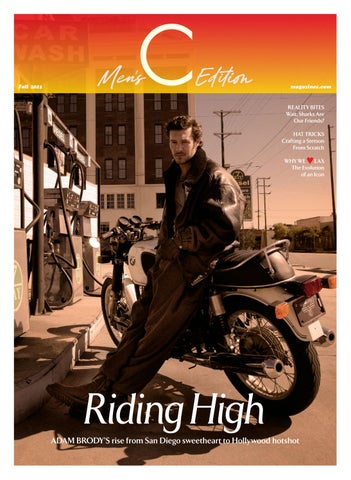

Riding High

BRODY’S rise from San Diego sweetheart to Hollywood hotshot

BEVERLY HILLS SAN FRANCISCO SOUTH COAST PLAZA

THE SHOPS AT CRYSTALS VIA BELLAGIO SHOPS

RIVER OAKS DISTRICT HIGHLAND PARK VILLAGE

ME N'S

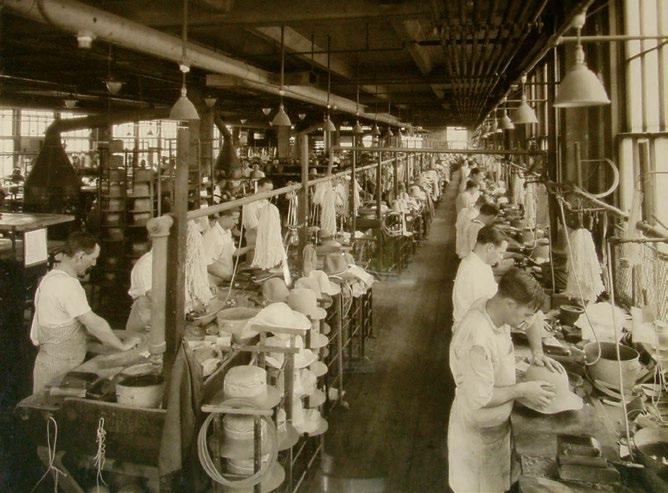

40. At Stetson headquarters, one writer witnesses the creation of a cowboy hat

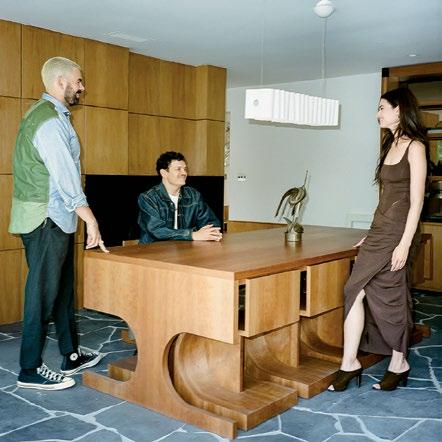

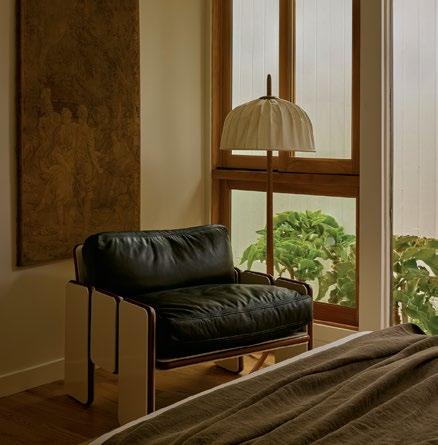

In Laurel Canyon, three designer friends resurrect a mid-century house with aplomb

Gucci

Giorgio Armani Tie, $225,

Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello Tie, $300, ysl.com —R.R.

$7,200, iwc.com

$36,850, tagheuer.com Harry Winston Price upon request, harrywinston.com

$9,830, chopard.com

$7,900, omegawatches.com

$5,600, breitling.com —R.R.

Founder’s Letter

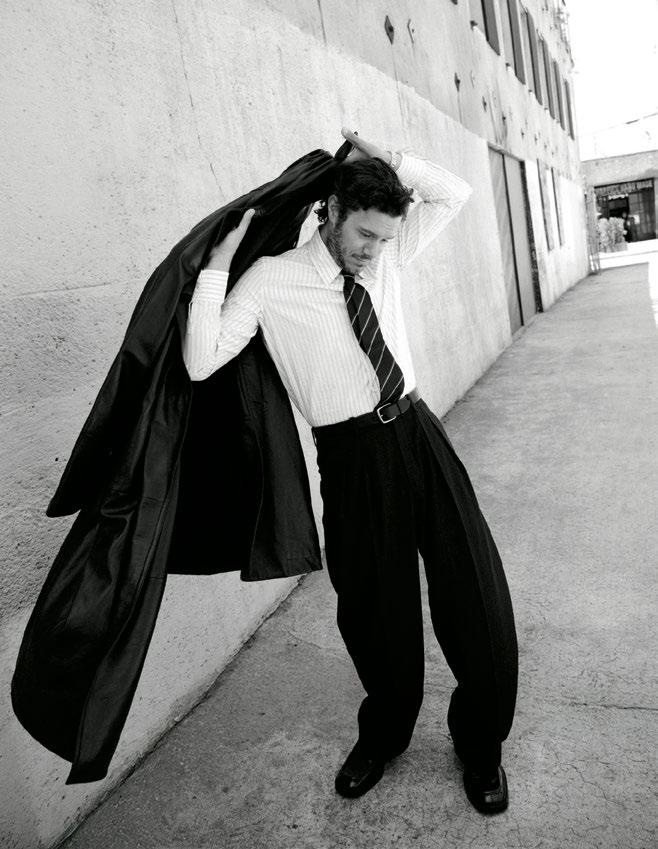

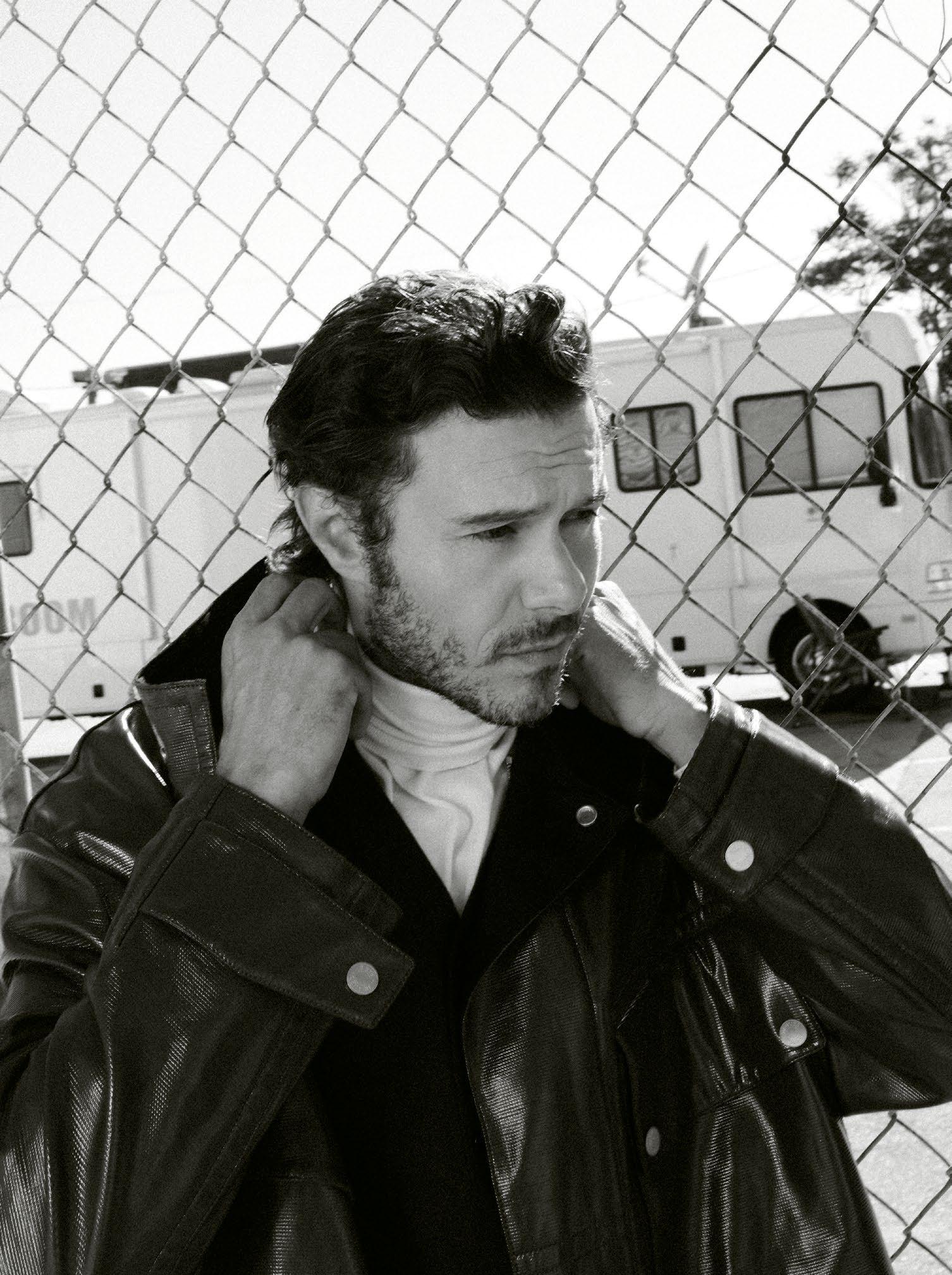

Shooting Adam Brody for this issue’s cover felt inevitable — he is, after all, the quintessential California son. Born in San Diego, raised with a surfboard under his arm, and plucked young for his breakout in The O.C., his story is as Cali as it gets. I’ve loved watching his path wind through indie films and sharp TV turns, but it was as the unlikely heartthrob in Nobody Wants This that he reminded us why we first fell for him. He’s smart, sexy, and reassuringly familiar — a rare combination that feels like home.

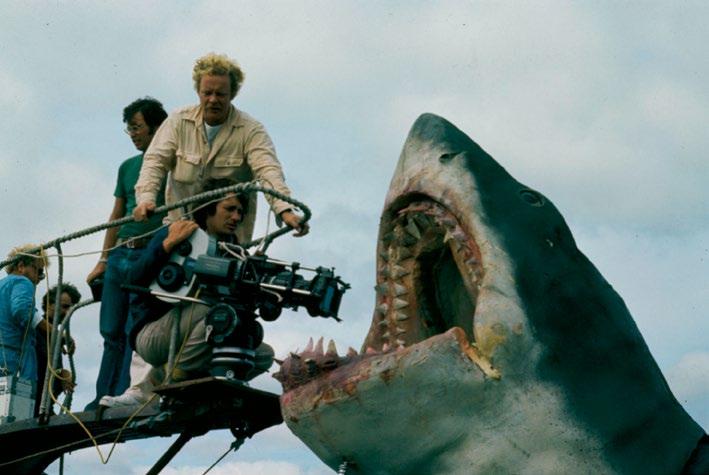

What doesn’t feel safe? Sharks. And on the 50th anniversary of Jaws, we dive deep into the myths and realities of the ocean’s most misunderstood predators, giving them the Hollywood treatment they deserve. Almost as iconic, the Stetson hat — shorthand for grit and cool — gets its close-up too, as we trace how these legendary toppers are still crafted today.

Taken together, these stories — and so many more in this issue — circle back to authenticity: in careers built with staying power, in craftsmanship honed by hand, and in nature’s wild, unvarnished truth. That, we think, is something worth living by.

Jennifer Smith Founder, Editorial Director and CEO

Jack Waterlot

French lensman Jack Waterlot shot our cover and feature on Adam Brody, “Hot Rabbi, Cool Head” (p. 28). He has been taking photographs since he was a teenager in Paris. In his early 20s he moved to Topanga Canyon before heading to the East Coast, where he began to shoot some of the world’s most iconic faces in fashion, music, and film for global brands and publications, including Tom Ford, Roberto Cavalli, Vogue, W, and Numéro

C People

Ilaria Urbinati

Ilaria Urbinati is an Italian-born, Parisianraised fashion stylist residing in L.A. Her work with celebrities regularly lands her on The Hollywood Reporter’s “Most Powerful Stylists.” She has partnered with Porsche, Walmart, and David Yurman and created capsule collections for Eddie Bauer, Montblanc, Percival, London Sock Company, and many more. For this issue, she styled the cover and feature on Adam Brody, “Hot Rabbi, Cool Head” (p. 28).

Jay Fielden

Jay Fielden, whose “The Making of an Icon” (p. 40) is excerpted from Stetson: American Icon (Rizzoli, $100), is a former editor of Esquire and Town & Country. He has published investigative journalism and poetry in The New Yorker and is currently working on several ongoing editorial projects with Ralph Lauren, including Polo, a large format newspaper. Growing up in Texas, he encountered cowboy hats on an almost daily basis.

Degen Pener

Degen Pener, who penned “Sharks: A True Story” (p. 36), is a writer and editor based in West Hollywood who covers environment, design, and culture stories. He was most recently the deputy editor of The Hollywood Reporter, where he oversaw style, lifestyle, e-commerce, and culture coverage. He has previously written for The New York Times, Out, InStyle, Entertainment Weekly, Elle, Details, Wallpaper, Veranda, and New York Magazine

SMITH

Editor & President JENNY MURRAY

VIVIANNE LAPOINTE

TOLLESON ELIZABETH VARNELL

Publisher RENEE MARCELLO

Executive Director, West Coast SUE CHRISPELL

Director Digital, Sales & Marketing AMY LIPSON

Information Technology Executive Director SANDY HUBBARD

Sales Development Manager ANNE MARIE PROVENZA Controller LEILA ALLEN

Contributors

MAX BERLINGER, ROB HASKELL, MARTHA HAYES, DAVID NASH, DEGEN PENER, REBECCA RUSSELL, ELIZABETH VARNELL, S. IRENE VIRBILA, JACK WATERLOT

C PUBLISHING 2064 ALAMEDA PADRE SERRA, SUITE 120, SANTA BARBARA, CA 93103

T: 310-393-3800 SUBSCRIBE@MAGAZINEC.COM MAGAZINEC.COM

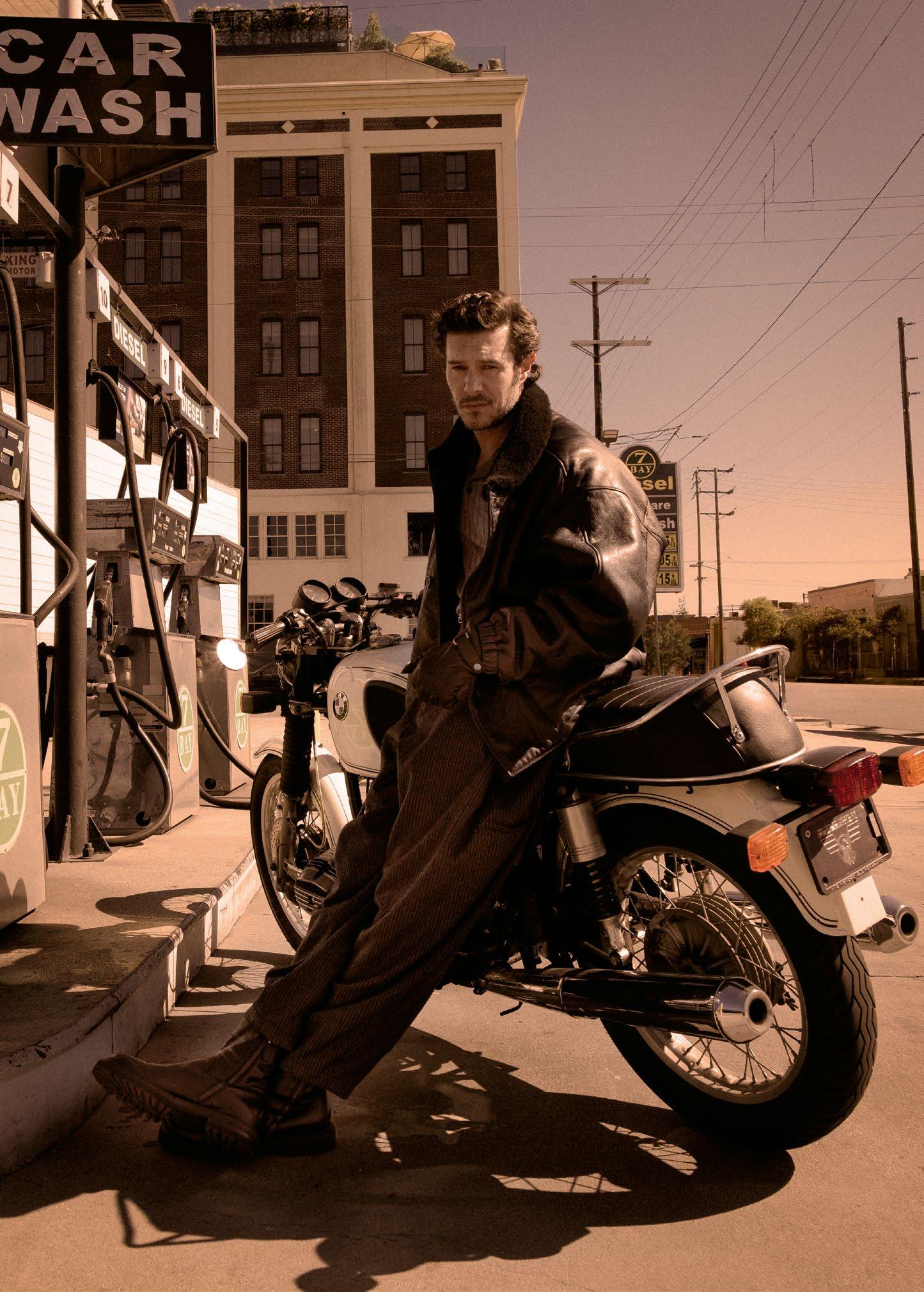

BRODY wears GIORGIO

shirt, $1,095, pants, $3,495, boots, $2,295, gloves, $845, and jacket, price upon request.

Photography by JACK WATERLOT. Styling by ILARIA URBINATI. Grooming by KIM VERBECK at The Wall Group.

ADAM

ARMANI

BEVERLY HILLS SOUTH COAST PLAZA WYNN LAS VEGAS

Italian-Style

The family-run Italian tailoring maestros at CANALI (beloved by celebrities like George Clooney and Hugh Jackman) have a new concept for the brand’s Rodeo Drive flagship store, a manifestation of its dedication to traditional craftsmanship executed with modern finesse. The space has been architecturally reimagined to be in conversation with its surroundings, featuring double-height ceilings and oversize windows to welcome the world outside into the walls of the boutique. It also hosts a VIP lounge, complete with an Italian-style bar, and a mezzanine with an immersive atelier to bring to life Canali’s history with the sartorial art of suit-making. 261 N. Rodeo Dr., Beverly Hills; canali.com. M.B.

Mission Possible

The local legend BASIL RACUK wasn’t planning on moving; he was content humming along in semi-retirement in his 24th Street studio. But the building was showing signs of age, and this summer Racuk opened up shop in the Mission District. The new 800-sq.-ft. location features soaring ceilings and a skylight, the perfect space for his atelier-shop-gallery, where you can find Racuk’s signature pieces: architectural bags made from buttery one-of-a-kind leathers, bespoke menswear crafted from limited-run textiles, and sculptural women’s clothing evocative of mid-century designers like Balenciaga. In addition to his own clothing design, he will host shows from local artists, creating a community-focused spot for creative endeavors of all kinds. 1089 Valencia St., S.F., 415-852-8550; basilracuk.com. M.B.

CNow for the Boys

ult designer Patrik Ervell — a Northern California native known for combining gorpcore finesse with sleek luxury — has released a menswear capsule with PROENZA SCHOULER, the New York brand’s first foray into menswear. This veteran of his own brand, plus L.A.-based knitwear label Vince and minimalist British line COS, has tightly edited a collection that mixes city street toughness with a bit of laidback West Coast élan. Highlights include a simple black wool three-button suit that’s both elegant and relaxed. A beefy high-collared leather

L.A. Made

“Heroism, royalty, and the street,” are the words used to describe themes in a 1983 JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT exhibition at Larry Gagosian’s Los Angeles gallery in an archival press release. The typed document, along with receipts for 13 tubes of silver acrylic paint, shirts from Maxfield, and images of nearly 30 monumental works the Brooklyn-born artist created while living at the art dealer’s Venice residence comprise a new volume chronicling his prolific California visits in the early 1980s, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made On Market Street (Rizzoli, $100). In addition to covering three exhibitions in town, the book gathers candid photos, newspaper clippings, essays, and a conversation among the gallerist, filmmaker Tamra Davis, curator Fred Hoffman, and the artist’s sisters. rizzoli .com E.V.

jacket with dropped sleeves is made for tossing over a tee while dining alfresco in Malibu or Venice. Other top picks are a cobalt blue button-up shirt; an earthy brown wool officer’s coat; classic crewneck sweaters cut in a loose silhouette woven from yak wool and offered in oatmeal, navy, and acid green; and bleachedout denim, each dyed to be a one-of-a-kind piece. Oh, and the brand’s elevated, urbane take on the crunchy double-strap Birkenstock Arizona sandal, with topstitched details and offered in burgundy or silver. A Cali classic if ever there were one. proenzaschouler.com. M.B.

Spritz Springs

The new BAR ISSI at the Thompson hotel in downtown Palm Springs, designed by Fettle, sports a vivid palette, curvaceous banquettes, and wallpaper with dancing crocodiles. The menu is more sedate, filled with easygoing dishes you might find on the Italian coast. Nibble on oysters and crudo, squash blossoms with ricotta and lemon, crispy octopus with smoked paprika, or shrimp linguini sparked by Calabrian chili. A wood-fired pizza oven turns out seasonal pies, and mains include roast chicken, branzino with preserved lemon, chops and steaks, and proper shoestring potatoes. Be sure to order the Italian spritz of Prosecco with blood orange juice and cardamom. 414 N. Palm Canyon Dr., Palm Springs, 442-334-2405; thebarissi.com S.I.V.

November, a dream flight to Kahului commences. Complete with dishes from Spago and Hawaii-inspired fare from L.A. grocer Erewhon, as well as craft cocktails and spa-like flight essentials, the trips take place aboard AERO’s 12-passenger Gulfstream-IV planes. The jet service is based at Van Nuys Airport, where private terminals welcome travelers and their pets. Skip the endless lines to check surfboards, golf bags, and gear while flying direct to central Maui, opting instead for curbside check-in 20 minutes before takeoff, which still allows for oversize bags to be stowed. To launch the new route, Aero is collaborating with the Four Seasons Resort Maui at Wailea on getaways that include last-minute access to rooms, priority dining reservations, and a host of other perks. The waves await. 323-745-2376; aero.com. E.V.

IWC Ingenieur. Form und Technik.

Ingenieur Automatic 42, Ref. 3389

Registering a hardness of around 1300 HV on the Vickers scale, zirconium oxide ceramic is one of the hardest materials on earth. It can be machined only with diamond-tipped tools and is virtually scratchproof. All of which is good news for you, of course, but less so for us. Because machining and manufacturing a watch made entirely of ceramic is unimaginably complex and demanding. The good news, however, is that our engineers have been working with ceramics since 1986. So, you can rest assured that when it comes to the Ingenieur Automatic 42, we leave absolutely nothing to chance. IWC. Engineered.

IWC Boutique · South Coast Plaza

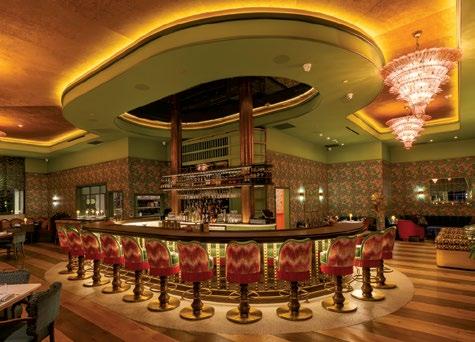

Winter Whites

From Aspen’s peaks to Tahoe’s shores, layer up in luxurious fabrics and snow-ready accessories

Omega Watch, $5,800, omegawatches.com

Loro Piana Jacket, $4,740, loropiana.com

Pants, $1,400, celine.com

Veneta

$8,700, bottegaveneta.com

Edited by REBECCA RUSSELL

Balenciaga Sunglasses, $575, balenciaga.com

Zegna Turtleneck, price upon request, zegna.com

William Henry Necklace, $595, williamhenry.com

Moncler Boots, $1,010, moncler.com

Celine

Bottega

Bag,

Canali Scarf, $595, canali.com

Flight Plan

Imagine your commute if you were able to avoid rush-hour congestion. A drive that might take a half an hour on a good day will literally fly by in four minutes with your own PIVOTAL HELIX electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing (eVTOL) aircraft. The single-seat, all-electric personal aircraft is the aviation brand’s third-generation model capable of vertical landings and takeoffs. With a 20-mile range (on a full charge) and a cruise speed of 63 mph, short-distance jaunts are a breeze. Weighing just 348 lbs., the carbon fiber composite tilt aircraft can accommodate a pilot weighing up to 220 lbs. and a height of 6 feet 5 inches. And FAA Part 103 (Ultralight) category compliance for flight in Class G airspace means you don’t need a pilot license to soar above gridlock. pivotal.aero. D.N.

Skaters’ Paradise

The hippie-meets-skater outdoors brand 18 EAST, which focuses on crafts and textiles, has popped up at the Mister Green store space along a trendy stretch in Los Feliz. The store took its cues from SoCal design; specifically, its indoor-outdoor layout and the public architecture that attracts skateboarders. The result is utilitarian chic: concrete floors and plywood shelving host the complete seasonal collection — think roomy pants, oversize button-ups, and retro outerwear, plus exclusive items like skate decks, a tote bag, and graphic T-shirts. Ceramics are courtesy of Shoshi Watanabe, a friend of the brand. The pop-up is slated to end in November, but 18 East designer Antonio Ciongoli says he’s open to finding a more permanent location. Here’s hoping. 3019 Rowena Ave., L.A.; 18east.co. M.B.

Cocktails & Chilaquiles

Tucked under the A line train tracks in Chinatown, Mexico City–inspired CAFÉ TONDO dispenses freshly made cafe de olla scented with piloncillo sugar and cinnamon starting at 8 a.m. A charming wooden pastry case displays festive conchas and moist pan de elote made with fresh corn, and spirals of the coveted cardamom buns from Clark Street Bakery. Stroll through the series of small indoor-outdoor rooms for your spot to enjoy chilaquiles topped with two fried eggs or masa-laced hot cakes.

At 5 p.m., the evening menu kicks in, offering

marinated olives, skewers of gildas, fries with the house aioli. But also empanadas and tortas of carnitas, mushrooms or milanesa, which you can order on its own with salsa verde as a main plate. The other main is skirt steak frites with chimichurri. The café is a collaboration among first-time restaurateur and Mouthwash Studios cofounder Abraham Campillo, Mike Kang of Locale Partners, and chef Luis Luna. Think of it as a home away from home where regulars drop in for a coffee and a concha, and come back at dusk for a vermouth or a bite, relaxing in the vibe of this unique space. 1135 N. Alameda St., L.A.; cafetondo.com. S.I.V.

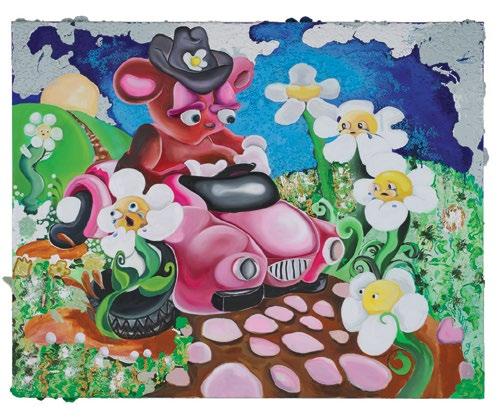

Will Rawls is traversing the HAMMER MUSEUM galleries with performances of Unmade, a series of vignettes the dancer, writer, and choreographer created for the institution’s latest biennial, Made in L.A 2025. Now in its seventh installment curated by Essence Harden, Paulina Pobocha, and Jennifer Buonocore-Nedrelow, the exhibition includes painting, sculpture, and photography, plus a mix of media by 28 artists from across the city. Sculptor and painter Alake Shilling, known for the enchanting creatures she dreams up, is also installing her work here. She and Rawls are joined by experimental filmmaker Pat O’Neill; inventor Carl Cheng, whose work explores technology, nature, and ecology; painter and muralist Alonzo Davis, who juxtaposes fragments from other cultures and his own; and many more. Each work is tied to the city, and many will inspire a second look at the streetscapes, flora, and vistas we think we know. 10899 Wilshire Blvd., L.A., 310-443-7000; hammer.ucla.edu E.V.

Strong Points

The wolf claw, a symbol of fierceness, headlines jewelry brand FOUNDRAE’s fall launches, designed to remind wearers to gird themselves and strengthen their resolve. The Protection collection, created by founder Beth Hutchens, includes a mix of white and yellow gold medallions, chains emblazoned with pavé diamond details, and onyx and malachite stones. In addition to 18-karat yellow gold La Loba Claws, there are signet rings symbolizing journeys of self-discovery and modern heirlooms with images of horseshoes, suns and moons, or numbers for personal expression. Interlocking chains hold dream medallions close to chests, while the guiding stars, divine triangles for fire and transformation, and arrows for careful aim serve as daily guides toward goals. 8405 Melrose Pl., L.A., 323-4244304; foundrae.com. E.V.

Trunking It

Fall designs for Nicolas Bijan’s by-invitation NB44 brand include pilot jackets in waterproof silk, reversible bombers in navy plaid and green silk, double-faced cashmere coats, and a handful of sport jackets that are already rolling out to members in packed trunks. The personalized edits of the made-in-Italy designs may also include peak lapel tuxedos and dinner jackets for upcoming galas alongside precisely shaped cotton T-shirts, silk knits, and denim jeans in an assortment of colors for athletes and A-listers alike. Those in the know (7,000 and counting), whose annual $12,000 membership fee gives them access to this convenience, can select wardrobe additions each season through a private digital platform launched in 2023, and they have the option to add new silhouettes to closets or send items back in the trunks. New members are admitted by referral. nb44.com. E.V.

French Pressed

The secret to Gallic flair is minimal effort but maximum refinement

Hermès Loafers, $1,575, hermes.com

Burberry Coat, $5,490, burberry.com

Ford

$150, tomford.com

prada.com

Van Cleef & Arpels Watch, $173,000, vancleefarpels.com

ralphlauren.com

by Anthony Vaccarello

$1,600, ysl.com

Ring, $4,800, zahnzjewelry.com

Edited by REBECCA RUSSELL

Polo Ralph Lauren Sweater, $148,

Saint Laurent

Pants,

Zahn-Z

Tom

T-shirt,

Prada Briefcase, $4,800,

Balenciaga Glasses, $490, balenciaga.com

Brunello Cucinelli Fall 25

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S ULTIMATE SHOPPING DESTINATION

A. LANGE & SÖHNE

ACNE STUDIOS

AMIRI

AUDEMARS PIGUET

BALENCIAGA

BALMAIN

BERLUTI

BOTTEGA VENETA

BRUNELLO CUCINELLI

CARTIER

CELINE

CHOPARD

DIOR MEN

DOLCE&GABBANA

ELEVENTY

FENDI

GENTLE MONSTER

GIORGIO ARMANI

GOLDEN GOOSE

GUCCI

HERMÈS

HUBLOT

JACQUES MARIE MAGE

JAEGER-LECOULTRE

LORO PIANA

LOUIS VUITTON MEN’S

MAISON MARGIELA

MONCLER

OMEGA

PANERAI

PATEK PHILIPPE

PORSCHE DESIGN

PRADA

ROGER DUBUIS

ROLEX | BUCHERER 1888

SAINT LAURENT

THE WEBSTER

THOM BROWNE

VACHERON CONSTANTIN

VERSACE

ZEGNA

partial listing

In the Club

Mei Lin is making another grand entrance at 88 CLUB in Beverly Hills, a swanky Chinese bistro where she’s using a deft modern touch with the comfort dishes she once ate and cooked at her family’s restaurant. Start with the jade marble lazy Susan twirling a chrysanthemum and peanut salad, sesame prawn toast, or a bowl of plump prawn and bamboo shoot wontons in a master chicken stock. Lin’s childhood favorite appears as Nam Yu roasted chicken perfumed with ginger scallion oil. Sommelier Diana Lee has constructed a food-friendly, mostly French list, and mixologist Kevin Nguyen deals in Asian flavors and turns house-made infusions into sophisticated cocktails. Order the gimlet dosed with pear brandy, shiso leaf, and bitter melon and drink to the prosperity and good fortune symbolized by the number 8. 9737 S. Santa Monica Blvd., Beverly Hills, 310-968-9955; 88clubbh.com. S.I.V.

Scaling Up

Massive folding chairs, a colossal card table, and enormous dishes stacked higher than eye level that seem ready to tip are some of Robert Therrien’s most recognizable meditations on scale and material. THE BROAD’s new show and the largest exhibition of his work to date, Robert Therrien: This is a Story, has all those immersive sculptures and much more among over 120 works spanning five decades of the L.A.-based artist’s practice. The daring dimensional pieces, realistically fabricated and often functional ordinary objects, toy with a viewer’s perspective to playful Alice-in-Wonderland effect. Minimalist drawings are also here in this deep dive that includes partial reconstructions of the artist’s studio. Nov. 22, 2025–April 5, 2026. 221 S. Grand Ave., L.A., 213-2326200; broad.org. E.V.

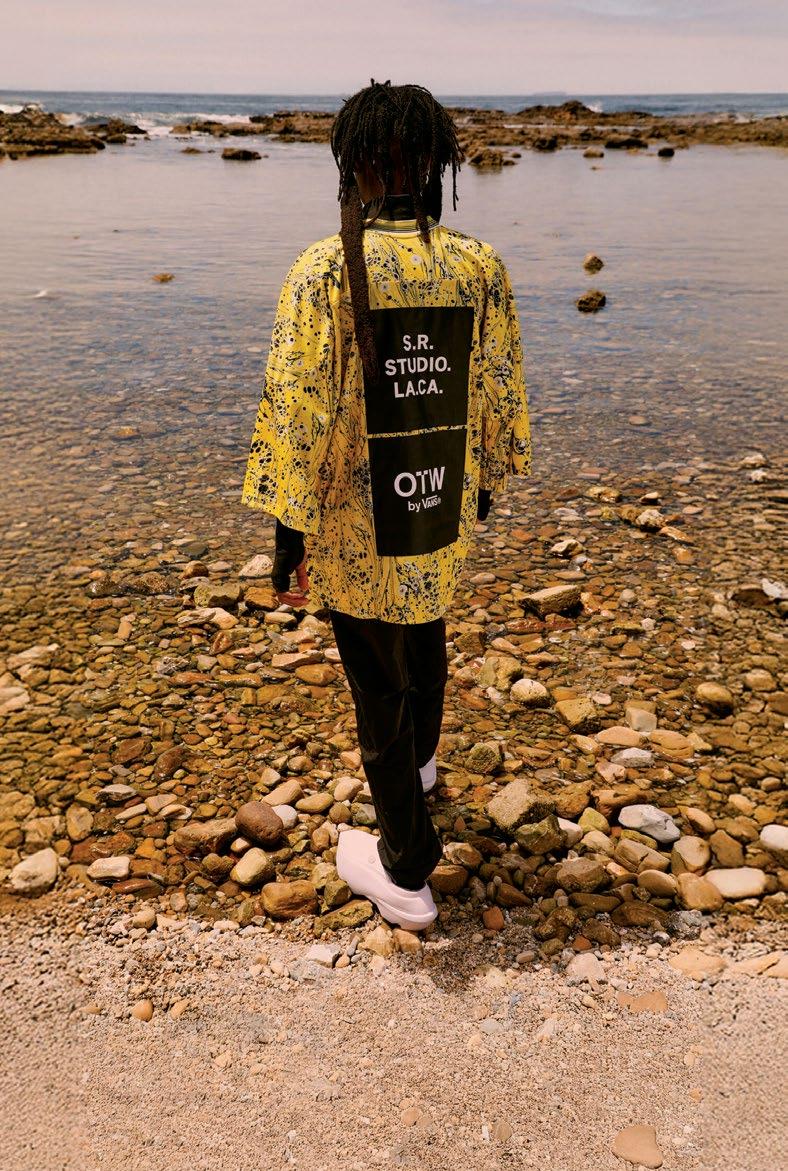

Ruby’s Slippers

Whether you have them in constant rotation or you avoid them outright, it’s time to rethink your relationship with clogs. STERLING RUBY’s new sculptural silhouette, a collaboration between his S.R. Studio LA. CA. and OTW BY VANS, is a fusion of two shoe types: mules and Dutch klompen. The functional aspect of the aerodynamic-looking kick, called FUTURE CLOG, is deeply rooted in Ruby’s family heritage. He recalls his grandfather wearing a version of the footwear in the Netherlands while making green-painted gardening

Cosmic Constant

tools in his shop. Ruby embraced the traditional characteristics while transforming them into a bolder angular shape. The L.A.-based multimedia artist, whose work is part of permanent collections at MoMA, London’s Tate Modern, and Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, launched his ready-to-wear and accessories brand after experimenting with hand-worked textiles and traditional American craft for years. His latest Vans drop also includes socks, a jersey, and a bag, all in marbled yellow, in addition to Old Skool sneakers and matching Authentic versions of the skate shoe to rule them all. vans.com. E.V.

Blackness as a source of life on earth — imagined through Mikael Owunna’s photographs of models speckled with fluorescent paints and shot in darkness, evoking celestial grandeur — is part of the transportive group exhibition Unbound: Art, Blackness, and the Universe at San Francisco’s MUSEUM OF THE AFRICAN DIASPORA. The show, which centers around the limitless possibilities of the cosmos with works by multigenerational artists, marks the museum’s 20th anniversary and spans all three floors. Key Jo Lee, chief of curatorial affairs and public programs at MoAD, organized the exhibit, which addresses metaphysical themes, creation myths, and a post-human future with paintings, collages, glass sculptures, and installations. 685 Mission St., S.F., 415-358-7200; moadsf.org. E.V.

Gold Standard

After launching eyewear and last year, BRUNELLO CUCINELLI is back with more luxe styles. For those who like to spend time on the snow-covered slopes of Mammoth or Tahoe, the brand is introducing ski goggles in bronze. Two new styles take their cues from classic Hollywood characters: a sleek engraved pair of sunglasses is inspired by Al Pacino’s character Carlito Brigante in Carlito’s Way, and a sleek rimless style pays homage to Brad Pitt’s punkish Tyler Durden in Fight Club. But perhaps the most noteworthy new style is the most opulent: the Mr. Brunello Goldcraft 1978 Edition, an existing model made in a limited run of 78 pairs, featuring 18-karat gold hardware and delivered in a special edition metal box and leather case. brunellocucinelli. com M.B.

Dior Reborn

This fall, the fabled French house DIOR is bringing its savoir faire to Rodeo Drive with a four-floor, 48,000-sq.-ft. flagship that mirrors its iconic Parisian location on Avenue Montaigne. Designed by architect Peter Marino, the store will feature a sleek white facade that opens into a sweeping central staircase that unfurls through three stories of lushly manicured gardens. The store brings together everything in the Dior universe: men’s and women’s, leather goods, home, jewelry, and fragrance — plus, at opening, items exclusive to the location, including a Beverly Hills–branded sneaker in gray and mint green and a graphic T-shirt for men. The top level will host a VIP lounge, complete with a terrace and astonishing views of Beverly Hills. It’s the perfect time for the A-list favorite to reassert itself along one of fashion’s most famous shopping thoroughfares dior.com. M.B.

From the High Desert near Joshua Tree and the far-off islands of Okinawa, two artists working in centuries-old traditions converge on the northern shore of California

Words

by DAVID NASH Photography by CHRIS GRUNDER and LESLIE WILLIAMSON

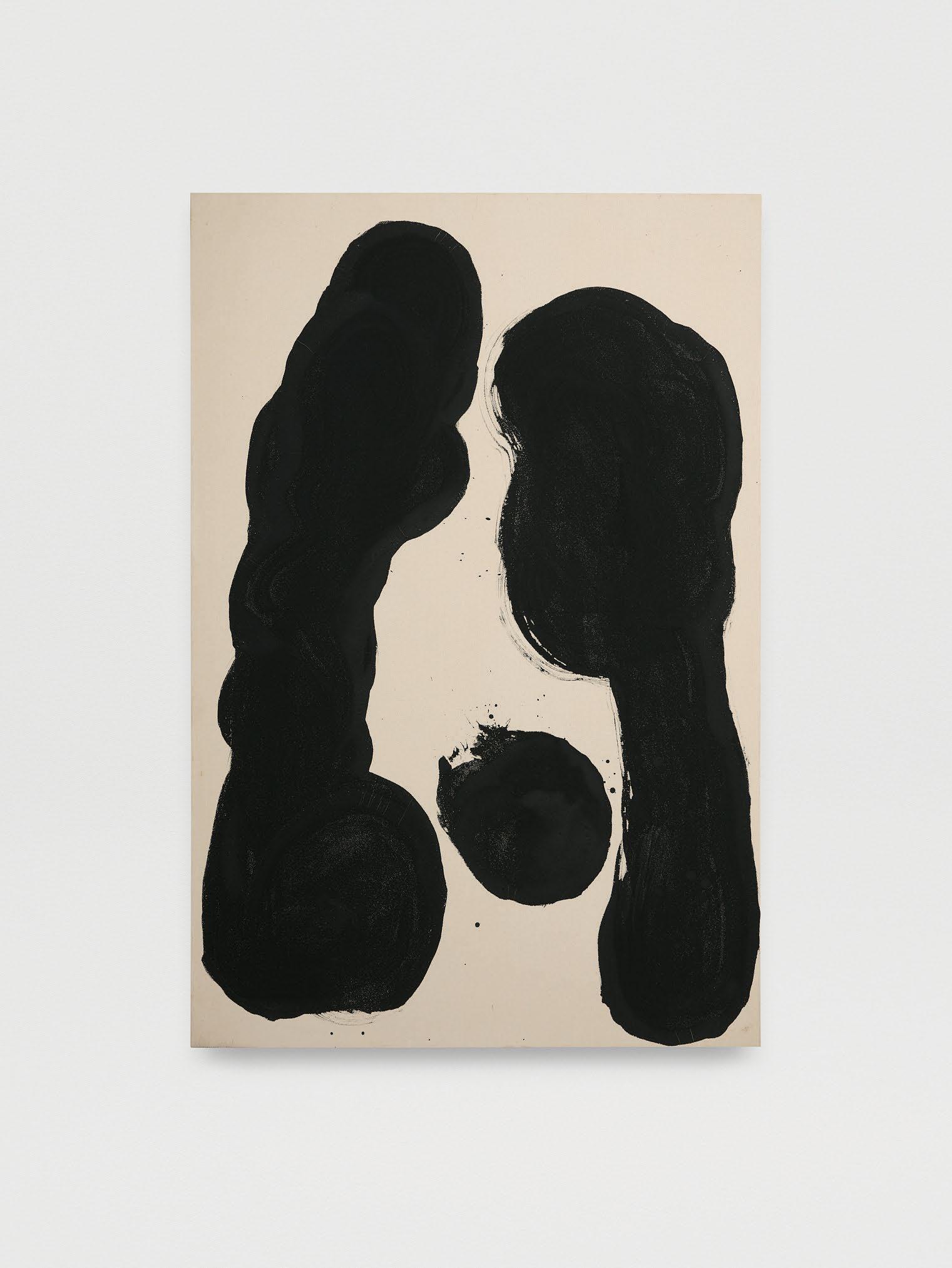

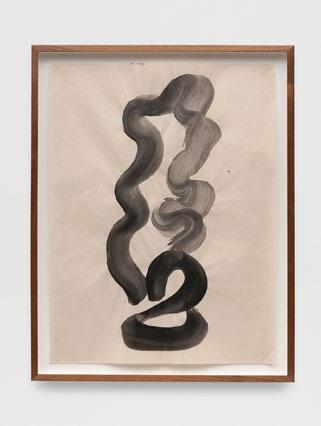

Daichiro Shinjo’s large-scale work Ma is composed of artist-made Sumi ink on hemp canvas. Opposite: A woodfired variegated stoneware vase from Jonathan Cross.

Salt-fired clay platters and geologically inspired sculptures sit alongside organic forms rendered in soot-and-deer-hide ink on handmade paper. Blurring the lines between utility and antiquity, this exhibition of ceramics and calligraphy — two artistic practices with a lineage of 14,000 years — appears less as human invention than as artifacts conjured by Mother Nature herself. In reality, the work is a collaboration between two

artists, separated by an ocean but united in sensibility, who have converged on the Blunk Space, the serene Northern California venue that has served as their muse.

Point Reyes Station, a quiet town just south of Tomales Bay, is an unlikely setting for an international dialogue of such proportions. Yet Blunk Space is more than a gallery: It was founded to preserve the legacy of J.B. Blunk, the mid-century sculptor known for his naturalistic forms, and now serves as an incubator for contemporary artists working in sympathetic traditions. “Each of their works are really gestural and physical, and I wanted to bring those two things together,” says Mariah Nielson, Blunk’s daughter and the show’s curator. In pairing Jonathan Cross, a sculptor in Wonder Valley, with Daichiro Shinjo, a shodō (Japanese calligraphy) master from Okinawa, Nielson positions their connection as a bridge to her father’s enduring influence.

For Cross, 44 — whose practice involves digging his own clay, carving, hacking, glazing, and firing in a kiln he made himself — the invitation to immerse himself in the artist’s world was transformational. “I got to go up earlier this year [in preparation for the exhibition] and just spend some time in the environment — in his house and the studio — and then I tried to

The work is a collaboration between two artists separated by an ocean but united in sensibility.

connect with his work physically through local materials and, conceptually, through some of the ceramics he did.”

While Blunk’s ceramic output focused on tangible items like plates, cups, and vases — three objects that resonate with Cross’s own craft — his broader oeuvre inspired Cross.

“His other sculptural practice included furniture, so I began making furniture in an effort to expand my use of materials and diversify in a similar way.” The result was a series of monolithic-looking side tables and stools. Some of the smaller works in the show, however, have an even more significant tie to Blunk. “I

asked Jonathan if he could dig clay from the same places that my father did,” Nielson says. The result of the endeavor includes a series of incense burners, some plates, and a planter that incorporated what Cross refers to as “clay adjacent” material dug up from Blunk’s old stomping grounds.

“The physical and improvisational expression inherent in calligraphy is said to have influenced American Abstract Expressionist artists,” says Daichiro, 32, who was an artist-in-residence at Blunk Space when he first met Cross in February. “We had conversations and he showed me some small works. When I returned to Japan, he [shared] photos of works planned for the exhibition, and I felt my character work — characterized by organic curves — resonated beautifully with Jonathan’s sharp and commanding sculptures.”

With its origins dating to the sixth century and ancient China, shodō has evolved into a distinctive art form that integrates poetry and emotion with aesthetic beauty. “First, I sketch the Chinese characters or words that will become the motif for my calligraphy,” Daichiro says, along with a surprising admission: “The time to write one piece is, at most, about three seconds — no matter how large, it’s completed within 10 minutes.” As it turns out, the most time-consuming aspects of a finished product are formulating the idea and making the Sumi ink used to paint his final vision on washi paper or hemp canvas. “It’s made using soot and glue [from cow and deer hide], and I do it in the traditional way in my studio kitchen,” he says. Although artists can save time buying ink, Daichiro considers that practice too mainstream: “Works written in Sumi ink I make myself from raw materials become more powerful and original.”

Blunk would applaud that sentiment of raw materiality and physical connection to one’s work. “It was incredibly moving to watch Daichiro paint the largest piece in the show outside of my father’s studio,” Nielson says. “It had been raining the day before, so the ground was quite wet, and all that moisture from the grass and stones embedded itself into the canvas. And then he was on top of the canvas with this very heavy brush loaded with the ink he’d made — it was very powerful, much like Jonathan’s physical gestural approach to his own work.”

It’s a parallel the artists see and wholeheartedly embrace. “Even though Shinjo’s work is less rigid, he’s painting forms on paper that are bold in their silhouette and structure,” Cross says. “And there’s a connection to my more rigid work in that his surfaces can be rough when you see them in person, and there’s a strength to the forms, themselves, that really link us.”

In a rather profound way, the show itself is a full-circle moment for Nielson. “Clay was the first material my father learned to work with,” she says. “Paint was the second — he started painting when he lived in Japan while apprenticing with two master potters. And all of the works in the show tie directly back to the time Jonathan and Daichiro spent here, which is nice. I really appreciate how immersive the environment became for them.” X

Clockwise from top right: Materials and forms from the respective artists; Daichiro Shinjo and Jonathan Cross at Blunk Space, where the pair immersed themselves in the environment to develop works for the exhibition; Cross dug up “clay adjacent” materials from around J.B. Blunk’s home and studio for several works in the show; an untitled free-form work from Shinjo composed of Sumi ink on washi paper.

As Season 2 of Netflix’s smash hit rom-com Nobody Wants This lands, Adam Brody reflects on the power of humor and hope after losing his home in the Palisades fire

Opposite: CANALI coat, $4,095, and pants, $750. BRUNELLO CUCINELLI shirt, $400. STUART WEITZMAN shoes, $825. VAN CLEEF & ARPELS watch, $37,101. CARTIER rings, $2,680 each. LE SPECS sunglasses, $95.

Words by ROBERT HASKELL

Photography by JACK WATERLOT

Styling by ILARIA URBINATI

In the middle of the first season of Nobody Wants This, Noah Roklov, the dishy rabbinext-door played by Adam Brody, explains to his almostgirlfriend Joanne (portrayed by Kristen Bell) why candles are lit on Shabbat. According to one interpretation of this tradition, he tells her, the candles represent the two temples that were destroyed in ancient Jerusalem. “We light them,” he says, “to remind us that buildings can crumble, but that doesn’t matter. What matters is gathering with people we care about. So Shabbat can happen anywhere.”

“Kind of like a pop-up,” Joanne replies.

In retrospect, this moment in the Netflix romantic comedy — one of many that underscore the culture chasm the couple must bridge to get to their happy ending — feels achingly prescient. When Adam Brody; his wife, the actor Leighton Meester; and their two children lost their home in the Palisades Fire, a sense of community provided an almost instant silver lining.

“It was a lot of things all at once and a lot of things that bubbled up after,” Brody says of the fire. “You realize that because the

» Nothing feels better than evoking laughter. I think that’s something we all need more of. «

ADAM BRODY

whole town burned, so many connections were severed. Infinite connections. We’re all these people scattered to the wind. And yet — it sounds perverse, and it sounds privileged — like COVID, there are parts of this time in my life that I’ll be nostalgic for. Our family has never been closer. I think about our sweet neighbor who knocked on my door to let us know there was fire. I think about the security guard at my daughter’s school: We’re evacuating, and it’s really bearing down on everyone, there are helicopters dropping water right over us, it’s turning into bedlam, and here is this security guard shepherding all these kids to their parents in the midst of the chaos. The school did not survive, but that connection with people in your tender moment, I’ll never forget it. When you’re raw, it feels so good.”

We’re having a late breakfast at Cora’s Coffee Shoppe on Ocean Avenue in Santa Monica. Brody’s surfboard is in the car. Promotion of the second season of Nobody Wants This is in full swing, but he’s not filming anything else at the moment, so there’s enough time to head to his favorite break in Malibu. Brody, 45, has been surfing since his childhood in San Diego, although

the fate of his favorite pastime seemed in doubt for much of the last year.

“For a while it was such an open question: What does L.A. mean to us now? Can we picture ourselves here?” he says. “But then things started coming back to life. We started coming back to life. The fact that I’m surfing Malibu again — after thinking this is so devastated and so toxic, and that part of my life is gone — it makes me feel, more than anything, hopeful,” he says, sipping his grapefruit juice.

There is little doubt that Nobody Wants This came at a moment when audiences needed the serotonergic spritz of a rom-com, faced as they were with a dystopian television and film landscape that has made little space recently for a once-cherished genre. Erin Foster’s show focuses on the love story of a basketballplaying, pot-smoking rabbi and an agnostic shiksa who recounts her sexual peccadilloes on a podcast. It’s about people from different traditions and the absurd and poignant ways in which they and their hilarious families navigate those differences. The show’s second season premieres next month.

“This is a beloved genre that hasn’t taken all that many swings as of late,” Brody

Left: LOUIS VUITTON shirt, $930, vest, $1,800, blazer, $3,250, tie, $240, and jeans, $1,820. BRUNO MAGLI shoes, $350. HARRY WINSTON watch, $62,400. Right: SAINT LAURENT BY ANTHONY VACCARELLO shirt, $1,090, pants, $1,600, coat, $14,200, tie, $300, belt, $600, and shoes, $1,300. IWC watch, $41,500. Opposite: ISABEL MARANT cardigan, $1,050, and pants, $495. BRUNELLO CUCINELLI shirt, $400. OMEGA watch, $47,200. CARTIER necklace, $5,350. Vintage belt, $150.

» The fact that I’m surfing Malibu after thinking this is so devastated makes me feel hopeful . «

ADAM BRODY

ETRO sweater, $1,990. DOLCE & GABBANA pants, $1,645, and shoes, $995. VAN CLEEF & ARPELS watch, $37,101. Opposite: HERMÈS coat, $6,050, cardigan, $1,475, and turtleneck, $1,275.

says. “And this one clearly works as a funny romantic show with a central love story that you care about. More than anything, I think that’s it. The religious angle of it is, on one hand, a nice stand-in for any difference in a relationship, any obstacle. And at the same time, whatever the state of the world, it also shows that there’s a real love out there for Jewish culture. It’s a culture cherished by not just Jews. But it’s a romantic comedy first and foremost.”

For Brody, acting was “a shot in the dark.” He had never even been in a play growing up. But at age 19, without any clear academic or professional direction, he decided to move to Los Angeles on a whim and with the tepid blessing of his parents. He worked at a couple of clothing stores on the Promenade in Santa Monica and parked cars at the Beverly Hills Hotel. He remembers those early days as lonely and anxious, but he was one of the lucky ones: After about a year, he was able to support himself as an actor. Then, at age 23, he landed a breakout role as Seth Cohen on The O.C. The soapy teen drama was a smash, and Brody became the definitive hot nerd as well as television’s most famous half-Jewish kid, introducing American audiences to the hybrid holiday of Chrismukkah. It ran for only four seasons, but The O.C. has found a new audience in Gen Z, which Brody attributes to a broader nostalgia for the aughts.

“It’s the last of the pre-cellphone eras. It was a more innocent time, war on terror and all,” he says. “Even though 9/11 took away our innocence, I still think the current generation has faced so much more of a loss of innocence

» The whole town burned. But, like COVID, there are parts of this time I’ll be nostalgic for. Our family has never been closer. «

ADAM BRODY

and probably feels so much more threatened. I know I do. I’m not going to list all the horrors, but there’s just so much coming at us: fires and floods, geopolitical intensity, authoritarianism/ fascism, technology, AI, social media. And by the way, I think Nobody Wants This offers something similar to The O.C. It isn’t about the threat of AI. It’s about people falling in love and navigating very relatable but ultimately surmountable problems. We want them to have a happy ending, and I think they will. That’s what the show is designed to do, and that’s what the show’s in service of.”

That Brody now regularly sees his character described as a “hot rabbi” provides an amusing redux 20 years after Seth Cohen, all the more so because Judaism played such a small part in his own upbringing. “Even though I was bar mitzvah-ed, I barely knew what Shabbat was myself,” he says. “True story. I didn’t really grow up around other Jewish people. My idols were all surfers, and before that your typical Michael Jordan, Hulk Hogan kind of thing. It wasn’t until much later that I was like — oh, Lou Reed. Philip Roth. When I was cast in Nobody Wants This, initially I thought, Noah’s very religious, and I don’t identify with that. And then very quickly I thought, That’s what makes this a great part for me. That’s what gives me something to do. I still feel that way. Actually, the sermons are some of the stuff I enjoy most. They allow me to try to inhabit someone with a very different language and worldview.”

Although he spends some of his free time developing scripts with friends or noodling on drums and guitar, he has his

hands full with a 10-year-old daughter and a 5-year-old son. Brody loves to take his kids to the Santa Monica Pier after school and hit the roller coaster and the arcade. On weekends, the family may take the bike path from Will Rogers Beach all the way to Hermosa. Santa Monica remains a focal point: He and Meester recently made a date night out of Nashville at the Aero Theater, and the whole family joined a rally against immigration raids in Palisades Park.

Brody is a die-hard West Sider, even if he has some regret about never having had an Eagle Rock moment in his 20s. The ocean beckons too powerfully. “You’re in this dense metropolis, and then suddenly it breaks off into this infinite wilderness,” he says. “That dichotomy I’ve always loved so much. There’s a beautiful, desolate side to the sea that I’ve always found very calming on a foggy morning. People complain about the marine layer. I think that’s insane. It’s sunny 300 days of the year here. You don’t want 65 days of a nice, cool fog?”

There are certainly worse fates than being Hollywood’s most heart-throbbing reader of the Torah. But a track record that includes the cult horror flick Jennifer’s Body and the TV crime drama StartUp suggests Brody is not keen to be typecast. He is always on the lookout for sharp, interesting stories with a point of view and a personality, in any genre.

“At the same time, nothing feels better to me than the pleasure of evoking laughter,” he says. “Right now I think that’s something we all need more of.” •

Grooming by KIM VERBECK at The Wall Group.

TODD SNYDER shirt, $218, sweater vest, $348, tie, $148, pants, price upon request. IWC watch, $41,500. DAVID YURMAN bracelet, $4,800. Opposite: PRADA top, $1,490, robe, $3,700, boots, $2,350, and pants, price upon request. CARTIER watch, $13,500.

Fifty years after Spielberg’s Jaws, California’s apex predators are misunderstood and under threat. It’s time for a rebrand, say the experts (and the king of Hollywood himself)

Words by DEGEN PENER

Ithought my career was virtually over halfway through production on Jaws,” recalls Steven Spielberg at Los Angeles’ Academy Museum of Motion Pictures at the official preview of the new show Jaws: The Exhibition, which celebrates the 50th anniversary of the film.

The movie, based on author Peter Benchley’s best-selling book, famously ran 100 days past schedule and more than three times over budget. Shooting the film was a constant challenge for both the seasick crew (“I’ve never seen so much vomit in my life,” Spielberg says) and because the mechanical shark, which had been tested only in freshwater, kept malfunctioning once it hit the ocean. “Everybody was saying, ‘You are never going to get hired again,’ ” Spielberg says.

Of course, his fears weren’t realized. Jaws, with its white-knuckled story of man against terrifying beast — aka Bruce, a 25-foot mechanical great white shark (five feet longer than the largest white shark ever recorded) — not only launched the director’s illustrious career but also ushered in the phenomenon of the summer blockbuster. “The film certainly cost me a pound of flesh but gave me a ton of career,” Spielberg says. “Fortune smiled on us.”

The fun-filled, interactive exhibit, which runs through July 26, 2026, includes the Oscars won by composer John Williams and editor Verna Fields for their work on the movie; costumes and props; behind-the-scenes photos; and even a small keyboard on which you can play the film’s iconic “ba-dum, ba-dum” musical motif. As visitors leave the exhibit, they encounter the only surviving fullscale model of Bruce the shark. Hanging in midair, the monstrous piece of memorabilia is part of the Academy Museum’s permanent collection.

Yet beneath the nostalgia, the legacy of Jaws remains complicated. Jaws: The Exhibition only

A shark swims off the Pacific Coast of California.

briefly addresses what’s become known as the “Jaws effect.” Although earlier books and newspaper stories had hyped shark attacks, conservationists and scientists have blamed Jaws for unleashing a cascade of negative effects on the animals. It all goes down to the film’s depiction of great whites as bloodthirsty animals intent on hunting down and eating humans. Marketing materials for the film at the time called sharks “maneaters” and warned that “if you swim in the ocean … the shark is an ancient, wide-ranging and ever-present threat.”

Thanks to Spielberg’s genius directing, Jaws succeeded far too well at intensifying public fear of sharks. In subsequent years, there was a rise in shark-fishing tournaments across the U.S. (One section of the exhibit acknowledges that “in the immediate aftermath of Jaws, recreational shark fishing increased.”) Advocates also believe that the film helped legitimize the indiscriminate killing of the animals, and it made it hard for conservationists to drum up public support for shark protections.

The 1970s marked the beginning of significant declines in populations of sharks around the world, and today an estimated 100 million sharks are killed annually. Many species’ populations are imperiled because they are caught as by-catch in fishing nets, whereas others are harvested as low-cost protein or to make shark fin soup (a delicacy, even believed to be an aphrodisiac in certain cultures) and cosmetics (the ingredient squalane is made from the animals’ fatty liver oil). And if it seems like a stretch to ascribe so much power to a movie, don’t you know someone who’s afraid to go into the water because of Jaws?

“I think that the fear of sharks allows people to just excuse the killing,” says director Eli Roth, whose 2021 documentary Fin investigated the trade in shark fins. (Since the debut of Jaws in 1975, an estimated 200 more films have been released that cast sharks as threats, including the critically acclaimed Open Water (2003) and the unfathomable Sharknado (2013).)

But, adds Roth, “it’s not that all of a

But the impact of Jaws wasn’t wholly deleterious. “The film also created awareness of sharks. It also created interest,” says the Academy Museum’s Jenny He, the curator of Jaws: The Exhibition. “People not only wanted to be filmmakers because of Jaws, but they also wanted to be ocean scientists.”

Fifty years later, California may have entered its post-Jaws era, thanks to several factors. In 1994, voters passed a law that banned gill net fishing (which uses vertical walls of netting) within three miles off the Pacific coast. The nets notoriously trap nearly everything that

»I thought my career was virtually over halfway through production on Jaws. «

STEVEN SPIELBERG

sudden people started killing sharks because of Jaws. They started killing sharks because of greed. What really damaged them was when people realized how much money they could make off of them. We’re killing all of them at an unsustainable rate, and it’s going to have irreversible consequences.”

Spielberg himself has said (in a 2021 interview) that he’s sorry for the Jaws effect: “I truly, and to this day, regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film. I really truly regret that.”

ban. In 2011, California also became one of the first states to outlaw the trade of shark fins — 11 years before the U.S. passed a full national ban. In California waters, “there are definitely more sharks than people think,” says Lowe. In

species. As predators, they keep the ocean healthy and maintain a healthy food web,” says Geoff Shester, a senior scientist and the California campaign director for conservation group Oceana, which has helped pass shark fin

Clockwise from bottom left: Steven Spielberg, seen kneeling with camera, was 27 when he completed filming on Jaws ; a production clapperboard from the set of the film; a Pacific Coast shark among a school of fish; an installation view of Jaws: The Exhibition at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures.

lower than being struck by lightning. Over a 75-year period, from 1950 to 2025, the California Department of Fish & Wildlife has documented 225 shark incidents. Of those, 116 caused injury (including loss of limbs) and 16 were fatal — about one death every 4.6 years. By contrast, more than 4,000 people are killed every year in car accidents in California. And many more people are killed by jellyfish every year globally (40 to 100). But when was the last time you saw a Hollywood movie about a killer jellyfish?

When white sharks (the most abundant apex predator in California’s waters) do bite humans, it’s thought to be “a case of mistaken identity,” says Shester. “There’s never been any

documented case where a shark actually eats the flesh of a person.” More mature white sharks are generally searching for seals, which they like for the high fat content of their blubber. Humans, by contrast, aren’t fatty enough. “Sharks basically taste you and they are like, Ew, I’m spitting this thing out,” says Shester. Adds Roth, “We’re not on their menu.”

Most white sharks — which are known for their white undersides and serrated rows of teeth — that are found off the coast of California are juveniles, around five to nine feet in length, feeding mainly on fish. Remarkably, recent drone footage shows that juvenile white sharks are more present than many people realize. And the vast majority of the time they don’t interact with humans in the water.

“Chances are if you’ve been out there swimming or surfing off of Southern California — or Northern California, for that matter — you’ve been feet away from a white shark that has swam right by you completely peacefully, not minding you, not interested in you,” Shester says.

» Sharks are some of the ocean’s most ecologically important species . «

GEOFF SHESTER

patrols akin to a South African safety group called Shark Spotters. “They have shark spotters and they’ll sit and if they see a shark coming they blow the whistle and everyone gets out of the water until the shark passes and then they go back in and that’s it,” says Roth. “It used to be they’d go out for an hour, and now it’s like five minutes and you’re back in.”

The new Netflix documentary The Shark Whisperer is another sign of the evolution of attitudes toward sharks. In remarkable footage, the film follows Oahu-based shark advocate Ocean Ramsey as she free dives with sharks, including white sharks. While she cautions that most people shouldn’t try to do what she does, Ramsey has said that it’s her mission in life to “dispel this sort of Jaws fictitious portrayal of [sharks].”

This remains the case even given the fact that more people are in the ocean than ever before — an estimated 150 million beach visits happen every year in California, up from around 129 million in the early 2000s.

Shark bites though aren’t rising in proportion to more people being in the water. In fact, “there are these tantalizing bits of data that may actually indicate that shark bites will go down in the future, despite the fact that there’s more sharks and more people,” Lowe says. The theory is that if more sharks are exposed to humans from infancy onward, they will “learn to identify us and realize we’re not food and we’re not a threat,” he explains.

Even so, to mitigate risks, Roth advocates that California beach communities set up

But de-horrifying sharks can only do so much to help them, argues Stefanie Brendl, the founder of the L.A.-based conservation organization Shark Allies (which is currently lobbying the EU to pass its own ban on selling shark fins). “You know, we have greatly improved the perception of sharks through advocacy all over the world, but that has not reduced the commercial fishing of sharks. So whether you like sharks is irrelevant,” she says. What matters is more action on their behalf. Advocates for sharks say that consumers can take actions to help like choosing seafood that’s caught sustainably and picking self-care products that are made with vegan squalene instead of from shark liver oil. And California’s government could continue to be a leader. Currently, there’s a bill in the state’s legislature that would further limit gill nets in coastal waters. And California could follow Hawaii’s lead in outlawing the killing of any sharks in its waters, which went into effect in 2022.

But, adds Lowe, “Look how far we’ve come in 50 years. I always joke that if you tried to remake Jaws today, it wouldn’t have the same effect because I think people know so much more about white sharks now.” Case in point: This past summer on July 31, a roughly 15-foot great white shark made headlines across the world. Caught on video by Carlos Gauna (a drone photographer who runs a popular YouTube channel called The Malibu Artist), the shark didn’t bite anyone. Beaches weren’t closed. Tourism didn’t immediately plummet. The summer routines of L.A. hummed blissfully along. •

Spielberg at the Academy Museum with Bruce, the shark model from Jaws

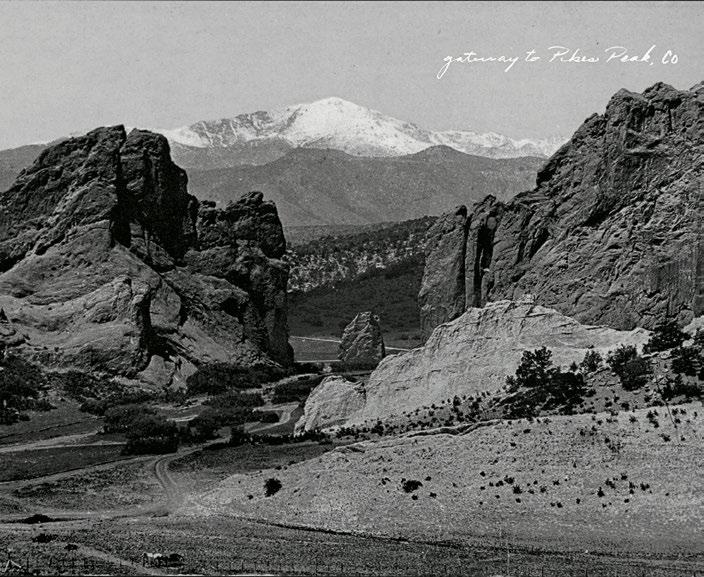

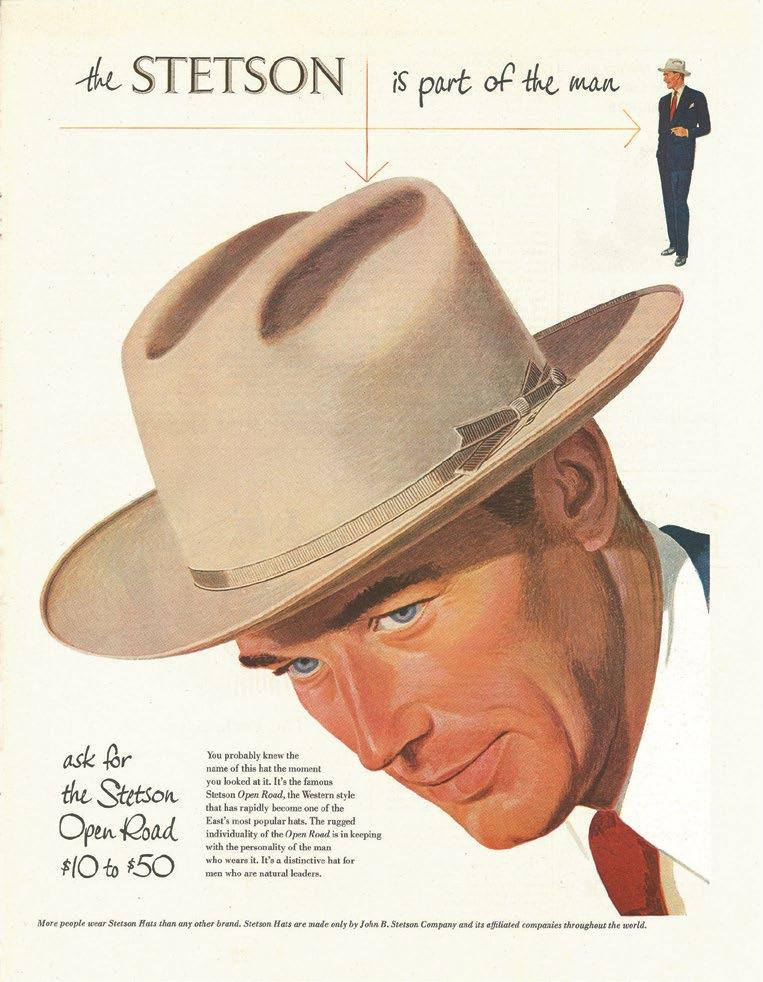

How eight ounces of pelt and 80 skilled hands create the perfect cowboy hat for one aficionado of high-end Americana

Words by JAY FIELDEN

In the 1970s, when I was a kid growing up in San Antonio, we visited family on holidays who lived in far corners of the state. These were places still attached in rhythm and style to a time gone by — no grown man set foot outdoors without a western hat. The old-timers, the ones who’d made it in the oil, ranching, or other related business, mostly wore what was considered the “gentleman’s cowboy hat”: a Stetson Open Road. Or if they enjoyed dressing up when they weren’t in field clothes and embraced the flair of western wear — whipcord suits with yoked seams on the shoulders and darts shaped like arrowheads — they likely chose a silverbelly Range, with its narrow brim kicked up on the sides to form a pleasing little swoop cantilevered just over the brow. This was my grandad’s hat of choice, which, in old-Hollywood western style, he cocked to one side.

As I got older, I inherited a few family Stetsons. Some fit, some didn’t, but I kept them as signifiers of my past; they reminded me of the place and people I came from. When I began my career as a magazine

editor and writer in New York, my grandad’s hat moved with me. Eventually, as the editor of several fashion and style publications, I got the opportunity to see and understand what true handmade luxury looks like up close. I traveled to the Veneto, a cradle of leather craft, to witness the creation of a bench made pair of brogues. I visited the ateliers of the world’s great bespoke tailors, from Savile Row to Naples. And I learned what a “MOF” is — the acronym (Meilleur Ouvrier de France) used to refer to the country’s topmost master craftsmen — and had seen them at work in couture houses. I somehow knew all this, and yet, until a recent visit to Stetson’s hat-making headquarters in Texas, had no idea that its extraordinarily painstaking process and meticulous standards of quality represent a true American equivalent.

In case you haven’t noticed, cowboy hats are in the midst of a comeback, thanks to western hats being embraced as symbols of style across the pop-cultural spectrum, from big luxury fashion labels and major music icons to juggernaut TV shows. These days, as a result, Stetson not only makes three times more cowboy hats than it does any other style, its hat-making operation, which remains largely the same as it was more than a century ago, finds itself in a happy predicament. Like a small handful of top Swiss watchmakers or a certain maison of luxury French leathergoods, Stetson these days can barely keep up with demand. As with other artisanal enterprises that make exceptional things using traditional methods, Stetson’s output is a painstaking operation that hangs in the balance of three fluctuating ingredients: the finite availability of premium felting material; the limited number of highly trained human hands; and the mechanical dependability of a last-of-its-kind fleet of rare machines,

some of which date back to 1892. At full hum, when everything’s moving in a synchronized flow, it takes about four weeks to transform an eight-ounce blob of down — mostly rabbit with varying amounts of beaver mixed in — into a Stetson. The former comes from Eastern Europe, where rabbit is often on the menu, and fur production is a by-product of the farming process. Beaver, however, must be trapped in the Canadian wild. Its fur, which is more water repellent, is less plentiful and more desirable. The more Xs a Stetson has — the range goes from six to a thousand X — the more beaver it contains, and the more $s it costs.

I say blob, but this was a blob unlike any I’d seen; it was fluffy and white and reminded me of a large, freshly whipped cloud of cotton candy. I was standing at the far end of a long, low-slung building in Longview, a town of some eighty thousand people in East Texas. The place had what you might call old-factory charm, including a hundred-yard wall of steel windows, industrial fans encrusted with ancient lint, and a giant retro sign — “Good Hats Make Steady Jobs” — that might have been hung when LBJ, an Open Road enthusiast, was president. Hat-business people call a place like this the “Back Shop.”

A dense, wild animal odor hung in the air, and wisps floated about the space like indoor snow, as fur from 250-pound bales was being blown through two very long shafts — antique cotton gins retrofitted with comb rollers. By this process, the hair is separated from the down, and it is down — when exposed to heat, moisture, and pressure — that miraculously forms into felt (as the Mongols, those twelfth-century cowboys of the Steppe, found out when the fur pelts they wrapped their feet with transformed through use into a material that was both insulating and waterproof).

it becomes about a quarter of its original size. Then it gets dyed in large stainless steel vats (Stetson’s colorways are proprietary and mixed by hand in Longview) and lightly shellacked, which fortifies the felt to hold its future shape. That process begins with the “tipper,” who, now that the shrinking process has made the felt thick and dense, carefully applies the power of his shaping machine, which pushes and pulls the hat down over a molded block as he slowly works to define the crown.

Almost a thousand years later, Stetson’s process of making felt is a science that blends man and machine. But it still takes a lot of time for the trained hands of around eighty people divided among eight distinct and detailed jobs to turn that blob of down into an unshapen, floppy thing called a “hat body,” which is as much an approximation of a hat as a bolt of wool flannel is to a suit. One strangely looks like a Gemini space capsule, and the man or woman who operates what’s called The Former must, not unlike an astronaut, become one with the quirks of his machine. Those eight ounces of down are vacuum-sucked onto a large metal cone that you can see spinning through a port window of the Former’s closed hatch door. The cone, now flocked with down, is next handwrapped with a wet burlap blanket, sheathed with a second cone, and submerged in a nearby tub of water that’s been heated to 160 degrees. This step forces hot water through the mat of hair fibers, which, individually, look like barbed rose stems under a microscope, condensing and shaping them into what’s called a “boat sail” — a triangular cap whose name captures its exaggerated scale. At this point, it’s about eight times the size of the cowboy hat it will eventually become.

From there, each boat sail is cycled through a series of some seven different operations that pair specialized human expertise with specialized antique machinery prone to crap out. (The Back Shop maintains three machine shops on-site.) Station by station, the cap gets rolled under pressure, wrapped and rolled again, soaked, and squeezed until

The next and final step is “wet-blocking,” which also requires great touch and experience, knowing how to mold and stretch the felt without tearing it to shreds. A wet-blocking machine is a little like a giant waffle iron, except the hot ingredient is water. There are three of these machines, and they’re all ancient and finicky, requiring a new recruit anywhere from four to six months of training to become proficient. They also break down a lot. As a result the company recently commissioned a tool builder in Missouri to create a new one, based on the physical size and movements of an employee who has worked here for fifty-one years.

Instead of Model-T technology, the new Blocker is pneumatic and has a computerized brain. That doesn’t mean it operates itself. Among other things, not only does the hat have to be placed just so in order for a series of little finger-like clamps to hold onto the brim as a hot mold stamps down to further form the crown and “break” the brim, but a wet blocker has to know when the felt is the perfect stage of al dente so it’s neither too early nor too late to manipulate its shape.

After that, all that’s left is for the hats to dry before they get shipped a 120 miles west to Stetson’s “Front Shop,” which is located in Garland, a suburb of the Dallas metroplex.

The setup here is even bigger — there’s a separate factory building dedicated to making only straw hats, which amounts to about a third of Stetson’s overall production. Shafts of steam exhale toward the corrugated

ceiling, and there’s a constant rat-tat-tat from a troika of irreplaceable Singer 103 sewing machines that were designed for one of the most challenging tasks in the whole factory — backstitching a hatband made of leather to the inner rim of the crown. “Dozens” — wood trolleys carrying hats in job orders of twelve — are everywhere, as they make some thirty different stops on the way to becoming a finished hat. (Stetson makes about 250 dozen per day.) A taste of these stops includes: two sessions of dry blocking; more shellacking; “pouncing” (a multistep process by which the felt is conditioned with fine oil and then sanded to achieve different textures); brim cutting; brim beveling; trimming (an eight-station process involving the creation of a Stetson’s interior features, from “swirling” the satin lining to sewing in the bow at the back); and two different points of inspection overseen by two of Stetson’s most veteran employees, who look for “dags,” color imperfections, “shoves,” anything that’s off. A hat that doesn’t make it past them is called a “knockdown.” About a hundred per day don’t meet the bar.

As anyone who owns a Stetson knows, there are many styles to consider, from the fedora-like Stratoliner and “crushable” outdoor numbers to the iconic, western-style Boss of the Plains. Part of figuring out which one’s right for you is learning a little about what the different creases and brim shapes mean. In the old days, they often signified a wearer’s profession — cowpunch, bronc rider, barrel racer, outlaw, or horse breaker, as Cormac McCarthy describes the hero of All the Pretty Horses, whose hat is mentioned repeatedly though never described. Stetson has some fifty-four different crown-style molds, and as many brim flange-molds as there are degrees to a parabola.

I, myself, prefer an Open Road, and have always owned one even when I was trying to convince people in New York that I didn’t have a Texas accent. At the factory, I felt I should try something new, so I plucked out a snuff-brown El Patron, a high-crown cowboy hat that strikes a note of self-possessed boldness. I wanted it to have a Cattleman crease with sides that curve sharply upward, like James Dean’s in Giant

The factory manager and I walked over to the crown press. He put a crown mold in a small metal hole and placed the crown of the hat into it upside down. Then a hydraulic press descended, inflating a balloon to 100 psi where your head goes. After sixty seconds, out came the hat, its iconic crease

In case you haven’t noticed, cowboy hats are in the midst of a comeback, thanks to western hats being embraced as symbols of style across the pop-culture spectrum.

beautifully minted. “Cattleman all day long,” he said, as we walked to a double-row of Flange Brim machines. The hat was again dropped in a hole and placed on a flange that looked like an upside down taco. A top mold squeezed the felt brim between the two pieces of metal, which had been steamheated to 260 degrees.

He gingerly plucked the hat onto a second flange and lay several small sandbags on its brim so it would hold its shape as it cooled. After that, I put my hat on, so he could eyeball it for any imperfections. “Yes, sir,” he said, meaning, it had met the Stetson standard.

Only one thing left. A customary part of inspecting a hat is, as they say, “popping it.” You do this by gently pinching the front of the crown to test the resistance of the felt. Some people like a stiff hat that’s hard to pinch; others like one that’s softer and as a result makes a little pop as it reassumes its former shape.

“The sound is that immediate gratification,” my guide had told me back in Longview. “But the feel is what’s important.” I gave my El Patron a pop, which sounds more like a thwip. The sound was pleasing, indeed. But what he said was true: What makes a Stetson a Stetson is its feel, which is that of sculpted cashmere, and is something that’s easy to like. I have come to think this is one of the chief reasons I myself now rarely set foot outdoors without one on my head. Excerpted from Stetson: American Icon (Rizzoli, $100). •

Clockwise from opposite top left: The hat body in the forming chamber, the first step in the bodymaking process — the fur is dispensed on the cone to start the initial body; beveling the edge of a hat to give it a neater look; a worker pressing the crown; pouncers in the finishing department at the John B. Stetson Co. factory in Philadelphia in 1925; Open Road advertisement, circa 1951; Pikes Peak, the highest summit on the Front Range of the Southern Rocky Mountains, through the Gateway of the Garden of the Gods, circa 1895; developed in partnership with Bruno Mars and his fashion label, Ricky Regal, the Regal 6X was available in three colors, Black, Chocolate, and Silverbelly, and arrived in a custom cobranded box.

Joelle Kutner and Jesse Rudolph, the longtime friends and founders of interior design and development studio Ome Dezin, are describing what they look for in a house. More specifically, what state of disrepair a property needs to be in for them to get excited. “Sometimes when we see houses and they’re not in a true need of repair, so it doesn’t feel like they deserve it,” says Rudolph, glancing at Kutner, who nods in agreement. “We’re looking to really transform something.”

But the Los Angeles–based duo’s latest renovation of architectural significance, a 2,920-squarefoot 1960s residence nestled in the hills of Laurel Canyon, was more than they bargained for. “This was a house where there were more and more issues. Everything had to be replaced. The only things we kept were three large fixed windows,” Rudolph says.

Luckily for the pair, whose recent work of note includes an A. Quincy Jones home in Brentwood and a 1927 Tudor-style cottage once owned by the burlesque star Lili St. Cyr, they knew who to call: furniture and spatial designer Ben Willett — who also happens to be a good friend.

“I wasn’t too worried about what was going on inside because we were going to bring it back to its original glory,” says Willett, who has recently exhibited some of his sculptural takes on mid-century classics at the prestigious The Future Perfect gallery. “This was a holistic approach. And also a great opportunity for me to have an impact on every single space in the home instead of just plopping my pieces into one room.”

For their first project together, the three

In Laurel Canyon, a design duo call on a kindred spirit to help turn a tricky renovation into a mid-century marvel

friends had been looking for a house that would fit both their aesthetics. “Jesse and Joelle’s style is a little more European and romantic, whereas I lean more toward California,” Willett says.

They sought to honor the property’s midcentury roots by using natural materials and to improve the flow between the interior and the outdoors. Warm Douglas fir was applied across multiple custom elements, from a slatted front door to the built-in system in the primary bedroom incorporating a desk and a daybed. Black flagstone flooring runs from the entryway to the

Ome Dezin, it took some getting used to.

“It’s a fairly difficult wood to work with,” Rudolph says. “There’s a warmth to it that’s really special, but once it gets sun exposure it darkens, so we had to play around with varying temperature levels depending on the location.”

For Willett, the most challenging aspect was more personal. He and his wife, the cook and content creator Molly Baz, and their baby son lost their Altadena home in the January wildfires just as this project was drawing to a close. Many of the pieces that feature in the Laurel Canyon

» I wasn’t too worried about what was going on inside because we were going to bring it back to its original glory. «

BEN WILLETT

kitchen, dining area, and study through to a backyard of lush greenery overlooking the canyon.

“One of the allures of living in California is you get 300 days of sun, so if you use the exterior you double the square footage of your home,” says Kutner, who launched the business (pronounced “home” without the H in honor of how her French husband pronounces the word, and “dezin” like “resin, which plants produce to repair themselves”) with Rudolph in 2020.

Willett, who founded his eponymous DTLAbased furniture design studio in 2022 after 15 years working in retail and event design for brands like Nike and Uniqlo, is no stranger to Douglas fir. For

house — including an hourglass-shaped Radi Table and Chairs and glossy red Popo Chair — he had originally designed for his own home.

“Seeing the Douglas fir and my furniture pulled at my heartstrings because our home had a lot of similar elements,” says Willett, who is renting a home in Pasadena. “It’s been very, very hard. But, you know, I think things happen for a reason. We’ll find our next forever home and make it that much more beautiful.”

That Ome Dezin were willing to trust Willett to run with his ideas across the entire project was a career milestone for him — as well as a learning curve. “I come from a world where

it’s, ‘Okay, here’s your budget; it’s $2 million; here’s what we want to do.’ Whereas this was more, ‘Well, if we do this over here, then we can’t spend the money over there, and which is going to be more impactful?’ ” Willett says. “I leaned on Jesse and Joelle because I know what I think looks good and what’s important for me as a designer, but it might not always translate to a family or individual.”

Ultimately the gamble paid off. The property was purchased off-market prior to even being listed. “It taught us that even when you do something that’s a little risky, it can really pan out,” Rudolph says.

There is always a degree of risk when you go into business with your nearest and dearest, Kutner says. “You hear of people working with best friends or romantic partners and then they’re in a lawsuit together. It would be sad if that happened. But I think that Jesse and I are reasonable enough that we could probably talk our way out of any conflict.”

A complementary skills set is another reason Ome Dezin is thriving. They are currently juggling four projects, including a recently finished Mediterranean property in Outpost Estates. “It wasn’t like we set out to create a brand,” Rudolph says, marveling at how Kutner “goes into a space and emotionally feels things more than I do.” Rudolph, by comparison, is more detail-oriented, Kutner says. “He’ll get into the nitty-gritty of learning how things are made.”

“When designing, building, and renovating, it really comes down to people with different skills and know-how,” Rudolph says.

Like the Laurel Canyon house, it is a friendship built to last. •

Words

MARTHA HAYES

Warm Douglas fir is referenced throughout to honor the property’s mid-century roots. “To make it a little sleeker and sexier, we used black flagstone for the floor, which plays really nicely with the Douglas fir. It’s kind of yin and yang,” says furniture designer Ben Willett, who oversaw the creative direction of Ome Dezin’s latest restoration project. To complement Willett’s pieces, furnishings were cherry-picked from local antique store DEN and texture was added to the space by applying cc-tapis rugs to the walls as tapestry. “There’s a lot of hard edges and 90-degree angles with mid-century, so we wanted to layer in some softer materials,” Ome Dezin’s Joelle Kutner says.

by

Photography by AUSTIN LEIS and YOSHIHIRO MAKINO

CALIFORNIA CLASSIC

The airport prepares for the next 100 years

The occasionally turbulent metamorphosis of Los Angeles International Airport (better known as LAX) is more than a flight of fancy. It’s a $30 billion Capital Improvement Program that began in 2024 with the intent of elevating traveler experience and significantly boosting efficiency — particularly in advance of the 2028 Olympic Games, which will see several million passengers flying in and out of the airport during the two-week event. Originally known as Mines Field, the airfield began operation with dirt landing strips on October 1, 1928, with its first structure, Hangar No. 1 — a Spanish Colonial Revival–style building now on the National Register of Historic Places (and still in use) — finally erected the following year. As it evolved over the next three decades into a modern airport, its most recognizable structure, the otherworldly Theme Building — designed in collaboration with pioneering architect Paul Williams — opened in 1961 as California’s preeminent symbol of the Space Age. The early 1980s saw the next major round of changes in anticipation of the 1984 Summer Olympics, with the addition of two terminals, a second level for the U-shaped roadway (which delineated arrivals from departures), and a multistory parking structure at the airport’s center. And, as with most construction projects, work has continued fairly steadily since then — much to the chagrin of wing-weary globetrotters and Angelenos alike — and completion on this next major expansion is expected to wrap in 2030. Until then, we ask that you please remain seated with your seat belts fastened. X

Words by DAVID NASH

LAX FACTS

● Installed in 2000 as part of an $80 million beautification project, the 32-foot-tall LAX letters greeting passersby along Sepulveda Boulevard and indicating arrival to the airport were removed in September — but only temporarily. In order to complete the new road and landscape designs, the towering acronym will be stored and eventually relocated to integrate seamlessly into its refreshed surroundings at a date to be determined.

● As part of the modernization project, a major update to the infrastructure will see 4.4 miles of new and reconfigured automotive roadways and pedestrian bridges that will remove more than 500 vehicles from local streets at peak times. With construction beginning late this year, many of the most important portions will be finished in time for the 2028 Olympics.

● As a Tinseltown fixture, LAX has taken its star turn on the big screen in many feature films, including The Killing (1956), The Graduate (1967), Airplane! (1980), Blade Runner (1982), Speed (1994), Fight Club (1999), Catch Me If You Can (2002), Terminator Genisys (2015) and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019).

Clockwise from top left: Architect Paul Williams in 1965 in front of the Theme Building he collaborated on; the forthcoming Terminal 9, connected to the main airport by a train system, will accommodate 29 gates and have full customs and immigration capabilities; the future Automated People Mover will see an anticipated 30 million passengers per year when it opens; a rendering of the airport offers a glimpse into 2030; installed in 2000, the imposing LAX letters will be rehomed when the roadways and landscaping redesign is complete.

CALIFORNIA

STYLISH LIVING FROM CANYON TO COAST