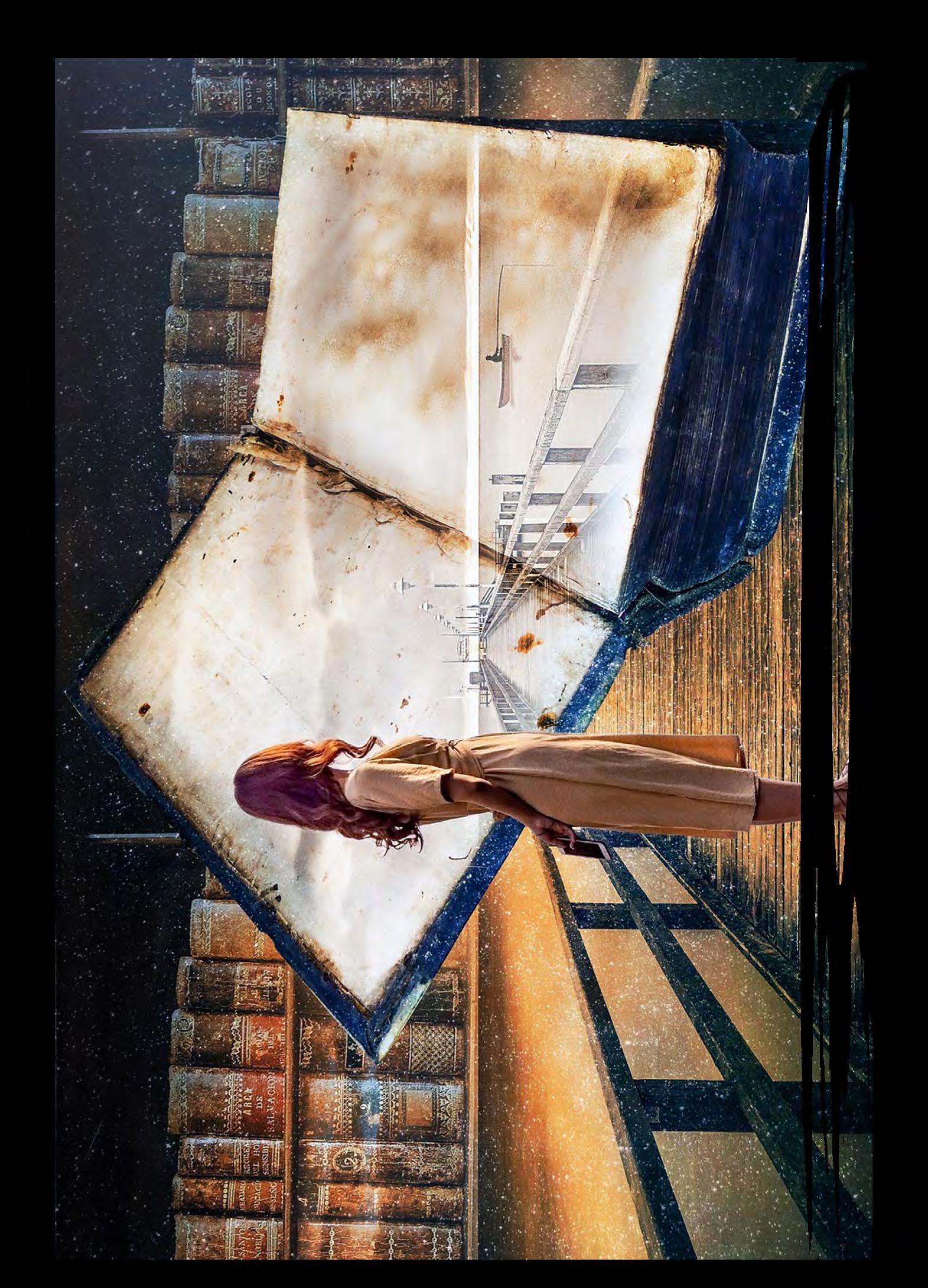

A Review of Evidence

Measuring Wellbeing. Gauging (Mental) Wellbeing Benefits of Arts & Cultural Participation: Insights & Approaches

Written by Dr Sophie Mamattah (Centre

for Culture, Sport & Events, UWS) and Tamsin Cox (DHA Communications), this review comprises part of a suite of evaluation tools and resources developed for use across the activities taking place within the framework of Future Paisley.

Future Paisley is a programme of cultural events and activity based around Paisley and Renfrewshire’s unique and internationally significant story which uses targeted investment to deliver positive change and, puts culture at the heart of Paisley and Renfrewshire’s regeneration.

ISBN: 978-1-903978-69-6

Contents 1.0 Introduction 4 PAGE 5 2.0 Methodology & Approach 2.1 How to Use this Review 8 3.0 Arts, Culture and Wellbeing – Creative Health 3.1 What is Wellbeing and How does it Fit Here? 3.2 How We Know Wellbeing through Data 13 4.0 Approaching Evaluation 4.1 Qualitative Approaches 4.2 Validated Approaches 4.3 A Closer Look at WEMWBS 5.0 Capturing the Benefits of Arts & Cultural Participation for (Mental) Wellbeing: some answers to the questions posed at the outset of this review 6.0 Bibliography 7.0 Appendix A: Evaluation Mapping 20 22 28

1.0 Introduction

This review seeks to give insight into the ways in which the efficacy of arts and cultural interventions aimed at supporting participants’ mental wellbeing can be evaluated. The value of arts and culture for health is widely acknowledged (i.e. ACE, 2018; APPG, 2017; Cayton, 2007, Clift, 2012; Fancourt & Finn, 2019; Gordon-Nesbitt, 2022). However, a closer look at the available literature shows that the breadth of the arts and health field presents challenges in terms of defining the area of interest and, evidencing the effect of any intervention that is undertaken (i.e. Oman, 2021; APPG, 2017; McElroy et al., 2021; Thomson & Chatterjee, 2015; Daykin et al. 2017a; Daykin & Joss, 2016). Arguably, this is particularly the case where projects seek to evidence intangible benefits deriving from an intervention, such as improved (mental) wellbeing. In their work contributing to the development of the evidence base for mental health, social inclusion and the arts, Secker et al. found that – rather than making use of available validated scales – many of the projects participating in the study ‘were reinventing the wheel in designing their own ways of measuring similar constructs such as enjoyment or self-esteem’ (Secker et al., 2007; also see Hacking et al., 2006). This finding underscores that, the desire to evidence outcomes can be stymied by lack of appropriate knowledge and skills (Secker et al., 2007; also see Hacking et al., 2006).

The emphasis on mental wellbeing and evaluation means that this review is focussed on a very specific corner of a broad and sometimes ill-defined area of literature. There are a couple of issues to keep in mind:

• The definition of wellbeing is mutable (i.e. Oman, 2021, APPG, 2017; Fancourt & Finn, 2019) and, with regard to mental health (rather than aspects of physical health) wellbeing may not be directly discussed. Rather the benefits of an arts/cultural project can be couched in terms such as ‘resilience,’ ‘self-esteem, ‘behaviour regulation.’

• Much of the literature included in this review has been written to report and reflect upon the process of devising and running a pilot or project and its overall impact for the target group. While evaluation is part of that process, for the most part reflection on the efficacy or appropriateness of the evaluation itself, is not the foremost focus of the discussion or, is not discussed (here, Centre for Cultural Value, (2022); Secker et al., (2007); Hacking et al., (2006); Ander et al. (2011) & Daykin et al. (2017a), White & Salamon (2010) are among the exceptions).

2.0 Methodology & Approach

This review focusses on academic and grey literature examining art, culture and wellbeing alongside issues of evaluation and measurement in the area.

Search terms ‘wellbeing AND culture,’ ‘wellbeing AND arts,’ ‘wellbeing AND arts AND culture’ and ‘wellbeing AND evaluation’ were used. The terms ‘mental health’ and ‘mental wellbeing’ were also added to these keyword combinations. Additional information regarding the projects and programmes discussed in these studies was also sought out (i.e. grey literature, community-led write ups, webpages etc.). The reference lists of the sources uncovered were also searched for any relevant information. Related web resources were also sought and scrutinised (i.e. www.creativeandcredible.co.uk).

In the following, this review seeks to establish the field of discussion; looking at the area of arts and health, establishing how wellbeing can be understood here and, specifically, how wellbeing and mental health are discussed/usefully understood. The review briefly acknowledges some of the (policy fuelled) expectations/ preferences that impinge on thinking around evaluation (see: MacLennan et al., 2021). The question of measurement/effective evaluation is then explored. Subsequently, the ways in which scholars and service providers have sought to approach the issue of data gathering for evaluation is examined. Of the validated measurement tools discussed, Warwick Edinburgh Wellbeing Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) – developed ‘on the understanding that subjective wellbeing can be used to measure a particular programme’s effectiveness’ and reasonably popular with arts and health organisations (APPG, 2017) – is looked at in more detail. Finally, the evidence discussed is summarised with reference to any insights it provides with reference to the following areas of interest:

• What measures, particularly standardised, are commonly used to gauge wellbeing in projects focussed on arts, culture and mental health?

• What are the pitfalls/ challenges or examples of great practice?

• What, if anything, can we learn about proportional/appropriate application of tools?

• What, if anything, can we learn about data collection methods- and issues –i.e. collecting data from young people?

Appendix A comprises mapping of a number of arts and cultural projects and the evaluation approaches taken within these. It shows the variety of approaches potentially available and, is intended to serve as a useful reference point for evaluation planning.

5

2.1 How to Use this Review

This review provides an overview of a complex field. It is not intended as an instruction manual, rather it sets out to give insights into a challenging subject area and, to assist the reader in thinking about how and why certain approaches have value, what challenges may be encountered when attempting to evaluate mental wellbeing and, how they might be counterbalanced.

A wide range of pre-existing (validated) resources are available, many of these have been signposted throughout this document alongside a variety of freely available resource banks (i.e. The What Works Centre for Wellbeing’s Measures Bank: https://measure.whatworkswellbeing.org/measures-bank/). This review aims to help those planning projects and programmes to think through the issues surrounding evaluation in this area early on, to have some insight into approaches being taken in similar interventions and thus, to have informed discussions and make informed decisions regarding wellbeing evaluation within the work that they are undertaking.

• Understanding wellbeing and where it sits in the field of arts, culture and health is covered in Sections 3.0 and 3.1

• The factors to be kept in mind with regard to capturing benefits wellbeing and considering appropriate types of data are summarised in Section 3.2

• Section 4.0 focuses on the specifics of evaluating mental wellbeing benefits of arts and cultural interventions.

• Sections 4.1 and 4.2 take a closer look at qualitative and quantitative approaches to this task and, Section 4.3 examines the utility of the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale in more detail.

• Section 5.0 highlights the conclusions and learning based on the foregoing review.

• A biography of sources consulted comprises Section 6.0 and Section 7.0 is an initial mapping of relevant arts and cultural projects provided to give insight into the evaluation approaches taken.

7

3.0 Arts, Culture and Wellbeing – Creative Health

That participation in arts and culture-based pursuits can positively impact health is widely acknowledged,1 acceptance of this interrelationship is reflected at strategic and policy levels (i.e. Cayton, 2007; Cayton & Hewitt, 2007; Gordon-Nesbitt, 2022; Liikanen, 2010; Parkinson, 2021; Musella, 2021; Meadows & McLennan, 2022) where policymakers are increasingly striving to find ways to integrate arts and culture with the more traditional aspects of health and social care. Writing in an advisory capacity intended to assist the Department of Health in understanding ‘its role in relation to arts and health,’ National Director for Patient and Public, Harry Cayton, observed that ‘spending on arts and health is and should be seen as a legitimate, integral part of healthcare and good staff management and support, and entirely appropriate for NHS activity and investment, for instance for health promotion’ (Cayton, 2007). More recently, the Greater Manchester Integrated Care Partnership published their Creative Health Strategy, finding, on the basis of ‘[c]ompelling evidence (…) that engaging with creativity, culture and heritage helps us to lead longer, healthier, happier lives’. The term Creative Health denotes this elision of health and wellbeing which can ‘embrace activities that can enhance health and wellbeing in both direct and indirect ways’ (Gordon-Nesbitt, 2022).2

There is no shortage of literature surveying the myriad of interventions in the broad field of arts and health (i.e. Cayton & Hewitt, 2007; APPG, 2017; Fancourt & Finn, 2019; Staricoff, 2004). In their extensive study reviewing the evidence of the role of arts for improving health and wellbeing, Fancourt and Finn include over 900 publications among which – in turn – ‘over 200 [were] reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses covering over 3000 studies, and over 700 further individual studies’ (Fancourt & Finn, 2019). The breadth of this undertaking illustrates the wide-ranging character of the field. These authors cover – for example – how the arts affect social determinants of health, supports child development, encourage health promoting behaviours and engage marginalised and hard-to-reach groups as well as how they help to prevent ill health (Fancourt & Finn, 2019). Their findings – alongside those of Cayton and Hewitt, (2007) – show the wide-ranging uses to which the arts (and culture) can be put in the service of an equally broad gamut of potential health and related benefits.

1 The What Works Centre for Wellbeing has produced a number of scoping reviews on the wellbeing impact of a variety of arts and cultural activities. Available at: https://whatworkswellbeing.org/category/culture-arts-and-sport/ 2 Musella (2021) notes that ‘the recent establishment of the National Centre for Creative Health signals a strong commitment to understanding the contribution of arts and creativity to health and social care.’

Equally, any benefits to be gained might accrue to any number of people/ groups within our society. As Cayton and Hewitt summarise ‘many arts and health organisations and initiatives have been established for a number of decades, both in the UK and abroad. They involve individuals, groups and organisations from many different backgrounds including the state, private and not-for-profit sectors, artists, clinicians, art therapists, occupational therapists and managers. They serve a range of different people including those with disabilities, mental health problems, those with terminal illnesses and long-term health conditions, older people, carers, refugees and people from a wide variety of ethic origins’ (Cayton & Hewitt, 2007).

While intriguing, the scope of potential arts and health interventions is considerable, hinting at the possible challenges lying in wait for those attempting to evaluate the efficacy and, if possible, to assign causality to their work.

3.1 What is Wellbeing and How does it Fit Here?

The efficacy of some of the work undertaken in the arts and health space can be assessed in terms of more ‘traditional’/ tangible, metrics. For example, the Greater Manchester based Bronchial Boogie pilot which gave asthmatic school children the opportunity to learn brass and wind instruments3 to improve their lung health had impressive results whereby ‘[b]efore the lessons began, 35% of the pupils who took part had to take time off because of asthma. Now the figure is 5%. Previously, 45% of the pupils had difficulty participating in school sports. Now the figure is 15%’ (Lupton, 2004).4 In her review, Arts in Health: a review of the medical literature, Staricoff is able to identify ways in which arts interventions have brought about clinical effects; including reduction of anxiety and depression of cancer and cardiovascular patients (also see: Renton et al., 2012; Smith et al, 2012), reduction in length of stay on intensive care unit, improved pain management and reduced drug consumption (Staricoff, 2004).

While any of the above examples demonstrate improvements which might be understood to contribute to better health and by extension, improved (mental) wellbeing, it is useful to further define health per se and, to appropriately situate the notion of wellbeing within an understanding of health and the arts and culture space.

3 In combination with asthma education.

4 Evaluation of Sing and Breath – a singing for lung health intervention based in Salisbury that sought to ‘support and educate people with lung conditions in Salisbury to better manage their breath through singing’- set out to gauge success across a number of social vectors (i.e. peer support, reduction of social isolation, etc), clear that ‘the evaluation is not seeking to demonstrate measurable changes in clinical outcomes for participants and, evaluation methods are based on participants’ perceptions and self-reporting. Data collection intentionally did not seek information about clinical indicators such as reduced use of medication or increased peak flow’. However, where this kind of information has been offered by participants, it has been considered as qualitative data in the evaluation process (Farrally, 2020). Even where clinical improvement might be an expected outcome, depending on aims and objectives, it may not be a ‘useful’ metric for evaluative purposes.

9

Health can be understood from physical and mental perspectives (Fancourt & Finn, 2019). In its foundational constitution, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (cited in: APPG, 2017). As the preceding discussion implies these realms can easily overlap. For example, a person struggling with poor physical health may find that their mental health suffers as a result. Furthermore, while modern medical science is now more adept at coping with disease and infirmity than was the case in 1946 (when the WHO began its activities), the challenges of aging populations, chronic and social (i.e. alcohol, drugs, violence, poor mental health) disease are now foremost issues. This is recognised in WHO’s expanded definition of health which proposes that ‘health and wellbeing include physical, cognitive, emotional and social dimensions’ (APPG, 2017).

Though it is clear that health and wellbeing are linked concepts, it is nevertheless difficult to pin down the notion of wellbeing. Writing in their Inquiry Report for creative health, the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) wrestle with this task (also see: Oman, 2021 on interchangeability of terms). Outlining some of the attempts to define wellbeing, these authors note the lack of consensus in the area. They argue the utility of confining the focus of wellbeing to mental wellbeing (rather than including the physical as the WHO does) and also, of distinguishing wellbeing from mental health per se; i.e. low levels of wellbeing do not necessarily denote the presence of a mental disorder. Despite these difficulties, they foreground a useful construct developed through a Delphi consensus process5 and, identifying three aspects of wellbeing. These comprise the personal which ‘includes confidence and self-esteem, meaning and purpose, reduced anxiety and increased optimism; the cultural dimension [which] includes coping and resilience, capability and achievement, personal identity creative skills and expression and life skills such as employability;6 the social dimension [which] includes belonging and identity, sociability and new connections, bonding and social capital, reducing social inequalities and reciprocity’ (APPG, 2017).

As definitions go, this one is wide ranging. Recognising its scope allows for the acknowledgement of the ways that wellbeing can be substituted/ conflated with notions such as self-esteem and resilience. This is important as it allows for the inclusion of (particularly grey) literature where wellbeing is not directly mentioned but proxies, or related concepts, are. These factors contribute to wellbeing, and it is worth examining the measurement approaches taken.7

5 Here, the overarching approach is based on a series of ‘rounds’, where … experts are asked their opinions on a particular issue. The questions for each round are based in part of the findings of the previous one, allowing the study to evolve over time in response to earlier findings… [P]articipants are able to see the results of previous rounds—including their own responses—allowing them to reflect on the views of others and reposition their own opinions accordingly (Barrett & Heale, 2020).

6 Interestingly, in their interim evaluation of an arts for wellbeing social prescribing scheme, White and Salamon suggest that part of their evaluation went unanswered by all respondents as they did not necessarily ‘draw the link between arts participation and employment’ (White & Salamon, 2010).

7 There is a significant criminal justice literature pertaining to arts and culture-based interventions relating to desistance, wellbeing per se is not always a foremost metric but it is nevertheless clear that the outcomes of the intervention (and the changes in metrics) will contribute to improved wellbeing overall (i.e.: Caulfield et al., 2018; Massie et al., 2019; Froggatt & Breton, 2020).

3.2 How We Know Wellbeing through Data8

As the foregoing suggests, wellbeing is something of a contested area. This has consequences for the ways in which wellbeing might be captured in a measurable way, which – perhaps unsurprisingly – is attempted using a variety of methods.9 For the purposes of the discussion here, it is important to know that wellbeing data can be objective (i.e. mortality rates, higher educational attainment, economic sufficiency and stability) or subjective (i.e. life satisfaction, joy, contentment, hope). Subjective data can be viewed through the lens of the hedonic (i.e. transient happiness or contentment derived from doing what we like or, avoiding doing what we do not like) or the eudaimonic (i.e. more durable contentment deriving from meaning and purpose; a sense that the things one does in life are worthwhile). While there may be a tendency (especially prevalent in academic and policy settings) to prioritise numbery quantitative data over their wordy qualitative counterpart (Oman & Taylor, 2018), Oman is forthright in resisting ‘this assumption that any data is better than another because we read them as text or count them as numbers or collect them differently.’ Rather, she argues that ‘[a]ll well-being10 data might be valuable to understanding well-being. Whether they are qualitative or quantitative is not the issue at hand. Instead, context is the issue: where the data came from, are they used appropriately and how are they applied?’ (Oman, 2021).

Thus, while it is possible to measure (or attempt to measure) wellbeing as a numbery value (i.e. return on investment - ROI or social return on investment – SROI)11 this is not necessarily the most appropriate approach for capturing information pertaining to wellbeing (i.e. Oman, 2021).

8 Oman, 2021.

9 Oman (2021) provides an excellent precis of the ‘knowing’ of wellbeing through the lens of a history of data. The author’s premise – that data are, of course, coloured by the biases, interests and policy proposals of those who interpret them or commission their collection and collation – informs her enlightening overview of the types of data that can – and have – been used to evidence wellbeing.

10 Oman (2021) notes that the contestation around wellbeing extends to failure to agree on a single spelling. In her work, she prefers ‘well-being,’ and the original spelling is retained here.

11 Interestingly, Transported Art do include a ROI value in their evaluations of the arts and cultural projects that they undertake. It is notable, however, that they caveat the values assigned to activities as follows ‘these are monetised values but we avoid the £ sign which undermines the message that these [are] social and cultural, not financial values’. See: https://www.transportedart. com/about/evaluation/ . In their reports examining the social and wellbeing benefits of engaging with culture and sport, Fujiwara et al. employ methods and analyses which priorities ‘cashable or financial benefits and savings’ (2014) and subjective wellbeing using wellbeing valuation which draws on large data sets of individuals’ subjective wellbeing data ‘to assess the extent to which engagement in arts and sports impacts on people’s subjective wellbeing and then place[s] monetary values on these impacts’ (2014a). Musella discusses wellbeing valuation approaches and the use of wellbeing in policy appraisal noting that a ‘wellbeing valuation approach has helped build consensus of monetisation and value of subjective wellbeing impacts […] The HM Green Book Supplementary Guidance emphasises wellbeing as a key component in the assessment of costs and benefits to society. It introduces a simple but effective measure of wellbeing: the ‘Wellbeing-adjusted Life Year’ (WELLBY). This is defined as a one-point change in life satisfaction on a Likert scale between 0 to 10 for an individual for one year. The use of the WELLBY approach as a metric allows evaluators to capture the full social and economic benefits of cultural policy actions’ (Musella, 2021). MacLennan et al. (2021) and MacLennan & Stead (2021) examine the pros and cons of quantifying and monetising wellbeing effects using Social Cost Benefit Analysis (SCBA) approaches. It is not clear that any of the methodologies outlined are particularly appropriate for use with smaller scale interventions.

11

Further, where mental health is a particular focus, ‘outcomes have to be subjectively validated by the participants and […] intended outcomes may not translate straightforwardly into measurable health improvements on clinical scales.’ 12 Instead, ‘good observational data’ can play an important role here and the current move away from the traditional view of the evidence hierarchy increasingly favours ‘a combination of methods’ (APPG, 2017).13 Such an argument strongly implies that both validated survey measures and free text approaches14 to data gathering are the most appropriate answer to the question of How We (Might) Know Wellbeing through Data for evaluation of arts and cultural interventions aimed at supporting mental wellbeing.15 An approach comprising these elements provides the possibility to meaningfully capture data pertaining to the subjective wellbeing benefits of an intervention, is most appropriate for gaining insight into mental wellbeing and, if well administered, any change experienced by participants over time.

12 In this case the authors are arguing that clinical approaches including Randomised Control Trials (RCTs) are of limited utility (and often infeasible).

13 In their review of the interaction of arts, culture, health and wellbeing in the criminal justice sector, ACE note that a minority of studies captured in their literature search used biomarkers to detect changes in stress hormones such as cortisol or ‘to see whether and how far cultural engagement might affect the many mental health conditions that are characterised by underlying inflammatory immune responses’ (ACE, 2018). In this way, clinical/traditionally medicalised approach to measuring psychological/ mental wellbeing is utilised. It is also possible to track markers such as reduction in medication use or number of primary care visits. In their interim evaluation of a social prescribing programme, White and Salamon did not collect this data, ‘possibly due to […] [the] emphasis on being an non-medical intervention’. The same researchers question whether tracking medication and service use is particularly meaningful for the context they are investigating (White & Salamon, 2010).

14 Oman (2020) argues for free text approaches to the appraisal of wellbeing findings in her extensive work with the Office of National Statistics ‘Measuring National Well-being’ data set suggests that ‘people often preferred describing well-being in their own words to only sticking to the categories offered by the ONS’. Also, Ander et al. (2011) observe that scales seeking to standardise ‘what psychological wellbeing is’ can leave little space for individual voices which may ‘have a very different perspective on what makes them happy or well.’

15 In her review of literature contributing to her exploration of the measurement of the impact of arts and culture on wellbeing, Musella finds that the studies reviewed were multidisciplinary, ‘using both quantitative and mixed-method design to look at how and why wellbeing improves.’ Also, it is noteworthy that ‘quantitative studies that did not use a pre-post design were excluded from the review’ (Musella, 2021). MacLennan et al. (2021) also note that a mixed methods approach to identifying wellbeing benefits may be most appropriate.

4.0 Approaching Evaluation

The preceding discussion has examined creative health, wellbeing and the challenges of – and potential approaches to – measurement with specific reference to mental wellbeing. The following surveys some of the literature in which arts and culture-based approaches have been undertaken with target groups of participants for whom improved wellbeing or increased resilience (or similar) are desired aims and/ or, for whom an admission criterion to the participant group included a mental health challenge (i.e. anxiety, depression, dementia).

The aim of this segment is to provide some insight into the approach(es) taken to evaluation. As previously mentioned, evaluation per se, is not always central to the analysis and discussion being presented (this is particularly so for grey literature). In their work to develop an appropriate evaluation approach for projects operating in the realm of mental health, social inclusion and arts, Secker et al. (2007, also Hacking et al., 2006) found that only ‘two of the 102 projects included in the analysis were using validated outcome measures […] [and that] [m]ost projects were evaluating their work at only one point in time, precluding the measurement of change over time (Secker et al., 2007). Yet, their investigation demonstrated that gaining understanding of ‘distance travelled’ over the course of participation in a project was of particular importance. This team of researchers developed a baseline study16 to be administered at start and end (or post-end) of project and, which was recommended to be used in tandem with CORE17 as a suite of accessible tools that would be relatively straightforward to administer. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that ‘of 51 projects that initially expressed interest in assisting with the study [to test the tools], 22 recruited participants. The main reasons for projects deciding not to take part included doubts about their own capacity to help for funding or staffing reasons’ (Secker et al. 2007).

The Centre for Cultural Value reflected briefly on how the value of cultural participation is researched or evaluated, noting that qualitative approaches were generally preferred ‘to understand the value of cultural participation for older people’s sense of community, connection and wellbeing’. Predominantly, data were gathered using focus group, interview and observation techniques with a few of the studies reviewed drawing upon more participatory approaches (i.e. photo elicitation or documentary making).

16 Social inclusion is the focus of the baseline tool; it comprises scales to measure social isolation, social relations and social acceptance.

17 Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation: it is ‘a brief, user friendly, questionnaire measure intended to be used at the beginning of therapy to indicate the differences in the severity of problems people may have and to be used at intervals thereafter to measure change’ It comprises 34 statements, ‘scored by tick box completion on the same five response levels on all items’ (Evans et al. 2000).

13

At the same time, the authors observed that the literature under review was of variable quality, as the researcher/participant relationship had been inadequately accounted for, ethical issues were ill-considered and/or the interview or focus group had been far too brief to be certain that ‘the depth of older people’s experiences has truly been captured’ (The Centre for Cultural Value, 2022). The same review noted the use of a plethora of standardised measures in other work similarly seeking to illuminate ‘the value of cultural participation for older people’s sense of community connection and wellbeing’ (the authors list: Geriatric Depression Scale, WHO Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL-BREF), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale, UCLA Loneliness Scale) (Centre for Cultural Value, 2022).

4.1 Qualitative Approaches

The collection and analysis of narrative-type data is common. In their work on the use of participatory theatre for mental health recovery, Torrissen and Stickley rely on a narrative inquiry approach which prioritises the experiences of, and the stories told by, actors participating in activities of the Teater Vildenvei, a ‘semi-professional theatre company open to mental health service users and their allies’ (Torrissen & Stickley, 2017). Analysis of these narratives revealed that involvement with the theatre had enhanced wellbeing though the provision of ‘something meaningful to do, social contact, peer support and improved self-esteem’ (Torrissen & Stickley, 2017). Further, the authors underscore the fact that, their findings could be analysed against the mental health recovery framework established by Leamy at al. (2011) which identifies 5 areas for progress in terms of improved mental health and wellbeing: connectedness, hope, optimism, identity, meaning in life and empowerment. Carey and Sutton’s evaluation of a community arts project in Speke, Liverpool, report respondents’ ‘appreciation of the opportunity to discuss their experiences in interview’ though interviewees also note that they would have welcomed the chance to discuss their views at an earlier point in the project to provide ‘constructive, ongoing feedback’ (Carey & Sutton, 2004). Methodologically, such an approach would also provide the opportunity for comparative/ longitudinal analysis. These findings give credence to Oman’s (2020) argument that people often prefer describing wellbeing in their own words rather than assigning a point on a scale.18

In their research examining sectoral approaches to, and understanding of, programme evaluation, Daykin et al. found that ‘respondents reported the use of a wide range of evaluation methods, with extensive use of informal ‘anecdotal’ methods such as comment slips, feedback from artists and participants, practitioner diaries and ad hoc case studies.’ Other narrative type approaches – such as interview and focus group – were also employed though ‘quantitative methods and the use of validated assessment tools such as the WEMWBS […][were] reported less frequently’ (Daykin et al., 2017a).

Evaluating the ‘Making for Change’ project which provided female prisoners with the opportunity to develop skills for shortage occupations in the fashion industry, Caulfield et al. note that the project did not expressly set out to with the specific intention of addressing the participants’ wellbeing needs, however, many of the women did experience benefits to their health and wellbeing. This emerged during the evaluation which relied upon ‘observational, focus group, and interview data’ gathered from both women prisoners and project staff members (Caulfield et al., 2018).

4.2 Validated Approaches

Attempts to develop standardised tools to capture subjective wellbeing are not a sure-fire guarantee of successful evaluation. For example, designing a Wellbeing Measure’s Toolkit for use in museums, Thomson and Chatterjee (2015) trialled their measures among older adults who exhibited mild-to-moderate symptoms of dementia. Some of these respondents found the wellbeing questions posed were inappropriate, ‘one commenting that the questionnaire was ‘superficial’, and ‘about being happy’ and did not ‘reflect the vast range of older people at very different ages and stages of engagement’ (Thomson & Chatterjee, 2015). In their formative evaluation of ‘Arts for Wellbeing’ programmes delivered in County Durham, White and Salamon (2010) uncovered instances of music group participants finding the administration of a validated measure to track progression (in this case SF3619) to be ‘intrusive, stress-inducing and at odds with the relaxation aim of the activity’ (White & Salamon, 2010). Nevertheless, the wider literature shows that there is significant utility for validated scales in the field.20

18 Although her investigation focussed on effective partnership working for delivery of a music project, Currie (n.d.) suggests that ‘if participants’ musical experiences in the singing groups [comprising the mainstay of project activity], in relation to wellbeing, was to be the focus of the enquiry, than longer-term, imbedded ethnographic or practice-based approaches may be more appropriate’.

19 Available: https://tinyurl.com/2p8uxfts

20 It is worth noting that the Office for National Statistics has developed a set of 4 questions (known as the ONS4) to capture what they call personal (subjective) wellbeing in all its dimensions. These questions are: Life Satisfaction – Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?; Worthwhile – Overall, to what extent do you feel that the things you do in your life are worthwhile?; Happiness - Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday? And, Anxiety - On a scale where 0 is “not at all anxious” and 10 is “completely anxious”, overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday? Responses are given on a scale of 0-10. The ONS utilises these questions as part of the Measuring National Wellbeing (MNW) Programme which also includes a range of additional standard, objective measures (i.e. income, health). The ONS observes that ‘[t]hese questions represent a harmonised standard for measuring personal well-being, and therefore are used in many surveys across the UK.’ The ONS questions were not commonly used in any of the studies in this review, however, they could be a useful tool, particularly for large scale surveying or any situation for which concision and brevity are advantageous. See: https://tinyurl.com/yc82ruwm. Indeed, ONS4’s compactness could make them appropriate tools for garnering feedback on a session-by-session basis through the life-course of an intervention.

15

This ranges from the use of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale21 administered twice over the period of the intervention and analysed statistically to gauge the impact of participation in a singing group on new mothers’ experience of postnatal depression (Fancourt & Perkins, 2018), to the use of the CORE questionnaire for clinical assessment which provides ‘an overall measure of ‘mental distress’ with an established … cut off point and clinically significant change scores (Clift, 2012; also see Clift & Morrison, 2011). Elsewhere, Clift and Hancox make use of the WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) in tandem with a dozen-item ‘effects of choral singing scale’ to assess the physical, social, environmental and psychological wellbeing accrued from taking part in the named activity (Clift & Hancox, 2010).

In recognition of the challenges encountered when attempting to measure wellbeing, and in seeking to create an element of standardisation to assess and compare impact cross-sectorially, Thomson and Chatterjee (2015) describe their efforts to codesign a wellbeing measures toolkit for use in the museum sector. Working alongside industry stakeholders, the authors developed a toolkit to ‘measure psychological or subjective well-being as an indicator of the mental state of an individual and to be flexible in its approach in order to evaluate the impact of a one-off activity or whole programme of events’ (Thomson & Chatterjee). To develop the kit, the authors drew upon elements of a number of pre-existing tools.22

Tools based on a similar principle to CORE and WHOQOL-BREF – using statement questions against which respondents estimate the extent to which they agree or disagree (Likert scale) – are quite widespread. The What Works Centre for Wellbeing provides a Wellbeing Measures Bank comprising a wide variety of scales suitable for a range of circumstances alongside a simple signposting system to assist evaluation planners in selection of appropriate and accessible tools.23 Among the available validated tools, WEMWBS is used with some consistency. Daykin et al., (2017) used WEMWBS in tandem with GHQ12, a 12 item general health questionnaire; Smith et al., (2012) used the scale in tandem with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS; McElroy et al., 2021, used the short WEMWBS, Smith et al., (2012) used it to measure wellbeing, mental health and social support factors in a project spanning multiple indices of family circumstances alongside the Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ24). Also see Blodgett et al. (2022) who identified examples of WEMWBS’s use to evaluate interventions focussed on art, culture and environment in their wider review wellbeing evaluation research using WEMWBS.

21 The EPDS is a self-report, 10 item measure on a scale from 0-30 ‘with a ≥10 indicative of possible depression and higher scores indicating more severe depression’ (Fancourt & Perkins, 2018).

22 Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, Mental Wellbeing Impact Assessment, and People Assessing their Mental Health (PATH II). The scale developed was then distributed for initial testing alongside the already validated VAS (Visual Analogue Scale) and PANAS (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule) tools (Thomson & Chatterjee, 2015).

23 Available at: https://measure.whatworkswellbeing.org/measures-bank/

24 The MFQ is a 32-item questionnaire for depressive symptoms based on the DSM-III-R criteria for depression (Smith et al., 2012).

4.3 A Closer Look at WEMWBS

Designed with both general population mental wellbeing and project evaluation uses in mind,25 WEMWBS comprises a positively termed, 14-item scale ‘designed to measure positive mental health or mental well-being.’26 It includes both the hedonic and eudaimonic factors (Taggart et al., 2013). Though validated prior to its general usage, and for use among ethnic minorities (Stewart Brown et al., 2011; Taggert et al. 2013) and younger age groups (i.e. McElroy et al., 2021, Stewart-Brown, 2011; Clarke et al., 2011)27 researchers have undertaken work to evaluate its responsiveness in a variety of settings. Maheswaran et al. found that the combination of hedonic and eudemonic was likely the foremost reason for the scale’s efficacy at both individual and group levels (Maheswaran et al., 2012; also see Tennant et al. 2007). In earlier work, Tennant et al. (2007) concluded that WEMWBS had features in common with a number of other scales28 though, its lower correlations with the Emotional Intelligence and the single-item measure of life satisfaction indicated that WEMWBS ‘may be measuring a different concept’ (Tennant et al., 2007).

It is also important to note that, in their investigation of the appropriateness of WEMWBS among ethnic minority groups,29 Taggert et al. concluded that although their findings suggested that ‘the WEMWBS is acceptable across different cultural groups and sufficiently sound from a psychometric perspective to be valid in general populations surveys, there were areas where the tool’s appropriateness was less clear (Taggart et al., 2013). For example, these authors report both the difficulty in translating some of the concepts used in WEMWBS cross-culturally; the groups participating in this study discussed the significance of ‘spirituality as important to wellbeing as well as the concept of responsibility’ for one’s one mental welfare. Both of which are unrepresented in the WEMWBS instrument (Taggart at al., 2013). While Chinese respondents tended to be ‘dismissive of depression believing that it was over diagnosed in England’, there is no direct translation for the word ‘optimistic’ in Pashtun. Thus, although most Pakistani study participants ‘felt they understood the word, and some understood it as ‘happy for the future’ it was not clear that the expectation that things would work out well was understood’. In a similar way, young men across both study groups ‘interpreted the item ‘feeling interested in other people’ in a sexual context’ (Taggart at al. 2013). In their study, undertaken in a criminal justice setting, Daykin et al. (2017) note that using an approach – such as WEMWBS – which relies upon respondents reflecting upon and self-reporting their mental health can be challenging. In this particular research setting, security concerns meant that questionnaires were done in a group setting where ‘some participants engaged in banter, conferring and joking about answers’ (Daykin et al., 2017).

25 https://tinyurl.com/49rtsspk

26 The short version – SWEMWBS – comprises 7 items.

27 MacLennan et al. (2021) signpost some resources specifically designed for measuring child and young person wellbeing. These ‘complement the national measures of wellbeing… Some questions match those asked in the adult measuring national wellbeing programme […] others are specifically designed to reflect themes important for these age groups (e.g. talking to parents about things that matter, quarrelling with parents).’ The authors also note that WEMWBS and SWEMWBS are validated for use with children ages 13+ and 11+ respectively.

28 WHO-5, the Short-Depression Happiness Scale, Satisfaction with Life Scale and Scales of Psychological Wellbeing.

29 In this case English speaking Pakistani and Chinese participants.

17

White and Salamon (2010) also report some specific issues encountered with the administration of WEMWBS. In their evaluation of the social prescription programme Arts for Wellbeing, they found difficulty in tracking which of the WEMWBS responses had been submitted first (baseline) and last (endpoint/follow-up), leading to issues when attempting to track change across time.30 They also came up against very low return rates as very few participants completed and returned both the baseline and follow-up WEMWBS forms. There were also problems with ‘getting forms to artists on time’ for onward distribution. Participant responses were also found to be problematic on occasion; ‘some filled [WEMWBS] out very quickly and with not much thought, others didn’t understand why the NHS wanted to know if they were happy (suggesting association of the NHS with ill health, not positive emotions?)’. The whole process was time consuming and, ‘if these forms were filled out in session 6,31 you do not find out the longevity of the effects’ (Salamon & White, 2010). While some of these complications arise as a result of insufficient planning/readiness for those delivering the programme evaluation, their occurrence does underscore the need to plan for evaluation before a project is begun. Yet, even when planning is sufficient, a high response rate – comprising both start and endpoint responses – is not guaranteed.32

It is also worth bearing in mind, that although they acknowledged WEMWBS’s usefulness and uptake in the arts and health space, the authors of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing Inquiry Report note that ‘critics of WEMWBS point to its relentlessly upbeat nature and its failure to capture other factors impacting upon wellbeing, including socio-economic inequalities, the vagaries of daily life and the imminent end of enjoyable arts activities’ (APPG: 2017). This shortcoming might well be mitigated through the appropriate provision of narrative feedback options which could then be analysed in tandem with data deriving from any validated scale employed for evaluative purposes.

30 Late enrolment for some programme participants may also have contributed here with a missed first session resulting in no completion of a baseline form.

31 At the time of the evaluation, the programme under scrutiny ran for a maximum of 6 sessions for each participant.

32 In their rapid review of wellbeing evaluation research using WEMWBS, Blodgett et al. (2022) record a range of administration failures for which projects were excluded from consideration, i.e. administering WEMWBS only once, or at the start and end points of a 2 week or single event intervention for which the tool is not intended. On the other hand, ‘[a]nother series of interventions assessed WEMWBS before and after a 5-day multi-activity course, however as scores were also collected at follow-up points beyond two weeks, it was included’ (Blodgett et al. 2022).

5.0 Capturing the Benefits of Arts & Cultural Participation for (Mental) Wellbeing: some answers to the questions posed at the outset of this review

If the preceding discussion tells us anything, it is that there are potentially as many ways of attempting to evaluate arts and cultural interventions aimed at supporting participants’ mental wellbeing as there are novel projects and interventions to deliver. It is useful to look back at the questions set posed at the outset of this review and, consider how the foregoing assists us in attempting to answer them.

• What measures, particularly standardised, are commonly used to gauge wellbeing in projects focussed on arts, culture and mental health?

• A variety of standardised measures are available. They vary in terms of length though many are reasonably short (the longer version of WEMWBS – for example – comprises 14 items. The ONS4 comprises only 4 items though few examples of its use were uncovered for this review).

• The availability of such tools does not guarantee that intervention participants will fill them in, some may find engaging with validated tools intrusive and irksome no matter how carefully their design has been considered.

• Such tools are designed to be administered at least twice (start and endpoint/ post-endpoint of project) to give an indication of distance travelled.

• Such tools – appropriately administered - will only evidence certain aspects of the wellbeing journey experienced by project participants. It is likely good practice to team the use of a validated tool with the collection of qualitative feedback (interview, focus group, written responses) to address these gaps.

• Small scale projects may have difficulty demonstrating that the needle has moved using validated scales; data collection focussed on narrative responses may be far more suitable.

• If the project is short – only running for a few sessions or weeks – standardised tools are unlikely to be appropriate.

• What are the pitfalls/ challenges or examples of great practice?

• Studies examining the efficacy of evaluation approaches undertaken in this space note that effective evaluation is often challenging, both knowledge and available resource can be tricky issues.

• The existence of validated scales etc. does not guarantee that project participants will be willing to – or enthusiastic about – completion.

• Depending on an intervention’s target group, achieving meaningful compliance to utilise validated scales effectively can be challenging.

• Pairing an appropriately administered validated scale with collection of narrative feedback on the value of participation in the project is advisable.

• Several studies reviewed use more than one validated scale (alongside other tools), it is not clear that this is an advantageous approach.

• What, if anything, can we learn about proportional/appropriate application of tools?

• The use of an appropriately applied validated scale tool can provide a lot of useful information but there will be gaps.

• It is advisable to make use of a validate tool in tandem with collection of narrative/qualitative feedback.

• Some projects have attempted to generate SROI and ROI values as part of their evaluation.33 The meaningfulness of these figures (particularly with regard to mental wellbeing) can be questioned (see, for example: APPG, 2017).

• SROI and ROI data should be collected at significant scale if it is to be meaningful, it is unlikely to be appropriate for mid or small-scale projects.

• What, if anything, can we learn about data collection methods - and issues – i.e. collecting data from young people?

• Data collection can be challenging, this is particularly so among vulnerable groups who may engage inconsistently or, find filling in questionnaires etc. stressful and/or intrusive.

• Evaluation should be planned into a project from the outset, this is particularly true if the use of a validated scale is proposed as it should be administered at least twice in order to demonstrate distance travelled.

• Narrative/ qualitative data is a valid approach to collecting meaningful wellbeing data and its utility should not be disregarded.

33 For examples: https://www.transportedart.com/about/evaluation/

21

6.0 Bibliography

Ander, E., Thomson, L., Noble, G., Lanceley, A., Menon, U. & Chatterjee, H. (2011) Generic well-being outcomes: towards a conceptual framework for well-being outcomes in museums, Museum Management and Curatorship, 26:3

APPG (Arts, Health & Wellbeing) (2017) Creative health: The arts for health and wellbeing, Inquiry Report, The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing, London, (2nd edition)

Arts Council England (2018) Arts and culture in health and wellbeing and in the criminal justice system; a review of evidence, Arts Council England, November 2018

Barrett, D. & Heale, R. (2020) What are Delphi studies, Evidence Based Nursing, 23(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2020-103303

Blodgett, J., Kaushal, A. & Harkness, F. (2022) Rapid review of wellbeing evaluation research using the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Health Well-being Scales (WEMWBS), What Works Centre for Wellbeing, Kohlrabi Consulting, May 2022. Available at: https:// tinyurl.com/b5r5ctvh

Carey, P. & Sutton, S. (2004) Community development through participatory arts: Lessons learned from a community arts and regeneration project in South Liverpool, Community Development Journal, 39:2

Caulfield, L., Curtis, K. & Simpson, E. (2018) Making for Change - An independent evaluation of Making for Change: skills in a Fashion Training & Manufacturing Workshop, UAL, London College of Fashion, January 2018

Cayton, H. (2007) Report of the review of Art and Health Working Group, Department of Health, Leeds. Available at: http://www.artsandhealth.ie/wp-content/ uploads/2011/09/Report-ofthe-review-on-the-arts-and-health-working-groupDeptofHealth.pdf

Cayton, H. & Hewitt, P. (2007) A prospectus for arts and health, Arts Council England, London. Available at: http://www.artsandhealth.ie/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Aprospectus-for-Arts-Health-Arts-Council-England.pdf

Centre for Cultural Value (2022) Older people – culture, community, connection. Connecting through culture as we age, Available at: https://tinyurl.com/3bxcycwz, March, 2022

Clarke, A., Friede, T., Putz, R., Ashdown, J., Martin, S., Blake, A., Adi, y., Parkinson, H., Flynn, P., Platt, S. (2011) Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Validated for teenage school students in England and Scotland. A mixed methods assessment, BMC Public Health, 11:487

Clift, S. (2012) Creative arts as a public health resource: moving from practice-based research to evidence-based practice, Perspectives in Public Health, 132:3

Clift, S. and Morrison, I. (2011), Group singing fosters mental health and wellbeing: findings from the East Kent “singing for health” network project, Mental Health, and Social Inclusion, 15:2.

Clift, S. & Hancox, G. (2010) The significance of choral singing for sustaining psychological wellbeing: findings from a survey of choristers in England, Australia and Germany, Music Performance Research, 3:1

Cooper, P. (2013) Writing for depression in healthcare, British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(4)

Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S. Michie, S. Nazareth, I. & Petticrew, M. (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance, BMJ, 337:a1655

Currie, R. (n.d.) Working together: A research partnership project led by More Music and the International Centre of Community Music, Available at: https://spiritof2012. org.uk/insights/music-challenge-fund-music-for-health/?s=09

Daykin, N. & Joss, T, (2016) Arts for health and wellbeing, an evaluation framework, Public Health England, available at: https://tinyurl.com/bdeavb56

Daykin, N., de Viggiani, N., Moriarty, Y. & Pilkington, P. (2017) Music-making for health and wellbeing in youth justice settings: mediated affordances and the impact of context and social relations, Sociology of Health & Illness, 39: 6

Daykin, N., Gray, K., McCree, M. & Willis, J. (2017a) Creative and credible evaluation for arts, health and well-being: opportunities and challenges of co-production, Arts & Health, 9:2

Evans, C., Mellor-Clark, J., Margison, F., Barkham, M., Audin, K., Connell, J., McGrath, G. (2000) CORE: Clinical outcomes in routine evaluation, Journal of Mental Health, 9:3

Fancourt, D. & Finn, S. (2019) What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and wellbeing? A scoping review, Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report 67, World Health Organisation, Regional Office for Europe.

Fancourt, D., Warran, K. & Aughterson, H. (2020) Evidence summary for policy: The role of arts in improving health & wellbeing, Report to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Department of Behavioural Science & Health, UCL, April 2020

Farrally, N. (2020) Sing and breathe Salisbury music for wellbeing CIC, evaluation report, November 2020. Available at: https://soundsbettercic.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/03/Sing-and-Breathe-Salisbury-Evaluation-Report-Nov-2020.pdf

Froggett, L. & Ortega Breton, H. (2020) Building resilience and overcoming adversity through dance & drama (BROAD) 2019, research evaluation report, University of Central Lancashire, UCLan, June 2020

Fujiwara, D., Kudrna, L. & Dolan, P (2014) Quantifying the Social Impacts of Culture and Sport, DCMS, London, April 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/quantifying-the-social-impacts-of-sport-and-culture

Fujiwara, D., Kudrna, L. & Dolan, P (2014a) Quantifying and valuing the wellbeing impacts of culture and sport, DCMS, London, April 2014. Available at: https://tinyurl. com/2p5np7kz

23

Gordon-Nesbitt, R. (2022) Greater Manchester Creative Health Strategy, Greater Manchester Integrated Care Partnership, November 2022. Available at: https:// gmintegratedcare.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/gm-creative-healthstrategy-low-res.pdf

Hacking, S., Secker, J., Kent, L., Shenton, J. & Spandler, H. (2006) Mental health and arts participation: the state of the art in England, Journal of the Royal Society of Health Promotion, 126(3)

Isle of Wight Council (2014) Isle of Wight mental health strategy, 2014-2019, no health without mental health. Isle of Wight Council. Available at: https://www.iow.nhs.uk/ Downloads/Policies/No_Health_Without_Mental_Health_Strategy_Document.pdf

Liikanen, H-L. (2010) Arts and culture for well-being, proposal for an action programme 2010-2014, Publications of the Ministry of Education & Culture, Finland. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/jd9ve33c

Liu, Y-D. (2019) Event and sustainable culture-led regeneration: Lessons from the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool, Sustainability, 11:??

Lupton, M. (2004) Second wind, The Guardian (Tuesday 23rd March, 2004). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2004/mar/23/health.teaching

MacLennan, S. & Stead, I. (2021) Wellbeing discussion paper: monetisation of life satisfaction effect sizes, HM Treasury, Social Impacts Taskforce, July 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/green-book-supplementaryguidance-wellbeing

MacLennan, S., Stead, I., Little, A. (2021) Wellbeing guidance for appraisal: Supplementary Green Book guidance, HM Treasury, Social Impacts Taskforce, July 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/green-booksupplementary-guidance-wellbeing

Maheswaran, H., Weich, S, Powell, J. & Stewart-Brown, S. (2012) Evaluating the responsiveness of the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Group and individual level analysis, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10:156

Massie, R., Jolly, A. & Caulfield, L. (2019) An evaluation of the Irene Taylor Trust’s Sounding Out programme, 2016-2018, University of Wolverhampton, The Irene Taylor Trust, January 2019

McElroy, E., Ashton, M., Bagnall, A.M., Comerford, T., McKeown, M., Patalay, P., Pennington, A., South, J., Wilson, T. & Corcoran, R. (2021) The individual place, and wellbeing – a network analysis, BMC Public Health, 21:1621

Meadows, G. & McLennan H. (2022) Power of music: A plan for harnessing music to improve our health, wellbeing and communities, UK Music, Music for Dementia. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y83xxaun

Musella, M. (2021) Measuring the impact of arts and culture on wellbeing, Warwick UK Cities of Culture Project, available at: https://tinyurl.com/4b8djkcv

Oman, S. (2020) Leisure pursuits: uncovering the ‘selective tradition’ in culture and well-being evidence for policy, Leisure Studies, 39:1

Oman, S. (2021) Understanding wellbeing data, improving social and cultural policy, practice and research, New Directions in Cultural Policy Research, Palgrave McMillan

Oman, S. & Taylor, M. (2018) Subjective well-being in cultural advocacy: a politics or research between the market and the academy, Journal of Cultural Economy, 11:3

Parkinson, C. (2021) A social glue - Greater Manchester: A creative health city region, Manchester Institute for the Arts, Health & Social Change, Manchester

Renton, A., Phillips, G., Daykin, N., Yu, G., Taylor, K. & Petticrew, M. (2012) Think of your art-eries: Arts participation, behavioural cardiovascular risk factors and mental well-being in deprived communities in London, Public Health, 126

Secker, J., Hacking S., Spandler, H., Kent, L. & Shenton, J. (2007) Mental health, social inclusion and arts: developing the evidence base, National Social Inclusion Programme. Available at: https://www.artshealthresources.org.uk/docs/mentalhealth-social-inclusion-and-arts-developing-the-evidence-base/

Smith, N., Clark, C., Lewis, D., Thompson, C., Renton, A., Moore, D., Bhui, K., Taylor, S., Eldridge, S. Pettigrew, M., Greenhalgh. T., Stansfeld, S. Cummins, S. (2012) The Olympic Regeneration of East London Study (ORiEL): protocol for a prospective controlled quasi-experiment to evaluate the impact of urban regeneration on young people and their families, BMJ OPEN

Smith, N.R., Clark, C., Smuk, M. & Cummins, S. (2015) The influence of social support on ethnic differences in well-being and depression in adolescents: findings from the prospective Olympic Regeneration in East London (ORiEL) study, Social Psychiatry, Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50

Staricoff, R. L. (2004) Arts in health: a review of the medical literature, Arts Council England, Research Report 36. Available at: https://www.artshealthresources.org.uk/ docs/arts-in-health-a-review-of-the-medical-literature/

Stewart-Brown, S.L., Platt, S., Tennant, A., Maheswaran, H., Parkinson, J., Weich, S., Tennant, R., Taggart, A., Clarke, A. (2011), The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Health Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS): A valid and reliable tool for measuring mental wellbeing in diverse populations and projects, J Epidemiol Community Health 65 (Suppl 2): A38-A39

Strohmaier, S., Homans, K.M., Hulbert, S., Crutch, S.J., Brotherhood, E.V., Harding, E. & Camic, P.M. (2021) Arts-based interventions for people living with dementia: Measuring ‘in the moment’ wellbeing with the Canterbury Wellbeing Scales, Wellcome Open Research, 6:59, available at: https://tinyurl.com/39jnf4ew

Taggart, F., Friede, T., Weich, S., Clarke, A., Johnson, M. & Stewart-Brown, S. (2013) Cross cultural evaluation of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental health well-being scale (WEMWBS) – a mixed methods study, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11:27

Tennant, R., Hiller, R., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J. & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007) The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Health Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) development and UK validation, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5:63

Thomson, L.J. & Chatterjee, H. (2015) Measuring the impact of museum activities on well-being: developing the Museum Well-Being Measure Toolkit, Museum Management and Curatorship, 30:1

25

Thomson, L.J., Morse, N., Elsden, E. & Chatterjee, H. (2020) Art, nature and mental health: assessing the biopsychological effects of a ‘creative green prescription’ museum programme involving horticulture, artmaking and collections, Perspectives in Public Health, 140:5

Torrissen, W. & Stickley, T. (2017) Participatory theatre and mental health recovery: a narrative inquiry, Perspectives in Public Health, 138: 1

Transported (2016) Transported evaluation report: A small library, open book, mb Associates, Transported, Spring 2016. Available at: https://transportedart. com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/A-Small-Library-Transported-Open-BookEvaluation-2016.pdf

Transported (2016a) Transported evaluation report: Spalding’s hidden corners, mb Associates, Transported, Summer 2016. Available at: https://transportedart.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/06/Spalding-Transported-Evaluation-2016.pdf

White, M. & Salamon, E, (2010) An interim evaluation of the ‘Arts for Well-being’ social prescribing scheme in County Durham, Centre for Medical Humanities, University of Durham, October 2010.

A: Evaluation Mapping

7.0 Appendix

This mapping is intended to provide insight into the approaches that have been taken to evaluation in some projects, it is not exhaustive but comprises a selection of the evaluations gathered during the scoping for this work. That few of these interventions have set out to reflect specifically upon the efficacy of the evaluation approach taken as part of that process should be kept in mind.

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

https://tinyurl. com/2p9snkcj

WEMWBS

16 young adults & 6 peer mentors took part in 4-week pilot culminating in professional standard dance performance to invited audience. Participants began project with WEMWBS score in midforties, at completion this had increased by 10 points to 53.9 (clinically significant). Positive team and trust building opportunity, developing sense of community.

Delivered by Dance United alongside Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College, South London & Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Coaching and mentoring participants to produce a life dance performance of professional standard to be performed in front of audience as part of integrated recovery model in Early Intervention in Psychosis

Dance

Project

The Alchemy Project –Maudsley Charity, Guy’s & St Thomas’ Charity, ACE and others

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

https://tinyurl. com/49ny6wyf

WEMWBS & SWEMWBS supplemented by a referral form to collect demographic data and an ‘activity evaluation’ form administered on completion of sessions. Service-user focus groups. 2 facilitated & focussed conversations with artists & referrers 1-2-1 interviews with carers/facilitators

The evaluation undertook to understand:

1: Patient profile and their reasons for participating

2: GP, stakeholder & artist perceptions

Patient data gathered using questionnaires, phone interviews with GPs, stakeholders & artists.

11 patients referred for first 10-week block, 7 participated. All of whom attended between 5-10 sessions and were rereferred for the second block of 10-weeks.

Conceived as a preventative, nonmedical, accessible, flexible, demandled and evidencebased intervention. Commissioning services from approved list of approx. 20 artists and arts agencies to deliver activities to those referred in 6 weeks blocks.

Arts on prescription delivered through Darlington Arts Studio

Arts for Well-being’

–Primary Care Trust, County Durham

https://tinyurl. com/58v2xbc8

Nine patients participated in second block of 10 weeks’ duration, 8 of whom were classified as having completed the block at the endpoint.

Referral of patients for an 8-10 week art programme usually delivered in a community based or primary care setting.

Art on referral to address health and wellbeing

Artlift Wiltshire

29

Project

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

https://tinyurl. com/6z4bdf6t

WEMWBS alongside qualitative interviews, focus groups, consultation events, case study analysis.

Creation of evidence base re: benefits of creative activity and analysis of impact in both qualitative and quantitative terms.

Approx. 70 museums, Northumberland bait projects and commissions have utilised WEMWBS with 522 people completing the assessment

bait works in partnership to support more people in South-East Northumberland to create & take part in inspiring, high-quality arts experiences. All projects aim to build a stronger future with the people who live in the area. Museums with a focus on measuring wellbeing at a community level, particularly mental wellbeing in adults.

Project

Museums

Northumberland -bait.

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

https://tinyurl. com/k9dee9ef

Numerical mood data collected using Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale. Wellbeing data: WEMWBS. Both administered twice (start/ end). 18 participant interviews to discover pros/cons of approach. Analysis of WhatsApp conversations.

Numerical data showed ‘clinically meaningful’ increases in participants’ wellbeing.

People experiencing low mood and anxiety participated in 30 days of simple creative challenges. They shared their work and reflections on a facilitated WhatsApp group. There were 55 participants over the course of the intervention.

Co-created, online, creativity-based intervention to improve mood and wellbeing

Project

64 Million Artists

31

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

This project was not specifically wellbeing focused though wellbeing emerged as a benefit through evaluation. https://tinyurl. com/bdfnj89v

Interviews and focus groups, assessment of workshop learning, creative survey (exploring skills development), mapping industry need, recording course participants’ progression into further education & employment.

Workshops for delivery of highquality skills training, teaching industry standards for work. Tailored learner support, provision of work placements, monitoring, tailored support and coaching, independent evaluation.

Develop programme to support up to 30 women prisoners to develop skills for high quality garment manufacture, duration of min 6 months. Create training programme and deliver industry recognised qualifications. Source jobs for women eligible for release upon successful completion of course Reduce barriers to finding work post-release, reduce re-offending.

Training & manufacturing workshops for fashion industry from HMPS & London College of Fashion

Project

Making for Change

https:// tinyurl.com/ mwmbefap

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

Notes Tune In Programme

WEMWBS, Office for National Statistics personal wellbeing measure ( ONS4 ), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Text and video feedback using an app, recorded interviews on several occasions, entry and exit polling (conducted 11x across 5 locations at start and end of singing sessions).

Creation of singing groups to improve/ maintain employee wellbeing. Groups were regularly invited to perform at internal events. Each (of 5) group hosted a Christmas concert for friends, family and colleagues.

Delivery of choir/ singing based work to deliver programs that are effective in supporting the wellbeing and mental health needs of staff. In Tune comprised weekly, hour long lunchtime singing sessions.

On: Song runs choirs and singing workshops for companies and organisations. In this case Tune In is a collaboration between On: Song & Lloyds Banking Group.

Project

33

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

https://tinyurl. com/yx3hybw3

Formal evaluation took place for 5 months once groups had established themselves. CORE10 & full WEMWBS at baseline, 3 & 6 months. Qualitative feedback through questionnaire comments and semi-structured interview.

4 community singing groups ran weekly for period of just over 12 months. Data was gathered according to the framework delineated at the outset of the project.

Building on prior pilot to provide weekly singing for people with enduring mental health issues. To assess changes in mental distress and mental wellbeing using CORE10 & WEMWBS respectively. To gather qualitative feedback and to document project through photography and film.

Singing for people with persistent mental health challenges.

Project

Singing for Mental Health & Wellbeing (Kent & Medway)

35

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

Measure what matters! Feedback can be gathered in written, spoken or participatory ways. Likert scales are simple way to collect quantitative data. WEMWBS is easy to use and, correctly administered, enables comparison between different types of intervention.

Toolkit: available here .

Consolidation of knowledge and learning to assist other museums to bring aspects of health and wellbeing into their work.

Museum health and wellbeing evaluation toolkit developed with funding from Arts Council England & Canterbury City Council

Project

The Beaney Health & Wellbeing in Museums Toolkit

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

https://tinyurl. com/2p89yr7j

Focus groups (including creative elicitation i.e. collage), participant case studies, semi-structured interviews.

Improved self- management of chronic conditions, improved patient wellbeing (primary outcome), increased sharing and connection, confidence, motivation and selfesteem. 50 2hr arts workshops delivered. One artist training day, 50 artist-health worker debriefs.

Non-medical referral option to support existing treatments and support health & wellbeing, support improved patient self-management of chronic conditions, alleviation of symptoms of stress, social isolation, boredom, pain, anxiety, depression, mobility or dexterity issues. Enable sharing of experiences, improve quality of life outside hospital, improve support resource knowledge.

Arts and creative participation in supported settings to improve health and wellbeing

Project

Fresh Arts on Referral

ACE, North Bristol NHS Trust, Macmillan Cancer Support, Southmead Hospital Charity

37

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

CWS is a visual analogue scale consisting of five sub-scales designed for use by those with mild-to- moderate levels of dementia. See Strohmaier et al. (2021).

N.B. M4W is a social enterprise Community Interest Company (CIC).

Canterbury Wellbeing Scale, short-WEMWBS, social discussions, videoed vox pop comments, participant self-recording of ‘noteworthy’ incidences, participant observation focussing on creative outputs.

Total membership across groups 275, average group composition: 41% carer, 38% caredfor, 15% volunteers, 6% partner organisation staff. Project-specific online resource & Goals Framework for facilitators of arts health activities developed, mentor training for volunteer leaders, professional development for M4W facilitators of music and dance, launch of 2 similar local projects.

Delivery of programme for carers of people living with dementia and their cared-for, focussed on singing, rhythmic movement and dance for groups comprising representatives of both groups. Highlight event included visual arts & crafts, i-tablet photography, djembe drumming and song cycle writing.

Therapeutic and community engagement through music.

Project

Music 4 Wellbeing (M4W): Carers Create https://tinyurl.com/ bddr8kzw

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/ Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

https://tinyurl. com/59h6vs7k

Pre and post intervention questionnaires comprising general participant history, WEMWBS, Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD7) & Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). Weekly ‘luggage tag’ qualitative feedback. Participants asked to fill what they learned and discovered on one side and, express how this made them feel on the reverse. Participant observation.

Two blocks of 6 workshops were delivered with 3-week break at midpoint for review. Workshops comprised: making marks, print making, collage, willow weaving, stitch craft & textiles.

Participants were GP referrals or self-referrals from posters or from Improving Access to Psychological Therapies NHS programme.

All presented with some form of low-level mental ill health (i.e. anxiety, stress, depression). Pilot arts on prescription in NW Leicestershire, work with up to 12 patients experiencing low level MH issues. Improve mental wellbeing, anxiety and depression scores through delivery of art and craft activities supported by experienced practitioners, encourage exploration of how such practice might become sustainable in the long term, replicate other arts on prescription programmes (for efficacy).

Weekly sessions in which those referred carried out planned, self-contained, creative activities.

Arts on Prescription, North-West Leicestershire N-W Leicestershire District Council’s ‘Staying Healthy Partnership’ Grant

39

Project

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/ Outcomes

https://tinyurl. com/yckwse5a

Baseline and postcompletion ShortWEMWBS, analysed using paired-sample t-test to measure difference in wellbeing scores of the sample. Scores of each statement on the scale were also compared for a deeper analysis of wellbeing.

1,22,072 calls story calls placed to 32, 748 active listeners over 30 days. The project found a statistically significant improvement in participants’ emotional wellbeing, problem solving abilities, social relationships, and decision-making abilities.

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

A 30-day project using artsbased activities relayed through story telling phone calls to help participants manage stress and improve wellbeing.

A project to help 620,000 teenagers in Tamil Nadu, India, to improve their wellbeing during the COVID19 pandemic.

Project

Take it Eazy Nalada Way, Cities Rise, Unicef

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used

Outputs/ Outcomes

Description of Project, Target Group, Aims/ Objectives

Area of Intervention/ Evaluation

Evaluation found that ‘in the short term [the intervention] may in fact have increased demand for services by surfacing emotional issues with young people’

‘Monitoring’ (no further description) and WEMEBS (described as an administrative ‘burden’).

6 commissions delivered with young people’s involvement. Required monitoring and reporting completed. 655 young people participated ‘in-depth’, many taking cocreation roles.

Involve vulnerable young people in project, enabling them to practise the Six Ways to Wellbeing

Activities related to Six Ways to Wellbeing framework, delivering arts and culture-based interventions for young people based around the Six Ways and participate in festivals through the latter part of the pilot period

Project

Arts at the Heart of New Public Services / Six Ways to Wellbeing Kent County Council.

https://tinyurl. com/334rbzkz

41

Notes

Evaluation/ Tools Used