A GUIDE TO BOHEMIAN SAN FRANCISCO JASMIN DARZNIK

WELCOME

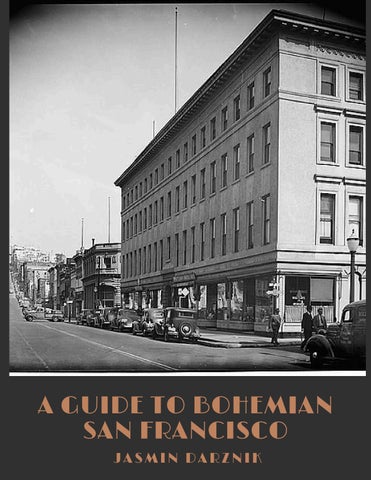

Thistourof1920sSanFranciscois inspiredbyTheBohemians,mynovel aboutphotographerDorotheaLange.In additiontopicturesofLangeandother membersofthe"cast,"I’veincluded landmarksatwhichscenesinthebook takeplace,suchasMontgomeryBlockand Coppa's,aswellasstoriesaboutthistime inTheCity'shistory.Ihopeyouenjoy seeingthesightswithme!

I found myself in San Francisco."

Dorothea Lange

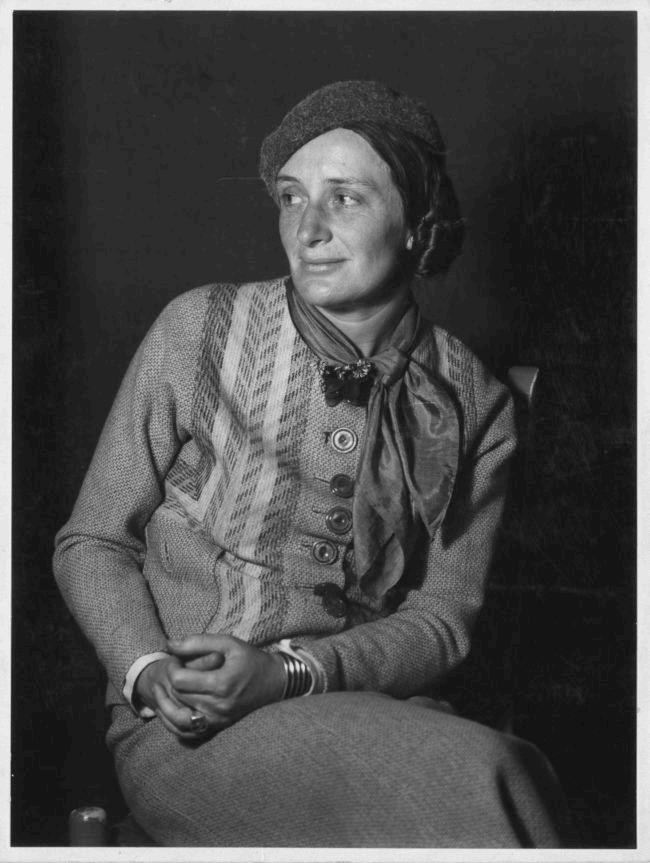

DOROTHEA

LANGE

AT THE TIME SHE CAME TO SAN FRANCISCO

Women of the 1920s

10 FASCINATING FACTS ABOUT DOROTHEA LANGE

Her Name Wasn't Always Dorothea Lange

ShewasbornDorotheaNutzhornin1895,thedaughteroffirstgenerationGermanimmigrantswhoputdownrootsinHobokenand wentbythatnameuntilshelefttheEastCoastin1918

Thoughsheneverexplainedherreasonsfortakinghermother’s surname,thecross-countrymovelikelyaffordedherthechancetobreak freeofherpainfulpast,whichincludedherfather’sabandonmentofthe familywhenshewastwelve Whateverherreasons,onceshesettledin California,sheonlyeverwentbyDorotheaLange.

She Was a Polio Survivor

Atageseven,Langecontractedpolio, whichleftherwithaweakenedright footandpermanentlimp.Yearslater shewouldremarkoftheexperience: “Itformedme,guidedme,instructed me,helpedme,andhumiliatedme I’venevergottenoverit,andIam awareoftheforceandpowerofit ” Shespentayearconfinedathome, andwhenshefinallyreturnedto school,shewasmockedbytheother childrenandshamedbyherown family Eventually,shetrainedherself towalksothatherlimpwasmoreor lessimperceptible Shealsoworelong skirtsandpantstofurtherdisguiseit

Lange’slegendaryempathyasa photographergrewfromthistrauma Shehadaparticulargeniusforthe languageofthebodyandcould suggestawholestoryfromhow peopleheldthemselves Herlimpalso madehervulnerableinwaysshedrew uponinherwork Whenwalkingintoa migrantcampduringtheDepression, forexample,she’dsometimeslet peopleseeherdisability,which helpedherestablishaconnection withthem

She Was a Truant

After Lange’s father disappeared, her mother went to work as a librarian, then as a social worker. Since the commute took her to New York, she enrolled her daughter in a school on the Lower East Side. Lange would later speak rapturously of the hours she spent ditching school to roam around the city, looking at all different kinds of people.

During this time, she learned to make herself invisible—to carry herself in a way that attracted the least attention—which allowed her greater freedom of movement. This talent would serve her well later when she became a documentary photographer. She knew how to get lost and how to fall in with strangers and felt these were an essential part of creating good pictures.

A Thief Altered Her Fate

In1918,Langedecidedtotakeatrip aroundtheworld Shesavedupforit forseveralyears,workingasa photographer’sassistantinvarious Manhattanstudios WiththeUS havingjustenteredthewar,itwas impossibletotraveltoEurope(the usualdestinationforapersonwithan artisticbent),andsoshewentwest intendingtotraveltoMexico,Hawaii, andtheFarEast.

Herplanswerederailedjustassoon asshearrivedinSanFrancisco.Athief stoleallhermoneyandshewas suddenlystrandedinacitywhereshe knewnoone.Everresourceful,she gotajobinafive-and-dimeshop,

wheresheworkedasaphotofinisher. Alittleoverayearlater,shewas runningoneofthepremierportrait studiosinSanFrancisco California, theplaceshe’donlymeanttovisit, becametheheartofherlife’swork andallonaccountofathief.

She Started As a Society Photographer

While Lange’s name is synonymous with documentary photography, she only started on this path after many years as a portrait photographer. In the 1920s, her clients included the wealthiest families in San Francisco—the LeviStraus family, the de Youngs, and the Hasses.

It may be hard to reconcile this work with her documentary photography, but Lange never regretted the time she spent in the studio. Portrait photography taught her how to work closely with people, how to draw them out, and how to show them not just as they wished to be seen, but how they truly were. She never stopped making portraits; what changed were the subjects.

She Wasn't a Solitary Genius

SanFranciscointhe1920swasa fantasticallyexcitingplacefor womenartists.The1906Earthquake andFireshaddisplacedthe photographyestablishment,which woundupcreatingopportunitiesfor women

By1918,theyearLangecametothe city,photographerssuchasImogen Cunningham,AnneBrigman,and ConsueloKanagawerebusydoing phenomenalworkthere.Theywere Bohemians,bentonlivingtheirlives ontheirownterms Langewasable tofindfriends,colleagues,and mentors Thiscommunity emboldenedandtransformedher

She Didn't Call Herself an "Artist"

The reigning in Lange’s d advocated f rose to the l woman from background indulge such with artistic brought an work, yet sh “tradeswom pride in the

A Homeless Man

Pulled Her Out of the Studio

and Into the Street

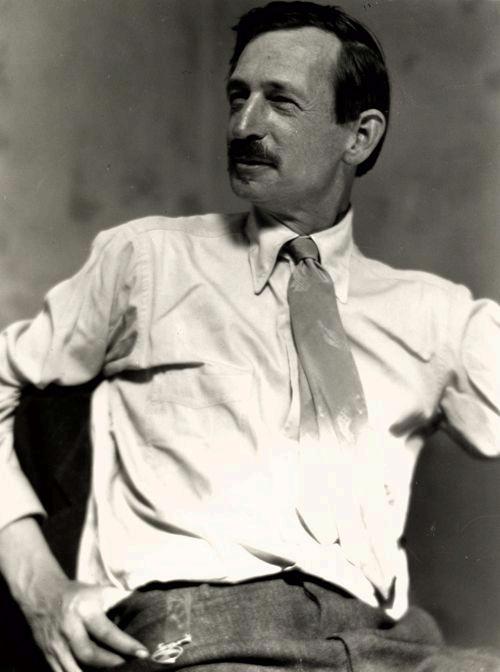

TheGreatDepressionhit bothLange’sandher painter-husbandMaynard Dixon’sbusinesseshard Itwasfromthewindowof herstudioon MontgomeryStreetthat shewitnessedstrikesand thestrugglesofthe unemployedand homeless

Onedayshelookedup fromherworkandsawa manwhowaslost, destitute,andalone.It wasamomentof

profoundreckoning,as shewouldlaterreflect: “Thediscrepancy betweenwhatIwas workingon…andwhat wasgoingonupthe streetwasmorethanI couldassimilate ”

Thatwasthefirsttime shewentintothestreets withtheaimoftaking photographs.Thoughit tooktimetodismantle herbusiness,fromthen on,sheknewshehadto bepartofwhatwas happeningintheworld.

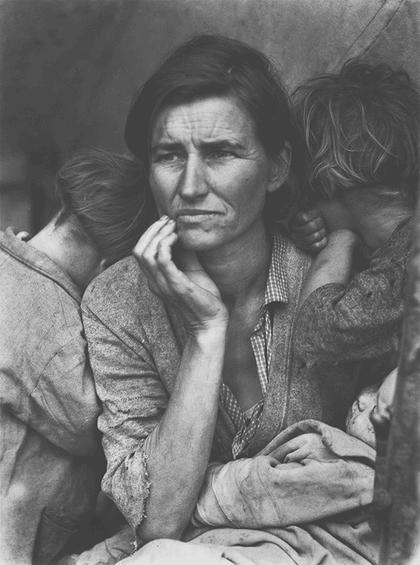

Her Iconic Photograph,

“Migrant Mother,” Almost Didn’t Happen

One day in 1936, Lange was returning home to the Bay Area after a month alone on the road. She’d been separated from her young sons, which was by then a regular occurrence given the nature of her work. She was tired and frazzled and eager to make it home quickly.

When she saw a handwritten sign with the words “Pea Pickers Camp,” she drove past it. A few miles on, she suddenly decided to turn around.

“Migrant Mother,” one of the most iconic and most reproduced images in the history of photography, was taken on that day.

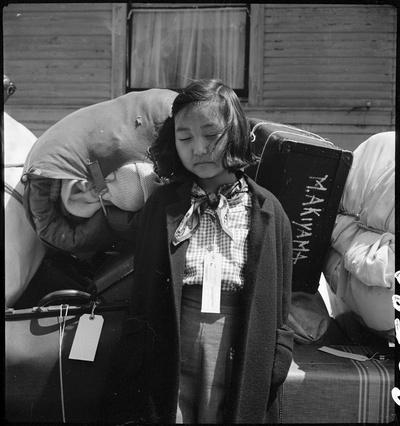

She Was Regularly Censored for Her Photographs of People of Color

Whenworkingforthe FarmSecurities

Administrationduringthe GreatDepression,she wasexpresslytoldto photographwhite Americansasthiswould engenderthemost supportforNewDeal programs Lange regularlyfloutedthese rules,photographing Asian,Latino,andAfrican Americans,aswellas Euro-Americans These pictureswerenever includedinofficial governmentpamphlets, butshecontinuedtaking themanyway

Later,whenworkingfor theWarDepartment duringWWII,shewas forbiddenfrom documentingthe Japaneseinternment campsinanywaythat suggestedtheywere anythingotherthan organizedanddignified. Shefoundcreative workarounds,suchas photographingthe shadowofabarbed-wire fenceratherthanthe fenceitself

Langealsosmuggledout hermoredaringpictures, lendingthemtothe effortstohaltthe internment Eventually shewasfired,andallher photographsofthe campswereimpounded Theyonlybecameknown tothepublicseven decadesaftershetook them.

MONKEY BLOCK

A massive four-story building that stood where the Transamerica Pyramid stands now, Montgomery Block, or Monkey Block, as it was affectionally called, was home to some 800 artists and writers. At the crossroads of North Beach, Chinatown, and the Financial District, it was the beating heart of Bohemian San Francisco.

"THE FIRST INCARNATION OF COPPA’S OPENED IN 1903. IT WAS LOCATED IN THE MONTGOMERY BLOCK, WHERE THE TRANSAMERICA PYRAMID NOW STANDS. THE ORIGINAL COPPA’S WAS FREQUENTED BY BOHEMIAN ARTISTS, WHO DECORATED THE WALLS WITH MURALS.

ALTHOUGH THE SOLIDLY BUILT MONTGOMERY BLOCK WITHSTOOD THE 1906 EARTHQUAKE, IT WAS HEAVILY DAMAGED BY FIRE THAT FOLLOWED. THE RESTAURANT’S WINDOWS SHATTERED IN THE HEAT OF THE FLAMES, AND VANDALS STOLE ALL THE BOOZE.

LOYAL ARTISTS LOCATED THE DISCOURAGED GIUSEPPE COPPA, WHO WAS LIVING IN A REFUGEE CAMP AT THE PRESIDIO, AND PERSUADED HIM TO PREPARE ONE LAST MEMORABLE FEAST AT THE BURNED-OUT PREMISES. THIS POSTCARD DEPICTS THE FOURTH OF SIX LOCATIONS OF COPPA’S, WHICH WAS THEN LOCATED AT 534 WASHINGTON STREET. ALTHOUGH COPPA’S LEGENDARY FOOD HAD NOT CHANGED, AND ARTISTS CONTINUED TO PAINT WONDERFUL MURALS ON THE WALLS, PROHIBITION WAS ENACTED SHORTLY AFTERWARD. COPPA DECLARED, “IT CAN’T BE DONE!” AND CLOSED THE DOORS."

SIGNALS FROM TELEGRAPH HILL (2017)

What's a Flapper

Anyway?

The earliest use of the word dates back to the 18th century and refers to a wild duck that couldn’t yet fly. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was used to refer to prostitutes. By the 1910s it referred to preteen girl and by the 1920s it assumed the meaning you might recognize today: a young, independent woman. Not every woman of the period would’ve called herself a flapper, but all the really smashing girls did.

(I think we’re all clear on where these three ladies stood, wouldn’t you say?)

story Monkey Block, had survived the 1906 earthquake only to fall into grave, if picturesque, disrepair. To enter, he didn’t draw a key from his pocket; the door was never locked, night or day. Crumbling plaster, dark, dank stairways, ancient plumbing you probably had to be an artist to love a place like that, which he was, so he did.

Inside, on the third-floor, he’d built a kind of temple. He filled it with Native American textiles, baskets, pottery, saddles, lariats, bridles. Here and there the walls were hung with his own paintings, which were luminous, colorful, breathtaking.

Wherever he went—in the City and surrounding areas, but also on long trips to Arizona and New Mexico he carried little drawing pads in the pockets of his roomy jackets. As he roamed the West’s plains, mesas and deserts by foot, horseback and buckboard, he’d make hundreds of small, precise, painstakingly annotated drawings and sketches. When he returned to San Francisco, he’d transform these into paintings.

For years he shuttled between San Francisco and the Southwest. Eventually the Bohemian bon vivant in him surrendered to the cowboywanderer-seeker. He left the City for good in the mid-1930s, but until then he went on working from field sketches, memory, and love.

When he was a San Franciscan, Maynard Dixon strode through the streets each morning in a tailored black suit, black Stetson hat, and black cape. He was tall and very slender, with a long face, blue eyes, and blueblack hair. “Walks like a deer,” someone once observed, which would have been true if deer went around in hand-tooled, high-heeled cowboy boots.

Sometimes he sang a Navajo chant or Mexican folk song as he walked. Sometimes he just cursed the fog—loudly. Under his left arm he’d carry a canvas, and with his right hand he’d clutch the silver-tipped cane that bore the same image of a Thunderbird that served as his signature.

At 728 Montgomery Street he came to a tall green door. The building, like the nearby four-

story Monkey Block, had survived the 1906 earthquake only to fall into grave, if picturesque, disrepair. To enter, he didn’t draw a key from his pocket; the door was never locked, night or day. Crumbling plaster, dark, dank stairways, ancient plumbing you probably had to be an artist to love a place like that, which he was, so he did.

Inside, on the third-floor, he’d built a kind of temple. He filled it with Native American textiles, baskets, pottery, saddles, lariats, bridles. Here and there the walls were hung with his own paintings, which were luminous, colorful, breathtaking.

Wherever he went—in the City and surrounding areas, but also on long trips to Arizona and New Mexico he carried little drawing pads in the pockets of his roomy jackets. As he roamed the West’s plains, mesas and deserts by foot, horseback and buckboard, he’d make hundreds of small, precise, painstakingly annotated drawings and sketches. When he returned to San Francisco, he’d transform these into paintings.

For years he shuttled between San Francisco and the Southwest. Eventually the Bohemian bon vivant in him surrendered to the cowboywanderer-seeker. He left the City for good in the mid-1930s, but until then he went on working from field sketches, memory, and love.

MAYNARD DIXON'S STUDIO

While many of the places in The Bohemians have disappeared, the building the housed Maynard DIxon's studio on Montgomery Street is still there. If you want to step back in time, stroll around Jackson Square, the part of the City where Dixon kept his studio. It's one of the oldest corners of the City, having survived the 1906 earthquake and fires.

Photograph: Dorothea Lange

When I moved back to the Bay Area, where I’d grown up, in 2013, I could barely recognize whole swaths of San Francisco anymore, but one part of it, North Beach, was almost exactly the same. More than ever, spending time there had the feeling of a pilgrimage a pilgrimage to the City’s past and my own.

Then I heard about a place called Monkey Block, a fourstory artists’ colony that had

stood where the Transamerica Building is now. I immediately fell deeply in love with it or rather, the idea of it.

Learning about this magnificent old building and its illustrious roster of past inhabitants, I was astonished to learn that so many women artists a few known to me, many not—had made their homes in the city at the same time. I tried to imagine the conversations that had taken

place in Monkey Block and the nearby streets of North Beach almost a hundred years earlier. I wanted to know what had drawn them to this place, and what sorts of lives they’d led in San Francisco.

I began casting around for people who’d been part of the world for which Monkey Block had served as a wild but steady heart. Was it a coincidence that they’d all lived here, or was there something about the City that spoke to them and, if so, had that “something” made its way into their work?

In May 1918, a 23-year-old woman named Dorothea Nutzhorn set off on a roundthe-world trip. She’d been working as an assistant in a Manhattan portrait studio, but then her boss shuttered the business a casualty of America’s entry into World War I. In a way, it was her lucky break.

For years she’d been saving money to travel, and now she could. Europe, the usual destination for a young person with an artistic bent, was out of the question, so she went west, toward California. By the time she got to San Francisco, two

had happened: she’d been robbed of all her money and she’d renamed herself Dorothea Lange.

The city she found was just a decade old, having been almost totally destroyed in the earthquake and fires of 1906. Then, as now, it was a city on the edge of the continent, a place of beauty, promise, and tragedy. In May of 1919, the month she arrived, soldiers were shipping out by the thousands from the West Coast and the Spanish flu had just begun its advance.

The bright moneyed days of the Jazz Age glimmered in the far distance, but for women, this was a time of possibility. In the first decades of the 20th century, women, particularly young women, were in open rebellion against the past. Lange had first joined this rebellion in her native New Jersey, albeit on her own terms, but its most delightfully raucous interludes took place during those first years in Northern California.

“I found myself in San Francisco,” she’d later say.

The self she found was profoundly shaped by the

the company she fell in with.

Since 1901, nearly two decades before Lange arrived in California, photographer Anne Brigman had been trekking to the Sierra Nevada, photographing herself on the edge of a cliff like a swaggering buccaneer, or else posing nude in the crook of a wind-warped tree. 1901 was the same year another pioneering photographer, Imogen Cunningham, bought her first camera.

Soon enough Cunningham was causing a scandal by photographing male nudes. Eventually, her skill would earn her a place alongside Ansel Adams and Edward Weston in the pioneering Group f/64. Working in the same vibrant milieu was Consuelo Kanaga, who’d bring a radically inclusive eye to her portraits of people of color.

San Francisco had always been a welcoming place for artists, but it was a disaster of epic proportions that kicked the door open for these women photographers. The earthquake and fires of 1906 had devastated San Francisco’s artistic community. Many members set off for Carmel, which was then a sleepy coastal village,

or to Berkeley and Marin County. Some went to Mexico. Others, like Lange’s own mentor, Arnold Genthe, returned to New York.

It’s from this vacuum that a band of women photographers emerged. Of necessity and temperament, they were resolved to earn their own money. During their time in San Francisco, these women not only took groundbreaking pictures but initiated and sustained connections with one another. As each woman asked what kind of pictures she wanted to take, she also faced the question of what kind of life she wanted to live, and it was in looking at one another that they began to answer that question.

Before coming to California, Lange had dipped a toe into the New York art scene, not as a participant but as a spectator. A practical young woman of German immigrant stock, she was years away from thinking, much less of calling, herself an artist. “Tradeswoman” is what she thought of herself back then. I wonder how much this owed to the sexism of the East Coast photography establishment of her youth. For all his professed modernity, the

IMOGEN CUNNINGHAM

Lange's lifelong friend, she operated one of the earliest woman-owned portrait studios in the country.

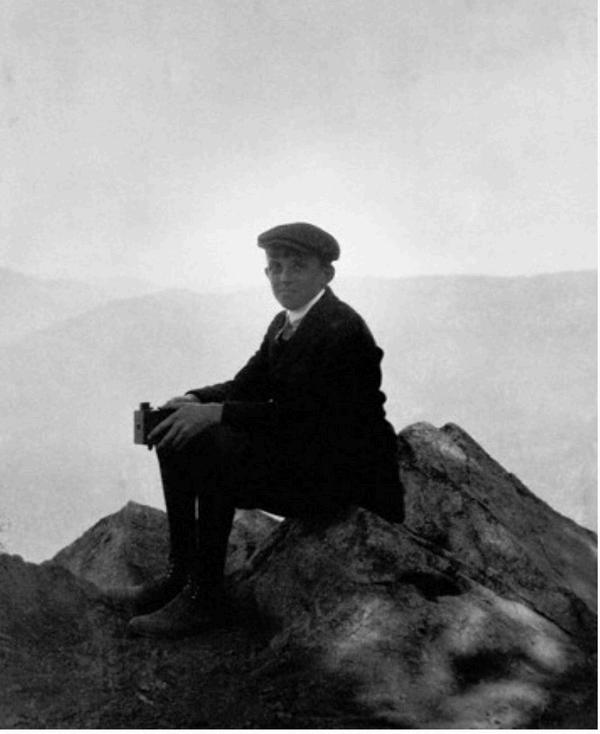

ANNE BRIGMAN

A renegade whose signature photographs were taken in the Sierra Nevada Mountains,

CONSUELO KANAGA

The photojournalist who wowed Lange with her daring work and vision.

reigning king of the New York photography world, Alfred Stieglitz, didn’t bar women from his circle outright, but he might as well have, given the very small number of women whose work he chose to promote.

San Francisco had no king. What it had was a number of very successful women photographers. Imogen Cunningham, one of the first photographers Lange met in the City, was one of them. She’d attained a degree of critical recognition that was still rare for a woman in what was still thought of as a man’s profession. But that wasn’t all that impressed Lange.

Cunningham had run a portrait studio in Seattle, and while she continued to do portrait work in San Francisco to support herself, when she and Lange met, Cunningham was making art photography.

Notably, she also served as an advocate and mentor for many other women photographers. She joined the Women’s Art League in San Francisco, which Dorothea Lange would also join, and became very close to sculptor Ruth Asawa, whom she’d photograph extensively.

Consuelo Kanaga also upended Lange’s notion of what photography could be and do. In 1915, at the age of 21, Kanaga had been hired as a reporter and features writer for The Chronicle a real feat for a woman then. She soon showed a talent for photography and began contributing pictures to the paper as well. She and her friend Louise Dahl (later Louise Dahl-Wolfe) roamed the City on Sundays looking for interesting people and places and found them in spades.

Kanaga was the first woman newspaper photographer Lange had ever met. Many years later, Lange shared her first impressions of this renegade photographer:

“[She] lived in a Portuguese hotel in North Beach, which was entirely Portuguese working men, except Conseulo… She’d go anywhere and do anything. She was perfectly able to do anything at any time the paper told her to. They could send her to places where an unattached woman shouldn’t be sent and Consuelo was never scathed. She was a dasher.”

Lange wouldn’t begin taking documentary photographs until 1932, by which time Kanaga had been practicing a version of that art for over a decade.

Dorothea Lange’s coming-ofage harkened back to a San Francisco where artists and writers could still arrive with nothing and make a home, where a young woman with no connections or money but heaps of grit might encounter a new version of herself. Researching and writing about her formative years, I learned that art like the people who make it thrives in communities. Solitude and independence are necessary conditions for most creative people, but a life of sustained artistic practice requires friendship, mentorship, and community.

In the first decades of the 20th century, women created these conditions for one another. Each of the women photographers Dorothea Lange met in San Francisco was brilliant, tenacious, and brave. Taken together, they were a force.

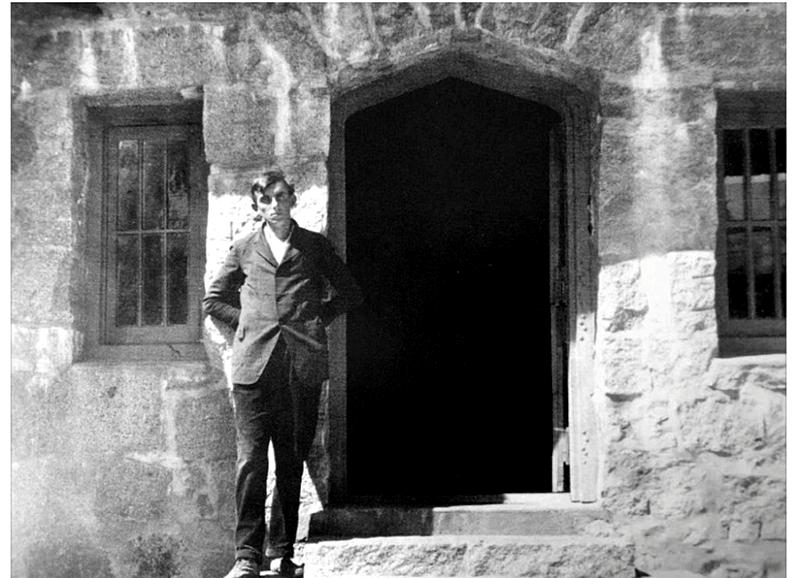

In 1919, a seventeen-year-old San Francisco boy fell seriously ill. The second, and deadliest, wave of the Spanish Flu had reached the City. It struck down the young with particular cruelty.

The boy had always been a bit different–restless and fidgety and given to long rambles on Baker Beach and through the Presidio, but now, fevered and nearly skeletal, he developed a phobia. A very severe phobia of germs and people. He was sure that if he stayed in San Francisco he’d die.

He begged his parents to let him visit Yosemite, a place he’d first visited when he was fourteen. The doctor advised against it, but the boy was so persistent that his parents eventually relented.

A month later, the boy, whose name was Ansel Adams, returned to San Francisco. His cheeks were tanned and his gauntness was gone. For the rest of the life, he credited Yosemite for his recovery. Nature became both his faith and his temple, and photographing it became his life’s calling.

920 Sacramento

Another stalwart survivor: the building at 920 Sacramento Street. Under the tenure of Donaldina Cameron, it sheltered some 2,000 girls and women who survived the human trafficking that flourished in San Francisco for decades. In The Bohemians, this is the place where Caroline Lee grows up.

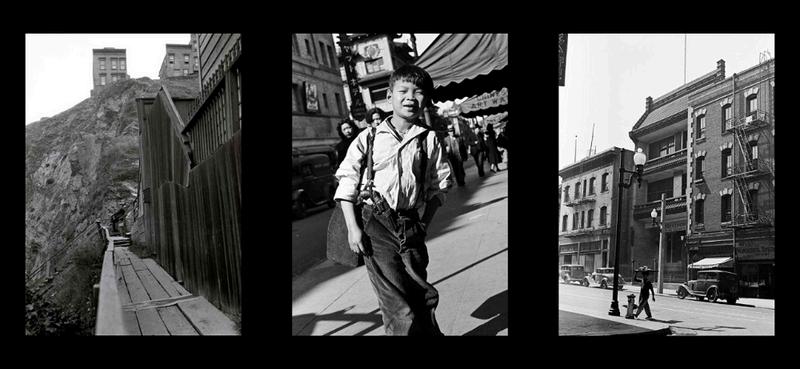

Chinatown

In Lange's day, and for many years afterwards, San Francisco was a segregated city. Home to one of the largest Chinese and Chinese American populations in the country, San Francisco barred them from living outside its boundaries, a ten block by ten block area.

Chinatown

Postcards of The City