CELLAR DOOR 20222023

Cellar Door is the oldest undergraduate literary journal at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The magazine has continually published the best poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and art of the undergraduate student body since 1973. It welcomes submissions from all currently enrolled undergraduate students at UNC.

To the Creative Writing Program and Department of English and Comparative Literature, for their ongoing support of student writers, editors, and readers.

To Bland Simpson, for his benevolent support of Cellar Door and other undergraduate literary causes.

To Michael McFee for his decades of dedication to Cellar Door, including distribution of copies to the campus racks and storage of boxes in his office.

To the artists and writers who create every day, for letting us share their work with the rest of campus and beyond.

Some of you might read this in the hush of Davis Library’s eighth floor or the din of the second. You might walk through these pages as you walk across the quad; or maybe your toes will curl into a soft blanket as you sit on your couch. Regardless of where you are, I ask that you pause and inhale, feel your ribs expand. Exhale, feel your lungs relax.

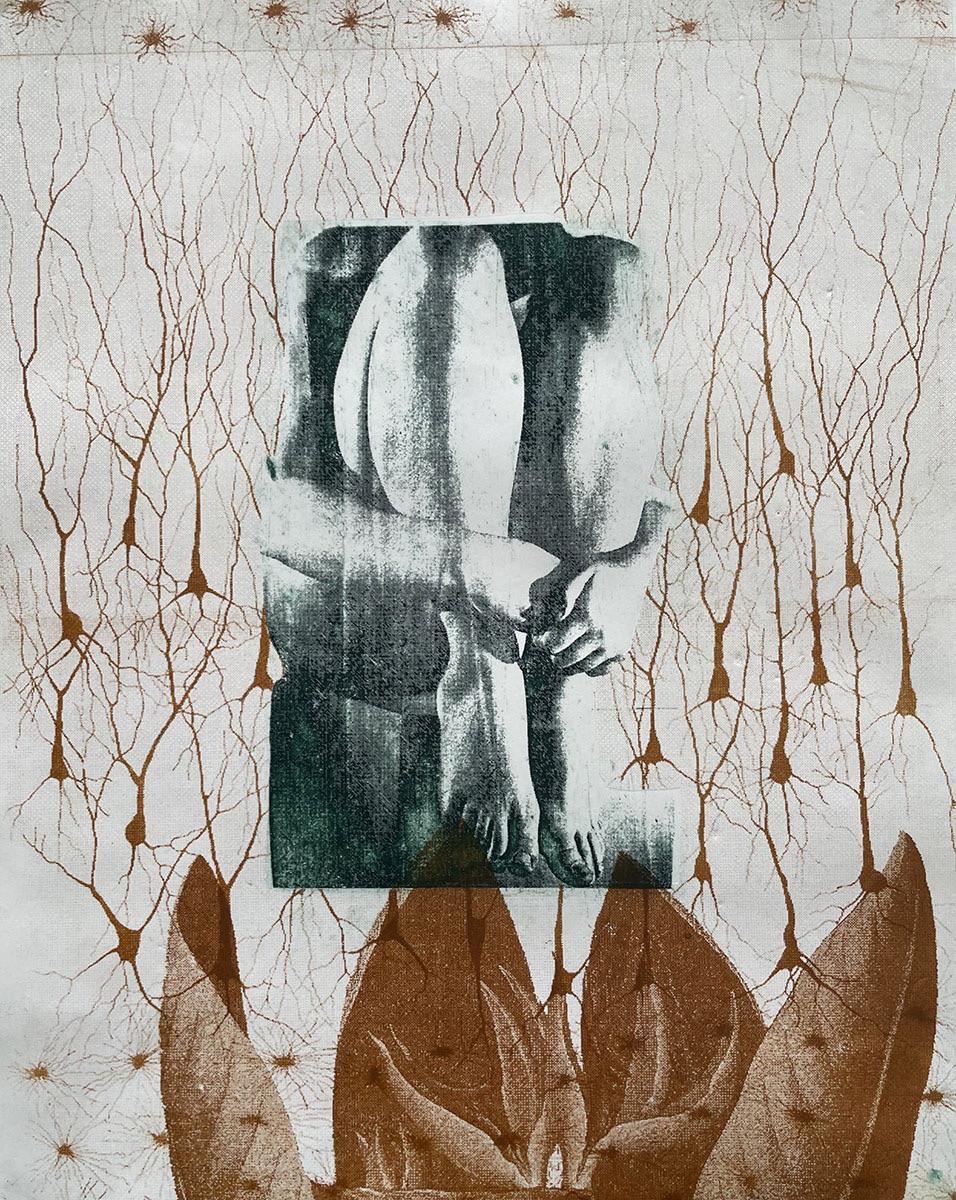

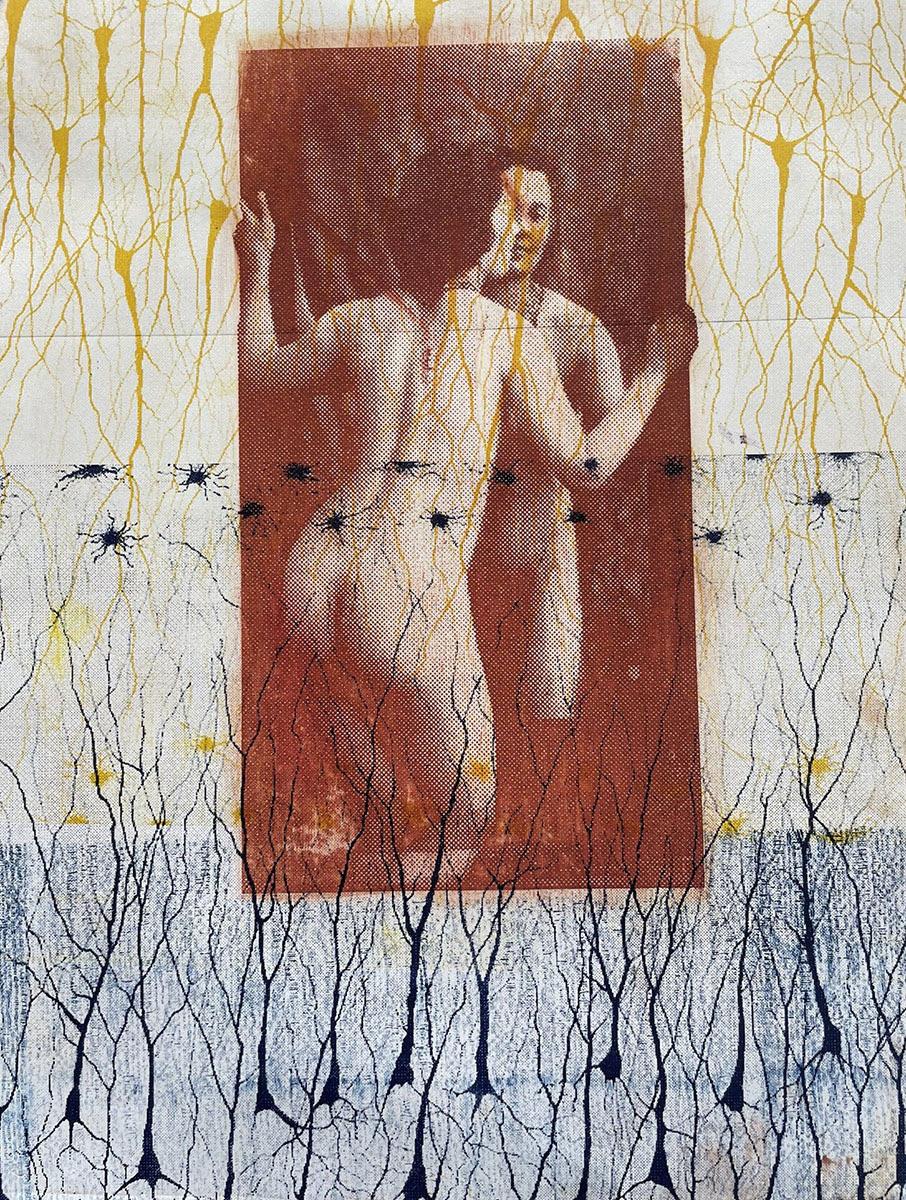

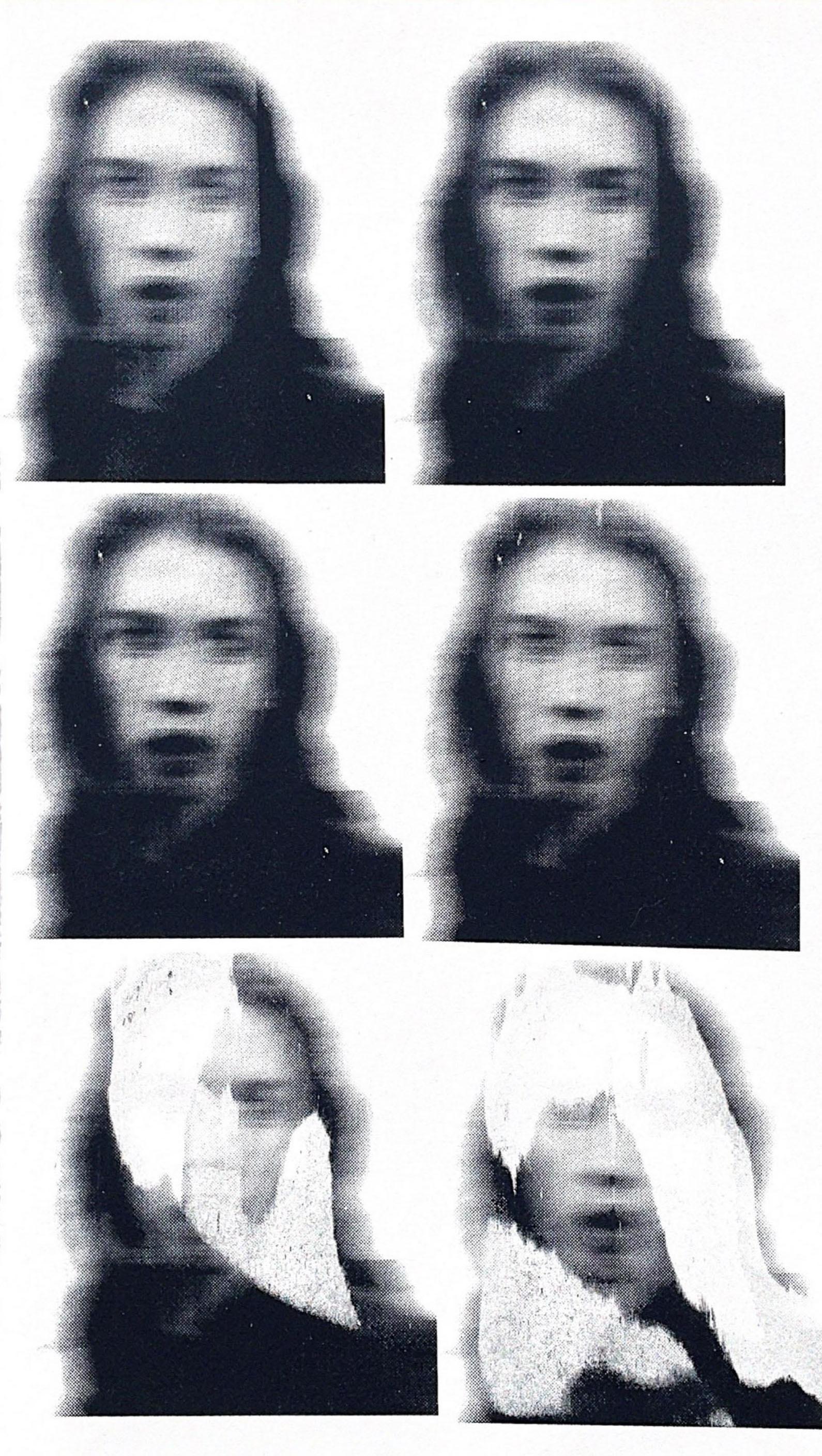

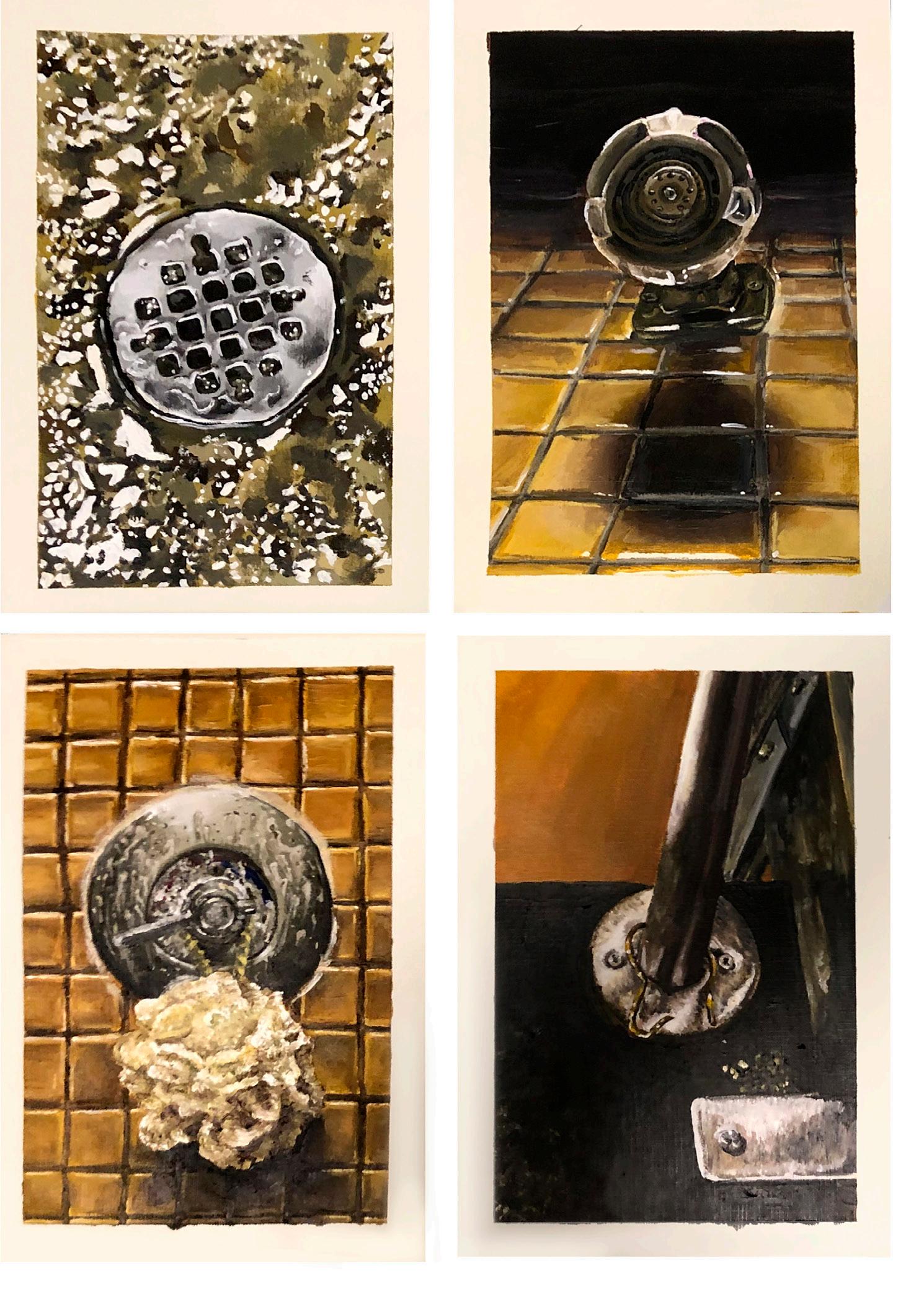

This edition of Cellar Door centers around the corporeal. Within these pages, writing and art capture lived experiences through bodies, pulling the space between our tangible realities and intangible emotions into focus. These poems, stories, personal narratives, and visual media remind us that we are the paint and canvas, pen and ink through which we interact with the world. We confront injustices, grow trepidatiously, love deeply, shout exuberantly, and pour those interactions into creative acts. In essence, writing and art are extensions of ourselves; our souls and emotions, but also our fingertips and footsteps.

While we can only choose a few select pieces to print in the magazine, I hope this edition reminds you that you are growing, experiencing, and creating just by taking a breath.

I am grateful to all the artists who took a risk and allowed their voices to grow by sharing their work with us.

Likewise, I am grateful to all the members of Cellar Door. This year, the magazine also expanded, splitting our prose section into fiction and nonfiction sections, creating publicity, website, and design editor positions, and hiring more staff. The success of this issue hinges on collaboration, brainstorming sessions, and various moments of poking my head out of my room to ask our treasurer (and my roommate) random questions about last minute details that escaped me. To Zoe, Lucy, Jane, Anistyn, Isabella, Meredith, Hope, and Xenia, to all of our staff readers, and to our wonderful adviser, Michael McFee, thank you. Cellar Door would not exist without your dedication to sharing the voices of UNC’s students with the Chapel Hill community.

To our contributors: thank you for reminding us that to create, we must first exist.

Best,

Abigail Welch, Editor-in-Chief

FIRST PLACE Alice MARCELLA KINGMAN

SECOND PLACE Mother, Maiden, Crone ALEXANDRIA ANDERSON

THIRD PLACE Silent KATHERINE VERM

FIRST PLACE Raw and Red BROOKE ELLIOTT

SECOND PLACE The Thing About the Box ISABELLA UKARIWO

THIRD PLACE Peach Trees EMMA GERDEN

FIRST PLACE Grandma Asks, “Are You Still Praying to Your Jesus?” BOATEMAA AGYEMAN-MENSAH

SECOND PLACE Celestial Haibun BOATEMAA AGYEMAN-MENSAH

THIRD PLACE CAROUSEL CECIL MAY

FIRST PLACE Half Life RUTH JEFFERS

SECOND PLACE Copper ALEXIS DUMAIN

THIRD PLACE Exhale MOLLY HERRING

Rachel Campbell is originally from Christchurch, New Zealand. She has lived in the USA since 2003. She went to the Otago School of Art in Dunedin, New Zealand and the Central School of Art in Toronto, Canada. Rachel has lived and exhibited in the United Kingdom, Germany, and New Zealand, as well as in the USA. She has received numerous awards and fellowships including the Emerging Artist Grant for Durham in 2013 and 2022, Southern Arts Grant in the UK, and fellowships at the Vermont Studio Center, VCCA, and the Key West Artist Residency. Most recently she was in New American Paintings South Edition #160 2022. Her work is in public and private collections in many countries, including Duke University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Fidelity Investments, and UNC Rex Hospital. Rachel is like a visual poet who writes about the everyday, but she is expressing her experience of life in paint. She frequently explores the urban landscapes of the American South and of her homeland, New Zealand. Her images also invariably presuppose narratives. These often then combine to evoke the sense of belonging that we all long for no matter what our particular environment might be.

Jacqui Castle is an educator and novelist living and writing in the Blue Ridge Mountains near Asheville, North Carolina. Castle has been published in a variety of publications including Mountain Xpress, WNC Woman, Asheville Grit, and Explore Asheville. Her novel The Seclusion, which School Library Journal called “a must-have for all libraries and fans of sci-fi,” garnered Castle the title of 2020 Indie Author of the Year through the Indie Author Project (a collaboration between Library Journal and Biblioboard). Castle currently teaches creative writing through the Great Smokies Writing Program. When not writing, Jacqui can be found hanging out with her family and consuming far too much caffeine.

Originally from Albuquerque, New Mexico, Olivia Gatwood has received international recognition for her poetry, writing workshops, and work as a Title IX Compliant educator in sexual assault prevention and recovery. Olivia’s performances have been featured on HBO, Huffington Post, MTV, VH1, and BBC among others. Her poems have appeared in Sundance Film Festival , Lambda Literary, The Missouri Review, and on The Poetry Foundation website, among others. She is the author of two poetry collections, NEW AMERICAN BEST FRIEND and LIFE OF THE PARTY. She is the co-writer of the film THE GOVERNESSES alongside director Joe Talbot. Her debut novel, WHOEVER YOU ARE, HONEY, will be released in 2023.

Jaki Shelton Green is the first African American and third woman to be appointed as the North Carolina Poet Laureate. When he appointed her in 2018, Governor Cooper stated that “Jaki Shelton Green brings a deep appreciation of our state’s diverse communities to her role as an ambassador of North Carolina literature. Jaki’s appointment is a wonderful new chapter in North Carolina’s rich literary history.”

ABIGAIL WELCH

ART EDITOR

HOPE MUTTER

FICTION EDITOR

XENIA WEAKLY

PUBLICITY EDITOR

ANISTYN GRANT

nonFICTION EDITOR

MEREDITH WHITLEY

POETRY EDITOR, Treasurer

ZOE NICHOLS

WEBSITE editor

ISABELLA REILLY

DESIGN editors

JANE DURDEN

LUCY SMITHWICK

JAQUELINE ARI

CHARLOTTE BRECKENRIDGE

ISABELLA GAMEZ

LIZZIE HERRING

ALICE HUFFSTETLER

ESMÉ KERR

GEORGIA PHILLIPS

MADI SPEYER

LILLI TREPPEL

LUNA HOU

EMMA NELSON

ASHLEY MCGUIRE

ANNA MARIE SWITZER

CIARA RENAUD

JESSICA HOFFMAN

MACON PORTERFIELD

SA’TIA BROWN

ELISABETH JORDAN

CARLY BARELLO

NEHA JONNALAGEDDA

KASEY PRICE

PAULINA LOPEZ

JESSICA JONES

RYAN PHILLIPS

RIO JANISCH

DELANEY PHELPS

GEORGIA CHAPMAN

EMMA KAPLON

VIVIAN WORKMAN

ANNA VU

AMELIA LOEFFLER

ADAM TATUM

MICHAEL MCFEE

Today, Arthur operates a merry-go-round in an amusement park. Sheltered from sun by rusted booth and polyester vest, rain too hot for any relief. He is no king, though in his presence children raise their fists and exclaim in delight. Ceaseless, again he doles out the worn reins of whimsy, guides feet into stirrups. He pulls the lever Excalibur, and a legion of horses storm forward under his command,

their painted faces struck still mid battle cry. They will never fear death, but there is no peace in their petrified wood. Arthur no longer fears death, but even so, his hands shake. He lights a cigarette, unseeing eyes of the cavalry his only witness. Breathes in again. Around him, serpents coil through the air suspended on metal legs, and just as the olden days, they strike screams of terror and joy across the sky. Now Arthur sits on break, hidden behind a concrete anchor that binds serpent to earth

when it twists: metal screaming as the tracks pull backwards like a curl of ribbon. One of the great dragons bows its head towards him, and with a mouth made of train carts, it says: Stand, my lord. Today, and tomorrow again, we find reasons to keep living.

Summers have always been tragic.

“I can’t stand the thought of leaving,” said Peter, who lived on a farm at the edge of town.

We loved his property—the long, looping grapevines. The daffodils that grew around his mailbox. The peach trees, and beyond them, the pond, where we used to catch frogs when we were little.

Kristen skipped a stone, and we all watched it sink. Her bare toes squished over mud, a tanned stomach exposed—she lifted her hand to cover her eyes, skin sheening with sweat, a lock of curly brown hair stuck to her forehead. She didn’t say anything. The evening cicadas chirped.

I turned to look at him, squinting in the sun. “Don’t think of that now, Peter.”

“Easy for you to say. You’re not the one leaving.”

“I am leaving. We all are.” “You’re not the one dying.” Kristen looked away.

“Peter,” I said. “Don’t say that.”

He fiddled with a wildflower, then threw it into the pond—it left a faint purple residue on his fingers. I sat down next to him, and the flower floated sadly over the murky brown.

“I’ll write to you all the time,” I said and handed him the peach I had picked. He bit into it, and the sweet, clear juice dripped down his fingertips, then his wrist.

“Me too,” said Kristen.

“I’ll send you books. All the new releases. And tapes—I can make you a mixtape. I’ll send you lots of chocolates. And I’ll cut out the cartoons from the paper.”

Peter was staring at the flower—his eyes, hazel, flashed a brilliant golden in the sun. And his profile, which I had seen so often, studied so often all throughout my youth, seemed to shimmer right before my eyes. The haziness that comes with fading memories. His long eyelashes and the faint freckles that dotted his sharp nose. It was the face of my best—and my oldest—friend.

“The war won’t even last that long,” said Kristen confidently. She sat on a rock by the water facing the two of us and stretched out her legs. “You’ll be home by December.”

“And we’ll go caroling.”

Kristen snorted. “With your perfect voice.”

“And Father John will say, ‘Peter, I’m going to have to ask you to sing a little bit quieter.’”

“Can you believe he really said that?”

“The look on his face, though. You know he felt awful.”

“Well, to be fair, we all heard that voice. Don’t you remember, Peter?”

Kristen and I watched Peter, waiting for an answer, or at least some sort of reaction—a smile. A roll of the eyes. Instead, he bit into the peach and chewed slowly, and with thought.

“Maybe we can all go camping next weekend,” he said finally. “Our last weekend together.”

“Sure!” said Kristen. “We can drive up to the mountains.”

In the fall, I would be at university, and Kristen would be working at her family’s business. And Peter would be in Vietnam, which I had only ever heard about on the news until Peter got drafted with three other boys in our graduating class; I pictured them with guns strapped to their backs, struggling under the weight of heavy machinery and supplies, slashing through the jungle. It was particularly hard to picture Peter, who once cried in the second grade when a bird flew into the window and died. And I had held his hand as we stood on the edge of the property, muttering prayers that Father John recited every Sunday under our breaths, the wind rolling over the hills and through the branches of the bare peach trees.

“We can go stargazing,” I said.

“And fishing,” said Kristen. “And I’ll bring my guitar, and I will serenade you both as you make me s’mores.”

Peter smiled, dimples curling on his cheeks. “I should be the one serenading you.”

Kristen skipped more stones, shadows deepening across her body as the sun continued to sink, then she crossed the hill to pick another peach. Peter tucked a wildflower—a yellow one this time—behind my ear, his fingers soft and damp with dew against my cheek.

“I didn’t mean it,” he said as he stared at the flower. “What I said earlier. I’m not going to die.”

“Oh, Peter,” I said. “I know that.”

“I’m just scared.”

“I know that too.”

“Will you really write?”

“All the time. I’ll write you every single day.”

Kristen came back with three peaches, and she tossed one to each of us. I leaned against Peter’s arm. And the peaches were juicy and sweet with summer-tinted nostalgia, but there was something tragic, too, in the sweetness, and then the sun went down and the cicadas cried.

Chairs

digital art

My sister boards the Trailway bus to Chicago She arrives at church just in time to purge the devil in her throat and part her lips toward heaven

When Grandma asked if I wanted to be saved too I thought I speak no tongues My sister is the translator of Twi and tradition

She makes peace with my demons by word of mouth Besides

silence is the oldest language

Fluent in the passage of breath Who else could trace their tonsils across a Bible taste the parables in the psalms of their hands and say nothing?

Ok maybe I wasn’t silent

But when I answered No

I meant I don’t have the strength to trill God is Good! in English and mean it

I meant Forgive me for my tongue is not strongest muscle in my body anymore

I swear that next time I’ll bite it into pieces Chew the pieces into blood And if she asks me to pray for the love of God I’ll swallow

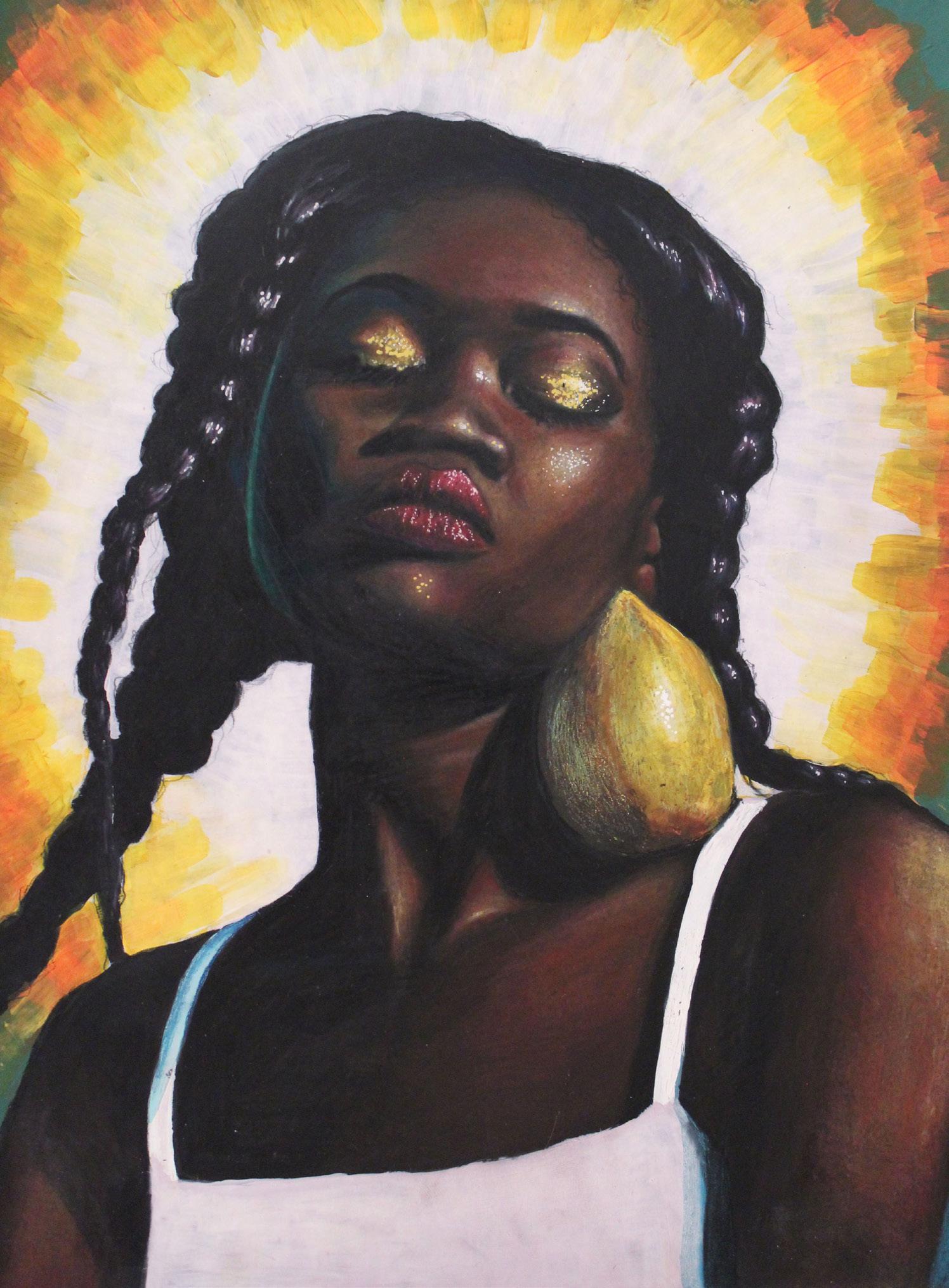

Mother, Maiden, Crone colored pencil and acrylic paint,

I remember when you would force my hair into submission, the unruly fingers of my curls snapping fine tooth combs in half as if mocking you for even trying.

I remember when you would smother my curls with coconut cream, smooth black castor oil over my scalp, rake your fingers through my coils, coax them into braids.

Once, it was your mother doing the same for you, smothering and smoothing raking and braiding.

She taught you the rhythm of our hair so you could do mine, and when her fingers failed and her mind too, you could do the same for her, hair just like mine but silver and brittle.

I wonder when your fingers will fail, when it will be my turn to smother and smooth and rake and braid the way you did hers the way you did mine.

A Distant Memory photographic film

It was your laugh that reminded me to breathe. It was your squeakgigglehushshoutlaugh and childish joy on the side of the highway in Tecpán, Guatemala while my throat closed and you dropped ripe strawberries onto the head of the giggling toddler wrapped around your leg.

Mis pantalones! you yelled as you slow-motion monster walked down the rows of black plastic suffocating the weeds around the ripe, bleeding fruit.

I was on the (flip)phone, pleading for help from our leader/teacher/29-year-old father figure/only English speaking point of contact for a million miles.

No, like, I can’t breathe, I insisted into essentially a walkie talkie, stifling a laugh as I watched you raise your arms and twist your face into a menacing growl, your skinny 6’3” shadow that much less menacing.

You sound fine to me, just wait until work is over, and we’ll check it out at lunch.

I couldn’t decide whether to laugh or cry as Isaac instructed me to hang in there, drink water, and not let you get too far.

Did you hear that Sasa? I yelled. If I start to suffocate you have to save my life, okay?

Of course! You yelled. Wait, how do I do that?

I tilted my bottle upwards and a sun-warmed bubble of filtered-ish water stretched my inflamed throat. Your giant footsteps stopped at my side, and you both looked at me from a droopy side angle, my two worried puppies.

The farmer that was responsible for us on some days for some amount of hours some parts of the week loped by with one shoulder-length rubber glove covering the skin of one arm. My jaw hit the fertile dirt as he dipped his other hand, wrist, elbow, bicep, shoulder into the vat of pesticide, turning it in great circles to mix what was undoubtedly a lethal combination of Roundup + unregistered chemicals. Whatever allergic reaction I was having seemed to be directly correlated with my distance from the black bucket of death. Even he held his breath while the concoction leapt into the air.

RAWWWRRRR, you hobbled across the field with two leeches now. The daughter of our farmer boss had materialized to torment you, latching onto your free leg and hiccuping with joy between bites of stolen strawberries. You swung them in wide arcs until all four of us were laughing so hard we couldn’t breathe.

When we started our gap year program and moved in with our host families in the highlands of Mayan Guatemala, your lack of language skills and aversion to rule following fascinated me. I choked on my laughter when you called a duck “pollo de agua” and our profesora had to leave the classroom to compose herself. That was the first time you stole the air out of the room. A few weeks into our gap year program, you’d already earned one of two possible strikes for drinking when I found you sipping a beer on a park swing. I matched the height of your arc before I asked you.

It took 84 minutes for you to breathe your story into me. I cleared the mist and tried to translate, but every duck was a pollo de agua I could only almost understand. I could picture but not smell the smoking gun out the passenger window of a van you shouldn’t have been near or that shouldn’t have been near you. I could hear but not touch the slurs yelled between gangs, open brawls at house parties that blared rap I don’t listen to. I could see but not feel the rough ridges of graffiti sprawled across government buildings in colors that meant not just red or blue but ally or enemy. I couldn’t taste the joints smoked then delt then smoked and delt then man that wasn’t yours to smoke then pop pop but they were only a cover for the sharper

I only heard it from you, the conditional parental love that would support your college education if and only if you should successfully complete our program: five countries, three host families, Salmonella and tapeworms and heat rash and malaria and attempted kidnappings and marriage proposals and an overdose and one hundred seminars and Kindle readings and hard conversations about what’s wrong with the world; is it everything? I couldn’t wait to hear the wrong with the world, an 18-year-old American Girl, I boarded plane #1 with a full heart, a full cup, a full hydroflask covered in pastel stickers. No one but the synchronized swings and the liquor tienda knew you came to us can empty.

With one eye on your second strike, I asked about the empty can in your hand. My tongue flicked self-sabotage and my heart whispered, are you okay? You looked at me with wide, sleepy eyes and waited long enough to answer that I forgot to breathe. That was the second time.

Two weeks later the rest of our farming group was sick or tired or feeling particularly crushed under the weight of the issues we studied, and you and I walked to our field alone. Our farmer handed us machetes and we pretended we were samurai’s every time he didn’t turn around. A few miles later they drooped by our sides with our heads, hung low as our voices in the six-somethingA.M. mist.

We talked about the group, the other twelve cups of varying volumes set out around the world to kiss the cheeks of its vulnerable. We talked about your crush (which changed more often than mine), words light like helium balloons rising with the sun on this particularly windy morning. It was your capacity to love that struck me, unconditional born from conditional. You pulled your big yellow sweatshirt over my head and it hung to my knees. You asked me, Do you ever want to go home?

At the end of the second month, your strikes had run out two times over. Our leader/teacher/29-year-old parental figures were at the bottom of their patience no matter how much I poured in. I remember the night they confirmed your face with the bartender. I wiped my tears and sucked in my breath before knocking on your host mom’s door. It took two hours to pack your bags in slow motion. It was silent except for our breath and the thump of the big yellow sweatshirt you tossed to me.

I often wonder if finishing the program would’ve been good for you, whether it would have filled your cup with joy and connection and love for travel and nature and food and people as it did mine. Sometimes I think it would have, and your parents would’ve paid for your degree, but on the days when the sun can’t break through the mist, I assume they would’ve found another excuse to reopen the hole we patched in the bottom of your cup. Sometimes I am angry at them and us and me for failing to give you infinite chances, sometimes I am angry at you for sucking them dry.

When the program ended and I turned on my phone, your hair was seven months longer but your laugh still made mine bubble. You helped me navigate American suburbia, and I tried to fill your cup with tools to process what we’d lived too late after the fact.

You can do this, you insisted as I melted down in a yard I didn’t recognize, afraid to drive a car I didn’t recognize.

People can be good, let them. I promised when you called me at almost the morning, trying to gain footing on a crumbling floor.

A big yellow sweatshirt held me together during my second attempt at the grocery store after my first left me crying in the cereal aisle cursing surplus, options, and American waste. The broken pieces of the lives we returned to were different, the people who left them and the ones that returned even more so.

I met the messenger by accident. My cup one year fuller, I set out to study abroad

across a different ocean and threw out your name as the only thread of connection I had to the hometown she named.

I went to highschool with Sasa! she squealed, hugging me. You beamed when we called, but I thought I made up your urgent strain behind I wish I was there.

The broken pieces of the lives we returned to were different, the people who left them and the ones that returned even more so.

In between your questions about my efforts to find joy and connection and love for travel and nature and food and people, we talked about your steady climb. Your life was boring you, but it’s the good kind! It was school and work boring, preparing and building boring. Soon! I promised. I am so happy for you, I’ll see you soon.

I was wearing a big yellow sweatshirt the third time you took my breath away.

I can’t stop wondering how your tent popped open and I can’t breathe.

It’s the only thing I see when I look at police photos of the wide, grassy median of I-295 northbound on-ramp from Washington Ave.

I wonder if it was lodged between the two halves of your car that wound up ten feet apart severed by two tall pine trees that are still standing and you’re not and I can’t breathe.

I wonder whether you had been coming from or seeking a campsite, a night in the woods away from the city that suffocated you and I’m suffocating.

I wonder about the rate of your breath when it stopped. Was it fast or was it still? Is mine fast or is it still am I breathing still?

I wonder whether you had been tossing an empty can into the trash bag you kept in the backseat of your car to keep your friends from littering or just drinking in the wind that raced by your open windows way too fast or had you been drinking? My throat is closing I think. Did you hear that Sasa? If I start to suffocate you have to save my…”

I wait for your laugh.

I often wonder at the volume of your cup when it bottomed out. Sometimes I am angry at them and us and me for failing to give you infinite chances, sometimes I am angry at you for sucking them dry. Most of the time I pull a big yellow hood up over my ears and try to remember to breathe.

bed of a pickup, circa the end (beginning) of the world digital photography

I’m cleaning out the attic when I see it. Something shiny lodged in between notebooks, trinkets from my college days, and other forgotten things. I fish it out from the bin. It seems so long ago now since my childhood friend, Ude, found this box.

I remember it clearly. It was a sunny afternoon in March, and the Lagos heat was so hot it burned. He was wandering home from work sucking on a cigarette when he spotted something shiny beneath one of the kola trees. It was a heavy little black box, dirty, only barely the size of his palm, and smooth to the touch. It had a lock on one side and a shiny smooth metal plate that shimmered under the bright sun on the other. He took it with him; I don’t know why, there was nothing remarkable about the box, but I can imagine him dragging himself home that day with the box in tow, fiddling with it absently as he went.

“What if it’s juju1?” Asa asked, when Ude told us about it later that afternoon. “It’s not juju,” Ude replied with a smirk.

“How do you know?”

“I haven’t turned into a goat yet,” He laughed, but his little brother didn’t think it was funny, and I understood why. There was a Babalawo2 that lived just a few streets over; we always saw him walking around half-naked and chanting incantations to himself like a mad man, throwing cowrie beads into the sand and ringing a handbell as he walked. He passed through at least once a week, and children and adults alike avoided him when he did. My mother always said God would protect us, but none of us were stupid enough to actually go looking for trouble.

Asa hadn’t always been afraid of the Babalawo though. When we were all younger, we would go peek into his shrine when the man wasn’t there. The shrine was a scary place, all smoke, torn red fabric curtains, and mask figurines, and we would take bets on who could stay there longer, always standing outside because even as children we were not bold enough to enter. But only a few months before

1 Juju – dark magic usually used for evil / nefarious purposes

2 Babalawo / jujuman – A dark magic practitioner in West African cultures

then, when Asa and Ude’s father had gone to prison, their mother had told anyone who would listen that their uncles, envious of their father’s successful trading season, had “done juju for him.” She’d told us they’d probably taken his photo to a Babalawo somewhere and cursed him so the police would mistake him for someone else. Their mother had called the pastor all the way from the next town over to come and pray for their father every day for weeks, and when by the end of it, Ude’s father was still in prison, we all knew the truth. If we were all being honest we didn’t even need the “failed” prayers to tell us otherwise. The whole neighborhood knew Ude’s father had made his money swindling lonely old women and selling things he did not have, buildings, cars…

“

ole3! old man like you, stealing like all these small-small street boys.” One of the policemen had said when they’d found him, the Yoruba word for thief coated with malice as they said it, like his crime directly affected them, like it was personal. We’d all watched that day as they’d dragged Ude’s father by his nice button up shirt into the back of the police car and driven him away to the run-down jail a few towns over.

But Asa had always been gullible, he was only two years younger than we were, but he was always so easy to fool. I’m sure even now he still thinks his father was cursed by a jujuman, just as his mother had said.

“What about you, Ada? Do you also think it’s a juju box?” Ude asked me later that night as we lay in his bed, our bodies slick with sweat from movement and heat. He did that often, talked around the elephant in the room, avoided asking the questions he most wanted the answers to, and usually I allowed him because I didn’t want to ask them either. But that night I couldn’t. I didn’t want to talk about the dirty box in the corner.

“Dad bought my ticket today. I leave next week.” I said instead.

“So you’re really going then.”

“I am.”

And that was the end of the conversation. Usually after our trysts, I would linger, would spend risky minutes tracing fingers up and down his skin, like everything would be alright if I was just touching him. But that night he only just shifted away

from me, right to the edge of that tiny mattress of his, and then turned around. He fell asleep almost immediately, and so I got up and gathered my things. When I snuck out from his room that night, making the quick walk across the street back to my own home, I thought that would be the end of it.

It was not.

The next time Ude brought up the black box was only a few days later. His older brother Markus was back home again; his college was on strike for the third time that year and the professors refused to teach until the government met their demands.

“That’s the problem with Nigerian public universities,” my father always said. “Teachers think they can get whatever they want if they just go on strike.” I can imagine him sitting for breakfast at our dining table back then. The way he laughed when he read the morning paper. “It’s not possible Ada,” he would say to me. “The government might be corrupt, but these so-called professors are corrupt too. We’re all corrupt here.”

So, Markus came unexpectedly as the corrupt government and corrupt school and corrupt teachers played tug of war with his education. He was a computer science major, a course that should have taken him four years to complete, but he had already been at it for five, and it would be six before he graduated.

“I can take it outside and pound it until it breaks,” Asa offered.

“No, fool. What if there’s something inside? You’ll break it if you pound on it like some uncivilized brat,” was Markus’s reply. The word “uncivilized” was his favorite to use those days, particularly for his brothers. He was watching a lot of the history channel and was a bit obsessed with western culture and the idea of civilization, knew a bunch of useless facts too.

“Do you know that “barbarian” was a word the Greeks used for people who weren’t Greek?” he’d told me once all those years ago. It was the day my father had told me I would be going to study in America, only months before Ude and I had even graduated high school, before their father had gone to prison. God, it all feels so long ago now. I’d rushed across the street to tell Ude and Asa the good news but had met Markus outside instead, leaning against a wall as he smoked a cigarette. Now that I think of it, he’d probably been sent home that time because of the strike

too. I was so excited about the news that I’d told him before anyone else, but he’d only taken one good look at me and shaken his head.

“Don’t you think we’re all so uncivilized in Nigeria? So barbaric? You’re so lucky you’re getting out; I wish I could go too.”

I remember the way Markus looked at the box when Ude showed it to him, the way he examined it with keen eyes.

“Leave it with me; I’ll take it to the locksmith.” He offered when Ude asked him what to do with it.

“No, that’s fine, I can take it myself.”

“What? Are you scared I’ll steal your fortune?”

“You? absolutely.”

They both acted like it was a joke, something to scoff at and forget, but I remember the flash of pain in Markus’s eyes when Ude agreed. Maybe a bit of anger there too. I didn’t know why, then, and I didn’t think much of it because Markus was always angry, but I think I do now. I think maybe Markus felt at that moment like he was starting to seem like his father, and there was nothing the three brothers feared more than becoming their father.

“I don’t think I can come to the airport.” Ude said later when we’d mended things.

“Why not?”

“I have to go to the locksmith, see if I can get the thing open.”

“Take it another day.”

“This locksmith is very good; he’s only in town once a month.” “Then go another month.”

“Of course you don’t understand; I can’t just take a three hour trip anytime, Ada. Markus is heading back to school, so I’ll hitch a ride with him.”

“I’ll pay for it.”

“You mean daddy will pay for it? No, thank you.”

That was another thing between us now, money. My family wasn’t rich but we were still much better off. It hadn’t been a problem before, but after their father had gone to prison it started to seem like something Ude held over me anytime he could. Markus too.

“Fucking rich girl,” Markus had called me once when I had run into him as I snuck out of Ude’s room.

“We just fell asleep…” I’d begun searching for a believable lie, but he’d stopped me.

“Please, you think I don’t know you’ve been fucking my brother when everyone goes to sleep?” I remember the way he laughed when he said it, like he felt sorry for me.

“Nice rich girl, slumming it with us until you leave us behind. You might have Ude fooled, but I know who you really are; I know you don’t give a fuck about him. Just using him.” He’d staggered as he spoke, his words reeking of weed and alcohol, and the next day when he’d grunted hello to me as I walked with Asa, I knew he didn’t even remember.

Those words stayed with me though, they ate at me through my first year at college because as much as I loved Ude then, I knew it was the truth. I think even then I knew I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life obsessing over whatever shiny new rubbish Ude obsessed over.

“I’ll see you before I head to the locksmith,” Ude said.

“Fine.” I replied. But he didn’t come to see me at all.

I knew he wouldn’t. I saw the determination in his eyes when he said he could not. When I called him screaming and crying from the airport, he told me it was all because of the box. He left early; he was still with the locksmith. “It’s welded shut Ada,” he said. “It’s not easy to open.”

At that moment I knew he was lying; everything he said was bullshit.

When I’d left his room the night before, I’d taken the box with me, so unless he had traveled three hours away for another juju box, I knew he didn’t have it and didn’t come anyway.

At that moment I knew he was lying; everything he said was bullshit.

“ ”

“Did you know I took your picture to the shrine of the Babalawo that lived in our neighborhood?” Ude told me over a phone call when we reconnected years later, laughing as he said it. “I told him to do anything so you would stay.”

“Really?”

“Yes, he poured kerosene all over the photo and said some incantations as he lit it on fire; God, I was so stupid back then.”

“You’re serious?”

“Yes, I would have done anything so you wouldn’t go, or maybe so I wouldn’t stay.”

“Even juju?”

“Even juju.”

I broke the box as soon as I arrived in New Jersey. I didn’t even wait to get home before I pulled it out and smashed it against the concrete outside the airport. It took a few tries, but eventually the metal plate gave out. It cracked open, and I pulled it apart from there. It was just as I’d thought; there was nothing inside. But it was still so disappointing. I think I hoped Ude was right; maybe if there was something inside it would be easier to swallow that he never came to say goodbye.

But inside the box was only air.

“That dirty thing?” He said when I asked him about it later. “I lost it after you left.”

“So you never found out what was inside?”

“Nope.”

“That’s disappointing.” “Indeed.”

I never did tell him I stole the box all those years ago. I wonder as I look at it. Now, when I tug its rust covered skin, it pulls apart easily, all broken wood and metal.

I should throw it away, along with all the other old things I’m throwing away in this attic, but instead I put the box back in the bin and cover it. I think I’ll forget it again. It’s all so strange now anyway, so blurry.

Its steely ventricles clank and spill coppered blood against cool metal knife.

Shadowed sap pools and puddles, viscous sop, crude-oil slick. On the grime-tiled floor, meat-thick eager tongues lick.

The pulsing storm begins to clot, slowing from taut purple veins. As the body heaves, gasping bloodlines beat out regal stains.

Under its skin-scraped scales, sweet flesh is scooped from hollowed husk: gutted, lips puckered, clouded eyes bulging, the drum slumps limp-finned into dusk.

If I hadn’t taken the photographs, I never would’ve believed it. If you crop them just right, they look beautiful: your face haloed in silver moonlight by the astigmatic lens, your lips red, your eyes that rich, cavernous brown.

You have no idea how badly I wanted to slink away with my polaroids and leave you to your work.

My father was a postman. I never told you about it, but he was a postman who had wanted to be a poet all his life until he turned out to be a lousy poet. My memory fails me when I try to recall that much about him. I remember that he was out a lot and that he had black hair that faded at the top of his thin, scaphocephalic skull (which he told me was all a result of his mother having narrow hips). He had a wiry mustache and pale eyes that were chronically twitching and damp.

In the early 50s, he was fired for stealing love letters the girl next door wrote. The photocopies he made wore out over the years from repeat readings. They’d cost him so much—his job, his marriage, his dignity—and at the end of it all, it was all fine with him because he had his photocopies and her words forever. Whatever they meant to him.

I liked poetry, but I was cynical enough to know I’d never be good at it. I left it to Donne and Shakespeare and the other Elizabethans. I’ve always liked that period in history, and come to think of it, that may be why I liked you so much upon meeting you when your long, pale hand crept into my vision at the desk beside me, and I asked you for a pencil.

“I only have pens.” You produced one. The ink that came from it was runny, cheap.

“Thanks.” My voice cracked when I said that. Do you remember? You didn’t even look at me, and I don’t think you remember the interaction at all, but I remem-

bered your curls and your long, straight nose for weeks afterward. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a girl as thoroughly out of place as you. You belong in portraits painted with copper and smalt, in illuminated manuscripts, in sketches drawn in quillpoint. You were only born in 1965 because God wanted to play a cruel joke on us.

I hope you didn’t take any of the above as an insult. If I know you at all, you agree with me. If you don’t, feel free to write back and tell me.

I made a concerted effort to sit next to you in the hall after that. I traced your face in my mind until I could feel your skull under my fingertips. You and I spoke here and there, your voice too low and raspy for your face, and I hung supplicant on every word. All that considered, I’m sure you knew I was lying when I approached you in front of the student union.

“It’s a photojournalism project. About women.”

“About women.” You raised a dark, arched brow. “That’s it?”

“Yes. Sure. Listen, all my other friends have said no, and I’m running up on the deadline.”

You looked at me then, tilted your head, balanced my mind on the edge of your finger.

“I’ve never asked—can you cook?”

“Yeah.” I really could—it was my only domestic skill.

“Make me a steak,” you said. “A nice one. And I’ll be over tonight at eight.”

So I did. Ribeye, with fresh bread, with mushrooms and rosemary. I ate my steak with a pale pink center and gray edges, and you ate yours rare and cool to the touch, savoring each bite. You laughed at me, your white chalcedony teeth tearing at the meat as I told you stories of cooking for my mother during the summer when she slept until four in the afternoon, of breaking my nose chasing a stray cat into a ditch. Late in the evening, you sat in my open window and let me take picture after picture in the warm light of a November moon, your white-blonde hair catching a southern wind.

You took my virginity. You left—slipped out of my room in the early morning, took one of my tired old tees like a hunting trophy, and vanished. It was over the instant I woke up, that you moved from one night to the next like an odd dream. I had the bruises your thumb left on my collar and the taste of blood and skin in my mouth—nothing permanent. Nothing real.

I saw you on campus a lot in those next few weeks. Other people, too, but you were the only repeated figure in my memory. I saw you shimmering in the morning light outside Debnath Hall, eyes turned directly to the sun, scrawling feverish notes

on the back of your hand across our one shared lecture hall, hovering phantasmal in the warm brick shade of the cafeteria. You didn’t look at me once, but I used that little mint-green Polaroid every single time, and I knew you could feel me taking them.

Something inside me cracked over the winter holidays. Maybe I realized that the odds of us having another class together were zilch to none; maybe I was just walking the empty bones of that campus too long, hiding in my dorm like a rabbit at the slightest murmur of thunder. I inherited a suicidal idea of romance from my father.

Things were wrong when you came back to campus.

I wasn’t content to catch you on occasion. I sought you out. I drank coffee after coffee at the café on Solomon Street, waiting for you to come in. I sat in the awning of the fire exit across from your dormitory to watch you walk inside. You didn’t know I could see you this time. I waited until dusk, I lurked, I starved. It was a sickness.

But if I hadn’t, would I have found you there?

I set out on that final walk at one in the morning, wandering aimlessly toward your residence hall. You were already outside, waiting for the late bus, shadows heavy under your eyes. A boy stepped off and into your arms—you drowned in that long, suede coat he wore.

My throat was dry. I froze in the January morning as I followed the two of you, feet soft in the powder snow. You took him off campus and into the part of town where old posters skitter into gutters. I lost sight of you.

I went into a bar after that. I’ve never been able to tell you this part.

“You alright?” a woman asked.

I nodded, my head listing toward the bar. The bartender was pretty, maybe even beautiful. And unlike you, she was thoroughly modern, fit for this day and age, with sleek brown hair and tan skin and coffee-ground freckles.

“You look cold.” She slid a glass of water to me without ice and waited for me to take a sip, and I did. Feeling returned to my lips, and after a few minutes, I gave her a wan little smile to assuage her worries.

“Thanks. Thanks a lot.” I held my drink in a clammy hand. “I’ve had…a night.”

“A night, huh? Yeah, I get that.” She placed her elbows on the bar and regarded me in my flimsy powder-blue sweater, eyes grazing the chill-cracked skin of my

knuckles.

“Do you?” My next smile was wider. She snorted and placed a straw in my drink for me, her pink nails clicking the rim.

I made up a story about being ditched after a fraternity party when the cops arrived. She loved it. We talked for almost an hour, alone in that little spot of yellow warmth in an arctic January winter. In a moment of silence, I caught her eye. It was a bright candy-coated brown that glinted in the filament bulbs.

I felt more like a real person in that moment than I had in months.

I was suddenly afraid.

I left without another word. In my last glance of her, her lips are barely parted, and she’s about to call something after me that will be lost in the wind outside. I had to find you. I started back toward your dorm with my head down and the front of my sweater pulled up over my nose.

So that’s how I found you in the alley.

You may not believe me, but it really did take me a moment to realize what you were doing. I saw your eyes first, the lightless abyssal brown, the white of your sclera and the flush pink of your retinal veins. I raised my camera with numb fingers, reeling with the distant realization that I was only five feet from you, and clicked the shutter.

You stilled. I let the camera drift from my face.

Under your January-pale hands, already half-submerged in snow, was your friend. Your boy. You kneeled over him, one palm on his sternum, the other wrapped all the way around the exposed red-brown tip of his spine.

“Hello,” you said, or it might have been the wind.

I didn’t reply. I was holding the moment in my mind, wondering where to place it among all of the others, among the images of you studying and sipping tea and letting the sun wash over your face. I set it next to the picture of you eating steak, raw and red. I opened my mouth to ask you a question. But you’d already misread me by then. You read my hesitance as fear; you read my silence as the glottal panic of a prey animal. I barely felt your fist hit my chest. The crack of my head against the brick sent a wave of pain through my bones and skin and the jelly of my eyes.

I fought you with broad, baffled swings. When I was young, my mother showed me a video of a pitbull trying to kill a horse. You were the dog.

I was just going to ask you a question.

The first man came right after you split my left cheek to the ear. I’d screamed

without realizing it. More people came after that, saw your white teeth and the blurry, clotted red stain all along your chest, the half of your date you hadn’t already picked to the bone.

I don’t know what you did to them. I was already asleep, dreaming about letters.

They found my camera and the photo with it at the scene, took it as evidence, scraped the genetic clutter of dried blood from the lens and dropped it in tubes. My injury left me unable to speak for weeks, but they’d still like me to testify.

I don’t think I’m up for it.

All I wanted to ask you was why you hadn’t eaten me. Why you’d eaten steak, raw and red, watching me stammer and stutter, and you did not lunge for my throat. Why you hadn’t asked for a kidney, a finger, a cut of my thigh. Please write back. I don’t know if they let you read these. I need you to know. I won’t be angry, no matter what the answer is. If it’s that if you liked me too much, I’m honored. I don’t know what you are or why you did it or if you’re even human.

And hey, maybe the boy in the suede coat deserved it. If it’s that you weren’t sure about me—that I was an innocent, warm body and nothing more—know that I would have welcomed it from you and only from you. I would have watched while you ate my heart in the marketplace.

I was holding the moment in my mind, wondering where to place it among all of the others, among the images of you studying and sipping tea and letting the sun wash over your face.

to relish you (as I did) I must:

step out naked into daylight: lie, confront the mirror with the apex of my pelvis. Take each hipbone to the crescent of my palm and know—know they are stronger than sabre, stronger than whale bone, mammoth tusk bellowing inside of me. Look each limb in the eye. Hold my gaze; drink, drink deeply from the collarbone goblets from the water at bay in the wink of my arm gulping the droplets that quiver in transparent moons like a child at the drinking fountain. Lick my body like a thirsty plant. Like a molly cat bathing her babies. Lick my nose because I can. Suck on my arm jam ‘til love bites bloom, skin red and pulsing with the ability to kiss back; kiss each finger as I lick food from her; kiss each plump tip as though it is topped with a raspberry. Delicious! Kiss the prickled peaks of my knees; I might let me sprout into a great forest—taiga, boreal, garden orchard—and kiss that too, drawing suns in all the corners I once begged not to fold like a child crayoning every corner of a page yellow. Nimbuses of holy gratitude. Kiss only those who make my body feel like a body— who speak with eyes of desire and see me living, flushing between the lip of being real (no more than a body) and a body, hailed godly: the weight of a flesh that moves creases, pulses, swells, foams, storms with the gravity of solar, with cosmos. The celestial warmth of a back dimple. Gaia, Terra, Jörd, Orion’s belt: the Three Sisters found in every trinity of cellulite Libra’s suns and stars shining in arcs through the chiffon veils of each stretch mark.

and the rest is drag digital photography

Is it proper etiquette to shave for your gyno?

—I ask myself too late. Three strangers huddle together in a cramped, frigid examining room, eye level with my perineum’s knotted whorl. There’s one more standing at my head. Surrendering her bony fingers to my pained grasp.

Diplomatically, she looks everywhere but below the thin blue crepe paper draped over my waist. The wall of blue makes abstract the gynecologist’s narration: words like “speculum” and “tenaculum” and “intrauterine device” float up from behind it and dissolve before they reach me in a cloud of disinfectant and nerves.

I try to focus on the ceiling. Technicolor blue and fuchsia dots bloom, starbursts exploding in and out of my vision as she inserts an impossibly tiny, T-shaped piece of copper up into the plum’s pit that, if you sliced me open and peeled the softness back, sits just beneath my navel.

The copper, so that any sperm who dare to invade are poisoned. A drop of arsenic in the ambrosia.

Copper: one of the seven metals of alchemy, associated with Venus, Goddess of Love. Desire, sex, creativity. Also, fertility—ha.

Copper: electrical wiring. The coating of a penny. Circuit boards. Vacuum tubes. Valuable, useful things. They must’ve thought, might as well weave it into this kind of tubing, too.

Copper: the ancient Egyptians used it to disinfect wounds, to clean tools before sugery.

Copper: seven years wed, copper: bringer of good luck. Opener of root and sacral chakras.

My root and sacral chakras convulse and wail as the gynecologist and her assistants ratchet the speculum’s duckbill even wider. To distract myself, I train my eyes on the poster on the wall that proposes, as size comparisons for the IUD: a strawberry, three almonds nestled one on top of the other.

A sugar packet. A strawberry, the poster sneers, is something that you can easily visualize, that

you might slide through your howling red causeways up into your uterus out of sheer curiosity. Or a slow Tuesday night. It feels impossible that a strawberry might trigger the ricocheting spasms so violent that my eyes roll, turning the volume up on the fluorescence so high that it turns black. This is what I signed a consent form for. It was a choice: the violent insertion I’ll accept now to avoid an extraction later.

They say Roe will be completely dismantled within the year.

“Big breath in,” the gynecologist instructs.

They say this is the first step to Gilead. I’m tired of the Atwood quotes. “And out.”

They say this is the first generation of women that will have less rights than their mothers and grandmothers.

“In…”

I also signed on the dotted line to adorn my insides in copper wiring, to alchemize fear into pleasure.

No one says, “I’m planning my life around where abortion might be safe and legal.”

No one says, “Even a 99% effectiveness rate feels tenuous, the only thing that stands between me and a clandestine extraction.”

“…and out.”

The IUD is insurance. It is exculpation, proof of due diligence, in case of emergency. As if they care. As if that would redeem me. My logic is Catholic, though I no longer am: suffering in exchange for salvation.

The gynecologist continues to rummage around, clanging her tools like tuneless wind chimes, cranking and dilating and plunging what feels like an invisible hand seizing at that plum’s pit, twisting and now meaning to drag it out of my body the way it came.

“All done,” she chirps. One of her assistants busies herself with cleaning the tools. More antiseptic. Gauze. They seem so innocuous now.

I sit up. There is blood on the blue crepe paper.

The gynecologist shuffles through the after-visit papers, staples, signs, and dates on the dotted line next to my nervous scrawl. Dense paragraphs list all the possible complications and side effects I’ve apparently agreed to. Or at least acknowledged: “… may attach or go through your uterus…may cause anemia, pain during sex, spotting, heavier bleeding, and backaches…has been associated with increased risk of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease.”

I study my signature, doubled over. I signed on the dotted line for this, all the things that could go wrong. I signed for the promise of total protection for ten years. So I wouldn’t have to sign over the deed to my body before then. Fingers crossed, will that be enough?

But I also signed on the dotted line to adorn my insides in copper wiring, to alchemize fear into pleasure. To carry with me always a totem of desire and luck, a talisman of circuit boards and pennies.

To be reborn a Venus from the inside out.

1 “Copper Symbolism: Meanings, Rituals - The Lucky Antler.” Accessed January 21, 2022. https://theluckyantler.com/copper-symbolism/.

2 Miracle Aerospace. “Why Is Copper Used In Printed Circuit Boards?,” November 27, 2018. https://www.miracleaerospace.com/blog/copper-used-printed-circuit-boards/.

3 ebay. “Vacuum Mechanical Gauge Copper Tubing Line Kit 1/8” OD x 12’ Foot.” Accessed March 10, 2022. https://www.ebay.com/itm/222113072704.

clean acrylic paint

where’s my daughter? she hands me this enigma and tells me to go get the vhs out of her bottom drawer again. i quietly watch her go

back to 2007: a hot august in ferguson, hot enough to fry ravioli. girlhood pouts at the camera in her clear jelly sandals—“go

play with your sister!”—that soft voice, so gentle you forget its capacity to shout//elicits feedback in her face//click. you go.

get up. leave. the routine has ended with the tape; she’s taught you ritual is a route to preservation, until you go

through motions enough that you believe them: praying to plastic jesus, conjuring thoughts about fake fucking boys, living for circles, so you go

back to the drawer. get the vhs for her again, and let her love 2007 without doubt//stagnancy overtakes this body//you know you can’t go

further than missouri. slip into the dogwood and busch cans— watch her seek out her annie in the places you’re already gone.

I touch the body and know nothing but inventory— nails entombed in graveyard dirt, spoilt cloth huddled at the feet, girlhood spent on wishbone, all unselved beneath the skin

I touch the body and know the only flesh left unturned stews in old stomach bile.

I measure worth in sharp edges: canine, knuckle, elbow, knee. The rotten thing puts up a good fight.

I touch the body and know how lungs always suffocate on truth, how worry-slick palms soothe a drowsy path to sawtooth hips. As violets petal at the wrist, I must call the vessel mine.

Maybe you’ll see her beside the bus stop as you’re stumbling back from a late night. When you meet for the first time, you are unsure what to call her. You like Marina because it sounds flowy, like a wave in your mouth, but for most of your life you were Marie. The -na was an addition, a result of your liberal arts education when you spent too much time trying to grow into your fully formed self. Maybe Marie sounds correct, but she doesn’t look like a baby anymore. Marie implies a red ribbon and patent leather shoes. Almost pure but not quite so. The first question she asks is whether you’re married yet, and you break out in nervous laughter.

The second time you see Marie might be more intimate. You’re staying at a friend’s place in Brooklyn, and the two of you are sitting on the floor, devouring a bowl of pasta and rehashing the most painful moments of your childhoods. And there’s Marie on the edge of the sofa, leaning in to hear the details. She hasn’t grown into her nose yet, and there’s a smattering of freckles across her cheeks. You wonder where all your freckles went over the years and why you’ve grown to detest summertime. You tell a joke, and she giggles. You didn’t think she would. Does she find you funny?

Eventually, you have to break the news that you’re a lesbian. (If she hasn’t already guessed by the number of rings you own or your love of Patti Smith.) So you sit her down for a talk. She cocks her head, fidgets awkwardly on the couch. But you see the gears turning in her head. Marie is remembering fourth grade and how much she loved to hear Ms. Dearborn read out loud from a faded copy of Bridge to Terabithia and how she went home and cried when the rope snapped and Leslie died. Maybe Marie doesn’t understand all of this at once. She might storm out of the room or sit in silence and shake her head. Either one is fine, but you can’t leave your little visitor hanging.

You remember that Marie loves to ride her bike around the neighborhood, so you buy her a tiny bike at a charity sale. The pedals are a little rusty, but she’ll make do. Your college town is small and unassuming, so you figure that she’ll find her way. One afternoon, she comes back with a twisted ankle, and you scold her for not being careful. In the grocery store, she throws a tantrum in the cereal aisle, and you try to

hide behind the Special K while a mother pulls her toddler closer to her chest. You try to remember the last time you cried like this and got away with it. You try to remember the last time you cried.

You are never without Marie. She eats your food, tries on your clothes, and follows you to your first real date in months. She sits next to you in the booth as you make awkward conversation with Christina, your lab partner who is good at making you laugh. You sip on your latte and Marie watches you backtrack on your words, agreeing but never adding.

Later, Marie will interrogate you.

“I wish you would try and act more like a person than an alien,” she says while standing on the sofa, suddenly a little adult in a gingham dress.

“Dating is hard. It wasn’t perfect, so what?”

“I don’t know. You look older, but you’re not. It’s weird.”

“What do you mean?” You are defensive without trying.

“Seems like…you haven’t done anything that a 20 year old is supposed to do.”

That one will hurt. You’ll go to bed and spend all night thinking. Maybe if you’d moved out earlier, or went to school in a different state. But nothing you say will leave you less empty than before.

You wake up and stumble downstairs. You bring Marie an ice cream cone for breakfast as a way of making amends, but she isn’t in the guest bedroom. She is nowhere. And the red bike in the garage isn’t child-sized. It fits you quite well, except the pedals are a little rusty. You bike up the hill, past the driveway with your mom’s sedan, no longer in your college town but somewhere more spacious, yet familiar.

In moonlight, Black boys look blue

- Barry JenkinsThe moon orbits around the earth in a motion that mimics the cycle of life. A circle of light that wanes and waxes to repaint the body again & again & again.

Maybe on a waxing crescent the Atlantic sloshes in our skin deep blue. Cyan blue. And the color will show us how to spill our bodies onto the shores of these new lands; but nothing tells us how

to lap at the feet of monsters and cleanse them into men. So we wait. Let the cosmos shift and the stars regroup. The sun aligns with dead stone and breathes the fire of life into it once again. Perhaps

the first quarter shades my brothers royal. Opulent hues that cry “Long live the Queen!” And the waxing gibbous makes my sisters Caribbean— hot and hurricane skinned. Licking salt and sugar cane off their lips to whisper:

Santo Domingo. But time passes and the world still turns. Light gives way to darkness which gives way to light once more. And a full moon’s pregnant belly will illuminate every plane of the body indigo. Purple-blue bruises that

bloom across the abdomen. Stain our fingertips rich and dark as we bend to collect the life we have cut down. The sun dips below the horizon once more. I pray that before tomorrow the waning gibbous will turn us sapphire. Hard. Icy.

Flashing. And the third quarter will ignite my chest in denim flames. Waning crescent, make us as azure as the Lord’s troubled water. New moon, hush the hues our skin sings.

***

Heaven shifts above—

God rolls over in sleep & turns his back on us.

Silent digital photography

A green sign welcomes me to Nebraska, the Home of Arbor Day, but I haven’t seen a tree since I left Indiana this morning. Ten hours of rolling across Illinois on I-74 and Iowa on I-80, and only corn stalks have broken the endless blue horizon. I’ve been driving with my sun visor down so I don’t feel so lost in all the blue. Corn on the left, corn on the right. Soy on the left, soy on the right. But no trees, so Nebraska might be lying to me. I’d like to pull over beside the Missouri River, uncap my giant Sharpie, and fix the sign so it tells the truer truth. “Nebraska: 7 Million Cows Slaughtered Every Year!” or “Nebraska: Home of 1.8 Billion Bushels of Corn!” or “Nebraska: More Cows Than People!” But I don’t want to be rude. I just got here. This summer, my job is to grow vegetables in two community gardens belonging to Together Omaha, the food pantry where I’m serving as an AmeriCorps member. The west garden is thriving. Twelve raised beds sprout zucchinis as long as my forearm, yellow squash that I swear weren’t there when I harvested yesterday, patty pan squash that swell into spinning yellow and green tops after heavy rain. The dinosaur kale grows like palm trees, especially when I pull the leaves from the bottom of the stalks, just like Nicole shows me as she leans over the bed in her knee-length khaki shorts. Tomorrow, Toni will exclaim through the two surgical masks she wears inside and outside that she can’t believe the leaves have grown so much—Nicole and I scalped them just yesterday! The carrots shoot their mint green feathers into a canopy that shades their orange and yellow bodies jostling for space in the soil. We’ll have to thin them out tomorrow, Nicole says. She threw handfuls of seeds into the dirt last month before Toni and I arrived, hoping that some carrots would grow long and thick enough to pile on the produce cart inside the pantry. She knew that some would only grow into nubs, but that’s how it has to happen. Some will live, and some will get ripped out of their beds by hungry gardeners.

I forget about the cows until I drive north on I-80 and pass the billboard of a

political candidate wearing a brown leather coat and cowboy hat, smiling as a herd of black cows watches from behind, yellow tags dangling from fuzzy ears. He says he is a true Nebraskan, committed to true Nebraskan values: faith, jobs, and family. He doesn’t say if the cows are Nebraskans too. He doesn’t tell us if the cows pray as the sun sets or flick their tails toward heavenly shooting stars. He doesn’t tell us how it feels when cold metal squeezes the udders of the mothers, siphoning the milk that will never reach their babies’ stomachs. He doesn’t tell us these cows are only three years old when they walk into the slaughterhouse, that they could live past twenty, that their muzzles could match as they turn gray. He doesn’t tell us that these cows are Nebraskans too.

Across 33rd street, the sun withers most of the plants in the east garden, but the collards love it. We scalp them every other day, snapping the foot-long leaves off the bottom of their stalks as Toni collects a bundle for herself—she can’t believe she used to pay two dollars at the grocery store for five leaves! The collards fill four beds and share two with Brandywine tomatoes and bush beans. The beans are ready to harvest when the green pods measure four inches and are so plump our mouths water. I perch on the edge of the bed’s 2x6 plank walls, snapping beans off their little green stems and tossing them into the harvest tray next to the handful of Green Zebra, Stupice, Valencia, and Big Beef tomatoes I pick from the plants that reach outside their Florida weave no matter how many layers of plastic twine we trap them in. The Cherokee Purples and Brandywines aren’t producing much fruit. One vine from each set of four has only reached the first level of twine, but I don’t want to rip them out yet. They could still have half their lives left.

I forget about the cows until Toni and I toss chunks of their bodies into the repurposed banana boxes the pantry has been distributing to customers for the last fifteen months, ever since the day in March 2020 when neighbors could no longer shop next to each other without breathing contamination in and out. The pantry managers tell us that we’re pushing chicken today. Each box gets two Styrofoam packages of chicken breasts, two hunks of ground beef, and two tubes of sausage. We pull boxes of chicken from the stack on the pallet, and as I lug the boxes of bodies, I remember the chickens I’ve carried at a farm animal sanctuary. They weighed me down like newborn children, their bodies not designed to live past slaughter weight, the weight of the breasts that I stack in boxes for those who can’t afford to remember. Once the banana boxes are full of plastic-wrapped flesh, we sprinkle in oranges from Brazil, asparagus from Peru, grapes from Chile, avocados from Mexico. We Tetris the remaining space with sugar-laced cereal, dinner rolls flavored with high fructose corn syrup, and excess mini pies that the Walmart bakery section

would throw away if they didn’t get a tax write-off for donating to the pantry. At the end of the day, the remaining bread collects in a cardboard watermelon container. A truck driver will transport the bread to pig, hog, pork farmers, who don’t always take the bread out of the plastic bags before churning it into the slop along with corn, hormones, pork, soy, and antibiotics. Pigs will eat anything, and time is money. When God called pigs unclean, he didn’t know how much a package of pork would sell for.

The pepper plants produce, but not without complaint. Every day, I pluck a couple two inch Padróns and green jalapeños, firm like rubber, and gather the long and skinny Jimmy Nardellos, whose yellowish-green bodies have fallen on the soil that seems too sandy and dry, even after two trips from the water tanks, stepping carefully to avoid sloshing too much water out of the cans. The Poblanos are giving up on themselves. Whenever I find one, a brown patch is almost always spreading outward, softening the deep green skin with rot before they’re half as big as they could be. I pick them anyway, hoping someone will remember to cut out the rot. The tomatoes must have an infection because the blossoms on their bottoms are leaving rotten patches behind when they fall into the soil. Nicole says that we should sanitize our pruning knives in between beds so we don’t transfer the disease. We usually forget, but we think the curse is in the soil, the compost that Nicole speculates doesn’t get hot enough to kill the weeds—how else could there be so many? But we use the same soil in the west garden, and we only have to weed those beds once a week. After our lunch break, Toni and I trudge back to the east garden, pruning knives and trowels in hand to dig out the weeds that Toni swears she pulled up yesterday—you’d think no one was weeding out here! The bindweed holds its ground, daring us to dig further; we still won’t find its root. Sometimes it’s bluffing. When we pull the white tendrils gently enough, they slide up the soil holding on to their dirty root balls. But sometimes we misjudge our strength, and the shoot pops, taunting us with the clean break because the roots have won. They’re stealing the water we carried all the way from the water tank, and they will snake their way toward the sun in the morning, sticking their green spade-shaped faces in our dirt-smeared ones, teasing the tomatoes with the nitrogen they’ve stolen from the vines.

I forget about the cows until I drive home from pickup volleyball with my windows down, radio turned up high enough to hear over the wind blowing in my ears. Just before US-75 turns into I-480, I choke on the slaughterhouse breath of raw hamburger, soaked in bloody iron and kicked through crumbled black July asphalt, steaming from the heart that still pumps heat. It’s a reflex. The heart doesn’t know its body is hanging upside down, split in half, skin peeled off the muscle like

a bandage. I roll up the windows and breathe in through my mouth, out of my mouth, apologizing to the sacrificial calves for our sins. How do we forget? There are so many slaughterhouses in Omaha. I’m sorry I forget. A couple minutes later, I pass Vinton Street, and I test the windows. All clear. In through the nose, out through the nose.

Toni and I miss the okra blossoming. We desperately planted the second round of black seeds in the rain when the original ones weren’t sprouting. We keep giving them chances, and eventually they grow, half with wine-red stems, half cucumber-flesh green, spreading their leaves as big as my palm to protect the bed from the sun that strengthens each day. The fruit doesn’t look like the finger-length okra I’ve eaten before. These are wide as the circle made between my thumb and pointer finger, decagonal shooting stars, almost neon green, hard as comets. When Nicole finishes her AmeriCorps service term, she leaves Toni and me in charge of the gardens, but we think the red and yellow flowers bursting out of the canopies will morph into the fruit like the squash and the cucumbers, so we neglect the okra as they grow into inedible monsters, thick enough to crack when I bend them and to thump when I drop them on the 2x6.

On my last Friday before I drive back to North Carolina, I comb the okra forest, sawing off the bizarre offspring. During the extermination, I find some that exhale when I squeeze them and that match my middle finger in length. Toni and I divide these into paper bags and place them on the produce cart, beside the tower of Guatemalan bananas that creep toward the compost as each day decomposes the yellow into brown. I try to save the bananas, but my freezer is only so big, and I can only eat so much banana ice cream before my brain freezes. Nicole, Toni, and I make liquid fertilizer from three boxes of bananas, hoping to capture the life from the decaying pulp and siphon it into the withering cucumber plants in the east garden who can’t climb a trellis to save their lives. We strip the bananas, cut the peels into square inch pieces, and toss them into a bucket full of water that will absorb their potassium. I dump the fruit into the compost bin with a potent sticky-rottingfruit-baking-on-asphalt-in-the-Nebraska-sun smell. At least you’ll become soil, I tell them. You didn’t travel here from Guatemala for nothing. I don’t tell them that someone would have eaten them in Guatemala. I don’t know how they prefer to die and resurrect.

I forget about the cows after a day in Lincoln, a tiny college town compared to the sprawling Midwestern metropolis of Omaha, one of the only places in Nebraska without corn and soy on the left and the right. Emma, another AmeriCorps mem-

ber at Together, shows me the gardens of her alma mater, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. We ogle the tomatoes, squash, and kohlrabi in the raised beds and the curtain of hops growing in vines along ropes that almost kiss the grass. I wish I had come to Nebraska for college until we walk past the acres of pastures where students learn to raise cows and pigs, beef and pork. After fawning over patches of cornstalks and sunflowers, Mom texts me to “Give me a call when you get a chance.” My lungs implode because, whenever she texts this, I’m afraid someone has died. I slip my phone into my pocket as Emma and I walk beside the river that is a trickle after swimming in the Missouri. Breathe in, isolation. Breathe out, contamination. Just breathe, it’ll be okay, no one died.

On the way back to Omaha, Emma and I stop at her parents’ house. They send me home with a bag of cherry tomatoes from their garden and a young spider plant in a green plastic pot. Back home, I set the spider plant on the counter in the sunset beaming through the kitchen’s seven windows. I drizzle her soil with water and stare at this fellow life form, my elbows propped on the counter, chin cupped in my hands with dirt-stained nail beds, breathing and thinking about how she is breathing too. I text Mom, “I’m home now. Free whenever you are.”

She calls me. Dad is also on the line. They are at Myrtle Beach, and they got some bad news today. She doesn’t know how to tell me this. Tripp Sanders, my high school youth pastor, killed himself. The rot had reached the seeds and the stem, and he’d fallen into the dirt.

I go to the gardens the next morning. The beds are full of weeds that Toni swears we pulled out yesterday, so I can’t miss a day and let the weeds steal more oxygen from the peppers after they took it from Tripp. Plunge the pruning knife into the dirt. The weeds killed my friend with floppy forehead curls and eyes that listen to my words like nothing has ever been so important. Push down and wiggle the blade. The weeds killed my friend who buys a basket I make out of plastic bags to display in the house where the youth group worships God. Slice the roots. The weeds killed the first man to tell me he is a feminist, who teaches me to trust myself, who says he loves me when I leave the church. Yank the weed out of hiding. The weeds killed my friend who wears sun visors and tucks his scrubs into his socks. Wrench open the compost lid.

I don’t know how they prefer to die and resurrect.

The weeds killed the man who freestyle raps about Jesus in front of the congregation and lets me forget my shame. Hurl the weed into the darkness. The weeds killed my friend who closes his eyes when he sings and stretches his hands toward his creator. Plunge the knife into the dirt.

I can’t sob until my sister holds me. Four days have passed since Mom called me, but I don’t trust the cucumber vines to carry my cries to heaven, demanding that Tripp be returned because we have so much left to talk about. When Charis flies into Omaha from Atlanta, I take her to the Together gardens and introduce her to all the plants. She holds the twine while I wrap another level of Florida weave around the garden stakes, ensnaring the tomato plants succumbing to gravity after heavy rain. We drive home, and I am no longer alone in my empty apartment, so I set down the knife that is chopping broccoli and fling my arms around her shoulders, spilling the grief down her shirt, retching the chunks of despair up with the snot and the spit and muffling the mammal sobs with her tissue. I hang onto her frame like a tomato plant bending toward the earth in a thunderstorm, clutching the twine as my roots burst through the soil.

The next morning, Charis and I watch the livestream of Tripp’s funeral. The pastor reminds us that weeping may be for the night, but joy comes in the morning, and I remember the cows, who travel from feedlot to slaughterhouse at night, only visible through the metal holes in the eighteen-wheeler when the Iowa moonlight reflects off their Nebraska eyes. The bush beans will absorb the sunlight that the cows will never see, the morning they will never breathe. Weeping may endure for the night, but joy comes in the morning. Hallelujah for the joy, but there is no joy in the morning after the rot in Tripp’s mind reached for a gun, and now his life is half of what it was supposed to be, and most of us didn’t get to say goodbye, and his kids have to live without their dad, and Jen has to lie awake in bed alone, and who knows how many of the mourners at the funeral will keep voting for bullets in brains and stun guns in foreheads because it’s their God-given freedom to fill the earth and subdue the beasts of the field and the birds of the air and the fish of the sea and be proud to be an American where at least I know I’m free hallelujah for the joy don’t tread on me don’t

Weeping may endure for the night, but joy comes in the morning.

take my guns from me I live for God and God lives for me hallelujah for the joy lift your eyes toward heaven with no more death and no more tears with thoughts and prayers and praise God and hallelujah for the joy for joy comes in the morning, joy comes in the morning, hallelujah for the joy.

In the morning, we remember Tripp, and we weep.