EDUCATION

École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville - Paris Master of Architecture (2nd year) from September 2023 to present

John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design University of Toronto - Canada Mobility semester from September 2023 to January 2024

Technische Universität - Berlin Erasmus mobility year from September 2021 to August 2022

École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville - Paris Bachelor’s degree in Architecture from September 2019 to August 2022

EXPERIENCE

PUYA Landscape & Urbanism – Marseille Employee from April 1st to July 31st, 2024

KVA Architectes - Paris Internship July & August 2023

LBN Les bétons Niçois - Nice Internship from end of February to mid-March 2022

NSL Architects & Engineers - Marseille Internship from mid-July to mid-August 2021

SKILLSET

CAD: Autocad, Archicad, Rhino Good mastery

Adobe Suite: Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign Very good mastery

3D: Archicad, Sketchup, Revit – Good mastery

CONTENTS

01. Architectures of the limit

02. Museum of memories and cultures of French Guiana

03. Battery park

04. Water landscapes

05. Greening strategies for the parisian “banlieue” 06. In-between façades, Stadtmosaik

WRITTEN MASTER’S THESIS

Life, ignored by those who make the city - lessons from the Marseille Flea Market in the Euromediterranée Era

Critical analysis of the urban renewal project "Les Fabriques XXL" led by the Euroméditerranée public development establishment

Presented in June 2024

COMMITMENTS

A.S.L.A Member (American society of Landscape Architects)

A.I.A Member (American Institute of Architects)

LANGUAGES

French: mother tongue English: mother tongue Professional English : C2 Professional German : B2-C1

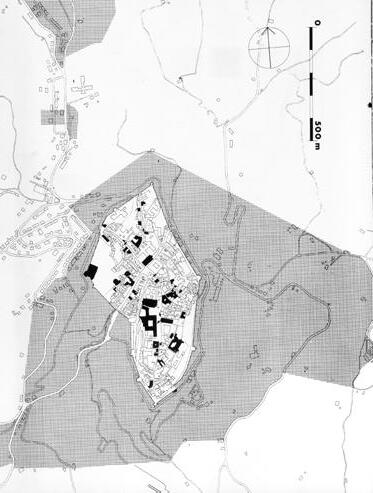

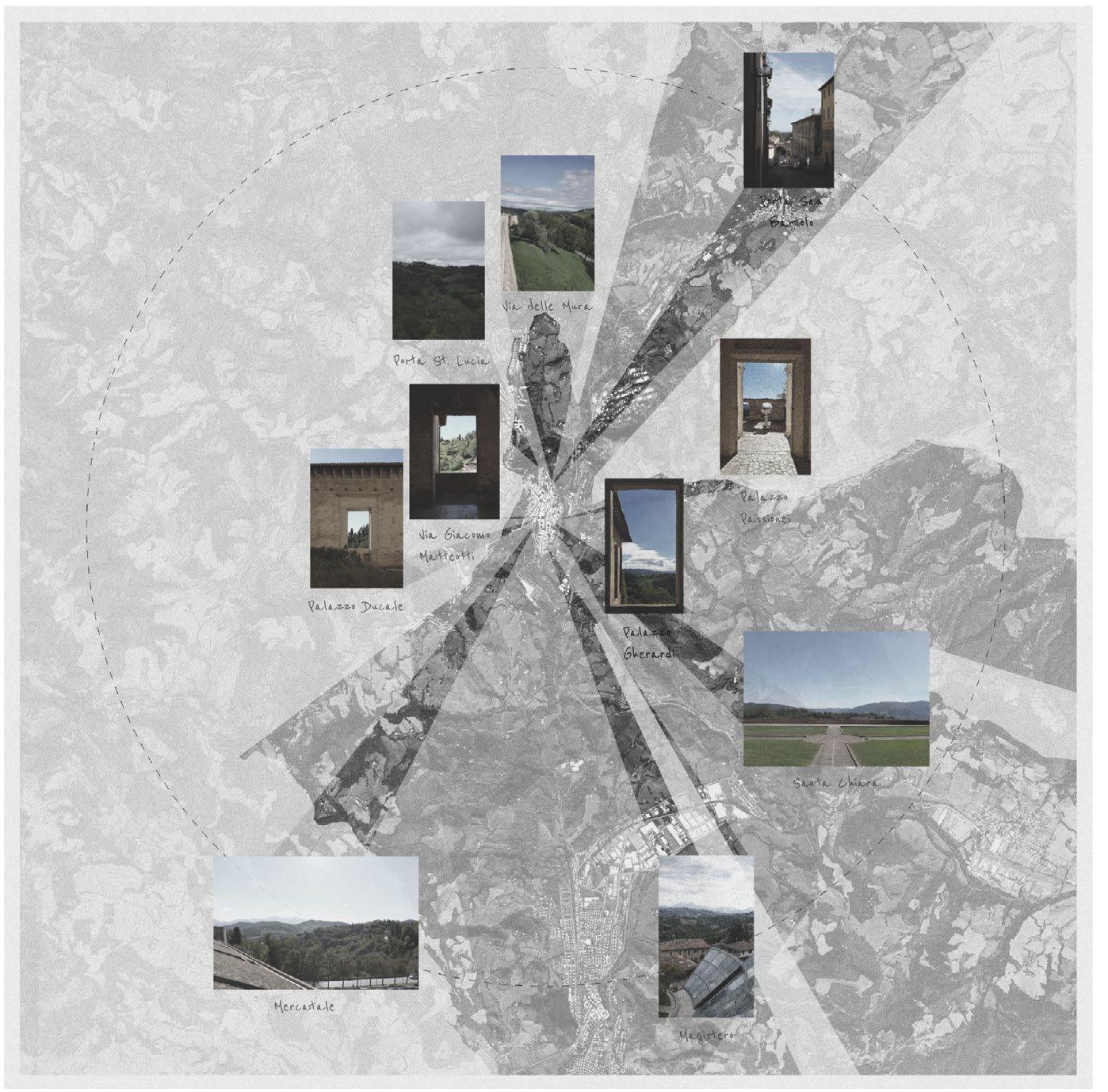

QUESTIONNING MODERNITIES IN URBINO : ARCHITECTURES OF THE LIMIT

End-of-studies school project, studio “Questioning modernities”

Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville

Instructors : Francoise Fromonot, Roberta Morelli, Emilien Robin, Béatrice Jullien

Partners : Clara Doceur, Melis Selin Kocyigit

At a time when urbanization is erasing the boundaries between city and nature, reducing land to an exploitable resource, the climate crisis requires us to reinvent the relationship between architecture and landscape. Urbino, with its Renaissance architecture, offers a model in which the landscape is actively constructed by the architectural gaze. Today, revering the landscape as nature to be “touched with the eyes” is a powerful idea. This model invites us to explore other ways of inhabiting and delimiting territory, while questioning the tensions between appropriation and preservation.

The International Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Design (ILAUD), founded by Giancarlo De Carlo in 1976, has advanced a tradition of thoughtful design that balances historical context, natural landscapes, and modern needs. De Carlo, a key figure in the Team 10 movement, championed architecture that prioritizes human experience, inclusivity, and environmental sensitivity. His work in Urbino exemplifies this approach, fostering a dialogue between heritage and innovation.

Historical analysis of Urbino’s fortifications

Digital drawing, AutoCad + Illustrator

1/ The Roman Fortification

Urvinum Mataurense, the ancient name of Urbino during Roman times, developed exclusively on the southern hill. The city had four gates: north, south, east, and west. Its walls, built in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, closely followed the topography and were constructed using the opus quadratum technique, which involved dry-stacked, finely worked stone blocks.

2/The Medieval Fortification

During the Middle Ages, Urbino remained within its Roman walls until the 11th century. The city’s second fortification, built in the 12th and 13th centuries, expanded slightly to the south but primarily to the north to address and correct a military vulnerability.

5/ The Current Fortification

The current fortifications are identical to those of the High Renaissance. In the 19th century, numerous modifications were made to accommodate the changing needs of society, including the advent of cars. Over time, the walls fell into disrepair, and by 1960, parts were nearly collapsing. Architect Giancarlo De Carlo conducted extensive studies on the city, highlighting the significance of its historical heritage. These efforts led to the adoption of a 1968 law providing financial support for heritage conservation, enabling the restoration of the fortifications.

3/ The Fortification of the Quattrocento

Urbino’s third city wall was built after the Montefeltro family took permanent control. Federico III da Montefeltro commissioned the fortification, along with the stables, the helical ramp, and the Mercatale dam. This period marked a phase of prosperity for Urbino.

4/ The Fortification of the High Renaissance

In the early 16th century, Leonardo da Vinci surveyed Urbino’s Quattrocento fortifications. Later, Francesco Maria Della Rovere, grandson of Federico III da Montefeltro, commissioned Duke and architect Gianbattista Commandino to design a new city wall. Construction of this fourth fortification began in 1507, forming the city’s current walls. Modern techniques were used, such as strong embankments reinforcing the walls. The bastions also date back to this period.

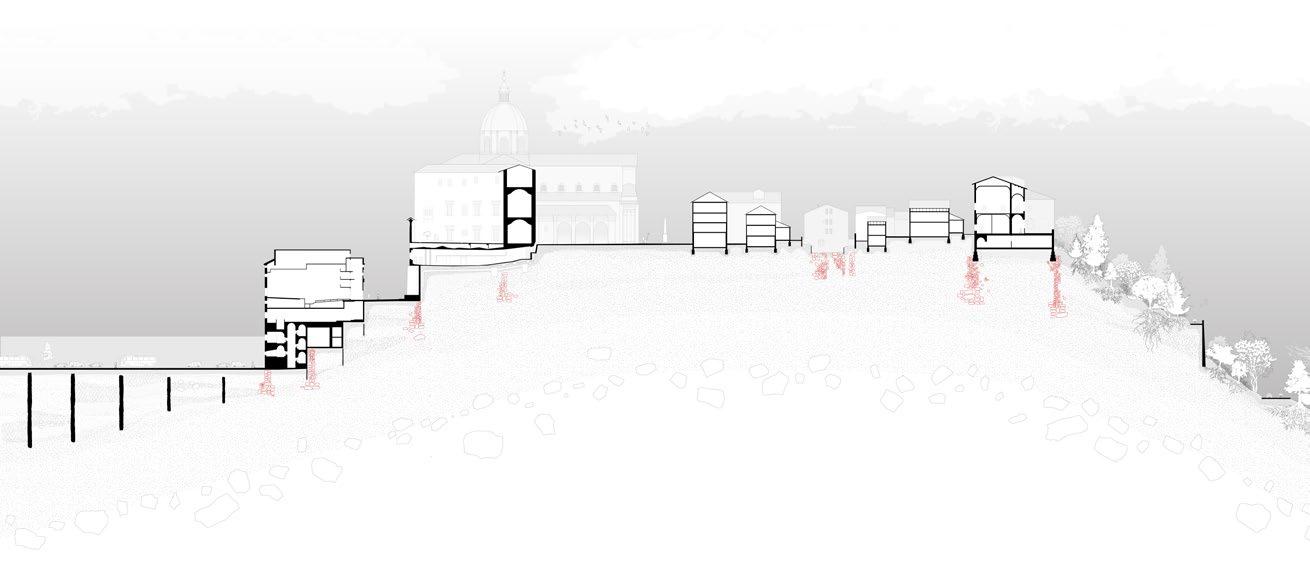

WEST EAST

West to East seaction of Urbino’s historical center Digital drawing, AutoCad + Illustrator

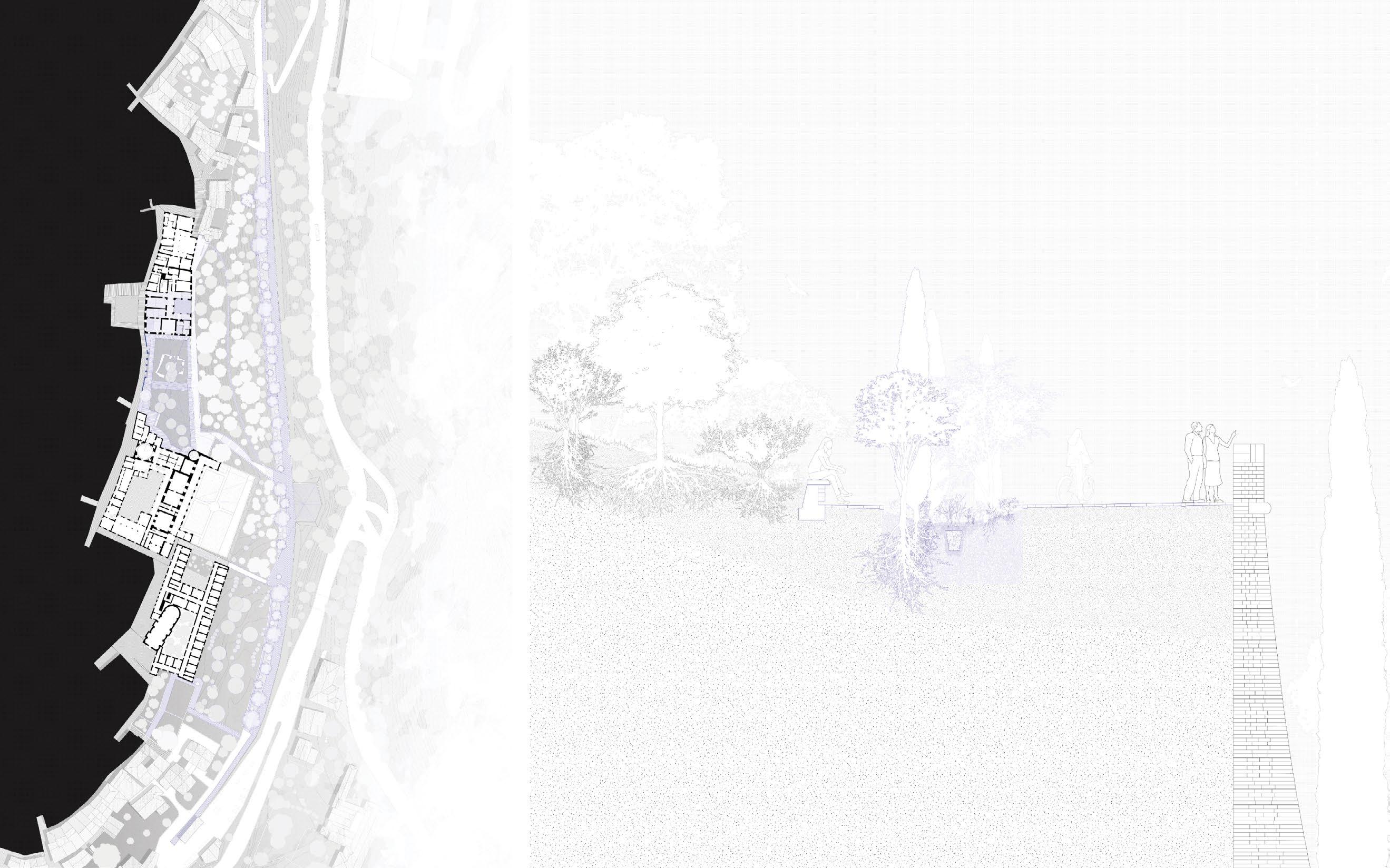

MUSEUM OF MEMORIES AND CULTURES OF FRENCH GUYANA

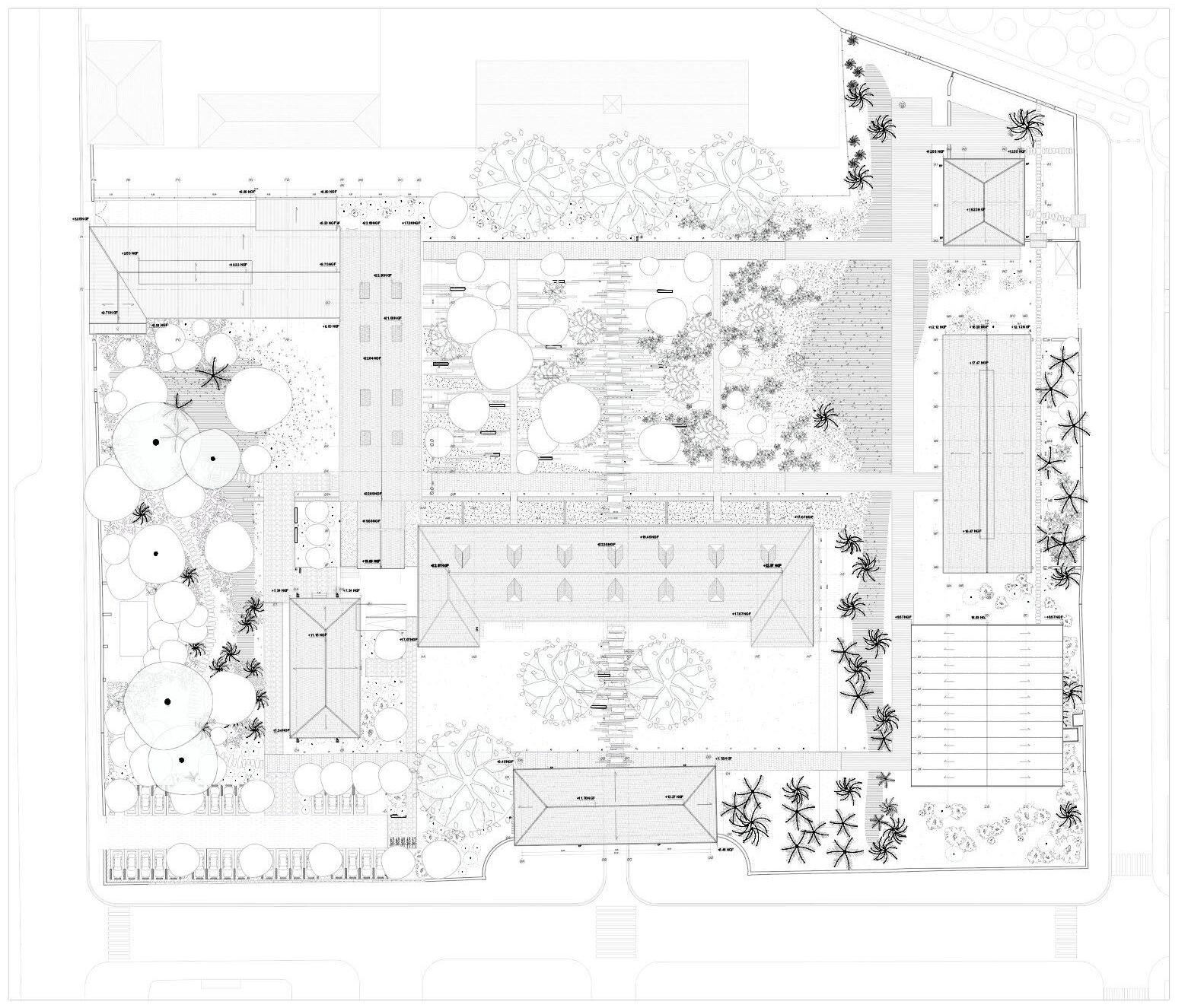

Work for Puya paysage & Urbanisme, Marseille Project leader : Tristan Geffray

Contact : tristan.geffray@puya-paysage.com

06 67 84 81 04

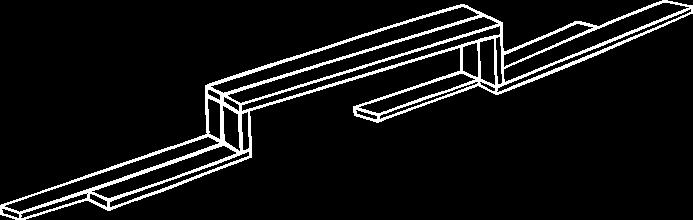

The Garden of Memories is a place of remembrance inspired by the mangrove trunks that wash up and accumulate in cycles on the beach adjacent to the museum. In keeping with the spirit of the place and the poetry of serendipity, the contemporary layout of criss-crossing and accumulating slats reinterprets this natural motif. Lying on the ground between the ocean and the hospital, these elements symbolize time, and thus the effect of the elements on a site that has marked and been marked by Guyanese history. Local trees and rocks occasionally emerge to form a shady Guyanese landscape, in which benches welcome visitors for a moment of contemplation.

Like two mangrove trunks held in balance above the others, or like a strand of weaving overlapping the other materials, the benches emerge from the ground and seem suspended in time. Contemporary irregularities in the landscape, genuine observation points that stand out from the hustle and bustle of the surroundings, their bright color also makes them stand out in the eyes of visitors in search of rest.

They are thus read as a punctuation mark, an architectural script in which those who sit down to contemplate memories and cultures become, in turn, the author.

Placed above an archaeological site, on the site of a previous colonial hospital built a few centuries earlier, the contemporary mangroves also take on a mnemonic function, updating a buried past rather than ignoring or covering it up. In this respect, the vertical superimposition and interweaving of the garden’s components is also inspired by the art of basketry. Archaeology, paths and benches now form a weave: a whole with inseparable elements.

The garden is thus a place of individual memories, traces of personal destinies, where the motifs on the ground break away from the main axis to draw multiple paths and invite you to wander, far from the strict European rationality so conducive to establishing hierarchies*. But it is also a place of collective memories, where the path to building a common Guyanese culture is symbolized by a main axis running through the center of the garden.

Rainwater management and the staging of rainwater play a direct part in the animation of the museum’s outdoor spaces. Far from being limited to an engineering subject, these spaces become places in their own right. As the linchpins linking the gardens, they offer other atmospheres, other landscapes that benefit directly from the amenities of water.

Impermeable areas have been largely de-silitarized and reduced to a minimal framework of paths and walkways. Wooden decking and grass-covered concrete paving allow rainwater to run off into the open ground. The project also includes the restoration of stone gutters at the foot of historic building facades. These will collect roof water in the valleys.

All run-off water from the roofs will be collected in the open air and channelled into the two vegetated valleys. These structures are designed to encourage retention and direct infiltration, while ensuring that excess water is channelled to outlets connected to the public sewer system outside the site. A drain at the bottom of the ditch ensures drainage when the substrate reaches saturation point.

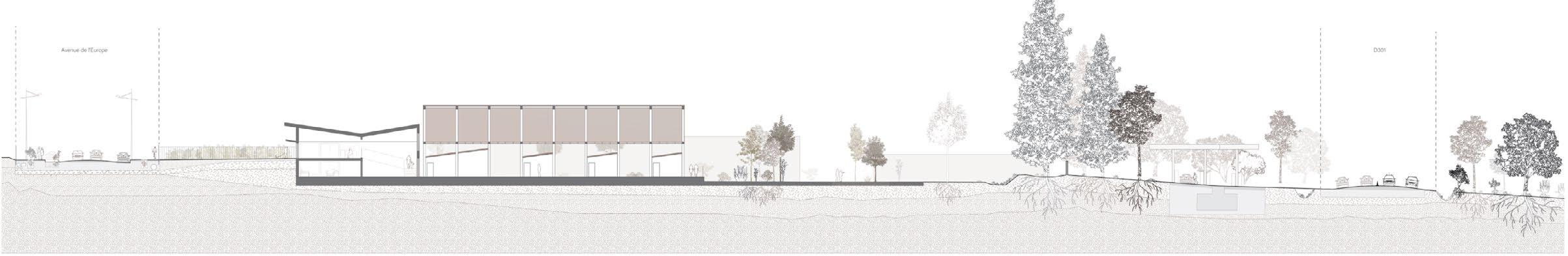

PLANETARY GARDENS

BATTERY PARK, NYC

Planetary Gardens #ARC363

University of Toronto (John. H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, landscape & design)

Instructor : Behnaz Assadi

Individual work

Two environmental stories : ecological density versus urban density

Examining the history of Battery Park brought me face to face with the fact that New York City has always been a place of high density, in one form or another. On the one hand, its geography at the heart of the Hudson estuary makes it an ecologically productive environment. It’s teeming with life as it retains all the nutrients from the watersheds. On the other hand, as soon as they arrived in 1609, the Dutch colonizers began centuries of shared rituals of land shaping and commodification, which have resulted in the dense urban environment we know today. Battery Park, through events such as the land reclamation of 1850, symbolizes our reckless aspiration to unlimited growth, despite all the challenges it poses. The very shoreline of today’s park is the result of a commercial desire.

Economic desire in the grand ecological narrative

Yet Battery Park cannot escape the effects of anthropogenic climate change, as the events of Hurricane Sandy have shown. Thus, the growing concentration of people, goods and infrastructure also means that the potential for loss in this area is high and increasing. I thus realized that it is rather this economically desirable land that is being inserted into the grand ecological narrative of the Anthropocene, and not the other way around. A point of view that can reverse the hierarchy of narratives. Global warming of our atmosphere is simultaneously inducing 2 climatic phenomena that affect Battery park: The first is rising sea levels (because the ice caps are melting into the oceans, which are also increasing in volume as temperatures rise). The second is an increase in precipitation, as air’s capacity to transport moisture is proportional to its temperature. By 2100, the park’s current condition will be seriously compromised by storm flooding, rising water tables and runoff flooding. More importantly, due to the global rise in sea level (which in New York is rising twice as fast as the global average), by 2050 the tides will rise above the current pier and flood the park on a daily basis.

project plan

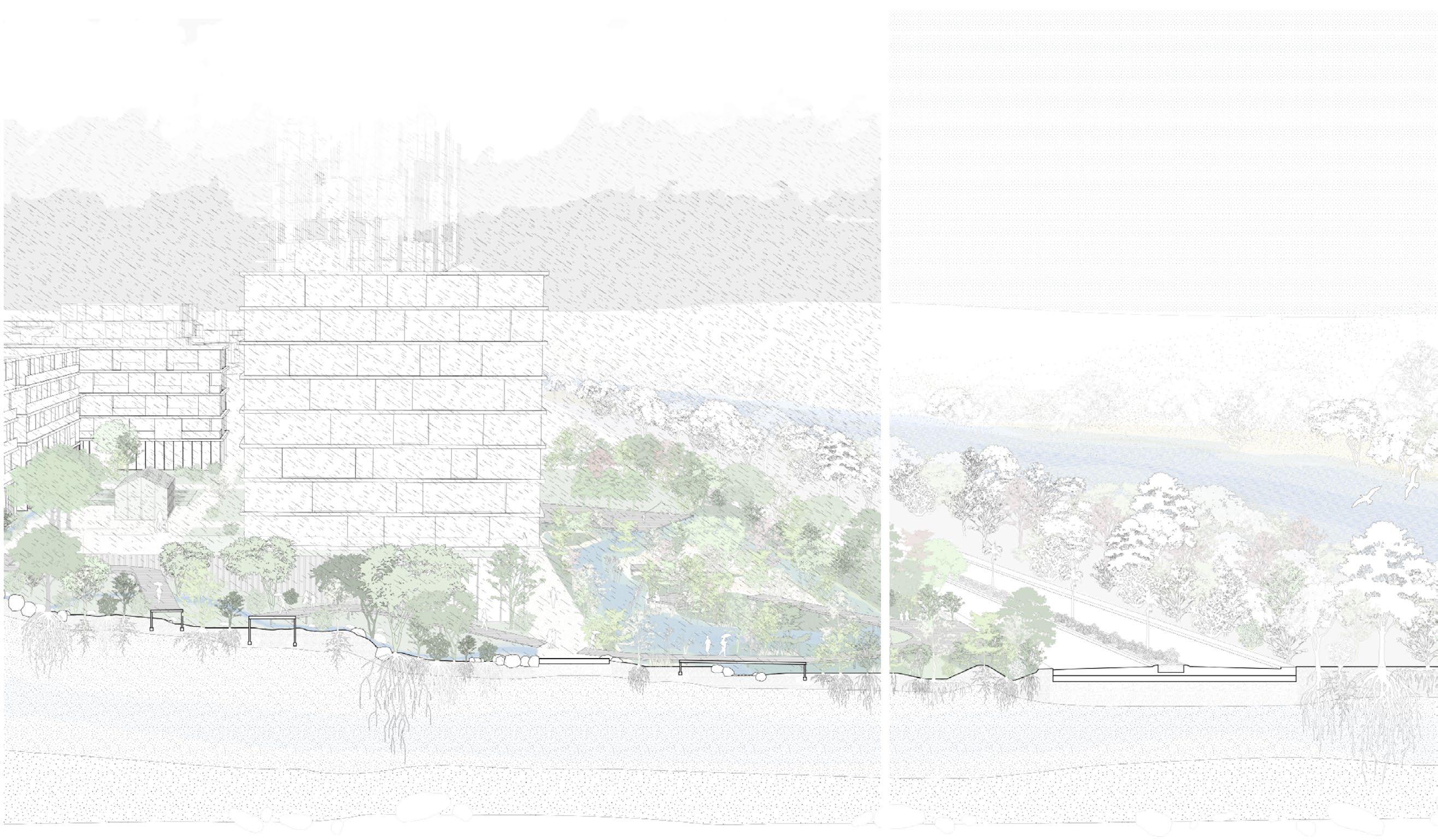

WATER LANDSCAPES

SAINT-LAURENT-DY-VAR, FRANCE

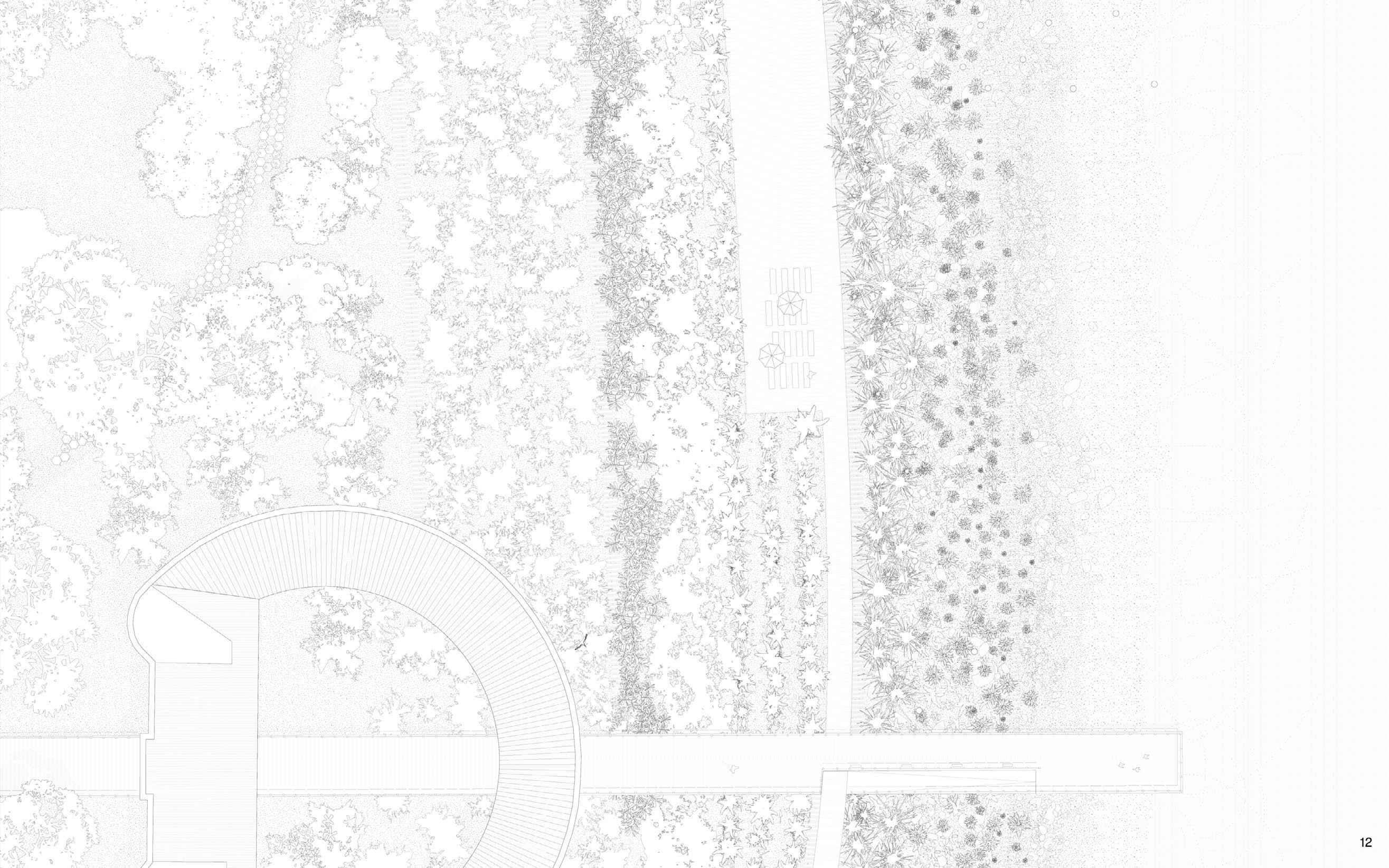

Work for Puya paysage & Urbanisme, Marseille

Project leader : Tristan Geffray

Partners : Kathleen Rabaste

Contact : tristan.geffray@puya-paysage.com 06 67 84 81 04

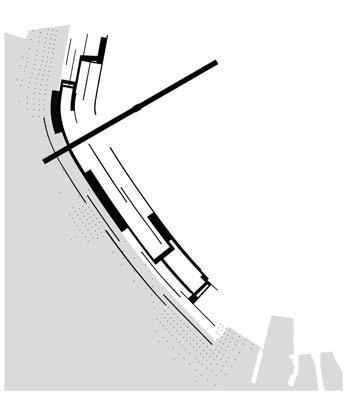

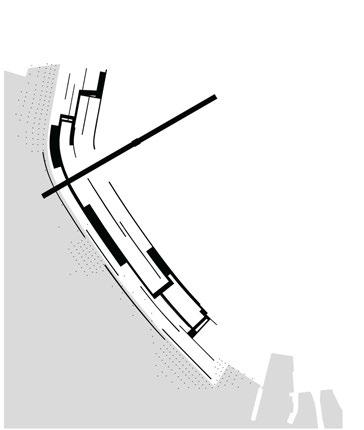

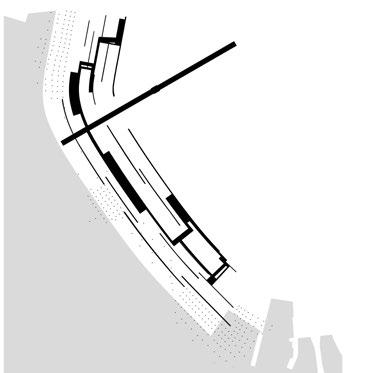

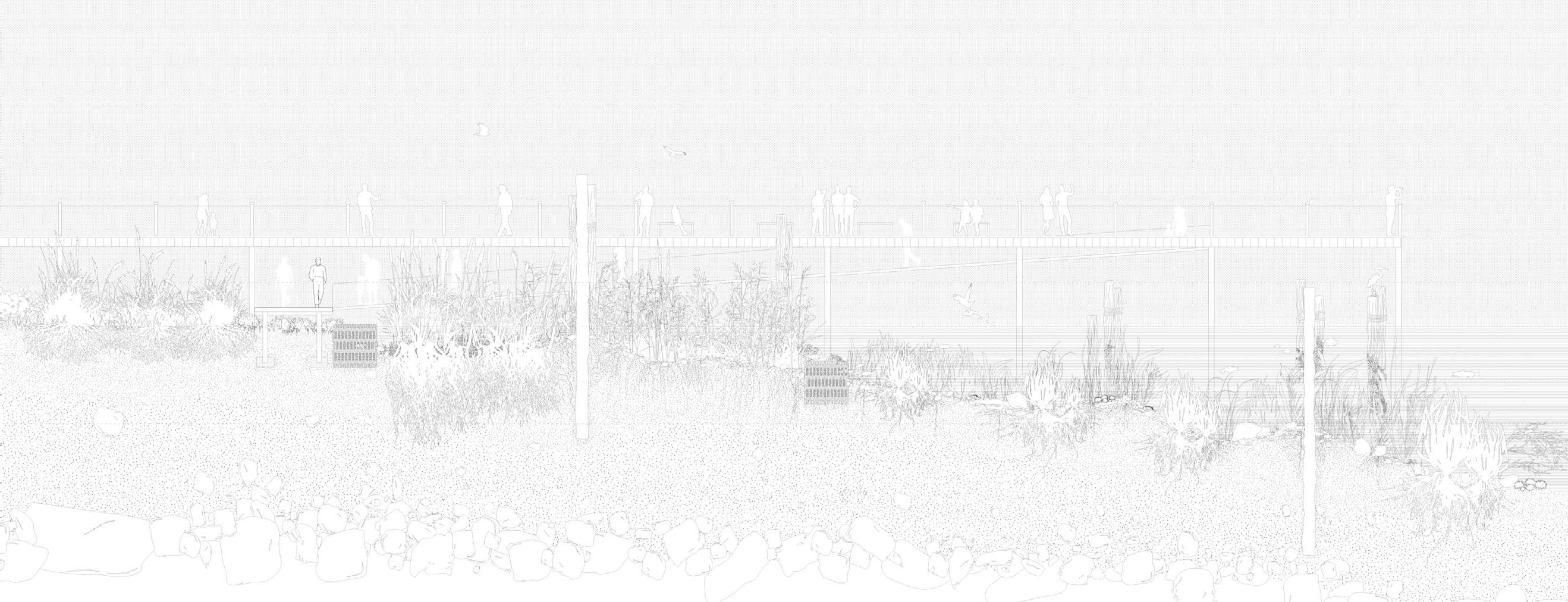

The project transforms the Var’s riverside into a bold urban landscape that seamlessly integrates water management and city life. Buildings are set back into the natural slope, creating a unique transition zone that embraces the river while reclaiming the waterfront for people. This reimagined space offers not just protection against floods but a new way for residents to engage with their environment.

At its core, a 1.3-hectare park serves as both an ecological asset and a vibrant community space, redefining the riverbanks. The district will feature 400 bioclimatic homes, 3,000 m² of commercial space, and pedestrian-friendly streets that prioritize movement and connection. Designed with the future in mind, the project addresses the realities of climate change by weaving sustainability, livability, and innovation into every detail, creating a neighborhood that’s as functional as it is inspiring.

project section Digital drawing, AutoCAD + Illustrator

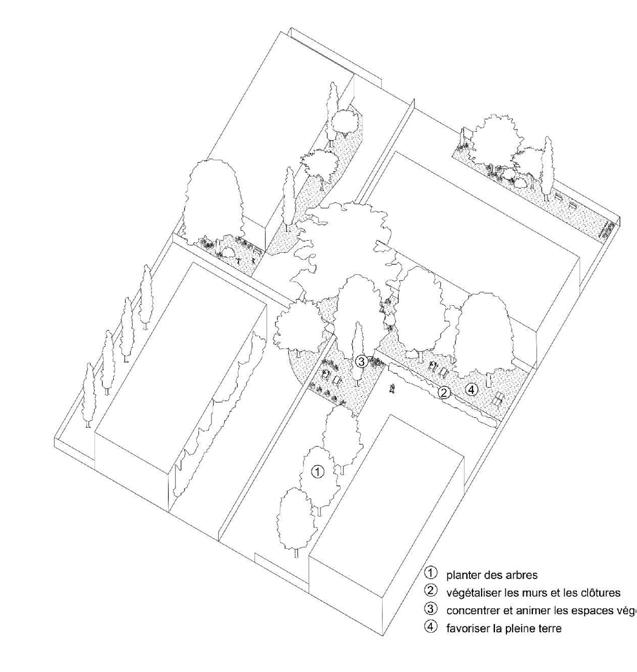

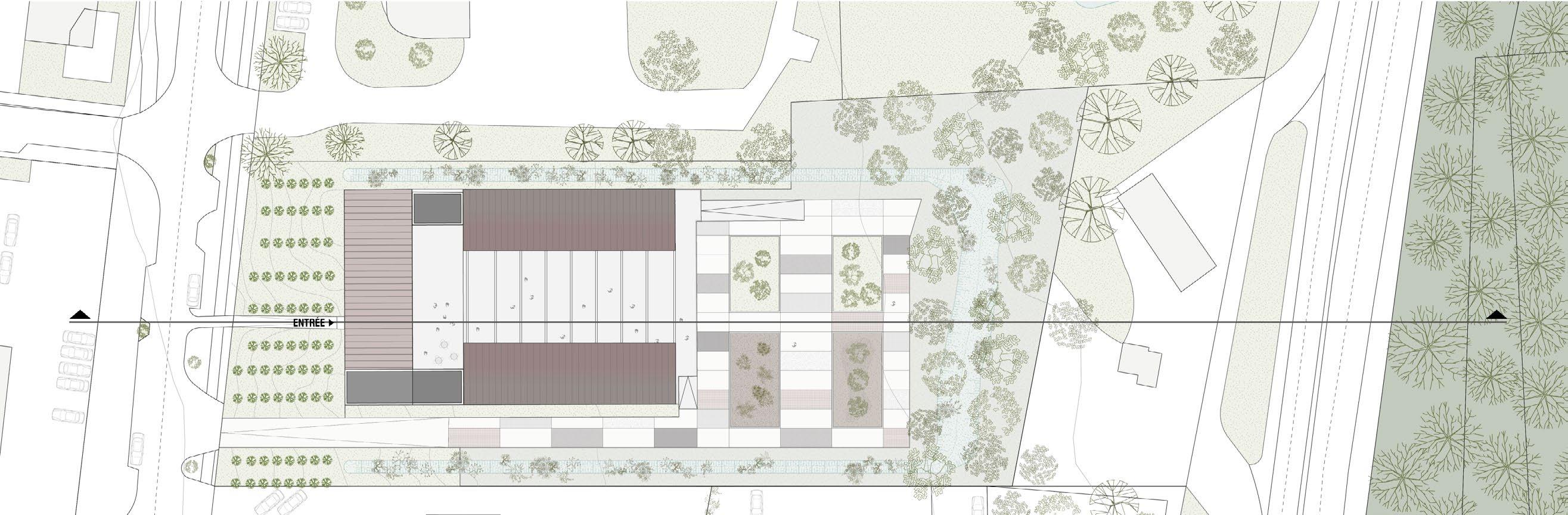

PARIS’

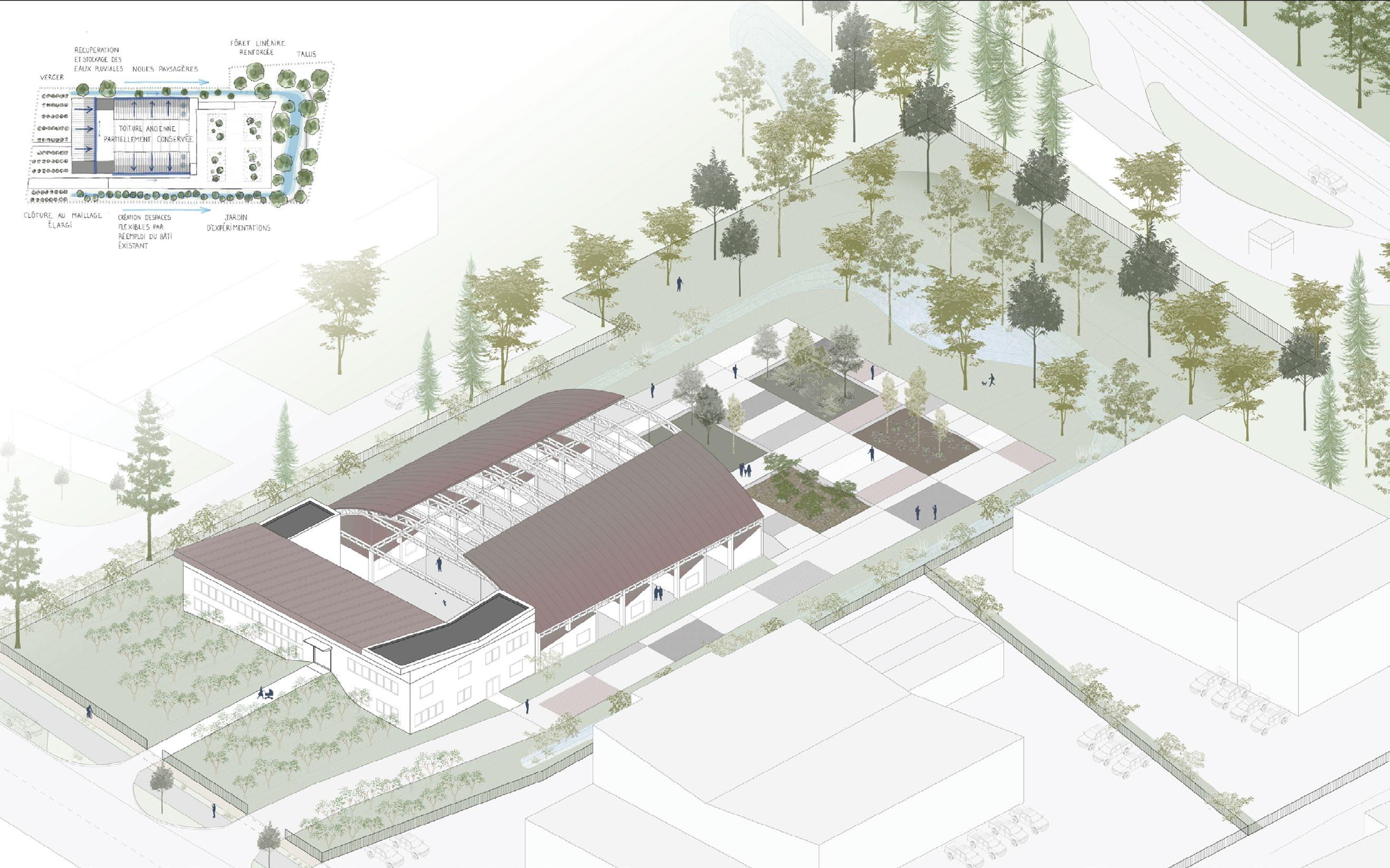

A GREENING STRATEGY FOR OBSOLETE BUSINESS PARKS

Studio Interfaces métropolitaines

Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville

Instructor : Frédéric Bertrand

Partner : Alexandra Chenevard

From Paris to Domont : a sustainable approach to our living spaces

We were inspired to carry out the diagnosis and determine the project’s orientations by our understanding of the regulations and their ability to reveal and support the area’s intrinsic potential. Indeed, we hypothesize that the attractiveness of a place can be quantified by its capacity to create and maintain social links thanks to the qualities specific to the territory in which it is located. A key lever for achieving these objectives is Plaine Commune’s OAP (Orientation d’Aménagement et de Programmation)

Santé et Environnement. By combining the concept of “foyers” with the principles defined by the OAP, we are imagining a new type of sustainable neighborhood.

project

IN BETWEEN THE FACADES STADTMOSAIK, BERLIN

Studio Aller Hand, MVRDV

Technische universität Berlin

Instructor : Jacob Van Rijs

Partners : Valesa Petkova, Lisa Koss, Theo Osterhage, Kateryna Vorozhbyt

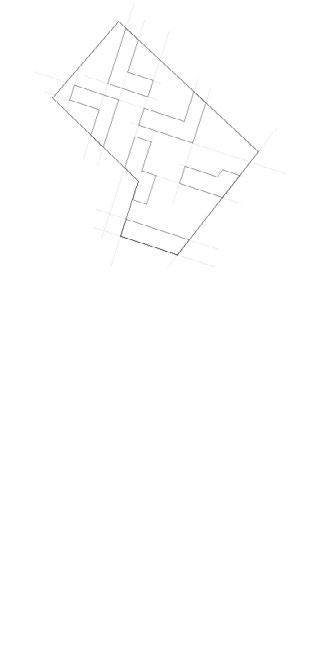

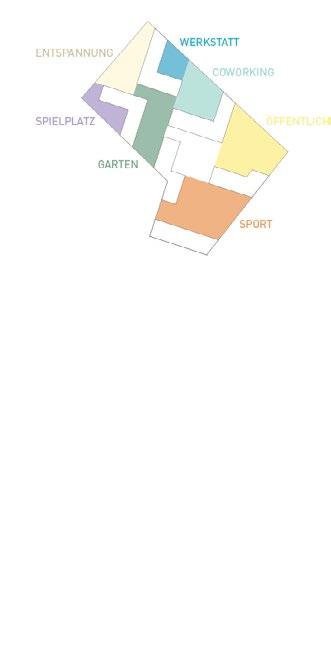

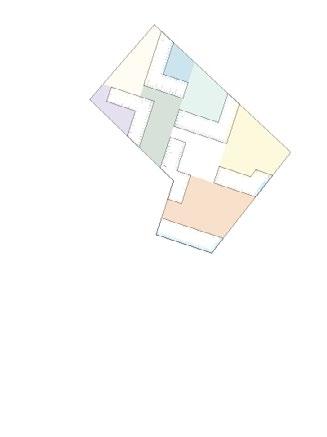

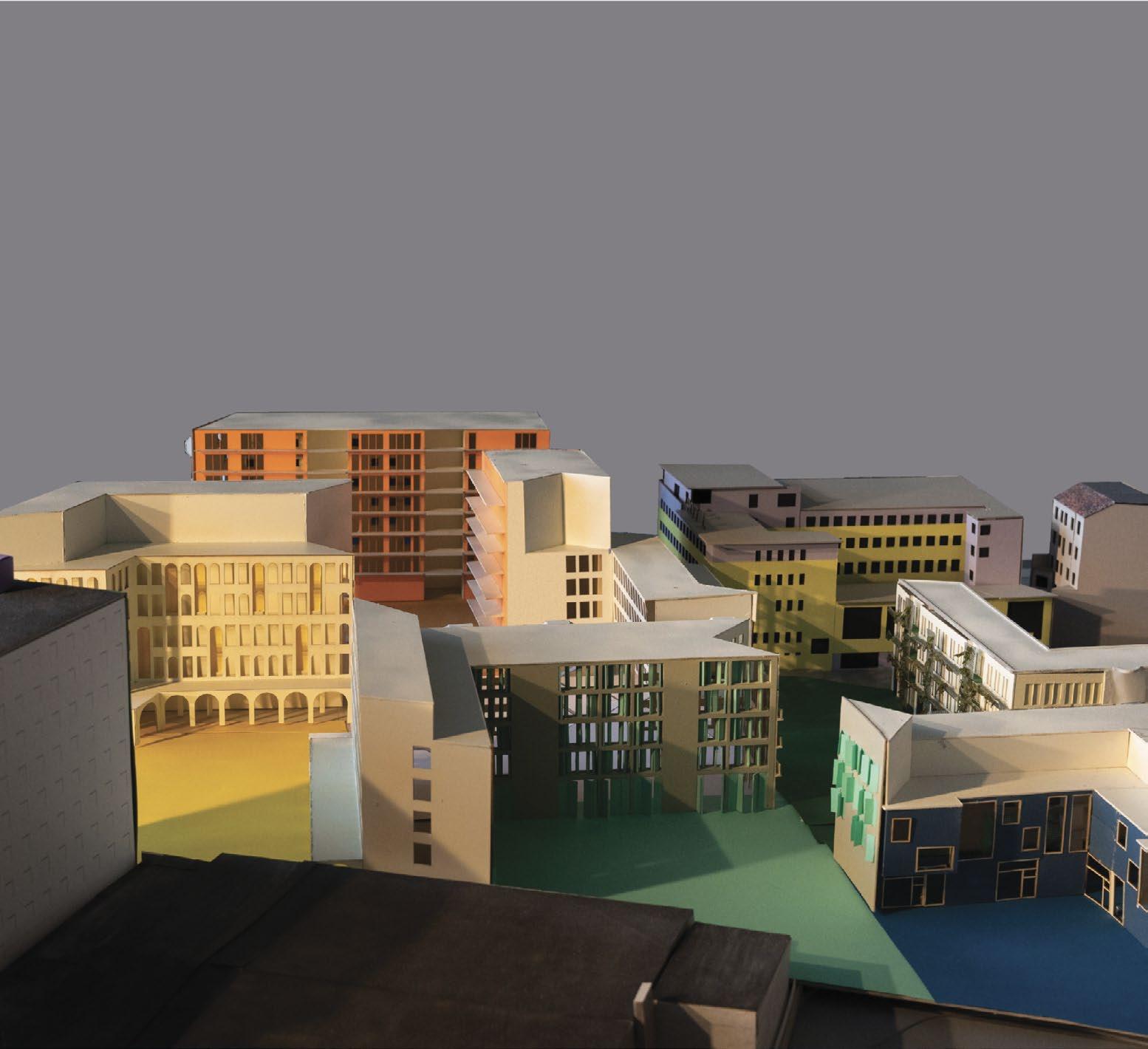

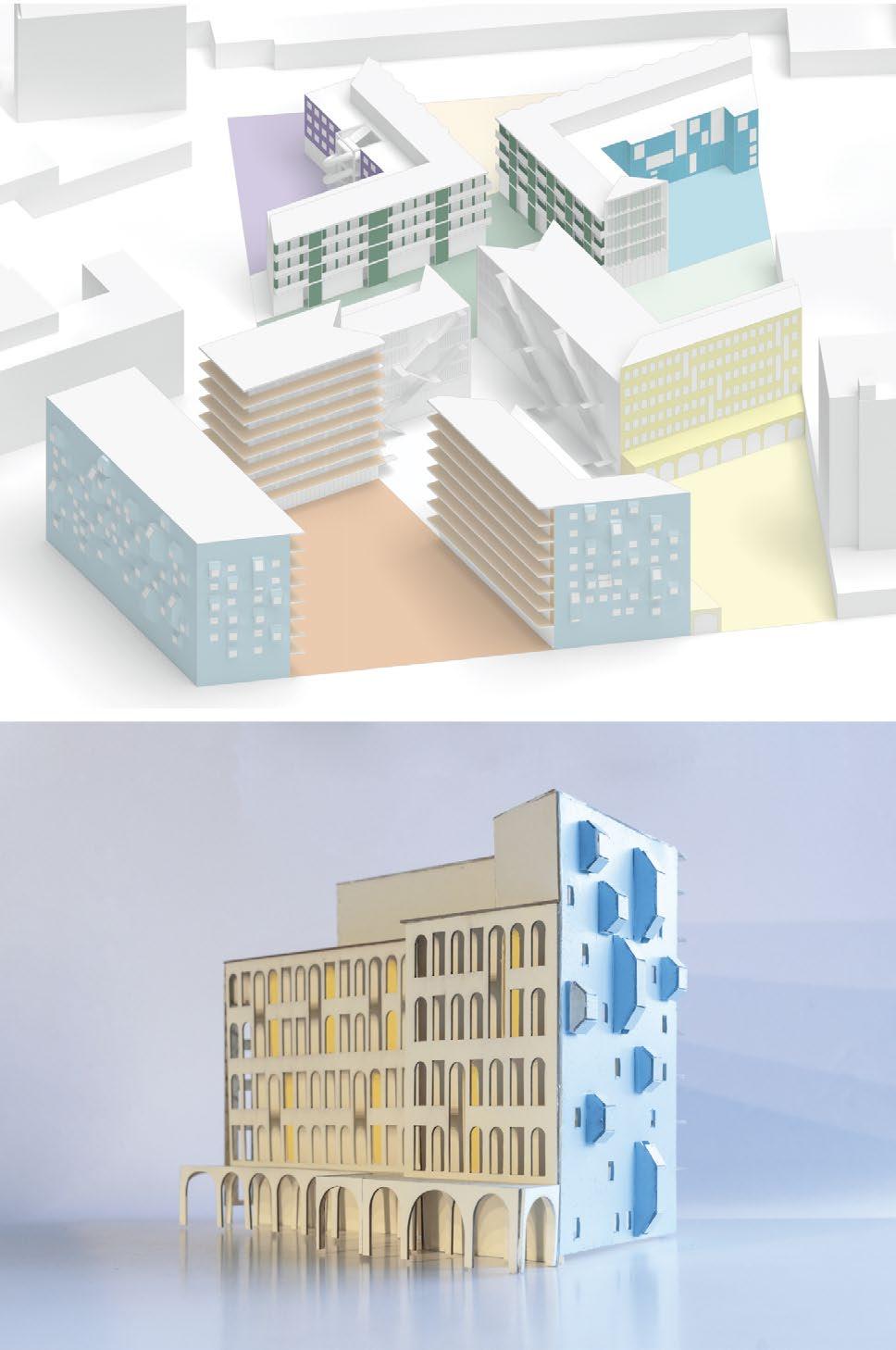

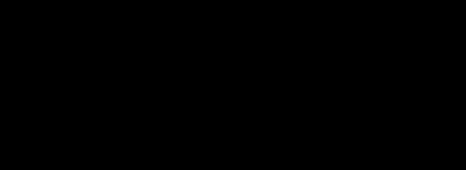

The Stadtmosaik project focuses on the spaces between facades, both inside and outside buildings, as vital areas of interaction and connection. The design process begins with the architecture of the buildings, shaping the surrounding spaces to emphasize their communal and functional roles.

Inspired by the diverse and multicultural character of Berlin’s Hochstraße district, the project envisions the urban environment as a mosaic—many unique pieces forming a vibrant whole. Courtyards, defined by extending existing sightlines, are central to this vision. Each courtyard has a distinct identity and serves specific communal purposes, such as playgrounds, relaxation areas, sports fields, public squares, gardens, coworking spaces, and workshops.

Stadtmosaik redefines urban design by prioritizing the “in-between” spaces, creating opportunities for connection and fostering a strong sense of community.