THE LODGE

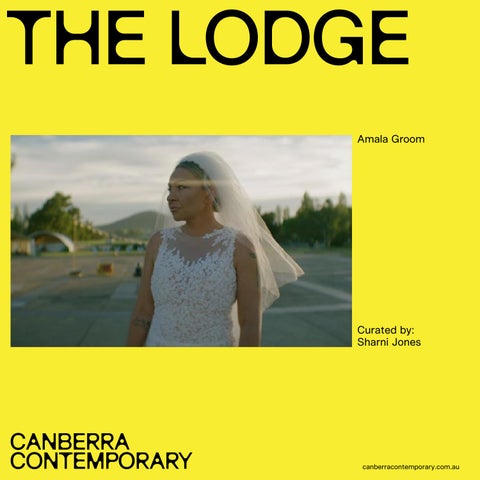

Amala Groom

Curated by: Sharni Jones

Cover Amala Groom

The Lodge 2025 (production still)

Single-channel video, 6K UHD video, colour, sound, 11:11 mins

Image credit: Ryan Andrew Lee

artist statement

Autobiographical in nature, The Lodge is a ceremonial moving image work that serves as both a spiritual invocation and a metaphysical act of resistance. Set within the landscape of Canberra’s Parliamentary Triangle—an epicentre of colonial governance imposed upon Ngunnawal Country—The Lodge activates this contested site through performance, ritual, and geometry. While the area is often read as the heart of the Australian state, Groom reclaims it as a sacred ceremonial ground, long used for corroboree and intertribal gathering.

The visual and conceptual foundations of The Lodge are built on sacred geometry. Groom integrates esoteric forms including the triangle, circle, vesica piscis, rhombus, square, hexagram, hexagon, polygon, cross, and octagon—shapes that carry ancient cosmological and spiritual significance. These forms are more than symbolic; they serve as energetic templates for transformation, encoded with principles of duality, unity, balance, and divine proportion.

Groom’s physical journey through the Parliamentary Triangle is mapped according to these sacred geometries. The work draws particular focus to the vesica piscis—two overlapping circles forming an almond-shaped portal—symbolising the meeting of dual worlds and the birth of new consciousness. Groom’s body becomes the centre point, the moving axis between spirit and matter.

The project engages deeply with the geomantic and Theosophical design principles of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, who envisioned Canberra as a spiritual city constructed according to cosmic harmonics and the energetic potential of sacred geometry. Heavily influenced by Theosophy, particularly the teachings of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the Griffins designed the capital as a metaphysical experiment—an ideal city intended to channel universal energies for collective elevation. Groom repositions these esoteric foundations through a First Nations lens, critiquing their appropriation while acknowledging their embedded spiritual potential. In The Lodge, she re-indigenises the grid, aligning these patterns not with imperial intent but with ancient songlines and the spiritual lore of Country.

Through embodied performance, Groom engages with the metaphysical war between imposed colonial order and the spiritual sovereignty of First Nations peoples. The

work references David Lynch’s mythologies from Twin Peaks, where the White Lodge and Black Lodge represent dual realms of spiritual polarity. Groom situates these metaphysical constructs within the Australian settlercolonial context, asserting that the Parliamentary Triangle itself operates as a kind of Black Lodge—a vortex of state violence built atop sacred land. Her journey—marked by the red rope that binds and connects—becomes a sovereign act of geometric resistance.

The Lodge ultimately functions as a living mandala: a visual, spiritual, and spatial invocation that disrupts linear time and asserts an Indigenous cosmology of cyclical presence. It is both an elegy and an awakening, a reclamation of the sacred forms beneath the bureaucratic grid. Groom’s work invites audiences into a ceremony of deep seeing—one in which the true architecture of Country is not only revealed, but felt. Through her use of sacred geometry, geomancy, and Theosophy, Groom opens a pathway between worlds, offering a vision of balance, sovereignty, and enduring spirituality.

Amala Groom is a Wiradyuri conceptual artist whose practice integrates traditional cultural knowledge with contemporary art. Grounded in Wiradyuri ontology, she explores the balance between physical and spiritual realms through Yindyamarra, Kanyini, and Dadirri —principles of respect, interconnectedness, and deep listening. Based in Kelso, NSW, her work asserts cultural sovereignty, critiques colonial legacies, and amplifies Wiradyuri histories.

THE LODGE: THE POLITICAL IS THE PERSONAL

In 2016, I nominated Wiradyuri artist Amala Groom to serve on the board of the National Association for the Visual Arts (NAVA), making her the first Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person to hold such a position within the organisation. At the time, I was well aware of Groom’s extensive background in First Nations activism and cultural advocacy, as well as her commitment to a rigorous, fulltime artistic practice. Her appointment to the board was a strategic and necessary intervention, one that reflected the urgent need to amplify Indigenous voices and embed principles of self-determination within arts governance structures. Groom’s tenure on the NAVA board not only set a precedent for future First Nations representation but has also contributed meaningfully to reshaping discourses around equity, cultural authority, and leadership across the broader arts sector.

My professional relationship with Groom evolved organically from this initial institutional encounter into an ongoing collaboration grounded in mutual respect, shared purpose, and a belief in the transformative capacity of contemporary art. Our work together has been underpinned by an abiding commitment to ancestral knowledge, intergenerational memory, and cultural continuity. These relational threads—woven through dialogue, creative exchange, and collective acts of remembering—form the ontological basis of Groom’s practice and our ongoing curatorial engagement. Together, we recognise art not only as a medium for aesthetic expression but as a conduit for healing, truth-telling, and spiritual activation.

The Lodge represents a culmination of Groom’s lived experience, her political engagement, and her artistic vision. As a work of autobiographical performance, it draws from multiple epistemologies—First Nations ceremonial practice, quantum theory, and metaphysical speculation— to explore the indivisibility of time, space, and being. Rather than unfold in linear narrative form, the work presents a non-sequential, multi-dimensional cosmology wherein past, present, and future collide and coalesce as one unified continuum. Groom enters this field through embodied ritual, traversing landscapes of memory and power to reconnect with Ancestors and reposition herself within the spiritual architecture of Country.

Cinematically, The Lodge invokes the surrealist legacy of David Lynch, whose Twin Peaks mythology posits parallel realms of moral polarity—light and shadow, the White Lodge and the Black Lodge. Groom reimagines this metaphysical framework within the Australian settlercolonial context, foregrounding the contested terrain of Ngunnawal Country, now referred to as Canberra. Here, she unearths the hidden histories and unresolved tensions that haunt the nation’s capital, activating a deeper spatial awareness that resists colonial amnesia. The work compels viewers to relinquish the safety of linear interpretation, inviting them instead into a liminal state of encounter—one that foregrounds justice, memory, and the spiritual charge embedded within land.

Importantly, The Lodge also marks a return for Groom to Ngunnawal Country, the site of her early activism at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy and later, her political engagement within the walls of Parliament House as the youngest director of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples. This return is not simply geographic; it is ceremonial and cyclical. Through the performance, Groom reactivates the songlines of her Ancestors, enacting a counter-cartography that runs parallel to the geometries imposed by Walter Burley Griffin and the colonial planning apparatus. The work becomes a site of convergence—a ritual undoing and reweaving of histories, sovereignties, and futures.

SHARNI JONES

Sharni Jones’ peoples are the Kabi Kabi/Waka Waka on her maternal side. As the acting Director, Sharni is currently leading the Aboriginal Water Program at the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. This aligns with her values to embed selfdetermination, cultural authority and agency into arts, cultural and environmental policy and practices.

Ritual, Resistance, and Reclamation in the Heart of Empire

Amala Groom’s moving image work The Lodge is a conceptual and autobiographical performance that draws together the personal, the political, and the spiritual into a single visual and ceremonial act of sovereign resistance. As the third installment in her Raised by Wolves series, the work continues Groom’s ongoing inquiry into the relationship between body, land, spirit, and the colonial state. Through a rich interplay of symbolism, lived experience, and critical theory, Groom positions herself—both literally and allegorically—within Canberra’s Parliamentary Triangle, an epicentre of Australian colonial power. At the same time, she reclaims the space as an ancient ceremonial ground charged with First Nations spiritual presence and ancestral authority.

In The Lodge, Groom reprises the figure of the Bride, a character previously featured in her work as a vessel through which to explore the burdens and resistance of Aboriginal womanhood. The Bride is not a passive archetype of purity or submission, but rather a powerful personification of both trauma and transcendence. Draped in a white wedding dress and bound with red rope, the Bride embodies the tension between spiritual sovereignty and corporeal captivity—symbolising the enduring impacts of colonisation on First Nations women’s bodies and lives. The red rope functions as both constraint and connection: it is the ‘red tape’ of bureaucratic oppression, and the umbilical cord that binds the physical and spiritual bodies. Groom weaves this rope along Anzac Parade, physically enacting a metaphysical journey across time, place, and trauma.

This journey unfolds across the Parliamentary Triangle, a landscape that is both sacred and contested. While it houses the institutions of Australian government, it also sits atop Ngunnawal Country—an ancient meeting place for corroboree and ceremonial exchange among First Nations language groups. Groom’s traversal of this space, from Mount Ainslie to the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, Old Parliament House, and finally New Parliament House, activates an alternative map—one built on songlines, kinship, and resistance. The work does not simply critique colonial structures; it ritualistically reclaims them, re-inscribing the land with spiritual geometries and Indigenous authority.

Crucially, The Lodge engages with the esoteric underpinnings of Canberra’s urban design. As detailed in Peter Proudfoot’s The Secret Plan of Canberra (1994), the city’s founding architects—Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin—were deeply influenced by Theosophy and geomancy. Theosophy, an esoteric spiritual movement rooted in Eastern mysticism and Western occultism, envisioned the world as a site of cosmic struggle between higher and lower planes of existence. The Griffins sought to manifest this spiritual philosophy through urban planning, embedding sacred geometries and cosmological alignments into the layout of the capital. Their ideal city was not merely functional but aspirational: a metaphysical site capable of channeling divine energies.

Groom reactivates this latent spiritual infrastructure, exposing its contradictions. While the Griffins’ geomantic intentions were visionary, their designs were ultimately coopted to serve the colonial state. The Triangle—symbolically powerful and geometrically precise—has become a fortress of bureaucratic dominance. In Groom’s reading, it now functions as a “Black Lodge,” a term borrowed from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks series, which she references explicitly in the work’s title. In Lynch’s mythology, the Black Lodge and White Lodge are interdimensional spaces where good and evil blur, where the metaphysical laws governing reality are inverted. Groom draws a potent parallel: Canberra, too, is a place of doubled meaning—a space where sacred ground and colonial artifice exist in constant tension, where spiritual truths have been occluded by a veneer of state power.

Through cinematic editing and visual trickery, Groom disappears and reappears across this landscape, connected always by the red rope. The Bride’s movements become a loop—ritualistic, exhausting, and unresolved. Each iteration of the journey brings her to the gates of Parliament House, but each time she is cast back to where she began. This cyclical temporality—what might be called a sovereign time—echoes Indigenous understandings of time as nonlinear, as continuous presence. In this, The Lodge becomes a spiritual enactment of both repetition and transformation. The Bride is caught in a war not just of politics, but of metaphysics—a struggle between sovereign cosmologies and colonial illusions of permanence.

The work crescendos as the Bride reaches the fire at

the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, a site of deep personal and political importance for Groom, who was actively involved in protest movements there between 2007 and 2011. The fire is a source of renewal, a spiritual centre where resistance is re-fuelled by ancestral presence. Groom’s ceremonial act of circling the fire three times—each turn honouring one of the cardinal directions and its associated element— grounds the work in Indigenous law and cosmology. It is here that the Bride finds momentary peace, not as escape, but as ignition. She is not retreating from struggle; she is recalibrating her power.

The final sequence sees her ascend once more—into Parliament House and ultimately beyond it. Her last act is to disappear into the bush behind the citadel, not as a victim, but as a sovereign Wiradyuri woman. This conclusion offers no resolution, no final liberation. Instead, it insists on continuity—the spiritual survival and embodied presence of First Nations peoples despite ongoing colonial violence.

Visually, The Lodge is stunning and deliberate weaving together elements of surrealism, performance art, and site-specific installation. Its aesthetics draw on sacred geometry, landscape cinematography, and ceremonial movement. Conceptually, it merges Indigenous epistemologies with speculative cosmology, presenting an ontological challenge to the dominance of Western political architecture. Groom’s work does not merely ask to be seen—it demands to be felt, metabolised, and witnessed.

In the broader context of Groom’s Raised by Wolves series, The Lodge occupies a critical middle ground. While The Union explored relational sovereignty and The Proposal delved into cultural contract, The Lodge intensifies the spiritual stakes. It is not only a confrontation with colonial architecture but a reclamation of spiritual architecture. It prepares the ground for the final works in the series, which will fully enter the interdimensional and metaphysical, tracing a path from systemic resistance to cosmic resolution.

ceremonial offering, a philosophical inquiry, and a sovereign act of refusal. It reclaims not just space, but time, and reminds us that the future is not predetermined. It is a fire we must keep tending.

Image Amala Groom

The Lodge 2025 (production still)

Single-channel video, 6K UHD video, colour, sound, 11:11 mins

Image credit: Ryan Andrew Lee

JACK WILKE-JANS

Jack Wilkie-Jans is an Aboriginal Affairs advocate, artist, arts worker, policy theorist, and writer from Weipa and Mapoon, Cape York Peninsula. Living in Gimuy (Cairns, Queensland), Jack is a Waanyi, Teppathiggi and Tjungundji man of British, Vanuatuan and Danish heritage.

Through her multidisciplinary practice, Amala Groom continues to reframe First Nations experiences within the context of high contemporary art. Her works operate across registers—personal, political, historical, and speculative—making visible the ghosts of colonialism while animating the spirits of resistance. The Lodge is a

Production credits:

Writer/Director/Performer: Amala Groom

Producer: Michaela Perske

Cinematographer: Ryan Andrew Lee

Creative Director: Kristine Townsend

Cultural Consultant: Ngunnawal Elder Wally Bell

Editor: Elliott Magen

Composer: Ben Rosen

Grade: Daniel Pardy

Camera Assist: Luke Patterson

Rope Assistant: Kate Harriden

Runner: Nyssa Miller

Runner: Cath Webb

The artist would like to thank; the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, Australian War Memorial, Bandalang Studio (Australian National University), Old Parliament House, and Parliament House.

This project has been supported by the ACT Government Arts Activities Funding and assisted by the Australian Government through Creative Australia, its principal arts investment and advisory body. Groom is currently an Australian National University Visiting and Honorary Associate, Bandalang Studio Residency, College of Systems and Society

Image Amala Groom

The Lodge 2025

Single-channel video, 6K UHD video, colour, sound, 11:11 mins

Photo by Hilary Wardhaugh

44 Queen Elizabeth Tce, Parkes, ACT Open 11am to 5pm Tuesday to Saturday canberracontemporary.com.au

Canberra Contemporary Art Space Incorporated is assisted by the Australian Government through Creative Australia, its principal arts funding and advisory body.

Canberra Contemporary acknowledges the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, the Traditional Custodians of the Kamberri/Canberra region, and recognises their continuous connection to culture, community, and Country.