TEACHER’S MANUAL WRITTEN BY

KRISH DHANAM

AND ANDREW E MATTHEWS

Published 2024 by CEP

Copyright © Andrew E Matthews 2024

This resource is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without permission of the publisher.

Scripture taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version® NIV®.

Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. All rights reserved worldwide. Used by permission.

Christian Education Publications

Australia

PO Box A287, Sydney South NSW 1235

P +61 2 8268 3344

E sales@cepstore.com.au

W cepstore.com.au

New Zealand

P +64 27 613 4141

E sales@cepstore.co.nz

W cepstore.co.nz

Written by: Krish Dhanam and Andrew E Matthews

Design: Rachel Aitken

All images from the film used with kind permission of The Skypass Group. Other images: Shutterstock.

CONTENTS Introduction 1 Overview 3 Sensitivity triggers 4 Context and cultural aspects to address 4 before students watch the film Five circles of learning 7 How to teach this unit 10 Lesson 1—What is truth? (Part 1) 12 Context 13 Core concepts and questions 13 Student handbook 14 Extension activity #1 22 Extension activity #2 24 Lesson 2—What is truth? (Part 2) 25 Core concepts and questions 26 Student handbook 26 Extension activity #1 32 Lesson 3—What is a human being? 34 Core concepts and questions 35 Student handbook 35 Extension activity #1 45 Lesson 4—The problem of Christianity 46 Core concepts and questions 47 Student handbook 47

INTRODUCTION

WELCOME

Welcome to The Least of These: The Graham Staines Story Teacher’s manual.

This Teacher’s manual is designed to accompany The Least of These: The Graham Staines Story Student handbook, a digital resource that can be used on a device (such as a laptop or iPad) or printed out, lesson by lesson. There are also videoclips for each lesson that are designed to be shown, section by section, as the lesson is taught. The film itself can be rented or bought from YouTube, AppleTV and Google Play.

The resource is intended for students in years 9–11.

This unit forms part of a range of secondary resources developed for Christian studies or religious education in independent schools. The material could easily be used in other contexts, such as youth groups or camps. Go to www.CEPStore.com.au for more information.

UNIT AIM

This unit aims to help students engage with a few ‘big’ life questions emerging from the film The Least of These: The Graham Staines Story and reflect on how their personal beliefs align with some of what the Bible teaches.

LEARNING INTENTIONS

The main themes covered in the unit are:

• truth, its nature, how we discern it, how our truths precede our actions, and how this is manifest in religious belief

• God and how we understand and conceive of God in relation to the nature of truth, and how the Bible conceives of God

• human origins and the consequential purpose for ‘being’

• Christianity, notwithstanding some of its failures, as a possible unifying expression of truth, God and the purpose of human existence.

By the end of the unit, the students will know about:

• the real events surrounding the murders of Graham, Philip and Timothy Staines

• the underlying motivating beliefs of some of the characters/

real people in the story

• the Bible’s teachings about some of life’s big questions.

By the end of the unit, students will be able to:

• articulate some of their beliefs about some world view issues such as truth, origins, the meaning of being human, what is wrong with the world, and Christianity

• articulate some of the Bible’s teaching on these world view issues

• understand some of the underlying beliefs motivating both missionary endeavours and those opposed to them.

By the end of the unit, students will have the opportunity to:

• compare their own beliefs about some world view issues with the Bible’s teachings

• discuss with peers and their teacher possible answers to some world view issues

• challenge and develop their own beliefs

• consider some implications of their belief for their own lives.

STAGE LEVEL

This unit is designed for students in Stages 5 and 6. Some of the concepts covered are confronting and so would not be suitable for younger students. It is advised to pre-watch the film for suitability for your cohort.

TIPS FOR TEACHING

THE LEAST OF THESE

• Do not provide ‘answers’: this unit is exploratory in nature and allows students to come to their own conclusions about the issues raised. They may not be able to provide answers to some of the broad questions—that’s OK.

• Discussion is valuable: create a safe space in which students as a class or in small groups feel comfortable to explore and share possible viewpoints.

• Allow incongruity and illogical responses: part of the exploratory process requires us to sit comfortably with inconsistences in our thinking. Our views may be deep-seated or emotional, and we may not yet be able to articulate why we think a certain way.

• When students compare a personal view to the Bible’s teaching, do not require them to accept the Bible’s teaching. Observe differences and allow these differences to exist.

• Remember that there may be Hindu, Sikh and Muslim students partaking in the course and be careful when discussing difficult topics such as community ostracism due to leprosy.

+ +

3

Teacher’s manual Student handbook Movie

SENSITIVITY TRIGGERS TO WATCH OUT FOR

• Different religious viewpoints: the film and studies purposefully avoid blaming any religious or political groups. Not only would this be stereotyping, but it is also impossible to attribute all of an individual’s views and motivations to the groups that individual supports.

• The film depicts actual murders that took place in 1999, including the murder of two young children. This has been depicted as sensitively as possible, minimising screentime and the violence that occurred. Nevertheless, the incident was shocking and may trigger feelings of grief or trauma in some students.

• Actual leprosy sufferers are shown in the film. The depictions are not graphic, but students may not have been exposed before to some of the deformities caused by the disease.

CONTEXT AND CULTURAL ASPECTS TO ADDRESS BEFORE STUDENTS WATCH THE FILM

MISSIONARIES IN INDIA

Christian missionaries have played a significant role in India, particularly in the fields of education, healthcare and social services. While their activities have been diverse, some missionaries have specifically focused on providing medical care and support to those affected by diseases such as leprosy.

William Carey (1761–1834), often called the ‘father of modern Christian missions’, was a British Christian missionary and linguist who made significant contributions to the fields of education, literature and science in India. Arriving in the country in 1793, Carey dedicated his life to improving the socio-economic conditions of its people. He is widely regarded for his efforts in promoting education, including founding schools and colleges, and translating the Bible into numerous Indian languages. Carey’s linguistic prowess led him to compile dictionaries and grammars for several languages, fostering a deeper understanding between Indian and Western cultures. Additionally, he played a key role in agricultural and industrial development, introducing new techniques and technologies. (For more information on Carey, read Vishal and Ruth Mangalwadi’s book The Legacy of William Carey.) Graham Staines operated in the same mould as Carey, although within a smaller sphere of influence. In the context of leprosy, missionaries like Staines have often been at the forefront of

efforts to care for individuals affected by the disease. They have established hospitals, clinics and rehabilitation centres, providing not only medical treatment but also addressing the social and economic challenges faced by leprosy patients. Many missionaries have worked to destigmatise leprosy and improve the living conditions of those affected.

While the impact of missionaries in India is multifaceted and has received both praise and criticism over the years, their contributions in healthcare, education and social services have been notable, and they have often worked in collaboration with local communities to address various challenges.

LEPROSY

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is a chronic infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae 1 It primarily affects the skin, peripheral nerves, mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract, and the eyes. Leprosy has been present throughout human history and has often been surrounded by stigma and fear. The disease is characterised by skin lesions and nerve damage, and, if left untreated, can lead to severe deformities.

Leprosy is primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets, but its exact mode of transmission is not fully understood. Although effective multidrug therapy exists for leprosy, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent complications and reduce transmission. Community efforts to eliminate leprosy continue, with a focus on raising awareness, reducing stigma and ensuring accessible healthcare for affected individuals. Most leprosy cases (95%) occur in 23 countries in the developing world. About 200,000 new cases are reported every year. Australia has very few cases: about 10 to 20 per year, some of which occur in migrants from the developing world.

Before the discovery of effective treatments for leprosy, historical approaches to managing the disease varied widely. Many societies, influenced by the fear and stigma surrounding leprosy, isolated individuals with the condition, creating colonies where those affected lived apart from the general population. These colonies, often governed by religious or charitable institutions, aimed to provide care and support for people with leprosy.

In medieval Europe and India, for example, the prevailing belief was that leprosy was a punishment from a higher power or due to sins in a past life, and patients were subsequently subjected to harsh rejection or ineffective ‘treatments’. It wasn’t until the 1980s that effective antimicrobial treatments, such as dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine, were developed. The introduction of multidrug therapy revolutionised leprosy treatment, leading to a significant reduction in the prevalence of the disease globally. Graham Staines worked for many years among leprosy sufferers, placing himself at risk before there was an effective cure.

1. Information about leprosy drawn from The Leprosy Mission, viewed February 2024 (leprosymission.org).

4

THE NATURE OF THE INDIAN LAW THAT FORBADE PROSELYTISING

Anti-conversion laws, often known as ‘freedom of religion’ laws, are still enacted at the state level in India, and aim to regulate religious conversions, particularly those perceived as involving force, fraud or inducement. At the time of Graham Staines’ murder, Orissa, the state where he worked (now known as Odisha), had this type of law in place.

Proponents of these laws argue that they are necessary to prevent forced or fraudulent religious conversions, often citing concerns about vulnerable individuals being coerced into changing their faith. Critics, however, view these laws as potential tools for harassment and discrimination, especially against religious minorities. They argue that such laws may infringe upon the fundamental right to freedom of religion as guaranteed by the Indian constitution.

There has been fear that such laws may be used to prevent individuals from freely converting to a religion other than the dominant religion within a region. For example, in the state of Uttar Pradesh in early 2023, an report was filed against a Christian couple who were accused of ‘allurement’ in their attempts to evangelise low-caste people.2 A judge in the Allahabad High Court, however, ruled that distributing Bibles and encouraging and offering educational services were not in contravention of the law.

THE CASTE SYSTEM

The caste system in India is a social hierarchy that has been a prominent feature of traditional Indian society for centuries.3 It is a complex social structure that categorises people into different groups based on their birth, occupation and social status. The caste system is rooted in ancient Hindu scriptures and has historically influenced various aspects of life, including social interactions, marriage and occupation.

The caste system traditionally comprises four main categories or varnas:

• Brahmins: traditionally priests and scholars, responsible for religious rituals and teaching

• Kshatriyas: the warrior and ruler class, responsible for protection and governance

• Vaishyas: the merchant and farming class, responsible for economic activities and trade

• Shudras: the labourer class, providing services and manual labour.

2. ‘Distributing the Bible, encouraging education not “allurement” for conversion: Allahabad HC’, The Wire, September 8 2023, viewed February 2024 (thewire.in/law/distributing-bibles-encouragingchildrens-education-not-allurement).

3. Information about the caste system drawn from Kelete, S 2015, ‘The caste system (Brahmin and Kshatriya)’, Religion 100Q: Hinduism Project, November 25 2015, viewed February 2024 (scholarblogs.emory.edu/rel100hinduism/2015/11/25/the-castesystem-brahmin-and-kshatriya/).

Outside of these varnas, there exists a group known as the ‘Dalits’, or ‘scheduled castes’, who historically were marginalised and often subjected to social discrimination. The term ‘Dalit’ means ‘oppressed’ or ‘broken’, and is used by some groups to self-identify.

Christian missions, inspired by principles of social justice and humanitarianism, have often engaged in activities aimed at improving the living conditions, education and socio-economic status of Dalit communities. Dalit communities often have little or no access to health care. However, it’s important to note that the involvement of Christian missions in Dalit communities has been a subject of controversy and debate. Critics argue that such activities could be seen as a form of inducement for religious conversion, while proponents emphasise the humanitarian aspects and the commitment to social justice. India has experienced discussions and occasional tensions related to allegations of forced conversions or improper inducements, leading to concerns about religious freedom and the role of missionaries.

5

HOW TO TEACH THIS UNIT

The suggested progression of the unit is to start by providing some contextual information before having some initial discussion to help assist and motivate student thinking on the various topics raised.

As the lessons draw from elements across The Least of These: The Graham Staines Story, it is ideal to dedicate two lessons to watching the film before engaging with the student material. Its running time is 108 minutes and it’s available to rent or buy through YouTube, Apple TV and Google Play.

In addition to the film, there are four video-guided lessons, each estimated to take between 60 and 90 minutes depending on the level of engagement and length of discussion facilitated.

There are four videos, one per lesson, plus a final, optional one where Krish reads the prayer reproduced on page 26 of the student handbook. The videos can be accessed throughout this manual as direct links wherever the video icon is displayed. They are also hosted on www.CEPTeacherslounge.com. They require the password given to the purchaser of this manual in order to access them.

Some of the dialogue in the film can be hard to understand, so you might like to turn on the closed captions to assist your students.

Within the videos, the following clips from the film are repeated very briefly:

• Episode 1

o Lead-up to the murders

o The editor’s response, and his instruction to print the ‘truth’

• Episode 2

o Gladys’ reaction to news of the murders

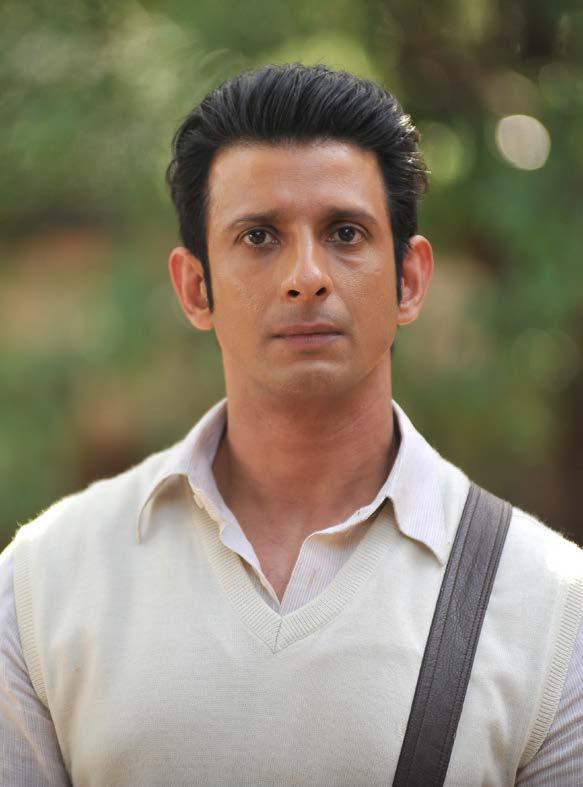

o The main character, Manav, and his initial conversation about missionaries with the editor

o Manav’s further conversations with the editor about printing the truth

o Manav’s reaction to Sundar, the cured leprosy patient

• Episode 3

o Gladys’ reaction to news of the murders

o Gladys’ grief and Manav’s realisation

o The beggar with leprosy whom Graham helps

o Manav’s conversation with Graham about why he does what he does

o Graham tending to leprosy patients

o Short montage of images from the preceding scenes

o Montage of references to leprosy that Manav experienced

• Episode 4

o Manav’s challenge to the editor to meet with his father

o Four excerpts referencing the anti-conversion laws

o Manav pressuring Sundar into admitting that he converted

CORE CONCEPTS AND QUESTIONS

Episode 1

• In relation to the murders:

o What is the view (that is, the ‘truth’ for that person) that saw the killing of Graham Staines as acceptable, perhaps even beneficial?

o What is the view (or truth) that saw the killing of the boys, Philip and Timothy, as acceptable?

o What are the possible views that consider these killings to be unacceptable?

• In relation to God:

o What is God?

o How would you describe God?

o What does the Bible say about God?

• Core concepts:

o Different ‘truths’ result in different interpretations

o All people have a moral principle

o Something acts as ‘God’ for everyone.

Episode 2

• In relation to truth:

o Is it reasonable?

o Does it match reality?

o Does it explain all of life?

o Is it liveable?

o Can spiritual truth be discerned rationally?

• In relation to God:

o What truths does the Bible claim about God?

o How can a ‘person’ be truth?

o What might this suggest for our normal categories of right and wrong (that is, truth)?

• Core concepts:

o Beliefs may not correspond to evidence

o Presuppositions influence conclusions.

Episode 3

• In relation to being human:

o Why forgive?

o How did the world begin?

o Why do human beings exist?

10

o What are the consequences of these ideas or stories?

o What is implied about humans in the Bible’s origin story?

o What do you think is ‘wrong’ with the world?

o What theories or ideas have you heard that attempt to answer that question?

• Core concepts:

o Our view of human beings influences our actions and choices.

o The Bible indicates every human being’s value.

o All religions and philosophies have to address ‘what is wrong’ with the world.

o The Bible tells us that we are what’s wrong with the world.

Episode 4

• In relation to Christianity:

o Name some of the ‘problems’ of Christianity.

o Consider whether these problems are personal problems for you or problems you’ve seen others have.

o In what ways are religious conversions a problem?

o Do you think of conversion as a freedom, as a human right, or as coercion and therefore forced in some way?

o Do human beings need to be forgiven or ‘saved’?

o If so, what can we do to be forgiven or saved?

o Can our good deeds outweigh our not-so-good deeds, thoughts and attitudes?

• Core concepts:

o Humility could be the main problem of Christianity for human beings.

o Jesus Christ’s resurrection is proof that what he said and taught is true.

These presentations are designed to allow you, the teacher, the opportunity to facilitate discussions, encourage students to think more deeply, and, should you wish, provide a springboard for further exploration and learning. While the video episodes and response booklets do most of the work, you will need to pause the videos at the appropriate times and may need to encourage students to engage with some of the difficult and deep questions being asked.

With tightly managed discussions, it is estimated that each study can be covered in about 45–60 minutes. Of course, if students engage with the materials well, more lengthy discussions may be appropriate.

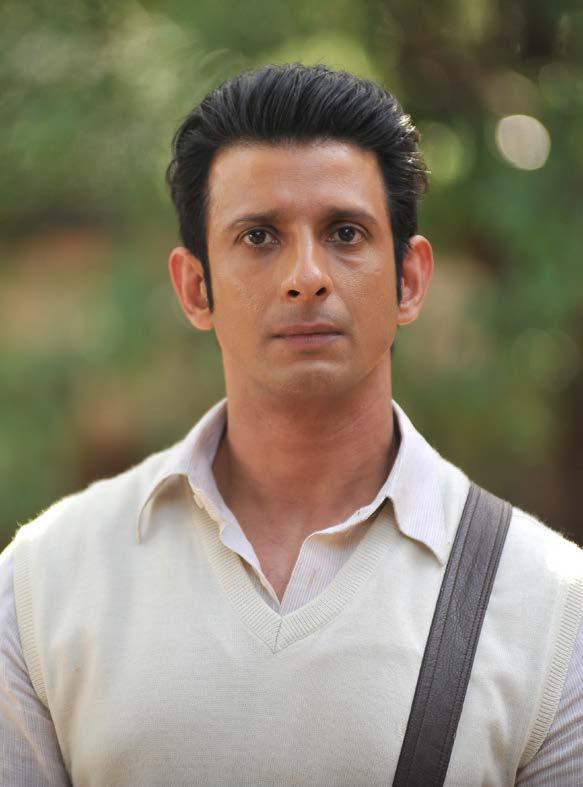

Each of the four 13–18 minute episodes:

• starts with extracts from the film

• includes ‘big’ questions that arise from these extracts

• features presenter Krish Dhanam, who provides context and comment while leading the viewer through the

questions, with additional comment from one of the writers, Andrew E Matthews

• includes pause points to allow students to engage with the questions, considering their own beliefs

• also includes the presenter guiding students as to how the Bible might answer those same questions.

It may be helpful to watch the episode alone beforehand to establish when you need to hit the pause button and to decide if you need some prompting questions.

Do not expect comprehensive or conclusive answers. Students may never have thought before about a question like ‘What is God?’ and will find it difficult to put their thoughts into words.

The intention of these questions is to provoke thought and encourage students to grapple with the ideas. Experienced philosophers struggle with some of these questions. We are not likely to have easy or definitive answers, and teachers should not feel compelled to provide them. Instead, allow students to wrestle with identifying their own beliefs.

The intention is that students are encouraged to think about their own beliefs and presuppositions before looking at what the Bible says. As mentioned above, Bible verses are provided that offer some comment on how the God of the Bible, or Christians like Graham and Gladys Staines, may answer those same questions. This then provides opportunity for further discussion and thought, comparing one’s own beliefs to what God says in the Bible.

è STUDENT HANDBOOK

Whatever is in the Student handbooks is reproduced so that it is easy for you to see what your students see.

Where you see an icon like that below, play the video up until the PAUSE POINT (we have included the timestamp, but it will also be on the screen). All the icons like in this manual are direct links to the relevant videos. The videos are also hosted on www. CEPTeachersLounge.com (you will need the password issued with this manual upon purchase to access these). Then turn to the questions in the Student handbook.

When you have discussed the questions or ideas raised, press play and carry on until the next pause point. We hope you enjoy leading this process of discovery! 0:00—4:45 “What is truth?”

11

IS TRUTH? (PART 1)

—

WHAT

LESSON 1

LESSON 1

CONTEXT

• In 1999, an Australian missionary, Graham Staines, and his two young sons, were murdered by a mob in Keonjhar in India. Staines had been working in India for nearly 35 years, running treatment and rehabilitation centres for leprosy sufferers. He also supported local churches and preached the Christian gospel.

• In 2019, a film about the incident entitled The Least of These: The Graham Staines Story was released. The phrase ‘the least of these’ comes from Matthew 25, in which Jesus pictures his return and the final judgement (Matthew 25:31–46, NIV). You might like to read those verses and reflect on the following:

o What does Jesus mean by ‘the least of these’?

o What or who might ‘the least of these’ refer to in the film?

• India, the country in which the story takes place, is the seventh-largest country by area in the world, with a population of over 1.4 billion people. Modern India came into being in 1947 when it was granted independence from Great Britain.

• India had been part of the British colonial empire since 1858. Before that, other colonial powers, such as Portugal, had an interest in India, but most influential was the British East India Company, a very powerful and wealthy company that traded in, and effectively ‘ruled’, India from 1757. Prior to that, India was not a unified country—different regions were ruled by kings and emperors, who changed over the centuries as power shifted.

• India is known as the birthplace of Hinduism, but Buddhism and Jainism were present from early times. Islam was also introduced by invaders from the north, and the Mughal emperors who ruled kingdoms in the north of India for centuries were Muslim, although the majority of their subjects were Hindu. Sikhism also emerged during Mughal rule.

• Traditional accounts claim that the Apostle Thomas—who famously said of Jesus’ resurrection, ‘Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe’ (John 20:25, NIV)—travelled to India, but no significant Christian presence is known of in India until the arrival of the European missionaries, the most well-known of whom was William Carey, arriving in 1793.1

CORE CONCEPTS AND QUESTIONS

In relation to the murders:

• What is the view (that is, the ‘truth’ for that person) that saw the killing of Graham Staines as acceptable, perhaps even beneficial?

• What is the view (or truth) that saw the killing of the boys, Philip and Timothy, as acceptable?

• What are the possible views that consider these killings to be unacceptable?

In relation to God:

• What is God?

• How would you describe God?

• What does the Bible say about God?

Core concepts:

• Different ‘truths’ result in different interpretations

• All people have a moral principle

• Something acts as ‘God’ for everyone.

Some introductory questions to get students thinking:

• Is it right to help others if that means imposing your own beliefs in order to help?

Students may not have considered this dilemma before, but it is very much a ‘live’ issue in India. Indian journalist, politician and economist, Arun Shourie, argues in Harvesting Our Souls: Missionaries, Their Designs, Their Claims that Christians can help the oppressed, but if one conversion happens then that nullifies any good that was done.2 He would argue that it is not right to help others if that means communicating your beliefs as well.

• Is it right to allow others to cause harm if it is in line with their beliefs?

In contrast with the underlying assumptions of the above question, this question looks at the ‘rightness’ of murdering Staines and his two boys from the perspective of those who did so.

For another example, you might mention that sati (the Hindu custom of a widow burning herself to death or being burned to death on the funeral pyre of her dead husband) was previously practiced in India. Christian missionaries argued that it was not right to allow widows to burn just because their husbands had died, even though it was in line with their beliefs, and sati was eventually outlawed in 1829.

• Is it possible to help others and not impose your own beliefs?

2. Shourie, A 2006, Harvesting Our Souls: Missionaries, Their Designs, Their Claims, ASA Publications, New Delhi.

1. Keay, J 2008, India: A History, Grove Press, New York.

13

è STUDENT HANDBOOK

Start by reading the opening page of the Student handbook with the group. It helps to set the scene. Story is the language of the heart.

Story as a medium reflects the interconnectedness of all reality, to a lesser or greater degree.3 Well-told stories that reflect the truth of reality can move us and inspire us, thereby influencing culture (what we do) and making a difference in society.

With a story such as The Least of These: The Graham Staines Story, which is based on actual events, we wanted to provide an opportunity for you to engage not just your heart, but your mind also. These lessons give you the chance to discover the ideas, values and truths that each of us hold (consciously or unconsciously) and those that resulted in the events (both tragic and inspiring) that took place in India in 1999 and which, in turn, inspired the film.

The episodes are meant to be paused so that you can think about, and hopefully discuss with others, some answers to the questions presented. When you spot the ‘pause’ icon, stop, think, brainstorm, discuss. Don’t worry if you can’t come up with clear answers to the questions. There are no ‘right’ answers at this point, and experienced philosophers struggle with some of the questions we’ll look at in this unit.

Our purpose here is to get us thinking about what we believe and what we take for granted, and how those things influence our actions and choices in life.

We hope you enjoy the process of discovery!

Story is the language of the heart.

Story as a medium reflects the interconnectedness of all reality, to a lesser or greater degree.1 Well-told stories that reflect the truth of reality can move us and inspire us, thereby influencing culture (what we do) and making a difference in society.

With a story such as The Least of These: The Graham Staines Story which is based on actual events, we wanted to provide an opportunity for you to engage not just your heart, but your mind also. These lessons give you the chance to discover the ideas, values and truths that each of us hold (consciously or unconsciously) and those held that resulted in the events (both tragic and inspiring) that took place in India in 1999 and which, in turn, inspired the film.

The episodes are meant to be paused so that you can think about, and hopefully discuss with others, some answers to the questions presented. When you spot the ‘pause’ icon, stop, think, brainstorm, discuss. Don’t worry if you can’t come up with clear answers to the questions. There are no ‘right’ answers at this point, and experienced philosophers struggle with some of the questions we’ll look at in this unit.

Our purpose here is to get us thinking about what we believe and what we take for granted, and how those things influence our actions and choices in life.

We hope you enjoy the process of discovery!

‘WHAT YOU SEE AND HEAR DEPENDS A GOOD DEAL ON WHERE YOU ARE STANDING.’

Krish Dhanam, Business Evangelist

Andrew E Matthews, Educator & Screenwriter

‘What you see and hear depends a good deal on where you are standing.’ —CS Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew4

3.

4. Lewis, CS 1955, The Magician’s Nephew, The Bodley Head, London, p. 116.

McKee, R 1998, Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting, Methuen, North Yorkshire.

Krish Dhanam, Business Evangelist

Andrew E Matthews, Educator & Screenwriter

1. McKee, R 1998, Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting, Methuen, North Yorkshire.

2. Lewis, CS 1955, The Magician’s Nephew, The Bodley Head, London.

14

–THE MAGICIAN’S NEPHEW BY CS LEWIS2

WHAT IS TRUTH? (PART 1)

—DISCOVER EPISODE 1

KEY POINT Different ‘truths’ (world views) influence how we interpret what is right or wrong and therefore what actions we take, as well as our interpretation of reality.

0:00—4:45

‘What is truth?’

Therefore Pilate said to him, ‘So you are a king?’ Jesus answered, ‘You say correctly that I am a king. For this I have been born, and for this I have come into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears my voice’. Pilate said to him, ‘What is truth?’ (John 18:37–38, NASB1995).

IS TRUTH? (PART 1)

2. What is the view (or truth) that considers the killing of the boys, Philip and Timothy, as acceptable?

0:00—4:45

‘What is truth?’

king. For this I have been born, and for this I have come into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears my voice’. Pilate said to him, ‘What is truth?’ (John 18:37–38, NASB1995).

After you’ve watched a little of the first episode, you’ll be asked to think about the following three questions. Try to take a little time to discuss them or brainstorm so that you get into the process.

1. What is the view (that is, ‘truth’ for that person) that considers the killing of Graham Staines as acceptable, perhaps even beneficial?

USEFUL PHRASES - EXPLOITATION MUST BE STOPPED - WEAK GOVERNMENT - WE ALL DIE - SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST - AN EYE FOR AN EYE

3. What are some possible views that consider these killings to be unacceptable? USEFUL PHRASES - MURDER OR KILLING IS WRONG - VIGILANTISM - CHILDREN ARE INNOCENT - THE LAW - PROTECTION OF THE WEAK - ANARCHY

4. Over to you. So, was it wrong to kill? Why? Why not?

If your group is struggling to get started and you feel there is a need to stimulate thought, some introductory questions might be:

• What did the journalist think was true at the beginning of the film?

o The journalist, Manav, thought it true that missionaries were manipulating people and making money from their proselytising work, and that they only helped those who converted to Christianity. Consequently, he believed people like Graham were breaking the law and ‘forcing’ conversions, that is, using inducement of some sort.

• Where did he get those ideas?

o Although not stated explicitly, it is implied that Manav got these ideas from historical examples of this very practice (inducements to convert) and the fact that a law to prevent it had been introduced in the state of Orissa (now called Odisha).

• What did the editor think was true?

o The editor also believed that the missionaries were corrupt—and that his father had converted to Christianity. He further believed that the murderers must have had a legitimate motive for killing Graham and the boys, that it was a reaction to the apparent ‘wrong’ that Graham had been doing.

• What did the lepers think was true?

o Most of the lepers believed that they had done something in past lives to deserve leprosy, as per their belief system. They therefore considered themselves to be of little worth or value. However, the missionaries’ actions showed them love—God’s love in action.

• Where did they get those ideas?

o Hinduism, or a form with elements of animism mixed in that is believed among the lowest castes in rural India, teaches that human beings live in a state of reincarnation, with sins from past lives being visited on the individual in their current life (karma).

• Reincarnation: Hindus believe that all souls are immortal and reincarnate, living in one body and then another, evolving through experience over long periods of time. Physical death is a natural transition for the soul, which survives and, guided by karma, continues its long pilgrimage until it is one with its creator, God.

5 5 WHAT

—LESSON

KEY POINT Different ‘truths’ (world views) influence how we interpret what is right or wrong and therefore what actions we take, as well as our interpretation of reality. Therefore Pilate said to him, ‘So you are a king?’ Jesus answered, ‘You say correctly that I am a

1

15

• Karma: This is the law of action and reaction that governs life. The soul reaps the effects of its own actions. If we cause others to suffer, then the experience of suffering will come to us. If we love and give, we will be loved and given to. Thus does each soul create its own destiny through thought, feeling and action.5

• What did Graham Staines think was true?

o Graham believed that human beings are created in God’s image and so consequently all individuals have worth and value.

• Where did he get those ideas?

o As a Christian, Graham got these ideas from the Bible, which he believed to be God’s word.

After you’ve watched a little of the first episode, you’ll be asked to think about the following three questions. Try to take a little time to discuss them or brainstorm so that you get into the process.

1. What is the view (that is, ‘truth’ for that person) that considers the killing of Graham Staines as acceptable, perhaps even beneficial?

USEFUL PHRASES - EXPLOITATION MUST BE STOPPED - WEAK GOVERNMENT - WE ALL DIE - SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST - EYE FOR AN EYE

2. What is the view (or truth) that considers the killing of the boys, Philip and Timothy, as acceptable?

• Many thought that Graham was doing wrong so killing him was justified. Most people struggled to justify the killing of the boys. However, some activists argued that killing the boys was justified, or at least understandable, because they would have grown up to continue their father’s work. This belief was reflected in the editor’s dialogue in the film when he is confronted by Manav and says, ‘They [the boys] would have grown up to convert, like their father’.

5. Hinduism Today. ‘Karma and reincarnation’, Hinduism Today, September 5 2019, viewed February 2024 (hinduismtoday.com/ hindu-basics/karma-and-reincarnation/).

3. What are some possible views that consider these killings to be unacceptable?

USEFUL PHRASES - MURDER OR KILLING IS WRONG - VIGILANTISM

- CHILDREN ARE INNOCENT - THE LAW - PROTECTION OF THE WEAK - ANARCHY

4. Over to you. So, was it wrong to kill? Why? Why not?

KEY POINT The vast majority of people consider it ‘wrong’ to kill children. In fact, all people consider something ‘wrong’, which shows that we all have a moral principle.

4:45—7:38

‘All human beings are religious’

16

This is the argument Timothy Keller makes in The Reason for God:

‘When considering doing something that we feel would be wrong, we tend to refrain. Our moral sense does not stop there, however. We also believe that there are standards “that exist apart from us” by which we evaluate moral feelings. Moral obligation is a belief that some things ought not to be done regardless of how a person feels about them within herself, regardless of what the rest of her community and culture says, and regardless of whether it is in her self-interest or not … Though we have been taught that all moral values are relative to individuals and cultures, we can’t live like that.’

—Timothy Keller 6

4:45—7:38

‘When considering doing something that we feel would be wrong, we tend to refrain. Our moral sense does not stop there, however. We also believe that there are standards “that exist apart from us” by which we evaluate moral feelings. Moral obligation is a belief that some things ought not to be done regardless of how a person feels about them within herself, regardless of what the rest of her community and culture says, and regardless of whether it is in her self-interest or not … Though we have been taught that all moral values are relative to individuals and cultures, we can’t live like that.’

—Timothy

Keller 1

6.

If desired, there is an Extension activity at the end of this lesson based on Keller’s argument.

5. Do you agree with what Keller is saying about ‘moral obligation’? Select the opinion that most aligns with yours.

I have no moral obligation to anyone other than me. It is up to everyone to determine their own sense of morals and obligations.

There are moral values that exist independently of me. I don’t know where they come from, but I believe they exist. My morality comes from God. I try to live by that.

I feel a sense of moral obligation to my friends and family, but no-one else really.

Many students will find it difficult to think the idea of moral obligation through, so an example would help.

Slavery was once widely accepted. It then became much harsher under early colonialism due to the belief (truth claim) that some people were better than others. Then, later again, it was no longer accepted due to the belief (a biblical one) that all people are made in God’s image and should not be enslaved.

A more relevant example for our study could be leprosy, or sati (the historical Hindu practice of a widow sacrificing herself by sitting on her deceased husband’s funeral pyre). Most people would no longer consider the practice of sati or burying lepers alive as acceptable, irrespective of beliefs.

6. Keller says there are standards ‘that exist apart from us’. What do you think of this idea? Do you agree or disagree with it? Why?

Key to this discussion is the question of where our standards come from. Are they merely culturally created, or do they sit ‘apart from us’? And how can we tell the difference? Without God, all our standards are culturally created—mere social constructs that enable us to get along, provide a little hope and order in society, and, more cynically, allow the powerful to stay in power.

7. If truths are universal, as Keller argues, why then are there differences between cultures? Does this suggest that truths are not universal and each culture decides?

This question further hints that there are man-made standards and God-made standards, relative ‘truths’ and eternal, unchanging Truth. Dr Keller is also suggesting that these eternal God-made standards are somehow known to us and that when we willingly break them, we go against our own conscience . In Keller’s view, God has indeed placed ‘eternity in our hearts’ (Ecclesiastes 3:11).

6. Keller, T 2016, The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism, Penguin, New York, pp. 146–147.

1. Keller, T 2008, The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism Dutton, New York City, pp. 146–147. 5. Do you agree with what Keller is saying about ‘moral obligation’? Select the opinion that most aligns with yours. have no moral obligation to anyone other than me. It is up to everyone to determine their own sense of morals and obligations. There are moral values that exist independently of me. I don’t know where they come from, but I believe they exist. My morality comes from God. I try to live by that. feel a sense of moral obligation to my friends and family, but no-one else really.

Could a standard ever change over time? Or is Keller suggesting they don’t, that they are somehow eternal? What could possibly make a standard change? 6 KEY POINT The vast majority of people consider it ‘wrong’ to kill children. In fact, all people consider something ‘wrong’, which shows that we all have a moral principle.

8.

Keller says there are standards ‘that exist apart from us’. What do you think of this idea? Do you agree or disagree with it? Why?

universal,

Keller argues, why then are there

between cultures?

this suggest that truths are not universal and each culture decides?

7. If truths are

as

differences

Does

‘All human beings are religious’ 17

8. Could a standard ever change over time? Or is Keller suggesting they don’t, that they are somehow eternal? What could possibly make a standard change?

An example, as given above, is slavery, which went from being widely accepted centuries ago to today, where it is not only illegal in liberal Western democracies but anathema. Should students maintain that ‘of course slavery is evil’, it would be helpful to point out that had they lived in former times, they would have likely viewed it as the norm. Had they been Egyptian in the time of the pharaohs, would they really have pitied the Hebrew slaves?

Another point you might wish to raise is the question of what current standards and practices of our society today could possibly change over time and become no longer acceptable. Smoking might be one example.

One answer to the last question—what could possibly make a standard change?—is, of course, whether one acknowledges the love and wisdom and authority of God. When we submit to God’s authority, all his standards, his ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’, become ours.

KEY POINT Every human being is ‘religious’, that is, we all interpret our experience of reality through a philosophy or set of beliefs, whether we are aware of it or not. Something acts as ‘God’ for you.

Possible introductory question: ‘When people speak about God, what do they mean?’

From ancient times up until today, most people have believed in God. For many, their sense of morals and duty comes from what they believe about that ‘god’.

9. What is God?

10. How would you describe God?

In anticipation of the upcoming Bible verses, encourage students to consider the character traits of God, not just the physical (or lack of physical) traits.

‘How does the Bible describe God?’

7 7 KEY POINT Every human being is ‘religious’, that is, we all interpret our experience of reality through a philosophy or set of beliefs, whether we are aware of it or not. Something acts as ‘God’ for you. From ancient times up until today, most people have believed in God. For many, their sense of morals and duty comes from what they believe about that ‘god’. 9. What is God? 10. How would you describe God? WHAT DOES THE BIBLE SAY ABOUT GOD? IDENTIFY THE CHARACTERISTICS OF GOD MENTIONED IN THE FOLLOWING VERSES. ARE THERE ANY IMPLIED CHARACTERISTICS OR CHARACTER TRAITS? Genesis 1:1 (NIV) In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Genesis 1:27 (NIV) So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. Isaiah 6:3 (NIV) ‘Holy, holy, holy is the LORD Almighty; the whole earth is full of his glory.’ Deuteronomy 30:11 (NIV) Now what I am commanding you today is not too difficult for you or beyond your reach. 1 John 4:8–9 (NIV) Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love. This is how God showed his love among us: He sent his one and only Son into the world that we might live through him. Psalm 23:6 (NIV) Surely your goodness and love will follow me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of the LORD forever. Psalm 86:15 (NIV) You, Lord, are a compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness. Isaiah 1:18 (NASB1995) ‘Come now, and let us reason together,’ says the LORD God has always existed and is the first cause of all that is material. 7:38—9:50 ‘How does the Bible describe God?’

7:38—9:50

18

You might ask the group members to highlight, or underline, the characteristics of God mentioned in these following verses.

WHAT DOES THE BIBLE SAY ABOUT GOD?

IDENTIFY THE CHARACTERISTICS OF GOD MENTIONED IN THE FOLLOWING VERSES. ARE THERE ANY IMPLIED CHARACTERISTICS OR CHARACTER TRAITS?

Genesis 1:1 (NIV)

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. God has always existed and is the first cause of all that is material.

Genesis 1:27 (NIV)

So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. God creating human beings in his own image implies that we know something of God when we see what human beings can be like at their best: relational, created for community, rational, creative …

Isaiah 6:3 (NIV)

‘Holy, holy, holy is the LORD Almighty; the whole earth is full of his glory.’

God’s majesty/glory/holiness is evident throughout the earth.

Deuteronomy 30:11 (NIV)

Now what I am commanding you today is not too difficult for you or beyond your reach. God issues commands that he expects us to keep.

1 John 4:8–9 (NIV)

Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love. This is how God showed his love among us: He sent his one and only Son into the world that we might live through him.

God is both the source of love and love itself. His greatest demonstration of his love is sending his Son, Jesus, into the world.

Psalm 23:6 (NIV)

Surely your goodness and love will follow me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of the LORD forever. God is faithful. His goodness and love remain with us always.

Psalm 86:15 (NIV)

You, Lord, are a compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness. God is full of compassion, grace, patience, love and faithfulness.

Isaiah 1:18 (NASB1995)

‘Come now, and let us reason together’, says the LORD … God is rational and invites us to engage with him.

God has always existed and is the first cause of all that is material.

19

Should you require any additional verses on the character of God, a few more are listed below. You may wish to read some in context, since understanding the context will also reveal more about the God of the Bible and his relationship with his creation.

Note: Questions about the Trinitarian nature of the God of the Bible may need more time than you have available, so you may wish to ‘shelve’ that discussion until another time. However, if you choose to tackle it now, the New City Catechism (newcitycatechism.com) or older resources like the Westminster Confession (pcv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/WCF.pdf) may be helpful additional resources.

Revelation 1:8 (NIV)

‘I am the Alpha and the Omega’, says the Lord God, ‘who is, and who was, and who is to come, the Almighty.’

Exodus 20:22–23 (NIV)

Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘Tell the Israelites this: “You have seen for yourselves that I have spoken to you from heaven: Do not make any gods to be alongside me; do not make for yourselves gods of silver or gods of gold”’.

John 10:14–15 (NIV)

‘I am the good shepherd; I know my sheep and my sheep know me—just as the Father knows me and I know the Father—and I lay down my life for the sheep.’

John 12:27 (NIV)

‘Now my soul is troubled, and what shall I say? “Father, save me from this hour”? No, it was for this very reason I came to this hour.’

John 3:16 (NIV)

For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.

Colossians 1:16 (NIV)

For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him.

9:50—

Note: In this clip Krish refers to the New City Catechism (specifically Question 2 which is, What is God?) This can be accessed at https://newcitycatechism.com

REFLECTION

11. Consider how similar your concept of God is to the Bible’s concept of God. Write down any key differences or concepts from the Bible that you find difficult to accept.

8 8 REFLECTION 11. Consider how similar your concept of God is to the Bible’s concept of God. Write down any key differences or concepts from the Bible that you find difficult to accept. 12. We started today with the following statement: ‘Different “truths” (world views) influence how we interpret what is right or wrong and therefore what actions we take, as well as our interpretation of reality’. While we haven’t finished our thinking about ‘truth’, consider whether you think this statement is true. If not, what part of the statement would you change, and why? If you agree with the statement, can you think of examples from your own life where you have seen this in action? Well, that’s the end of the first episode, but as Krish said, we’ll need to think about the concept of truth a little more. Don’t worry if you don’t feel like you have answers yet. You may come to some conclusions by the end of this process; you may not. Either way, we believe you will discover something worthwhile. Just as we did. 9:50— end ‘What do we think of God?’

end ‘What do we think of God?’ 20

12. We started today with the following statement: ‘Different “truths” (world views) influence how we interpret what is right or wrong and therefore what actions we take, as well as our interpretation of reality’. While we haven’t finished our thinking about ‘truth’, consider whether you think this statement is true. If not, what part of the statement would you change, and why? If you agree with the statement, can you think of examples from your own life where you have seen this in action?

Two school examples might be when a student is offended by a classmate but finds it difficult to see their own fault in the situation. Or perhaps a student claims a teacher is picking on them, yet they find it hard to see that their own actions may be drawing the teacher’s attention.

Such ‘blindness’ extends to many areas in life, but a couple of easy examples are slavery, women’s suffrage and racism. For example, sometimes one group or race of people considers themselves to be superior—this is part of their world view. Consequently, they believe they are justified in oppressing or even eliminating so-called inferior groups of people. The many genocides or attempted genocides around the world are examples of actions taken because of a different world view.

Well, that’s the end of the first episode, but as Krish said, we’ll need to think about the concept of truth a little more.

Don’t worry if you don’t feel like you have answers yet. You may come to some conclusions by the end of this process; you may not. Either way, we believe you will discover something worthwhile.

Just as we did.

21

LESSON 1–ACTIVITY #1–QUESTION

EXTENSION ACTIVITY #1–QUESTION

1. In this image taken from the film, Manav, the journalist, has just been asked by his editor to endorse the violence committed against the Staines family. In the background is a statue of Mahatma Gandhi, who was well-known for his commitment to non-violence. What point do you think is being made by the director in using this shot?

22

LESSON 1–ACTIVITY #1–ANSWERS

EXTENSION ACTIVITY #1–ANSWERS

1. In this image taken from the film, Manav, the journalist, has just been asked by his editor to endorse the violence committed against the Staines family. In the background is a statue of Mahatma Gandhi, who was well-known for his commitment to non-violence. What point is being made by the director in using this shot?

Clearly the director is contrasting the two views, but he is also subtly pointing out to the audience that famous Hindu leaders and teachers like Mahatma Gandhi would not have condoned this choice of violence. The shot works to foreshadow the position that the main character finally takes, thus aligning himself with Gandhi on this issue.

23

LESSON 1–ACTIVITY #2

EXTENSION ACTIVITY #2

In The Reason for God, Timothy Keller argues that everyone without exception considers some things to be wrong. We all have, he claims, moral feelings or a conscience that we see as an obligation, not only on ourselves but on others also.1

1. List some things that you believe to be wrong. For example, murder, theft, road rage, cheating on tests … You may include personal habits, like not washing hands before meals or picking your nose in public.

2. List some things that you believe others should also definitely not do. In some areas we believe in ‘live and let live’—that is, it doesn’t matter what others do and believe. But there are also areas that we believe apply to all of us.

3. Compare your lists – are there items on your personal list that are different to your ‘universal’ list?

1. Keller, T 2016, The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism, Penguin, New York, pp. 146-147.

24