the Organic Way

Back to front gardening

Saving our Spuds

Future fears for fruit

Back to front gardening

Saving our Spuds

Future fears for fruit

How to process dried pulses for a delicious boost to your winter diet

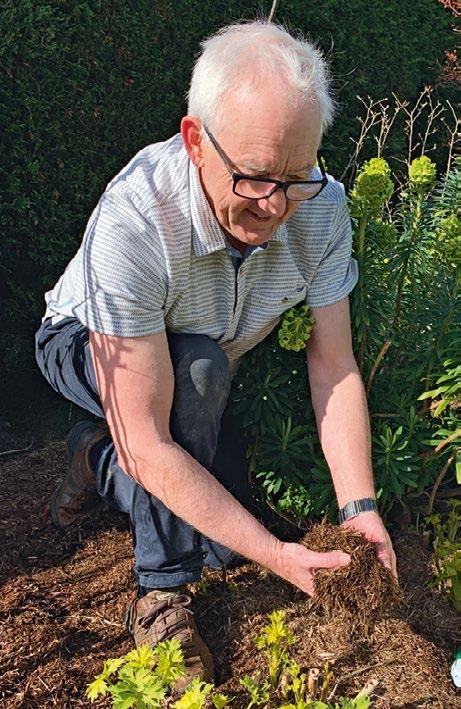

‘Strulch’ is a scientific success story. At Leeds University, Dr Geoff Whiteley found he could replicate a natural process which preserves straw. He and his wife Jackie brought the new environmentally friendly, biodegradable mulch to market . Fast becoming the preferred mulch of professional and amateur gardeners. Strulch is made from wheat straw and the mineralisation process preserves the straw and turns it dark brown. It has a neutral pH so can be used anywhere in the garden and it lasts for up to two years. Over time, the mulch improves soil structure and adds nutrients. The physical properties of the mulch and the added minerals deter slugs and snails. Strulch is available in 9kg bags from our stockists. For best value buy direct in bulk on pallets of 12, 25,40 or 48 x 13.5 kg bags.

Professional gardeners

see the benefits too:

We have been using Strulch for over 20 years, we use different mulches-home produced but Strulch is our ‘go to’ product where we need reliable weed suppression, moisture retention and preservation on the soil surface. Strulch is slow to breakdown, successful where there is competing demand from hedges in herbaceous border designs and non-rotational areas of kitchen/productive gardens. It is both lightweight and easy to apply and yet doesn’t blow off the bed, is quick to spread, it doesn’t clump or ball either and the depth of application can be varied easily. One can reliably get two years out of an initial application, and this allows us to vary our practices from year to year.

Elizabeth

Balmforth,

Head of Gardens, Mount

St John

as used by major horticultural gardens

“Plant conservation is a specialist business and needs ongoing resources – especially when looking after a living collection”

Until recently my computer password was a derivative of ‘Stop and Think’. It’s something I often want to shout from the rooftops –doesn’t anyone realise what could be lost if we don’t intervene?

Conservation was, for decades, something that seemed only to apply to the animal kingdom. We were all familiar with posters depicting polar bears, elephants and tigers. But it was still something that was happening ‘somewhere else’.

It’s only in recent times that the situation has become common parlance. This year, the dearth of insects in our gardens has been alarming. I haven’t clapped eyes on a wasp all summer and even the bramble and buddleja in the wilder corners of my garden have been devoid of butterflies.

In the plant world, rarity has tended to add to the mystique rather than sounding the claxon... but this year the penny has finally dropped. Without insects, flowers won’t be pollinated, seeds won’t be viable, and plants will fail – among them the food crops on which we depend.

Back in 1975, our founder Lawrence D. Hills was all too aware of the need to intervene in the conservation of vegetable seeds. Only those that were on the commercial listing for sale in the EU, or others that had been patented by large seed and food companies, were destined to survive. What was to be done about the many hundreds of others grown in small-scale market gardens, nurseries and allotments? They would have disappeared without trace were it not for the conservation efforts of the Heritage Seed Library.

Plant conservation is a specialist business and needs ongoing resources – especially when looking after a living collection. We don’t just put the seed in a cold store: we ensure it’s viable by continually growing it out on rotation. More than 7,000 people are members of the Heritage Seed Library – do consider becoming one of them. Together we’re safeguarding the genetic diversity of our nation’s home-grown vegetables, vitally important in the face of a changing climate when we increasingly need strong seeds. We’ve recently launched a fundraising drive asking for people to come on board as ‘Variety Champions’ to ensure we can sustain the Heritage Seed Library – which is 50 next year – well into the future. Turn to page 6 for more information. Please help if you can, because if we don’t intervene then who else will?

Fiona Taylor Chief executive

Organic gardener and writer Sally Morgan discusses the impact of our milder

Alice Whitehead explores the often-forgotten potential of front garden food and greenery

Garden Organic trustee Catherine Dawson on how to judge whether peat-free composts are environmentally friendly

Heritage Seed Library horticulturist Sophie Atkins explains how to process peas and beans as a dried crop

Our experts share their knowledge and advice

Our own Emma O’Neill on companion planting with flowers before vegetables

Readers’ tips, triumphs and memories

Anton Rosenfeld on the carbon footprint of urban vs conventional farming

Josiah Meldrum chats to Chris Collins

Prof. Tim Lang on when to harvest your produce

Garden Organic brings together thousands of people who share a common belief – that organic growing is essential for a healthy and sustainable world.

Through campaigning, advice, community work and research, our aim is to get everyone growing ‘the organic way’.

Patron: His Majesty The King

President: Professor Tim Lang, PhD, FFPH

Chair: Angela Wright

Vice-Chairs: Mark Mitchell and David Robinson

Treasurer: Keith Arrowsmith

Garden Organic members play a vital role in supporting our charity’s work. You could get even more involved in helping us to spread the word about the many benefits of organic gardening by:

l Joining our Heritage Seed Library

l Making a donation

l Volunteering

To find out more – or for any other enquiries:

T: 024 7630 3517

E: enquiry@gardenorganic.org.uk

W: www.gardenorganic.org.uk

Organic Way is published and printed on behalf of Garden Organic by:

CPL ONE: www.cplone.co.uk

T: 01727 893 894

EDITORIAL TEAM:

Wendy Davey, Hannah Rogers, Alice Whitehead, Pauline Pears

ART EDITOR:

Caitlyn Hobbs

ADVERTISING:

Caroline Harland

E: caroline.harland@cplone.co.uk

T: 01223 378 045

We will consider all contributions, although we are unable to pay for them. Manuscripts, photographs and artworks are sent at owners’ risk and may not be returned. The articles in this magazine do not necessarily reflect the view of Garden Organic, nor are advertisers’ products and services specifically endorsed by Garden Organic.

Garden Organic has made every effort to trace and acknowledge ownership of all copyrighted material and to secure permissions. Garden Organic would like to hear of any omissions in this respect, and expresses regret for any inadvertent error. The decision whether or not to include materials submitted for inclusion (whether advertising or otherwise) shall be entirely at the discretion of Garden Organic. No responsibility can be accepted for any products or services that are the subject of any advertisement included in this publication and Garden Organic is not responsible for any warranty or representation whatsoever with regard thereto.

All text and images © Garden Organic unless otherwise indicated.

The Magazine is Printed on FSC® certified paper, which is responsibly sourced, certified to have been harvested from controlled sources and produced in a responsible manner. The wrapping is made from Polycomp™. It can be disposed of on a compost heap, in a household garden waste bin, food waste bin, or you can use it to line your food waste bin.

Our members’ magazine is published three times a year. We always love to hear our members’ news, views and organic gardening tips.

To contact the Editor: E: editor@gardenorganic.org.uk

P: Editor, Garden Organic, Ryton Organic Gardens, Wolston Lane, Coventry CV8 3LG

Cover Image: Dried borlotti beans

Garden Organic, the working name of the Henry Doubleday Research Association, is a registered charity in England and Wales (number 298104) and in Scotland (SCO46767)

Next time you walk along a town or city street be careful where you tread. A Berlin study has found hidden life in pavement cracks.

The study, Urban pavements as a novel habitat for wild bees and other groundnesting insects, found up to 66 species of invertebrates happily sharing pavement space with people.

It discovered bee and wasp species liked to nest in urban pavements and cobbled streets, with proximity to insect-friendly flower gardens having an impact on numbers.

In August, we joined forces with the Pesticide Action Network to call for a ban on pesticides in public spaces such as playgrounds, parks and pavements. These toxic chemicals, used mostly for aesthetic reasons, pose significant risks to human health, pets and native wildlife.

Support the campaign and sign the petition at https://pesticidecollaboration.org/gopesticide-free – until the end of October.

We’re very excited to welcome our first ‘Variety Champions’ to the Heritage Seed Library.

These Champions have sponsored a heritage vegetable variety so they can support the invaluable work of the library in conserving cultivated biodiversity. As Champions, they receive limitededition heritage seeds and an invitation to an exclusive Variety Champion event at the Heritage Seed Library.

Each year, the Heritage Seed Library needs to grow, maintain, harvest and store more than 100 varieties to replenish ageing seed stock. Variety Champions help cover the hundreds of thousands of pounds it takes every single year to conserve these varieties.

Over the past century, we’ve lost many hundreds of local vegetable varieties that have been grown for generations by seed companies, families and communities. The narrower our choice of varieties to grow, the more vulnerable we are to crop failures.

If you’d like to help secure the future of an important piece of genetic diversity, become a Heritage Seed Library Variety Champion for £25 a month. Find out more by calling 024 7630 8210 or visiting gardenorganic.org.uk/variety-champion.

Covering an area of 728,000ha, the UK’s private gardens can have a massive positive impact on biodiversity, especially with the increase in urbanisation. But whether this potential is realised, is ultimately down to human behaviour. This year, a number of research papers have covered this complex area.

A study in Hungary, Bridging biodiversity and gardening (doi.org/nhcz), examined differences in gardening practices between socio-demographic groups including “biodiversity positive” practices such as avoiding pesticides, leaving undisturbed areas and reducing the frequency of mowing.

Middle-aged respondents demonstrated more biodiversitysupporting activities than those over 55. While those in towns showed the least biodiversity-positive activity, those living in cities and the countryside fared better.

Closer to home, the UK Garden Butterfly Survey (doi.org/nhc3) found that leaving some long grass was the key message as it can increase the abundance of many butterflies. Allowing some ivy to flower was important for species such as holly blue, red admiral and comma. Taking part in the Big Butterfly count has also been shown to decrease anxiety, improve wellbeing and increase the tendency to notice nature, according to a study published in Biological Conservation (doi.org/nhcx).

Finally, a study in Wales, published in Landscape and Urban Planning (doi.org/nhcv), examined the links between biodiversity in green spaces and mental wellbeing. The study found that even when all the socio-economic factors often linked with positive environmental green spaces are removed, there’s still a definite link between bird species richness and mental wellbeing.

A new technology could spell the end for Japanese Knotweed. A very fine material called MeshTech is laid over soil containing the plant in winter, and staked down lightly. When the shoots emerge through spring, they are continually broken to pieces as the stems grow, eventually exhausting the plant and killing it.

With the UK throwing away around 9.5 million tonnes of food in a single year — it’s more important than ever to show people how to recycle waste by composting.

We now have 11 Compost Demonstration Sites around the UK, where Master Composters demystify composting and provide all-important life skills to communities.

The expansion couldn’t have come at a better time for local authorities. Upcoming changes in waste legislation will require all local authorities to collect food waste separately, with home composting the most environmentally friendly way of dealing with unavoidable food and garden waste. To find out more about visiting or volunteering, go to gardenorganic.org.uk/master-composters.

Taking a moment to consider leaving a gift to charity in your will after looking after family and friends — can make a positive and lasting impact. Leaving a legacy gift to Garden Organic is an investment in an organic, sustainable future, and it helps us research, inform, support and inspire more people about organic gardening and sustainable growing spaces. Find out more at gardenorganic.org.uk/legacy-gift

Our recent survey of allium leaf miner gives an interesting overview of the spread of the disease across the UK. Survey participants suggest the disease has spread slowly since 2017, with limited proliferation northwards and no cases recorded in Scotland. For more details head to gardenorganic.org.uk/allium-leaf-miner-survey.

You can play an important role in food security and plant diversity by selecting and growing HSL varieties at home.

In December, our Heritage Seed Library Seed List 2025 will offer 170 delicious varieties, across 25 vegetable types. Almost half of these are certified organic seed, and 18 are new to the list this year.

As always, the list is the culmination of a lot of hard work, both at Ryton and by our volunteer Seed Guardians, who grow our seeds in their gardens and allotments across the UK. Last year’s growing season produced the equivalent of 107,000 packets of seeds!

If you’ve not had the treat of sampling six free packets of our rare and unusual veggies as a member of the Heritage Seed Library, then please head to gardenorganic.org.uk/join. Your support helps ensure future generations can continue to enjoy this fabulous range of historic varieties.

It’s long been known that bees use buzz pollination to extract pollen from flowers – but now a new study suggests they might headbutt them too.

The research, published in Current Biology, used slow motion cameras to film the bumblebees, which showed them chewing and ramming the anthers of flowers with their heads, in order to get more pollen out. The scientists aren’t sure how effective this is yet, but it appears more pollen was released.

Members will be able to access discounts on organic seeds and wildlife habitats — thanks to our exciting new partnerships.

We’re delighted to be able to offer member discounts with two sustainable companies: Tamar Organics and The Wildlife Community.

Tamar Organics offers an extensive range of organic vegetable and flowers seeds, including green manures. The Wildlife Community provides feeders and houses for birds, hedgehogs, bees and frogs, as well as plasticfree gardening products.

Log in to the members area at gardenorganic.org. uk/members/login to learn about your discounts.

There has never been a better time to encourage family members and fellow gardeners to start their organic growing journey.

As the UK wide charity for organic growing, we’ve been pioneering biodiversity and organic growing since 1958. We champion sustainable growing practices that help encourage biodiversity, fight climate change, and protect the natural environment.

Together we can support new growers on a range of topics including composting, veg growing, encouraging biodiversity into a growing space plus so much more.

Gift membership starts from £39 a year and includes the same fantastic benefits that you enjoy, such as:

• Welcome pack including our popular Veg Grower’s Planner

• The Organic Way members only magazine sent three times a year

• Exclusive member discounts with our range of partners

• Free or discounted entry to our partner gardens across the UK including free entry to our organic demonstration garden at Ryton

• Exclusive early bird discounts on our courses and pre-booked garden tours

• Monthly Organic Matters email newsletter, full of seasonal advice & updates on our work - Plus much more!

or call us on 02476 308210.

Organic gardener and writer Sally Morgan discusses the impact our milder winters are having on fruit production

There's plenty of advice in magazines and on social media about creating drought resilient gardens, harvesting water or even coping with floods. But there’s another problem that I feel is just as worrying and getting very little airtime. And that’s how our fruit trees are responding to milder winters and earlier springs.

Climate change affects fruit trees in many ways. Flowering is a key time of year, and the trees depend on insects to pollinate their blossom. But there’s such a narrow window of opportunity – just a couple of weeks for insects to find and pollinate the flowers before they die.

We’re all aware spring is arriving earlier, and on average, our fruit trees are opening their buds more than two weeks earlier compared with the 1980s. With premature springs, the chances of a mismatch between the appearance of the blossom and the activity of insect pollinators increases. There’s also the chance that cross pollination between different cultivars doesn’t occur –plus, there’s the added risk that buds that have opened too early get frosted.

Fruit trees, like many other deciduous trees and shrubs, have a mechanism to stop them coming out of their winter dormancy too soon: opening their flowers and being at risk of frost damage. They must experience a certain number of chill hours before opening their buds.

A chill hour is an hour of time when the air temperature is below 7°C between 1 October and 1 April. This mechanism is critical to successful fruiting, and it means the trees need to experience five to six weeks of chilly weather, something that was quite common in the past. But as we experience global warming, our winters are becoming milder and cold weather with frosts is becoming increasingly infrequent, so the number of chill hours is declining.

This has been particularly evident in southern England. Recent research by Carlota González Noguer of the University of Reading shows there’s been a significant decline in chilling in just the last few years. Similarly, Paula Fleming, the orchard gardener and tutor at Le Manoir aux Quat’Saisons in Oxfordshire, estimates their trees are getting around 300 fewer chill hours than before.

Chill ensures the plant remains dormant through winter, conserves its energy resources and doesn’t open its buds too early and risk frost damage. The production of buds and leaves is a result of a complex system that’s reliant on the correct signals. Get the wrong signals and the plant becomes confused, so insufficient chill can result in the poor development of fruit buds, delayed flowering, or buds may open too early. It can also cause floral abnormalities, such as reduced fruit set and clusters of small

Fruit Watch is a citizen science project based at the University of Reading that’s monitoring changes and trends in fruit tree flowering dates across the UK. You can get involved by gathering data on a wide range of fruit trees, which will help scientists understand how climate change is affecting our orchards. Find out more at https://fruitwatch.org

or malformed fruits and even flowering at the same time as fruiting.

The number of chill hours that are required for apples, for example, varies from 200 to 1,000+ hours. Those cultivars typical of warmer climes needing 200500 hours, while those from more northerly regions requiring 800-1,000. Plums and damsons generally require 1,000 hours or more, while medlars, quince, pears and mulberry need far less.

Obviously, there’s nothing we can do about the lack of chill hours, so we have to adapt. Fruit trees have a long life, and a tree that we plant this autumn will be maturing in 10 to 15 years’ time. Hopefully, it will continue to produce fruits for many years beyond - but will it be able to cope with the climate of 2040?

The choice of cultivars that we plant now is critical. Many of our favourite heritage cultivars were developed 200 to 300 years ago as the country was experiencing the ‘Little Ice Age’, when it was considerably cooler and wetter. I had a look through Apple Varieties of Somerset – a Guide to the Origins of Somerset Apples by June Small of Charlton Orchards. This document identifies 156 cultivars that are linked to Somerset, the vast majority of which were developed in the 19th century, when the weather was particularly wet and cold.

With the climate changing quickly, we need to be savvy about our fruit tree choices. If you live in the south, for example, you definitely don’t want to choose cultivars with a high chill hour requirement, but finding information about chill requirements is difficult. Fruit tree suppliers give plenty of information on pollination

There’s a surprisingly wide selection of French apple cultivars, including cider, available in the UK, many of which come from western France:

• Api and Gros Api – dessert apple

• Belle De Tours – cooking apple

• Canadian Reinette or Reinette du Canada – russet style apple

• Calville Rouge D’Hiver – cooking apple

• Calville des Femmes – large yellow-green cooking apple

• Michelin – cider apple

• Orlean’s Reinette – dessert apple.

requirements, etc, but nothing on chill. Given the fact most of our heritage apples date back at least 100 years or more, I think we have to assume most will have a chill requirement that suited the climate of the time.

There are some low chill cultivars available in the UK, but the selection is limited, and include Braeburn, Bramley, Lord Lambourne, Saturn, Spartan, Crispin and Gala Galaxy. Some commercial fruit growers in Kent are looking to the future and are planting more international cultivars, such as Granny Smith, Golden Delicious, Gala and Fuji. But it’s not straightforward as some of these cultivars, such as Granny Smith, come from Australia. Granny Smith has a low chill requirement of just 200 or so hours, but it needs a long growing season and lots of sunny weather.

You may have to look further afield. Foresters are recommended to look 200 miles south to regions with a climate that we may be experiencing in the future, and the same applies to fruit trees. If you live in northwest Wales, you might choose cultivars typical of Cornwall and Devon. I live in Somerset, so I’ll be looking 200 miles south to Normandy and Brittany.

In my own ‘climate change orchard,’ I’ve opted for apple, pear and plum varieties that are French in origin alongside medlars and quince (200-400 chill hours). I’ve also planted a couple of Asian pears (Nashi) that have grown well and are starting to fruit and I’m considering some Japanese plums (Prunus salicina). These small fruit trees have a wonderful blossom, dark red fruits and lower chill requirement than European plums. They are hardy but the flowers open early and may be at risk of frost, so I’ll need to find a sheltered position.

With our changeable climate, it’s difficult to know what to do. But diversity is always best, so I recommend you choose a wide range of apple cultivars to ‘hedge your bets’ and include other species with a lower chill requirement, such as pears, medlars and quince.

Alice Whitehead explores the often-forgotten potential of front garden food and greenery

Green spaces matter – no matter their size. And the most local, and often smallest, of these is the front garden. Just like parks and allotments, this linked-together patchwork of doorstep greenery across the UK makes a big impact on the local environment and its wildlife.

Yet for many, this space outside the front door is a forgotten patch of land. RHS research in 2020 suggested more than a third of front gardens contain less than a quarter of plant cover, and a staggering 2.5 million have no plants at all.

Unlike back gardens, these privately-owned spaces are public and highly visible. Wrapped up with people’s social identity and the idea of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’, there has been an increasing emphasis in the past few decades on low maintenance, secure and tidy gardens. Lawns have been replaced with paving or artificial turf, and hedges with walls and fences.

Front gardens also need to be carefully choreographed to accommodate bike sheds, wheelie bins, driveways and cars. When dropped kerbs became permitted development in the mid-1990s, more people grubbed up their front gardens in favour of a car park. The result: a space that is more garage than garden.

But if you flip the idea of front gardens being ‘just for show’ on its head, and look at their value as growing spaces, you begin to see their untapped potential.

Higher-quality street greenery has been associated with improved wellbeing, mental health and reduced stress. Green spaces such as these increase social cohesion among communities, with front garden activities becoming moments for neighbours and passers-by to meet and chat. They can also improve the look and feel of the local community.

Streetscape vegetation, such as trees, verges and well-tended front gardens, can have far-reaching, positive impacts on the wider environment and wildlife. Replace tarmac or paving with lawns, hedges, and soil and you’ll soak up rain. Non-permeable surfaces, by contrast, increase run off and surface water by as much as 50%.

Add plants and you’ll reduce and regulate the temperature, reflect solar energy and provide shade. The surface temperature in an urban green space may

be 15-20°C lower than that of the surrounding streets, and the air temperature 2-8°C cooler1. Hard, reflective surfaces, on the other hand, can contribute to the ‘urban heat island effect’ and poorer air quality.

In built-up areas, front gardens act as green corridors, breaking up concrete and providing insects, birds and mammals, such as hedgehogs, with shelter and food.

So, what should you consider in order to maximise the potential of your doorstep plot?

By their nature, front gardens tend to be small and awkwardly shaped – but there are lots of opportunities to use vertical space such as walls and window planters. Be creative with wheelie bin screens that include room for pollinator-friendly plants, or bike sheds hidden under a pallet wood roof planted up with sempervivums.

It’s easy to design a front garden so that it’s facing the street, but think about what you’d like to see from your windows. Use diagonal lines in the largest areas to give the effect of a wider area leading from the door.

Consider, too, where the rain shadows are; these are any areas protected by the roofline. Plants under the eaves will need more watering, so think about adding a water butt to a downpipe. Good compost will help conserve water, use a mix of topsoil, peat-free or your own homemade compost and water-retaining sand in containers. Go for the largest container you can, so they dry out less quickly.

Parking close to the house can be an important consideration, particularly if you have mobility difficulties. In 2019, the Office for Low Emission Vehicles began offering grants to householders to install home charging points for electric vehicles – which has encouraged more people to create driveways where they can charge their electric cars. With increasingly limited off-road parking and the introduction of controlled parking zones, this has put added pressure on front gardens.

Unfortunately, this has resulted in many of them being paved or concreted over, which has led to a sharp increase in surface water flooding in urban areas. To counterbalance this, choose permeable paving such as

matrix paving or ‘grasscrete’, which allows rainwater to drain through and plants to grow. Or try a paved track for cars, with rockery-style planting of creeping Jenny and thyme in between.

Any areas away from the car and the bins can be filled with plants. Big bold foliage is often avoided, but it can give the impression of a more expansive space. And add flowers for wildlife. In autumn, late bloomers such as asters, betony (Stachys officinalis), sneezewort (Helenium), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia) and Japanese anemones (Anemone x hybrida) can bring colour and pollinators.

Front gardens often have micro-climates, because of the way they’re surrounded on several sides by walls and adjoining houses, which makes them ideal for food growing. Peas, climbing beans and squash can grow up wigwams and walls, or over an arched porch; unused recycling boxes can be repurposed for salads and carrots.

Consider ‘edimentals’ too – plants that look good and taste good. In autumn, this could be rainbow chard, flowering herbs and edible flowers, such as viola.

Tie your front garden colour scheme in with your door or windowsill paint and your front-step allotment will have creature, community and kerb appeal.

Reference 1: Aram, Farshid, Ester Higueras García, Ebrahim Solgi, and Soran Mansournia. “Urban green space cooling effect in cities.” Heliyon 5, no. 4 (2019).

If you’re turning your front garden into a mini allotment and you’re next to a busy road it’s worth considering the effects of pollution on your edible crops.

While leaded fuels have thankfully been phased out, exhaust fumes can still emit hydrocarbons, zinc, nitrogen oxides and sulphur dioxides, which may land on soil and vegetation.

According to the Chemical Hazard and Poisons Report 2015, a study of 60 composted samples of UK street leaf sweepings contained hydrocarbons and number of heavy metals and inorganic chemicals.

Particulate matter (PM) and vapours from exhaust emissions and tyre wear can leach into soil and vegetation from road run-off and traffic spray. Road surface abrasion i.e. dust, grit and salt can also have an effect. The impact is greater the busier the road, and the closer your garden is to the road.

What you can do:

1. Grow in containers. If you’re worried your soil may be contaminated, do a soil test – and grow in pots and raised beds rather than directly in the soil.

2. Nurture your soil. Keep plants healthy from the bottom up by mulching and improving your soil with homemade compost or organic soil conditioners. A layer of mulch can also be a physical barrier to contaminants that lie underneath.

3. Create screening. A hedge can absorb pollutants, dirt and noise while also attracting birds and bees. Tough plants to consider include privet, yew and pyracantha, which has thorns for added security.

4. Wash your veg. Most harmful particulate matter washes off, so ensure you give your produce a good rinse before eating. Remove the outer leaves of greens where soil particles are most likely to be located, and peel root vegetables before cooking.

AWe are all aware that we should no longer be using peat – but how do we judge that peat-free alternatives are less environmentally damaging? Senior associate and technical lead at Melcourt Industries Ltd, and Garden Organic trustee, Catherine Dawson provides some advice

much greater variety of ingredients is being used in bagged compost, or growing media, than ever before. This can present challenges around usage and make it difficult for gardeners to ensure they’ve made an environmentally friendly choice.

What’s more, many brands of compost do not specify the exact ingredients, with packaging often being littered with descriptions such as ‘sustainable’, ‘natural’ and ‘biological’ – which are largely meaningless in terms of making an informed purchasing decision.

The Responsible Sourcing Scheme for Growing Media can help navigate this minefield. It was created as a direct outcome of the Government’s 2011 peat alternatives task force. Representatives from all sides of the debate had a part in its creation and many of these people, including myself, remain on the steering group.

Everyone from big retailers, to NGOs, Defra, growers and manufacturers have played a part. The wide diversity of input has ensured acceptance of the scheme across the breadth of the horticultural industry and the conservation movement.

So how does the Responsible Sourcing Scheme help gardeners make better choices? The scheme requires manufacturers to count the impacts of their ingredients across seven criteria – energy, water, habitat and biodiversity, renewability, resource use efficiency, pollution and social compliance. These impacts are counted and used to produce a final product score, calculated from the amount of each ingredient in the mix. Scores range from A to E, with A indicating the least impact across the seven criteria. Consumers can look out for the Responsible Sourcing logo on the bags of participating manufacturers and obtain a score either by following the on-pack QR code or by looking up the product at responsiblesourcing.org.uk.

The final score is a distillation of a huge amount of data. For example, for energy, all of the energy consumed in the making of each individual ingredient, together with the transportation between processing sites, is counted. At Melcourt most of our ingredients originate in UK forests so we’re required

to count the energy consumed from tree planting, through felling, debarking, composting and screening together with all of the lorry transport between sites. It’s a lengthy and complicated task.

Another useful example is that of coir. It’s commonly thought that bringing coir (a by-product of the coconut industry, and globally a widely used peat alternative) from India or Sri Lanka must be costly in terms of carbon emissions. By counting the energy for every stage in its processing and transportation, however, we can see more clearly how this material compares with British-produced ingredients. And it’s not as stark a difference as is sometimes supposed.

There are several reasons for this. The coir is washed with naturally collected rainfall and dried using sunshine as a natural energy source. Next comes compression into blocks, which provides very efficient use of transportation and high out-turn volumes once the coir is reconstituted at UK growing media manufacturers’ sites. And transportation is by sea, which is one of the most efficient forms of freight haulage in terms of the energy required per unit of weight and distance.

This is a good example of how we are now using data and evidence to demonstrate impacts. Added confidence for the consumer comes from the fact that the scheme is fully externally audited.

The energy required to manufacture and transport a product can plainly have an environmental impact, but the scheme also recognises that factors such as water use and habitat loss are important. Renewability is relatively easy to score with peat and minerals such as loam, perlite and vermiculite at the bottom end of the scale and green compost, bracken and wool at the top.

The importance of social compliance is being acknowledged in similar schemes across many industries and this one is no exception. The Responsible Sourcing Scheme recognises we cannot label a compost as responsible if the employment conditions at any of its manufacturing stages are not compliant with modern-day standards.

Manufacturers are also required to carry out a prescribed growing trial alongside the scoring system, as products must also function effectively.

Most UK growing media manufacturers are members, although not all have scored all of their products yet. The scheme is also open to retailers and growers, and more of these are signing up each month. In future, it will become harder to gain the same scores as requirement for continual improvement will be built in.

It’s highly likely the new government will resurrect the intention to ban the use of peat, although no timescales have been given at the time of writing. But as more alternatives to peat come into use, it will be more important than ever that ingredients are scrutinised, so they not only work as effective growing media, but are also as benign as possible in terms of their environmental and social impacts.

Up to 95% of UK peat bogs are degraded or gone, due to drainage for agriculture, forestry and peat extraction, with huge amounts sold as bagged compost. It can take a whole year to create just 1mm of peat: that’s 1,000 years before the bog can start functioning again as a rare and special habitat, and carbon store. In September, the Peat-free Partnership, of which Garden Organic is a member, sent an open letter to the UK Government to legislate to end peat sales. But you can go peat-free now! Here are our top tips:

1. Make your own compost mixes. As with any consumable, bagged growing media are packed in plastic and moved around in lorries, so it’s important to make as much homemade compost as you can. You can find compost recipes at gardenorganic.org.uk/ compost-recipes.

2. Don’t skimp on how much you spend. Unfortunately, cheap peat-free compost can give you poor results. Invest in your garden and growing by buying the best you can afford.

3. Check what you’re buying. Clearer labelling on peat-containing products is desperately needed. Peat can be found in many pre-potted plants, leafy salads, and houseplants. Mushrooms are also one of the few vegetables that are currently grown in peat so any packs you buy at the supermarket will have a peat footprint. Always check what you’re buying and make sure your garden centre or supplier knows you’d like to buy peat-free products.

4. Water little and often. Because of their coir and woodchip content, some peat-free mixes can dry out more easily. If they have a coarse texture, it can mean they appear dry on the surface but may still be damp further down. Check by putting your finger around one inch into in the soil. Don’t let them dry out otherwise they can be difficult to water again, as the water runs off the top. If this happens, sit the pot in water to let it draw up the moisture.

5. Feed after four weeks. Most peat-free composts provide fertiliser up to four weeks, but after this you can make your own comfrey liquid feed for hungry crops and container-grown plants. For instructions, visit gardenorganic.org.uk/comfrey

We often overlook the potential of peas and beans as a dried crop, but Heritage Seed Library horticulturist

Sophie Atkins shows how to process them for a delicious winter staple

To the modern gardener, the taste of freshly picked beans and peas are a highlight of summer. However, our ancestors would have grown these vegetables not to be eaten fresh, but for drying and storing – a tradition that continues in many cultures around the globe.

A perfect example of the historic use of peas can be found in the British nursery rhyme Pease Pudding Hot, dating from the 18th century, which describes a thick pea soup. Further afield, in West Africa, beans were first domesticated around 2000BC by the Yoruba people, and have remained a part of local farming and traditional dishes to this day.

The time-honoured skill of growing and drying peas and beans has fallen out of favour in recent years, particularly with the advent of tinned and frozen produce. But our Heritage Seed Library holds many heritage and heirloom varieties within its collection, which were bred for drying and using in soups and stews rather than eating fresh.

When eaten fresh, they have a nutty flavour and mealy texture that, by modern standards, can be a little off-putting. This can lead to confusion about the best way to eat them. However, simple changes to the way we grow and cook them gives us an amazing opportunity to eat better, reduce our impact on the environment, and become more self-sufficient. And just for the record, when dried and used properly they taste fantastic too!

Peas are straightforward to grow, but if you’re growing for drying, it’s best to sow earlier to allow for the longer growing season needed for pods to fully mature.

Start off indoors in February, to avoid mice and rotting, then harden off and plant out in late March. You may find you need to net your plants to protect them from pigeons and pea moths, but other than that just leave them to it.

To grow runner beans for drying, simply grow them as you would for eating. Sow between April and May indoors, then plant out May to June when the frosts have finished. While you can harvest some of the pods for eating fresh, leave a good supply to fully mature on the plant.

From late summer onwards, pods will be ready to harvest when they become dry and crackle like paper, with the peas and beans rattling inside when you tap

When choosing pea varieties to grow for drying, make sure you go for the old-fashioned, smoothseeded varieties that were bred for this purpose. Similarly, old-fashioned types of beans were bred to have flavourful beans as well as pods, unlike modern commercials where the focus is just on the pods.

Peas: ‘Irish Preans’, ‘Raisin Capucijners’ or ‘Latvian Grey Pea’ – grown in Latvia for more than 100 years with beautiful lilac and crimson flowers. Or, from this year’s Heritage Seed Library seed list, ‘Carlin’. This ancient pea was traditionally eaten on Carlin Sunday to commemorate the arrival of a shipload of life-saving peas in besieged Newcastle in 1644.

Beans: ‘Black Magic’, ‘Chapman’s Purple’ or ‘Meesha’ with scarlet flowers. Or, from this year’s seed list, ‘Lubenham’, which was grown in Leicestershire since before the 1950s with long pods and pretty mottled seeds.

All of these seeds are part of the Heritage Seed Library collection, with Carlin, Latvian Grey Pea, Lubenham and Meesha available in the 2025 Seed List, launched in December.

them. Don’t leave them any longer than this or the pods will ‘shatter’, meaning they’ll split open and fling seeds all over your garden.

Pod your peas and beans, and spread them out on a tray for roughly two weeks to dry fully. Somewhere out of direct sunlight, away from a heat source but with plenty of airflow, is ideal. Seal in an airtight container. Glass jars work well and look particularly pretty with colourful beans inside.

Peas will last for at least two years, and beans for three. However, the longer they’re stored the more likely they are to lose flavour and firmness once cooked.

When it comes to using your dried peas and beans, the process is a simple one, but being organised is helpful. First, clean by rinsing them under running water, finishing with a good shake. Pour into a large saucepan or bowl and add enough water to cover. Pop a plate or towel over the top and leave to soak overnight. Alternatively, place in the fridge and leave for 12 hours. The beans will look a little plumper, while the peas should swell noticeably as they take in the water. If a few of them don’t, don’t worry – just cook them with the rest and they’ll be fine.

After soaking, drain and place in a pan and cover with fresh water. Bringing to the boil, then reduce to a simmer until cooked through and tender. When they can be mashed with a fork, they’re ready. This should take 45-60 minutes for beans, and 25-35 minutes for peas. A pressure cooker will help to speed this up. Alternatively, for soup and stews, simply pop your soaked beans or peas straight in and leave until cooked through.

Sometimes, the old ways are better, and the people of the past knew best. Organically growing and preserving your own food not only gives you a level of self-sufficiency, but it also lessens your impact on the planet, while helping to save a few pennies.

If you’ve tried these heritage and heirloom legume varieties in the past and found them to be less than tasty, give them another chance – and use them as they were meant to be used.

This recipe is a cosy favourite for the mellow autumn and chilly winter days ahead. You will need roughly 350g of dried runner beans. Serves four people.

1. Start by browning six chunky meat or vegetarian sausages and set aside. Roughly chop one large onion, two garlic cloves, one celery stick and one large sweet potato and soften in butter in a large pot on the hob, before adding the sausages.

2. Add one sliced red pepper, one tin of chopped tomatoes, and one pint of chicken or vegetable stock, and season to taste with salt, pepper and finely chopped herbs of your choice. I use three whole sprigs of rosemary and two whole bay leaves.

3. Now is the time to add your beans; you can either pre-cook them, as outlined in the article, or – if you intend to use a slow cooker – just add them dry.

4. Simmer on a low heat until the liquid has reduced and thickened, and test the beans with a fork to ensure that they have cooked through.

5. Serve with crusty bread, butter and cheese, or with mashed potatoes and steamed vegetables for a hearty family dinner.

What: Fresh plant cuttings and ‘weed’ leaves.

Application: Mix with leafmould or compost and apply in small quantities around individual plants.

Benefits: Helps retain moisture. Comfrey and nettle also add nutrients, and prickly exterior can be offputting for slugs and snails.

Troubleshooting: Don’t add weed flowers, seed pods or roots, as these can propagate.

What: Dried stems left after wheat or oat harvesting. Application: Place in an 8-10cm layer around plants and between rows. Avoid plant crowns.

Benefits: Retains moisture, keeps fruit clean and stops fungal diseases spread by rain.

Troubleshooting: Source locally from organic suppliers to avoid weedkillers. Check for slugs regularly. Straw may rob the soil of nitrogen if dug in, so ensure it remains on the surface.

What: Leaves from trees and shrubs. Application: Leave to rot down for one to two years to destroy diseases.

Benefits: Vital food for complex soil life, builds structure, retains moisture, smothers weeds.

Troubleshooting: Always source locally, avoiding woodlands and road verges.

4 5

What: Rotted kitchen and garden waste, tea leaves, egg and cereal boxes, woody prunings.

Application: Layer across the soil as a mulch. Mix with sand, grit and topsoil or leafmould for potting mixes.

Benefits: Improves soil structure, moisture, and adds nutrients.

Troubleshooting: Best applied in the spring, when the soil is warmer and before growth starts.

What: Quick-growing plants, such as grazing rye, phacelia and crimson clover.

Application: Use as a ‘catch crop’ wherever there’s bare ground. Dig in four weeks before sowing in spring.

Benefits: Improves soil structure, aids drainage, suppresses weeds and, if left to flower, attracts beneficial insects. Can improve soil fertility under right conditions.

Troubleshooting: Try to dig in before flowering, as stems can toughen, making it harder to incorporate.

6

What: Straw-based manure from farm animals.

Application: Rot down for at least six months to destroy pathogens and weed seeds, then apply liberally.

Benefits: Adds nutrients, improves structure, aeration, moisture levels and drainage.

Troubleshooting: Always source carefully from an organic farm to ensure it’s free of herbicide residues or growth hormones.

7

What: Liquid feed made from plant leaves, such as comfrey or nettle, or from hot bin or wormery juice.

Application: Best for containers or greenhouse beds.

Benefits: Adds NPK nutrients in a more readily available form than composts.

Troubleshooting: Always dilute until the colour of weak tea.

For more advice on managing your soil, head to gardenorganic.org.uk/soilhealth-booklet to download our guide to soil health.

Something puzzling you? Drop us a line and our experts will try to help...

Q One of my apple trees has produced a huge number of small apples. How can I prevent this happening next year?

A. Nathan, Shropshire

A The answer is to start thinning out the young fruits in late May. As a general rule, on a young tree you should leave one fruit for every 10cm/4in of branch length. Once the tree is more than six years old, you can leave a few more.

You may have to remove far more fruits than you leave on the plant, which can be, psychologically, a difficult thing to do as it seems so wasteful. Start by taking out fruit that will rub into branches as they grow, any malformed fruits and those with signs of disease. You may have to go over the tree several times to achieve the correct level of thinning.

Thinning the crop will give you much better sized fruits, and remove the risk of branches breaking because they can’t bear the weight of the crop.

Q I’d like to grow potatoes within a no-dig system. How would you recommend I do it? Via Facebook

A To grow potatoes without digging you will need a supply of old straw to mulch the growing plants. Apply rotted manure or compost to the soil surface at your usual rate, then lay out the tubers on the surface at your normal spacing. Some people prefer to plant the tubers in a shallow hole. Cover with a layer of straw, and add to this as the potatoes grow. You may have to help the shoots make their way through the straw. Once the plants have nearly met between the rows, top up the mulch with grass mowings. This helps exclude light.

We’ve found that potatoes grown this way can be more frost prone as the straw acts as a barrier to the soil’s ability to absorb heat during the day, keeping it warmer over night – so a slightly later planting can be advisable in frosty areas. No weed control or earthing up should be needed. Harvest is simple – just pull back the straw and remove the tubers as needed.

Q Could you please tell me whether shrubs are good for the environment in the same way as trees and if not why not?

J. Whiffen, Surrey

A A large tree will absorb and lock up more carbon than a shrub, but shrubs still have a carbon capture benefit, particularly longer-lived, vigorous species. It has been calculated that a medium-sized shrub can store up to 50kg of carbon during its lifetime, while a large, long-lived species, such as rhododendron, could adsorb as much as 500kg.

A (rather limited) study of Mediterranean and semi-tropical plants (https://tinyurl.com/shrubscarbon) showed shrubs varied in their ability to store carbon. Rosemary and loquat were particularly effective, absorbing up to 50% of their total weight in carbon. Another benefit, particularly of shinyleaved evergreen species, is their capacity to collect slightly larger carbon particulates on their leaves that are washed off with the rain into the soil. This includes ivy, Portuguese laurel and ceanothus (pictured).

Q About a week ago, I cleared out a completely overgrown pond and removed all the plants. The water is now very brown and muddy and so far shows no sign of clearing. Is there anything I can do to speed it up? I have a bucket full of oxygenators ready to go in. Will these help, or should I wait until the water clears?

G. Crane, Somerset

A The pond water is likely to look brown and muddy for a while after you’ve stirred up the depths, but this should gradually settle. Provided you have removed much of the old, decayed plant matter from the bottom, it should be fine to add the oxygenating plants before it clears.

Q My polytunnel tomato plants developed late blight. I’ve been able to ripen some of the tomatoes. Is it safe/wise to save seed from them? And should I treat the soil in the polytunnel with anything before replanting?

B. Dyson, Shropshire

A The answer to both questions is no! As a general rule, never save seed from a diseased plant. If you must, (for example, if it’s an usual variety not easily available), grow plants from this seed away from other members of the tomato family and be alert for signs of infection. Don’t share the seed with others. There is nothing you could treat the soil with, and there is no need to do this. Simply clear away all tomato plant and fruit debris. It’s advisable to use a crop rotation, even in a polytunnel, to avoid the build-up of soil-borne tomato diseases.

Q Some years, white/light brown patches suddenly appear on the leaves of our healthy-looking leeks in the autumn. These patches grow bigger and we lose a lot of the leaves. What is this please, and how can we stop it? We are organic and use a three to four-year rotation.

A. Williams, Gwynedd (sent in October 2023)

A Your leeks are suffering from the disease White Tip, caused by the oomycete organism Phytophthoraporri. This is spread from resting spores carried in soil or by wind and rain.

Spread can be explosive in the right conditions and 50% crop losses are not uncommon, particularly in wet weather. Other allium species can be impacted, including ornamental types, but as symptoms usually appear in late autumn it’s mainly leeks, overwintering onions and garlic that are affected.

Trimming, bagging and binning the worst affected foliage may prevent further spread if the weather stays dry. The alternative is simply to harvest and freeze the leeks that you have. It could also be worth growing early leek varieties that produce more of a crop before the disease arrives. After harvest, remove all leek debris and destroy or dispose of it via the council green waste service. Don’t compost it. Covering the soil with either a mulch or green manure may help prevent spread to other allium plants in the garden. Resting spores can live for at least three years in the soil, so it would be wise to continue to use a rotation of at least four years.

Head Gardener at Garden Organic

“It’s a constant balance in an organic space between pests and predators. You try to limit your interference... while marvelling at nature’s beauty and ingenuity”

Sponsored by Viridian. Since 1999, Viridian Nutrition has been creating the purest, kindest health supplements, always with a healthy attitude. Our ethical formulas are fully considered from the seed to the recycling bank and crafted by expert nutritionists using clinically evidenced research. We #digdeeper to ensure every ingredient is sourced with 100% care so it can make a lasting difference for you, for charities and for the planet. Viridian supplements are free of excipients, never use GMOs or palm oil and are not animal tested at any stage. Available and recommended at independent health stores, find your nearest at viridian-nutrition.com

Emma O’Neill shares her experience of companion planting with flowers before vegetables, and how we’re testing out no-dig methods

Every year in our organic demonstration garden at Ryton, we’re looking for new methods to increase our biodiversity, experiment with new organic developments, keep our soil tip-top – and generally have a forward-thinking, innovative space that inspires our members and visitors.

It’s a constant balance in an organic space between pests and predators. You try to limit your interference to allow nature to do its thing, while marvelling at its beauty and ingenuity. However, we’re always looking for ways to give nature a helping hand where we can, and in the past year we’ve decided to try out companion planting in a slightly different format.

Like many gardeners, we often have empty spots, which we fill with flowers or herbs – but this year we planned our potager around the flowers instead of the produce. Every bed had rows of flowers sown and planted prior to the vegetables.

Flowers were chosen based on three criteria; their ability to attract predators and pollinators; their size and shape (you don’t want flowers that will out-compete or shade the produce); and how good they look.

We opted for nigella, calendula, marigolds and snapdragons at various heights, all with single flowers that are more accessible to pollinators.

The results were impressive. The calendula supported the chickpeas allowing them to scramble through the flowers, and encouraged plenty of pollinators. There were fewer pests on the crops, thanks to plenty of predators visiting the garden.

The exception to this was our broad beans. We planted these early without planting companion flowers first and as a result they suffered an abundance of blackfly before any ladybirds were around. Although the ladybirds and other predators did eventually arrive, the blackfly had already done its worst. Next year, we’ll plant out the beans later and ensure flowers are in place first.

The negatives to planting out your flowers first is that they have more time

Lablab flowers, below

Companion planting creates a diverse environment in your vegetable patch. Here are some combinations to try…

to grow and are therefore larger than the vegetable initially so you must be careful they don’t swamp them or colonise space you’ve reserved for vegetables. Overall though, I feel this type of planting has benefited the garden and our beneficial friends, as well as looking great!

Soil testing on our dig and no-dig beds continues. The tests are looking at a number of different elements, including pH levels, soil structure, microorganisms and nematode presence. We’re also keeping records of germination rates, growth, pest attacks and yield.

These tests will be taken over four years to ensure that each crop family has gone through its rotation. As soon as we have all four years’ data, we’ll interpret and share the findings.

If you’re lucky enough to be a Heritage Seed Library member and get your free seeds each year, you’ll know the beauty of growing

these varieties. We’re in a privileged position here at Garden Organic HQ as we can select from a wider range of heritage seeds.

Among the varieties that have stood out this year are lettuce ‘Mescher’, which is excellent at colder temperatures and easy to grow from seed, and greenhousegrown lablab bean ‘Vasu’s 30-Day Dwarf Papri’, with its abundance of pretty white flowers. Kale ‘Ragged Jack’ has attractive leaves, and can be harvested in cold temperatures.

These three varieties would definitely be my recommendations from this year’s list, due out in December.

I’m off to plan our garden for next year taking into account the successes and failures of 2024.

We’ll be planting more flowers and looking at how to increase yields in the potager if next year’s weather is as unpredictable as this one.

I hope you have some time to reflect on your garden and remember to celebrate your wins and learn from your failures.

1. Calendula and cabbage. Insects such as hoverflies and ladybirds will be attracted to the flowers and act as predators to the brassica-loving cabbage white caterpillar.

2. Nasturtiums and beans. Juicy nasturtium leaves and their brightly coloured flowers pull blackfly away from your beans, and once there they will tend to stay on the host plant.

3. Marigolds and tomatoes. Plant orange/yellow marigolds in greenhouse beds to attract whiteflies away from the tomato plants. It’s not the smell that confuses the pests, but they’re attracted to the colourful petals.

4. Lettuce and sweetcorn. Divert slugs to a sacrificial row of salad between your corn cobs so they munch on that rather than your prized crops.

5. Crimson clover and fruit trees. Grow strips of clover between fruit trees or bushes. If mown regularly, the cuttings can be thrown under the bushes, where the nitrogenrich leaves break down quickly to supply nutrients to the trees.

We love to hear from you. Send an email to editor@gardenorganic.org.uk or write to The Editor, Garden Organic, Ryton Gardens, Wolston Lane, Coventry, CV8 3LG

Gardeners from across the UK share their triumphs, tips and gardening memories

I have been a lifelong organic gardener and a member for decades. We used to visit HDRA at Bocking, probably in the late 70s, and were lucky enough to be shown around by Lawrence personally. Lawrence came to stay with us when I was an organic smallholder in Norfolk. At the time he was hoping to write a book about smallholding and we had a very mixed, almost self-sufficient holding. Cherry phoned me to make sure that he would get the right diet.

I have a lasting memory of seeing Cherry and Lawrence, hand-in-hand at a Norfolk festival where we were selling homegrown and milled flour. It was always a joy to see them, and he has been an inspiration ever since I found Grow Your Own Fruit and Vegetables in 1971. He was a true visionary, and Ryton has been wonderful.

C. Butler, Gloucestershire

Pauline Pears’ article in Issue 237 invites responses on the topic of old garden tools. I have a small group of basic tools (fork, rake, hoe) inherited from my great uncle Jimmie, who we think in turn had taken ownership of at least one of them from his father, a market gardener. They are therefore probably all more than 70-years-old, possibly nearer 100.

Jimmie was a gardener on a local estate here in north-east Scotland for around 40 years, from just after the war until his retirement. I’m also a gardener, working for a company that is more than 200-years-old. When I use these old tools and at work in the garden I love the sense of simply being the custodian for the time being. The connection to traditions, techniques and people across the decades and centuries is reassuringly humbling.

S. Cooper, Moray

There was a letter in the spring 2024 issue of The Organic Way, from R. Bryant-Jefferies, suggesting that primary schools should make gardening a feature of their learning. In my local area they all do, although gardening club is an extra-curricular activity for those who are interested.

I have found great joy in being a volunteer helper at my local school and would encourage organic gardeners to consider this role for themselves. Most schools want help with this sort of thing.

D. Martin, East Sussex

I have just read the article ‘Charging Ahead’ in the summer 2024 issue of The Organic Way, and while I found it balanced and well considered overall, I would point out one thing worth bearing in mind. The lifetime of the batteries and chargers might be 10 years with luck, but manufacturers tend to change these items within ranges more frequently. This can leave you with problems of obsolescence, not something machinery with a lifetime of 20+ years and the ubiquity of petrol would encounter. Having said that I remain a convert to the quieter, cleaner and more convenient way of working.

P. Jones, Gloucestershire

This statement in the article Charging Ahead about battery powered tools is misleading: ‘Battery tools produce no emissions’. They may produce no emissions in use, but there is a huge amount of embodied carbon in their manufacture: the sourcing, mining, processing, manufacturing and transporting of the materials.

There will also be emissions produced from the charging of the batteries, unless users have access to entirely renewably sourced electricity.

Nor does the article mention other environmental impacts of ‘switching from petrol to battery’; what is to be done with the redundant machines? How are they to be disposed of or their components recycled?

Encouraging gardeners – or anyone! – to buy more stuff doesn’t sit comfortably with the ethos of organic care for land and crops. There is no mention of the slow skilled labour involved in using hand tools: shears, secateurs, scythes.

L. Potts, Yorkshire

GO Response: To help address some of these concerns, Ian has done a little more research…

• For tools with as long a lifetime as possible, always choose reputable manufacturers, and particularly those who are able to control the quality of their batteries. Some of the major companies manufacture their own batteries and therefore have full control. Stiga’s 48v batteries, for example, maintain 80% of their original capacity after 750 charge cycles. If a battery were to be fully discharged and recharged once a week for 40 weeks of the year, it would still retain 80% capacity after 18 years. Stiga dealers analyse battery health as part of the service process. It’s therefore entirely possible for a battery-powered machine to match the longevity of a petrol equivalent.

• In terms of disposing or recycling old petrol tools, this will vary depending on location. The Recycle Now website can help you find the best solution for each specific item –visit recyclenow.com/recycle-an-item.

• With battery-powered tools, the larger companies may recycle key components. Stiga batteries, for example, can be returned to the supplier at end of life for correct recycling and disposal. Where possible, they reuse components in the manufacture of new batteries. Their larger batteries can be tested to identify faulty cells, which can be replaced rather than disposing of the entire battery. Tools powered by elbow grease will always be the most sustainable ones to use, but if you do need to invest in a new powered tool, hopefully this will help you make the best choice for your circumstances.

I share your correspondent H. Bishop’s memories of a graveyard of insects on the front and windscreen of a car, after a trip into the country during the 50s and 60s (summer 2024 issue). I had wondered if the aerodynamic design of modern vehicles was partly responsible for cleaner cars in recent decades.

But in late May, our car travelled from Telford to Shrewsbury and back, coming home with a splendid collection of deceased insects. This same journey has been made countless times over the last 20 years, at different times of day and year, with no such result ensuing. What changed?

We wondered if it was the result of progressive rewilding; leaving verges uncut; and a more sympathetic approach to nature in our gardens. As organic gardeners, we have noticed an increase in very recent years in the number and variation of insect species among our plants. Is the tide turning?

J. Sinclair, Shropshire

Research manager

“Many collective gardens have important social and therapeutic functions, so efficient food production may not be a priority”

Dr Anton Rosenfeld delves beyond the headlines to unpick the analysis of urban and conventional agriculture’s carbon footprints

Arecent paper in the journal Nature Cities1 created a bit of a stir with its headline that the Greenhouse Gas emissions (GHG) produced by growing a portion of fruit and vegetables in small scale urban horticulture are six times that of conventional horticulture.

This has led to incredulity in some circles: for many, urban horticulture and city gardens represent an alternative model for small-scale local food production that rallies against our ‘industrial farming methods’ – so surely it must score better.

However, when you examine the article further, you find the authors are actually very supportive of urban horticulture and the paper provides a lot of helpful practical advice on how small-scale urban gardens can reduce their carbon footprint. They highlight how short-lived infrastructure can massively bump up the greenhouse gas emissions from food production. They also acknowledge the many other benefits from urban agriculture that should be considered.

Evaluating the carbon footprint of anything is complex, but it becomes especially difficult when you try to compare very different ways of

producing food. This study collected data from 250 conventional farms and 73 urban horticultural sites in the US, France, Germany, Poland and the UK. The urban horticulture group was divided into three further categories of seven urban farms, nine collective gardens, 55 private gardens and two others. The researchers recorded the inputs and infrastructure and kept a diary of yields, then calculated the GHG that could be apportioned to a standard serving of fruit and vegetables from each of these methods of food production.

Although the overall finding was that urban horticulture produced six times the GHG of horticulture per serving, we need to delve a bit deeper to find out what this really means.

To start with, collective gardens may have other priorities beyond efficient food production. The collective gardens had a very high GHG per serving, almost 10 times that of conventional horticulture, which would have skewed the overall urban horticulture results.

But we must bear in mind, that many collective gardens have important social and therapeutic functions, so efficient food production may

not be a priority. If these gardens are producing low yields, then the number of resources used and therefore the GHG per serving of food produced will be disproportionately high. (Note that when apportioning resources, they took account of the area of the garden devoted to food growing.)

The biggest culprit contributing to the high GHG emissions of urban horticulture was all the energy used to create the infrastructure. On average this contributed to 63% of the GHG emissions. The insecure tenure of many urban sites and short-lived nature of project funding increases the risk of infrastructure only being used for a brief period of time.

The urban farms showed up much more favourably in this analysis. Once one outlier (with a very high GHG output) was removed from the urban farm dataset, the GHG output per serving was almost identical to that of conventional farms.

Urban farms are often run as small businesses prioritising efficient food production, so the resources used per amount of food compares favourably. Other studies have also highlighted the potential for high productivity of urban farms.2

The study presented the GHGs for a number of different crops. The variability in GHGs per kg of vegetable produced was extremely wide between sites. This may have been a reflection of the difficulty in accurately estimating yields from small plots. Some crops such as tomatoes grown in low-

tech facilities at urban farm sites produced less GHG than those grown in heated glasshouses in commercial horticulture.

• Food security

In the UK, we import around half of our vegetables and 85% of our fruit4 and we have long, complex supply chains that are very vulnerable to being disrupted by unexpected events. Direct food supplies from urban farms and other alternative schemes have an important role in food security and food sovereignty5. This was demonstrated in the Covid pandemic in 2020 where food sales from some vegetable box schemes rose by 111%6.

• Social benefits

Urban horticulture also provides

many social and therapeutic benefits to society7, including reducing social isolation, providing access to green spaces and improving community cohesion. These benefits can be far-reaching but difficult to quantify. This is acknowledged in the study.

• Diet

It’s been shown that people participating at urban horticulture sites often change their diet to eat more fruit and vegetables and less meat, which reduced the GHG impact of their diet by 12%8.

• Biodiversity

The study doesn’t mention the impact on biodiversity, but this is an important component. Urban horticulture sites often have diverse planting providing valuable habitats and nature corridors in cities9. This is likely to compare more favourably than the intensively

managed monoculture of conventional horticulture.

• Soil health

In this study, urban horticulture used 95% fewer synthetic inputs than conventional horticulture. Additionally, there are studies showing that the health of soils in urban horticulture is often better than that of nearby equivalent conventionally farmed soils, having better soil structure and storing more soil organic carbon10.

In an era when we tend to just look at headlines then scroll onto the next item – it’s easy to think this study must be on a mission to attack urban horticulture. In fact, it has provided useful guidance as to where urban food producers can reduce their environmental impact.

It’s also not the only study to highlight that small scale horticulture

TIP 1: Make sure your infrastructure gets good use for a long time. For example, a raised bed used for just five years will have four times the environmental impact of one that lasts 20 years. Question whether raised beds are really necessary, and if so try and choose a more durable wood such as cedar or use recycled materials (see below).

TIP 2: Use upcycled materials (e.g. hazel poles rather than bought canes). Farms that used recycled wood for their raised beds managed to reduce their emissions by 52%.

TIP 3: Composting is integral to many urban sites and can have a positive impact. It reuses waste materials and reduces the need for synthetic nutrients, but it comes with risks. The embedded energy in making plastic bins is significant and there’s also the danger that small scale piles containing a high proportion of wet, green materials can turn anaerobic resulting in high methane emissions3. Use upcycled materials to build composting infrastructure and consider larger scale community composting with a plan to turn and aerate it properly.

TIP 4: Water use can also have a significant impact especially if a large proportion of mains drinking water is used. At a few sites, it contributed to more than 50% of the carbon footprint. Use collected water where possible and add plenty of compost to the soil to build up its capacity to retain water. Grow more deep-rooted perennial crops that make better use of water.

TIP 5: Crops grown at urban sites such as beans, sugar snap peas and berry fruits will compare favourably to their air-freighted equivalents so would make a good choice if you wanted to reduce your GHG emissions.

can use disproportionate amounts of resources for the food it produces, if not managed carefully2.

It’s useful to treat these articles as warnings not to be complacent.

We must not assume that just because urban food production is small, local and friendly, it has a smaller impact than larger scale horticulture.

However, as with any growing space, resources need judicious management. The good news is this

can be easily achieved by adopting the many sustainable practices that any good organic grower would use.

1. Hawes, J. K. et al. Comparing the carbon footprints of urban and conventional agriculture. Nat. Cities 1, 164–173 (2024).

For further references please go to www.gardenorganic.org.uk/ news/urban-agriculture

Josiah Meldrum, is the part owner of Hodmedods, founded in 2012 with a mission to get UK farmers passionate about growing beans and pulses. Josiah chatted to our head of horticulture Chris Collins about our changing attitudes towards these plants and how Hodmedods is encouraging farmers to take an organic, sustainable approach

Chris Collins (CC): From where did the name Hodmedods come?

Josiah Meldrum (JM): It’s an East Anglian dialect name, meaning snail or hedgehog. When we started thinking about some of the crops that are disappearing in the UK, we thought it would be nice to pick a name or a word that’s also disappearing. A lot of our dialect words are drifting away.

CC: What got you interested in this type of business and how did it all start?

JM: A couple of friends and I were working for a small nongovernmental organisation in East Anglia, looking at food systems and how we might engage more directly with the way our food is produced, and improve how our food is grown.

We did some work with a community group in Norwich who asked a really interesting question in 2008: could a city the size of Norwich feed itself? And if it did, how would we have to change?

We came to the conclusion that Norwich could feed itself from a relatively small area – but that we would definitely need to change our diets. We would need to grow more leguminous crops and eat more plant-based protein and less meat because of the nature of extensive and intensive agriculture. One of the issues is that we don’t like beans in the

UK – we’ve lost our appetite for plant food, basically. When you look around the rest of the world – the Mediterranean, Mexico – they love beans. The only bean that we eat in any volume is baked beans – we eat more baked beans than anyone else in the world per head.

CC: You do a lot of work with farmers. What does that involve?

JM: That began very early on. The realisation that pulses are this incredible engine for change led us to see that if we were to engage directly with farmers and ask them to grow particular varieties, we could use that to help them change their rotation to bring broadly a kind of ecological value to the farm, but also a better economic return. The things that we’re really good at growing here are peas, dry peas, and fava beans. Yet when we started, there was nobody growing them, because the imports were just £10 - £20 a ton cheaper and that is enough to flip it from it being worth doing to not worth doing due to the extra attention and care required. Producing for animal feed is much easier. So by working directly with farmers – we have a group of about 35 - we’re able to ask them to grow in particular ways, and particular varieties.

Quite a lot of the farmers are organic, but we’re really interested in farmers who want to make a change broadly. Some of the farmers have converted to organic through the process of working with us and we demonstrate to them what the benefits and the advantages of that are, which is quite a powerful thing. We could have just worked with organic farmers right from the start, but that would have really limited our opportunities to support change.

CC: So have you got some interesting varieties of peas that you grow?

JM: Yes. Peas are amazing. Our climate means they are almost 100% self-fertile. They pollinate themselves before their flowers are fully opened. The advantage of that is that you can grow lots of varieties next to each other without concerns about them cross-pollinating. From a breeding perspective, they’re quite stable in the field, so it’s easy to do. At any given time, we might have anywhere between seven and 10 different varieties of pea in the bean store ready to go out.

CC: Have you got any tips for growers?