Housing Precarity and Homelessness

Housing precarity includes situations that range from uncertainty about whether one will be evicted in the next 30 days to being unsure how one will make the next rent or mortgage payment, staying with family or friends between jobs, couch surfing to avoid staying in a shelter, being in a shelter, in a group home or facility without a clear place to go upon release, staying in one’ s car or any other location not meant for human habitation, or sleeping on the street. All but two of the listed conditions, awaiting or anticipating eviction and being unsure of whether or how one will make the next rent or mortgage payment, are defined as “unhoused” or “homeless/houseless.” But we have no valid or reliable means for counting and tracking all those experiencing these situations. The only regular measure we have of being unhoused is the Point-In-Time (PIT) count census of the homeless. The PIT count is taken on the last Wednesday to Thursday 24-hour period in January each year. Sheltered homeless are counted via the Housing Inventory Count and street and emergency shelter homeless are counted by volunteers who do their best to find all the street homeless in their area on the day of the count.

Analyses of the PIT count estimate that true numbers of unhoused individuals are 2.5 to 10.2

times higher than are reflected in the annual PIT census.27,38 Nevertheless, PIT count data for the two-county region shows both the impact of COVID-19 policies and programs designed to prevent eviction and house the unhoused, and how quickly the end of American Rescue Plan Act funding and programs was followed by a resurgence and even growth in the local homeless population (Figure 33).

Contributing Factors

As part of this study, we interviewed individuals who had experienced some form of housing instability in their lives. We asked respondents to complete a journey map, a timeline of their housing history and major life events. Data from these interviews confirmed research on the kinds of experiences or events that make people most vulnerable to housing disruptions.

Precipitating events are experiences that magnify underlying vulnerabilities and barriers to housing under certain and specific market conditions, such as when (affordable) housing is scarce, and can result in housing precarity or loss of housing. Our interviewees’ paths toward unstable housing were shaped by a wide range of precipitating events including but not limited to:

• Multiple or serial moves as a child or adolescent.

• Living in crowded housing or housing that did not fit the number of occupants or their needs.

• Experiences of domestic and/or sexual violence.

• A change in one’s relationship status (resulting from a break-up or divorce).

• Past or current substance or alcohol use disorder.

• Incarceration.

• Acute and chronic mental illness.

• Unemployment or barriers to employment.

• Loss or lack of transportation.

Study participants commonly experienced multiple or simultaneous precipitating events that were compounded by, or that continued to

compound, precarious housing. The vignettes below illustrate the dynamic interplay between individual characteristics, common adverse circumstances, and the structural conditions and constraints created by the region’s housing and homeless systems.

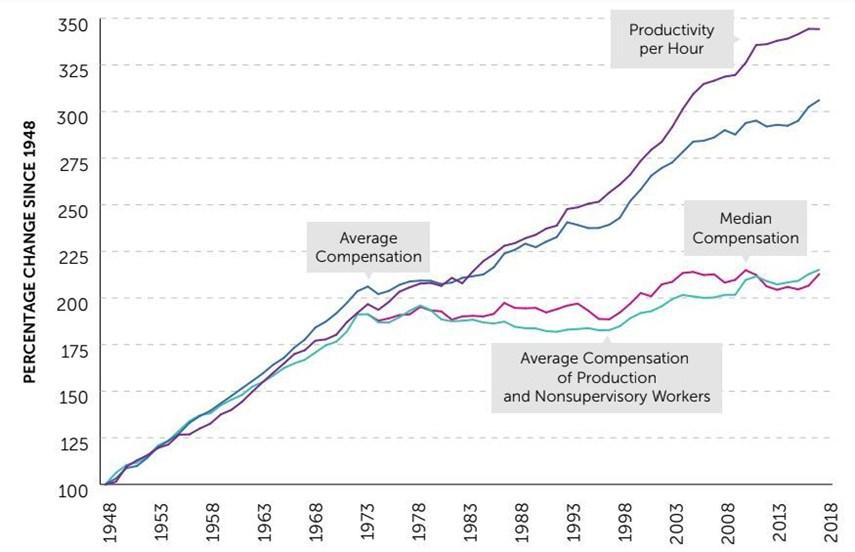

Constraints within the Housing Market

Market conditions (rising rents, high security deposits, rental application fees, high interest rates on mortgages, lack of affordable private housing stock, aging or limited public housing stock) are the underlying causes of homelessness and housing insecurity. Households with access to ‘safety nets’ and ‘backup plans’ may be able to avoid experiencing severe crisis that results from the structural conditions of labor and housing markets, but that does not mean they will come through without lasting emotional harm and reduced financial security.

Faye (age 63) and her husband were already “over their heads” when they purchased a home in 2001. First-time homebuyers with little money to put down, the couple’s mortgage came with a high interest rate. By 2008, “everything was hitting the fan” for Faye and her husband: the small business he owned began to suffer from his lack of acumen and from a tanking economy.

As the only one working, Faye did not earn enough to pay for the house. Her husband, a functional alcoholic and chronic depressive, “wouldn’t deal with anything:” they fell into foreclosure and separated. Faye’s in-laws covered the security deposit for the townhome where she and her daughter lived for the next five years.

In 2015, Faye began renting a home from a friend who had temporarily relocated to another part of the country; the friend decided to sell the house two years later, leading Faye to her current apartment. Although she would like an updated kitchen or more storage, Faye appreciates that she is in a rental.

Faye’s foreclosure does not appear on her credit report, but she states that she has “PTSD about homeownership.” Although Faye is “definitely in better financial shape now” than she was in the

early 2000s, she would not be able to afford a meaningful down payment without tapping into her retirement account and she does not have the financial resources “to handle the inevitable expenses that come up when you own property.” She declared, “I just don’t want to assume that risk, really.”

In this case, housing market dynamics are the context in which personal challenges and life events shape outcomes: a depressive spouse with alcohol use disorder creates financial strain that leads to foreclosure and divorce, reducing Faye’ s household earning potential to one income. Faye had a stable background, a college education, and strong resilience. She had family who were able to provide resources and a strong social network that even led to housing. As a result, she experienced instability, but no stretch without housing. Still, life events placed home ownership and middle-class wealth creation out of reach. Those with histories of housing instability, mental health, substance use disorder, criminal records, or experiences of domestic or sexual violence, and without strong support networks, lack the resources to weather similar challenging life events.

Multiple Moves and Instability in Childhood and Adolescence

When people are focused on securing their day-to -day existence, that daily survival stress makes it difficult to formulate long-term plans. They may experience feelings of ‘outsiderness’ and isolation. The absence of strong personal relationships and social ties or lack of positive family and community support and feelings of belonging may exacerbate the risk of housing instability or homelessness for some individuals. Being in recovery led Jonathan (age 43) to new insights into how cross-country childhood moves impacted him as a teenager, and specifically his sense of never fitting in with peers who had established friendships with one another in their elementary school years. Jonathan began using and selling drugs “to feel better” and “because that made me important.” The drug trade led to continued instability.

He was often able to avoid living on the street by couch surfing or renting motel rooms: “I had a bunch of ‘friends’ wanting me to stay with them because what I had was what they wanted,” he conceded.

Not having a stable place to live for over a decade translated into “not really sleeping,” which led Jonathan to begin seeking help for his addiction. He shares that he’ s “got 44 guys at the [transitional living facility, plus his case manager at the Family Recovery Court] that I could call on at any time” for advice as he navigates sobriety and reestablishing a relationship with his child. Newfound stability and a sense of belonging he did not have as a child help him stay stable and sober.

Around the time that Kayla (age 27) was a sophomore in high school, her father’s health began to deteriorate. Within two years of his first heart attack, Kayla’s father became too ill to work, her mother began suffering from panic attacks and lost her job as a bank teller, and their home entered foreclosure.

Kayla, her parents, two sisters and an infant nephew began living in hotel rooms which she described as “suffocating.” Kayla graduated and began working and, with her wages,

supplemented her mother’s income from a new but lower paying job to help the family move into a rental home.

Having just lost her own place, Kayla’s older sister and her two children moved in too, but according to Kayla, “It was a mess. The kids came in there and tore up everything, okay. Everything. The front fence, everything to the point where the owners kicked us out.”

Rather than crowding into a hotel with her family again, Kayla moved into a co-worker’s apartment but soon learned that her new roommate was in arrears. “Like, I was just digging myself into another hole,” she realized. Kayla’s instability started with her parents her sophomore year of high school and 11 years later she still struggles.

Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to long-lasting and negative effects from even short spells of housing insecurity or without housing. Several narratives, like Jonathan’s and Kayla’s, included first bouts of housing instability or frequent moves while still in the care of parents. For some, this seemed to normalize the sense that housing insecurity is just a part of life.

Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Assault

Kayla, who was not officially on her co-worker’ s lease, was fearful of losing her housing again, which led her to accept her boyfriend’ s sign for an apartment of their It was great. Like life was amazing,” for And then it went bad.”

You know, he became abusive...It

After a particularly violent attack resulted in her boyfriend’s arrest, Kayla showed the police report to her landlord and had him removed from the lease. He continued to visit Kayla who, at the time, was pregnant with his child. Because he had been barred from the complex, Kayla was ultimately

Kayla returned to live with family, which meant a return to crowded housing. Asked how many family members are currently in the home, Kayla Kayla would like

to live with just her son and mother and wants her sisters to be more self-sufficient in meeting their own housing needs but is primarily focused on avoiding another eviction if they cannot make rent. Housing disruptions that began in high school persist with struggles to manage unhealthy relationships and housing stability.

Joanna (age 41) moved from the southwestern part of the state in the early 2000s to attend college and to put distance between herself and her abusive family of origin. Joanna’s tenuous housing was compounded by experiences of sexual violence. After the friend she was staying with decided to sell their home, Joanna took a spare room in the home of a couple she knew. Her housing situation “was safe until basically that night” that she was shoved into a wall and groped by the man someone she thought was a friend who “felt like the brother [she had] always wanted.”

Within two weeks, Joanna moved to an apartment of her own, though she could barely afford it. There, a neighbor’s son stalked and intimidated her. One evening, he forced his way into her apartment and raped her. She returned to her hometown, hours away, because “that was the only way [she] got this guy to stop harassing [her].”

Four months later, Joanna returned to Floyd County and was unhoused for the first time in her life; she has been “transient homeless” ever since. Explaining the assault’s impact on her housing situation, Joanna said “If I can’t feel like I can be safe in my own apartment, I don’t feel safe anywhere.”

Joanna seeks emergency shelter in extreme weather or when she is shuffling around from place to place and getting insufficient sleep. For Joanna, sleep deprivation can exacerbate her mental health conditions; this affects her ability to find and maintain work and, thus, her ability to pay for shelter.

Domestic and sexual violence are precipitating events in which gender and other vulnerabilities (such as poverty, mental illness) and attributes

(race, health) intersect with other social forces to produce disparate or undesirable outcomes.

Women with unstable housing situations may find it difficult to leave abusive relationships or find housing that does not make them vulnerable to sexual assault. Once unhoused, the risk of these events increases. Relative to the general population, unhoused people experience higher rates of physical and sexual abuse.

Relationship Status Change

Jeremy (age 49) connects his housing instability to “bad relationships and, you know, what comes along with that.” A relationship that “goes south real quick,” in Jeremy’s experience, “gets you thrown off and you lose focus on what you ’re doing.” Jeremy was working and renting a house with a girlfriend, but he could not afford the rent on his own. When they broke up, Jeremy fell a month behind on rent, and because his exgirlfriend told the landlord he was doing drugs, the landlord did not allow him to stay.

Like job loss, illness or injury, or the loss of reliable transportation, the breakdown of personal relationships threatens housing security. These challenges may throw a person off their focused efforts to manage earnings and financial commitments, but the loss of a relationship may also mean going from two

incomes to one. A single income for a large share of earners is not enough to afford fair market rents in Clark and Floyd counties. For people without assets or resources to fall back on, a relationship status change increases the likelihood of eviction, foreclosure, or other housing instability.

Past

or

Current

Substance or

Alcohol Use

Disorder, Incarceration, and Acute or Chronic Mental Illness

For Liana (age 38), the petty theft charge she received is, as she explains, “Because being homeless, we have been in situations where we ’ve taken, like, food and things like that. I’ ve gotten caught.” The value of the food and drink Liana stole was under $10, but still required her to explain herself to her current employer. “My job, thankfully, was really laid back about it...My job knows about my situation,” Liana notes.

By contrast, Liana’s husband Richard (age 35) is unable to find work “even [at] places that hire, like, felons.” Incarcerated in 2009, Richard served five years for larceny and struggles to find steady work, both because of his criminal record and because he is living on the street.

For Heather (age 28), lack of stability can trigger a psychiatric condition and lead to hospitalization. She states, “What I’ve learned is that in order to maintain a house, stability is what you kind of have to put yourself in a discipline for.” For Heather, this means taking her medication consistently, working with a therapist, and applying the skills she learned in the New Albany Housing Authority’s (NAHA’s) Family Self-Sufficiency Program.

Heather is acutely aware that people with mental illness are at risk for being unhoused, which she shares has “always been a big fear of mine, especially when I was diagnosed.” If she loses access to public housing, Heather would not be able to move back in with her mother. Because of her mother’s substance use, this home is “not a safe environment.”

Prior criminal convictions pose a barrier to housing access in both the private rental market and for public housing. Prior criminal convictions also shape housing access through their impact on employment. “You would not believe how much money I wasted” paying rental application fees, Jonathan lamented, “for them to run my name and see that Level Four [felony drug charge] and be like, ‘Oh, we don’t rent to people like you.’”

NAHA’s Family Self-Sufficiency program and St. Elizabeth Catholic Charities’ domestic violence shelter and rapid rehousing program are a few of the programs that support people in need and teach them to use available resources as they build resilience skills.

Transportation

Heather (age 28) noted that it was often difficult to coordinate transportation if, for example, bus schedules did not align with the hours during which service providers accepted applications or if a ride was “stuck waiting” because she could not predict how long she might be at an appointment.

Serena (age 54) described how she tried to schedule all the rides she might need from a local social service provider early in the month

“because they run out of money right towards the end of the month.” Serena needs to provide a medical cab service with two days’ notice to arrange transportation to her doctor’ s appointments.

During the times he was without a car, Seth (age 34) relied on rides from whomever might randomly be able to drive him, but there was always a cost. Seth shared, “If you had something [money, drugs] that they could benefit off of, they would give you a ride. If you didn’t have anything, you were stranded or walking.”

Travis (age 41) noted that TARC’s limited bus routes in New Albany pose a particular challenge to those who rely on public transportation to get to and from service providers who are not centrally located in the city’s downtown.

High gas prices and increased commute times are barriers for those who might be seeking affordable housing on the outskirts of Clark or Floyd County, or beyond.

Transportation emerged as a significant barrier to program and housing access. Individuals who do not have access to personal vehicles or who cannot drive rely on public transportation, friends or family, or private ride sharing services to get around. Managing transportation requires significant planning and forethought and available options are not always reliable, feasible, or affordable.

Timing and Adequacy of Service Provision

After a two-and-a-half year wait, Liana was approved for a Section 8 rent subsidy but faces significant hurdles moving from an emergency shelter into the private rental market. Her voucher ($987) does not cover the full amount of the monthly rents she has been quoted ($1100-$1200) for one-bedroom apartments. The list of properties that she received was outdated. Liana recounts, “A lot of the ones I called

aren ’t accepting Section 8 anymore...and then most of the ones I called were just too expensive.”

For individuals seeking help to stave off eviction or stabilize their housing situation, time is of the essence, but interviews reveal cumbersome application processes, long wait times, or assistance that arrives too late or is too little to be of practical use.

Lack of Emergency Shelter for Families and At-Risk Populations

Even though they are married, Richard and Liana cannot stay together at the shelter. Liana stated, “The only thing they let us do as a married couple was eat [dinner] together.” She stated, “We can go outside and smoke and stuff” but “technically we ’re separated” because men and women are housed on separate floors; outside, in the shelter’s backyard, they are segregated by a chain link fence. Liana explains that “it does feel a little bit like jail or being, like, you know, in rehab almost because you don’t get much time at all, like family time, to spend with each other.”

MAP 11: HOUSEHOLDS WITH NO VEHICLE, 2018-2022

Richard describes experiencing the shelter as “kind of the same” as prison, in part because of overcrowding. After getting kicked out after a disagreement with shelter staff, he began sleeping in the couple’s car because “it was more peaceful.” When their car was stolen, Richard began sleeping in parks and other public spaces; when Liana can afford it, they will rent a hotel room. This allows them to stay together in the same space and gives Richard a reprieve from the elements so that he can catch up on rest.

Conclusions

Housing precarity and homelessness manifest as “traumatic human experiences” for individuals.13 However, it is important to recall that the housing crisis is systemic and structural in nature: “the homelessness and housing systems bump up against other [systems]” such as the economy and labor market, the criminal justice system (including courts and carceral institutions), the (private and public) healthcare system, transportation, and government (at all levels).

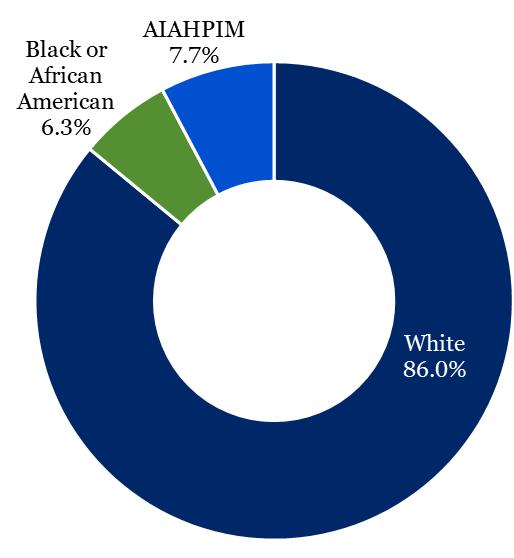

Individual vulnerabilities may increase any given individual’s risk or likelihood of being unhoused; when they interact with structural barriers, individual attributes (or an individual’ s demographic characteristics) may increase this risk, but they are not the causal drivers of housing instability or loss in their own right.

Individuals’ likelihood of experiencing housing precarity or loss of housing increases when personal attributes are met with discriminatory or exclusionary practices or policies, whether formally or informally, institutionally or interpersonally, deliberately or unintentionally.

Housing and social welfare policies in the United States, historically, have attempted to differentiate the ‘deserving’ from the ‘undeserving,’ which has the effect of dehumanizing people who require or seek aid or assistance. Although public attitudes on homelessness have grown more compassionate and liberal over the past 25 years, the tendency to blame individuals remains strong.

Policy responses will remain reactive if we continue to view housing precarity and homelessness as an exclusively personal problem.6 The determinative role of available, affordable housing cannot be understated. The personal challenges described in these stories exist everywhere. But not all communities have growing homeless populations. Moreover, the problems described are only made worse when those reentering the community after incarceration or struggling with mental health conditions, substance use, or those fleeing intimate partner violence or recently divorced and faced with getting by on one income do not have access to safe affordable housing.

Land Banks

Legal Structure Government or quasi-public entity, or public mission nonprofit.

Governance Board of directors appointed by local government.

Mission Return vacant, abandoned, foreclosed or taxdelinquent properties to productive use to stabilize neighborhoods and stimulate development.

Mechanism

• Take temporary ownership of land and/or vacant properties.

• Clear title/encumbrances (reduce transaction costs).

• Sell to end-user.

Geographic Focus County or municipality.

Acquisition Tax foreclosure/delinquent tax lien purchase.

Disposition

Private market (often for-profit developers).

Operational funding Grants, property sales income, loans, revenue bonds, tax recapture on disposed property.

Community Land Trusts

Private nonprofit.

Tripartite board (1/3 CLT residents, 1/3 community residents, 1/3 housing industry stakeholders).

Preserve affordability in perpetuity, by taking land out of the private for-profit market.

Promote democratic power through community control of property.

• Take ownership of land and/or property.

• Create encumbrances to market-driven transfers to protect affordable housing and other community-dictated uses.

• Hold land and or property in trust in perpetuity for disposition dictated by community (community control).

Neighborhood-level or scattered site across a municipality or county.

Municipal transfer or private market purchase.

Homeowners (often first-time) and some renters.

Grants, rental or leasehold payments, municipal subsidy.

Mitigating the negative effects of gentrification:

• Require a net gain in affordable units when missed-income housing replaces public housing.

• Create opportunities for long-term residents to remain in their neighborhoods after urban revitalization.

• Provide low-income residents with improved access to public services and other resources.

Avoiding the inappropriate prioritization of housing policy objectives:

• Leverage capital market conditions accommodating housing development in diverse urban neighborhoods.

• Ensure mixed-income housing development projects are visible and exposed to public scrutiny.

• Identify means of valuing the social benefits of mixed-income development relative to the public costs.

Including historically underserved groups in planning and development decisions:

• Seek out mixed-income housing development opportunities that stem from neighborhood activism.

• Embrace participatory planning processes that search for common values among stakeholder groups.

• Prevent real estate development interests from exerting too much influence over pluralistic policymaking.

Promoting effective long-range municipal planning:

• Clearly articulate the justification for collaboration between municipal government and the private sector.

• Define the causal mechanisms through which mixed-income housing is expected to benefit the underserved.

• Establish unambiguous measures of success that can be monitored and managed over time.

Using well designed and well managed common areas to achieve social policy goals:

• Incorporate attractive common areas into residential environments to facilitate informal interactions.

• Implement programming designed to bring people together in the hopes of building community and trust.

• Enforce community rules and monitor the behavior of all residents in a fair and consistent manner.

Read, Dustin and Drew Sanderford. 2017. “Examining Five Common Criticisms of Mixed-Income Housing Development Found in the Real Estate, Public Policy, and Urban Planning Literatures.” Journal of Real Estate Literature 25(1): 31-48.

Photo by Wes Scott. Ribbon cutting for local Habitat for Humanity home.

Income Breaks Based on Percent of Area Median Income by Family Size 2023

Area Median Income Louisville Metro = $89,800

Source: United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2023. “FY 2023 Income Limits Summary.” FY 2023 Income Limits Documentation System. (https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/il/il2023/2023summary.odn?

STATES=18.0&INPUTNAME=METRO31140M31140*1801999999%2BClark+County&statelist=&stname=Indiana&wherefrom=%24wherefrom% 24&statefp=18&year=2023&ne_flag=&selection_type=county&incpath=%24incpath%24&data=2023&SubmitButton=View+County+Calculations)

Affordable Annual Housing Costs Based on Income by Family Size

income limit)

Low (50% of the median family income) Income Limits

Clark County, IN ERAP Maximum FMRs By Unit Bedrooms

Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. “FY 2024 Schedule of Metropolitan & Nonmetropolitan Fair Market Rents.” https:// www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/fmr/fmr2024/FY2024_FMR_Schedule.pdf

Catalyst Rescue Mission

Our mission is to help end homelessness in Southern Indiana by providing shelter, case management, life skills training, and social services that propel people into housing permanency.

Website: https://catalystrescuemission.org/

Charlestown Housing Authority

The CHA is committed to serving those in need of quality housing through our Public Housing and Housing Choice Voucher programs. The Public Housing program offers one to four bedroom apartments and handicapped accessible apartments as well.

Website: http://charlestownhousing.org/default.aspx

Community Action of Southern Indiana (CASI)

Community Action of Southern Indiana’s programs provide critical support in areas such as financial literacy, education, housing, literacy, energy assistance, and more.

Housing Choice Voucher through CASI: https://casi1.org/housing-choice-voucher/ Indiana Community Action Association

Provides emergency rental assistance and housing counseling.

Website: https://www.incap.org/indiana-housing-stability-program

Jeffersonville Housing Authority (JHA)

JHA’s goal is to provide affordable, decent, safe and sanitary housing to income-eligible residents in the community.

Website: https://www.jeffhousing.com/

New Directions

New Directions helps families overcome obstacles to affordable, safe, sustainable housing in Louisville and Southern Indiana. Offers housing, home-repair, and real estate development programs.

Website: https://www.ndhc.org/

Volunteers of America

Our comprehensive housing programs provide individualized case management to help unhoused individuals and families find safe, stable and affordable housing and give them the resources they need to live a self-sufficient life. Supports the Louisville Metro Area. Website: https://www.voamid.org/services/housing/

Bliss House: 211 E Maple St, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Website: https://centerforlayministries.org/bliss-halfway-house/ Center for Women and Families (Louisville shelter only)

Provides long-term transitional housing for battered women and children. Website: https://www.thecenteronline.org/

LifeSpring: 1036 Sharon Drive, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

New Haven Residences: 2516 Woodland Ct, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Oxford House: https://www.oxfordhousein.org/

Abbeywood: 2424 Abbeywood Court Clarksville, IN 47129

Elysium: 718 Providence Way Clarksville, IN 47129

Trails: 1548 Briarwood Dr. Clarksville, IN 47129

Ebby: 2246 Lombardy Drive Clarksville, IN 47129

Ophelia: 2708 Crums Lane Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Northaven: 1710 Northaven Ct Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Ginsburg: 1992 Ramsey Way Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Serenity House, Inc: 200 Homestead Ave, Clarksville, IN 47129

Website: https://www.serenityclarksville.com/

Bridgepointe Gardens: 3100 Utica-Sellersburg Rd, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Website: https://www.bridgepointegardens.org/

Childplace Family Services: 2420 East 10th Street, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Website: https://childplace.org/service-providers/

Clark County Youth Shelter and Family Services, Inc.: 118 E Chestnut St, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Provides emergency and long-term residential care for youth.

Website: https://www.ccysfs.org/index.php/clark-county-youth-shelter-and-family-serviceprograms

Clark Rehabilitation and Skilled Nursing Center: 517 Little League Blvd, Clarksville, IN 47129

Website: https://www.asccare.com/community/clark-rehabilitation-skilled-nursing-center/ Hillcrest Village: 203 Sparks Ave, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Website: https://www.asccare.com/community/hillcrest-village/ Riverbend: 2715 Charlestown Pike, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Website: https://www.sonidaseniorliving.com/community/riverbend/ River Crossing: 2400 Market Street, Charlestown, IN 47111

Website: https://tutera.com/location/river-crossing-assisted-living-community/?

utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=al+gb&gad_source=1&gclid=EAIaI QobChMI0L2zwa-diAMVSzYIBR1NaRrEEAAYAiAAEgK48PD_BwE

RiverSide Meadows, Independent Living: 308 E Chestnut St, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Riverview Village: 586 Eastern Blvd, Clarksville, IN 47129

Website: https://www.asccare.com/community/riverview-village/ Traditions at Hunter Station: 400 Hunter Station Rd, Sellersburg, IN 47172 https://www.traditionsathunterstation.com/

Vivera Senior Living of Jeffersonville: 2105 Hamburg Pike, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Website: https://viverajeffersonville.com/

Wedgewood Healthcare Center: 101 Potters Ln, Clarksville, IN 47129

Website: https://communicarehealth.com/location/wedgewood-healthcare-center/? utm_source=google&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=gbp-wedgewood

Windsor Assisted Living: 2700 Waters Edge Pkwy, Jeffersonville, IN 47130

Website: https://www.inhcf.com/windsor-ridge/home/

Carriage House Apartments

Federally subsidized community offering affordable one and two bedroom apartment homes and three bedroom townhomes.

Community Action of Southern Indiana (CASI)

Community Action of Southern Indiana’s programs provide critical support in areas such as financial literacy, education, housing, literacy, energy assistance, and more.

Housing Choice Voucher through CASI: https://casi1.org/housing-choice-voucher/

DAV Homeless Veterans Assistance

Offers housing assistance and other services to homeless veterans.

Website: https://www.dav.org/get-help-now/veteran-topics-resources/homeless-veteransassistance/

Holy Family

Offers utility assistance.

Homeless Coalition of Southern Indiana

The Homeless Coalition of Southern Indiana is a non-profit organization actively addressing homelessness in Southern Indiana. We seek to build community collaboration in addressing the issues the unhoused face in our community.

Website: https://www.soinhomeless.org/

Hope Southern Indiana

Hope Southern Indiana empowers individuals & families to reach a higher level of self-sufficiency, while meeting emergency basic needs. Provides crisis rent and utility assistance.

Website: https://www.hopesi.org/

Website: https://www.carriagehousenewalbany.com/

Indiana Community Action Association

Provides emergency rental assistance and housing counseling.

Website: https://www.incap.org/indiana-housing-stability-program

Metro United Way Southern Indiana Housing Program

Through community partnerships, we are working to help individuals in Southern Indiana become first-time homeowners and we are working to keep current homeowners in their homes by addressing safety and repair needs.

Website: https://metrounitedway.org/program/southern-indiana-housing/

New Albany Housing Authority

Website: https://newalbanyhousingauthority.org/

New Albany Trustee

Provides utility, rent, and mortgage assistance and emergency homelessness services.

Website: http://www.natownshiptrustee.org/

New Directions

New Directions helps families overcome obstacles to affordable, safe, sustainable housing in Louisville and Southern Indiana. Offers housing, home-repair, and real estate development programs.

Website: https://www.ndhc.org/

ResCare Community Living

Provides support, including group homes, to adults and children with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Website: https://rescarecommunityliving.com/location/rescare-community-living-communityalternatives-southeast/

Salvation Army: 2300 Green Valley Road New Albany, IN 47151

Provides utility and rent assistance and transitional housing.

Website: https://centralusa.salvationarmy.org/indiana/

St. Mary’s Catholic Church

Offers rent and utility assistance.

St. Mary’s-Navilleton

Offers rent and utility assistance.

Website: https://stmarysnavilleton.com/

St. Vincent de Paul Society of New Albany

Offers rent and utility assistance.

Volunteers of America

Our comprehensive housing programs provide individualized case management to help unhoused individuals and families find safe, stable and affordable housing and give them the resources they need to live a self-sufficient life. Supports the Louisville Metro Area.

Website: https://www.voamid.org/services/housing/

Wells Fargo Veterans Emergency Grant Program

Provides housing/rent and utilities assistance for veterans. Website: https://learnmore.scholarsapply.org/wellsfargoveteransemergency/

The BreakAway: 1514 E Spring St, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://www.breakawaynewalbany.com/contact

Oxford House: https://www.oxfordhousein.org/

Irenic: 2616 Pamela Dr. New Albany, IN 47150

Pops: 930 State Street New Albany, IN 47150

Mariposa: 613 Roseview Terrace New Albany, IN 47150

St. Elizabeth Catholic Charities: 702 East Market Street New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://www.stecharities.org/

Autumn Woods Health Campus: 2911 Green Valley Rd, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://trilogyhs.com/senior-living/in/new-albany/autumn-woods-health-campus/? utm_source=google&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=gbp

Azalea Hills: 3700 Lafayette Pkwy, Floyds Knobs, Indiana 47119

Bennett Place: 3928 Horne Ave, New Albany, Indiana 47150

Website: https://bennettplace.seniorlivingnearme.com/

Diversicare of Providence: 4915 Charlestown Rd, New Albany, Indiana 47150

Green Valley Care Center: 3118 Green Valley Rd, New Albany, IN 47150

Hellenic Senior Living of New Albany: 2632 Grant Line Rd, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://hellenicseniorliving-newalbany.com/

Website: https://lcca.com/locations/in/green-valley/ Lincoln Hills of New Albany: 326 Country Club Drive, New Albany, IN 47150

The Mansion on Main: 1420 E Main St, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://www.themansiononmain.org/

New Albany Nursing and Rehabilitation Center: 201 E Elm St, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://www.familyassets.com/nursing-homes/indiana/new-albany/new-albany-nursingand-rehabilitation-center

Peggy’s Place Adult Life Center: 4919 Charlestown Rd, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://peggysplacein.com/?

gad_source=1&gclid=EAIaIgocChMI8_fy0rCdiAMVQTMIBR0MwARdEBAYAiDIARICXsbw_wcB

Rolling Hills Healthcare Center: 3625 St Joseph Rd, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://communicarehealth.com/location/rolling-hills-healthcare-center/?

utm_source=google&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=gbp-rolling-hills

Southern Indiana Rehabilitation Hospital: 3104 Blackiston Blvd Progressive Care Unit, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://vrhsouthernindiana.com/

Villages at Historic Silvercrest: 1809 Old Vincennes Rd, New Albany, IN 47150

Website: https://trilogyhs.com/senior-living/in/new-albany/the-villages-at-historic-silvercrest/ Villas of Guerin Woods: 1002 Sister Barbara Way, Georgetown, Indiana 47122

Website: https://guerinwoods.org/

https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/Main/documents/HUDPrograms2023.pdf

Capacity Building for Community Development and Affordable Housing (pg. 7)

Grants to national intermediaries to develop the capacity of community development corporations and community housing development organizations to carry out community development and affordable housing activities that benefit low-income families and persons.

Community Compass Technical Assistance and Capacity Building Program (pg. 9)

Competitively awards technical assistance funding from across HUD program offices to organizations to provide technical assistance and capacity building for HUD grantees and other customers.

Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) (Entitlement) (pg. 12)

Funding to help metropolitan cities and urban counties meet their housing and community development needs.

Community Development Block Grants (Non-Entitlement) for States and Small Cities (pg. 15)

Funding to help States and units of local government in non-entitlement areas meet their housing and community development needs.

Community Development Block Grants (pg. 17)

HUD offers communities a source of financing for certain community development activities, such as housing rehabilitation, economic development, and large-scale physical development projects. Loans may be for terms up to 20 years.

Continuum of Care (pg. 19)

Promotes community-wide commitment to the goal of ending homelessness; provides funding for efforts to quickly re-house homeless individuals and families, while minimizing trauma and dislocation; promotes access to and effective utilization of mainstream programs; and optimizes self-sufficiency among individuals and families experiencing homelessness.

Emergency Solutions Grants (pg. 20)

Grants to provide emergency assistance to people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness and help them quickly regain stability in permanent housing.

Federal Surplus Property for Use to Assist Persons Experiencing Homelessness (pg. 21)

Enables States, local governments, and qualified nonprofits to use suitable and available Federal properties which are categorized as unutilized, underutilized, excess, or surplus, to assist persons experiencing homelessness.

HOME Investment Partnerships (pg. 23)

Grants to States, local governments, and consortia to implement local strategies to increase affordable housing opportunities for low- and very low-income families. Participants may use HOME Investment Partnerships funds for housing activities depending on local needs, including tenant-based rental assistance; housing rehabilitation; assistance to homebuyers; acquisition; and new construction of affordable housing.

Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS (pg. 24)

Formula grants to States and local governments, and competitively awarded grants to States, local governments, and nonprofit to provide housing assistance and related supportive services to meet the needs of low-income persons living with HIV/AIDS and their families.

Housing Trust Fund (pg. 25)

Provides funding to construct, rehabilitate, and preserve permanent rental and homeownership housing for extremely low-income families.

Rural Capacity Building for Community Development and Affordable Housing Grants Program (pg. 26)

Grants to national organization intermediaries for rural housing development organizations, community development corporations (CDCs), community housing development organizations

(CHDOs), local governments, and Indian Tribes to carry out community development and affordable housing activities that benefit low- and moderate-income families and persons in rural areas.

Self-Help Homeownership Opportunity Program (pg. 27)

HUD awards competitive grants to national and regional nonprofit organizations and consortia that have the capacity and experience in providing self-help homeownership housing opportunities.

Self-Help Housing Property Disposition Program (pg. 28)

This program makes surplus Federal properties available through sale at less than fair market value to States, their subdivisions and instrumentalities, and nonprofits.

Energy Efficient Mortgage Program (pg. 29)

Mortgage insurance to finance the cost of energy efficiency measures.

Good Neighbor Next Door (pg. 30)

Provides law enforcement officers, teachers, firefighters, and emergency medical technicians with the opportunity to purchase homes located in revitalization areas at a discount.

Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) (pg. 31)

Mortgage insurance for reverse mortgages that provide borrowers, who are at least 62 years of age, the ability to convert some of the equity in their primary residences into fixed interest rate mortgages with single lump sum payments and adjustable rate interest mortgages with monthly streams of income or lines of credit.

Insurance for Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs) (pg. 32)

Under this HUD-insured mortgage, the interest rate and monthly payment may change during the life of the loan. The initial interest rate, discount points, and the margin are negotiated by the borrower and lender.

Loss Mitigation (pg. 34)

Measures that allow lenders to effectively work with delinquent borrowers of FHA-insured singlefamily loans to find solutions to avoid foreclosure.

Manufactured Homes Loan Insurance (pg. 35)

Mortgage insurance for private lending institutions to finance the purchase or refinance of a new or existing manufactured home, a manufactured home lot, or a lot plus manufactured home. It may also be used to construct or install a garage, carport, patio, or other comparable appurtenance.

Mortgage Insurance for Disaster Victims (pg. 36)

Mortgage insurance for victims of a major disaster who have lost their homes and are in the process of rebuilding or buying another home.

Mortgage Insurance for One- to Four-Family Homes (pg. 37)

Mortgage insurance for purchasing or refinancing a primary residence. 203(b) is the centerpiece of FHA’s single family mortgage insurance program.

Property Improvement Loan Insurance (pg. 39)

Mortgage insurance for loans to finance or refinance the alteration, repair or improvement of property, for the purchase and installation of fire safety equipment in existing health care facilities, and for the preservation of historic structures.

Rehabilitation Loan Mortgage Insurance (pg. 40)

Mortgage insurance to finance the rehabilitation or purchase and rehabilitation of one- to fourfamily structures.

Single Family Property Disposition Program (pg. 41)

Disposes of FHA-acquired single-family properties containing one to four units in a manner that expands homeownership opportunities, strengthens neighborhoods and communities, and seeks a maximum return to the mortgage insurance funds.

Single Family Loan Sale Program (SFLS) (pg. 42)

Servicers assign eligible, defaulted single-family mortgage loans to FHA in exchange for claim payment, after which FHA terminates its insurance and pools and sells the loans either in competitive auctions to qualified bidders or, on a limited basis, directly to units of State and local government.

Mark-to-Market Program (pg. 44)

Preserves long-term low-income housing affordability by restructuring FHA-insured or HUD-held mortgages for eligible multifamily housing projects and renewing the project’s section 8 contract.

Mortgage Insurance for Cooperative Housing (pg. 45)

Mortgage insurance to finance new construction and substantial rehabilitation of cooperative housing projects.

Mortgage Insurance for Purchase or Refinance of Existing Healthcare and Multifamily Rental Housing (pg. 46)

Mortgage insurance for the purchase or refinancing of existing multifamily rental housing.

Mortgage Insurance for Rental Housing for the Elderly (pg. 47)

Mortgage insurance to finance the construction or rehabilitation of multifamily rental housing for the elderly and/or persons with disabilities.

Mortgage Insurance for Rental Housing for Urban Renewal and Concentrated Development Areas (pg. 48)

Mortgage insurance for housing in urban renewal areas, areas in which concentrated revitalization or code enforcement activities have been undertaken by local government, or to alter, repair, or improve housing in those areas.

Mortgage Insurance for Supplemental Loans for Multifamily and Healthcare Projects (pg. 49)

Mortgage insurance to finance improvements and additions to, and equipment for, multifamily rental housing and healthcare facilities.

Multifamily Housing Service Coordinators (pg. 50)

Assistance to elderly individuals and persons with disabilities living in Federally assisted multifamily housing to obtain supportive services.

Multifamily Mortgage Risk-Sharing Programs (pg. 51)

Two multifamily mortgage credit programs under which Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and State and local housing finance agencies share the risk and the mortgage insurance premium on multifamily housing.

Multifamily Rental Housing for Moderate-Income Families (pg. 52)

Mortgage insurance to finance rental or cooperative multifamily housing for moderate-income households, including projects designated for the elderly. HUD’s major insurance programs for newly constructed or substantially rehabilitated multifamily rental housing.

Renewal of Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance (pg. 53)

Assistance for extremely low-, low- and very low-income families to obtain decent, safe, and sanitary housing.

Supportive Housing for the Elderly (pg. 54)

Capital advances and contracts for project rental assistance to expand affordable housing with voluntary supportive services for very low-income elderly persons.

Supportive Housing for Persons with Disabilities and Section 811 Project Rental Assistance (pg. 55)

Housing assistance and voluntary supportive services for persons with disabilities, and promotion of community integration for low- and extremely low-income persons with disabilities.

Choice Neighborhoods (pg. 61)

Competitive grant program to transform neighborhoods of poverty into vibrant, mixed-income neighborhoods.

ConnectHomeUSA (pg. 62)

Platform for public-private collaboration to improve educational, employment and health outcomes of HUD-assisted households by narrowing the digital divide.

Economic Opportunities for Low- and Very-Low Income Persons (pg. 92)

Fosters local economic development, job opportunities, and self-sufficiency.

Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP) (pg. 87)

Funding to provide assistance and reimbursements to State and local fair housing enforcement agencies that enforce fair housing laws that are substantially equivalent to the Fair Housing Act.

Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) (pg. 88)

Grants to public and private entities formulating or carrying out programs to prevent or eliminate discriminatory housing practices against all protected class groups under the federal Fair Housing Act.

Family Self-Sufficiency (FSS) Program (pg. 63)

Promotes the development of local strategies to coordinate public and private resources that help housing choice voucher program participants, public housing tenants, and tenants in the Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA) program obtain employment that will enable participating families to achieve economic independence and reduce dependence on welfare assistance and rental subsidies.

Hospitals (pg. 57)

Mortgage insurance to finance construction or rehabilitation of public or private nonprofit and proprietary hospitals, including major movable equipment.

Housing Choice Voucher Program (pg. 64)

Rental subsidies for tenants to rent units in the private market. Includes list of voucher options.

Housing Counseling Program (pg. 59)

Provides regulatory oversight and capacity building to HUD-approved Housing Counseling Agencies and awards grants to facilitate housing counseling services addressing such needs as purchasing or renting a home, preventing foreclosure and eviction, and diminishing homelessness.

Jobs Plus Initiative (pg. 67)

Competitive grant program to assist public housing residents to increase earnings and advance employment outcomes.

Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards (pg. 43)

The standards seek to protect the quality, durability, safety, and affordability of manufactured homes.

Moving to Work (MTW) Demonstration (pg. 68)

Allows selected PHAs to test new ways of providing housing assistance intended to improve costeffectiveness, promote self-sufficiency of assisted households, or increase housing choices for lowincome families.

New Construction or Substantial Rehabilitation of Nursing Homes, Intermediate Care Facilities, Board and Care Homes, and Assisted Living Facilities (pg. 58)

Mortgage insurance to finance the purchase, refinance, construction, or rehabilitation of nursing homes, assisted-living, intermediate care, board and care facilities, and fire safety equipment.

Project-Based Voucher Program (pg. 70)

Rental assistance for eligible families who live in specific housing developments or units.

Public Housing Capital Fund (pg. 71)

Funding for capital improvements to public housing units.

Public Housing Homeownership (pg. 72)

Sale of public housing units to low-income families.

Public Housing Operating Fund (pg. 73)

Formula funding to public housing agencies (PHAs) for operations and management.

Resident Opportunity and Self-Sufficiency (ROSS) Service Coordinators Program (pg. 74)

Grants for supportive services and resident empowerment activities.

Ginnie Mae Multiclass Securities (pg. 94)

Guarantees the timely payment of principal and interest on multiclass securities backed by government-insured mortgages as provided by the terms of the multiclass security.

Ginnie Mae Single-Class Mortgage-Backed Securities (pg. 93) Guarantees timely payments on securities backed by government-insured mortgages.

https://www.in.gov/ihcda/homebuyers/programs/#Archive

https://www.in.gov/ihcda/homeowners-and-renters/programming-for-elderly-and-persons-with-disabilities/ Emergency Solutions Grant: https://www.in.gov/ihcda/program-partners/emergency-solutions-grant-esg/ Indiana Supportive Housing Institute: https://www.in.gov/ihcda/developers/supportive-housing/ Public/private partnership designed to reduce chronic and long-term homelessness. The Institute is an annual training event hosted by Corporation for Supportive Housing and IHCDA focused on helping supportive housing partners develop very affordable housing with access to supportive services to prevent and end homelessness.

Rental Housing Tax Credits: https://www.in.gov/ihcda/developers/rental-housing-tax-credits-rhtc/ Allocates over $15.5M of federal tax credits annually to for-profit and non-profit developers for the construction or rehabilitation of affordable rental housing. All units created through the program must be rented to households at or below 60% of area median income.

Rental Assistance Programs

Housing Choice Voucher Program: https://www.in.gov/ihcda/program-partners/housing-choiceopportunities-hco

Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS: https://www.in.gov/ihcda/program-partners/housing -opportunities-for-persons-with-aids-hopwa/

Continuum of Care: https://www.in.gov/ihcda/program-partners/coc-program/

https://www.rd.usda.gov/files/RD_ProgramMatrix.pdf

Rural Housing Service

Community Facilities Direct Loans, Grants and Loan Guarantees

Community Facilities Relending Program

Community Facilities Technical Assistance and Training Grants

Economic Impact Initiative Grants

Housing Preservation Grants

Housing Preservation Grants (multifamily component)

Individual Water and Wastewater Grants for Colonias

Multifamily Housing Direct Loans

Multifamily Housing Loan Guarantees

Multifamily Housing Rental Assistance Program

Multifamily Housing Tenant Voucher Program

Multifamily Preservation and Revitalization Loans and Grants

Multifamily Nonprofit Transfer Technical Assistance Grants

Mutual Self-Help Housing Technical Assistance Grants

Off-Farm Labor Housing Direct Loans and Grants

Off-Farm Labor Housing Technical Assistance Grants

On-Farm Labor Housing Loans

Single Family Housing Direct Home Loans

Single Family Housing Guaranteed Loan Program

Single Family Housing Repair Loans and Grants

Rural Housing Site Loans

Rural Utilities Service - Electric

Distributed Generation Energy Project Financing

Electric Infrastructure Loans and Loan Guarantees

Empowering Rural America Program

Energy Efficiency and Conservation Loans

Energy Resource Conservation Program

High Energy Cost Grants

Powering Affordable Clean Energy

Rural Energy Savings Program

State Bulk Fuel Revolving Loan Fund

Rural Utilities Service – Telecommunications

Broadband Technical Assistance Grants

Community Connect Grants

Distance Learning and Telemedicine Grants

ReConnect Loans and Grants

Rural Broadband Loans, Loan and Grant Combinations, and Loan Guarantees

Telecommunications Infrastructure Loans and Loan Guarantees

Rural Utilities Service – Water and Environment

Circuit Rider Program – Technical Assistance for Rural Water Systems

Emergency Community Water Assistance Grants

Revolving Funds for Financing Water and Wastewater Projects

Rural Decentralized Water Systems Grant Program

Special Evaluation Assistance for Rural Communities and Households Grant (SEARCH)

Solid Waste Management Grants

Water and Waste Disposal Loans and Grants

Water and Waste Disposal Loan Guarantees

Water and Waste Disposal Predevelopment Planning Grants

Water and Waste Disposal Technical Assistance and Training Grants

www.cfsouthernindiana.com