Hommage à Geor G Baselitz

realisiert von s ie G fried Go H r

Für unseren Freund Johannes Gachnang

realisiert von s ie G fried Go H r

Für unseren Freund Johannes Gachnang

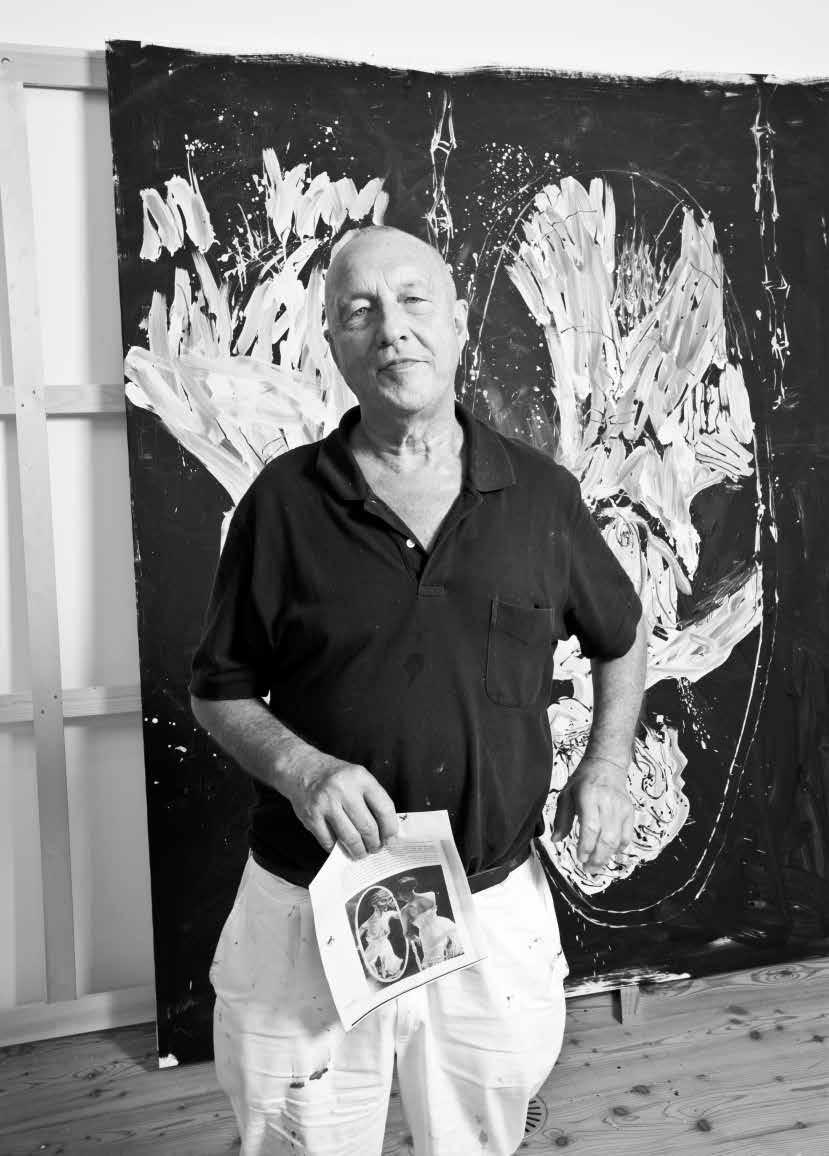

Im Atelier von Georg Baselitz steht ein alter, sichtlich abgenutzter Ledersessel; eine Decke schützt ihn vorsorglich vor weiterer, zu schneller Alterung. Dieses Möbel stand schon in Derneburg, jetzt bietet es eine Aussicht auf den Ammersee. Natürlich stehen Sitze in Ateliers, eine scheinbar banale Beobachtung, aber Baselitz’ Sessel hat ein stattliches Volumen und gleicht eher einem Thron als einem nur nützlichen Inventar. Der Sessel zeigt an, wer in diesem Raum Regie führt, wer etwas zu sagen hat und von wo das Geschehen seine Energie erhält. Aber es hat noch eine andere Bewandtnis mit dem Sitz; denn er symbolisiert die Zeit der Reflexion zwischen den eigentlichen Malhandlungen. Langes Nachdenken, schnell malen – dieses Prinzip bestimmt den Arbeitsrhythmus des Künstlers; es steht quer zu der immer wieder behaupteten emotionalen Direktheit seiner Malerei. Reflexion und Malen bedingen sich gegenseitig und sind unauflöslich ineinander verschränkt. Hier ist kein „Mal-Schwein“ am Werk, das vor lauter Expression seinen Verstand verloren hätte.

Am 23. Januar 1938 wurde Hans-Georg Kern in einem Ort weit im Osten Deutschlands geboren: Deutschbaselitz! Warum der Zusatz „Deutsch“? Weil es auf der anderen Seite eines Waldstückes einen Zwillingsort gab, nämlich „Wendischbaselitz“. Hier wohnten keine Sachsen, sondern Sorben, denen die DDR einen besonderen Status gab, so dass ihnen die Beibehaltung ihrer sorbischen Trachten und Gebräuche erlaubt wurde. Als Hans-Georg Kern sich seit 1961 Georg Baselitz nannte, bezog er sich auf diese doppelte Herkunft, die ein stetiger Bezugspunkt seiner Orientierung und ständige Quelle der Inspiration werden sollte. Das Schulhaus, in dem er aufwuchs, die Landschaft, Spuren aus vorhistorischen und wendischen Schichten, denen er später intensiv nachgehen wird, Volkskunst, Erlebnisse und Prägungen aus Dresden, der alten Residenzstadt und zugleich Zentrum der Malerei seit der Romantik. Um diesen Kern herum legte Baselitz immer neue Kreise, die sich in andere Räume und unterschiedliche Zeiten ausdehnten.

Nachdem Baselitz von der Akademie in BerlinOst wegen „politischer Unreife“ verwiesen worden war, begann er 1957 ein Studium an der WestBerliner Hochschule in der Klasse von Hann Trier. Dieser Lehrer war ein Vertreter des Informel in der westdeutschen Prägung, entwickelte die Methode, beidhändig zu malen, und stärkte auf diese Weise eine Art Strukturbildung im gestischen Farbauftrag. Obwohl Baselitz einige der Möglichkeiten des dort herrschenden Stils ausprobierte, zielte seine Arbeit auf andere Ergebnisse. Es entstanden die „Rayski-Köpfe“ als erste Verfestigungen menschlicher Motive aus dem Farbwucher des Gestischen. Bezeichnenderweise gab ein sächsischer Maler des 19. Jahrhunderts zwischen Romantik und Realismus den wegweisenden Impuls, Ferdinand von Rayski, ein bedeutender Porträtist und Landschafter. Die Dresdner Galerie bot das Inspirationsmaterial für Baselitz. Schon die Wahl seines künstlerischen Ausgangspunkts mitten im sächsischen 19. Jahrhundert musste damals befremdlich bis arrogant wirken. Aber Baselitz fand sich im Westen isoliert und einsam. Hann Trier versorgte den jungen Mann aus dem Osten mit Lektüre-Empfehlungen. Deshalb war dessen Reaktion, andere Außenseiter als Verbündete zu wählen, verständlich und aus seiner Sicht logisch. Das jetzt entstehende Ensemble von Dichtern, Künstlern, Schriftstellern erstaunt wegen der Sicherheit des Zugriffs und der langen Wirkung mancher dieser imaginären Begegnungen. Antonin Artaud nahm einen bedeutenden Platz ein, ebenso Isidor Ducasse alias Lautréamont. August Strindberg als Maler, Charles Meryon, Ernst Josephson und verschiedene mehr stützten die Haltung des Außenseiters und sorgten für Motive, Anregungen und Abwendungen. Die Kunst der Geisteskranken aus Hans Prinzhorns Sammlung in Heidelberg wurde genau betrachtet. Baselitz las viel, sah viel, z. B. in Paris, sammelte dasjenige um sich, was sein Werk nähren konnte. Alles dies mit der ihm eigenen Sorgfalt und Gründlichkeit.

manifeste

Pathetisch und humorlos – das sind die Grundzüge von Literatur im Gewand des Manifestes. Dessen eigentliche Geschichte begann mit dem „Kommunistischen Manifest“ von Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels von 1847/48. Die Künstler des 20. Jahrhunderts haben ständig in Manifesten Forderungen erhoben oder Provokationen verbreitet, vor allem seit die italienischen Futuristen sich in dieser Weise an die Öffentlichkeit gewandt hatten.

Oft waren es Künstlergruppen, die ihre Ziele und Interessen mit Manifesten publik machten. Baselitz hat sein erstes Manifest zusammen mit Eugen Schönebeck geschrieben: „I. Pandämonisches Manifest“ von 1961. Es folgte eine Fortsetzung als „Pandämonisches Manifest II“ im folgenden Jahr. Die Anregung für eine solche Art der Äußerung stammte von Künstlern aus Wien, die damals enge Kontakte nach Berlin hatten. Versehen mit Zeichnungen und Handgeschriebenem, zeigten diese Manifestationen einen sehr persönlich-existenziellen Stil. Antonin Artaud wurde mit der Sentenz zitiert: „Alles Geschriebene ist Schweinerei.“

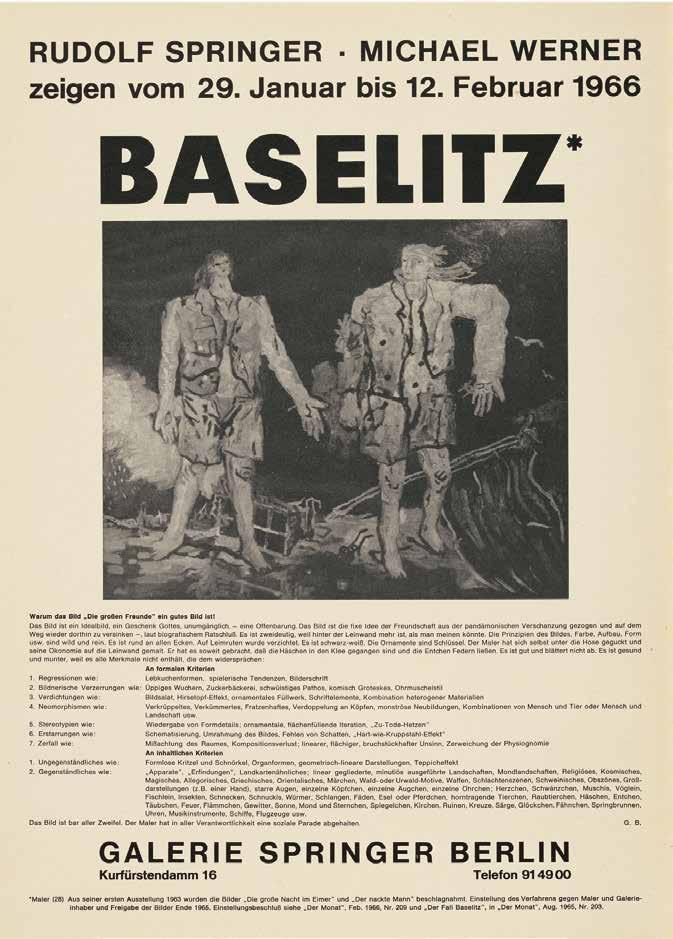

Als Baselitz 1966 für das Plakat seiner Ausstellung in der Galerie Rudolf Springer in Berlin ein Manifest verfasste, hatte sich der Gestus verändert: „Warum das Bild ,Die großen Freunde‘ ein gutes Bild ist.“ Nach den Erfahrungen mit der skandalhaften Wirkung seiner ersten Ausstellung 1963 nahm Baselitz das Existenzielle zurück. Er schrieb dem Bild ironisch die Merkmale zu, die Hans Prinzhorn als Eigenart der „Kunst der Geisteskranken“ herausgearbeitet hatte.

Viel später folgte, manifestartig verfasst, „Das Rüstzeug der Maler“ im Jahr 1985. Immer wieder äußerte sich Baselitz seitdem in lapidaren Texten und gab auch seinen Ausstellungen ironisch-programmatische Titel. Mit der sehr eigenwilligen, assoziationsreichen Sprache, mit der Knappheit der Sätze und der bildnerischen Prägnanz der verwendeten Wörter und Begriffe etablierte Baselitz eine Möglichkeit, jene Öffentlichkeit zu provozieren oder zu unterrichten, die ihm im Laufe der Jahre immer mehr Aufmerksamkeit schenkte.

Georg Baselitz’ 70. Geburtstag, 23. Januar 2008, v.l. Georg Baselitz, Christa Dichgans, Rudolf Springer (1909–2009), Nicole Hackert und Elke Baselitz

In der Reihe der „Helden“-Bilder, die Baselitz 1965/66 malte, erscheint zum Beispiel unter dem Titel „Ein moderner Maler“ eine männliche Figur vor schwarzem Hintergrund auf dem Boden sitzend, die Hände in Erdspalten gefangen. Die abgerissene Kleidung könnte ehemals als Soldatenuniform gedient haben. Blockiert, gequält nach oben blickend, verloren im Niemandsland entspricht die Figur nicht der üblichen Vorstellung von Helden. Seit der Antike galten Menschen mit außergewöhnlichen charakterlichen und körperlichen Kräften als Heroen. Sie galten als Vorbilder, wurden aber auch immer wieder benutzt, um vor allem in Krisen- und Kriegszeiten alle Kräfte von Menschen, Völkern und Staaten zu mobilisieren. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg war in Westdeutschland ein solches Heldenverständnis unmöglich geworden, und selbst das Wort Held verschwand für lange Jahre aus dem Sprachgebrauch. Das war in der DDR anders; denn hier wurde als neue Kategorie der „Held der Arbeit“ eingeführt.

Weder mit der westlichen noch mit der östlichen Haltung zum Heldentum haben die Figuren von Baselitz etwas zu tun. Obwohl es sich nicht um Selbstbildnisse handelt, reflektierte der Künstler seine als Außenseitertum empfundene Lage zwischen Ost und West, zwischen Erinnerung und Gegenwart. Inmitten der Wirtschaftswunderjahre mussten diese Bilder mit den seltsam verletzten, hilflosen Gestalten als fremd und verstörend wirken. Während ihrer Entstehungszeit fanden diese Erfindungen deshalb kaum Resonanz. Aber mit seinen fiktiven Helden oder „Neuen Typen“ fand Baselitz Formulierungen für das Unbehagen, das trotz der glitzernden Konsumoberfläche der Bundesrepublik von wachen Künstlern und Schriftstellern registriert wurde. Während dieser Jahre, die scheinbar ohne Geschichte auskamen, brachten Bilder wie diese das Verdrängte der deutschen Situation zwischen Drittem Reich, Teilung und Zukunft ins Sichtbare. Der moderne Maler kann nichts vergessen, er bleibt bei Baselitz in der Bindung an sein Land stecken. Das Prinzip Teilung beherrscht schmerzhaft auch das Abschlussbild der eigentlichen „Helden“-Phase, nämlich „Die Großen Freunde“ von 1966. Auf dem schwarz-weiß gehaltenen Plakat der Galerie Springer-Ausstellung wird die Isolation innerhalb des Paares der beiden „Freunde“ noch stärker sichtbar. Schon hier herrscht zwischen den Figuren die Fraktur, die später als neues Bildverfahren eingeführt werden wird.

Über Berlin an der Frontlinie zwischen Ost und West und vor allem über die Stadt nach der Teilung im Jahr 1961 gibt es so viel Literatur, dass eine ansehnliche Bibliothek bestückt werden kann. Ebenso zahlreich sind die Werke der bildenden Kunst zur Berliner Situation, die ein Museum bilden könnten.

Die Werke von Georg Baselitz aus den Jahren 1961 bis 1966 gehören dazu, jedoch in einer Art, wie sie Maurice Blanchot in Bezug auf die Bücher von Uwe Johnson beschrieben hat: „Vielleicht könnte der eilfertige Leser und der eilfertige Kritiker sagen, dass in Werken dieses Typs [‚weder politisch noch realistisch‘] die Beziehung zur Welt und zur Verantwortlichkeit einer politischen Entscheidung ihr gegenüber weitläufig und indirekt bleibt. Indirekt, ja. Aber man muss sich gerade fragen, ob ein indirekter Weg nicht der richtige sein kann, um auf die Welt … einzugehen, und auch der kürzere.“

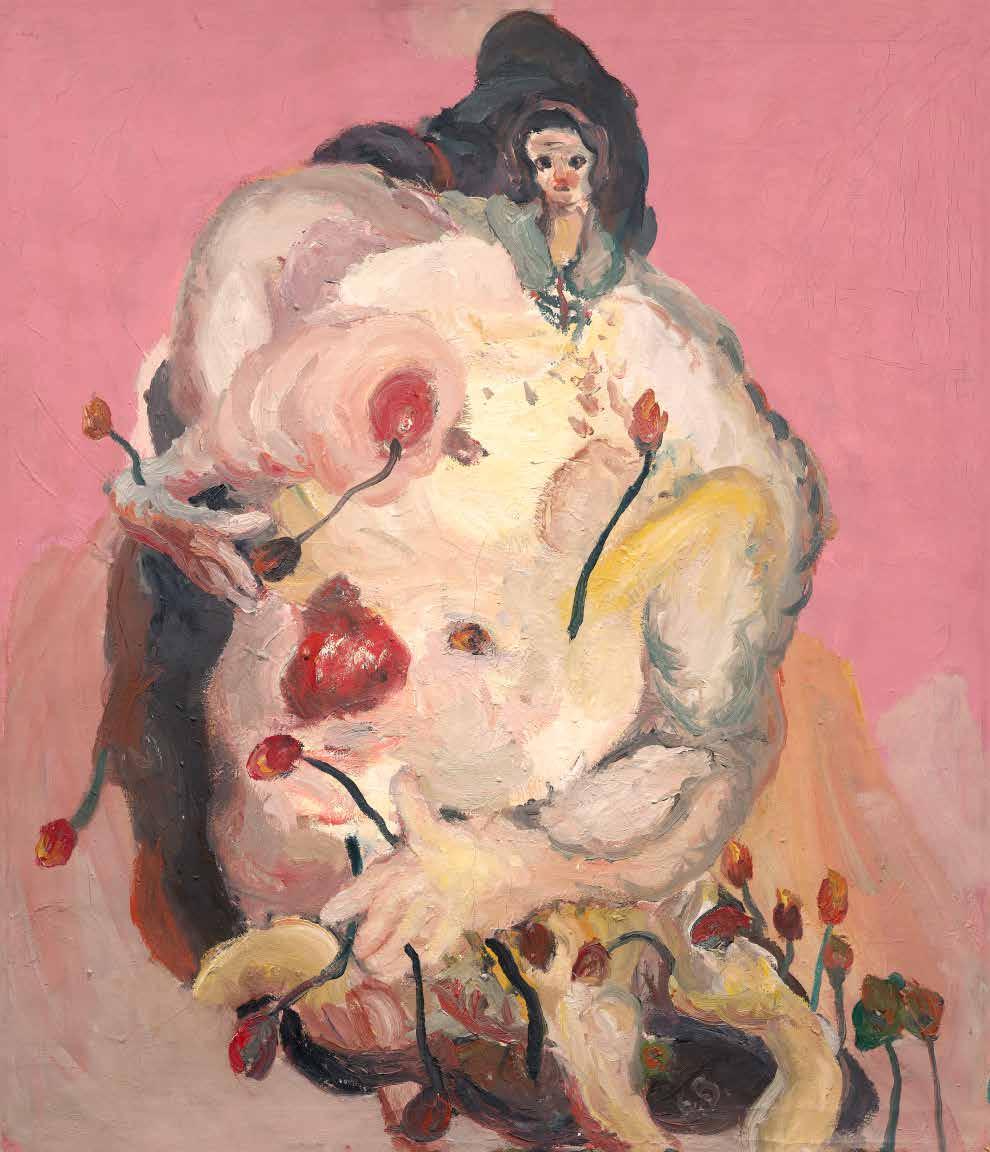

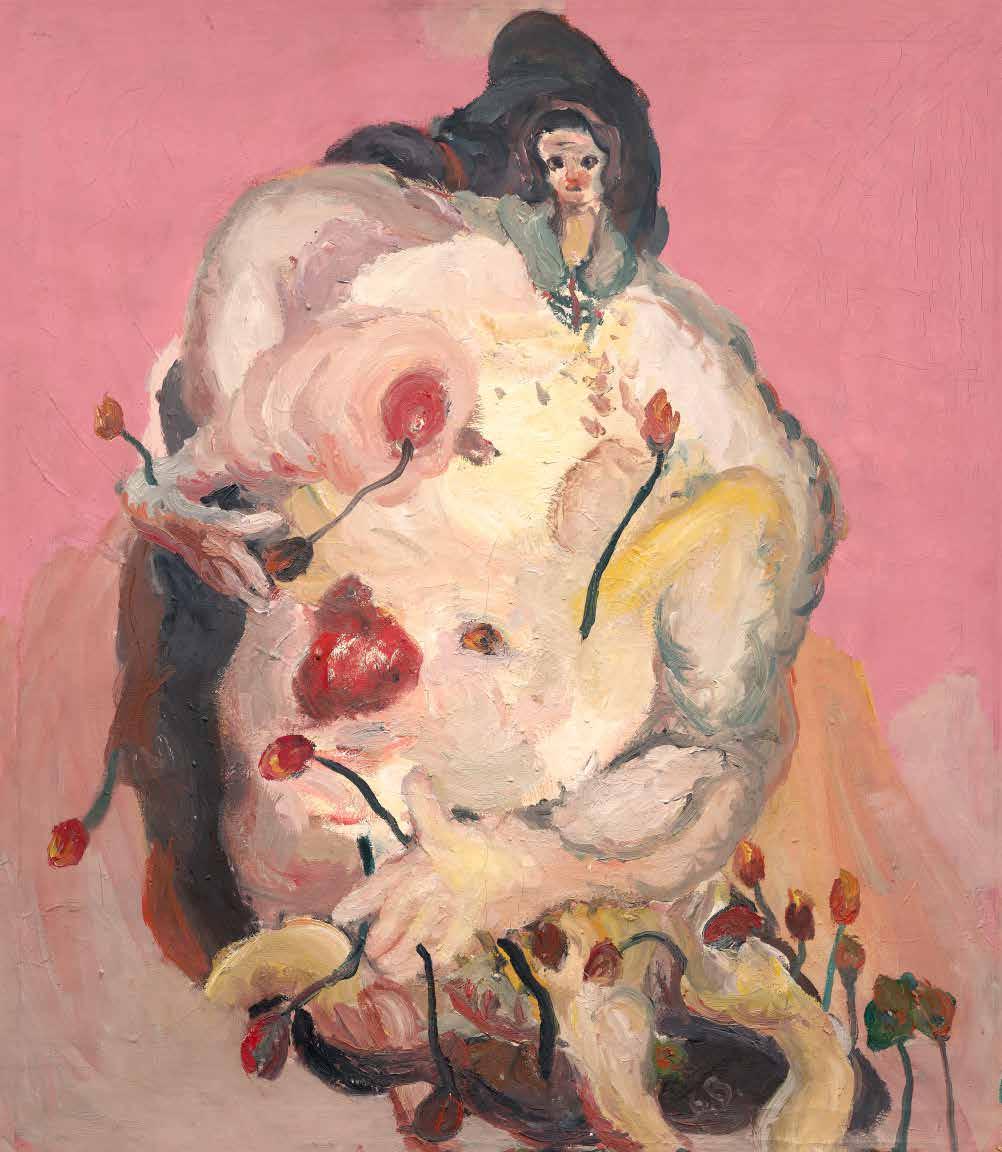

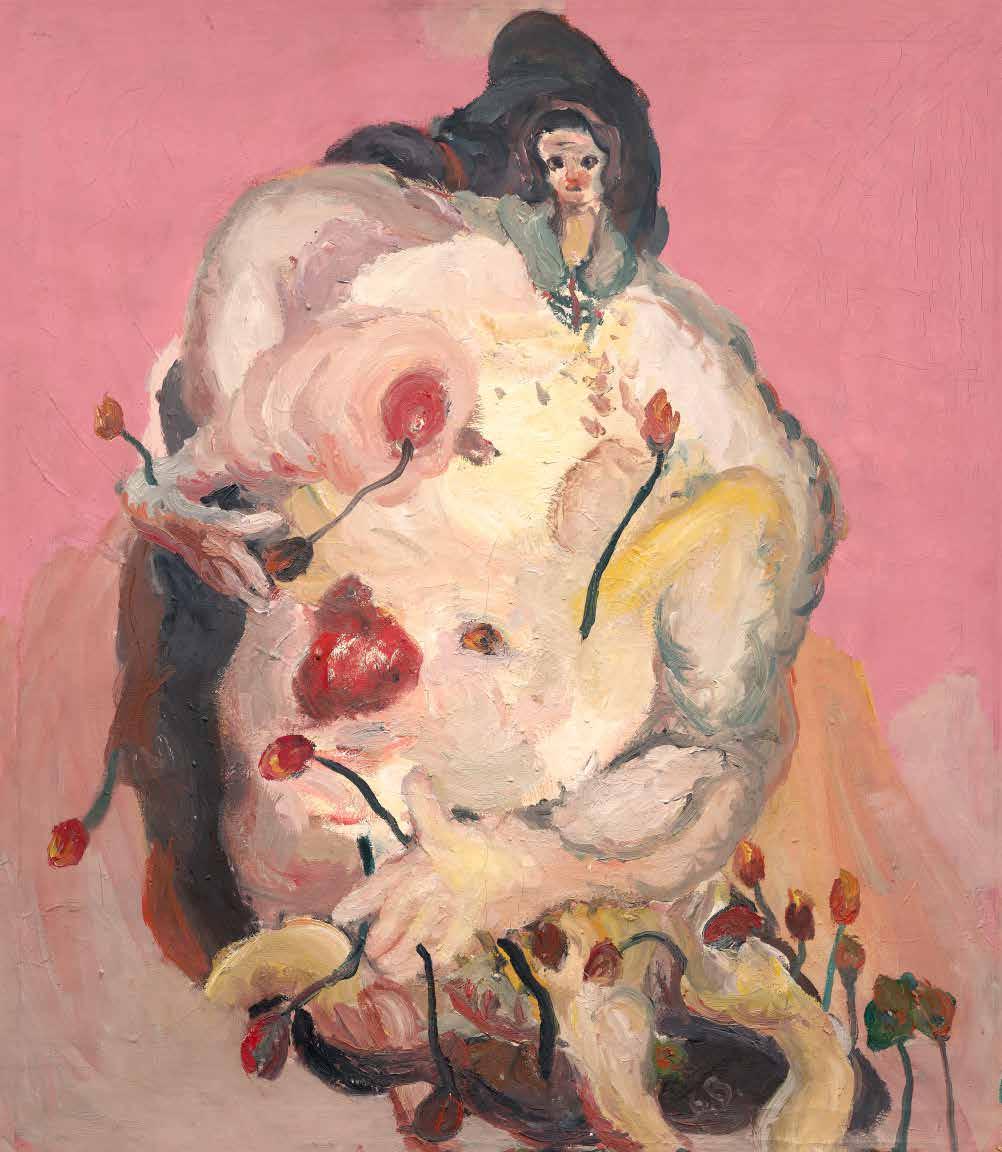

Aus einer Art malerischem Urschlamm ließ Baselitz die Motive hervorquellen, ironisch betitelt, z. B. „Blumenmädchen“. Figuren und Köpfe erscheinen wie gerade geboren, aber noch von Schmerzen gequält und eigentlich fragmentarisch. Kein Neuanfang scheint möglich zu sein, der nicht die unsichtbare Last der Erinnerung mit sich schleppt. Diese wurde obendrein geteilt, schon seit dem Kriegsende 1945, dann 1949, aber noch ein weiteres Mal mit der Teilung Berlins 1961. Weil zum Wesen von Teilung das Fragmentarische gehört, das der Erinnerung eine zusätzliche Bürde auferlegt, bot sich hier für Baselitz der Ansatzpunkt einer ästhetisch-malerischen Strategie.

Verstümmelungen, Frakturen, Verknotungen, Verletzungen, solche Phänomene ließen sich inhaltlich und formal verwenden.

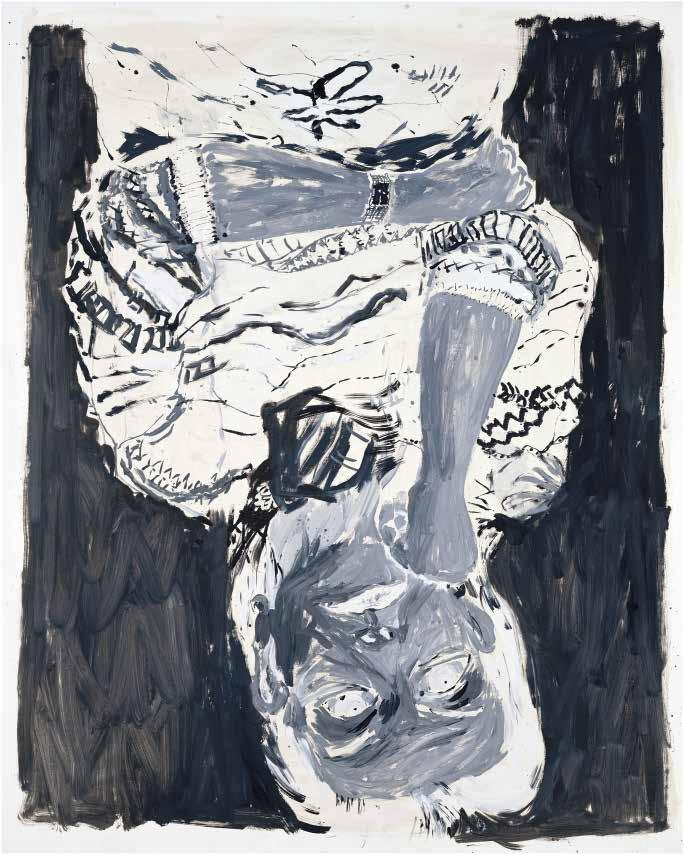

Die Abbilder der Außenwelt fallen auf die Netzhaut in den Augen, und erst das Gehirn dreht das Kopfstehende richtig herum für die alltägliche Orientierung. Wenn Baselitz sich entschließt, seine Motive um 180° zu drehen, stellt er das wieder her, was von außen ursprünglich in unsere Sehorgane als Lichtstrahl eindringt. Dieser Entschluss kam 1969 scheinbar aus einem starken Willen zustande, hatte dennoch einige Vorstufen im Werkverlauf. Abgesehen von einigen kopfstehenden Details in früheren Werken bereiteten die sogenannten Fraktur-Bilder den endgültigen Befreiungsschlag vor, der 1969 mit „Der Wald auf dem Kopf“ gelang. Sofort wurde die Motivumkehr als Trick verunglimpft. In einem höchst aufschlussreichen Gespräch mit Johannes Gachnang von 1975 hat Baselitz sich zu seiner Strategie geäußert. Motive dienten ihm als Anker und Widerstand innerhalb eines gelösten, unverkrampften Farbauftrags. Dieser wurde jedoch technisch mit einem Hindernis verbunden, das als „Fingermalerei“ bezeichnet wurde. Mit ihrer Hilfe konnte die Bildoberfläche zu einer eigenen Wahrnehmungsebene werden, die aber des Motivs bedurfte. Diesem verschaffte der Farbauftrag eine Art farbige Haut, von großer Unruhe lebendig gehalten. Der Betrachter spürt eine unmerkliche, dennoch energiegeladene Vibration. Auf eine bis dahin unbekannte Weise teilten sich Motiv und Malerei in verschiedene Elemente; aber paradoxerweise konnte der Maler ein Band zwischen beiden knüpfen, welches das „neue Bild“ Wirklichkeit werden ließ.

1970

Büsche, 1969

Der Weg von der Malerei in die Dreidimensionalität der Holzfiguren und -köpfe bereitete sich seit 1977 vor. Es waren die großen Linolschnitte, die seit damals entstanden, in denen sich die Motive herausbildeten, aus denen Skulpturen werden konnten. Außerdem bereitete die Technik des Linolschnitts eine Materialbehandlung vor, wie sie gesteigert auch zur Holzbildhauerei benutzt werden konnte. Aus Skepsis gegenüber dem neuen Weg, der mit der ersten Holzskulptur für den Biennale-Pavillon eingeschlagen wurde, nannte Baselitz diese Arbeit „Modell für eine Skulptur“. Aber bald fand er die ihm gemäße heftige Methode, die Holzblöcke zu traktieren: mit Beil, Kettensäge, Hammer, Meißel und ähnlich robusten Werkzeugen. So konnte er die spröden, zerfurchten, gerissenen, urtümlichen Gebilde schaffen, die innerhalb der zeitgenössischen Bildhauerei einen ganz eigenständigen und für viele Betrachter höchst befremdlichen Platz einnehmen. Im Zusammenhang mit der Entstehung dieser Werke hat Baselitz öfters von der Aggression gesprochen, welche er in die Arbeit an den Holzbildwerken investierte. Diese scheint nötig zu sein, um zu einem Punkt vorzudringen, der an den Ursprung der Motiventstehung reicht. Insofern hat das Heraushauen von Figuren und Köpfen aus dem Block etwas Verwandtes mit dem Ausgraben der Archäologen. Allerdings geht es jetzt darum, die Wurzeln menschlicher Regungen freizulegen. Obwohl die Skulpturen bis auf wenige Ausnahmen nichts Individuelles zeigen, treffen sie auf Zustände im Betrachter, die dieser individuell nachempfinden und mit eigenem Erleben vergleichen kann.

Dennoch wurden einige Skulpturen der letzten Jahre selbstbildnishaft gestaltet, z. B. der Sitzende, der als bemalte Bronze vor dem Hamburger Bahnhof aufgestellt wurde. Hier fügt sich die ungestüm behauenen Blöcke zu einer Figur der Melancholie, die wie eine Korrektur des „Denkers“ von Auguste Rodin wirkt, der so oft wie ein Logo vor dem Eingang von Museen platziert wurde. Für die Konzeption einer solchen Skulptur rekurrierte Baselitz auf Werke, wie es sie in der Romanik gibt, nämlich blockhaft, sparsam mit Einzelheiten versehen, aber eine fast magische Präsenz ausstrahlend. Aus Rodin, dem Bewunderer Michelangelos, wurde Baselitz, ein Verwandter der mittelalterlichen Bildwerke, deren Epoche nach dem Jahr 1000 beginnt.

Orangenesser (VIII), 1980/81

Als 1979/80 das 18-teilige „Straßenbild“ entstand, erweiterte Baselitz die Diptychon-Idee der kurz vorangegangenen Ausstellung im Museum von Eindhoven. Als Inspiration für das „Straßenbild“ diente eine sehr seltsame große Komposition von Balthus mit dem Titel „La Rue“ von 1933. Schon das Gemälde von Balthus zeigt eine Situation in einer Pariser Straße, wo eins neben dem anderen geschieht, ohne dass Kommunikation angestrebt würde.

Aus diesem geheimnisvollen Nebeneinander entwickelte Baselitz 1989/90 ein Poliptychon „45“ mit zwanzig Tafeln aus Holz, die in der Art seiner Skulpturen rüde bearbeitet wurden. Weil die einzelnen Bildfelder wie Fenster wirken, entsteht der Eindruck einer Front von Öffnungen, in denen nicht gegrüßt, geschrien, geschimpft oder schlicht gestikuliert wird. Manchmal erscheint nur ein Kopf, als ob er gerade erfunden wurde – roh, direkt, wie am Nullpunkt, der sich jedoch bald ausdehnen könnte.

Nach der Wende, nach dem Ende der deutschen Teilung imaginierte Baselitz in „45“ ein Panorama von Frauen, die heimkehren, von Neuem ins Straßenbild kommend aus ferner sächsischer Vergangenheit und Landschaft. Später wird es die gelben Köpfe der „Dresdner Frauen“ geben. Dies alles hat nicht unmittelbar mit dem „Orangenesser“ zu tun, aber gehört zu seiner Vorgeschichte.

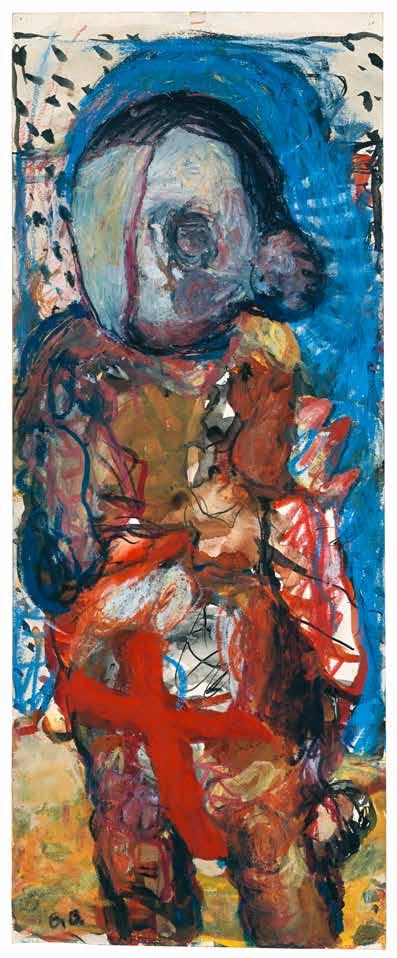

Während die Motive des „Straßenbildes“ von 1980 sowohl in Gegenwart als auch Vergangenheit angesiedelt sind, reagierte Baselitz mit der Serie der „Orangenesser“ und der „Trinker“ auf das künstlerische Umfeld am Beginn der achtziger Jahre. Nicht zuletzt durch seine Wendung zu mehr Expressivität nach den kühlen Farben seiner Ende-der-siebziger-Jahre-Werke bereitete sich in der Eindhovener Ausstellung eine neue aggressive, manchmal geradezu grelle Farbwahl vor. Essen und Trinken, beides elementare Notwendigkeiten für das menschliche Leben, wurden zum Thema in extremen Formulierungen. Indem er das Alltäglichste in eine solche Rohheit und Wut steigerte, antwortete Baselitz auf die gerade im Entstehen begriffene „Malerei der neuen Wilden“, wie sie von den Kommentatoren in Anlehnung an die historische Gruppe der „Fauves“ in Paris um 1906 getauft wurden. Sein Malstil der nächsten Jahre kultivierte nicht das Rohe allein, sondern auch das Hässliche. Dieses wurde zu einem Leitmotiv des Jahrzehnts nach 1980. Er fand Lösungen für eine provokative Malerei, die nicht mit Ironie, Parodie oder politischer Provokation arbeitete, sondern mit einer elementaren Malerei, demonstriert an elementaren Lebensvorgängen. Über die Motive von Orangen oder Trinkgläsern lassen sich umfassende Studien anstellen, die knappen Südfrüchte zu DDR-Zeiten, das verzweifelte Trinken der Bohème böten viel Stoff. Aber die Motive reflektieren in ihrer Unmittelbarkeit und Drastik auch die gedankliche und experimentelle Anstrengung am Beginn einer neuen Werkperiode des Künstlers.

köpfe

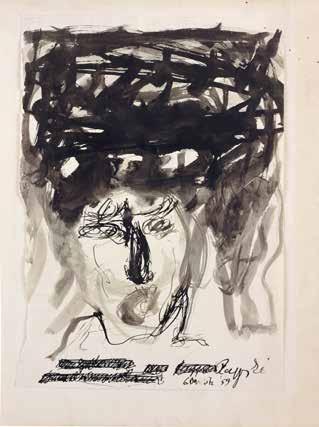

Immer wieder Köpfe. Seit den sogenannten Rayski-Köpfen von Ende der fünfziger Jahre hat Baselitz den menschlichen Kopf auf verschiedenste Weise interpretiert. Als er 1963 einen Körper aus dem Dunkel des Bildhintergrundes auftauchen ließ, setzte er einen grotesken Kopf auf den entblößten Leib, der in seiner übertriebenen Länge an Alberto Giacometti erinnert. Allerdings nimmt die fahle, unangenehme Farbwahl das existenzielle Pathos des Vorgängers zurück in eine ambivalente Atmosphäre. Kopf und Geschlecht bilden hier eine Dopplung, als ob das eine vom andern noch nicht getrennt wäre. Die bald danach entstehenden „Helden“ weisen meist kleine Köpfe auf, anatomisch unwahrscheinlich für die massigen Körper. Erst der Holzschnitt „Großer Kopf“ von 1966 füllt das ganze Blatt mit einem mächtigen Gesicht, das von Ornamenten durchfurcht wird. „RalfKopf“ lässt eine Erinnerung an den Dresdner Freund A. R. Penck lebendig werden. Das bildhauerische Werk behandelt während langer Jahre eine Reihe von Kopf-Motiven wie den „Blauen Kopf“ von 1982/83. Eigentlich trifft der Titel nur für die obere Hälfte der Skulptur zu, denn der Kopf mit den nach oben gerichteten kugelförmigen Augen sitzt auf einem mächtigen Holzblock, der wie ein Energiespender für die visionäre und kraftvolle Physiognomie des Kopfes fungiert. Aus dem ungeformten, primitiven Körperholz steigt etwas in den Kopf, was diesen speist und zugleich die Kraft gibt, sich von der unteren Hälfte zu lösen, wozu natürlich die blaue Bemalung beiträgt. Ungefähr in der gleichen Entstehungszeit schnitt Baselitz den Artaud-Kopf in eine große LinoleumPlatte. Wieder wählte er einen ungewöhnlich langen Hals als „Sockel“ für den von strahlenden Kreisen eingehüllten Kopf. Für dieses Motiv hatte er eine Selbstbildnis-Zeichnung von Antonin Artaud gemäß seiner Vorstellung verwandelt. Wie schon 1963 und in der späteren Skulptur fasziniert der Kopf im Linolschnitt durch die visionäre Suggestion und zugleich durch den Eindruck, dass der Kopf der Sitz des menschlichen Wollens ist, das ebenfalls durch die Strahlenkreise seine Wirkung auf den Raum ausübt. Deshalb erscheint hier wie auch in anderen Werken bei Baselitz das Expressive als Äquivalent für den Willen an sich.

Der Name Baselitz ist Programm, er steht für die Inspiration aus der verlorenen Welt im Osten Deutschlands, die mit der Wende von 1989 plötzlich wieder näher zu rücken schien. Unter dem Eindruck des berührenden geschichtlichen Momentes begann Baselitz die Arbeit an einem vielteiligen Werk auf Holztafeln. Diese wurden schwarz eingefärbt und dann in der Art der großen Linolschnitte, dieses Mal wegen des spröden Materials jedoch in einer besonders ruppigen Vorgehensweise, mit Frauenköpfen als Motiven versehen. Nur eine Tafel zeigt einen Hasen. Am Ende wurden zwanzig Bilder zu einer wandgroßen Komposition zusammengefügt und in zwei Reihen übereinander angeordnet. Nur der lapidare Titel „45“ gibt einen Hinweis auf die historische Reflexion, die mit dem Ensemble verbunden ist. „Bild Nr. 21“ wurde in die Selbstständigkeit als Einzelbild entlassen. 1945 endete der Zweite Weltkrieg, die Frauen hatten den schweren Alltag in dem verwüsteten Land zu bewältigen. Hans Georg Kern war damals sieben Jahre alt und erlebte das Wechselbad der Geschichte als Weg aus Diktatur und Krieg in eine völlig unsichere, orientierungslose Gegenwart. Indem er den Hasen, das Symbol für Unstetigkeit und Ausgesetztsein, in den Zyklus einfügte, gab er einen Hinweis auf sein damaliges Lebensgefühl. Obwohl die Gestaltung der Frauenköpfe bei erstem Hinsehen primitiv wirkt, erschließen sich beim längeren Betrachten Dimensionen, die eine weite Spanne menschlicher Regungen sichtbar werden lassen.

Aufgrund der dunklen Hintergründe und der rabiaten Behandlung der Holzplatten war Baselitz in der Lage, etwas wie eine Schöpfung aus dem Nichts, ein Wiederauftauchen des Menschen nach der Katastrophe zu bewirken. Wie schon in manchen Werken der achtziger Jahre, z. B. in den „Mutter/Kind“-Motiven, setzte er die Hässlichkeit als Stilmittel bewusst ein, um eine Distanz beim Blick in die Geschichte auszuschließen. Nicht durch historisches Räsornieren und Allegorisieren, sondern durch eine direkte, ungeschönte Konfrontation mit der Erinnerung an 1945 konnte eine angemessene bildnerische Realisation erreicht werden. Indem Baselitz das Werk „45. Bild Nr. 21“ nannte, deutete er an, dass dieses Thema noch nicht beendet sein konnte, was schließlich die gelb bemalten Holzskulpturen der „Dresdner Frauen“ von 1990 beweisen. Wenn die Redewendung sagt, dass man in der Erinnerung graben kann, so hat Baselitz schon mit seiner ungewöhnlichen Technik hierfür das richtige Mittel gefunden. Dafür bedurfte es außerdem der stumpfen Oberfläche der Tafeln, die durch die Tempera-Malerei möglich wurde, und das Graben im Holz wie das Graben in einer dunklen, erdigen Malerei aussehen ließ.

Der Paradigmenwechsel, den das 20. Jahrhundert den bildenden Künsten gebracht hat, hieß: Von der Nachahmung zum Fortschritt. Das Neue wurde zum Kriterium für Qualität und Ruhm. Malerei wurde für tot erklärt, der Ausstieg aus dem Bild beschworen, die Überführung der „Kunst ins Leben“ verkündet, das offene Kunstwerk gefordert, die Heirat von „High and Low“ vollzogen, die neuen Medien als Verheißung gefeiert. Im Falle von Baselitz ist es hilfreich, zwischen der Suche nach dem Neuen und der Erneuerung zu unterscheiden. Für eine Weiterentwicklung von Malerei, Skulptur, Graphik, Zeichnung waren Wendungen erforderlich, die er Schritt für Schritt vollziehen musste, um mit seinem Werk auf Zeit und Geschichte reagieren zu können. Seine Erfindungen fanden innerhalb eines gegebenen Rahmens statt, der verletzt oder strapaziert, aber niemals verlassen wurde. Baselitz hat mit der Motivumkehr den Ausstieg aus dem Bild innerhalb des Bildes demonstriert. Er hat so einen innerbildlichen Antagonismus provoziert. Er hat mit den großen Linolschnitten eine neue Kategorie der Graphik etabliert. Seine Skulpturen haben die Bildhauerei weg vom Objekt und hin zum Bildwerk im Sinne der Zeiten vor der Renaissance und außerhalb Europas, z. B. in Afrika, geführt. Er hat das sakral gedachte Polyptychon in eine moderne Gestalt verwandelt. Er hat Kunst über Kunst zum Gestaltungsprinzip erhoben – allerdings nicht als Zitat, sondern als schöpferische Antwort. Er hat Erinnerung als Kategorie für Kunst in ungeahnter Weise fruchtbar gemacht. Er hat die KünstlerSammlung erneuert: Manieristen, Afrika, Fautrier, Picasso, Giacometti, Francis Picabia etc. Er hat das Remix-Prinzip der populären Musik produktiv für Malerei umgedeutet. Er hat die Volkskunst ernstgenommen.

Er hat vor allem Intellekt und Kreatürlichkeit des Menschen in ein neues Verhältnis gebracht.

deutsche kunst?

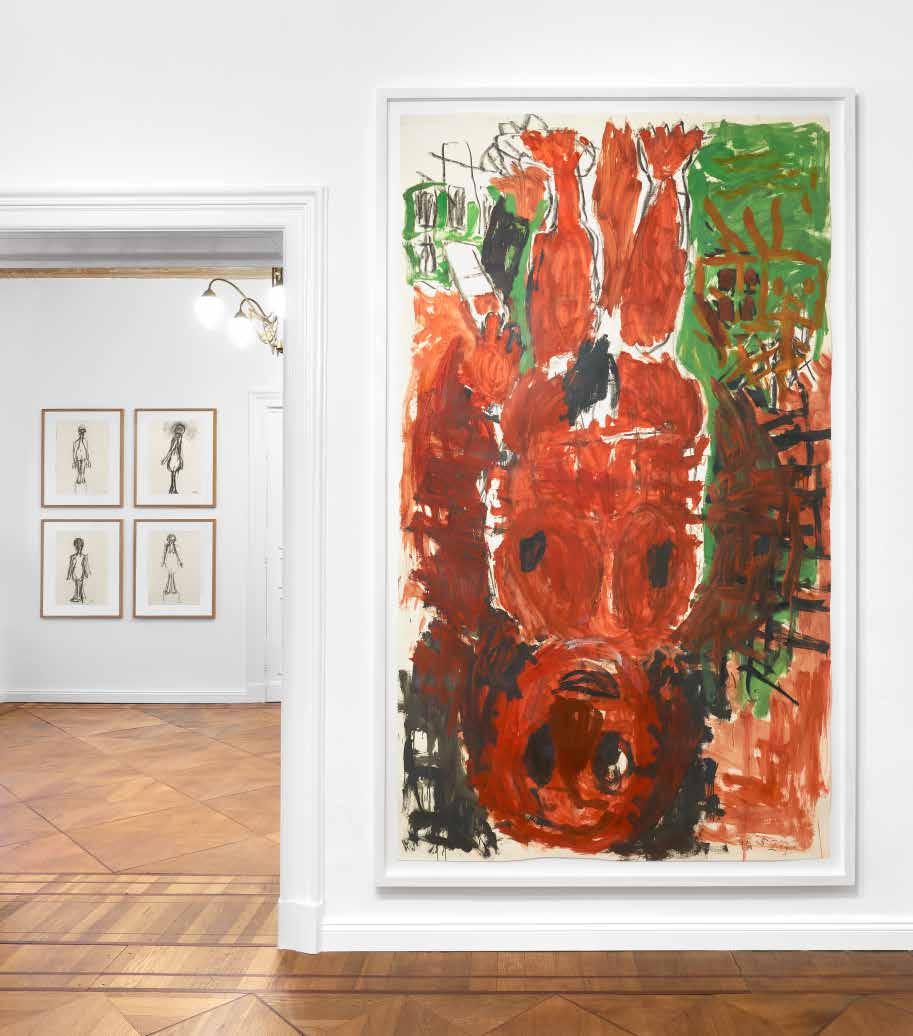

Nach der Mitte der neunziger Jahre dachte ein Kunstbeirat über die Ausstattung des Bundestages im alten Reichstagsgebäude nach. Unter anderem wurde Baselitz eingeladen, Werke beizusteuern; deshalb beschäftigte er sich mit C. D. Friedrich, und zwar am Beispiel eines Bändchens, das den Soldaten des Zweiten Weltkriegs an die Hand gegeben wurde. Es entstanden Gemälde nach Holzschnitten von Friedrich, nämlich „Frau am Abhang“ und „Knabe auf einem Grab ruhend“. Da die Malweise so flüssig und transparent gehandhabt wurde, dass sich der Eindruck von Aquarellen einstellt, vermitteln diese Gemälde den Eindruck von Halluzinationen. Es scheint, dass es Baselitz mit dieser Methode möglich wurde, eine Durchsichtigkeit der Bilder zu verwirklichen, die verschiedene Wirkungen hat. Friedrich erscheint als der deutsche Künstler, der Romantik, Frömmigkeit, Landschaft, deutsche Vergangenheit so suggestiv in Bilder gefasst hat, dass er als Gegenpol z. B. der französischen Malerei um und nach 1800 gesehen werden konnte. Bei Baselitz blickt der Betrachter durch Friedrichs Melancholie und Trauer hindurch, die leicht geworden sind. Er schaut auf Motive von existenzieller Grundsätzlichkeit wie Weltschmerz und Tod. Ohne Geschichte zu illustrieren, boten diese Bilder an ihrem politischen Ort viele Reflexionsmöglichkeiten über Deutschland am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts.

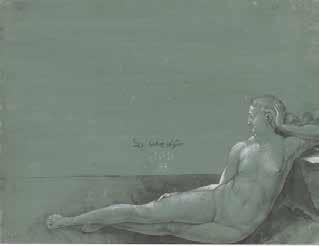

Als Nachklang zu seinem Beitrag für den Reichstag können die Motive nach einer Albrecht Dürer-Zeichnung von 1501 gelten, die in der Wiener Albertina

aufbewahrt wird. Es handelt sich um die Proportionsstudie nach einem weiblichen Akt, wie Dürer ihn schon um 1498 im Kupferstich „Das Meerwunder“ verwendet hatte. Schon hier kann man Dürers Interesse an Proportionsstudien voraussetzen, wie er sie, aus Italien inspiriert,, verfolgte. In dem großen Gemälde von 1998 konfrontierte Baselitz die Frauenfigur mit einem verdunkelten restlichen Bildfeld, in dem ein heller Kreis wie der Mond wirkt. Aus der berühmten Signatur ad bei Dürer wurde ein „Ade Nymphe I“, also ein Abschied von Dürer. Dies lässt sich so verstehen, dass der Optimismus und die Berechenbarkeit der Welt, wie sie Dürer und seine Zeitgenossen angetrieben hatte, hinfällig geworden sind. Wenn gerade dieses Vorbild von Baselitz dekonstruiert wird, ist das grundsätzlich gemeint. Weil die weibliche Figur in krassen Farben erscheint und in ein leeres Dunkel schaut, wirkt sie wie die Zurücknahme des italienisch geprägten Ideals Dürers. Was Baselitz als einen Grundzug deutscher Kunst behauptete – und nicht nur er –, nämlich das Hässliche, hat er gegen Dürer demonstriert. Also lässt sich nicht nur die Friedrich-Arbeit als ein Kommentar verstehen zur Frage, wie deutsche Kunst aussieht, zumal im ehemaligen Reichstag. Die Diskussion über diese Fragen war nach der Wiedervereinigung entbrannt, doch wurde zwischen Ost und West keine Einigung erzielt. Und deshalb wird die wieder hoffähig gewordene Frage nach der „deutschen Kunst“ auf absehbare Zeit keine gültige Antwort finden. Baselitz hat allerdings seinen Standpunkt deutlich gemacht.

Schon in der großen Retrospektive im Guggenheim Museum in New York, die im Jahr 1995 gezeigt wurde, begann Baselitz, sich mit früheren Bildmotiven zu beschäftigen. Diese sehr pastos gemalten, oft mit Weiß versetzten Gemälde begannen Ende 1990 ihren Platz im Oeuvre des Künstlers zu beanspruchen. Es handelte sich nicht um präzise Wiederaufnahmen früherer Werke, sondern um Helden-, Kopf- und Akt-Motive, die aus älteren Erfindungen entwickelt worden waren. Baselitz wählte damals einen Weg in die eigene Bildwelt, wie dies Fernand Léger praktiziert hatte oder ab einen bestimmten Zeitpunkt auch Pablo Picasso. Léger fasst in den Zyklen zu „La Grande Parade“, „La Partie de Campagne“ und „Les Constructeurs“ seine Bildwelt zusammen und gestaltet sie in neuen Kombinationen. Ebenso könnte bei Picasso von der Behandlung und Variation zentraler früherer Motiven gesprochen werden, z. B. von „Maler und Modell“ oder den „sleep watchers“, wie Leo Steinberg diesen ikonographischen Zweig genannt hat. Der jeweilige Fundus aus Motiven und Kompositionsmethoden war groß und ergiebig genug, um daraus neue Werke zu schöpfen. Im weitesten Sinne ist damit das Problem des alternden Künstlers berührt oder die Möglichkeit, eine Summe zu ziehen in einem „Spätwerk“. Wenn man einen Text wie Gottfried Benns „Altern als Problem für Künstler“ zu Rate zieht, gibt es eine Reihe von Phänomenen in späten Werken: größere Freiheit, Experimentierlust, Müdigkeit, Melancholie, Milde etc. Aber Benn bleibt skeptisch, da Beispiele und Gegenbeispiele sich die Waage halten. Aber sein Verweis

auf eine Schrift des Kunsthistorikers Albert Erich Brinckmann, „Spätwerke großer Meister“, führt näher an Baselitz heran. Denn dieser stellte eine ganze Reihe von Beispielen zusammen, die beweisen, dass Künstler seit der Renaissance frühe Werke im Alter neu gestaltet haben und dabei zu ganz erstaunlichen Ergebnissen gekommen sind.

Das gilt zweifelsohne auch für die Remix-Periode bei Baselitz, die im späten Jahr 2005 begann. Der Entschluss, Bilder wie „Die große Nacht im Eimer“ von 1962/63 neu zu malen, gleicht den früheren Entscheidungen, Motive auf den Kopf zu stellen, Holzskulpturen aus dem Block oder Stamm zu hauen oder die Serie der großen Querformate während der neunziger Jahre zu malen.

Aus der populären Musik wurde der entsprechende Begriff in seine Bildwelt transferiert: Remix. Darunter sind Sampler zu verstehen, die vorhandene Titel umformen und neu zusammenstellen. Die eigenen Karten, in diesem Falle: die Bilder, werden neu gemischt.

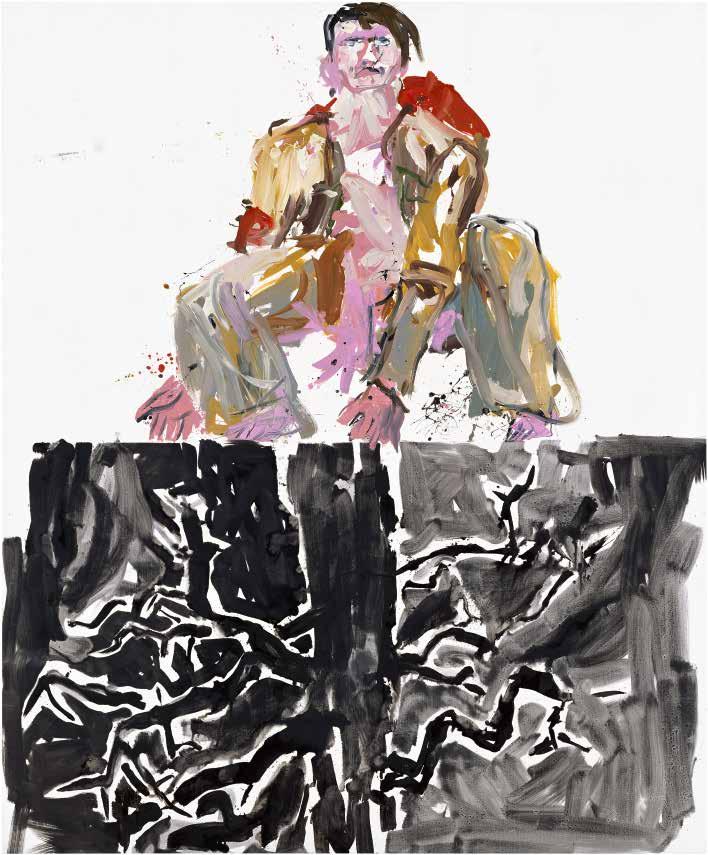

Als Baselitz 2007 „Ein moderner Maler“ von 1966 mit dieser Vorgehensweise erneuerte, fügte er der unteren Bildhälfte die Darstellung eines Waldstücks an. Es verweist auf Ferdinand von Rayskis Waldstudien, die als Vorlage für „Der Wald auf dem Kopf“ von 1969 gedient hatten. Durch dieses Zitat wird sehr deutlich, dass Heimat, die Erde, aus der man gewachsen ist, ein Grundelement für den „modernen“ Maler Baselitz gebildet hat und weiter bildet. „Remix“ ermöglicht eine Erneuerung und zugleich eine Verdeutlichung des früheren „Helden“-Bildes und seiner Intention.

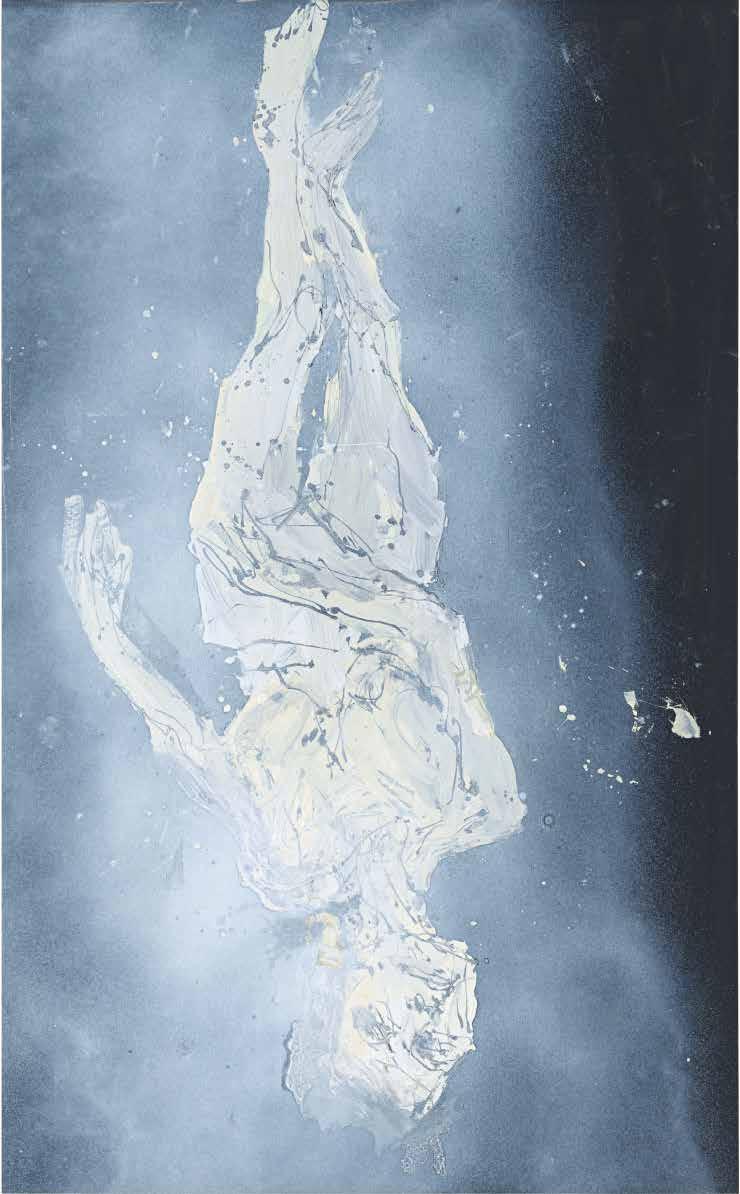

Abwärts I, 2016

Das Wort Zero klingt härter als das deutsche Null oder Nichts. Baselitz hat sich mit einem Zettel, auf dem das Wort steht, photographieren lassen. Er trägt eine Kappe mit der Bezeichnung Zero, die ähnlich auch in einer Selbstbildnis-Skulptur auftaucht. Im Gegensatz zu Künstlern, die von Ende und Tod fasziniert, sogar besessen sind wie Edvard Munch, Max Beckmann, später dann Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol oder Markus Lüpertz, taucht die Reflexion über Vergänglichkeit und Verfall erst seit einigen Jahren ausdrücklich im Werk von Baselitz auf: „Davongehen, Weggucken, Abgehen“ oder „Ohne Hemd auf der Matratze liegen“ heißen zwei Gemälde von 2015. Bald danach malte Baselitz einen weiblichen Akt „Abwärts III“, der in die gleiche fahle, unwirkliche Farbe getaucht ist. In diesem Gemälde korrespondiert die Motivumkehr mit dem ikonographischen Sinn der Reflexionen über die eigene Hinfälligkeit und den näherrückenden Tod.

Im Unterschied zu früheren Darstellungen von Gewalt, Schmerz oder Verletzung scheinen die Körper jetzt in den Bildraum zu verschwinden, weil die Gliedmaßen sich auflösen. Zumindestens bei den Darstellungen mit dem „Zero“-Attribut ist Selbstironie im Spiel. Indem Baselitz nicht zurückschreckt vor Darstellungen wie „Abwärts III“ von 2016, zeigt er nicht nur, wie es ist oder sein wird, sondern auch seine Souveränität gegenüber Ängsten und leidvollen Erfahrungen mit den Körpern. Die Farbigkeit dieser Werkgruppe erinnert an eine weitgehend im Dunklen liegende Bühne; hier könnte ein Stück von Samuel Beckett spielen, den Baselitz während dessen Berliner Zeit erlebt hatte.

Selbstironie spricht auch aus der Verwendung des italienischen Wortes Zero; denn es hat mit dem Spielcasino zu tun, das im Kleinen eine Bühne für das menschliche Schicksal sein kann. Zero bildet aber auch die ständig wiederkehrende Herausforderung für einen Künstler, der sich immer wieder vom Nullpunkt aus neu erfinden muss. Aber auch die Einsamkeit und Isolation des jungen Künstlers in West-Berlin bildete eine erste unvergessliche „Zero“Erfahrung. Der Werkverlauf ist seit damals häufig strukturiert durch „Zero“Situationen, die durch Reflexion und Willensstärke aufgelöst wurden. Hier ging Baselitz ähnlich vor wie sein Freund A. R. Penck, der wiederum die häufigen Stilwechsel von Picasso genau studiert hatte.

Ein Hauch von Resignation mag allerdings auch der „Zero“-Stimmung beigemischt sein, etwas von der Melancholie der Vollendung. Eugène Delacroix hat in späten Jahren ein Gemälde geschaffen, das Michelangelo zeigt, wie er nachdenklich inmitten seiner berühmten Figuren im Atelier sitzt. Hier findet sich ein Bild von Delacroix’s eigener Befindlichkeit im Spiegel eines großen Vorgängers. Aber auch aus der Melancholie der Meisterschaft, aus diesem Zero, kommen wieder neue einmalige Werke ins Sichtbare. Als Baselitz sich mit dem „Zero“-Zettel photographieren ließ, lächelte er.

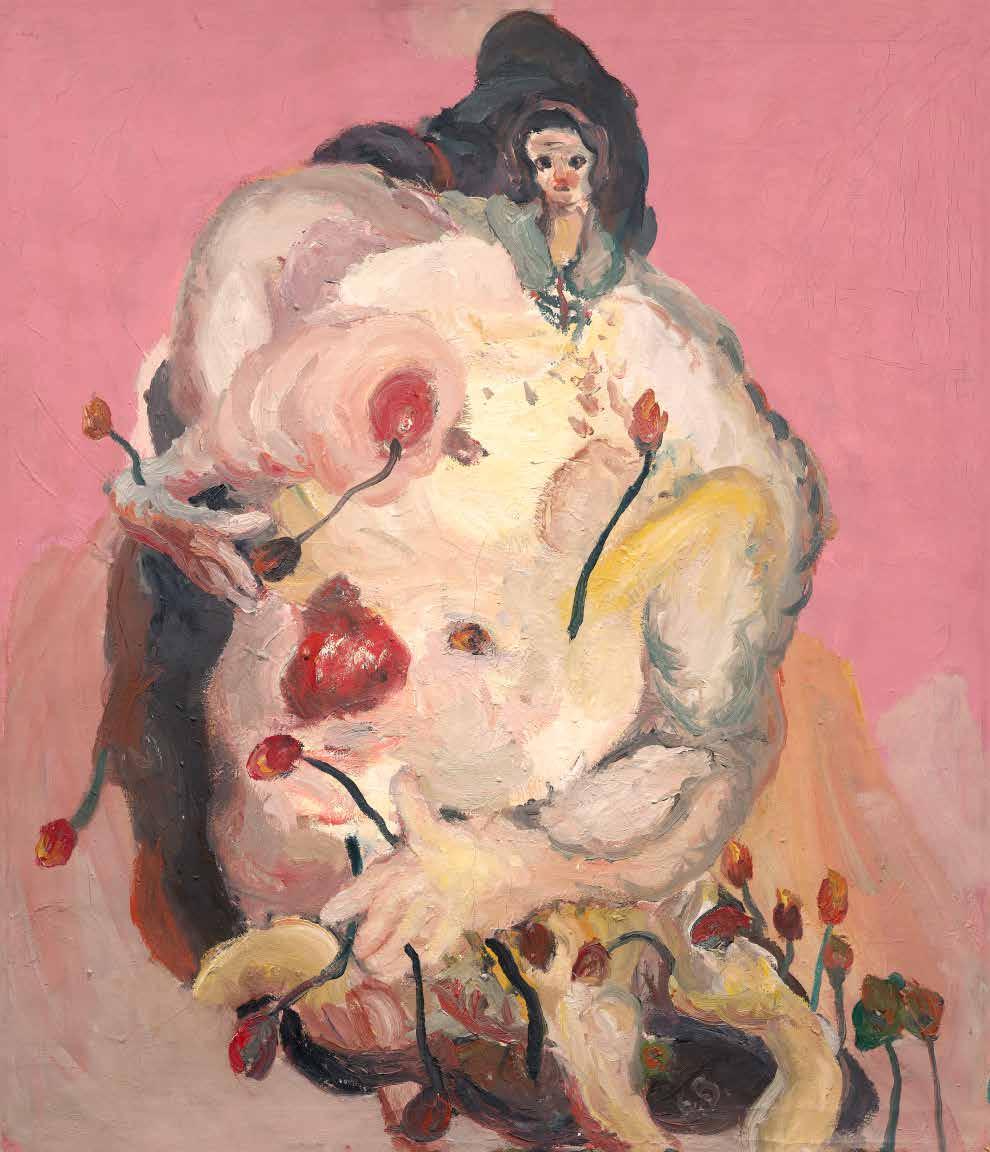

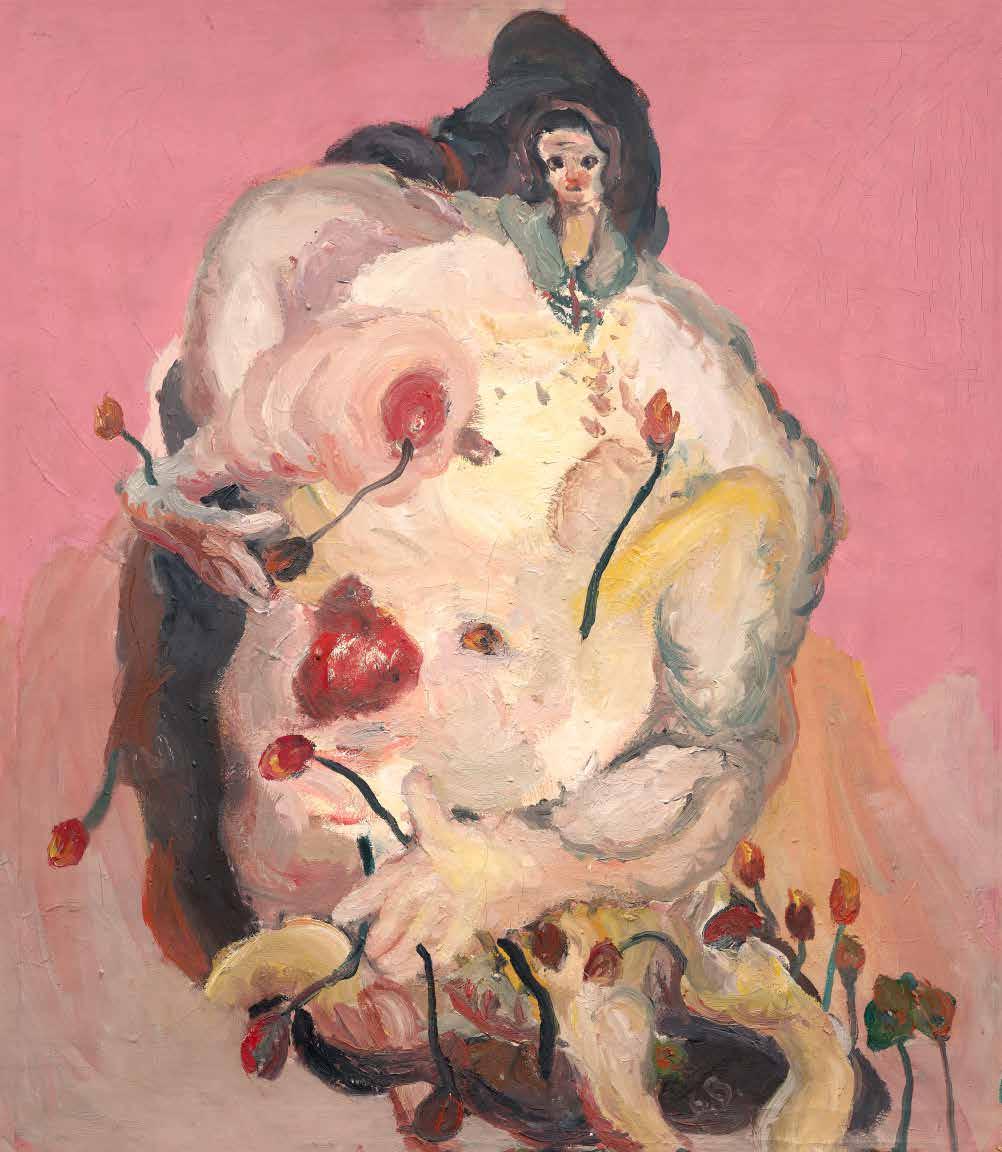

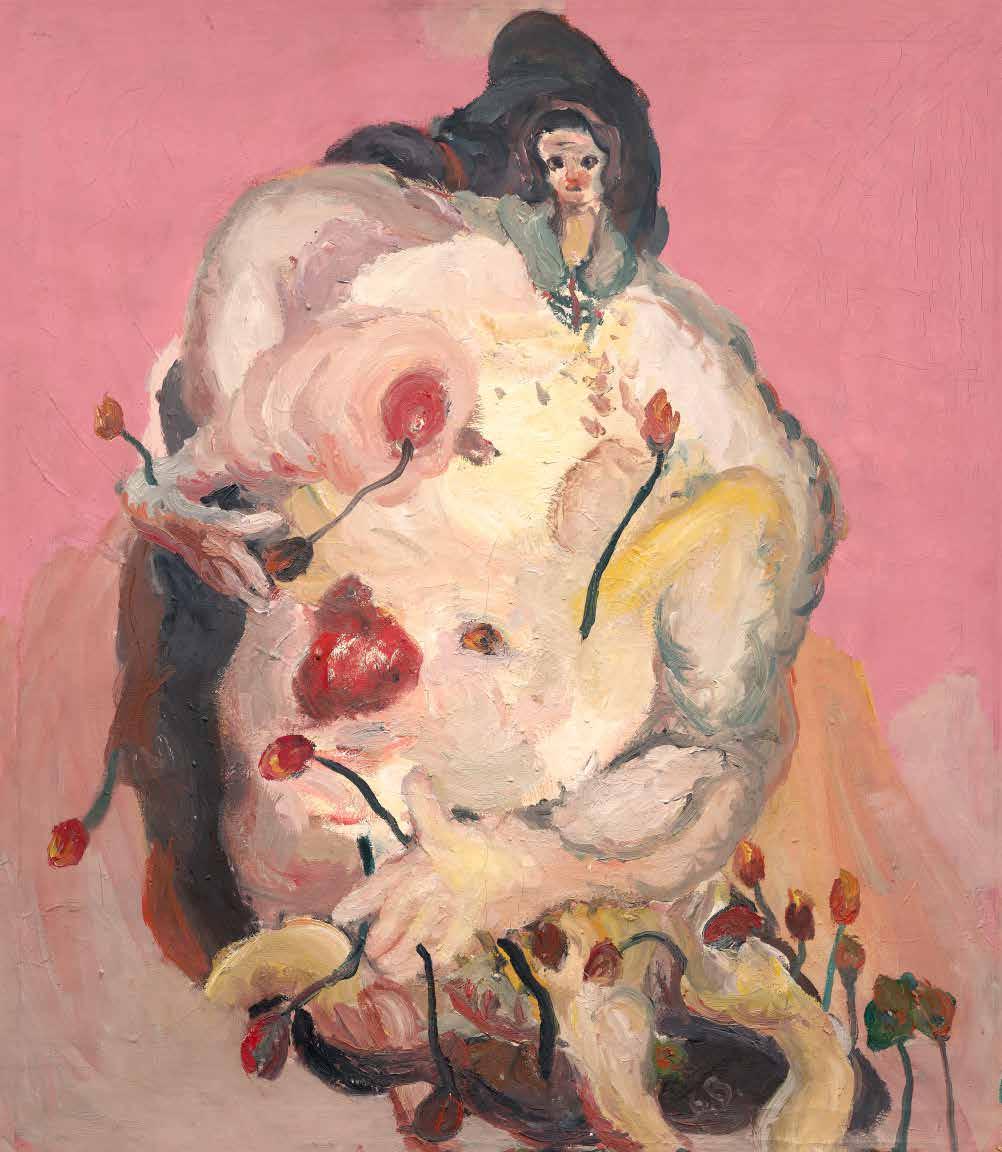

1 Das Blumenmädchen, 1965

Öl auf Leinwand

140 × 120,5 cm

Sammlung Hoffmann, Berlin

2 Kopf, 1963

Blumenmädchen, 1965

Ein moderner Maler, 1966

4 aus ’45, 1989

Rote Mutter mit Kind, 1985

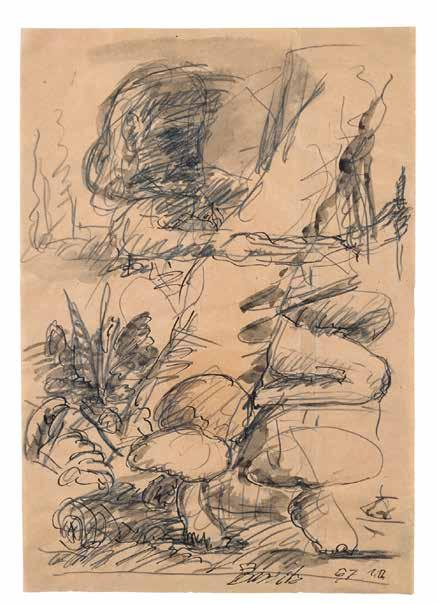

6 Rayski, 1959

Tuschfeder und Tusche laviert auf Papier

29,6 × 21 cm

7 Kopf, 1963

Öl auf roher Baumwollleinwand

140 × 105 cm

Sammlung Hoffmann, Berlin

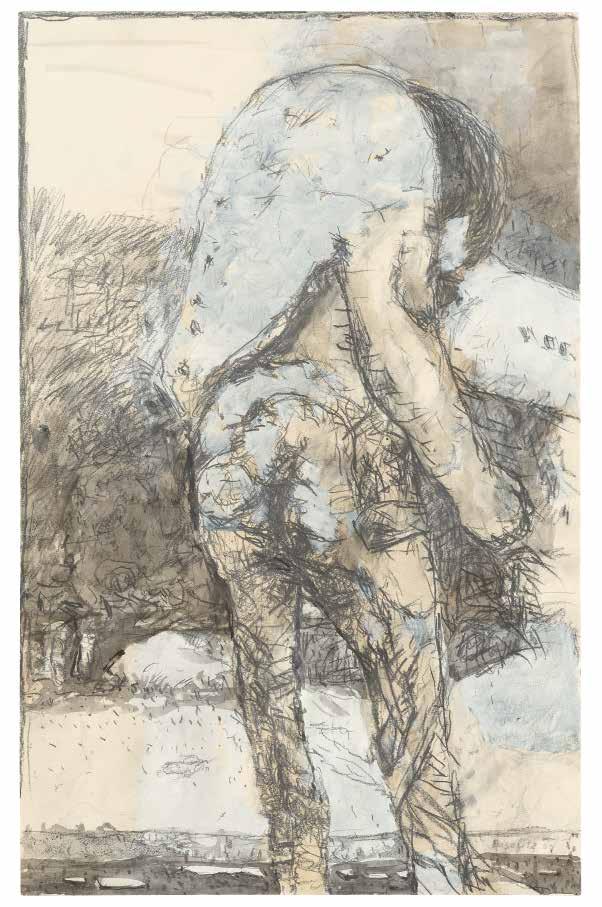

8 ohne Titel (Hommage à Wrubel), 1963

Bleistift, Deckweiß, Tabaksaft

46,8 × 29,5 cm

Privatsammlung

9 ohne Titel, 1964

Gouache auf Papier

46 × 18,5 cm

Privatsammlung

10 Foto: Bruno Brunnet

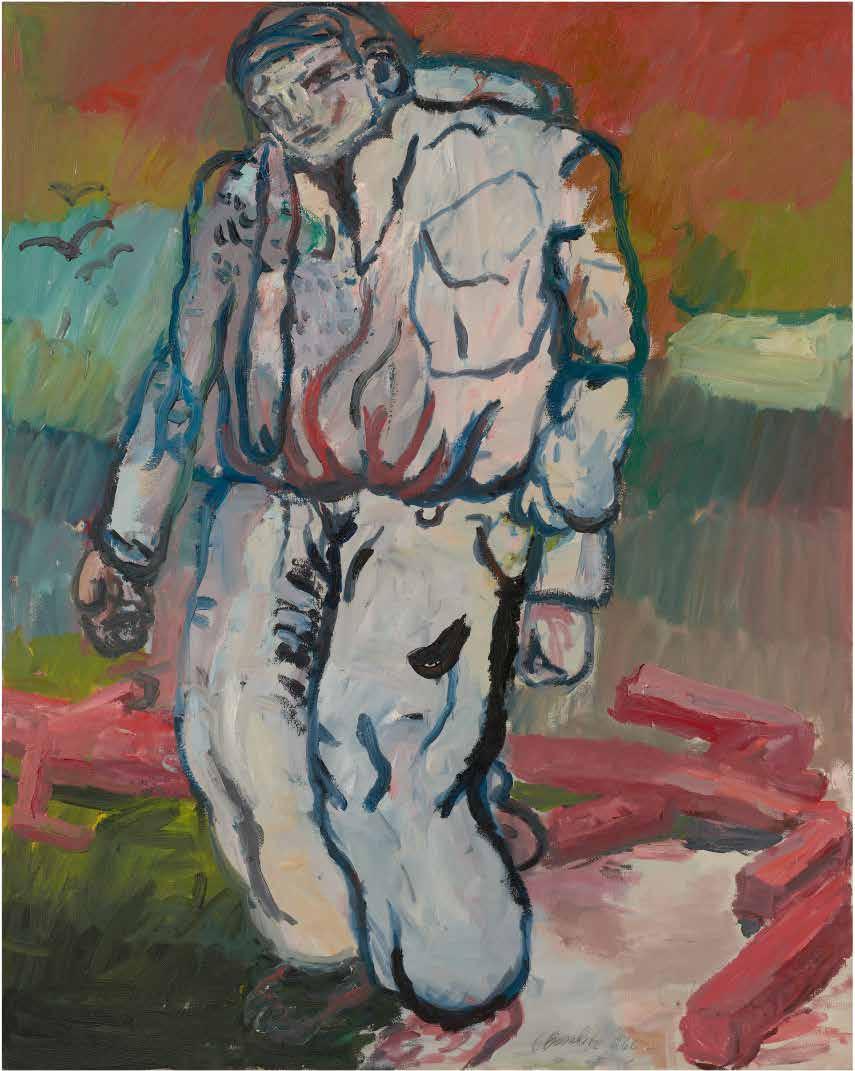

13 Ein moderner Maler, 1966

Öl auf Leinwand

162 × 130 cm

Berlinische Galerie – Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur

14/15 Ein Grüner, 1966

Modern Painter (Remix), 2007 ohne Titel, 1964

16 Zwei Streifen hinterm Baum, 1967

Tusche, Bleistift auf Papier

42 × 29 cm

Privatsammlung

17 Drei Streifen – Der Maler im Mantel (Zweites Frakturbild), 1966

Öl auf Leinwand

250 × 190 cm

Privatsammlung Berlin

18 Katzenkopf, 1967

Öl auf Leinwand

152 × 126 cm

Privatsammlung

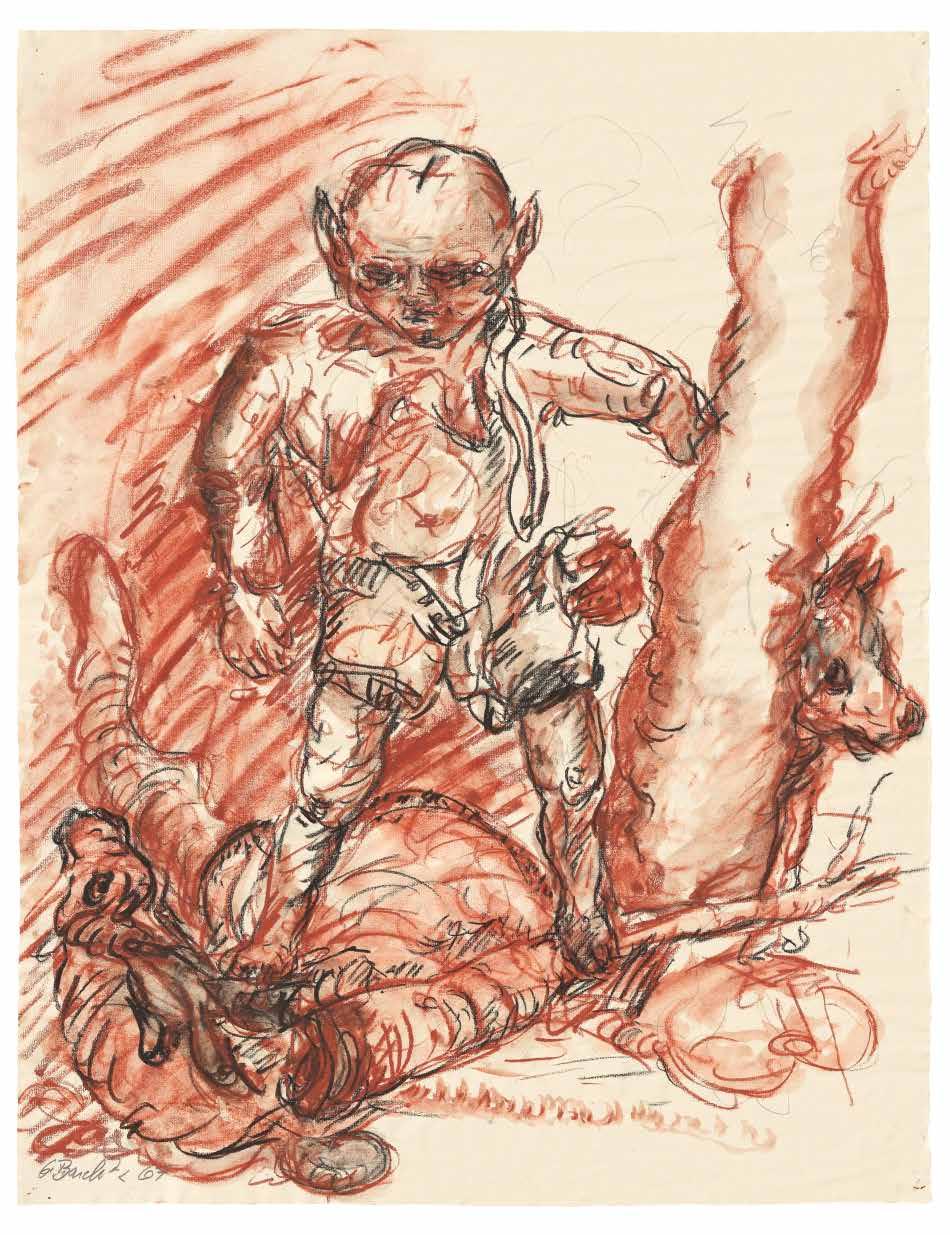

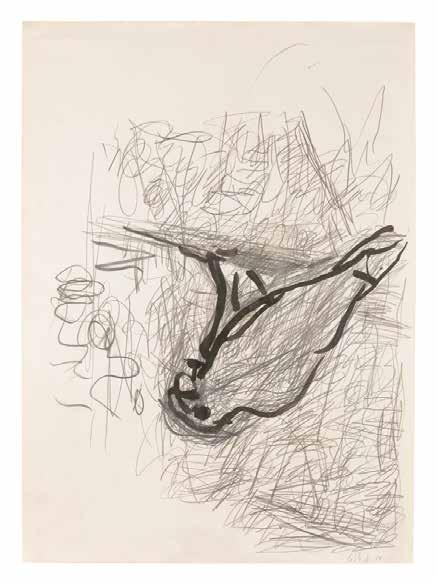

19 Waldarbeiter, 1967

Kreide, Kohle

62,5 × 48,5 cm

Privatsammlung

20 Beatrice, 1964

Gouache auf Papier

48,5 × 31,6 cm

Privatsammlung

21 Ein Grüner, 1966 Öl auf Nessel

162 × 130 cm

ACT Art Collection

22 Der Wald steht auf dem Kopf, 1969 Öl auf Leinwand

250 × 190 cm

Museum Ludwig, Köln

23 ohne Titel (Landschaft), 1970 Öl und Eitempera auf Leinwand

130,5 × 162 cm

Galerie Haas AG , Zürich

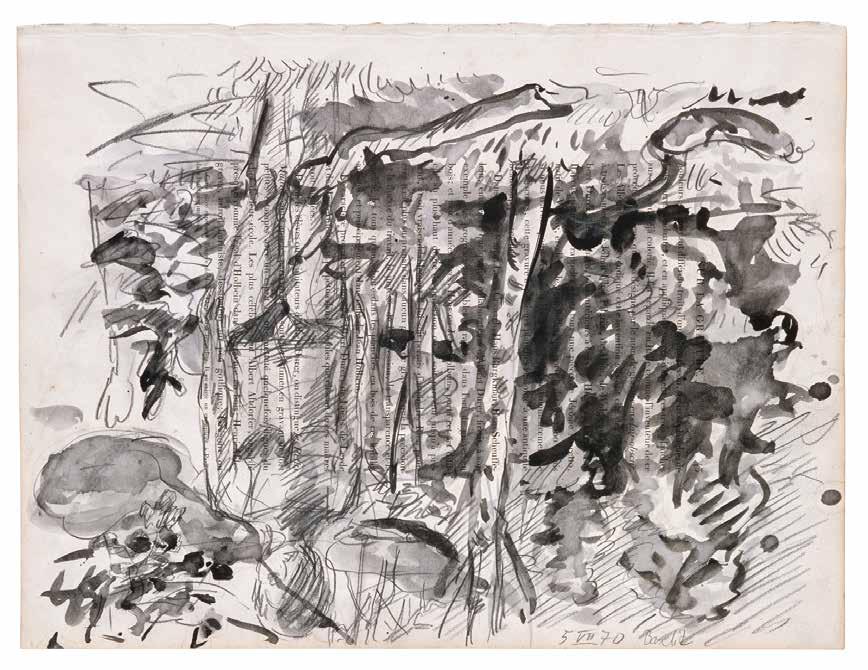

24 o. Halde, 1970

Bleistift auf Papier

57,6 × 43,4 cm

Privatsammlung

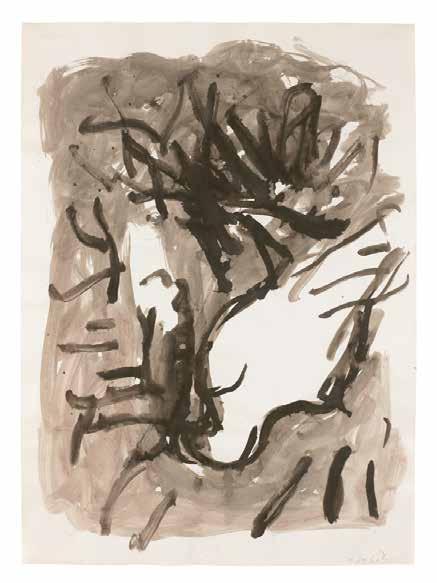

24 u. Büsche, 1969

Bleistift auf Papier

43,5 × 58 cm

Galerie Michael Haas, Berlin

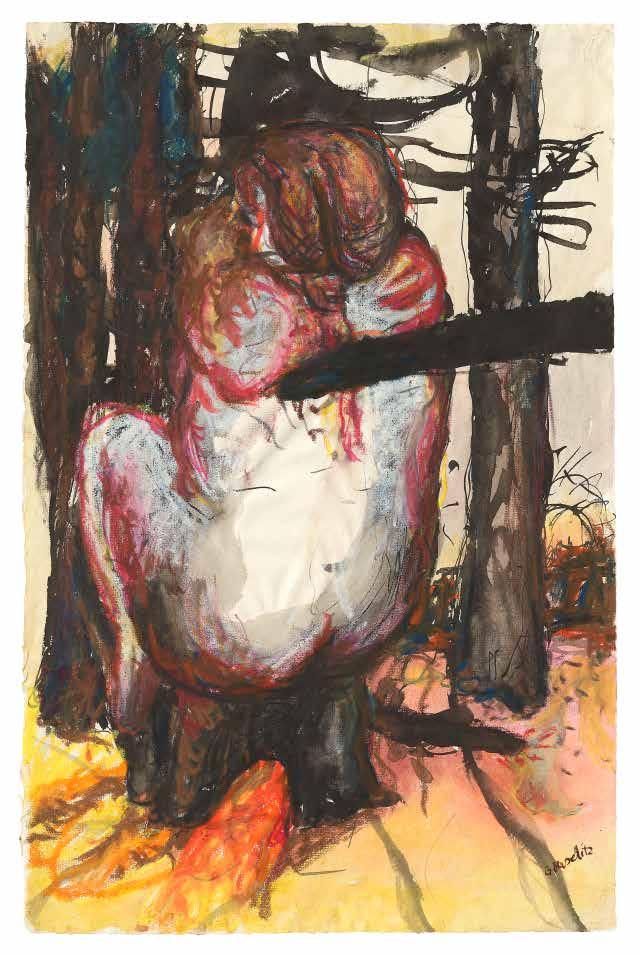

25 Wald mit Elke, 1970

Tusche, Bleistift, Buchseite

58 × 43 cm

Privatsammlung

26 Selbstbildnis mit Lederhose, 1997

Aquarell auf Papier

100 × 75 cm

Privatsammlung

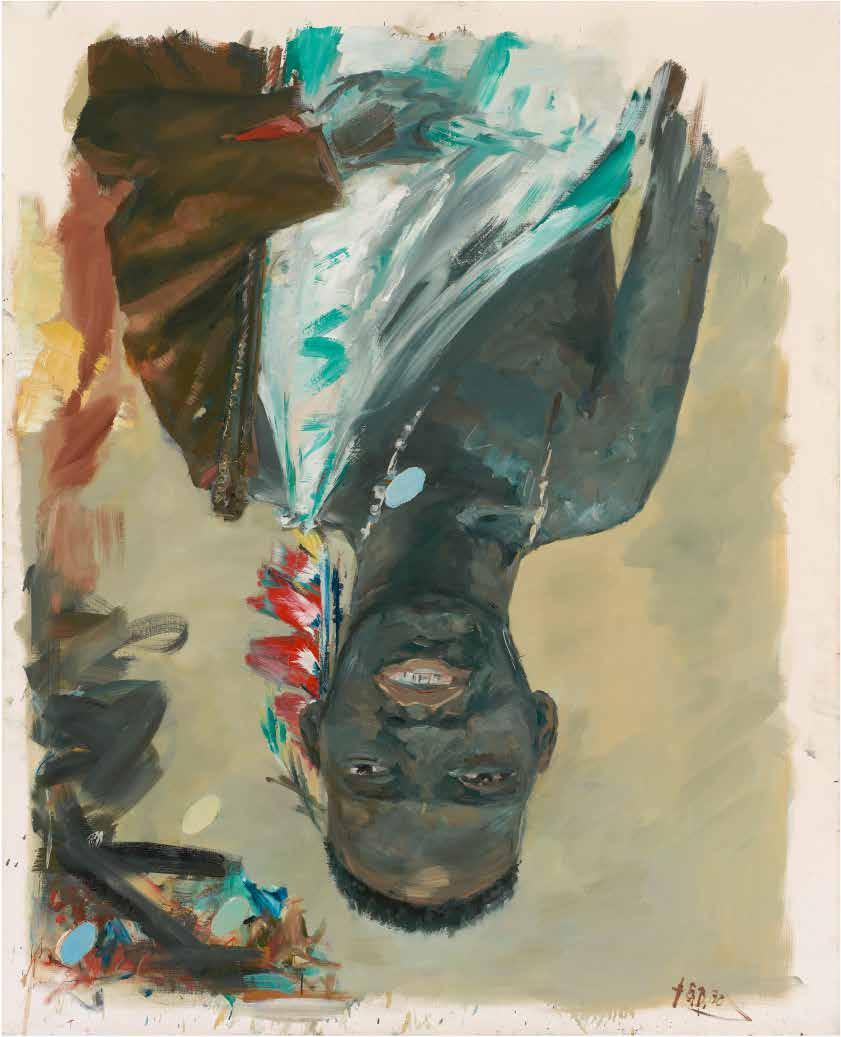

27 3. Afrikaner, 1972 Öl auf Leinwand

200 × 162 cm

Privatsammlung

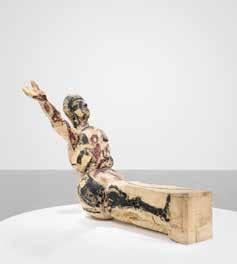

28 Modell für eine Skulptur, 1979–80 Lindenholz und Tempera

178 × 147 × 244 cm

Museum Ludwig, Köln

29 Blauer Kopf, 1983

Rotbuche und Öl

81 × 41 × 34 cm

Kunsthalle Bielefeld

30/31 Abwärts I, 2016

Blauer Kopf, 1983

3. Afrikaner, 1972 aus ’45, 1989

32 Orangenesser (VIII), 1980/81 Öl und Tempera auf Leinwand

200 × 162 cm

Sammlung Uli Knecht, Stuttgart

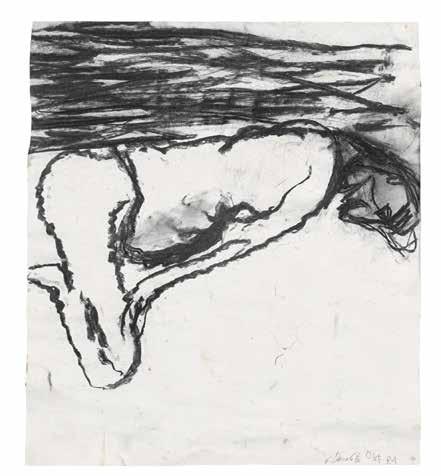

34 Mann am Strand (Okt.’81), 1981

Kohle auf Papier

70 × 62 cm

Privatsammlung

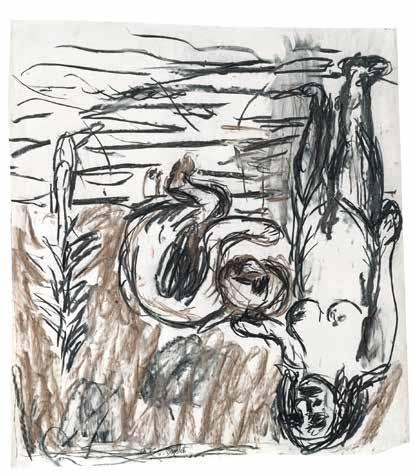

Pastorale, 1985

Kohle, Rötel auf Papier

87,5 × 76,3 cm

Privatsammlung

35 Nachtessen von Dresden, 1983

Kohle, Rötel auf Papier

57 × 87 cm

Privatsammlung

36/37 Orangenesser (VIII), 1980/81 ohne Titel (Hommage à Wrubel), 1963

Rote Mutter mit Kind, 1985

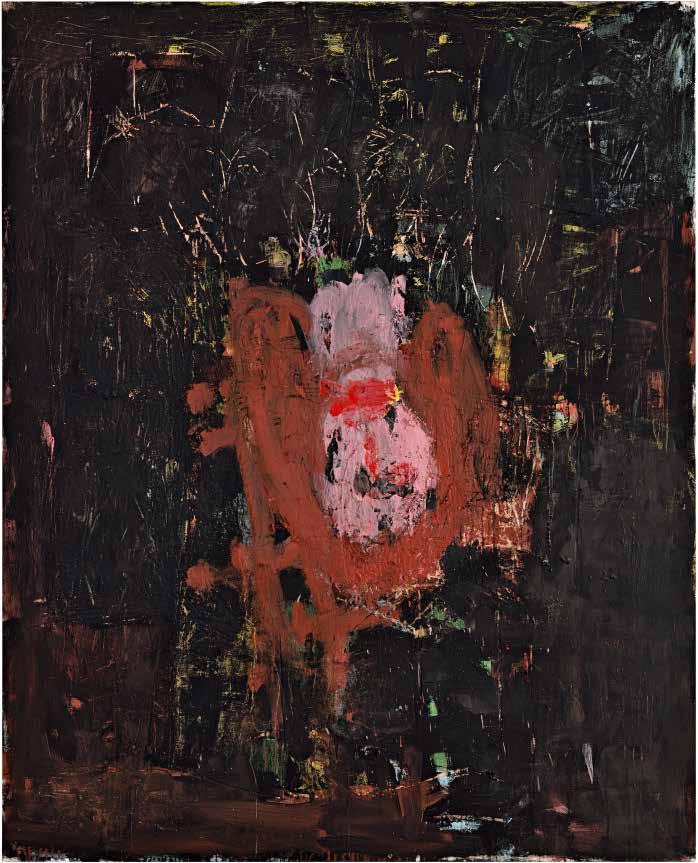

37 Rote Mutter mit Kind, 1985 Öl auf Leinwand

330 × 250 x 5 cm

Galerie Michael Haas, Berlin

38 Nachtessen von Dresden, 1983

Halde, 1970

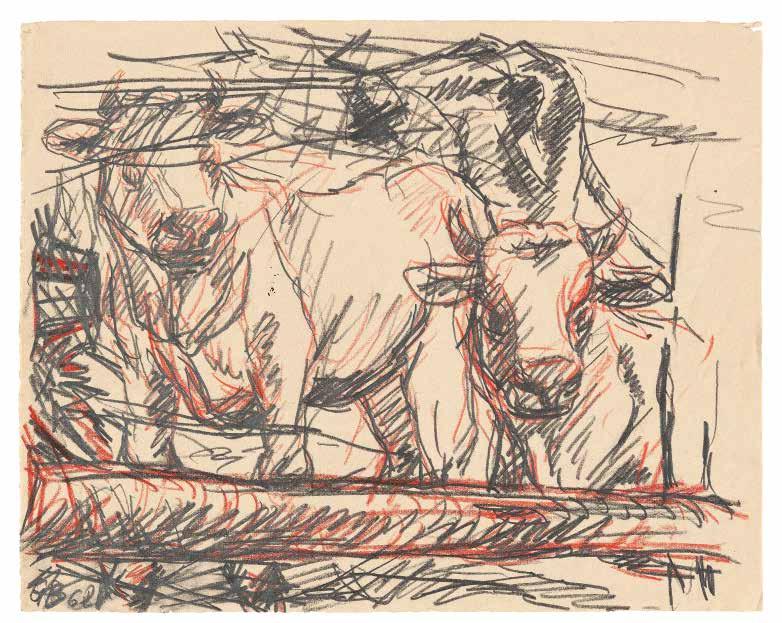

Zwei Kühe, 1968

Adler 12.III.1979, 1979

Büsche, 1969

Wald mit Elke, 1970

39 Adler 12.iii.1979, 1979

Tinte und Aquarell auf Papier

85,7 × 61 cm

schönewald , Düsseldorf

Adler, 1979

Graphit und Tinte auf Papier

85,7 × 61 cm schönewald , Düsseldorf

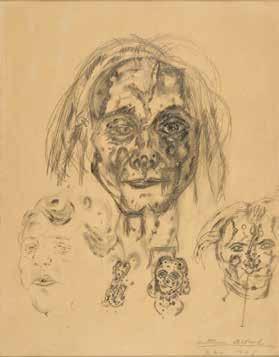

40 Antonin Artaud: Selbstportrait , 11. Mai 1946

Bleistift auf Papier

63 × 49 cm

cnac-mnam , Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle, Paris

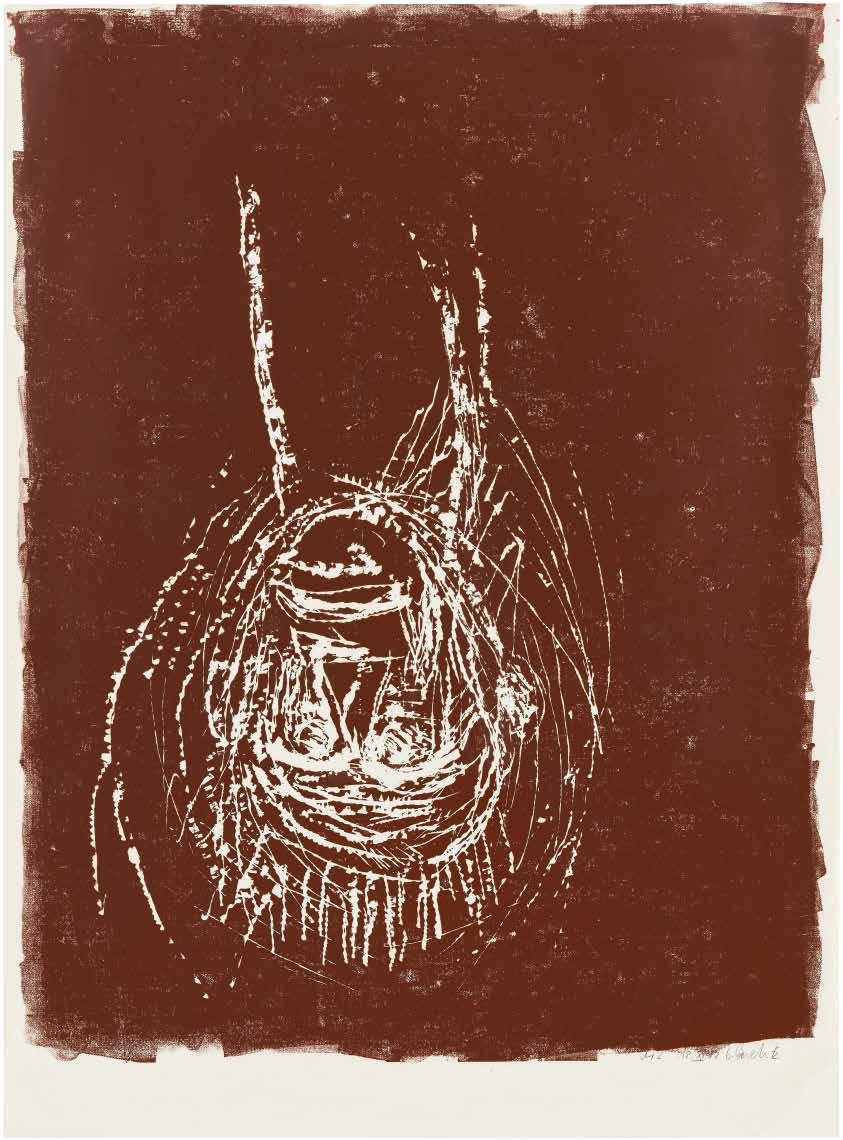

41 Kopf, 1982

Linolschnitt auf Papier

Platte: 190 × 145 cm

Papier: 200 × 160 cm

Dada Held-Poschardt

42 aus ’45 (hier war der Hase drauf, 24. vi – 26. viii 89), 1989 Tempera auf Holz

200 × 160 cm

Privatbesitz

43 Foto: © Daniel Blau, München

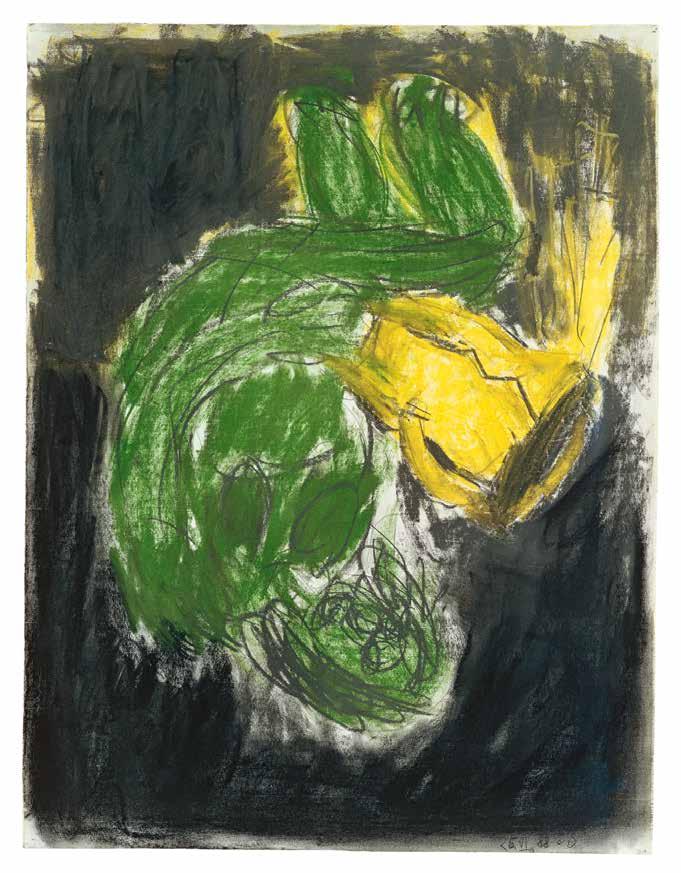

44 Das Motiv Bremen 1988 (Nr. 150), 1988 Pastell, Kohle auf Papier

77 × 59 cm

Privatsammlung

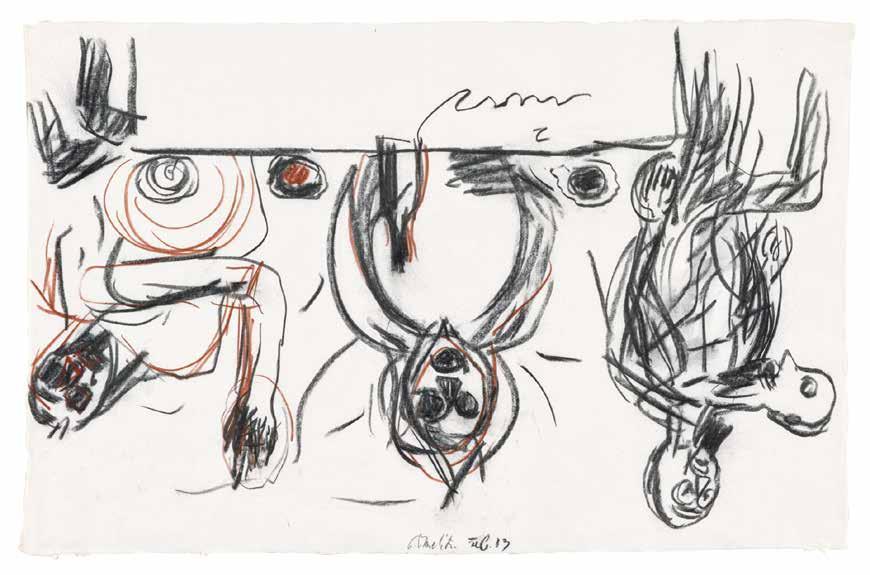

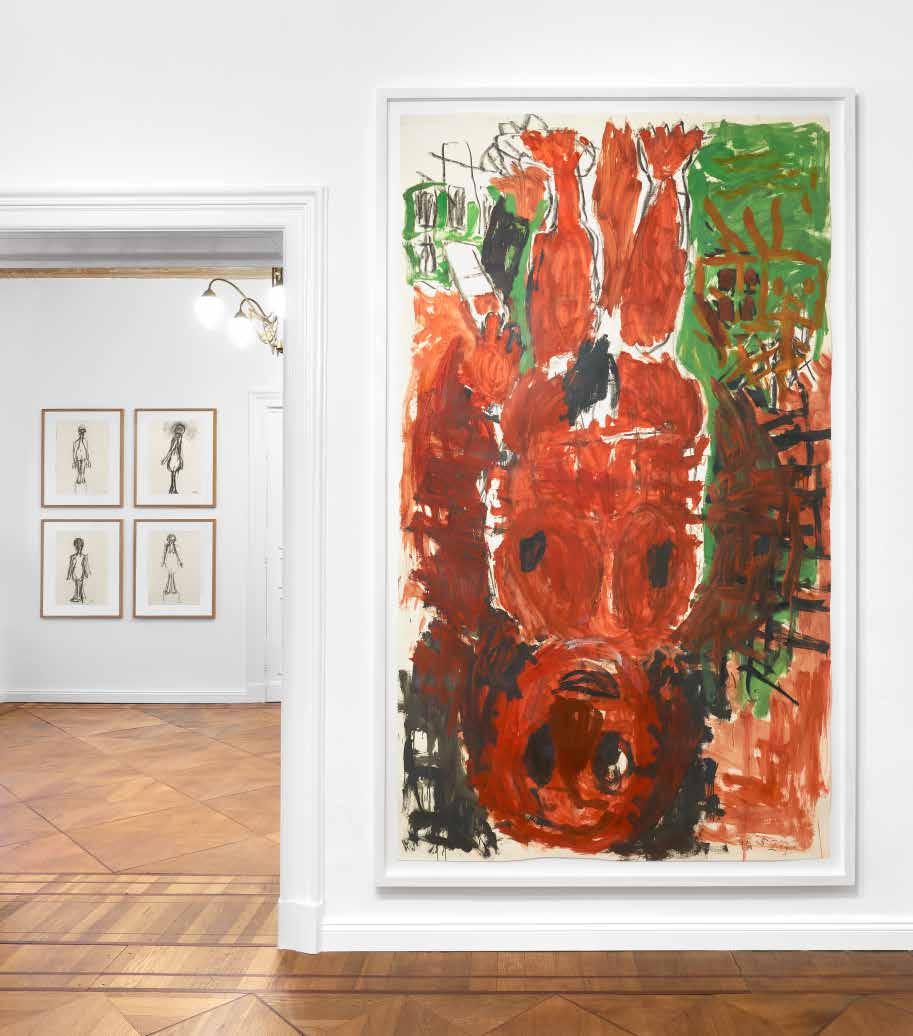

45 4 Zeichnungen: Skulptur

Skulptur (Juni 84), 1984

Skulptur (9. x 83), 1983

Skulptur (1. iii . 84), 1984

Skulptur (1. iii 84), 1984 Kohle / Bleistift auf Papier jeweils 61,4 × 43,1 cm

Kunsthalle Bielefeld

45 ohne Titel (Rote Frau), 1987 Kohle und Öl auf Canson

254 × 147 cm schönewald , Düsseldorf

46 Fotos: Jan Bauer

47 Das erste Negativ, 2004 Öl auf Leinwand

250 × 200 cm

Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

48 Foto: Elfi Semotan

50 Albrecht Dürer:

Liegender weiblicher Akt / Das Meerwunder, 1501

Pinsel, Feder, Weißhöhungen, auf grün grundiertem Papier

16,9 × 21,8 cm

Albertina, Wien

51 Ade Nymphe I, 1998

Öl auf Leinwand

203 × 162 cm

Döpfner Collection

52/53 Ade Nymphe I, 1998

Das erste Negativ, 2004 Katzenkopf, 1967

Waldarbeiter, 1967

Blumenmädchen, 1965 Ein moderner Maler, 1966

55 Modern Painter (Remix), 2007 Öl auf Leinwand

303 × 250 cm

Berlinische Galerie – Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur

Förderung aus Mitteln des Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien ( BKM ) aufgrund eines Beschlusses des Deutschen Bundestages

56 Abwärts I, 2016 Öl auf Leinwand

300 × 185 cm

Döpfner Collection

58–59 ZERO -Aktion, Oktober 2009

Fotos: Archiv CFA, Berlin

61 Abwärts I, 2016

Blauer Kopf, 1983

3. Afrikaner, 1972 aus ’45, 1989

Orangenesser (VIII), 1980/81

61 ohne Titel (Hommage à Wrubel), 1963

Blauer Kopf, 1983

Beatrice, 1964

Pastorale, 1985

Kopf, 1982

Abgarkopf, 1983

Tusche, Aquarell auf Papier

69,5 × 49,5 cm

62 2 Kühe, 1968

Bleistift, Buntstift

31,5 × 39,3 cm

Privatsammlung

64 Elke mit Boxhandschuh ( 31.viii.05), 2005

Aquarell und Tusche auf Papier

67 × 51 cm schönewald , Düsseldorf

nicht abgebildet

4 Zeichnungen: Skulptur

Skulptur (Jan 83), 1983

Skulptur (25. vi 83), 1983

Skulptur (25. Jan 83), 1983

Skulptur (1. iii . 84), 1984

Bleistift, Aquarell / Gouache auf Papier

jeweils 61,4 × 43,1 cm

Kunsthalle Bielefeld

Baselitz’s reaction to choose other outsiders as his allies then, understandable and, from his perspective, The emerging ensemble of poets, artists, and is astounding because of the assuredness of the and the enduring effects of some of these imaginary encounters. Antonin Artaud played and important did Isidor Ducasse, alias Lautréamont. August Strindberg as painter, Charles Meryon, Ernst Josephson, others supported the attitude of the outsider and provided motifs, inspiration, and reasons for retreating. Baselitz also carefully studied the art of the mentally from Hans Prinzhorn’s collection in Heidelberg. He lot, saw a lot, in Paris, for example, and assembled him whatever could feed his work. He did all with his characteristic care and thoroughness. Manifestos

In Georg Baselitz’s studio there is an old, clearly worn leather armchair. A blanket protects it from aging too quickly. This piece of furniture stood in Derneburg, and now it offers a view of Ammersee. There are chairs in studios, of course, it is a seemingly banal observation, but Baselitz’s armchair takes up considerable space and is more like a throne than a piece of useful inventory. The armchair indicates who controls the space, who has something to say, and from where events draw their energy. But there is something about this chair, because it symbolizes the time of reflection between actual acts of painting. Long periods of contemplation, quick painting— this principle regulates the artist’s work rhythm, contrary to the repeated claim of his works’ emotional immediacy. Reflection and painting are mutually dependent and are indissolubly intertwined. There is no “Mal-Schwein” at work who has lost his mind out of sheer expression.

On January 23, 1938, Hans Georg Kern was born in a town far in Germany’s East: Deutschbaselitz! Why the addendum “Deutsch”? Because on the other side of the small forest was a twin village named “Wendischbaselitz.” Sorbs, not Saxons, lived in this village, and they had a special status in the GDR that allowed them to maintain their special folk costumes and customs. When Hans Georg Kern started calling himself Georg Baselitz in 1961, he was referring to this double origin, which would become a permanent point of reference in his orientation and a continuous source of inspiration. The school house in which he grew up, the landscape, traces of prehistoric and Wendish layers that he would later investigate intensively, folk art, and experiences and impressions in Dresden, the old capital and a center of painting since the Romantic era: this is the core around which Baselitz formed numerous new circles that expanded into different spaces and various epochs.

In 1957, after Baselitz was expelled from the academy in East Berlin due to his “political immaturity,” he began studying at the academy in West Berlin under Hann Trier. Trier was a representative of Art Informel in its West German manifestation, developing a method of painting that used both hands, and, through this, strengthening a structural development in the gestural application of paint. Although Baselitz experimented with some of the possibilities of the dominant style, his work was aimed at different results. The Rayski-Köpfe emerged as the first solidification of human motifs from the proliferation of color through gesture. Notably, a Saxon painter of the 19 th century between Romanticism and Realism

provided the decisive impulse: Ferdinand von Rayski, a prominent landscape and portrait painter. The Dresdner Galerie offered the inspiration for Baselitz. Indeed, the choice for his artistic point of departure right in the middle of the Saxon 19th century must have seemed strange and perhaps even arrogant. But Baselitz found himself isolated and lonely in the West. Hann Trier gave the young man from the East reading recommendations. Baselitz’s reaction to choose other outsiders as his allies was, then, understandable and, from his perspective, logical. The emerging ensemble of poets, artists, and writers is astounding because of the assuredness of the choice and the enduring effects of some of these imaginary encounters. Antonin Artaud played and important role, as did Isidor Ducasse, alias Lautréamont. August Strindberg as painter, Charles Meryon, Ernst Josephson, and others supported the attitude of the outsider and provided motifs, inspiration, and reasons for retreating. Baselitz also carefully studied the art of the mentally ill from Hans Prinzhorn’s collection in Heidelberg. He read a lot, saw a lot, in Paris, for example, and assembled around him whatever could feed his work. He did all this with his characteristic care and thoroughness.

Impassioned and without humor — these are the basic characteristics of literary texts in the dress of a manifesto. Its actual history began with the 1847/48 Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Artists of the 20 th century always made demands or distributed provocations in the form of manifestos, especially after the Italian Futurists addressed the public in this way. It was often groups of artists that articulated their goals and interests in manifestos. Baselitz wrote his first manifesto together with Eugen Schönebeck: “I. Pandämonisches Manifest” (1961). This was followed by the “Pandämonisches Manifest II” one year later. The inspiration for this kind of articulation came from artists in Vienna who, at the time, maintained close contacts in Berlin. With drawings and hand-written texts, these manifestations exhibited a very personal, existential style. Antonin Artaud is quoted with his aphorism: “All writing is garbage.”

When Baselitz wrote a manifesto in 1966 for the poster advertising his exhibition at Galerie Rudolf Springer in Berlin, the gesture had changed: “Warum das Bild ‘Die großen Freunde’ ein gutes Bild ist.”

Impassioned and without humor these are the characteristics of literary texts in the dress of a manifesto. Its actual history began with the 1847/48 Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Artists of the 20th century always made demands or distributed provocations in the form manifestos, especially after the Italian Futurists

of the words linguistic possibility who paid increasing

Divisions

There is so frontline between division in

The works equally numerous

The works to 1966 belong Maurice Blanchot “Perhaps the say that in political nor the responsibility and indirect. whether an engage with Baselitz’s primordial Blumenmädchen have just been literally fragmented. carry the invisible Memory was, the war in division of is the fragmentary, on memory, point for an fractures, could be used

Heroes

[Why the painting ‘Die großen Freunde’ is a good painting.] After the experience with the scandalous reception of his first exhibition in 1963, Baselitz lessened the existentialism. He ascribed ironic characteristics to the painting, which Hans Prinzhorn called the features of the “art of the mentally ill.”

Much later, another manifesto-style text followed: “Das Rüstzeug der Maler” [The tools of painters], in 1985. Since then, Baselitz has repeatedly commented on many topics in succinct texts, and has also given his exhibitions ironic-programmatic titles. With their idiosyncratic language rich in associations, the succinctness of the sentences, and the visual heft

In the series in 1965 and a male figure the floor, his might have looking to this figure a hero. Since or physical considered to mobilize especially War, such Germany, usage for a where the Baselitz’s Western or are not self-portraits, between East experienced miracle in strangely injured, but seem alien

words and terms used, Baselitz established a possibility to provoke or instruct the public, increasing attention to him over the years.

of the words and terms used, Baselitz established a linguistic possibility to provoke or instruct the public, who paid increasing attention to him over the years.

Divisions so much literature about Berlin as the between East and West after Germany’s 1961 that it could fill a sizable library. of visual art on the Berlin situation are numerous — they could fill a museum. works by Georg Baselitz from the years 1961 belong to this group, though, in a way, as Blanchot wrote on the books of Uwe Johnson, the hasty reader and the hasty critic could works of this type [those that are neither nor realistic], the relationship to the world and responsibility of a political decision remain distant indirect. Indirect, yes. But one has to ask oneself an indirect path may not be the right one to with the world, and also the shorter one.” Baselitz’s motifs took form out of a kind of painterly ooze, ironically titled, for example in Blumenmädchen . Figures and heads look as though they been born, but still tormented by pain and fragmented. No new beginning that does not invisible burden of memory seems possible. was, after all, divided, ever since the end of 1945, then in 1949, and yet again with the Berlin in 1961. Part of the nature of dividing fragmentary, which places an additional burden memory, and this provided Baselitz with a starting an aesthetic painterly strategy. Mutilations, knots, and injuries: such phenomena used both as content as well as form.

There is so much literature about Berlin as the frontline between East and West after Germany’s division in 1961 that it could fill a sizable library. The works of visual art on the Berlin situation are equally numerous — they could fill a museum.

The works by Georg Baselitz from the years 1961 to 1966 belong to this group, though, in a way, as Maurice Blanchot wrote on the books of Uwe Johnson, “Perhaps the hasty reader and the hasty critic could say that in works of this type [those that are neither political nor realistic], the relationship to the world and the responsibility of a political decision remain distant and indirect. Indirect, yes. But one has to ask oneself whether an indirect path may not be the right one to engage with the world, and also the shorter one.”

inventions were met with very little response at the time of their creation. But with his fictive heroes or “new guys,” Baselitz found formulations for the discomfort that registered with alert artists and writers, despite the glittering consumerist surface of West Germany. During these years, which seemed to be without history, paintings like these visualized what had been suppressed in the German situation between the Third Reich, division, and the future. The modern painter cannot forget anything; in Baselitz’s case, he remains stuck in his connection to his country. The principle of division painfully dominates the final painting of the heroes phase, namely the rift in Die Großen Freunde (1966).

On the black and white poster for the exhibition at Galerie Springer, the isolation between the pair of the two “friends” becomes even clearer. Here, the two figures are already dominated by fracture, which was later introduced as a new way of generating images.

Baselitz’s motifs took form out of a kind of painterly primordial ooze, ironically titled, for example in Blumenmädchen . Figures and heads look as though they have just been born, but still tormented by pain and literally fragmented. No new beginning that does not carry the invisible burden of memory seems possible. Memory was, after all, divided, ever since the end of the war in 1945, then in 1949, and yet again with the division of Berlin in 1961. Part of the nature of dividing is the fragmentary, which places an additional burden on memory, and this provided Baselitz with a starting point for an aesthetic painterly strategy. Mutilations, fractures, knots, and injuries: such phenomena could be used both as content as well as form.

Heroes series of Helden paintings, which Baselitz completed and 1966, is the work Ein moderner Maler, in which figure appears sitting before a black background on his hands trapped in crevices. The torn clothes have once served as a soldier’s uniform. Seized, the sky tormentedly, lost in a no-man’s land, does not correspond to a traditional notion of Since antiquity, people with extraordinary mental physical powers were considered heroes. They were considered role models, but they were also always used mobilize the energy of individuals, people, and states, in times of crisis or war. After the Second World a notion of heroes became untenable in West and even the term “hero” disappeared from long time. This was different in the GDR , new category “hero of labor” was introduced. Baselitz’s figures have nothing to do with either the or Eastern notion of heroes. Even though they self-portraits, the artist reflected on his position East and West, past and present, which he experienced as an outsider. In the middle of the economic West Germany, these paintings, with their injured, helpless creatures, could not help alien and disturbing. Consequently, these

The development of painting into three-dimensional wood figures and heads began in 1977. The large linocuts that Baselitz had produced until that point provided the potential motifs that could be translated into sculpture. Furthermore, the linocut technique involved a treatment of material that could, when taken further, also be used for wood sculpture. Because of his own skepticism about the new direction he was taking with the first wood sculpture for the Biennale pavilion, Baselitz called the work Modell für eine Skulptur. Soon enough, however, he found a suitably powerful method for attacking the wood blocks using an axe, chainsaw, hammer, chisel, and other Rayski, a Dresdner Indeed, the the seemed found Trier gave recommendations. his allies perspective, and of the imaginary important August Josephson, and retreating. mentally Heidelberg. He assembled did all thoroughness. of a 1847/48 Friedrich Futurists groups interests in together Manifest” “Pandämonisches this kind at the drawings exhibited Artaud is garbage.” the Rudolf “Warum ist.” good scandalous Prinzhorn ill.” followed: painters], in commented given the

inventions were met with very little response at the time of their creation. But with his fictive heroes or “new guys,” Baselitz found formulations for the discomfort that registered with alert artists and writers, despite the glittering consumerist surface of West Germany. During these years, which seemed to be without history, paintings like these visualized what had been suppressed in the German situation between the Third Reich, division, and the future. The modern painter cannot forget anything; in Baselitz’s case, he remains stuck in his connection to his country. The principle of division painfully dominates the final painting of the heroes phase, namely the rift in Die Großen Freunde (1966).

On the black and white poster for the exhibition at Galerie Springer, the isolation between the pair of the two “friends” becomes even clearer. Here, the two figures are already dominated by fracture, which was later introduced as a new way of generating images.

The images of the external world fall upside down on the retina of the eye, and only the brain turns them right-side up for our everyday orientation. When Baselitz decided to rotate his motifs 180 degrees, he reasserted what would penetrate our visual organs as a beam of light. This decision came about in 1969, apparently as the result of strong will, however, there were preliminary stages in the development of his oeuvre. Apart from some upside down details in earlier works, the so-called Fraktur-Bilder anticipated the breakthrough with Der Wald auf dem Kopf (1969). Turning the motif on its head was immediately vilified as a mere gimmick. In a most illuminating conversation with Johannes Gachnang in 1975, Baselitz talked about his strategy. For Baselitz, motifs served as an anchor and point of resistance within a relaxed, uninhibited application of paint. This was linked technically with an obstacle termed “finger painting.” With this technique, the painting’s surface could become an independent layer of perception, still requiring a motif, however. This application of paint gave the surface a kind of colorful skin, kept animated by a great restlessness. The viewer senses an impalpable vibration that is charged with energy. In a way unknown until this point, motif and painting were divided into separate elements, though paradoxically, the painter could forge a link between the two, making “new painting” a reality.

In the series of Helden paintings, which Baselitz completed in 1965 and 1966, is the work Ein moderner Maler, in which a male figure appears sitting before a black background on the floor, his hands trapped in crevices. The torn clothes might have once served as a soldier’s uniform. Seized, looking to the sky tormentedly, lost in a no-man’s land, this figure does not correspond to a traditional notion of a hero. Since antiquity, people with extraordinary mental or physical powers were considered heroes. They were considered role models, but they were also always used to mobilize the energy of individuals, people, and states, especially in times of crisis or war. After the Second World War, such a notion of heroes became untenable in West Germany, and even the term “hero” disappeared from usage for a long time. This was different in the GDR , where the new category “hero of labor” was introduced. Baselitz’s figures have nothing to do with either the Western or Eastern notion of heroes. Even though they are not self-portraits, the artist reflected on his position between East and West, past and present, which he experienced as an outsider. In the middle of the economic miracle in West Germany, these paintings, with their strangely injured, helpless creatures, could not help but seem alien and disturbing. Consequently, these

The works of visual art on the Berlin situation equally numerous — they could fill a museum. The works by Georg Baselitz from to 1966 belong to this group, though, in Maurice Blanchot wrote on the books “Perhaps the hasty reader and the hasty say that in works of this type [those that political nor realistic], the relationship the responsibility of a political decision and indirect. Indirect, yes. But one has whether an indirect path may not be the engage with the world, and also the shorter Baselitz’s motifs took form out of a primordial ooze, ironically titled, for example Blumenmädchen . Figures and heads look have just been born, but still tormented literally fragmented. No new beginning carry the invisible burden of memory seems Memory was, after all, divided, ever since the war in 1945, then in 1949, and yet again division of Berlin in 1961. Part of the nature is the fragmentary, which places an additional on memory, and this provided Baselitz point for an aesthetic painterly strategy.

The images of the external world fall upside down on the retina of the eye, and only the brain turns them right-side up for our everyday orientation. When Baselitz decided to rotate his motifs 180 degrees, he reasserted what would penetrate our visual organs as a beam of light. This decision came about in 1969, apparently as the result of strong will, however, there were preliminary stages in the development of his oeuvre. Apart from some upside down details in earlier works, the so-called Fraktur-Bilder anticipated the breakthrough with Der Wald auf dem Kopf (1969). Turning the motif on its head was immediately vilified as a mere gimmick. In a most illuminating conversation with Johannes Gachnang in 1975, Baselitz talked about his strategy. For Baselitz, motifs served as an anchor and point of resistance within a relaxed, uninhibited application of paint. This was linked technically with an obstacle termed “finger painting.” With this technique, the painting’s surface could become an independent layer of perception, still requiring a motif, however. This application of paint gave the surface a kind of colorful skin, kept animated by a great restlessness. The viewer senses an impalpable vibration that is charged with energy. In a way unknown until this point, motif and painting were divided into separate elements, though paradoxically, the painter could forge a link between the two, making “new painting” a reality.

The development of painting into three-dimensional wood figures and heads began in 1977. The large linocuts that Baselitz had produced until that point provided the potential motifs that could be translated into sculpture. Furthermore, the linocut technique involved a treatment of material that could, when taken further, also be used for wood sculpture. Because of his own skepticism about the new direction he was taking with the first wood sculpture for the Biennale pavilion, Baselitz called the work Modell für eine Skulptur. Soon enough, however, he found a suitably powerful method for attacking the wood blocks using an axe, chainsaw, hammer, chisel, and other

to choose other outsiders as his allies then, understandable and, from his perspective, The emerging ensemble of poets, artists, and is astounding because of the assuredness of the and the enduring effects of some of these imaginary encounters. Antonin Artaud played and important did Isidor Ducasse, alias Lautréamont. August Strindberg as painter, Charles Meryon, Ernst Josephson, others supported the attitude of the outsider and provided motifs, inspiration, and reasons for retreating. also carefully studied the art of the mentally Hans Prinzhorn’s collection in Heidelberg. He lot, saw a lot, in Paris, for example, and assembled him whatever could feed his work. He did all with his characteristic care and thoroughness. Manifestos Impassioned and without humor these are the characteristics of literary texts in the dress of a manifesto. Its actual history began with the 1847/48 Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Artists of the 20th century always made demands or distributed provocations in the form manifestos, especially after the Italian Futurists

similarly robust tools. With this approach he was able to create the rough, rugged, cracked shapes that occupy their own place in contemporary sculpture, one that strikes many viewers as highly disconcerting. In discussing the creation of these works, Baselitz has frequently recounted the aggression he invested in them. This seems necessary in order to arrive at an understanding of the origin of the motif. In this respect, hewing figures and heads from the block is related to the excavations of archeologists. Even though these sculptures, apart from a few exceptions, do not display anything individual, they confront the viewer with conditions that the viewer can empathize with and compare to their own experiences.

Nevertheless, a few sculptures in recent years were made as self-portraits. One example is the painted bronze seated figured installed in front of the Hamburger Bahnhof. Here, the roughly hewn blocks form a melancholy figure, like a correction of Rodin’s Thinker, which is so often placed like a logo in front of museum entrances. In conceiving such a sculpture, Baselitz referred to works known from the Romanesque period that are blocky, adorned sparsely with details, but exude an almost magical presence. Baselitz became Rodin, the admirer of Leonardo, a relative of medieval sculpture whose epoch begins after the year 1000.

In the Window

When, in 1979/80, Baselitz produced the twentypart Straßenbild , he expanded the idea of the diptych in his exhibition at the museum in Eindhoven. The inspiration for the Straßenbild was a rather strange, large, 1933 composition by Balthus entitled La Rue. Balthus’s painting depicts a scene on a street in Paris where many things happen at once without any attempt to communicate between them.

From this mysterious coexistence, Baselitz created a polyptych in 1989/90 called 45, which has twenty wooden panels that were roughly treated in the manner of his sculptures. Because the individual pictorial fields give the impression of windows, there is the sense of being in front of openings where there is no greeting, screaming, ranting, or even simple conversation. Sometimes only a head appears, as if it had just been invented – raw, immediate, like a blank slate that could soon expand.

After the reunification of Germany, Baselitz depicted a panorama of women coming home in 45, entering a streetscape from a distant Saxon landscape. Later Baselitz would create the yellow heads of the Dresdner Frauen . None of this is directly linked to the “Orange Eater,” but it is, nonetheless, part of its history. While the motifs in Straßenbild (1980) are located both in the present and past, in the Orangenesser and Trinker series from the beginning of the 1980s, Baselitz reacted to his artistic environment. Not least of all, through his turn to more expressiveness after the cool colors in his work from the late seventies in the exhibition in Eindhoven, a new, aggressive color palette emerged, which was sometimes excessively garish. Eating and drinking, both basic necessities of human life, became his theme in extreme formulations. By enhancing the most banal objects

and actions with such crudeness and anger, Baselitz responded to the emerging work of the “Neue Wilde,” as it was christened by critics alluding to the historical group of the Fauves in Paris around 1906. Baselitz’s painting style in subsequent years did not just cultivate the crude, but also the ugly. This became a leitmotif of the decade following 1980. Baselitz found a way to produce provocative paintings without working with irony, parody, or political provocation, but rather with an elementary kind of painting, demonstrated with elementary processes of life. The motifs of oranges and drinking glasses could be studied at length; the rare citrus fruits of the GDR , the despairing drinking of the bohemians would offer plenty of material. But in their immediacy and crudeness, these motifs also reflect the intellectual and experimental exertion at the beginning of a new period in his work.

The ever-recurring motif. Since the so-called Rayski-Köpfe from the late 1950s, Baselitz has interpreted the human head in a great variety of ways. When a body emerged from the darkness of a 1963 painting’s background, Baselitz placed a grotesque head on top of the bare body, which, in its exaggerated length, is reminiscent of Giacometti. The sallow colors, however, diminish the existential pathos of his predecessor and create a more ambivalent atmosphere. The head and genitals form a pair here, as if they had never been separated from one another. The Helden that were to come soon after usually have small heads, anatomically unlikely for such massive bodies. The woodcut, Großer Kopf (1966), fills the entire surface with an enormous face that is rutted with ornaments. Ralf-Kopf animates a memory of Baselitz’s Dresden friend, A. R . Penck. Baselitz continued returning to head motifs in his sculptural oeuvre over many years, as in his Blauer Kopf (1982/83). The title is, actually, only appropriate for the upper half of the sculpture, being that the head, with its round eyes looking upwards, sits on a massive wooden block that becomes something like a source of energy for the visionary and powerful physiognomy of the head. Something rises from the unshaped, rough wooden body into the head, feeding it and simultaneously giving it strength to part from the lower half, a process aided by the blue paint. Around the same time, Baselitz cut the Artaud head in a large linoleum panel. Once again, he chose an unusually long neck to serve as a “pedestal” for the head, surrounded by radiating circles. For this motif, Baselitz imaginatively adapted a self-portrait drawing by Antonin Artaud. Like in 1963 and in the later sculpture, the head in the linocut is fascinating for its visionary suggestion and simultaneous impression that the head is the locus of human will, which, through the concentric rays, has an effect on the space. Here, as well as in other works by Baselitz, the expressive appears as the equivalent of the will as such.

The name Baselitz is programmatic; it stands for the inspiration from the lost world of Eastern Germany, which suddenly seemed to be nearing again with the

political changes moving historical work on wooden and treated due to the manner, and shows a rabbit. in a wall-sized rows. Only reflection associated granted status World War harsh reality Georg Kern historical changes war to a completely adding the and exposure, life at that simplistic at broad spectrum Baselitz’s treatment something after a catastrophe. mother/child used ugliness when looking pictorial realization allegorization, confrontation work 45 Bild have exhausted yellow wooden If the saying then Baselitz with his unusual the blunt surfaces through tempera which appeared

Inventions

The paradigm visual arts become the declared dead, “art into life” the marriage media celebrated is helpful to and renewal. graphic arts, that he had time and history within a given but never abandoned. Baselitz demonstrated the painting pictorial antagonism. established

changes of 1989. Under the impression of this historical moment, Baselitz began a multi-part wooden panels. These panels were stained black treated in the style of the large linocuts, though, material’s brittleness, in a particularly rough and were to display women’s heads. One panel rabbit. The work culminates in twenty pictures wall-sized composition, arranged in two vertical Only the succinct title 45 alludes to the historical associated with this ensemble. Bild Nr. 21 was status as an individual work. When the Second War ended in 1945, women were faced with a reality in a devastated country. At that time, Hans Kern was seven years old and he experienced the changes as a transition from dictatorship and completely unstable and disoriented present. By rabbit to the cycle, the symbol for erraticness exposure, Baselitz alluded to how he experienced time. Although the women’s heads seem at first glance, upon longer examination a spectrum of human emotions becomes visible. Baselitz’s use of the dark background and his rough of the wooden panels enabled him to develop out of nothing, the reemergence of humans catastrophe. As in some works from the 1980s, the mother/child motifs, for example, Baselitz consciously ugliness as a stylistic device to avoid any detachment looking at history. Baselitz achieved an appropriate realization not through historic argument or allegorization, but rather through direct, unvarnished confrontation with the memory of 1945. In titling the Bild Nr. 21, Baselitz hinted that he might not exhausted this topic yet, demonstrated by the wooden sculptures, Dresdner Frauen , from 1990. saying goes that one can dig into memory, Baselitz found the appropriate means of doing so unusual techniques. It additionally required surfaces of the panels, which were possible tempera painting, and gouging into wood, appeared like digging in dark, earthly painting.

political changes of 1989. Under the impression of this moving historical moment, Baselitz began a multi-part work on wooden panels. These panels were stained black and treated in the style of the large linocuts, though, due to the material’s brittleness, in a particularly rough manner, and were to display women’s heads. One panel shows a rabbit. The work culminates in twenty pictures in a wall-sized composition, arranged in two vertical rows. Only the succinct title 45 alludes to the historical reflection associated with this ensemble. Bild Nr. 21 was granted status as an individual work. When the Second World War ended in 1945, women were faced with a harsh reality in a devastated country. At that time, Hans Georg Kern was seven years old and he experienced the historical changes as a transition from dictatorship and war to a completely unstable and disoriented present. By adding the rabbit to the cycle, the symbol for erraticness and exposure, Baselitz alluded to how he experienced life at that time. Although the women’s heads seem simplistic at first glance, upon longer examination a broad spectrum of human emotions becomes visible.

distanced three-dimensional works from the object and pushed them toward sculptural form in the sense of those created before the Renaissance and outside Europe, for example, those created in Africa. He transformed the polyptych, originally conceived for sacred uses, into a modern form. He turned art about art into a design principle — but not as a reference, but a creative answer. He made memory a category unexpectedly fruitful for art. And he renewed the artist’s collection: Mannerists, Africa, Fautrier, Picasso, Giacometti, Francis Picabia etc. He reinterpreted the remix principle of popular music for painting. He took folk art seriously.

distanced three-dimensional works from the object and pushed them toward sculptural form in the sense of those created before the Renaissance and outside Europe, for example, those created in Africa. He transformed the polyptych, originally conceived for sacred uses, into a modern form. He turned art about art into a design principle — but not as a reference, but a creative answer. He made memory a category unexpectedly fruitful for art. And he renewed the artist’s collection: Mannerists, Africa, Fautrier, Picasso, Giacometti, Francis Picabia etc. He reinterpreted the remix principle of popular music for painting. He took folk art seriously.

Above all, however, he encouraged a new relationship between intellect and creatureliness of humans.

Above all, however, he encouraged a new relationship between intellect and creatureliness of humans.

Baselitz’s use of the dark background and his rough treatment of the wooden panels enabled him to develop something out of nothing, the reemergence of humans after a catastrophe. As in some works from the 1980s, the mother/child motifs, for example, Baselitz consciously used ugliness as a stylistic device to avoid any detachment when looking at history. Baselitz achieved an appropriate pictorial realization not through historic argument or allegorization, but rather through direct, unvarnished confrontation with the memory of 1945. In titling the work 45 Bild Nr. 21, Baselitz hinted that he might not have exhausted this topic yet, demonstrated by the yellow wooden sculptures, Dresdner Frauen , from 1990.

If the saying goes that one can dig into memory, then Baselitz found the appropriate means of doing so with his unusual techniques. It additionally required the blunt surfaces of the panels, which were possible through tempera painting, and gouging into wood, which appeared like digging in dark, earthly painting.

paradigm shift that the 20 t h century brought to the was a shift from mimesis to progress. Novelty the criterion for quality and fame. Painting was dead, the departure from the picture initiated, life” proclaimed, open artworks demanded, marriage of high and low consummated, and new celebrated as a great promise. In Baselitz’s case, it to distinguish between the search for the new renewal. To further develop painting, sculpture, arts, and drawing, shifts were required of Baselitz had to take step by step in order to react to history in his work. His inventions took place given frame, which he stretched and damaged, abandoned. In his reorientation of motifs, demonstrated a departure from a painting within painting itself. In doing so, he provoked an inner antagonism. With the large linocuts, Baselitz established a new category of graphic art. His sculptures

Rayski-Köpfe human emerged background, bare reminiscent of diminish the more form from after for such (1966), fills the rutted with Baselitz’s returning many years, actually, only being upwards, sits something powerful the feeding it from the Around large unusually long surrounded by imaginatively Artaud. Like the linocut simultaneous will, on the Baselitz, the as such. the Germany, the

When Baselitz renewed Ein moderner Maler from 1966 in this way, he added to the lower half of the painting a representation of small forest. It references Ferdinand Baselitz Wilde,” historical Baselitz’s cultivate leitmotif of the produce irony, parody, elementary processes glasses could GDR , offer crudeness, experimental work.

Already for his large 1995 retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York, Baselitz began returning to earlier motifs. These paintings, pasty, often offset with white, began to claim their place in the artist’s oeuvre late in 1990. These were not precise returns to earlier works, but rather motifs of heroes, heads, or nudes that he developed from earlier inventions. Baselitz, when he originally developed these motifs, forged a path into his own pictorial world, just as Fernand Léger and, from a certain point onwards, also Picasso, had done. Léger, in his cycles Le Grande Parade , Partie de Campagne and Les Constructeurs, summarizes his pictorial world and reassembles it in new combinations. One could also speak of Picasso’s treatment and variation of earlier motifs, like Le peintre et son model , or the “sleep watchers” as Leo Steinberg called this iconographic group. The supply of motifs and methods of composition was large and rich enough to create new works from it. In the broadest sense, this touches on the problem of the aging artist, or the possibility of summing things up in a “late work.” Gottfried Benn’s Aging as a Problem for Artists identifies a series of phenomena in late works: greater freedom, a tendency to experiment, tiredness, melancholia, mildness, etc. But Benn remains skeptical, since examples and counter-examples seem to balance each other out. His reference to a book by the art historian Albert Erich Brinckmann, Spätwerke großer Meister, leads closer to Baselitz. Brinckmann assembles a list of examples demonstrating that, since the Renaissance, artists painted early works again in their old age, which lead to quite remarkable results. That is without a doubt true for Baselitz’s remix period, which began in late 2005. The decision to repaint works like Die große Nacht im Eimer (1962/63) is reminiscent of earlier decisions to turn motifs on their head, to hew wood sculptures from a block or stem, or to paint the series of large landscape formats during the 1990s.

The paradigm shift that the 20 t h century brought to the visual arts was a shift from mimesis to progress. Novelty become the criterion for quality and fame. Painting was declared dead, the departure from the picture initiated, “art into life” proclaimed, open artworks demanded, the marriage of high and low consummated, and new media celebrated as a great promise. In Baselitz’s case, it is helpful to distinguish between the search for the new and renewal. To further develop painting, sculpture, graphic arts, and drawing, shifts were required of Baselitz that he had to take step by step in order to react to time and history in his work. His inventions took place within a given frame, which he stretched and damaged, but never abandoned. In his reorientation of motifs, Baselitz demonstrated a departure from a painting within the painting itself. In doing so, he provoked an inner pictorial antagonism. With the large linocuts, Baselitz established a new category of graphic art. His sculptures