when we bought the Locanda from my nephew Bonifacio, who had run it for several years since the death of my father in 1980, we had no idea how much time had taken its toll.

Our plans to renovate it were made without fully considering the age of the building, which was bought by my father in 1936 and opened, in its original form, in 1947.

In our family, the Locanda has always been thought of as a dream. There is no way to put into words the magical perfection of the water surrounding the oldest island in the Venetian lagoon and the spiritual feeling of the 5th-century cathedrals, which we believe were built by people who were also somehow imagining the future Locanda. This was my father’s feeling, and I assure you that we feel the same way.

The renovation, which we thought would take one year, will be completed by the end of this year. We have done a very good job, keeping in mind the charm of both the building and the island.

We decided to make the accommodations of the hotel nicer. Your stay will be more pleasant, because we believe that a stay at the Locanda should be unique and more comfortable. We used the long wing, previously dedicated to events, to build additional suites. We now have twelve magnificent suites facing a garden full of flowers and the two churches.

Torcello is the real Venice so we considered another change. The food will remain simple as always, but we will serve mostly traditional Venetian specialties, which are unfortunately becoming harder and harder to find. We will host only a minimum number of private events, and with fewer guests. If you decide to stay, you shouldn’t have to share the space with people who are there for a different purpose.

We shall be in operation just before the spring of 2026. I will be delighted to welcome you to Torcello.

Yours sincerely,

arrigo cipriani

46 Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein 80 The Khao Yai Art Forest

A lifelong admirer of monsters, del Toro brings Shelley’s creation to life as a story of love, fear, and recognition. His Frankenstein is less about horror than about the fragile line between creator and creature, reminding us that the monster is always a mirror of ourselves.

The Future, Rendered

Ayoung Kim, recipient of the 2025 LG Guggenheim Award, crafts immersive worlds that merge myth, science, and digital technology. Her work collapses boundaries between human and machine, past and future, offering a visionary lens on how art can illuminate the ethical and emotional dimensions of our technological age.

In Thailand’s Khao Yai region, a new open-air museum places contemporary art within a living forest. From Louise Bourgeois’s towering spider to Fujiko Nakaya’s drifting fog, the Art Forest invites visitors to experience art at the pace of nature—slow, contemplative, and inseparable from the land.

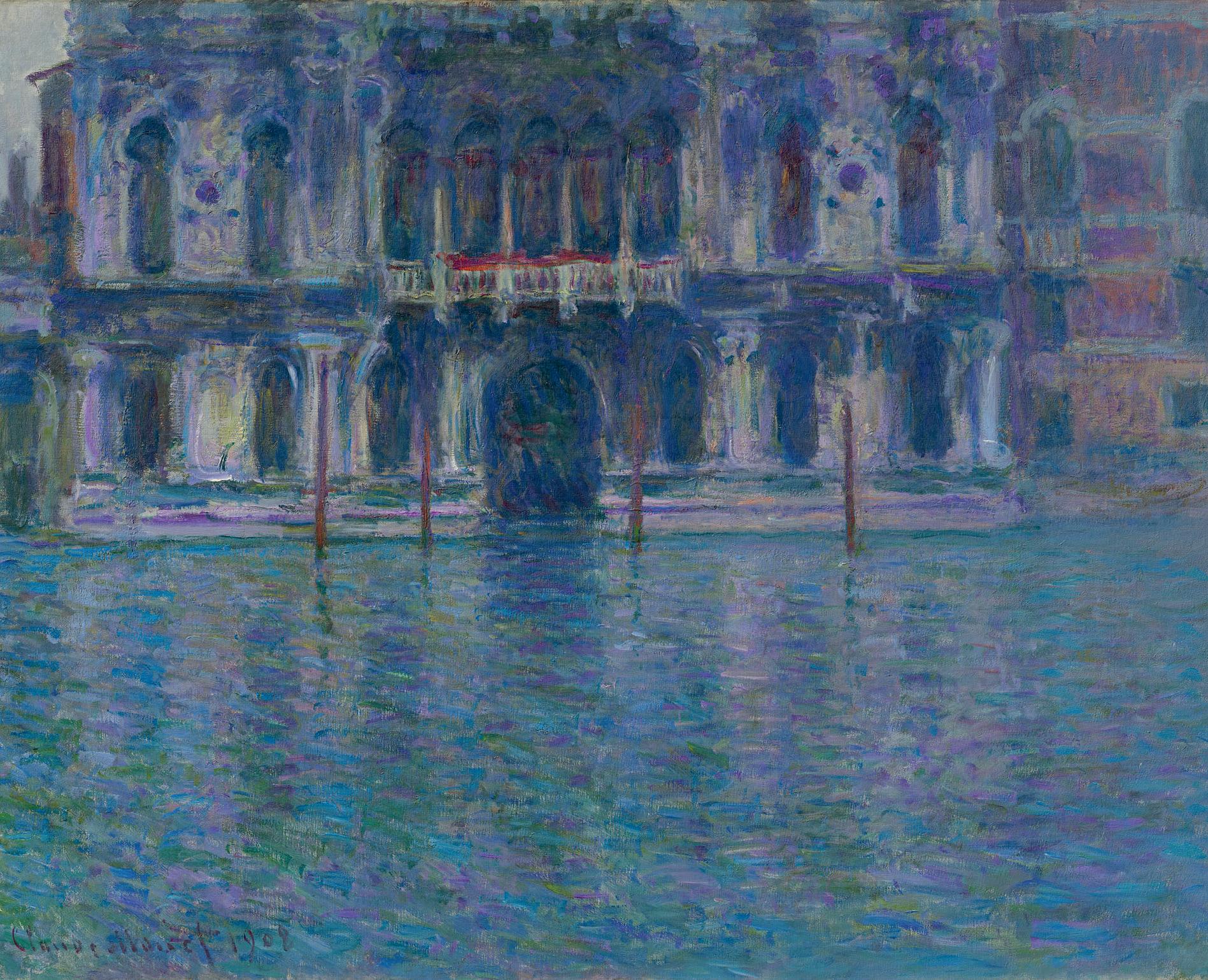

In 1908, Claude Monet reluctantly journeyed to Venice, where the city’s shifting light transformed his art. From palaces dissolving into water to skies mirrored in the lagoon, these luminous canvases became his final great works—an elegiac meditation on beauty, impermanence, and the enduring power of reflection.

Vermeer’s enigmatic interiors come into focus at the Frick through his depictions of women with letters— moments where language becomes lifeline. Like today’s texts and messages, each word is mined for tone and implication, revealing how intimacy and meaning are carried in the smallest turns of phrase.

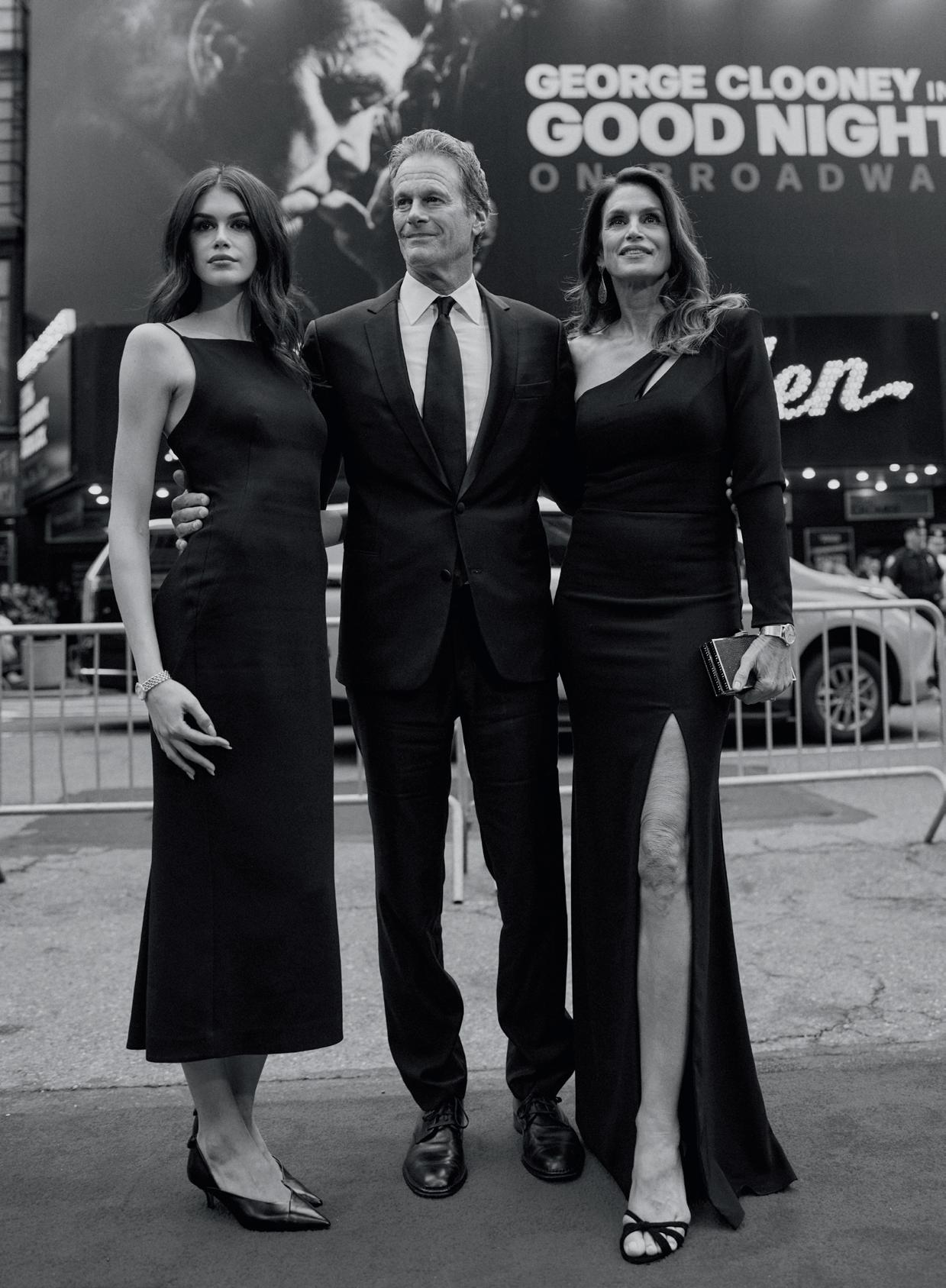

Emilio Madrid’s photojournal chronicles the Broadway debut of Good Night, and Good Luck, starring George Clooney. From the red carpet arrivals and backstage anticipation to the Casa Cipriani afterparty where the cast celebrated glowing first reviews, the images capture the glamour, intimacy, and exhilaration of an unforgettable opening night.

EDITOR IN CHIEF ANGELO BIANCHI

EXECUTIVE EDITOR STEFANIA GIROMBELLI ART AND DESIGN JUSTIN THOMAS KAY

ADVISORY HENRIK JAN GUDMUNDSON CONTRIBUTOR ELIZABETH DEE

Cover Image: Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Detail from Venice, the Doge’s Palace, 1881. Oil on canvas. Clark Art Institute, 1955.596

Fall 2025

A Casa Cipriani Production Printed in New York City

AYOUNG

there is a certain audacity in imagining the future—not as a singular, sleek inevitability, but as a messy, layered tangle of histories, emotions, and possibilities.

This is the terrain where Ayoung Kim thrives. The Seoulborn artist, newly announced as the 2025 recipient of the LG Guggenheim Award, works at the shimmering intersection of art and technology, crafting immersive universes that oscillate between the ancient and the speculative, the corporeal and the algorithmic.

The award, now in its third year, is part of the LG Guggenheim Art and Technology Initiative—a fiveyear program designed to research, honor, and promote artists whose practices engage directly with technological innovation. For Kim, it is both recognition and resonance. “Neither a techno-determinist nor a techno-pessimist,” she says, “I have always wanted to comment on the impact of technology in our society by using it.”

Kim’s work resists easy categorization. Trained in motion graphics and lens-based media, she moves fluidly between virtual reality, live simulation, performance, sculpture, and printmaking. Her digital landscapes—built from live action, motion capture, animation software, game engines, and image-generation tools—are fantastical yet grounded in research. They

might reference the ritual geometries of ancient cosmologies, the aesthetics of Webtoon storytelling, or the lived experience of service workers navigating algorithmic control. She approaches her subjects like both anthropologist and filmmaker, conducting fieldwork and documentary research before reimagining them as sprawling, speculative narratives. In these worlds, the granular and the cosmic coexist: quantum particles collide with myth; refugee journeys unfold in parallel with the migration of data across invisible networks.

This expansive method allows her to collapse time and geography, to weave together the past’s symbolic codes with visions of possible futures. The result is work that feels not just technologically accomplished, but emotionally and intellectually alert—a rare balance in an era when digital spectacle often overshadows depth. For Naomi Beckwith, Deputy Director and Chief Curator at the Guggenheim, this capacity for reflection is central: “By revealing the convergence of machines and humanity, her visionary work illuminates the most pressing challenges of our era.”

In its citation, the award jury described Kim’s work as a “paradigm shift” in the way art can engage with emerging technologies. By merging traditional cinemat-

ic tropes with new image-making techniques, she “redefines the role of an artist as a connector between social legacies, fostering new dialogues in art and technology.”

Kim’s interest lies less in technology as a novelty than as a mirror—a way of making visible the structures, biases, and aspirations embedded in the tools we create. Her projects often highlight the ethical and emotional dimensions of living under algorithmic governance, asking viewers to consider not only how technology shapes their perceptions, but also how it might reconfigure their relationships to time, place, and each other.

Her visual language can be both intimate and monumental. In one series, digital avatars navigate vast, otherworldly terrains—deserts that ripple like liquid metal, skies shot through with shifting constellations of code. In another, the focus narrows to gestures, conversations, and micro-expressions, revealing the texture of human life as it intersects with artificial systems. The fascination with the “boundary between humans and machines” is informed by a curiosity about physics and particle science, but also by a storyteller’s instinct. She treats technology not as a cold, rational apparatus, but as a stage where emotions and myths play out in new guises.

LG’s Head of Brand, Seol Park, framed it as a shared sensibility: “Ayoung Kim’s work, in which technology is both a subject matter and a medium, resonates with LG’s engagement with technology as

we advance innovations with considerations to human experiences and emotions.” That human element runs through Kim’s work, even at its most digitally intricate. However advanced the tools, her pieces are never simply feats of software—they are invitations to see ourselves refracted in unfamiliar light.

While her practice is rooted in digital tools, Kim’s career has unfolded across some of the world’s most influential cultural stages. Recent years have seen her work presented at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, ACMI in Melbourne, M+ in Hong Kong, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She has appeared at biennials from Venice to Sharjah, winning accolades including the Prix Ars Electronica’s Golden Nica Award and the ACC Future Prize. Her works are housed in major collections—Tate in London, Leeum Museum of Art in Seoul, National Museum of Art in Osaka—testament to the global relevance of her vision. A solo exhibition at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof, offered European audiences a new chance to step inside her layered, constructed realities.

If there is a unifying thread in Kim’s practice, it is connection: between old and new media, between disparate cultural narratives, between the tactile and the virtual. Her art does not simply document a world in flux—it proposes models for how to navigate it. This connective impulse feels particularly urgent in an age when technological change often deepens divides.

Kim’s speculative worlds invite viewers into spaces where those divides can be bridged, at least imaginatively. They encourage a literacy not just in the tools themselves, but in the ways they shape power, identity, and belonging.

As the award jury noted, her work “transcends conventional representations, portraying humanity as an evolving intersection of physicality and data.” In doing so, it opens space for contemplation and discovery—a rare gift in a time when both art and technology are often consumed in haste. The LG Guggenheim Award comes with an unrestricted $100,000 honorarium, but perhaps more importantly, it signals institutional recognition of the importance of artists working in this hybrid space. It affirms that the questions Kim raises—about ethics, emotion, and the multiple realities we inhabit—are as central to our cultural discourse as they are to our technological future. For Kim, the task ahead is to continue probing that uncertain terrain. “As technology advances, human life inevitably becomes more intricate,” she reflects. “What artists can do with technology is explore the uncertain possibilities it may conceal and deploy it in the most intuitive way.” Her work suggests that such exploration is not only possible, but necessary— that in imagining worlds beyond our own, we might better understand the one we are already shaping, line of code by line of code.

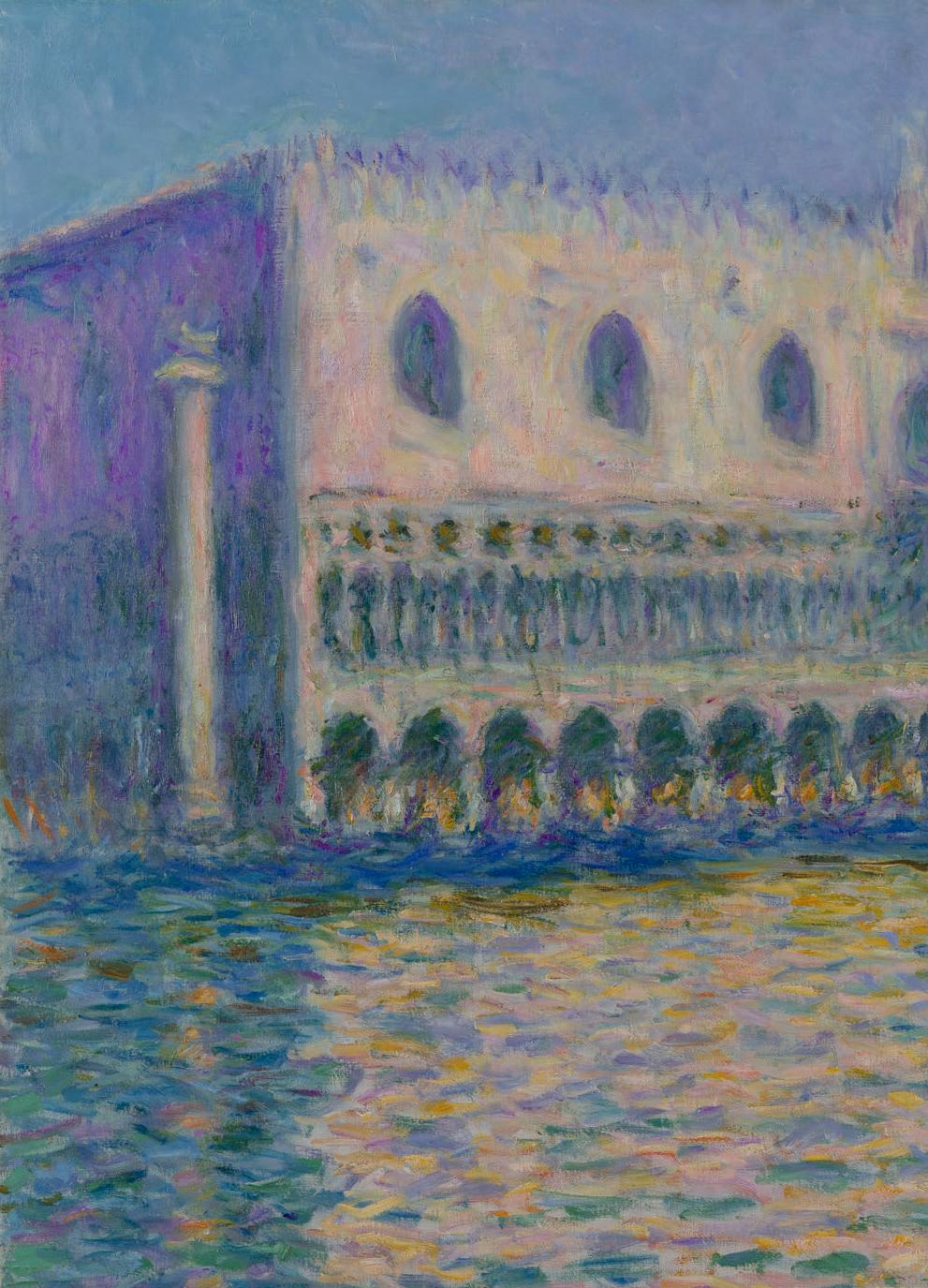

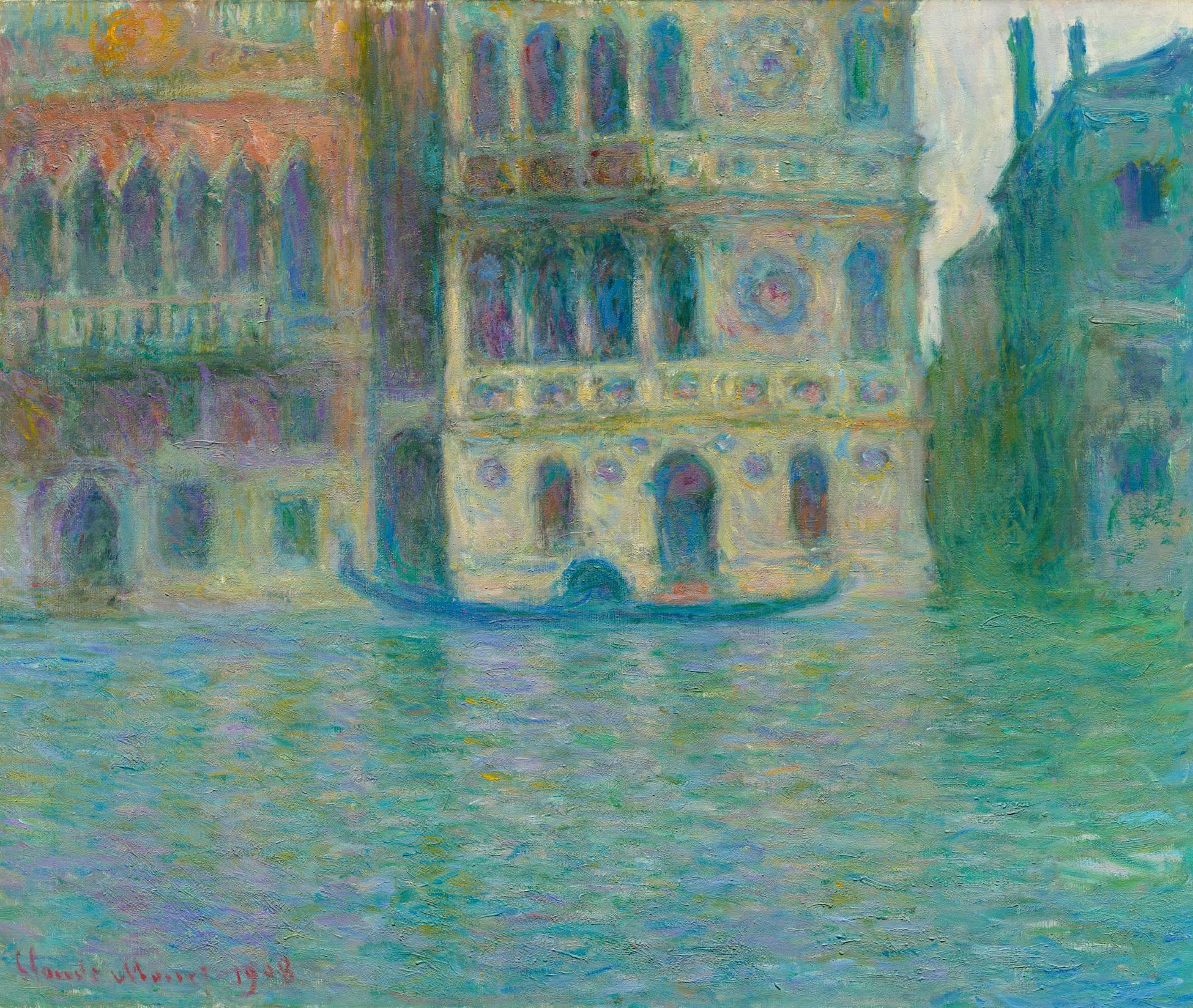

in october 1908 , Claude Monet—reluctant traveler, master of light, and chronicler of cities—stood on the edge of the Venetian lagoon, staring at a city he had once dismissed as “too beautiful to be painted.” Encouraged by his wife, Alice, who believed the journey might revive him during a crucial moment in his career, Monet had left the familiar gardens of Giverny for this improbable stage of canals, palaces, and shifting light. He arrived a tourist, wary of clichés, but departed with a suite of paintings that would become the last major works shown in his lifetime—his own prismatic Venice.

The Brooklyn Museum’s forthcoming exhibition Monet and Venice (October 11, 2025–February 1,

2026) will reunite nineteen of those luminous Venetian canvases for the first time in more than a century. More than one hundred works—paintings, watercolors, etchings, rare books, postcards, and photographs—will trace not only Monet’s time in the lagoon but also his lifelong fascination with water and reflection. It is the largest Monet exhibition New York has seen in fifteen years and, crucially, the first to place his Venice within the broader arc of his career and in conversation with artists who found their own truths in the city’s shifting atmosphere: Canaletto’s theatrical precision, Turner’s dissolving storms, Whistler’s tonal restraint, Sargent’s quicksilver watercolors, and Renoir’s luminous street scenes.

For Lisa Small, Senior Curator of European Art at the Brooklyn Museum, the exhibition’s organizing principle lies in what Monet called the enveloppe—the unified skin of light, water, and air that merges solid forms into transient impressions. “In his Venice paintings, magnificent churches and mysterious palaces dissolve in the shimmering atmosphere like floating apparitions,” Small says. “They are less depictions than acts of immersion.”

The Museum’s own Palazzo Ducale—acquired in 1920 in a strikingly early recognition of the value of modern French art—anchors the show. It sits alongside canvases of San Giorgio Maggiore, Palazzo Dario, and other facades rendered not as architectural elevations but as spectrums of light, their contours wavering in reflection. Complementing Monet’s dissolving façades are John Singer Sargent’s Venetian watercolors, including La Riva (1903–4) and Santa Maria della Salute (1904), where the American painter captured the flash of movement and glimmer of water with a swiftness that mirrors Monet’s own fascination with evanescence. Unlike the bustling markets and gondola-filled canals of Canaletto,

Monet’s Venice is largely empty of people. The human drama is implied, not enacted, as if the city itself is the protagonist.

Monet visited Venice only once. The trip was brief—two months—but transformative. The city, already wrestling with pollution and overtourism in 1908, offered him both a challenge and a reprieve. He worked from a small number of vantage points, returning again and again

to the same subjects at different hours, capturing how a shadow softened, how the stone blushed in the last light, how the lagoon mirrored the sky until both were indistinguishable.

Alice’s sudden death in 1911 prevented the couple’s planned return. In mourning, Monet retreated to his studio, where he completed the Venetian series. When they were exhibited in Paris in 1912, they were met with

acclaim. They would be the last new works the artist allowed to be shown before his death.

“To paint Venice is to paint the air and the light; the city itself is only the pretext.”

—Claude Monet

The Brooklyn presentation situates these canvases among earlier explorations of water—views of Normandy’s coast, the Thames in London, and the gardens of Giverny, including three water lily paintings on loan from the Musée Marmottan Monet, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and a private collection. Together, they form a kind of visual autobiography in reflections, charting Monet’s search for subjects in which the tangible and intangible coexist.

A distinctive feature of Monet and Venice is its embrace of the multisensory. The Museum’s Composer in Residence, Niles Luther, has created an original symphonic score inspired by the paintings. Luther’s composition, blending Italian, French, and American traditions, draws on field recordings made in Venice— footsteps over stone bridges, the lap of water against

moorings, distant bells—and melodic fragments that echo the rhythms of Monet’s brushwork. “I approached the paintings as souvenirs,” Luther says, “memories infused with both beauty and melancholy… transforming brushstrokes into living sound.”

Visitors will first encounter this soundscape in the Museum’s fifth-floor rotunda, within an immersive installation by Brooklyn-based design studio Potion, featuring film by Joan Porcel. Here, projected imagery and music re-create the enveloppe that so captivated Monet, preparing the eye and ear for the sequence of galleries that follow. In the final gallery, Luther’s full symphony plays alongside Monet’s most iconic Venetian works, creating a dialogue between pigment and tone, sight and sound.

Historical ephemera deepen the narrative. Guidebooks, postcards written by Alice to her daughter, and photographs—some on loan from Alice’s

great-grandson, Philippe Piguet—offer glimpses into the couple’s daily life in Venice, even marking their lodging on the Grand Canal. These artifacts remind us that the great works were born of ordinary moments: a letter posted, a walk taken, a view noted for its light.

By juxtaposing Monet’s Venice with works by contemporaries and predecessors, the exhibition underscores both his debt to and departure from tradition. Turner and Whistler found poetry in atmospheric dissolution, Sargent in the fluid immediacy of watercolor, Renoir in the bustle of life. Monet, however, distilled Venice into a meditation on endurance and ephemerality. His façades stand yet seem on the verge of disappearance, their permanence undone by the mutable play of light.

The show closes with an unexpected connection: archival murals depicting the re-creation of Venice at Coney Island’s Dreamland amusement park. It is a playful reminder that the idea of Venice—its romance, its light, its improbable beauty—has traveled far beyond the lagoon, finding new expressions and audiences across time and geography.

Anne Pasternak, the Museum’s Shelby White and Leon Levy Director, sees Monet and Venice as an invitation: “Through thoughtful interpretation and design, we invite our audiences to see Venice through Monet’s eyes and feel inspired by his vision.”

That vision, distilled in canvases painted more than a century ago, still speaks to the fragility of beauty, the impermanence of light, and the capacity of

art to arrest both for a moment. Monet’s Venice may be empty of gondoliers and passersby, but it is filled with the pulse of the city’s reflections—water meeting stone, sky dissolving into tide. It is a city at once timeless and fleeting, held in the precise instant before it changes forever.

For Monet, that was the point. His trip to Venice, he later reflected, “had the advantage of making me see my canvases with a better eye.” He returned to Giverny renewed, his water lilies now carrying some trace of the lagoon’s chromatic shimmer. For the rest of us, Monet and Venice offers the rare chance to stand where he stood—in front of the palaces and canals as he saw them—not as fixed monuments, but as living, dissolving apparitions in the light.

Few figures have shaped the global language of spectacle quite like Marco Balich. Over the past three decades, he has transformed stadiums, cityscapes, and historic sites into stages for awe—whether through the grandeur of Olympic Ceremonies, the poetry of cultural festivals, or the refinement of luxury fashion shows. His work exists at the intersection of storytelling and emotion, where scale meets intimacy and tradition converges with innovation. To Balich, the role of the director is not merely to orchestrate events, but to choreograph collective memory—crafting moments that remain etched in the imagination of millions.

bollettino: How much does psychology come into play when considering the designer must keep a massive live in-person audience entertained throughout while also balancing the needs of a television audience with its preference for small moments and intimate details?

marco balich: At the heart of our creative process lies the emotional journey of the audience, whether they’re in a stadium with 80,000 people or watching from home. Olympic Ceremonies have always been the most-watched show in the world—transcending social class, geography, and age—because they ignite a deep pride in one’s nation, while also evoking a profound sense of wonder for humanity and the highest values embodied by sport.

Simplicity in storytelling and perfection in every detail allow both the live and remote audience to feel a powerful sense of collective belonging. Balancing both dimensions demands not only exceptional design skills,

but also deep empathy: the ability to understand how people perceive, react, and remember.

In essence, we choreograph emotions. Every element—music, lighting, movement—is designed to resonate on multiple scales. The true magic happens when everyone—at home and in the stadium—feels part of something greater than themselves.

bollettino: Let’s talk about major luxury and fashion events. You’ve created experiences for iconic brands like Bvlgari, Dolce & Gabbana, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Buccellati. What is part of the process of bringing a fashion house’s vision to life?

mb: The key ingredients are the ability to interpret a brand’s identity through the language of entertainment, and to move people through beauty and flawless execution.

It’s about crafting a memorable experience that emotionally engages the audience. Luxury and fashion are not just about aesthetics or exclusivity—they convey identity through emotion and experience. Today, brands don’t just sell products; they direct emotions and embody values on a global stage.

bollettino: How do you approach traditional events like Festival of Santa Rosalia in Palermo, while utilizing new technology and innovations in the field?

mb: When we work on cultural or traditional events, our role begins with deep respect—respect for history, for the community, and for the emotional legacy that the event represents. Creativity without knowledge risks becoming superficial.

It’s not about rewriting tradition, but about illuminating it through a contemporary lens, allowing it to resonate with today’s audiences while honoring its original spirit. Our mission is to create a dialogue between past and present, sacred and spectacular— always guided by meaning, never just by effect.

bollettino: Your work blends emotion, aesthetics, and storytelling, are there any films or directors that have influenced your work?

mb: Absolutely. Cinema and visual arts have always had a strong influence on our creative process—we pay close attention to both.

For example, when we staged the launch of the Fiat 500 in 2007 on the river in Turin, the central scene was inspired by a French film called Les Amants du PontNeuf. There’s a beautiful sequence with fireworks over the river, which we reinterpreted by designing a 700-meter-long fireworks installation along the water.

I’ve also drawn inspiration from directors like Wes Anderson—especially his costumes, which are always meticulously curated and full of character. That kind of visual precision has influenced several of the ceremonies we’ve created.

vermeer’s paintings have always carried an air of secrecy. His interiors, bathed in light that seems to pause time, invite us to look—and to wonder what lies beyond the frame. We never quite know the full story; we only sense that it is there, just out of reach. In the Frick’s recent exhibition of letters depicted in Vermeer’s work, that quiet enigma is refracted into something more tangible: a glimpse into the intimate act of reading and writing, and into the inner life of someone deeply invested in every word and its implications.

The show gathered several of his most celebrated depictions of women with letters—works where narrative exists not in grand gestures but in the smallest cues: a gaze fixed on a page, a hand resting mid-sentence, the faint

suggestion of lips moving in silent reading. “Vermeer’s genius,” as one scholar notes, “is to suggest that meaning lies as much in what is withheld as in what is revealed.”

What these scenes capture is not the content of the letters themselves—we will never read them—but the weight they clearly hold for their recipients. Each phrase, each turn of language, carries the potential to alter the course of a day, or a life. In the 17th century, letters were lifelines, slow-moving vessels of emotion and information. To receive one was to enter into an unspoken pact with the sender: to read closely, to interpret faithfully, to answer in kind.

It is, in many ways, not so different from the way we treat a direct message today. Friends will pass a

phone around, analyzing the choice between “hi” and “hey,” debating the significance of a period versus no punctuation at all. Every word is mined for tone and subtext. Vermeer’s women seem to be engaged in the same work, eyes scanning for clues, posture revealing a mind in motion.

The Frick’s rooms are hushed, but alive with this unspoken drama. Here, intimacy is not performed but inhabited, captured at the moment when the outside world falls away and the only reality is the page in hand. Across centuries, we recognize the impulse: to lean into language, to find ourselves in it, and to wonder what the writer truly meant. In Vermeer’s world, as in ours, the smallest turn of phrase can contain entire worlds.

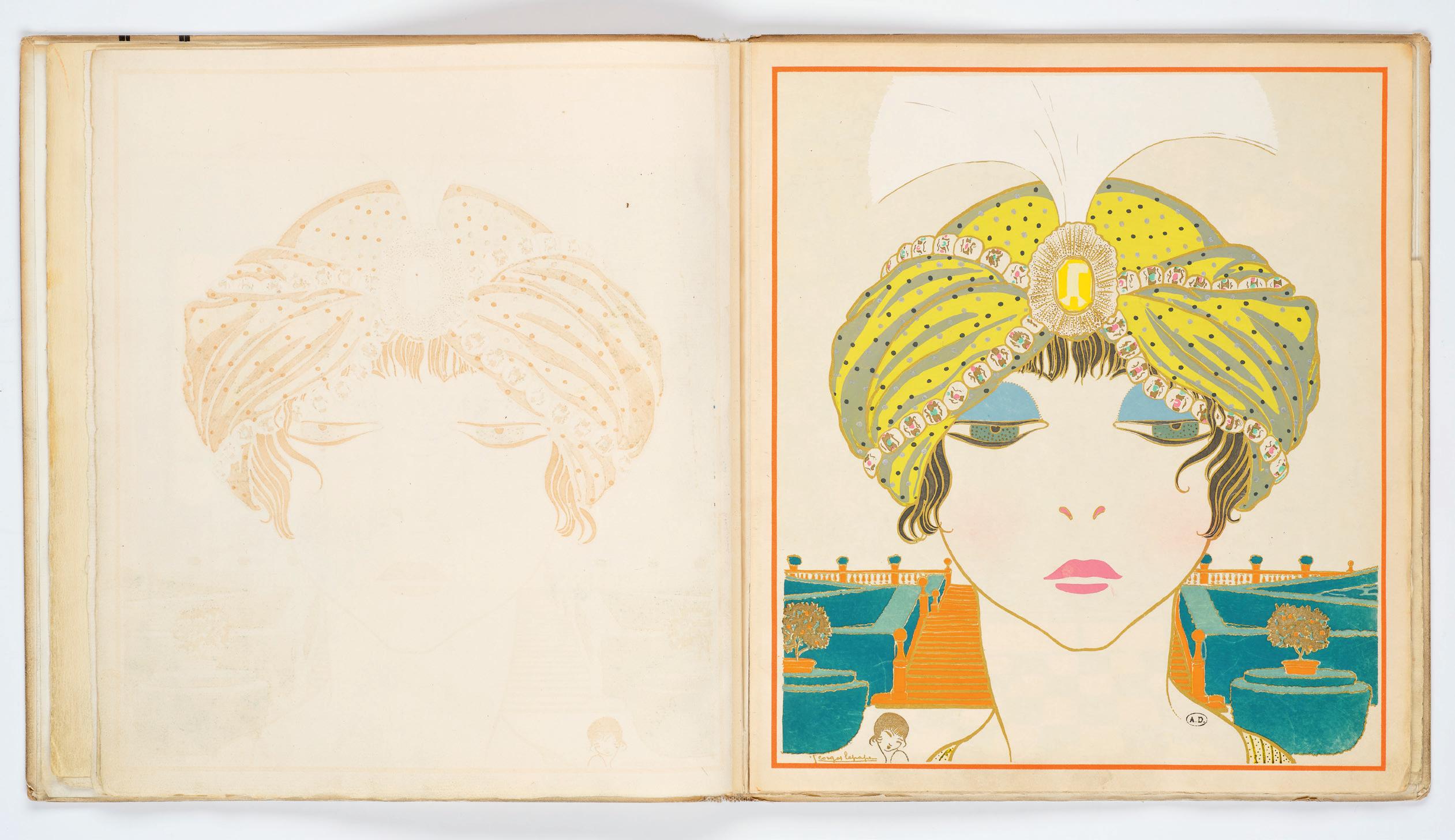

FROM CORSETS TO SPECTACLE, PAUL POIRET ’S LEGACY LIES NOT JUST IN GOWNS BUT IN IMAGINING FASHION AS CULTURAL THEATER.

poiret has always occupied an uneasy position in the history of fashion: a pioneer credited with liberating women from the tyranny of the corset, but also an impresario who staged their bodies within elaborate fantasies of the “Orient.” Hailed in his lifetime as the “King of Fashion,” he expanded couture into a kind of total art, blending dress with fragrance, interiors, and performance, yet his empire collapsed in less than two decades. To look back at his work is therefore to confront paradox. It is not only about the shimmer of silk and the daring of silhouette, but about a moment when modern fashion was being invented—conceptually as much as materially— and the contradictions that would continue to shape the industry. ➺

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris has taken up this task with Paul Poiret: Fashion Is a Feast, a sweeping exhibition on view through January 11, 2026. More than 500 objects—gowns, accessories, drawings, perfumes, and decorative pieces—are gathered here to place Poiret within the full cultural and social matrix of the early twentieth century. The show resists a nostalgic celebration and instead offers a reframing: an exploration of how his ideas of spectacle, branding, and atmosphere anticipate the immersive strategies of fashion today.

At the heart of Poiret’s early innovation was a simple but radical gesture: to free women from corsetry. His chemise dresses, tunics, and so-called lampshade gowns allowed for unprecedented fluidity of movement, shifting the silhouette from rigid sculpture to kinetic form. Liberation, however, was never presented plainly. Poiret staged it as theater. His wife Denise, often his muse and mannequin, famously appeared at the Thou-

sand and Second Night ball in 1911 dressed in a harem costume, surrounded by tents and lanterns designed to evoke Persia. For contemporaries, it was dazzling. For us, it is revealing. The moment crystallizes both the progressive rejection of restriction and the reliance on exoticist fantasy that would become his hallmark.

Poiret understood himself less as a tailor than as a conductor of worlds. He was among the first to grasp that fashion could extend beyond the garment into every register of life. In 1911 he launched Parfums de Rosine, named for his daughter, creating one of the earliest couturier perfumes and signaling that scent could function as a brand extension. Soon after, he opened Ateliers de Martine, a decorative arts studio where young women designed furniture, textiles, and objects aligned with his aesthetic vision. What he offered was not simply clothing, but a universe—a total environment that anticipated what the modern fashion house would become.

Yet history is never still. The exuberance of his silks and theatrically draped fabrics belonged to the optimism of the pre-war years. After 1918, the world demanded something different. Women sought practicality, speed, and autonomy, qualities embodied in Chanel’s austere jersey suits. Poiret, once the symbol of avant-garde, suddenly appeared stranded in a vanished era. His empire went bankrupt in 1929. By the time of his death in 1944, he was largely forgotten—an astonishing descent for a man once seen as fashion’s sovereign. The brilliance of this exhibition lies in its ability to move past both the myth of his genius and the narrative of his failure, suggesting instead that his greatest legacy was conceptual. In its layering of garments with sketches, photography, and decorative works, the show positions Poiret as a designer of atmospheres, one who grasped the power of spectacle and understood fashion’s potential as a cultural system. His insight—that clothing

could be inseparable from image, environment, and desire—feels strikingly contemporary.

Walking through the exhibition is to encounter the paradox of Poiret made physical. Rooms are staged in saturated colors, echoing the theater of his soirées, but visitors are also invited to consider the cultural politics of what they are seeing. The Orientalist motifs that thrilled Belle Époque audiences reveal the uneven cultural exchanges through which Western modernity defined itself. To admire the lavish embroidery is also to reflect on the structures of fantasy and appropriation that underpinned it. The show is at once immersive and critical, a double stance that mirrors the complexity of its subject. What lingers, after this gathering of more than five hundred artifacts, is not nostalgia for a gilded age but an awareness of fashion’s enduring contradictions. It

is always poised between freedom and control, fantasy and pragmatism, the fleeting and the permanent. Poiret grasped these tensions, even if he could not always master them. His downfall was not a failure of imagination but of adaptation; his genius lay in intuiting how fashion could operate as a total cultural language.

In this sense, the exhibition feels less like a rehabilitation than an echo. To see Poiret today is to recognize how thoroughly his strategies—spectacle as marketing, lifestyle as brand, immersion as desire—have become part of fashion’s DNA. If his career ended in obscurity, his ideas endure, woven into the fabric of contemporary design and its ceaseless pursuit of image and identity. Fashion Is a Feast restores him not only as a couturier of brilliance, but as a thinker who staged life itself as theater, and in doing so, glimpsed what fashion could become.

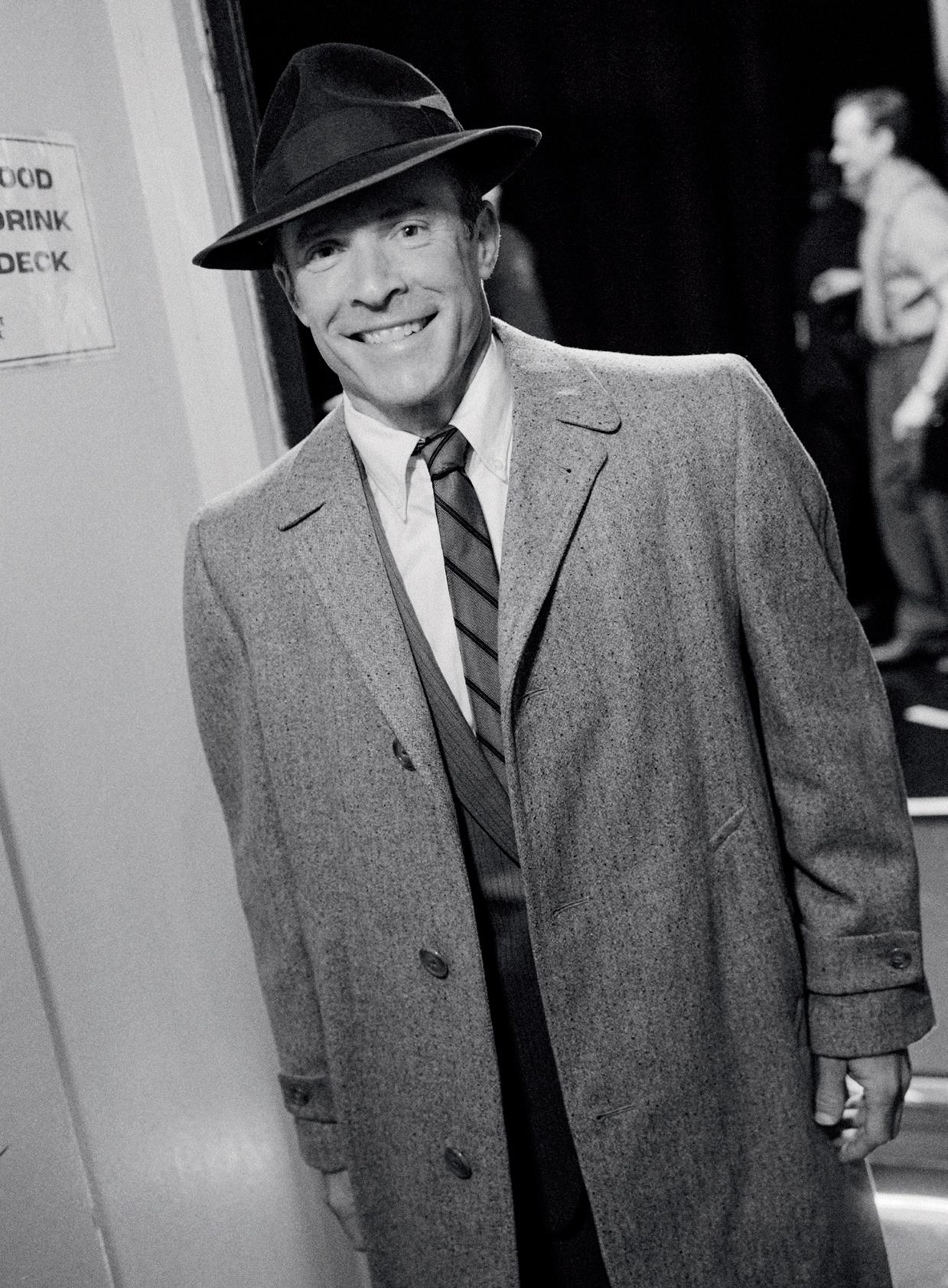

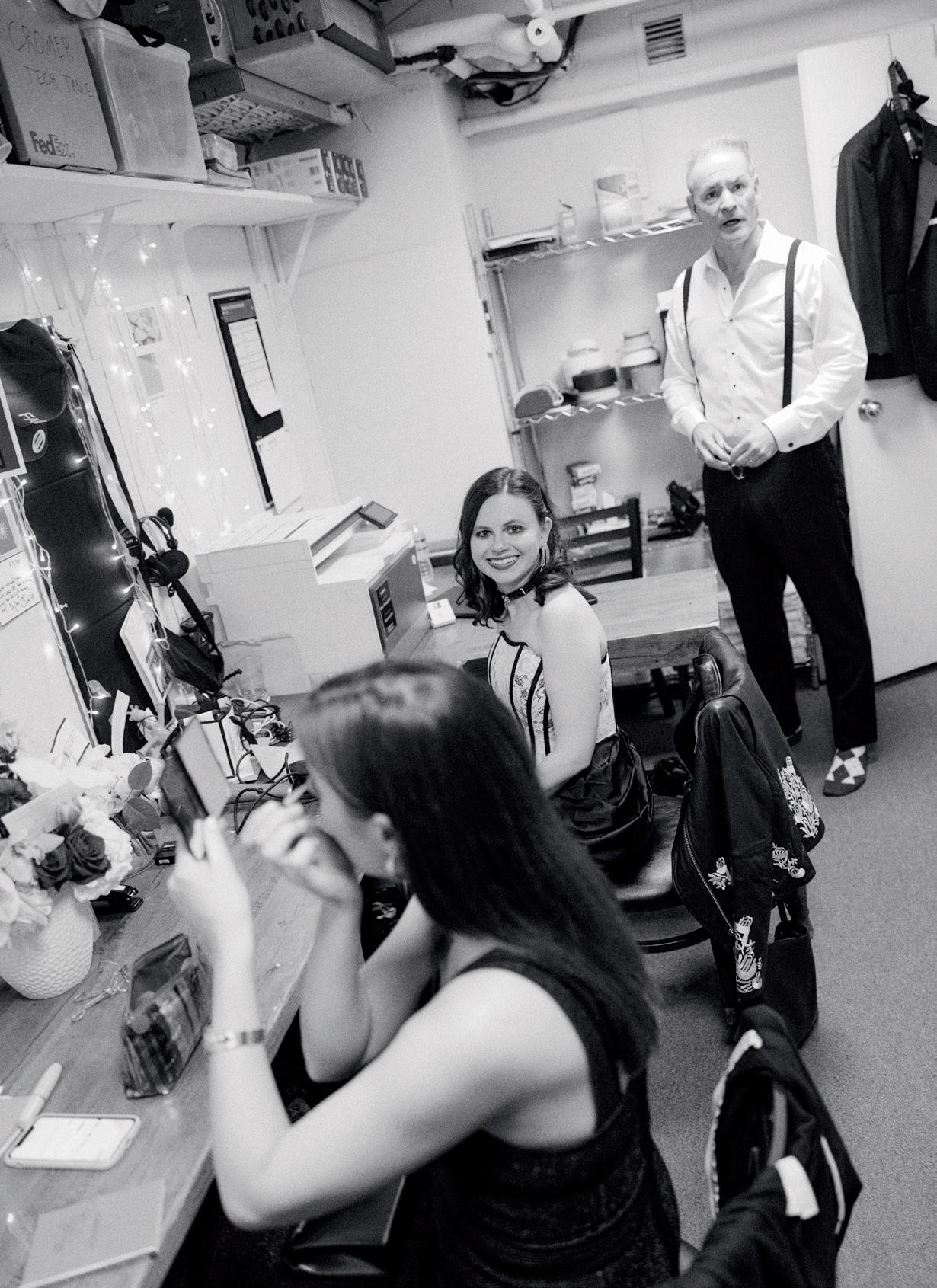

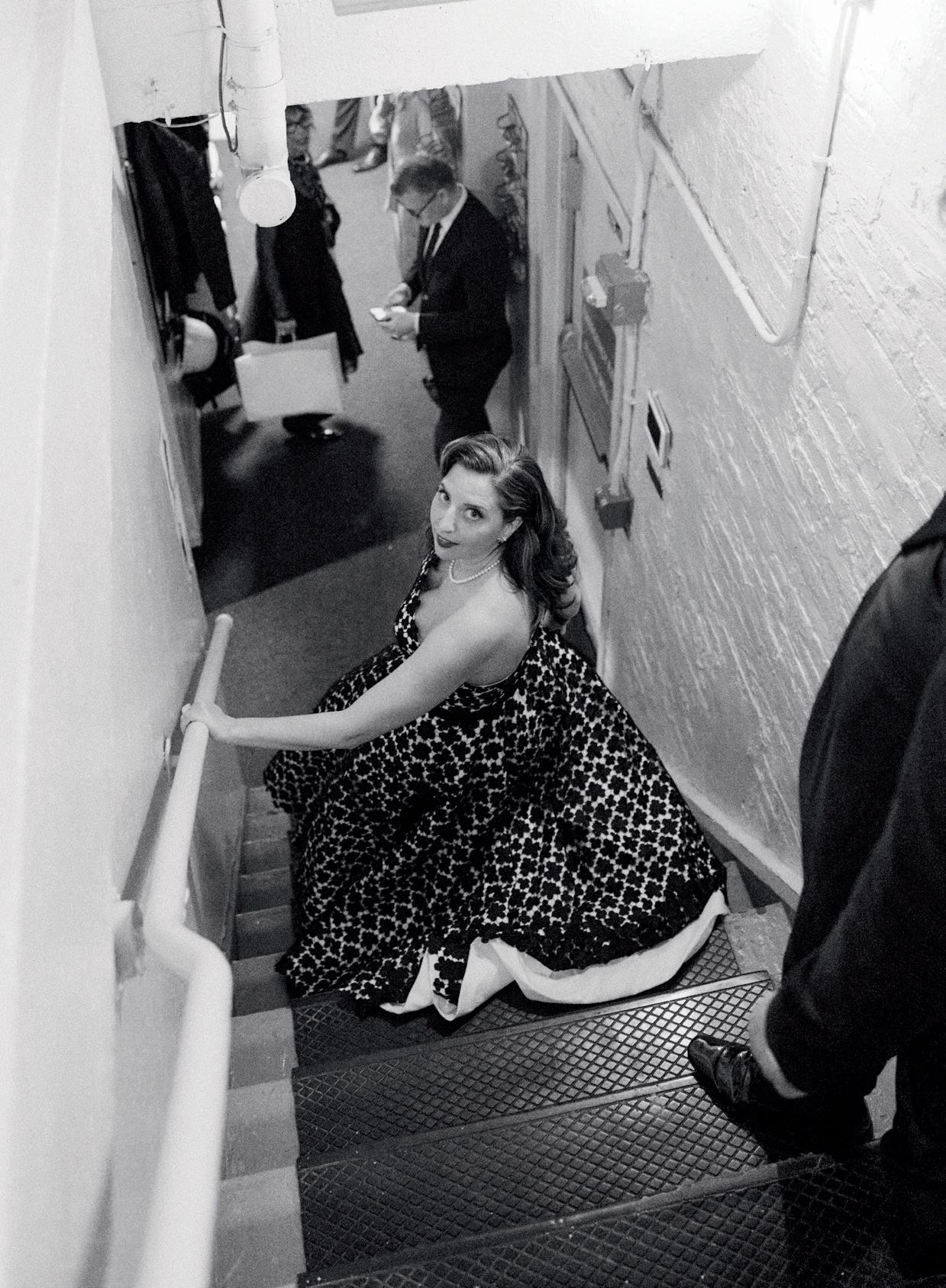

On opening night of Good Night, and Good Luck on Broadway, Emilio Madrid’s lens caught the electricity of a moment steeped in both glamour and anticipation. The evening began on the red carpet, where George Clooney—making his Broadway debut—greeted a swell of photographers and well-wishers. Noted guests filtered through, their arrivals a steady rhythm of flashbulbs and warm embraces, the theatre’s entrance transformed into a small constellation of familiar faces.

Madrid’s backstage images pull the viewer past the velvet curtain, into the hum of pre-show preparations: quick conversations in the wings, last-minute adjustments to costumes, a quiet moment of focus before stepping into the light. The curtain call came with a wave of applause that felt like release.

The night’s arc found its epilogue at Casa Cipriani, where the cast gathered to read the first reviews as they appeared—huddled over phones, grinning at each headline. The afterparty unfolded in that rare blend of relief and celebration, champagne glasses raised to a debut met with warmth and acclaim. Madrid’s photographs capture not only the event but the unguarded moments in between—an unfolding narrative of a production stepping confidently into the public eye.

THE VISIONARY DIRECTOR’S DREAM PROJECT COMES TO LIFE

“Whether you call someone a hero or a monster is all relative to where the focus of your consciousness may be,” —Joseph Campbell

across cultures far and wide, “monsters” emerge from the same impulse: to give form to what is most ungovernable in ourselves. They are the fears we repress, the desires we can’t name, the griefs we are unable to contain. Guillermo del Toro has spent his career working within this amorphous space, using monsters as both mirrors and oracles. They are, for him, never simply grotesques or antagonists, but beings through which the full spectrum of human emotion can be refracted—fear, beauty, and the impossible ache of love.

From the faun’s labyrinthine riddles to the amphibian god of The Shape of Water, del Toro’s creatures embody what he calls “the patron saints of imperfection.” They are outsiders not because they are unnatural, but because they reveal—too nakedly—truths most would prefer to remain hidden. His films resist the easy binary of monster and victim, instead drawing us toward a more dangerous empathy. The Shape of Water was, in his own words, “a love story disguised as a monster movie,” and that disguise was as much for the audience as for the world within the film. The creature’s difference, rendered in sensual detail, becomes not a barrier to intimacy but its precondition, an opening through which the human characters—and we—are invited to see beauty where we are conditioned to expect revulsion.

It is this same philosophy that now shapes his long-anticipated Frankenstein, due for release in late 2025. Del Toro has pursued the project for decades, regarding Mary Shelley’s novel not simply as a cornerstone of Gothic literature but as one of the most profound meditations on creation, alienation, and the responsibility that binds them. The film will not, he insists, be horror in the conventional sense. Like much of his work, it will center on the human core within the fantastical frame—the relationship between creator and creation, and the longing for recognition that passes between them like a current.

Shelley’s novel has always been as much about perception as about science. The creature is monstrous not by virtue of his design, but because no one, not even his maker, will claim him. Campbell’s observation hovers here: in another telling, perhaps in another century, Frankenstein’s creation could be a hero. But Shelley wrote him into a world that recoils from his face before

hearing his voice. That tragedy—the refusal to see beyond appearance—is one del Toro has returned to in countless guises. It runs through the insectoid horrors of Mimic, the spectral orphans of The Devil’s Backbone, the crimson-stained halls of Crimson Peak. Again and again, his monsters plead, in ways both explicit and unspoken: do you see me?

In Frankenstein, Jacob Elordi takes on the role of the creature, a casting choice that suggests del Toro’s interest in physicality as a narrative tool. Elordi’s height and presence make the character’s isolation more pronounced—he will stand apart not only in visage but in stature, his body as much a symbol of disconnection as his stitched skin. Opposite him, Oscar Isaac’s Victor Frankenstein embodies a different sort of estrangement: a man alienated from his own act of creation, incapable of reconciling ambition with responsibility. The dynamic between them promises to be as much about silence as about speech, about the unsaid and the unacknowledged.

Del Toro has spoken often about his attraction to what he calls “the living other”—beings who resist assimilation into human norms and whose very existence challenges the boundaries we draw between self and other. In Frankenstein, that idea converges with Shelley’s original storm-born vision, written in a moment of youthful audacity and intellectual ferment. She could not have known, as she sat through those nights at Villa Diodati, that she was conjuring one of literature’s most enduring figures. Yet the themes she set in motion—creation and abandonment, the hunger for belonging, the terror of the unfamiliar—would prove endlessly adaptable, able to slip between eras and sensibilities without losing their force.

If Shelley gave the monster life, del Toro seeks to give him soul, to place him within the lineage of creatures who are neither wholly villain nor victim but something messier and more human. He has often argued that fear is “the most intimate emotion,” because it bypasses

reason and forces us to confront what we most resist. But in his work, fear is rarely an endpoint; it is a threshold, one that opens onto beauty, tenderness, and, in some cases, love. This was true of the mute cleaning woman and her amphibian lover in The Shape of Water, and it seems poised to be true again in Frankenstein, where the question is not simply whether the creature will be feared or destroyed, but whether he can be truly seen. Monsters endure because they are not fixed; they shift with the gaze, with the age, with the need of the culture imagining them. They are, as Campbell suggested, heroes from another point of view. In this light, del Toro’s Frankenstein is not a resurrection of a familiar tale so much as a continuation of an ancient conversation— one that began long before Shelley’s pen touched paper, and that will, in some form, outlast us all. It is the conversation about what we choose to call monstrous, and whether, in the act of naming, we are revealing less about the creature than about ourselves.

LONDON EXHIBITION REUNITES AT THE CAFÉ AND CORNER OF A CAFÉ-CONCERT, SPLIT BY THE ARTIST’S OWN HAND.

the room is thick with cigarette smoke and the warm buzz of conversation. Glasses clink, chairs scrape across the floor, and on a small stage in the background, a singer leans into her song. A man in a top hat gazes off to the side, distracted; a dancer sweeps across the floor in a blur of satin and movement. It’s Paris in the late 1870s, and Édouard Manet is watching it all—absorbing the mingled glamour and restlessness of the café-concert.

This was Reichshoffen, the brasserie that inspired one of Manet’s most ambitious depictions of modern life. But the canvas he painted, stretching across the bustle of the room, doesn’t exist anymore—not in one piece. Sometime after completing it, Manet took a knife to his work, slicing the scene into two. What remained were At the Café (1878) and Corner of a Café-Concert (1878–80)—two self-contained worlds born from the

same moment, their connection severed yet still visible in the details.

On May 30, 2025, these estranged halves met again at the National Gallery in London. Corner of a Café-Concert, part of the museum’s collection since 1924, is hanging beside At the Café, on rare loan from the Oskar Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz” in Switzerland. It is their first reunion in Britain, and their first anywhere since a 2005–06 exhibition in Winterthur. For the occasion, they’ve been given custom frames that reveal the frayed edges of the canvases, the very scars of their separation.

Manet’s split wasn’t an act of destruction so much as reinvention. In the left-hand panel, At the Café, he added a luminous window and gave space to a solitary figure whose inward gaze contrasts with the

bustle around him. In the right-hand panel, Corner of a Café-Concert, he sharpened the energy with a dancer mid-step, backed by an orchestra in motion. The overall composition dissolved, but each fragment gained its own focus, its own atmosphere.

Why he did it is still debated. Perhaps he was dissatisfied with the whole; perhaps he saw two stronger works waiting within it. The Paris art market at the time often favored more intimate pieces over sprawling interiors, and Manet—though avant-garde—was also practical. Whatever the reason, his decision ensured the works would live separate lives.

Their journeys after the cut could hardly have been more different. Corner of a Café-Concert joined the National Gallery in the same year as Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, quickly becoming a centerpiece of its Impressionist

holdings. At the Café proved elusive; Reinhart, a Swiss collector with a taste for the rare, pursued it for thirty years before finally acquiring it in 1953.

Seeing them together now is less about reconstructing Reichshoffen than about sensing the tension between them. Stand in front of both and you can trace the faint echo of a beer glass from one frame to the other, the back of a chair that almost—but not quite—aligns. You’re aware of both the break and the bond, of the way Manet’s gaze could shift from the sweep of a crowd to the tilt of a single head.

In this fleeting reunion, the two paintings speak to each other across time and space, much as they must have in the studio before the knife fell. They remind us that Manet’s modern life was never static—it was cropped, reframed, and in constant motion, just like the city itself.

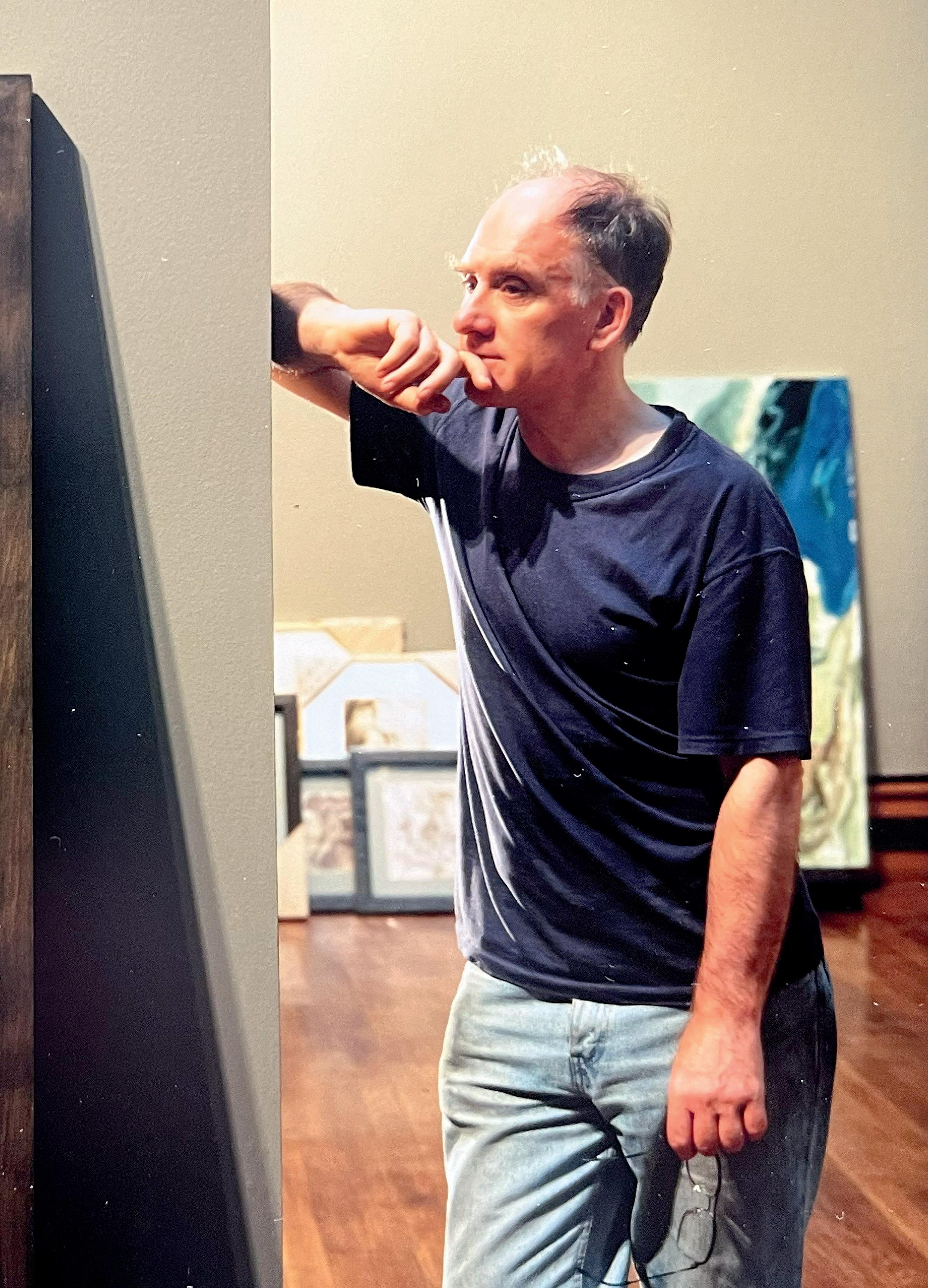

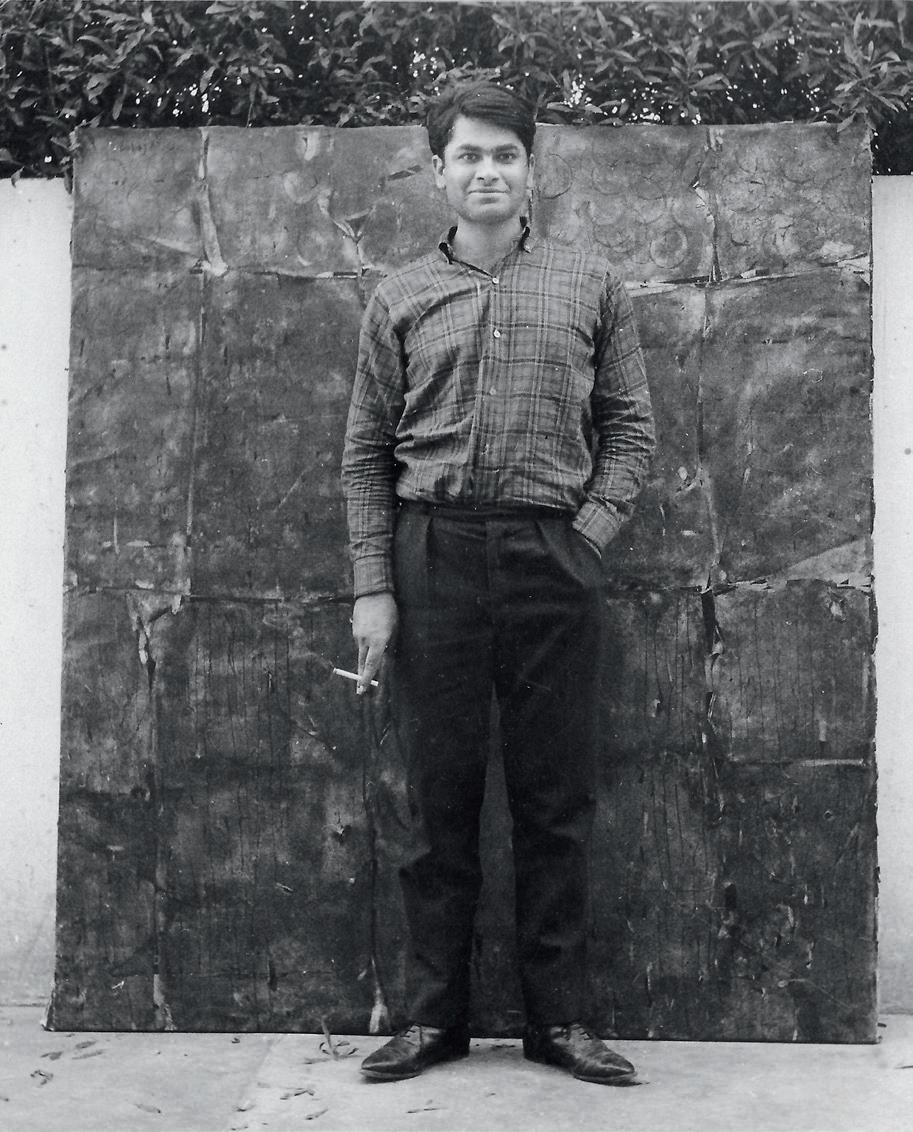

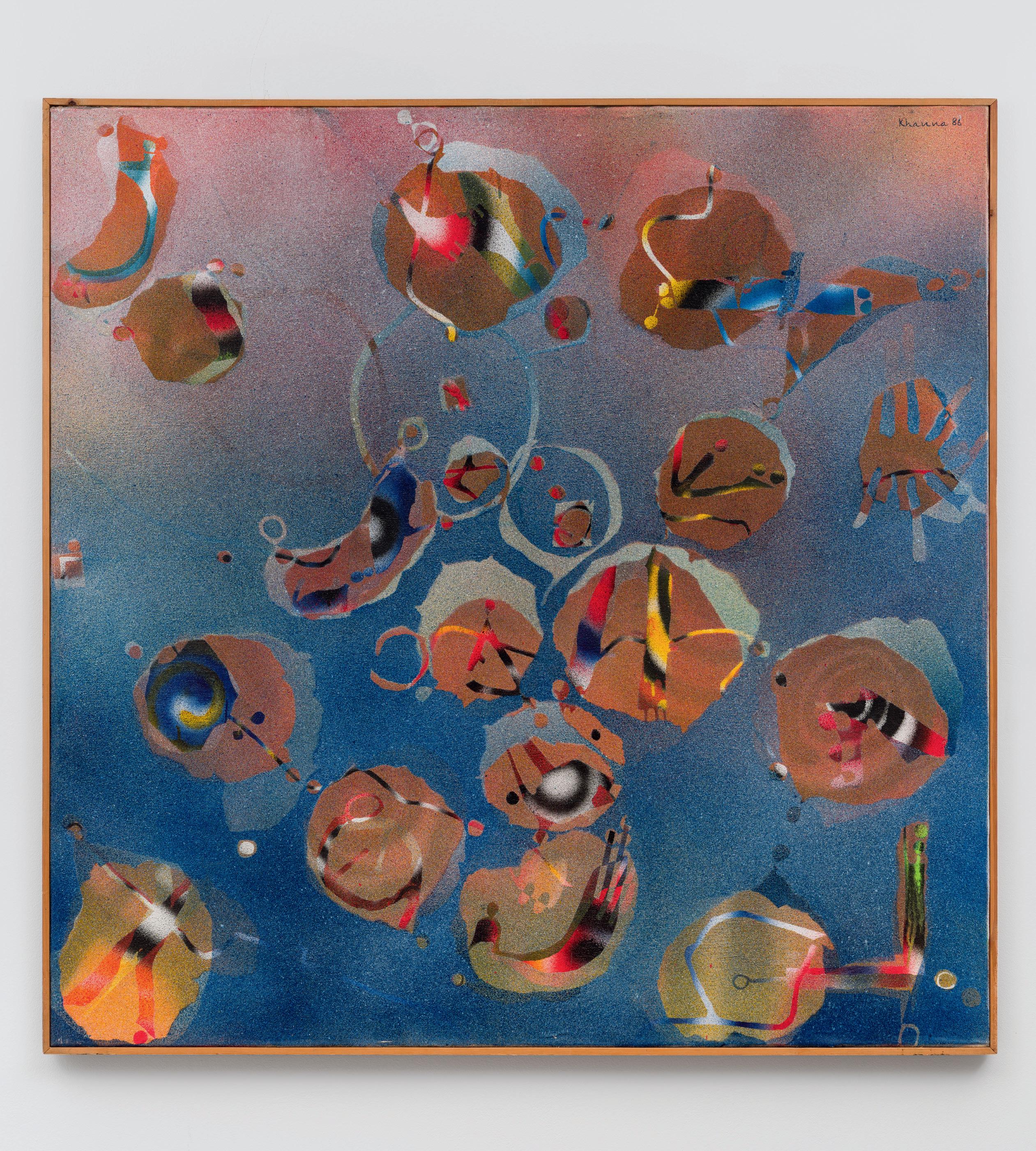

On a mission to redraw the map of modern art, Independent 20th Century returns this fall to Casa Cipriani in Manhattan’s storied Battery Maritime Building. The fair’s fourth edition unites 31 galleries from across the globe in a heady mix of sculpture, self-taught visionaries, and avant-garde voices from Latin America to the Middle East. In this special collaboration, we trace the lives and legacies of five artists stepping into New York’s spotlight—from the experimental abstractions of Balraj Khanna to the controlled chaos of Judy Pfaff’s upstate studio.

JHAVERI CONTEMPORARY

BY AIMEE DAWSON

the late balraj khanna (1939-2024) distilled his extraordinary life story into a simple title for his 2021 autobiography: Born in India, Made in England. But this one-liner belies the breadth of six decades of work by a figure who was not only an artist but also an award-winning writer of both fiction and non-fiction, a curator, and a gallery founder.

“He was a relentlessly active person, whether in his writing or his painting,” says his daughter Kaushalia, who has followed in her father’s creative footsteps, working as an architect and designer before recently completing a master’s in painting at the Royal College of Art in London. “He had the faith of being ‘the artist’. He would wake up and know that he had to work—and that work would account for his existence on Earth.”

Born in the Punjab region of India, Khanna moved to the UK in 1962 intending to study English literature, but instead fell in love with drawing and painting. In London he found a community of artists, including compatriots F.N. Souza (1924-2002) and Avinash Chandra (1931-91), and by 1964 he had joined the Indian Painters Collective, which advocated for the rep-

resentation of Indian artists in Britain. Labeled as “Commonwealth” artists, Khanna and his friends experienced a great deal of racism from British society and fought for opportunities to exhibit their work.

A transformative moment in Khanna’s early career came in 1965 while he was recovering from a motorcycle accident at his wife Francine’s family home in Metz, France. The sense of safety and comfort he felt there allowed him to experiment with his style, and he found a deep connection with nature in the nearby forest. From then on, Khanna focused on expressing what he called “the theatre of the natural world,” a phrase which titled a recent special display of his work at Tate Britain in London. Three of the paintings on view—Autumn Forest (1965), Saffron Field (1967), and Out of the Blue (2) (1987)—were acquired by the museum in 2024.

Foregrounding color and form, Khanna’s unique abstract paintings also drew heavily on his experiences of Indian and British culture. “He merged his imagination in the two realms [of England and India] to create a third space,” Kaushalia says. Sometimes the forms in his paintings approach figuration—evoking

kites from childhood memories or the leaves of British trees—and at other times they resemble the kind of cellular structures one might observe under a microscope.

Khanna had his first solo show at the New Vision Centre in London in 1965, and went on to exhibit widely in the UK, France, and India. He also ventured over the pond in the 1970s. Without a gallery in New York, he optimistically brought several canvases rolled up in his suitcase, including the monumental work Festival (1970). His hosts in Manhattan helped him secure an introduction to the Herbert Benevy Gallery, where he held two exhibitions in 1971 and 1972.

Jhaveri Contemporary’s upcoming presentation at Independent 20th Century will bring Khanna’s work back to New York for the first time in more than 50 years. The selection of three later paintings, dating from 1986 and 1999, is united by a common theme: ponds. “His interest in ponds and lakes probably stemmed from his passion for the Romantic English poets,” muses Kaushalia. “It’s like he wanted to feel close to them in some way.” John Keats lived near Hampstead Heath, with its famous ponds, and often wrote of its beauty. Khanna

frequented the north London neighborhood, undertaking the mosaic decoration of a private swimming pool there. He also took many trips to the Lake District landscapes favored by poets such as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and John Ruskin.

Khanna developed new approaches to materials from the mid-1980s, moving from oil paint to acrylic. He blew paint through handmade cut-outs overlaid on the canvas, creating diffuse layers of color and “infusing his own energy—his breath—into the painting,” as Kaushalia puts it. The technique lent itself well to depicting the movements and reflections of water. Khanna also applied sand to the canvas surface to add depth and texture.

The pond compositions share a more subtle tonality than is typical of the artist’s vibrant color palette. “They feel a bit like Impressionist paintings,” says Amrita Jhaveri, the founder of Jhaveri Contemporary. She describes the 1980s as the period that Khanna found his voice and a new-found prominence. In 1989 he participated in The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain , the landmark survey exhibition curated by artist Rasheed Araeen at the Hayward Gal-

lery, conceived as a response to the “racism, inequality, and ignorance of other cultures” still pervasive in the UK at the time.

Kaushalia, her mother Francine, and Jhaveri are currently sifting through Khanna’s studio, which holds hundreds of works, including paintings, drawings, and sculptures, along with a rich archive of letters, diaries, and other documentation. “He never threw anything away,” laughs Francine. Days earlier, she had stumbled across a rolled-up canvas—a forgotten portrait that Khanna had painted of her in 1963. Jhaveri Contemporary and the Estate are also preparing to publish a new book surveying Khanna’s oeuvre, following a recent study day with art historians and curators at Tate Britain.

“Working on the archive, organising the works by decade and finding where they were exhibited, I can definitely see Khanna’s progression, evolution, and experimentation—it was relentless!” Kaushalia says. “He never stopped looking at different things all the time. And that’s what makes the work always exciting.”

Aimee Dawson is a freelance art writer and editor. Her writing has appeared in Apollo, Artnet News, Artsy, V&A Magazine and Cultured, among others, and she was a contributing writer to the book African Artists (Phaidon, 2022). She is a columnist at The Art Newspaper, where she was formerly an editor, and a guest lecturer at SOAS, University of London.

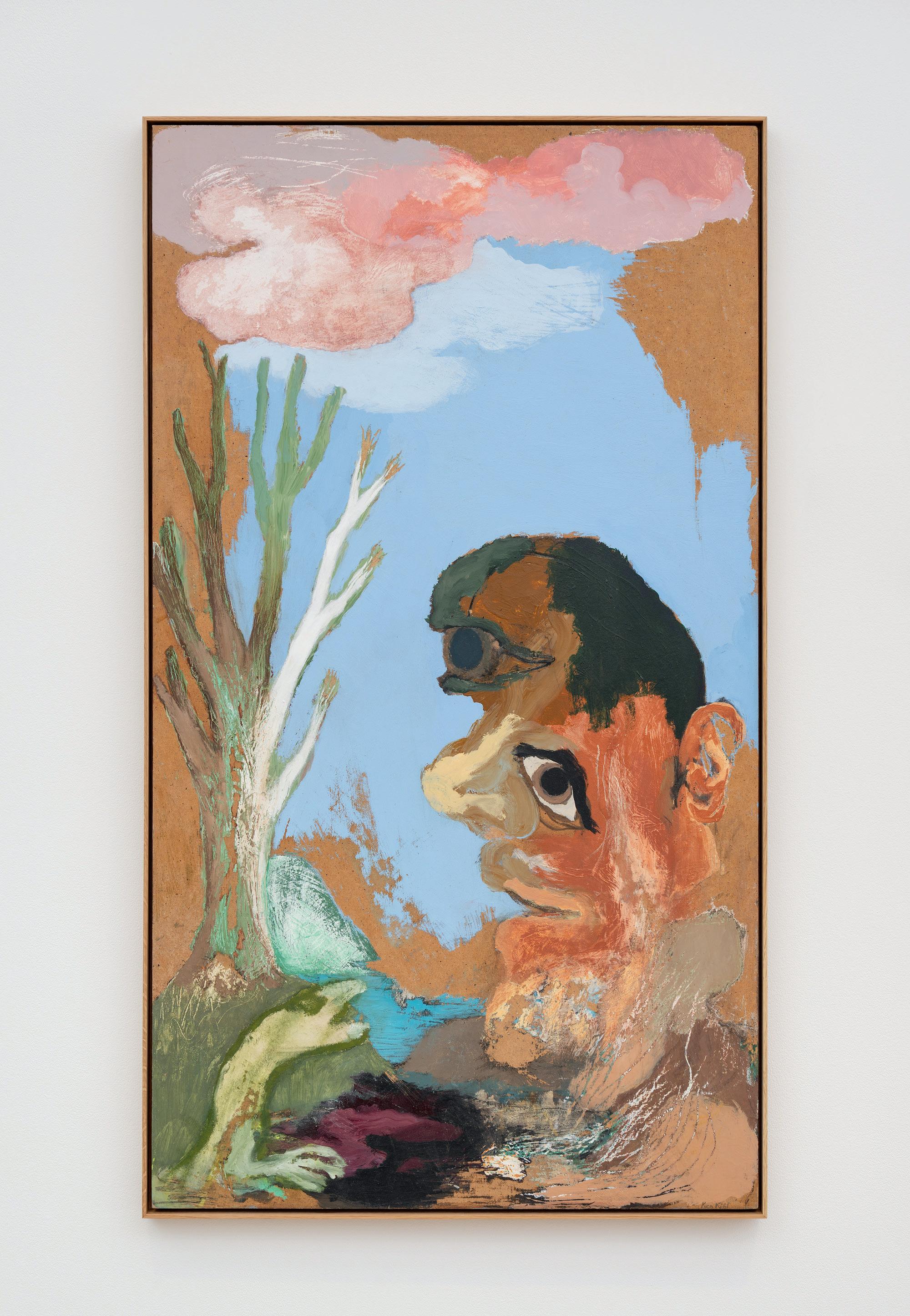

HALES GALLERY

BY EMMA M. HILL

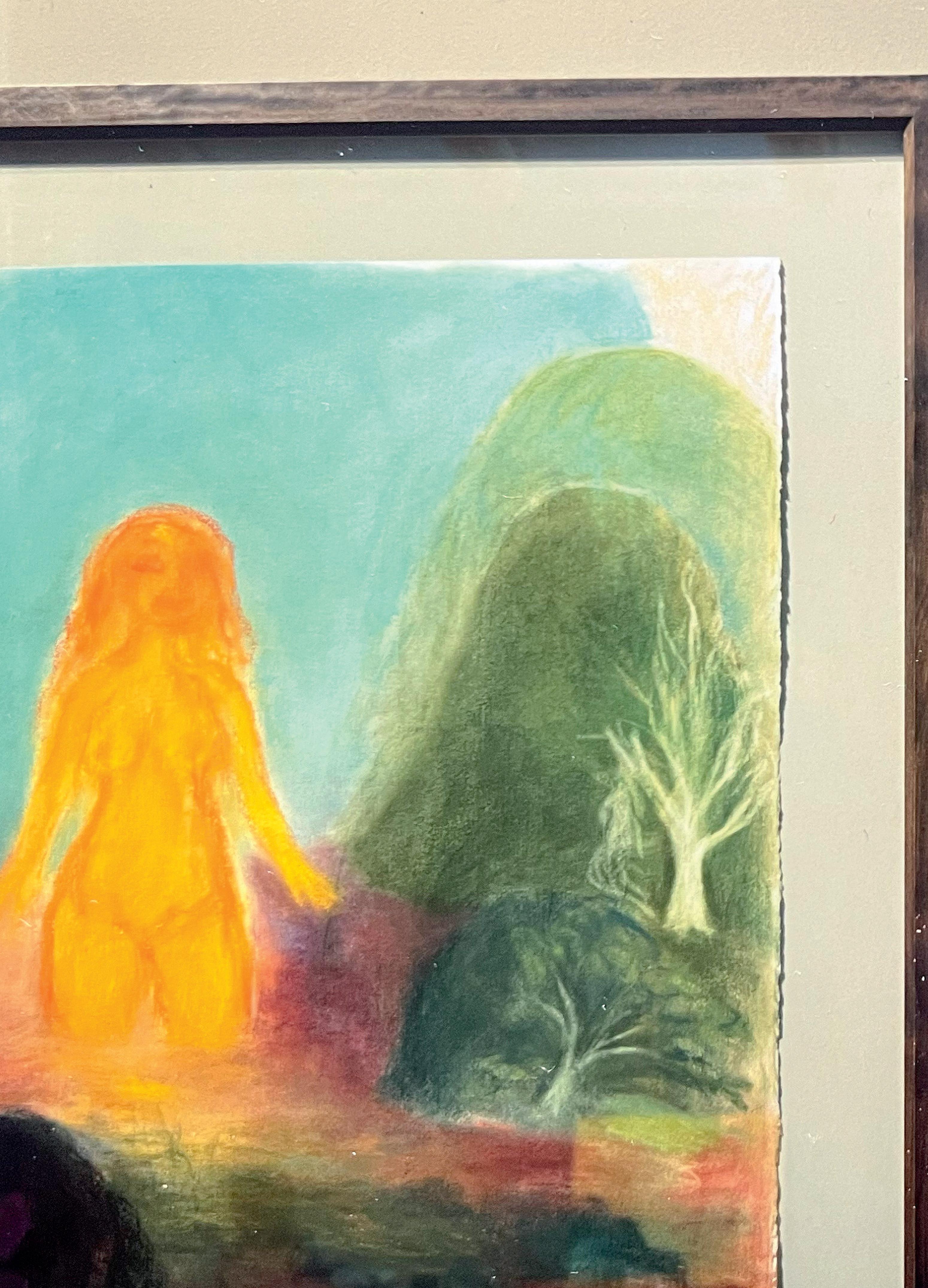

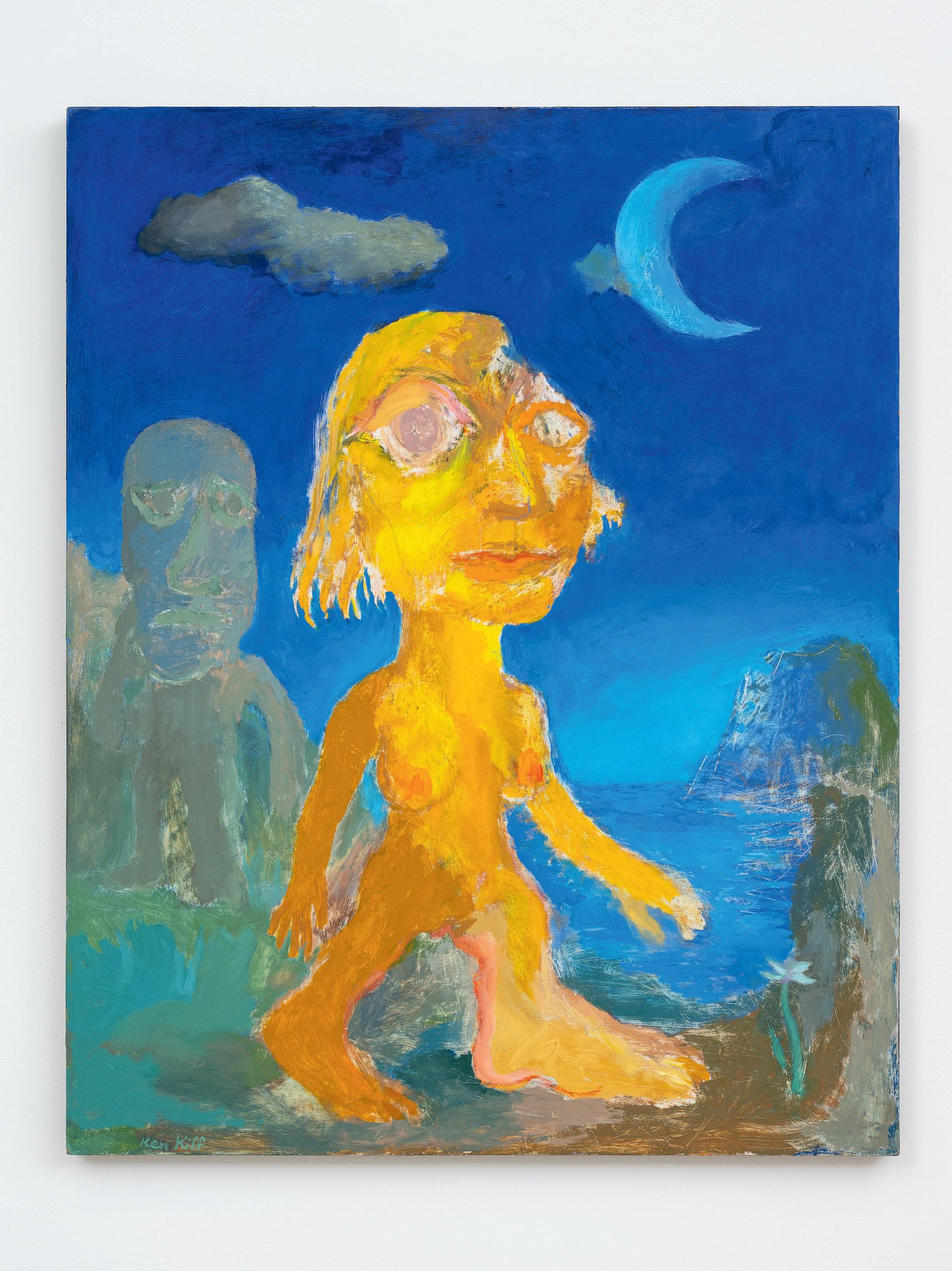

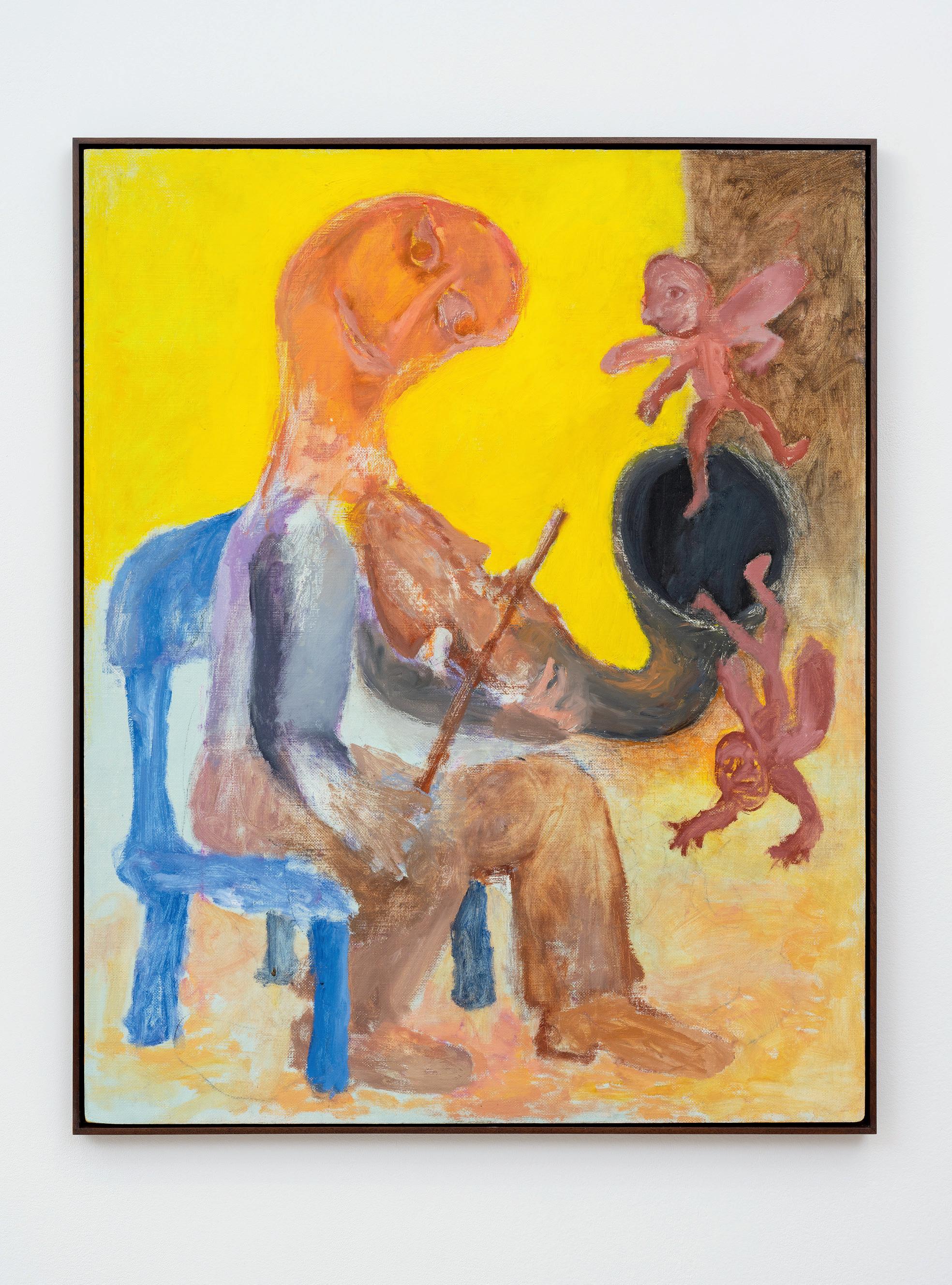

hales gallery’s forthcoming solo presentation of Ken Kiff (1935-2001) at Independent 20th Century is an important opportunity to reassess the work of one of the most singular artists in late 20th-century Britain. With a focus on paintings and prints related to Kiff’s residency as Associate Artist at the National Gallery in London (1991-93), the presentation expands on the spring 2025 exhibition at Hales London, The National Gallery Project. The selection of works, centered on a major triptych, reveals the extraordinary range of Kiff’s painterly imagination. His intense, searching response to the Old Masters enriched his art for the rest of his life. The residency produced numerous sketches, charcoal and pastel drawings, monoprints and etchings, and inspired 50 new paintings, some of which were still in progress when he died aged 65 in 2001.

Kiff took up residence in a large basement studio at the museum in 1991, the same year he was elected a Royal Academician. At the height of his influence, he was regarded by many of his contemporaries as one of Britain’s foremost postwar artists. He was a highly respected tutor at the Chelsea School of Art and the Royal College of Art, and exhibitions in the UK and US throughout the 1980s had established his distinctive oeuvre, yet in many ways he remained outside the mainstream. By the time

of his death, his reputation as “a true painter, ever fresh yet firmly rooted in the best traditions” had almost been eclipsed by the conceptualism of the Young British Artists. Today, however, many aspects of his work that once seemed alien to the dominant critical taste are finding fresh currency with a younger generation of artists, as well as new audiences.

For Kiff, fantasy was a way of thinking about reality. He described it as “a flexible realism” that “keeps to our fluid yet continuous awareness of reality, painting interacting with life, inside and out.” His affirmative visual poetics was expressed through multi-layered compositions that drew on traditions of art from different eras and from cultures far beyond the Western canon. His work often united the spiritual with the earthly, seeking to bring formal and pictorial elements together in rhythmic harmony, and to visualize the maelstrom of thoughts in an individual psyche.

In a formal sense, Kiff’s approach aligned more closely with European Modernism than with prevailing tendencies in British art at the time. He was also fascinated by the mystical radiance he found in Indian art and by the delicacy of traditional Chinese scroll painting. He saw parallels between painting and music, upholding “Braque’s thought that the canvas comes alive as a musical in-

strument does when it is played.” His images were always led by color, with a personal iconography—often misread as confessional—that combined figuration with abstraction, and at times, symbolic elements. Dualities, the divided self, and the tumult of consciousness, were abiding themes, expressed in recurring motifs such as journeys, encounters, caves, and anthropomorphic landscapes— and in compositions that borrowed from Cubism.

Kiff began the two-year residency with a degree of trepidation since it required him to leave his home studio and a great many works in progress. He was also hesitant about being viewed as part of the art establishment, feeling that the British tradition was too masculine and “at bottom pre-modern, accepting the old illusionism and the old idea of preaching a lesson (even if the idiom seems quite otherwise).” How, then, to respond to the iconography and storytelling of the Old Masters found in the National Gallery collection?

Few of the works Kiff made as a result of his residency were literal transcriptions of the original paintings; he sought instead to find their essence. Unfettered access to the museum gave him the opportunity to revisit works he already knew, including Giovanni di Paolo’s Saint John the Baptist retiring to the Desert (1454), with its vivid sense of journeying, and Rubens’s An Autumn

Landscape with a View of Het Steen in the Early Morning (c. 1636) from which he had previously borrowed the motif of a single tree. Kiff’s drypoint, After Giovanni di Paolo (1993), reimagines the episodic stages of the 15th-century painting with a more secular figure, and incorporates the naturalistic flowers from the side panels of the frame, which were added later.

Rembrandt, Red Tree and Cloud (1991) illustrates how he sought out specific references that were of significance to him. The image is a refined arrangement of elements: a tree on a hill, a rock protruding from water, a cloud, the fronds of river reeds. Executed in pastel, its green and red palette was a color contrast Kiff found particularly compelling: “the most compact and dynamic of color opposites.”

As the residency progressed he found other kinds of touchstones. His initial responses to Joachim Patinir’s Saint Jerome in a Rocky Landscape (c. 1515) made much of the painting’s shadowy drama in a series of charcoal and pastel drawings. But an encaustic work made later in New York, A/6 (2) Untitled - After Patinir (1996), illustrates how he sublimated these starting points into a composition that, while still echoing Patinir’s cave, steps and hills, is defined by the untouched white space in the painting’s upper-right corner. The pastel Hermit (1992), which floats even freer from any kind of attributable pictorial references, also evidences the kind of “organic, interdependent forming” that Kiff aimed for in all his work.

Giovanni Bellini’s The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (1505-07) gave rise to one of the most compelling works in the Independent presentation. Woman Watching a Murder (1996), initiated at the National Gallery and completed almost three years after Kiff’s residency, is an extraordinary reimagining of the original composition. In Bellini’s painting a distant fragment of blue sky offers the only respite from the claustrophobic forest scene, in which the woodsmen’s raised axes reiterate the violence of the friar’s murder. In Kiff’s image, suffused with shades of blue, a monumental blue-green naked woman towers over two small male figures picked out in brown. It is painted on museum board, a substrate that Kiff specifically employed to connect with the masterworks in the collection, and that holds the marks of many revisions.

The National Gallery Triptych (c.1992-97) carries many of Kiff’s enduring motifs: journeying, the sun, caves, flowers, trees, the old man, the radiant woman. It, too, was reworked extensively after being exhibited in an early, more graphic state. As its tonal range grew more subtle, the void-like depths between the figures and landscape became its major theme. An enigmatic note scribbled by Kiff on the reverse alludes to the Symbolist poet Mallarmé’s 1896 elegy for his close friend Paul Verlaine: “Shallow stream ill-spoken of death.” The triptych contains darkness and brightness, opacity and luminosity, colors mingled and glimpsed through each other: a cohesion of jostling elements that communicates a profound sense of encroaching darkness, yet emanates a sense of radiance and serenity.

Emma M. Hill is a curator and writer. She founded the Eagle Gallery / EMH Arts, London, in 1991 and is currently a guest curator at Turps Gallery, London. She curated the exhibition Ken Kiff: The Sequence at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, Norwich in 2018, which presented 59 works from the artist’s 30-year series of 200 paintings on paper, The Sequence, in chronological order for the first time.

GALLERY: GALERIE LELONG

BY CARLA BARBERO

in art and thought, Elda Cerrato (1930–2023) transcended boundaries with remarkable sovereignty. Across more than 60 years of work between Argentina and Venezuela, she was linked with some of Latin America’s leading avant-garde collectives, and yet she developed a multidisciplinary practice that stood apart from the dominant trends. Integrating science, politics, and spirituality, it could be described as an entire knowledge system of its own.

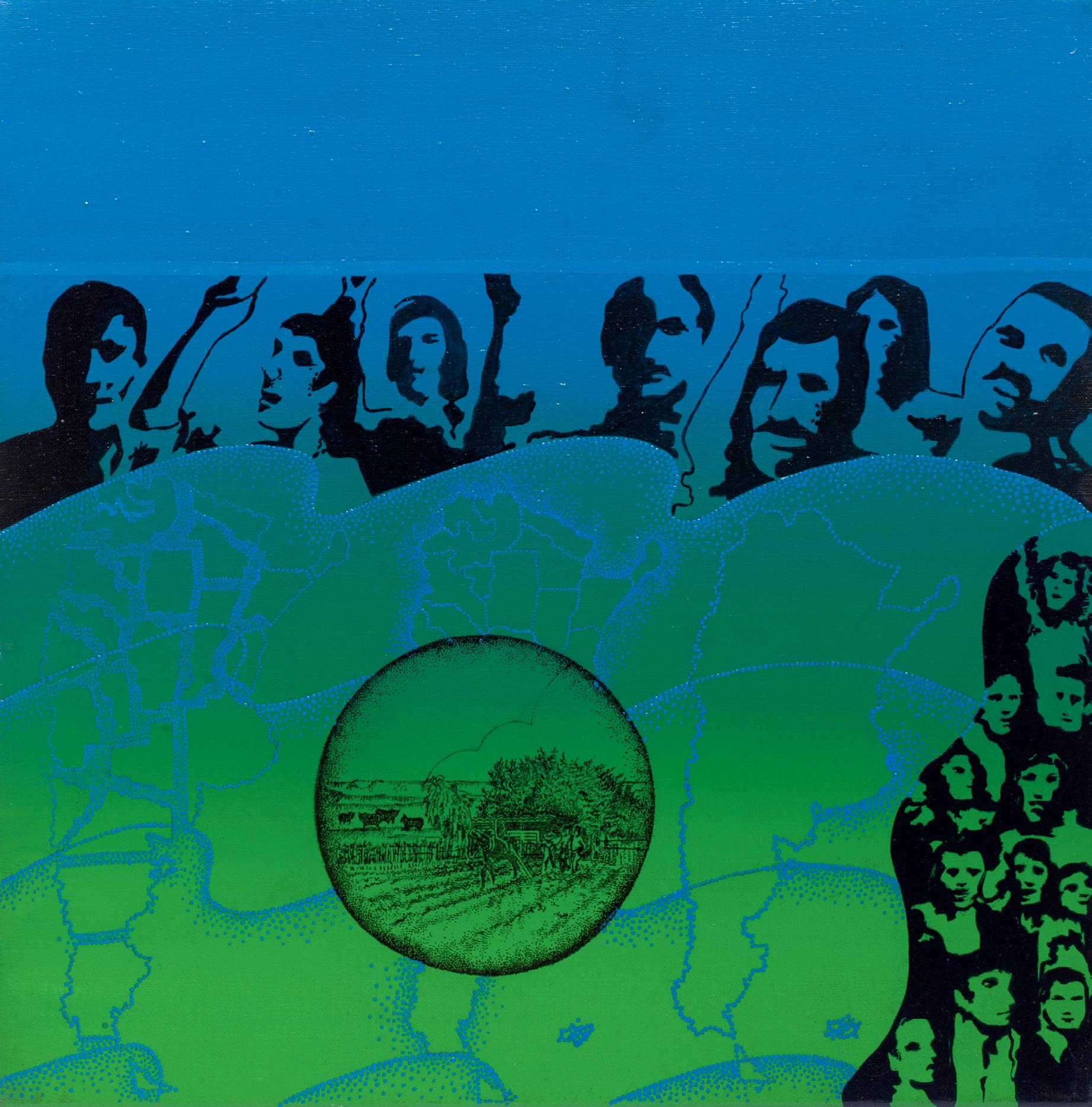

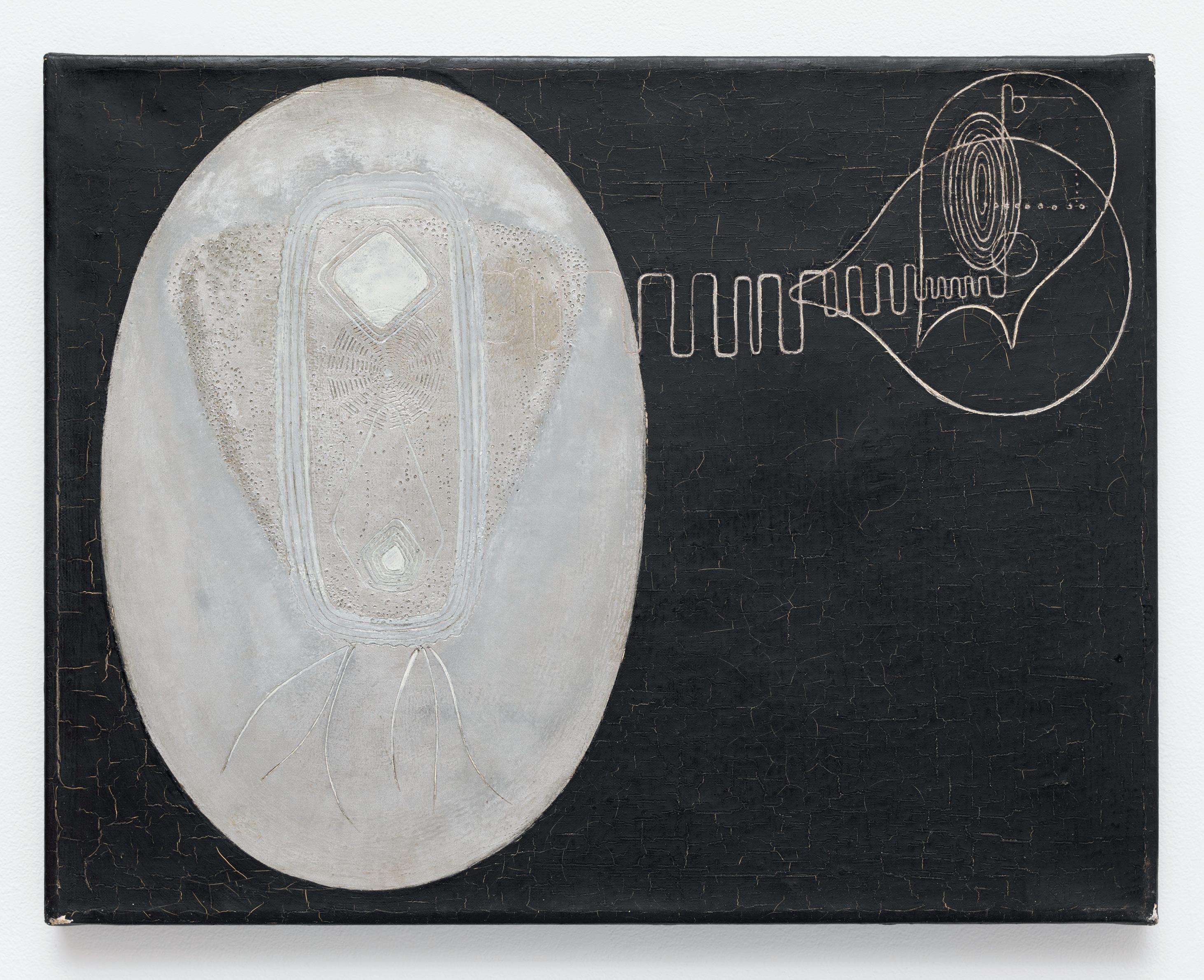

Galerie Lelong’s solo presentation at Independent 20th Century offers a concentrated reading of Cerrato’s visual universe, ranging from her early experiments with Informalist abstraction and cosmological works of the 1960s through the later depictions of maps, crowds, and political demonstrations of the 1970s.

Born in 1930 in Asti, Italy, Cerrato was forced into exile with her parents due to the rise of Fascism— first to São Paulo, and later to Buenos Aires. During her artistic training in the1950s, she engaged with geometric abstraction, Pythagorean proportions, and Gestalt theory. The Greek-Armenian mystic and philosopher George I. Gurdjieff was another formative influence, infusing her aesthetic inquiries with a vital spiritual dimension. With her partner, the composer Luis Zubillaga, Cerrato founded the first study group of Gurdjieff’s work in Argentina. Until the end of her life, she debated, disseminated, and

practiced his “Fourth Way,” and followed the teachings of his exponents such as P.D. Ouspensky, Maurice Nicoll, and Rodney Collin.

From her first trip to Venezuela in 1960—on the invitation of a local Gurdjieff study group—Cerrato forged close ties with the Caracas avant-garde, notably the collective El Techo de la Ballena (The Roof of the Whale), which advanced a politicized strand of Latin American Surrealism. This journey catalyzed the first major phase of her artistic trajectory, when she mixed with key figures like the poet and painter Juan Calzadilla and the art critic Marta Traba. Cerrato embraced a technical and imaginative freedom that enabled her to merge the experimentation of her early years with Surrealist automatism and the biological forms that had intrigued her since her university studies in biochemistry.

Untitled (1963), a painting first exhibited at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas, belongs to the series Formas en origen (Forms in Origin), in which one perceives both automatist drift and a persistent interest in recording invisible structures: cellular formations and biomorphic shapes evoking microscopic enlargements. This Informalist phase in Cerrato’s art can be viewed as a substrate of images on which she would build her later work.

On her return to Argentina in 1964, Cerrato and her husband settled in Tucumán—a northern province of

diverse climates, spanning from mountains to subtropical forest. It was there that the artist witnessed UFO sightings and encountered the distinctive ritual practices of the region’s rural communities. These experiences reignited her engagement with esoteric teachings, from the I Ching to the cult New Age writer Carlos Castaneda, and she devoted this period to creating her Ser Beta (Beta Being) series. These paintings and drawings articulated her vision of life, its forms and energies, deploying eroticism as a language to navigate reality. Through the recurring use of circles and ovals, Cerrato alluded symbolically to fertility, proposing an iconography that was as sensory as it was speculative.

From that moment, Cerrato’s paintings began projecting more precise images of the invisible energetic forces that—according to the theories she studied—gave rise to the world and continue to sustain it. Her series Epopeya del Ser Beta (The Epic of the Beta Being) offers an evolutionary narrative in which repeating forms and colors trace the patterns, movements, and transformations of the titular being.

Works such as Homenaje a los sistemas de comunicación. El resultado de una comunicación (Homage to Communication Systems. An Outcome of Communication, 1966) and Mineralización y Revitalización de Una a Otra Dimensión (Mineralization and Revitalization from One

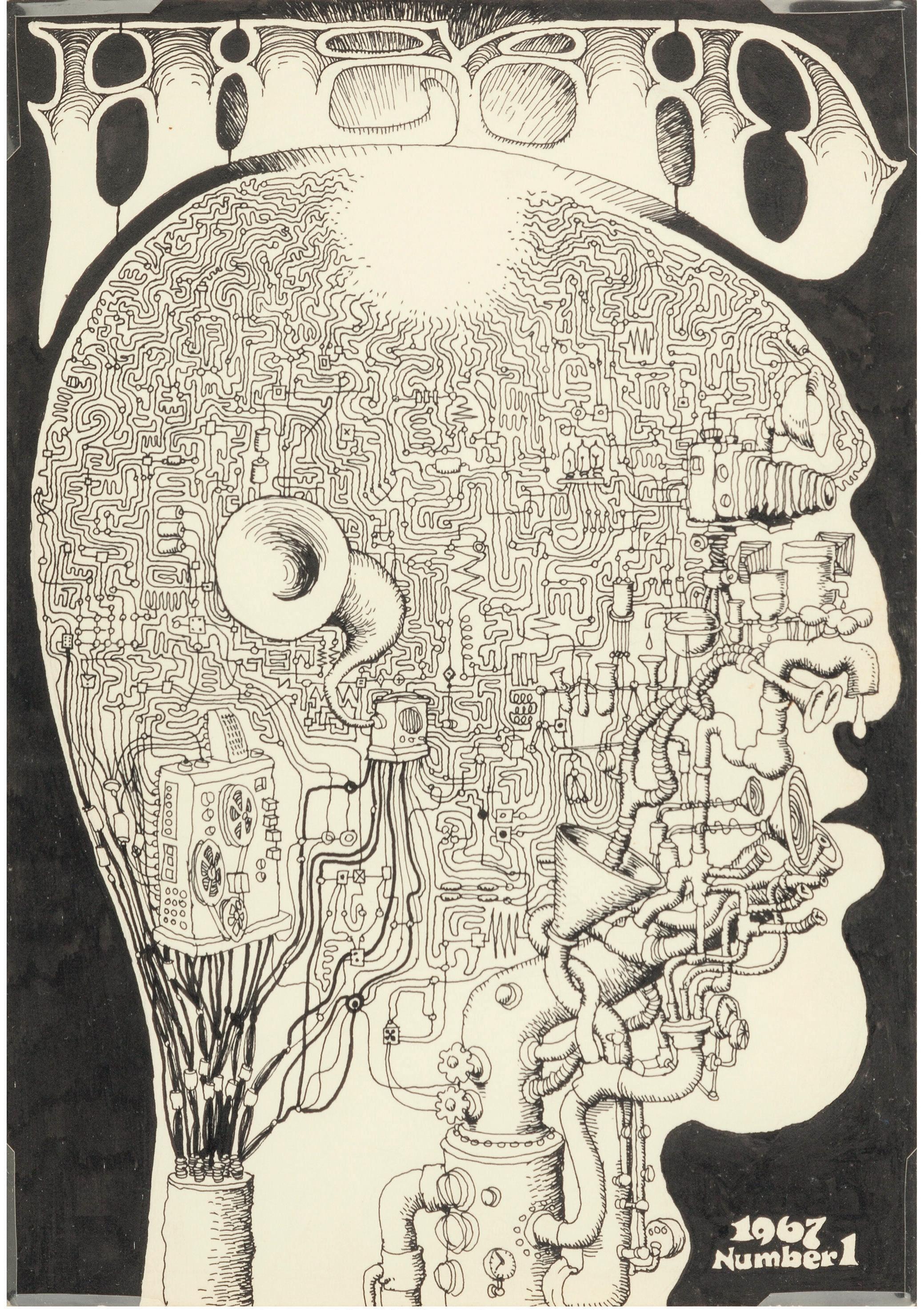

Dimension to Another, 1968) have an avant-garde grammar that synthesizes a spiritual critique of Latin America’s escalating political violence. While the regional art scene was dominated by Concrete movements with an internationalist spirit, Cerrato forged an individual kind of abstraction: soft, spiritual, and localized. This series, moreover, evokes 1960s cybernetics and communication theory, interweaving interior and exterior, spiritual and political. This duality—the tension between esoteric thought and socio-historical awareness—is a fundamental key to Elda Cerrato’s work across her six-decade trajectory.

Following the 1966 military coup in Argentina, Cerrato and her family moved back to Buenos Aires. The artist recounted how this return to the city—and the rupture of the idyllic period in Tucumán—forced the Beta Being to “engage with reality.” Driven by the nation’s intensifying political turmoil, works like Untitled (1972) depict the Beta Being summoned to our planet amidst historical urgency. From this point onward, Cerrato began incorporating more overtly political imagery reflecting contemporary events.

Geometric forms light up like screens displaying popular uprisings, scenes of labor exploitation, and sprawling industrial vistas. The vantage point in these paintings is striking: an aerial gaze hovers over the ter-

ritory of the Americas. This perspective permeates many of the 1970s paintings, drawings, and heliographs in which Cerrato depicted crowds and maps. Merging the urgent graphic language of revolutionary movements with avant-garde art, this body of work marked a conceptual turn, confronting politics, semiotics, and spiritual visions.

As the violence intensified, Cerrato went into exile once again—back to Caracas—together with her husband, who had been removed from his position as artistic director of the Teatro Colón at the onset of Argentina’s 1976 dictatorship. It was during this new period abroad that she developed a deeper awareness of her Latin American concerns, critically reassessing the Eurocentric lens through which she had been trained.

During the 1980s and 1990s, her paintings grew increasingly complex. Her color palette shifted, and the sense of scale expanded. The images center on the fragility of democratic institutions in the aftermath of a dictatorship: masses of faces represent the victims of enforced “disappearance”—human rights abuses committed in multiple Latin American countries under military rule. Works presented in the 1989 exhibition El ojo y la fisura (The Eye and the Fissure) introduced Aztec iconography and mythological symbols related to the earth goddess

Coatlicue, suggesting a connection to ancestral memories rooted in Mesoamerican tradition.

Cerrato deepened her investigation into ideas of time, not as a linear progression but as an interconnected continuum—influenced by her esoteric experiences as well as by quantum physics and scholars such as the Chicana feminist writer Gloria Anzaldúa. The concept of the past as an active force lying not behind, but ahead, was marginal at the time, but can now be aligned with contemporary thinkers such as the Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. Cerrato’s prescience was remarkable in this regard.

Rituals, ancestral myths, and personal memories guided her final works, which extended beyond the 2000s. The last series can be viewed as exercises in recapitulation—dream-like scenes in which the artist united fragments of her past works with intimate familial events without hierarchy.

Elda Cerrato’s work takes on a singular relevance when we consider that, even today, there is debate over whether Latin America has managed to forge a true artistic canon—one that stands apart from the legacy of colonialism and the many ways it continues to manifest in contemporary forms of domination. Her sovereign images offer up a revolutionary vision in response to a convulsive present.

Carla Barbero is a curator and researcher based in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She is currently Curator at the Centro Cultural Recoleta. From 2017 to 2022, she was Head of the Curatorial Department at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, where she led the first retrospectives of Elda Cerrato, Ad Minoliti, Alberto Goldenstein, and Max Gómez Canle, alongside curatorial projects with Adriana Bustos, Mónica Millán, and Claudia del Río. In 2025, she curated the first institutional exhibitions of Lucrecia Lionti and Laura Códega at MALBA and Recoleta, respectively. She is the author of several publications on Argentine art and teaches curatorial studies at Universidad Torcuato Di Tella and Universidad Nacional de Córdoba.

BY JENNIFER JOHNSON

ranging across the work of Georges Rouault (1871–1958) and the major themes that preoccupied him, the select group of works presented by Nahmad Contemporary and Skarstedt at Independent 20th Century showcase the depth of craftsmanship and philosophical thought that characterize the artist’s peculiar form of modernism.

Born in 1871, during the siege of Paris, Rouault was originally apprenticed to stained glass makers before training at the École des Beaux-Arts under the great Symbolist painter, Gustave Moreau. His contemporaries at the academy included Henri Matisse, alongside whom Rouault participated in the notorious Salon d’Automne exhibition of 1905. Art critic Louis Vauxcelles disparaged the color-saturated painting of Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck as that of “wild beasts” (les fauves). Rouault’s work, hanging two rooms away, shared many of the qualities of so-called Fauvism. The surfaces had a scrawled and frenetic appearance, and the subject matter was almost submerged by the mass of painted marks.

Rouault linked this period of work to the death of Moreau, who had become a mentor and father figure to him. “A kind of outburst occurred,” Rouault wrote,

“and I began to paint with a kind of frenzy.” Some of this can be seen in Fille (Femme aux cheveux roux) from 1908, in which the figure of a prostitute dominates the canvas. The orange and blue washes, set against black gouache lines, emphasize the fleshiness of the body and create a haunting image of a figure on the edges of society.

As with the Fauves, the language of the critics who reviewed Rouault’s early paintings of prostitutes and clowns was filled with images of anger or madness— these works were repeatedly accused of being too violently dark. By the time of the First World War, Rouault was also making prints, including the series Miserere, a meditation on suffering. A strong sense of form and linear style began to replace the wildness of earlier works. The placement of shapes next to each other, layered with brushmarks, recalled both his printmaking and the influence of stained glass.

Rouault’s later subjects were calmer, too— even still. He had long explored the allegorical potential of clowns and the circus, with a particular interest in Dostoyevsky’s idea of the “holy fool.” Pablo Picasso’s “rose period” (1904-06) works were similarly preoccupied with these themes. But where Picasso foregrounded

a dramatic melancholy, Rouault’s interwar and postwar work approached the clown as a portrait with an air of faded grandeur. He used framing devices indebted to Byzantine iconography around the clowns, as well as in works such as Théodora (c.1949) and in multiple images of the face of Jesus Christ. Often, as in Pierrot (c.193738) or Clown anglais (c.1937), these are fused with the suggestion of curtains, a motif derived from both grand portraiture and the stage.

Theater—and, by extension, the artificial nature of appearances—is deeply important to understanding the spiritual and moral dimensions of Rouault’s work. He often directed his criticism at the corrupt values of modern society, for instance in the damning depiction of two judges, Juges (1937). Alongside this, a number of works questioned the opposition between the powerful and the down-and-outs. Théodora depicts the wife of the Roman emperor Justinian, a woman who began as an actress and prostitute, and rose to empress. Drawing heavily on the Byzantine mosaics at Ravenna, Rouault’s representation aligns her with his multiple paintings of performers who blur the boundaries between life and theater.

Louisette (1946) performs the same maneuver. The name means “warrior” and the image replicates the composition of a traditional portrait of an aristocratic woman. But there is a darker side: “louisette” was the first name given to the guillotine in the early days of the French Revolution.

In Satan (1929-39), the devoutly Catholic Rouault echoes his imagery of Christ with strong black lines, a limited palette, and a framing structure that evokes the imprint of Jesus’s face on the Turin Shroud. To give this particular work the title of “Satan” calls everything about this vision into question. Could it be Christ’s vision we are witnessing? Saint Veronica, whose legendary veil also bore the image of Christ, was another recurring theme in Rouault’s oeuvre. His thick layers of paint offer a material counterpoint to the translucent veil of Veronica or the Turin Shroud, as if this higher vision might be accessed through the act of painting itself.

There is something of the stage set about

Rouault’s late landscapes and ensemble scenes such as Cirque de l’étoile filante (1938), Paysage biblique (c.1940-48), and Le fugitif (1945-46). Within fragmented interiors or exteriors, the figures are held by the fierce lines of Rouault’s design. The luminescent arrangements of hills, trees, and the sun in these late compositions also relate to the tarot, whose imagery recurs across Rouault’s work during this period, marking his interest in the ancient mystical beliefs of Hermeticism as well as his own Catholicism. Le Fugitif alludes to the Fugitive card in some traditional tarot decks, the equivalent to the Fool. Rouault’s use of the tarot reflects a widespread interest in the early to mid-20th century in the interconnections between different philosophies of religion and in mystical, rather than scientific, systems.

From the early 1900s onwards, Rouault often worked at a table instead of an easel, eschewing the traditions of fine art for the methods of the artisan. The table in his studio was littered with canvases in

various states of progress, paint tubes, and brushes. Photographs show him dressed in a surgeon’s white gown and hat, a gift from his physician son. Rouault later painted various clowns in similar attire, and there is a strong sense of the artist casting himself as the innocent circus figure, or the fool.

Rouault’s work encompasses the serious social and political concerns of the early 20th century, as well as the experimentation and avant-gardism of modernist painting. Questioning perception at every level and positioning himself, like the clown, as an outsider looking into society, Rouault also questions painting itself—challenging the medium to take on the deepest and most difficult of subjects.

Dr Jennifer Johnson is the author of Georges Rouault and Material Imagining (Bloomsbury, 2020). She is currently the Paul Mellon Fellow in British Art at the British School at Rome and is working on her next book about women artists and postwar abstraction.

BY JULIE BAUMGARDNER

speeding teslas and slow-moving tractors alike cut across the busy country road that leads to Judy Pfaff’s sprawling studio compound in Tivoli, New York. Tucked away from the traffic is a cluster of eight buildings— barns, garages, and a converted house—that the artist acquired in 2004 and has tailored to fit her world. Pfaff has gradually moved full-time into the site, which now contains spaces devoted to sculpture, drawing, printmaking, and storage for her immense inventory of materials. Her beloved “stuff” is scattered everywhere.

Pfaff’s studio counts two assistants, rising to four when installing, along with her dog, Micky, and cats, Harry and Lizzie, who roam freely amidst the wall hangings, drafting tables, and filing cabinets. Though Pfaff relies on her team for help with heavy lifting, framing, and technical troubleshooting, she prefers to “wait until everyone leaves” and work alone, she says. “The idea of having someone make your stuff for you… What fun is that?”

Much like the rural road outside—part rapid bypass, part meandering lane—Pfaff’s career has been both electric and steady, rooted in determined instinct

rather than birthright or pedigree. She studied with the abstract painter Al Held at Yale, exhibited at Artists Space and the Whitney Biennial in the 1970s, and spent nights hobnobbing at Max’s Kansas City, Magoo’s, and Barnabus Rex. She quickly became a fixture of the downtown New York scene, represented by Holly Solomon and befriending fellow artists like McArthur Binion, Nancy Graves, Ursula von Rydingsvard, and Elizabeth Murray. Friendships are the fabric of the arts, and they have been a throughline in Pfaff’s life. “It’s true I have a lot of friends,” she says with a laugh. “We were unstuck in the world,” she once remarked to Binion, describing the wild, generative ’70s when they worked, taught, and partied together—a generation whose players continue to shape contemporary tastes half a century later.

Yet despite Pfaff’s revered reputation amongst her peers, her expansive, relentless output hasn’t charted a clear linear path to success in the art world. This fall marks a moment to recenter her in the conversation, with her latest gallerist Cristin Tierney soon to present an exhibition of historic works at Independent 20th Century. The selection of large-scale sculptures from the

1980s and ’90s, such as La Calle, La Calle Vieja (1990), mixed-media street signs, and collages on paper reflects Pfaff’s vital contribution to Post-Minimalist abstraction. “If the Minimalists revealed space in all its static grandeur and the Post-Minimalists messed with it beyond belief, she has more than carried on,” art critic Roberta Smith once wrote.

Tierney’s fair presentation—a prelude to a solo exhibition of new and recent works at the gallery in Tribeca this October—is a reminder of just how prolifically Pfaff has circulated through the commercial and institutional art worlds. Since 1975, she has hardly gone a year without a solo or group show, racking up more than 500 exhibitions to date in the United States and internationally, along with a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, and an American Academy of Arts and Sciences fellowship. A longtime professor at Bard College, she served as co-chair of the Studio Arts department and has mentored generations of artists from her Hudson Valley base. Does she go to the studio every day, even when there’s no exhibition on the calendar? Of course. Then again, there’s rarely been a time she wasn’t preparing for a

specific event—even if, as she admits, some were “shows I hated” (she’s not telling which ones).

And yet, there remains a lingering question in the story of Judy Pfaff: why isn’t she more of a household name? As Smith wrote in 2003, “you would think that Judy Pfaff would get more respect.”

The artist describes her work as “rangy” and “open-ended”—not qualities that make it easy to market. “Most galleries really don’t want you to make things that are not sellable,” she says. Space and form are her primary concerns. Many works are site-specific, created in direct response to the places where they were being shown; they do not fit neatly into series or thematic cycles. Instead, they bear what she calls her “handwriting”—a signature style that’s immediately recognizable but constantly evolving. “It’s all very noodly,” she says with a wink. “That’s an academic term.”

Pfaff’s installations whirl with tangled lines, found objects, wires, plastic, resin, wood, and debris—

composed with care but infused with the chaos of life. The critics don’t quite know what to make of them. One Artforum reviewer credited her as “the ultimate chairwoman for a prom decorations committee,” while David Frankel wrote of her work leaving him “a little unsatisfied.” Informed opinions of Pfaff’s art have been scarcer in the past decade, coinciding with the broader decline of longform criticism. Instead, attention has turned toward the artist herself. (Why did Al Held greet her at Yale with the line, “So, you’re the new dumb blonde?” Her ready comeback—“Who are you, the janitor?”— launched a lifelong artistic friendship.)

Pfaff is often asked to explain whether the exuberant disorder of her work is autobiographical. “Every artist I know who is not only good, but very popular, has this narrative, this big story about who they are,” she says. “I don’t care about that stuff. It’s not only not interesting—I don’t even remember it.” And yet, her backstory is striking: born in London and raised by

her grandmother, she moved to Detroit at 12 to reunite with her mother, married an Air Force officer at 16, left him at 20 to attend art school, and was a New York darling by 27.

As much as Pfaff’s work is an extension of her, identity has never been the core of her practice. “I like making stuff,” she says simply. “So, let me do that.” She remembers that Held once asked her, “What are you making?” and she replied: “It’s somewhere I would want to be. I’ve never been there. But I dream about these places. They’re all kind of fantasies in that way—imagined landscapes, not real. Nothing biographical.”

Pfaff even refrains from teaching her students in the language of the academy. “Just say it straight,” she demands. Some artists like to talk the talk, but she is an irrepressible maker of objects and ideas. Her work spins stories without needing to resolve itself into neat, marketable narratives. It’s deeply human, in all of its potency and mystery—all of its mess.

Julie Baumgardner is an arts and culture writer, editor and journalist who has spent nearly 15 years covering all aspects of the art world and market. Her work has been featured in Bloomberg, Cultured, Financial Times, New York Magazine, The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and many other publications. Follow her @juliewithab

for marco pelle, choreography has never belonged solely to the stage. It is a language that can slip into unexpected spaces—onto film, into fashion, across the textures of opera—and now, into the frozen stillness of art history. For Bollettino, Pelle conceived a custom shoot unlike any he has undertaken before: a living gallery where dancers from Milan’s Teatro alla Scala step inside the frames of painting and sculpture, translating canonical works into movement and flesh.

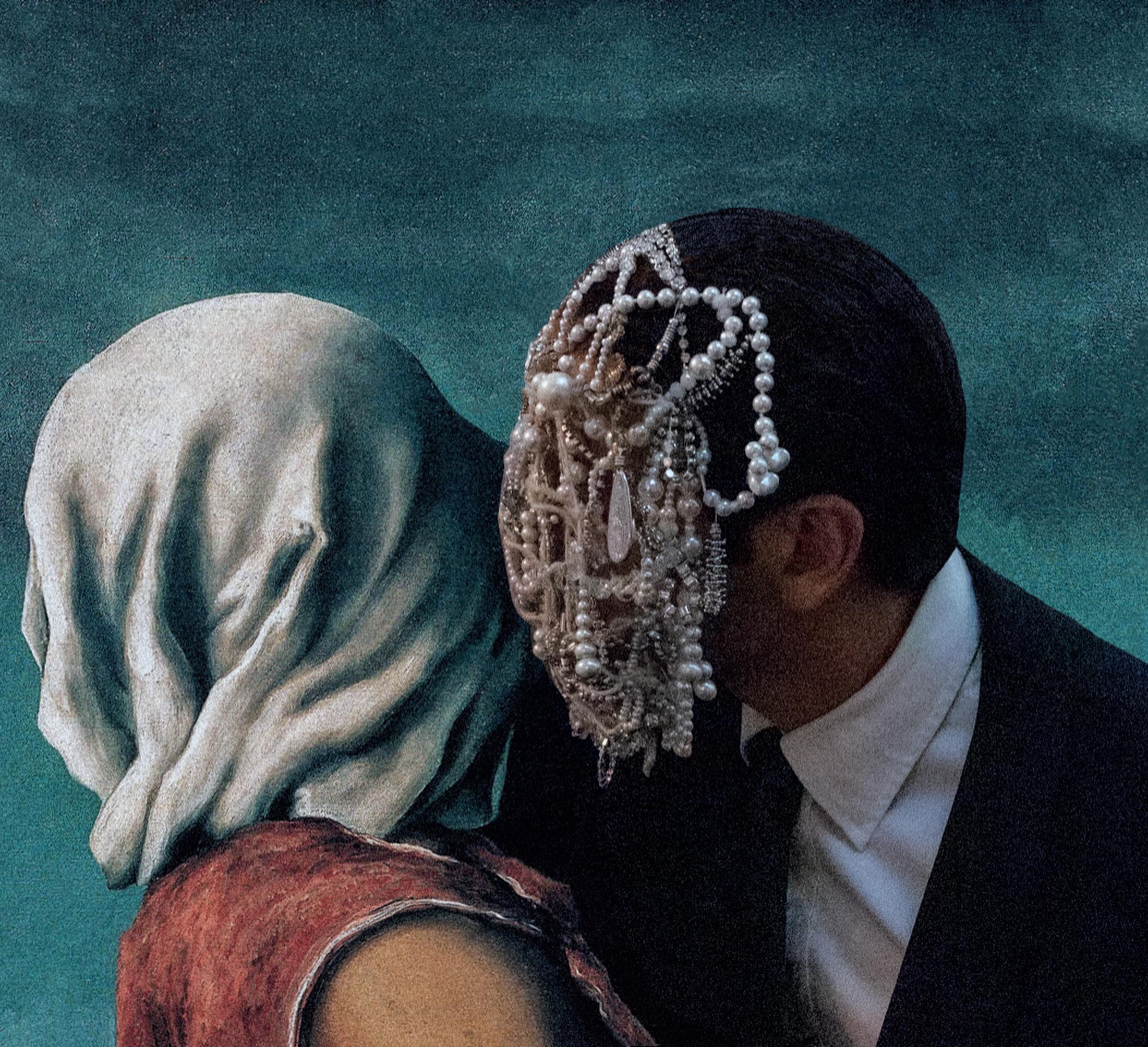

Titled Statuesque, the project brings together principal dancers in recreations of masterpieces that stretch from the Renaissance to modernism: Michelangelo’s Pietà, Caravaggio’s Boy with a Basket of Fruit, John Singer Sargent’s Madame X, Magritte’s The Lovers, and Antonio Canova’s Venus Victrix. Captured through the lens of photographer Filippo Thiella, these tableaux oscillate between reverence and reinvention—at once homage to the originals and evidence of how bodies, unbound from marble or canvas, can reanimate history.

“I wanted to explore the link between statuary beauty and statuary stillness,” Pelle explains. “A sculpture is fixed forever in time, a painting bound to its frame. But dance resists permanence. It exists only in the moment, vanishing as soon as it is lived. Bringing the two together is almost an act of paradox. That’s how statuesque came about. ”

The choice of works was deliberate. Michelangelo’s Pietà—a mother cradling her son in sublime grief—becomes an exploration of weight and surrender when embodied by dancers, their muscles straining to hold the impossible poise of marble. Caravaggio’s youthful boy, lush with fruit and sensuality, acquires new urgency when translated into breath and movement, the