Introductory Note

As these words and all the rest are being printed, some of us here at Chasing Cow Productions will be stomping up and down the fells of Scotland’s Southern Uplands, on a kind of artistic-residency-walking-holiday. As you are reading them, we will have just recently returned to Dorset. It’ll be good to be back, as it will be to have gone away.

While this issue is at least formally unthemed, the cover of this issue gives expression to the varying spirits of the selection this time round. Multitudes have developed in-between all this paper. Do they give rise to new interpretations or are they an Escher-ising of independent receptions? The cover began its life as a river, before a moment of it was fixed by a camera and ‘cropped to the point of abstraction’, I am told. Just as ripples in a pond expand out and allow artists the use of all sorts of supposedly profound metaphorical constructions, so do they make murky and opaque the bed beneath the flow – but where would the fun be in anything were it all straightforwardly intelligible and unchallenging?

The shifting of meaning is a central element of Grace’s latest essay, as she discusses Aphrodite-Venus and the island of Cyprus. A short story by Boris gives us a claustrophobic look out at infinity and insanity, featuring one of several instances of pathways in this issue; Jon Lever plots a route in a poem and Thomas Bachrach intervenes on trespass, one of the most salient political issues of our time. Fred takes under discussion an oft-utilised scene in film and questions its assumptions about the production of the individual, and Bryony tackles a similar form of complacency in her poem. Moving swiftly onward, we next have two differing guides; one to help us understand that august bird from our resident ornithologist Anna, and from Jack, a guide to summer films we can watch whilst sheltering from the sun. Stefan, in his inimitable satirical style, has created a review of a fake book. Or a fake review of a book? Whichever one you like really. For my part, I offer a dramatic scene.

While we may be suffering a drought in this country – something surely to get worse as the climate crisis continues to be accelerated by our blessed leaders in Westminster – we fortunately do not exist under a drought of entertaining, thoughtful contributions by those that allow us to publish them. We are immensely grateful for them all, as we are for you reading.

Tom BeedTo support future issues of Matter Out of Place, and other Chasing Cow projects, please consider donating the price of a cup of coffee & go to chasingcow.co.uk/support to donate via PayPal

Editors: Fred Warren, Grace Crabtree and Tom Beed

Illustrations and Artwork: Grace Crabtree and Bryony Moores O’Sullivan Design: Fred Warren and Grace Crabtree

MYTHOLOGY

Shape-shifting 4-5

Grace Crabtree

LAND

Keep Out 6-7

Thomas Bachrach

POEM Hold 8

Bryony Moores O'Sullivan

SHORT STORY

On Off Manoeuvres 9

Boris Hallvig

ORNITHOLOGY

Life is Short and Time is Swift 10-11

Anna-Lille Dupont-Crabtree

SATIRE

Review: Western Journey 12-13

Stefan Matthews

POEM

Capel-y-ffin 13

Jon Lever

DRAMATIC SCENE

Dimmer 14-15

Tom Beed

CULTURE

Peril on the Production Line 16-17

Fred Warren

CULTURE

Re-View: Summer Films 18

Jack Wightman

BACK PAGES

Word from the Herd 19

To view the current issue of Matter Out of Place online, plus online-only digital releases in between the quarterly issues, please visit chasingcow.co.uk/moop and follow us on Instagram @chasingcow

If you would like a PDF of the zine please email chasing.cow.productions@gmail.com

ABOUT THE NAME

‘Matter out of place’ is one of the ways that anthropologist Mary Douglas defines her symbolic idea of ‘dirt’. As she says, “dirt is essentially disorder. There is no such thing as absolute dirt.”

Whether it’s the condemnation of an adulterer or a pair of shoes on the kitchen table, ideas around ‘dirt’ and what is dirty are windows into how societies are ordered: what they value, what they find threatening, and what they wish to exclude.

As a name we think this helps convey Chasing Cow’s own non-adherence to established categories both in content – we like to let members pursue their own interests – and form – we view modes of artistic creation, whether that’s filmmaking, poetry or academic writing, as linked and encourage slippage between them. Finally, we think the name implies a level of critical thinking; if being clean means blindly accepting the values, behaviours, and hierarchies that shore up the current political order, then we have no choice but to be dirty.

Shape-shifting

by Grace CrabtreeStretching out beyond a valley of rock and cypress trees, beneath a deep blue sky, is an expanse of shimmering sea. Around my feet are scattered stones, increasing in size to immense blocks of crumbling limestone. These are remnants of a temenos (a sacred space dedicated to a deity) and a pillared hall, fragments of what was once an immense shrine complex within the ancient city of Palaepaphos, in modern-day Kouklia, on the west coast of Cyprus. Knowing the vast scale of this ancient site, I do a double take at some of these stones underfoot as I wander the hilltop, as if at any moment I could be crunching over fragments of sacred matter.

For millennia, this site was an important sanctuary to the goddess Aphrodite, a place of worship and pilgrimage for inhabitants of Cyprus, and those in the island’s easterly neighbours of Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and the Levant. Long before this mythical deity took shape, however, ancient Cypriots worshipped another: a figure known today simply as the Great Goddess of Cyprus, or Kypris. The megalithic sanctuary at Palaepaphos (‘Old Paphos’) can be traced back to c.1200 BC, in the Late Bronze Age. The cult of Aphrodite which grew on the island in the following centuries inherited some of the Great Goddess’s characteristics, as well as absorbing stories and symbols from across the water in the Near East, from the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna (later Ishtar), who in turn is closely linked to the warrior goddess Astarte, worshipped by the Canaanites and Phonecians. Since antiquity, Cyprus has been a melting pot of cultures, the island looking north to Turkey, east to Syria and Lebanon, south to Israel and North Africa, and out further west to the Greek islands. Standing at the ruins at Kouklia gives a tangible starting point for exploring a goddess whose origins and history are as fluid as the sea from which she was allegedly born.

Tumultuous beginnings

Aphrodite has a number of origin myths, which tangle across time and geographies, but in the Theogony of c. 730–700 BC, the ancient Greek poet Hesiod’s genealogy of the gods, she has a memorably bloody beginning. According to Hesiod, Aphrodite is the child of the earth goddess Gaia, and her husband (and also son), Uranus. The pair sired many children; Uranus, however, takes a dislike to some of their progeny and hides them painfully within Gaia’s body. Gaia implores her other children to help her, and it is Chronos who obliges; using a flint sickle made by Gaia, Chronos castrates, and overthrows, his father:

And so soon as he had cut off the members with flint and cast them from the land into the surging sea [...] a white foam spread around them from the immortal flesh, and in it there grew a maiden. First she drew near holy Cythera, and from there, afterwards, she came to sea-girt Cyprus, and came forth an awful and lovely goddess.

In this tale, she is both body and water, divine matter meeting in foaming crests from which she rises. This ties in with the debate around the etymology of Aphrodite’s name. Most enduringly, her name was linked by Hesiod to aphrós (ἀφρός), meaning ‘sea-foam’, but this is now considered a false ‘folk etymology’, perhaps as a back-formation from the myth of her birth. Today, scholars believe the name to be non-Greek in origin, perhaps Semitic, derived from her Eastern counterparts of Astarte and Inanna-Ishtar, but there is no definitive root. Yet ancient Greek word-lore has conjured up some compelling ideas: the second part of her name has been linked to -odítē, ‘wanderer’, and -dítē, ‘bright’. ‘Aphrodite the wanderer’ is a fitting epithet for this goddess who traversed the ancient world, harnessed by different cultures at different times.

Changing image

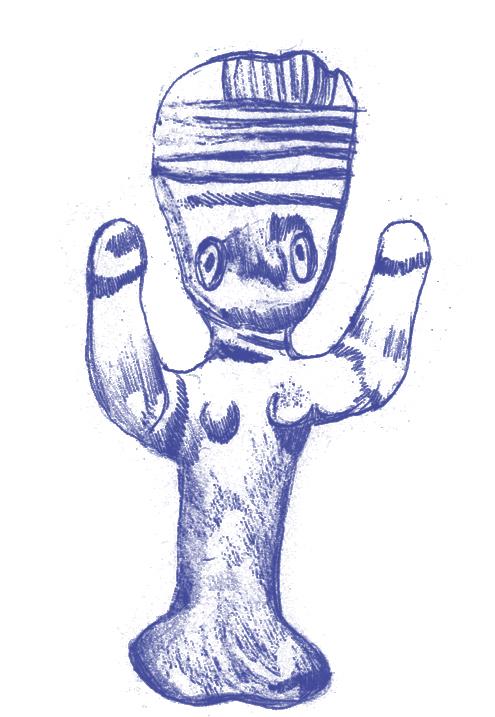

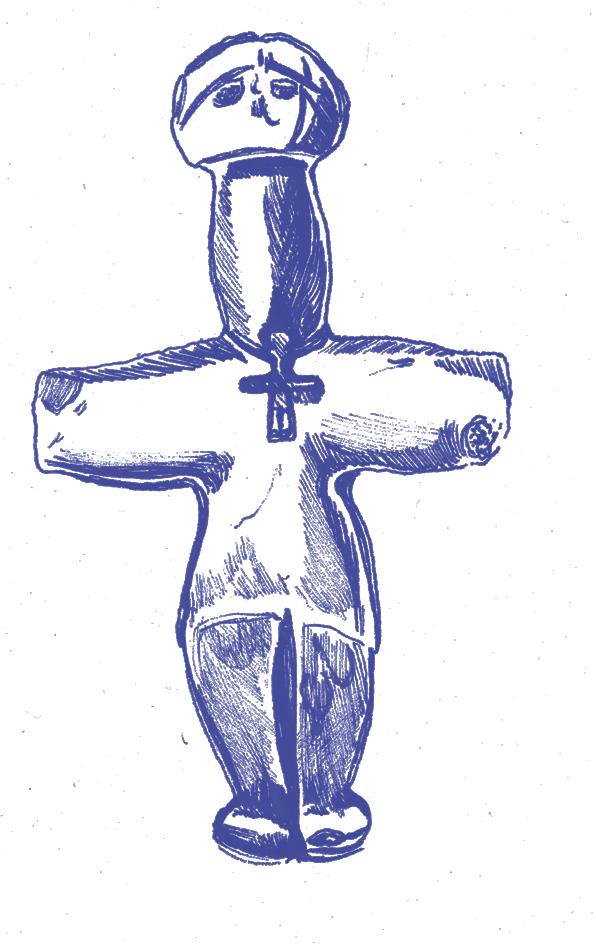

At each stage of her evolution, Aphrodite embodies some of the social, political, and belief values of the time. Her enduring epithet is the goddess of love, sexuality, and beauty, but as her Eastern predecessors show – as well as her bloody mythological origins and affairs with Adonis, Ares, and numerous others in The Odyssey and The Iliad – this is not an uncomplicated romantic love but one tinged with violence and vengeance – the extremes of passion. In Bettany Hughes’s ‘biography’ of the goddess, Venus and Aphrodite: History of a Goddess (2019), she traces some of these evolutions across time and place, starting with her possible beginnings in Chalcolithic stone female-male carvings and terracotta figurines of deities and worshippers, excavated from Cyprus and nearby lands.

“You can turn man into woman, / Woman into man”

In a hymn to Inanna by Enheduanna (c. 2300 BC)

Cyprus is strewn with archaeological finds, such as tiny, pale green picrolite figurines from around 2000-3000 BC, their bodies cruciform in shape, with pronounced vulvas and pregnant stomachs, as well as long phallus-like necks.

Often found in graves, the prevalence of these androgynous objects, and their often pierced heads, suggests they were worn as amulets – “taliswomen-men”, in Hughes’s term. Other finds further complicate our gendered interpretations of a feminine, fertile Great Goddess. In 1976, in the village of Lemba, near Paphos, archeologists discovered a statue known today as the 'Lady of Lemba'. Dating from around 3000 BC in the Chalcolithic period, this ‘lady’ bears resemblance to the picrolite figurines, with wide hips and a bulging belly and a long neck that is decidedly phallic. The size of this limestone carving – around 30cm – is extremely rare, however, so the 'Lady of Lemba' was likely an idol upon an altar, rather than a personal, domestic amulet. It is not certain what these intersex entanglements signify, but it is a theme carried through the myth of Aphrodite. A god-goddess named Aphroditos, or Hermaphroditos, was worshipped at shrine sites across the island, depicted in statues with breasts and female clothing as well as a beard, and sometimes revealing male genitalia. In Ovid’s Latin epic Metamorphoses of 8 CE, he describes the union of Aphrodite and Hermes resulting in a son who is eventually ‘merged’ with the Naiad nymph Salmacis, and the two are transformed into a male-female deity named Hermaphrodite.

Against the image

At the sanctuary of Aphrodite, archeologists unearthed another curious object: a large stone, smooth, dark, and roughly conical. This is a baetyl, a stone held in sacred regard. For worshippers, this cult idol would have been considered something like an embodiment of, or perhaps a material entrypoint to, the goddess, bringing the realm of the divinities a little closer and allowing worshippers to ground their prayers and rites in the earthly matter of rocks and stone. This imageless form of worship is thought to have travelled to Cyprus from the East. There is something vaguely, obliquely figurative about these rounded baetyl stones, as if hinting at the most basic idea of human form. Mostly, though, this is an intriguing object with aniconic power – without literal human representation, but imbued with immense potency.

Wandering Aphrodite

By the third century BC, depictions of Aphrodite had departed from the more abstracted, and sometimes androgynous, representations of a powerful female deity; instead, the goddess was more often a classical, life-like, idealised beauty and, notably, often denuded of her garments. This continued through to her transformation by the Romans into Venus (famously depicted in the Early Renaissance as Botticelli’s beauty in The Birth of Venus). One of the goddess’s most renowned sculptural depictions is known as the 'Knidian Aphrodite', thought to be the first fullsize, nude, devotional statue of a female goddess.

Her hand drifts coyly, half-concealing and half-drawing attention to her sex, while the other hand grips a drape of fabric that makes no effort to hide her form. Only existing today in copies, the 'Knidian Aphrodite' was created by the famed sculptor Praxiteles of Athens in the ancient Greek city of Knidos, in what is now south-western Turkey. Hughes notes that the 'Knidian Aphrodite’s' pose of barely-concealed nudity mirrors that of Masaccio’s fresco of c.1425, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, in which, even in her grief, Eve covers her sex as she and Adam leave the Garden forever. This isn’t an altogether unusual link between the Greek goddess and Christianity: despite the decline, even desecration, of the goddess as Christendom took hold, elements of Aphrodite seemingly endured in a new form, that of the Virgin Mary. Even today in Cyprus, her presence can be traced within the rituals of an Eastern Orthodox ceremony. At a church in Lemba on Good Friday, I saw women of the village decorating the wooden frame of an Epitaphios (translated as ‘upon the grave, or tomb’), which contains an image of Christ being prepared for burial. This tradition has been linked back to a midsummer festival, in evidence in Athens by the mid-fifth century BC, associated with the worship of Adonis. Women would lie an image of the fatally wounded Adonis on a wooden plank adorned with flowers, and allegedly “beat their breasts” in grief as Aphrodite is said to have done while mourning her deceased lover. The flowers may be in reference to the red anemones (‘windflowers’) said to spring up from the blood of Adonis’s wounds.

In her travels, Aphrodite-Venus is never far away from her tumultuous roots and associations with violence, vengeance, and extremity. In 58 BC, Cyprus fell from Ptolemaic rule to become a province of Rome, and as Hughes shows, the Greek Aphrodite’s transition to the Latin Venus goes hand in hand with the Roman “colonisation of the domain of Aphrodite”, the goddess strategically seized along with Greek lands and reconfigured to suit a society in fearsome flux.

Aphrodite’s shape-shifting, boundaryless biography means she is not quite ‘rooted’ in Cyprus, but is nonetheless indelibly connected to the island: the cult tradition of Kypris was not just carried through stories and ritual practice through the millennia but also embedded in stone, from shrine buildings and carved votive offerings to Petra tou Romiou, also known as ‘Aphrodite’s Rock’, another of her claimed birthplaces. In this way, the goddess remains inextricably elemental, and endlessly mutable.

KEEP OUT

NO RIGHT OF WAY ?? !

, Thomas Bachrach Reviews The Trespasser's CompanionThere was a big high wall there that tried to stop me; Sign was painted, it said private property; But on the back side it didn't say nothing; This land was made for you and me.

Woodie GuthrieA few weeks ago, in a total chance encounter, I met someone who, more than 75 years ago, had been a resident of the village in which I live. She had been visiting the former site of her house, which had since fallen into disrepair and vanished.

But aside from the fact that her former house no longer existed (something she luckily already knew), one thing that truly stood out to her was how you couldn't go anywhere, anymore. The huge sycamore tree that she and her friends once climbed was still there, but imprisoned behind a fence to somebody's land. The endless routes through the grand old deer park had been closed off until there was just one circular tarmac path. The great old oak tree, centuries old, that she had once played around is now no longer visible to the public, let alone approachable. Electric fences now line many fields in order to contain livestock, and clearly designated footpaths (constantly under threat) are the only legal routes.

There is one extra important detail; the place that we met was called The Common. Why is that? It is not common land and I am not entitled to walk there. The answer is not taught in schools, but it was one of the most significant processes in English history. Between the seventeenth and nineteenth century, thousands of enclosure acts took public land and, often illegally, sold it to the highest bidder. Common land, so carefully tended by communities who lived adjacent to it for generations, now fell into the hands of wealthy landowners, many of whom were absentee landlords with the sole incentive of extracting profit. It is this process that bears the greatest responsibility for the crisis of access we find ourselves in today.

And it is a dire, convoluted predicament indeed. A recent

report by Natural England showed how the ‘range’ of children had shrunk generation by generation; a child in 1919 Sheffield was able to walk six miles to go fishing, whilst his grandson was only allowed to walk 300 yards to the end of his street. This is just the tip of the iceberg. Making things even more miserable, many families do not have access to a garden, let alone a sizable one, and visiting nature requires getting in the car and driving miles in order to walk around strictly-defined paths. In total, 92% of the countryside is now off-limits to us. It is no surprise then, that although the countryside is often a point of pride for British people, studies have shown they also have some of the poorest connections to nature in Europe. When the acts of enclosure were passed, the poor masses migrated by necessity to the industrialising cities, where they could be better controlled and have their labour more efficiently exploited. Their descendants might consider themselves better off, but they now suffer from sedentary, urbanised lifestyles; notoriously poor for health, both mental and physical.

Nick Hayes’ new book The Trespasser’s Companion has a solution, and in the immortal words of Super Hans, the secret ingredient is crime. Not mindless crime, of course, but targeted direct action. Whether mass trespasses with hundreds or even thousands of people, or individual acts of defiance, all can be a part of the process of taking back what is rightfully ours.

Is trespass necessary?

As one might expect, the answer put forward by the book is yes. If, like most people, you have enjoyed a national park, you have walked on land that was taken back after years of protest and

“ Between the 17th and 19th century, thousands of enclosure acts took public land and, often illegally, sold it to the highest bidder. ”

mass trespass (in many cases, fights are still going on in existing national parks). Most famously, the 1932 Kinder Scout mass trespass, which saw numerous arrests and prison sentences, facilitated the creation of the UK’s first national park, the Peak District. Conservative lawmakers, often landowners themselves, cannot be trusted to “do the right thing”.

Trespass is not simply a means to gain access for walking routes. It is also necessary to help nature. Landowners often like to designate themselves “custodians of the land”, their barbed wire and signs warning others to KEEP OUT are supposedly righteous defences against a marauding public. Unfortunately, many landowners often like to lie and deceive. A great amount preside over heinous ecological destruction, using the cover of private land to hide their actions. One needs only to roam around a recently ploughed field to find detritus dumped by the more careless farmers; sheeting, old machine parts, bags and other bits of plastic. But the actions committed by landowners are often far worse, ranging from using ancient woodland as a dump, to raptor persecution, illegal grouse moor burning, and illegal use of chemicals around sensitive ecological sites. It is trespassers, probably more than anyone else, who bring these crimes to light, the more dedicated ones documenting them to create a basis for legal action.

Just how commonplace these incidents are does not bring much confidence in the common argument that the right to roam would wreak havoc upon the countryside. Landowners like to whine that people would trash the place, but they seem to be doing a fine job of that themselves. Nevertheless, such reservations are worth taking into account. The Companion places responsibility at the heart of its manifesto, offering actionable paths to educate people, change their habits, and provide better infrastructure to ensure the countryside is made pristine. It is worth noting as well that the Companion does not advocate allowing anyone to go anywhere at any time. It is totally legitimate to plant a large KEEP OUT sign in front of a shooting range or sensitive cropland. But when the footpath nearby has been illegally blocked off by signs declaring “private land”, such warnings become meaningless.

Other countries have done it. Scotland is the most notable country to have ensured the public’s right to roam and – shockingly – it has not resulted in the countryside being destroyed. Austria, Belarus, Czechia, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland all are notable European countries to have specifically passed right to roam laws. Will England, or perhaps the UK as a whole, be the next country to do so? It seems unlikely. But such hopelessness faced the trespassers at Kinder Scout almost a century ago. It is only by repeatedly and assuredly asserting our rights that we can begin to push back the wrongs that the acts of enclosure did. I hope that The Trespasser’s Companion becomes a valuable weapon in this fight.

For more information visit: www.trespasserscompanion.org

Thomas Bachrach has recently completed a Masters in History at the University of Exeter.

“

If, like most people, you have enjoyed a national park, you have walked on land that was taken back after years of protest and mass trespass ”

“ Scotland is the most notable country to have ensured the public’s right to roam and – shockingly – it has not resulted in the countryside being destroyed. ”Illustrations by Bryony Moores O'Sullivan

Hold

Bryony Moores O'SullivanHold it in, they say, Reel back, from the immensity, And ensure your pinks are smothered beneath the right shade of beige, Hold it in, so we hold until the numb sets in. Or worse it doesn’t, we try and pack it flat under food and drink and aftershave and stuff and cookie cutter love, Nothing nourishing in this superstore, But we are doing our best with it all, Know that each and every one of us is muddling through however we can, Plan or no plan, it unrolls and we learn and grow around the barricades and reach for the light, Some twisted and paled by circumstance and some wide and green and full of promise, Just as easily cut down before their time. So pull the golden thread from the air and follow it, The shopping can wait, Run to the water, no longer searching for Eden, But feeling the last of the summer day and knowing we need less and more than we think we do, Letting the charged Kaleidoscope unfurl unhindered, full of subtle opportunity.

Off On Manoeuvres

Boris HallvigThree of the company had huddled round the door kept ajar by an old sleeper and were playing cards on the lime-whitened floor. Lime lay all over. Not only the wagon but our boots and uniforms and hair and faces. It scratched at our throats. One player used the dusting on the wall to keep score with a licked forefinger; judging by the figures, it was a protracted game of chinchón

Whenever the railroad led us chuffing into a shaded valley, the solitary shard of sunlight would extinguish. Then some disembodied voice would invariably put in, “¿Is this a knight or a knave? ¡Can see less than Pepe Leches, now!”

As the hours wore on, I began marvelling through the gap in the door like a member of a strange subterranean society feasting his eyes on the surface world for the very first time. Little could be made out. Just a narrow smudge of ballast and railing and grass and sky. Nothing would have offered more relief than to ride with the doors gaping. Bask in air and light and scenery. ¡But we were so sardined our superiors were afraid we would tumble out! At least they had the benevolence to jam a sleeper in the door, granting us a means of urinating outside instead of all over one another.

For what seemed an eternity I held out. Eventually, the water from the canteen I had been knocking back since the march to the station swelled my bladder to bursting. ¡The urge was irrepressible! I pushed through the throng apologetically, trampled all over the playing cards, and warily poked my member through the gap.

¡Such bliss! Not just to drain my bladder but press my face to the gap and widen my field of vision. Everywhere I looked grasslands stretched, scattered with holly oaks and pinprick cattle. ¡What a sight for sore eyes!

When the train veered into a long arc, the profile of the locomotive came into view, then the wagons laden with more, gloomy, human cargo. Cinders fluttered. An impatient card player tugged at my trouser leg. But I released my urine ever so slowly, stealing every moment possible.

As the railroad straightened out, we crawled alongside a finca. It had a rickety house and tobacco in flower and white chickens and an old crone beating a rug to death.

We exchanged glances.

¡How serendipitous it was that the train should issue a sharp, shrill, drawn out whistle to muffle my mad, mad, howling laughter!

Should Boris Hallvig have to write a bio, it, like the man, will be short and—bitter.

Swifts are back in town! Catch them roaming high in the sky until the end of August. If you see them lower down, making high-pitched “screeching” noises, they are chasing each other and defending their territory from other birds.

Swifts are only temporary UK visitors as they spend 3/4 of the year between West Africa and East Africa, following the rains and the changes in insect populations.

Even though they know the continent like the back of their hand, they very rarely put a foot down in Africa. That’s approximately 10 months in the air. Their migrating journey back to Europe is over 10,000 km.

Swifts love to build nests in urban areas: they like tiny holes between gutters and roofs, never less than 5m high. Once they settle in a hole, they come back to it every year, even if that means getting rid of any new tenants!

To feed on the wing, swifts fly with their mouth open to catch as many insects as they can (over 500 different species). The insects are collected into the back of the swift’s throat, bound together with saliva in a ball called a “bolus”.

They are also the fastest bird in flight (only beaten by the peregrine falcon’s swooping dive), and can travel up to 70m/h. In a fraction of a second, they can identify stinging insects like wasps from hoverflies (which look almost identical).

To sleep, swifts flap their wings for 4 seconds then let go. The next 4 sec- onds are used to re-gain the altitude lost when asleep. It’s much warmer in the sky at a bit of an altitude. Around 5 a.m swifts drop from the sky and their day starts again.

Swifts are almost never seen perching on trees or electric lines because they have such tiny feet, even smaller than wrens for their size! Their scientific name, “apus apus” means “footless”: as they very rarely land, they have evolved to have very short legs, but strong toes that allow them to grip onto walls and cliffs, and sharp claws to fight over nest sites. In the 12th century, it was believed that swifts didn’t have any feet at all.

This is what inspired the myth of the “martlet” bird. It was depicted in English heraldry with tufts of feathers instead of feet, and designated birds that spend their life on the wing, an allegory for continuous efforts and an existence of resilience. The name “martlet” was influenced by the etymology of the “martin” bird, and inspired today’s name for swift in French, “martinet”.

Unfortunately, swift populations have drastically declined by more than 50%. This is mostly due to the ever-growing transformations of our urban landscapes: the building of modern housing that makes nest-building impossible, and the repairing of derelict homes by filling up the holes that once housed swift nests year after year. Climate change is also affecting migratory birds, as well as the decline in insects due to pollution.

Anna-Lille Dupont-Crabtree is youth engagement officer for the British Trust for Ornithology. She is interested in reconnecting with nature through the prism of art. Follow her Instagram @annanasrule

There are several accessible ways of helping swifts. Retaining existing swift holes or installing swift boxes is crucial to help them during nesting and breeding seasons. Planting wild flowers attracts insects that swifts then feed on. Reporting swifts in tracking apps such as BTO’s “Bird track” or the RPSB’s “Swift mapper” and surveys such as BTO’s “Breeding Bird Survey” will help understand the changes in bird populations, and identify the best ways to help them. Finally, spreading the word about the UK’s Red List of endangered birds.

Review of Western Journey by François Laurent-Decare: A daring journey back into Chinese history

by Stefan K. MatthewsThere’s something immensely encouraging, perhaps inevitable, about François Laurent-Decare’s latest project. A masterpiece of literature, Western Journey is this generation’s geminae-extraordinaire, a work I predict is destined to be unsurpassed for centuries. Immortal use of language, sublime intricacy in its wordplay, and astonishing thematic relevance; Western Journey is ambrosia prose translated for the masses.

I picked up the novel at one of the new Penguin Random House vending machines – futuristic gadgets placed across major spots in London that I’m sure you will have spotted in your travels. £18 and two hours later, the machine had produced the entire novel for me, a fantastic print-on-demand service that I shall be reviewing in the coming months.

Of course, when one first picks up Western Journey, one notices the novel is a direct, word-for-word translation of the 16th century Chinese novel Journey to the West, attributed to Wu Cheng’en. I have had several uneducated ignoramuses suggest Western Journey is simply a reprint of that Ming dynasty work, complete with Chinese-style bookbinding and East Asian marginalia. Of course, one with any insight into Laurent-Decare’s history of writing knows that is not the case – one need only look at his 1991 translation of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe to see that his identical rendition of the story was not mere replication, that it instead far surpassed the original. Doesn’t the character of Friday have far more poignancy when written by a modern author, rather than one from the 18th century? Is Crusoe’s relationship with nature, animal, and man not infinitely more nuanced in our modern age than in 1719? Defoe’s Crusoe was inexorable; Laurent-Decare’s was what? Inconceivable?

And, as he did back with Robinson Crusoe, Laurent-Decare has done something special with this new novel. His translation – work that has taken him forty-seven years and two marriages, if rumours are to be believed – is not in English, nor French. No German, no Dutch. No, Laurent-Decare has taken the most courageous stance possible and rewritten the entire work in the language it was first written in – 16th century Chinese. Now, one without knowledge of pinyin and the Chinese language may struggle with the text; indeed, having never learnt the language I struggled at times but that is not the point.

Western Journey does not need to be read, for simply looking at the characters you innately obtain a vast sense of its exploration of existence, snapshots of modern life filtered through his incredible knowledge of Chinese myth and expressed in a language unreadable to most in the Western world. To see the brushstrokes is enough to understand Laurent-Decare; that is if such a thing is possible. Such bravery!

Yet, the most daring thing about the novel is that it is entirely unfinished. In a stroke of literary genius, Laurent-Decare has ascended the boundaries of art, of literature, of what we believe a novel should be. In one fell swoop of heroism he has gone where none have dared tread – audacity beyond comparison – as he boldly leaves the work unfinished, untranslated. Indeed, in the footnotes (which incidentally run longer

than the novel and are in French), François speaks of the difficulties of translating a work he could not read, how it took him decades to learn how to imitate the brushstrokes of Chinese characters. In his darkest hours, he even considered (if only for a brief moment) translating the original Journey to the West into English or even (God forbid!) French, his birth language. But, thankfully for all of us mere mortals, he conceded that the idea was cowardly, a clumsy exercise in mimicry that was below his genius. Instead, Laurent-Decare resigned himself to the unenviable, inevitable, and perhaps even martyrdom-esque task of writing Western Journey in that original Chinese language. In doing so, he has created a work that far surpasses the original, an expanded abridgement that extends itself far beyond Journey to the West (literally, thanks to the footnotes).

To illustrate the above points, please, compare the following two passages (I have had them translated back into English by a colleague, for ease of reading). First, a simple passage from the original text Journey to the West:

There is nothing for it but to work hard early and late. Now my mother is old and I dare not leave her.

Now, that very same passage from Laurent-Decare’s Western Journey:

There is nothing for it but to work hard early and late. Now my mother is old and I dare not leave her.

The difference is extraordinary. The first is quaint, to be sure, a cute insight into 16th-century China and its traditions of work and labour. But in his contemporary reimagining, Laurent-

Decare has elevated it to new heights – it’s as if one feels the weight of the entirety of human history on his shoulders as he muses on life, work, and death. The latter is more subtle, finer in every detail. We feel the crushing, almost impossibly difficult work faced by the character as Laurent-Decare carries us through exhausting workday after exhausting workday. We weep at the tragedy of the mother before Laurent-Decare transcends an individual’s ageing frailty to bring us face-to-face with the ageing frailty of all humankind, a stunning metaphor that is nowhere to be found in the original work. With Western Journey, Laurent-Decare has done the unthinkable in translating and improving upon that ancient text and, well… Re-read those excerpts above if you are still unsure of the genius.

N.B. It has come to my attention that the vending machine that printed my review edition of Western Journey copied and translated Laurent-Decare’s novel into binary code before the printing began. As one can imagine, the effect of this was close to

Capel-y-ffin

Jon LeverNo thirst to slake, nor itch to sin no alacritous soul to fill a skin nor bruited wavering strength within For the high route march to Capel-y-ffin

Peppery footsteps gathering in the sheep and the goats, the kith and kin, the lost, the found and the steeped in gin On the drunken road to Capel-y-ffin

Ten to make and the match to win but the top is as bleak as original sin and you wonder if it might take spin from the Nursery End at Capel-y-ffin

The word-blank page is bible thin, Is your parchment, chemotherical skin, Is the point from which the dead begin To bluff their way to Capel-y-ffin

Where they’re gilding a cage wherefore to pin Ambivalent balancing angels in Desire is down and the air is thin at the fork in the road to Capel-y-ffin

So bed down now where all things begin, In Yeats’s cymric bone shop twin Further up and further in, Beat the retreat to Capel-y-ffin

heart-breaking and has rendered the entire above review redundant; one cannot begin to see the true genius of Laurent-Decare’s work on a mass-printed parchment. How could a digital replication of decades of self-taught Chinese brushstrokes be anything but insulting? Indeed, when I purchased my copy of Western Journey, I believed the vending machine would be printing via more traditional methods, perhaps with some sort of mechanical calligraphy brush inside the machine. This shocking oversight from Penguin Random House is an affront to Laurent-Decare and his ground-breaking effort, diluting his great work of stroke-for-stroke translation into a lifeless mechanical duplicate. Is nothing sacred?

Stefan Matthews is a screenwriter and graduate from Bournemouth University. He is a dream-smith, an illusion-weaver, a forger of fantasia. Well, that’s what he claims.

Jon Lever is a billionaire philanthropist, Nobel laureate, and wildly implausible liar. He publishes at the-electric-dark-age-hymnal.com

A dramatisation of certain events

CHARACTERS

DWELLER: 38, dressed in blue jeans, a red flannel shirt and brown leather waistcoat. Speaks with a flat affect and unstable countenance.

THE RADIO: Contemporary household radio. Blue with signs of wear at each corner. Antenna slightly bent. Moves imperceptibly when speaking.

THE CRATE OF SCREWS AND HAMMERS: Red folding crate, filthy with dust and grime. Overspilling with tarnished hammers of all sizes and a heap of unsorted screws. Does not speak.

[Forty miles to the south a valley contains within itself a hallowed vale ringed by oak and hemlock saluted by pillars of sandstone in all directions. A cottage grips the slope of the western face and there, sitting, is a man faced opposite by a stout blue radio endlessly functioning. It jauntily elevates an arm towards the bay window in between and above the pair. THE CRATE OF SCREWS AND HAMMERS rests in the centre of the room and does not interrupt. A dialogue will be resumed but presently under the light of the moon the vale moans and shifts side to side. Beneath the wooden stairs carpeted with hessian the lantern centres the table at which DWELLER is located exactly. Regularly he raises his head from his lap where his hands are and grins with a knowing mirth that lets THE RADIO be aware of his intent. Suddenly he is adjusting the lamp to darken the walls that keep him.]

DWELLER: My friend, I am in the grip of the fecundic moon.

THE RADIO: I too, am in the grip of the lilac spoon.

DWELLER: There are no heights to reach anymore as the man before stated. Only one.

THE RADIO: Only one.

DWELLER: Yes, but notably distinct personae like to make pronouncements and they like to talk of swords.

THE RADIO: He forgot everything, about himself.

DWELLER: He did everything, about himself.

THE RADIO: Let us get ready. I’m getting ready.

[They both get ready]

DWELLER: [Rapping tabletop] Is there still something out there?

THE RADIO: This is fleeting. Why not record it?

DWELLER: You’ve become preoccupied by material distractions.

THE RADIO: Ah, [antenna extends fully to the window] but I move with the voice and come and go simultaneously.

[DWELLER gets up, pushes chair to the side, steps over THE CRATE OF SCREWS AND HAMMERS, walks up the stairs to the window, places left hand on the glass while his right fiddles with the blind cord]

DWELLER: Ah. I think we have both been transfixed by some thing. [lowers blind halfway]

THE RADIO: Is the peak still burning?

DWELLER: [moonlight illuminates his face] Yes, in the twilight it burns.

THE RADIO: We couldn’t stop staring, not even the rod withdrew our enthusiasm for the object of our inquiries.

DWELLER: First on one hand, then after that next on the other hand, we can see…[steps back suddenly from the window] That in actual fact we learned to speak in ways… [walks down the stairs and back to his seat, avoiding THE CRATE OF SCREWS AND HAMMERS by stepping over it] That had more feeling to them, wouldn’t you say? [Sits, crosses left leg over right]

THE RADIO: Yes yes good point yes.

DWELLER: Do you remember the name of the man on the peak?

THE RADIO: [retracts antenna fully to stowed position] I know only that he staggers about with a black-maned mare on the scree.

DWELLER: He saw something, down there, in the tavern, in the town, in the amphitheatre, in the town, it was his kin and someone whose face he could not see because it was not lit, in the corner, in the amphitheatre in the town.

THE RADIO: Notable existences are portrayed and transmitted. Several distinct cases replicate unbeknownst to the machinations of a contemplation which in itself is plotting a grip yet more total.

DWELLER: Truncated monuments.

THE RADIO: Trivial exuberance.

DWELLER: Would you make the life of one better for no reason?

THE RADIO: It would only be fair if an equal amount of people had their lives made worse for no reason.

DWELLER: I see.

THE RADIO: I,

DWELLER: Aye.

THE RADIO: Icy.

DWELLER: One year ago to this day, I know that you remember, the first decree reverberated across the land. The wires allowed the passing forth of all the words the leaders could muster in service of the plan, which continues to go ahead. Even now there are directives being carried out and completed, marked down as such and new directives sent off to other departments. Those who do not agree with the vision of the future as set out can add their voices to the opposition and speak in a tone much like that of the opposite of themselves. Time can only be measured by the procession of productive forces and the statistical, scientific results of the efforts taking place.

THE RADIO: I tire. [Falls off the mantelpiece with a crash] Will you next flee into details or generalisations?

DWELLER: They knew that something had to be done. [Steps over to the mantel, places THE RADIO back in its place] Do you remember how we both felt, how the whole of the country felt? We were so excited that something was going to happen. It had to start happening, you agree don’t you?

THE RADIO: Something had to start happening and it had to be that I am sure yes yes,

DWELLER: They had to put shutters there.

THE RADIO: They put them there and gave us vision.

DWELLER: Yes. There.

THE RADIO: There.

Peril on the Production Line

ByFredWarrenA moment of flux – a chase, a capture, a wrong turning – and we’re somewhere new: a spacious interior, grey walls, fluorescent lights. Molten metal is poured, automated arms solder, as raw material progresses, step by step, towards commodification. No time to dwell though, as we’re soon hurled into the meshes of this elaborate mechanism. Now every streamlined section becomes an existential threat as sparks fly, bolts are welded, and ovens are heated. Duck, dodge; another close shave. The conveyor belt rolls on, the panic building as that final black box looms – the point of no return. Then a flurry, a conflagration and all’s quiet. Pause.

Rolling out comes a neatly packaged product. But wait… Some movement? Surely not!? The individual has escaped the jaws of the machine! We let out a sigh of relief. Cut to next scene…

So goes a scene repeated across cinema: from the milk bottling plant scene in The Borrowers (1998) and the pie machine sequence in Chicken Run (2001) to the car factory scene in Spielberg’s slick sci-fi Minority Report (2002). A scene which I’m naming Peril on the Production Line (POTPL). To clarify, POTPLs are not about factory workers, nor are they that broader ‘chamber of horrors’ narrative where characters proceed through a Dantean series of levels either to escape (Squid Game) or reach some mythical centre (Heart of Darkness). No, what’s important about the POTPL is that it exists apart from the primary plot. It’s this seeming arbitrariness, this baroque superfluity, that makes these scenes ripe for (over?) analysis. So, hop on, mind the belt-sander and gravy gun, as we dismantle the POTPL and travel towards its inner workings.

scenes where spatial and temporal geography are too often lost in a blur of increasingly elaborate, yet increasingly bland, CGI, POTPLs strip back an action sequence to Aristotelian principles where escalating action is contained in one place and plays out in close to real time, allowing us to focus in on and care about the characters on screen.

And yet, these scenes seem to be communicating more than simple thrills; indeed, the factory scenes in the aforementioned films all seem to be dramatising the same theme: that of the plucky individual resisting systems of standardisation and rationalisation. Whether it’s a family of marginal peoples protecting their way of life from property development (The Borrowers); a police chief finding himself a victim of an infallible pre-crime detection mechanism (Minority Report); or the chickens fleeing the conversion of a family egg business into an automated pie factory (Chicken Run), all three find their central conflicts come to the fore on the factory floor as the characters are literally caught in a mechanism that’s trying to erase them.

The plight of the individual against totalitarising systems is of course a staple of cinema and literature of the twentieth century – from 1984 and The Trial to The Catcher in the Rye and The Graduate. It was given a concise summary by Albert Finney in the British 1957 film Saturday Night, Sunday Morning where the young bicycle factory worker broods to himself:

“Don’t let the bastards grind you down [...] I’d like to see anybody try to grind me down. That’d be the day”

Perhaps the most obvious reason for these scenes’ existence is simply their dramatic appeal. In contrast to Marvel-esque action

In 1982, this sentiment found its metaphor in the famous scene in Pink Floyd’s rock opera The Wall, where a marching procession of school children are shown being led through and ground out of a meat factory. POTPLs continue this visualisation, but heighten the drama as characters are depicted actively resisting and (eventually) succeeding over the pull of the factory and all it represents.

“ These scenes all seem to be dramatising the same theme: plucky individuals resisting standardisation ”

Such resistance is particularly apt in the case of Chicken Run made by the Bristol-based Aardman Animations whose films often champion the organic and the inefficient over malfunctioning and (sometimes) malevolent machines. Such thematic preoccupations can be seen mirrored in Aardman’s dogged embrace of the medium of stop-motion animation. As Michael Frierson explains in Clay Animation, 3D model-based animation was pushed aside in the early twentieth century by 2D cel animation which was better suited to efficient “assembly-line production methods”. The comparatively painstaking nature of stop-motion is exemplified by the first 24-minute Wallace and Gromit which took its creator Nick Park an incredible six years to complete. Aardman’s tales of idiosyncratic individuals surviving mechanised threats – from cyber-dogs to bronze age mining – can be seen as allegories of the studio’s own successful resistance against more ‘modern’, ‘rational’ modes of creation.

enthusiastically, as they try to navigate a market-driven world where their bodies, assets and credentials are permanently ranked and compared on social media. In such a climate, the market’s wants eventually becomes indistinguishable from one’s own: it’s important (if not mandatory) to try and be your ‘best self’, but obviously that best self includes having a high-powered job, going to the gym in your spare time and keeping up with fashions. It’s unthinkable that your best self might include being fat, unemployed, and wearing the same t-shirt every day.

And so, POTPLs can be read as a grand staging of that twentieth-century fear of the individual – whether that be a frenetic Tom Cruise or a particularly expressive piece of plasticine poultry – being homogenised by systems of social conformity. But does this cosmological conflict still ring true in the twenty-first century? On one level, the individual seems to have triumphed with culture and advertising permanently impelling us to ‘dance to our own tune’, ‘be our best selves’, become beautiful and empowered. Meanwhile, the decline of those overarching social institutions – the school, unions, the health service, even the neighbourhood – has opened up space for the individual to emerge as the most important social unit.

And yet, we’d do well to be sceptical about just how liberated this twenty-first century individual is, especially when the ripping away of social institutions and the atomisation of social life has left people more exposed and vulnerable to the pressures of the market. As the essayist Jia Tolentino explores in her dispatch from the frontline of late capitalism, Trick Mirror, the typical ‘successful’ woman in America today is now ultimately one who has learned to reproduce the lessons of the marketplace in every fibre of her being. As Tolentino writes:

“Old requirements, instead of being overthrown, are rebranded. Beauty work is labelled “self-care” to make it sound progressive […] instead of being counselled by mid-century magazines to spend time and money trying to be more radiant for our husbands, we can now counsel one another to do all the same things but for ourselves.”

In this world, individuals no longer need to be compelled by hostile external forces – embodied by the schoolmaster, the foreman, the priest – to conform to oppressive, patriarchal, structures. Instead, individuals now conform voluntarily, even

It ultimately seems that individuals today are more constrained, their bodies more disciplined, their time more accounted for, than the days when ‘the man’ was trying to control these things. Such nostalgic times at least had moments when, in leisure, the individual was released from the pressures of work and conformity. These moments of respite were also the times when alternative political futures could be imagined and people could come together to try and change the status quo. In contrast, there’s no such conceptual space when leisure time is time for ‘self-improvement’, socialising is reconceived as networking, and prospective partners are ranked on dating apps like stock options; when our entire lives move with unreflexive, mechanical precision in pursuit of attaining what Tolentino calls that “high-functioning, maximally attractive consumer existence” which we've internalised as our own ‘authentic’ dream.

So, it would seem that the POTPL scene perhaps doesn’t quite have the relevance today that it might have once had. Indeed, in revisiting these films, their worlds feel quaintly nostalgic; the Art-Deco-infused, 1950s stylings of The Borrowers; the family-farm business of Chicken Run; even the future world of Minority Report feels distinctly like an old film noir or Hitchcockian ‘man on the run’ film. They seem to play to the tensions of a different time, a time when the individual was at risk of being subsumed by a modernising world. Now, in a world where the individual is held above all else, the challenge is to find a new scene/myth/trope that shows that this idealised self might just be a trick mirror; a scene that shows that ‘dancing to your own tune’ might mean dancing straight back into the jaws of the factory after all.

Fred Warren is a writer and filmmaker. He spent university immersed in the field of post-humanities, though some think he should have spent more time thinking about post-uni life than post-human life.

“ Our entire lives move with mechanical precision in pursuit of attaining what Tolentino calls that “high-functioning, maximally attractive consumer existence” which we've internalised as our own ‘authentic’ dream. ”Illustration by Bryony Moores O'Sullivan

Four Summer Films Four Summer Films Four Summer Films

Jack Wightman

British summers are usually a washout. A concept without execution complete with freezing winds, undulating grey clouds, and gymnastic rain. 2022 has sent us Brits running 180 degrees the other way, scrambling for some of that elusive air-con. Whether 2022 decides to throw it down, or turn it up another notch, the movies have you covered. Hide from the rain or stick on the fan, and watch these reminders of the usually elusive season.

Summers are for vacations. Even for directors. Woody Allen has managed to chill around Europe for a couple of decades, and even stoic Eric Rohmer must have had a little fun with Pauline at the Beach. Most of these trips are about jettisoning emotional baggage to rekindle romance (As Good As It Gets) or for gawky outsiders to blossom thanks to a ragtag bunch of locals (see The Way, Way Back or The Simpsons’ Summer Of 4ft 2). While it’s comfortable to return to the same old destinations, there is one trip I insist you make.

Before there was Mr Bean, there was Monsieur Hulot. The creation of writer-director Jacques Tati tumbles head over heels with comedy geniuses Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd and Jackie Chan. Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953) is both title and plot, a two-hour vacation following the titular character’s time at a seaside resort with a weird and wonderful collection of caricatures. Ebert’s snapshot reminiscence catches the magic of the trip: "When I saw the film a second time, the wonderful thing was, it was like returning to the hotel… it was like I was recognizing the people from last year."

Alas, vacations have to end. Mom and Pop return to sticky offices, fish-hooking neckties a little looser for air, while teens cruise neon lit streets in American Graffiti, hike the hills in Stand by Me, or drink away facts and figures on the last day of school in Dazed and Confused. Summer Nights are hot houses for teens, sexual hormones bubbling until they burst into musical numbers about hooking up on the beach, under bleachers, or fixing up cars so fast the ‘chicks will cream’. The Graduate and Call Me By Your Name are familiar pillars of these formative summers, where the inexperienced learns a little more about the world and a lot more about heartbreak, but Alfonso Cuarón may have passed you by.

Cuarón returned to his roots with Y Tu Mamá También (2001), leaving his slick Hollywood training in the dust to hit the twolane blacktop with a semi-realist road-trip about Mexican politics, geography, history, spirituality and culture. Not that the behind the wheel notice.

All they care about is living it up while their girlfriends are away, and scoring with the seductive lady in the passenger seat. This creates a fascinating duality, the vitality of the young friends learning about sex and friendship while an omniscient and melancholic narrator accounts for the wider world, as if the journey is already a memory being reminisced. But by who?

If it seems unfair that teens get all the sex, drugs and rock and roll, horror balances out the equation. For every teen that gets lucky, two more get decidedly unlucky. Horror and summer go together like dark nights and those things that go BUMP in ’em. While a cardinal rule (even before the days of Val Lewton), that ‘the horror’ is best concealed in darkness, plenty of filmmakers turn on the lights. The Wicker Man, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and Midsommar revel in showing you, with clarity, just what exactly to be afraid of.

“ Cuarón, leaving his Hollywood training in the dust, hit the two-lane blacktop with a semi-realist road-trip about Mexican politics, spirituality and culture. ”

Haneke did something a little different. What came out of the darkness wasn’t something with fangs, scales, or tentacles. It was us. Funny Games (1997) (and the subsequent shot for shot American remake) follows two young men who torture a family at their summer home for no reason. Haneke continually twists his knife while pointing an accusing finger squarely through the fourthwall, asking why we watch these kinds of things. It’s a question that lingers long after lights out.

Need a breath of air after that? Tough. As the mercury rises, so does the tension. Can you imagine In The Heat Of The Night set in a shivering Alaskan town? Would 12 Angry Men have the same intensity if the jurors were huddled together like penguins? Heat makes us irritable, prone to volcanic explosions like Lee’s Do The Right Thing, or Schumacher’s Falling Down Stray Dog (1949) is a masterpiece of the too-damn-hot thriller subgenre from themaster-who-never-misses Akira Kurosawa. During a stifling Tokyo heatwave, a newly-promoted homicide detective (the impossibly cool Toshiro Mifune), has his colt pistol pickpocketed on a crowded trolly. Anticipating the buddy cop picture, Kurosawa's pulp storytelling and impeccable craft reveal a pitch perfect hotas-hell Japanese noir. Who needs a better reason to stay indoors? Now, let’s all head to the lobby and get ourselves some snacks. What do you fancy? Ice cream?! Are you crazy?! It’s too cold for that.

Jack Wightman occasionally leaves his home either for coffee, the cinema or to browse a bookshop. If you don’t happen to find him there, please send for help – he will most likely be trapped under his book collection.

Word from the Herd

What do Chasing Cow do all day?

Looking across a field of cattle you might view them as just another uninteresting feature in an unchanging landscape. But hang around, look at the cows for a while, and a more dynamic picture might start to emerge – grazing patterns, herd relationships, even some distinct personalities. With this in mind, we thought it was time to give readers a quick update on what we at Chasing Cow have been working on recently and, in doing so, hopefully transform ourselves from something unfamiliar and uninteresting into something infinitely fascinating (well, that’s the idea, anyway).

First to films: following a successful premiere in April, our two recent shorts, The Wind Blows (inspired by a Katherine Mansfield story) and The Modernists Apply for Arts Funding (inspired by lived experience), are now both currently sitting in film festival purgatory. On the advice of someone more informed, we have resisted the temptation to enter the ubiquitous ‘laurels for cash’ film festivals – ‘Fundance Super Special Monthly Global Film Awards’ – and instead opted for some of the more established festivals. We await answers, but as an alternative, it has been mooted that Chasing Cow could set up its own film festival, not only guaranteeing us a yearly supply of laurels and awards (The Golden Hoof?), but also allowing us to experience the giddy thrill of rejecting others! Either way, both of our short films should become available online over the next six months, whether triumphantly be-laurelled or not (if not, watch out for The Modernists Apply to Film Festivals appearing in the near future).

From new films to old films, May 2022 saw us revive our 2020 dark folk comedy, Brink by Brink, as we gave a screening and talk to the Loders Women’s Institute. Thank you to everyone at the WI for inviting us along. The film itself seemed to go down well, though it remains to be seen if ‘effigy construction’ and ‘bull’s heart enchantment’ will be added to the WI’s online list of ’Crafts to keep busy’. Speaking of crafts, big shout out to Bridport Community Shed for kindly (and expertly) fixing an important piece of filming equipment last month.

July saw us take MOOP on a virtual outing to the Glasgow Zine Fair’s online tables, and also begin recording readings of poetry in the landscape, as an audio-visual experiment in active listening, fuelled by considerations of how words and places lend each other meaning.

More recently, we’ve been commissioned to make a short film about the history of hemp in West Dorset and some exciting hemp growing trials happening in the area – look out for more news on this in the coming months. Our biggest non-fiction project, though, is an avant-garde documentary exploring rewilding from a social and aesthetic perspective. It’s this that has moti-

Enjoyed this issue?

Perplexed by it?

Threw it across the room in a fit of rage?

Whatever your response we'd love to hear!

We'll print any letters in our next issue.

vated an upcoming trip that some of us are taking to Scotland’s Southern Uplands, to visit some of the landscape-scale rewilding going on in the area.

It’s been reported by Isabella Tree that cows let loose in the scrubby complexity of a rewilded landscape adopt all kinds of novel behaviours unseen in enclosed fields – rubbing against tree trunks, foraging at pond margins and even “smearing sap onto their faces as insect repellent”. It’s hoped that we at Chasing Cow, freed from the domestications of Dorset, and left to roam the (re)wilds of Scotland, might, in turn, discover new ways of approaching our artwork, though it is possible our discoveries might also be confined to the art of coping with biting insects.

If you're interested in contributing to MOOP send us

a message for more info

Get in touch via email or social media:

Email: chasing.cow.productions@gmail.com

Instagram: @chasingcow

Website: chasingcow.co.uk

Surrender

Go to: chasingcow.co.uk

Read articles from previous MOOPs as well as online-only pieces on our website chasingcow.co.uk/moop

To support future issues of Matter Out of Place, and other Chasing Cow projects, please consider donating the price of a cup of coffee & go to chasingcow.co.uk/support to donate via PayPal, or scan the QR code below.