The military prowess of Sultan Süleyman I

page 4 By

Ariella

To what extent was Peter I successful in making Russia a great Empire?

page 10 by Yeva

The legacy of Nur Jahan among the Mughal Empire

page 10 by Aurora

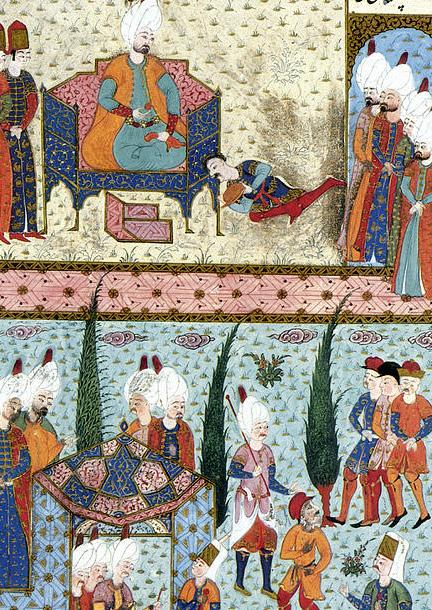

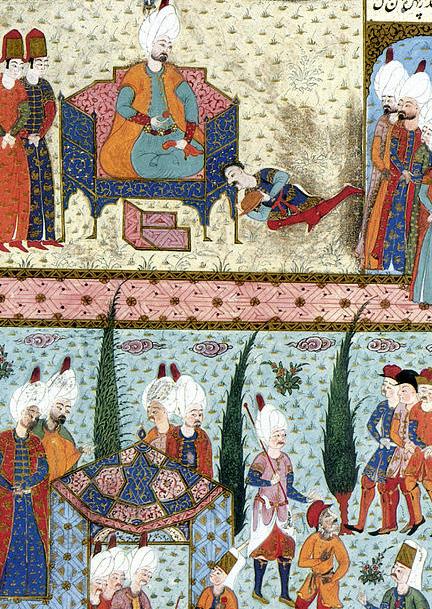

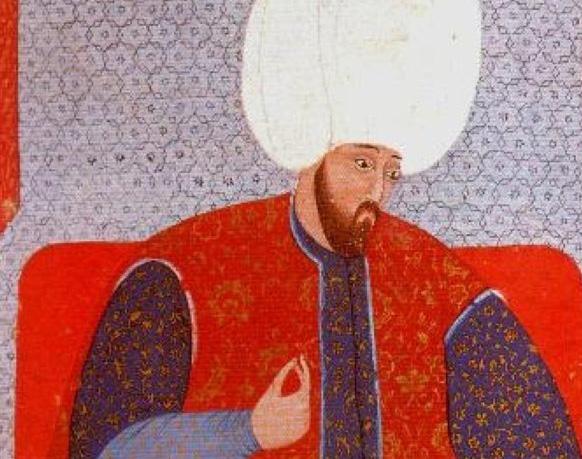

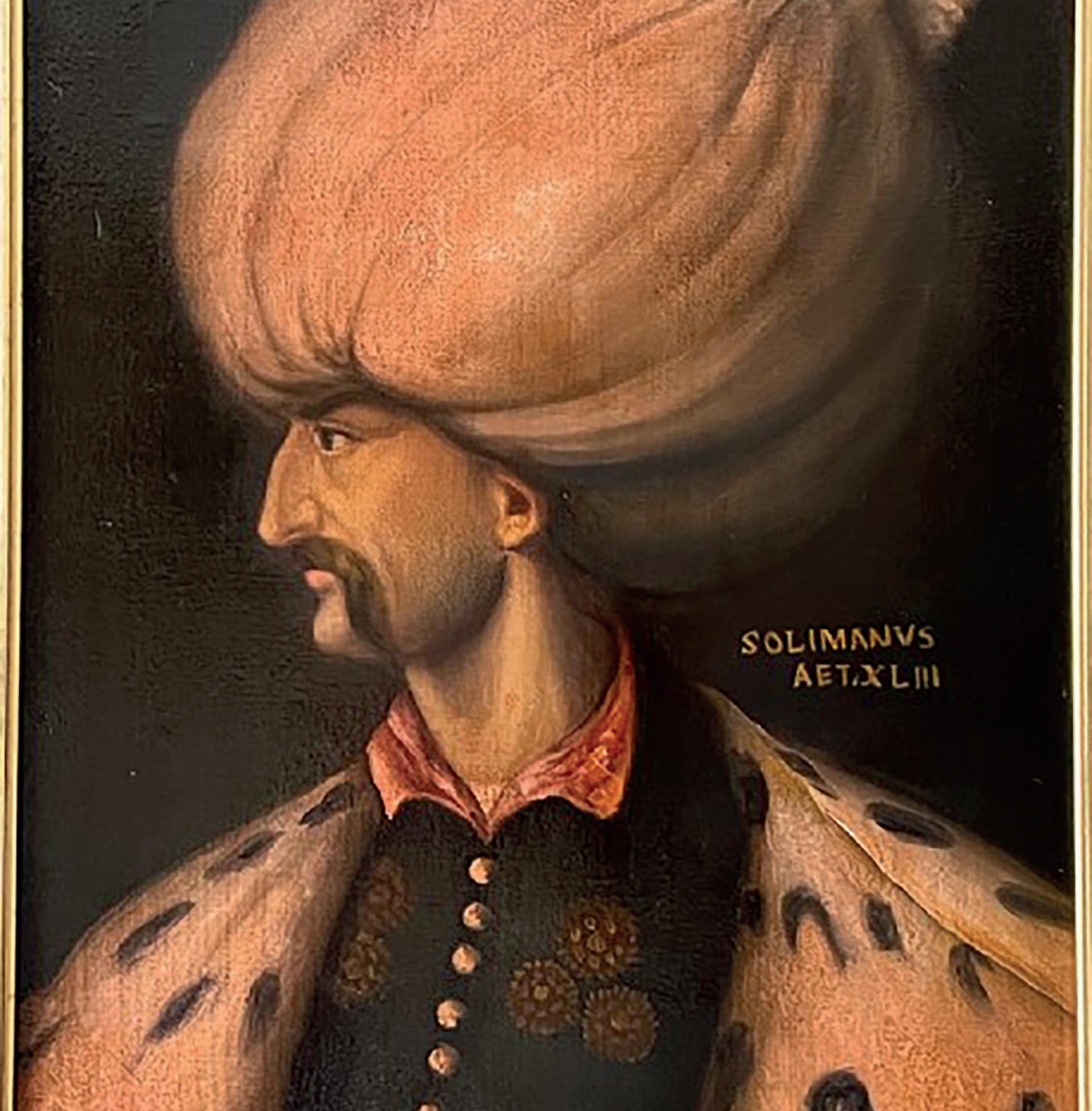

Front cover image: Suleiman The Magnificent (c1494-1566)

History Journal Editor and designer: Wendy Devine

History Journal Co-editor and co-ordinator: Jennifer Kung

Ariella: I wanted to research Süleymain 1 because my father’s maternal family were statesmen in the Ottoman Empire. In particular, my great-grandfather eight generations removed was Haim Farhi, the Grand Vizier of Southern Syria and Northern Israel, who resisted Napoleon’s siege of Acre of March in 1799. Inspired by this aspect of my lineage, I investigated the Ottoman Empire more broadly. Through this process, I became fascinated by the rule of Sultan Süleymain I and how his militaristic abilities and intelligence would shape the Empire for several centuries to come. Although the wide breadth of the subject area posed a challenge, I appreciated the opportunity to conduct research in my own manner and formulate my ideas in this way.

Aurora: I chose this topic because I was intrigued by the character and experiences of Nur Jahan as a woman living in and ruling the Mughal Empire, an era I knew very little about, whose story has been repeatedly shaped by those who told it. The research was challenging because of all of the knowledge needed to understand the context of her life, but I really enjoyed learning about Nur Jahan and later the different layers involved in the construction of her story and overarching significance.

Yeva: I chose the topic of Peter the Great because I was interested in exploring the other side of the argument, rather than the commonly accepted one. Peter the Great is usually portrayed as a moderniser, thus ignoring his controversial policies. I speak Russian fluently, and analysing primary sources or reading the original pieces is both accessible and enriching. Writing the article helped me improve my research skills, particularly in examining which sources are reliable. This experience also benefited my essay-writing skills, especially when it came to the evaluation of the facts and linking them back to the initial point. My biggest challenge was trying to present arguments for a perspective I don't really agree with; this encouraged me to develop intellectual flexibility and strengthen the objectivity of my article.

By Ariella

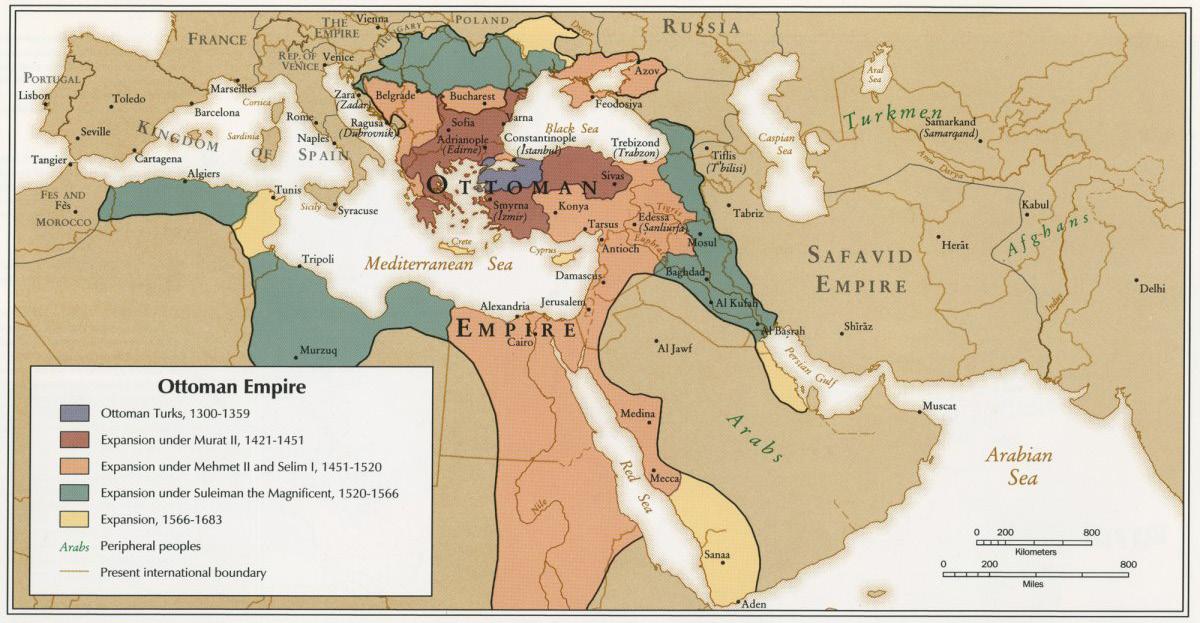

This article aims to discuss the reasons for the expansion of the Ottoman Empire during the rule of Sultan Süleyman I “the Magnificent” – 1520-1566 (Parry 2019). The motivation for this particular focus within this article is that Süleyman I experienced the most notable period of expansion for the empire, and is consequently regarded as ‘the embodiment of the so-called Golden Era of the Ottoman Empire’ (Wigen 2013, p.50). Although I will examine several factors that were of importance to the empire’s expansion throughout the rule of Süleyman, this article will evidence my research into and understanding of Süleyman I’s military prowess as the most fundamental factor.

Introduction

Wigen argues that given the concept of an ‘empire’ only emerged in contemporary discourse in the nineteenth century, it is somewhat inappropriate to define the legacy of Osman I in this manner (Wigen 2013, p.56). Perhaps it is more accurate to refer instead to the emergence of an Ottoman State in 1285 (Bulut 2009, p.792). Despite its fluctuations in prosperity, Cay emphasises how over half a millennium of existence in all meant that the Ottoman State had a considerable impact on redefining the contemporary world (Cay 2022).

Sultan Süleyman I came to power following the death of his father, Selim I, and oversaw more than 40% of territorial expansion; such territorial gains were the result of battles commanded by the “Magnificent” Sultan. These included the Siege of Belgrade in 1521 and the Siege of Rhodes, which began in 1522 (Bunting 2024). Süleyman I sought an increase in territory, power and influence of the Ottoman State. The tenth Sultan was ultimately successful in his aims and is credited with enabling the Ottoman Empire ‘to become a world empire extending from Eastern Europe to the Indian Ocean in the 16th century’ (Wigen 2013, p.44).

The following ideas in this article will discuss the factors that led to this expansion and aim to generate a debate for Süleyman’s military prowess as the most significant of these.

Sultan Süleyman I is renowned for his frequent and extensive military campaigns. He developed an army of 100,000 troops to increase the territories of the Ottoman Empire (Welsh 2022). Despite the size of this army, (which was considerably larger than many of those of his counterparts in Europe, the Middle East and Asia) prior to Süleyman’s rule, Jugundo suggests that the Ottoman troops were not well-organised and lacked discipline (Jungudo 2024). Consequently, it was Süleyman himself that ‘oversaw the substantial transformation of the

Ottoman army into a powerful force’ as he recognised that the successful expansion of the Ottoman State could only be achieved with a more professional army (Jungudo 2024). As a result, Süleyman established the ‘Nizam-i Cedid’ (New Order)’, which demanded that troops were to be trained at a military academy (Yapp and Shaw 2018). These troops were referred to as ‘kapıkulu’, and they were given supplies that aimed to consolidate and reinforce their loyalty to the Sultan (Britannica 2019). As well as these military reforms, Süleyman also fostered the strength and militaristic power of the Janissaries. The Janissaries were men who were born Christian but who had been brought as boys to Turkey and converted to Islam, after which they underwent

intensive training. As a result, Janissaries were highly skilled fighters, directly dependent on Süleyman and his favour, and they suffered relatively little losses throughout Süleyman’s rule (Yapp and Shaw 2018). The ‘Magnificent’ Sultan’s transformation of Ottoman troops also included developing ‘regiments called “corps”, [which] were led by experienced officers’ (Jungudo 2024). As such, not only did the sheer number of Ottoman troops far exceed that of their rivals but also the military prowess that had been enhanced through the work of Süleyman enabled him to make significant territorial gains, thus leading to considerable expansion of the Ottoman State between 1520 and 1566.

The military prowess of Süleyman can be understood further through the

aforementioned Siege of Rhodes in 1522. As a result of the Ottoman-attempted takeover of Rhodes more than 40 years prior, in 1480, the Greek island was thoroughly guarded and Grand Master Pietro d'Aubusson had ‘spared no efforts in keeping himself advised of the movements of the Ottoman fleet and of the intentions of the Ottoman sultan’ (Brummett 1993, p.519). Accordingly, intelligence that there were Turkish ships in the Mediterranean sea was received by the Grand Master himself and, as a result, several ships were seized (Brummett 1993, p.519). Despite this, the Ottomans prevailed. Süleyman I had ensured that his military forces would be in a stable position to successfully attack Rhodes: he had doubled the size of their fleet (from 1480) and he had prepared a force of more than 75,000 troops (Bunting 2024).

The tenth Sultan conducted a siege for five months, in which he initially commanded a blockade of the harbour and a bombardment of the city using cannons, with limited success. Süleyman resolved to attempt exploding mines under the walls, showcasing both his determination and ability (Bunting 2024). Thwarted once again, the ‘Magnificent’ Sultan was not deterred and persisted with the Siege, trialling new military strategies and tactics, including peace talks, in which he initially displayed a willingness to negotiate. Süleyman’s perseverance and intelligence were key in the ultimate fall of Rhodes on 18 December, which was surrendered by the Grand Master in order ‘to avoid loss of civilian life’ (Bunting 2024). This was a significant territorial gain for Sultan Süleyman I and for the Empire, as well as the Siege of Rhodes providing a clear example of Süleyman’s military prestige and successes.

The Siege of Rhodes illustrated Süleyman’s determination for the expansion of the Ottoman State, as well as communicating to his European rivals the degree to which he pursued his goals. As a result of his military

success in Rhodes, Moncure expresses how Süleyman was simultaneously able to expand the Ottoman Empire and demonstrate the state’s strength (Moncure 2019).

Likewise, the Ottoman siege of Belgrade in 1521 evidenced Süleyman I’s military capabilities, as illustrated by his strategic focus on the city. Belgrade, like Rhodes, had resisted Ottoman control for decades and it provided a crucial gateway into Central Europe (Özkan 2021). Sultan Süleyman I developed logistical plans for the siege with his men and utilised his knowledge of artillery to apply pressure to Belgrade. Ottoman artillery had developed crucially since the rule of Sultan Mehmed II. Süleyman capitalised on these developments and managed a systematic and prolonged bombardment. This involved the use of large-calibre cannons, troops of around 100,000 and a constant bombardment of the city (Marko Popović 2019). Sahin proposes that Süleyman’s military capabilities were the primary driving force behind the success in Belgrade (Şahin 2023), thereby exemplifying the importance of the tenth Sultan of the Ottoman Empire’s military prowess as an explanation for the expansion of the Ottoman Empire.

As well as the Ottomans almost immediate success - the city was taken over within two months (“Alaturka” 2025); Süleyman’s successes in Europe elucidated to current and potential rivals of the Ottomans his capability and ambition. Consequently, through his military prowess and success in the Siege of Belgrade, Süleyman I was better positioned to expand his Empire, as a result of his growing reputation.

Focusing on the character of Süleyman is also significant when discussing the expansion of the Empire; Stewart indicates that he was viewed as a skilled ‘warrior, a builder, a man whose appetite could not be quenched by possession, but who was preoccupied by possessing’ (Stewart 1988, p.438).

This depiction of Süleyman I perhaps provides an understanding of his character and the manner in which he viewed himself and that others viewed him. It is indisputable that his rule marked the ‘Golden Age of the Ottoman Empire’ (Wigen 2013, p.50) and, hence, his success is revered by Europeans through adorning him the title of ‘The Magnificent’, whilst those within the Ottoman State nicknamed him ‘Kanuni’ Süleyman or ‘Lawgiver’ (Parry 2019). These aspects of Süleyman’s character are important, both in understanding his impact on the 16th century world, and for appreciating his military success. Despite being ‘preoccupied by possessing’ (Stewart 1988, p.438), the manner in which Süleyman is still revered indicates a nuanced character; one that we can reconcile with the man who provided the Janissaries with large donations and allowed those who had been exiled by his father (Selim I) to return home (“ExtraHistory” 2016). Consequently, through Süleyman’s personal military success (he, in fact, rode at the front of the Ottoman’s militaristic pursuits for the majority of his reign) and the potentially admirable aspects of his personality, it is conceivable that he was able to cultivate a cult of personality (Rüzgar 2019). He attracted extreme followers and worshippers, which he undoubtedly embraced, even proposing ideas of himself as the ‘Second Solomon’ (Mackey 2016). Süleyman’s military prowess was predominantly displayed in the early years of his reign, in particular through his initial successes in Belgrade (1521) and Rhodes (1522-23). Despite fluctuating levels of success throughout his rule, most notably his frequent unsuccessful attempts to capture Vienna, his strong militaristic nature was emphasised through his consistent pursuits to extend his Empire into Asia and Europe. Whilst it is true to say that his strength of personality was important in expanding the empire, it did so as an enhancement of his military prestige and

would not have been such a significant factor had Süleyman not been so militarily successful.

The military prowess of Sultan Süleyman I was also reinforced through the technological developments of the mid-16th century. This included advanced weaponry and machinery, for example the ‘siege train’, ‘which enabled the Ottoman army to besiege and take defended cities’ (Welsh 2022). Welsh shows how this piece of equipment consisted of substantial, yet easily adjustable weaponry and had the ability to attack heavily guarded European fortresses effectively (Welsh 2022).

Since expansion within Europe was Süleyman’s primary aim throughout his rule, there are many reasons that can be discussed as to why the Ottomans were able to use this technology in a constructive means. The main explanations that I will focus on, and that I will further explore later in this article, are that of the limitations of Christendom and the diversity of the Ottoman State. Christianity had been maintained as the predominant religion throughout Europe in the 16th century and, while the Protestant Reformation began to extend throughout the

continent, the Catholic faith upheld its precedence (Spaulding 2023).

Accounting for the traditional views of Catholicism, it is understandable that there would have been some concern over new technological approaches and whether the studying of certain scientific practices conflicted with religious ones (“Science and Religion in the Early Middle Ages” 2009).

Consequently, advancements in technology were less frequent in Europe than in the East, due to a fear of demonstrating a lack of belief in God. Whilst scientific discoveries were made in Christian Europe and technology was available to them, the Ottomans were renowned for utilising new ideas and technologies to improve their military prowess. This is attributed partly to the other key idea: the diversity within the Empire. Among the controlled nations of the Ottoman State, there were significant populations of a wide range of religions, ethnicities and cultures (Palmer 2011). Many of these had access to other countries and new ideas and were able to develop scientific knowledge and technological developments within the Empire. Although the social and cultural elements of the Ottoman Empire

made significant contributions to their expansion, it was ultimately the military prowess of Sultan Süleyman I and the successes that he was able to achieve between 1520-1566 that were the primary reason for the expansion of the Ottoman Empire.

The contribution of trade throughout the rule of Süleyman I established a foundation for the development of commercial diplomacy, which resulted in the economic and geographical growth of the Ottoman State. In fact, Süleyman viewed trade as beneficial to the expansion of the Empire; consequently promoting it through changes to his taxation policies (TutorChase 2024). Indeed, Bulut suggests that it was such ‘policies of the Ottomans facilitated their expansion’ (Bulut 2009). All significant developments in trade during this period can be attributed to Süleyman I as he would have ‘controlled the system by ratifying guild regulations, fixing fair prices in markets, controlling weights and quality, and regulating purchases and sales’ (Bulut 2009, p.795). These processes, whilst assisting indirectly in the expansion of the Empire, primarily aimed to stabilise the economy of the Ottoman State. This is evidenced through Bulut’s proposal that the main objective of the Ottomans was the creation and maintenance of ‘a balanced domestic economy’ (Bulut 2009, p.813). This desire for stability is emphasised through the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire’s tendency to favour imports over exports in trade (Mardin 1969, p.262). Mardin emphasises this through expressing that the higher quantity of imported goods was the result of a twelve percent duty tax on exports, whereas there was only a ‘3% duty on imports’ (Mardin 1969, p.262). The consistency of such taxation policies allowed the people of the Ottoman State to generate enough wealth to sustain themselves and maintain their lands, which, in turn, preserved the stability of the State (Mardin 1969, p.262). Moreover, Süleyman I granted the ‘tebaa’ – his subjects/flock (Wigen 2013, p.45) ‘significant trading privileges’, including ‘rights to trade in the empire, under imperial protection, and a reduction in custom duties’ (Bulut 2009, p.800). These policies were all relatively low-risk strategies that strived for economic security and resulted in positive outcomes, but the expansion of the Ottoman Empire during Süleyman I’s rule was predominantly a result of his high-risk strategies, such as his militaristic policies (TutorChase 2023).

An example of this is the island of Rhodes, which for centuries obstructed a key passage of internal trade between Greece and the rest of the Ottoman

Empire, yet was ultimately captured by the Ottomans at the start of Süleyman’s rule; demonstrating how militaristic success enabled trade and the Ottoman economy to prosper (Brummett 1993).

The role of trade during the rule of Sultan Süleyman I was not limited to the confines of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, it was primarily international trade that allowed for the expansion of the Empire between 1520-1566. This was often as a result of military success, which had allowed for the ‘increase of Ottoman control over major trade routes’ (Mardin 1969, p.310). Indeed, trade between the Ottomans and Asia, Africa and Europe developed significantly throughout the rule of Süleyman to the extent that Bulut reasons that ‘by the middle of the 16th century the Ottoman Empire had become the dominant state controlling all the trade routes from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean’ (Bulut 2009, p.792). The globalisation of trade allowed the Ottoman State to increase its economic power, as well as spreading its influence among nearby nations (Yapp and Shaw 2018). However, ultimately, territorial gains had to be won by force and this therefore required militaristic pursuits.

Nevertheless, many aspects of the Ottoman Empire contributed towards its expansion. This included the skills and abilities of the ‘tebaa’, such as Jewish people, who while suffering the second status restrictions and impositions of being ‘dhimmi’, were tolerated in the State and were accustomed to trade (AlQattan 1999). As well as this, AlQattan expresses how Jewish people living in Ottoman-controlled regions would likely already have connections to those in other countries and therefore assisted significantly with the development of trade during this period (AlQattan 1999). Despite the significance of global trade and subsequent financial gains, the militaristic mindset and achievements of Sultan Süleyman I were ultimately responsible for expansion of the Empire between 1520-1566, since, as evidenced, successful trade and control of the trade routes were a result of Süleyman’s military expansion.

One of the most fundamental aspects to the Ottoman Empire was its Islamic principles (BBC 2009). Despite Süleyman not having originated from a particularly Orthodox background, Anscombe attests that Islam served as a unifying force that allowed for cohesion with the Ottoman Empire and consequently enabled its expansion (Anscombe 2010). This was especially evident during the rule of Sultan Süleyman I, as during the 16th century, discontent among other religions, namely Christianity, meant that the unity of this ‘great Islamic Empire’

was particularly significant (DailyHistory 2025).

Accordingly, the Empire was fundamentally Muslim and the Ottomans regarded themselves as fighting in the name of Allah (Anscombe 2010). Nevertheless, unlike Europe Christendom, the Ottoman State tolerated many religious minorities, including Judaism and indeed Christianity and provided them with a measure of autonomy (AlQattan 1999). Conversely, the Protestant Reformation that had begun in Germany and was exacerbated by Henry VIII in England, facilitated a divide within Christianity in Europe (Wilkinson 2022), thereby providing a clear juxtaposition with Süleyman’s goal of religious unity. In fact, Rogan would even propose that it was this religious unity, amongst other facts, that ‘contributed to the Ottoman Empire's institutional strength, territorial expansion, and economic prosperity’ (HistoryExtra 2021). Although a shared Muslim ideology united the Ottomans and provided them with a significance and purpose, their Empire was home to more than 75 distinct ethnic groups’ (Palmer 2011).

Therefore, while the unity of Islam was significant, the Empire was ‘administered based on the secular decisions of the Sultan’, suggesting that the significance of religion in the expansion of the Empire was limited (Labib 1979). In fact, what was perhaps of more significance was Süleyman’s willingness to ally with states, regardless of their religious beliefs. Through belonging to the Muslim faith, Süleyman was able to make strategic alliances with states such as Protestant England and Catholic France regardless of their differing views on Christianity.

Despite the advantageous nature of

the Islamic State, Ottomans did have divisions of their own, albeit more as a result of social class. These were the ‘askerî’ (aristocrats) and the ‘reaya’, which comprised both Muslims and non-Muslims and were considered to be largely uneducated masses (Mardin 1969, p.259). AlQattan proposes that the dichotomy between the ‘askerî’ and the ‘reaya’, as well as the significant ‘dhimmi’ Jewish and Christian populations, meant that the Ottomans’ ability to be a fully cohesive State was restricted (AlQattan 1999). Although there were rarely internal disputes and ‘these religious communities were granted autonomy over their internal affairs’ (AlQattan 1999), the diversity of beliefs that existed within the Ottoman Empire ultimately meant that the unifying force of Islam and the State’s tolerance of other religions were not as significant as the military prowess of Süleyman for the expansion of the Empire between 1520-1566.

In conclusion, the Ottoman Empire was a vast and complex empire that was multi-faceted and there is no single explanation for its expansion, even when only focusing on a select time frame. Despite this, there is much evidence to suggest that the military prowess of Sultan Süleyman I and his troops’ military successes played a vital role in this expansion. Undoubtedly, developments in trade, economic growth and technology were significant, as was the role of religion, yet none of these factors, nor even Süleyman’s overall personality, had such obvious and sustained success in expanding the Empire between 1520-1566 as that of the military prowess of Süleyman and his troops. n

Alaturka. 2025. “Belgrade - Ottoman Conquest and Turk Wars.” Alaturka.info. PE. May 13, 2025. https://www.alaturka.info/en/ macedonia/ohrid/188-deutschland/nordrhein-westfalen/4958the-ottomans-were-leaving-belgrade-a-changing-city/en/serbia/ belgrade/4301-belgrade-ottoman-conquest-and-turk-wars/amp.

AlQattan, Najwa. 1999. “Dhimmīs in the Muslim Court: Legal Autonomy and Religious Discrimination.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 31 (3): 429–44. https://doi. org/10.2307/176219.

Anscombe, Frederick E. 2010. “ISLAM and the AGE of OTTOMAN REFORM.” Past & Present, no. 208: 159–89. https://doi. org/10.2307/40783316.

BBC. 2009. “BBC - Religions - Islam: Ottoman Empire (1301-1922).” Bbc.co.uk. BBC. September 4, 2009. https://www.bbc.co.uk/ religion/religions/islam/history/ottomanempire_1.shtml.

Britannica. 2019. “Ottoman Empire - Military Organization | Britannica.” In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica. com/place/Ottoman-Empire/Military-organization.

Brummett, Palmira. 1993. “The Overrated Adversary: Rhodes and Ottoman Naval Power.” The Historical Journal 36 (3): 517–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/2639777.

Bulut, Mehmet. 2009. “Reconsideration of Economic Views of a Classical Empire and a NationState during the Mercantilist Ages.” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 68 (3): 791–828. https://doi.org/10.2307/27739796.

Bunting, Tony. 2024. “Siege of Rhodes | Summary.” Encyclopedia Britannica. December 2, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/ Siege-of-Rhodes.

Cay, Jimmy. 2022. “Ottoman Empire History.” Turkey Travel Planner. July 11, 2022. https://turkeytravelplanner.com/details/ History/Ottomans.html.

Eliza. 2023. “TutorChase: How Did Suleiman the Magnificent Expand the Ottoman Empire’s Territory?” Tutorchase.com. 2023. https://www.tutorchase.com/answers/ib/history/how-did-suleimanthe-magnificent-expand-the-ottoman-empire-s-territory.

Extra, History. 2016. “Https://Www.youtube.com/ Watch?V=JGZSkLq3Eng.” Www.youtube.com. March 12, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGZSkLq3Eng.

History, Daily. 2025. “How Did the Ottoman Empire Become the Third Great Islamic Caliphate - DailyHistory.org.” Dailyhistory. org. 2025. https://www.dailyhistory.org/How_Did_the_Ottoman_ Empire_Become_the_Third_Great_Islamic_Caliphate.

Jungudo, Maryam. 2024. “On the History of the Ottoman Empire: A New Perspective.” Researchgate. August 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/ Maryam-Jungudo-2/publication/382831242_On_the_ History_of_the_Ottoman_Empire_A_New_Perspective_A_ New_Perspective/links/66ae24c151aa0775f265bf31/ On-the-History-of-the-Ottoman-Empire-A-New-PerspectiveA-New-Perspective.pdf?__cf_chl_tk=HnyrglOn0Ua4vWAp 1qelbX66vn7Ly00SlCae1fJHpS8-1747085931-1.0.1.1-MN. cxvAncNY2dNJvX9it1pjfM4kxd9WTrdlq9Gc5ntw#page=122.

Labib, Subhi. 1979. “The Era of Suleyman the Magnificent: Crisis of Orientation.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 10 (4): 435–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/162212.

Mackey, Damien F. 2016. “King Solomon and Suleiman.” Parallel Lives, Also BC Afterglows in AD. May 9, 2016. https:// parallellivesbcad.wordpress.com/2016/05/09/king-solomon-andsuleiman/.

Maddie. 2024. “18.4.3 Suleiman the Magnificent.” TutorChase. TutorChase. June 17, 2024. https://www.tutorchase.com/notes/ib/ history/18-4-3-suleiman-the-magnificent.

Malcolm Edward Yapp, and Stanford Jay Shaw. 2018. “Ottoman Empire | Facts, History, & Map.” In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Ottoman-Empire.

Mardin, Serif. 1969. “Power, Civil Society and Culture in the Ottoman Empire.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 11 (3): 258–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/178085.

Marko Popović. 2019. “Siege of Belgrade in 1521 and Restoration of Fortifications after Conquest, In: Belgrade 15211867.” Academia.edu. May 17, 2019. https://www.academia. edu/39167166/Siege_of_Belgrade_in_1521_and_Restoration_of_ Fortifications_after_Conquest_in_Belgrade_1521_1867.

Moncure, Billy. 2019. “The Bloody Siege of Rhodes: The Ottomans & Their Unstoppable Empire.” WAR HISTORY ONLINE. March 27, 2019. https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/siege-ofrhodes-the-ottomans.html.

Özkan, Selim Hilmi. 2021. “THE CAPITAL of the OTTOMAN EMPIRE in EUROPE: BELGRADE on the FRONTIER (SERHAD) CITY (1521-1789).” SelcukTurkiyat. December 2021. https://dergipark. org.tr/tr/download/article-file/2171873.

Palmer, Alan. 2011. The Decline and Fall of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Fall River Press.

Parry, V.J. 2019. “Suleyman the Magnificent | Biography, Facts, & Accomplishments.” In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www. britannica.com/biography/Suleyman-the-Magnificent.

Rüzgar, Nilüfer. 2019. “LEADERSHIP TRAITS of SULEIMAN the MAGNIFICENT, in TERMS of ‘GREAT MAN’ THEORY,.” Osmanli Mirasi Arastirmalari Dergisi 6 (15): 317–27. https://doi. org/10.17822/omad.2019.128.

Şahin, Kaya. 2023. “Suleiman the Magnificent.” World History Encyclopedia. February 27, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/ Suleiman_the_Magnificent/. “Science and Religion in the Early Middle Ages.” 2009. The Renaissance Mathematicus. The Renaissance Mathematicus. June 29, 2009. https://thonyc.wordpress.com/2009/06/29/science-andreligion-in-the-early-middle-ages/.

Spaulding, William. 2023. “Protestant vs. Catholic | History, Beliefs & Differences | Study.com.” Study.com. 2023. https://study.com/ academy/lesson/protestant-vs-catholic-history-beliefs-differences. html.

Stewart, Angus. 1988. “SÜLEYMAN the MAGNIFICENT.” RSA Journal 136 (5382): 438–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/41374586.

Welsh, William E. 2022. “Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I.” Warfare History Network. May 2022. https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/ article/ottoman-sultan-suleiman-i/.

Wigen, Einar. 2013. “Ottoman Concepts of Empire.” Contributions to the History of Concepts 8 (1): 44–66. https://doi. org/10.2307/43610931.

By Yeva

Introduction

A great empire is a large and powerful state that controls vast territories and diverse populations, exercising political, military, economic and cultural influence. Its stability and power depend on military and administrative strength, but also on internal cohesion and public support. Without these, its control is fragile and its status as a great empire more symbolic than secure.

Background: Peter I’s objectives and setting up the Empire The Tsar was primarily motivated by the role that international trade played in strengthening the state’s international power, and he sought to replace foreign intermediaries with Russian ones in trade relations with Europe.1 At the beginning of the 18th century, Russia had no access to the Baltic Sea; the only major port in Russia was at Arkhangelsk but bad climate and geography made it difficult to develop trade and political contacts with the rest of Europe. In 1697–1698, Peter went on a tour of Europe visiting the Netherlands and England, among other places. While there, he learnt to sail and built up his ‘play’ guards regiments under the command of foreign officers. Peter returned from this trip not only determined to enact deep reforms in Russia but also with a plan to build a Northern Alliance against Sweden, at that time the dominant country in the region.1 While on his grand tour, Peter took with him about 750 professionals, including craftsmen and military professionals.2

Every day of the Tsar’s stay in England was fully occupied in seeing something new, something practical, which could be put to good use in Russia later on. His chief purpose of staying in England was to study English shipbuilding. Peter’s mission was not just about observing but actively engaging with Western practices in areas that were crucial for Russia’s

1 Lucjan Ryszard Lewitter, “Russia, Poland and the Baltic, 1697–1721,” The Histori‑cal Journal 11/1 (March 1968): 3–34

2 Russian Expansion in the Baltic in the 18th Century|Studia Historica Gedanensia 2024 12 30 | Journal article by Arkadiusz Janicki (p 94)

future in order to make it a European power.

Peter 1 also began to explore the possibilities of a territorial war against Sweden. In 1699 Peter formed an anti-Swedish alliance with SaxonyPoland in the village of Preobrazhenskoe. This alliance soon expanded to include Denmark-Norway, forming the Northern League, its purpose was to coordinate a war against Sweden and divide Baltic territories.3

Great Northern War and reforms: Despite Peter’s long-term goals in Sweden, he didn’t strike first. Denmark and Saxony-Poland invaded Swedish Livonia in early 1700. When Charles XII realised he was surrounded by enemies, he chose to attack Copenhagen and promptly forced Denmark to withdraw from the war and then turn to fight Peter I.4 Russia was defeated by the Swedish Army at the Battle of Narva in November 1700. The easy Swedish victory caused

3 Russian Expansion in the Baltic in the 18th Century|Studia Historica Gedanensia 2024 12 30 | Journal article by Arkadiusz Janicki (p 93)

4 Ragnhild Marie Hatton, Charles XII of Sweden (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968).

Charles XII to miss the opportunity of eliminating Russia from the war, and the Swedish king chose to shift his focus to Poland. This decision gave Peter I valuable time to reorganise the Russian army and to modernise his country. He set himself the goal of transforming Russia into a great European power.

Peter I implemented a modernisation of the army, the construction of factories and military academies, the introduction of Western-style dress and customs, the creation of a new taxation system and the founding of St. Petersburg as a European-style capital.

Russian historian Solovyov calls Peter’s reforms a ‘revolution’, emphasising their turning point: Russia was transformed from a backward power into a strong and modernised country. As a part of the regional reform, the entire state structure was changed. The whole country was now divided into provinces called gubernii. Peter organised a number of special ‘colleges’ from which in the 19th century the Russian ministries were to spring. Sergius Yakobson writes: “The statesmanship employed by Peter in all these matters is astonishing; the features of the administrative structure of the Russian empire set up by him and his

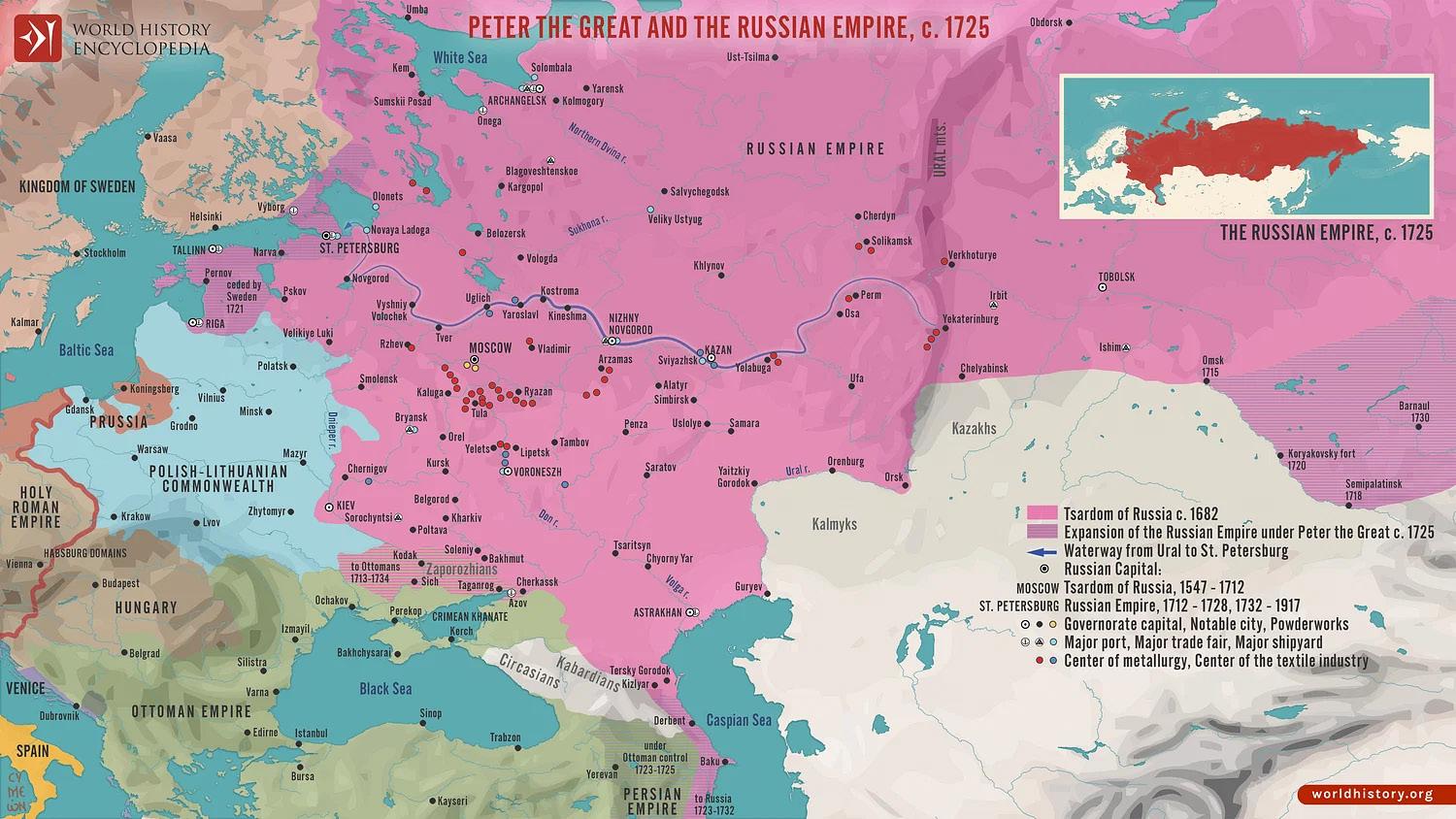

This map illustrates the expansion and consolidation of the Russian Empire around 1725, during the transformative reign of Peter the Great

collaborators remained nearly intact until the beginning of the twentieth century.”5

Wars and the maintenance of a permanent recruit army required huge funds, which were collected through financial reforms. In 1704, Peter conducted a ‘household’ census, which showed a decrease in the number of households (in order to avoid taxes, several households were surrounded by one fence). In 1718-1724, a second census was conducted and, based on the data obtained, the government divided the amount of money needed to maintain the army and navy by the population. Russian historian Oleg Matveyev, in The Great Russian Encyclopedia’, writes of the following successful military reforms: “Russia became a maritime power with a regular navy”, new-style regiments appeared (infantry, dragoon, hussar, Cossack), a regular army was created, military schools were opened and new central military administration bodies were formed. Soloviev adds that: “Peter the Great, this gigantic reformer, not only armed Russia in a new way, but also infused it with the European spirit.” stated in “Public Readings on Peter the Great”, Lecture 2-3.

A part of Peter’s vision sprang from his painful awareness of the low opinion in which Russia was held abroad. This is evident from the foreign extracts where it is stated that: ‘The Muscovites are barbarians. They are suspicious and mistrustful, cruel, sodomites, gluttons, misers, beggars and cowards, and all slaves except for members of three foreign families.’ (from a book published in French in 1698 by a mysterious diplomat called Foy de la Neuville).6 As a result Peter changed the start of the year from September 1 (Byzantine system) to 1 January and adopted the Julian calendar, aligning Russia’s timekeeping with Europe he also banned traditional 5 https://www.historytoday.com/archive/peter great Russian hero

Russian clothing and ordered the nobility to wear Western-style coats, as well as imposing a beard tax in 1705 aimed at breaking traditional Russian customs.

In the words of Archbishop Feofan Prokopovich, this was a landmark in the creation of the Petrine myth; Peter had ‘given birth’ to Russia. He was Samson (strong defender of the fatherland), Japhet (creator of the fleet), Moses (lawgiver), Solomon (bringer of reason and wisdom) and David and Constantine (reformers of the Church).6

In 1702, the Russian army won a major victory over Wolmar von Schlippenbach, who was a baltic German noble near Hummelshoj , then in the same year the Russians took Nöteborg located at the mouth of the Neva River, which gave the Russians considerable freedom of action in the Baltic region and provided security for the soon-to-be founded St Petersburg. In 1703, the Russian army had already ravaged most of Livonia. One of Peter’s key colonial efforts was the founding of Saint Petersburg in 1703 on conquered Swedish land. Peter I’s decision to build a new capital for his state not only made it easier for the ruler to introduce thorough reforms in the country, but also permanently tied the interests of Russian politics to Western Europe. St Petersburg was a “window on Europe,” and its wide access to the Baltic Sea allowed Russia to influence the fate of all of Europe. Its founding symbolised Russia’s integration into the European political and economic system. Peter not only secured access to sea routes and European markets but also positioned Russia as a diplomatic power.

In 1705, the Russian army entered Courland, which had great strategic importance, as it cut off the Swedish troops stationed in Livonia from the main forces of Charles XII operating

6 https://www.historytoday.com/archive/peter

on the territory of the Commonwealth.7 Sweden lost the Battle of Poltava in 1709, which allowed a successful assault on Swedish Baltic strongholds in 1710 8 when Peter I ordered Russian troops stationed in Livonia to attack Riga. In 1710, after six months of artillery siege and in a situation of famine and pestilence in the city, the people of Riga surrendered the city. The Russian victory over the Swedes was confirmed by the Peace of Nystad of 1721, ending the Northern War and joining Livonia, Estonia, Ingria and Karelia to Russia.

Before the war, Russia’s army was poorly trained, under-equipped, and fragmented, and its navy was practically non-existent. Peter’s reforms addressed these weaknesses on multiple levels. Reforms made it possible for the state to expand, defend its borders and project influence-key marks of a “great empire”.

However, Peter I saw war with Sweden as more than just a way to gain strategically-important borders and opportunities for lucrative international trade. For the Tsar, defeating Sweden meant that Russia could develop and become a European power. So having defeated such a powerful rival, on 2 November 1721, Europe was obliged to recognise her as a great European power. After the victory over the Swedes, Peter took the title of Russian Emperor. At this stage, the Russian Empire had been created geopolitically, marking Peter’s successful territorial expansion. However, an empire is not defined by geopolitical success alone – it also encompasses economic, social and cultural aspects, and in these areas, Peter’s achievements are far more questionable.

His supporters argue that Peter built a new professional army, he westernised Russian society, established new industries, factories and improved taxation. Voltaire wrote that: in 50 years Russia has gone the way that other countries have gone through in 500 years.9 But others claimed that the Russian people did not want to change and all of this was imposed by force. Peter the Great aimed to root out ‘alien’ elements in both society and religion. With the rapid absorption of new territory, Russia was becoming a multinational empire and, as such, was losing whatever ethnic, religious and cultural homogeneity it had formerly

7 Russian Expansion in the Baltic in the 18th Century|Studia Historica Gedanensia 2024 12 30 | Journal article by Arkadiusz Janicki (p 93)

8 https://www.dailykos.com/ stories/2023/1/25/2149165/ The Great Wrath

9 Russian Expansion in the Baltic in the 18th Century|Studia Historica Gedanensia 2024 12 30 | Journal article by Arkadiusz Janicki (p 93)

possessed, as Avrich Paul suggested.10 Therefore Peter’s main priority was to improve Russia’s image abroad, so the fate of the Russian people mattered little to him. One example is the famous construction of St Petersburg, which in reality was built with ‘tears and corpses’, according to Russian historian Nikolai Karamzint. Peter used St Petersburg to construct a microcosm of his New Russia, untainted by the past, in which western Europeans (rather than Russians) would feel at home. Peter was indeed obsessed by the problem of Russia’s ‘backwardness’ and he summed up the problem, for example, in an order of 1721 to replace old-fashioned sickles with scythes: ‘Even though something is good and necessary, if it is new our people will not do it unless they are forced to...’ - or in a manifesto on the encouragement of industry (1723): ‘Our people are like children who, out of ignorance, will never get down to learning their alphabet unless the master forces them to do so.’11 Evgeny Anisimov, Russia’s leading expert on the Petrine era, described Peter I as ‘the creator of the administrative-command system and the true ancestor of Stalin’.12 Peter preserved the autocratic style of governance and concentrated all the plenitude of power in his hands, resulting in the creation of the police state, implementing not only reforms that benefited and modernised Russia but also oppressive policies that curtailed individual freedoms. He implemented tax reform which tripled the existing tax rate, which placed a heavy burden on peasants and lower classes. For those who refused to pay he introduced severe penalties including imprisonment or execution. Peasants were increasingly liable to labour services (canals, harbours, ships and St Petersburg had to be built). Peter’s treatment of the church proves his imperative to deploy all resources for the state. He abolished the patriarchate and slimmed down the priesthood in 1721, thereby removing a potentially dangerous rallying point for opposition.13 Preobrazhensky Prikaz was an institution used by Peter to suppress any form of dissent.

People could be persecuted for even minor criticisms of the emperor or the government, including intellectuals, writers and ordinary people. The repression helped maintain Peter’s

10 Russian rebels 1600 1800 by Avrich paul (p 144)

11 Manifesto on the encouragement of industry (1723) issued by Peter The Great

12 The Reforms of Peter the Great: Progress Through Coercion in Russia by Anisimov

13 Peter the Great A Hero of our Time? | History Today

absolute control and create a police state. Moreover, as Anisimov states, the reforms were aimed primarily at collecting funds for waging war and the collections were carried out by force and often did not lead to the desired result. The country’s economic capabilities could hardly match such ambitions.

It is clear that Peter was successful in the geopolitical sphere due to the major territorial expansion during the Great Northern War and his establishment of St Petersburg.

As well as the introduction of tax and army reforms, new industries and factories boosted Russia’s image, transforming it into a European power. Peter created the impression of a state rapidly catching up with, and even competing against, Western European powers. However, it was destructive for the common people; economic gain for the state came at the cost of worsening conditions for the lower classes. Society was deeply divided and the police state intensified repression. Peter was successful in promoting western ideas but he destroyed centuries of Russian tradition. Overall, all of his reforms were imposed by force, alienating many Russians, outlining a failure to create a genuinely unified society. The fractures meant that Peter failed to secure a truly ‘great’ empire in the sense of domestic stability. As there was a risk of internal dissent, rebellion and stagnation, Peter’s success is remarkable on the surface but with unresolved tensions that undermined the cohesion of his empire.

In Russia this war is called the Northern War, but in Finland it is also known by a different name, the ‘Great Hard Times’, which emphasises the long period of occupation of Finland by Russian troops, which lasted from 1710 to 1721. 'The period of Great Wrath 171321 is still the cruellest time in Finnish history – pure brutality for brutality’s sake without rules or laws. Today, we would call it genocide. It was systematic, intentional and total.'14 In 1716, Peter

I ordered all the children and youth be captured and adults to be killed in Ostrobothnia, the west coast of Finland. The land was to be destroyed to make a 60-mile buffer zone of wasteland. 'Homes, farms, fields and towns were invaded, looted and torched. Bodies everywhere. Rape, terror, torture, mass slaughter. Slavery.'15 Lindequist argues that Russian occupation had brought poverty among the Finnish people: ‘One cannot really come to any other conclusion than that the economic situation in Finland was poor right from the very first year of the war, and became progressively worse year by year thereafter.'16 In total at least 5,000 Finns were killed, 10,000 taken as slaves, 30,000 children and women were enslaved. 17 18 Evidence to the opposition are individuals like Tapani Lefvling, who was a Finnish partisan leader during the Great War. He left a diary for posterity in which he recounts his thrilling adventures. Kosti Vilkuna wrote the novel ‘The Adventures of Tapani Lefvling based on the events described in the diary. The novel describes how Lefvling distinguished himself in fighting against the Russian occupation. He was captured by Russians in Suorlahti but managed to escape in 1710 and later he and around 20 other men destroyed a much larger Russian army and captured 60 horses as military spoils.19 Russia invaded and stories/2023/1/25/2149165/ The Great Wrath

15 https://www.dailykos.com/ stories/2023/1/25/2149165/ The Great Wrath

16 K. O. Lindeqvist, Isamilan aila Suomessa (Porvoo, 1919), PP. 167, 175, 189

17 Zetterberg, Seppo, ed. (1990). Suomen historian pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish). Helsinki: WSOY. ISBN 978 951 0 14253 0

18 Kurki Suonio, Ossi (23 October 2015).

“Historioitsija: Synkkyyden Suomi kärsi orjuudesta jopa enemmän kuin mikään Afrikan maa”. Uusi Suomi (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

19 https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/

occupied large areas of Finland from 1710–1721, establishing long-term control and enforcing Peter’s goal of creating a western buffer zone, thus proving geopolitical success. The occupation of Finland not only secured Russia’s western frontiers but also allowed Peter to project power deep into the Baltic. However, this was followed by economic failure and destruction of infrastructure. Tens of thousands were forcibly taken to Russia, creating a demographic collapse in the Finnish regions. Finnish cultural identity was suppressed, which created deep-seated Russophobia, weakening long-term integration and marking a widespread dissatisfaction with Peter’s policies. While he achieved remarkable territorial gains, his methods alienated the local populations. Peter’s rule left a legacy of repression, cultural fracture, and rebellion. His empire remained divided.

Treatment of the Bashkir Bashkir, a member of the Turkic people, numbering more than 1,070,000 in the late 20th century, settled in the eastern part of European Russia, between the Volga river and the Ural mountains, and beyond the Urals.20 Russia appealed to the Bashkirs voluntarily to join the state and they agreed in 1557 with the guarantees of a full right to use their land, have their own administration and religion. But Peter the Great began to violate the agreements. Due to his active policy of colonisation, the 18th century became the era of the largest popular movements and uprisings in Bashkiria; and Peter the Great’s reforms changed

Tapani_L%C3%B6fving#cite_note lop 5

Tapani Löfvingin seikkailut Kyösti Wilkuna

the course of history in Bashkiria.21 Alexandre Bennigsen erroneously argues that Bashkirs were subjected to genocide by the Russians as they were confident enough to reject any compromise.22 The number of Bashkirs who were exiled, killed, executed or died of hunger and exposure was about 60,000, nearly onefifth of the all Bashkirs.23 Peter began the exploitation of Bashkiria’s natural resources and built the first large factory in 1701.

The 1700s were a time of transition from an extractive empire to an exploitative one; the term exploitative in the sense that the central authority attempts to draw as much income from a region as possible in the context of its human and natural resources by bringing the idle lands of Bashkiria into active use for farming, mining, and other purposes, as well as the requirement of greater control by the Russian government, which resulted in persecution of Bashkirs.24 25 The Russian government and intellectuals no longer viewed them as equals with the Russians and were seen now as subhuman. Even though at that time Peter was determined to make Russia a great power and a modern country, Bashkiria was not in the list of his priorities, as 70 new types of taxes were

21 “Bashkirs between Two Worlds, 1552 1824” by Mehmet Tepeyurt

22 Alexandre Bennigsen and Marie Broxup, The Islamic Threat to the Soviet State (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 24

23 R. G. Khuzeev, Istoricheskaia Etnografiia Bashkirskogo Naroda (Ufa: Bashkirskoe Knizhnoe Izdatelstvo, 1978), 154

24 “Bashkirs between Two Worlds, 1552 1824” by Mehmet Tepeyurt

25 “Bashkirs between Two Worlds, 1552 1824” by Mehmet Tepeyurt

imposed on Bashkirs, including taxes on baths, bees, horse collars, storage rooms, masjids and masjid attendees. Peter also started to undermine Bashir’s culture by forbidding the use of the Tatar and Bashkir languages in administrative documents and lawsuits – everything was translated into Russian. Russian military units destroyed mosques, confiscated Islamic books and prohibited the construction of new religious buildings, as well as many Bashkir families were forcibly enrolled in Orthodox parishes. The reaction was a direct attack against anything Christian, which was seen as an expression of state repression. For example, in Kazan and Ufa, rebellious Bashkirs burned down 75 churches in 1709.26

Bashkiria became critical suppliers for Peter’s expanding military machine, providing the raw materials. Peter turned the region into a productive part of the empire through mining and building factories. Factory towns established under Peter’s rule laid the groundwork for future industrial centers in the Urals. The extraction of natural wealth from Bashkiria allowed the state to finance military campaigns;tighter administrative control allowed Russia to mobilise resources from Bashkiria efficiently, integrating the region into the imperial economic system. While reforms towards Bashkirs were geo politically and economically successful for Russia, they were harshly exploitative and devastating towards the Bashkirs. This led to the Bashkir rebellion (1704-1711), which reflected a broader social divide and dissatisfaction with Russian governance, marking a failure to integrate diverse people. Peter’s treatment of Bashkiria exposed the contradiction: although he expanded and enriched the empire, he did that at a huge cost of deepening internal divisions, fostering cycles of rebellion and repression.

Bulavin’s rebellion

Peter the Great’s reforms aimed to westernise Russian society. However, the consequences of these reforms highlight the deep social fractures they produced. For example, the Bulavin uprising became the most significant act of opposition to Petrine policies.

For decades, the Cossacks had enjoyed a semi-autonomous status under Russian suzerainty, with their own army and administration. But under Peter I, Russian centralisation accelerated. They argued that his reforms created two distinct cultures that were facing each other across a widening gulf of dress, habit, language, and religion. Cossacks were being reduced to a disgruntled element opposed to innovation and to

26 Galina M. Yemelianova, Russia and Islam: A Historical Survey, (New York: Palgrave, 2002), 42

the whole emerging order.27 They faced outright extinction, unrest and the abuse from gentry commanders. Their morale was low, their discipline lax, their deepseated xenophobia excited by the largescale introduction of foreign officers.28

Peter’s vast military programme demanded a more reliable and efficient infantry. Peter, in the popular mind, became an evil impostor, a false Tsar, a creature possessed by the Devil.29 Peter I led the military expedition that initially captured about 3,000 fugitive serfs. In response to the Russian military infiltration, Cossack chief Kondratiy Bulavin formed a rebel army to repel the Russian forces. However, the rebellion lacked unified leadership and Bulavin was killed in 1708. Peter’s response to the uprising was fast and effective. Through military force and administrative organisation, he suppressed the rebellion. The Russian state subsequently imposed tighter control over the Cossack regions, implementing imperial authority and integrating them more fully into the empire’s military structure. However, Peter I could not abolish Cossack customs; future popular uprisings continued to erupt against Russian rule, showing the persistent challenge of integrating diverse communities into an imperial framework.

Conclusion

Peter I reshaped Russia’s geopolitical footprint by breaking Swedish

27 Russian rebels 1600 1800 by Avrich paul (p 136)

28 Russian rebels 1600 1800 by Avrich paul (p 139)

29 Russian rebels 1600 1800 by Avrich paul (p 141)

"Bashkirs between Two Worlds, 15521824" by Mehmet Tepeyurt

R. G. Khuzeev, Istoricheskaia Etnografiia Bashkirskogo Naroda (Ufa: Bashkirskoe Knizhnoe Izdatelstvo, 1978)

Galina M. Yemelianova, Russia and Islam: A Historical Survey, (New York: Palgrave, 2002)

Russian rebels 1600-1800 by Avrich Paul

“The Bulavin uprising: the last stand of the old steppe (1706–1709)” by Brian J. Boeck (Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 January 2010) (International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, ed. Immanuel Ness, Blackwell Publishing, 2009, p. 536)

The Breakdown of a Society: Finland in the

dominance and gaining strategic access to the Baltic Sea through the Great Northern War and especially due to his military skills. Founding of St Peterborough secured a ‘window to Europe; involving Russia in international trade and diplomacy. He modernised the army and navy by introducing conscription, establishing military schools and importing foreign experts, turning Russia into a formidable sea force.

Peter also centralised Russia’s administrative operation by reorganising the central government into colleges; he introduced taxation, which increased the control over both elites and peasantry and inserted Russia firmly into European power politics. By the end of his reign, Russia was undeniably a major player in Europe. However, this came at an enormous human, social and cultural cost. As Evgeny Anisimov stated, Peter was ‘the true ancestor of Stalin’ – not a reformer but a ruthless architect of Russia.

While the outcomes of the reforms were successful for the state as they supported military goals, they were morally questionable. His methods relied on terror and repression; modernisation policies were enforced on Russians. The construction of St Petersburg was carried out using forced labour, and thousands of peasants died. Resistance was met with punishment or execution. When the Bashkirs rebelled between 1704 and 1711 against rising taxes, Peter responded with savage military campaigns that destroyed villages and killed thousands of Bashkirs. His reforms clearly benefited the narrow elite, particularly the nobility and as a consequence divided society. Policies were driven by autocracy, coercion

Great Northern War 1700-1714 by Antti Kujala

Russian Expansion in the Baltic in the 18th Century|Studia Historica Gedanensia 202412-30 | Journal article by Arkadiusz Janicki

Alexandre Bennigsen and Marie Broxup, The Islamic Threat to the Soviet State (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1983)

Lucjan Ryszard Lewitter, “Russia, Poland and the Baltic, 1697–1721,” The Historical Journal 11/1 (March 1968)

The Story of Ukraine by Clarence Manning

“The Bulavin uprising: the last stand of the old steppe (1706–1709)” by Brian J. Boeck (Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 January 2010)(International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, ed.

and a disregard for the well-being of ordinary Russians. For example, western education introduced by reforms was largely limited to the sons of the elite. To secure the loyalty of the nobility, Peter allowed them greater control over their estates, while the peasantry was exploited. New administrative posts were filled by members of the nobility or by foreigners brought into service, while ordinary peasants had no access to these opportunities. Moreover, indigenous peoples were called ‘sub-humans; they faced repression, destruction and Russification.

Social mobility remained limited and reforms widened the gap between a Westernised elite and impoverished masses, increasing oppression for the peasantry. Finally, the country’s economic capabilities could hardly match Peter’s economic ambitions, which slowed down the country’s development and created a groundwork for future crises. He opened the door to a period of instability known as the ‘Era of Palace Coups’ (1725-1762), marked by frequent plots, elite factionalism and the violent overthrow of monarchs. Although Peter raised Russia to the rank of a European power, the Russian Empire still does not match the most successful empires of the time. Compared to Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire it was territorially vast but economically underdeveloped, socially divided and regionally confined. Peter was a successful state builder, but not a successful human leader. While others could argue this was enough to make Russia a great power, it is clear that without the support of the population, an empire is unstable. Discontent among the masses seeds unrest, resistance and long-term fragility. n

Immanuel Ness, Blackwell Publishing, 2009, p. 536)

“The Bulavin uprising: the last stand of the old steppe (1706–1709)” by Brian J. Boeck (Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 January 2010)(International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, ed. Immanuel Ness, Blackwell Publishing, 2009, p. 536)

https://www.britannica.com/biography/ Peter-the-Great/The-tsarevich-Alexis-andCatherine-to-1718

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/ peter-great-Russian-hero

https://www.dailykos.com/ stories/2023/1/25/2149165/-The-GreatWrath

By Aurora

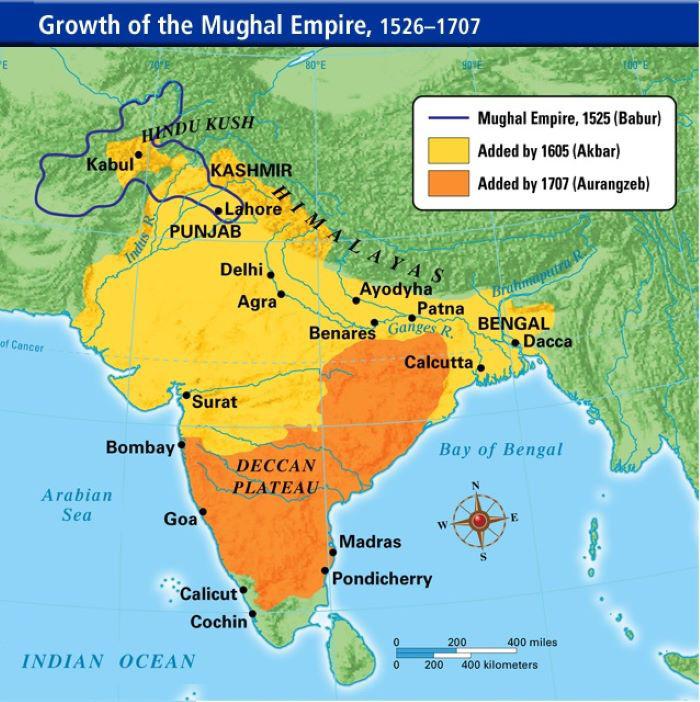

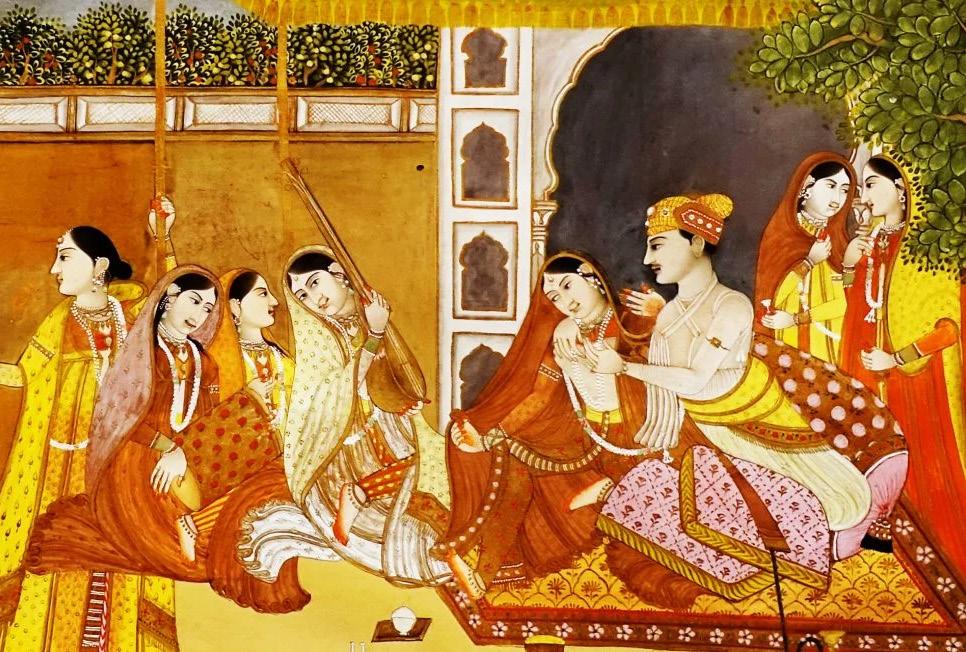

The Empress of an exceedingly wealthy and internationally powerful Empire lasting from 1526 to 1857 that expanded over the South Asian subcontinent and encompassed around 150 million people at its peak, naturally demands attention. However, the reasoning behind Nur Jahan’s prominence in folklore, historical accounts and wider debate of the Mughal Empire is largely ambiguous and incites complex questions around legend, power and gender.

The Mughal Empire began in 1526, after Muslim warriors from modern Iran and Turkey invaded northern modern India. It was founded by Babur, a descendant of both Timur of the Timurid Empire, and Genghis Khan of the Mongol Empire; Mughal is the Persian word for Mongol. Different cultures and religions were absorbed into the Mughal domain and the Mughals began the mobilising of the subcontinent’s population and utilisation of its land resources more effectively than prior rulers, with aims of power, wealth and expansion.This Empire became one that prospered greatly in trade, fostering the economy through a booming textiles industry and as a hub for the international trading of spices. As well as developing a thriving inland trading system, the Mughals established a dominant position in trade across Asia and in maritime trade, which formed connections to the West, although their lack of a strong navy did make them somewhat vulnerable to European maritime powers and their colonial ambitions. Literature, architecture and representational arts also flourished under the patronage of the Mughal Emperors, encouraged by the era’s cross-cultural integration. Remaining one of the most recognised elements of the period, Mughal culture developed through language, ideology and politics.1 However, the 200 years of Mughal dominance were by no means centuries of stability.There were reigns of

1 Howarth, W. (n.d.). READ: Mughal Empire (article). [online] Khan Academy. Available at: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ whp origins/era 6 the long nineteenth century 1750 ce to 1914 ce/x23c41635548726c4:other materials origins era 6/a/read mughal empire.

oppression, exiled emperors, wars, and rebellions and revolts led by people both in and outside the Mughal court.2 The Mughal Empire is seen by many to have ended when it broke down into a loose union of states around the early 18th century, due to growing instability and challenging of the central government from internal divisions and rival groups, as well as increased involvement from European merchants and governments, seeking the Empire’s wealth. Officially, however, the Mughal dynasty lasted until 1858 when the Indian Rebellion led to the British Government of India Act, abolishing the East India Company and making India a British colony, which marked the end of the Mughal Empire.

2 Riley, M., Ford, A., Goudie, K., Kennett, R. and Snelson, H. (2020). Understanding history : Britain in the wider world, Roman times present. London: Hodder Education.

Who was Nur Jahan?

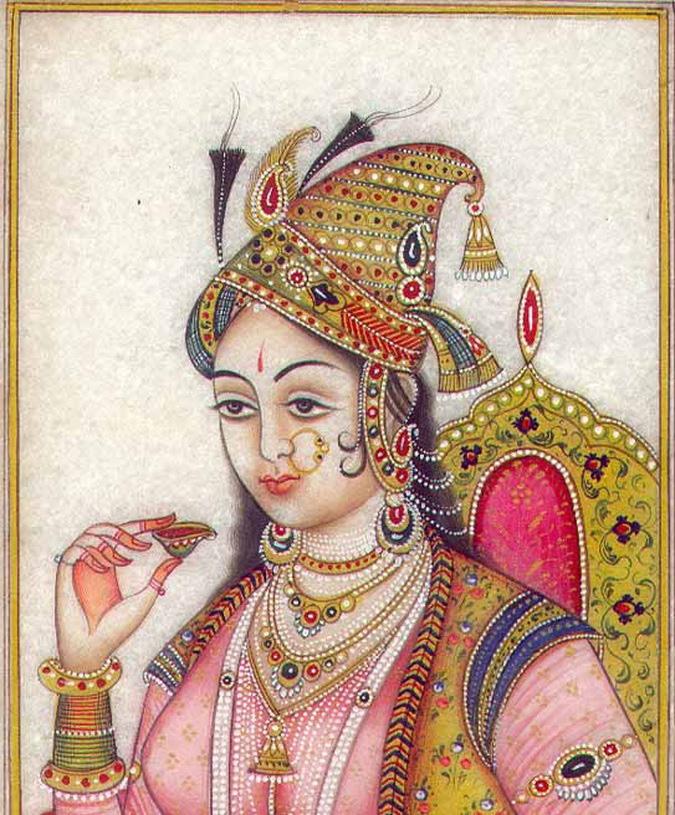

Nur Jahan stands among the key characters of the history of the Mughal Empire. Born in 1577, in present-day Afghanistan, into a family of aristocrats, she was the daughter of an important administrator of the court and named Mihr un-Nisa (meaning beautiful and faithful woman). Her parents had moved from Iran, where intolerance under the Safavid dynasty was rising, seeking refuge in the more liberal Mughal empire and hoping to find good fortune in the court. In 1594, she married her first husband, a military officer and later government official. He was a controversial man and, after being accused of plotting against the ruling Mughal Emperor Jahangir, was killed in a battle against the governor’s men in 1607. Now a widow, Mihr un-Nissa and her daughter were given shelter

in the Emperor’s harem, in which she rose in influence and eventually came to Jahangir’s attention, becoming his 20th and final wife in 1611. Jahangir renamed her Nur Jahan, meaning light of the world.

Attracting the interest of historians (such as Ruby Lal3, Ellison Banks Findly4 and Abraham Eraly5) and living on in the folklore of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, Nur Jahan is remembered and admired for her story. The controversy sparked by her personality and boldness, as well as her impact on culture through the arts and architecture, alongside her social and political influence through her position in court as the co-sovereign of a vast empire, and, perhaps most significantly, the fact that she was a woman, have brought her story into the spotlight. Much debate follows this narrative. One could argue that this is ultimately because she veers from the expectations held by contemporaries and historians both from the European and the Asian perspective, in that she was a woman, not of royal birth, who became a wife of a powerful man and subsequently the most powerful woman in a largely traditional, patriarchal empire. From the perspective of modern feminism, (as acknowledged by historians such as Ruby Lal and Rani Safavi)6 it could be argued that her legacy in history as a woman who rose to power and status equivalent to that of an Emperor makes debate over her character, her intentions and her impact inevitable. Alternatively, one could claim it is purely her achievements, or failings, as a ruler and her social and political impact that pull her into discussion. Another element to consider is whether her life has been romanticised through this lens of storytelling and folklore and the impact this could have on our ability to evaluate her significance. Legend has potentially clouded over the reality of her life and influence and emphasised her position in Mughal history beyond her genuine impact. Overall, I would argue that the underlying reason for the significance of Nur Jahan is the unfamiliarity of a life like hers. She stands against expectations due to her gender and position, and this atypicality of her behaviour and status becomes a basis which makes her legacy more impactful. In other words, she is significant in history because she was unusual, which makes her actions more interesting and more impressive.

3 Lal, R. (2018). Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan. W. W. Norton & Company.

4 Ellison Banks Findly (1993). Nur Jahan. Oxford University Press.

5 Eraly, A. (2000). Emperors of the peacock throne : the saga of the great Mughals. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Nur Jahan: The Empress7 Nur Jahan demands acknowledgment partially due to the fact that she was, in effect, an Empress. Her influence after marrying Jahangir was extensive and strong and she is often referred to as the “ruler in all but name”. Jahangir, meaning conqueror of the world, also previously known as Prince Salim, was addicted to opium and alcohol, and he gradually became sick and unable to govern. After marrying Nur Jahan when he was 41, his ability to rule continued to deteriorate, so he relied on her to make administrative decisions and to govern. Many also attribute this delegation of power to his devotion to her; indeed, the love between the two is quite literally the stuff of legends.6 She proved to be very well suited to this role, according to Historian Maya M Tola, her skill went beyond the abilities of her husband.8 She was driven, educated, charismatic, intelligent and had an aristocratic upbringing that aided her in court. Evidence of this and her success in prevailing as the ruler of the Mughal Empire can be seen in the fact that she was acknowledged by many as a co-sovereign - contemporaries like Captain William Hawkins (an East

6 Past Loves Podcast and Lal, R. (2020). The Nur Jahan and Jahangir Love Story. [online] Past Loves. Available at: https://pastlovespodcast. co.uk/2020/12/14/the nur jahan and jahangir love story/ [Accessed 18 May 2025].

India Company Representative) said that appeasing Nur Jahan was the key to win the favour of the emperor, and Shah Jahan, her step-son, writes in his memoir, about the fact that she was “extremely powerful”.8 In the words of historian Inayat Khan: “She acquired such unbounded influence over His Majesty’s mind that she seized the reins of government, and assuming to herself the supreme civil and financial administration of the realm ruled with absolute authority till the conclusion of his reign.”7 Nur Jahan was, to all extents and purposes, the head of state. She held court independently in Jahangir’s absences and she possessed the imperial seal, meaning that her consent was needed for legalising any order. She even had coins issued in her name, a clear example of her political standing. Thus, the simple fact of her power is a leading factor in her significance, placing her on a similar status to and making her of equal importance as the Emperors of this vast empire.

As all rulers of the Mughal Empire, Nur Jahan did have a substantial impact. Trade continued to develop under her reign and through this she built

7 Losty, J.P., Galloway, M., Ramphal, C. and Beibly, D. (n.d.). Women at the Mughal Court Perception & Reality. [online] Available at: https://francescagalloway.com/usr/documents/ exhibitions/list_of_works_url/48/women at the mughal court perception and reality.pdf.

The Mughal Empire was a powerful and influential empire in South Asia that existed from the early 1500s to the mid-1800s. Founded by Babur in 1526, it reached its zenith under the rule of Akbar, and ultimately declined and was replaced by British colonial rule

substantial wealth separate from the Mughal treasury. For example, Agra (the capital city) became an important commercial centre. She is said to have ordered the collection of taxes on goods from traders and merchants and encouraged lucrative trading relationships in Asia and Europe. She oversaw the construction of numerous rest houses, known as sarais, across the Mughal Empire to support travelling traders. Additionally, she owned ships in her own name, which transported goods to Europe and were also used by pilgrims. She is also remembered as a humanist, taking an interest in women’s affairs, providing land for women and opportunities for orphan girls by arranging dowries and marriages, or simply providing for them.8 Her cultural contributions were also of significance, she was a patron of the arts in literature, paintings and architecture, as was Jahangir. She took an interest in Mughal miniatures (an art form of

8 Safavi, R. (2018). Was Nur Jahan a scheming temptress or just an independent woman who historians couldn’t fathom? [online] DAWN. COM. Available at: https://www.dawn.com/ news/1393959/was nur jahan a scheming temptress or just an independent woman who historians couldnt fathom [Accessed 18 May 2025].

small but detailed illustrations)9, and is credited as the person to bring women into Mughal paintings as a central theme, a step towards greater popular recognition of women in a traditional patriarchal society. Satish Chandra, a historian specialising in Indian history, notes that “she completely dominated the harem and introduced many new designs of dresses”, referring to her work in creating popular women’s clothes.10 It is also worth mentioning that she owned a library. While this was not uncommon for royal Mughal women, within a society in which many women, especially in the lower classes, were illiterate and did not have access to reading or writing, this is significant. She also commissioned many impressive architectural projects including the garden Shahdara in Lahore, palaces and tombs including the one in which she and Jahangir were eventually buried, also known as the

9 Tola, M.M. (2020). Nur Jahan the Light of the World. [online] DailyArt Magazine. Available at: https://www.dailyartmagazine. com/nur jahan the light of the world/.

10 Yadav, P. (2021). Empowered, But to What Extent? : A Story of Nur Jahan. [online] DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY. Available at: https://lsrhistory.wordpress.com/2021/03/06/ empowered but to what extent a story of nur jahan/ [Accessed 18 May 2025].

inspiration for the Taj Mahal11. Alongside the context of the significance of art in Mughal culture, the focus of much Mughal wealth under the patronage of most of the Emperors, it is clear that Nur Jahan’s influence extended not only into politics and society but also the lasting legacy of the Mughals. Overall, the “almost Empress” Nur Jahan could be seen as having a claim to importance equal to that of the Mughal Emperors in our history books. Historian Ruby Lal highlights this perfectly, writing: “In act after act – hunting, advising, issuing imperial orders and coins, designing buildings – she ensured that her name was etched indelibly in public memory and in history”.12 Therefore, all of this influence and impact must be seen as a leading factor in Nur Jahan’s significance. However, without acknowledging the disadvantage of being not only a woman, but just one of 20 wives, the significance of Nur Jahan and, subsequently, her power and actions as co-sovereign would be completely misvalued. It could be said that although these actions are impressive and central to her significance, her legacy would not be able to extend to more than that of simply a co-sovereign without the atypicality of her character. This context is the crucial underlying reason, within all of her achievements, that she attracts and deserves so much attention as a figure in Mughal history. 13

Nur Jahan has gained a lot of her modern day influence through folklore and legend.

This tends to follow the beautiful, witty and bold character of Nur Jahan, and the Romance of Nur and Prince Salim’s, who would later become Emperor Jahangir. In general, the romantic and character aspect of Nur Jahan’s life as a story is better known than her political influence by most people in India, according to specialist historian Ruby Lal.14 These stories include her famously single handed hunting of a killer tiger, saving her subjects and amazing her husband who wrote in his memoirs Tuzuk-e-Jahangiri, in 1619: “Mírza Rustam, who after me

11 Tola, M.M. (2020). Nur Jahan the Light of the World. [online] DailyArt Magazine. Available at: https://www.dailyartmagazine. com/nur jahan the light of the world/.

12 Lal, R. (2018). Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan. W. W. Norton & Company.

13 Tola, M.M. (2020). Nur Jahan the Light of the World. [online] DailyArt Magazine. Available at: https://www.dailyartmagazine. com/nur jahan the light of the world/.

14 Past Loves Podcast and Lal, R. (2020). The Nur Jahan and Jahangir Love Story. [online] Past Loves . Available at: https:// pastlovespodcast.co.uk/2020/12/14/the nur jahan and jahangir love story/ [Accessed 18 May 2025].

has no equal as a marksman, has fired three or four shots from an elephant’s back without effect. Nur Jahan, however, killed this tiger with the first shot.”15 Another example of events highlighted in the folklore of Jahan is the rescue of her husband after he was captured by the Mahabat Khan, bringing the Rajput soldiers and nobles under her command to save him. An element of their legends without historical evidence is the legend of their meeting, in a disagreement of the whereabouts of two pigeons Jahangir left Nur Jahan to look after, which emphasises the beauty in her personality - her charm and wit and bravery. Nur Jahan’s political and social influence is much less acknowledged in this folklore, but her character is emphasised and celebrated.16

The erasing of Nur Jahan’s political power in modern understanding of her life is a complex history, but through contemporary criticism, misogyny of contemporaries and later historians, and the influence of the British Empire in reestablishing the image of India’s past, her work as a co-sovereign became much less well-known. “In the 19th century, orientalist renditions of the romance of Nur and Jahangir become very important in the histories of the time; later, the colonial renditions highlight and forward such stories. Nur Jahan becomes a classic oriental queen.” - Ruby Lal17. Despite the fading of the image of Nur Jahan as a political, social figure, her character and boldness came to hold a prominent place in folklore in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh in the centuries during, and following, her rule. Although many aspects of this are bound to be myth and untrue, some of this folklore is rooted in well documented events. In this way, the brilliance, if not the actual influence, of Nur Jahan has been highlighted through legend, which may be considered a leading reason for the significance historians attribute to her. Perhaps through this, and the following modern gaze on a romanticised past, she

15 Safavi, R. (2018). Was Nur Jahan a scheming temptress or just an independent woman who historians couldn’t fathom? [online] DAWN. COM. Available at: https://www.dawn.com/ news/1393959/was nur jahan a scheming temptress or just an independent woman who historians couldnt fathom [Accessed 18 May 2025].

16 Tola, M.M. (2020). Nur Jahan the Light of the World. [online] DailyArt Magazine. Available at: https://www.dailyartmagazine. com/nur jahan the light of the world

17 Past Loves Podcast and Lal, R. (2020). The Nur Jahan and Jahangir Love Story. [online] Past Loves . Available at: https:// pastlovespodcast.co.uk/2020/12/14/the nur jahan and jahangir love story/ [Accessed 18 May 2025].

has been drawn into an almost fictional character, exaggerating her influence. Following this viewpoint, in response to questions of why Nur Jahan is viewed as so significant, the answer would be: because she has been sculpted into a character that people admire and find entertaining and serves as an appealing root into a past world. People like this bold and charming heroic character of the past and the love story of the besotted Emperor and his muse, leading them into a prominent position in folklore. However, it could, of course, be that her importance is accurately reflected in these legends – they could be seen as further proof of her genuine significance in Mughal society. I would argue that to reason with these legends clearly it has to be acknowledged that for Nur Jahan to be made into an important character she must have had significant influence to begin with. Her current status in legend must, to an extent, be a reflection of her actual status in the past. Therefore, the reason for her significance cannot be folklore rooted in an unimportant ruler, there must be a more substantial reason for the attention she attracts. When looking at these stories, for example that of the TigerSlayer, one can see that they primarily observe and admire her uniqueness. Her personality, her power over the emperor who loved her, her bravery as a soldier, it is all reflected in these legends, leading to the conclusion that Nur Jahan attracted attention in folklore because she was unusual. She stands out because of the expectation and supposedly the norm of women and wives in this society to be subservient and left out of history book pages. This boldness and atypicality made, and still makes, her character appealing and even inspiring, so regardless of perhaps an overemphasis of her influence through these stories, Nur Jahan’s uniqueness brought fascination to her and is reflected in folklore and legend. This individuality and defiance of expectation could be seen as the reason for her established position in folklore and, furthermore, the foundation of her lasting significance.

Nur Jahan the woman

Nur Jahan was a woman and a wife, in a largely patriarchal society. This contributes hugely to the impressiveness of her political and cultural achievements and marks the conclusion of this discussion in the point that Nur Jahan gains attention because she stands out. She fascinates historians, contemporaries and the public because her personality, her position and her power are unexpected. For example, she inspires a character in folklore because she was bold where she was expected to be timid. Therefore the answer to questions of why so much significance