— Sacrificial.

And for a moment, This little girl bent hell and earth at her will. And though the heat devoured the air from her mouth, And fire licked her heels, She couldn’t tear her eyes from the table that was already ash And hungry for more.

It was a pleasure to burn.

Liliana Stinson ‘23“Those bell peppers’re lookin’ good.”

Sal looks up from their careful plant evaluation and is met with a pair of worn, dirty boots right in front of them. They look up, past long legs in faded blue jeans and a sparse tool belt, craning their neck to look Mo in the face. She’s squinting against the bright sun, peering down at Sal with the same critical look that she always wears around them. They’ve gotten used to it, by now.

“Thank you,” Sal tells her. They return to their work, looking this way and that to make sure that each plant has enough water and sunlight to stay relatively healthy and finish growing properly. They’ve given up on forming any kind of friendly relationship with Mo, and at this point, making sure there’s enough food to go around is the most important thing. Bell peppers aren’t the most nutritious food out there, but it’s one of the only things Warren will eat, and Sal wants to make sure he’s keeping his weight up before winter comes.

“Whaddaya feed ‘em?” Mo asks. She still hasn’t left, and Sal vaguely wonders why. They also wonder why she’s asking. She’s got the best garden of them all, all year round. Patterson says it’s because she buries all the bodies in her yard. Sal chooses to keep themself out of that circle of speculation entirely.

“Just water, sunlight. Some compost, maybe, if they’re lookin’ a little peaky.” Somehow, talking to Mo always brings Sal’s Southern accent back to life, try as they might to bury it completely. It reminds them too much of how things used to be.

“Manure’s better for that, y’know,” Mo tells them matter-of-factly. “Helps ‘em grow stronger’n faster ‘cause of all those proteins and whatnot. Fish works well, too.” Sal just hums in response, wishing Mo would go off back to her shack and mind her business, but they can’t say that or else they’ll come back out tomorrow and all their vegetables will be gone.

Mo is still standing there. “How’s Warren?” She has to raise her voice a little to be heard over the white noise of the ocean to their left, and her voice is grating against Sal’s eardrums. Abruptly, they stand up. They’re going back inside empty-handed, but the bell peppers should be ready tomorrow, maybe the next day. They’ll wait to check everything else later; if they have to stay out here with Mo for one more minute they’ll lose it.

“He’s alright,” Sal tells her, stripping off their gloves. Mo squints critically at them, one hand on her hip and the other shielding her face from the sun. For a striking moment, she’s the spitting image of Sal’s mother. They turn around and throw up a hand in a vague imitation of a wave.

“I gotta run, finish up some chores. See ya, Mo.” Sal is walking with too much purpose to hear it if Mo even replies. They don’t care.

Warren isn’t really Sal’s kid. He was the neighbor’s, back when the Michaels were still alive. Out of everyone left in the circle, it only seemed right that Sal would take him. They were his babysitter, after all.

Warren also isn’t really a kid. If Patterson remembers correctly, he’s actually thirteen. Young, but not a kid. Before the world went to shit and there were more of them around, Patterson used to kinda judge Warren. He’d never seen a teenager play with dirt and rocks and sticks in the front yard before, and he used to laugh when his friends made fun of him.

All of those friends are dead now, and Warren isn’t so bad. Sometimes it’s nice, actually, to sit at the end of his driveway between work and just watch the guy play. He’s quiet and innocent in a way Patterson hasn’t seen in a long, long time. Warren is the youngest person he knows, and he may not be an actual kid, but he’s close enough. Patterson is just grateful for the occasional reprieve from all the gloom and doom. Who knew the end of the world could be so exhausting?

Wendigo Meaghan Kress ‘24

Wendigo Meaghan Kress ‘24

Sal makes sure Warren is settled at the table before they start doing laundry. He won’t eat if it’s dark outside, and as winter approaches, the hours of daylight are getting shorter and shorter, so he eats dinner at 4:30. Sal listens to him crunching on dry cereal as they wrestle with the drying rack. They’ve told Liz, at least a thousand times, not to fold the damn thing because it takes forever to open back up again. The metal frame creaks and pops as they wrangle it.

Sal wonders, dimly, what the beach is like. None of them have been down there for a while, content to stay up in their tiny hilltop neighborhood, safe and sound from the waterlogged threats below. The fence does a pretty good job of keeping the nasties out, as Liz calls them, but sooner or later someone will have to take one for the team and venture down to take care of the ones slowly but surely building up along the fence line. A couple don’t do much, but it’s a problem when they just keep piling up, and the last thing they need is for the fence to break down.

Mo did it last time. Probablyfortheflesh , a sick corner of Sal’s mind whispers. Forher garden . With a screech, the drying rack abruptly pops open, and Sal puts it down in front of the window, directly in the patch of sunlight pouring through. They hang their clothes up just like they always do—socks and underwear on the bottom, medium-sized garments in the middle, and the thicker, heavier stuff on the very top, right in the sun’s line of warmth. They used to do it the opposite way around, but Liz always does hers like this.

“It’s ‘cause the socks and stuff don’t take as long to dry, ‘cause they’re smaller,” she told them once. “And the bigger stuff needs more light and warmth, so it’ll do better on top.”

Sal and Liz were never really friends... before. They still aren’t, not really, but Sal thinks that Liz enjoys their company. The two of them are about the same age, and they have more in common with each other than they do with anyone else. Between a literal apocalypse and the handful of people still left in their neighborhood, Sal is all Liz has. Sal likes to think that they don’t need to rely on anyone. If they sometimes find themself craving Liz’s off-key singing while they work in the garden, or the quiet clicking of her knitting needles as she knits and tells stories—well. That’s for Sal to know.

“How’s your supper, kiddo?” They call absently, not really expecting for Warren to respond. They’ve only ever heard his speaking voice a handful of times, and other times he just yells. His doctors always thought he would never be able to properly communicate, but his sign language is pretty good, and he’s always known to point at things when asked what he wants.

Sal hangs a shirt and pauses, looking at it again. It’s navy, faded from wear and big enough to be a dress on Warren, maybe even them, too. The cracked and peeling logo on the front says Erwin&Co.

A shudder wracks Sal’s body, shivering down their spine and arms. They shove the shirt back into the basket, heart pounding. They always forget that they hide it here, hidden in plain sight with all their other clothes. They need to find someplace better, they think.

Sal grabs a pair of Warren’s trousers and hangs them up. Maybe they’ll stick it in their closet.

Fish Leineweber ‘23Cold Days

Sophie Croker Poole ‘23

The smoke blows north across the prairie, nodding at the presence of those that make it their home.

A wolf’s aching cry suddenly cuts through it and a blurred orange, yellow light is now revealed.

I admire this from the carriage’s fragile glass windows which remain strong as if supported by the power of God Himself. Facing away, my husband slowly braids Amelie’s hair with a scorched brush. He had left the stove on and she had left her doll behind. I gather myself and turn my back to the smoke, the window, and our life and watch as the flickering ceases and the night comes. We must wait.

We wait on those lime green seats until what we have lost becomes just as numerous as the orange yellow flames that have transformed the doll into ashes and joined the heat of the stove in song. I cannot help but notice each silent tear down Amelie’s red cheek as we sit in stillness.

Ellery Blurton ‘24

Hopeful wings are an icy curtain over an expanse we continue sky cascading through a blanket of winter light soaked, we sink down

They point, each drop a river Down my dark, heavy feathers Lapping against powerful, desperate breaths icey blue sky peeks through gray watch as we rise in open

air to iris blue as the horizon curves higher, higher turn, my friends, Away from where we have come.

I fall into you like the tides from back home. Your softest rip current, Your eyes are sea foam, But the water is warm here, so each night I’ll pray: I can hold you by morning as the shore drops away.

Ephemeral beauty if worst comes to worst, Cruel time’s crucifixion, Deep cardinal hearse.

Morning birds still sing sweetly so each night I’ll pray: Pull me in just once more, in death’s harbor we’ll lay.

We’ll lie under stars with my head on your arm, Dull knife of white lies, Denial’s alarm.

But the night still drifts in so I’ll pray and I’ll pray, And I’ll beg every sunset that I don’t see the day,

When you’re swept out from under me, Colossus of Rhodes. My lover, my Nazareth, Our statue erodes.

Catherine Nichols ‘24 Embrace Sophia Hurst ‘25

Embrace Sophia Hurst ‘25

This was not a beautiful island. It jutted out of the surf at odd angles and its shape resembled a loaf of bread. For a very long time, it was considered an eyesore to any who saw its familiar craggy shape against the horizon. It was said to have ruined many a beautiful sunset. The sailors of old liked to joke that God really phoned it in while creating this patch of his kingdom. His heart just wasn’t in it or maybe he was drunk on whatever intoxicant the immortal and indefinable turn to in their times of grief. And anyone who created an island like that would have to grieve.

But a few centuries ago Goblin Island--as it came to be know--was adopted by a woman whose eccentricity was matched only by her wealth. She fell in love with the rocky and thoroughly wild island and built a summer home on it. The island soon became a pet for the wealthy and anyone who was anyone just had to have a home on Goblin Island. They tore out thorny beach scrubs and seagrass gave way to manicured lawns. They filled their homes with framed fish and family portraits and threw raucous parties that lasted until the early morning light broke over the shore. Dusty pinks and purples hazy in the sky as people drunkenly staggered home in their evening gowns and pearls, their shawls catching in the cypress trees.

They built a lighthouse on the island for no practical reason, they just liked how it looked tottering on a rocky cliff, like something out of another time. They built docks for their yachts and imported exotic species to roam the island. Their champagne flowed down docks and into the Atlantic, thousands of dollars dripping down the oak panels. But in time this golden and heady age began to fade, that kind of recklessness and excess went out of fashion and slowly the island retreated back into its corner of the world. The houses fell into ruin, their shingled roofs crumbling under a few relentless nor’easters.

The island decayed and rusted and gradually fell into the sea. These days little remains of Goblin, just a stretch of beach and the occasional peacock. The island sits and waits still and silent against the sky. There are still a few cypress trees though. A little bit of fabric clings stubbornly to a branch, a piece of once white silk browned by sun and time gets stirred by the breeze, the last vestige of a glorious and golden time long past.

Ginny Hopkins ‘23Under low light, a wooden table sits. Its size isn’t impressive, nor its condition; it’s clearly worn and in desperate need of polish. Scratches and paint cover its surface when it’s not piled high with half-empty glasses, bills, and groceries still in plastic bags. It’s always called the same cramped spot in between the kitchen and the back door home, flanked by a sea of mismatched chairs, all in various states of disrepair. Boxes fit in the spaces between the chairs, bulky puzzle pieces forced in places they don’t quite belong. Accessing the table is near impossible with all the moving-things-elsewhere required.

Whenever Tom casts his eyes over the table, they fill with regret, wishing he’d just pull it together and clean up his table. It’s served him for twenty-two years for god’s sake. After all that time, he should at least give the wood a chance to see the bit of sunlight that comes through the kitchen window. After all they’ve been through together, he shouldn’t just bury it in clutter.

But the habit has become so achingly familiar that he can’t quite bring himself to manage without it. The groceries make for much better company than an empty table that used to seat more than just one lonely old man. When his hands run over the table, all he feels are the stains and scratches and rough patches and all the years he was more than just himself. All the laughter and birthday parties and late-night fights seem to have worn into the wood grain. It’s hard not to hide the memories beneath the clutter, even though he knows he ought to just tidy it all up.

Every night he makes himself dinner. It takes him much longer now that his hands got the shakes, but he always gets some kind of food on a plate and that’s all that matters. Every night he finds his favorite wooden chair—the one whose legs are the least broken and easiest to pry from the boxes—and carefully creates a place on the table in between all the debris for his plate to rest. And every night he dines surrounded by cereal boxes. His oldest, Lindsey, always loved Cheerios and about a year ago he put a box by her favorite spot just in case. Just in case she stopped by or brought her little ones or needed his help. But he couldn’t just leave the other two out like that, so now in Sarah and Kate’s spots sit a box or two of Frosted Flakes and Raisin Bran. Just in case. And every night, no matter what his day has held, he’ll sit down at the table that saw three children grow up and their father become old with only cereal boxes for company.

Tonight, he sits at the table longer than usual as the warm light from the window fades. And when the room has become dark and he can’t tell the cereal boxes from the rest of the groceries, he slowly pushes his chair back and stands. And perhaps someday he’ll realize that he’s probably better off getting a table whose legs don’t creak and whose chairs aren’t becoming a pile of sticks, but tonight will not be that night and this week will not be that week. Tonight as he stands and carries his dishes to the sink he takes a plastic bag full of cans off the table. And he kneels as far as his knees let him, and he takes the cans and finally places them, hands shaking a bit less than normal, into the cupboard.

Liliana Stinson ‘23

Ginny Hopkins ‘23

Ginny Hopkins ‘23

I throw stars upon the heavy chest of the universe. You watch as the cliffs rise over my sweet light trail far, far away

Do you hear her fingers play those mandolin strings of time?

If you place your ear against the surface of the sky

You may hear the ring of an opera or notes to her forgotten song.

Yet, her melody is a distant wave against galaxies a quiet sigh, as it reaches the rest of us For it cannot last.

Ellery Blurton ‘24To the young girls

Do not be afraid to be human

For to be human

Is to be alive

To Live in your body

Not as a sculptor

Or critic

But as a lover

Perceiving your beauty in kind eyes

Do not fear or rush age

But embrace every scuffed knee

gapped smile

And mark

For your body is a mural of the life you have lived and you are not made of plastic

But flesh

Bone And fire

Live fire that billows through the eras of life

Feeling

Seeing Burning

Oh young one

Do not be afraid to burn

V Edwards ‘23 Hand Outstreched

Liliana Stinson ‘23

Hand Outstreched

Liliana Stinson ‘23

Big Bird

Catherine Nichols ‘24

Big Bird

Catherine Nichols ‘24

Haikus

A

You are so dada

Indefinitely alone feathers on your head

B

Nobody understands Snacks in the vending machine Cats jump for skittles

C

Gleam from the pasture

Cows jump onto ice cream Was it chocolate?

D Twix sprout from the ground

Lemon drops fall from the tree tops Blinked and it was over

E shadows all around the brightness creeping around left on the concrete

F lemurs in my room

why do pets make such a mess but these are not pets

Estelle Mason ‘23

Ginny Hopkins ‘23

Ginny Hopkins ‘23

It started with the summer sun, and everything that was already there. And then came the twigs, gathered around the base of a maple tree by clumsy child fingers. Not soon after, they began to slot the sticks between the mulch until they could stand on their own. They built walls and roofs made of foraged bark and formed floors of verdant moss they’d pulled from the dirt with reckless abandon. The spot tucked behind the garage was reduced to a muddy wasteland since they tore up the ground, but in the building of a world eons away, casualties are natural. At some point, the child god invited two others to join her, and from there, the houses beneath the all-knowing maple multiplied: an unstoppable wave of primitive architecture designed by childlike wonder. At some point—after a post office was fashioned out of old, broken bricks, a tree hollow was turned into a school, and a playground sprawled in between the miniature neighborhood below—they named the first fairy. Some exceedingly creative title was given to her, along with nature’s grandest mansion below the maple. They sewed her dresses of red leaves with grass they had threaded through a needle and gathered individual lilac flowers for her to place in her hair, for she was to be the prettiest fairy in creation. She was quickly accompanied by a host of winged kin: a mother, a father, and a sister, all lived in adjacent stick homes, and across the town, a fairy who the children could only imagine as a lover took up residence. And in their young imaginations, the two would one day meet on the platform they’d built in the highest branches of the tree. And they would dance in the sky as the leaves sang for them under the light of galaxies. Who could resist love’s calling after that.

One child of the three took it upon herself to put the post office into business, as she began to craft notes in a tiny, scrawling handwriting, detailing the lives of the new fairy couple and turning them from imagined to truth. Each sunrise, she delicately placed them inside of the post office bricks, for the other young gods to stumble upon when they went to oversee the world in the afternoons. Everytime the three would gather as one read aloud the tales of extravagant weddings and the ever-expanding families, and they couldn’t help but giggle, knowing that their world was now far beyond themselves.

Under the light of each moon that summer, you would see a 10 year old girl in her window, writing miniature notes in her best glitter pens; a faint smile never left her face. And under the maple tree, whose leaves were growing redder by the day, you would see a sprawling city made from fallen branches and dug-up moss. And perhaps, among the fireflies and the stars, you’d spot a fairy or two, waltzing as the world around them slept.

Liliana Stinson ‘23