PAPERSCAPE

Crafting in

[Design Report]

PAPERSCAPE

Collective Crafting in a Post-Petroleum City

[Design Report]

Changhuan Xu s1718163

Paperscape explores the potential of architecture as a support structure in a post-petroleum context. The project focuses on the process and the act of constructing the ‘support’, involving not only structural but also social, political, economic and cultural engagement.

Experimenting with the craft and use of paper in the process of support, the project emphasises on the practice of material production.It encourages collective effort in making and crafting as a response to the post-petroleum condition.

How to Construct a Post-Petroleum World

Architecture as Support Structure: [2023-24]

Tutors:

Sepideh Karami

Naomi De Barr

INTRODUCTION 01

Architecture as Support Structure:

How to Construct a Post-Petroleum

World

“what might a post petroleum future be like and what might we need to do to nurture its timely arrival?

What support structures do we need to find, expand, construct or integrate in such scenarios to make a postpetroleum world possible?”

Architecture as Support Structure: How to Construct a Post-Petroleum World, Project Brief

The studio aims to expand the concept of architecture as a support structure, focusing on sites impacted by environmental, political, and social crises, especially those affected by extractive industries like petroleum and oil. The studio explores how architecture can facilitate alternative futures in these troubled sites.

By examining the pervasive influence of petrocultures, driven by speed, consumerism, and individualism, the studio addresses the societal entrenchment in cycles dominated by the petroleum industry. Through the exploration of petro-fictions and critical fictions, the studio discusses approaches to imagine and design a future beyond petroleum culture.

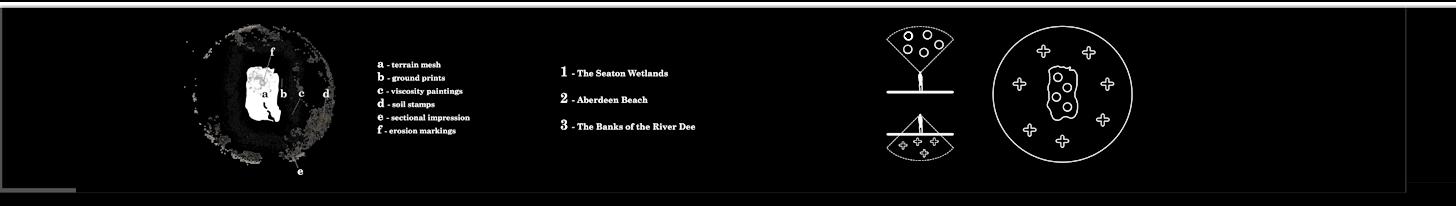

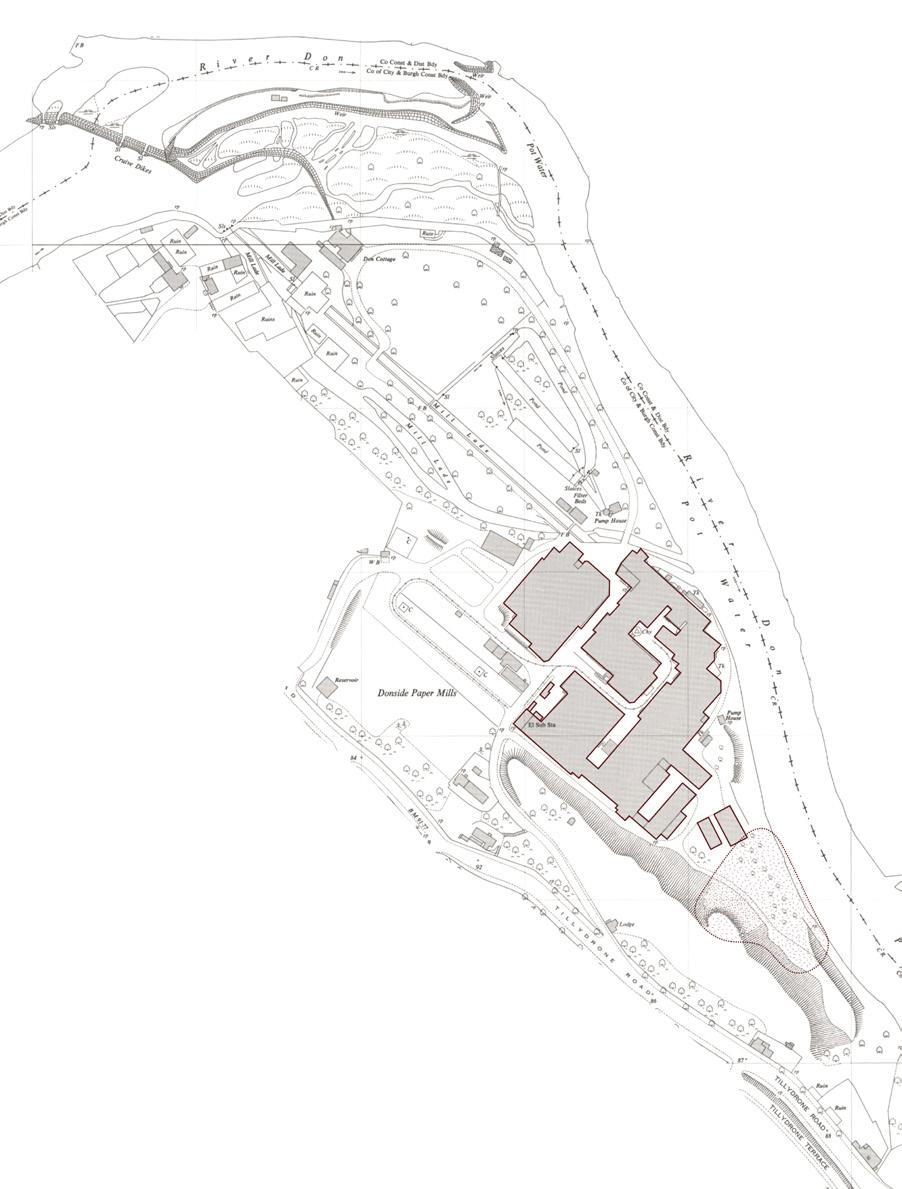

Water mills in Aberdeen. Base map from Scottish water mills website. https:// maps.nls.uk/projects/mills/index.html#zoom=6&lat=57.4000&lon=-3.7300.

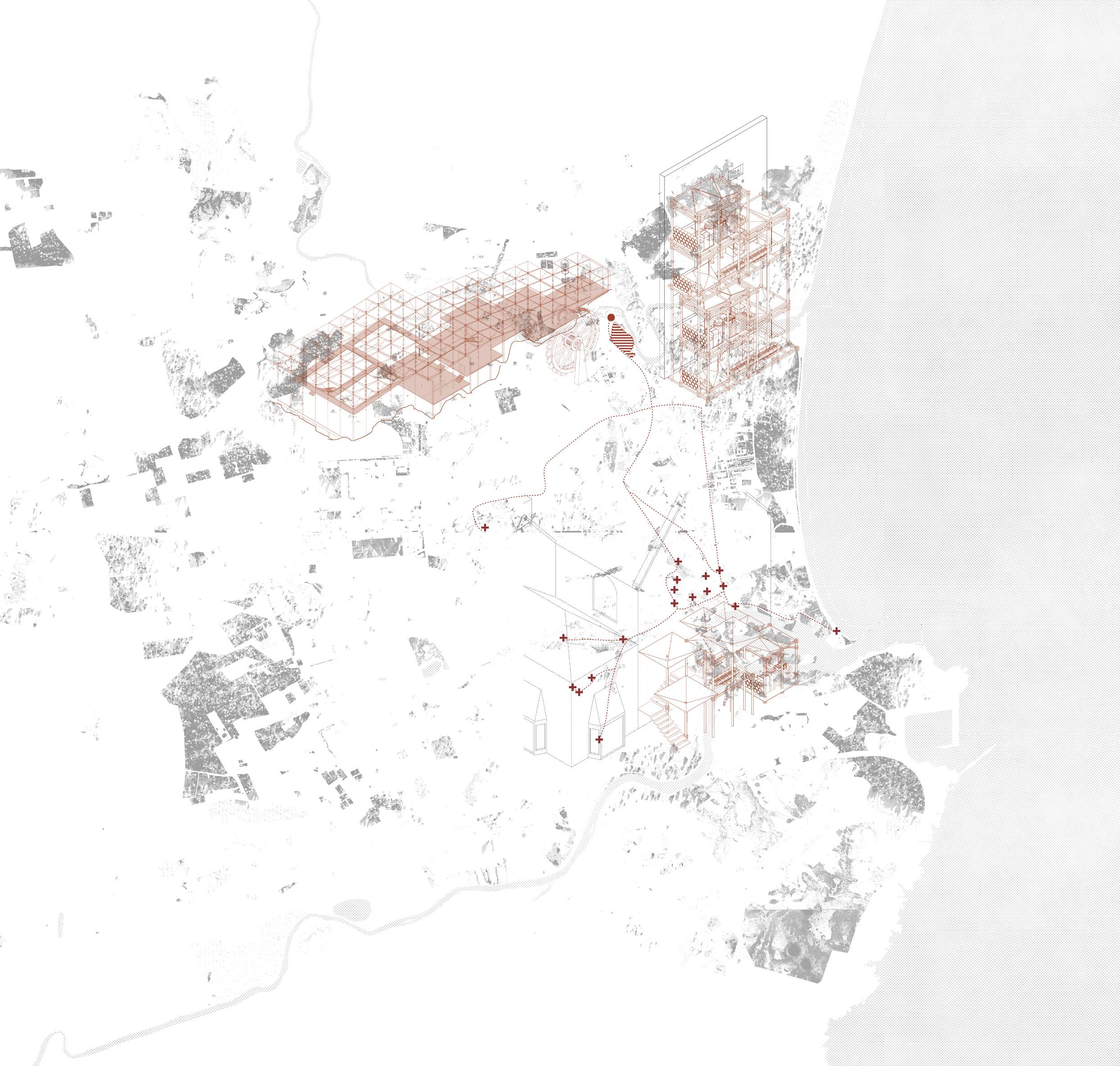

Fig.2 Aerial view of Donside Papermill (1928). Britain from Above. https:// www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/SPW022113.

History of Industries and Papermaking

Aberdeen

This studio explores the ecologies shaped by the oil and petroleum industry in Scotland, focusing on Aberdeen. Known as the Granite City due to its silver-grey granite buildings, Aberdeen has undergone a significant transformation from a fishing and manufacturing hub to the oil capital of Europe since the discovery of North Sea oil in the 1970s.

The history of Aberdeen is closely intertwined with its rivers, particularly the River Don and the River Dee. These rivers provided essential resources for various industries, including fishing, agriculture, and the operation of water mills. These mills were used for grinding grain, processing textiles, and papermaking. Aberdeen’s papermaking industry flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries, with the River Don providing the necessary water supply for production. The papermills utilised the river’s water for pulping and other stages of papermaking, becoming one of the major employers and contributors to Aberdeen’s economy.

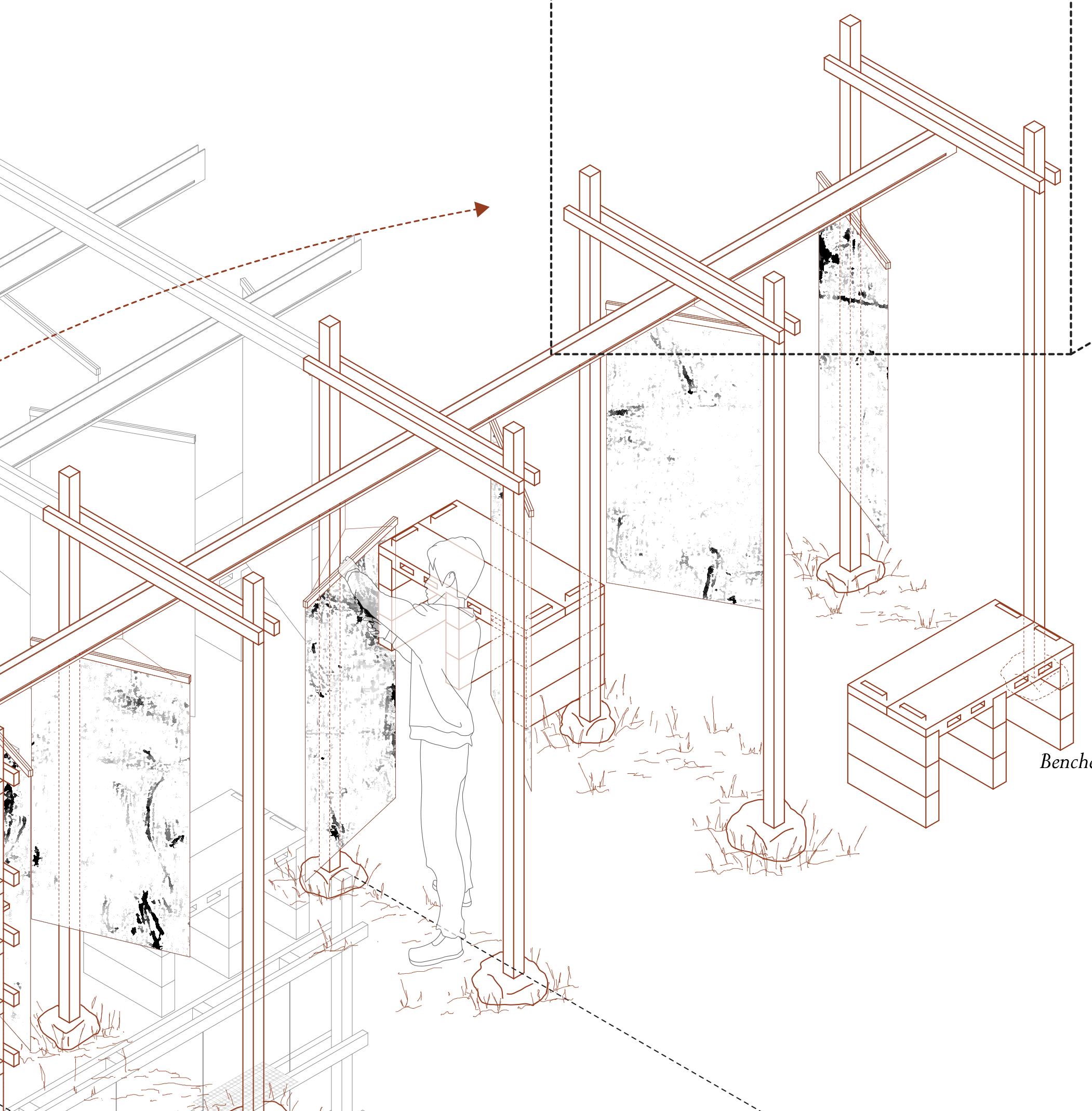

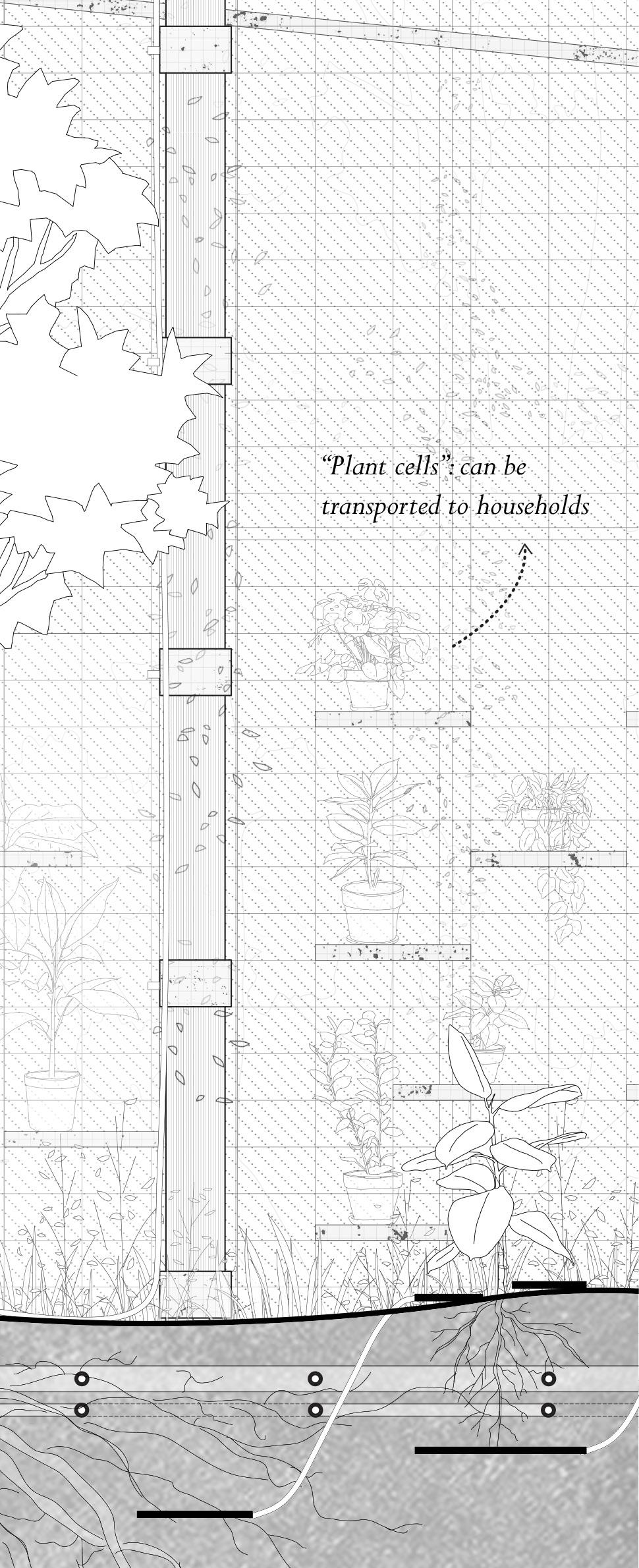

The rising of oil industry led to the decline of papermaking industry. The project aims to imagine ways to adapt the traditional industry in the post-petroleum context. Donside is chosen as the location of the new papermill for its rich history. Initially used for corn grinding and cotton processing, it was the first papermill in Aberdeen. An urban village was constructed on its original site after its demolition. Papermaking as a communal activity becomes a response to its history of both industrial and residential use.

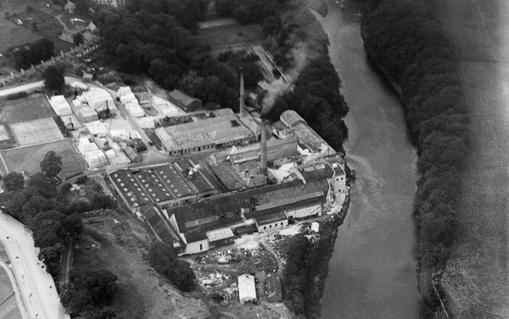

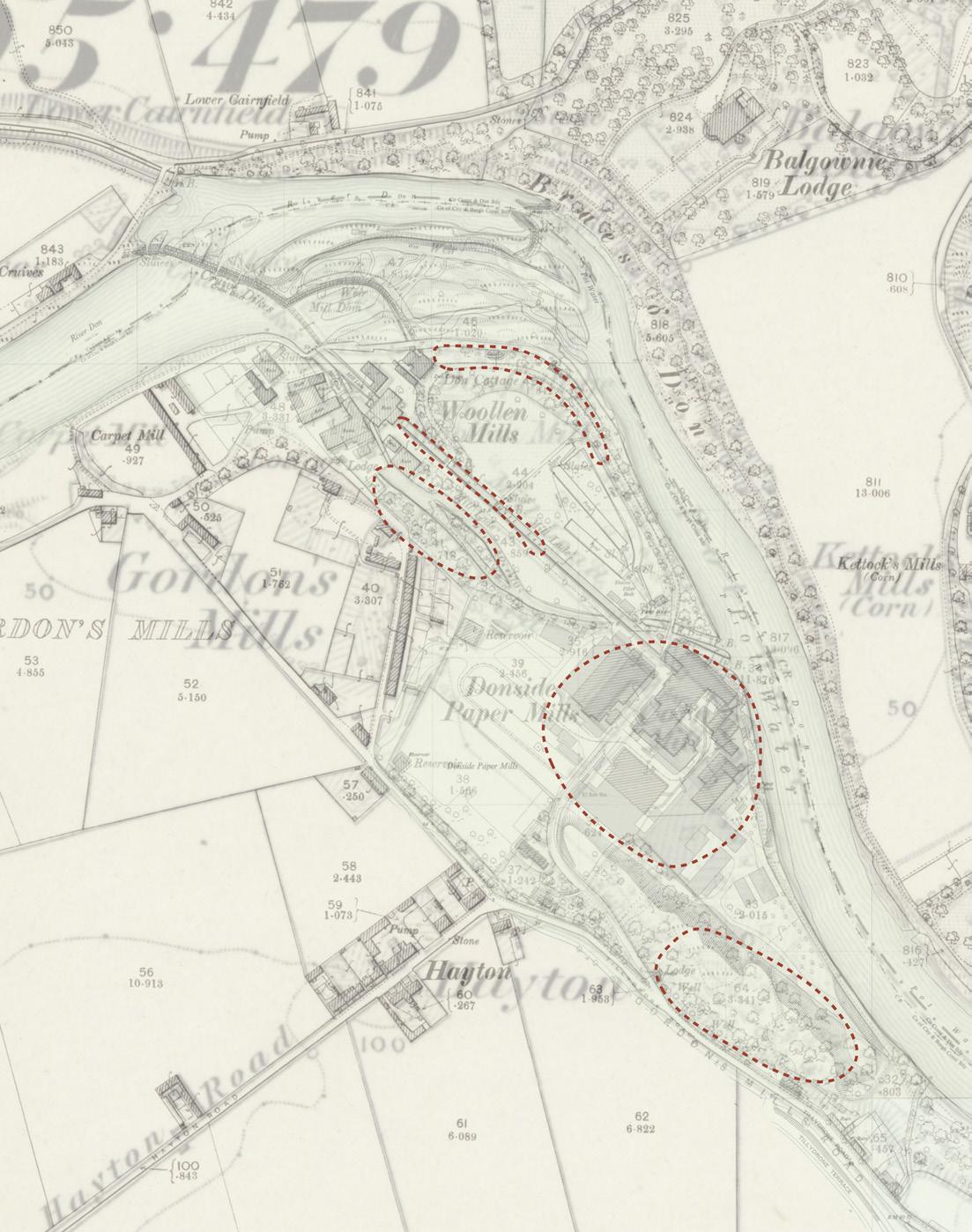

Fig.3 Speculative layers of ground of Donside

Fig.3 Speculative layers of ground of Donside

Collective Crafting

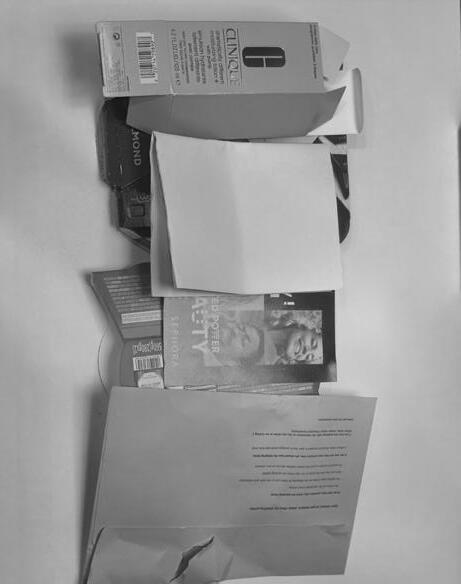

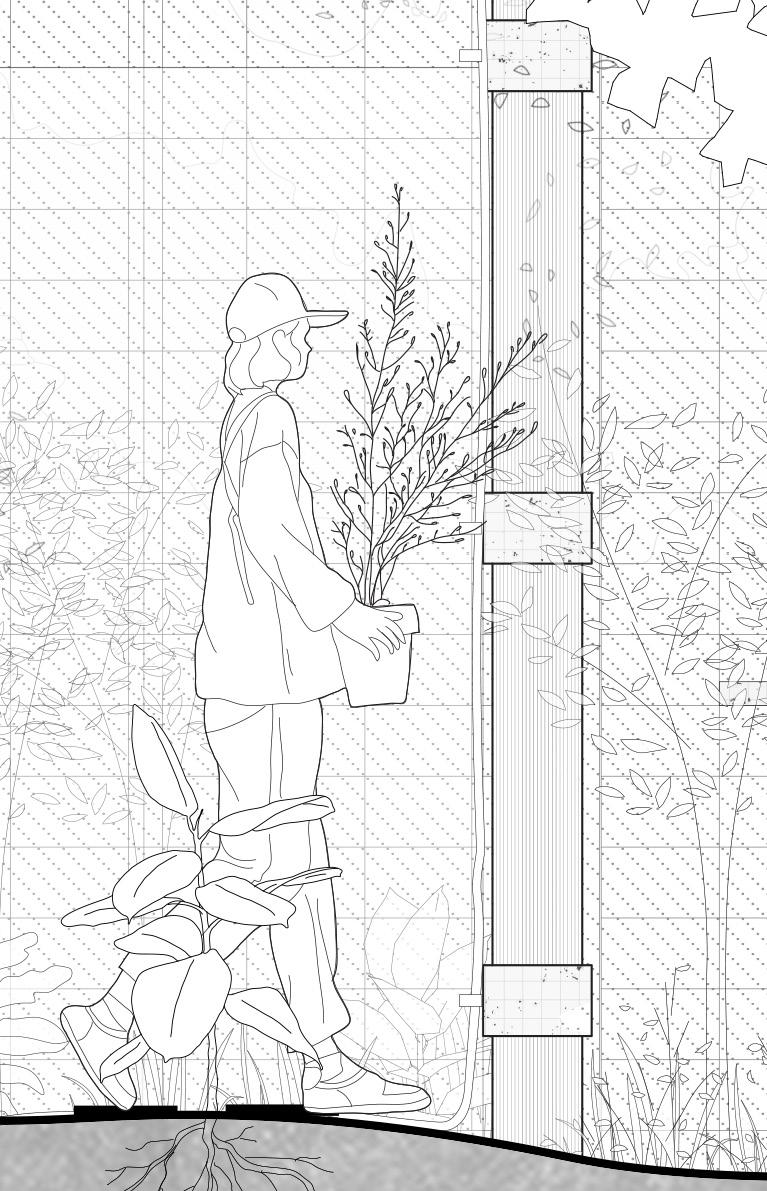

The project starts from an experiment with printmaking techniques, leading to a study of papermaking process. The raw materials for papermaking come from recycled paper sourced from various industries, along with branches and leaves collected from urban green spaces.

The papermaking process, which involves boiling and breaking down fibres, demands significant water usage. Domestic kitchens become ideal spaces for producing initial paper products. Starting with small extensions outside residential buildings, each household is equipped with the necessary space and facilities for papermaking. The products created in these facilities are then collected to establish a communal papermill, offering workshop space for various types of paper products, including sheets, small objects, furniture, and structural elements. These products are distributed throughout the city, initially serving the printmaking industry and eventually supplying various other sectors.

The project transforms the industrial process of papermaking into handcraft process. The act of making and crafting emphasises the process of production instead of the end products which were the primary focus in the petroleum era. Studying the process of papermaking offers a new perspective of viewing things from its formation and its source. The project is aiming at expanding this lens and discover the hidden layers of paper as an everyday object. The transition of papermaking from industrial production to a communal activity in a post-petroleum world brings the process closer to our hands and bodies, making it more grounded and tangible.

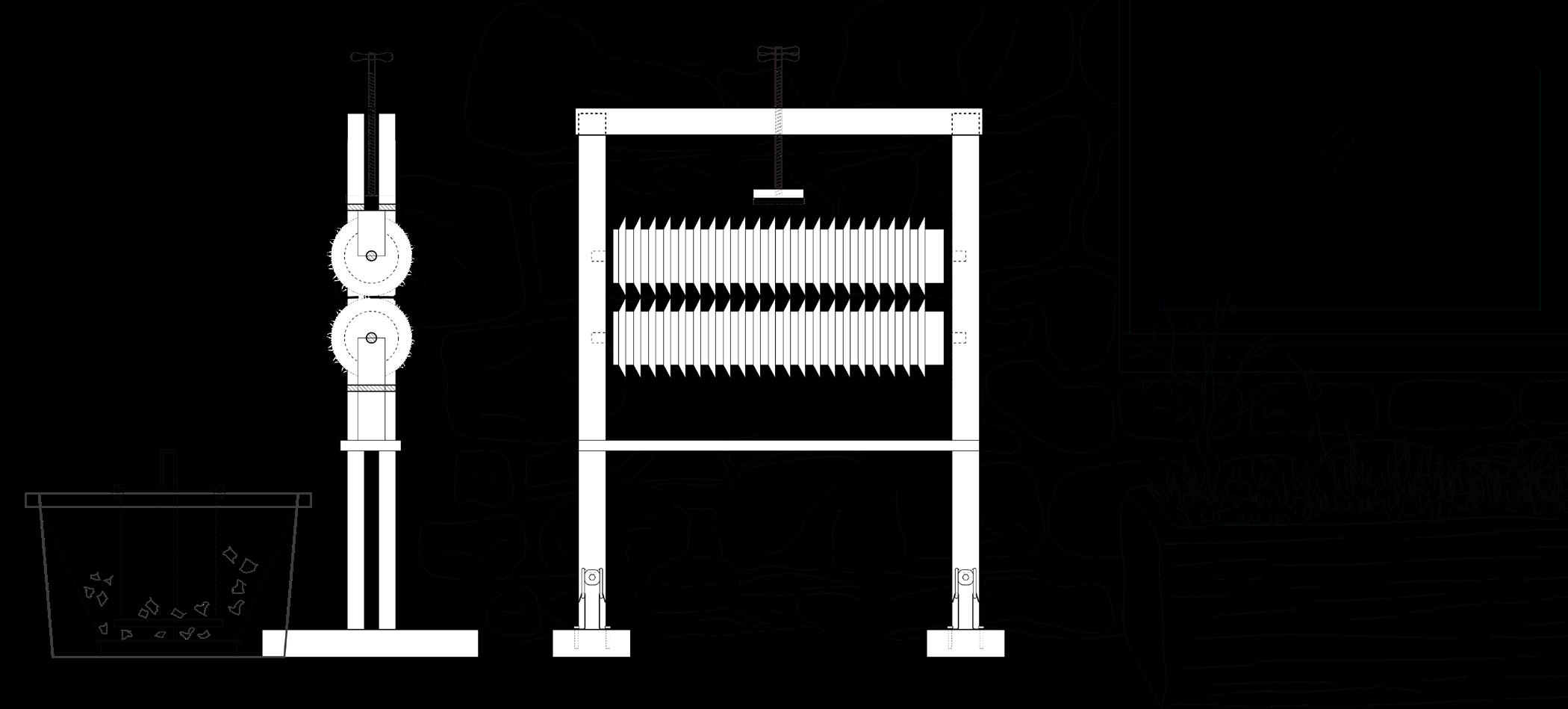

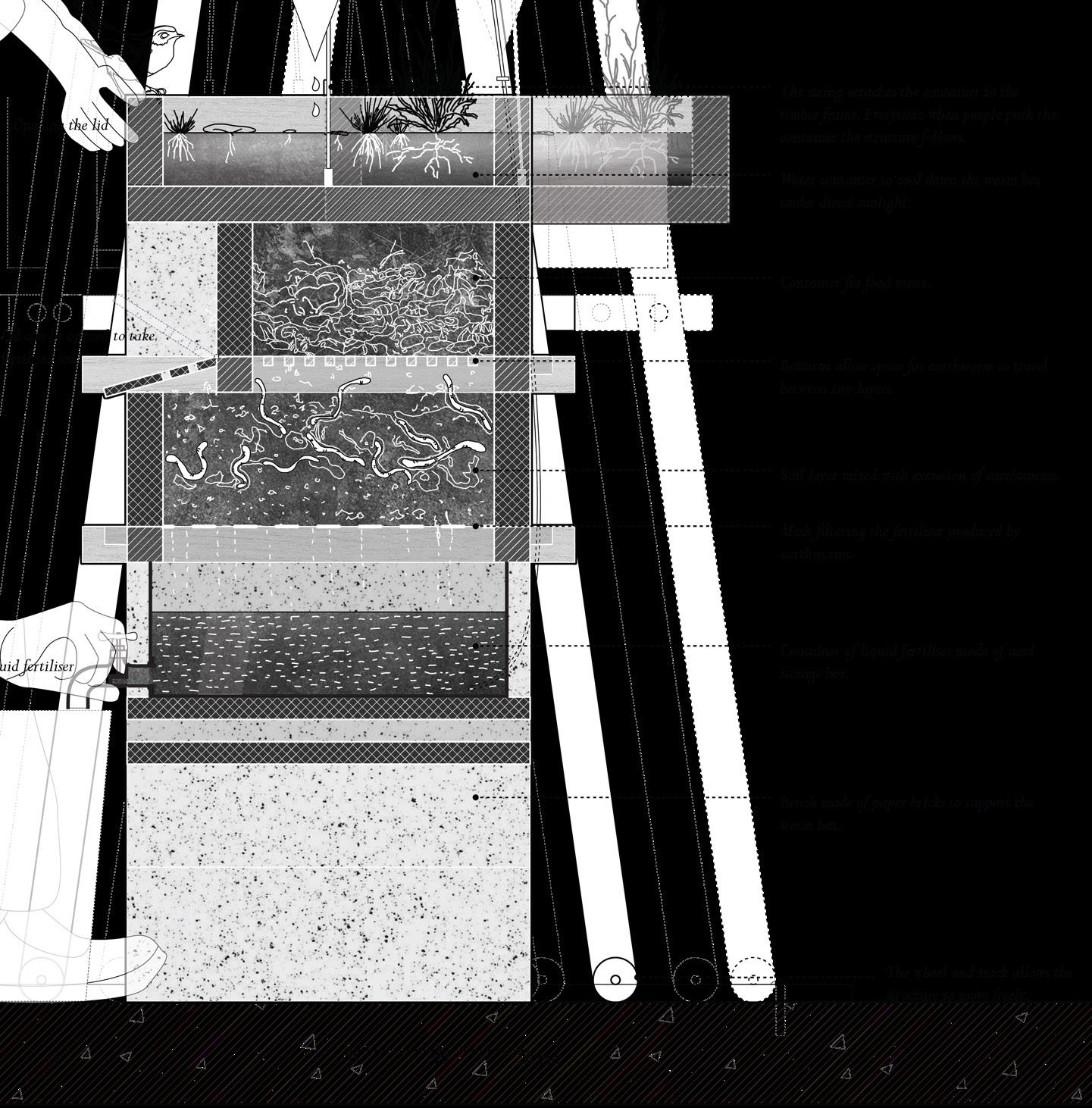

Fig.7 Paper Recycling device

Fig.7 Paper Recycling device

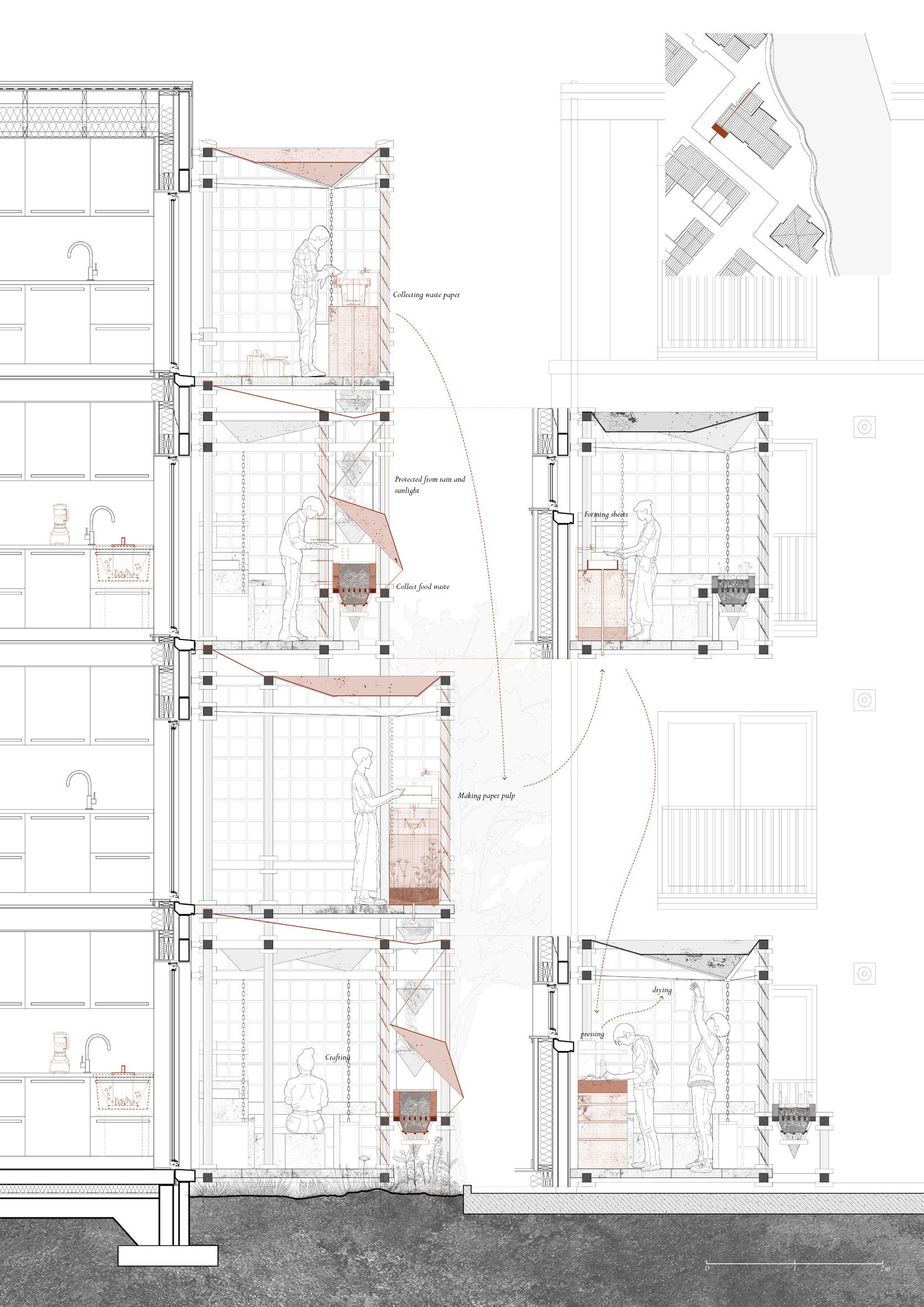

Fig.10 Kitchen ExtensionMaterial Processing

Fig.10 Kitchen ExtensionMaterial Processing

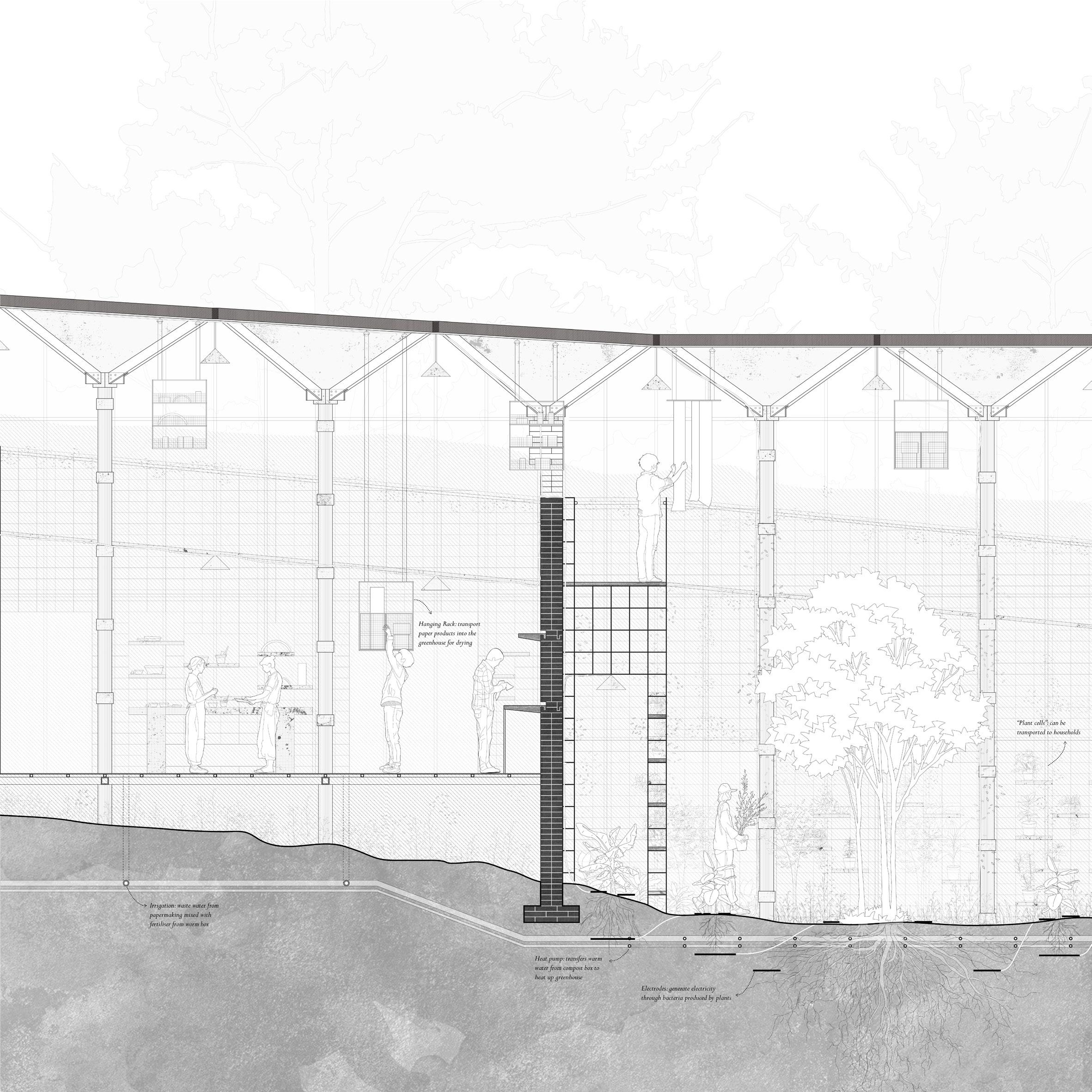

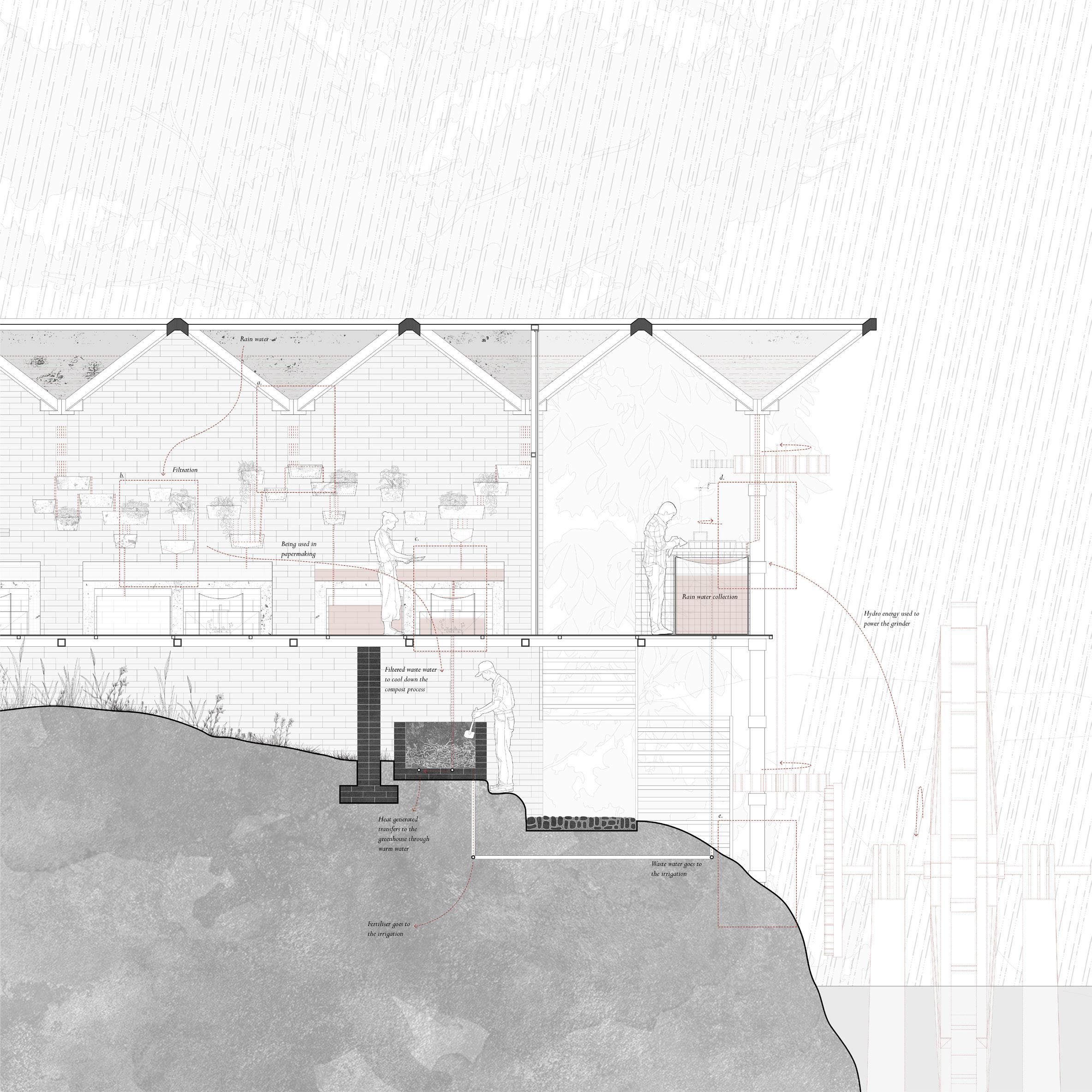

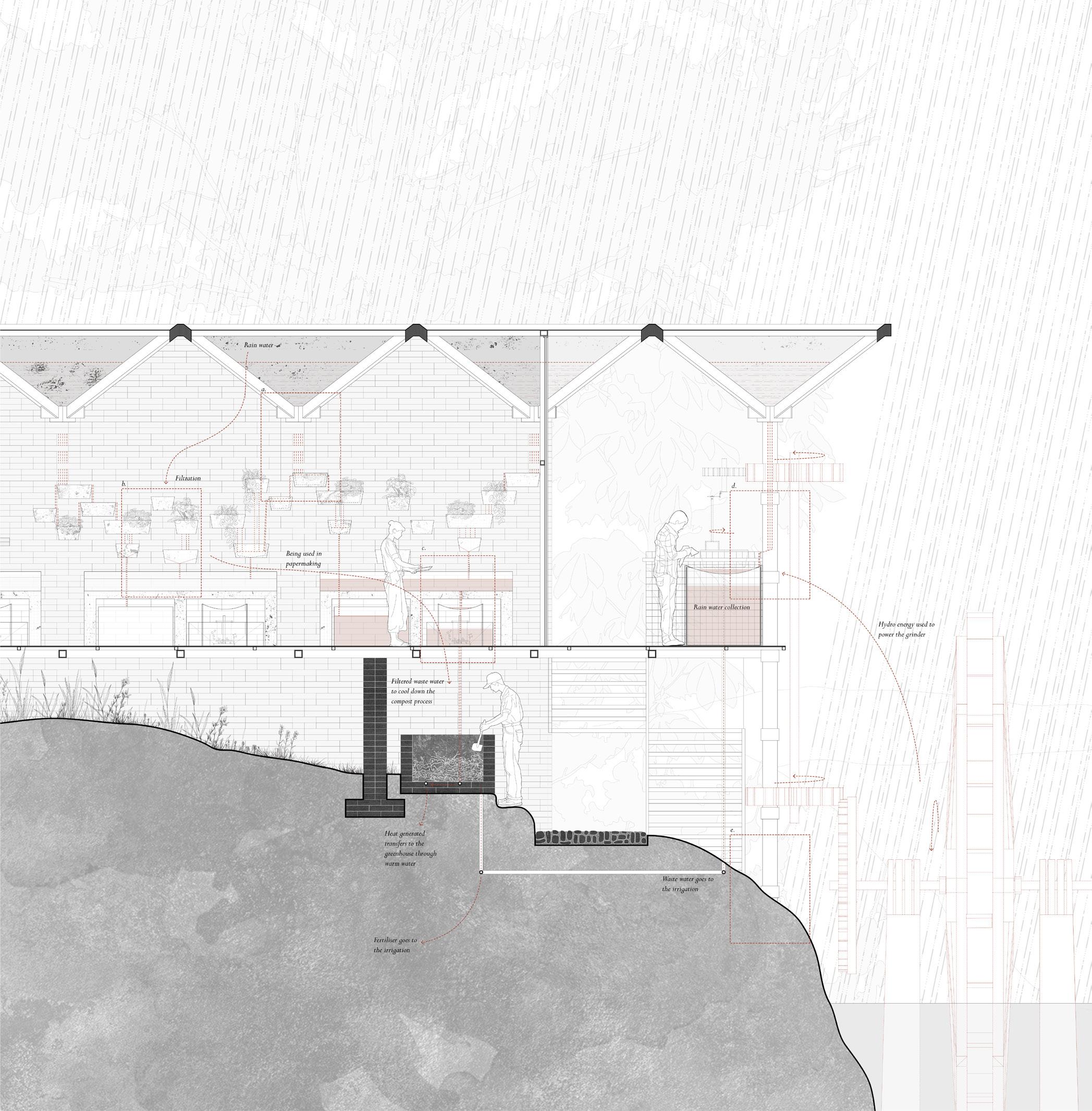

Fig.12 Papermill SectionWater System

Fig.12 Papermill SectionWater System

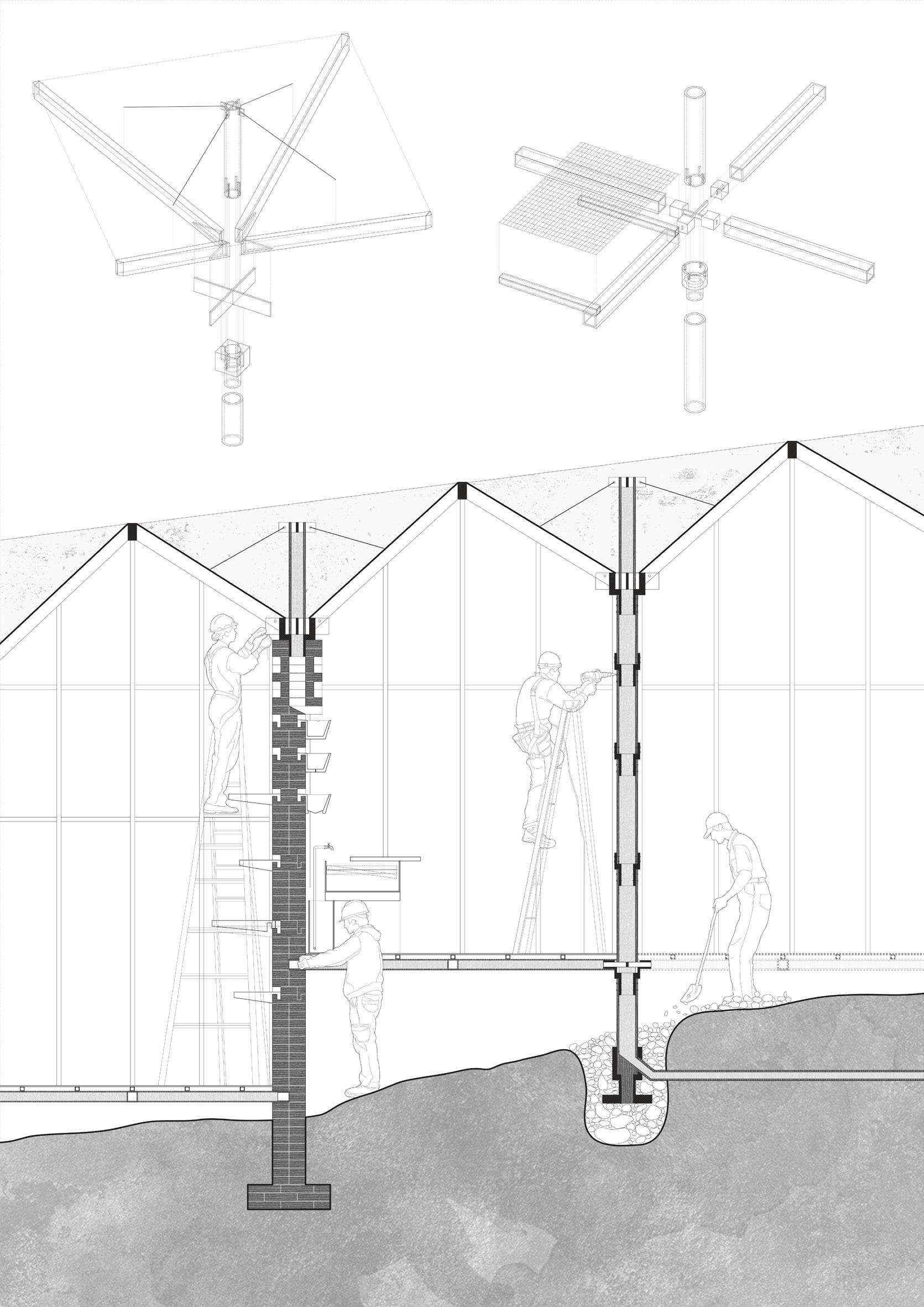

Papermill SectionConstrruction

Printmaking Device

Papermaking

Introduction

Paper Recycling Device

Making

Experimenting

Material Tests

Planting

Papermill

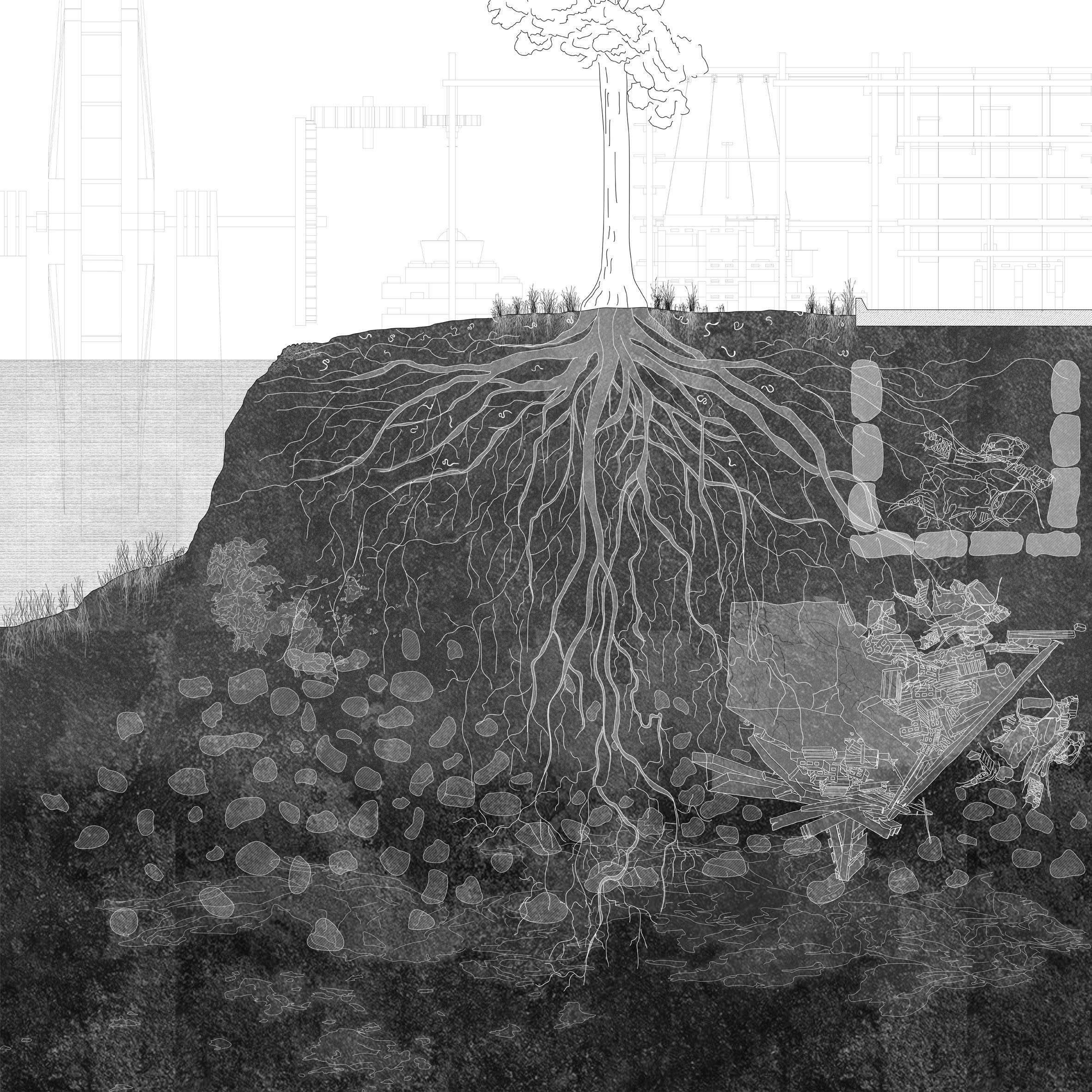

The body of this report is divided into 5 sections according to different methodologies – making, experimenting, mapping, storytelling, and sequences. When placing the tasks into the sections, they intersect with each other as the design did not follow a linear process.

Mapping Site Recording

Material Harvest Energy

Concept Tool Box

Characterisation

Typologies

Storytelling

New Professions

Paper Recycling Device

Streets: Worm Box

Papermill Sequences

Kitchen Extension

Papermill

Paper Stations

Reflection

MAKING

Making as one of the core methodologies in the design process helped to improve my understanding of the material, scale and the logistics behind the support structure. The tasks in this section include creating a sensing device, a ‘table’, and detail elements. The hands-on process of making facilitates iterative development, allowing ideas to be tested, refined, and improved through physical experimentation. Direct interaction with materials provides valuable insights into their properties and applications. Facing challenges that are not apparent in digital simulations guides my attention to the design’s mechanics and feasibility. Following the concept of transitioning the industrial production to handcrafts, making and testing things myself seems to be an effective approach to design.

Reconfiguring the table in the workshop

Architectural Devices of

(Un)Knowing

Printmaking Device

‘By embracing alternative tools, we can gain a fresh perspective and delve into the context with a critical eye, unearthing hidden facets that conventional methods may overlook. These innovative tools serve as a catalyst for generating unconventional narratives, steering clear of the repetitive and outdated accounts that currently dominate.’

The first task requires us to create a mapping tool to build a connection with the site. The tool aims to explore new perspectives of the context and uncover hidden aspects that conventional methods may miss.

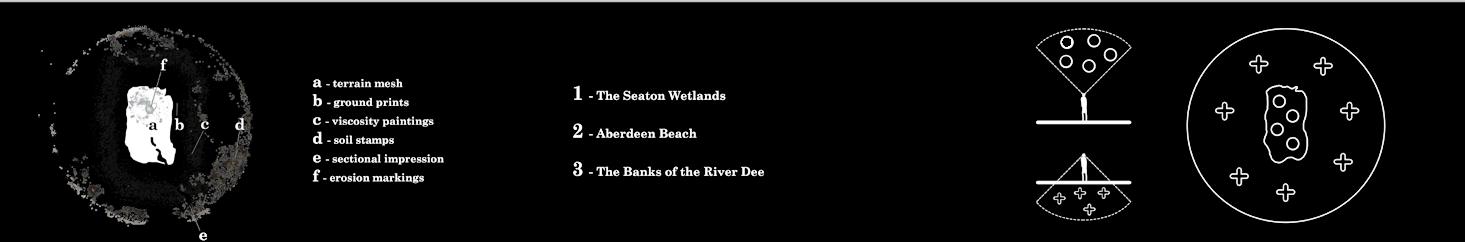

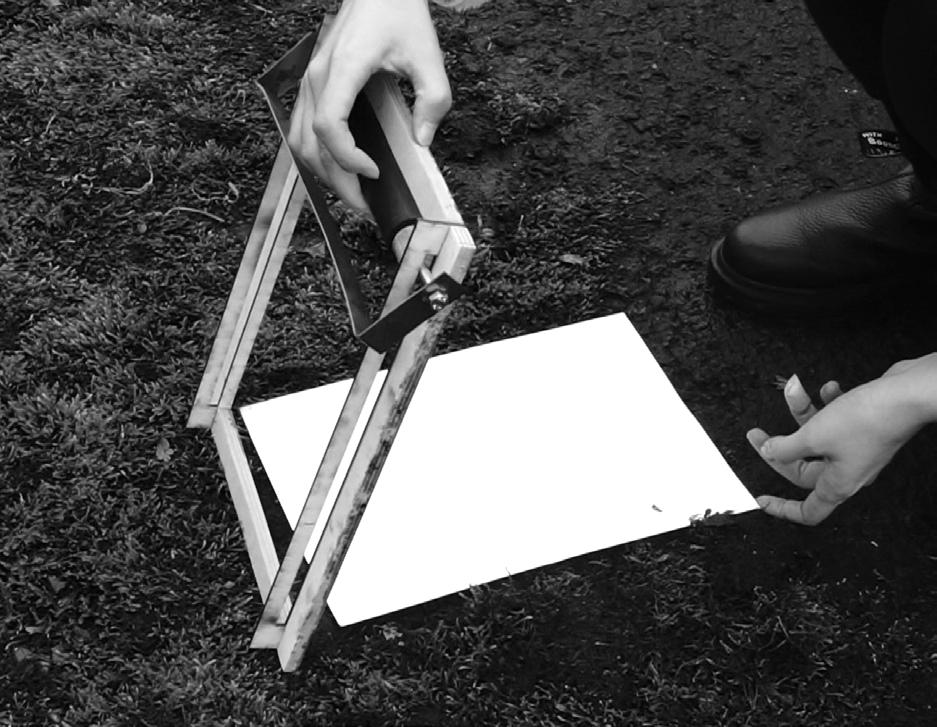

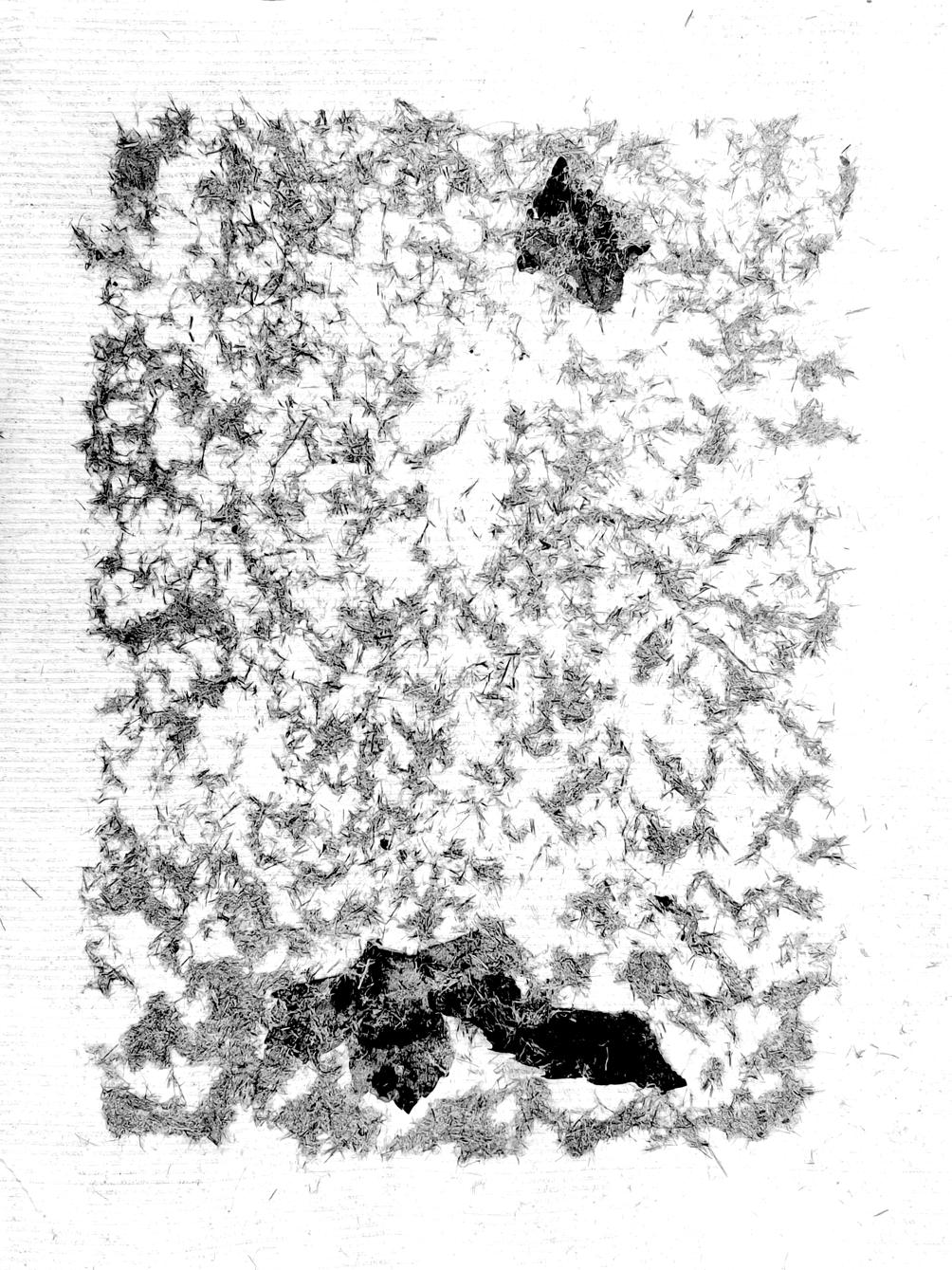

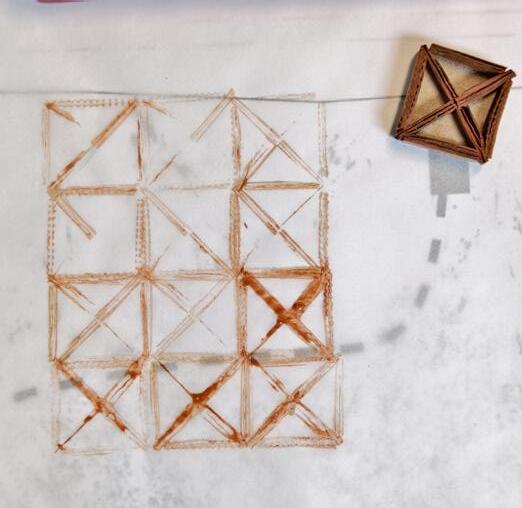

Being allocate in the mud group, the task requires to build strong connection with the ground. My narrative starts with the idea of recording the texture of the ground surface. Focusing on muddy situations, my initial idea was to use mud as ink to create imprints on paper. This evolved into the idea of a printmaking device.

I experienced several failures before figuring out the appropriate method of recording during the making and testing process. I reconsidered the flexibility of printmaking and explored different methods of collecting marks from the ground.This makes the process more valuable than the final outcome of the imprints.

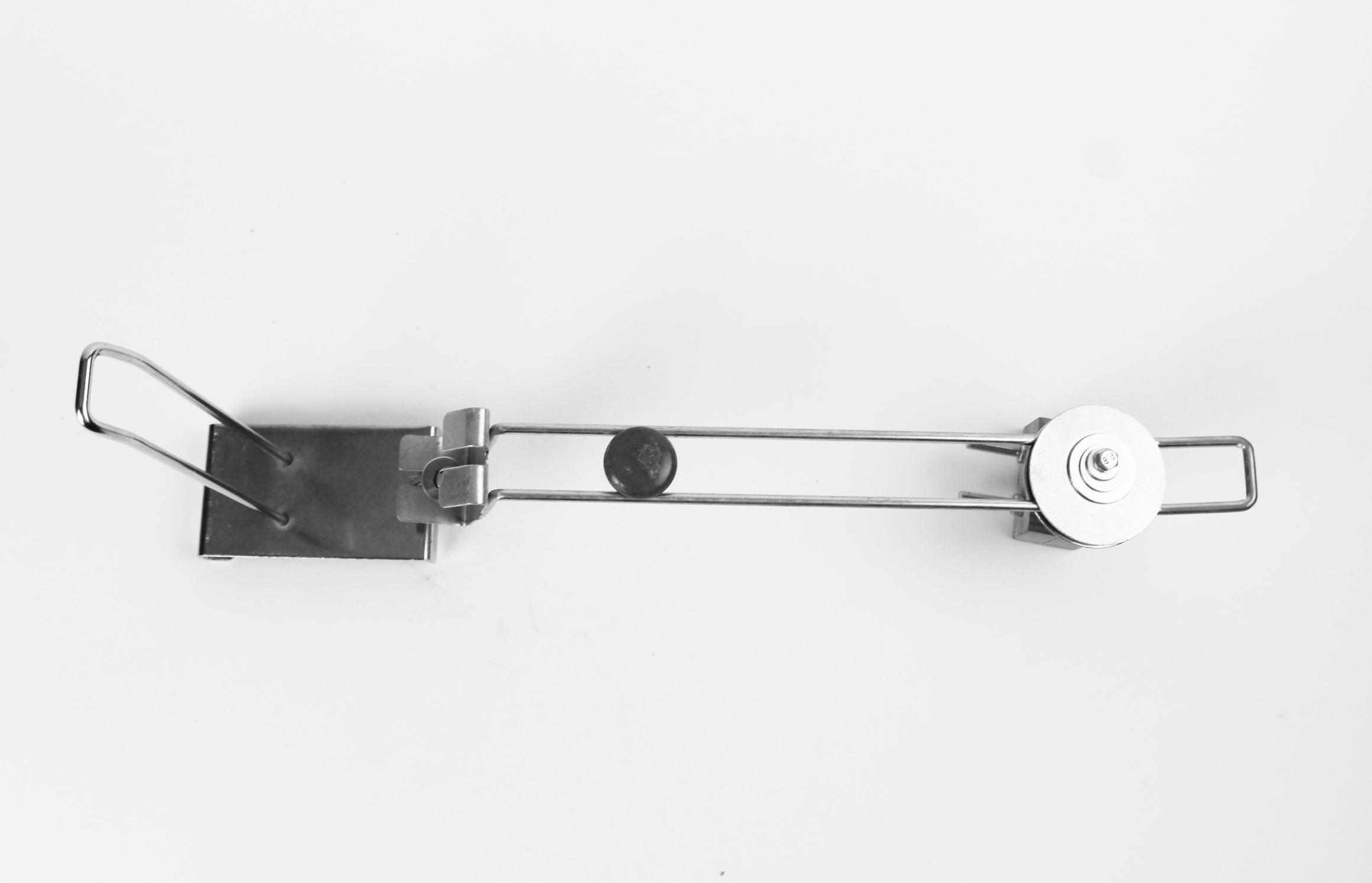

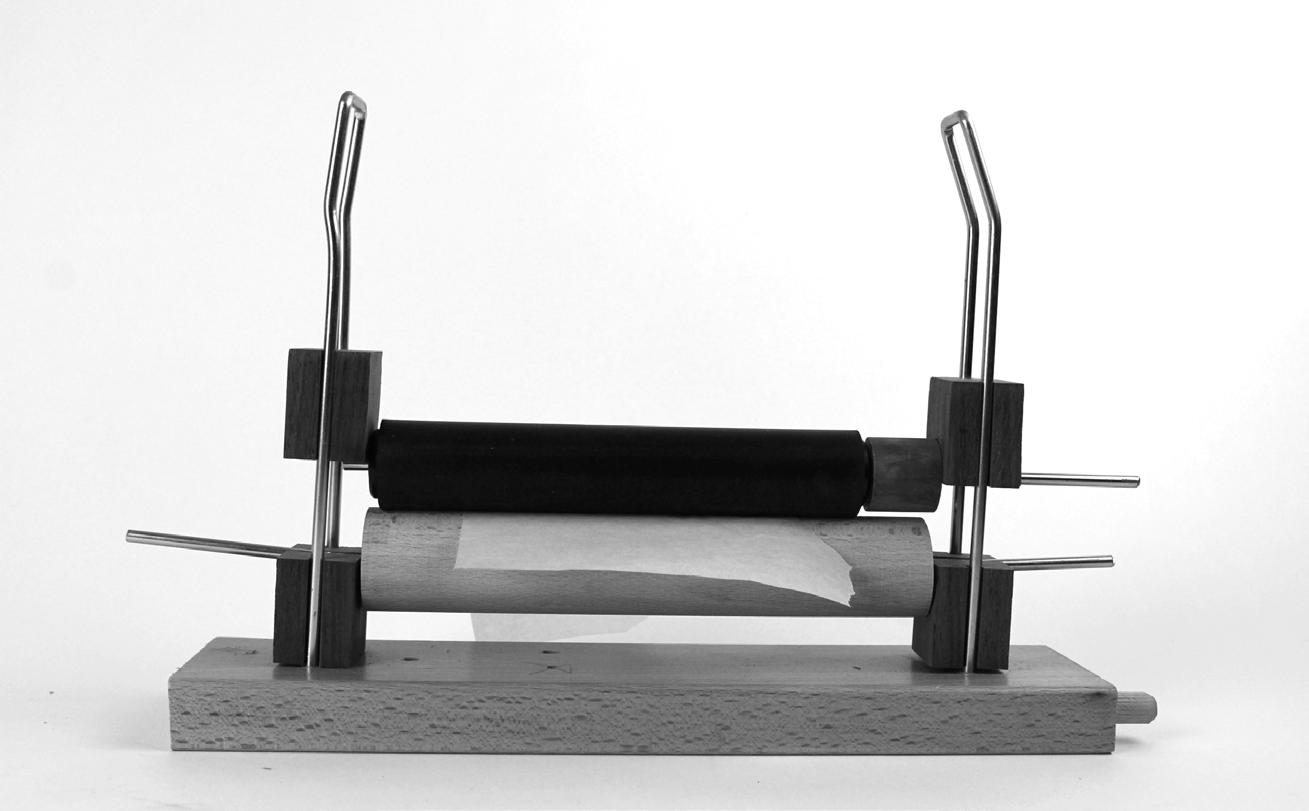

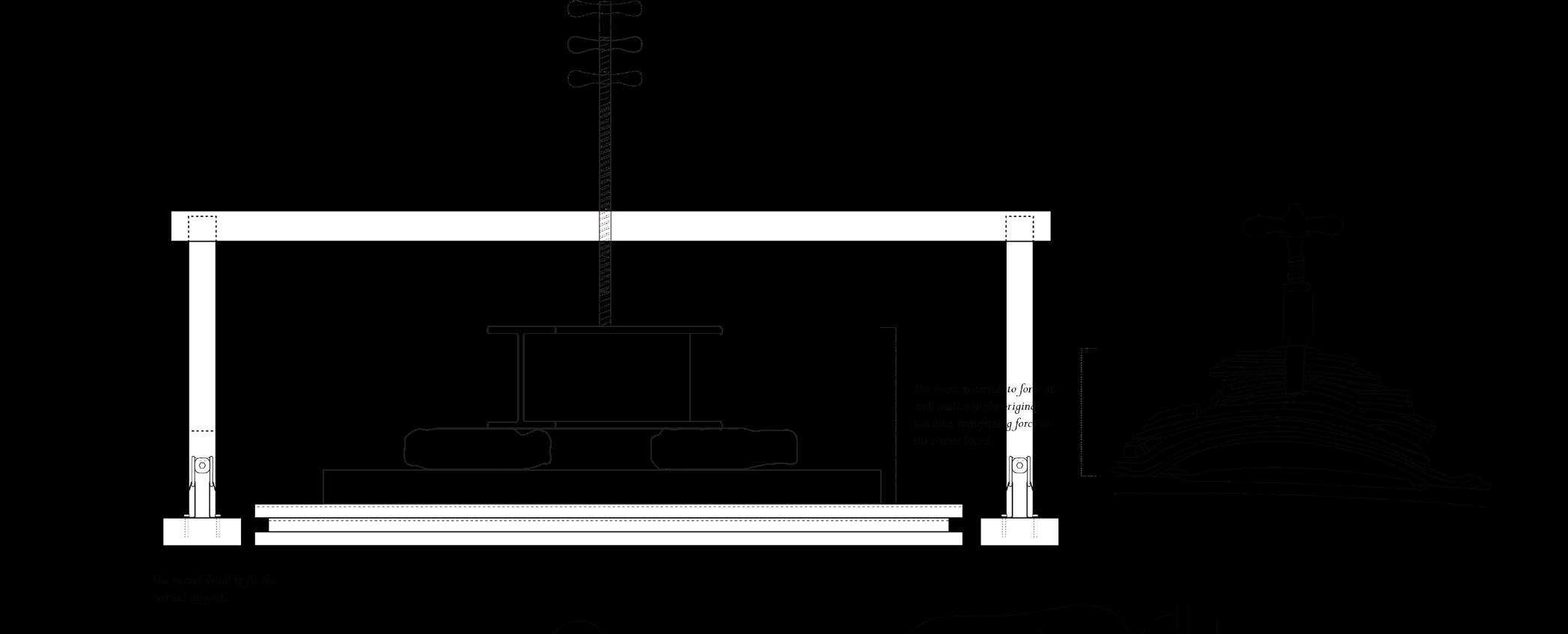

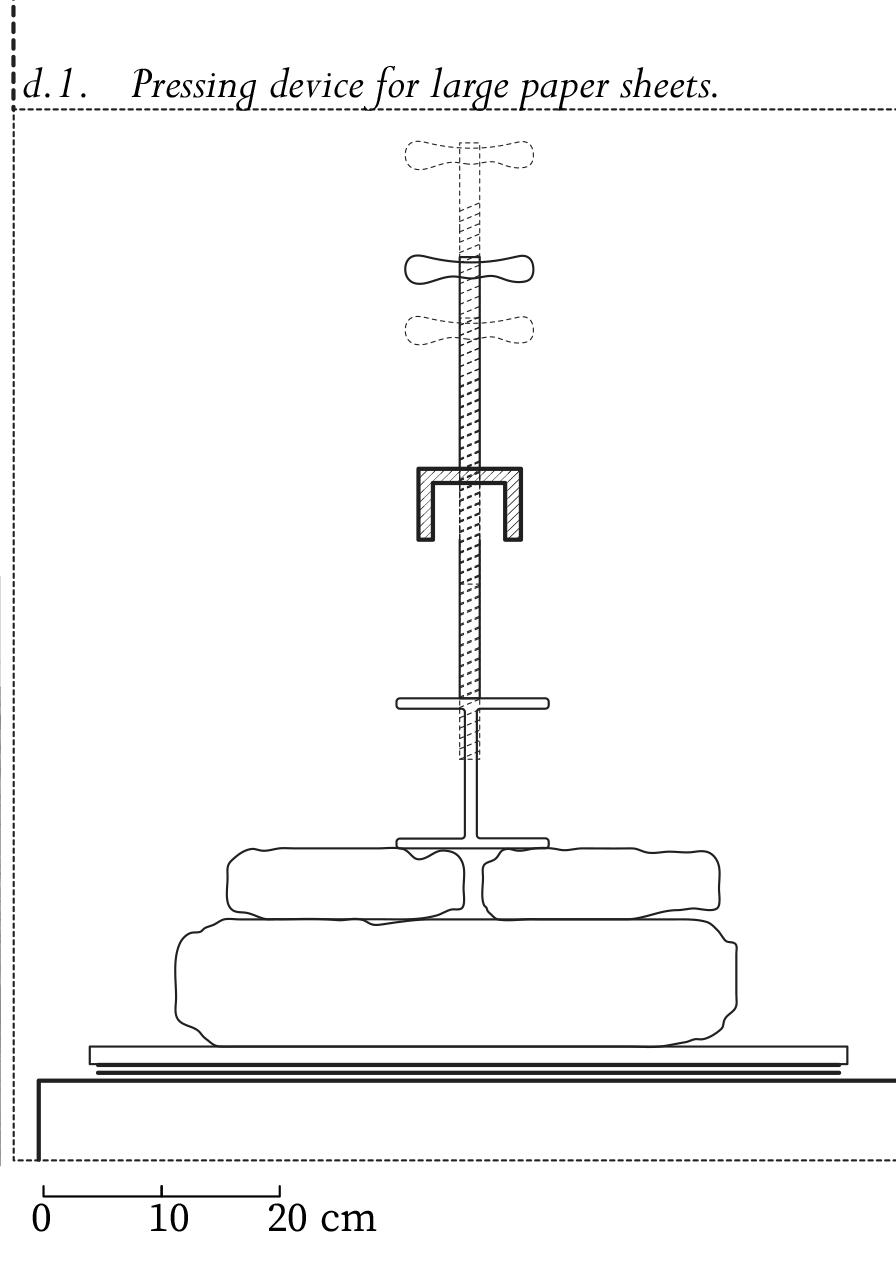

Printmaking Device v.1

After some research on printmaking techniques, I learned that rolling and pressing are central to all types of printing. I began constructing the device using a rubber roller I found, and added a track to limit its vertical displacement, thinking it would keep the paper flat during printing. The device finally broke due to its rigidity. The unevenness of the ground required the roller to be flexible to conform to the surface. I ended up pressing the paper directly onto the ground using a flat board.

Device Drawing

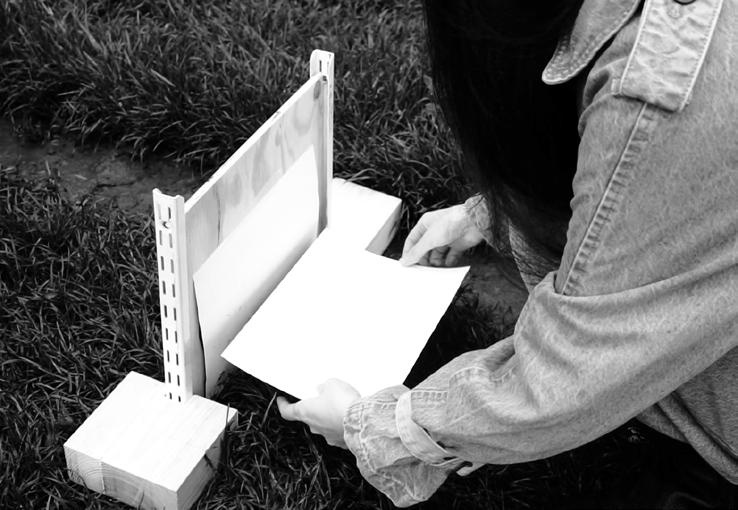

Learning from the failure of my first device, I developed a new iteration of the printmaking tool. I removed the track and replaced the roller with a rolling pin of a larger radius. To capture the unevenness of the ground, I added a vertical panel to the device. I disassembled the rolling pin and filed one end pointy to leave marks on the vertical panel using carbon paper, effectively drawing a section line as the pin rolled.

The test print in Edinburgh was very successful due to the rainy weather and muddy ground conditions. While setting up my device, I encountered several earthworms, which inspired further ideas for the project.

Constructing the Ground Research Design Tables

(groupwork with

Harry Monaghan, Mari Helland, and Maria Perez Caballer Baeza)‘The table is a ground that holds tensions between opposing and different voices. It is a ground for the pluriverse to take shape and one where the landscape speaks, and also where you, your team and your tutors will ‘design conversations’; it stands in for the site and it also stands in the studio.’

This task integrates on-site mapping with off-site table construction to explore and document site-specific narratives. Each group creates a unique table, starting with a simple structure and evolving it into a complex support structure that interconnects stories, materials and research findings. The table, serving as a three-dimensional map, reflects the social, political, economic and environmental aspects of the site, and incorporates objects and remnants from the site investigations. It also functions as a platform for discussion and engagement. This process aims to deepen the understanding of the site and envision post-petroleum scenarios.

Our group table is constructed incrementally, with pieces added gradually throughout the project as needed. It gradually evolves and shapes conversations among group members.

The table, purchased for £15 from Facebook Marketplace, was initially stripped and disassembled to explore its design potential and understand its material and structural qualities. The first intervention involved laser-cutting the ground of Aberdeen onto the tabletop, but this was abandoned to maintain the table as a working surface.

Constructing the Ground

Orientation

Our first intention for the soil box is to understand the ground thickness. It was later repurposed for practical use. The table became a working surface for model making, needing additional structural support for heavy objects. The dismantled pieces are reconfigured for better stability. The elements not only support the table structurally, but also support the activities we perform on the surface. A drying rack made from welding mesh and individual plinths were added for drying space. A drawer system was added for storage.

The evolving table, now used for various functions, included a frame for more workspace. The soil box collected work waste, becoming a basis for research. The tabletop accumulated marks and stains from different projects, recording our working process and fostering unforeseen interactions between projects.

The iterative making process allowed the table to serve multiple functions, becoming a dynamic and evolving support for our projects.

Drying

Hanging the Mould

Storage for Tools

Constructing the Ground

Details (De)commissioning

‘Local attention can lead to an understanding of the specificities of each place and also lead to a consideration of the inevitability of global connections. This task is about paying attention to the ordinary details that support aspects of everyday life of petroleum industry, infrastructures, or simply things that are held up.’

This task aims to bring attention to minor architectural details that support infrastructure functionality. We were required to find and draw three architectural details, identify their materials, and explore their connection to the petroleum industry. Then, these details are decommissioned and recommissioned to fit in a post-petroleum scenario.

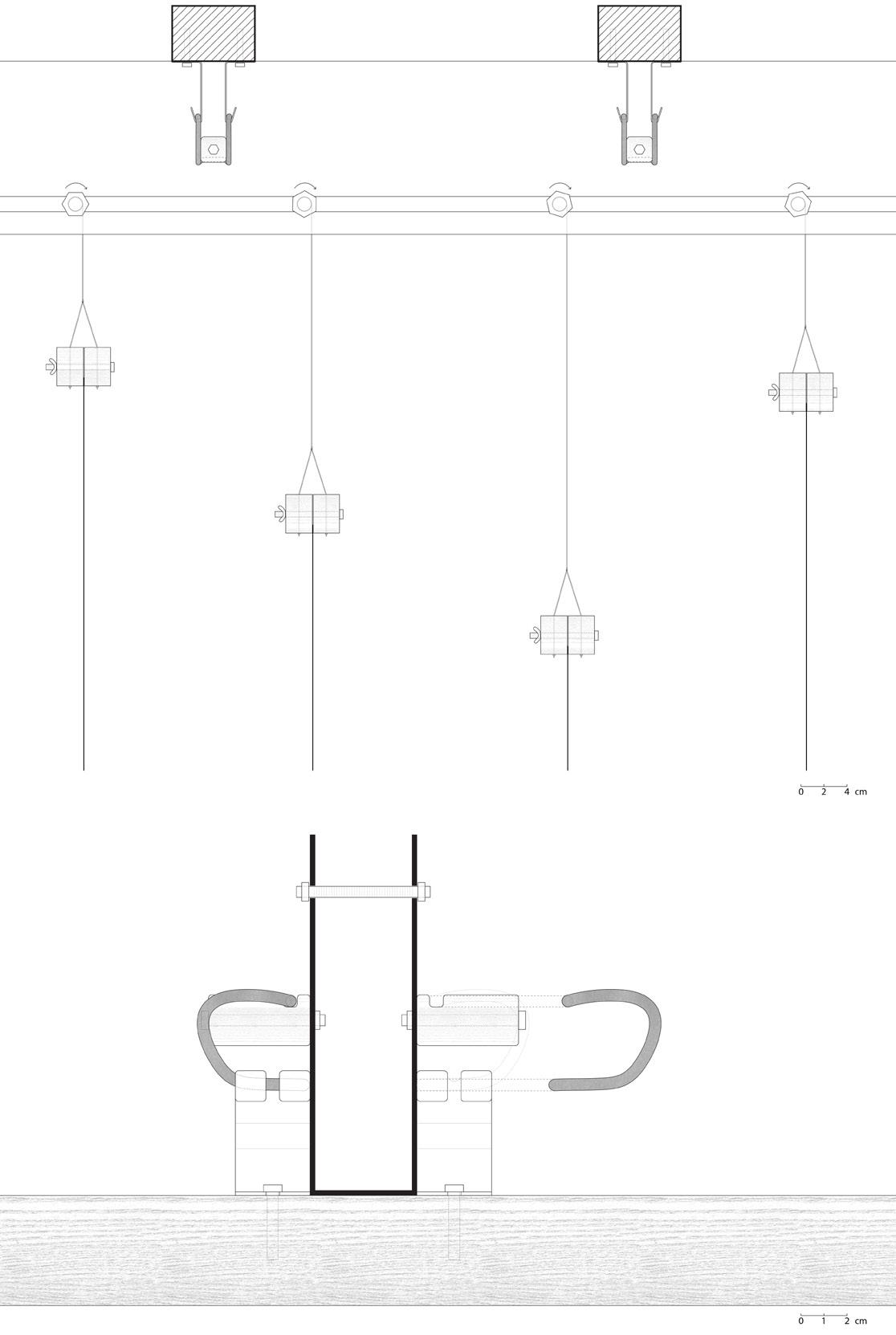

For the first detail, I focused on the elements supporting the tram cable extended from the utility poles.

The cable is secured by strings attached at two points, maintaining it within a specific height range. The flexible arms constrain the cable’s horizontal movement while allowing flexibility as the tram passes.

In modeling this detail, I preserved its functional logistics but used recycled materials instead of replicating its exact form. This approach encouraged creative thinking for its recommissioning.

The second detail is the steel buckle that fixes the railway track to the concrete sleepers. The elasticity of the steel reduces vibrations transferred from the train wheels to the ground.

The main focus on this detail is on the fixing and the property of the track. Following this mechanism, I dismantled each piece and created buckles using recycled hooks found in the reuse hub. This process not only involved recommissioning the detail but also repurposing materials I found.

The model was also used as a shelf holding some of the tools and paper. As a physical object, it gave me ideas of recommission through everyday experience.

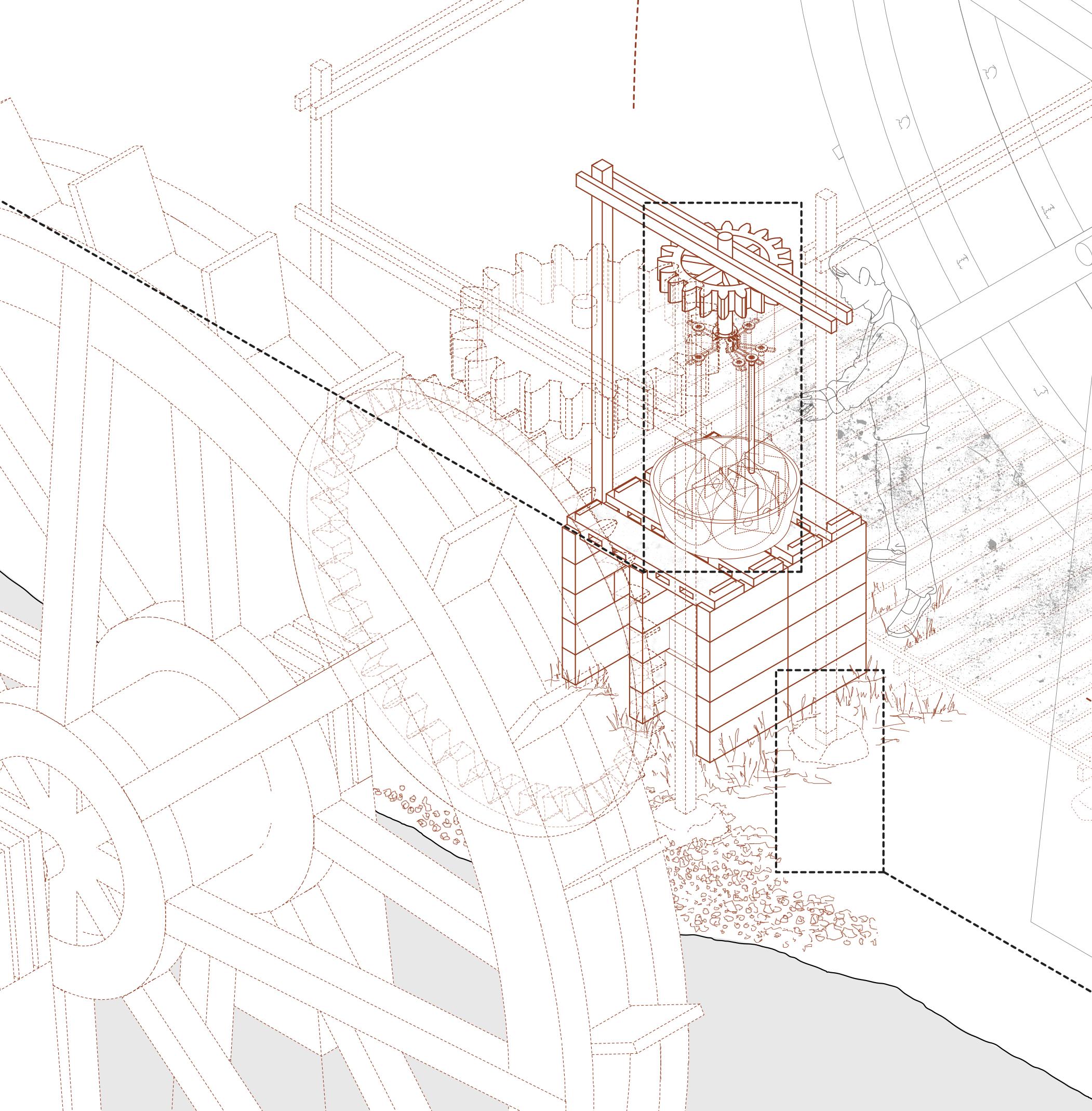

The third detail is a mangle machine I found in Foot Dee village, left outdoors and gone through weathering.

Originally, the machine’s function was to squeeze water from fabrics. It comprises two main components: a top press and gear sets for the rollers. The top screw tightens the steel arcs, adjusting the space between the rollers, while the gears rotate the rollers simultaneously to feed fabrics through.

For my model, I repurposed the roller from my earlier failed device. However, due to the limitations of the material, the model was too small to physically experiment with the rolling and pressing functions effectively, making this aspect of the process less successful.

Support Structures

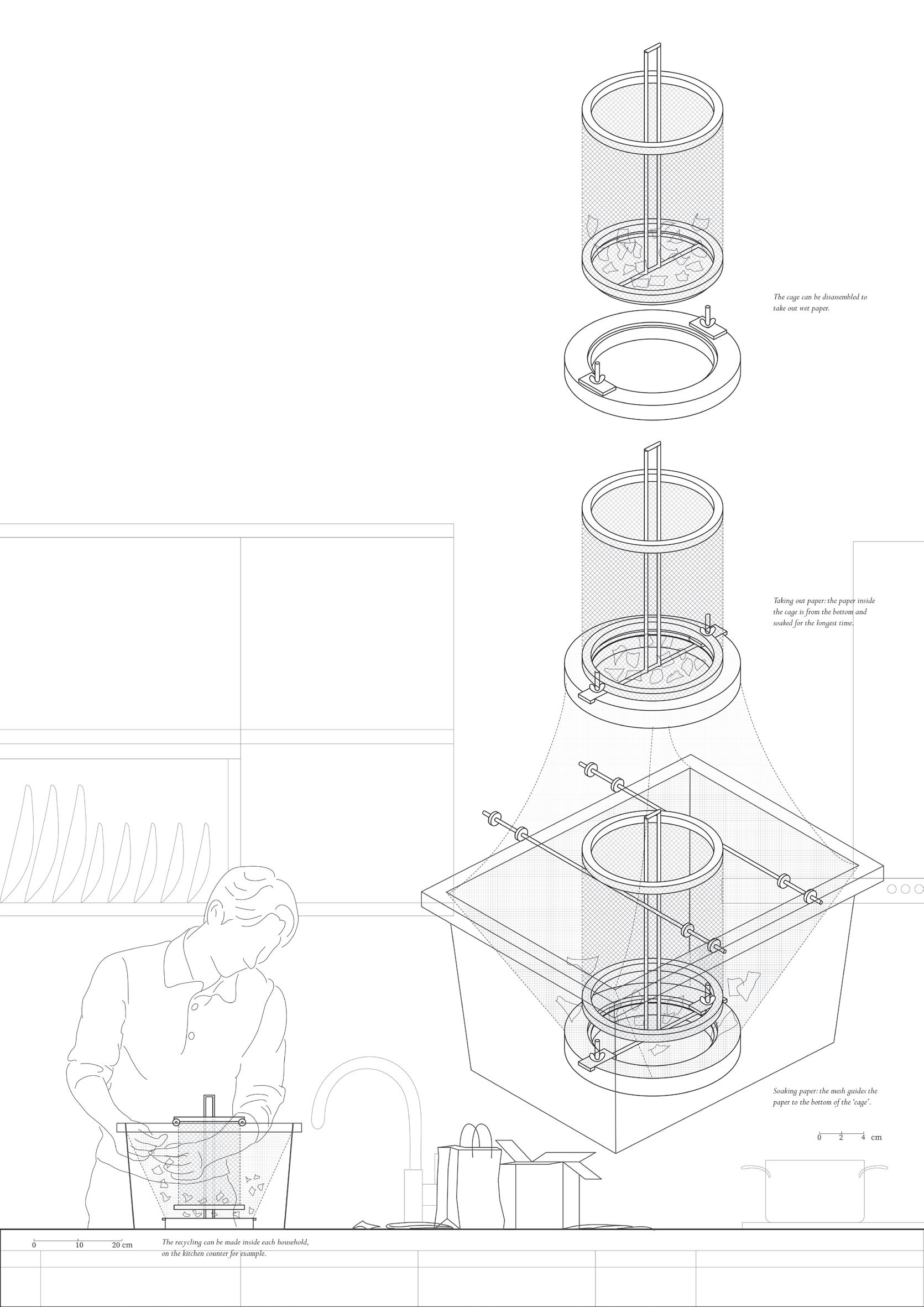

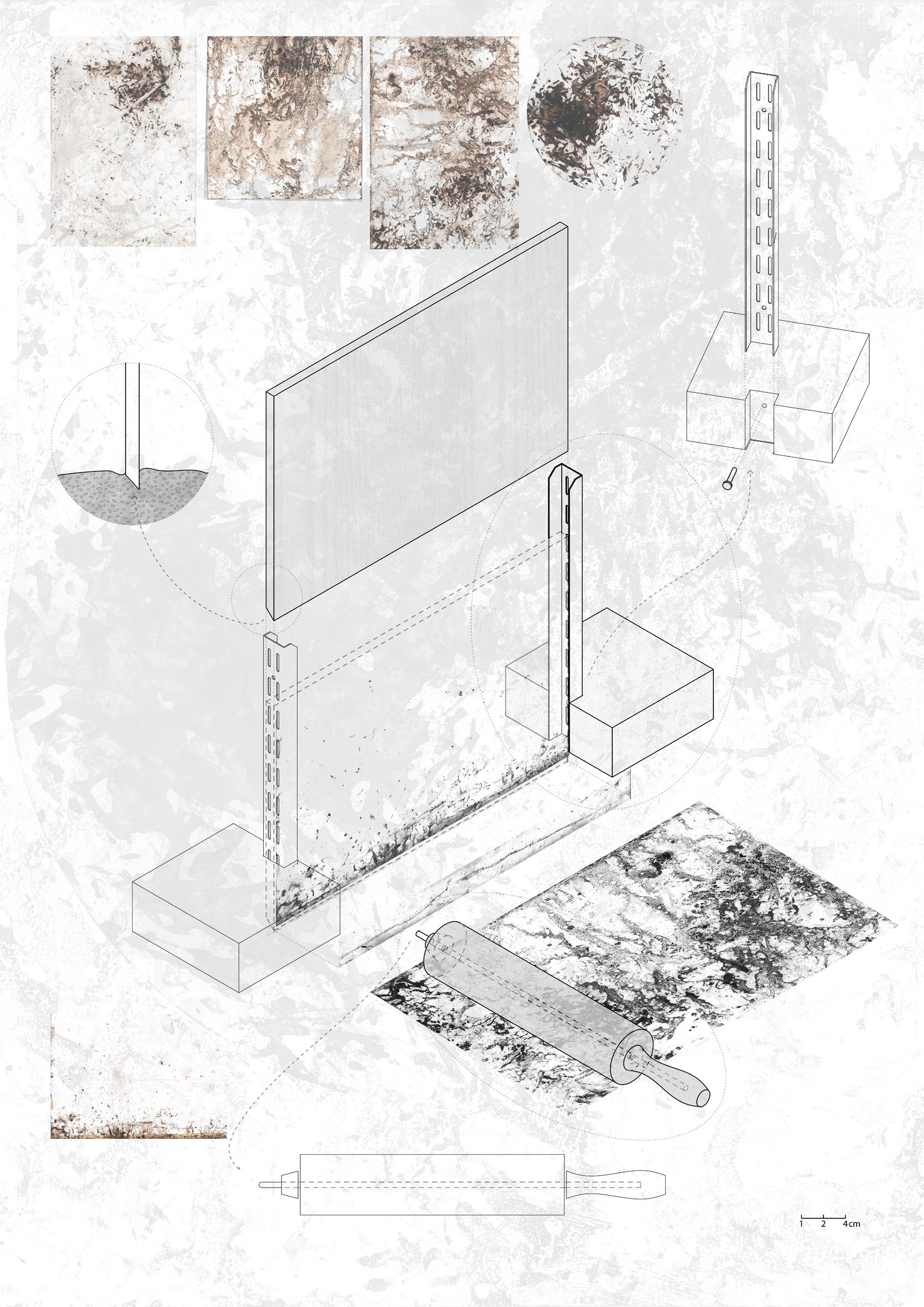

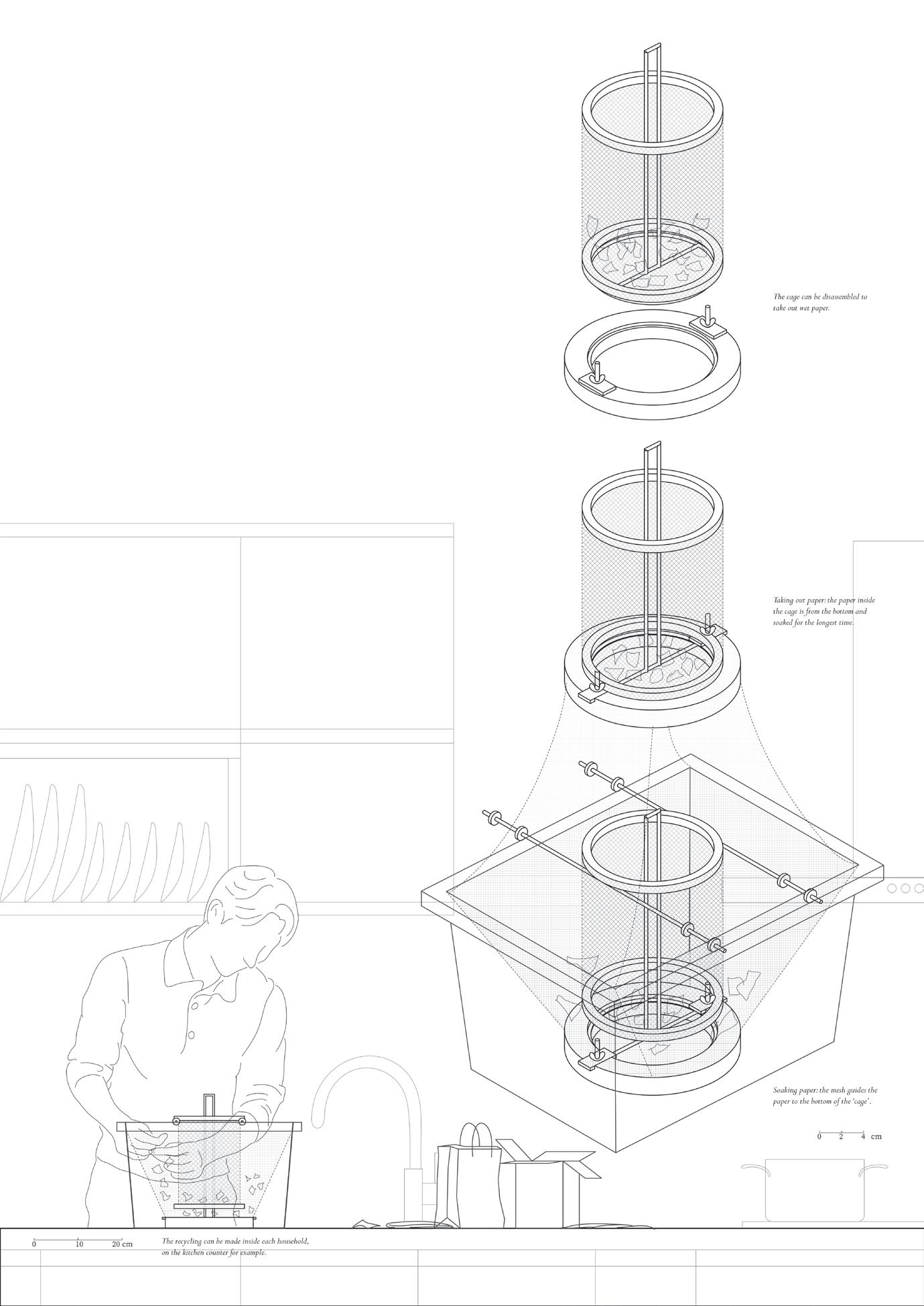

Paper Recycling Device

This task explores how architectural proposal embodies the concept of architecture as support structure. The support aspect of the design is emphasised.

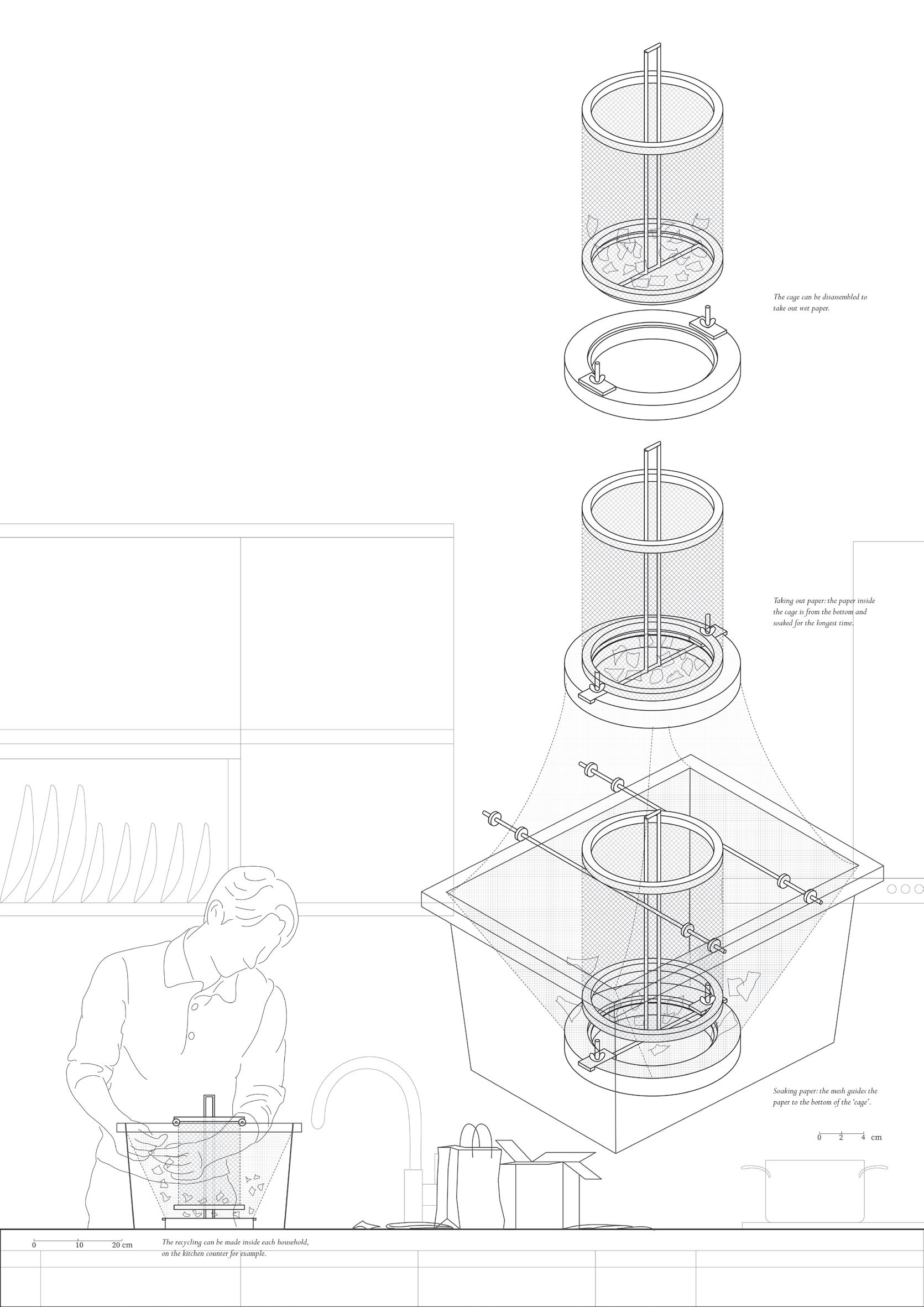

My first support structure is a paper recycling device. To take out paper from the bottom of the container, this structure consists of a mesh fabric and a cage. The mesh guides the recycled paper to the bottom of the plate. When the cage is lifted, it catches the paper from the bottom, ensuring it is better soaked. This structure can be fitted into any container and used domestically.

This 1:1 model helped me to understand the feasibility of the mechanism which helped to adjust the design.

Architecture of Support Structure

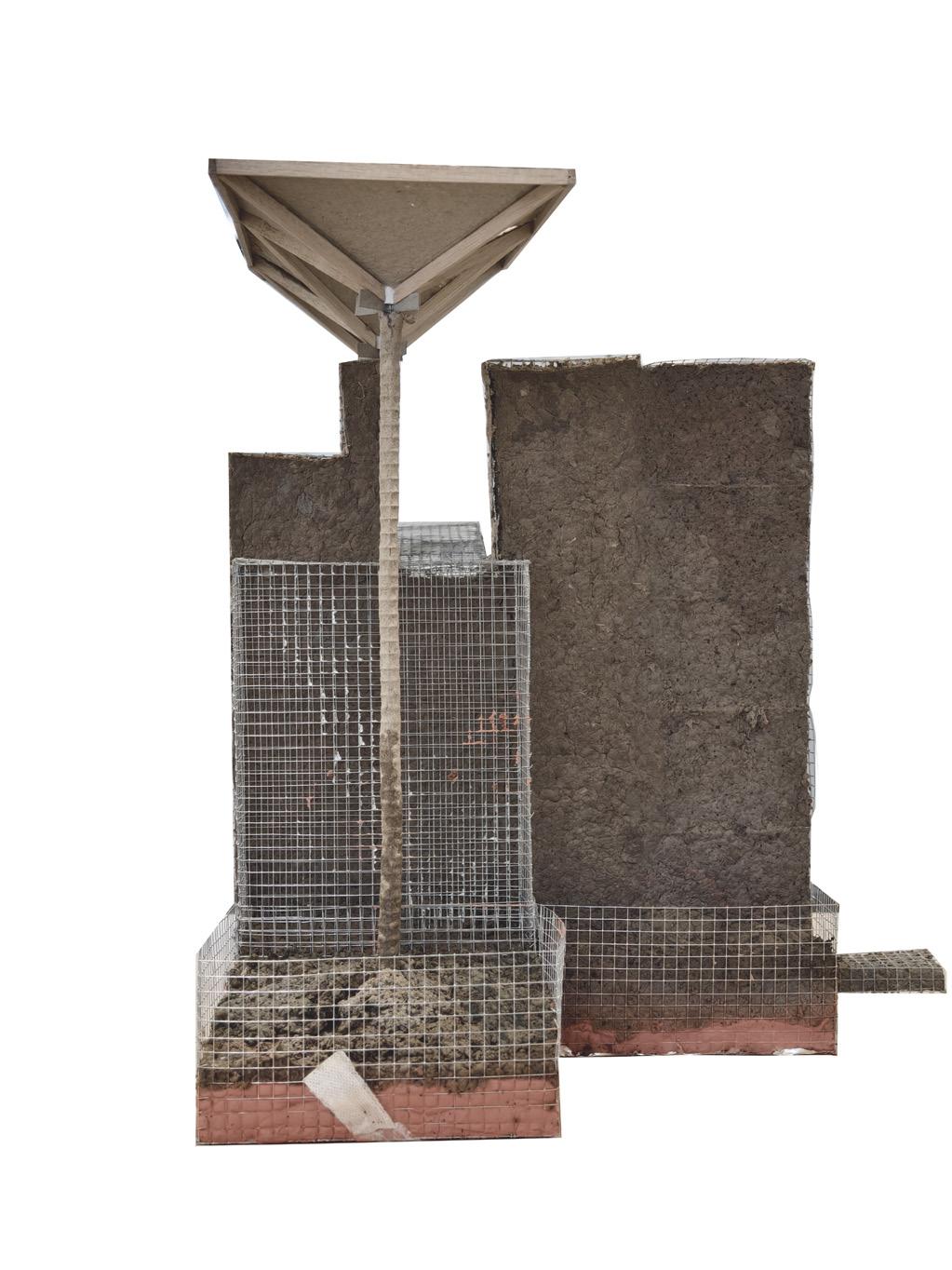

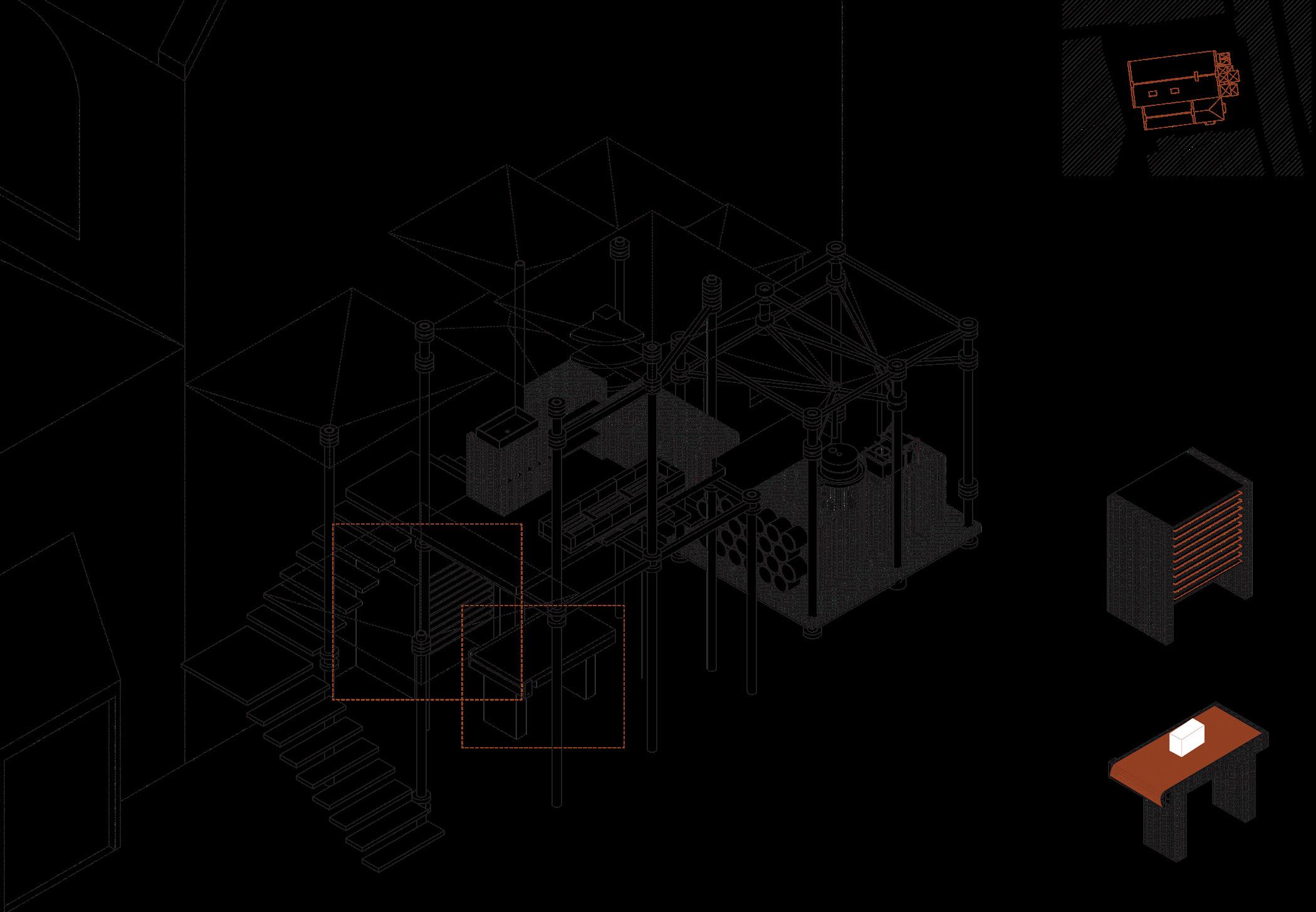

Papermill

In the second semester, we further developed the typology and brief from Semester 01, evolving it into a highly complex architectural project that functions as a support structure for a post-petroleum world.

This model is a fragment of the papermill. Using paper and steel mesh as the main material, it helped me to understand the material better especially how paper performs when used for columns and wall construction. Steel mesh is used as reinforcement which makes the structure more rigid.

Construction

The construction details of the structure was tested through the model, especiallly the connection between the canopy and the column. However, the scale of 1:20 is still too small to build the exact joint. The model partially informed the detail construction.

Fixing canopy

Fixing columns

Layering paper bricks

Setting foundation

EXPERIMENTING

Experimentation in the design process provides opportunities to explore unconventional ideas and innovative solutions. By testing different iterations, I learned from failures, which further refined and improved my responses to specific design problems. Experimentation is closely linked to the process of making, involving direct interaction with materials to understand their properties, behaviors, and potential applications.

In this section, I had the opportunity to experiment with unconventional building materials, particularly paper. This allowed me to gain knowledge about the lifecycle of the material, from production to end-oflife treatment (waste recycling). I tested the qualities of paper as three-dimensional objects and as structural elements, providing valuable insights into construction techniques. These experiments with the papermaking process also enriched my narrative of a papermaking community.

Fig.14 Experimenting with different ways of making structural elements with paper

Architectural Devices of (Un)Knowing

Printmaking Device

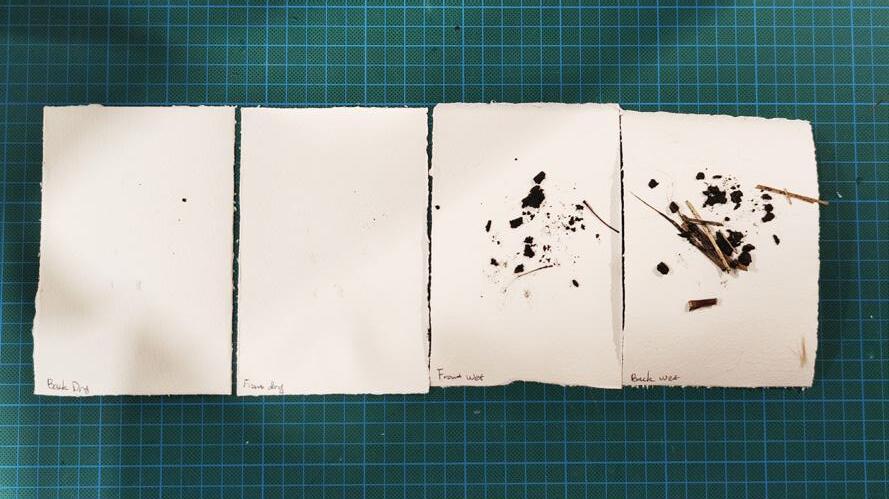

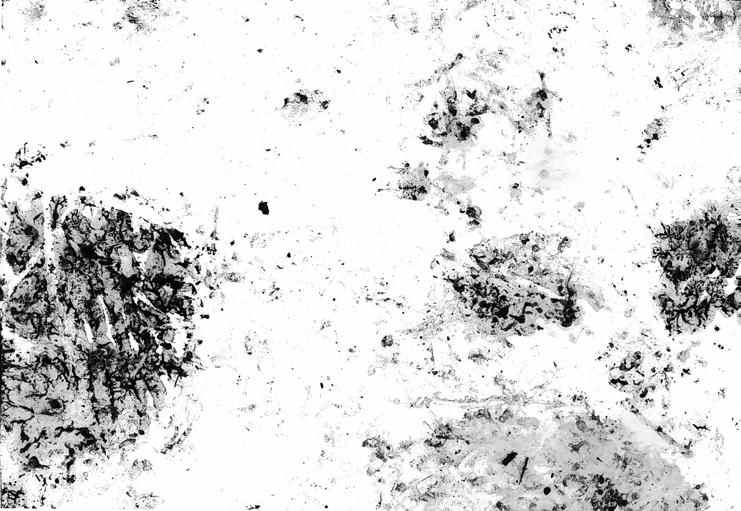

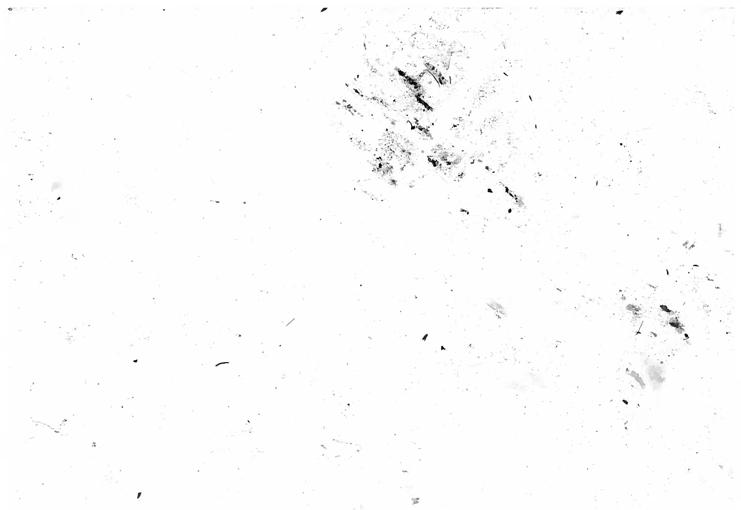

Before taking the printmaking device to the sites, several tests were conducted to find the appropriate ways of making imprints from the ground.

I tested with different types of paper, with or without damping the paper, and pressing mud directly or using inks and paints. These tests gave me the general understanding of the suitable materials of recording and the possible outcomes.

However, the experiments were made on a flat surface which led to the failure of my first printmaking device.

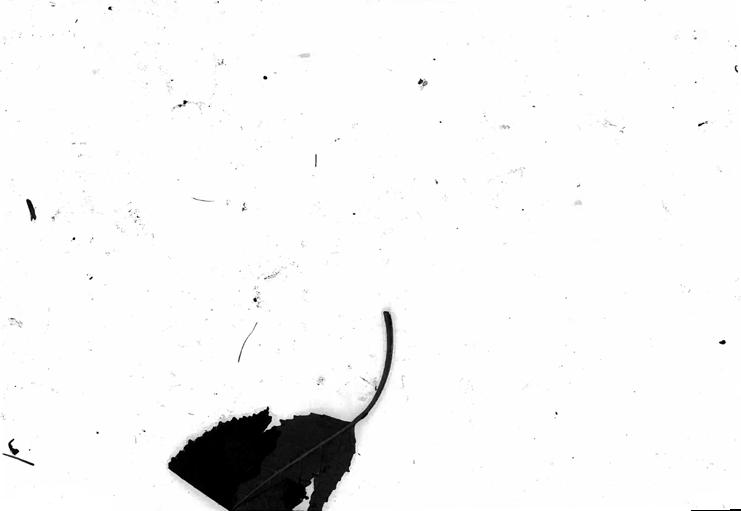

The first test of the device was during the trip to Mossmorran. I had the opportunity to make imprints on different types of surfaces. The printing result is highly dependent on the ground condition and accessibility to soil from the surface. Most of the sites we visited are covered by vegetations. The only marks left on paper are the pigments of some plants. Although it was not very obvious, the stiffness of plant vines did make different marks on paper.

After making the second interation of the device, I pressed different types of paper to the soil, trying to find the best paper for recording. From the test, I found that watercolour paper made of cotton stains the most soil particles. Damping the paper would make a large improvement. Notablly, the texture of paper itself adds another layer to the outcome.

Apart from using the device, I also tried different ways of recording. For the rubbles at the river bank, I used charcoal to scrub over the paper to recorde the texture of the hard ground. After experiencing the temporality of the sand prints, I was interested in the passive way of recording. I used the rubbles to place paper at the edge of waves. As waves washing over the paper is like a printing process with sand.

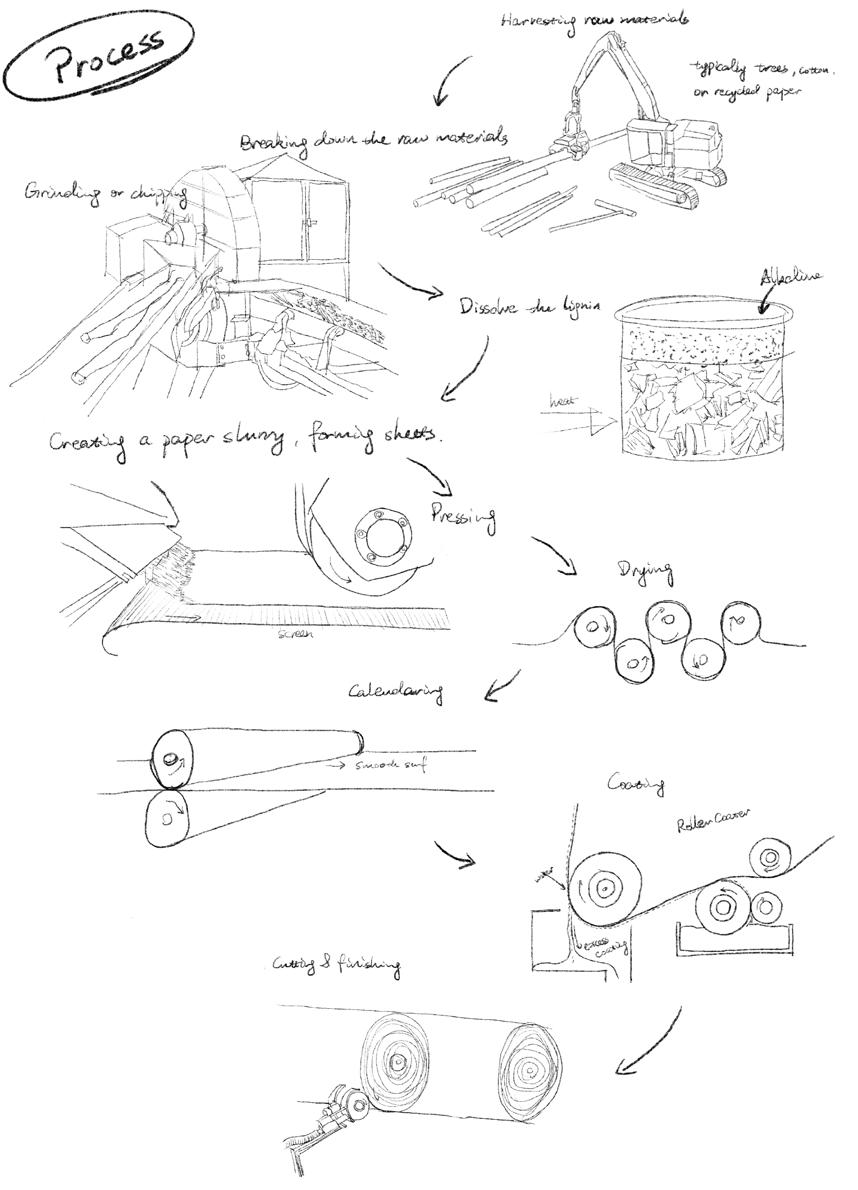

Papermaking Process

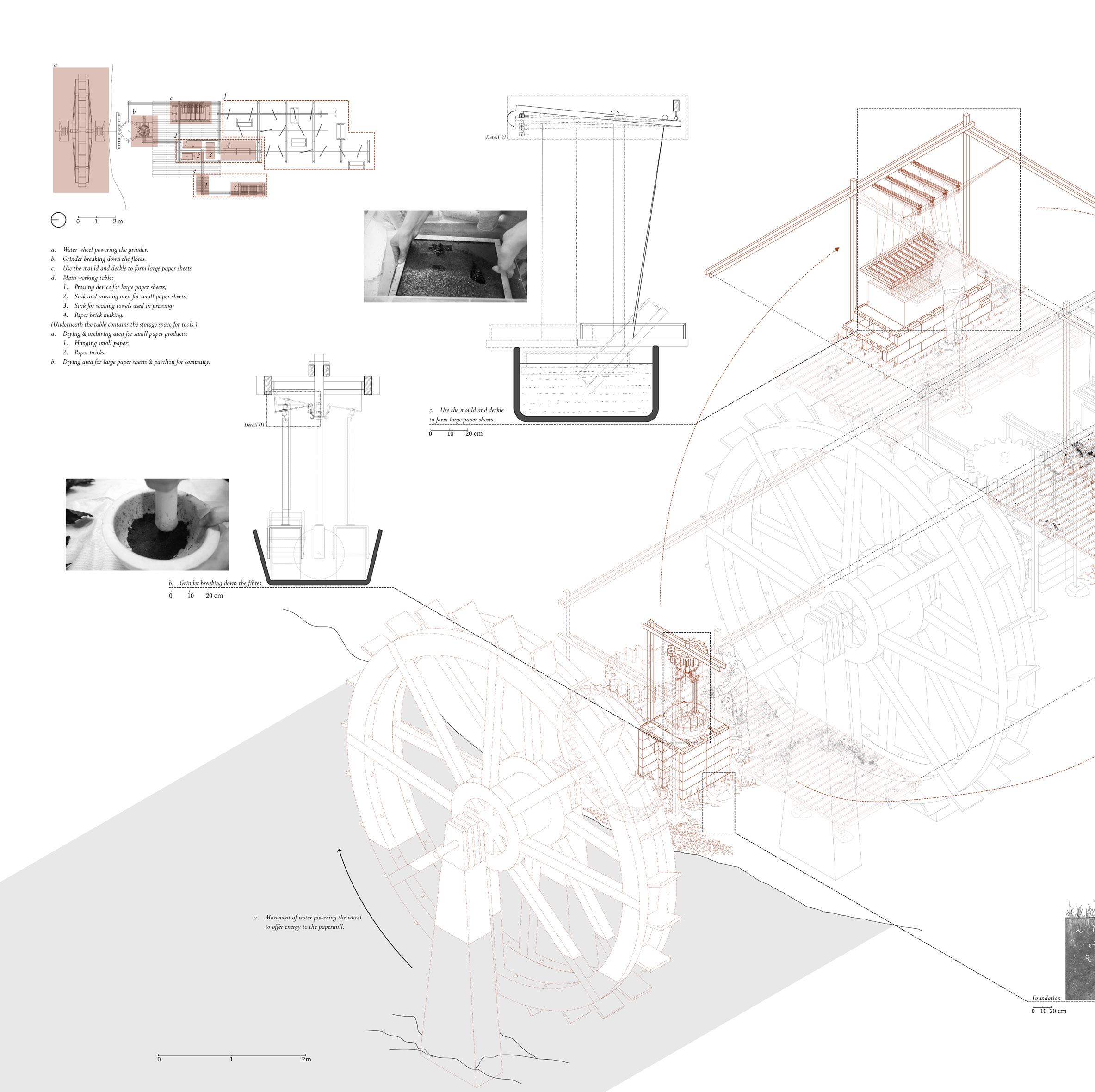

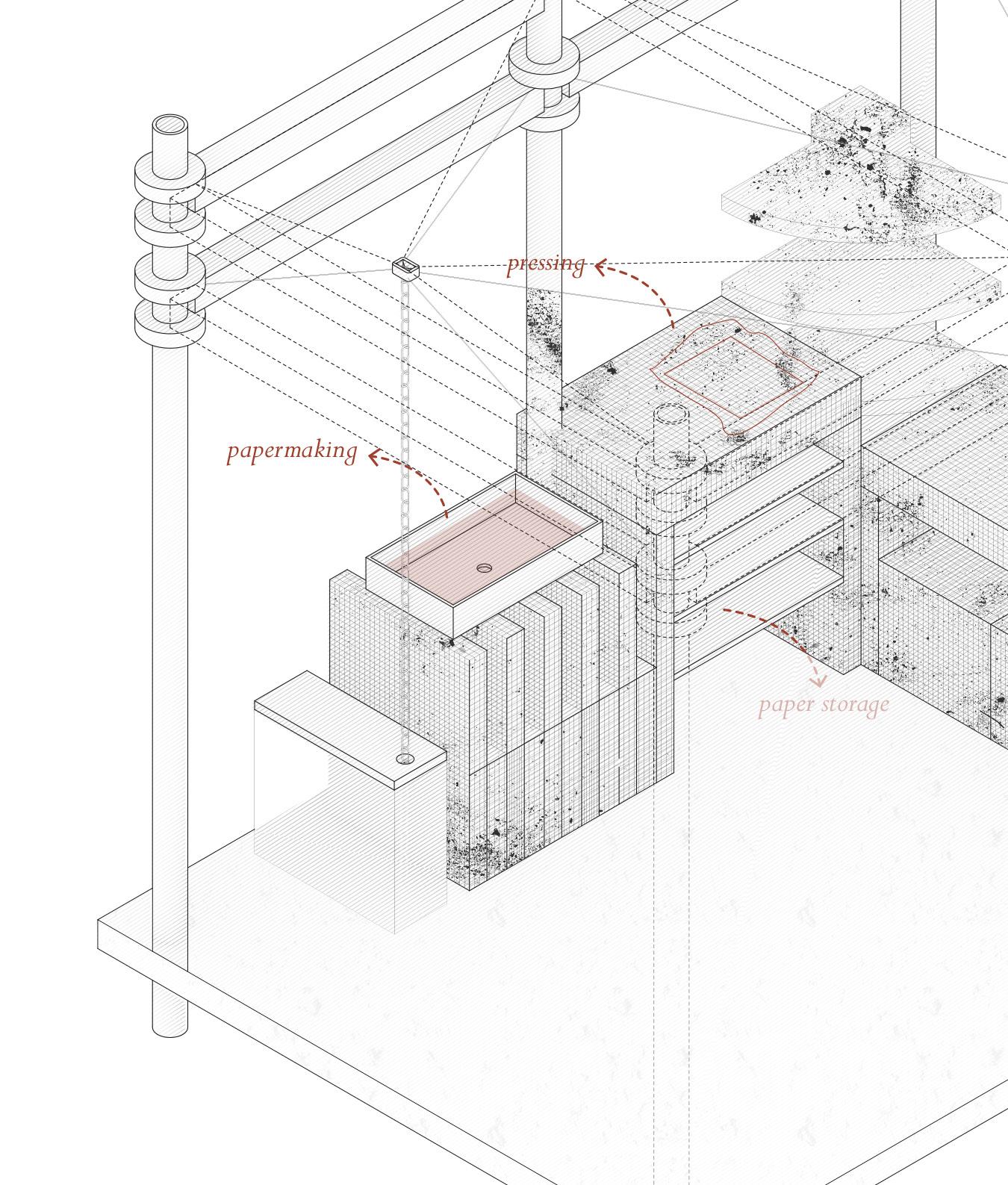

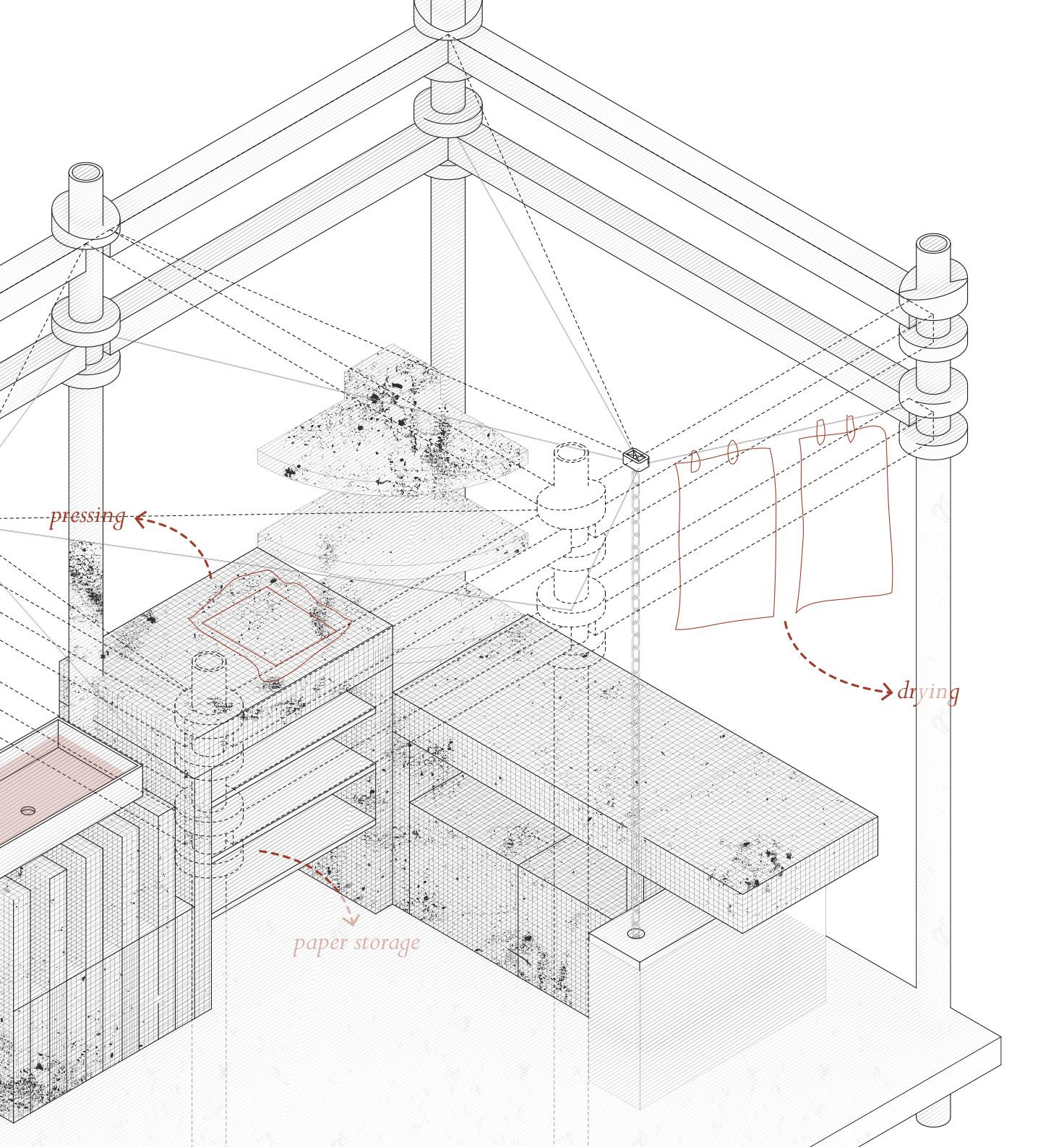

The study of papermaking process informs my design of the support structures. The papermill, in particular, engaged closely with the tools and structures used during the process. The layout of each element also follows the sequence of papermaking.

The raw material for papermaking are fibres come from both plants and recycled papers. Some straws and plant vines are collected from the sensing site in Aberdeen. I also kept a container soaking recycled papers. Every time I produce waste papers, I tear them and put them in the container. This makes the paper at the bottom soaked for longer time. It is hard to take out the paper from the bottom when the container is full. This problem then guides the idea of one of my support structures.

The flexibility of the mesh allows the structure to be fixed into any container and used domestically.

The process of tearing the waste paper also led me to the idea of recommissioning the details. For the third detail, the mangle machine is placed outside a residential building, where a paper shredder can fit in the same context. The shredder uses the rolling system to breakdown large pieces of card board for recycling.

Fibre Treatment

Cooking softens the fibres and the beating and grinding breaks them down.

This process led to the design of the first fragment of the papermill - the grinder.

The recommission detail was integrated in the support structure as the connection of the grinder. The hook attached to one end allows the stone to follow a circular movement. Its flexibility allows different amount of fibres underneath the stone. The weight of the stone breaks down the grass fibres and recycled paper.

Papermaking

Put the pulps in the water. Mix them evenly. Scoop with mould and deckel. I used the frame of failed device for the mould as an act of reusing.

Leaves are added to make new textures on the paper.

Transferring fibres onto cloth

Woring on the table top. The transferring process failed as the fibres are sticked to the mesh. I had to do it several times to transfer them onto the cotton cloth.

Pressing

I repurposed my rolling pin as a pressing tool in papermaking. It makes me realised that there are a lot of common steps between printmaking and papermaking. Papermaking is a wet process, leaving water marks on the table top which adds layers to the recording.

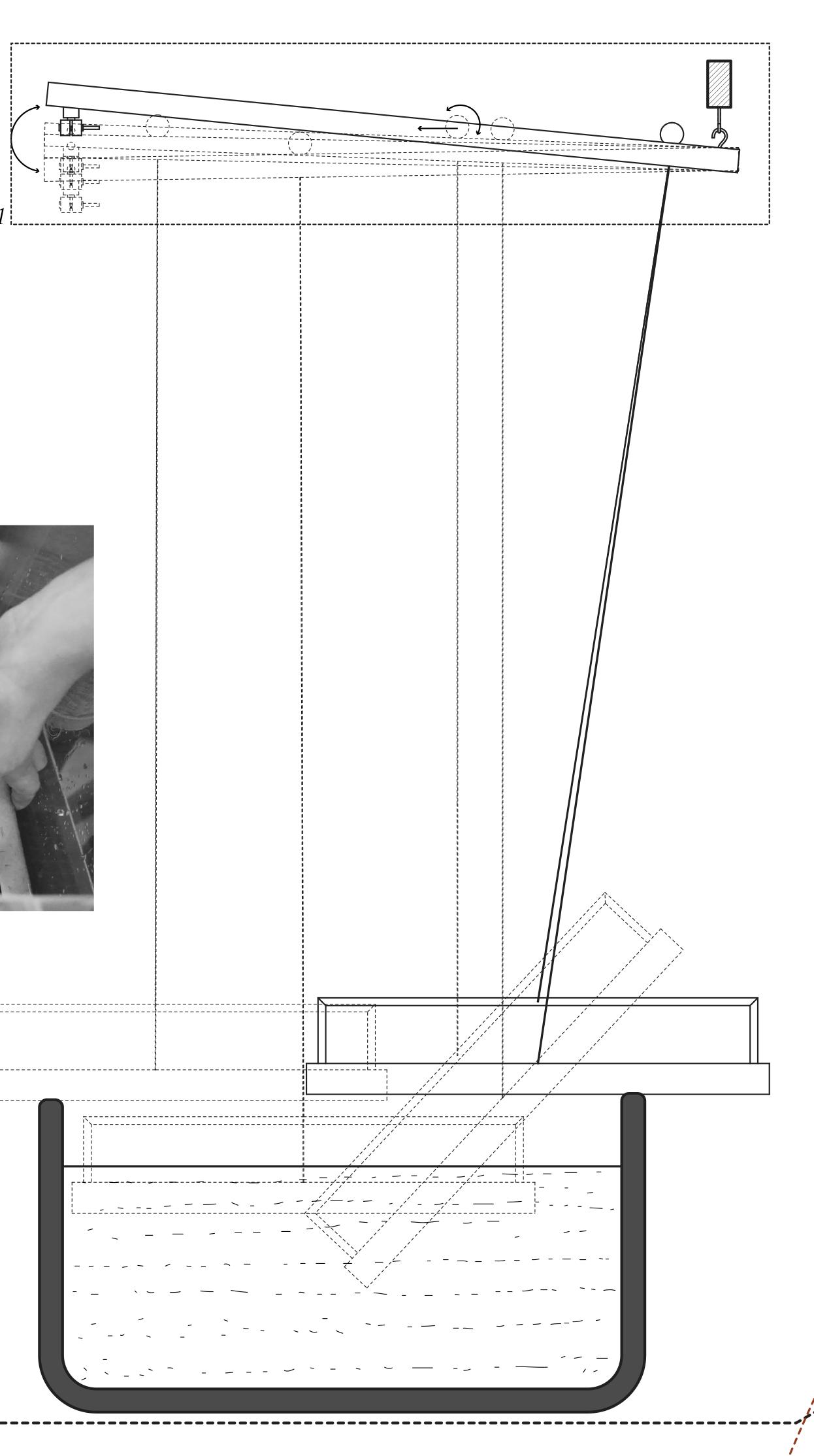

Transferring and pressing requires a flat surface which led me to the idea of a working table in the centre of the papermill. As the mechanism of the mangle machine is similar to the pressing process, the detail is repurposed in the papermill.

Drying

The cloths are then hanged for drying. How to collect or drain the water dripping from the cloth is a problem to think about.

The detail of the railway track is recommissioned as a drying rack holding large sheets of paper. The paper is hanged underneath the rack. The railing system allows movement of each sheet.The height of each sheet of paper can be adjusted individually, forming a flexible, curtained space in the papermill. The drying area is integrated to the recreational space for the community. The water dripping goes back to the ground and feeds the plants.

This was my first attempt of papermaking. From the experiments I learned the limitations of the tools and materials I use. The deckle is not thick enough to hold the pulps. I did not have enough fibres to hold one sheet of paper together. It becomes more of a printmaking process with the fibres I prepare. The patterns formed on the sheet is an unexpected outcome of the interaction with water.

I also tried turning paper into different forms. The way of shaping paper pulp is similar to shaping the clay. This becomes the starting point of making three-dimensional objects out of paper pulp.

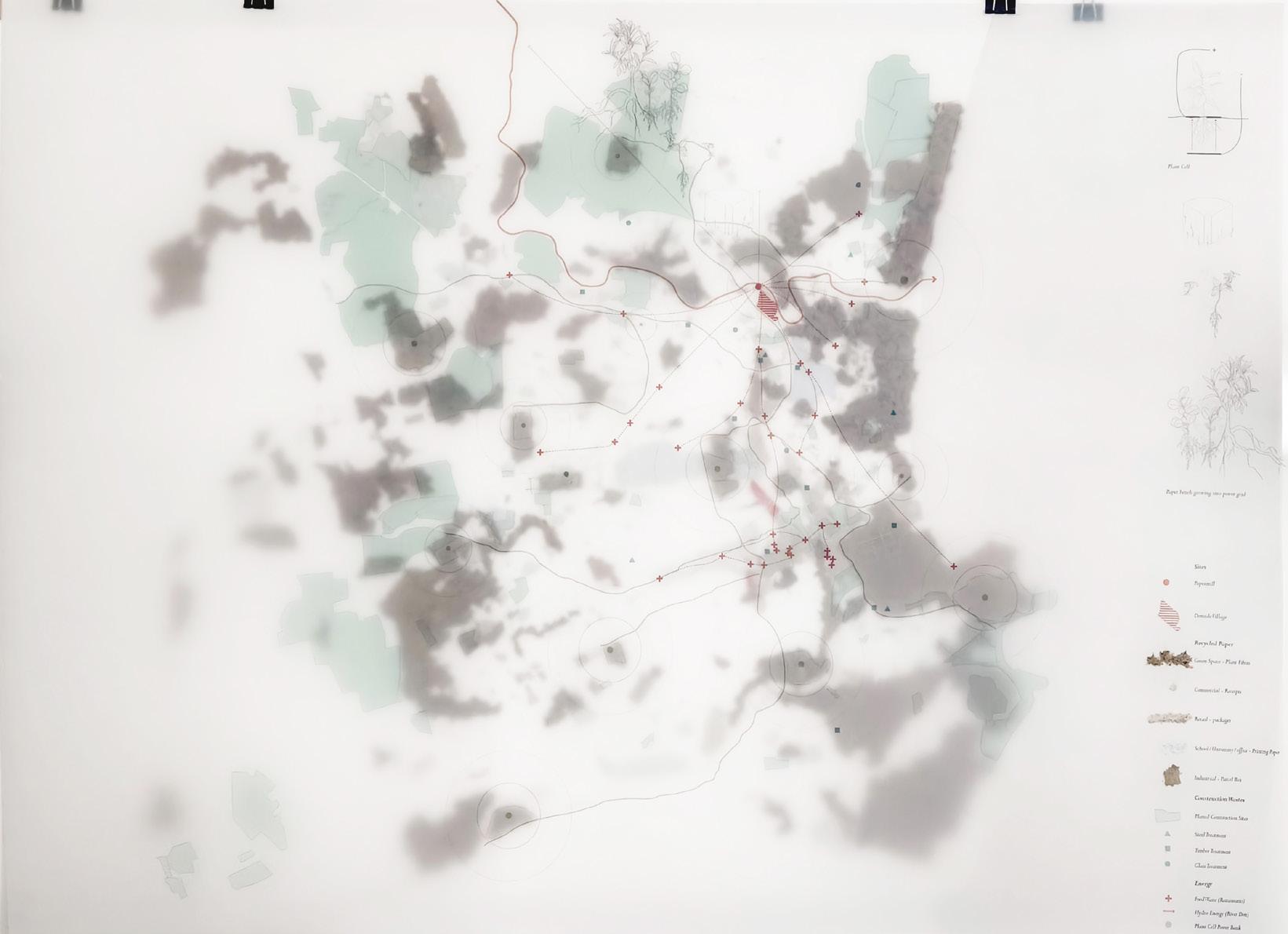

The Trio: Material, Energy and Dirt Harvest Maps

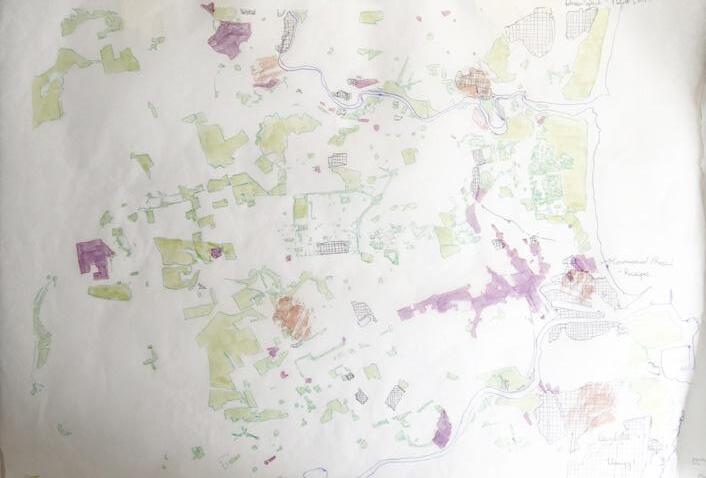

Material Map

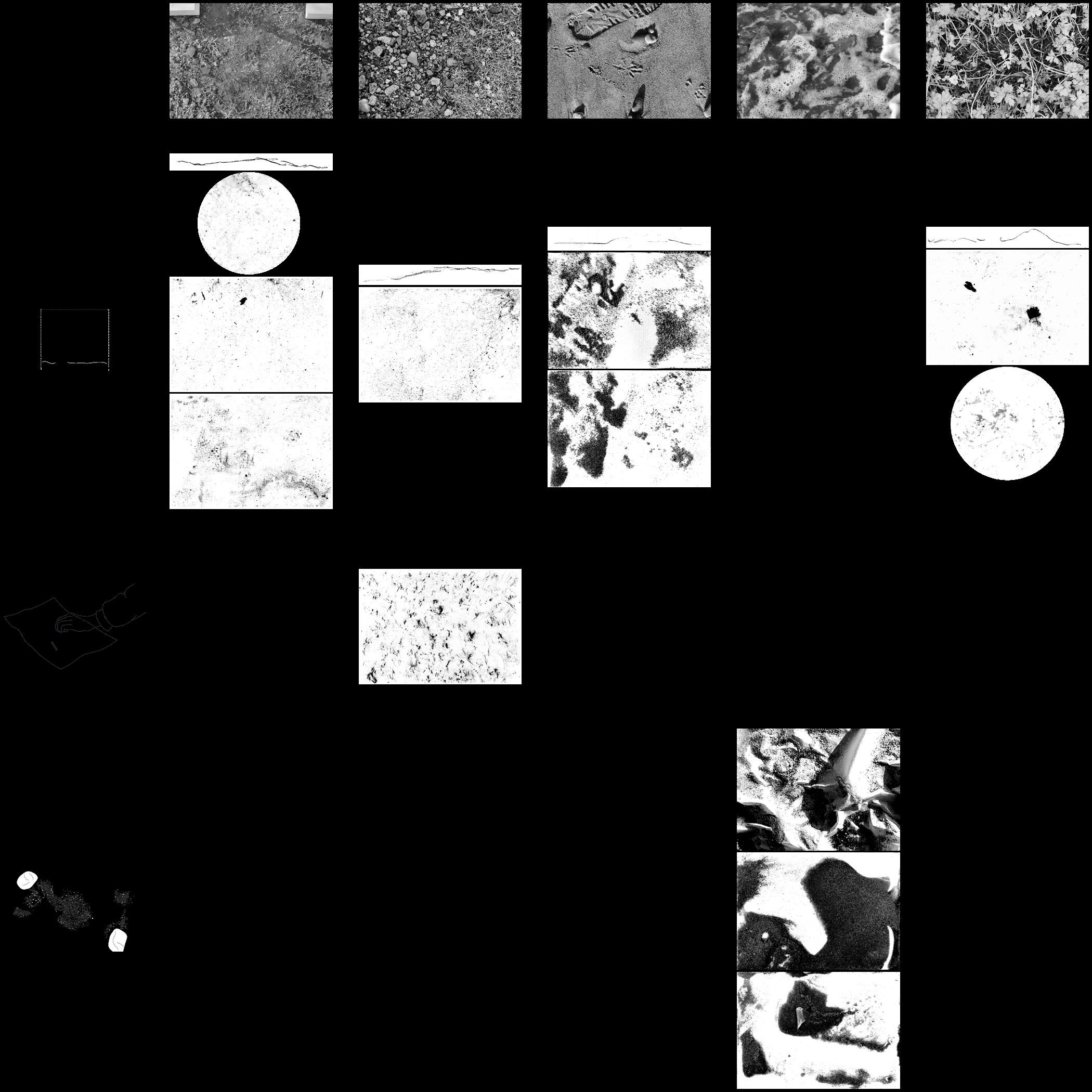

Having recycled paper as the main building material in the post-petroleum scenarios, a part of my material map becomes the source of recycled paper. I was interested in the qualities paper made from different sources. I collected different types of recycled paper and made them into pulps. Each type represents a type of landuse in Aberdeen, implying the source of the material.

Taking out the shape of each pieces was also a challenge. I printed out the shapes and removed the excessive parts when the paper was still wet. This produced fuzzy edges which impliess the obscure edges of each type of land-use in Aberdeen.

A Support Structure to Wear Experiment of Paper in Three-Dimensional Form

This task was aiming to explore support structures by examining the relationship between body, construction, details, and material. It serves as an experimental exploration to understand the dynamics of support in social, material, and political contexts. The task highlights the boundaries these structures impose on our bodies while also revealing the freedoms they enable.

I took this opportunity to experiment with paper as three-dimensional objects. In collaborarion with Maria, we used steel mesh as reinforcement to provide rigidity of the material. We tested with different moulds to form shapes, ways of pressing and the differences between solid and hollow sections.

Steel mesh works effectively as moulds as it allows excessive water to drain. Different shapes can be formed bending the mesh. This process informed us the logistics behind the making which further helped to make my design more practical.

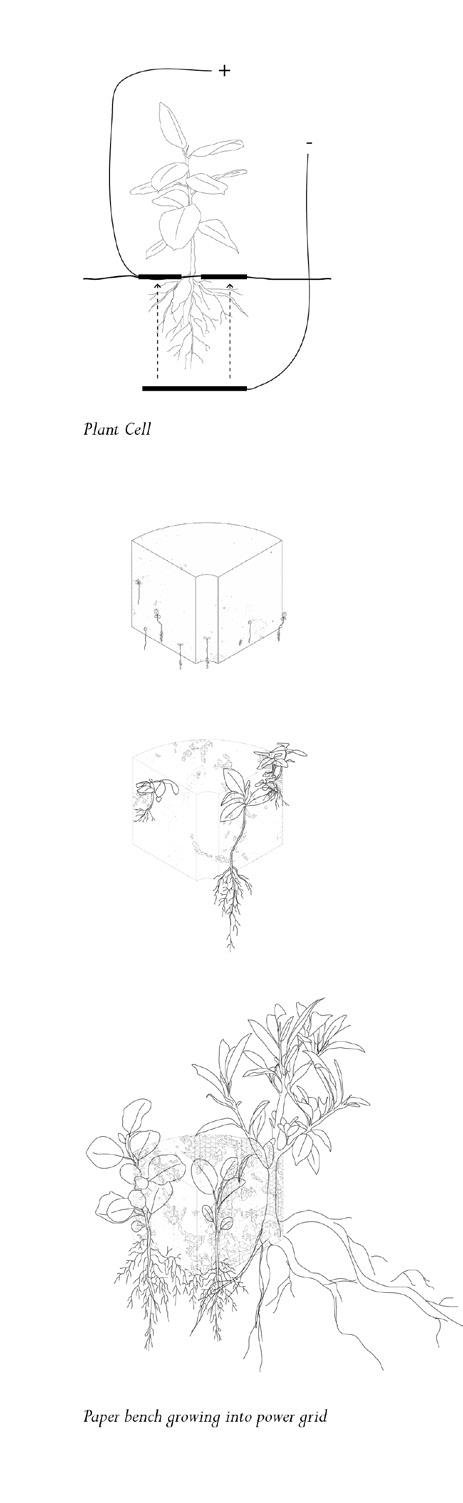

Our support structure is a small bench. The initial idea is to integrate it with the energy grid of the city. (The energy system involves plant cells which will be mensioned later in mapping and stroytelling sections)

We made two modules of the bench and tested the stability of different ways of stacking. Due to limited materials when making the benches, the form is not solid enough for supporting human weight.

The structural performence of other forms was also tested.

Notablly, the forms we made initially are not planned. After the objects dried we tried to assemble them in different ways and received unexpected results. This opens up huge potentials and opportunities for paper being the main material of furnitures and appliances for further research.

Support Structure to Wear

Experiment with Seeds

Thinking about the plant cells, I was trying to integrate paper and the energy system. For the damp condition during paper production, I imagined that paper could also become a habitat for growing seeds. As the paper breaks down gradually and goes back to the ground the seeds mixed within the pulp start to grow and become a part of the energy system.

I selected several lemon seeds and put them into the paper pot. The test failed when the paper starts to dry.

MAPPING

Mapping as a design tool provides a clear visual representation of spatial and locational relationships. It offers new interpretations of existing information. By integrating various information, mapping reveals patterns and connections that may not be immediately apparent. From the imprints of the ground to the material and energy system, the mapping exercises serve as powerful storytelling tools. Maps in this section does not limit to the geographical information. They offer different lenses to contextual information including history, culture and dynamics of the place which helped to form a comprehensive narrative in the post-petroleum scenarios.

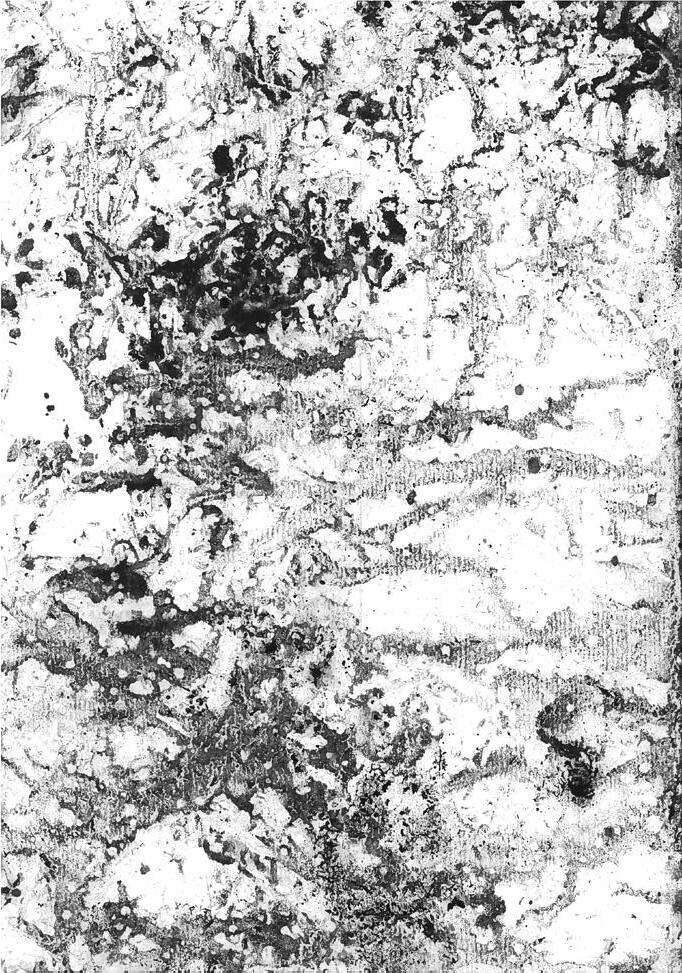

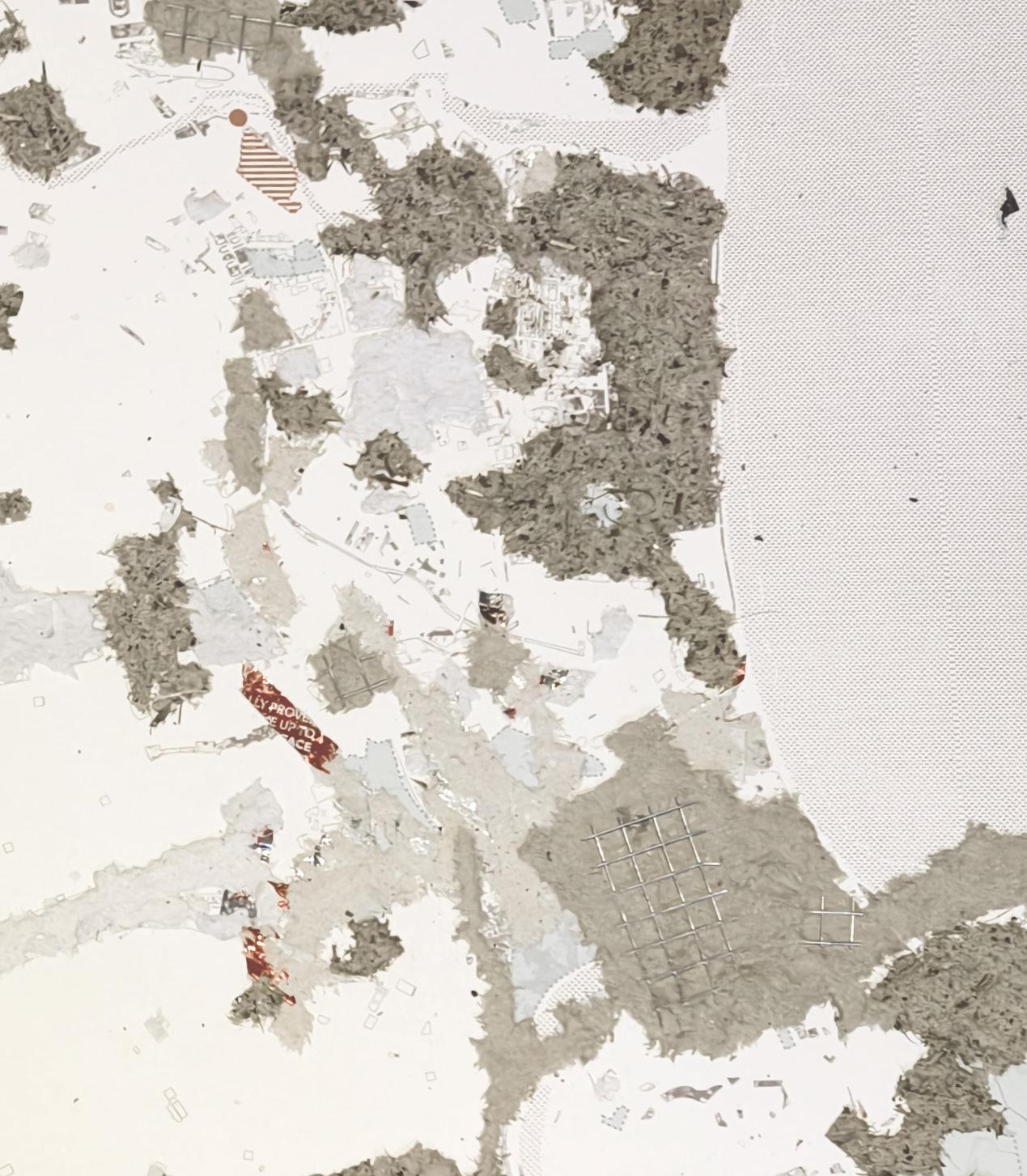

The sensing map of Mossmorran trip recorded different ground textures through the imprints I gathered from the sites. I mapped out only the type of ground we investigated on the day. The imprints are not to scale but has an implication of the site consitions and the activities I took on the site.

The Aberdeen sensing map applied same techniques but with a smaller scale and greater range as the Mossmorran Map. The imprints represented the green space in the city, drawing attention to the muddy ground which is often neglected.

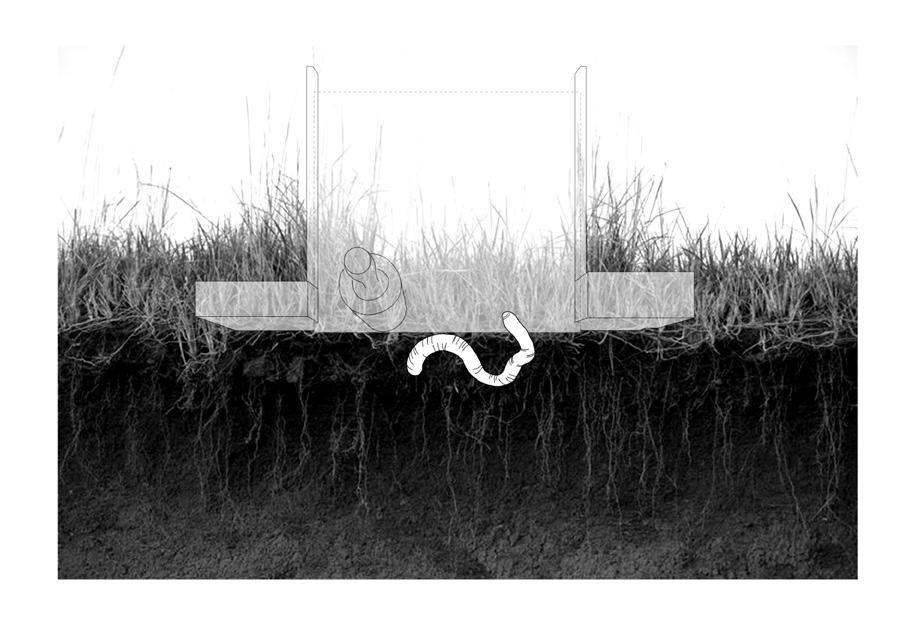

Constructing the Ground Thick Section

Group section with Harry Monaghan, Mari Helland, and Maria Perez Caballer Baeza

The thick section concept involves creating a dense, detailed representa tion of the site that highlights multiple relationships and adjacencies through micro-analysis of the area of interest of ours. Focusing on the muddy ground, this task combines the materiality and artifacts collected into a sectional drawing of specific parts of the site.

We started the thick section by collect ing the outcomes of our devices and situating them on the Aberdeen map. We imagined the mesh as a worm hole and the section is looking from below the ground through the hole. Then we added our individual fragments on the section, protruding and breaking the circular form. The section is thickened by cutting out the worm hole and stitch the mesh on with objects collected from the sites.

The layering of information as a mapping technique in the sectional drawing offers a new perspective into my narrative.

sketches of devices tracing over the textures objects collected from sites (view through the worm hole)

Constructing the Ground

Donside Paper Mill, the first paper mill in Aberdeen, initially served as a corn mill and woollen mill, forming a cluster of mills. After its shutdown in 2001, the buildings were quickly demolished. Excavation for the urban village development in 2013 uncovered rubble, stones, demolition materials, and cinders buried underground, adding layers to its historical narrative.

modern rubbles on compact clay soil

mill lade (small water channel)

large stone and demolition material

paper mill

Dumped ash & cinder from paper mill

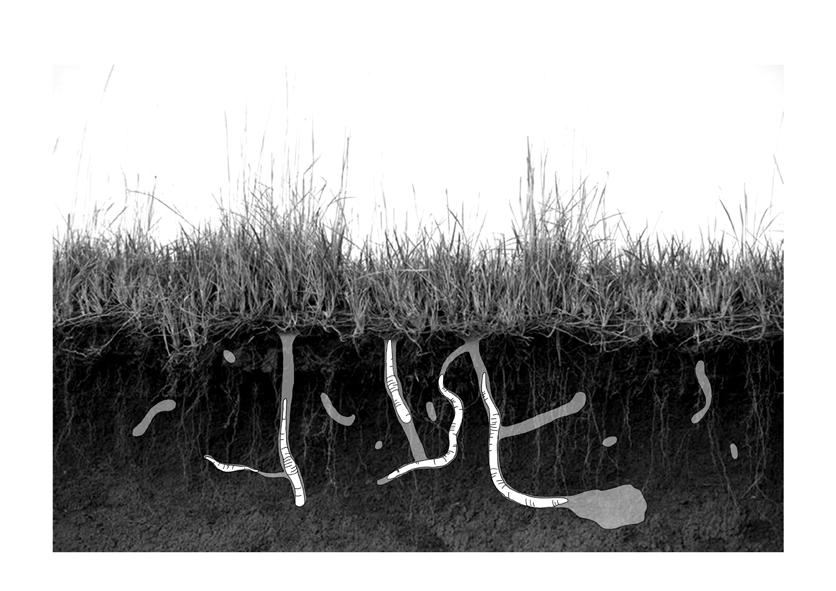

My individual section speculates the layers underneath Donside. The history around the paper mill adds layer by layer on to each other and forms the ground in current state which will be covered by new layers. Underneath the vegetation is the stones and rubbles, demolition materials, cinders and mill lades. When the earthworm burrow through, it spreads and mixes the layers of history from underneath the ground.

f. Current Ground Ecologies: Roads, Tree Roots, Earthworms

e. Mill Lade (small water channel powering the mill) with Demolition materials

d. Dumping of Building Materials and Rubbish

c. Dumped Ash and Cinders form Paper Mill

a. Compactt Clay Soil (The original state of the ground)

The Trio: Material, Energy and Dirt Harvest Maps

Each material’s journey leaves marks on landscapes, infrastructure, and the lives of those involved in its production, serving as archives of our economy, politics, and history. This task aims to develop an ecological awareness of the interconnected relationships between humans, nonhumans, environments, and objects. It encourages the consideration of the materials around the site and view architecture as a responsible contributor to the local environment. This exercise led me to think about the origins, life-cycle, production, and disposal of every material choice.

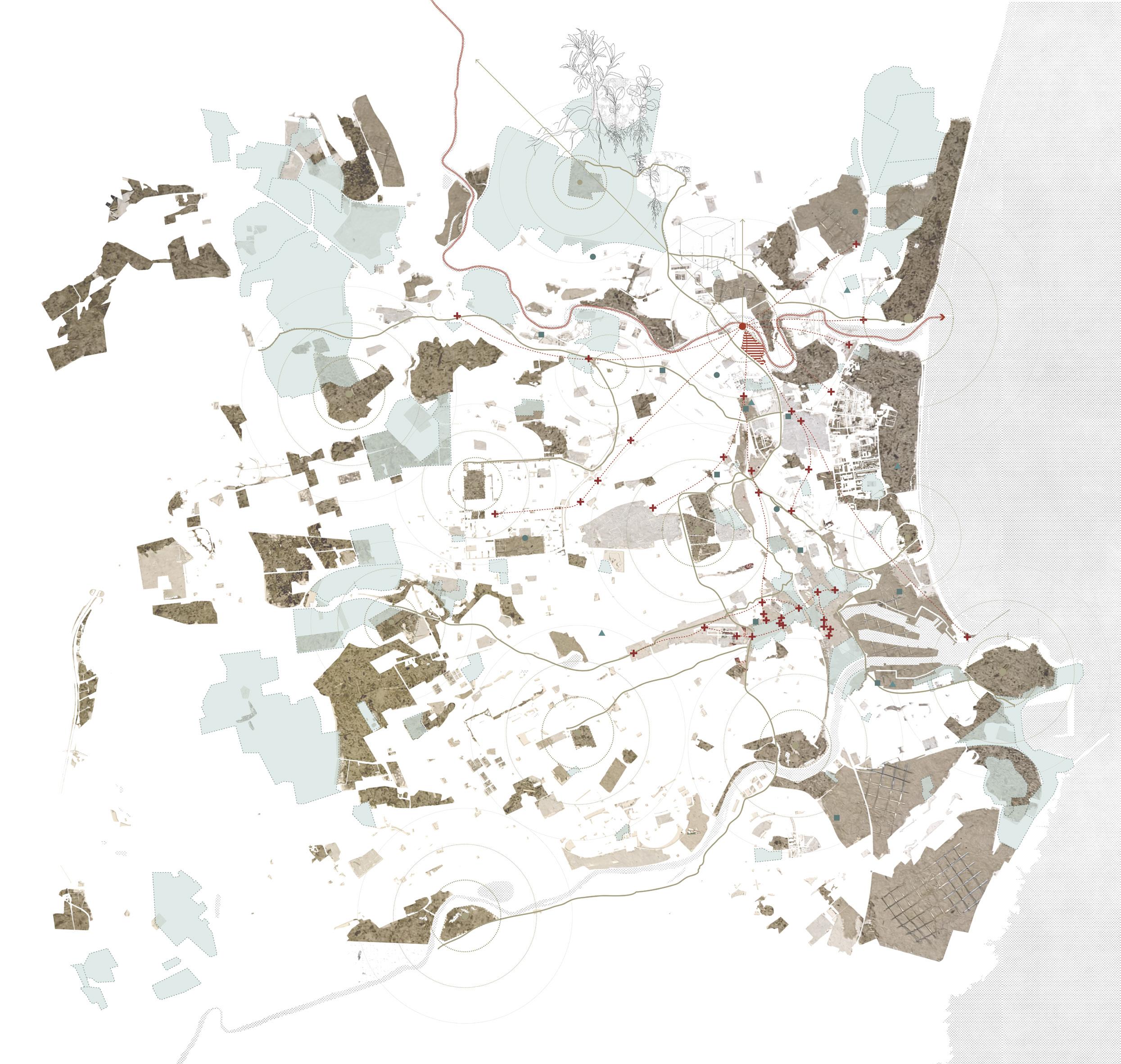

Having paper as my main material, I started by mapping out the source of recycled paper. The land use of Aberdeen was reinterpreted as the source of different types of raw materials for papermaking: green space - plant fibres, industrial area - parcel boxes, commercial and retail area - receipts and packaging, and office and schools - printing paper. I also located the landfill sites in Aberdeen and their impact on surrounding area. Other materials are complemented by the construction wastes collected from the excavation and wastes from construction sites planned in the future.

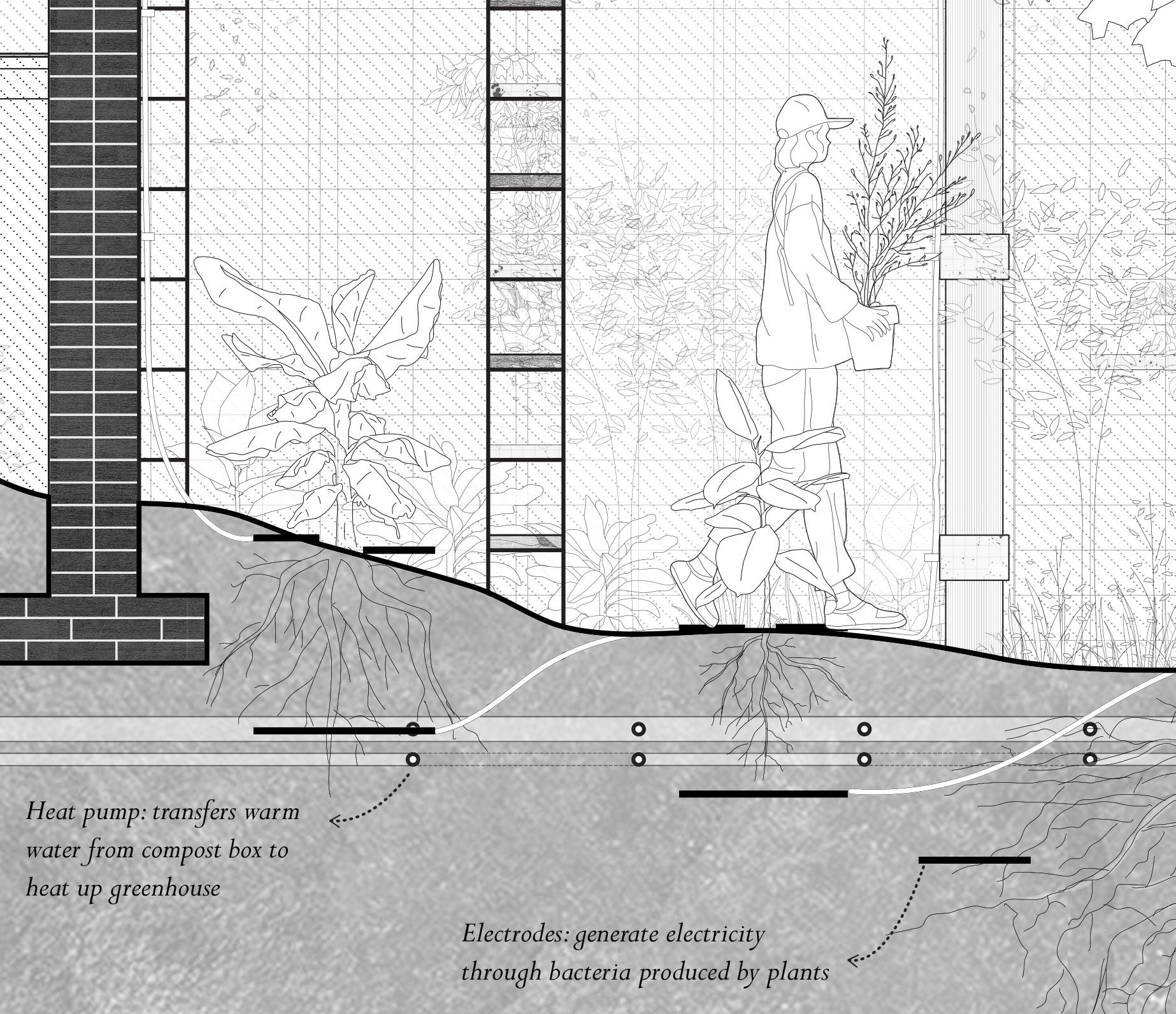

My initial idea for the energy system is to use the hydro power from River Don and the compost energy from food waste which relates to my narrative. The mapping of green space led me to the idea of integrating the energy system with the material system. The idea of plant cells fits into the narrative. The bacteria in the soil gains nutrition from growing plants and releases electrons to produce electricity. The plants become both raw materials for papermaking and a part of the energy system. When decomposed, they give back nutritions to the ground.

The wastes produced in this process would become the materials again and be integrated in the energy system. The map then presents the full cycle of the material, energy, waste system.

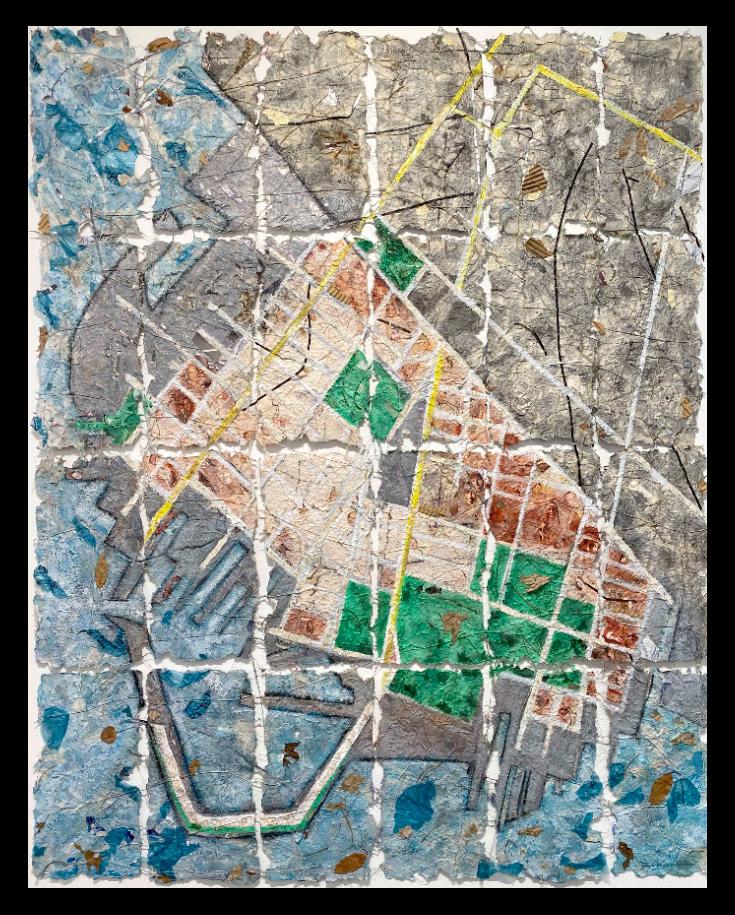

Allen's 'site maps' are documents of visits to diverse places, made entirely from materials collected on site. This gives me the idea of making the maps with recycled paper.

Jane Ingram Allen, Red Hook Site Map I, 2003, Collage and painting on handmade paper with leaves and discarded materials collected from the streets of Red Hook. Kentler International Drawing Space, https://www.kentlergallery.org/ Detail/exhibitions/238.

Jane Ingram Allen, Red Hook Site Map I, 2003The energy generated by the plant itself leads me to the idea of integrating plants in the energy grid.

Ermi van Oers, Living Light Lamp. A mood light which generates its electrical supply via photosynthesis. Living Light, https://livinglight.info/.

Ermi van Oers, Living Light Lamp

STORYTELLING

Storytelling as a design method is essential in this project. This project is guided by the narrative which builds a connection between the fiction and the reality. Fiction is not opposed to reality but rather reframes it, acting as a light or lens to reinterpret the real. Fictional worlds can be realized through precision and immersion, with rigorously imagined details, materiality, temporality, and characters. This approach allows for the integration of various fields with architecture, developing new modes of (un)knowing in the context of Aberdeen. By building up stories for characters, I found the motivations for each design decision which further builds up the narrative.

Concept Tool Box A Collective Landscape

This task aims to connect theory and practice, viewing theory as a form of practice. By critically reading and discussing key texts, we create a concept-toolbox which help us navigate towards a post-petroleum era and take a collective social and political stance against exploitative petroleum industry practices. The reflection inspired me with the collective way of storytelling. It helped me to find the basis of my design narrative of the communal collaboration and gave me the idea of have earthworm as one of my main characters.

In Architectural Storytelling, Isabelle Doucet discusses the role of storytelling and its challenges in design process. The second section “Storytelling as a Critical Design Tool” starts with a discussion in “Utopiyang” (a world that is manicured and controlled) and “Utopiyin” (a world that accepts imperfections and uncertainties).1 (39) Rethinking about my device and the unexpected outcome of the print, I realised that the loss of information itself is a response from nature. The imprints are dependent on the weather, the soil particles and water contained in the soil. What story is the ground telling me? Do the soil particles caught by the paper form a new landscape in the micro world?

The discussion then leads to a collective way of storytelling, focusing on the “conversation” between humans and nonhumans. A “Utopiyin” in this context represents a world that transforms itself instead of controlled by architects:

Asking how architectural stories can become more “utopiyin” therefore means to ask how they can thrive on the collective voices of humans and nonhumans, how they can “brew” rather than “author,” and how they might nurture collective rather than individual world-making. (42)

The thinking regarding control and manipulation continues. How do we define the boundary of human interventions? Realising the nonhuman species also involve in the process of world-making helps me understand the idea of “brewing”. In the context of mud, the life inside the ground forms a micro world usually ignored by humans. They grow, bear new life, die, decompose, and become part of the earth and nutrition. What marks do they leave?2 These marks are unpredictable elements in the

1 This is an interesting perspective because architects are usually the one “controlling” the environment by design means.

2 It is something the prints was trying to collect but failed during the trip. I realised that time is essential in

imaginary world we are building. They are expected to be out of control. Could the unexpected results become the proof of the collective world? Going back to the question regarding to human intervention, if I provide habitats for these creatures in a project, am I trying to define their way of living or propose on behalf of the nature? If I use them as a resource in a way that they still live their life cycle and decompose after fulfilling their tasks, is this still an act of exploitation and colonization?

Not only the life in the ground is usually neglected in the narrative, Doucet argues that architects tend to hide the messiness and complexity of their stories. (45) She also points out the importance of the messiness: […] a wonderful celebration of messiness considered not as a threat but rather as an opportunity that allows architecture to remain situated in the “real world” – composed of “people, time, politics, ethics, mess” – on which it always depends. (45)

The messiness makes people aware of the influence of industrial activities while holding the products we are using and being sheltered in the buildings. Linking to the history of paper industry, the development of technology is an increasing exploitation of various sources of energy. From human and animal force to water mills to fossil fuel powered factories, the tools (or machines) of papermaking evolves from small-scale handmaking to mass production. The messiness of production becomes hidden and inaccessible. Is there a way to engage consumers in the process of production? By close contact with the ground and the messiness of production, is it possible to create a new set of tools for paper and print making? Link back to the collective world, handmaking process is slow but unique with the involvement of nonhuman life in the nature and their unpredictable traces. This act is contradictory with the precision and time efficiency of mass production in today’s world. Here, I wonder, is mass production still necessary in a post-petroleum world? this “brewing” process. A quick pressing activity is not enough to gather such information.

Characterisation

This task encourages the consideration of inhabitation as a key element in the architectural design process. By focusing on characterisation, we recognise and consider all individuals involved in the planning, construction, and use of our architectural concepts. Additionally, we aim to highlight the impact our proposals will have on the broader community and identify those affected by our design choices.

An earthworm and a mud engineer is my two main characters. They become my lenses to understand the site and having conversations with people in the story. They offer two distinct perspectives which forms a collective way of storytelling. I tried to write diaries from their perspectives, it helps me look closely and stick to the narrative. I ended up with two of the diaries as the beginning of this story.

Earthworm

The earthworm burrow through the ground. It eats soil particles during the process. This earthworm gains knowledge and memories of the particles it consumes. The adventure begins.

In the land of Donside, it witnessed the story of the cinder from the paper mill, the conversations between a brick of the paper mill and the father of the mud engineer, the daily life of Donside residents... It learns the history of the land gradually. Then it met the mud engineer wishing to record the history of the land.

In the home the engineer built for it, it started to pass on the knowledge through the nutrition it produces for the plants living in the soil. The engineer says these plants will be made into paper, displaying the memory of the land. The earthworm feels satisfied. This is the way it tells a story.

Paper mill 1944-1972

Ashes and cinders from the mill

First day I am born.

This is the first day of my life.

I am ignorance about the world, yet I posses the memory of my ancestors. The only problem is that I have not learnt how to acquire those memories. I sense the moisture around me. Slightly uncomfortable. I move my body slightly, trying to get more moisture from the earth. I open my mouth. Some images start to form in my head:

Dancing, dancing, falling… I see a large cylinder moving away from me. No, I am moving away from it. I am travelling with a stream of small fibres. Water surrounds me.

I’m drowning! I try to scream. Suddenly, I find myself still deep in the soil safely. It was a dream! Yet the scene was too real!

I take a deep breath and open my mouth again:

I ended up on a ‘screen’ (I overheard someone call it this name). The water is going away. (What a relief!) There comes another cylinder. Suddenly, I feel squeezed with others. I can’t breathe!

I struggle to escape.

Then, the warm air surrounds me. I cannot stay conscious any longer.

Something is itching. I wake up. I feel something sharp is scratching. I lost the bond with others. Dancing, dancing, falling...

I find it strange. Everytime I eat, I dream at the same time. Where do these dreams come from? Are they memories?

Mud Engineer

He used to work in an oil rig. After he lost his job, he went home and found his belated father’s diaries. His father worked in the Donside Paper Mill and was very attached to it. After the shut down of the mill in 2001, the family lost a source of income which drives him to work in an oil rig. Worked so closely with mud, he never looked closely at its natural state.

Trying to remember more about his father, the engineer started to follow the steps in the notes and experiment with papermak-

I found a wooden box of dad’s. It has been in the corner of the study for quite a long time. I never knew what was inside. Today is the day to open it. The box is full of his notes and diaries. Dated from 1960s to 2010s. Something urges me to open one of them. I want to know more about him:

15.09.1967

I find papermaking fascinating. It transforms plant fibres into the versatile material we use in countless ways. After first week of the new job experience, I still feel excited.

They are introducing a new blade coater today. They say it will increase the production and quality of paper by a large rate. It seems that the blade applies coating more evenly than the roller as it scrapes away the excess coating.

There is still a lot to learn here. My supervisor says I can learn about the chemicals in the pulping process next week. I am already fully prepared.

I keep flipping through the pages. His notes on paper making process was very interesting. I remember his excitement when talking about his job. This is the first time I am actually learning from his past, trying to capture something familiar.

ing. By puting together paper and mud, he discovered fascinating ways of recording the ground.

He encountered an earthworm one day during his recording. After a conversation he realised how much history was buried underneath the ground. He decided to take the earthworm’s advice and build a worm box for it. There are memories hidden in the paper made by these plants. Just look closely.

Typologies Collage

This task enables the vision of a post-petroleum world in a realistic and practical way using architectural concepts. It leads to questions of the existing political and cultural norms of our oil-reliant society by considering the necessary spaces we need and how we can construct and inhabit them. By making collages, the narrative of the project finally took its shape.

My collage tells the story of the encounters of the engineer and the earthworm. They were initially two sides of the world but brought together by papermaking. The papermaking can be a circular process. Sheets are formed from treating fibre to drying. They can then be used for printing and marking, becoming an archive for the memories of the ground. The earthworm act as an element for decomposing. The paper gradually breaks down and return to the ground. The earthworm consumes and produces nutritions for plants which will then be made into paper.

Three typologies strated to emerge: paper making, paper recycling, and worm box.

Urban Forager

Gather raw materials like branches, leaves, and other natural fibers from urban green spaces, as well as coordinating recycled paper collection from various industries.

Plant Cell Energy Specialist

Cultivate and manage plant cells to produce electricity, integrating these systems into the overall energy grid of the papermill and community.

Plant Cell Distributor

Oversee the production, storage, and distribution of plant cells to various locations.

Worm Box Manager

Oversees the use of worm boxes to generate heat for the energy system and produce fertiliser from food waste.

Domestic Papermaking Consultant

Help households set up small-scale papermaking facilities, offering guidance on equipment, techniques, and best practices.

Communal Papermill Coordinator

Oversees the operations of the communal papermill, coordinating the production of various paper products and facilitating workshops.

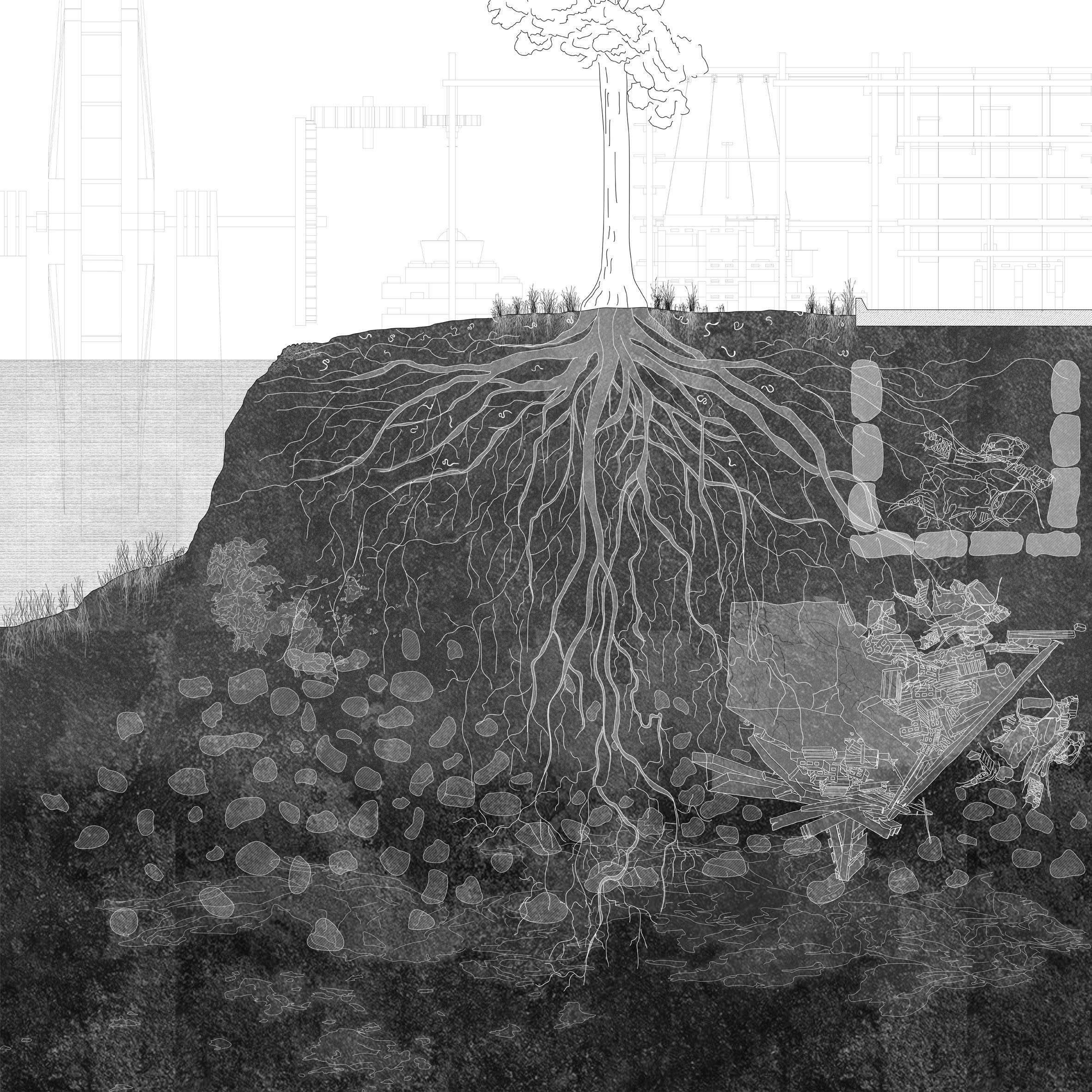

SEQUENCES

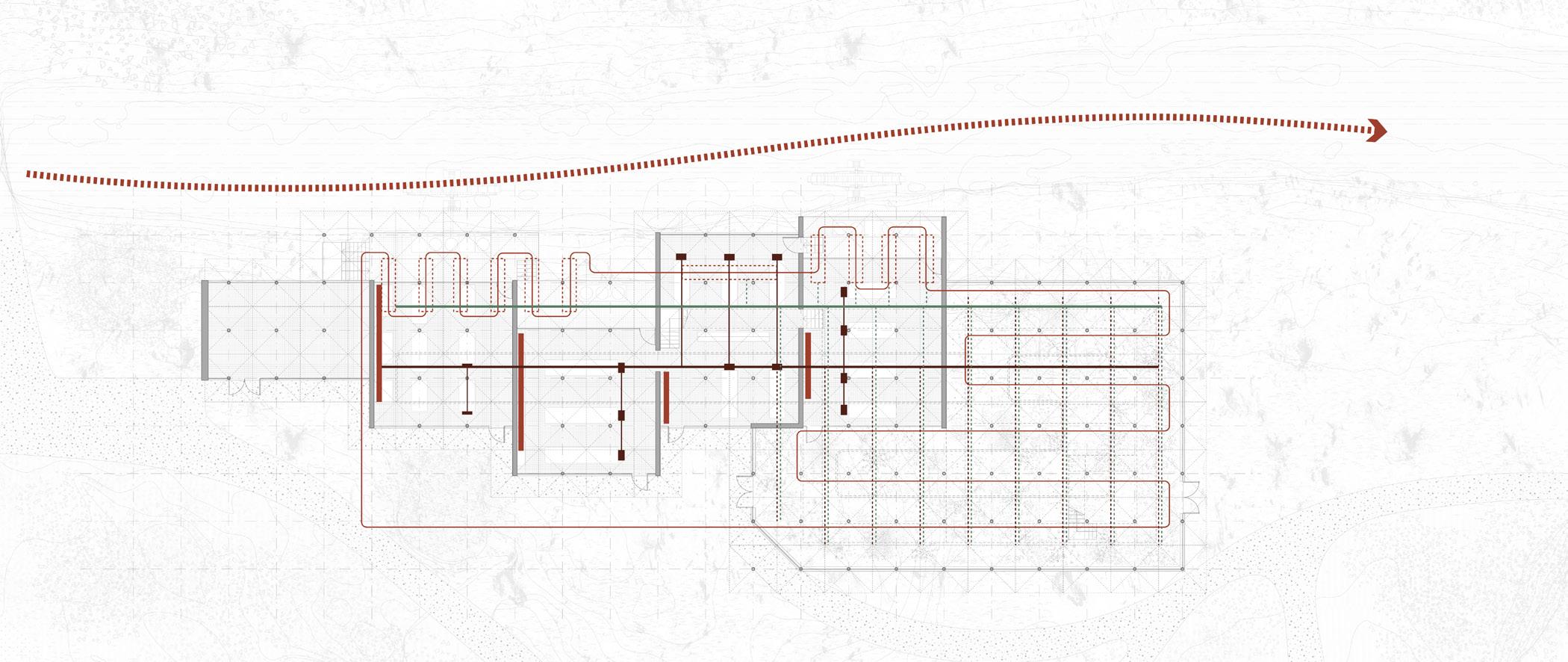

The project involves designs across multiple scales which construct a sequence of development in the post-petroleum world. The process of collective making starts from domestic space, where individuals engage in small-scale, hands-on creation. These initial activities provide the basis for larger scale production within the community. As the crafting progresses, the collective efforts expand beyond individual homes to communal collaboration and finally spreads to different industries across the city.

Following the logistics of papermaking, the project embodies a sequence of making, from material treatment to production. The collection and treatment of water forms another sequence in the project. The different sequences in the project helps me to understand the logistics and make appropriate design decisions.

Assemble, Granby Workshop, 2015

The workshop produces ceramic products being used in the neighbourhood renovation and then sold to the other places. It leads to the idea of collaboration sequence of communal care.

Founded by Assemble, the Granby Workshop works alongside residents from the Granby Four Streets in Liverpool to rebuild their neighbourhood. Assemble, https://assemblestudio.co.uk/ projects/granby-workshop.

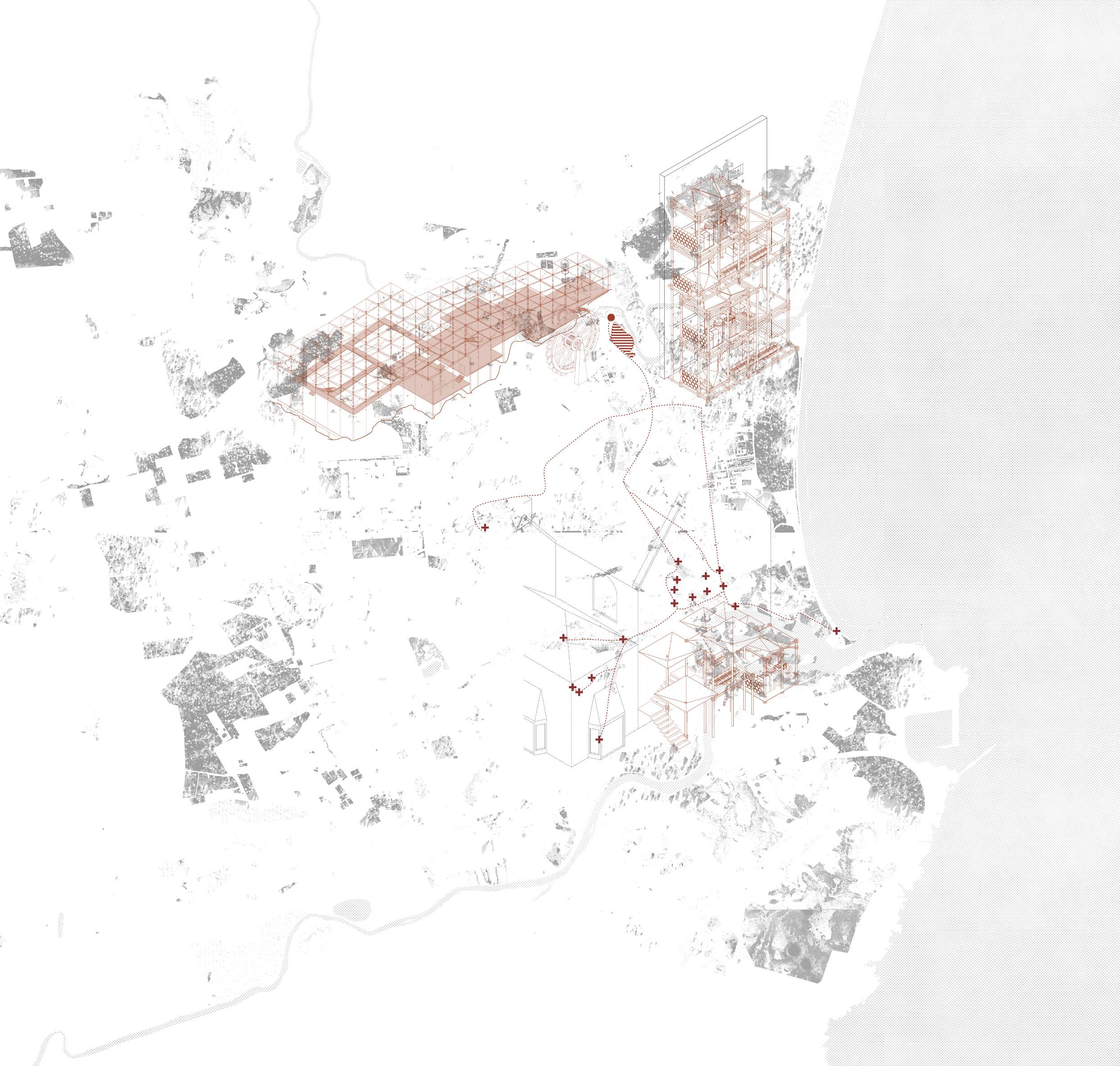

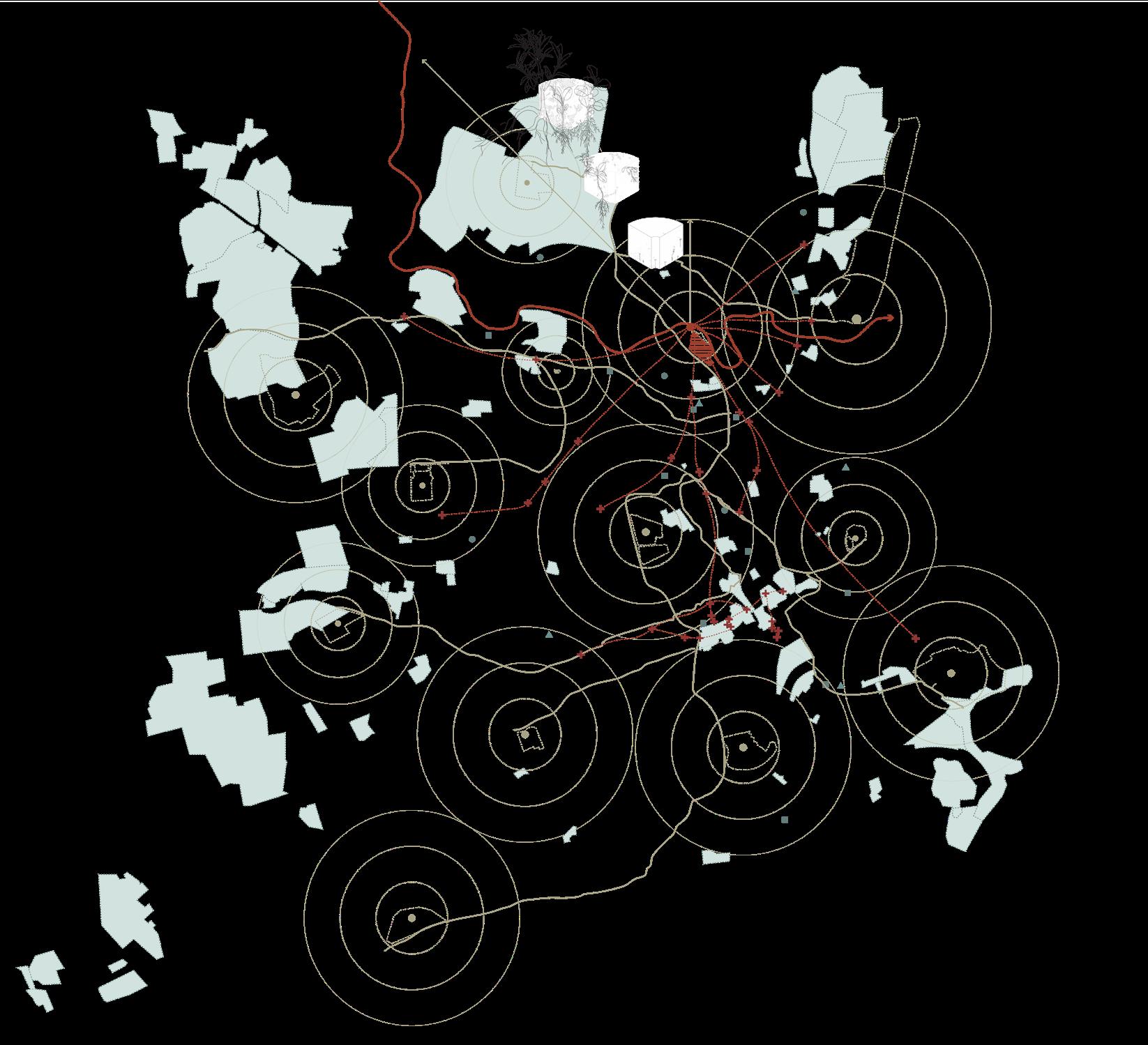

I initially identified three typologies in the collaboration sequence. The support structures are considered across different scale: domestic, streets, and communal.

The site map shows two different networks: paper recycling and worm box.

The paper recycling takes place domestically and leads to the paper mill.

The worm box recycles the food waste of the community. They are placed along the streets. 60 metres radii were drawn for the boxes to cover all the households.

The paper mill situates at the north of the community, sitting beside the river as water is an important source for both energy and production.

As mentioned in previous sections, the first typology allows individuals to recycle paper in domestic space.

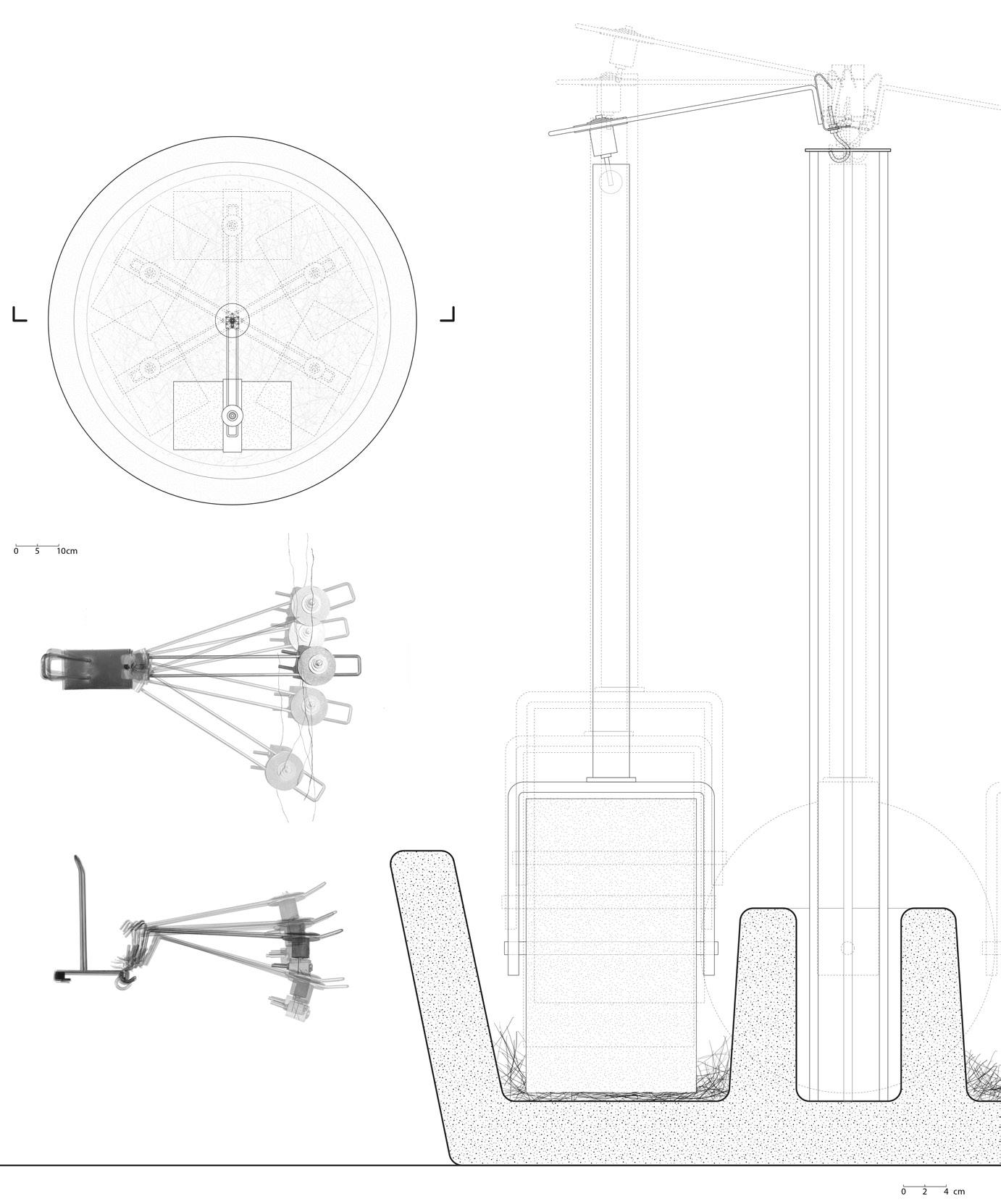

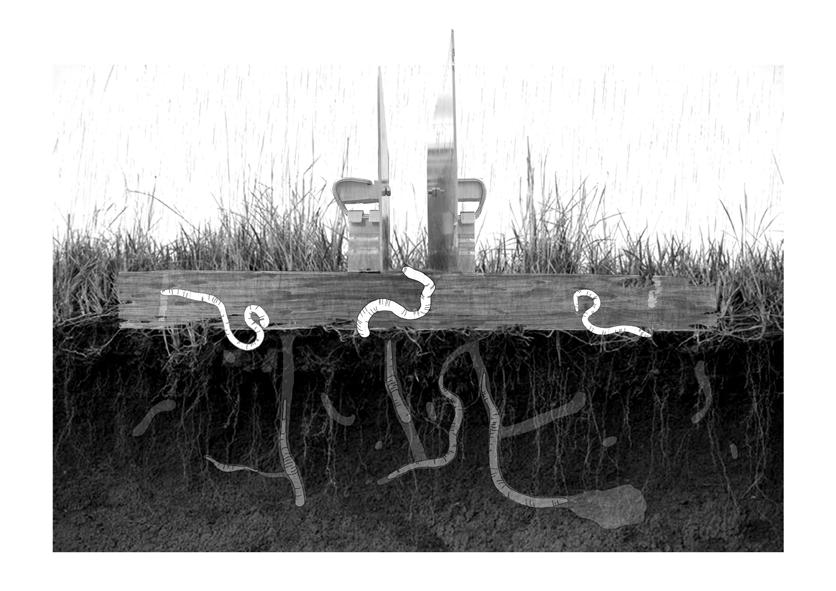

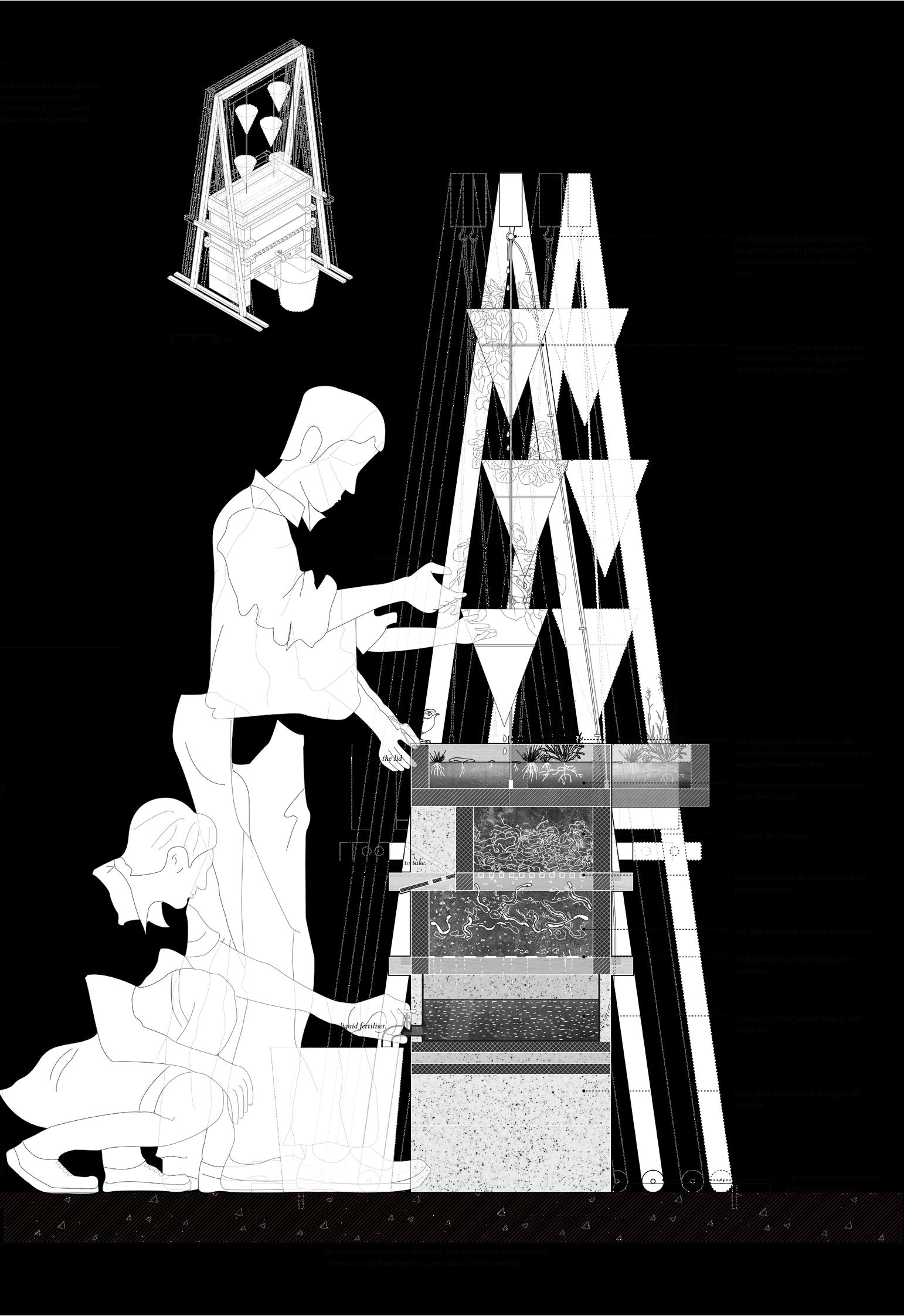

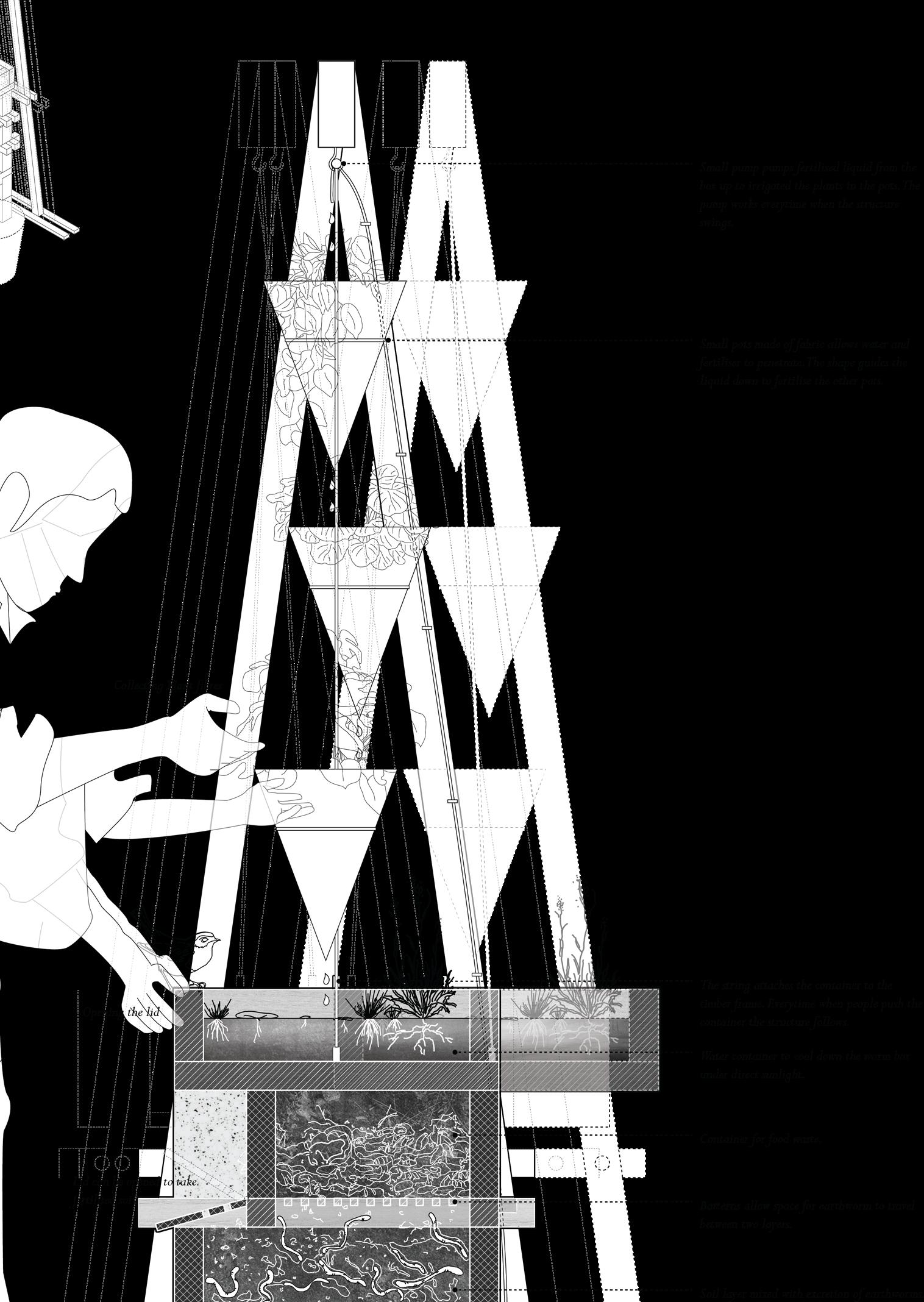

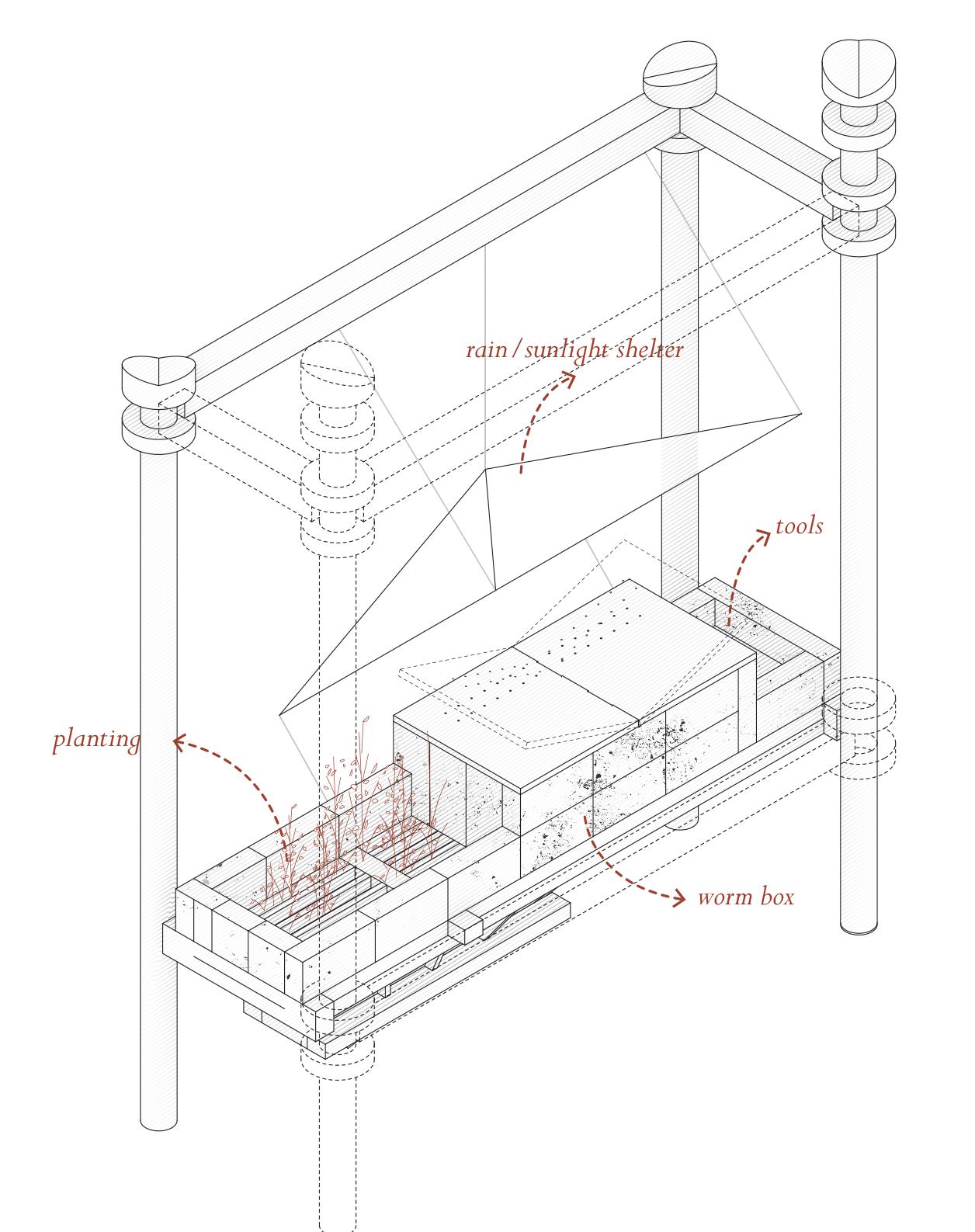

The wormboxes are placed in the streets of the urban village as the second scale. The Donside community contains a mixture of houses and flats. For people living in houses, the worm boxes are placed along the streets. For people living in flats, the boxes are constructed vertically, in front of the kitchen window of each level. People feed the worms directly outside their window. It becomes a collective effort to feed the worms and fertilise the plants for people living in the building.

A frame is constructed to support the pots and the lid of the box. The pool on the lid cools down the box under direct sunlight. The swing of the frame pumps the fertiliser up to feed the plants. Being placed along the streets, the wormbox collects food waste from across the community.

The design of the wormbox also follows the sequence of decomposing. The flow of fertiliser forms a loop in this structure.

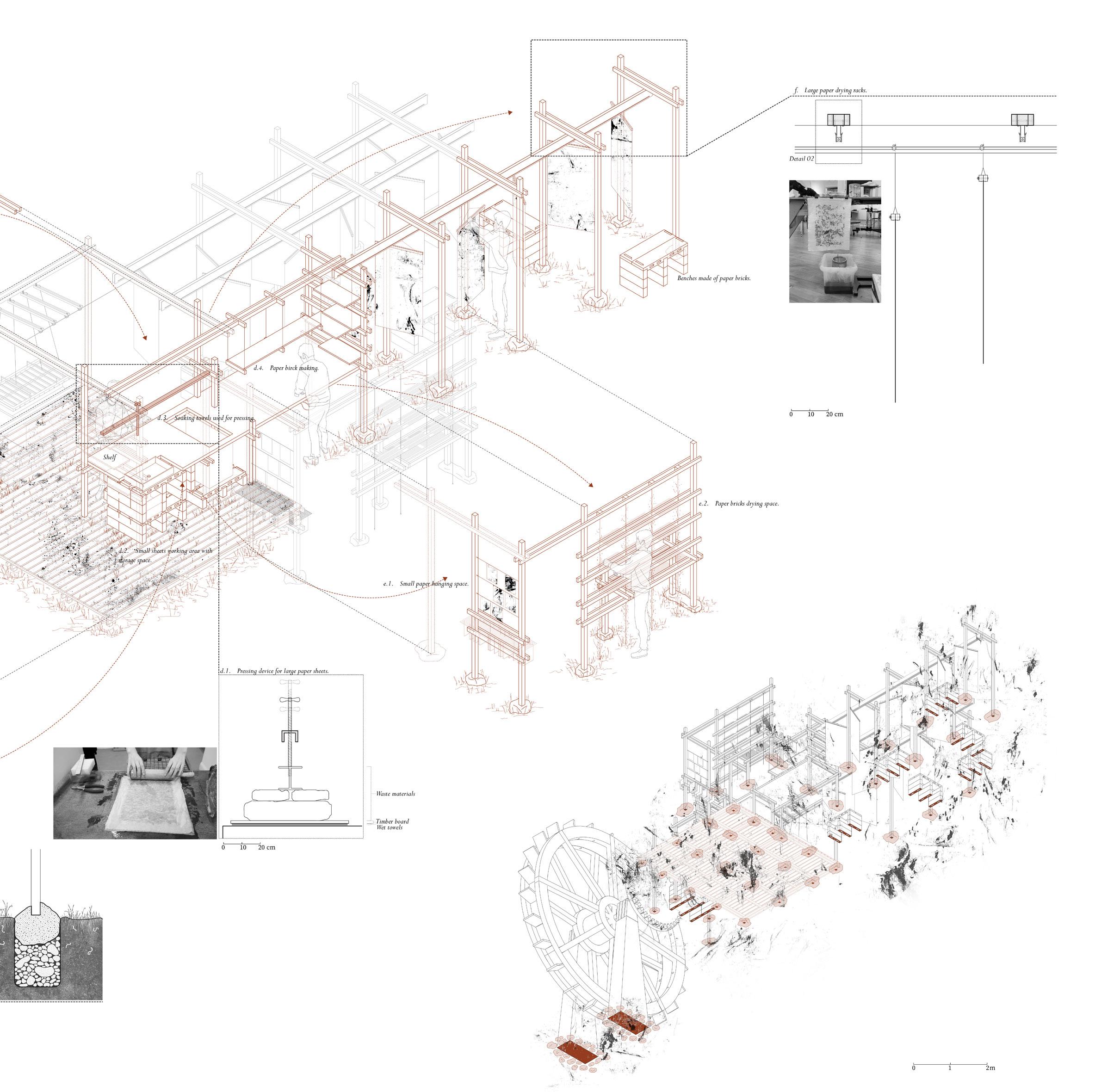

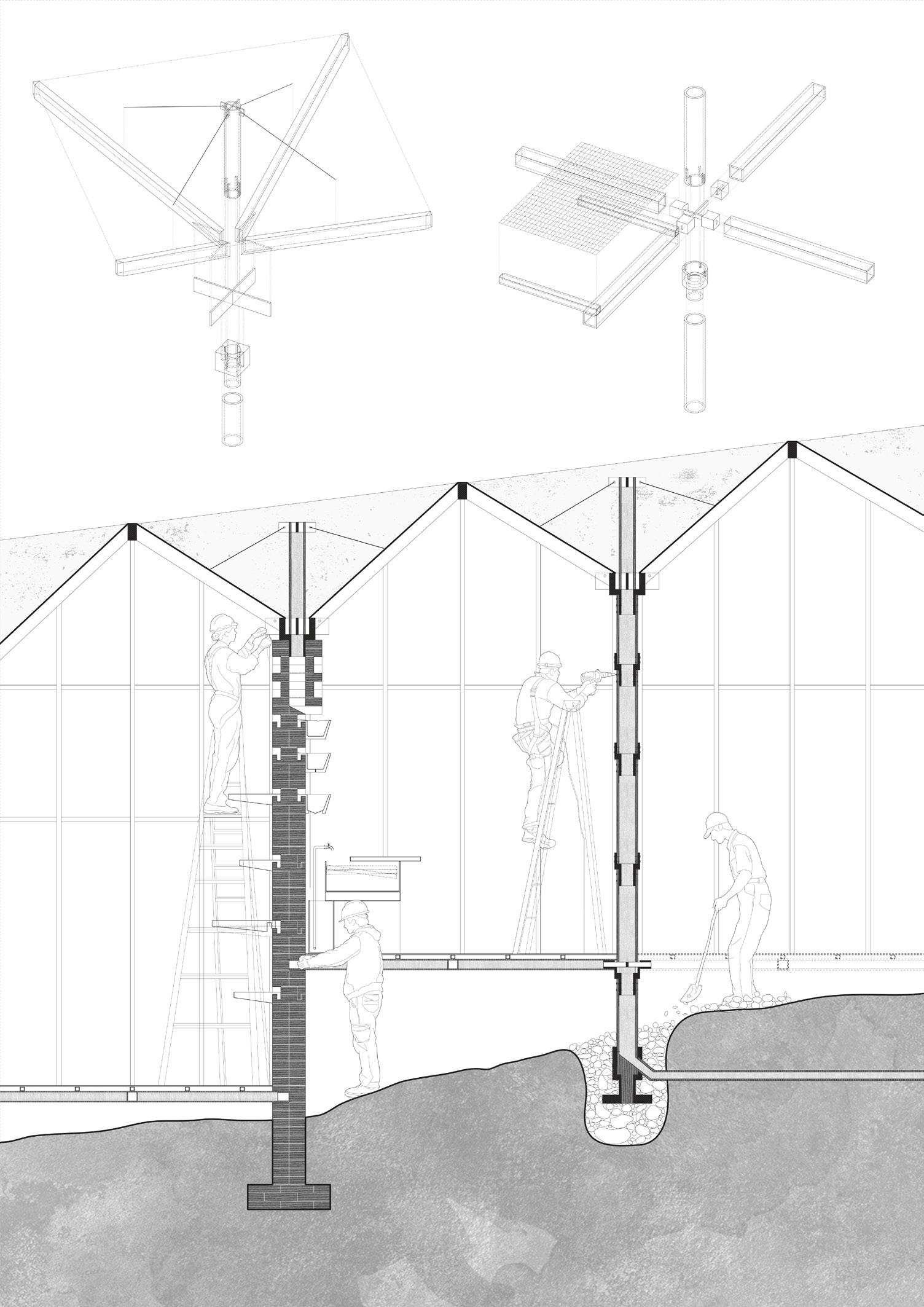

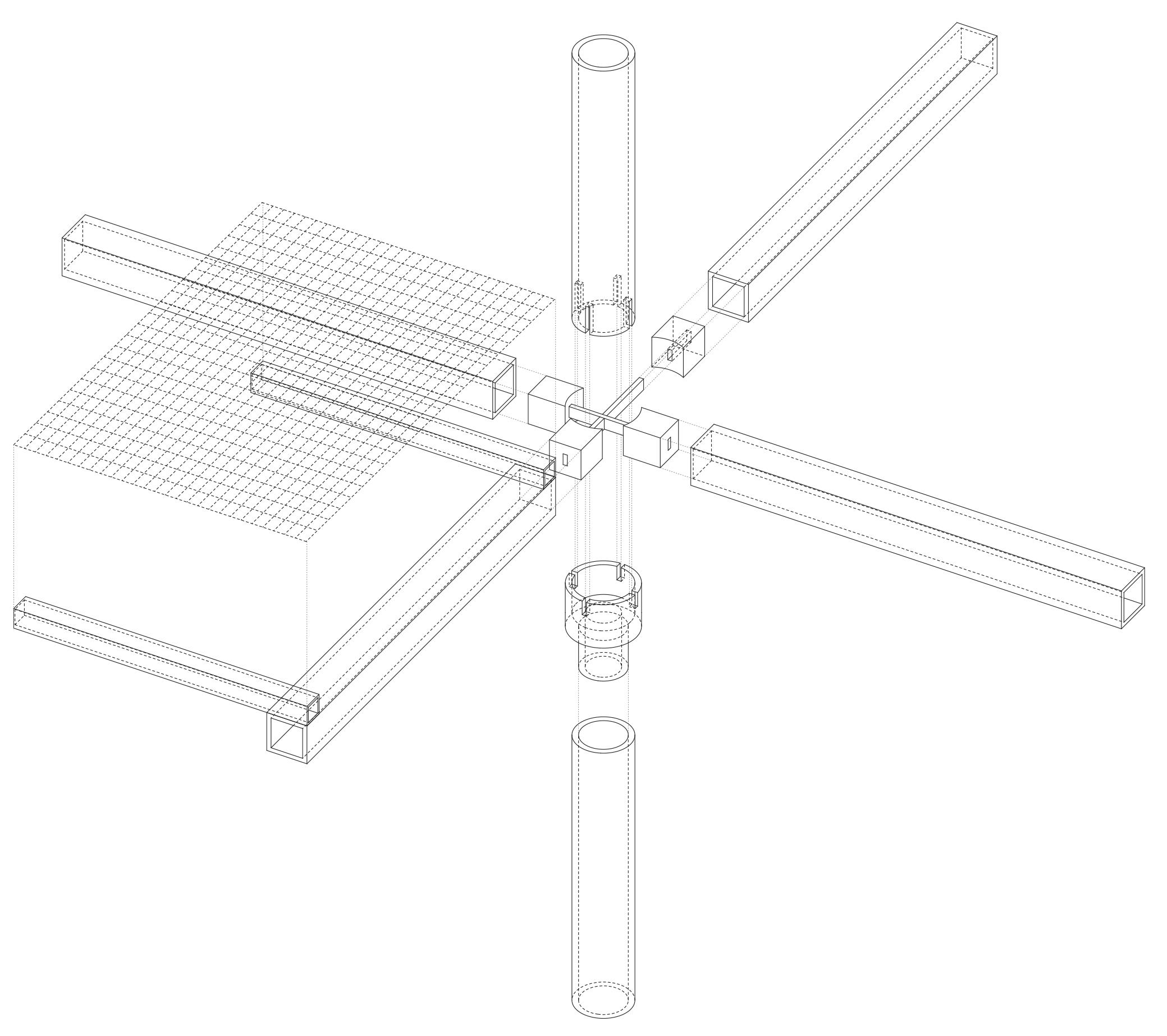

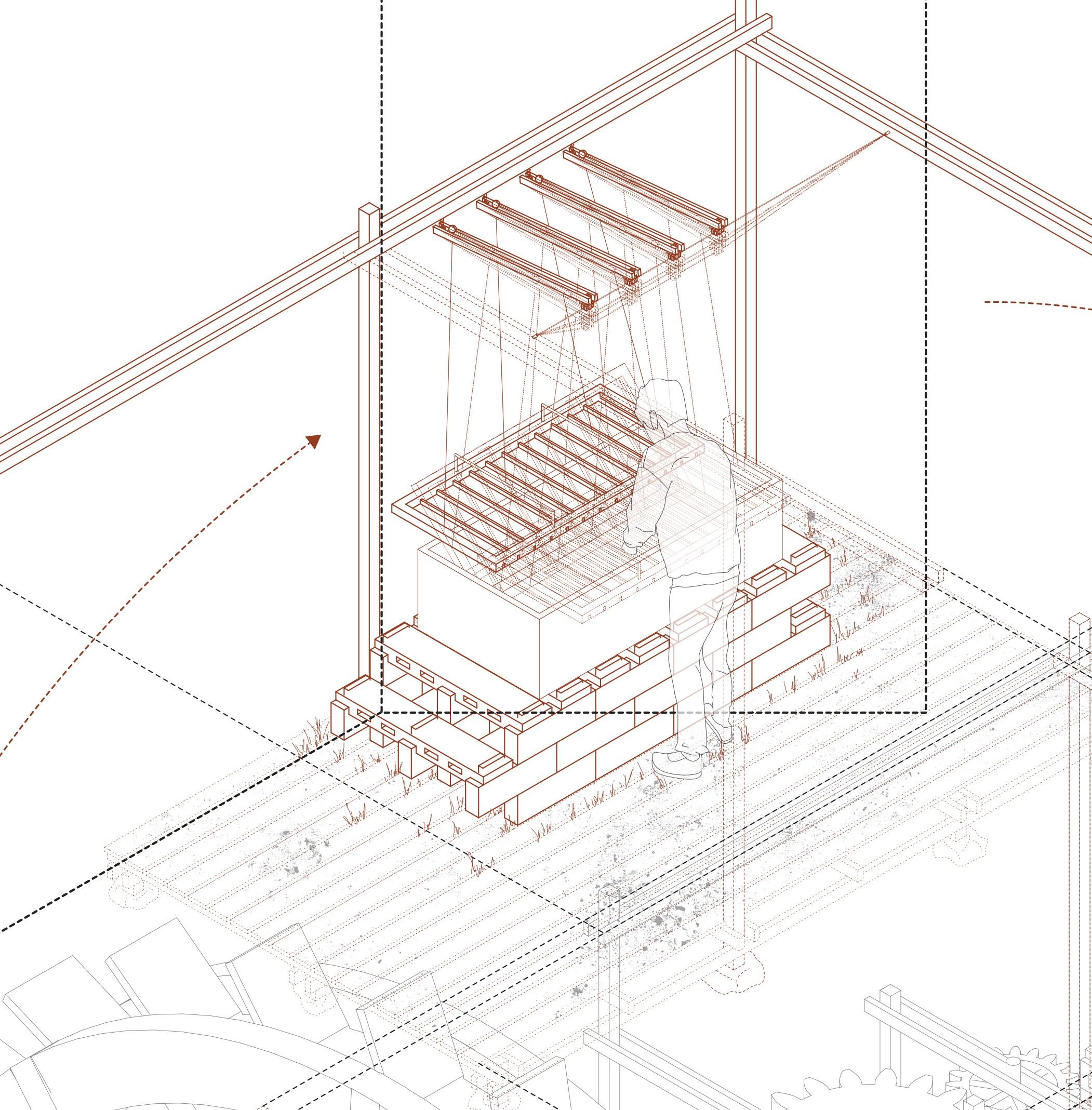

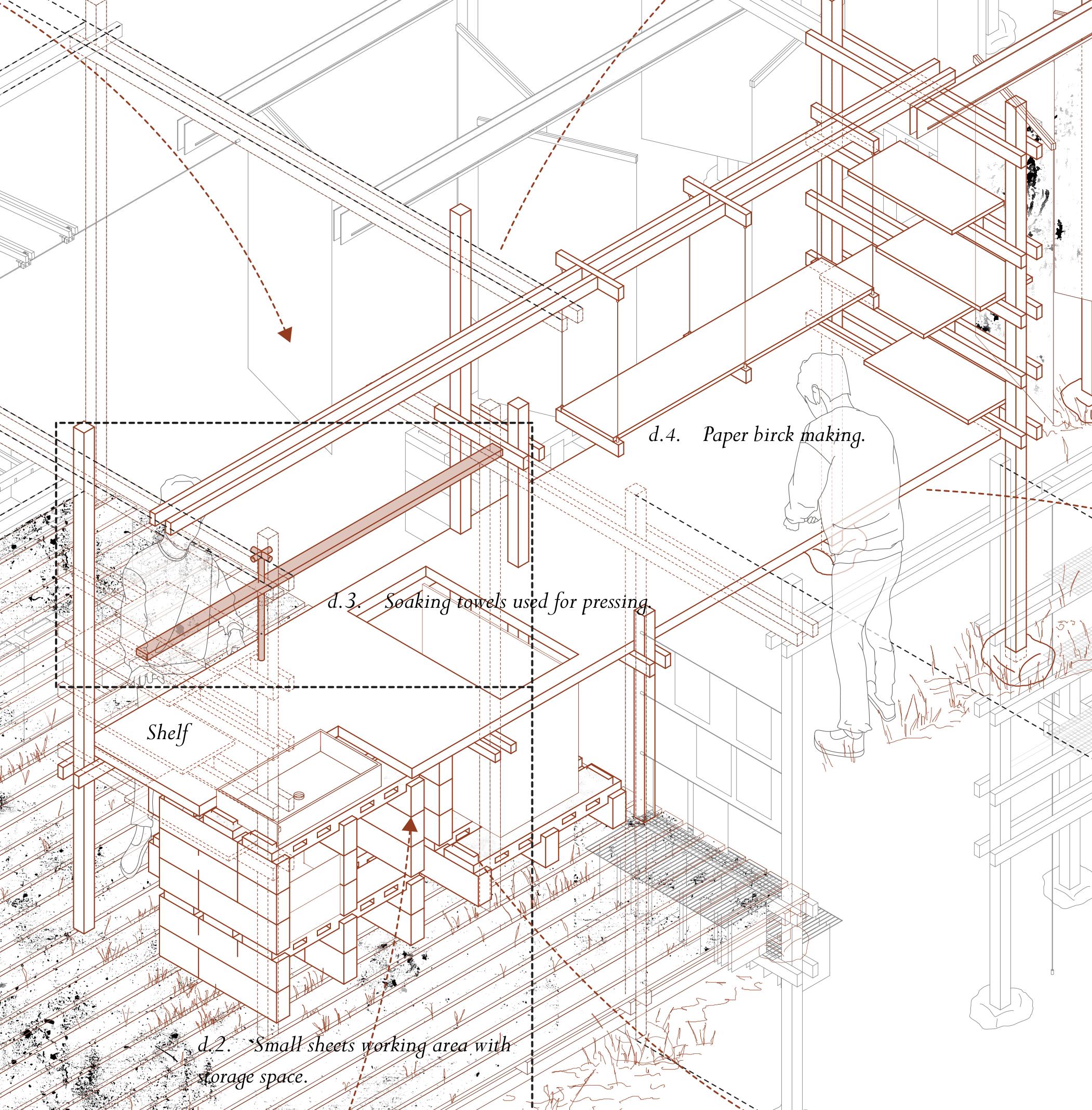

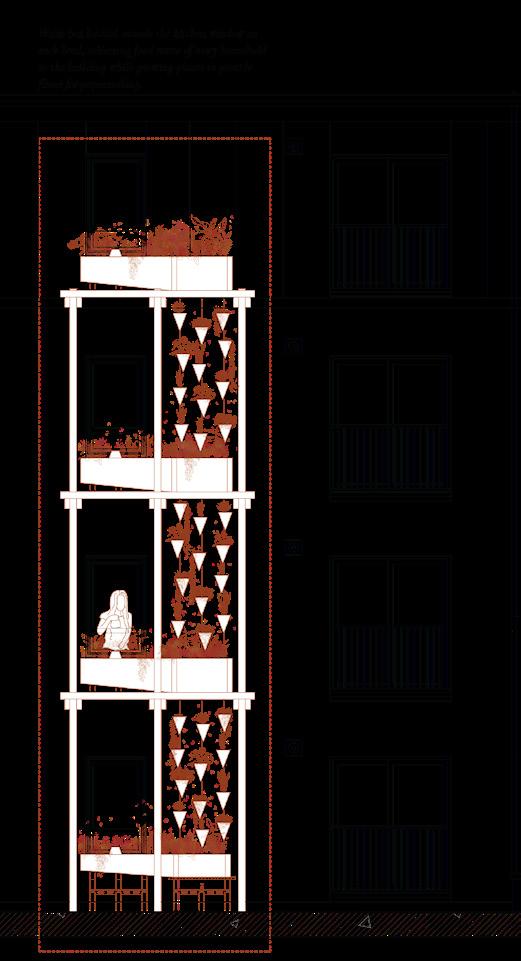

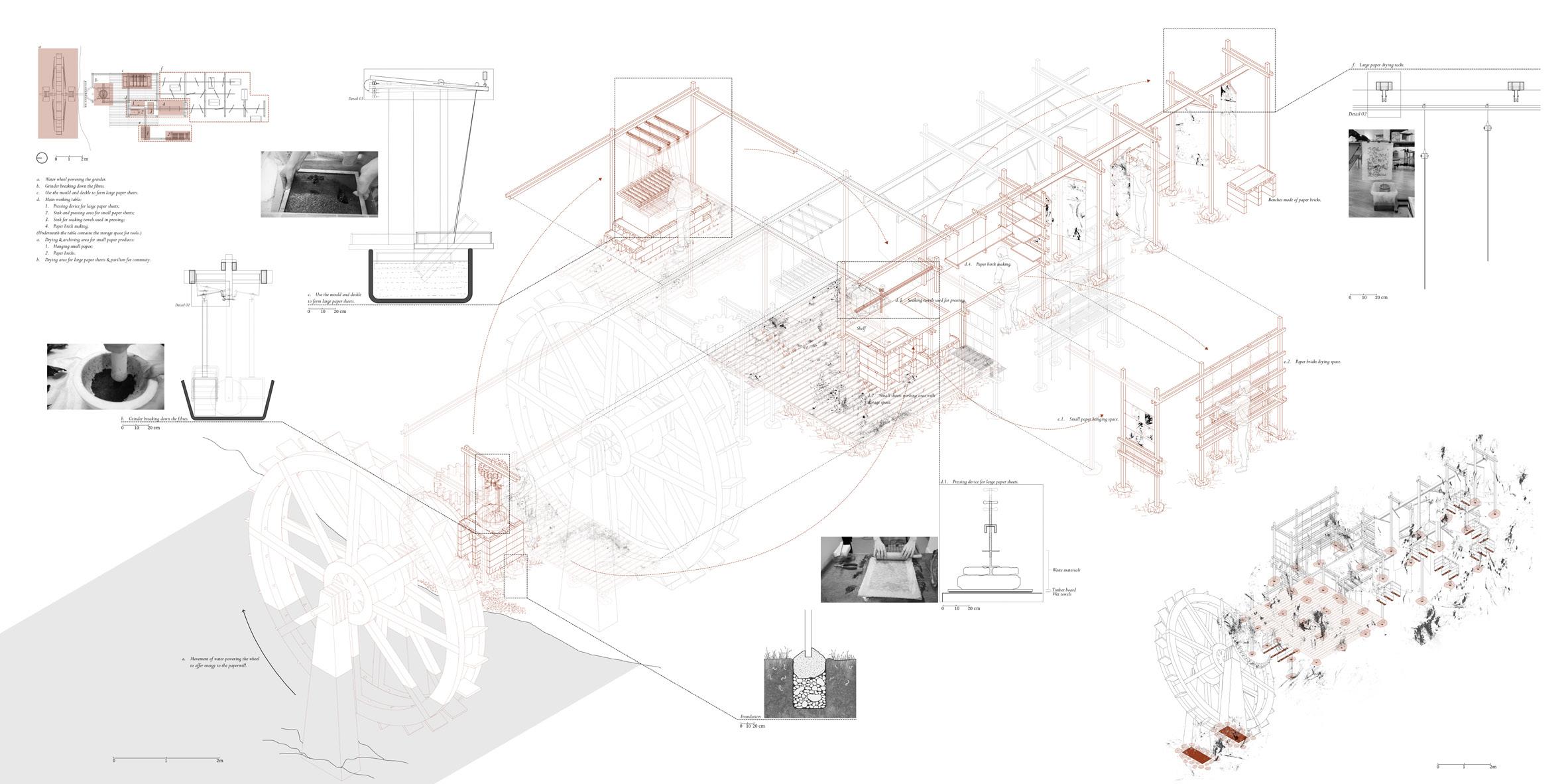

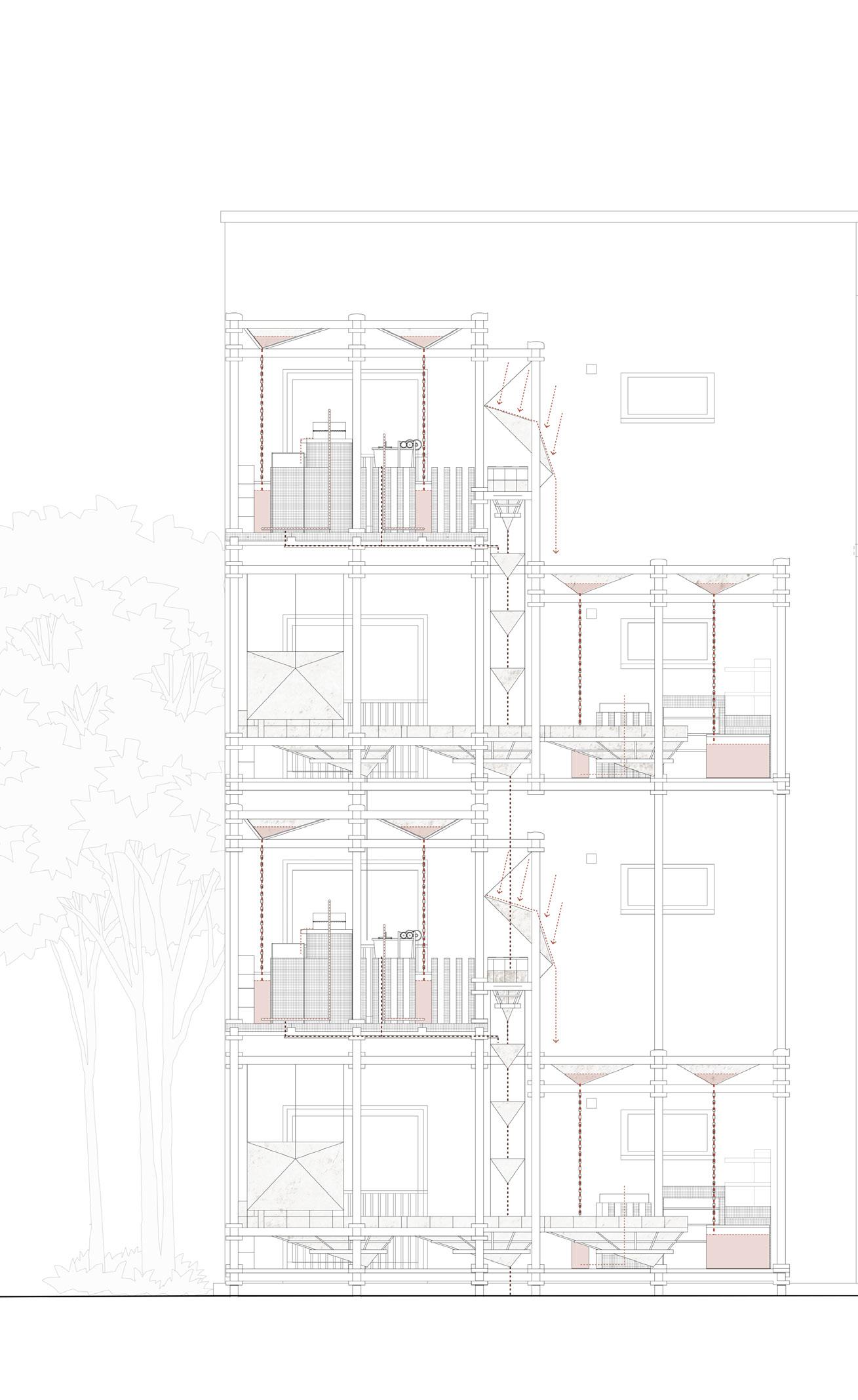

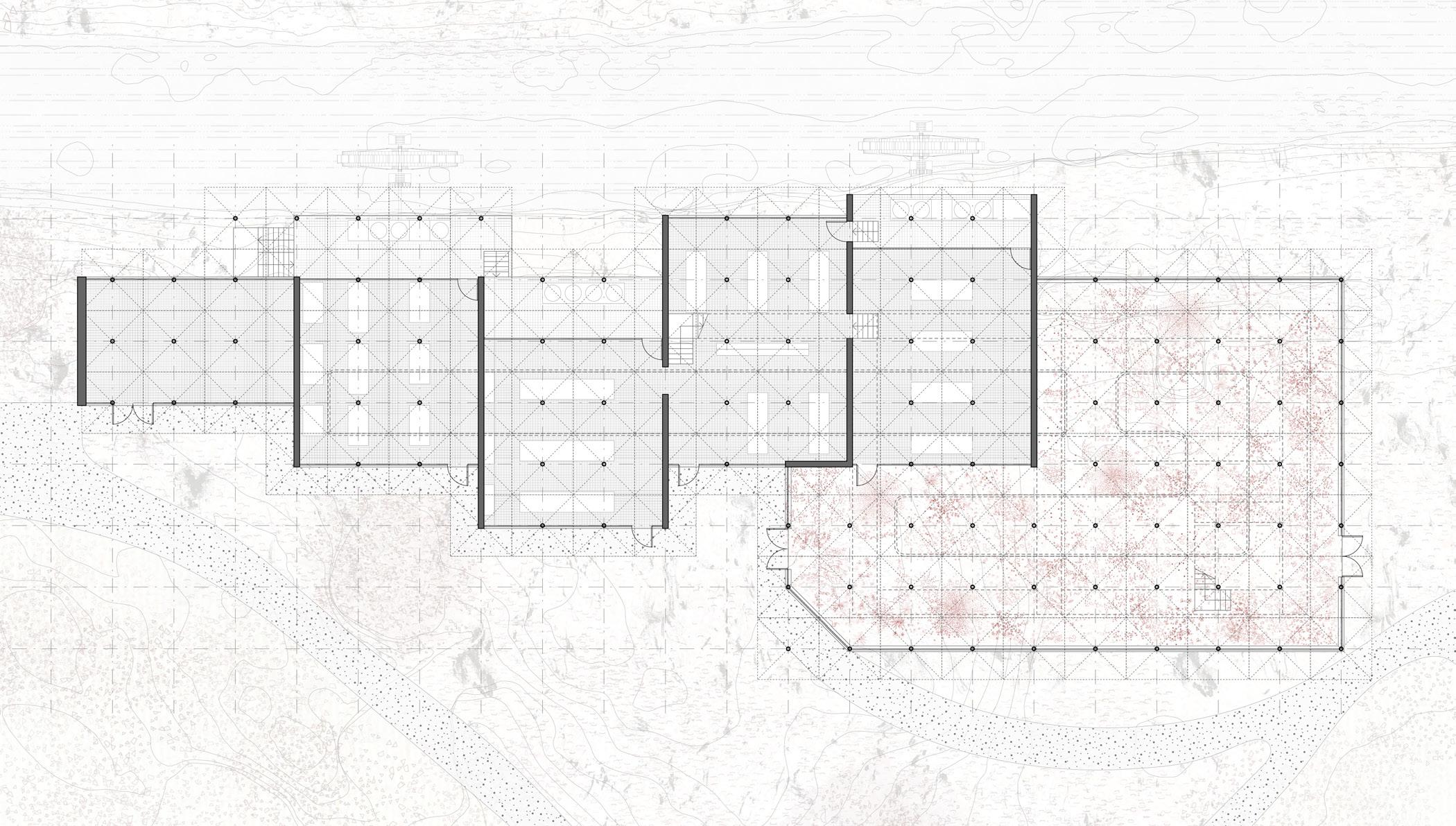

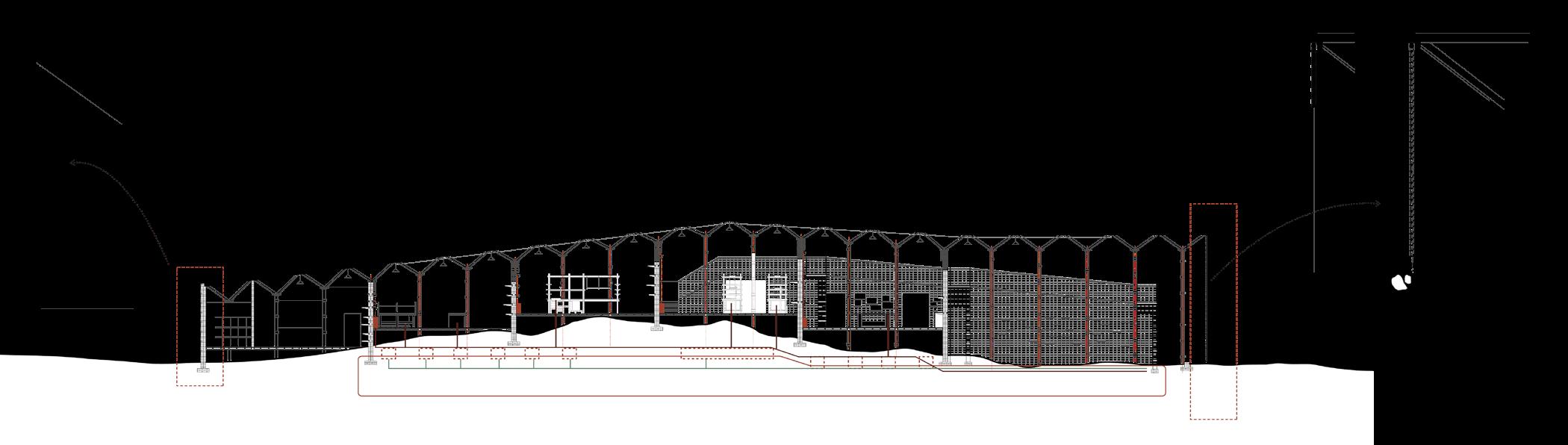

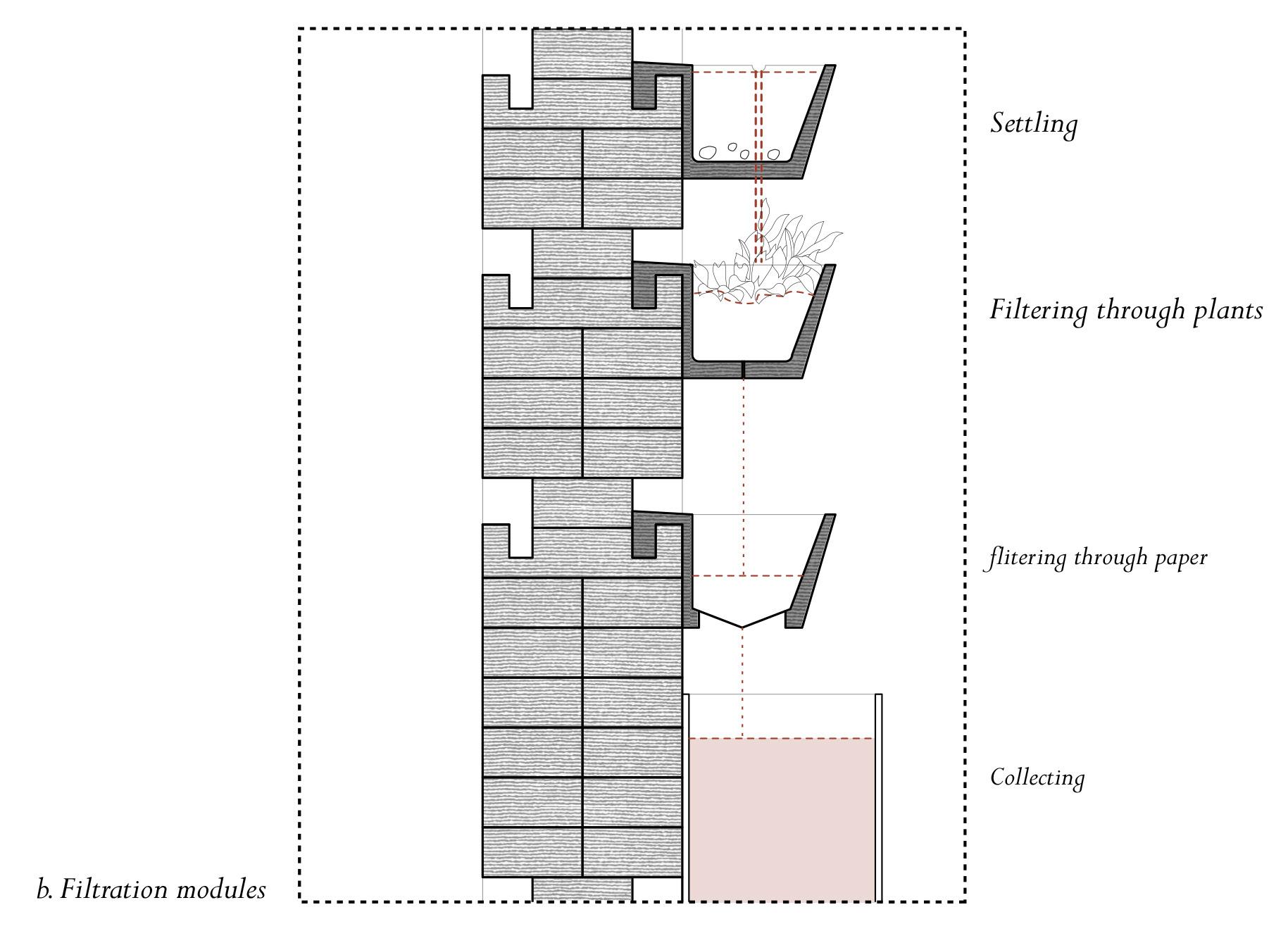

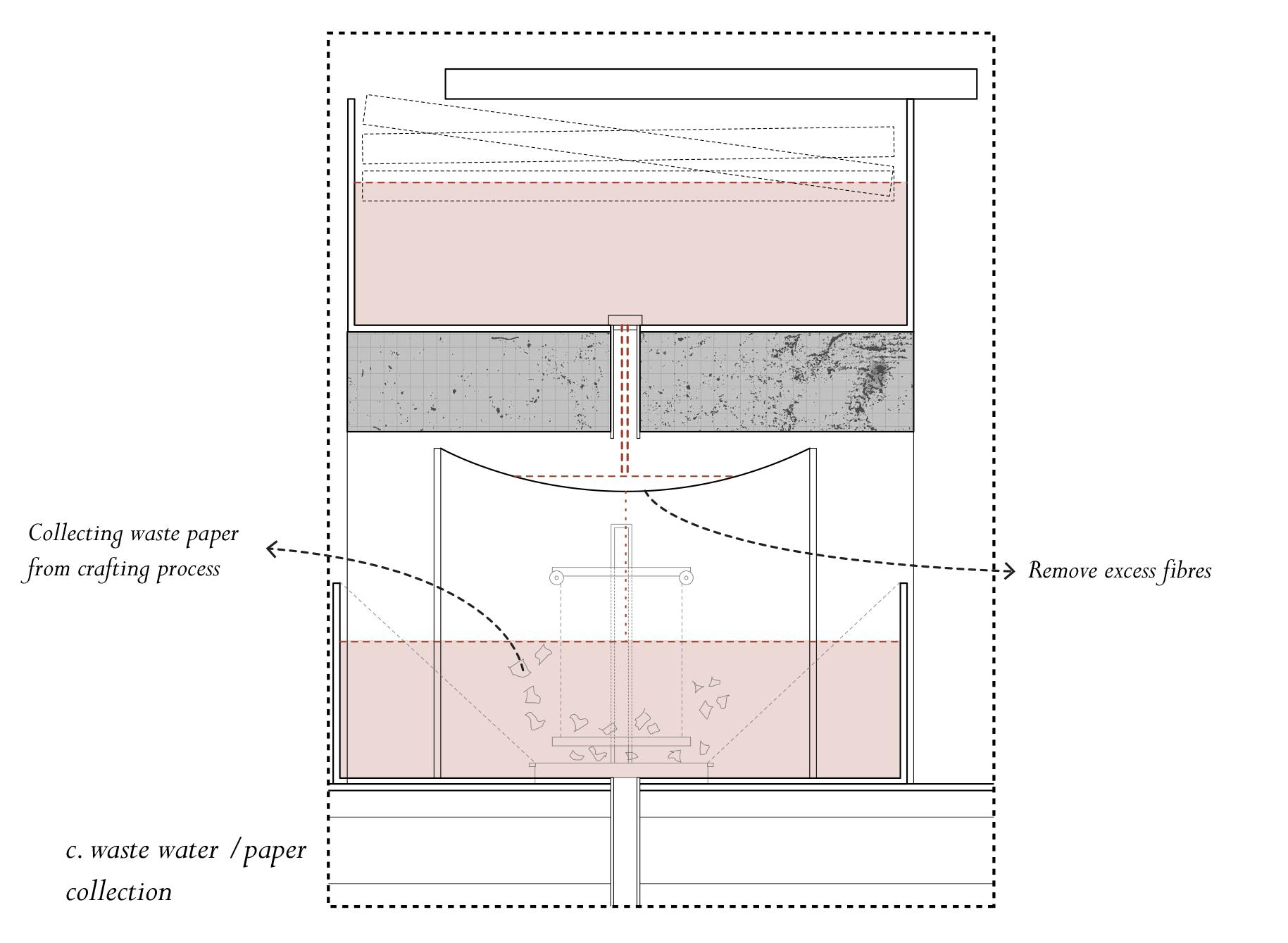

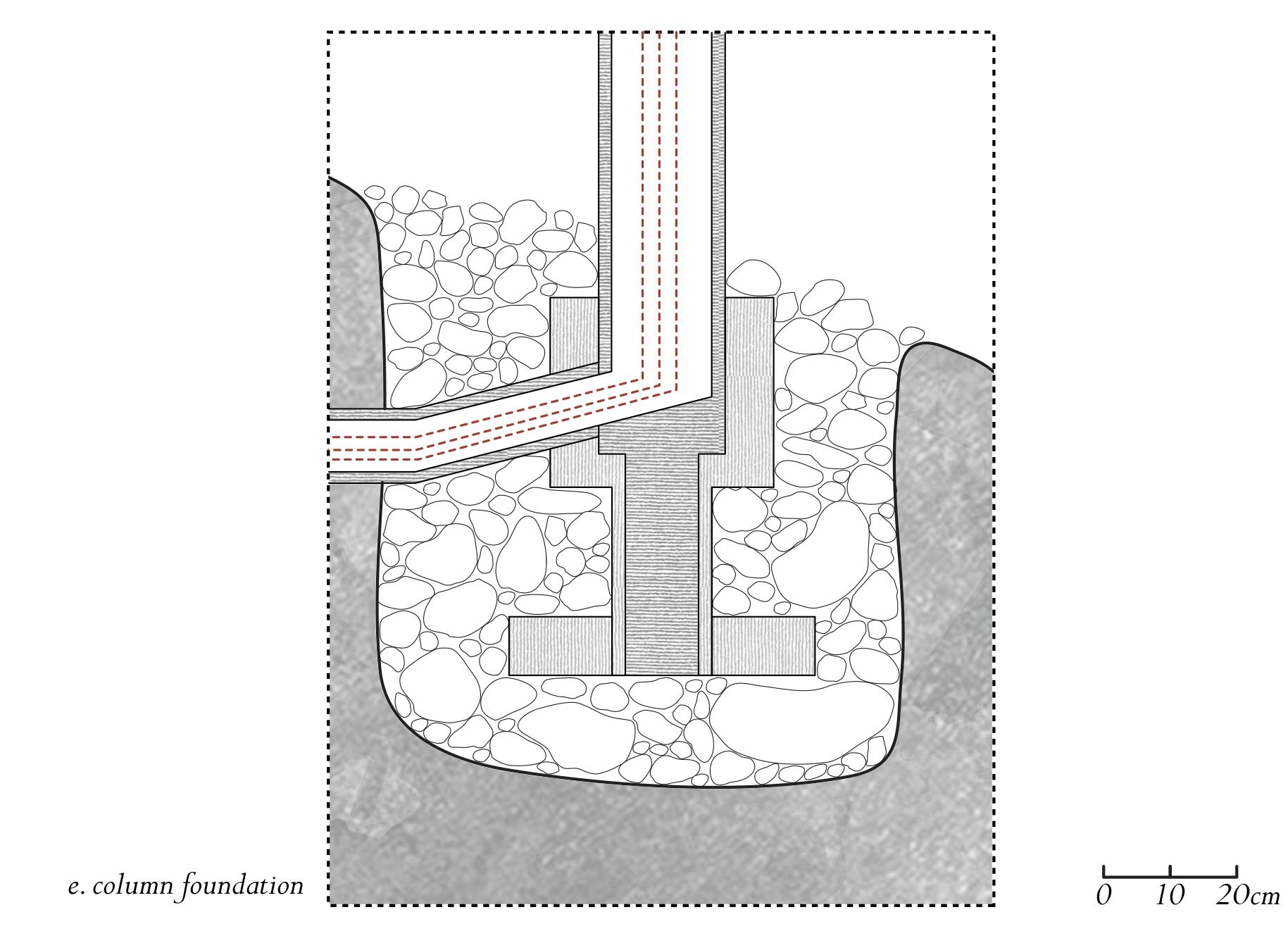

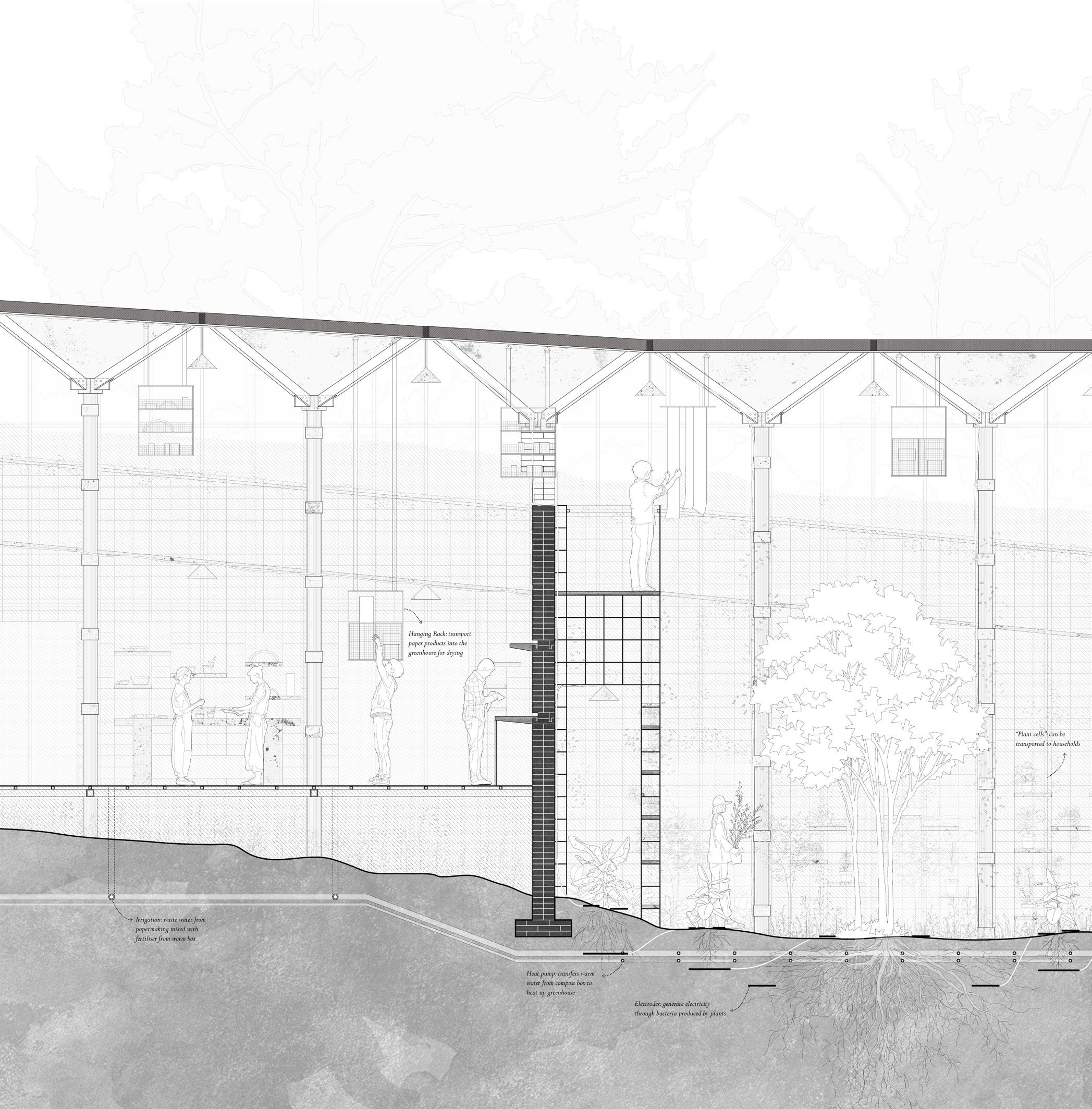

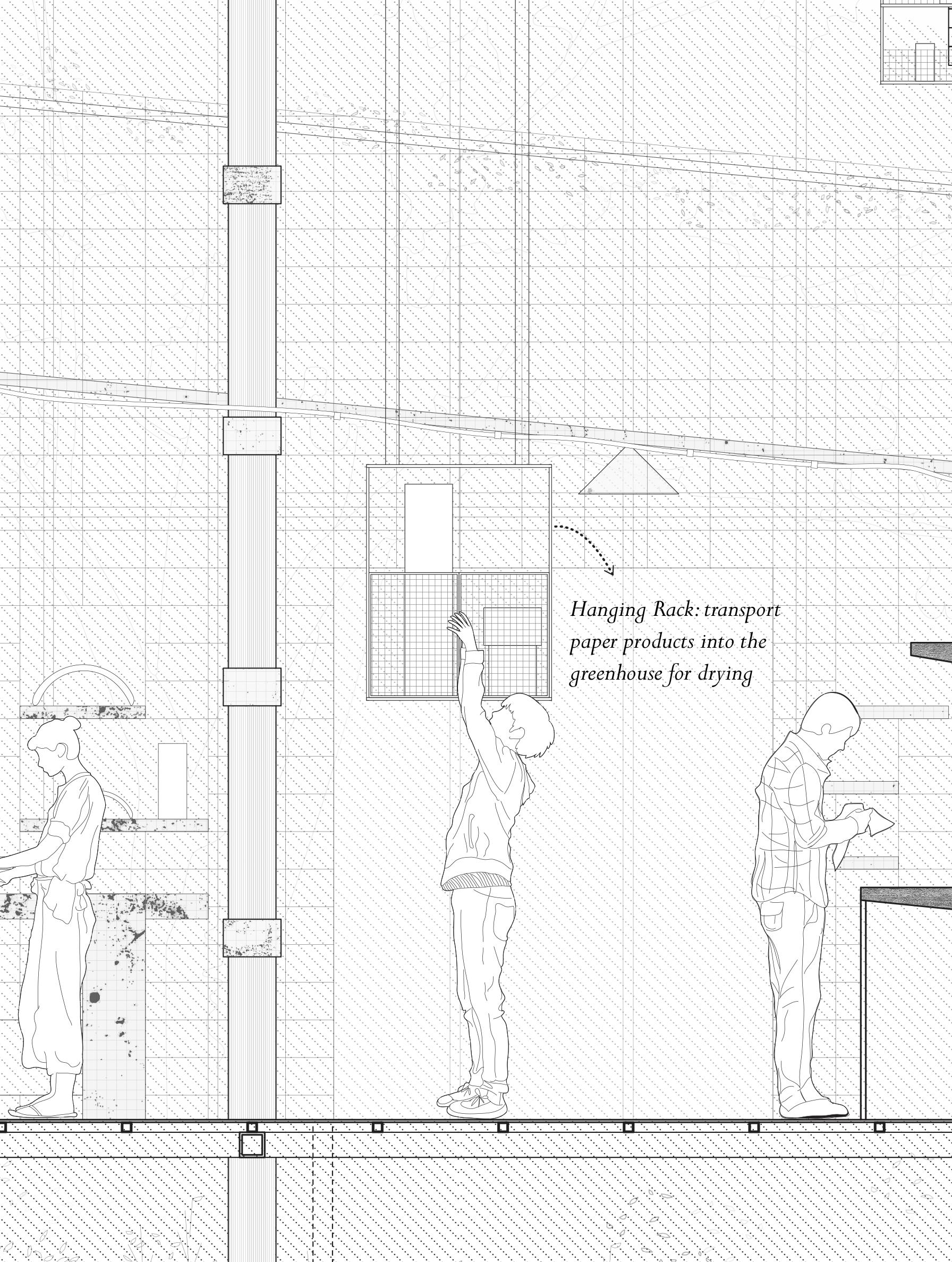

Serving the community as the third scale, the papermill is powered by the River Don. The mill integrates the papermaking process around a central working table. It offers space for making both large sheets and small sheets of paper and space for making paper bricks. The mill produces its own construction material which forms a loop of production.

Collaboration Sequence 02

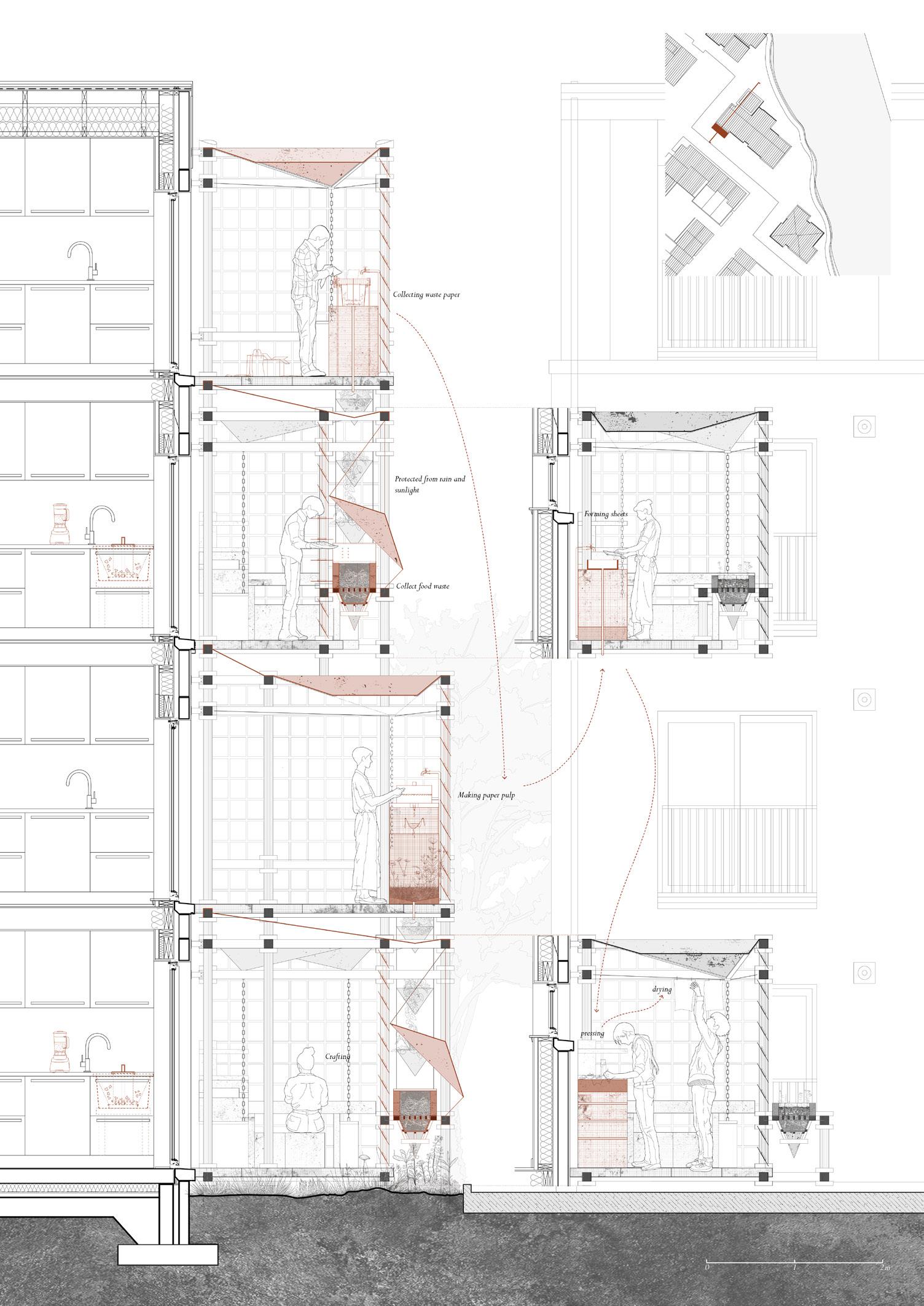

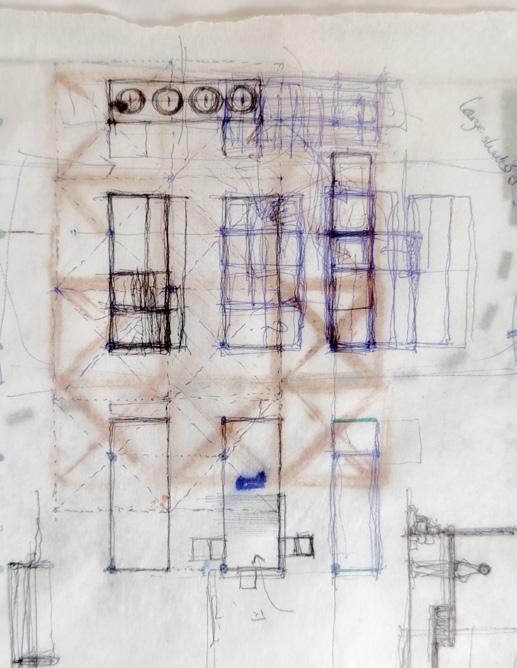

Further developing the typologies into architectural projects, the sequence is refined. It starts with an extension space outside the kitchen of a residential unit, providing space for papermaking. The map shows the locations of kitchen and extension space of each household. A route is established bring together the material produced by individuals to the communal papermill.

Initial Iterations

The initial iterations of the extension consist of platforms supporting the facilities. The structure is more temporal and not integrated with the system.

Kitchen Extension

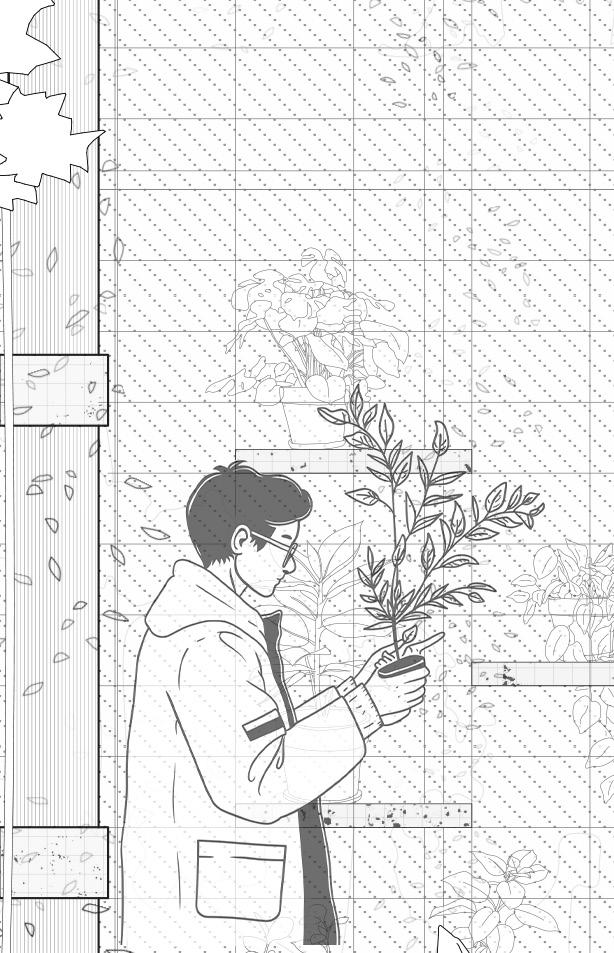

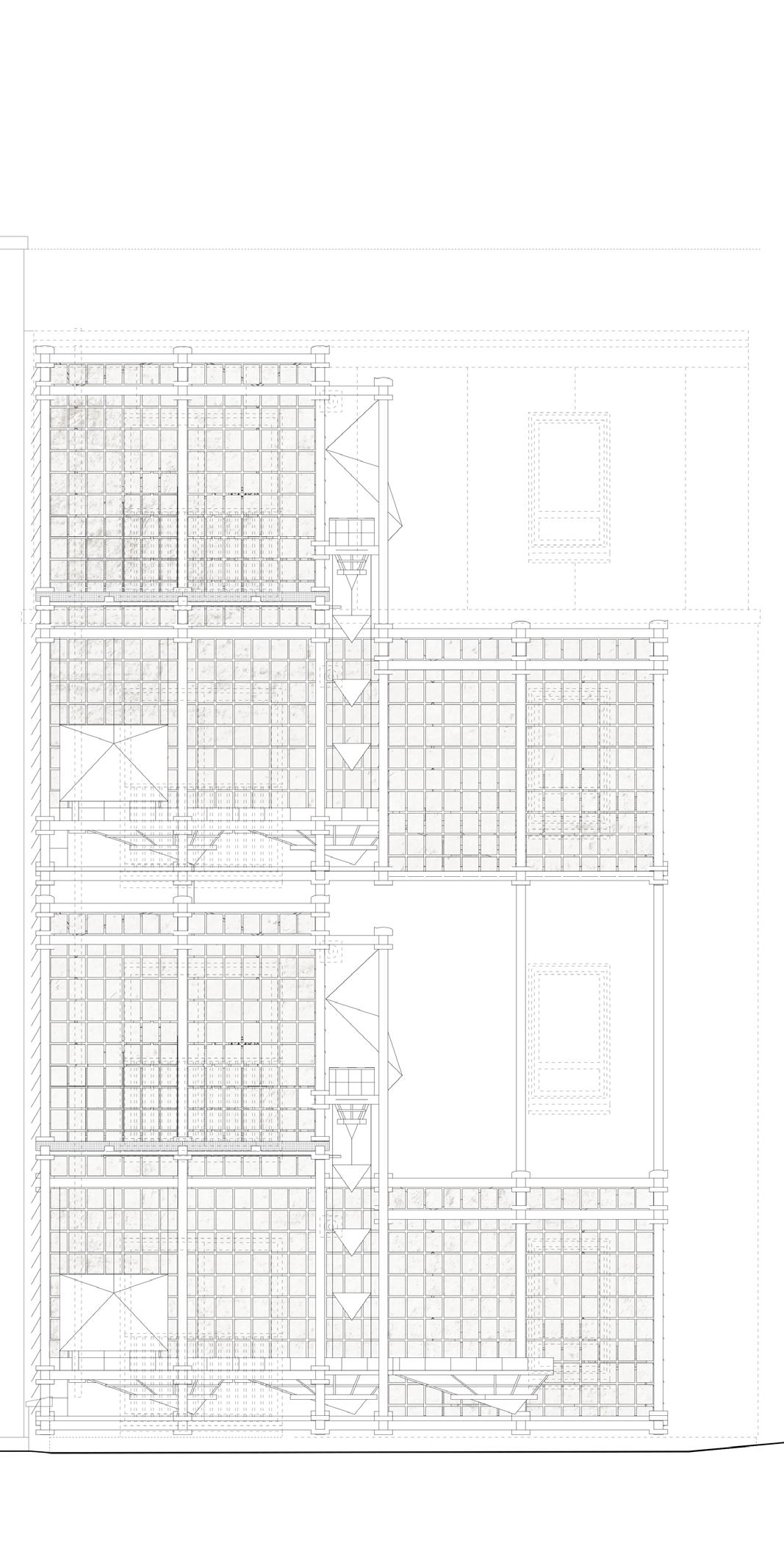

Material Treatment

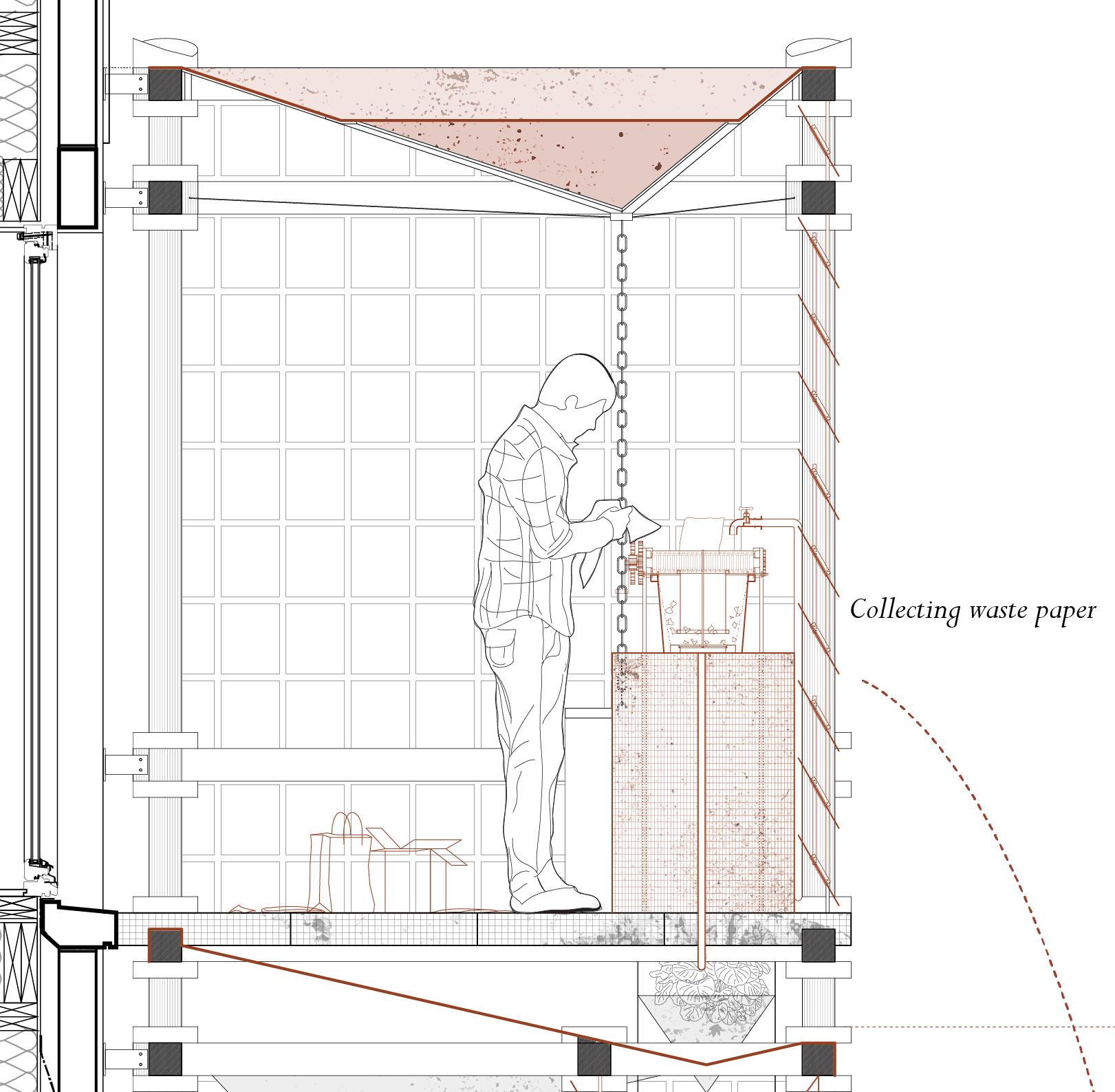

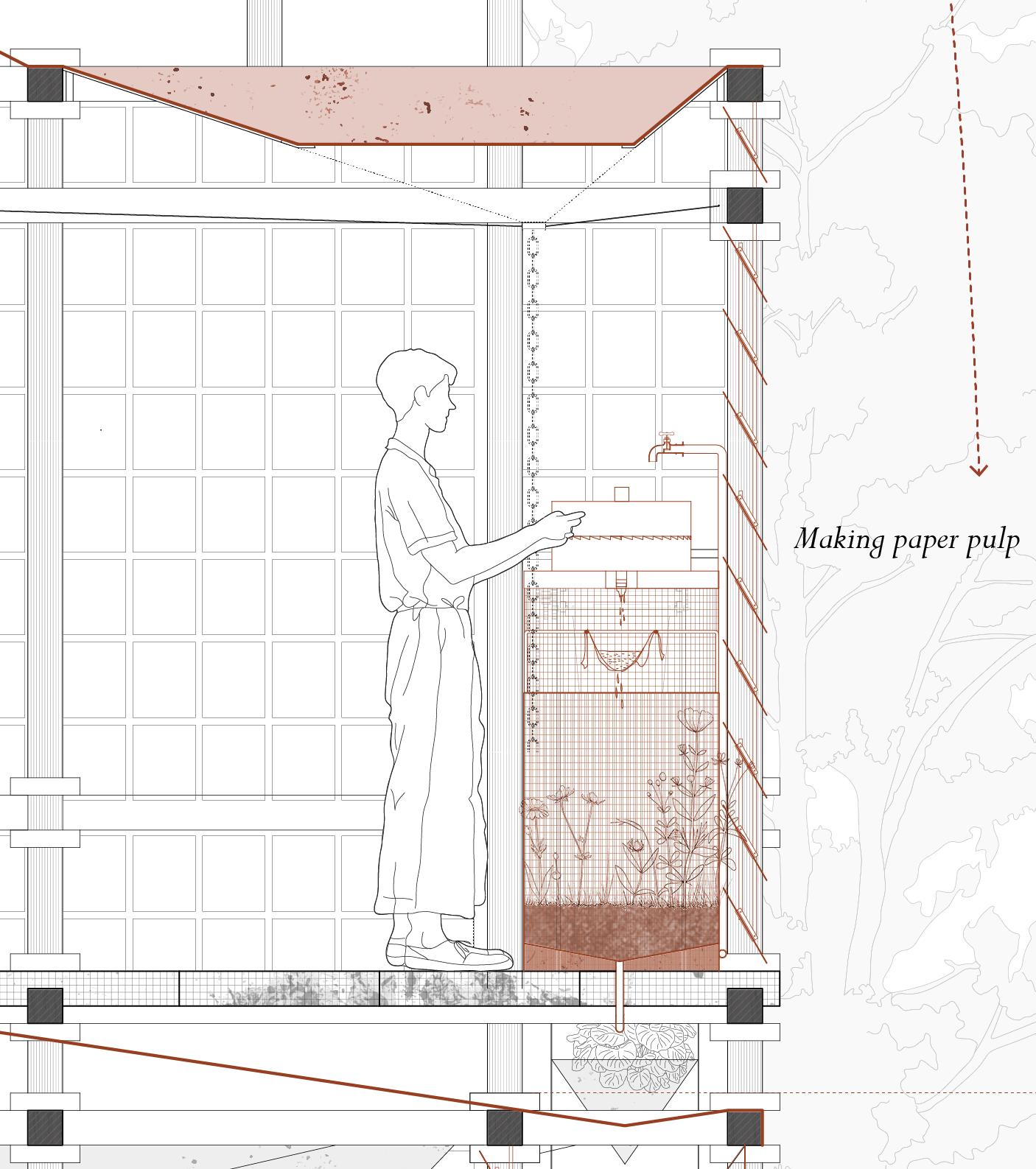

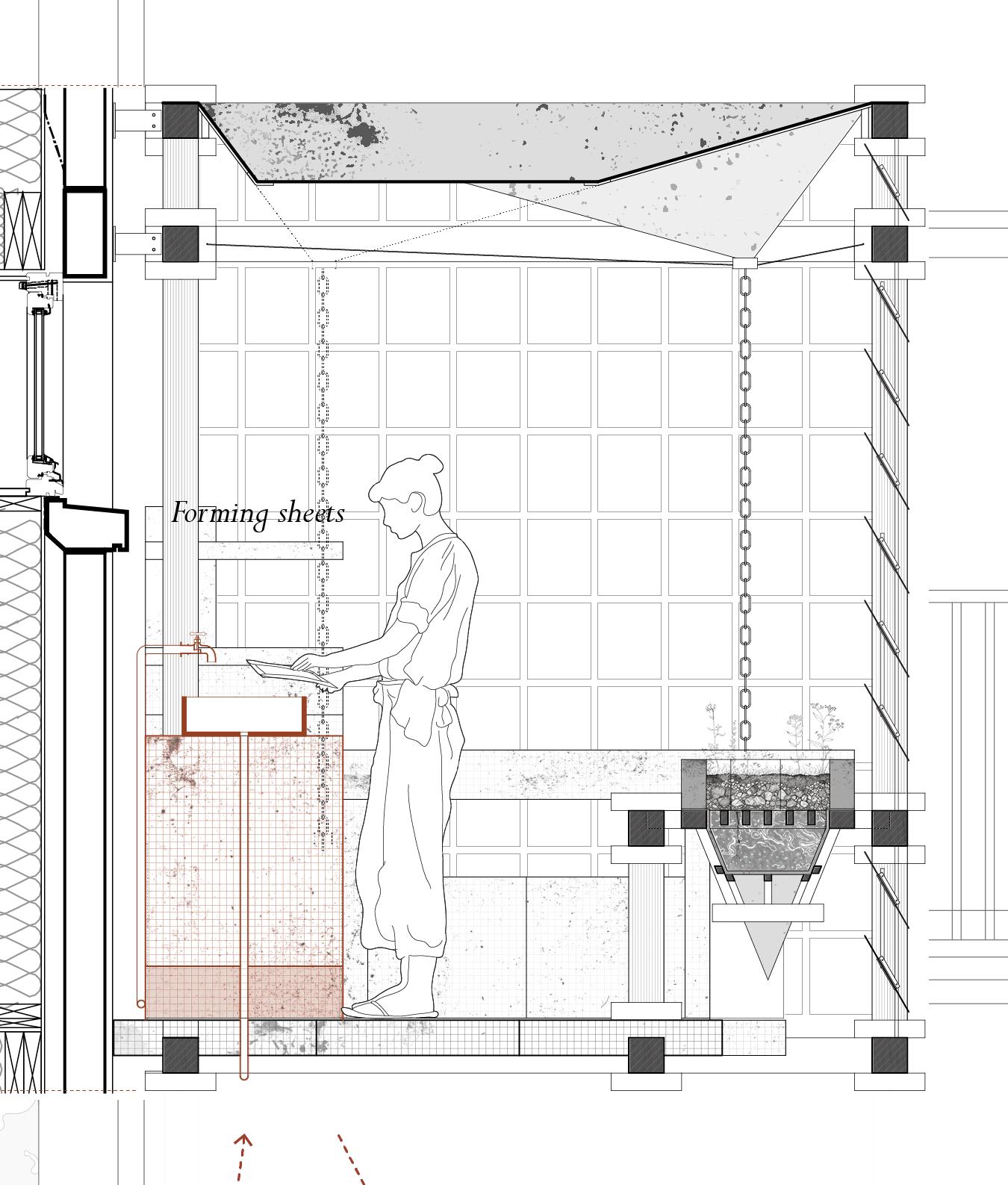

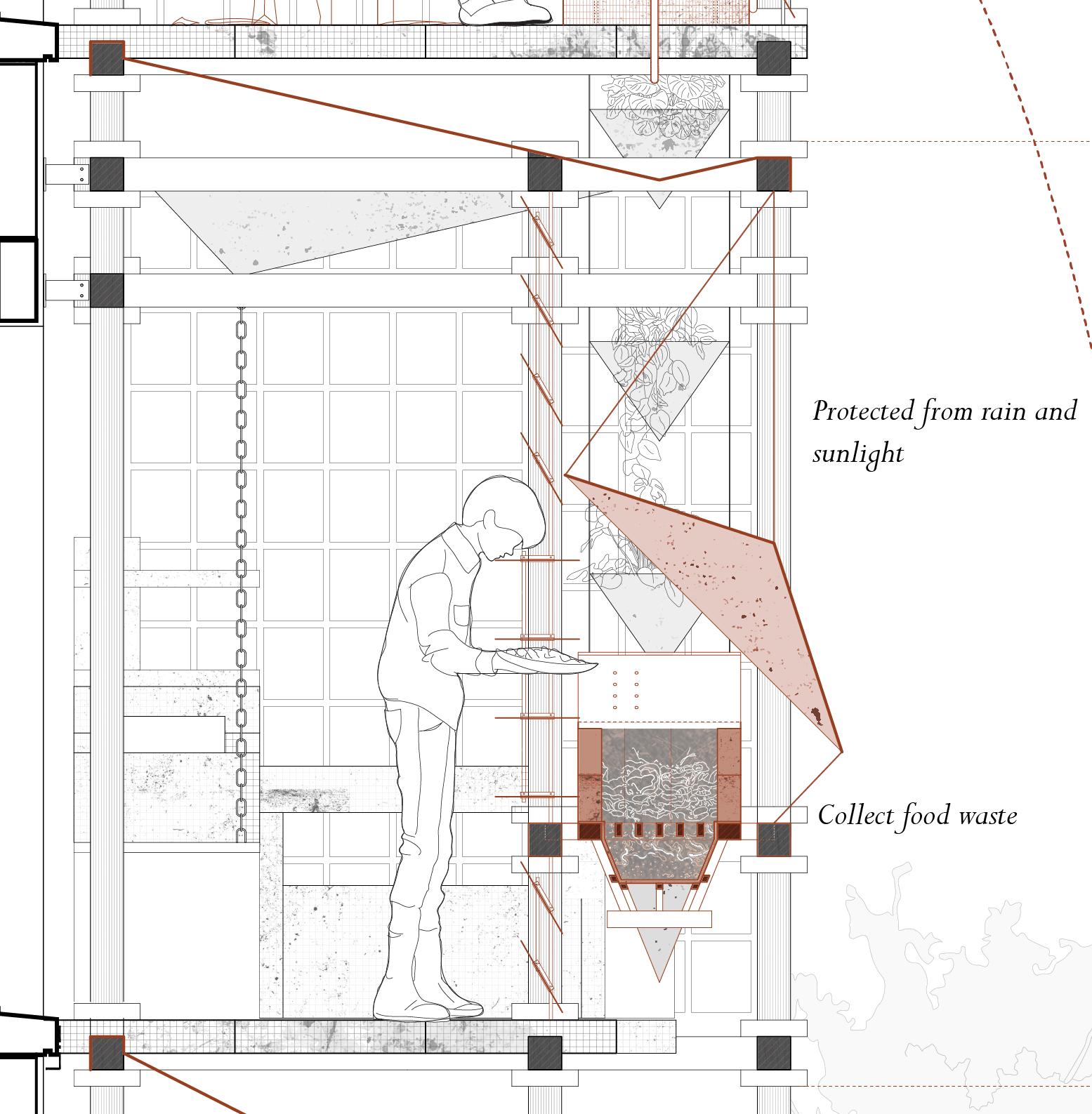

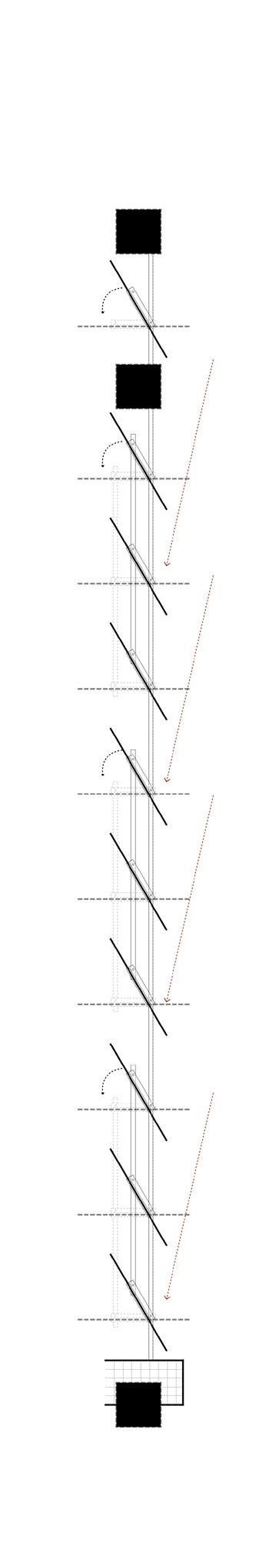

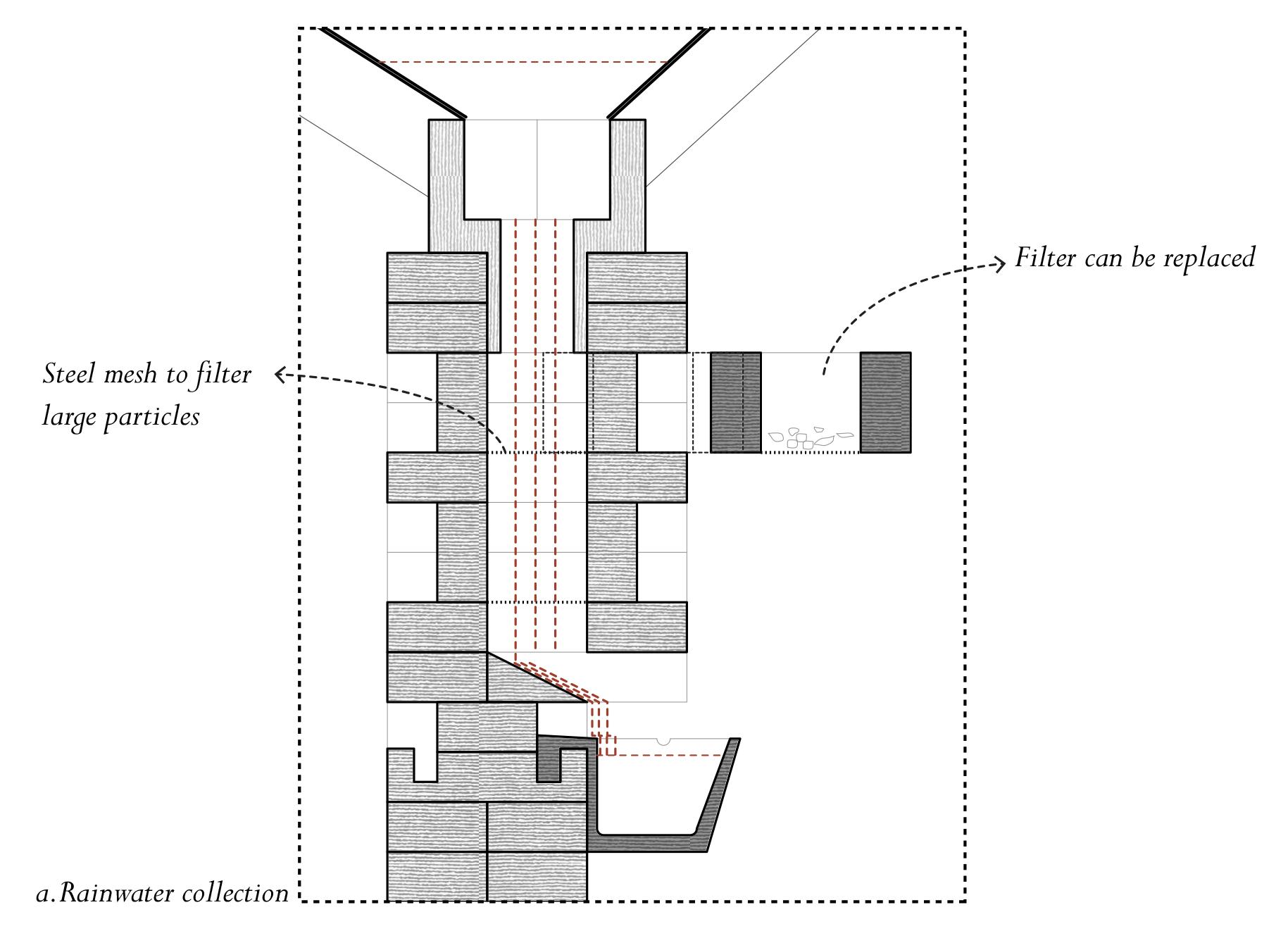

Developed from the wormbox outside the facade, the extension becomes an inhabitable space providing papermaking facilities. The new facade is a composition of modules designed according to different stages of papermaking. The section shows the key stages of the process of material treatment which sets the basis of the collaboration sequence.

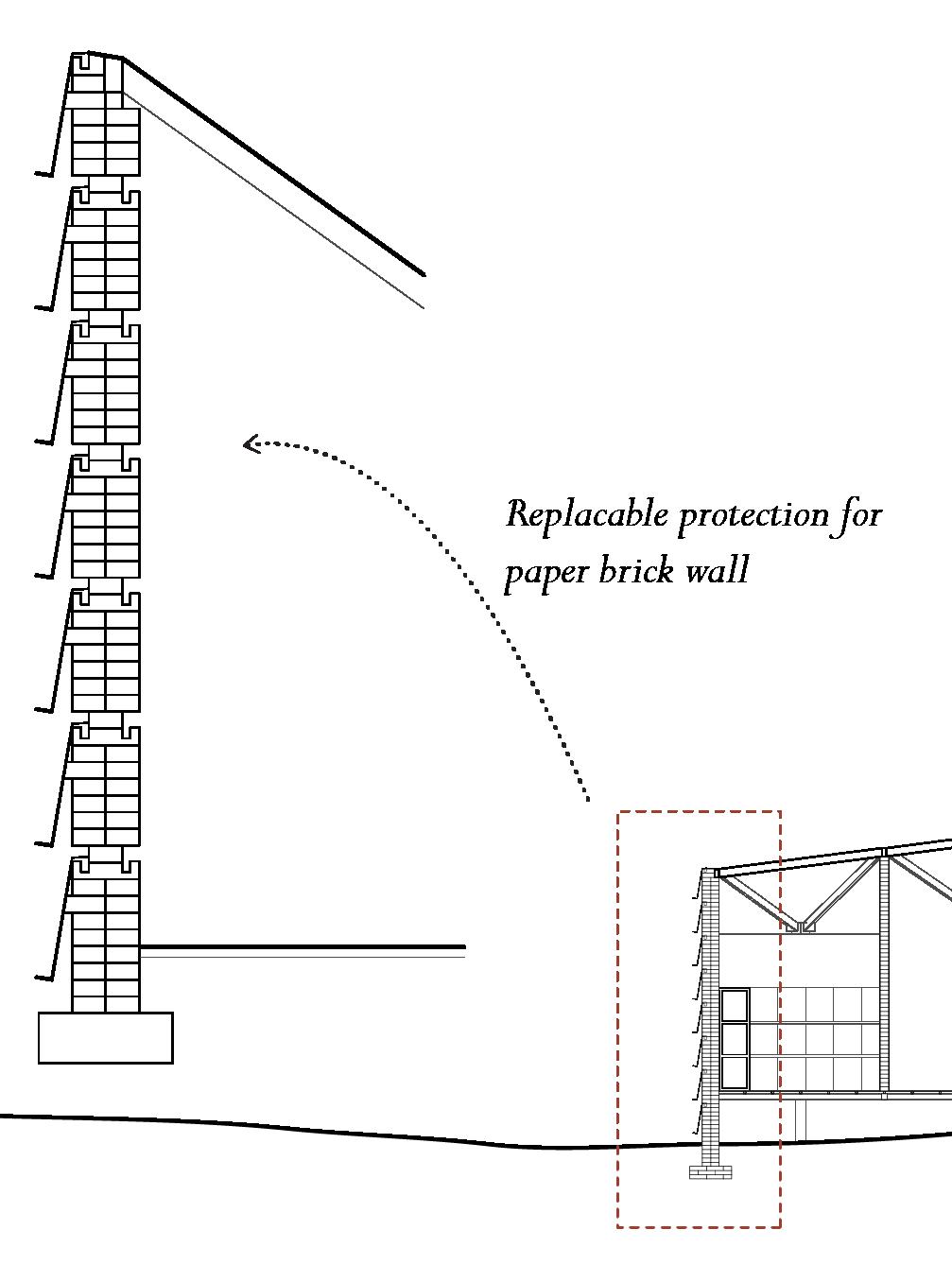

The section also highlights the canopies and protective screens as part of the water system. They guide the rainwater to the storage containers and provide shelter for people and the worms. They are made out of recycled paper (with wax treatment for waterproof) which can be reproduced and replaced within the structure.

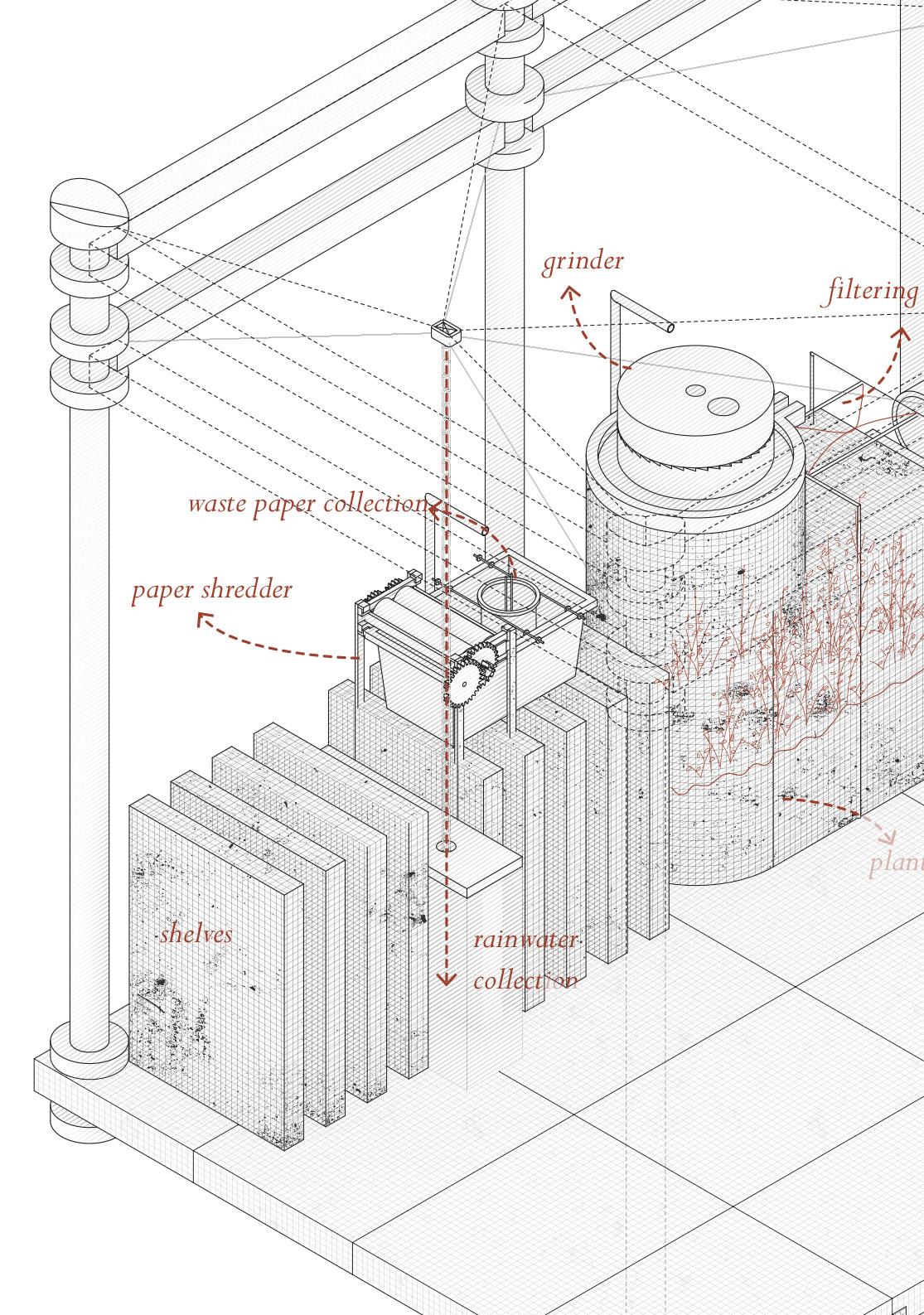

Recycling Module

The module integrates the paper recycling device with the shredder to collect waste paper from everyday use. The shelves are made of mesh and paper products which also provide support for the recycling device. Rainwater collected through the canopy is used to soak the recycled paper. The waste water goes to the planting pots.

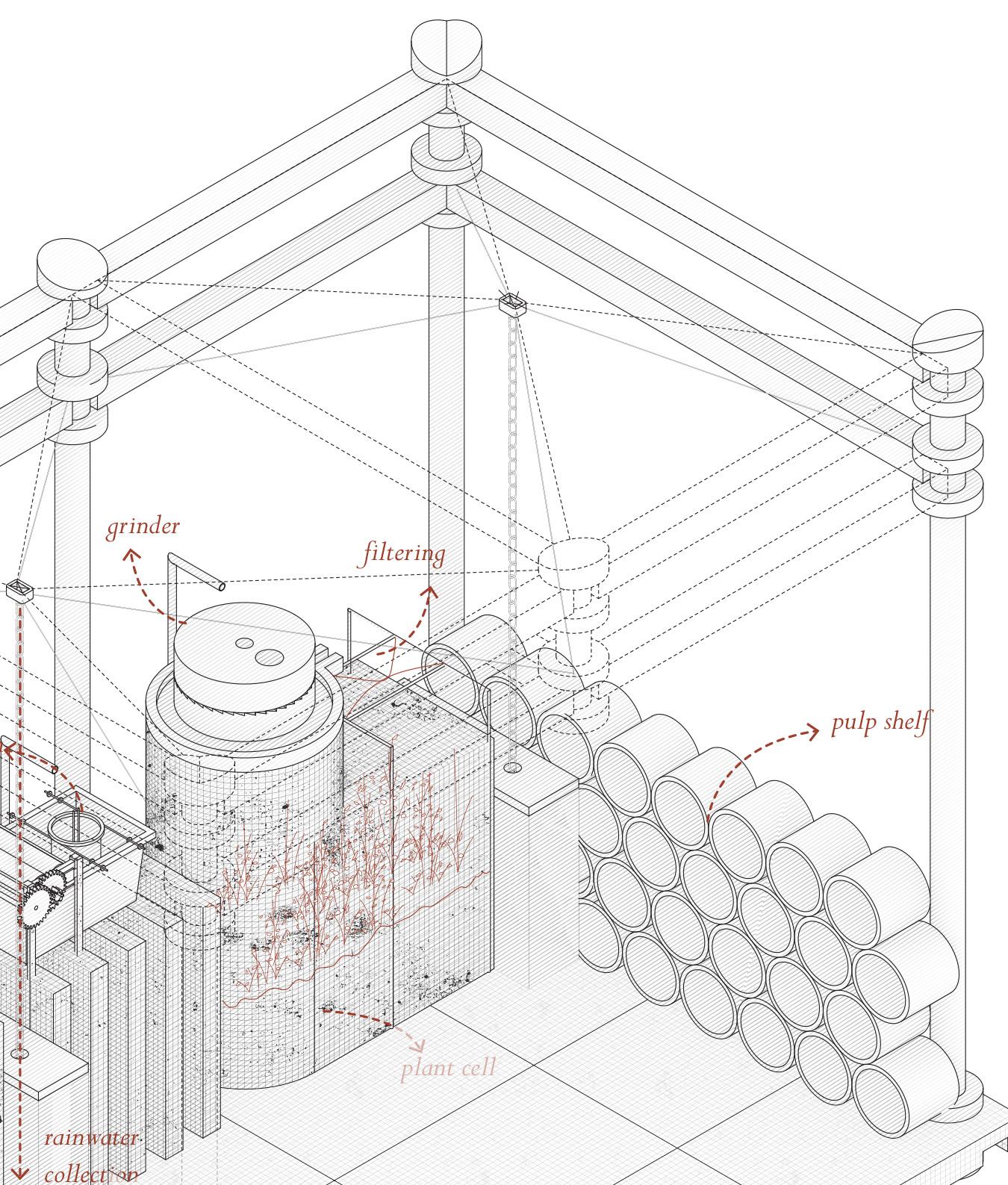

Grinding Module

The module contains a stone mill powered by a plant cell to break down the paper fibres. A steel frame standing beside the mill holds filter cloth to separate water and the fibres. The waste water irrigates the plants underneath which generates electricity to power the stone mill.

Papermaking Module

The module contains a sink which is essential in the sheet forming process. The furniture supporting the process are also made from paper which makes this structure producing its own replaceable components.

Papermaking Module

The module provides flat working surface for papermaking. different table heights suits the needs for both standing and sitting. (Seats are provided for crafting delicate objects as they take longer time to make.) The strings holding the canopy are also used as drying racks.

Wormbox Module

The idea of wormbox is kept as part of waste collection system. Located outside the extension, the wormbox requires shelter from direct sunlight and rain.

Elevation

The elevation shows the process of rainwater collection through the canopies and waste water drainage through chains and pots. They are made into flask shape to guide the water to appropriate places. This then becomes a main design language across different typologies.

The protective screens are made in the form of blinds which could be adjusted easily. The size of each blind is manageable to be remade and replaced on site when damaged.

The idea of the canopies comes from the intention of water collection while drawing the water sequence.

The sketch model helps to understand the spacial quality of the structure.

The stamps representing the repetitive canopies helps me to work with the layout.

Reception

Workshop 1: Sheets

Workshop 3: Furniture

Workshop 2: Small Objects

Built with materials from each household, the papermill consists of four workshops, each producing a different type of paper products. The workshops sit along the River Don to gain its hydro power. The greenhouse, at the same time, is a ‘power plant’ which grows the plant cells and provide electricity for the operation of the papermill.

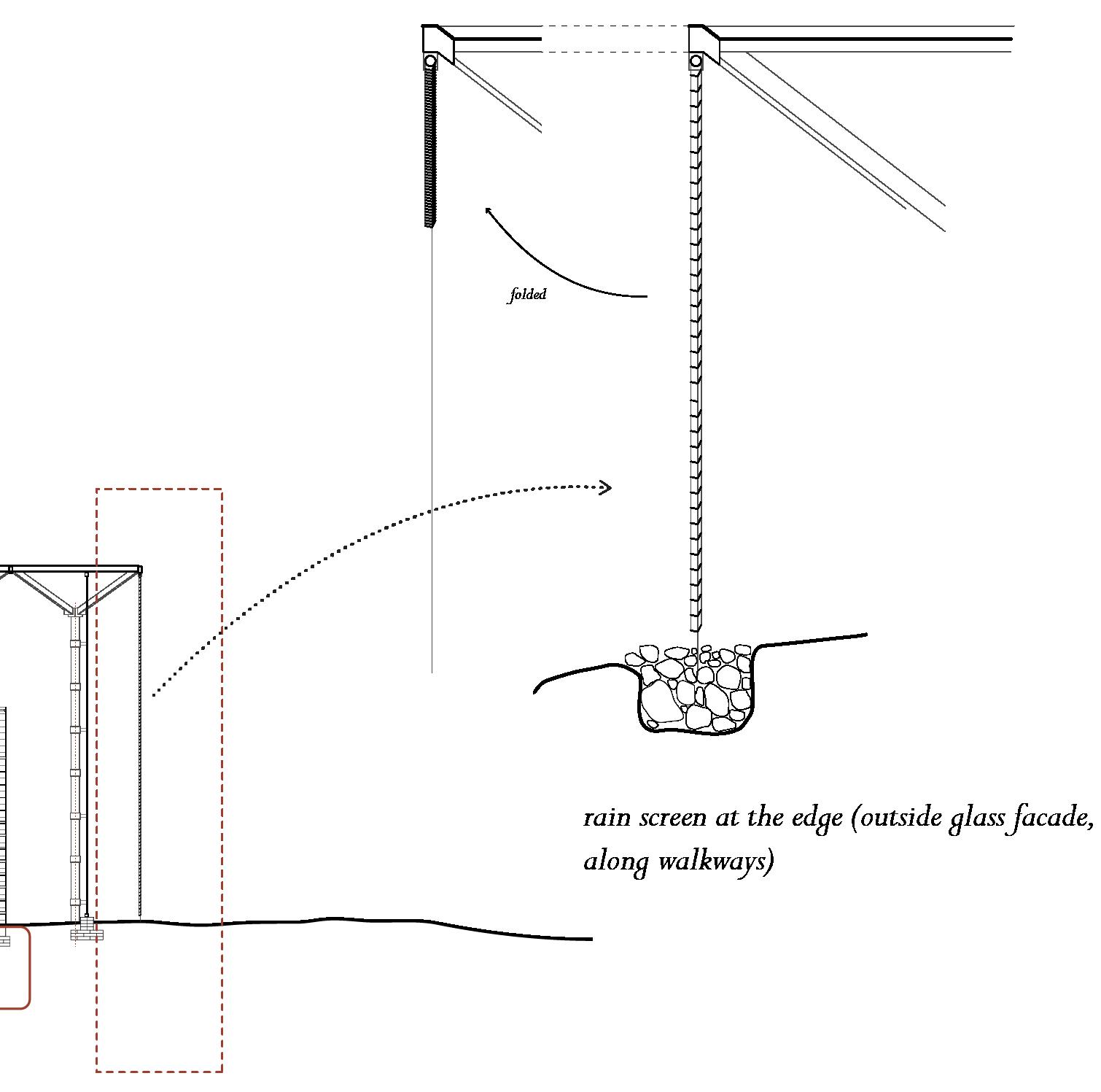

Workshop 4: Structural Elements Greenhouse

The water system is essential to this project. Rainwater collected through the canopies and columns are filtered and used in the papermaking process. The waste water produced goes to the irrigation system together with fertiliser produced from the worm boxes. Located underneath the workshops, the dampness provides wormboxes suitable conditions. Heat generated during the compost process are transferred to the greenhouse through water pump to keep warmth for the plants.

Apart from waxing the paper, I was looking for other solutions to minimise the weathering of paper structures. By adding another layer with replaceable elements, the structure can be repaired easily.

The rain screen provides shelter for the semi-exterior space. In the form of blinds, it could be adjusted easily to adapt different environmental conditions. The ‘v’ shape guides the water while protecting the walkway from the rain.

Papermill Water Sequence

Rainwater Filtration

Rain water collected through the canopy are filtered to remove large particles such as leaves and rubbles. The channels on the wall provides drainage and guides the rainwater through the filtration process.

The containers are made into modules to be fixed on the paperbrick wall. Rainwater would go through each container to be filtered for future use.

Waste Collection

Underneath the sink is a waste collection device. Unused pulp can be collected and recycled through the filter cloth. Waste or failed pieces of paper during the production are collected in the device to be recycled.

Rainwater Collection

The hollow section of columns allows drainage and guides rainwater to the container.

The columns are held into place and stablised by rubbles to minimise impact to the ground. These rubbles are collected from the excavations and wastes from construction sites near by.

The workshop offers space and facilities for papermaking. The water produced during the process penetrates through the mesh floor, being absorbed by the soil underneath and going back to the natural cycle.

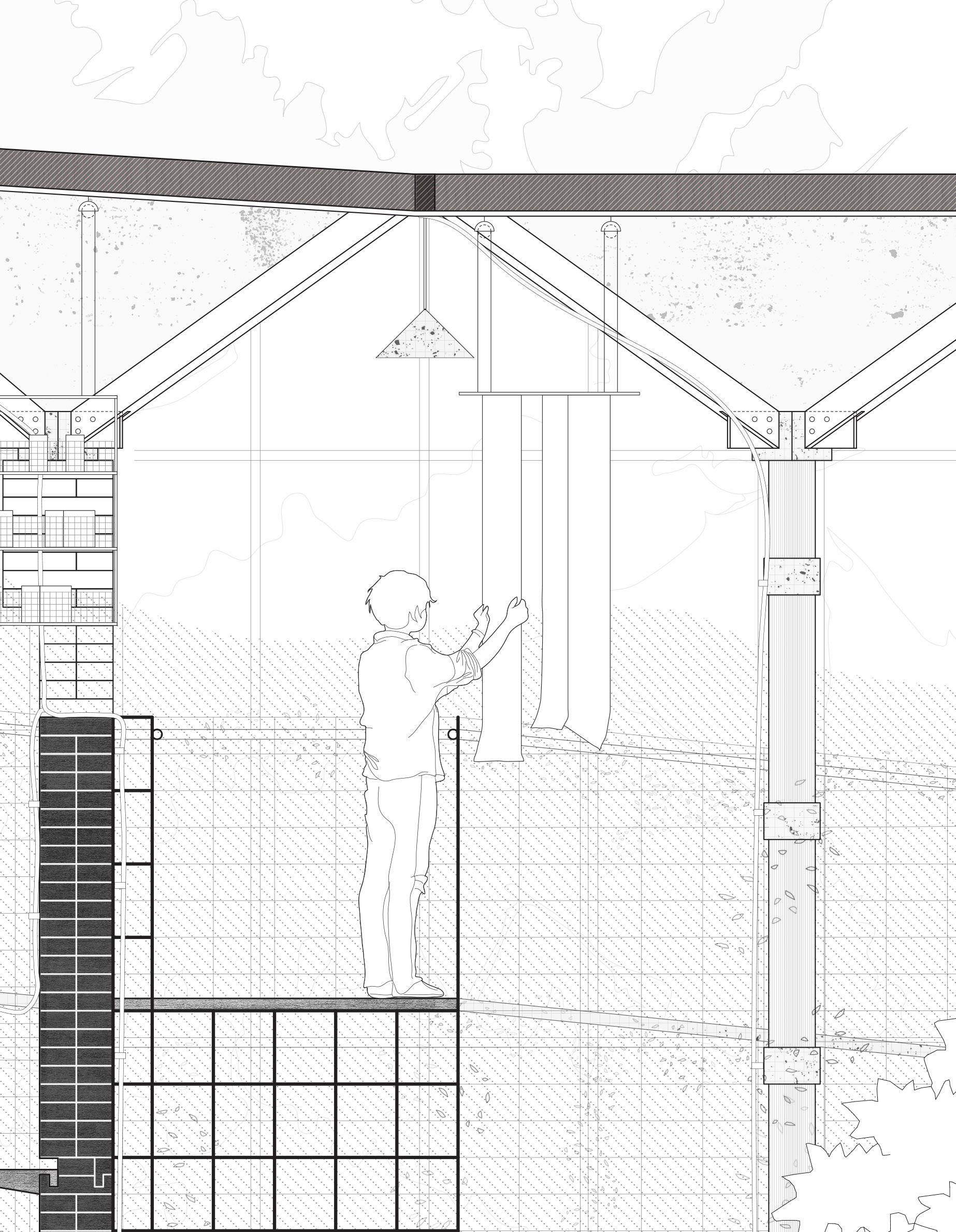

Putting up the wet objects for drying. The drying racks transports the wet objects to the greenhouse where has higher temperature and the water dripping would not affect other work in progress.

The height of the structure offers sufficient space for growing plants. The elevated walkway allows people to operate the hanging objects without the disturbance of the branches.

The plant cells buried in the ground provide electricity for the papermill. A staff keeps monitoring the conditions of the cells and replace the plants when necessary.

The mesh supports the walkway, at the same time, becomes shelves for potted plants. These plant cells could be transported to other places to support the energy grid. The greenhouse in the post-petroleum world becomes a power bank.

Storage and Packaging

Following the collaborative sequence, the paper products are then sold to other places in the city, starting from the printmaking industries. Paper stations are established as transitioning space, connecting the papermaking to other programmes. The diagram shows the possible combination of papermaking modules outside the printmaking workshop.

Products provided for workshops and galleries

The map shows the locations of art galleries and workshops in Aberdeen where the first group of paper stations could be located, providing paper products for art projects.

REFLECTION

From Industrial Production to Handcrafted Care

Paperscape is based on the assumptions built on post-petroleum scenarios, aiming to redefine architecture as a support structure. Following the four elements of support structure –resource, sequence, construction and inhabitation, the project tries to recognise the impact of design decisions on individuals, communities, and wider context. By questioning the pervasive influence of petrocultures – driven by speed, consumerism, and individualism – the ‘support’ begins with structural elements and gradually develops into systems facilitating alternative futures.

The working methodologies in Paperscape connect the tasks non-chronologically, each intersecting to form a cohesive narrative. Working closely with fictions to approach realities, the project raises assumptions to be tested, refined, and grounded. Characters like an earthworm and a mud engineer provide unusual and ‘pluriversal’ perspectives, connecting the story and grounding the design in real-world contexts.

Making and experimenting are core methodologies employed in Paperscape, complementing the ‘fictional’ assumptions. The decisions are informed and tested by exploration and contextual understanding, guiding the development of the ‘support’. This approach explores new potentials of paper as a three-dimensional material, providing possible solutions for a post-petroleum world. Focusing on papermaking process, the project introduces new approaches to adapt the traditional papermaking industry in a post petroleum context and transform the industrial production into handcrafting process, in which the communal care becomes a part of the support system.

Karami, Sepideh, and Naomi De Barr. Architecture as Support Structure: How to Construct a Post-Petroleum World, Project Brief 1, Edinburgh School of Architecture & Landscape Architecture, September 2023.

Karami, Sepideh, and Naomi De Barr. Architecture as Support Structure: How to Construct a Post-Petroleum World, Project Brief 2, Edinburgh School of Architecture & Landscape Architecture, January 2024.

Harmon, Katharine. The Map as Art: Contemporary Artists Explore Cartography. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009.

Doric Columns: The History & Heritage of the City of Aberdeen, 'Paper Mills in Aberdeen'. https://doriccolumns.wordpress.com/ industry/papermills/.

Doucet, Isabelle. "Chapter 2 Architectural Storytelling: A Space between Critical Practice and Fragile Environments" In Infrastructural Love: Caring for Our Architectural Support Systems edited by Hélène Frichot, Adrià Carbonell, Hannes Frykholm and Sepideh Karami, 36-53. Berlin, Boston: Birkhäuser, 2022.

Belanger, Pierre. Landscape as Infrastructure: a Base Primer. New York: Routledge, 2017.

All images are author's own unless stated.