CPJ Spring 2025

Non-Fiction

Non-Fiction

Baguette Rinds by Phoebe Last ‘25

Where are My Keys? by Jamie Park ‘26

Home by Eliana Rosner ‘25

Plants and Toddlers by Aimee Wan ‘26

Mike’s Yellow Cab Management by James Dorazio ‘26

Fiction

My Bad by Eliana Rosner ‘25

Home to Sterhom by Phoebe Last ‘25

Lone Camping by Madison Cho ‘26

Losing Light by Bella Pass ‘27

Mrs. Lister by Phoebe Last ‘25

The Girl... by Savannah Vega ‘26

The Layered Haircut by Phoebe Last ‘25

Schools & ... by CPJ staff

Cookie Review by Olivia Loose Levin ‘26, Sami Venokur ‘26 and CPJ staff

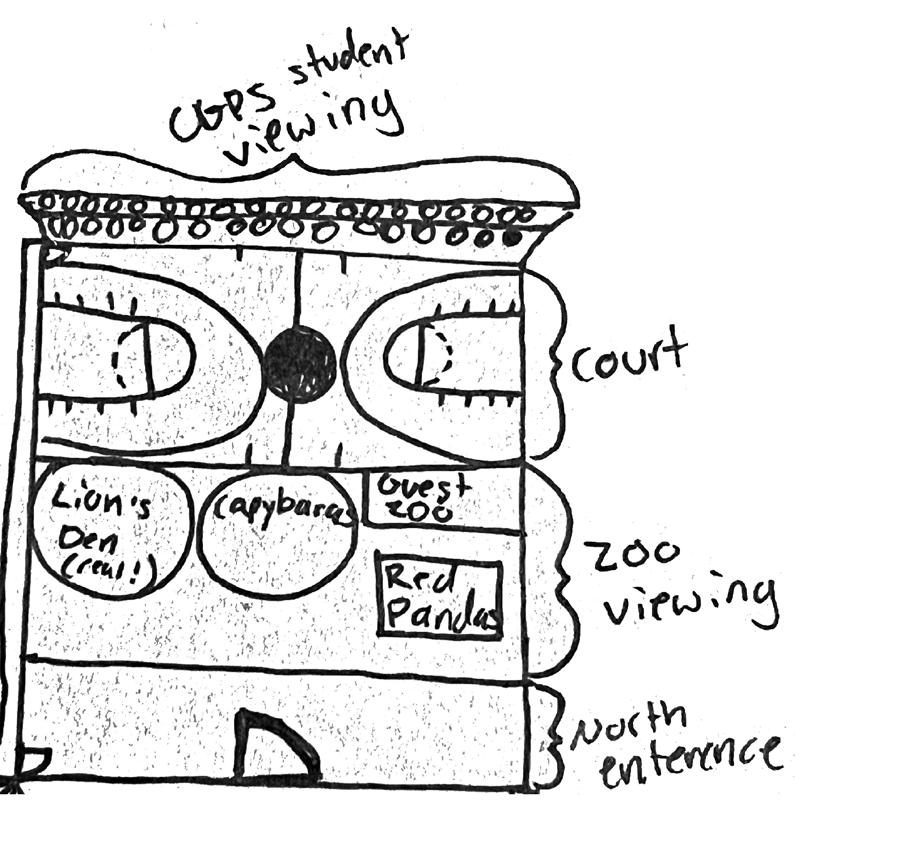

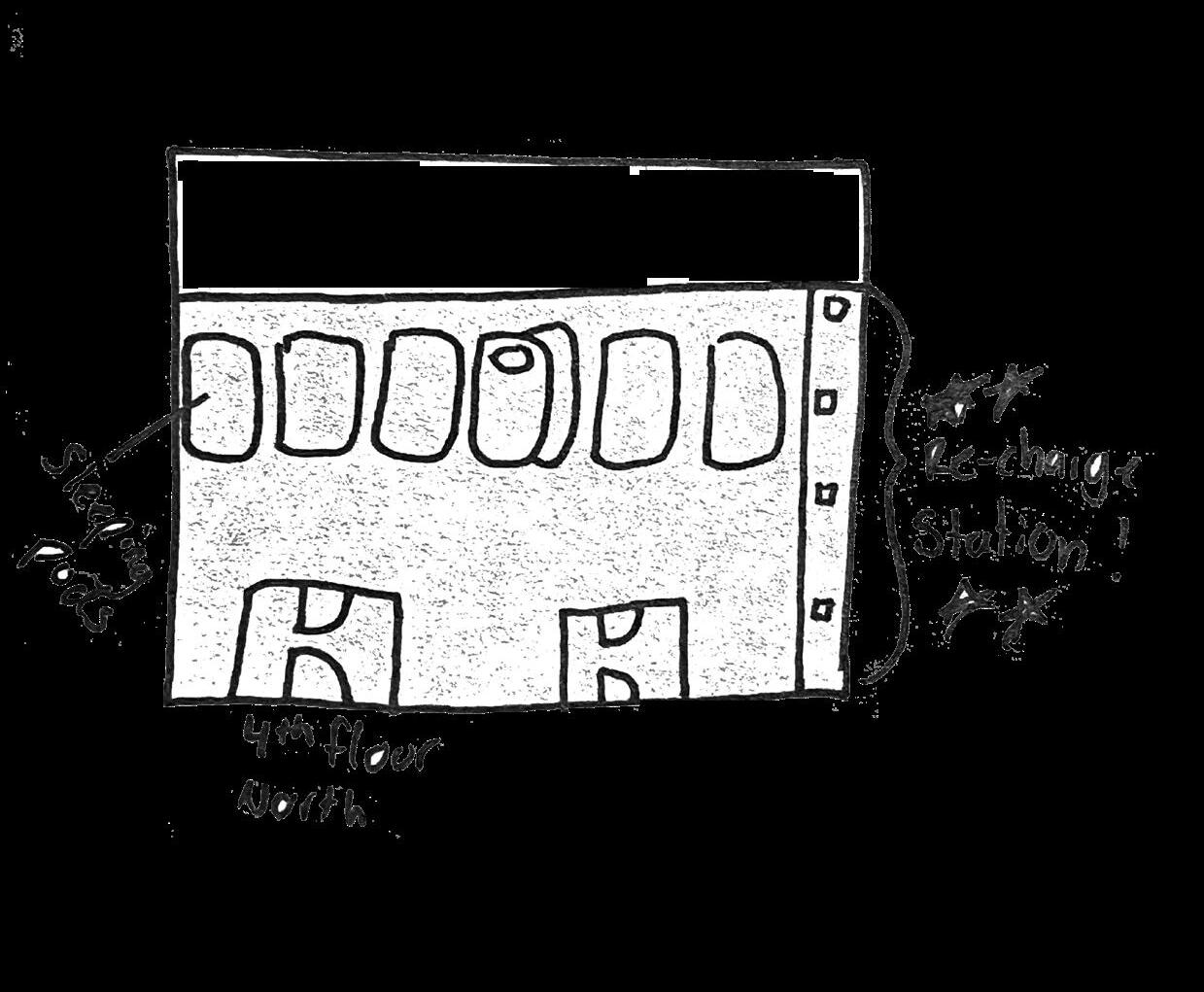

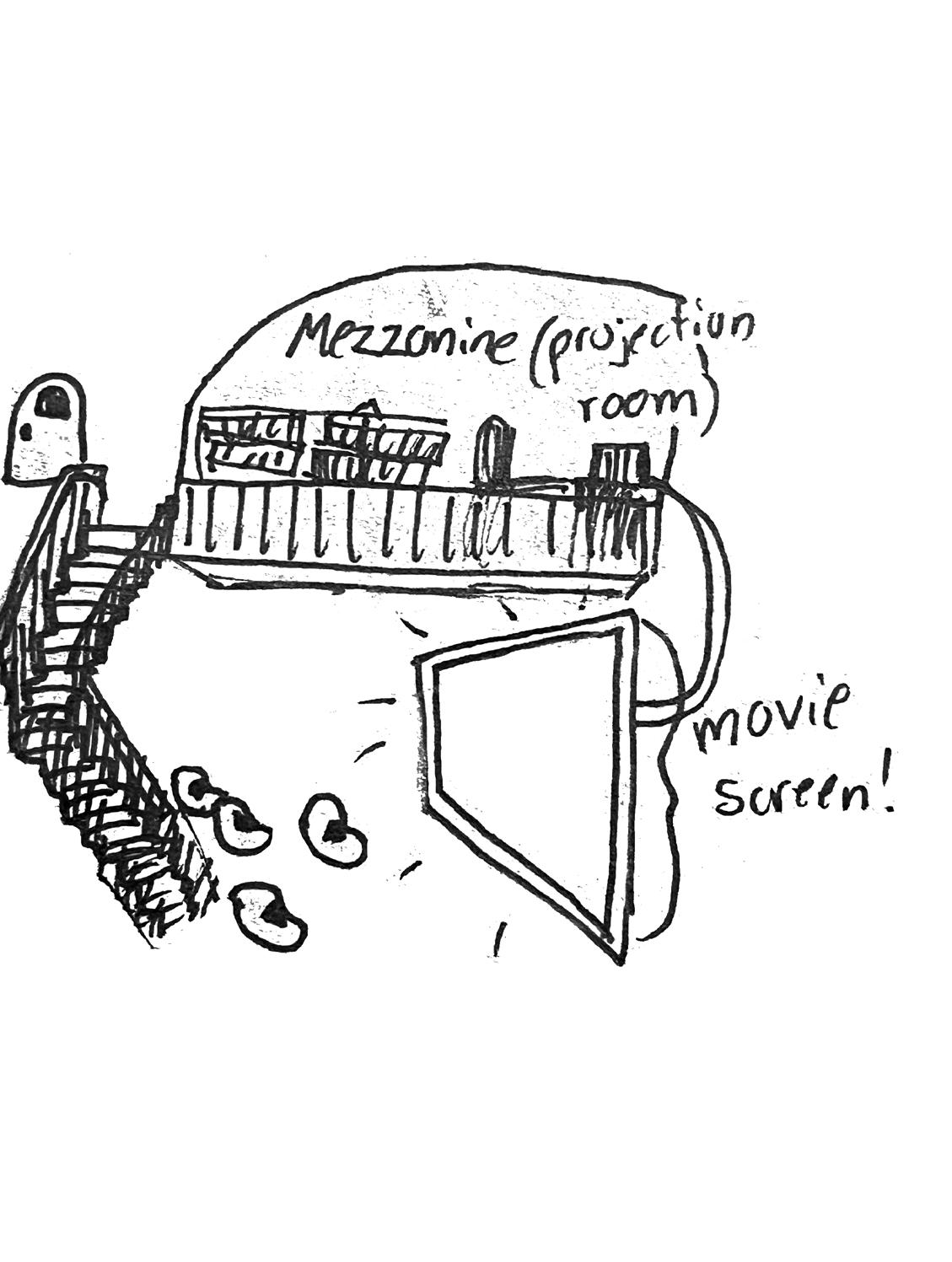

CPJ Dreams Up CGPS Renovations by CPJ staff

Poetry

Seven Ways by Sara Elbaum ‘25

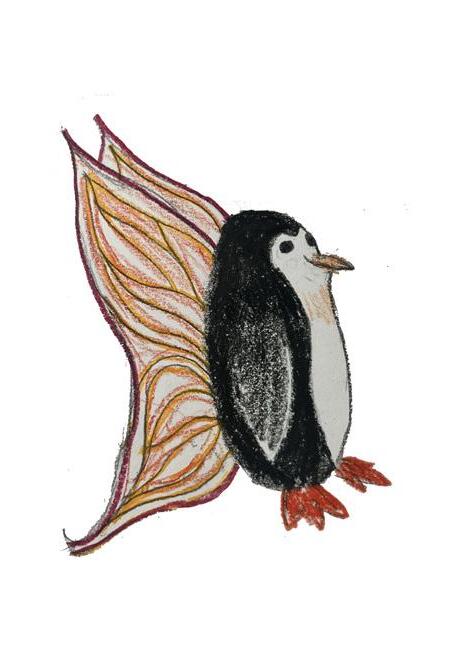

Fairy Penguin by Sara Elbaum ‘25

Last Drop by Olivia Woloz ‘25

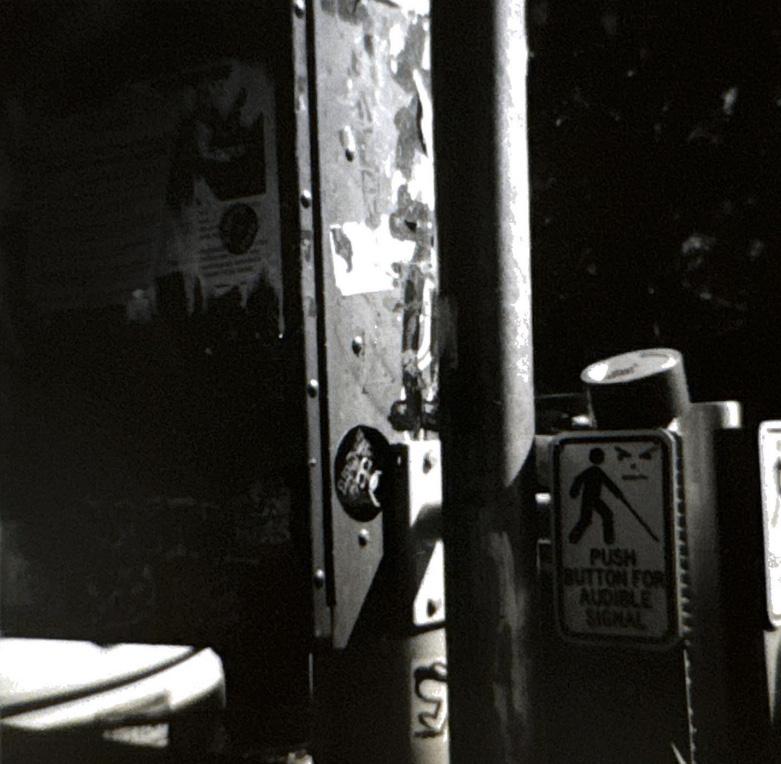

Underground Music by Savannah Vega ‘26

Fragrance by Savannah Vega ‘26

A Mother’s Advice by Cianna Berroa ‘26

Editoral Board

Sara Elbaum ‘25, Phoebe Last ‘25, Eliana Rosner ‘25

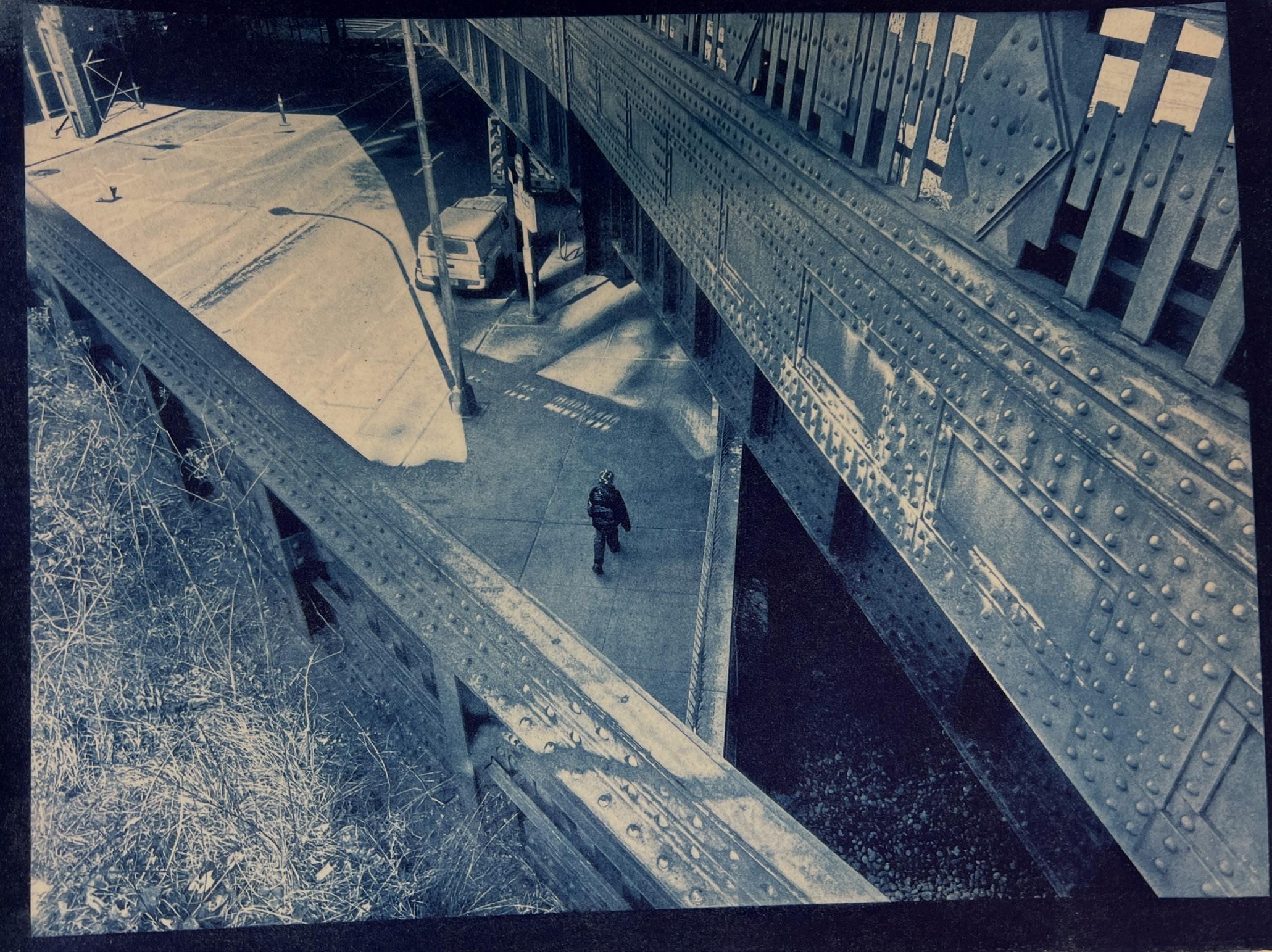

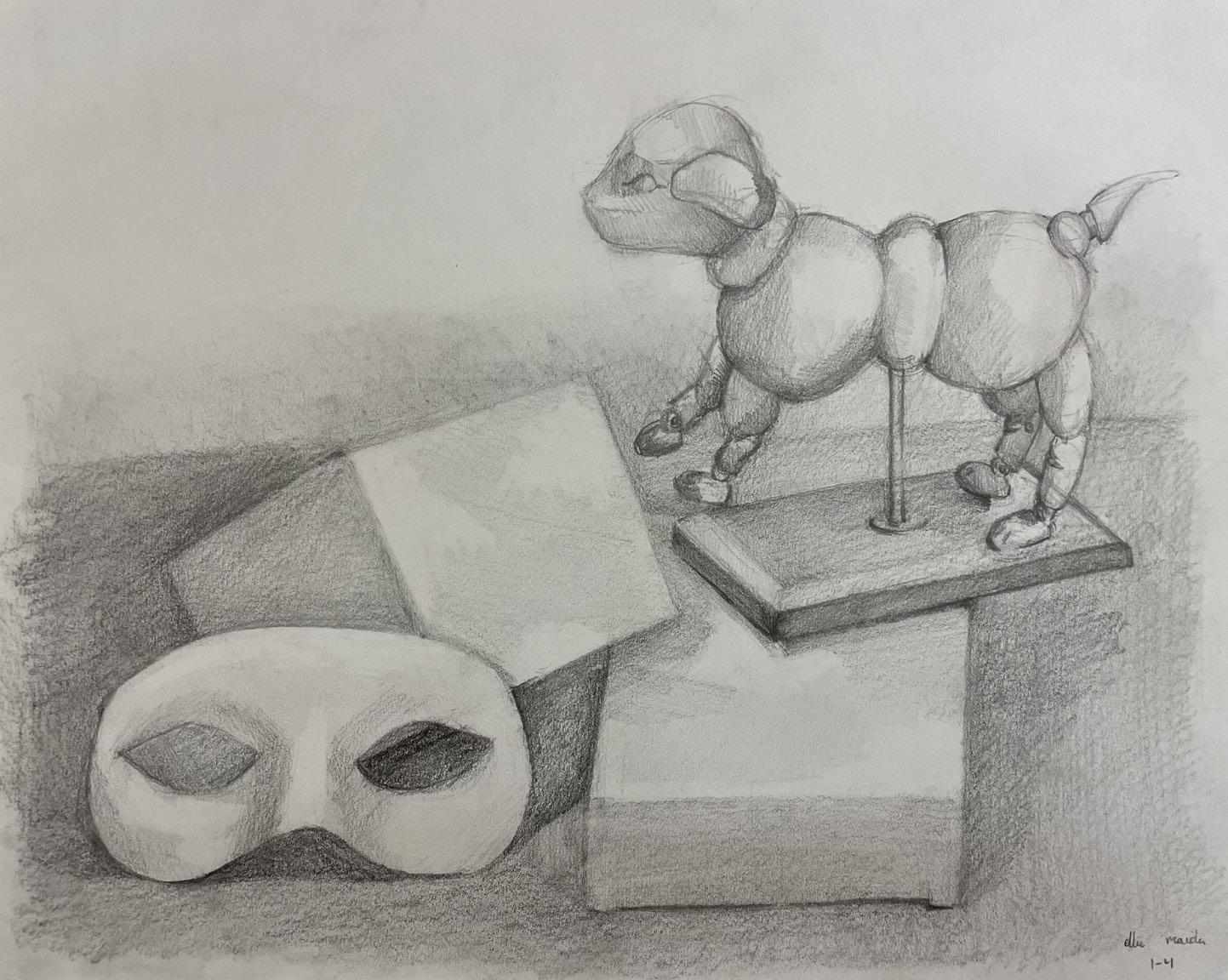

Artistic Contributitors

Eli Banyasz ‘25, Sara Elbaum ‘25, Skai Estimé ‘25, Justin Fradkin ‘25, Phoebe Last ‘25, Simone McLetchie ‘25, Sarah Perez ‘25, Hannah Zack ‘25, Cianna Berroa ‘26, James Dorazio ‘26, Anker Ford ‘26, Lav Grmusa ‘26, Habiba Mansour ‘26, Isabella Tang ‘26, Blake Bebon ‘27, Charlotte Birkenhead ‘27, Damon Karabelas ‘27, Steve Kim ‘27, Ellie Maida ‘28, Lila Peller ‘28

Advisor

Mr. Cramer

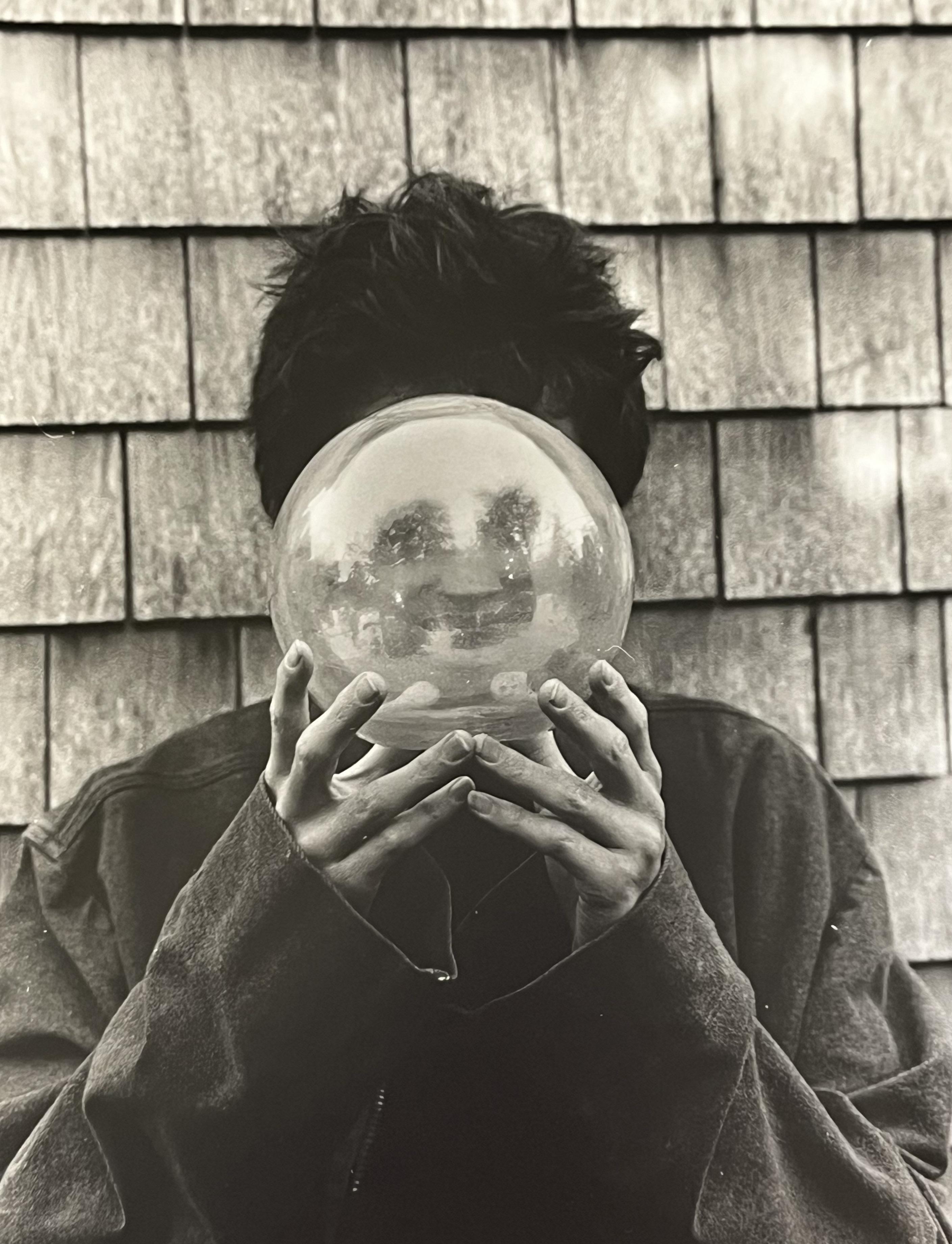

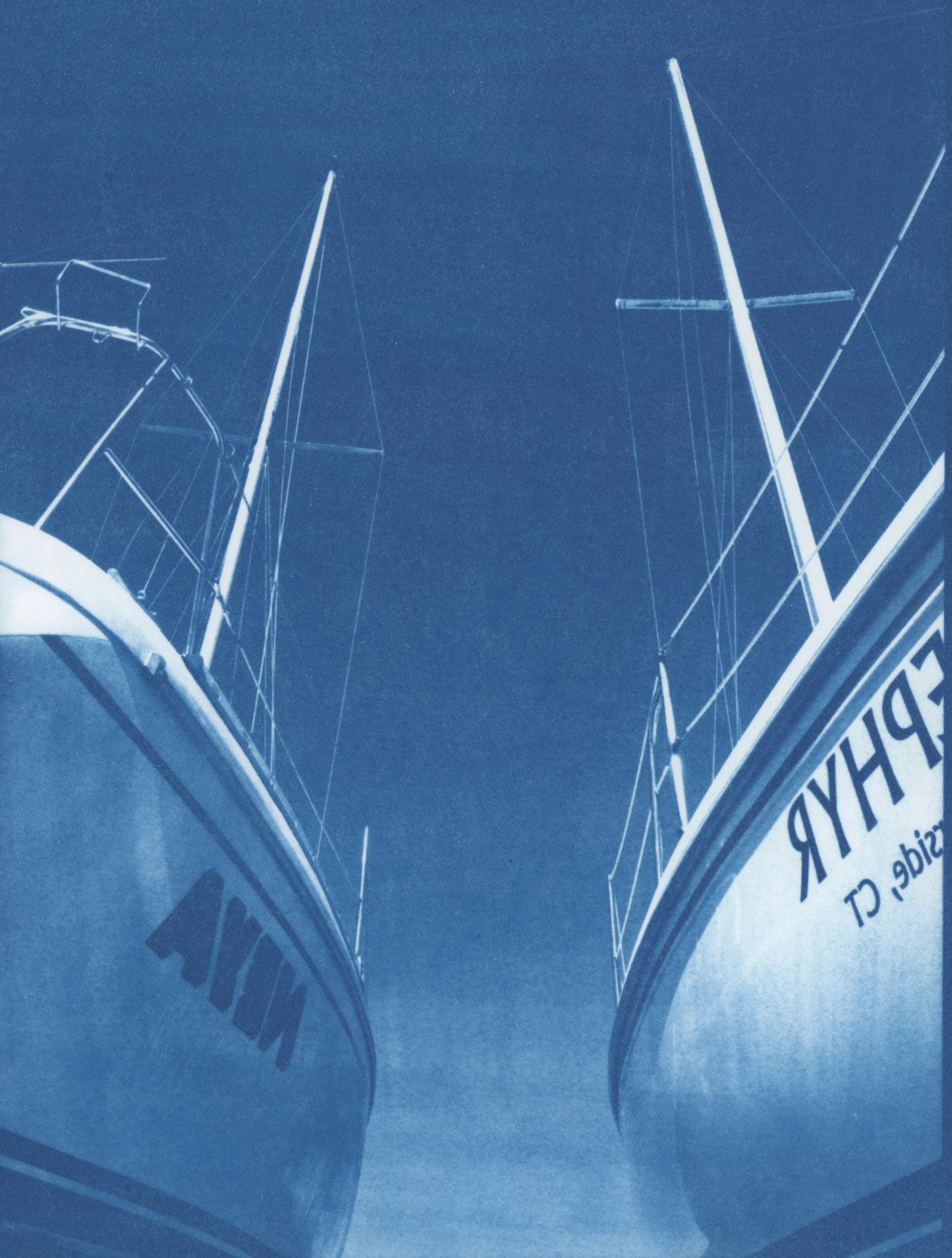

Front Cover

Phoebe Last

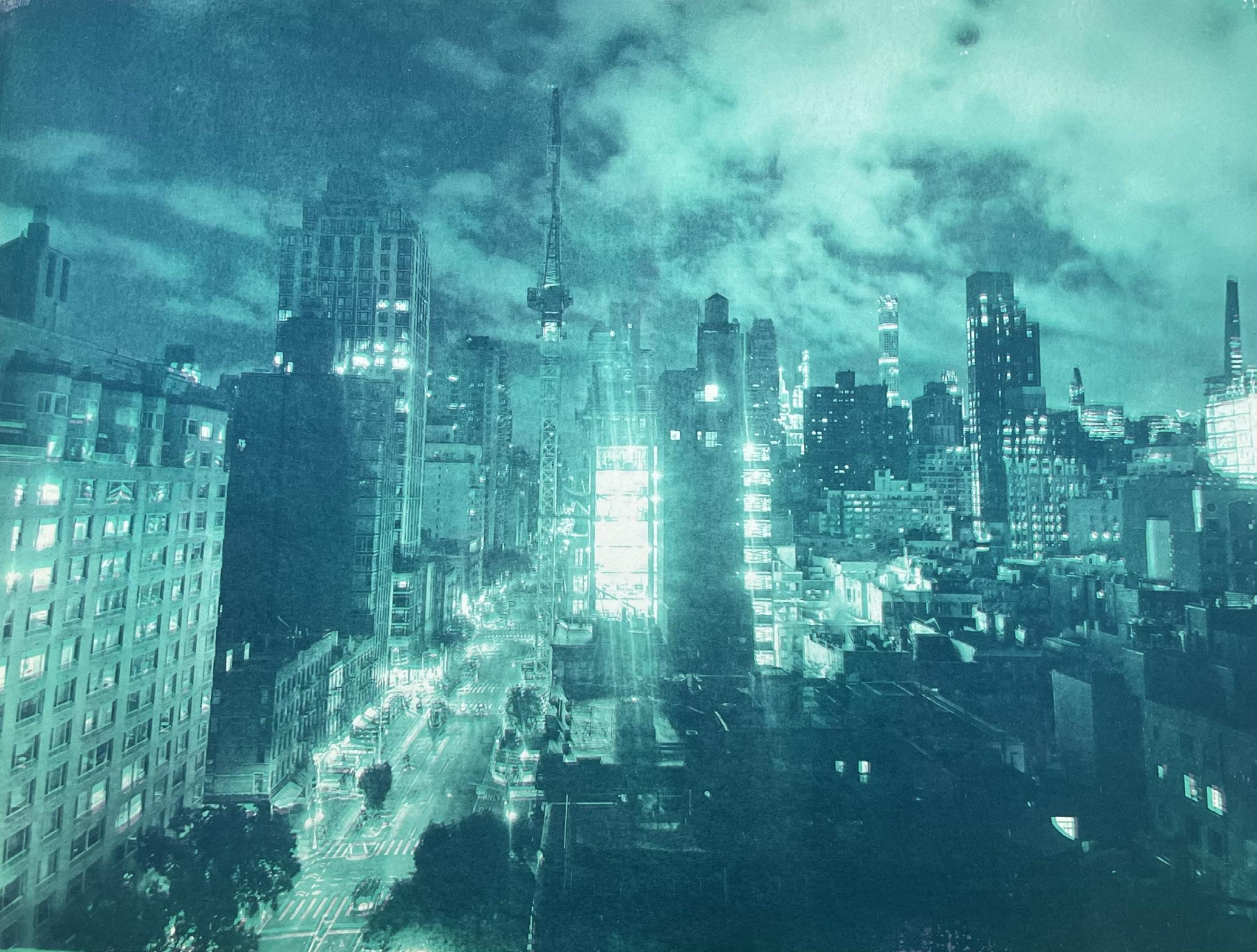

Back Cover

Sara Elbaum

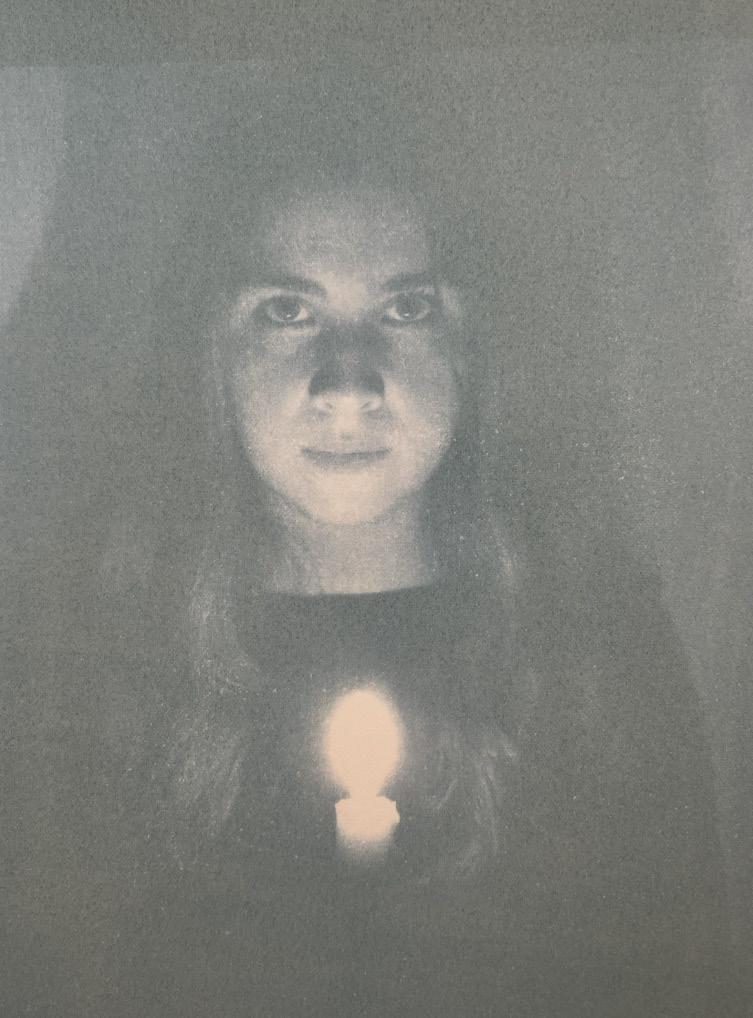

By Phoebe Last ‘25

The sun streamed in through the crack in the window far above my head. My seatbelt restricted me to my orange and black booster seat. We were having pea soup that summer evening, so my dad had just picked up a fresh baguette from Silver Moon Bakery. The bag was placed under my dangling feet, on the backseat floor, the baguette sticking out of its plastic and brown paper wrapping.

The car was double parked outside of Barzinis, a local grocery store. “I’ll leave the keys but please don’t drive off,” he said jokingly as he got out of the car. I remained in my restraint with the setting sun still partially blinding me.

I wasn’t sure how long had gone by before I began to get restless. I was watching a group of pigeons flutter and flap their bodies out of the way of nearby cars driving down Broadway. The smell of the warm bread that wafted up from the floor of the backseat made my stomach growl. I reached my little arms over my knees, down towards the origin of the mouth watering aura. My fingers grazed the brown paper and plastic wrapping before the seat belt locked around my middle. I was jolted back, but I wouldn’t give up just yet.

I ducked under my seatbelt, freeing my torso, allowing me to curve down towards the bag. I curled my little fingers around the top of the baguette and peeled the end off, exposing the fluffy middle inside. I pinched a piece of the white bread between my two fingers and ripped. The texture felt like lace as it melted on my tongue. I had to have another bite. This time, I grab a handful of bread, only the white middle, leaving the shell of the baguette holding its shape. This ravenous cycle continued, my fingertips

scooping up chunks of bread, scraping the baguette skin, condensing the white middle into doughy balls that would then get stuffed into my mouth, nourishing my void of a stomach. I continued carving out the baguette until my index finger hit the stump end of the bread. I leaned back, letting the crumbs settle on my orange and black booster seat. My eyes fluttered, satisfied with my creative indulgence.

My doze was interrupted by the sudden opening of the trunk. My dad was back from Barzinis. He loaded overflowing bags of groceries into the back. Getting into the drivers seat, he looked back at me in my orange and black booster seat. “All good Bee?” He asked. I brushed a breadcrumb from my cheek and beamed back at him. His gaze shifted to the bag near my feet and his brow furrowed for a moment before breaking out into a hearty laugh as he pulled the item out of the bag. All that was left in his hand was the baguette skin, the crisp outside standing strong as the ghost of the middle settled in my full stomach. That evening, our pea soup was accompanied by the exclusive dish of baguette rind. I would highly recommend the next time you make pea soup to serve it with a side of baguette rind. I promise it’s delicious.

By Jamie Park ‘26

There’s something peculiarly dignified in the art of losing things. One first instinctively pats one’s pockets and hopefully rummages through bags, but soon spirals wildly into mental frenzies of retracing steps through a fog of half-formed memories and blurred impressions. A whispered plea tumbles out as if the universe itself might take damnable pity and return what’s gone missing. To date, this misplacing happens with such regularity that I almost suspect there might well be a lesson buried beneath it all. And it’s always the keys that end up setting me free. My wallet and AirPods do like to join in on occasion, but my keys—ah, they’re the Houdinis among ordinary objects, disappearing when I need them most.

I especially remember one morning when this pattern went from just being an annoyance to something more. Running late, it wasn’t until I reached for the door that the realization finally hit—my keys were nowhere to be found. A wave of frustration swept over me as I tore through the house. I turned the living room upside down, my backpack inside out, flipping cushions, switching cushions, rifling through

the kitchen cabinets, every surface scanned. In one last, desperate moment, I even opened the freezer. By then, reason had given way completely to raw hope, a silent prayer that the keys might materialize somewhere ridiculous. Kneeling on the floor, feeling the chill of the kitchen tile seep through my patella to my femur, baby-crawling to the carpet, catching a faint scent of my mother’s favorite Jo Malone blackberry candle where it had melted into the rug fibers—there was an incident two years back, when my sister jabbed the candle burning on the coffee table in a fight over the TV remote—and reaching under the couch finally, I caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror nearby. My face was flushed, my hair was askew, and my eyes were wide with something close to desperation. The funny kind of secondhand embarrassment washed over me that we feel when we see ourselves behaving as though the whole world hinges on something trivial. And in that moment, hunkered down on the floor of my bedroom, it belatedly dawned on me: it was never about the keys. It was about my cool, my balance, my willingness to let go. And curiously, in that realization, I felt a kind of clarity—an absurd, almost beautiful kind of clarity. And that was when I realized that the act of losing specifically possesses an unobtrusive beauty within itself, thereby compelling us to confront blind spots in our everyday life.

This is because when one loses something, well, it is not just a question of inconvenience. It makes one stop and pay attention. Because I ask myself every time I lose something, do I remember where I put things? And deeper still, do I remember where I am in my life?

Take, for example, a moment that single-handedly made me realize I had to, as my sister says, “Get

your s**t together Jamie.” One January evening, I was on the wrong side of my own front door. I had just come home from school in an Uber and began to pat down my pockets. Front right pocket, front left pocket, back left pocket, back right pocket, right side pocket, left side pocket, so on, and so forth (cargo pants were trending back then). No keys. No problem. I rummaged through my backpack because where else would they be? There I stood, shaking a bit, unzipping my backpack with more confidence than I deserved, because the more things I pulled out, the more I started realizing my keys were not as “definitely” there as I’d thought.

Then I started taking out my life’s clutter one by one: my binder, then my laptop, my English notebook, my Biology notebook, my Spanish notebook, my Everything notebook (a combination of Geometry and U.S History, but mainly in-class doodles). Now, this could have been avoided if I had a designated area for my keys. However, I just throw them in with all the rest and let them fight it out over night. I pulled each item out with increasing desperation, my hands numb and my heart racing as my pile of stuff was growing on the front steps. And then, with my now-empty rucksack hanging open, I tried to retrace my steps because maybe it fell out on the 10-foot walk from the Uber to my front door (it didn’t). That’s when it finally clicked

into place. You F’d up Jamie. In desperation, I even shook my backpack hoping that somehow, some way my keys would magically fall out, (but all that fell out were miscellaneous Goldfish and Cheezit crumbs and eraser bits).

So, heart racing, I finally went for my phone to call either my parents or—Heaven forbid—my sister, and found—of course—that my phone was dead. It seemed an entire Uber ride spent mindlessly scrolling on Instagram Reels had sucked the battery dry. Truly stranded now, I did the only thing that any sensible person would do: I attempted to break into my own home. I jiggled the doorknob. I tried lifting a window. I even scanned for any possible loose bricks I might pry away for a secret spare key. All of it, of course, was entirely useless. I finally relented and plopped myself down onto the front steps, staring blankly ahead, hoping somehow a miracle would occur and my keys would appear in my hand.

A miracle did occur. It began to snow. The first snow of the season. Light flurries at first, growing thicker as they drifted down all around me while I sat there like a stranded Barbie doll, my joints locking up cold and fingers practically freezing into little icicles as I huddled, waiting for someone, anyone to finally come home and rescue me from my tragic lack of planning.

But in this ashamement (a word I created for the feeling I often inspire), I started to notice beautiful things: how still a street could be that I never paused to see, and how I could have only seen the light evening snowfall if I had paid close attention to the street light pole and how the light procured the snowflakes, and how I was finally the first one to print my feet onto the newly fallen snow. And by the time my mom’s car finally pulled up, I hadn’t just found relief—I’d found something else, too. A strange gratitude for the simplicity of just being still. And at that moment, for all that I’d lost, a part of me felt that I had gained.

Maybe it’s not about what is lost but a subtle cue, that zen-like nudge of the universe to notice the present, to care enough to see. Or perhaps, it’s a cosmic challenge, a tease, inviting us to lighten our hold on order and reminding us that the most tightly held things are often those that slip away first. In a way, I think I have begun to believe that there is a part of me that loses things on purpose, which is unconsciously open to the momentary mess. There’s this strange, almost poetic excitement in the hunt, the small spurt of alive-ness within the disruption. Each hunt extricates me from the daily grind and forces me to reassess the minutest details of my day, the corners of my home, and the pockets of my memory. A thing very close to what is sacred is that, with each new search, surroundings are standing before me afresh. The moments when I am retracing my steps often turn out to be those moments of paying more attention to the things that hadn’t caught my eye so far; an idea that even to lose, in its own silent way, is a sort of gift, to look more carefully, to reconsider, to allow the familiar daily landscape to reveal itself anew.

Sometimes, I think life itself is like this eternallooking-for-lost-keys thing. We fumble through our days tracing and retracing our steps, holding onto the hope that if we continue searching, we might stumble upon that clarity or purpose that we feel is misplaced. In those moments, I wonder if the loss of my keys is

some kind of small reflection of the big losses we face in life: the quiet gnawing space left behind when people move away. We lose friends, family, lovers, and like keys, they leave us: not at where we last saw them but at places we least expect to go looking. Perhaps, a part of us is always searching, not for objects, but for people we have lost and loved, and the memory of all that might bring them back. We tell ourselves that one day, we’ll make our way without stopping to check that we haven’t forgotten something, without looking back. But perhaps this is the illusion. Perhaps what life is about is this slight messiness.

Perhaps in our infinite seeking, with each passing day, we’re destined to recover this world, a little less certain, a little more amazed. Of course, that morning I did find my keys, lying openly on the corner of my desk, as if they had never been moved at all. And in that moment, I knew I would lose them again—because there’s no end to the art of losing things. In each lost and found object is an invitation to pause, to laugh at our seriousness, and remind ourselves that not everything in life can or should be managed. In each instant of search, an opportunity to get back into our lives with fresh eyes. And strangely, beautifully, I wouldn’t want it any other way.

By Eliana Rosner ‘25

The banging sound of pots and pans crashing to the floor made me lurch upright. It was undoubtedly my grandmother, off creating havoc in the kitchen in her typical endearing–though slightly frightening–evil house-elf manner.

My eyelids felt like heavy weights, but I willed myself to keep them open. Middle-school final exams were on, though our house had been plagued by a blackout for nearly half a week. Banishing that looming thought, I fumbled for a flashlight. I must have dropped it in my sleep. The storage closet was dark and humid, smelling heavily of Grandma’s floral perfume.

Never before had I imagined that I would be studying in my grandmother’s storage closet. Yet after the virus that shook the world, everything seemed different. For one, my parents and I had fled New York

City to move in with my grandmother, aunt, and cousin.

Grandma’s house was small, white, and disheveled. Sometimes I would lay awake at night, hearing crickets chirping outside my window, while trying to recall the honking of the city, the blaring sirens and yelling street vendors. Sometimes I shuddered, wondering if I would one day forget those sounds. My grandmother’s house was near the end of a winding country road, dwarfed by nearby trees and woods. Yet despite the isolation, I was never bored. My grandmother, Blanche Rosner (“Dr. Bunnie” to her patients), was a constant spectacle.

She was small at 4”11 and 80 pounds, with stiletto heels, bold eyeshadow, flashy clothes that resembled something between 1970s disco dancer and punk-rock star, and a bright, blonde wig that either

looked, or was from, the 1960s but with curled bangs in front.

The sound of clicking heels grew loud, and I knew it was Bunnie even before her sparkly claws creaked open the door.

“Ellie, what are you doing in here?”

“Studying,” I answered with as much patience as three hours of sleep could give me. Her eyes widened in alarm, and it took several attempts to clarify that I was not “muddying” nor “bloodying,” two out of many false interpretations she misheard. Upon finally understanding, my grandma smiled.

“Sweetie, you don’t need to study. Just dye your hair blonde and you’ll be fine.” She laughed, leaving the door open.

I sighed as her heels clicked away into the distance. Somehow, Bunnie believed that transforming into Marilyn Monroe would solve any girl’s life problems. I loved her, though. Picking up my pencil, I resumed cramming for my physics exam. This week of torment, studying in a storage closet by flashlight during this seemingly endless blackout, would indeed soon be over.

Fortunately, it was the night before my last final exam. I lay down on the pullout couch that doubled as my grandmother’s psychology office where she gave questionable advice to patients earlier that day. In fact, she had told one patient to stop speaking with his daughter, who kept nagging him to go to the doctor from worry over his health, yet to stay in touch with his equally concerned son.

“You’re crazy!” she had shouted at another patient through the telephone, her usual delayed response upon reading and mouthing its electronic captions for nearly half a minute.

Remembering these events, I tossed restlessly, despite my exhaustion. However, feeling sleep and even temporary peace overcoming me, my eyes closed. Yet the next thing I knew, a croaking sound echoed beneath the sharp, metal bed springs. Perhaps it is a

delusion occasioned by lack of sleep? I wondered. The sound repeated, obnoxious and low.

Half-asleep, I leaned down and peered beneath my couch-bed. A bullfrog stared back at me, its eyes gleaming with mischievous bliss. A feeling of dread arose inside me. This was going to be one long night.

By Aimee Wan ‘26

Taking care of a plant is like taking care of a mute toddler. I don’t plan on having a kid until I’m in my late 20s, but I expect them to be pretty difficult things to keep alive. An indoor plant, though, might be the only harder thing to stay alive and thrive. “Oh, you should never compare a plant to a child,” my mind says. But listen, when a plant is sick, it can’t tell you what’s going on, like a mute toddler—one day it’ll be blooming flowers and the next, plop, plunging to its death, again, like a mute toddler. Multiple hours a day, I spend nurturing my plants, observing their every move because if they’re not willing to tell me what the hell is going on then I need to figure it out myself. Unlike toddlers, who can bounce back from scraped knees and broken bones, some plants can be horrifically delicate—they practically become suicidal if you give them the wrong type of pot or you water them a day early. The only thing that takes longer than observing my plants is researching them. Researching about what the genus needs and the differences in light and nutrients for different subspecies—I’m like a newly-introduced mom reading baby books. Imagine having 40 picky eaters in one room (the exact amount of plants in my room): one needs their mashed potatoes chunky, one needs them smooth, and the other hates mashed potatoes in general, but the only person responsible for making all these mashed potatoes is you.

I became a plant mom simply because my room initially looked like an insane asylum. My room used to be all white–white walls, white curtains, white cabinets, white everything. To prevent me from actually going insane, I decided to add a few plants, a few pops of color. I was surprised when I saw the

difference it made to have a few bits of greenery in my room. Not only would I not go psychotic, but suddenly I had responsibilities, which I initially enjoyed. Watching a new leaf pop out, the satisfaction of what used to be a miniature plant grow into a bushy elegant piece of art, is truly rewarding. I kept going back to my plant nursery to purchase more plants for my room, and it didn’t take long for it to become a full-fledged obsession. A simple Google search became hours of watching plant videos online, spending hundreds on soil mixtures, then eventually spending most of my day

watching live auction streams for rare foreign plants. These auctions felt like a heated warzone: it was me, a high schooler who needed to study for my math test, and a dozen other millennial women stuck in their homes with their cats and mushroom mugs. The biddings were intense and filled with rage; whenever someone bid more than I could afford, I forfeited and

lingered another hour or so until I found another plant I was interested in. I felt like the crackhead of the plant world, constantly fiending for new exotic species on the market. And whenever I saw a leaf on a plant start crisping and browning, I immediately went into panic mode. Google and forums, then more Google and more forums, I simply could not understand why some of my most precious plants were dying.

One afternoon, I sat on my bed with a crispy, browning Philodendron Verrucosum (a semi-expensive plant that I’ve been trying to save for months) in my hand, feeling helpless. I didn’t understand what I did wrong, or if I did anything bad at all. I realized then how much I mirrored this plant: both of our roots were quietly suffering in ways that only became obvious when the damage had already set in. My mom walked in while I was pruning the rest of the yellowing leaves off and asked what was wrong–not with the plant, but with me. For the first time in years, I let everything spill out. I expressed things that were completely irrelevant to plants but instead things like college and relationships. My voice shook, and tears blurred my vision, but my mom didn’t interrupt. She just sat there, her quiet presence wrapping me in the kind of comfort I’d never noticed before. It was that moment that made me see her not as only a mom, but instead as someone who cared as deeply for me as I did for my plants. It wasn’t until later that I realized she’d been watching me, just as I watched my plants, trying to figure out what I needed when I wouldn’t say it out loud. Though, it was at this point that my mother started questioning my motives and how much responsibility I could handle until I broke. She’s been a mother of actual human beings for 24 years, so I would think she understands how I felt when my most precious “babies” started shying away from me. Oddly

enough, my older brother and I are the mute toddlers of her life. We’re both quiet and extremely wary of the things we tell her; we never really mention our problems and emotions until it becomes painfully obvious from the looks of our faces—like how my plants start to brown for unknown reasons. I could tell that my mother was always bothered about how my brother and I constantly hid things from her, and it broke me when I realized that hiding my emotions and personal life wasn’t doing either of us any good.

Whenever she knew something was wrong with me, my mother would send me articles about what I might be going through—depression, romantic relationships, breaking up from a romantic relationship— and I can imagine her frantic mind scrolling through those articles hoping to get an answer on what I was going through. I have everything I ever wanted: a spacious room, food, clothes; these things were all purchased by my mom for me and me only, so why am I doing what my plants are doing? Hiding from my mother who has given me everything, fulfilled all my needs, and provided me with all the care in the world? So petty of me! I refuse to be the mute toddler anymore.

I still love my plants—obviously—it’s part of my character and personality, but nevertheless, they’ll always be a mystery to me, like any rowdy teenager or mute toddler to their parents. Plants have not just provided me with a pleasingly aesthetic room, but they have taught me that being a parent is the hardest yet most gratifying job ever. It’s an act of constant observation, relentless care, and occasional heartbreak, but the reward of watching something or someone you took such good care of grow up and thrive is a feeling that simply can not be replicated.

By James Dorazio ‘26

In a low-slung garage on West 44th Street, the lifeblood of New York’s yellow cabs courses through every tool and tin of paint. Mike’s Yellow Management––a combined taxi repair and paint shop––has operated here since the early 2000s. Family-owned by Michael Sinder and his wife, Elisheva, the shop began as a medallion fleet maintenance hub and has evolved into an all-purpose fix-it bay for cabs. In its prime, it was advertised as “the preferred repair shop” for NYC taxi drivers, offering everything from engine overhauls to 24-hour towing for stranded cabs (Taxi Insider, Vol.14 No.9, 2013). Regulars knew to “ask for Mike,” the no-nonsense owner who would get a banged-up taxi back on the street by sunrise.

Over the years, Mike’s Yellow Management became a pillar of the taxi industry. The very name shows its speciality: keeping cabs yellow. Beneath the garages’ flooding fluorescent lights, Ford Crown Victorias and Toyota hybrids alike have been pounded back into shape and sprayed that signature canary-yellow that is ever so familiar to New Yorkers. Michael Sinder, a grizzled veteran of the trade and proprietor of the repair shop, has never been shy about sharing his opinions. He famously blasted the city’s modern Nissan NV200 “Taxi of Tomorrow” as “no good… like you’re in a truck and it can’t take the potholes”—a reference to his preferred selection of the sturdy old models his shop knows best (NY City Lens, 2015). His crew of seven mechanics embodies an old-school work ethic: on any given afternoon, one might be hunched under a cab’s hood while another hauls a half-drained oil drum across the concrete floor. Grease-stained and bustling, the space exudes an industrial vibe that

feels increasingly rare in the quickly-gentrifying Hell’s Kitchen.

Yet this gritty charm comes with its issues. The shop’s spray-painting process, often carried out with scant ventilation, leaves the air thick with poorly dispersed fumes. Workers and visitors alike taste the chemicals in the back of their throats. Neighbors have taken notice, too. In 2015, Beacon High School moved next door, and almost immediately, students began complaining of noxious odors wafting into their classrooms. Over the past decade, those complaints swelled into an acrimonious public dispute. The Department of Education had “serious concerns” about Mike’s “improper ventilation and fume” management, and inspectors even issued a violation for the shop’s jury-rigged paint booth filters (Eyewitness News 7, 2024). The Sinders, for their part, insist they run a lawful operation with no major infractions, chalking up the backlash to harassment by the school. For now, however, Mike’s Yellow Management endures—a living relic of New York’s taxi golden age. The rumble of engines and stinging scent of enamel paint spill out onto the sidewalk as they have for years. Inside, battered taxi fenders and spare patriots lie in neat chaos, waiting for resurrection. The shop’s resilience is a testament to the city’s changing yet resilient taxi culture. In an era where ride-hailing apps dominate and many cab garages have faded away, Mike’s stands defiantly, paint gun in hand, keeping the city’s yellow cabs on the road.

By Eliana Rosner ‘25

Something is different. I can tell before I find a flower pot knocked over from the tidy row of flowerpots lining each side of our windy driveway. I can tell before I walk up the three stone steps that lead to a tall, gray door, to find it slightly ajar. I could sense the difference even as I drive—carefully and slowly enough that someone a mile away would know I just got my driver’s license—past the tall green hedges that

something is different, I can tell. My parents have been on a business trip, and it is my first day back from a three-day college trip to decide what my future may hold. As if I know. Tomorrow morning, they will come home. Now, I open the door gingerly, as if it might fall off its hinges. The house is silent, yet the creaking of my footsteps seems loud. The foyer looks as it has always; coats neatly

surround our lawn. Perhaps it is an animal instinct inside me; the gut feeling that goes past civilization and humanity and time. Or perhaps it is the persistent but shut-off hope that I have always held inside. But

placed on the racks, aside from my green one that is missing. And the muddy trail of footsteps on the black and white marble tiles. Shaking my head, unsure whether to be pleased or annoyed, I continue my

exploration. Deep down, I know it is actually a search.

The kitchen is a wreck, with cupboards left open, swinging in the September-night breeze. Cups scattered on the floor, dirty plates piled in the sink; a Nutella jar left open with a spoon still in it. Surprised we even had Nutella, as my parents never let us eat sweets, I take a tentative step closer. The spoon’s shiny, metal surface is stained with a plum-toned lipstick. My breath hitches. A stool has been dragged to the countertop. A banana peel is carelessly flung to the ground, and I know a nutella-banana sandwich was made. Her favorite meal.

The dining room looks the same, three wooden chairs on a red carpet surrounding a wooden table. It is the living room that has been tainted, a portrait of my mother, father, and me taken out; black and red

sharpie drawn to form a beard on my mother and a frown over my father’s face. My parents’ eyes are crossed out. I look the same, aside from alien ears drawn above my head. Not sure whether to scream or shudder, I let out a hollow laugh that echoes below the lofty ceiling. Music on the piano has been rearranged, the whole set of Chopin books gone. The piano is shiny and polished, and the covering over the keys carefully closed, though I know it has been played over and over again these last few days.

I can hear the trespasser’s voice, high and daring. “Not too rusty, am I?” she will say with a challenging smirk, brushing her strawberry-blonde curls out of her face.

I walk upstairs to my parents’ bedroom, continuing my investigation. The room has been destroyed, paintings vanished from their walls, photos strewn on the floor in shattered glass frames. Feathers stick out of the mattress, which has knife marks along its sides. I leave quickly, going to the room that was previously my sister’s, before it got converted into a mini-gym. Long cracks run through the glass of the mirrors, likely by floor weights which look slightly dented.

I enter the room I have been avoiding, my bedroom. Unsurprisingly, the lights have been left on, eerily casting my shadow onto the lavender walls. The blinds are open, too, letting moonlight seep through. Feeling mocked by the stars and chirping of crickets, I stalk over to my closet. My clothes, previously arranged neatly on hangers, have all been piled together on the floor. At least two of my shirts are missing, along with my favorite jeans. Yet, I am too relieved to be upset.

The eyes that stared back at me were different. I knew that. Sure, they were the same murky blue ones I woke up with, yet after the series of receipt-riddled events that occurred this afternoon, something had changed. It could be the glitter, faintly dancing on my cheeks, the fragrance plastering my nasal cavity, sprayed on me against my will by Shannon from Chanel, insisting I would be irresistible to the ladies. My gaze traveled from my reflected eyes to my wardrobe. I never really liked purple, however when the tailor on floor four of Groowingdells plagued me with compliments on how well this ugly garment fit me, I caved and paid an uncomfortably large sum for the clown outfit (it came with a matching hat). Still, who am I to judge what looks good in this city?

A humid breeze blew the matching purple atrocity from its place on my head.

By Phoebe Last ‘25

“Excuse me sir, you dropped this!”

I turned towards the voice and was faced by two figures, a man and what looked like his teenage son. The father looked strong, and the son looked

frail; the father’s complexion was tan and the son’s was green; the father set up for levity, and the son for philosophy. They both shared the same emerald green eyes. Moving my gaze subtly down from their physical features, I started to notice their contrasting wardrobes. The father was wearing simple rugged boots,

similar to the ones I wore at home, handling the lobster nets. His pants were worn, the seams going down the legs were fraying ever so slightly. He wore a tattered black jacket. I saw a lot of ripped clothing today. The rips I had seen were intentional and styled. I even saw a plaid pair of pants with the knees cut out and bedazzled with crimson gemstones, an awful choice. This black jacket, however, was worn in the seams of the arms, the uneven number buttons on one wrist. All tattered from years of love and use.

My eyes traveled to the son. He wore loafers adorned with freshly polished silver buckles. His ironed pants framed his legs and he wore a fitted suit jacket that looked like it had been made just today. I swore I saw it on floor three of Groowingdells in the men’s designer suit section this morning. Both men looked very out of place standing next to each other, one significantly more than the other. The father smiled warmly as he eagerly handed me my clown hat. I thanked him and he and his son continued down the block. As I watched them, a raindrop dashed from the sky here and there.

The dribble turned into a downpour of thick drops. The colors began to run. My plum suit bled like someone had poured a perfectly good bottle of red wine down the nearby sewer the chemicals were now running into. I felt the rain but now it wasn’t so much destroying my assets as I suddenly felt an overwhelming sense of being cleansed. It didn’t matter that I had paid an embarrassingly high price for that garbage outfit, I mean sure, my wallet was silently crying in my pocket, but I knew what I wanted to do now. The city of Goldsad was not for me. It was meant for Shannon from Chanel, and the tailor from floor four of Groowingells, and the stranger’s son. Sterhom was my home. I let the sky shower wash off the smelly perfume, the faint glitter, the colors of

my trappings pooling around my overpriced boots. It was time to go home.

The following day, I packed up my (now few) belongings, my wallet feeling a great deal lighter, and headed out of the busy Goldsad. I drove away from the geometric city, then a long winding road, eventually transitioning from pavement to a sandy dirt road. To my left a sign read Sterhom 3 Miles. A scene was painted under the text: A faded red lobster, its shell now weathered and peeling, was imprisoned behind a flaking depiction of a lobster trap. I continued down the dusty road until I turned and my wheels crunched over the oyster shell driveway.

Sara Elbaum

By Madison Cho ‘26

She clutches the steering wheel with pale, tremoring hands, navigating through the rugged terrain of the mountains. Each strike of a pebble shocks the Jeep, the 1990s love of her dad, and it falters as though it might break down any second. She peers out anxiously at the warmly-coated oak trees, their bright-toned leaves offering a suitable evening attire for the enormous branches that tower over her. Piles of foliage scatter all over the trail, no longer able to retaliate against the autumn breeze, but acknowledging her presence with a carpet-like scene. Alas, a sign appears. Camp Wish up ahead. The letters are hardly legible, degraded by decades of rain and insects. The engraved symbol of a buttercup petal appears to be nothing more than an accidental indentation.

Years ago, when she arrived for the first time, she was in the backseat. Half dozing, she was awoken by the hushed but vibrant conversation of her parents. Leaning her little eight-year old head against the window, she lazily opened one eye, not as curious about where they were going as she was about her parents’ excitement.

She cautiously places her foot on the accelerator, wanting to arrive at the site as fast as possible

but fearing the lonely entrance to her childhood space. Mere seconds pass until from the surrounding trees the cement parking lot peeks out. It is the only sign that an outsider has penetrated the walls built around this world that has existed alone for centuries. As she turns the corner, a gust of wind blows past, indicating the emptiness of the space. A small smile escapes from her

pursed lips. It really is a secret place.

***

Back then, her head tapped against the window as the car encountered a sharp turn. She struggled to keep her eyes from both closing and opening, overcome by sleep and the unease of what lay ahead. It wasn’t long before she gave up on the idea, curiosity sabotaging her attempt. She opened her eyes to an empty parking lot.

Worried, her panicked voice shook on the last syllables of each word, and she cried out, “Are we lost?”

Her parents chuckled. Silly her. It was supposed to be a secret place. A location shared within their hearts. “We have the entire campsite under our control,” they whispered.

***

She hurries to catch the falling thermos as the trunk opens. The mountainous journey had a violent impact on her camping items. The tent wrapped tightly around her backpack had unfurled itself, displaying its need for freedom. She impatiently puts everything back into place, afraid that if she waits any longer, she might unknowingly find herself driving back home. Reaching for the strap buried beneath the beach chair, she slings the backpack around her shoulders, staggering under the heavy load. With only two hands to spare, she looks over at the remaining items left to carry: the beach chair, the hammock, and the sleeping bag. “I can just sit on the chair,” she justifies, almost hesitant to leave the hammock alone overnight. Mus-

tering up all her strength, she pulls the items into an embrace, avoiding eye contact with the excluded one as she shuts the trunk. Turn to the right and continue forward. Her dad’s voice rings in her head. “Turn to the right and continue forward,” she repeats. The oak trees lining along the trail sway in harmony with the breeze. The piles of leaves that looked like a welcoming carpet into the camp now resemble a trail, leading her in the right direction. The walk to the site doesn’t take very long.

***

Her parents had hurriedly lifted up all the items into their arms. The warm blend of pink, purple, and orange painting the sky encouraged them to pick up the pace to face the approaching nightfall. With a beach chair in one arm and three sleeping bags in another, her dad looked no different from Superman. Her mom had stacked up all her favorite snacks, carrying a surplus load of food for an overnight stay.

“Could you get the hammock in the trunk,” her mom had asked. Her innocent face had lit up, elated at having been assigned a responsibility. She took

extra caution to ensure none of the sides were draping across the ground.

“Turn to the right and continue forward,” her dad told her. She skipped ahead, observing the birds fly just as ecstatically from tree to tree, their plumage resembling the breathtaking color scheme of the sky.

***

As she makes her way up the last slope of the trail, the sun betrays her. It dips below the horizon line, leaving her to find her way to the site from memory. She continues to walk for what seems like an eternity, finally interrupted by a fall back to reality. A pile of wood was stacked neatly alongside the firepit, but she rubs her knee in pain as the wood pieces lie scattered all over the ground. With the last of her patience dwindling, she takes out the lighter and sparks the world awake.

***

Her short, athletic legs led her straight to the firepit in a matter of minutes. The sky had become drowsy, tainted by a darkness that would soon engulf her surroundings. Her parents, panting, arrived earlier than expected, their experienced legs exhausted from years of work.

“Let’s set up the tent,” she suggested, anxious about their shelterless situation.

Her dad smiled reassuringly. “You don’t need to be afraid of the dark. For now, let’s soak in the moment.”

She pondered for a second. “Then, can we roast marshmallows?”

***

She takes out the marshmallow pack from her bag, stacking three at once on a stick. Don’t be afraid of the fire. Bring the stick closer but not too much as to burn it. Her mom’s presence seems to wander near the firepit, constantly

worried about her daughter getting hurt. She pulls the stick out of the heat and the marshmallows seem to boast their new golden coats. With a tentative bite into one, her mouth fills with a pleasant sweetness.

***

“Don’t be afraid of the fire. Bring the stick closer but not too much as to burn it,” her mom had told her. She was scared of the pit, the fire blazing in her direction as the night wind blew. Her mom had wrapped her familiar, comforting hands around her own, guiding the marshmallows to the stores from which they would receive new coats. After a few seconds, they pulled back from the flame, and the marshmallows shined brightly with their golden-brown tinges. As if to wish congratulations, her dad gently tapped her, pointing at the pitch-dark sky. Her eyes took a moment to adjust and soon she began to see sparkling diamonds.

Her dad whispered cautiously as though his interference would ruin her revelation, “If you connect them one by one, you can find…”

***

“Capricorn next to Sagittarius,” she murmurs.

By Bella Pass ‘27

The lights flicker. Then they stop.

I continue refreshing my phone hoping that the WiFi will come back, trying to ignore the rain that slams against the kitchen window.

I hear a crash outside. The lights go out entirely. My heartbeat picks up. I look around the room, which is almost entirely pitch black. Through the darkness, I see my mother, who hovers over the sink, waiting patiently for the lights to return. I turn the other way to my father, who hasn’t moved from the floor where he was tending to our stove, which unsurprisingly won’t turn on. No one says a word; we all wait confidently for the lights to come back on.

A minute later, they do.

back from when my parents bought the house, which was over 15 years ago. We don’t use it often, or at all. When we tried to turn it on this morning, it didn’t even work.

This was the second power line to fall this week, after all. The horrible weather had caused several power lines to fall all around the neighborhood, and we spent most of today under dim lighting. The sky is practically black with heavy clouds blocking out the light from the sky. The rain has been heavy for hours and there is no end in sight. My mother insisted on using our generator only when necessary since she’s paranoid and convinced we must save energy so that the generator doesn’t burn out. I’m not really sure if that’s how a generator works, anyway.

“Another power line,” my dad declares, his tone seemingly tired, almost bored. He doesn’t even look up from the stove; now, his head is practically under it and he grunts as he frustratingly moves around wires from underneath. Our stove is outdated, it dates

Without a word, my mother returns to rushing around the kitchen in a sweat, trying to assemble a somewhat reasonable dinner.

The contents of our refrigerator are sparse: only containing two sticks of butter, a random assortment of rotting produce, and a half-full container of milk that is most definitely spoiled. When I opened it

Karabelas

earlier today to see what we could make for dinner, I was met with a nauseating stench as foul as a dumpster. Besides that, the only other ingredients in our house have been sitting in the pantry for months, maybe years, and are barely viable for dinner.

The pouring rain hits up against the window, creating constant noise behind our preparation.

“Ryan!” my mother shouts to my brother, who sits across from me, tapping his finger boredly against the table instead of helping out. “Can you cut the broccoli?” We both turn around to see my mother holding up a single head of shriveled broccoli. Before my brother can make a sarcastic comment about the current state of the broccoli, which I know he wants to do, my father yells, “Finally!”

I turn around to see that after spending twenty minutes frantically turning different knobs and pulling wires, he finally gets our much too-old stove to work. Most nights, my family goes out to eat at one of the many fast food restaurants in town, or eats leftovers we

brought home from the previous night. When my mom entered my room thirty minutes ago, declaring that we would all pitch in to make family dinner, I was stunned. After my mother gathered my father, brother, and I, we all walked into the kitchen, my mother first, unsure of what we would come out with. And now, it seems we’ve made very little progress from where we started.

“What else are we having besides broccoli?” my brother asks, not trying to hide his disgust.

“Why are we even trying to make dinner? This is pointless. We all suck at cooking,” I think, but refrain from saying since I don’t want my mom to feel worse.

Lightning strikes, illuminating the sky and briefly bringing light to the dark outside world. We all pause for a moment, caught off guard by the lightning. Only a few seconds later, though, my mom says, “Well, considering your father forgot to go to the butcher yesterday when the rain wasn’t as bad, we have very few options.”

“Well, it isn’t my fault—” Thunder booms abruptly, cutting off my dad’s response to my mom’s annoyed comment.

“Madeline,” my mom begins, not looking up as she stirs the rice she found at the back of the pantry. “Can you please get up and help your father or me? We could use it.” Her voice is annoyed, like usual. I close my book and walk over to my father, who is rummaging through a drawer I had never seen anyone open. It is usually kept locked.

“What are you doing?” I ask, completely unsure of what he could be looking for.

“Um,” he mumbles as he scoots in front of the drawer. “Nothing,” he declares, his eyes dart back and forth, avoiding eye contact. “You should go help your mother.” He doesn’t wait for my response and instead turns back around and continues looking. Once again, I don’t argue.

I walk back over to my mother, who is still stirring the rice but looks preoccupied like she is thinking hard about something. I place myself a few feet away from her and lean against the countertop. I waited for her to assign me a job, which she usually would. Instead, I end up standing there for a few minutes. She doesn’t even notice me.

“Mom,” I begin, ready to question her and ask her why everyone’s acting so weird, but instead, I continue with, “When do you think it’ll clear up?” My attempt at lightening the mood.

To my surprise, she answers, “Why would I know?” Her voice is clipped and defensive, almost like a child trying to hide something she did wrong. I can tell she didn’t mean it to come out so harsh because she finally stops stirring the rice and says, “I just meant that there doesn’t seem to be an end in sight.” I nod. Twenty minutes later, after sitting on the couch after no one assigned me a job, my mother declared that dinner was ready. We gather around the mostly bare dining room table and stare at our attempt at dinner. A small bowl of nearly gray broccoli sits at one end. Next

to it, a slightly bigger bowl of pale, soggy rice. Lastly, at the side closest to me sits a small bowl of canned tuna my mother found and declared would be the perfect addition to dinner. After a few moments of silence, my mother picks up the rice and spoons some onto her plate. My brother, father, and I wait and watch as she picks up the broccoli.

“Eat,” She insists.

“I’m not hungry,” I say, remembering I have a chocolate bar in my school bag from last week. Hopefully, it will fill me until tomorrow, when the weather won’t be as bad.

Later that night, I lay in my pitch-black room, staring up at my ceiling covered in stick-on plastic stars that glow in the dark, reminder of my childhood that I have yet to take down. As I fight to fall asleep, I am disturbed by every drop as it hits my window. Usually, when I can’t sleep, I pick up my phone and call one of my friends or turn on my TV and watch a movie, but once again, I am reminded that they are out. The droplets are inconsistent, some hitting lightly, others banging against the glass like someone is breaking in. I become fixated on them, trying to predict how loud the next one will be.

After a while, the sound fades away as though the background music to my thoughts, playing rhythmically as my mind wanders elsewhere. I think of the last day I was lucky enough to miss school. It was a snow day. That morning, I woke up to the sound of my alarm. I lay in bed for a while struggling to get up, completely oblivious to the snow-blanketed world just outside my window. When I finally did get up, I leisurely got ready for school, putting on my typical sweatpants and sweatshirt, the first ones I could find, and throwing my hair into a horrible attempt at a ponytail. I casually walked into the kitchen, my eyes glued to my phone as I checked my texts, and sat down at the table. After a while, my mom came into the room.

“Madeline?” she asked, trying to get my atten-

tion. “What are you doing? Look outside.” I got up and looked at the kitchen window, and to my surprise, all I could see was white. The once bare trees were covered in a coating of white powder, allowing them to blend in with the background, the sky. The grass was covered in a sheet of ice that poked through the blanket of flurries that topped it and continued to fall on top. “School is canceled!” she finally announced. I felt relief and joy. I could spend my day with my

“Madeline?” my mother asks, clearly surprised by my presence. “What are you doing up?”

“The storm has gotten worse, so we wanted to make sure that we have everything we need,” my father cuts in.

They look at each other, like they are having a secret conversation in their heads. My parents both wear their pajamas, but it seems as though they never actually went to bed.

friends, all of us snuggled up on the couch watching movies, hot cocoa in hand. Hanging out, without a care in the world.

Finally, I fall asleep.

I wake up to a bang.

“Mom? Dad?” I whisper as I creep into the hallway, not wanting to wake my brother, wondering if he is even awake.

They turn around quickly.

“Honey,” my mom finally begins. “This isn’t just a thunderstorm, it’s much worse…”

“Like a hurricane?” I say ignorantly.

“No, well… maybe.”

“We’re not sure what it is, if we’re being honest. But something’s…off. We just want to be prepared. And with the tv being out, we can’t really know when this is going to stop.”

“What do you mean by ‘off”?” I ask, hoping to

grasp what they are saying.

Without another word, my mom walks into the living room and opens the blinds on the nearest window. She motions for me to come closer.

“Look.” The sky was an orangey yellow color, like nothing I had ever seen before. It looked almost apocalyptic, like a volcano had just exploded and polluted the sky. Now, I could tell that she seriously didn’t know what was going on, since her face was just as confused as mine was. We both stood there for a moment, simply observing the sky.

“What do we do?” I finally say, as panic hits me. “This can’t be normal. We have to leave.” I begin to get worked up, my heart racing as lightning illuminates the sky into an almost red color.

I can now see the severity of the situation, the reason they were so weird at dinner and even the morning prior. Something was wrong.

“Guys,” I beg, my voice becoming high pitched and squeaky. I look to them, hoping that they will make the rain stop, for it all to be better. My mom comes up to me and wraps her arms around me tightly. I rest my head on her shoulder and we stand there interlocked.

All of a sudden there’s a crash in the other room. My mom and I separate and the three of us run into the kitchen where the sound had come from. To my surprise, a tree sits half into the room. It had fallen through the window and sent little bits of glass all over the floor.

“Shoot!” my dad shouts.

“Oh my god,” I blurt out, shocked by the whole thing. We, mom and I, step back, trying to avoid stepping in the glass. I try not to panic, knowing that a window could easily be replaced. It was the fact that the storm was getting worse that really

scared me.

Rain blows in through the now shattered window, covering the kitchen in water on top of the glass.

“Go wake up your brother,” my dad demands. The wind from outside is so loud that he has to yell just for me to hear him from a few feet away

“Ryan!” I shout as I burst into his room. “Get up.”

“Leave! It’s too early,” he responds, clearly not understanding my tone.

“No Ryan, get up,” I say firmly, shaking his legs. He reluctantly pulls himself out of bed and follows me into the kitchen.

When we enter the room, my dad isn’t cleaning

up the shards of glass like I had thought but instead is standing in the door frame, seemingly waiting for us.

“What happened?!” my brother asks observing the kitchen floor.

“We’ll explain later,” my mom insists.

“We have to leave,” my dad finally declares. No one asks any questions. We had been sitting in this house for two days. Something needed to be done. I knew we needed to go. Still, I don’t feel comfort like I was hoping I would when he made this decision. Now, I feel fear, wondering where we will even go.

Ten quick minutes later, the four of us are loaded into the car along with as much food, clothing, and supplies as we could fit in with us. On our way out, the wind practically takes me with it, if not for my father who holds my hand firmly.

“Where are we even going?” my brother asks, still confused by the entire situation.

“I’m not sure yet, sweetie,” my mom responds, while turning around from the front seat and giving the two of us a reassuring smile, even though nothing could really be reassuring right now.

The rain pounds against the car, we are all soaked from loading up everything anyway. I look out the window to see the leaves flying off of the bushes, and the branches of the trees swaying uncontrollably in the wind. The sky is now an even deeper orange but the sun is nowhere to be seen. I want to pull up the hood of my sweatshirt and drown out the world but I don’t. I try to stay alert, I observe what is happening around us.

We start driving a few moments later. My dad drives slowly, trying to stay toward the center of the road since we are the only ones outside anyway. My mom stares intensely out of the window.

The car sways because of the wind, rocking us all back and forth.

“Dad, can you drive any faster?” I suggest. Without a word, he picks up speed.

We speed down the street, dodging any branch-

es that have fallen or are falling onto the street. It feels like a scene from an intensive action movie where the hero is running away from the bad guys. Still, it feels like we are in need of a hero ourselves. No one says anything. We all bite our lips and hold on tight, watching the destroyed world around us.

After at least ten more minutes we slow down.

“Dad?” I asked, concerned by the sudden decline in speed.

“I don’t know what’s happening,” he says as he frantically slams his foot on the gas, but we only go slower.

“What do we do?” my mom asks. It sounds like she is about to cry which is something that I would have never imagined happening.

“I—” my dad pauses, he sounds hopeless. “I don’t know,” he finally mutters. The car stops.

As we sit in defeat, my mind wanders back to our dinner just last night.

How frantic we were to put something together. How I thought the whole thing was a joke. How uninterested I was in helping out my family. How excited I was to leave the house the next day. How ignorant I was to this whole thing.

We won’t be leaving this car. I know it. And so, I sit. Now facing my parents and brother, we all look at each other. I observe my mom’s hair that had fallen from the bun it was in only a few hours ago, her gray hairs at her roots peaking out more prominently as ever. I notice the pink and white striped pajamas that she has had since I was a kid, that she seemed to wear every single night. I notice my father is now tired, lifeless eyes as they simply stare down at the console in the middle of the car. I look over to my brother who still holds his phone although it doesn’t even work. I notice how grown and different we all look. In only 24 hours, it seems as though we all aged.

Again we are stuck in the dark. No hope. No clue as to what is going on. All I can do is observe, and wait, wishing that today was a snow day instead.

By Phoebe Last ‘25

Red water, red water, red water… awake. Helen Lister woke up alone on a crisp fall morning. She had cracked the window the evening before and now as she sat up, the chilly morning air greeted her silver locks, before traveling through her nostrils, cleansing her lungs. She looked down. Those beautiful wise hands. Mrs. Lister had a routine of studying her hands every morning before rising from her bed. It was truly an odd ritual, but she found it essential to starting her day, reflecting on weeks gone by, adding up to years, decades at this point. She would follow the veins on her wrists, leading to her knuckle grooves, deepening as she flexed her fingers. Her right hand traveled to her left, tracing an indentation spanning the circumference around her ring finger. Where was the ring? And where was its sibling? Her grooved forehead furrowed as she caressed the empty side of the bed.

Where was he? But wait. She remembered him handing her the paper at breakfast. This morning. No, that wasn’t right. Mrs. Lister hadn’t had breakfast yet. Where was he?

She rose from the nest of her comforter and made her way out of her bedroom. The wood creaked below her wrinkly feet as she descended the winding staircase that led to the living room. Memories clung to these flowered walls. As Helen looked she saw two teacups sitting on the polished wooden side table, sandwiched between two grand armchairs. The cups were close to empty and when she picked one up, the remaining tea chilled the porcelain in her hands. The square label twisted around the handle read: Peppermint Dreams. She placed the two cups in her kitchen sink just off of

the living room.

Every morning, Mrs. Lister would paint. Her current masterpiece was a still life of a vase filled with lavender, daisies, and Queen Anne’s lace. A canvas lay stretched upon her wooden easel, faint pencil outlined the vase.

Today, it was time to add color. Next to her easel were her supplies. Brush sizes ranged from as wide as a miniature broom to as thin as one of Mrs. Lister’s gray hairs. Paint colors layered each other in

an old tin next to the brushes. All she was missing was her blue sponge. It was supposed to be with her other paint supplies, but the only sponge she saw was a purple one, nestled between some spare brushes. It would have to do.

She squeezed out a dollop of white onto her paint palette. Taking a medium-sized brush, she dipped the brush first in the water, then dabbed it on the sponge and swirled it around in the paint. Her first paint stroke was pink. That was odd. She looked back at her palette, her thumb curled around the grip. Her white paint dollop had a pinky red streak from where her brush had met the paint. Retracing her steps, she looked first at the sponge, then at the water, then back to the sponge. The porous structure was indeed her blue sponge, she saw that now. Red stained the blue sponge into a rather sick looking purple color. That’s odd. She never touched the red paint tube. Her flowers needed white, not red. She shrugged, still very confused, and brought the reddened sponge to the sink. She turned on the water and began to clean. Red water, red water. The sponge turned the water into bright red ribbons as the water weaved itself through Mrs. Lister’s fingers. She watched in awe

and fear at the water as she added more soap to the sponge. The soap formed pink suds on her hands. As she moved them under the water they washed away with a wave of rusty water. Blood. She knew it was blood. She saw that now. None of her paint ever washes out without staining. Helen’s head began to spin. She put the bleeding sponge in the sink and wobbled to one of the large armchairs in the living room, wiping her wet, raisining, hands on her painting apron. Her vision blurred and for a moment she thought she saw a figure of a man crawling around the corner leading to the hallway. Then everything went black. It could have been hours, maybe even a whole day had passed, when Helen Lister woke from her rest. She was still in her armchair. Sunlight streamed through the windows, illuminating the canvas on the other side of the room. As she looked at the easel, a small smile crept across her face. Every morning, Mrs. Lister would paint. Her current masterpiece was a still life of a vase filled with lavender, daisies, and Queen Anne’s lace. Today it was time to add color.

She rose from her chair and, a bit light-headed, she made her way to the easel and plucked a fresh brush from the brush tin. She needed water for her

paint. In the sink lay her sponge. She had been looking for that. Helen didn’t remember putting her sponge in the sink. She must have forgotten to take it out of the sink the last time she painted in the morning. Those were to have been some luscious red roses she had painted, for the red color wasn’t fully washed out of the sponge! She chuckled to herself but went on with her routine, grabbing a fresh cup of water and leaving her sponge in the sink to drain.

intuition. In went the milk, eggs, and other baseline ingredients, stirring expertly between each new component until she had a thick dough. She added a pinch of nutmeg to boost the biscuit, and, when she felt the dough was ready, shaped half a dozen biscuits and slid them into the oven for about ten minutes. While she waited, she put away the nutmeg, the eggs, and the milk.

Mrs. Lister always made the same tea biscuits for both of them, only she liked them plain, he liked them with a light powdering of sugar on top. He’s always wanting something sweeter, she smiled to herself as she began to measure the flour and sugar from the two ceramic blue bowls on the counter in front of her. She combined all of the biscuit ingredients into a mixing bowl, hand painted by herself. Her husband had given her a plain wooden bowl for their wedding anniversary decades prior, and she had been mixing their morning biscuits in it ever since. The recipe itself was very simple, like Mrs. Lister. It was almost second nature at this point and she barely used the right measuring cups anymore, instead measuring with her baking

Ten minutes passed by and the golden biscuits were ready to be plated and enjoyed. She let them cool a bit before grabbing two plates, one for herself, and one for him. On his tea biscuit, she sprinkled a light dusting of powdered sugar over the top. None for her, as she thought the sugar and nutmeg were enough inside the biscuit for any lilies to be gilded on the outside of the biscuit. Then the powdered sugar went away, back into its pink

ceramic jar near the flour and white sugar. The familiar wood creaked under her feet as she made her way to their study. He would spend hours there working on his taxidermy. “Here you are dear.” Mrs. Lister gingerly balanced the plate of warm biscuits on a teetering stack of books and files on his desk. She kissed the top of his head and went on fussing around the room. The shades were drawn that morning. From his place at his desk, he watched her open them. The window opened up into a mountain scene. The drama of the deep valleys and high peaks was breathtaking to say the least. Mr. Lister loved his study. Especially in the morning, when nobody was awake but a couple birds and creatures.

“How are you this morning, dear?” Mrs. Lister asked, bustling around organizing this and that. She had discovered a pile of letters on the edge of his desk that she was now flipping through. “I don’t understand how you can leave all of these letters unopened. Don’t you just love opening letters and packages?” She chuckled and suddenly gasped at one of the letters in her hand. The opening had been distressed, a tear cutting through the return address. She pulled out the contents, and as she did so, her face began to flush, and her breathing hitched. She snatched the contents out of the envelope and crumpled it. The thick paper resisted. As if to mock her. As if the ticket itself was pulling him away from her. She looked up at him, her eyes stinging. He appeared to be looking at her with a twinkle of humor in his eyes. He was laughing at her. She was disgusted. Outraged.

“We. Took. A. Vow.” The words caught in her throat as they left her lips. She couldn’t stand to be in that room anymore. She suddenly heard a screech. The birds on the wall had begun flapping against the wooden panels. The bird on his desk cried out, beating its wings against the pins holding it to the mounting board. Nearby, a great black crow centered on the wall to her right broke free of its restraints and flew at her, eyes lifeless, yet wild. She screamed and cradled her head, crumpling to the floor in a shivering ball of terror. Her vision began to darken as the flapping of the wings above her. They were flying so close to each other that the ceiling soon became a collage of feathers. The screeches blended with her fading vision, distorting into monstrous lulling sounds, until everything eventually went black.

A taxicab pulled into the Listers’ driveway. Ronnie Heartfly had been in the

taxi industry for 21 years. He loved his job. It was predictable and safe. He liked how structured traveling from point A to point B was. Ronnie also held a guilty pleasure for exploring. He loved that his job took him on all sorts of adventures, exploring cities and the countryside. He rarely visited the same place more than once. Walking up the path towards the house, he counted five crows in the yard. A murder, he chuckled to himself, walking up to the wooden cabin’s doors. He knocked three times, and waited for an answer. Nobody answered.

“Taxi-service! I’m here to pick up uh Mr. Twister… no, no, Mr. Lister, yeah, that’s the one.”

Again, no response. Ronnie checked his watch. Half past five. Odd. His clients usually couldn’t wait to get out of their houses, especially when they booked airport cab rides. He thought for a moment. What if Mr. Lister is hard of hearing? He jokingly turned the knob, not expecting the door to give way. It did. Why on earth would they not lock the doors? What if… Ronnie let his thoughts trail off. They were getting far too dark for his liking. Easing the door open, he let himself into the cabin. It was a beautiful old house. Floral wallpaper lined the walls. It matched the twin chairs, framing a wooden side table,

“I am here to pick up a Mr. Blister… uh no, sorry Mr. Twist—Mr. Lister!” He felt his face go hot. How embarrassing, forgetting a client’s name while talking to his presumed wife.

“Why, to the airport?” She asked. Her face seemed to crumple a little, pushing the valleys of wrinkles on her face together. Ronnie suddenly felt very awkward.

“Yes… that is where he hired me to bring him, ma’am.” Mrs. Lister looked at Ronnie with a faint squint in her eyes.

“Are you married?” She asked, a twinge of annoyance in her voice.

“Yes, I am. My anniversary was actually this past Sunday, I sort of forgot? It’s been so busy, you know how it goes.” He was rambling about life as a taxi driver now. Mrs. Lister was barely listening. Her interest was sparked again when he began to talk about his wife. “Sometimes, she can be a lot, you probably understand, being married yourself. Don’t you feel like sometimes you need a vacation from your spouse? I do remember how freeing my single years were. To be frank, I sometimes still go out alone once and a while, I always tell her I’m out on an errand, but we both know that’s not true.”

Nearby, a lone crow hit the Listers’ bedroom window upstairs. The sound sent an echo down the spiral staircase where the two stood. Mrs. Lister sighed

and nodded to the cabdriver. “You hear him now? He’s upstairs, just packing up a few last minute things. Why don’t you make yourself comfortable down here, while I fix you a cup of tea, perhaps a biscuit?” Ronnie was not a tea drinker. He preferred milked down coffee. Still, he felt bad refusing a cup from the sweet old lady, plus he was pretty thirsty after his long and winding drive through the dense woods and mountains.

“That would be great,” he replied, giving Mrs. Lister a warm smile. She bustled away and busied herself in the kitchen while he wandered around the living room. He noticed a smell that wasn’t there before. He guessed it had been masked by the buttery smell of biscuits. It was a chemical smell. His wandering senses were interrupted by the clink of silverware and teacups as Mrs. Lister placed a tray on the table in the middle of the two armchairs.

“Thank you very much,” he said.

“Please, have a seat,” she said, gesturing to him to sit down in the armchair closest to the table. She stood. He plopped himself into the cushy chair and picked up the teacup from the tray. Taking a cautious sip, he tried to control his urge to gag on the steaming substance. He truly despised tea. He masked his hatred by stretching and contorting his face into what he felt resembled a smile. All the time, Mrs. Lister watched.

“Why don’t you try a biscuit? I baked them fresh this morning.” He barely heard what she said, he was so focused on keeping the liquid from coming back up. He wished he wasn’t such a people pleaser, for his own sake. Seeing the perfect biscuits lying on the table, he took one and bit into it, a generous bite. A wave of relief washed over him, grateful for his mouth to have relief from the horrid aftertaste.

That tea was not sitting too well. He felt as if he was going to be sick. Tea was never a good idea for him.

“Pardon me, where is your restroom?” “Third door on your left down the hallway.”

Ronnie made his way down the wooden paneled hall. He had begun to hunch over at an angle clutching his now cramping stomach. It was a sharp pain. Nothing like he had ever felt before. A dull, yet piercing pain. As if his stomach was made of velcro, each step ripping the pieces apart. It was hard to walk by the first door. Unbearable by the second. He reached the third door and nearly collapsed right there on the carpet. He had to make it to the bathroom. Just a splash of water on his face should do him good. He made it to the fourth door. Easing it open, he was hit with a stench so foul it made his velcroed stomach suddenly convulse. The stench of his stomach contents mixed with the smell of formaldehyde and an awful rotting smell. It was such a strong smell that his eyes began to burn. He started to cough. He couldn’t breathe. He looked around his surroundings. He was not in the bathroom. He was in an office. He looked to the end of the room. A figure was sitting in a chair facing the large windows.

“Mr. Lister?” he managed to choke out.

No response. Ronnie heaved himself across the floor towards the chair. He saw a plate of biscuits on the desk. A bite was taken out of the top one. A trickle of blood was stained running down the chin, dribbling down onto his shirt. Ronnie’s own blood ran cold. It wasn’t the tea. He felt his stomach turn again. He coughed. His lungs hurt. He suddenly felt as if his lungs had filled with the horrid tea itself. As if they had liquified. He coughed again. Harder, into his hands. He tasted metal now. Looking down he saw bright red blood pooling in his palms. His vision

clouded. Ronnie couldn’t hold himself up anymore. He sank to the ground, coughing crimson onto the bare paneled floor. Through blinks, he saw flashes of crows. They seemed to be pitying him. He tried to force his eyes open, but they resisted.

Mrs. Helen Lister strolled into the study. In her arms she cradled the broken body of a crow, the life freshly drained from its silky black feathers.

“Oh Harry, look who I found outside. Don’t you think he would look wonderful atop the mantle?”

Sara Elbaum

By Savannah Vega ‘26

It was nighttime when I heard a loud, yelping cry ring out through the forest, like the shrill whine of a small animal. Everyone else was fast asleep in their cots on the cold ground, and for all their supposed alertness, not a single exhausted head sprang up in response to the noise. As the watchman until the moon reached its zenith, I took it upon myself to step briefly away from the clearing toward the direction of the sound in order to determine its source. The soupy darkness was close, and although I had a torch (albeit an old, flickering one, with part of its handle meticulously duct-taped) in hand, it crept up on me as two thick, oiled hands, threatening to clamp themselves over my mouth with dreams of suffocation. I patted my waist for the pistol at my belt, which had twisted as I walked in a rather irritating fashion. I slid the pistol from its holster. I thought it strange that an animal would live, but that did not mean it wasn’t plausible. It couldn’t have survived all of this time—our lifespans are short, and those of most land animals even shorter—and therefore, the animal that created this noise must have been a product of breeding after the fiery storm had subsided. Whatever it was, I would see it. I would make note of that marvel, that persistent scavenger, that naysayer of natural selection, and then I would shoot it.

I walked along tentatively, the world sporadically disappearing and reappearing beneath the shuddering beam of the defective torch, which I banged against my leg in a feeble attempt to temporarily remedy the ailments of its mechanical insides. So far, there was no sign of the animal, and it did not release another cry, causing me to grow somewhat disoriented

as I increasingly doubted from which direction I had heard the original call.

Suddenly, the trees parted, and I emerged into another clearing wherethe moon shone, illuminating a child, perhaps a year or two past toddlerhood, kneeling rather pathetically at its center. Disappointment momentarily washed over me, but as soon as it had come, the feeling fled. My attention was arrested by the silhouetted profile of the girl as she looked up to the stars, her face streaming in tears, which fell to the ground in a set of modest droplets. I lowered the pistol and stashed it in my belt, tiptoeing gently towards the girl.

“Hello,” I said softly, removing my mask. The girl turned abruptly, skittering backward onto her hands and grasping helplessly into the blackness as if it might somehow pull her away from me. I wanted to tell her that that might be somewhat of a questionable choice, for I now knew that the land held terrors far beyond anything my hand could accomplish, or my pistol, or my psyche. Perhaps even if I were a lurking demon, my skin a map of fleshy exposed tendons, she would be better off in my care. But I did not say these things; they were only in my head.

“No, no, there’s no need to be afraid. I’m not going to hurt you.” I held up my hands in surrender, and the wide-eyed girl stopped and looked back at me, tilting her head to the side. The resemblance was so uncanny that I nearly retreated. “What is your name?” I asked her. When she did not respond, I inquired about the whereabouts of her parents, but she did not respond to that either.

Instead, she twittered briefly and tapped her

neck, opening her mouth like… almost like one of those animatronic bass decorations except without the inane song—a memory which re-surfaced from the deep recesses of my brain like an empty can floating lethargically up out of a pond of molasses. The comparison was so absurd that I was momentarily distracted from her looks: the slight sympathetic upturn of her eyebrows, the cupid’s bow of her small lip, the rosy plumpness of her cheeks, and most notably, the crystal blue of her irises. Her face was identical to my sister’s as I remember her, and however foggy and obscure her memory had become, the girl’s appearance dusted off that old picture frame in my mind. I thought of camp, of bringing her back among my friends and showing them this living wax figure, this living replica of a dead girl. Surely the night had brought her to me, presenting her in its long, ragged arms like a peace offering, or maybe a sullen apology that read, Sorry,

we can destroy, but we can also create, and we made something for you. I would care for her with all my heart, give her all that she desired, and show her the wonders of the world we have created from nothing.

“Do you want to come with me?” I offered excitedly, my fingertips buzzing as I reached out to grab her small hand. She hesitated briefly before taking it.

When I arrived back at camp with the girl, the others were awake and sitting by the campfire, conferring in hushed tones. Frasier, who was closest to me, perked up as I approached with the girl. We were silent as dashing mice, walking with gaits so soft that we might have been simply part of the breeze, but still he turned in our direction, his face suddenly cast in shadow from the backlighting of the fire. I could not see his expression.

“You were supposed to keep watch,” he noted

in a gravelly voice.

I walked forward without speaking, raking my eyes over the seated crowd, each one of them hunched over the fire like a crow. When my voice was not heard in response to Frasier’s question, the heads of the murder turned, and Frasier spoke again. “What is that?” he asked, directing his attention to the girl.

“My sister,” I responded finally.

Someone in the group laughed, but was quickly shushed by the person sitting next to him. Cole, sitting beside Frasier, got up and walked over to us, kneeling and taking the girl’s face in his hands. “This isn’t your

sister, Vittoria.”

“I know that!” I snapped, and Cole stumbled backwards. The girl flinched, and I could feel her hand trying to wriggle itself out of my grip, which I only tightened in response. “You’re all going to take care of her. Treat her like you would a precious timepiece.”

“We don’t have enough supplies for her,” chimed Jane, a woman situated at the back of the circle. “Our rations will barely last through the next three days.”

“Then Cole will give up his rations while we search for more.” I heard a vague, muffled shriek off to