Insights in Sports social science

Edited by Hans Westerbeek, Gayle McPherson and Jess C. Dixon

Edited by Hans Westerbeek, Gayle McPherson and Jess C. Dixon

Published in Frontiers in Sports and Active Living

The copyright in the text of individual articles in this ebook is the property of their respective authors or their respective institutions or funders. The copyright in graphics and images within each article may be subject to copyright of other parties. In both cases this is subject to a license granted to Frontiers.

The compilation of articles constituting this ebook is the property of Frontiers.

Each article within this ebook, and the ebook itself, are published under the most recent version of the Creative Commons CC-BY licence. The version current at the date of publication of this ebook is CC-BY 4.0. If the CC-BY licence is updated, the licence granted by Frontiers is automatically updated to the new version.

When exercising any right under the CC-BY licence, Frontiers must be attributed as the original publisher of the article or ebook, as applicable.

Authors have the responsibility of ensuring that any graphics or other materials which are the property of others may be included in the CC-BY licence, but this should be checked before relying on the CC-BY licence to reproduce those materials. Any copyright notices relating to those materials must be complied with.

Copyright and source acknowledgement notices may not be removed and must be displayed in any copy, derivative work or partial copy which includes the elements in question.

All copyright, and all rights therein, are protected by national and international copyright laws. The above represents a summary only. For further information please read Frontiers’ Conditions for Website Use and Copyright Statement, and the applicable CC-BY licence

ISSN 1664-8714

ISBN 978-2-8325-2672-9

DOI 10.3389/978-2-8325-2672-9

About Frontiers

Frontiers is more than just an open access publisher of scholarly articles: it is a pioneering approach to the world of academia, radically improving the way scholarly research is managed. The grand vision of Frontiers is a world where all people have an equal opportunity to seek, share and generate knowledge. Frontiers provides immediate and permanent online open access to all its publications, but this alone is not enough to realize our grand goals.

Frontiers journal series

The Frontiers journal series is a multi-tier and interdisciplinary set of openaccess, online journals, promising a paradigm shift from the current review, selection and dissemination processes in academic publishing. All Frontiers journals are driven by researchers for researchers; therefore, they constitute a service to the scholarly community. At the same time, the Frontiers journal series operates on a revolutionary invention, the tiered publishing system, initially addressing specific communities of scholars, and gradually climbing up to broader public understanding, thus serving the interests of the lay society, too.

Dedication to quality

Each Frontiers article is a landmark of the highest quality, thanks to genuinely collaborative interactions between authors and review editors, who include some of the world’s best academicians. Research must be certified by peers before entering a stream of knowledge that may eventually reach the public - and shape society; therefore, Frontiers only applies the most rigorous and unbiased reviews. Frontiers revolutionizes research publishing by freely delivering the most outstanding research, evaluated with no bias from both the academic and social point of view. By applying the most advanced information technologies, Frontiers is catapulting scholarly publishing into a new generation.

What are Frontiers Research Topics?

Frontiers Research Topics are very popular trademarks of the Frontiers journals series: they are collections of at least ten articles, all centered on a particular subject. With their unique mix of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Frontiers Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area.

Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author by contacting the Frontiers editorial office: frontiersin.org/about/contact

June 2023 Frontiers in Sports and Active Living frontiersin.org 1

FRONTIERS

EBOOK COPYRIGHT STATEMENT

Insights in sports social science

Topic editors

Hans Westerbeek — Victoria University, Australia

Gayle McPherson — University of the West of Scotland, United Kingdom

Jess C. Dixon — University of Windsor, Canada

Citation

Westerbeek, H., McPherson, G., Dixon, J. C., eds. (2023). Insights in sports social science. Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA. doi: 10.3389/978-2-8325-2672-9

June 2023 Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2 frontiersin.org

13

21

55

68 “It's My Country I'm Playing for”—A Biographical Study on National Identity Development of Youth Elite Football Players With Migrant Background Klaus Seiberth, Ansgar Thiel and Jannika M. John

84 Portugal nautical stations: Strategic alliances for sport tourism and environmental sustainability

Elsa Pereira, Rute Martins, João Filipe Marques, Adão Flores, Vahid Aghdash and Margarida Mascarenhas

97 Building bridges: Connecting sport marketing and critical social science research

Zachary Charles Taylor Evans, Sarah Gee and Terry Eddy

102 Alone in the wilderness—Cultural perspectives to the participants' motives and values from participating in a danish reality TV-show

Søren Andkjær and Astrid Ishøi

June 2023 Frontiers in Sports and Active Living frontiersin.org 3 04 Editorial: Insights in sports social science Hans Westerbeek, Gayle McPherson and Jess C. Dixon

The Future Is Now: Preparing Sport Management Graduates in Times of Disruption and Change

James Weese, Michael El-Khoury, Graham Brown and W. Zachary Weese

07

W.

Waves of Extremism:

Ethnographic

the

Alberto Testa

An Applied

Analysis of

Bosnia and Herzegovina Football Terraces

Perspective: National Football League Teams Need Chief Diversity Officers Anne L. DeMartini and Barbara Nalani Butler

New Media, Digitalization, and the Evolution of the Professional Sport Industry Jingxuan Zheng and Daniel S. Mason 43 Arena-Anchored Urban Development Projects and the Visitor Economy Taryn Barry, Daniel S. Mason and Robert Trzonkowski

Shadow Stadia and the Circular Economy

Barry, Daniel S. Mason and Lisi Heise

30

49

Taryn

The

for Emerging Nations

Knott and Cem Tinaz

Legacy of Sport Events

Brendon

Table of contents

EDITEDANDREVIEWEDBY

JoergKoenigstorfer, TechnicalUniversityofMunich,Germany

*CORRESPONDENCE

HansWesterbeek hans.westerbeek@vu.edu.au

RECEIVED 09May2023

ACCEPTED 11May2023

PUBLISHED 26May2023

CITATION

WesterbeekH,McPhersonGandDixonJC (2023)Editorial:Insightsinsportssocial science.

Front.SportsAct.Living5:1219674. doi:10.3389/fspor.2023.1219674

COPYRIGHT

©2023Westerbeek,McPhersonandDixon. Thisisanopen-accessarticledistributedunder thetermsofthe CreativeCommonsAttribution License(CCBY).Theuse,distributionor reproductioninotherforumsispermitted, providedtheoriginalauthor(s)andthe copyrightowner(s)arecreditedandthatthe originalpublicationinthisjournaliscited,in accordancewithacceptedacademicpractice. Nouse,distributionorreproductionis permittedwhichdoesnotcomplywiththese terms.

Editorial:Insightsinsportssocial science

HansWesterbeek1*,GayleMcPherson2 andJessC.Dixon3

1InstituteforHealthandSport,VictoriaUniversity,Melbourne,VI,Australia, 2SchoolofBusinessand CreativeIndustries,UniversityoftheWestofScotland,Paisley,UnitedKingdom, 3FacultyofHuman Kinetics,UniversityofWindsor,Windsor,ON,Canada

KEYWORDS

sportbusinessinsights,socialscience,innovation,future,sportmanagementand marketing

EditorialontheResearchTopic

Insightsinsportssocialscience

Wearenowenteringthethirddecadeofthe21stCentury,and,especiallyinthelastyears, theachievementsmadebynaturalandsocialscientistshavebeenexceptional,leadingto majoradvancementsinthefast-growing fieldofSportsandActiveLiving.Thiscollection ofarticlesispartofaseriesofResearchTopicsacrossthe fieldofSportsandActive Living.Thismulti-disciplinary,editorialinitiativeisfocusedonnewinsights,novel developments,currentchallenges,latestdiscoveries,recentadvances,andfuture perspectivesinthe fieldofsportssocialscience.ThegoalofthisspecialeditionResearch Topicwastoshedlightontheprogressmadeinthepastdecadeinthesportsocial science field,andonitsfuturechallengestoprovideathoroughoverviewofthe field. ThisarticlecollectionthathascontributionsfromCanada,throughoutEurope,UK,USA andSouthAfricawillinspire,informandprovidedirectionandguidancetoresearchers inthe field.Thiscollectionconsidersthe findingsfrom11researchteamsthatfroma varietyofperspectiveshaveidentifiedcurrentchallengesinseveralsub-disciplines,and whohaveapplieddifferentmethodologiestoaddressthosechallenges.Thedifferent viewpointsarereflectedinthetypesofarticlesthatwereincludedintheResearchTopic, includingarticlescontainingoriginalresearch,perspectives,abriefresearchreport,a conceptualanalysis,andasystematicreview.Whatfollowsisabriefoutlineofthevarious projects.

TestaconductedastudyintoextremismintheBosniaandHerzegovina(BiH)football terraces,focusingonriskfactorsthatgovernthe “entry” ofBiHyouthintoextremehardcorefootballfansgroupsandprolongtheirinvolvementinthem.Thestudyprovided recommendationsforBiHpolicymakers,securityagencies,andfootballfederationsand clubstounderstandandeffectivelyrespondtothisthreatforpublicsecurityinBiH.

PartlyinresponsetotheglobalCovid-19pandemic, Weeseetal. proposed transformativechangesinwhatsportmanagementacademiciansteach,howtheyteach, andwheretheyteach,tofacilitateworkingin flexibleenvironmentsandacrossareas. Sportmanagementprofessorsareofferedsuggestionstohelpthemseizetheopportunities arisingfromthechangingsportslandscapeandemergingentrepreneurialventures.

TYPE Editorial PUBLISHED 26May2023 | DOI 10.3389/fspor.2023.1219674 Frontiersin SportsandActiveLiving 01 frontiersin.org 4

InapaperfocusingonparticipantsintheDanishversionofthe realityTV-showAloneintheWilderness(AIW),Andkjaerand Ishoiexploredtheirmotives,values,andexperiencesofbeing partoftheshow.Thestudyusedahermeneuticapproach,and theanalysiswasbasedona6-phasedthematicanalysis.The findingssuggestthatthemotivesandvaluesoftheparticipants reflectideasthatmayberelatedtothesoloexperienceandthe Nordictraditionoffriluftsliv(simplelifeintheoutdoors).The studypresentsnewempiricallybasedknowledgeonthemotives, values,andexperiencesofpeopleparticipatinginAIWandhow thesecanbeunderstoodaspartofoutdooreducationand recreationandasaculturalphenomenoninlatemodernsociety.

IntheUSA,theNationalFootballLeague(NFL)anditsteams facechallengeswithdiversity,equity,andinclusion(DEI).Intheir perspectivepiece,DeMartiniandButlerinvestigatedNFLteams’ utilizationoforganisationemployeesdedicatedtoDEI,utilizinga contentanalysisofpubliclyavailabledata.Their findings concludethatNFLteamslagbehindotherAmericanbusinesses intheiradoptionofChiefDiversityOfficer(CDO)roles.Only 31.25%ofNFLteamshadadedicatedDEIstaffperson.Three additionalteamshostdiversitycouncilsutilizingemployeeswith otherjobresponsibilities.Thestudysuggeststhattoaddress thesechallengesandmoveforward,NFLteamsshouldcreate CDOroleswithappropriatereportingrelationships,well-crafted positionresponsibilities,generousresources,andqualifiedand experiencedemployees.

Seibethetal. exploredstoriesofnationalidentitydevelopment fromtheperspectiveofyouthfootballplayerswithTurkish backgroundinGermanyouthelitefootball.Thestudyused10 expertinterviewsandbiographicalmappingstoidentifyspecific types,strands,andtrajectoriesofnationalidentitydevelopment. The findingsillustratethreetypesofnarrativesonnational identitydevelopment: “goingwiththenomination(s),” “reconsideringnationalbelonging,” and “addingupchances.” Thestudyconcludesthatnationalidentitydevelopmentinyouth elitesportisacomplexprocess.

Inapaperthataskedthequestionofhowarena-anchored urbandevelopmentprojects fitintoalocalcity’stourism economy, Barryetal. positionedprofessionalsportsteamsasthe anchortenantsofsportfacilitiestogeneratedevelopmentinthe city.Thestudydrawsdatafromtwocities,Columbus,Ohio,and Detroit,Michigan,usinginterviewswithleadersandcontent analysis.Theirresultsindicatethatgrowingthevisitoreconomy througharenaanchoredurbandevelopmentreliesonplanned placemaking via thestrategicapproachofbundlingdiverse amenitiestogether.These findingsprovidevaluablefeedbackto thosecitiesconsideringarenadevelopmentprojects,andhowthe arenasmaybecombinedwithothercivicamenitiestoundergird thelocalvisitoreconomy.

Intheirconceptualanalysis,ZhengandMasonarguedthatthe emergenceandproliferationofnewmediatechnologieshave drasticallychangedthemedialandscape.Thishascreateda muchmorecomplicatedcross-mediaenvironmentthatunites popularityandpersonalization,structureandagency.This

changingenvironmentcreatesindustrytransformations,and adaptingtothesetransformationswillleadtotheacceleratedand ongoingevolutionoftheprofessionalsportindustryandits successinthedigitalmediaage.

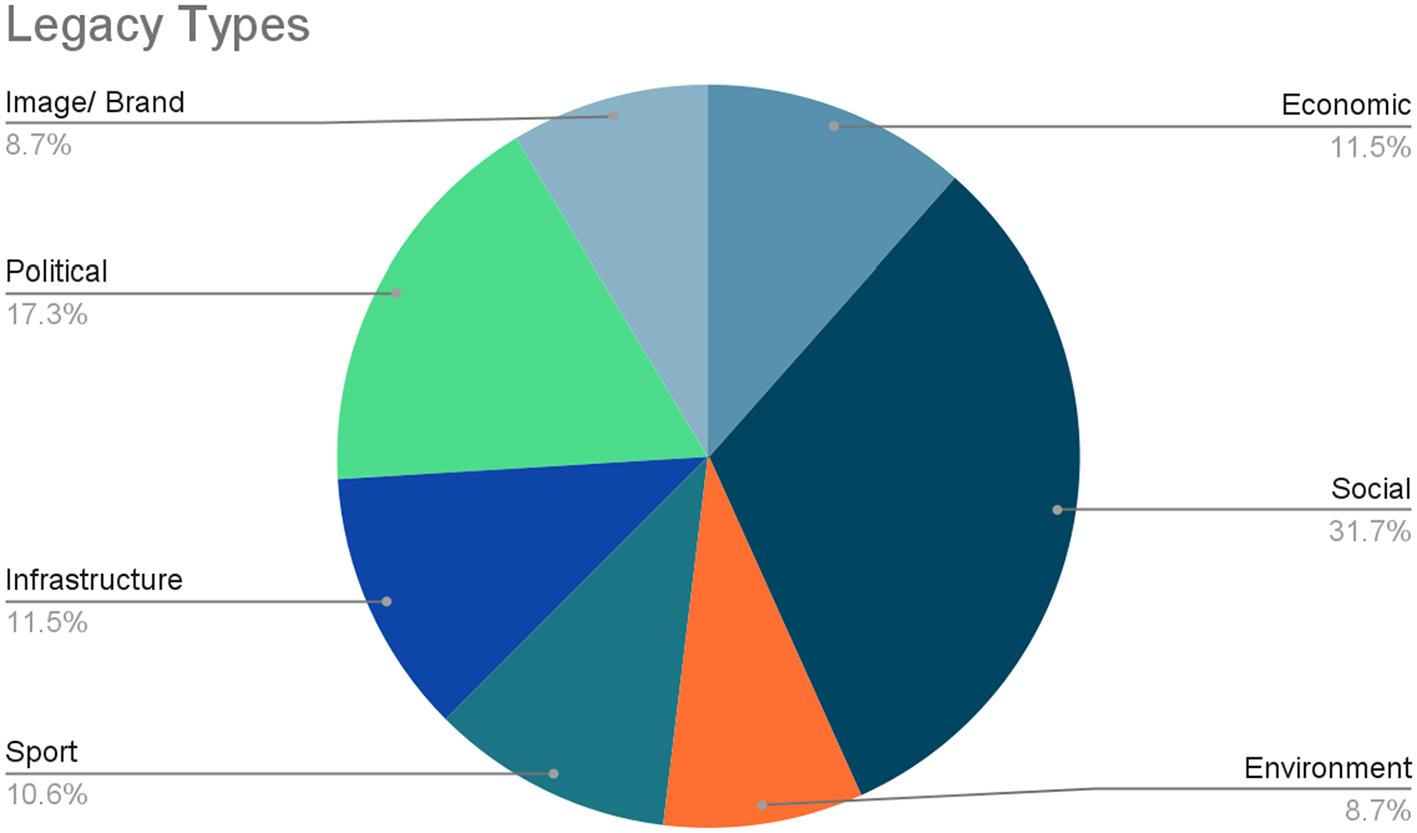

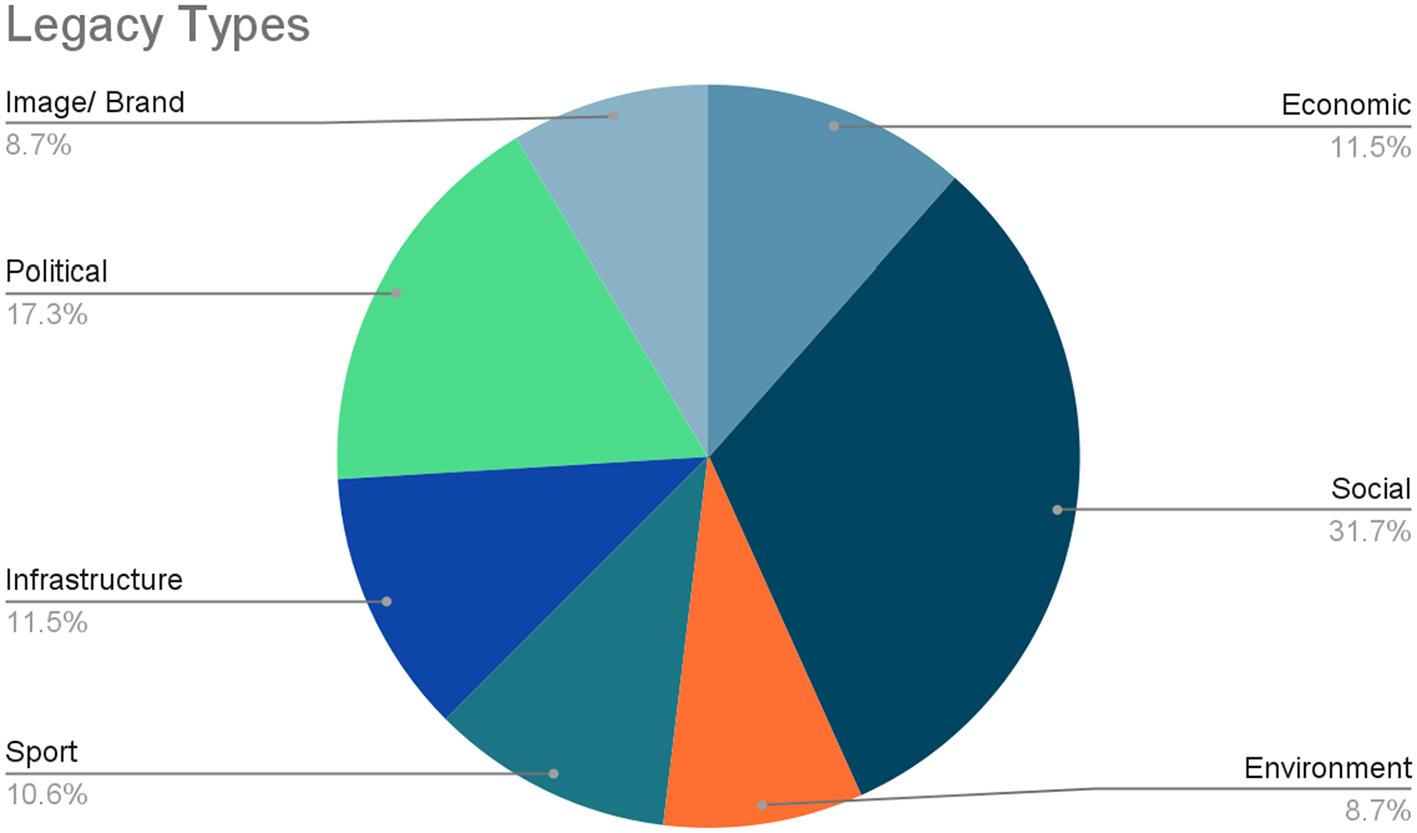

Emergingeconomiesareincreasinglyhostinglarge-scaleand megasporteventsastheyareviewedaskeyfactorsinlocaland nationaldevelopmentstrategies.KnottandTinazarguedthata varietyoflegacieshavepredominatedtheliteratureoverthepast twodecades.However,itisproposedthatthereisadifferencein thetypesoflegaciesanticipatedorrealisedwithinemerging economies.Therefore,thissystematicreviewaimedtodetermine thetypesoflegaciesanticipatedorrealisedbyemerging economiesasaresultofhostingsportevents,andtodetermineif thesedifferfromthoseofmoreeconomicallydevelopednations. Thestudyconfirmslegacyasagrowingbodyofknowledgein emerging nations, aligned withincreasingeventhosting.A conceptualisationofkeylegacyareasforemergingnationsis proposed,includingsocialdevelopment;politics,soft-powerand sport-for-peace;theeconomicsoftourism,imageandbranding; infrastructureandurbandevelopment;andsportdevelopment.

Theenvironmentalimpactsofshadowstadia,whicharethe facilitiesleftbehindafternewstadiumdevelopment,arenotfully understood.Limitedresearchexistsonhowtheimmediate neighbourhoodanchoredbypre-existingvenuescopeinthe shadowsofthesenewdevelopmentplansandthelossofasport venueanditsevents.Intheirperspectivearticle, Barryetal. discusscurrentadvancesintheacademicliteratureonthe circulareconomy.Theypresentacomprehensivecategorisation ofshadowstadiagloballyandfutureopportunitiesonintegrating circularityintobestpractices.Bydoingso,thisperspectivearticle highlightsseveralareasoffutureinvestigationthatshouldbe consideredandplannedforwhenmajorleaguesportsteamsand cityleadersmovetheirteamandbuildnewfacilities.

Sportmarketingresearchhasmuchtogainfromengagingwith criticalsocialscienceassumptions,worldviews,andperspectivesto examinecomplexissuesinsport. Evansetal. arguedthat, historically,sportmarketingresearchhasadaptedtraditional researchapproachesfromtheparentmarketingdisciplineto sport.Thispaperofferstworesearchpropositions,each accompaniedbyfouractionalrecommendations,toadvancethe fieldofsportmarketinginmeaningfulandimpactfulways.The paperemploysaparticularfocusonthemarketingcampaigns thatactivateandpromotecorporatepartnershipsinsportto framethetwopropositions,whichdiscussconsumerculture theoryandthecircuitofcultureastwoimportantframeworks thatbeginbuildingbridgesbetweencriticalsocialscienceand sportmarketingresearch.

Inthe finalarticleoftheResearchTopic, Pereiraetal. discussed theimportanceofnauticaltourismasapotentialproductto promoteanddeveloptouristdestinationsinEurope.Thestudy focusesonanalysingthestrategicalliancesestablishedbynautical stationsinPortugalforthedevelopmentofnauticaltourism products,includingtheirstrategicgoalsandsustainable environmentalpractices.Acontentanalysisof17Portuguese

Westerbeeketal. 10.3389/fspor.2023.1219674 Frontiersin SportsandActiveLiving 02 frontiersin.org 5

nauticalstations’ applicationformscollectedbetweenSeptember andDecember2021showedthatstrategicalliancesbetween nauticalstationshadmultiplestrategicobjectives,including structuringthetourismoffer,increasinggovernance,and promotingandmarketingnauticaltourism.Thestudyconcluded thatfuturescientificresearchisneededtooperationalizethe objectivesunderlyingtheformationofstrategicalliancesandthe environmentalpracticesdevelopedbynauticalstations.

Authorcontributions

Allauthorslistedhavemadeasubstantial,direct,and intellectualcontributiontotheworkandapproveditfor publication.

Conflictofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheresearchwasconductedinthe absenceofanycommercialor financialrelationshipsthatcould beconstruedasapotentialconflictofinterest.

Publisher’snote

Allclaimsexpressedinthisarticlearesolelythoseofthe authorsanddonotnecessarilyrepresentthoseoftheiraffiliated organizations,orthoseofthepublisher,theeditorsandthe reviewers.Anyproductthatmaybeevaluatedinthisarticle,or claimthatmaybemadebyitsmanufacturer,isnotguaranteed orendorsedbythepublisher.

Westerbeeketal. 10.3389/fspor.2023.1219674 Frontiersin SportsandActiveLiving 03 frontiersin.org 6

Editedby: HansWesterbeek,

VictoriaUniversity,Australia

Reviewedby: JerónimoGarcía-Fernández, SevillaUniversity,Spain

*Correspondence: W.JamesWeese jweese1@uwo.ca

Specialtysection: Thisarticlewassubmittedto SportsManagement,Marketingand Business, asectionofthejournal FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving

Received: 11November2021

Accepted: 31January2022

Published: 10March2022

Citation:

WeeseWJ,El-KhouryM,BrownG andWeeseWZ(2022)TheFutureIs Now:PreparingSportManagement GraduatesinTimesofDisruptionand Change. Front.SportsAct.Living4:813504. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.813504

TheFutureIsNow:PreparingSport ManagementGraduatesinTimesof DisruptionandChange

COVID-19disruptedtheworld,andtheimpactshavebeenexperiencedinmany areas,includingsportandhighereducation.Sportmanagementacademiciansneed toreflectonthepasttwoyears’experience,determinewhatworkedandwhatdid notwork,andavoidthetemptationofautomaticallyreturningtopastpractices.The authorsofthismanuscriptappliedthedisruptionliteratureandproposetransformative changesinwhatsportmanagementacademiciansteach(e.g.,greateremphasison innovation,entrepreneurship,automation,criticalthinkingskillstofacilitateworking inflexibleenvironmentsandacrossareas),howcolleaguesteach(e.g.,heightened integrationoftechnology,blendedlearningmodels)andwherecolleaguesteach (on-campusanddistaldeliverymodes,asynchronousandsynchronousdeliveryto studentsoncampusandacrossregions/countries).Examplesofstart-upcompaniesand entrepreneurialventuresareofferedtohelpillustratethechangingsportslandscapeand theemergingopportunitiesforcurrentandfuturestudents,graduates,andprofessors. Sportmanagementprofessorsareofferedsomesuggestionstoassisttheminseizing thisopportunity.

Keywords:disruption,highereducation,sportmanagement,preparation,COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

ThelateHarvardprofessorClaytonChristensenintroducedtheconceptof“disruptive innovation”tothebusinessliteraturebydescribinghownimbleandfuture-orientedorganizations didthingsdifferently,andindoingso,effectivelydifferentiatedthemselvesfromtheir competitors.Theseorganizationsaccuratelyforecastedtrends,preciselydeterminedemerging consumerwantsandneeds,andeffectivelydeliveredneworadaptedprogramsandservices thatheightenedtheircompetitiveadvantageandincreasedtheirmarketshare(Christensen andEyring, 2011;Christensenetal.,2011).Lessagileorganizationsledbyleaderswho refused toembracestrategicchangewerenegativelyimpactedandputoutofbusiness insomecases.Historyhasprovidedcountlessexamplesofcompaniesandindustriesthat havefollowedthiscourse. Estrin(2015) chronicledoneofthemostpoignantexamples of a companynotpayingattentiontothechangingtimesintheexampleofKodak.

PERSPECTIVE published:10 March2022 doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.813504 FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 1 March 2022|Volume4|Article813504

W.JamesWeese 1*,MichaelEl-Khoury 1,GrahamBrown 2 andW.ZacharyWeese 1 1 SchoolofKinesiology,WesternUniversity,London,ON,Canada, 2 CatapultCareerAdvantage,UniversityofWindsor, Windsor,ON,Canada

7

Thiscompanywasoncetheindustryleaderinthefieldof photography.Accordingto Estrin(2015),SteveSasson,ayoung engineer, pitchedthefuturisticideaofthedigitalcamerato thefirmin1975.Leaderssummarilydismissedtheideaand quicklypointedtoKodak’sleadershippositioninthefilmand imagereproductionareas.Unfortunately,theymissedthebigger picture,andwhenFujiandNikondevelopedtheirdigitalcamera 10yearslater,Kodakpaidtheprice.Fiveyearsafterthislaunch, Kodakwasoutofbusiness(Estrin,2015).

Other examplesofindustriesbeingdisruptedcanbeobserved inhowNiketrumpetedReebokintheathleticappareland footwearfieldsorhowNetflixtransformedthevideorental businesswithelectronicdeliverythatquicklyputBlockbusterout ofbusiness.ThinkoftheimpactthatbothUberandAirbnbhave hadontheride-sharingandhotelindustries.Organizationsmust anticipatechangesintheirindustryandadapttheirstrategies andpractices.Failuretodosoputsthematriskofbeingleft behind.COVID-19hasacceleratedtheneedforindustriesand theirpracticestoadapt(HuberandSneader,2021).

Industryleadersmustalsoembracetechnological advancements.Despitetheirrecententriesintothemarketplace, organizationsthathaveembracedinnovationandtechnology haveredefinedtheirindustriesandarethriving(e.g.,Amazon, Shopify,Google,Uber,Airbnb,SkiptheDishes). Huberand Sneader (2021) suggestedthatsomeofthepracticesforced onprovidersandconsumersduringCOVID-19willremain longafterthepandemicsubsides.Theyofferedexampleslike telehealth,e-commerce,andheighteneduseofautomationas examplesofthechangesnecessitatedbythepandemic,butlikely tobecomestandardpractice.

Furthermore,thestart-up/venturecapitalistculturehas riseninthe21stcenturyandhasdisruptedmanymarkets (Christensen,2003).Astart-upcompanyisdefinedasa newlyfounded organizationorentrepreneurialventure inthebeginningphasesofdevelopment(Cannoneand Ughetto, 2014).Theseorganizationsarenimble,meeta need, andareadaptable(Robehmed,2013).Accordingto Lee(2016),theyhaveadifferentorganizationalculture than traditionalorganizations.Theyrequireless“bricks andmortar”infrastructureandrelymoreonspacesthat facilitateideageneration,heightenedsynergy,andtechnology interfacesforremotecollaborations(Lee,2016).These characteristicsappealtomanyrecentgraduatesseekingan appropriateblendofchallengeandfreedomintheirwork experiences(Gabrielson,2019).Giventhedisruptiveforces impacting sport,theymayprovetobeagrowthareaforsport managementgraduates.

DISRUPTIVEIMPACTSONSPORT

Significantchangesaretakingplaceinhowsocietyengages insportasparticipantsandspectators.Attendanceatsome professionalsportingeventshasbeenindeclineinmanymarkets overthepastdecade(Stebbins,2017;Damgaard,2018;Suneson, 2019), andittypicallycomprisedofolderfans(Bryne,2020). COVID-19significantlyalteredattendancepatterns,andassome

suggest,permanently(Ratten,2020;Wilson,2021).Manysports leagueswereshutdown,andotherswererequiredtooperate withlimitednumbersofspectators.Outofnecessity,fanswere forcedtoconsumesportthroughtelevisionandsocialmedia vehicles(GoldmanandHedlund,2020;HullandRomney,2020). Mastromartinoetal.(2020) suggestedthatbroadcastingand socialmedia advancementshaveenrichedandtransformedthe fanexperience.Willfansreturntotheirpreviouswaysof physicallyattendinggamesoncethepandemicsubsides?Some (Mastromartinoetal.,2020;Ratten,2020;Wilson,2021)suggest that manywillnot.

Giventheconsumptionpatternshiftsandtheeconomic consequencesofCOVID-19,itisreasonabletoassumethat thetraditionalsizeofthesportsorganizationsthatpreviously employedourgraduateswillbesmaller,andthoseworking intheseorganizationsmightberequiredtodomorewith less.Somegraduatesmayneedtoassumeneworexpanded roles.Currentandfuturegraduateswillneedtobecritical thinkers,flexible,adaptable,andconfidentworkingacross disciplinaryareas.Somemaywishtostrikeoutontheir ownandusetheirentrepreneurialbackgroundstocreate theirownemployment(Escamilla-Fajardoetal.,2020).Some mayfind employmentinalternativesettingslikestart-up companies.Theserealitiespointtotheundeniablefactthat sportmanagementstudentswillneedanewkindofeducation— onethatpreparesthemtobehighlyadaptable,innovative,and progressive.Theywillneedtobeentrepreneurial.Theywill needtounderstandautomation(Johnson,2020)andtheimpacts that technologicaladvancementshaveonourfield,andtheir employmentprospects.

THESPORTANDTECHNOLOGY CONNECTION

Technologyandsporthavebecomeincreasinglydependent oneachotherduringtheCOVID-19period.Theauthors ofthismanuscriptandothers(e.g., Readwrite.,2018;Pizzo etal., 2018;Proman,2019; Reitmanetal.,2019; Finch etal., 2020)predictthattechnologywillexponentiallyincrease inthecomingyearscreateboundlessopportunitiesfor progressiveleadersinsportmanagement.Thisscenariomay beespeciallytrueforthosewhoembracestart-upindustries insport(e.g.,esport),whichwillusetechnologytokeep fixedcostslowandpenetrateemergingmarkets(Finchetal., 2020).

Thestart-upcompanyconceptoriginatedintheSilicon Valleyinthe1980s(LarsenandRogers,1984).According to Fontinelle(2020),start-upcompaniesemergedto develop anddeliveruniqueproductsorservicesthatcould moreeffectivelymeettheneedsofthemarketplace.These companiestypicallystartedsmallbeforeexpandinginto largerenterprises.Someoftoday’sleadingcompanies(e.g., Amazon,Shopify,Microsoft,McDonald’s,Apple)beganas start-upcompanies.

However,accordingto Au(2017),thesportsmarketplaceis one of themoredifficultsectorsfornewbrandstointegrate.In

Weeseetal. Preparing SportManagementGraduates

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 2 March 2022|Volume4|Article813504

Canada,thereareonlyafewincubatorsandsportslaboratories tosupport start-upcompanies.Some,likeRyersonUniversity’s FutureofSportLab,isajointeffortbetweentheuniversity andMapleLeafSportandEntertainment(MLSE)andisan incubationhubthatsupportsresearchandinnovationthatoften leadstopartnershipswithprivateorpublicfundinggroups (Start-upHereToronto,2019).TheUniversityofGuelphproudly supportstheInternationalInstituteforSportBusinessand Leadership(n.d),astart-upthatbringsacademicandindustry leaderstogethertoidentifyandpursueactionresearchprojects. Thesekindsofprogramsrepresentthenewthinkingthatis requiredinsportmanagement.Theemergenceofotherstartupcompaniesinsporthighlightstheexplosivegrowthof thisarea.

VirtualReality(VR)and,inparticular,esportsrepresenta rapidlygrowingsegmentinthesportsindustry(Jonassonand Thiborg, 2010;Funketal.,2018;Collis,2020),andbyextension, anareathatsportmanagementscholarsshouldintegrateinto theirteachingandresearchprograms.Whileinitiallydesigned forchildrenandyouth,interestandparticipationhavealso spawnedintoolderpopulations.Accordingto Clement(2021), therewere 2Bworld-widevideogamersin2015,andthenumber isexpectedtogrowto3Bby2023.The CanadianSportDaily (2020) supportedthisgrowthpredictionbyreportingthatthere were2.7B worldwidevideogamersbytheendof2020. Alton (2019) notedsimilar growthinviewershipofcompetitivegaming events.Shenotedthatesportshadaworld-widefanbasein excessof454M,upfrom380Min2018(Willingham,2018) andwasexperiencingagrowthrateofa14%peryear.In comparison,andpriortotheonsetofpre-COVID-19,the NCAAMen’s“MarchMadness”BasketballTournamenthad viewershipthatmaximizedat28M(Wilson,2021).Imagine theadvertisingandbrandingopportunitiesesportsprovides corporationslookingtoreachayoungandemergingmarket. Somespeculatethatesportsgameswillsoonbeincludedin majorinternationalevents,suchastheAsianGamesin2022 andtheParisOlympicsin2024(Kocadag,2019).Thefuturefor esportis bright(Mulcahy,2019).Advancementsin,andaccess totechnologywillfuelfuturegrowth.Thesamecouldbesaid foranothergrowthareainsport,namely,legalizedgambling. Onlinesportsgamblingisprovingtobeahighlyprofitable andpermanentfixtureimpactingsportsspectatorship.Aresport managementscholarsalsodiscussingthesedevelopmentsintheir classrooms,andaretheypreparinggraduatestocompetein thesetypesofemergingareas?Sportandsportmanagementhave beendisrupted,andasnotedbelow,sohavetheinstitutions traditionallypreparingsportmanagementgraduatesandleaders ofthefuture.

DISRUPTIVEIMPACTSONHIGHER EDUCATION

Kak(2018) and Levin(2021) havecalledforsignificant change inhighereducationforsometime.Theyargued thatthe20th-centurymodelsneedtobeupdatedinterms ofwhatistaughtandhowitisdelivered.Automation,

artificialintelligence,hologramtechnology,andadvances intelecommunicationsofferunlimitedopportunitiesfor changinghowacademicprogramscanbeconstructed anddelivered.

Govindarajanetal.(2021) suggestedthatCOVID-19has accelerated thechangeprocess.AsaresultofCOVID-19, lecturetheatersandcampuseswereabandoned,andprofessors wereforcedtointegratetechnologyandimplementremote teachingstrategiesfortheirstudents.Naturally,therewere bumpsalongthewaygiventhissuddenshift.Professors andstudentsbothclaimedtohavemissedtherelationshipbuildingaspectsthatin-persondeliveryofferstosupportand inspirelearning.However,whilemanystudentsandprofessors struggledwiththisadaptationandlongedforpre-pandemic practices,somestudentsandprofessorsthrivedinthisnew environment.Manywouldlikesomeofthesenewpractices tocontinue.Somestudentshavereportedthattheylikedthe paceandflexibilityoftakingtheirclassesremotelyandin anasynchronousformat.Manystayedathomeandsaved moneypreviouslyspentontransportation,accommodations, andparking.Professorsfoundthattheheighteneduseof technologycouldenrichtheircourses.Smallgroupdiscussions couldbeeffectivelyfacilitatedthroughvirtualchatrooms. Professorscouldintegrateinternationally-renownedexpertsinto theircourseswhodidn’tneedtotraveltodeliverguestlectures. Insomesectorsofourcampuses,productivityincreased.The pandemicprovedthattherewereotherwaysofdeliveringhigher education,andonceagain,necessityprovedtobethe“mother ofinvention.”

Asaresult, Levin(2021) and Govindarajanetal.(2021) encouragedprofessorsandprogramleaderstoreflectdeeply ontheneedsofstudents,thecontentofcourses,andbe opentoadoptingsomeofthepracticesthathadtobe implementedduringthepandemic.Perhapsprograms,courses, orpartsofeachcouldbemoreeffectivelydeliveredinvirtual orahybridofvirtualandface-to-faceformats.Theymade acaseforprogressivelyintegratingmoredigitaltechnologies (e.g.,remotedelivery,holograms)toenrichlearning.Some studentsmaypreferthebenefitsofremotedelivery(orperhaps somecombinationoftimeoncampusandtimeinremote deliverymodes).Ifthisdeliveryoptionexists,newcohorts ofstudentsmightbedrawntothesector.Recognizingthe benefitsandcostsavingsofsomeremotelearning,inwhole orpart,mightpromptsomeinstitutionstoreducetheir infrastructurefootprint.Somecampusescouldadoptablended modelwherestudentsinthefirstandfinalyearshaveanoncampusexperience,whilethoseinthemiddleyearsconsume theirprogramsfromaremotesetting.Someofthemore reputableinstitutionsmaytakethisopportunitytosignificantly expandtheirhigh-demandprogramspreviouslyrestrictedby spacerealities.

Thinkofthecostsavingsforsomestudentsiftheydidnot havetobeoncampusfortheirentireuniversityexperience. Thinkofprogramexpansionopportunitiesifcourses,programs, orpartsofprogramscouldbedeliveredthroughdistance education.Considerthecostsavingsifuniversitiescouldmore discriminatelyrationalizeprogramofferingandefficientlyshare

Weeseetal. Preparing SportManagementGraduates

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 3 March 2022|Volume4|Article813504

coursesorpartsofprogramswithotherinstitutions.Incremental revenuecouldbegeneratedfromsellingorrentingsomefreeduplandorbuildings.Thehighcostsofconstructingand operatingfacilitiescouldbereduced.Programofficialscould offermorecoursesinasynchronousformatssostudentscould consumetheircoursesatapaceandtimethatisadvantageousto them.Academicleadersandgoverningboardsmoreeffectively future-proofhighereducationbyadoptingsomeofthese practices.Fiscalrealitiesandsocietalpressuremightdemand suchaction.

Itisachallengingtime,andneithersportnorsport managementeducationalprogramsareimmunefrom thedisruptiveforcesandseismicchangesoutlinedabove. Graduatesarenowenteringemploymentopportunities thatarelessstructured,morefluid,andlesspermanent (Vedderetal.,2013).Thesituationhasbeenexponentially accelerated bytheeconomicandlabormarketdisruptions ofCOVID-19(Gentilinietal.,2020).Boldquestions mustbe addressed.Arecolleaguesdeliveringwhatsport managementstudentsneed?Aretheypreparinggraduates tobethoughtleaderswhoareentrepreneurial,independent, andconfidenttonavigatecareersintimesofrapidsocietal change?Aregraduatescriticalthinkerswhocanadaptand workacrossanumberofareasgiventheanticipatedsmaller workforces?Isthecontentofsportmanagementprograms cutting-edgeandprogressive?Arethetuitionandrelated educationalcoststructuresforstudentsrealisticandaffordable giventhemarketforces,valuepropositions,andeconomic times(i.e.,currentandpredicted)?Sportmanagement colleaguesmustadapttothrivegiventhechangestaking placeinsport,sportmanagement,andhighereducation (ChristensenandEyring,2011;Christensenetal.,2011).

CONCLUSION

COVID-19hasbeenadevastatingvirusthathasdisrupted societyininnumerableways.Itwillalsohavefar-reaching implicationsoninstitutionsofhigherlearningandintheways thatsocietyparticipatesorconsumessport.Organizationsthat prevailwillbenimble,progressive,andinnovative.Implementing someorallofthesuggestionsoutlinedbelowcouldimprove andmodernizeouracademicprograms.Colleaguescanlead changeby:

1.Developinganddeliveringacurriculumthatcoversthe traditionalareaslikeleadership,finance,economics,analytics, aswellastheemergingareasinthefieldlikeinnovation, entrepreneurship,automation,artificialintelligence,and start-upcompanies.

2.Expandingexperientiallearningopportunitiesforstudents beyondthetraditionalsportsettingsandinclude opportunitiesinemergingorganizationslikestart-up companies.Studentsneedtounderstandtherulesof engagementinemergingtechnologiesandtherealitiesof workinginagile,risk-takingventures.

3.Implementinghigherlevelsoftechnologyintothecurriculum tobringworldexpertsintothedigitalclassrooms.Industry leaders(fromacrosstheglobe)canbebeamedintodigital classroomswithminimalexpenseviaZoomorhologram technologies.Technologicaladvancementsallowforvirtual meetingroomswheresmallergroupsofstudentscanhave deeperdiscussionsandreflectionsessions.

4.Usingtechnologytosharecoursesandprofessorsbetween campusesandexpandingdigitalplatformstoreachmore studentsinsynchronousandasynchronousformats.Many universitiesarefacingfiscalchallenges.Coursesbetween campusescouldbesharedtoenrichtheexperienceand preparationofstudentsatlittleornocosttothehost institutions.Sportmanagementcouldbeleadersinthis synergisticapproach.

5.Ensuringthatguestspeakers,casestudies,andclassroom examplesaredrawnfordiversefields(e.g.,start-up companies,venturecapitalists,e-sports,gaming,fantasy sports,sportsgambling)inadditiontothosefromtraditional sportssettings.

6.Expandingexperientiallearningopportunitiesforstudents byinvestingincasecompetitionsthatincludeexamples fromstart-upcompaniesandotheremergingareasinthe field.Theserichlearningopportunitiesallowstudentsthe opportunitytoapplycoursecontentand,ifalsodrawnfrom emergingindustries,canhelpkeeptheprogramcurrent. Toincreaseapplicationandunderscorerelevance,have practitionersposethechallengequestionandinvolvethemin evaluatingtheproposedsolutions.

TheimpactofCOVID-19hasacceleratedtheneedfor changeinsport,sportmanagementandintheinstitutions thathousesportmanagementeducationalprograms. Sportmanagementcolleaguesareencouragedtoreflect onthesuggestionsoutlinedaboveandensurethatthe programsdeliveredtostudentsalignwiththecurrent andemergingdevelopmentsintheindustryandin highereducation.

DATAAVAILABILITYSTATEMENT

Theoriginalcontributionspresentedinthestudyareincluded inthearticle/supplementarymaterial,furtherinquiriescanbe directedtothecorrespondingauthor.

AUTHORCONTRIBUTIONS

JWtooktheleadinthepreparationofthisarticle.ME-K,GB, andZWareformerstudentsandsportmanagementleaderswho haveexperienceintheindustry,recognizethedisruptionthat hastakenplaceinrecentyears,andhaveexperienceworking withrecentgraduatesofoursportmanagementprograms,and providedhelpfulinsightsandexamplesthathavebeenintegrated intothisarticle.Allauthorscontributedtothearticleand approvedthesubmittedversion.

Weeseetal. Preparing SportManagementGraduates

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 4 March 2022|Volume4|Article813504 10

REFERENCES

Alton,L. (2019). HowbigwillESportreallyGet? Availableonlineat:https:// community.connection.com/how-big-will-esports-really-get/(accessed October21,2021).

Au,T.(2017). AsRemarkableGrowthoftheSportsIndustryContinues, ExclusiveDataAnalysisRevealstheKeyTrademarkTrends.Available onlineat:https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=18a78c6e-4ee9444c-8889-a039583c54a7

Bryne,H.(2020).ReviewingFootballHistorythroughtheUKwebarchive. Soccer Soc. 21,461–.Availableonlineat:https://art1lib.org/book/81830772/f71b05 (accessedFebruary8,2022).

CanadianSportDaily(2020). TheGrowthofesports.Availableonlineat:https:// sirc.ca/knowledge_nuggets/the-growth-of-esports/(accessedOctober5,2021).

Cannone,G.,andUghetto,E.(2014).Bornglobals:across-countrysurveyon high-techstart-ups. Int.Bus.Rev.23,272–283.doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013. 05.003

Christensen,C.M.(2003). TheInnovator’sDilemma:TheRevolutionaryBookThat WillChangetheWayWeDoBusiness.NewYork,NY:HarperCollins.

Christensen,C.M.,andEyring,.H.J.(2011). TheInnovativeUniversity:Changing theDNAofHigherEducationFromtheInsideOut.SanFrancisco,CA:JosseyBass.

Christensen,C.M.,Horn,M.B.,andJohnson,C.W.(2011). DisruptingClass: HowDisruptiveInnovationWillChangetheWaytheWorldLearns.NewYork, NY:McGraw-Hill.

Clement,J.(2021). NumberofVideoGamersWorldwide2015-2023.Statista. Availableonlineat:https://www.statista.com/statistics/748044/number-videogamers-world/(accessedOctober7,2021).

Collis,W.(2020). TheBookofEsports.NewYork,NY:RosettaBooks.

Damgaard,M.(2018). WhyIsGameAttendanceDecliningWhenFansAre BecomingSuperfans?Availableonlineat:https://blog.mapspeople.com/ mapsindoors/why-is-game-attendance-declining-when-fans-are-becomingsuper-fans

Escamilla-Fajardo,P.,Nunez-Pomar,J.,M.,Calabuig-Moreno,F.,and Gomez-Tafalla,A.M.(2020).EffectsofCOVID-19pandemiconsports entrepreneurship. Sustainability 12,1–12.doi:10.3390/su12208493

Estrin,J.(2015). Kodak’sfirstdigitalmoment.TheNewYorkTimes. Availableonlineat:https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/08/12/kodaks-firstdigital-moment/

Finch,D.J.,O’Reilly,N.,Abeza,G.,Clark,B.,andLegg,D.(2020). Implications andImpactsofesportsonBusinessandSociety:EmergingResearchand Opportunities IGIGlobal. doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-1538-9(accessedFebruary 8,2022).

Fontinelle,A.(2020). Startup.Availableonlineat:https://www.investopedia.com/ ask/answers/12/what-is-a-startup.asp Funk,D.C.,Pizzo,A.D.,andBaker,B.J.(2018).eSportmanagement.Embracing esporteducationandresearchopportunities. SportManag.Rev.21,7–13. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2017.07.008

Gabrielson,C.(2019). 12SportsTechStart-UpstoWatchin12markets.Available onlineat:https://www.americaninno.com/colorado/inno-insights-colorado/ 12-sports-tech-start-ups-to-watch-in-12-markets/ Gentilini,U.,Almenfi,M.,andOrton,I.(2020). SocialProtectionandJobs ResponsestoCOVID-19:AReal-TimeReviewofCountryMeasures“Living Paper.”Availableonlineat:https://www.bin-italia.org/wp-content/uploads/ 2020/04/Country-social-protection-COVID-responses_April3-1-1.pdf

Goldman,M.M.,andHedlund,D.P.(2020).Rebootingcontent:broadcasting sportandesportstohomesduringCOVID-19. Int.J.SportCommun.13, 370–380.doi:10.1123/ijsc.2020-0227

Govindarajan,V.,Srivastava,A.,Grisold,T.,andKlammer,A.(2021). Resist OldRoutinesWhenReturningtoCampus:AFour-StepFrameworkfor IdentifyingandRetainingtheBestCOVID-EraPractices.Boston,MA:Harvard BusinessPublishing.Availableonlineat:https://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiringminds/resist-old-routines-when-returning-to-campus Huber,C.,andSneader,K.(2021). TheEightTrendsThatWillDefine2021-and Beyond.McKinsey&Company.Availableonlineat:https://www.mckinsey. com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/theeight-trends-that-will-define-2021-and-beyond

Hull,K.,andRomney,M.(2020).“Ithaschangedcompletely”: howlocalsportsbroadcastersadaptedtonosports. Int.J.SportCommun.13,494–504doi:10.1123/ijsc. 2020-0235

InternationalInstituteforSportBusinessandLeadership(n.d.).LangSchoolof Business,UniversityofGuelph.Availableonlineat:https://www.uoguelph.ca/ lang/sport Johnson,R.(2020). StartingaCareerinArtificialIntelligence.BestColleges Availableonlineat:https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/future-proofindustries-artificial-intelligence/ Jonasson,K.,andThiborg,J.(2010).Electronicsportsanditsimpact onfuturesports. SportSoc.13,287–299.doi:10.1080/174304309035 22996

Kak,S.(2018). Willtraditionalcollegesanduniversitiesbecomeobsolete? SmithsonianMagazine.Availableonlineat:https://www.smithsonianmag. com/innovation/will-traditional-colleges-universities-become-obsolete180967788/

Kocadag,M.(2019).Investigatingpsychologicalwell-beinglevelsofteenagers interestedinsportcareer.Res.Educ. Psychol.3,1–10.(accessedJune1,2019). Larsen,J.K.,andRogers,E.M.(1984). SiliconValleyFever:GrowthofHigh TechnologyCulture. NewYork,NY:BasicBooks.

Lee,Y.S.(2016).Creativeworkplacecharacteristicsandinnovativestart-up companies. Facilities 34,413–432.doi:10.1108/F-06-2014-0054

Levin,A.(2021). TheComingTransformationofHigherEducation.AScorecard. InsideHigherEducation.Availableonlineat:https://www.insidehighered.com/ views/2021/06/14/seven-stepshigher-ed-must-take-keep-pace-changes-oursociety-opinion

Mastromartino,B.,Ross,W.J.,Wear,H.,andNaraine,M.L.(2020). Thinkingoutsidethe“box”:adiscussionofsportsfans,teams,andthe environmentinthecontextofCOVID-19. SportSoc.23,1707–1723. doi:10.1080/17430437.2020.1804108

Mulcahy,E.(2019).Five ofthebiggestsportsmarketingtrendsof2019. The Drum.Availableonlineat:https://www.thedrum.com/news/2019/05/14/5-thebiggest-sports-marketing-trends-2019

Pizzo,A.D.,Na,S.,Baker,B.J.,Lee,M.A.,Kim,D.,andFunk,D.C.(2018).Esport vs.sport:acomparisonofspectatormotives.SportMarket.Q.27,108–123. doi:10.32731/SMQ.272.062018.04

Proman,M.(2019). TheFutureofSportsTech:Here’sWhereInvestorsArePlacing TheirBets. Availableonlineat:https://techcrunch.com/2019/10/01/the-futureof-sports-tech-heres-where-investors-are-placing-their-bets/ Ratten,V.(2020).Coronavirusandinternationalbusiness:anentrepreneurial ecosystemperspective. ThunderbirdInt.Bus.Rev.65,629–634. doi:10.1002/tie.22161

Readwrite.(2018). TechIsFuelingGrowthintheSportsIndustry.Availableonline at:https://readwrite.com/2018/04/14/tech-is-fueling-growth-in-thesportsindustry/https:/www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=18a78c6e-4ee9444c-8889-a039583c54a7

Reitman,J.G.,Anderson-Coto,M.J.,Wu,M.,Lee,J.S.,andSteinkuehler, C.(2019).Esportsresearch:aliteraturereview. GamesCult.15,32–50. doi:10.1177/1555412019840892

Robehmed,N.(2013). WhatIsaStart-Up? Availableonlineat:https://www.forbes. com/sites/natalierobehmed/2013/12/16/what-is-astart-up/#5998d33a4044 Start-upHereToronto(2019).Six CompaniesSelectedforRyerson’sFutureof SportLab.Availableonlineat:https://start-upheretoronto.com/type/start-upnews/six-companies-selected-for-ryersons-future-of-sport-lab/ Stebbins,S.(2017). SportsTeamsRunningOutofFans.24/7WallSt. Availableonlineat:https://247wallst.com/special-report/2017/09/25/sportsteams-running-out-of-fans-ta/6/

Suneson,G.(2019). Theprosportteamsarerunningoutoffans.USAToday. Availableonlineat:https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2019/07/15/nflnba-nhl-mlb-sports-teams-running-out-of-fans/39667999/(accessedJuly10, 2019).

Vedder,R.,Denhart,C.,andRobe,J.(2013). WhyAreRecentCollegeGraduates Underemployed?PolicyPaperfortheCentreforCollegeAffordabilityand Productivity.Availableonlineat:https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED539373.pdf Willingham,A.J.(2018). Whatisesports?ALookatanExplosiveBillion-Dollar Industry.Availableonlineat:https://www.cnn.com/2018/08/27/us/esports-

Weeseetal. Preparing SportManagementGraduates

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 5 March 2022|Volume4|Article813504 11

what-is-video-game-professional-league-madden-trnd/index\penalty-\@M. html

Wilson,K.(2021). TheCOVID-19pandemicmightchangespectatorsportsforever asstadiumssitempty.TheConversation.Availableonlineat:https:// theconversation.com/the-covid-19-pandemic-may-change-spectatorsports-forever-as-stadiums-sit-empty-152740?utm_source=twitterandutm_ medium=bylinetwitterbutton

ConflictofInterest: GBwasemployedbycompanyCatapultCareerAdvantage. Theremainingauthorsdeclarethattheresearchwasconductedintheabsenceof anycommercialorfinancialrelationshipsthatcouldbeconstruedasapotential conflictofinterest.

Publisher’sNote: Allclaimsexpressedinthisarticlearesolelythoseoftheauthors anddonotnecessarilyrepresentthoseoftheiraffiliatedorganizations,orthoseof thepublisher,theeditorsandthereviewers.Anyproductthatmaybeevaluatedin thisarticle,orclaimthatmaybemadebyitsmanufacturer,isnotguaranteedor endorsedbythepublisher.

Copyright©2022Weese,El-Khoury,BrownandWeese.Thisisanopen-access articledistributedunderthetermsoftheCreativeCommonsAttributionLicense(CC BY).Theuse,distributionorreproductioninotherforumsispermitted,provided theoriginalauthor(s)andthecopyrightowner(s)arecreditedandthattheoriginal publicationinthisjournaliscited,inaccordancewithacceptedacademicpractice. Nouse,distributionorreproductionispermittedwhichdoesnotcomplywiththese terms.

Weeseetal. Preparing SportManagementGraduates

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 6 March 2022|Volume4|Article813504 12

Editedby: GayleMcPherson, UniversityoftheWestofScotland, UnitedKingdom

Reviewedby: ThomasFletcher, LeedsBeckettUniversity, UnitedKingdom CarltonBrick, UniversityoftheWestofScotland, UnitedKingdom

*Correspondence: AlbertoTesta alberto.testa@uwl.ac.uk

Specialtysection: Thisarticlewassubmittedto Sport,Leisure,Tourism,andEvents, asectionofthejournal FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving

Received: 03September2021

Accepted: 18February2022

Published: 29March2022

Citation:

TestaA(2022)WavesofExtremism: AnAppliedEthnographicAnalysisof theBosniaandHerzegovinaFootball Terraces. Front.SportsAct.Living4:770441. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.770441

WavesofExtremism:AnApplied EthnographicAnalysisoftheBosnia andHerzegovinaFootballTerraces

AlbertoTesta*

SchoolofHumanandSocialSciences,UniversityofWestLondon,London,UnitedKingdom

Thisarticleoffersanoverviewofafour-monthresearchproject,conductedin2019/2020, whichstudiedextremismintheBosniaandHerzegovina(BiH)footballterraces.Thiswork wasfundedbytheInternationalOrganisationforMigration-UnitedNationsandbythe UnitedStatesAgencyforInternationalDevelopment(USAID).Theresearchfocusedon riskfactorsandhowthesemaygovernthe“entry”ofBiHyouthintoextremehard-core footballfansgroups(Ultras1)andprolongtheirinvolvementinthem.Thestudyhighlighted thenatureofthesegroupsandtheiractivityprovidingdetailedrecommendationsfor BiHpolicymakers,securityagencies,andfootballfederationsandclubswhowishto understandandeffectivelyrespondtothisemergentthreatforpublicsecurityinBiH.

Keywords:extremism,far-right,Bosnia,Balkans,football,violence,Ultras,policing

INTRODUCTION:THEBOSNIAANDHERZEGOVINASOCIAL SPACE

Asaresultofthe1995DaytonAgreement,BosniaandHerzegovina(BiH)istodayacountry dividedbothgeographicallyandpoliticallyalongreligiousandethniclines,existingasatripartite state.Withinthepopulationof3.254million,48%identifyasBosniak(BosnianMuslims),37%as BosnianSerbs,themajorityofwhomareOrthodox,and14%asBosnianCroats,mostofwhom areCatholic(WorldPopulationReview,2020)2.Acrucialfactorinthepolitics,society,and internationalengagementofBiHistheimpactoftheethnicandreligiousconflictsofthe1990s. Thelegacyoftheseconflictscontinuestocontrolthenarrativesthatmeldreligion,heritage,culture, andethnicityintheevolutionofBosnianidentities,drivingdifferenceanddivision.Forexample, far-right“Chetnik”groups(namedafterSerbo-CroatunitswithintheformerYugoslavArmy) dependprimarilyontheRavnaGoramovement,centredmainlyinPrijedor’snorth-westerntown3 . TheNeo-Ustašegroups4 (theformerCroatianfascistmovement)areespeciallyactiveinareas alongtheBiHCroatianborderwhereethnictensionsflare-upbetweenthepredominantlyCroatian populationandtheBosniakMuslims.BosnianMuslimsalsohavenationalistorextremistgroups. Nascentfactionshaveappeared,includingtheBosnianMovementofNationalPride(BPNP). ThemovementpromotesBosniakidentityandsupportsasecularBosniakethno-nationaliststate;

1This articleusesthetermUltrasandnothooliganbecausethegroupsdefinethemselvesassuchastheymodeltheirrepertoire ofactionsaccordingtoUltrasgroupsinEurope.ThetermUltras–orultrà–originatesfromtheultra-royalistFrench(Testa andArmstrong,2010a,b).

22022Data,retrievedFebruary2022fromtheWorldPopulationReview:https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/ bosnia-and-herzegovina-population

3C.f.https://balkaninsight.com/2020/12/10/bosnia-charges-serb-chetniks-with-inciting-ethnic-hatred/

4C.f.https://balkaninsight.com/2017/05/05/far-right-balkan-groups-flourish-on-the-net-05-03-2017/

ORIGINALRESEARCH published:29 March2022 doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.770441 FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 1 March 2022|Volume4|Article770441

13

itactivelyshowsenmitytowardsgroupssuchasRoma, Communists,Jewishpeople,theLGBTcommunity,andthe so-called“non-whites”consideredalientotheirideologyand culturalheritage5 .

Againstthisbackground,hostilitiesarefrequentlyexpressed acrossBiHfootballterraces,withclashesamonggroupsofUltras. Forexample,widespreadfightsinvolvingover500fanstookplace in2009intheBosnianCroat-dominatedtownofŠirokiBrijeg betweenlocalsandtheUltrasfromFKZeljeznicar6 resulting inonedeath,overfiftyinjured,andwidespreadvandalism7.In 2015,theŠirokiBrijegyouthfootballteambuswasambushed inSarajevo,onceagaininvolvingUltrasconnectedtoFK Zeljeznicar8.Inothertownswithdiversepopulationssuchas Mostar,sectariandividesalsopermeatefootballclubs’rivalries; forinstance,FKVeležMostar(associatedwithBosniaks)and HŠKZrinjskiMostar(linkedtoBosnianCroats).Becauseof suchviolentepisodes,theBosnianFootballUnionhasregularly orderedfootballmatchestobeplayedbehindcloseddoors. Overthepastdecade,therehavebeenrepeatedrumoursthat thenationalfootballleague–currentlyconsistingofBosniak, BosnianSerb,andBosnianCroatteams–couldbedissolved. Onoccasions,BosnianSerbofficialshavesuggestedwithdrawing BosnianSerbfootballteamsfromtheleaguealtogether;the NKŠirokiBrijegfootballclubmanagementhasseveraltimes threatenedtojoinCroatia’snationalfootballleagueinstead9.Such violencehighlightsthefragilityoftolerancebetweenthecountry’s threeethnicgroupsandhoweasilyintolerancecanescalateinto violence,oftenstokedbyfar-rightandnationalistgroups.

Moststudiesonthelinkbetweenextremismandviolent ideologicallyUltrasgroupsrelyon“external”observationsofthe groups’behavioursandmostlyonsecondarycollecteddatafrom theInternet via socialmedia10.Thisapproachisunderstandable assecurityrisksareinvolvedininteractingwiththesegroups, andthesegroupsarechallengingtoapproach11.Thissituation isevenmoredifficultconsideringthepeculiarityoftheBiH socialspace,asmentionedearlier,plaguedbyhistoricalconflicts amongdifferentethnicgroupsandpoliticalrivalriesamongthe sameethnicgroups.Fewstudieshavefocusedonthistopic; amongthemostnotable, Milojevi´ c etal.(2013) mainlylink the occurrencesofviolenceamongUltrastotheconsequencesofthe BiHwar;however,itisdated.TheexcellentresearchofItalian

5C.f.https://balkaninsight.com/2021/06/02/bosnian-far-right-movement-wedsbosniak-nationalism-neo-nazism/

6Themaingroupisknownasthe“Maniacs”orManijaci,theyarelinkedto BosniaksandarebasedinSarajevo.

7RetrievedNovember2020fromhttps://balkaninsight.com/2017/05/05/far-rightbalkan-groups-flourish-on-the-net-05-03-2017/andhttps://www.iss.europa.eu/ sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Brief%2020%20Balkan%20foreign%20fighters.pdf

8RetrievedSeptember2020fromhttp://www.css.ethz.ch/en/services/digitallibrary/articles/article.html/108850/pdf;https://balkaninsight.com/2015/03/16/ hooligan-attack-raises-ethnic-tensions-in-bosnia/

9RetrievedNovember2020fromhttps://balkaninsight.com/2015/03/16/hooliganattack-raises-ethnic-tensions-in-bosnia/ 10Thisalsoholdstrueformainstreamextremism,especiallyjihadistandfar-right groups.

11Fielding(1981) inhisseminalstudyontheBritishNationalFront,detailsthe challengesforaresearcherinstudyingextremistgroupsobjectively;whileTesta (2010a,2010b), Testa,2018,2020)pointsouttheriskinherentininteractingwith them.

sociologist Sterchele(2013) providesanethnographicaccountof BiH footballpractitioners,includingBiHfootballsupporters,but notfocusingspecificallyonthegroupsanalysedbythisarticle.

Thisarticleaimstofillthisgapintheliterature;thearticle originatesfromaresearchprojectaimedtounderstandthe potentiallinkagebetweenUltrasinBiHandviolentextremism. Thisarticlewillfocusonlyonfindingsaimingtounderstand theBiHUltrasgroups’maintraits,exploringiftheycanbe consideredextremefootballfansor,moresimply,criminalgangs interestedinfootball.Thisarticlewillalsoexplainwhojoins thesegroups,thegroups’structure,theirappealtotheBiHyouth, andhowthegroupsusesocialmediatomanifesttheircollective identityand,ifany,ideologies.

METHODS

Thisstudyemployedan“appliedethnographic”approach12 Appliedethnographyhastwomainelements;thefirstoneis explanatory,therefore,relevantforpolicymakers,practitioners, andinstitutions,andanyoneseekingtoaddresscomplexsocial issues.Thesecondelementistheapplicationtoreal-world problems;itprovidesaspecific,in-depthunderstandingofhow individuals’socialworldunfoldsdaily(BrimandSpain,1974; Pelto,2013;Cf. Fetterman,2020).

Togatherdata,theresearchteamusedtriangulation.Asthe termsuggests,thisapproachemploysmorethanonemethod tocollectinformation(HobbsandMay,1994;Denzin,1996; Silverman,2013; JerolmackandKhan,2017).Ourresearch approachinvolvedaccessingrelevantgroups via anetworkof crucial“gatekeepers”(i.e.,individualslinkeddirectlytowho areactiveinthestudiedcommunities/groups).Basedonthis negotiatedaccess,theresearchteamgathereddata via fieldwork fromvarioussources,includingdirectinterviews,observations, andtheinternet.Moreover,researchersgathereddataonthe culture,values,andideologyoftheparticipantsandgroups,and theirinteractionswitheachother.

TheresearchteamfocusedonthemostactiveUltrasgroups toviolence,allegedcriminalactivity,andthegroups’proselytism inandoutsidetheBiHfootballstadium;thechosengroups neededtorepresentthethreemainBiHethnicgroups. Via acombinationofgatekeepers’introductionandsnowballing sampling,weselectedthefollowinggroups:TheHŠKZrinjski Mostar(HrvatskišportskiklubZrinjskiMostar),theŠkripariNKŠirokiBrijeg,theUltras-HŠKZrinjskiMostar,theLešinariFKBoracBanjaLuka,andtheRobijaši-NK ˇ CelikZenica.

Inrelationtothestakeholders,theresearchteaminterviewed thefollowinginstitutionalstakeholders:

• TheMinistryofSecurityofBiH;

12Therearedifferencesbetweenacademicethnographyandappliedethnography. Whilethetheoreticalrootsarethesame,themaindifferenceisinhowtheresearch isshaped.Inacademicethnography,thechosentopic/problemdictatesthedesign, budget,and,mostimportantly,thetimeframe;specifically,fieldworkrequiressix totwoyearsormore.Acontractfundstheappliedethnographicwork,anditisa fullydevelopedresponsetothefunders’expressedinterestintheproblem(Brim and Spain,1974;Pelto,2013;Cf. Fetterman,2020).Thetimeframeofthefieldwork depends onthefunders’needs,andthefindingsareusedtotackletheproblem.

Testa Wavesof ExtremisminBosniaTerraces

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 2 March 2022|Volume4|Article770441 14

• TheMinistryofInternalAffairsoftheSarajevoCanton;

• The SarajevoCantonpolice;

• TheRepublicofSrpskaMinistryoftheInterior;

• ThePoliceAdministrationBanjaLuka;

• TheFootballAssociationofBiH(Nogometni/FudbalskiSavez BosneiHercegovine);

• TheFootballAssociationofRepublikaSrpska (Fudbalskisavez RepublikeSrpske);

• TheFootballClubŠirokiBrijeg(Nogometniklub ŠirokiBrijeg);

• TheFootballClubŽeljezniˇcar(Fudbalskiklub ŽeljezniˇcarSarajevo);

• TheFKVeležMostar(FudbalskiklubVeležMostar).

Theteamthenproceededwithsemi-structuredinterviews. Informedconsentwasgivenpriortotheinterviews;the interviewswererecordedwithadigitalrecordingdevice,then translatedandtranscribedbytheInternationalOrganization forMigration(IOM)ispartoftheUnitedNationsSystem administrationstaff.Theobservationswerecarriedoutinthe locationsofthecitieslinkedtothegroups;thoselocations wereoftensignpostedbygraffitithatwerealsophotographed andtranslated.Observationswerealsomadeduringmatches andeventssuchastheBiHgaypride,whereweknewgroups wouldhaveintervenedtoprotest.Tocomplementthiswork, theresearchteamgatheredandtranslatedmediaarticles,policy documents,andBiHlawsdealingwithhatecrimesandviolence atBiHfootballmatches;theresearchteamalsocollectedpolicies anddirectivesofBiHfootballclubsandfootballassociations.The institutionalstakeholderswereinstrumentalinthecollectionof thesedocuments.Finally,theonlinedatagatheringaboutgroups, networks,andnarrativeswascarriedoutbytheInstitutefor StrategicDialogue(ISD);itcomplementedtheofflineresearch bydeterminingthelevelofonlineactivityoftheUltrasgroups studied,andifthesegroupshadlinkstoethno-nationalistviolent extremism(c.f. Testa,2020).Theinvestigationassessedthescale andextentoftheironlineactivity,thesocialmediathesegroups used,howtheyusedthem,andforwhatpurposesandthetypes ofcontentandnarrativespromotedbythegroups.

Analysis

Theresearchteamusedgroundedtheorytomakesenseofthe data(GlaserandStrauss,1967;Charmaz,2014).Theanalysis started byreadingandcoding13 theinterviewstranscripts, onlinedata,policies,andlaws.Theteamalsocodedpictures ofgroupsinactionandmuralgraffiti.Thecodeswereatthis stageprovisionaltoallowflexibilitytonewinterpretationsin linewiththedevelopmentoftheanalyticalprocess.Theprocess alsoinvolvedcomparing,modifying,andmergingcodes.Once theresearchteamendedthisinitialstep;theanalysisbecame moreintensive,aimingtodevelopmoresignificantclassifications includingtheoreticalconcepts;thisprocesswasintegratedby memowriting.Thisprocesslasteduntilsaturationwasreached

13AlldatawerecodedandanalysedusingMAXQDAsoftware,whichfacilitatesand supportsqualitative,quantitativeandmixedmethodsresearchprojects(Woolfand Silver,

(StraussandCorbin,1998).Theprojectadheredtotheethics code of theAmericanSocietyofCriminology.Theonline researchteamalsofollowedTheInstituteforStrategicDialogue (ISD’s)in-houseEthicsPrinciplesforonlineresearch.Alldata obtainedfortheprojectwasstoredsecurelyfollowingtheEU GeneralDataProtectionRegulation(GDPR).

FRAMINGTHEBiHULTRAS

ExplainingtheUltrasinBiHisacomplextask.TheBiH authoritiesarestrugglingtocountertheUltras’illegalactivityand controltheirviolenceinsideandoutsidethefootballterraces.The dangerposedbythesegroupsisexemplifiedbyaviolentincident thatoccurredinSeptember2019.RadioSarajevocameunder attackfromagroupofUltrasassociatedwiththeFootballClub Sarajevo14,terrorisingseveraljournalists.Indeed,sinceearly 2019,BiHjournalistsandthe“FreeMediaHelpLine”recorded fivedeaththreatsandsixactualphysicalassaultsonreportersand mediateams.ThejournalistsdenouncedtheinabilityoftheBiH authoritiestopreventsuchepisodesandtopunishthem15

Thegroupstructureiscentralisedbutincludesmorethan aleader;membersalsohavesomeauthority.So,powerisin multiplehands,andthereisahighleveloffunctionaldiversity. Inonegroup,thereweretenleaders.TheUltrashada“nucleus” ofindividualsrangingfrom50to70,whilethegroupmembers’ numberwasfrom100to500maximum.Theageofthe membersrangedfrom17toafewover40’syearsold.The demographicseemstorepresentthelocalcommunity’s(“the people”)socialstratification.TheUltrasZrinjski-FCZrinjski Mostarprovidedmoredetailsaboutthedemographicofatypical BiHUltrasgroup:

ResearchTeam: Whoarethemembersinthegroup,students orworkers?

Ultras: Therearehigh-schoolkids,universitystudents,those whogotemployedstraightafterschool,orunemployedpeopleyouknowhowthesituationishere [highunemploymentrates].

Theleaderswerethosewhowereolderandwereperceived ascharismaticfigures.Thisisimportanttomakesenseofthe radicalisationprocessofnewcomers’,astheypromotechanges inbeliefsandbehavioursandfacilitatetheinternalisationofthe Ultrasmentality.TheUltrasLešinari-FCBoracBanjaLuka describedthenatureofthemembers’commitmenttothegroup:

Researchteam: Howmuchtimedoyouinvestinthegroup?

Ultras: Usuallyonweekends,whenthefootballclubisinaction. Wegathermaybeeverysecondweekend.However,everyonealso leadsitsownlife...

Researchteam: Doyougotoeverymatch?

14Interms ofcriminalactivities,theManiacs(ManijacisupportersoftheFootball ClubŽeljezniˇcar)andHordeZla(supportersoftheFCSarajevo)aredeemedby allpoliceforcesinterviewedasthemostdangerous;theyareclassifiedascriminal organisations.ItisimportanttostressthatbothUltrasgroupsweretheonlyones whorefusedatthelastmomenttomeettheresearchteambecauseofourquestions focusingoncriminalactivities.

15RetrievedSeptember2020from https://balkaninsight.com/2019/09/30/bosniajournalists-protest-after-thugs-storm-news-outlet

Testa Wavesof ExtremisminBosniaTerraces

2018).

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 3 March 2022|Volume4|Article770441 15

Ultras: Everylocalmatch,awaymatcheswhenIhavetime.

Tobe partoftheUltras“nucleus”(seniormembers’circle),it isindispensabletoshowcommitmentandelitismtoadhereto thegroup’svalues,ideology,andtradition;only,inthiscase,a memberisco-opted.Thenucleusdealswithalltheactivities oftheUltrasgroupfrommemberships,muralgraffiti,banners, chanting,smugglingpyrotechnics,andorganisingcrimessuchas sellingdrugs.

RISKFACTORS

Arangeofriskfactorsexplainstheexistenceandappealofthe UltrasgroupstotheyouthofBiH.Ouranalysisindicatesthat thefirstbroadriskfactorissocio-environmental;therefore,it needstoconsidermanyissues.Ethnicityandethnictensions doappeartoplayapart,butwesuggestthisisnotaprime issueinunderstandingtheUltrasgroupsinBiH.TheUltras groupsexploitethnicitytojustifytheirexistence;thegroupsserve asacatalystofbelonginginapoliticallyfragmentedcountry. EthnicrootsarealsousedbytheUltrasasanarrativetosingle outandmostoftenlegitimiseprovocationtorivalfactionsand, ultimately,violence.Ourresearchindicatesthattheeconomic andpoliticalsituationofBiHandunemploymentrateand concomitantunderutilisationofyouthwerevitalriskfactors singledoutbyallstakeholders,includingtheUltrasgroups. DisenfranchisedyouthjointheUltrasbecausetheyallowthem togainpower,tackleboredom,dischargeeverydayfrustrations, andbecauseoftheirproductivecriminalactivities.Ourresearch alsosuggeststhataddingtotheproblemsofthepoliticaland economicsituationarecausalfactorsthatrelatetothelackofan effectivefederallegalstructureandthefactthattheresponsesof theBiHpoliceandfootballauthoritiesseemtofallwellbelow internationalstandards;thelatterpointwasconfirmedironically byseveralUltrasgroups.

DataalsoindicatetheBiHfootballstadiumsasakeyrisk factor,particularlythepoorstadiumfacilities,lackofstadium regulation,andinefficientsecurity.AsinotherEastEuropean countries,lowattendancesatfootballmatchesworkasan amplifierofUltras’actionsandpresence(Dzhekovaetal.,2015 in Testa,2020,p.28).Ultrasarethusperceivedbyyoungstersand other fansaspowerful:thetrueownersofthefootballstadium. Theirchants,banners,symbols,andphysicalintimidationare usedtorecruit(fansjointhembecausetheyareintimidatedor fascinatedbythem)orexcludethosewhoopposetheirpresence andpower.ThisimbalanceofpowerbetweenUltrasandthe “others”withinthestadiumsmustbeaddressed.Thecontrolof thefootballterracesissostrongthattheUltrasdeterminewho hasaccesstothem.TheCatholicUltrasŠkripari-NKŠiroki BrijegvettedMuslimswhoexhibitsymbolsoftheirreligious identity;accordingtothegroup,nowomenwiththeniqabcould accessit.

TheŠkripari-NKŠirokiBrijegexplained:

Ihaveaproblemwithit [niqab] butforanotherreason.Myissue withitisthatisnotpartoftheBosnianMuslimtradition,itis imposedbyaforeignculture-theArabs.AvastmajorityofMuslims

herearemoderate,EuropeankindofMuslims.Iknowforafactthat itbothersBosniaksevenmorethanSerbsorCroats.Ididalotof researchintothisbecauseIaminterestedinit,andIsawthatthis wasnotsomethingthatwaseverpartofBiH.Thiswasimposedon them [BiHMuslims].

Inaddition,thelackoffootballclubs’securityandregulations insidethestadiummeanstheUltrasgroupscanexerciseavery highlevelofcontrolinthefootballstadiums.

Thesecondbroadriskfactorispoliticalandcanbeidentified intheUltras’narrativeofaperceivedcorruptpoliticalclass thatfailstheBiHyouthandsociety.Aroundthisnarrative,the groupsorganiseandrecruit.Inthiscase,theUltrascharacterise themselvesasthesole“resistance”tothefederalandlocalstatus quo.TheBiHUltrascanbeidentifiedasresistancegroups fromthedatagathered.AllUltrasgroupsaccomplishedthree mainfunctions;theywereavehicleofanti-systemssentiments, theyfunctionasameansofidentityshaping,socialsolidarity maintenance,offeringmembersandpotentialrecruitswith framestomakesenseoftheirlives,frustrations,andgrievances; providingrecruitsandmemberstheillusionofself-efficacyto theirgrievances.(Cf. AdamsandRoscigno,2005;p.71; Diani, 1992). OneoftheleadersoftheŠkripari-FCŠirokiBrijeg explainedtheirresistanceagainstthesystemandtheirstruggle withthelocalauthorities:

Wearevisibleandspreadingourmessages,butwedoitfromour standsbecausewecannotchangeanything [outside]. So,ifwehave abannerthatsomebodydoesnotlike,ourpolicegiveustroubles aboutit.WedonotgetpunishedinSarajevooranywhereelse.This doesnothappenanywhereelse [inBiH].

AlltheUltrasgroupsinterviewedmanifestedtheiroppositionsto localpoliticalpartieswho-accordingtothem-havehijackedany societalarena,includingpolicing;sometimes,thegroupsacted aspolitical/pressureforcetocontrastlocalpoliticsastheearlier quotationoftheŠkripari-FCŠirokiBrijegdetails.

Far-rightideologywaspartoftwogroups’collectiveidentity16 butitdidnotappeartobeassophisticatedandstrongasother EuropeanUltras,forinstance,astheUltrasinItaly,Spain, Greece,andsomeEasternEuropeangroupssuchasthePolish andBulgarians.Significantriskfactorsarealsothesenseof belonging/communityandidentity.Forexample,beingfrom GrbavicainSarajevoenshrinesanidentityupontheeveryday teenagerofbeingaManijac17.Localnetworks(family,friend groups,classmates)alsoamplifythechancestojoinanUltras group.Ourdataalsostressriskfactorssuchasthefeelingof victimhoodagainstjournalists,thefederalstate,localpoliticians, thepolice,theloveforthecityandthefootballclub,andthe excitementofviolenceandglory.

TheUltrasMentality

Throughoutthestudy,alltheUltrasinterviewedreferredtotheir waysoflifeasthe“Ultrasmentality”.TheconceptofUltras mentalitycanbeunderstoodusingPierreBourdieu’sconceptof

16Škripari-NKŠirokiBrijegandUltras-HŠKZrinjskiMostar.

17

Testa Wavesof ExtremisminBosniaTerraces

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 4 March 2022|Volume4|Article770441 16

UltrassupportingtheFootballClubŽeljezniˇcar(Sarajevo).

Habitus:“asubjectivebutnotindividualsystemofinternalised structures,schemesofperception,conception,andactioncommon toallmembersofthesamegrouporclass” (Bourdieu,1977;p.86). TheUltrasmentalityservestounderstandthemembers’group lifeperceptionsandchallengesandultimatelytheirpractises, includingviolence.Theseinternalisedstructuresandschemesof perceptionshapethesubject’s(andgroups)sharedworldview andtheirawarenessofthesocialspaceinwhichthegroupsare located(Bourdieu,1977,p.86, 1998; BourdieuandWacquant, 2007). TheUltrasmentalityisacquiredasBourdieu’sHabitus bythepractiseofbeinga“true”Ultras,byapermutationof influencessuchasvicinityordistancefromotheractors(group members;rivalsandthepolice)and‘mimeticism(Lizardo, 2009). Via mimeticism,intangibleprinciples-suchasvaluesanddispositionsaretransmitted,andtheseareemployedwhen similarsituationsandpractisesreoccur. Lizardo(2009) clarifies howmimeticism works;itintentionallystartsfocusingonvisually accessiblerolemodels–inthecaseoftheUltras,theUltras leaders-then,thisprocessofmotor-schematicmirroringcomes togainahabitualandimplicitcast.Thismentalityshaping processoccurswithinthegroupinthefootballterracesbut alsoduringthemeetingsoutsidethestadium.AsBoudieu’s Habitus,theUltrasmentalityhasacollectivedimensionsincethe members’categoriesofjudgmentandactionthatarisefromthe grouparesharedbyallthosesubjecttothesamesocialconditions andconstraints.Ultraswhoinhabitthesamesocialspacedevelop acomparablementalityandacomprehension-ledmechanism influencedbythismentalphiltre(SimonsandBurt,2011)sharing hopes, choices,andfrustrations.

Basedonthisstudydata,theBiHUltrasmentality isshapedaroundfouressentialelements,namelygroups’ values,anti-systemattitude,pastandtradition,andethnic nationalism.Thefundamentalvaluesofthe“true”BiHUltrasare loyalty,honour,strength,group’sunity,andthecelebrationof “Balkan”masculinity,essentiallyrepresentedbybackwardness, parochialism,traditionalism(Dumanˇci´candKrolo,2016),andin theUltrascase,aggressivenessandultimatelyviolence.

ContactsportsarepartofthismentalityastheUltrasRobijaši -FC ˇ

CelikZenicapointedout:

Researchteam: Doyouliketofight?

Ultras: Yes,yes.

Researchteam: Doyoutrain?

Ultras: Iplayrugby....itisthepartofbeingUltras [tobetough].

Igototheuniversityduringtheweek,andtheweekendisforthe footballgames.Andyouknowwhathappensduringthegames...

Youmustbeprepared [tofight] ....Thatisalsothereasonwhy wegotothefootballgames [tofight].

ThepreviousquoteencapsulatestheessenceofbeingaBiH Ultras,reflectingamanshowingstrength via rugby.AnUltras Škripari,whowasinterviewed,wasproudofbeingakickboxing expert;hiscombatskillswereusedbythegrouptochallengetheir opponents;heconfirmedbeingalwaysinthefrontrowiffights againstthepoliceandrivalgroupsarose.

Thedailyfrustrationsagainstthefederalandlocalpolitics areexternalisedbythegroups via theiranti-systemattitude.

Theirresistance(anddisgust)totheperceivedcorruptfederal stateandpoliticalclassareacommonelementthatunitesthe groupsinterviewed.Thisrageborderlinehopelessstanceisalso presentwhentheBiHfootballestablishmentsituationisanalysed. TheFootballAssociationofBiHwasconsidereddecadentand costly,spendingmoneyon“fancy”buildingsinSarajevobut notinvestingfundsinstadiums’facilitiesandinpromotingBiH youthtalentinfootball.

ThepolicewerealsooftenthetargetofalltheUltrasgroups’ anti-systemnarratives:

UltrasŠkripari-FCŠirokiBrijeg:They [CroatianDemocratic UnionofBiH-HDZ-andthepolice]arealllinked,whileweare completelyunrelatedtoHDZ.Itistheproofthatoncewestart diggingintosomethingthatshouldnotbelookedinto(fromthe politicalpointofview)orriseupagainstthepolice,orsomeclub’s decisions,immediatelywegetsomefines.So,inthesesituationsthe city,thefootballclubandthepoliceallgettogethertoworkagainst us.Forexample,wemakesomestupid,smallthingatthestadium, andimmediatelytomorrow20groupmemberswillbetakentothe policestationandquestioned.Sothatiswhyitisimpossibletomake anychange.

Asthequotationunderlines,thepoliceinMostarandthecity ofŠirokiBrijegwereseenasbeingusedasapoliticaltool;asa meanstopunishthosewhoopposethelocalpoliticalparty(the HDZ)deemedascorrupt.

PastandTradition

Asmentionedearlier,anevaluationoftheBiHUltras phenomenonconcentratingsolelyonethnicnationalismdoes notcaptureinitsentiretyextremismintheBiHfootballterraces. TheUltrasRobijaši-NK ˇ CelikZenicaexplained:“Wecannot speakaboutethnicity,becausewehavememberswhoareBosniaks, Serbs,Croatsandthatiswhywearespecific.....Thereisno placefornationalisminourgroup”. AccordingtotheUltras Robijaši-NK ˇ CelikZenica,theUltrasfromBanjaLukaor MostarareseenthesamewayasthosegroupsfromSarajevo. Aggrocanoriginatefrompastrivalries.AsinmanyEuropean Ultrasgroups,friendshipsandanimositiesdevelopsimilarly; forexample,friendshipswithothergroupstendtobebased onrespect.Allgroups,whohavethesamementality,benefit fromthissharedsystemofvalues.ThepremiseoftheBedouin Syndromeostensiblycontrolstheestablishmentofrivalriesand allies:friendsofanallybecomefriends,enemiesofanallybecome enemies(Bruno,in DeBiasiandMarchi,1998).

Historicrivalriesbetweenfootballclubsarelinkedto theUltrasmentalityanditspropensitytowardsforminga “sacralspace18.”Thefootballterraces–asthedistrictsand neighbourhoodswheretheUltrasbelong–aredeemedsacred; theyareaphysicalandsymboliclocation,whichisautonomous fromthestadiumandthecity.Theirviolation(sacrilege)by opponentspromotesviolenceandcallfor“sacrifices”.Rather revealing,in2016,wasthe“calltoarms”oftheManijacigroup oftheSarajevoteamFKŽeljezniˇcartotheirrivalstheHorde 18

Testa Wavesof ExtremisminBosniaTerraces

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 5 March 2022|Volume4|Article770441 17

C.f. http://rj-vko.kz/en/speczproektyi/sakralnaya-geografiya.html

Zla(EvilHorde)toattackanddestroytheFukare19 whentheir footballteamwouldhaveplayedinSarajevo.AllthreeUltras groupsweremainlyBosniaks,soethnicitywasnotthereason forthisepisode.Althoughthisepisodeshowsthelinkbetween violenceandfootballinBiH,itisessentialtopointoutthat footballfans’violencecannotbecomparedinseverityand significancetootherEuropeancountriessuchasPoland,Russia, Italy,andtheUK.

EthnicNationalism

Asmentionedearlier,ethnicnationalismisnotenoughaloneto justifytheBiHUltras’existence.AstheUltrasLešinari-FCBorac BanjaLukaargued:

Researchteam: IsSerb-nationalismimportantinyourgroup?

UltrasA:Idonotgiveaf∗∗∗ aboutthat.MybestmanisCroat, mywifeisMuslim,mygrandmotherisMuslim.

Researchteam: Butwhatabouttheyoungergeneration?

UltrasA: Theyarethesame.Weloveourcityandtheclub.

UltrasB: Wearethesame.TherearenotonlySerbson thestands.

Itisabouttheloveforthe [football] club.

Ethnicityisusedarbitrarilyandcontradictorilybythegroups. Insomegroups,ethnicnationalismwasassociatedwithfarrightandfar-leftideologies.Ethnicityissymbolicallyexploited asatooltodistinguishthemselvesfromothers(DeVosetal., 2006) justifyingattimesthegroups’existence.AnUltrasZrinjskiHŠKZrinjski Mostarmemberunderlinedtheuseofwhatthey identifiedas“Bosniaknationalism”,whichwaspartoftheUltras ManijaciandHordeZlaSarajevonarratives:

Forexample,groupsfromSarajevoareright-orientedbuttheyare notfascist,morelikeBosniaknationalists.ButVeležsupporters areofficiallycommunists;so,theyhaveaconflictofinterest.They cannotputaredstarontheirflagbutalsowanttobeBosniak. Their“leader”-TitodidnotwantBosniaks,SerbsorCroatsbuthe wantedYugoslavs,andthatistheirinternalconflict.Beforethewar, theywereperceivedasaYugoslavclub.

Whileethnicnationalismdoesnotentirelyjustifythegroups’ existence,thegroups’criminalactivitiesdoso.Tomakesenseof theBiHexistence,focusingonlocalisedpowerdynamicsandthe Ultrasgroups’criminogenicneedsiscrucial.

CriminalActivities

OuranalysissuggeststhattheUltrasphenomenoninBiHis notsomuchanissuerelatedtopoliticsorreligion(cf.ethnic nationalismandfar-rightorjihadistideologies)butmoreabout thegroups’criminogenicnature,status,andneedswithinthe political,social,andeconomicgeographyoftheirlocalsettingtheircities.ThedataindicatesthatinBiH,Ultrasgroupsexistto makemoneyfromcriminalactivities20,mainly via drugdealing, racketeering,extortions,intimidations,and“services”offered tolocalpoliticiansduringtheelectoralperiod.Ourdataalso

19Theyarecalledthe“Wretches”andtheyaretheUltrasofthefootballteam SlobodafromthecityofTuzla.

20ThiswasconfirmedbytheBiHauthorities.

highlightthatinspecificlocales,authorities’corruptionlevels allowthelocalUltrasgroupstogainandexercisetheirpowerand control.Crimeandcorruptionweresointrinsicallylinkedtothe UltrasinBiHthatoneUltrasgroupregrettedthatitwasrelatively smallinnumberbecausethiswashinderingtheircriminal opportunitiesandprofits.Akeydriverforgroups’recruitmentis theircapacitytooperateasasemi-organisedcrimegroupwithin andsometimesbeyondtheirlocality.Ourfindingsalsosuggest thatthosewithinUltrasgroups’organisedcriminalitymaybe legitimisedthroughtheconnexionsbetweentheUltrasleaders andthefootballclubs.OurdatasuggestthatmostoftheUltras groupsreceivefinancialpaymentfromthefootballclubstoavoid creatingproblemsfortheirclubs21 .

Whilethepoliticalandideologicaldimensionsappearnotas significantwhencomparedtotheircounterpartsinEuropeand theBalkans22,wealsofoundthathomophobiahatecrimesare insteadtheelementthatlinksalltheBiHUltrasgroupsregardless ofreligionandethnicity,andtheyareanintegralpartofthe Ultras“DNA”.ArepresentativeoftheFootballAssociationofBiH elaboratedonanepisodeinvolvinghomophobiawhichwould havebeenrigorouslydealtwithifithadtakenplaceinother footballstadiumsinEurope:

Homophobiaispresentoccasionally;duringtherecentmatchofFC Željezniˇcar,Manijaciusedabannerwhichsaid“ImaZabraniti” (whichwouldmean“thereissomethingtoforbid”)asareaction totheannouncementthatthefirstgayprideeverwillbeheldin September2019inSarajevo.Theofficialmottooftheprideis“Ima iza´ci”whichmeans“gettingoutofthecloset”andalsogettingout tosupportthepride;additionally,duringthesamematch,theflag ofBruneiwasdisplayedashomosexualismthereisillegal[punished withthedeathpenalty].

Antisemitismsharesthesamedynamicoccurringfor homophobichatecrimes;itunites, via prejudiceand hateallUltrasgroupsregardlessofreligion,ethnicity,and historicrivalries.

TheInternet

FootballandsocialmediaarecloselylinkedinBiH.For instance,theBosnianinternationalfootballerEdinDzekowas themostfollowedpageinthecountryonbothFacebook andTwitter,withover2millionand1.5millionfollowers23 Duringthisstudy,thepublicactivityofseveralUltrasgroups wasmonitored.Forthepurposeofthisanalysispublicactivity isunderstoodtobecontentproducedbyparticularaccounts orUltrasgroupsonsocialmediawhichisreadilyavailable toresearcherssearchingacrossaplatform,orthroughthat platform’sapplicationprogramminginterface(API),andwhich doesnotrequirespecialpermissiontoaccess(e.g.,througha requesttoaclosedgrouporchatchannel).Hence,theresearch teamfocusedonengagementdatawithpublicFacebookpages

21This wasconfirmedbytheBiHauthorities.

22TheMinistryofSecurityofBiH,SarajevoCantonpolice,RepublicofSrpska MinistryoftheInteriorandPoliceAdministrationBanjaLukaconfirmedourdata thatracismwasnotanissue.

23DatagatheredbytheInstituteforStrategicDialogueforthisresearch(2020).

Testa Wavesof ExtremisminBosniaTerraces

FrontiersinSportsandActiveLiving|www.frontiersin.org 6 March 2022|Volume4|Article770441 18

associatedwithUltrasgroupsinBiHfromJanuary2013to November2019. Thisinvestigationrevealedover4.7million userinteractionswithpostsinthesegroups;1.5million(nonunique)userslikingthesepagesandan11%growthoverthe 12-monthperiod.