Find works from 24 different creatives from around the world ranging from art, fiction, poetry, nonfiction, and plays

Art | Fiction | Poetry| Plays| Screenplays | Films | Interviews

5| Winter

Issue

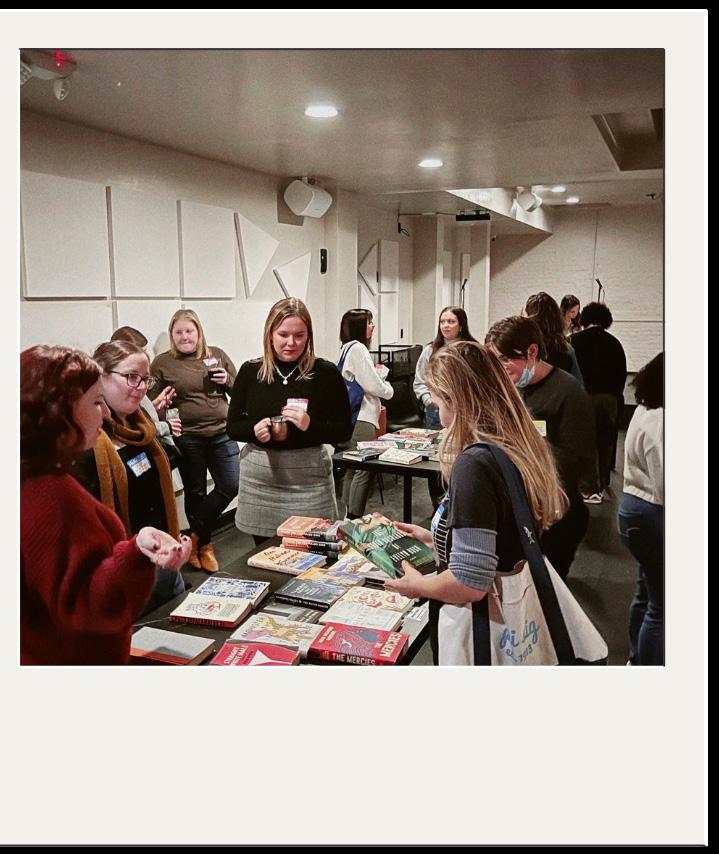

A Conversation with Zoë Mahler about the process and creation of NYC Book Hoes

Interview

© 2023 by Chaotic Merge Magazine. All Rights Reserved. All rights to all original artwork, photography, and written works belongs to the respective owners as stated in the attributions. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and publisher.

TABLE OF CONTENTS FICTION POETRY 65 86 108 19 21 23 ON EGGSHELLS by Audrey Carroll casualties by Alec Evan March SOILED by Reece Herberg twice over by Sage Kubis characteristics of our charism by Sage Kubis no Experation Date by Harris PlesKovitch NONFICTION 39 79 HOW TO BE CATFISHED OVER AIM AT AGE 14 by Erica Hoffmeiseter BACKSEAT LOVERS by Sam Carberry 117 95 16 61 62 94 THE DUST THAT REMAINS by Charmaine Arjoonlal KEEPING SECRETS by

Rubin LILITH FAIR, 1996 by Abby

WHEN HOUSTON BECOMES VENICE

DEBRIS

IN GEORGETOWN GUYANA

3 47 ASTROTURF

I WON’T BE THAT PERSON

PLAYWRITING

Rich

Hosterman

by Stephanie Holden

by Carolyn Martin

by Smitha Sehgal

by Kolin Lawler

by Sarah Elizabeth Grace

by Klara Asklund

by Klara Asklund

by James Diaz

by Kelli Lage

by Kelli Lage

COVERSATION WITH ZOË MAHLER Creator of NYC Book Hoes

by Hailey Thielen

Klara Asklund

by Hailey Thielen

Klara Asklund

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIALS

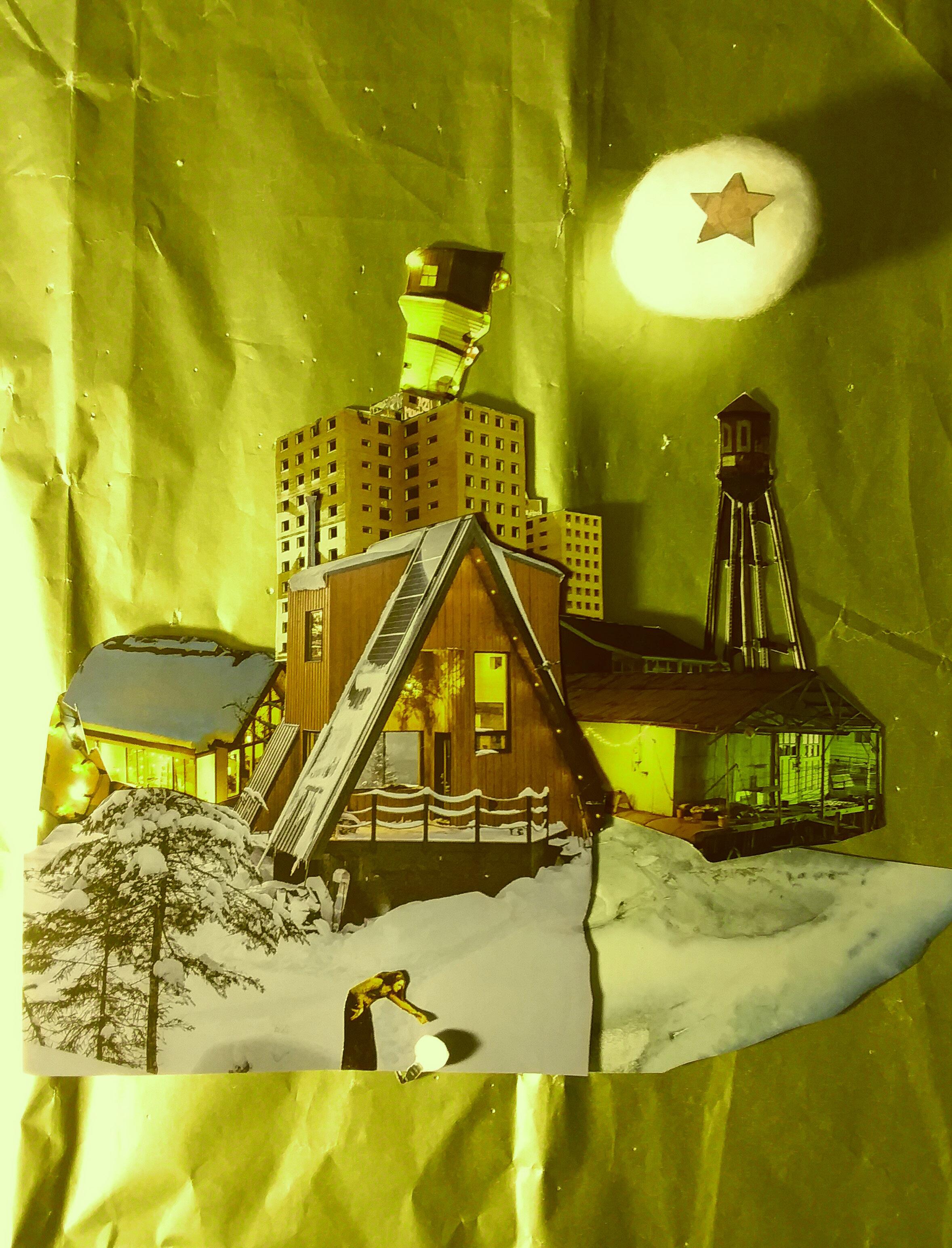

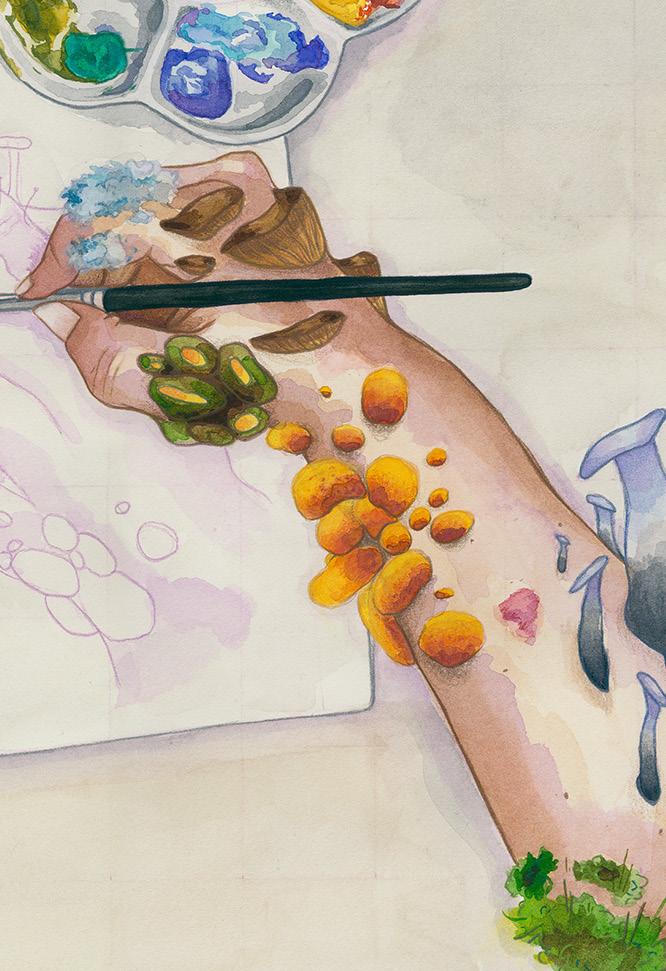

ART 1 2 YOU DON’T ARGUE WITH PARADISE

NO ONE IS BEAUTIFUL IN HEAVEN by James

15 17 37 38 63 77 FAITHFUL by Rendan Lovell WIND by Rendan Lovell CALVES DISCOVER NEW LIFE

AFTER RAIN IN THE SPRING

SKATE

SELFPORTRAIT by

93 107 THE ORDEAL by

UNDRESS

Diaz

Prashant Mishra

by Alaura Garcia 115 116 HANDS GROWING

EXPECTATIONS

COVER ART

DAYDREAM by Cody Morgan

INTERVIEW

30 IN

OUR EDITORS LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Jasmine Ferrufino

POETRY MANAGING EDITOR

Britt Trachtenberg

FICTION MANAGING EDITOR

Mason Martinez

POETRY EDITOR

Alison Van Glad

Sarah Lawless

FICTION EDITORS

Lassiter Jamison

Tabatha Miller

Isha Jain

Jonnell Burke

NONFICTION EDITORS

Emily Townsend

Frederica Danzinger

PLAYWRITING EDITOR

Bailey Peabody

READERS

Thomas Orr

Julia Watson

Shayla Drzycimski

LAYOUT & DESIGN/ PHOTOGRAPHERS

Jasmine Ferrufino

Jack Palmiotti

Dear Readers,

Thank you for picking up a copy of Issue 5. This issue features 24 different creatives ranging in different art and writing forms. This issue is a reminder of what Chaotic Merge is, a merging of different works being unified in one spot representing all of our different perspectives. This issue, although ranging in different formats, touches on common themes. I hope when you read/ see these work(s), you’ll notice the beauty of its creation, the reasoning behind specific placements, and most importantly, the feelings that bleed through the pages. Please take a moment to fully enjoy these pieces and all the heart given to them by the creators, the editors, our readers, and anyone who joined in on the process. Take a piece of us as your read this issue!

Stay chaotic,

Jasmine Ferrufino Editor in Chief

Astroturf

by Kolin

Lawler

Scene 1

Somewhere, deep in the vacuum of space, NELSON and ATTAYA, occupy opposite sides of the stage in imaginary space capsules that are no larger than a sedan. Perhaps they’re represented by rolling office chairs, jungle gym equipment, or cardboard boxes. No matter the case, they are rather low tech and seemingly cost efficient. As the lights come up the two are nervously composing themselves and flickering switches in front of an imaginary screen for their video all.

ATTAYA

Can you hear me? I can see you. Hello?

NELSON

Yes...I can hear you...Still getting a black screen though, can you hear me?

There’s an awkward pause; a technical delay. These are common out in space. NELSON freezes during the duration of said delay. Another delay, this time ATTAYA freezes as NELSON stares at his screen intensely.

ATTAYA

Yes! I can hear you and see you, you’re moving now, and, wow you have such a nice voice.

NELSON

Why thank you. You do as well.

He’s overcome by the emotional weight of human connection.

3 | Issue 5

NELSON (Cont.)

Sorry, I don’t usually cry on first dates. It’s just been so long since-

ATTAYA

If it’s any reassurance, I don’t get many dates out here either.

NELSON

No, not even dates, just, seeing and talking to another person.

ATTAYA

Do you spend much time on general chat?

NELSON

I try to, but it’s not always the most encouraging. Not everyone remembered to bring a webcam, and those who did, those who speak my language, most of the time it’s a lot of crying. A lot of delays, failed connections. Sometimes it’s just dudes jacking off.

ATTAYA

I’ve had my share of those.

NELSON

And the A.I.s? They just make me depressed.

ATTAYA (Deeply sardonic)

Well, before we go forward with this you should know I have quite a robust relationship with my husband, Raul. I designed him myself. He’s got dark spanish eyes and a thick wooly beard. He calls me “Stardust”.

NELSON

Right, so he looks nothing like me?

ATTAYA

Not in the slightest. Maybe that’s why I took an interest in you.

NELSON

Was I just the first person you could reach out to?

Winter | 4

ATTAYA

No, no. I chose you. I wanted you. I still want you. I-

NELSON

No shit?

ATTAYA

There was a certain pain in your eyes. In your picture. And most people have several, usually from back on Earth. But you just had that one. And there was something familiar there, that I feel like I understood? And I mean so far you’re not aggressively jerking off into your webcam, so that’s a plus.

NELSON (With a hint of genuine sweetness) High standards out here.

ATTAYA

Right?

NELSON

Well for whatever it’s worth I think you’re very beautiful.

ATTAYA

Thank you. I think you’re beautiful as well. Have you ever been called beautiful before?

NELSON

Not often. But I believe you when you say it.

Beat. This word has awoken a repressed memory.

NELSON (CONT.)

In high school I used to turn the lights off when I got ready in the morning. Otherwise, I’d stare at myself in the mirror till I cried. For some reason I started to feel beautiful. Which now seems so weird, needed how important that was. Eventually I would look in the mirror, and tell myself, “I am beautiful”, which was the hardest fucking thing for some

5 | Issue 5

Beat.

NELSON (CONT.)

Sorry, I don’t mean to be rambling about myself.

A delay, ATTAYA is briefly frozen

NELSON (CONT.)

Are you still there?

ATTAYA

Yes...I’m here. And it’s okay, I like to listen.

NELSON

Can I ask you something?

ATTAYA

Ask away. I don’t exactly have a lot of hangups out here.

NELSON

Why did you sign up for Space Dates?

ATTAYA

As opposed to just general chat?

NELSON

Well, no. What I meant was, why would you want to go on a virtual date with someone you have virtually no likelihood of meeting or speaking to again?

ATTAYA

Well, I think I just miss the feeling of falling in love with someone, like, truly falling in love. I have this playlist, all of my favorite songs that remind me of that feeling. It’s all so corny I’m sure, but it was my favorite part of the beginning of a relationship. When it felt like it could go anywhere and everywhere. Back in college, I had to walk up this ginormous hill every morning to get to my class. It was freezing. But I was so warm listening to this one song, thinking about Riley, the way he looked at me, the way we kissed, being in the back of his truck-I don’t wanna be too graphic but-

Winter | 6

NELSON

No go ahead. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. You gotta keep these memories alive.

ATTAYA

The way that he would hold me, his skin, his breathe. His body. I would close my eyes and there wasn’t anything else at all, it felt like we were-

NELSON

Floating?

ATTAYA

Well not like this! (She laughs, maybe even snorts) I’m sorry I didn’t mean for that to sound rude.

NELSON freezes for a moment.

ATTAYA (CONT.)

Hello?

NELSON

I’m still here. You’ll have to forgive me. I have a bad relay. I miss feeling that way too. That’s why I made a Space Dates. Sometimes it’s nice just to imagine.

ATTAYA

There’s a song on my list that I really like. I wonder if you’ve heard it. Do you know Blondie?

NELSON

Im aware of her.

ATTAYA

Well, they’re a band but-anyway the song “Dreaming”?

NELSON

Doesn’t ring a bell. How does it go?

ATTAYA

Well, Okay. It’s like: (she sings, it’s quite bad) When, I met you in the restaurant, you could tell I was no debutante... (She laughs) Sorry this feels so weird.

7 | Issue 5

No please keep going.

NELSON

ATTAYA

(She sings again, feigning laughter)

I asked you what’s your pleasure, a movie or a treasure? I’ll have a cup of tea.

(She briefly forgets the words)

Something something.. Dreaming, Dreaming is free

Dreaming, Dreaming is free

That was lovely.

NELSON

ATTAYA

Thank you. I don’t suppose there are a lot of other girls who sing to you in space.

NELSON

No, but I think it’s fair to say you’re the best one this side of the galaxy.

Beat.

It’s strange, it feels so easy being vulnerable with one another.

ATTAYA

It is strange. I don’t ever sing in front of strangers. I just couldn’t-Sorry, are we strangers?

NELSON

Well we’ve been talking for about NELSON (CONT.)

4 and a half minutes.

He checks his monitor

You still keep track of time?

ATTAYA

Well of course I do. Do you?

NELSON

Winter | 8

ATTAYA

I mean, not really. I did. But I guess it really doesn’t matter anymore. Since we’re not rotating around the sun.

NELSON

Cause time dilation?

ATTAYA

Right, it could be 400,000 years in the future on earth for all we know.

NELSON

Not exactly, my clock is synched up with earth’s. And according to my log, I’ve been floating out here for

He checks his monitor again, staring in dismay.

NELSON (CONT.)

Two years, four months, sixteen days, and seven hours.

ATTAYA

But what’s the use in keeping score? Are you planning on going back?

NELSON

To earth? I mean I hope so.

ATTAYA

A while ago I put on an old nature documentary. I couldn’t get very far into it. I just started, bawling my eyes out. Like I never have before. And it wasn’t a comforting cry, it was pure horror. I can’t watch movies anymore. The memories start haunting me and I realize, its gone, all of it.

NELSON

But we don’t know that.

ATTAYA

I didn’t leave early. I waited. Too long. I waited one year, six months, eleven days, two hours, and forty six minutes longer than you did. And when I left, I could hardly recognize the place. The fear, the dread, the faces, as if they were ready to eat each other. I won the raffle. And on my way to the shuttle, they were starving. Furious. Bereaved. They wanted to rip me apart.

|

9

Issue 5

There’s no going back there. Not anymore. Not anytime soon.

NELSON

What’s your plan then?

ATTAYA

Meeting strangers, like you, maybe someone will know something that I don’t. Maybe there is somewhere safe to land out in the nothingness. Because, deep down I still believe that people are good, they just need air to breathe.

NELSON

I’ve been satellite hopping. I follow the wavelengths of nearby satellites, and there are frequencies I tune into, where I’ve heard talks of micro colonies, formed from fellow drifters like us banding together. If I find the right spherical coordinates, maybe I can find others.

ATTAYA

So you believe that, there’s a real chance you can be around other people again, like physically?

NELSON

I have to believe there is. I need to. It’s the only thing keeping me going.

ATTAYA

But what if this is it?

NELSON

This? Like, drifting alone in space?

ATTAYA

What if this was all there is? We dream. Imagine. If we’re lucky we can remember what the feeling was like. But I’m scared I will become complacent, drifting through space, having phone sex with an A.I that looks awfully like a teacher I used to have. And eventually that will be normal to me. All the real things I felt will be forgotten.

Beat.

Beat.

Winter | 10

ATTAYA (Cont.)

Maybe you could help me remember?

NELSON

What exactly do you need help remembering?

ATTAYA

What it was like to be held. To be touched.

NELSON

Maybe you could play that song. The dreaming one. It could help you remember.

ATTAYA

The more I listen to it the more distant the feeling is! If I listen to it even once, I know I won’t be able to stop till it means nothing to me. I hate thatATTAYA freezes, and cuts out.

NELSON

Hello? Can you still hear me?

ATTAYA cuts back in, in tears.

ATTAYA

Nelson? Nelson?!

There’s a spark in NELSON that ignites that we have yet to see.

NELSON

I am here! I hear you, but you’re-Goddamn it. (In tears) I almost forgot the sound of my own name.

ATTAYA

I’m sorry I didn’t mean to startle you.

NELSON

No, you didn’t startle me at all. It’s just, fuck.

ATTAYA

What is it?

11 | Issue 5

You brought me back.

NELSON

Beat.

NELSON

Nelson Elijah Meyers.

ATTAYA

Nelson Elijah Meyers. That’s your full name. Attaya Clarke Madison.

NELSON

Attaya Clarke Madison.

They enter a bizarre limbo of ecstacy. Each repetition grows more intense, as they begin to remember what it was like to be truly alive.

ATTAYA

Say it again!

Attaya Clarke Madison.

NELSON

Nelson Elijah Meyers.

ATTAYA

Attaya Clarke

NELSON

NELSON cuts out and freezes.

ATTAYA

Fuck! Please, please come back, don’t go, fuck!

NELSON

I’m still here, Stardust.

ATTAYA

Stardust?

Sorry, that was really weird.

NELSON

Winter | 12

ATTAYA

No, no, I needed that. Nelson?

NELSON

Yes?

ATTAYA

I don’t know how much longer we have, but I need you to tell me that you love me. And I don’t care if you mean it or not. I just need to hear your voice say those words before you go away forever and are just another memory

NELSON cuts out once again, and is quickly back. He takes a moment and contemplates, breathes deeply, and says:

NELSON

Attaya, I could love you.

ATTAYA

What?

NELSON

I could love you, but you deserve to be loved, truly loved, and held, and kissed, and-

ATTAYA

Maybe there’s a chance?

NELSON

And if not you’ll find someone like me, and I will find someone like you.

ATTAYA

Good luck finding another girl named Attaya.

NELSON

Well, if time and space are infinite, there’s an infinite amount of Attaya’s just like you.

ATTAYA

Well that’s not awfully reassuring!

13 | Issue 5

NELSON

It’s not?

No! But-Well

ATTAYA

Beat.

ATTAYA (CONT.)

If you really think about it, what that means is

ATTAYA’s monitor cuts out completely. NELSON’s side of the stage goes dark. They’ve lost connection entirely.

ATTAYA

Hello?

Blackout. End of play.

Winter | 14

Lilith Fair, 1996

by Abby Hosterman

In retrospect, the lineup was iconic, but what I remember most was the bathroom line was too long to hold it. My mom snuck me into the men’s bathroom. I stayed tightly behind her in an aftershock of patchouli. Keep your eyes down, I focused on my feet not sliding from under me on the oil spill floor and with all the women, their middle parted crooning screams, their bras on fire, I still knew to be scared.

twice over

by Sage Kubis

mid-april: we dig a grave for the cat in the backyard and the earth is so heavy, so clay filled, stuck to the bottom of my boots. your digging boots, she says, digging boots, i say, we laugh, everything is empty and quiet and the sun shines and the radio plays from the house they’re building on the corner and we bury the cat with one hand touching the towel she’s wrapped in so gently and i say This Is Just Her Earth Body, Right, and she says yes but we both stand still and wait. the knees of my jeans are wet..

there comes a point in any major revelation where you stop frolicking in the change and start seeing it for the reality of what it will be, which is to say once the novelty of kissing girls wore off i texted my mother and asked if my grandfather would have still loved me if he were still alive, given that now i’m gay. i do this while i cook eggs and i almost don’t want to ask because it seems trivial and who is she to answer for the dead but she says Of Course and i have nothing else to do but believe it’s true because how is he ever going to tell me otherwise?

loss is disconcerting in its emptiness, by which i mean the spaces left behind are by far the worst. i spend three days thinking at any minute the cat will slink up from the space beneath the coffee table, from under my bed, an elaborate game of hide and seek is all this ever was, that grave we dug was nothing but a tribute, Surprise! Here I Am Please Hold Me. when i visit my grandmother, i think i see him too: we walk in the backfield that’s overgrown since he left us and amongst the weeds i’m sure he’s walking too, maybe hidden

39 | Issue 4

19| Issue 5

by the grass chest-high, smoking his pipe, watching the tree line for deer. i touch the grass with open hands and think if he were here, he would be so disappointed in this.

i don’t remember either of them dying, like my head turned off to see the end, but i do remember the heft of the towel, wow she’s so heavy when she’s dead. my grandmother holding the tupperware full of ashes out to me in the backyard, me turning away. i don’t want to hold what’s left of a living body in my hands, grit seeping under my nails. i would have felt like i was consuming him for days. it isn’t until the cat dies six years later that i understand the closure of the weight of ashes in your palm, spreading them into the garden now neglected, everyone in a scattered ring watching clouds roll in over naked pear trees, jovial in our discomfort and unwillingness to settle in the somber situation. the days after too quiet, adjusting to the space. i don’t believe in god, but i hope they’re in a heaven. i plant flowers and hope he’s watching. both of them, pieces of my heart, shaking their heads while i tear apart the garden.

Winter | 20

characteristics of our charism

by Sage Kubis

1. places and times of silence

across town, someone plays a fiddle on their porch. the wind that smells like summer brings it to me where i sit, high on the porch, holding myself. it is languid, lush, being held in the womb of the sky like this. i think i should say thank you somehow, acknowledge the taste of this being more than i probably deserve. i toy with praying, hold the concept in my hands like water: what if i talked and someone listened? what would it feel like to be heard?

2. cloister appropriate to our life

i pull my knees to my chest in the bath. water rushes into my ears and brings a heartbeat. i loll on my back like a lily pad, endless and silent and so heavy in the still. i wonder what my body looks like from above, in this position. to be a woman feels like two: there is the me in the bathtub, naked and alone, and there is the me floating above and also inside who is saying your knees are too dark. your stomach falls to one side as you lay this way. do you know the left side of your face is more beautiful and as you age the right will get worse? girls don’t look this way. girls who deserve love don’t look this way. look at your flesh. don’t you hate it?

3. wearing of the religious habit

pull clothes clean from the dryer. dog hair lint rolled in a ball goes on the dining room table to be forgotten, thrown away days later. folding clothes feels like slogging through mud. i put on mismatched socks and lay down on the floor. i think about love and i think about creation and i think about the stomach it takes to have confidence in your creation. i think about my mother at 40, four kids in, wearing her own dirty clothes. i pic-

21 | Issue 5

ture God shaping Adam gently, lovingly, not even entirely sure what a body should look like. shaping Adam’s shoulders, knees, stomach, his wet hands with clay sliding slippery down slopes, the intimacy of birth. did He feel the life as it came? i rest my hands on my own stomach. i imagine a child there, under the skin. i think ofhow many miles of arms you must have to give love to all the people you could create. i think about the way my mother had the arms but never thought about the time it takes to extend the love all the way to the end of them, to hold them out long enough for us to feel something, to stay long enough to feel safe. the exhaustion of the constant requirements the human mouth needs is omnipresent. a mother plays God to a house of just-dry clay babies. to play God tastes so sweet. to create is an immense responsibility. my god was my mother. my mother doesn’t believe in God.

4. living community life

red wine on wednesdays on a sticky little patio, dog hair and wet picnic tables and leftover heat lamps from the winter stained with cigarette smoke and rain. i open my mouth to say something but what comes out instead is God, let me be loved by these people. let me see them in front of me and open my insides to scrutiny and let them embrace it with open arms. God, let me say things that will reach down their throats and touch their stomachs, warm them from all the way in there. God God God let me let me let me this is all about me i am hungry like a child i expect these things in return for bringing me here in this place where my skin is never comfortable in this place where my body is something to be learned. my mouth stains and i laugh along and i wonder what my own face looks like from their side of the table. i hold God inside me like a lit match and he burns my throat and pours down my back and sweat droplets cool in his wake, my hair sticking wet to my shoulders. i obsess over unconditional love and i obsess over acceptance especially acceptance from men and i obsess over men, they say men have vagina envy but what i wouldn’t give to close every hole in my body and be the one doing the penetrating, when i picture myself as god i picture myself man because then i could take and take and take and never want for permission to devour whatever i wanted, whole.

Summer | 12

Winter | 22

by Harris PlesKovitch

didn’t have to unfold it to know what it said. “Be Our Guest Chili’s® $10,” stamped “©2014”’ 2014. That was five years prior but felt like a lifetime ago. My chest felt hollow. My hands were steady and my eyes were dull. “I should be feeling more,” I thought. “I should be crying. Open mouthed, ugly crying that leaves you with a headache. Why the hell am I not crying?” I hated myself for not being sad. I hated myself for not feeling angry. I hated myself for not feeling fragile and raw. So, I sat, and I stared, and I willed the tears to come.

23 | Issue 5

I’d gotten the coupon during my junior year of high school. It was early in the morning, about 7:35, but I’d been there since 6:40. The building was decently heated, but every time a bus pulled in, the doors would open and let in the cold fall air. The halls were clogged with students making conversation as they moved towards their first classes. Brannon and I stood along the outskirts of the hallway, out of the way. His hair was messy and he wore his signature purple hoodie.

“You want a coupon to Chili’s?” he asked. “It’s been in my wallet forever.”

I’d loved Chili’s. My family would go once every couple of months when we went out to eat. Maybe I’d be able to get something a little extra with the money saved from the coupon. The thought of a brownie a la mode made my mouth water.

“Does it have an expiration date?” I wondered. It didn’t. Brannon handed me the thick, two and a half by seven-inch slip of paper. It was folded crookedly, its uneven lines bothering me. But the one-minute warning bell rang so instead of fixing it I slid it into my own wallet, thanked him, and left.

The coupon stayed there for a few months, forgotten. How many times did my family sit in a Chili’s booth while the coupon sat in my wallet? Waiting to be used? Eventually it was tossed onto my cluttered dresser to collect dust.

Brannon and I drifted. He shaved his head, I dyed mine. I cut ties with most of that friend group after they let a toxic girl back into the circle. Really, I was angry that Brannon started talking to her again after everything she dragged him through.

I got a new routine, a new best friend, and it wasn’t until a couple months into senior year that Brannon and I began to talk again. On my end, it was right back to “she’s a little sister to me” and “he’s like a brother.” I didn’t realize it at first, but this time I was simply a means to an end. Brannon was interested in my best friend. He was “too short” for her and when he started to realize he didn’t have a chance, we started

Winter | 24

It was folded in half and then in half again, but the tattered edges didn’t quite line up. It was crooked—not at all how I would have folded it. And yet, I didn’t have to unfold it to know what it said. “Be Our Guest Chili’s® $10,” stamped “©2014”

25 | Issue 5

to drift again. We only talked one more time between classes and he was spewing his usual nihilist bullshit. I wanted to be a bit more hopeful for the future.

“I’m trying to find the things worth living for, you know?” I asked him.

“Why?” he asked. “What’s the point?” He’d almost sounded offended.

“Because-”

The bell cut me off and he disappeared into the crowd.

I didn’t chase him.

Winter break came and went. The second half of the school year started as usual. It was the end of the day, a few days into our first week back when the halls were nearly empty. A friend and I were walking in silence. It wasn’t an uncomfortable or heavy silence, but the kind that comes with familiarity.

“I never really talked to him,” he began, “but I’m sorry about your friend.”

My heart dropped. Brannon.

I felt like I’d just been slammed into a brick wall. My heart pounded in my chest and echoed in my ears. I don’t know how I knew, but I did.

I prayed I was wrong and asked, “What do you mean?” I was numb during the car ride home. The rest of the day was filled with forced smiles and small talk with family. I considered bringing it up. But what would I say? How would they react? Would my brother’s enthusiasm for his current school project simmer out? How many questions would my mom ask? Would I even be able to handle those questions?

“How was your day?” My mother asked me.

“It was fine. I got a B on my German test.”

Winter | 26

The coupon still sat on my dresser, a thin layer of dust over it. The edges were more tattered than when I’d gotten it and a tear ran halfway down the center folding. How many times had I looked past it? Reached over it? Shuffled it around with the rest of the clutter?

What’s the point? His words replayed in my head. What’s the point? Finally, the dam broke. A sob escaped my throat and my hands flew to my mouth. “Keep quiet” I thought. “Pull yourself together.” But the tears flowed nonetheless.

I was angry with him. Furious that he’d succeeded this time. He was supposed to be graduating early. He was weeks away from getting out. From leaving this shitshow behind. He’d been weeks away from starting the job he’d dreamed of since childhood.

As angry as I was with him, I was angrier with myself. If he went, I’d go too. I didn’t want to keep the promise anymore and I felt guilty for it. Why had I not chased him that day in the hall? Told him the point of it all? But I hadn’t really known, and if I had, he wouldn’t have wanted to listen. Carefully, I moved the coupon to my bookshelf, stacked with other mementos.

Most of all, I was heartbroken. I’d abandoned my brother and in return he’d abandoned me.

That night I had a dream that I was walking through my neighborhood. I walked up and down familiar streets, looking for something, but I wasn’t sure what. Brannon called my name and I turned around. He was smiling. It’d been a long time since I’d seen him really smile.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“Looking for you,” I realized.

He smiled again and assured me he was there. He wrapped an arm around my shoulders and we started walking again.

I woke up crying. Knowing he hadn’t truly abandoned me, that I was just collateral damage.

27 | Issue 5

I buried myself in school work, distracted myself with a new romantic relationship, and piled on extra shifts at McDonald’s. Whatever filled my time so I didn’t have to think about Brannon being gone. And after a while, it began to work. He didn’t fill my every waking thought. Sometimes I would go days without thinking about him. Most of the time, I was ok.

Nighttime wasn’t always so forgiving. After everyone else had fallen asleep, I’d be up. My clock would show 2 a.m. and Brannon would slip back into my thoughts. I’d mull over the girl that broke his heart. Why couldn’t I have just forgiven him for becoming friends with her again? Why did I allow my anger to drive a wedge between us? Why didn’t I stop him when he asked me that dreaded question? Why? Why? Why?

Tears would flow more often than not. My head and throat would ache from trying to keep my sobs quiet. Why? What’s the point? I’d come up with hundreds of answers for him. None of them quite right, all of them too little too late.

Two years after Brannon, Grandma passed. My mother and I made the long drive back to Illinois. It was a bleak winter; it seemed like every day there was a new record low. It was also Uncle Andy’s record low. He’d been the baby of the family, a Mama’s boy. He’d been the one to stay behind and take care of her in her old age. He’d been the one beside her at the hospital bed. The one who took the interstate as fast as his car could go to make sure she wasn’t surrounded by strangers in her final moments.

A blanket of snow covered the fields surrounding the church. The funeral procession went quickly and lowering Grandma into the ground went quicker. Everyone was eager to get out of the icy cold.

I went to heat up the car and Uncle Andy followed shortly after. His eyes were red and swollen, his beard unkempt, and his coat a size too big. We sat in silence for a minute. As much as he wanted to properly honor Grandma, I think he wanted to leave the cemetery more. I think he was thankful for the cold.

Winter | 28

“It won’t ever be ok,” I told him. “But one day it’ll be more ok. Not today, not tomorrow, not even a few months from now. But one day. And it’ll keep getting more ok. And one day you’ll wake up and it won’t hurt all the time. You just gotta hold out for that day.”

He asked me when I’d gotten so grown up.

My thoughts drifted to Brannon. Some days, I didn’t

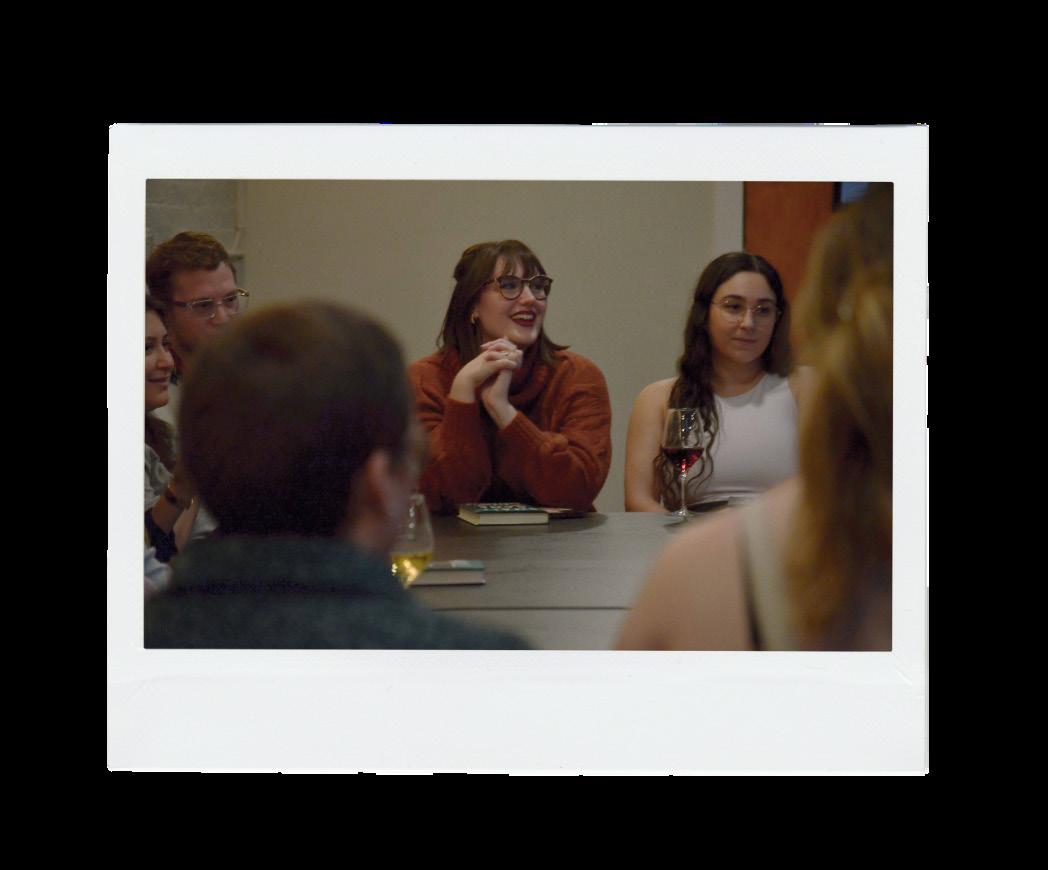

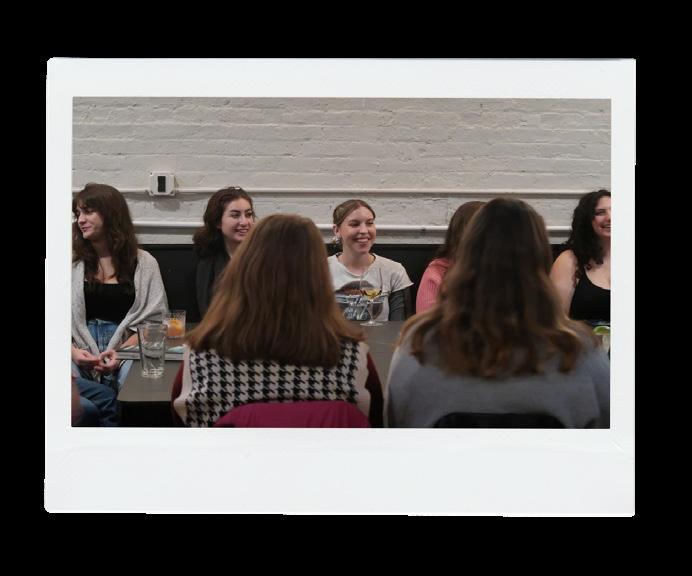

creator of NYC Book Hoes

In Conversation with Zoë Mahler

In Conversation with Zoë Mahler

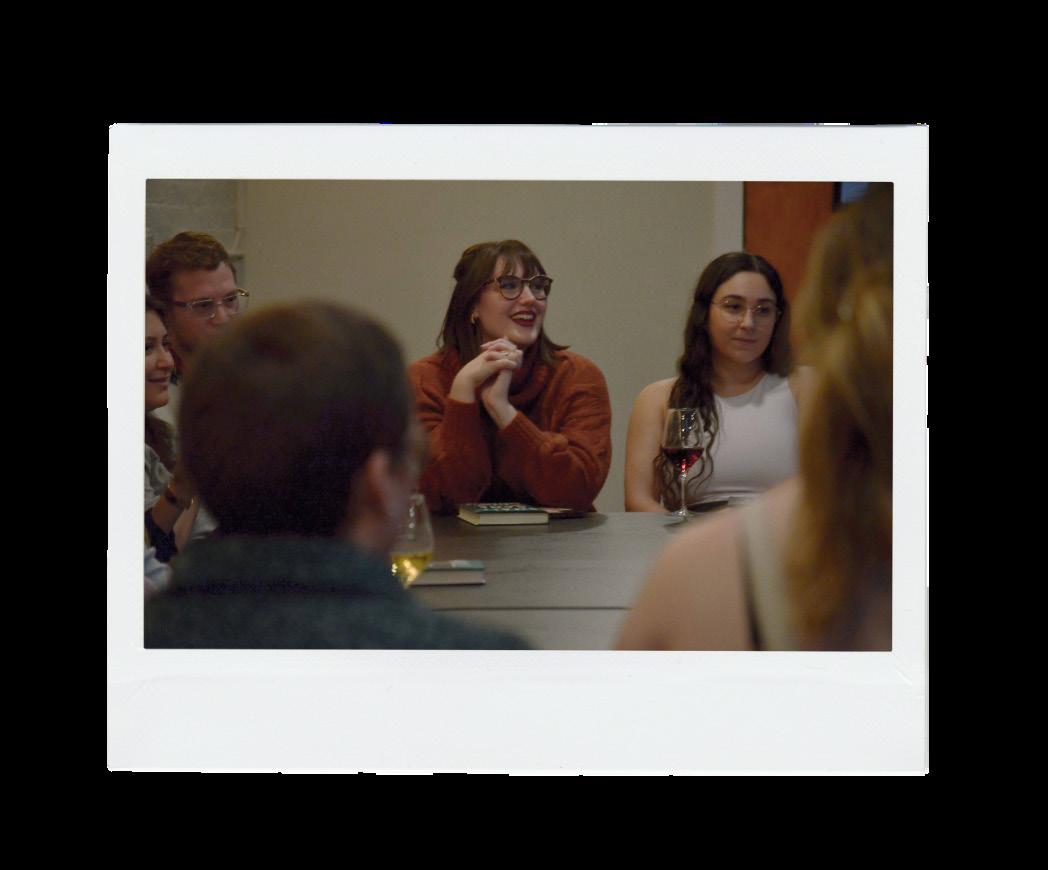

Jasmine Ferrufino: Before NYC Book Hoes became NYC Book Hoes, you were making videos on TikTok with the iconic intro, “Hello, my fellow book hoes,” as you went all over NYC trying to visit all the bookstores. I would love to hear why you started these videos? What inspired it and if you imagined it growing at the speed that it did?

Zoë Mahler: No, I mean, obviously, I had no idea. I started the account because one of my friends lived out of state. And when she came and visited, we hit six bookstores in the time that she was here. And she was like, oh, I’d love to see all these bookstores and explore them. I liked the idea of seeing everything. I was in grad school at the time, so I needed a reason to get out of the apartment other than school, and I also had been living in the city for a good amount of time, but I didn’t feel like with COVID and everything that I had been able to explore and, you know, see a lot of places. So it was a good excuse to leave the apartment and have a place to go. And then I could explore as I went along the way.

When it came to TikTok, I had already visited around 20 bookstores before I started the account. I started it for my friends, thinking it was a private account because I didn’t know how to run TikTok whatsoever. I made a funny little intro that I was like, Oh, she’ll find this hilarious. The first video that I did was the Strand or McNally Jackson because many people already know those, and I figured, why not start strong with the ones she had already seen? And then it blew up. Like, I was not an ticipating it at all. It got hundreds of thousands of views and I panicked and deleted the app, thinking it would delete my account. It did not.

I was planning on putting it on private because I already had, at that time, 3000 just from those few videos, and that was way more than I would ever handle. I panicked, and my friend said, No, I think you should keep doing it.

31 | Issue 5

And see where it goes. I am not one to put my face on the Internet and say, “This is what you should read,” or “These are my thoughts on these books.” I thought it would still be fun to research different bookstores and explore those, and then it wasn’t until two Lower East Side book crawls ago, a random girl approached me and said, I love your TikToks. I saw you. I just wanted to say hi. And I again immediately panicked. I shut down. I was incredibly awkward, but I got her information, of course. And then it wasn’t until a few hours later that I messaged her like, “I’m so sorry.That was so incredibly awkward,” and now we’re best friends. So it spanned from, oh, people are actually watching. She had found out about the book crawl both through me and from, you know, starting to follow bookstores as well.

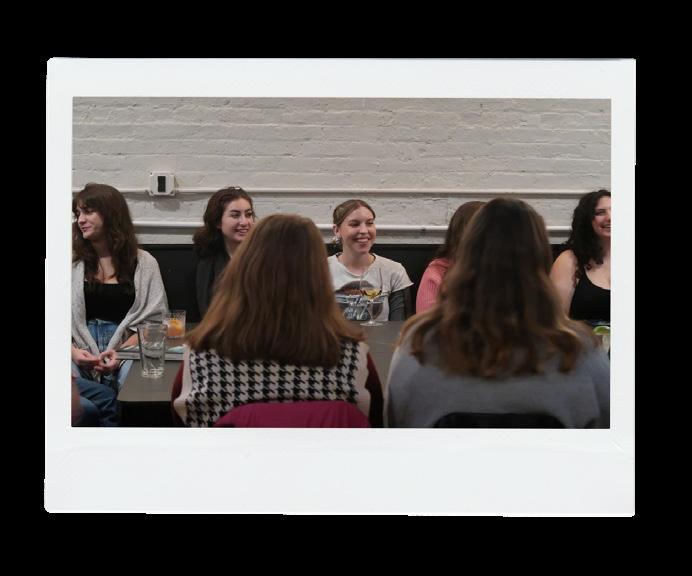

JF: As I mentioned in the first question, NYC Book Hoes has grown, and you are now consistently hosting 5 different book clubs, doing book mixers, and now author events. What made you want to gear your audience and yourself towards event planning & what do you see as the future for Book Hoes?

ZM: It wasn’t something that I planned on doing more than like once a month type of thing. I joined a book club at the bookstore, Book Club, and I loved it. And it was the first time I had put myself out there to meet people. I got there early. I saw that the chairs were in a circle. I panicked, and I left. And then I talked myself into going back. I ended up having a really good time. And now I’ve been going for five or so months. It was the first meeting they had in a long time, like it was their first official meeting, and so that was a really special moment for me, being Oh man, I wish that this had been here a long time ago. When I first moved here, I wished that I had something like this because I made friends there, and it was something to read. As the summer hit, I finished grad school. Honestly, it’s going to sound really

Winter | 32

lame, but I was feeling incredibly lonely. Like I would get up, and I would go to work, and then I would come home, and I would stop at bookstores, and I would eat food, and that was it.

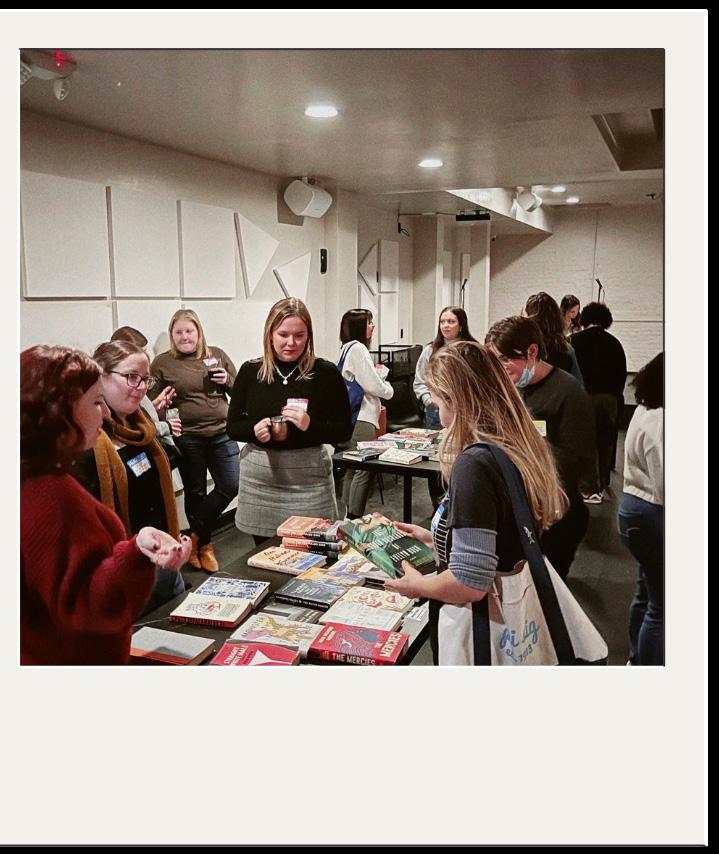

I started to get this idea that I wanted to create a book club because I started attending a few different book events at different bookstores, and I loved seeing all the people there. And so I began to, and I was like, let’s meet in the park. It’ll be super chill. I made one video, I had 40 tickets for two book clubs, and they both sold out immediately. It was such a good time. I met a lot of people who were saying the same thing, like, “Oh, I moved to the city a week ago,” and other people were saying that they had been here five plus years, and it was like the perfect thing for them to get back into meeting people. So those two book clubs were the beginning of it.

The first event that we did was a book exchange and a trivia night. We had maybe 40 people, probably 30. It was fun. We went to the Center for Fiction Literary Happy Hour that they used to have. Then we did a book exchange right before Thanksgiving, like a week or so before. I put a video on TikTok instead of just reaching out to all the people who are already in the book club. I thought there were already so many amazing people at the book club, but it would be great to

to bring in more people and provide people with an opportunity to chat and discuss. And that blew up way out of proportion from what I expected. We sold 170 tickets, and I had never had to cap an event before because I’d never experienced more than 30 people. And so I woke up the following day; I had to call the bar and ask, What is your capacity? Because I’m starting to wonder if we’ve passed it. And they said, You’re good, just don’t sell anymore. It’s just wild to me that people keep coming back, and just the veracity that some people read.

JF: I noticed that your book selection had been geared toward debut books & authors and more unknown books; I would love to hear more about your process in selecting your monthly book club reads.

33 | Issue 5

ZM: And once again, that’s a really embarrassing answer. I am an insomniac. I probably sleep 2ish hours a night. I spend a lot of time on book blogs and reading about what’s coming out and what people are interested in. And it’s hilarious because one of the things I started at the beginning of last year was Book of the Month for the first time. It was like my Christmas gift to myself. Not that I didn’t have access to a million books with all the bookstores surrounding us, but I found a blog that would try and predict what the next month’s books would be, and it would go into debut books. They could be nonfiction and fiction and whatnot. And I became fascinated with authors who I had never heard of or like people who were just putting their first book out there into the world. That concept was so fascinating to me because I realized that I was reading a lot of authors that I just already knew.

And so it was a happy accident because there were two books that I wanted to read over the summer, and that was a book called Groupies by Sarah Priscus. And then How to Be Eaten by Maria Adelmann, and both of them were debut novels. And the conversation that came out of that was intriguing because these are people who have loved reading and have their favorite authors, and they know what they like. And so, reading something new where you have yet to learn what the style will be, you don’t know what they will lean towards with plot and characters, and you’re surprised every time you read. It’s new every single time. And so that became the norm.

Also, debut authors are so accessible. We just had a conversation last night with Nikki Payne, who wrote Pride and Protest. I tagged her in one Instagram post, and she immediately said, I will talk to you guys. I would love to hear everything you have to say. If any of your writers, I’d love to talk about the debut process. In the middle of this conversation, I was like, Who is letting me do this? I have no right to be interviewing this fabulous author. Like, this is insane to me. But it’s like a fun way to know that every time you go in, you never know what you’ll get. BookTok has a very curated playlist. And for someone who is on TikTok, I don’t watch a lot of content. I hear a lot about it, though, from people in book club or whenever I coerce a bookseller at a bookshop into talking to me.

Winter | 34

I met a lot of people who were saying the same thing, like, Oh, I moved to the city a week ago, and other people were saying that they had been here five plus years, and it was like the perfect thing for them to get back into meeting people.

I was not anticipating it at all. It got hundreds of thousands of views and I panicked and deleted the app, thinking it would delete my account. It did not.

It’s always the same stuff, one might call it the Colleen Hoover effect, but honestly, it’s just perpetuated by the same authors over and over again. I didn’t want anybody to feel deterred from attending book club. I wanted everyone to be on a similar playing field when we arrive. Like, this is the first time we’re all reading this author. So it’s been really exciting to see the new things that come out.

JF: You have been running this account since 2021, hosting events since 2022. There must be many great moments, funny dynamics, and hiccups that occurred. Is there anything experience that you associate with NYC Book Hoes? or an event or moment you are truly proud of that came from NYC Book Hoes?

ZM: I’m not a very sentimental person, and I’m incredibly hard on myself. So every single time we have a meeting or anything, I go, that was fine. People might have had a good time. And as I’ve gotten closer to people who are in the book club, they know to text me afterwards and go, I had A great time.

The moment I was moved to tears was the mixer in November when we had 125 people for a book exchange. I set up different tables based on genre so people could drop off their books and take whatever they wanted. We had people come from New Jersey and a girl who came from Connecticut. I was so surprised by how hungry people were for that event. At one point, I had to give a speech, which was terrifying. On the way up, I had two people hand me drinks to make it up there. I slipped into this weird psychosis where I got up there, and I was like, Hello, my fellow, book hoes, and like, there was cheering. And I was like, All right, who’s letting me do this once again? I tried to talk to as many people as possible that night, and I ran out of time. It was supposed to go from 7 to 9, and I didn’t leave until 12:30. But that was a turning point. I think many people realized that it was accessible and available to them.

I tried to start a book club when I was in fourth grade, I invited my whole family, and they were not into it. They did not want to do it. And I had this weird trauma from that. So when I started the first book club and I saw the person walk over I was like, Oh my gosh. Like, it’s actually going to happen. Even if it’s just one person, you know? And whenever people talk about past book clubs in a current book club where they’re like, Oh, do you remember when we were reading this, and we talked about this? That makes me feel emotional because people are connecting to memory and experience, which is exciting. And at our core, we’re all just like a hoe for a good book looking for friendship.

Winter | 36

How to Be Catfished over AIM at Age 14

by Erica Hoffmeister

My first—and only—AIM screenname was created after meticulous thought, after my mom yelled at me a half-dozen times from the kitchen to the den, the one place the desktop computer could be plugged into our landline phone jack. We bought our computer out of a catalog that summer. The summer my grandma died, her death lingering on the shower chair my mother would sponge-bathe her on and in the corners of the paperback mystery novels I’d read to her on our back porch. After she died, I moved back into my own room, after sharing with my sister who was seven years my junior, her room wallpapered floor to ceiling with ancient puke-pink floral, a closet with as many fist-shaped holes through the back of the drywall that it took for me to balance the color out.

It was early fall of the year 2000. New millennium, new me. We had already survived Y2K—the global, technological meltdown that never happened. We had survived freshman year and our first season of formal dances—I wore the backless red dress, tied tight across winged shoulder blades, when polyester dresses and Japanese-print clutches filled rented ballrooms two towns over, our stomachs full of grill-marked, thawed-out steak from a big night out at Steer n’ Stein, not a single date on our minds under hairsprayed glitter barrettes and mom-crafted updos, our hands and arms catching desert-dust in fistfuls out of the limo sunroof. It was a small town. One road in, one road out.

I needed my AIM screenname to be cool, but not obvious. Not give away the hours it took thinking of some

39 | Issue 5

obscure pop culture reference—one unique enough to not need the add-on numbers at the end to distinguish me from the other high school girls with the same ideas. Nothing like my email account, blink182goddess86@Hotmail.com, that would give me away at the first ping of a digital door swinging open. Sitting there at that huge, tacky, particleboard desk, I at last decided on a movie reference. Boiler Room was a relatively recent, obscure enough movie starring early-aught hotties Giovanni Ribisi and Vin Diesel. A film set in New York City—of course—the center of the world on the opposite coast, where people were sophisticated and ambitious and knew things. It was what adulthood was supposed to be like, according to movies like this. What our future held, according to adults like this.

My screenname had just enough letters to complete and check the little box, transform my body through Y2K into adolescence, into adulthood, by transporting my existence across digital planes and through dial-up cables that my mom let me hog only before dinner, before someone might call in emergency. Before emergencies were ever that urgent, no more than making sure dinner was on the table in time for my dad to get home in heavy, concrete crusted work boots. Before homework was at least half completed, before The WB Channel 5 aired my favorite TV show on Tuesday nights, speckled with commercial interruptions, with snack and pee breaks. With enough time to hear that AOL dial-up ringtone just past bedtime to check if anyone left me a response to an equally meticulously crafted Away Message—lyrics riddled with sexual innuendos that I didn’t exactly understand the meaning of.

There was this boy, and of course, he was a popular boy, or this story wouldn’t exist. No stories would, not in the year 2000, anyway. I was letting the hot top ramen noodles bathe in cold puddles of fast-melting ice, to lasso around my tongue in opposing temperatures before I swallowed them whole, then pull each noodle out from my open throat like a sword-swallower. A disgusting habit, a party trick before I knew what party trick and open throat and swallow meant in certain contexts. I was always eating top ramen because

Winter | 40

On this particularly hot, September evening, I signed onto my newAIM screenname: whitecollarcrmnl. It was hot, because it was always hot after our air conditioner blew out the first summer we moved to that little desert valley, and every year thereafter would be scored with box fans pushing orange blossom scent through tangible heat.

41 | Issue 5

we were working class, but as a teenager in a small, suburban town full of comfortably middle-class kids, we just felt poor, because there was a lot of us, and there wasn’t something in our kitchen called a snack cabinet. Just rows of bulk ramen and bowls of cereal that I’d fill and snap a Tupperware lid onto and hide around the house so by Wednesdays, I was the only one that still had breakfast and laughed when my siblings had to finish their week in the free breakfast line in the school cafeteria. I was too busy pretending to be not poor, pretending we didn’t just have internet because I collected all those free AOL Trial CDs, pretended that we didn’t buy our whole computer delivered in a big box—the Encarta CD-ROM collection included—with the money from my grandma’s death, pretended I wasn’t equally excited about reading a digital encyclopedia as much as I was to chat with kids from school on AIM.

On this particularly hot, September evening, I signed onto my new AIM screenname: whitecollarcrmnl. It was hot, because it was always hot after our air conditioner blew out the first summer we moved to that little desert valley, and every year thereafter would be scored with box fans pushing orange blossom scent through tangible heat. That small town that I naively helped my mom convince our family to move to because I had watched Now and Then too many times and thought I’d be spending my summer afternoons riding around on bicycles with pudding balloons in my bra listening to oldies and jumping into reservoirs. That was a fantasy that never conceptualized. Instead, it was triple digits in September, and we had an outdated intercom system and an outdated central air conditioner in that outdated town that we now affectionately describe with the phrase it used to be. And it did—it used to be this way.

I checked to see who was online as a digital door sounded open. It was the sound of potential popularity, of secret notes that could appear and disappear and not be handed to the wrong boy in class, not be intercepted by a teacher, like that time in French class Madame Burke made me read those things Craig B. said about my tan lines showing and made me blush in places I wasn’t ready for. There was no handwriting,

Winter | 42

no pen of choice to tie me to anything. That was the magic of how internet used to be—it was like disappearing ink. Nothing lasted. No digital footprint, whatever that meant. Nothing followed us to school the next day. Nothing was real, we weren’t real, basically nonexistent. The internet then: anonymous.

I remember the boy’s real name, but not his screen name. I remember him sending Hi and then me sending back Hi. He was popular and I was pretending at everything. He was pretending at being a nice boy in return. This was my first lesson with popular boys. With boys in general, now that the millennium was new, that my body was new. Now that I was also learning how to pretend not to care.

I chatted with this nice, popular boy in one-to-twoword messages about Chemistry class, about our teacher who was known to wear tinfoil hats to keep the aliens from sucking out his thoughts, about how shitty it felt to be getting my first ever D because I couldn’t balance the pretending, and the not caring, and the memorizing obscure directors from my VHS rental collection to seem too cool, and the hiding cereal bowls from my brothers, and the avoiding yelling at my dad who was just starting to drink several cases of beer a day again after that very, very brief moment when we thought he had stopped, and the going to Youth Group on Wednesday nights and Sunday mornings and Sunday nights and Friday nights to avoid him, and the yelling, and my brothers, and the yelling, and my mom, and the yelling, and how nice it was to just have the sound of the little pings of our messages after the whole world went to sleep.

And eventually, he said: can I have your email address and I thought: no, no way, blink182goddess86@Hotmail will give it all away. But I had already given it all away. So, we emailed. We didn’t make eye contact in Chemistry class the next day. He was nice and popular and so, he sat in the front. He was probably getting an A. I sat in the back, being too cool, directly in front of the cute, stoner kid who reminded me of my dad with his long, blonde surfer hair and squinted, red eyes. The stoner was more my type, I knew deep inside, but I was busy pretending to be a good girl.

43 | Issue 5

By the end of the week, there was a surprise waiting for me on that bubbled monitor screen that sat in the corner of our faux den with the fireplace no one never really needs in the half-desert, half-valley of Southern California. The fireplace my dad hated because he was a bricklayer by trade, and a really good one, and the previous owners decided to paint over all that precious brick, that damn hard work, with hideous, glopping white paint. Waiting for me in the computer corner beside the sliding glass windows that looked on to a cement patio where my half-dozen younger siblings played and ignored me, under the fruit trees when our backyard was still filled with fruit trees, before the drought, before all the yelling, was a response to my Away Message:

- Do you want to go to the dance with me next Friday?

- It’s the Sadie Hawkins…I am supposed to ask you.

- Well, do you want to ask me to the dance next Friday?

- Yeah, OK. …Do you want to go to the dance with me next Friday?

Nothing. Because then, you could spend all day and all night saying nothing and there was nothing you could do about it. Every digital door could swing closed, and then it was just you, and the loud, slow hum of a tower modem for days at a time.

After the long, quiet weekend, after I cleaned out my ramen stash, after I avoided the nice, popular boy’s eyes all Monday morning during Chemistry class, I got home and checked my Hotmail account.

Why would anyone want to go to the dance with you?

You’re just a big-tittied hoe. That’s the only reason anyone even talks to you. HE was never emailing you. It was S— and D— the whole time, you dumb, big-tittied hoe.

Winter | 44

I loved Now and Then more than any other. I played the VHS until the ribbon wore out, as many times as it’d make me feel dirty for how Devon Sawa and Christina Ricci made me feel in equal measures, in the parts I was taught I wasn’t supposed to feel anything. I didn’t tape down my boobs with anything but my elbows. They seemed to grow overnight that summer before sophomore year, making themselves known during swim sessions every afternoon for summer school P.E. My young step-grandma was pretending to be cool so she bought me my first bikini: bright orange with bright blue piping and a white nylon little turtle with the phrase Speed Kills before I could understand the joke, before I knew my boobs would fill in the triangles and that skimpy little string bikini would define puberty for me forever, my high school reputation forever, categorize me as something other than myself. Because I didn’t want to be Teeny, I wanted to be Roberta. But now they were all just staring at my fucking boobs all the time. I guess that’s what we wanted boys to do. What we were supposed to want them to do. I guess I really was a big-tittied hoe.

I printed out the email. We were out of black ink because we were always out of black ink, and so the text shone in lime green, half-toned dots. Holding the fresh paper in my hands, I knew it was real, what had happened. I held it like a postmarked letter, like a war-torn love letter, like something I could rip up and burn and watch turn to ash into the Santa Ana winds and never speak of again. I handed it to my best friend at school the next day. I said, I’m not going to the dance. I said, I’m going to delete my AIM account. I tried not to cry. I was too cool to care. Because I also knew, by then, that big-tittied hoe was also code for hot girl, but I didn’t want to pretend to want to be either. She said, those guys are assholes. She said, let’s just go to the dance together.

For the two years that followed, until those not-nice popular boys graduated high school, left our half-desert, half-valley town for fraternity parties full of big-tittied hoes and party tricks, before my teenaged body was written into the Senior Will–a contraband document composed by the departing seniors to bequest items to the remaining student body, the curves of my body a gift, an inheritance–not once,

45 | Issue 5

but twice, for being not-taped-down in a way I was supposed to take as a compliment, that I should be flattered by the catcalls and the dirty notes, my best friend called those boys assholes to their faces every time she passed them in the school hallways. We didn’t have to pretend who they were any longer. I scrubbed out the white-out penises drawn on her locker in return. Asshole. Asshole. We never spoke their real names again. When I packed the boxes that would cram my dorm on the East Coast, I traded my neon string bikini for something black, something badass, something new to pretend to be. Unplug the modem, become someone else entirely.

Winter | 46

I Won’t Be That Person

by Sarah Elizabeth Grace

SETTING: An apartment in a major metropolitan city. October 2020.

CHARACTERS

SAM: femme, early 30’s. Openly queer and non-monogamous.

ANNIE: femme, early 40’s. Married to Matt. Closeted.

Playwright’s note: Please have an intimacy coordinator, or at least practice the modalities of intimacy coordination, while blocking this play.

SETTING: An apartment. Early evening, October 2020. There is a kitchen and living room, and doors that lead to a bathroom, bedroom, and front door. The living room has a couch.

AT RISE: Lights are off. No one is home. Then, an explosive opening of the front door.

SAM, a woman in her thirties, bursts through the door, breathless. She flips on the lights. Burning up, she strips off her jacket and shirt, and tries to catch her breath in her bra. She has a tattoo on her ribs.

She rushes to the sink (or grabs a bottled water from the fridge, whatever’s easier for production) and gulps down water.

Hydrated, she steadies her breath. Then, she looks at her phone.

SAM Shit. Shit shit shit shit. 47 | Issue 5

One minute!

She rips out some make-up from her purse and frantically puts it on her face by looking in her blush’s compact mirror. She is battling her face sweat, smoothing out her hair, and desperately trying to look presentable.

Suddenly, there’s a knock on the door.

SAM (cont)

She dabs her sweaty torso with paper towels before throwing on her shirt again. She grimaces as the shirt is still soaked in sweat.

She takes a big breath and opens the door.

ANNIE, early forties, stands in the doorway, smiling. She’s holding a bike helmet and has a backpack on her shoulder.

ANNIE (playful)

Hellooooooo.

They kiss. Then Sam motions for Annie to come in.

ANNIE (cont)

This is so great! I didn’t expect to see you for…well, at least a couple days. I thought you and Chelsea were on vacation til tomorrow?

Annie sets her backpack and helmet down and takes off her shoes as she talks. While she does this, Sam stares at her with a flurry of different feelings she’s trying to hide.

Winter | 48

ANNIE (cont)

I got so lucky with the bike share stations this time. I’m gonna keep riding here as long as there’s no snow on the ground. Fastest way to get to you! Ok. (she’s done dumping her stuff) Hi, babe.

Annie kisses Sam hard.

ANNIE (cont)

I missed you.

SAM (almost teary)

You’re so beautiful, Annie. God, I love you.

ANNIE (touched but also a little concerned)

Sam! I — I love you, too. Are we — are we back to saying that now?

SAM

You can say anything you want. There are no limits tonight. Except for your curfew, I assume.

ANNIE

Oh, yah, I should set a timer. I said I was “going to the climbing gym” so I should leave in like…an hour and a half?

Annie opens her phone to set a timer. As she does, Sam presses herself against Annie’s back, wrapping her arms around Annie and kissing her neck.

SAM (intoxicated)

God, I forgot how you smelled.

ANNIE (laughing)

I biked for forty minutes! You’re sweaty, too!

SAM

No, no, you smell incredible.

49 | Issue 5

Sam voraciously kisses Annie on the lips. She starts to grope Annie, who loves it. Sam is undressing and kissing her body as Annie talks. They’re still in the kitchen.

ANNIE

I have to admit…I was so sad last time, after we saw each other. I respect your boundaries, but the thought of not having this for weeks…it was going to be hard. It’s selfish, but I never want this to stop.

SAM

No off-ramping today, baby. Full steam ahead. Sam puts a hand in Annie’s underwear, warming Annie up for an orgasm.

ANNIE

(losing control)

Babe, babe, let’s go to the couch at least!

They kiss their way to the couch, Annie laying back and Sam on top. Annie takes off Sam’s shirt, still kissing her throughout the process. Sam quickly hops off the couch to takeoff her pants. With the pants off, a tattoo on her thigh is revealed. Sam starts to climb on Annie again, but Annie, seeing the tattoos on Sam’s ribs and leg, sits up and away from Sam.

ANNIE

(indicating the tattoos)

…what are those?

Sam freezes.

SAM

Would you believe me if I said I got them on my trip?

ANNIE

They don’t look new.

Winter | 50

Sam gives Annie a blanket, which is draped over the couch, and starts to pace.

SAM

Ya know, I had to do so much to make this happen. I must’ve had some shitty blinders on, trying to make it here, all in one piece. Because it wasn’t easy. It’s exhausting, in fact.

…our situation?

Time travel.

Very funny, Sam.

You saw the tattoos. I’m not the Sam you know. I’m from 2022.

Ok, well, if that’s true, how the fuck do we go from a global pandemic to having time travel?

SAM

We have a limited amount of time together. You want me to eat that up by explaining it?

Sam continues talking as she gets her purse from the kitchen. She also retrieves the water she drank earlier.

SAM (cont)

One of the agreements with time travel is that anyone we interact with has to take this pill. When you fall asleep, it essentially gives you a “blackout drunk” experience. You’ll forget we ever met up. Any information I give you is useless.

ANNIE (putting it together)

And the timeline stays clean.

ANNIE

SAM

ANNIE

SAM

ANNIE

51 | Issue 5

Sam takes the pill out of her purse and sets it down with the water on the nearby coffee table.

SAM

Right. You’ll also forget the rest of tonight, too. Sorry about that. Might have to rewatch whatever TV you fall asleep to.

Annie nods, wrapping herself up in the blanket a little more. She processes this, then:

ANNIE

Oh my god…do I die? Am I dead when you are?

SAM

I promise you’re alive and healthy, Annie. And so is your husband.

Annie takes in that slight.

ANNIE

And you? You’re ok?

SAM

I’m here, aren’t I? I mean, shit, time travel is fucking exhausting, but you know me. I’m a textbook strong female character. I’ll sleep it off when I get back.

Annie hasn’t seen Sam this world-weary.

ANNIE

What happens, Sam? SAM

That’s how you want to spend this?

ANNIE

My lover just time-traveled here and won’t tell me why. That doesn’t exactly make me wet.

Sam’s face crumples.

SAM

I’m sorry. ANNIE

No! No, no, no. C’mere. Come under here. Tell me under here.

Winter | 52

Annie opens the blanket and makes room on the couch for Sam. Sam shuffles over and becomes Annie’s little spoon, and Annie wraps both of them up in the blanket.

SAM

I just wanted to be with you. When you loved me so much. When things were at its easiest.

ANNIE

You’re shaking.

I never thought I’d see you again.

SAM

ANNIE

God, Sam, you…you love me so much.

SAM (looking at her)

Of course I do.

ANNIE

You now — the 2020 you — I know you like your other partner more. And I understand why. Chelsea is openly non monogamous, like you. She can have you over. Me…I was trying to backdoor our relationship into something legit, but I ran into road blocks. I never thought Matt would turn down the chance to open up our relationship. You didn’t want an affair. So when you asked to “off-ramp” last week — to space out seeing each other, to stop saying “I love you”, to not be so demanding of nudes — I got it. I’d change.

SAM

Annie, you don’t want to change.

Annie shakes her head. She kisses Sam. Sam starts to cry.

ANNIE

The off-ramp?

53 | Issue 5

It lasts two weeks. ANNIE

Oh. SAM

Then I break up with Chelsea before Thanksgiving.

ANNIE

Oh? SAM

Things get intense after that. We see each other all the time, for months. It’s like a fairy tale.

Sam looks away, ashamed to feel so vulnerable. Annie pets Sam’s hair.

ANNIE

That’s what I want, Sam. I love you.

Sam is still not looking at Annie. SAM

You get a dog in March. I realize you’ll never leave him. I break up with you in May, after everyone’s been vaccinated and the world feels like it’s finally real again. ANNIE

…oh. SAM

It felt right. I had some dignity. We thought we could even grow into friends, somehow. We’d be soulmates in our own way. And if it wasn’t sexual so be it. It would be hard, but it was worth it to us. ANNIE

Another off-ramp.

SAM

Winter | 54

SAM

Then you found out you’re pregnant.

Annie is blindsided.

SAM (cont)

Yah, you gave IVF one more shot. Before our break-up. You didn’t tell me.

ANNIE

We tried to get pregnant for years before I met you. Nothing ever happened!

SAM

You say it just like that, too! Takes you months to admit it wasn’t a natural accident but a planned baby Hail Mary. ANNIE

Is the baby ok?

Annie thinks about it. She’s very conflicted.

SAM

She’s great. ANNIE (encouraged)

So you know her? SAM

Not at all. ANNIE

Oh. SAM

You and I try to be friends in the first trimester. But then Matt won’t touch you. And I desperately want to. And you need me so terribly. And you were so beautiful. I fall back into you. And the next five months are the most intense time of all. I’m secretly joining you for walks, coming over when Matt’s out, right up to the week you deliver. Then it ends.

55 | Issue 5

Why would I stay with Matt?

Annie sits up.

ANNIE

Sam sits up, not expecting this.

Annie gets up from the couch, starts putting on clothes as she thinks out-loud:

ANNIE (cont)

He barely has sex with me as it is. And then to wrap me up into some sort of Madonna cocoon when I’m pregnant? I don’t like the sound of those gender roles. And Sam, god, I would love to start a life with you. I’d give anything…(a beat) What did you do? SAM

What did I do?! ANNIE

I would never let you go. You must’ve chickened out. Or Chelsea came back. Or you fell in love with someone with less baggage. But if you had promised to be there for me, for the baby, I would be here, with you, forever. Forever, Sam. Sam stares at her like she’s a ghost.

Sam stares at her like she’s a ghost. SAM

You know what I do? I betray myself. Again and again. Because you never leave. You can’t leave his enthusiasm for fatherhood. His nearby family. His six figure salary—-

ANNIE (cutting off)

That doesn’t matter!

Sam dresses as a means to avoid eye contact as she talks:

Winter | 56

SAM

It will! You’ll get scared. Your impending family life feels inevitable and inescapable. Everyone is sending you baby stuff, organizing meal trains, throwing you showers. None of this includes me. I’m a secret. Still. Certainly not close enough on paper to include me in any of this.

ANNIE

Sam, I couldn’t do that to you! I love you more than anyone!

SAM

Instead of walking away, I tell you I’ll take the scraps. “I’ll take you for as long as I can.” I chop off pieces of myself and offer them to you like the fucking Giving Tree. Because the idea of losing you feels worse than death.

Annie sits on the floor.

ANNIE

No one has ever loved me like that.

Sam takes the pill and the water bottle off the coffee table.

SAM

I’d have been a great step-mom.

ANNIE

I thought you didn’t want kids.

SAM

You changed everything I wanted.

Sam sits next to Annie, still holding the pill and water.

ANNIE

I can’t believe I become the type of person who’d walk away from you.

SAM

You don’t. I had to do it. Almost killed me.

ANNIE

I’m awful.

57 | Issue 5

I wouldn’t be here if you were. ANNIE

I will be awful. SAM

You will…be you. In those circumstances. ANNIE

Don’t make me take the pill. I can fix this. I’ll do whatever it takes. SAM

You’re supposed to take the pill.

And break your heart? SAM

You don’t just break my heart. You almost break me, entirely. ANNIE

Fuck. What the fuck is wrong with me? SAM

Annie, I broke my own heart, too. ANNIE

How can you kiss me, let alone look at me, after everything that’s happened?

SAM

You haven’t done it yet, babe.

She touches Annie’s face.

SAM (cont)

I came here because I missed you. It’s been over a year.

ANNIE

I know, in your present, I’m missing you, too.

SAM

ANNIE

Winter | 58

Sam nods, knowing it’s true, and then offers the pill and water to Annie. She sips the water and takes the pill.

ANNIE (cont)

I’m doing this to follow the rules. But I — I’ll force my unconscious to make this better. Somehow. I love you more than I’ve loved anyone. I won’t turn into someone who’d hurt you. I won’t be that person.

Sam knows this is impossible.

How much time do we have?

Annie looks at her phone.

Over an hour.

Will you kiss me? ANNIE Yes.

Annie kisses her.

Will you make love to me? ANNIE

Yes.

Tell me how much you love me.

Annie takes off Sam’s shirt, and then her own. They make out and desperately touch each other, trying to cover every last inch of one another’s flesh as they continue: SAM

SAM

ANNIE

SAM

SAM

59 | Issue 5

ANNIE

I love you, Sam. I don’t know what I’d do without you. I’m myself when I’m with you. Nothing is more real than us, right now, together…

They start to make love. The lights fade.

SAM

Tell me you’ll save us.

ANNIE

I will, Sam. I’ll remember. I’ll save us. I’ll be brave. I’ll be yours. We can have it all, babe.

Blackout.

END OF PLAY

Winter | 60

when Houston becomes Venice

by Stephanie Holden

The first time the roads became rivers fear had not yet met my trembling lips.

My art teacher standing in the parking lot of my middle school told me to turn around and go home. There was water in the chapel. The stained glass had shattered

in the storm. The first time my house became an island we went to stay with my

grandparents on the other side of town. My uncle in his new pickup truck

drove two hours on a highway turned to mud to bring us a generator for the refrigerator.

I wanted to use it on the TV but the TV only showed more water.

The first time the city became swamp school started again before the neighborhood regained power. My principle sweating through his suit pretended we were explorers discovering the streets for the first time. We wore rainboots to recess. We wondered where the dragonflies had gone.

61 | Issue 5

Debris by Carolyn Martin

foggy morning on I-205 and orange vests black bags pickers gloves unpack themselves from the sheriff’s van a groggy crew sentenced to harvesting coffee cups clamshells cigarette butts soda cans the waste of lives uncontrolled uncontrollable

*

asks a clueless cop why do you vandalize read headlines she mumbled to stained cinder blocks hers not graffiti strokes nor metaphors hers real plastic islands splayed above distraught ocean waves no need to defend or explain indictments was all she needed to say

*

somewhere in a New Jersey landfill vestiges of my mother’s life keepsakes from Poland Egypt France Greece packs of holy cards rosary beads a plastic Joseph without his Mary a button from her husband’s Navy uniform memories he came home safe and stayed *

my uncle the junk man wound his truck through neighborhoods bells rung for metal scraps recycled for the crippled kids housed outside of town decades late frost bite from a Black Forest stint did his legs in a double amputee a six-pack kept him company *

snips of poetry scattered on shopping lists bank receipts and pads from every charity asking for more the weight of waves the smell of sweat and loneliness the speed of rush the length of dark tricked into guilt not always so unwasted words safe waiting for a home

Winter | 62

On Eggshells

Audrey Carroll

She should have been at peace, or else delirious with joy, as she stared out at the miracle that was her child. Instead, Maya stood at the counter with her shoulders tensed, distracted from the cutting board despite the fact that one unintended shift in the wrong direction could have serious and bloody consequences. The white lace curtains filtered the scene in the yard, making it seem gentle and delicate. Her mother-in-law sat on the patio, out of Maya’s eyeshot, but she was keeping watch. Elysia’s little legs dangled from her tutu as she perched on one of the plastic swings that Maya had personally pieced together. Elysia’s head hung as she wobbled to and fro. Wisps of hair moved freely along her rounded face. The girl was barely out of toddlerhood, and the melancholic curve of her back made Maya’s heart ache.

Maya cleared her throat, lowering her gaze to the fruit she was chopping for brunch. She dared to reach forward, not caring about the possibility of staining the lace with citrus as she tugged it to the side. Then she cracked the window open, too, fresh air rushing in. Viscous sweat clung to her forehead and along her spine; it was especially warm for a spring day. Guilt weighed heavy in her gut for making Elysia wear such a thick jacket. She had to protect her daughter, though, no matter how much it pulled at her heartstrings, no matter how much she wanted to abandon all social norms and let her daughter finally be free.

There was a knock at the door; Maya recognized the cadence and the strong scent of heather. It was too early for heather to grow, of course, but this was not a fragrance born

65 | Issue 5

of any garden. Maya settled her knife on the counter, between the cutting board and the platter of freshly baked blueberry scones. She grabbed the nearest dishtowel, wiping her hands and dabbing at her forehead. Though she felt like the living embodiment of frazzled, Maya tried to take a moment to appreciate the sunlight in the room, the way that it reflected off of the pale yellow walls and made everything bright and cheerful. That was, she knew, the façade that she had to project for the day, no matter how much her nerves protested on the inside. Hoping that her hair and makeup was not too much of a mess, Maya took a steadying breath and headed for the front door. She did not mind having the family over, but her brain did activate a certain panic button when she was the one in charge of hosting duties. She was glad that Thanksgiving was her mother-in-law’s job, and that Christmas was her sister’s. Maya picked at a thornlike cuticle on her thumb just before she reached the front door and opened it.

A tall pale woman stood before her. Her golden hair was in an elaborate braided crown on top of her head. Her green silk dress spilled to the ground all around her. Her wings extended past the door frame, and they were taller than she herself was, the sheer appendages iridescent, catching the light like a prism. She had the extreme and regal presence of someone who expected to be seen in a room—seen and heeded. Her eyelids lowered slightly as she regarded Maya, the faintest curve to her lips. In her arm, she cradled one of the willow baskets she always brought. This time, it was overflowing with oranges.

“Rosmerta,” Maya said, monotone. She turned and walked back to the kitchen, knowing that the woman on her doorstep would surely follow.

The door closed behind them. Rosmerta did not make a sound; her feet never betrayed signs of her presence. It might have been disturbing if Maya hadn’t had quite a while to get used to it. As it was, the strangenesses that Rosmerta brought with her were simple details of their lives. Without pausing anywhere else, Maya returned to her station at the cutting board and resumed her work, cubing the last of the pineapple and shifting right along to the strawberries.

Winter | 66

The question was simple and innocuous, but it sent a chill down Maya’s spine. The fairy had asked that question before, during the months when Maya would check ten times a day to make sure that she was not having another miscarriage, and then it would inevitably come and a bitterness for the world would corrode some intangible place deep inside her.

67 | Issue 5

She was making every effort to keep her head down and focus. But, in her periphery, something invaded her waking world: a thin white shell, cracking in ten places along a single curved line, the thin white membrane dangling in the gaps. As Maya’s head snapped up, she remembered the blood—pink veined with red—and it was so vivid that she thought she might have lost a fingertip in her confusion. Maya squeezed her eyes tight, taking three shallow breaths before opening them again to the realities of lace and bloodlessness. The hair that Maya had so carefully pinned half-up was defying its confines, lingering in her face like mosquitos on a muggy night.

“Happy Mother’s Day,” Rosmerta said. Her voice had a quality such that Maya couldn’t tell where in the room the woman stood.