— antoine pierini — en rêvant la méditerranée

Heritage conservation is a cornerstone of the work done by the Centre des monuments nationaux, yet it can only flourish to the full in a spirit of transmission and sharing. That is why safeguarding this legacy and passing it on—while also connecting it to contemporary creation—forms one of the convictions and focal points of a dynamic institution that is itself over a hundred years old.

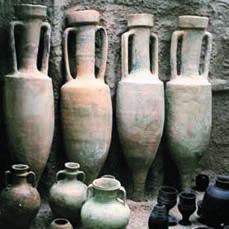

Today’s artists are regularly invited to show their work in monuments, capturing the spirit of the surroundings while also enabling creative freedom. The result is a virtuous circle. In these strange and volatile times, monuments more than ever reflect an unbroken bond with the land and people’s attachment to these places. Temporarily exhibiting contemporary works amid historical collections helps cast our legacy in a new light, encouraging visitors to discover and rediscover these places. The approach is now well established and has gained a real following. National monuments effectively promote culture and breathe new life into regions while raising broad awareness of art and culture. Villa Kérylos is a wonderful showcase and is the perfect setting for the glass art of Antoine Pierini, an artist, designer and master glassmaker from Biot. His pieces reflect the bright Mediterranean sunshine; their shape conjures the memory of antiquity. In these surroundings, amphoras—antique vessels previously valued only for their contents— are transformed into works of art that attract the light. Unburdened of wine and oil, they resemble Cycladic figurines, guiding visitors towards Théodore Reinach’s vision of halcyon Greece. True to Villa Kérylos tradition, Pierini neither copies nor replicates antiquity: he uses its language to inspire his art, replete with references and evocations.

“It is from memory that men acquire experience,” insisted Aristotle in Metaphysics . Antoine Pierini’s art sits comfortably somewhere between memory and experience. His glasswork is a paean to the past. Personal. Familiar. Collective. The young Antoine could have followed the family tradition and, like his father, Robert Pierini, continued to create pieces that are an integral part of our everyday lives, further forging his reputation as a skilled craftsman in the process. But he was determined to go further. Strike out on his own. Take the road less travelled. The exhibition of his recent work at Villa Kérylos brings us face to face with that eternal-yet-essential challenge in determining the boundaries of art, which are sometimes so hard to distinguish, particularly when it comes to the Greek word τέχνη . Where exactly does art begin and techne -craftsmanship end?

Antoine Pierini’s art embodies a technique—a craft—in which Greek sculptors and potters excelled, and which is employed by the “glass artist” (a term he willingly adopts) to bring us unique, unparalleled pieces. Although seemingly frozen in time, each piece is captivating. Each draws us in and holds us hostage. Every object has its own story. Every story has its own source. That elusive “where”. The place where we were, where we long to be.

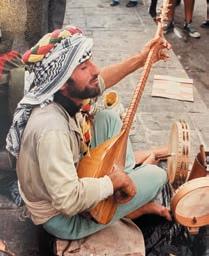

This never-ending Mediterranean odyssey weaves a tale of life through ports and cities, through quiet neighbourhoods and districts ravaged by war, through reeds that soar like the souls of free men.

Pierini says his pieces are “an invitation to travel through space and time”. He calls them “living works”, insisting he wants them to challenge people and make them think. To quote the French critic, author and philosopher Roland Barthes, commenting on the work of American painter Cy Twombly: “The Mediterranean is a vast complex of memories and feelings: the languages of Greek and Latin, culture, history, mythology, poetry, teeming with life in all its forms, colours and lights, where the land meets the main.“

With the exhibition En rêvant la Méditerranée , Antoine Pierini urges us to enter his world of form, colour and light—a world from which

black has been banished. Everything is a mix of vivid volume and sunny softness. There is no overbearing presence. We all find a place. Our place. It is the sensuousness of the artist and the light of the Mediterranean, of humanity and of the sea that bring that softness to each of these pieces, imbuing each with its own Greekness. “Artists reveal themselves in what they choose to reject,” wrote the French poet Paul Valéry. Antoine Pierini is not afraid to take risks. He turns his back on the easy path and strives to lift us up, like a Promethean artist. He embodies a man’s struggle to re-establish balance, to re-establish justice: picking up the torch carried by Théodore Reinach and Emile Zola, he has entered into an artistic and moral contract with humanity. The words of Marc Chagall resonate throughout the rooms that harbour his works, on the shores of the Mediterranean: “To my mind, these paintings do not represent the dream of a single people but of all humankind.” And if we close our eyes, we can picture the artist laying his amphoras and pebbles on a beach in Crete, at the feet of Alexis Zorba, or in Alexandria, under the pen of Constantine Cavafy.

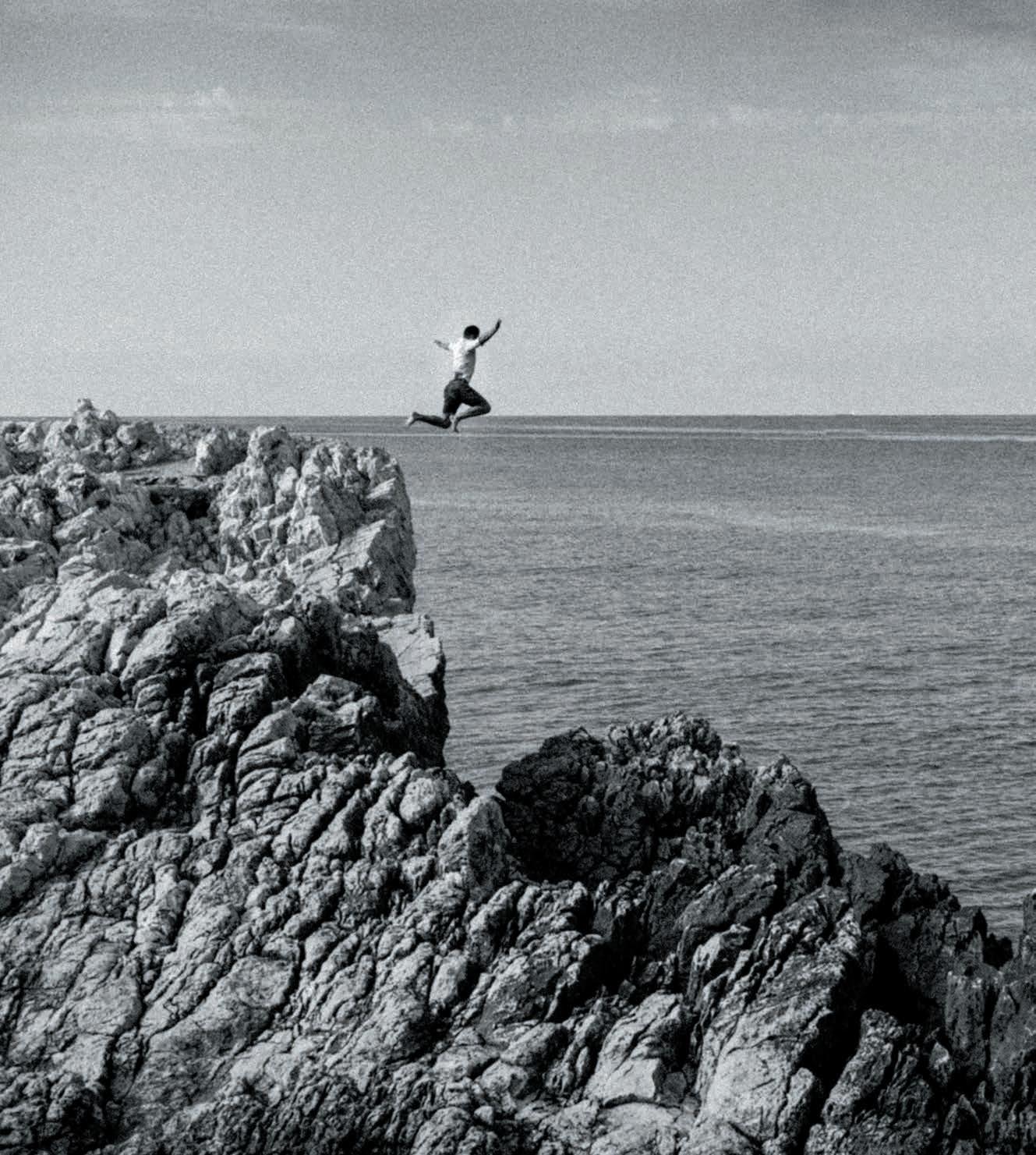

It was perhaps inevitable that Pierini’s path should cross that of another ardent champion of the Mediterranean, Albert Camus. The artist readily identifies with the author’s Pensée de Midi , which has often been translated as “Thought at the Meridian”, referring to a way of thinking that is the antithesis of nihilism, destruction and sterility, and which Camus made the focus of his book The Rebel in 1951. The Mediterranean spirit runs contrary to anything that is dark; the antithesis of those Nordic and Romantic ideologies so distant from the light that embraces the South of France. Following the fight against Nazism, as Stalinism triumphed in Eastern Europe, the author’s words struck a resolutely hopeful chord and carried unique weight: “The youth of the world always find themselves standing on the same shore. Thrown into the unworthy melting pot of Europe where, deprived of beauty and friendship, the proudest of races is gradually dying, we Mediterraneans live by the same light. In the depths of the European night, solar thought, civilization with a double face, awaits

its dawn. But it already illuminates the paths of real mastery.” This real sense of mastery is an apt definition of the glass artist’s technique. An admirer of René Char and Paul Valéry, Pierini appreciates the concision in their writing, the density of their words, the refinement of their structure—which is what he strives to capture in his own work: weaving glass, marble and metal into “living” sculptures. A closer look at the “body” of his pieces shows Pierini is as much a sculptor as a master glassmaker: he is a glass sculptor. In this, he again crosses paths with Camus, who lauded sculpture as “the greatest and most ambitious of all the arts”, the underlying principle of which is to stylise gestures and movements, or, as the author wrote in The Stranger, to “imprison, in one significant expression, the fleeting ecstasy of the body or the infinite variety of human attitudes”.

Pierini’s glass sculptures stand at the border between figurative and abstract: he takes an amphora, an iconic Mediterranean vessel, and turns it into an anthropomorphic object that evokes the memory of Cycladic figurines; he takes another block and turns it into a reed growing out of a mineral base; he spins coloured glass into a cypress, a Mediterranean tree par excellence; he takes the all-important word lumière (light), and fashions it into a flash of dazzling neon. In this mix of memories and feelings, humanist culture, long decried, is far from a lukewarm presence destined to disappear down the drain of a Greek villa. Hardened in the heat of Nietzsche and Char, this humanist culture—this ethic—flows like a burning breeze across the fragile glass art installed on the shore of the Mediterranean, whose archetypal forms append question marks to our certainties. En rêvant la Méditerranée embodies Antoine Pierini’s promise: a chance to banish all assumptions and come alive again.

VILLA KÉRYLOS

VILLA KÉRYLOS

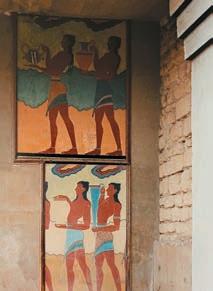

Villa Kérylos is more than just an architectural achievement. It is a complete work of art in its own right, born in the fertile, erudite mind of Théodore Reinach and brought to life by the talented architect Emmanuel Pontremoli. The two men met at the World’s Fair in 1900, where Pontremoli was showing the fruit of his Pergamon research. Together, they brought in the finest craftsmen to build this wonderful monument in Beaulieu-sur-Mer between 1902 and 1908.

From floor to ceiling, everything in the villa was dreamed up, designed and made in six years: every piece of furniture and fabric, every handle on every door and window, every switch and socket, even every item of crockery and cutlery… nothing was overlooked.

Villa Kérylos is a showcase for the learning of the time, encapsulating an embodiment of knowledge. Yet while it is all this and more, it is neither a copy nor a reconstruction. It is a creation inspired by Ancient Greece and classical Mediterranean culture as a whole. Rather than a replica, it is a reinvention of antiquity built at the dawn of the 20th century—a deep dive that transcends time and space, as if Agnaptos and Callicrates had erected a lavish abode from their own era today. Like Reinach and Pontremoli, they too would surely have included modern amenities like running water, heating and electricity.

Théodore Reinach was an insatiable erudite with a keen interest in virtually any subject. His unparalleled enthusiasm gave him the drive to master anything he put his mind to. The list is not only long; it is astounding. One of the most brilliant Greek scholars of his time, he was passionate about Grecian domestic architecture, a field previously overlooked in favour of more high-profile undertakings. And yet, his innate vocation as an archaeologist—or seeker—led him to the innovative view that archaeology is not ancillary to history; it is an untold story. Reinach focused on the part of society left out of the history books, puzzling it out to better propagate it.

Théodore Reinach the Greek scholar was also a staunch defender of heritage: in his capacity as deputy for the Savoy region from 1906 to 1914, he was the rapporteur for the founding law of 1913 ensuring effective conservation of historic monuments. On a more personal

—

kérylos means “halcyon”, a mythical bird likened to the kingfisher, said to be a good omen. —VILLA KÉRYLOS

level, he also bequeathed his villa to Institut de France to ensure the building and its contents would be shared with as many people as possible for as long as possible.

Today, the Centre des monuments nationaux manages Villa Kérylos and oversees maintenance and events. It organises contemporary exhibitions, which, far from seeking conflict or provocation, aim to raise awareness in keeping with the spirit of the place. With the work of Antoine Pierini, glass brings a fresh splash of colour to the villa, particularly since the material was deliberately left out at the time of construction given its very limited use in antiquity.

Pierini turns amphoras—previously vessels with no inherent value other than that of their contents—into works of art in their own right, into sculptures and figures, fettering light only to free it. The result is a wonderful months-long tribute to the dazzling work of Théodore Reinach and Emmanuel Pontremoli.

—

“Antoine Pierini’s work explores the ties between objects and their environment, with a focus on forms, lines, volumes, colour and light. In so doing, he seeks to create a sense of overall cohesion between his pieces and the surrounding space.”

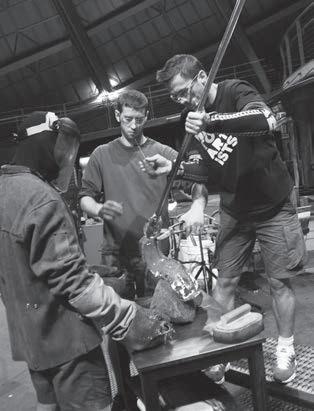

Antoine Pierini is a master glassmaker, designer and glass artist. Born in 1980 in Antibes, on the French Riviera, he lives and works in the village of Biot, a traditional hub for glassmaking. Raised by a mother committed to environmental activism and a father who pioneered the French incarnation of the Studio Glass Movement. Antoine was exposed to the small world of master glassmakers from the earliest age. He learned the fundamentals of glassblowing and how to handle the molten material at the family studio in Biot, established 21 years ago in an old oil mill, where he has been pursuing his passion since 2005.

Antoine has gone on to hone his expertise and experience through further training in fusing, casting, filigree, murrine, engraving, figurative sculpture, neon, plasma and vitreography, along with residencies and installations in artists’ workshops, museums (MusVerre Sars Poterie in France, Museum Of Glass in Tacoma, USA) and international art centres (Pilchuck, USA, Cesty Skla Ways of Glass, Czech Republic, and Niijima Glass Art Center, Japan).

Travel and encounters with the leading lights of the glass world led him to develop his own approach to contemporary glass, conveyed through his accumulations and installations. His projects have also involved collaborations with electricians, marble craftsmen and metalworkers. The style of his pieces stems in large part from the search for clean, sparing design, in keeping with nature and inspired by the creations of Constantin Brancusi, in terms of their fundamental form, and Arman, for his ability to cast objects in a new light.

Antoine Pierini’s international influence includes collective exhibitions at an array of venues around the globe, along with permanent exhibitions at GlasMuseum Lette in Germany and the Museum of Classical Art in Mougins, France. He has also expanded his studio in Biot to create the Pierini International Glass Art Center, which seeks to promote the art of glassmaking both locally and around the world, and is part of the Ateliers d’Art de France network. The larger location also provides residencies for artists, who can use the premises to show their work and share their expertise.

Antoine Pierini’s work features in a number of private and museum collections in France and around the world:

Glasmuseum Lette, Lette, Germany

Musee d’Archeologie, Antibes, France

Niijima Glass Art Center, Niijima Island, Japan

Tacoma Museum Of Glass, Tacoma, Washington, USA

Van Der Togt Museum, Amstelveen, Netherlands

Vledder Museum, Vledder, Netherlands

Musee du Verre et Centre d’Art de Carmaux, France

Museo Del Vetro Altare, Altare, Italy

Born in Antibes, France Trains at the studio founded by Robert Pierini in Biot, France

1990

Meets Lino Tagliapietra at ADAC - Centre des Arts du Verre in Paris, France

1996

Spends time in Seattle, USA, visiting several studios, including those of Dale Chihuly, Mark Eckstrand, David Bennett, Ben Moore and Paul Marioni

Vledder Museum, Vledder, Netherlands: Apesanteur

Studies fusing techniques with Udo Zembok in SarsPoteries, France

Van Der Togt Museum, Amstelveen, Netherlands: Apesanteur

Studies Venetian filigree and murrine techniques with Davide Salvadore in Pilchuck, Seattle, USA

Studies Venetian Battuto and Inciso engraving techniques at the European Research and Training Centre for Glass Arts (CERFAV) in Vannes-le-Châtel, France

Demonstration at the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, USA

Pioneer of the Kids Design Glass programme to raise awareness of glass art among children, through a partnership between the twin towns of Tacoma, USA, and Biot, France, at the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, USA

Artist residency at the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, USA

Owner and artistic director, Centre du Verre Contemporain, with both local and international reach

Arranging residencies for leading international artists at the Biot studio (Xavier Carrère, Gérald Vatrin, Andrew Erdos, Ethan Stern, Gabe Feenan, Raven Skyriver, Kelly O’Dell, Antoine Brodin, Rob Stern and Ondrej Novotny)

Demonstrations at Museo Dell’Arte Vetraria in Altarese, Italy

Kids Design Glass (see 2014)

Glas Museum, Lette, Germany: Eclipse

Museum Of Glass, Tacoma, USA: On the Rock

Explores neon and plasma techniques with Ed Kirschner at the Glass Factory in Boda, Sweden

Studies neon techniques with Jen Elek and Jeremy Bert at Urban Glass in Brooklyn NY, USA

2015 to date. Arranging residencies for leading international artists at the Biot studio (see 2015)

Demonstrations at Museo Dell’Arte Vetraria in Altarese, Italy

Pioneer of the Kids Design Glass programme (2014, 2015, 2017)

Demonstration at the Nijima Glass Art Center and Museum, Niijima Island, Japan

Co-founder and coorganiser of the first Biot International Glass Festival, in partnership with the association SO BIG and the town of Biot in France

Instructor at the National School of Glass in Moulins, France

Presentation during the Glass Art Society Conference at Morean Arts Center, St Petersburg, Florida, USA

Instructor at CERFAV in Vannes-le-Châtel, France; Instructor for the Hilltop Artists programme in Tacoma, USA; Instructor at the Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington, USA

Vestiges Contemporains , Musée d’Archéologie, Antibes, France

Altare Vetro Arte , Museo dell’Arte Vetraria, Altarese, Italy

Musée d’Archéologie, Antibes, France: Amphore Méditerranée, Vestiges Contemporains

Niijima Glass Art Center, Niijima Island, Japan: Apesanteur

Aujourd’hui et Demain , Musée & Centre d’Art du Verre, Carmaux, France

Glasmuseum, Lette, Allemagne: Ivresses, Colonnes Roseaux, Le Caire - Vestiges Contemporains

Glass Art Society exhibition , Morean Arts Center, St Petersburg, Florida, USA

Co-founder and co-organiser of the first Biot International Glass Festival

individual collective museum collections

Antoine Pierini and Friends , Glasmuseum, Lette, Germany

Le Guerrier Ombre et Lumière, Musée d’Art Classique, Mougins, France

Souffles de Verre , Musée du Verre, Claret

Glasmuseum, Lette, Germany: Colline, Vestiges Contemporains Immaculés, On the Rock, Apesanteur

Studies vitreography techniques with Silvia Levenson in Lago Maggiore, Italy

European Glass Context , Bornholm Art Museum, Denmark 2021

International Biennale of Glass , National Gallery, Sofia, Romania

Instructor at the Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington, USA

Co-founder and coorganiser of the first Biot International Glass Festival

2015 to date

Owner and artistic director, Centre du Verre Contemporain, with both local and international reach

Arranging residencies for leading international artists at the Biot studio (Xavier Carrère, Gérald Vatrin, Andrew Erdos, Ethan Stern, Gabe Feenan, Raven Skyriver, Kelly O’Dell, Antoine Brodin, Rob Stern and Ondrej Novotny)

En rêvant la Méditerranée, Villa Kérylos, Beaulieu-sur-Mer, France

Villa Kérylos

Impasse Gustave Eiffel, 06310 Beaulieu-sur-Mer

Opening hours: 10am to 5pm: January to April 10am to 6pm: May to August 10am to 5pm: September to December

Information and access: www.villakerylos.fr

T. +33 (0)4 93 01 01 44

Estimated length of exhibition: 1 hour. Guided tour. Audio guide. Giftshop and books.

The exhibition experience can be extended with a visit to the Pierini International Glass Art Center, 9 Chemin du Plan, 06410 Biot, T: +33 (0)4 93 65 01 14

The Centre des monuments nationaux is hosting the exhibition En rêvant la Méditerranée by Antoine Pierini at Villa Kérylos from May 8th to October 2nd 2022.

Glassworking first appeared in the eighth century BC and was documented by Pliny the Elder in his encyclopaedic work Naturalis Historia . The basic techniques have lived on and evolved since antiquity. Back then, however, the use of glass was generally limited to a few specific areas, such as jewellery (beads and bracelets) and tableware (jugs, bottles and dishes). Today, it permeates every aspect of everyday life and artwork.

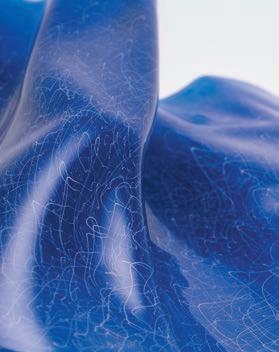

Antoine Pierini is a master glassmaker, designer and glass artist who uses his pieces—some of which he created specifically for Villa Kérylos—to tell a story that spans the sea, travels through time and weaves through life. In Villa Kérylos, his blue and rose glass amphoras—whether whole or in pieces—rub shoulders with their original predecessors, bearing witness to shipwrecks and the harsh hand of nature, elements beyond human control.

Elsewhere, amid an enchanting peristyle, bathed in dazzling light, the simplicity of the reeds urges deference, since only understatement, humility and measure can coexist with the dream of Théodore Reinach, the founder of Villa Kérylos. And even if Pierini takes risks in using neon lights and pieces that

reach for the heavens in the Library and Antiques Gallery, these flirtations never blind us in our search to discover where past and present begin and end. What better place than Villa Kérylos to embody the dream of artist, man and philosopher?

Threading through the installations with their combination of sound and visuals, we hear Homer intone the fate of men; we also hear the words of Albert Camus after his trip to Greece, when he wrote that his time in Athens was “like a single source of light I will cherish close to my heart”.

Pierini brings us personal emotions and singular stories by following in the footsteps of memory. Every piece tells a story and every story stems from emotion. We leave the exhibition feeling that the artist has kept his promise. We have dreamed of the Mediterranean and more. We have understood the words of Ithaca, perhaps the most well-known poem by the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy: “May there be many a summer morning when, with what pleasure, what joy, you come into harbours seen for the first time.”

—

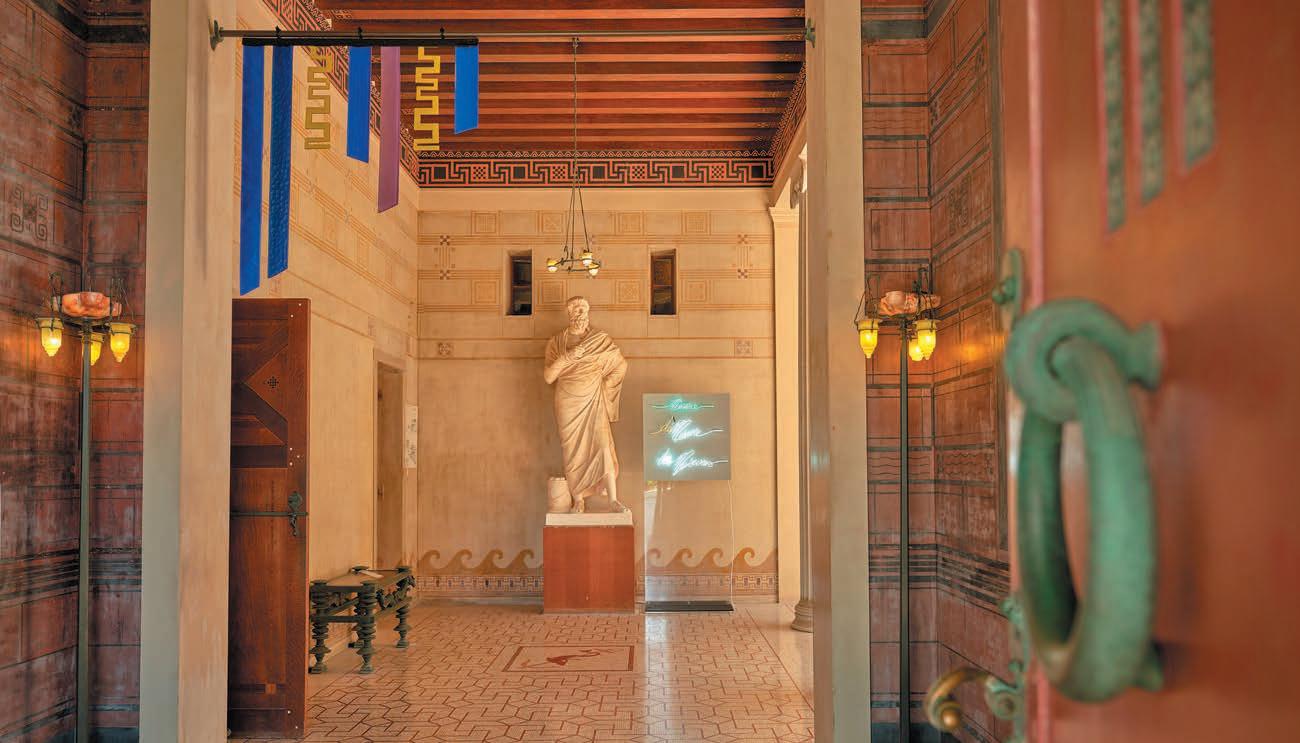

The tour begins in the villa vestibule with two symbolic works: La Ligne et l’Angle and Mesure.

Entrance Hall (Thyrôreion)

Entrance Hall (Thyrôreion)

La Ligne et l’Angle. Lines, real or imagined, are an underlying theme of the exhibition. Two meanders slip in between glass strips whose fates run parallel, only varying in length. Meanders are ornamental motifs common in Ancient Greece, perhaps reflecting the twisting nature of thought and the endless array of possible paths. Found at the start of the exhibition, this hanging piece invites visitors to weigh their sense of certainty before embarking on the journey.

Mesure. Here, we find a series of words flanking the statue of Solon, one of the founders of Athenian democracy: mesure (measure/moderation), démesure (immoderation/excess) and des mesures (measures). The neon writing echoes the line of thought espoused by Albert Camus in The Rebel: “Moderation, born of rebellion, can only live by rebellion.”

Collines

2022

24 sculptures in blown, engraved and solid glass 640 x 45 x 67 cm

In the Balaneion, a room dedicated to the naiads and a reminder of the ritual importance of water to wash and cleanse in Ancient Greece, the Collines undulate at the foot of the fountain.

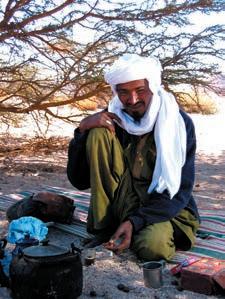

Collines. Pierini blew these abstract bubbles while dreaming of the desert dunes of Tassili N’Ajjer, creating pieces that also conjure images of water drops or cells, leading us to wonder whether they are littler or larger than their real-life counterparts. A mystery of scale that draws the mind toward both the immensely big and immensely small.

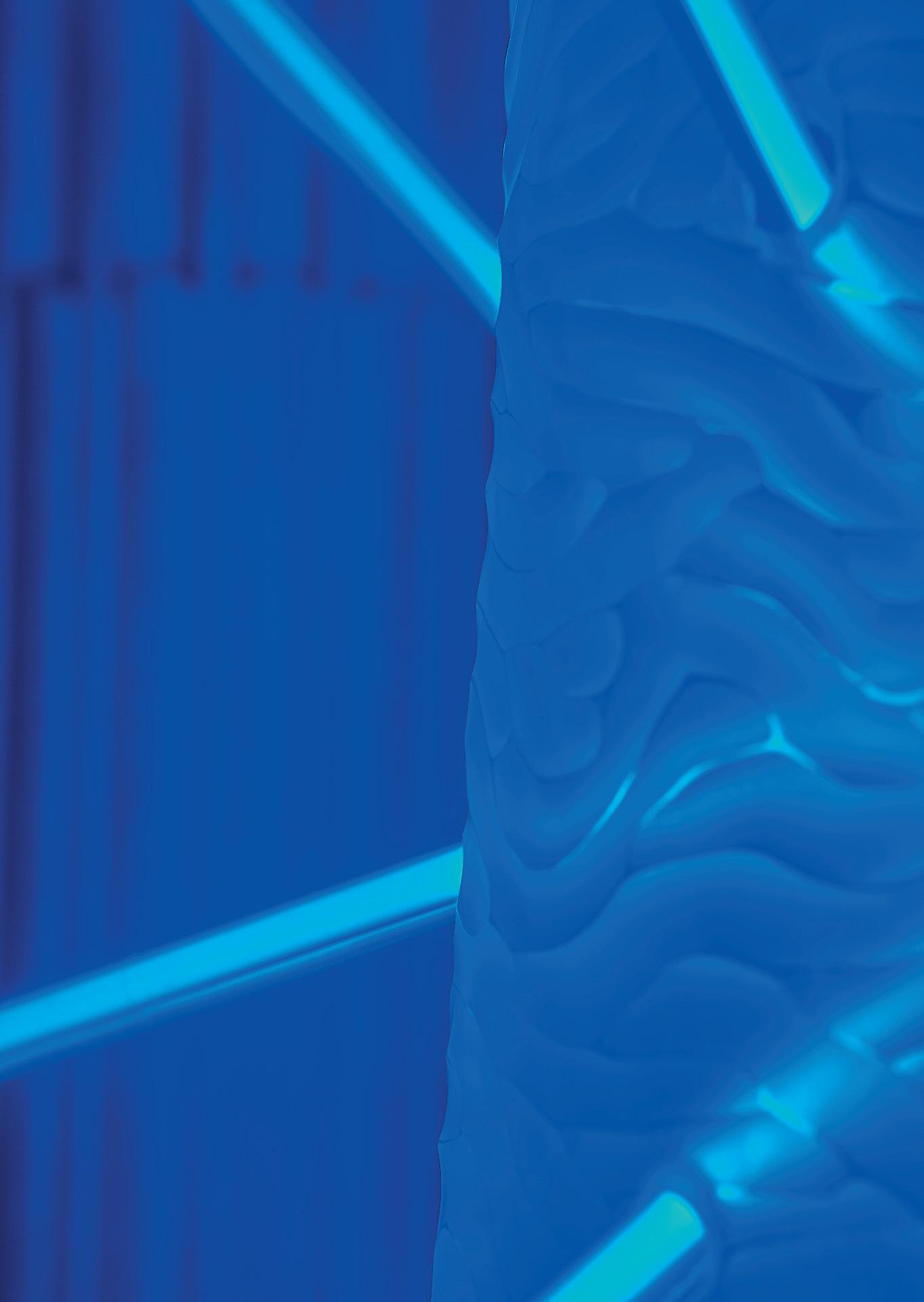

Installation of glass sculptures in blown and engraved glass forming seven columns, with brushed marine grade stainless steel

Courtyard (Peristyle)

Colonnes Roseaux 2022

100 x 60 x 590 cm

Courtyard (Peristyle)

Colonnes Roseaux 2022

100 x 60 x 590 cm

The Colonnes Roseaux rise up in the central courtyard, which formed the heart of the home in Ancient Greece—a peristyle through which air and light flow freely.

Colonnes Roseaux. Pierini sculpts nature into symbolic forms. His Colonnes Roseaux infiltrate the space of the Villa’s central courtyard with their primal plant-like architecture. These increasingly refined volumes are a tribute in glass to Constantin Brancusi’s “Endless Column”. They are a link between interior and exterior, between people and their surroundings, a correspondence conveyed by Le Corbusier. They stretch for the sky in alternating lengths and colours that embody a delicate deference. These peaceful-yetpowerful plants also stand tall in the quiet contemplation of the Relaxation Room (Triptolème).

Installation of glass sculptures in blown and engraved glass forming seven columns, with brushed marine grade stainless steel 100 x 60 x 590 cm

The east-facing library, so conducive to work in the early part of the day, is the most spectacular and imposing room, with walls one and a half floors in height. The Haute Lumière sculpture finds its place above a superb chandelier inspired by its Hagia Sophia counterpart in Constantinople (Istanbul), while the Galets Côte d’Azur sit mischievously on the shelves among classical pieces collected by Théodore Reinach himself.

Haute Lumière. From below, the neon lighting is reminiscent of lightning, perhaps not surprising given that obsidian, a natural glass, is created by the impact of a lightning bolt. Haute Lumière , both literally and figuratively, urges a detached perspective, since the intent is not to worship idols any more than works of art.

Three sculptures in engraved and sculpted glass

Galets Côte d’Azur. Pierini has placed small glass pebbles in the display cases housing the archaeological collections of Théodore Reinach, reflecting the natural bond between summit and sea. Mountain rocks travel over time in the tumult of torrents to end their days as pebbles on our beaches. A long journey that sculpts a rough-hewn rock into its calmer counterpart.

Installation comprising seven amphoras in blown glass on stainless steel supports, sound and video 250 x 72 x 155 cm

—

In the Amphithyros, a small antechamber watched over by Athena Lemnia, visitors are plunged into an immersive audio-visual experience: L’Objet du Voyage

L’Objet du Voyage. In stripping the amphoras of their utility-based purpose and replacing the opacity of clay with the luminosity of glass, Pierini has dreamed up a series of sculptures he calls Vestiges Contemporains . Inspired by the amphoras of antiquity, from Cycladic creations to their Byzantine counterparts, he has crafted pieces that resemble human figures. Here, they come to life through a video projected on their body in a moment of introspection ranging from quiet sea to stormy skies. These same sculptures also grace other parts of the exhibition (Oikos and Hermès Antechamber).

Installation comprising seven amphoras in blown glass on stainless steel supports, sound and video 250 x 72 x 155 cm

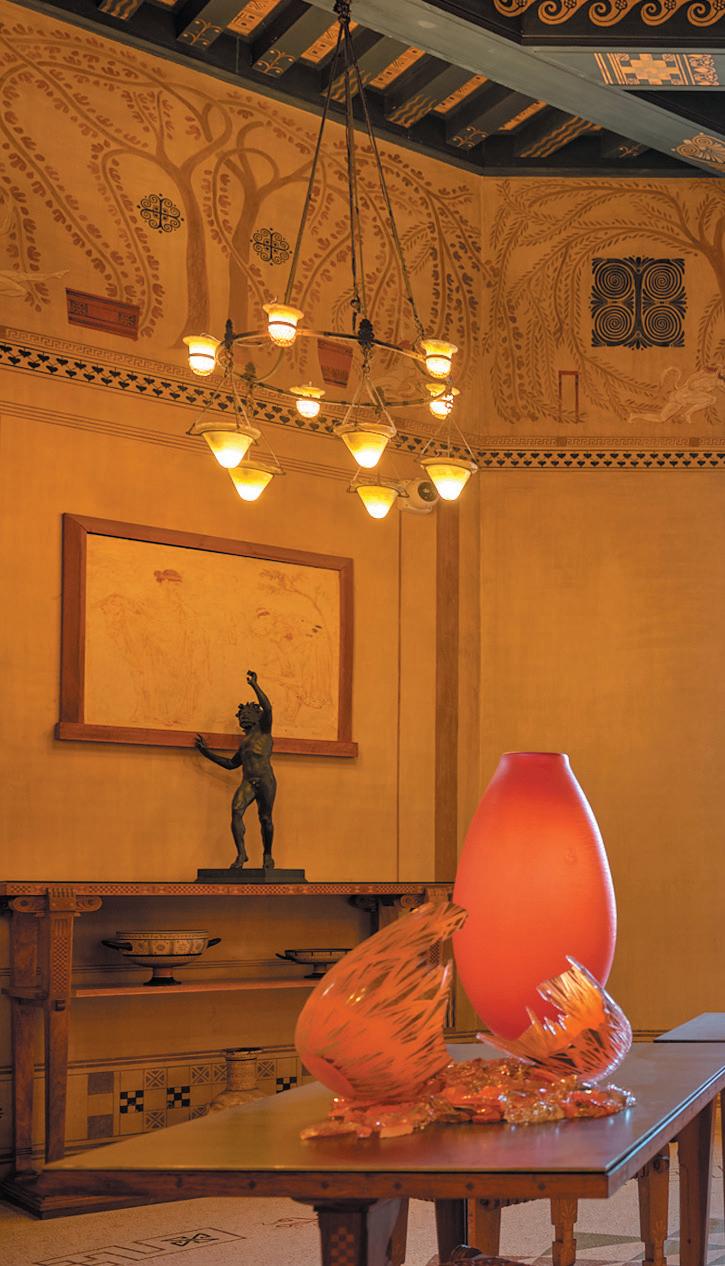

The installation Après la Bataille unfolds in the Triklinos, or three-bed room, evoking the ancient art of banquets.

Après la Bataille. After the war between men comes the war of the senses, those excesses of reason akin to inebriation of the soul. These are the themes that inspired the meeting of these three works. Pierini poured molten glass into the amphoras as if it were oil or wine, causing them to explode.

Après la Bataille 2022 Installation comprising three amphoras in blown and exploded glass

Arbres Repères 2022

Sculptures in glass, stainless steel and stone

40 x 40 x 348 cm

40 x 40 x 223 cm

40 x 40 x 160 cm

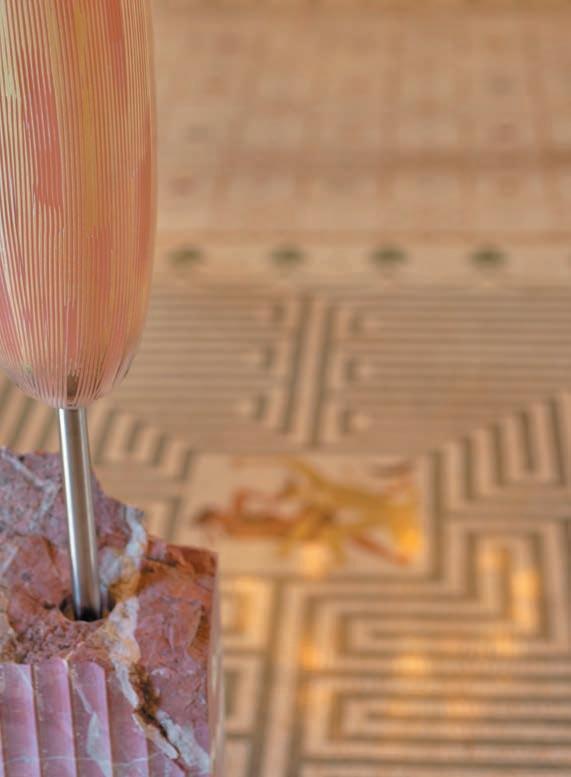

Arbres Repères rise up in the Andron, a large salon used for entertaining male guests, which at its centre features a mosaic representing the labyrinth in which Theseus kills the Minotaur.

Arbres Repères

2022

Sculptures in glass, stainless steel and stone

40 x 40 x 348 cm

40 x 40 x 223 cm

40 x 40 x 160 cm

Main salon (Andron)Arbres Repères. When the remnants of temples leave still-standing pillars, nature often reclaims the chaos. The marble bases provide the foundations for these elongated creations redolent of the cypress, a tree symbolising immortality now found all around the Mediterranean. Here they stand around the labyrinth, but also rise up outside in the villa gardens looking over the sea. Totemic creations, like the milestones on a journey that rejects material barriers and the borders imposed by humans.

—

A Vestige Contemporain finds its place in the Oikos, a smaller salon reserved for family use, in which theatre masks adorn the walls.

Vestige Contemporain. Part of a large collection of anthropomorphic amphoras created by Antoine Pierini, featuring distinctive colours and materials. The handles are reminiscent of ears à la Max Ernst. This sculpture is a nod to the antique amphoras found in the library and the Triklinos.

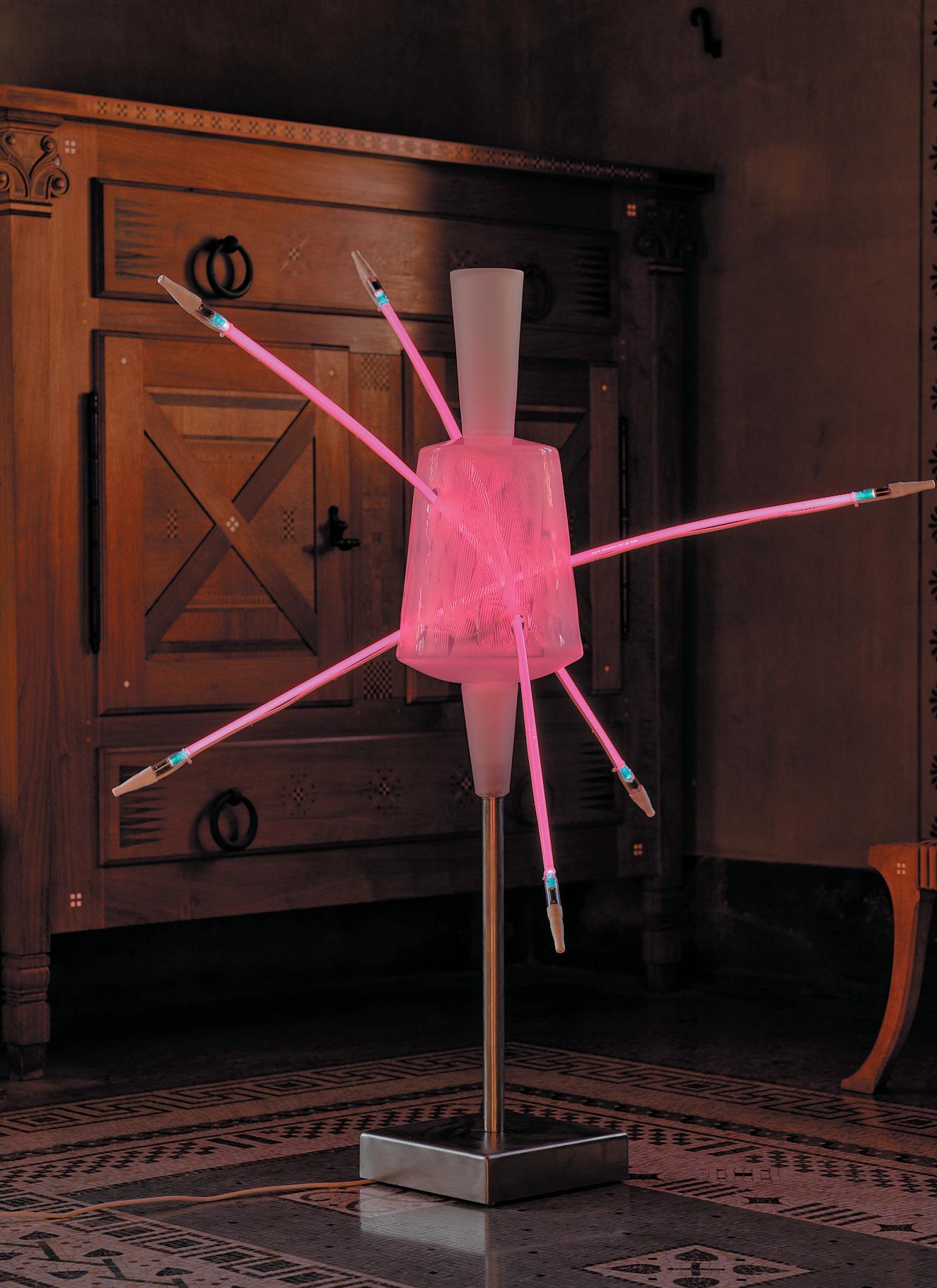

The first floor houses the apartments, where we find a sculpture from the Lumière Intime series in Madame Reinach’s bedroom, dedicated to Hera. Midnight-blue frescoes add a particularly soothing touch..

Lumière Intime.

“Inanimate objects, do you have a soul?” wondered the French poet Alphonse de Lamartine. Family cultures and Mediterranean influences converge in the belly of this sculpture, which has a twin in Mr Reinach’s bedroom (Erotès). Amphoras, terracotta vessels with no initial value, take on a life of their own in glass and are transformed, magnifying Pierini’s focus on light and form. Suggestive of a human body or perhaps a bobbin, they also bring to mind the patience of Penelope as she knitted while awaiting Ulysses’ return.

Blown and engraved glass amphora with neon and stainless steel 95 x 185 x 164 cm

Relaxation Room (Triptolème)

Colonnes Roseaux 2022

Installation comprising blown and engraved glass sculptures forming three columns, thermo-lacquered steel

11 x 28 x 150 cm

As in the Peristyle, the Colonnes Roseaux rise up in the small relaxation room, which owes its name to a mosaic representing Triptolemus, the hero of Eleusis, on a chariot. Under the aegis of the demigod who taught men agriculture—thus giving them the key to civilization—the room’s walls are adorned with natural illustrations that create a link between ancient and modern times.

Colonnes Roseaux. Suggesting stability, these glass plants thrive in the most private parts of the villa, on the first floor, exploring the scope for cohabitation.

Pensée Tiède. The concept of Pensée de Midi (often translated as “Thought at the Meridian”) ardently opposes extremes but is by no means a Pensée Tiède , or “tepid thought”. This tongue-in-cheek bathroom installation shows the glass streaming towards the plughole, like lukewarm souls slipping into the wings of life’s great stage.

—

In this room, dedicated to Eros, the god of love, Lumière Intime diffuses its rays of light surrounded by Pompeii red frescoes.

Lumière Intime 2022

Amphora in blown and engraved glass, neon and stainless steel 105 x 75 x 118 cm

Mr Reinach’s bedroom (Erotès)

Lumière Intime 2022

Amphora in blown and engraved glass, neon and stainless steel 105 x 75 x 118 cm

Mr Reinach’s bedroom (Erotès)

Mr Reinach’s bedroom (Erotès)

Mr Reinach’s bedroom (Erotès)

Lumière Intime. Here, the glass invites us to look beyond our contradictions, bridging the gap between Ancient Greece and a resolutely contemporary design. The fuchsia pink echoes the blue in Madame Reinach’s bedroom. Once again, neon lights intersect in the body of the work, just as the villa is permeated by other pieces.

The journey continues outside, in the garden surrounding the villa, which boasts a balanced blend of Mediterranean plants, along with Arbres Repères and Collines

Collines 2022

Installation comprising 29 sculptures in blown, engraved and frosted glass

440 x 53 x 69 cm

Arbres Repères 2022

Sculptures in glass, steel and stainless steel

80 X 80 x 345 cm

60 x 60 x 341 cm

80 x 80 x 380 cm

Arbres Repères. These three pieces in glass and stone stand like a temple stripped of its fourth column, gazing towards the Mediterranean horizon. Evoking the emphasis of Matisse and Ellsworth Kelly, their simple, colourful plant-like form is outlined against the landscape, questioning the concept of borders and territories.

Arbres Repères 2022

Sculptures in glass, stainless steel and stone

80 X 80 x 345 cm

60 x 60 x 341 cm

80 x 80 x 380 cm

Collines 2022

Installation comprising 29 sculptures in blown, engraved and frosted glass

440 x 53 x 69 cm

Collines. The glass appears to have bubbled up from the garden gravel, assuming the steady sway of sundials in a peaceful undulation of concave and convex shapes.

Installation comprising 29 sculptures in blown, engraved and frosted glass 440

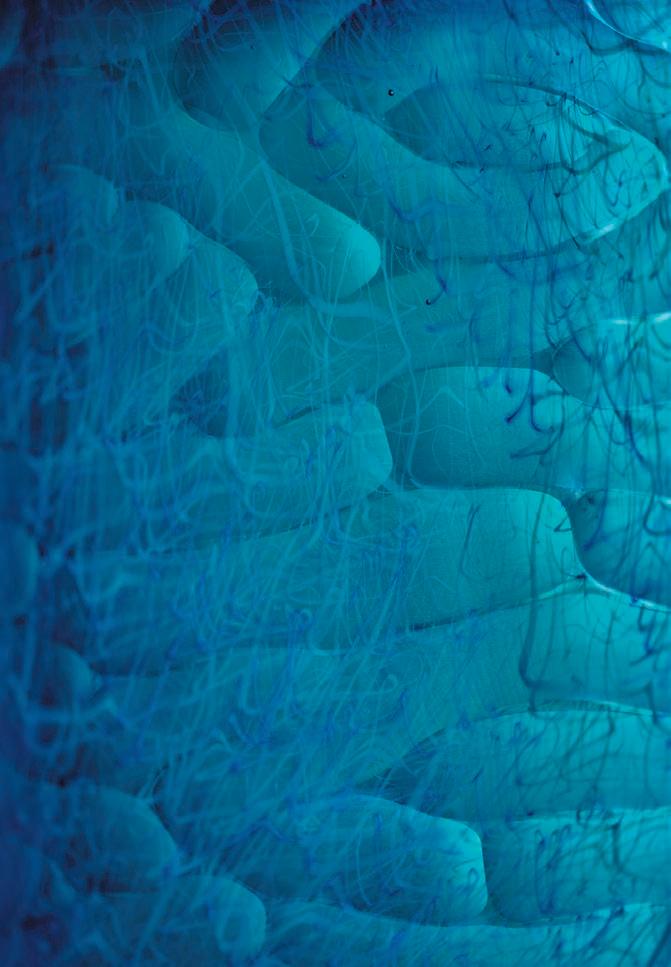

Mer Intérieure

2022

Installation comprising 130 pieces of sculpted, etched and frosted glass 430 x 140 x 305 cm

—

Down below, Mer Intérieure flows into the Antiques Gallery, looking onto the sea, featuring casts of Greco-Roman statues on the old customs trail that runs under the villa.

Installation comprising 130 pieces of sculpted, etched and frosted glass 430 x 140 x 305 cm

Mer Intérieure. This brings us to the apotheosis of glass art, with an installation that unfolds in waves. An inner storm. A sea of emotions. A birthplace of tragedy and drama that nonetheless brings hope. Mare internum , a name given to the Mediterranean Sea in the Classical World. In this untameable expanse, rebellion is the movement of life. This melange of glass and motion embodies the words of French poet Charles Baudelaire: “Free man, you will always cherish the sea.”

On entering Villa Kérylos, visitors are immediately greeted with two words written in neon letters: mesure (measure/moderation) and démesure (immoderation/excess). “Man is the measure of all things,” claimed Protagoras, providing an aphorism that has since become a humanist maxim. For Pierini, however, humanism is rooted in revolt, rebellion, in the sense conveyed by Camus. “Rebellion in itself is moderation, and it demands, defends, and recreates it throughout history and its eternal disturbances.” Mesure is not the Pensée Tiède found in the first-floor bathroom, where hot and cold flows form “tepid thought” that glimmers weakly before disappearing down the plughole of a heavy marble bathtub. With Pensée Tiède, Pierini has created a deliberately ironic, insipid piece that dims the presence of light and colour. Nothing could be further removed from tepid thought than the sense of measure or moderation kindled by Camus: “Moderation, born of rebellion, can only live by rebellion. It is a perpetual conflict continually created and mastered by the intelligence.” The creative

conflict embodied by mesure and démesure is immediately apparent in the entrance hall and forecourt. La Ligne et l’Angle sets the tone with its varying lengths of thick, bevelled blue and mauve glass strips that contrast with meandering lines inspired by the friezes found throughout the villa.

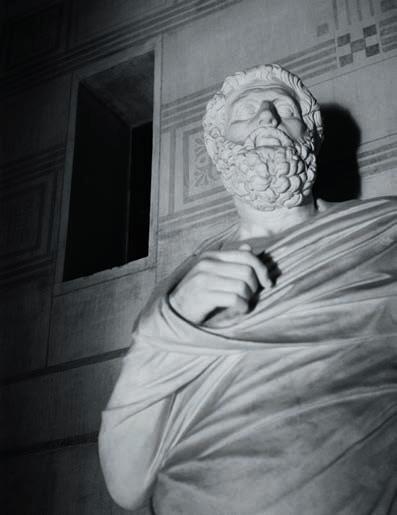

Visitors then encounter the replica of a statue now held by the Vatican Museum in Rome. A century ago, Théodore Reinach, the man who designed Villa Kérylos, felt it represented the Greek poet and politician Solon, even though it is typically taken to represent Sophocles. Irrespective of which historical figure the work embodies, the key is the concept of mesure The three words emblazoned in neon urge us to consider the “metron”: mesure in blue, which then morphs into démesure and des mesures in white. These words resonate with Solon’s own actions in early sixth century Athens, when the legendary founder of Athenian democracy declared, “I made the laws equal for the poor man and the powerful, ensuring impartial justice for all.”

Visitors will then need to venture further into the villa to reveal the ripples of immoderation and violence, featured by the artist in symbolic pieces. Après la Bataille is one example. On display in the dining room (Triklinos), it comprises a large orange vase, reminiscent in shape of the containers made by Biot potters until the end of the 20th century, alongside which we see the broken remains of two other vases lying on antique tables chosen by Reinach himself. Pierini poured molten glass into each, causing them to explode. The remnants were then captured in cooled translucence, conjuring the image of glass pooling from the broken vessels, as if oil or wine were flowing from amphoras.

We are all of course free to interpret the symbolism in our own way. Yet we cannot help feeling that those fragile glass pieces sitting atop the Triklinos tables somehow evoke human interaction and burgeoning trade throughout the Mediterranean. The broken amphora is also indicative of the violence of people indifferent to its fragile beauty. People unable to communicate, dialogue or build the commonality of shared culture. These objects destroyed by the molten glass symbolize immoderation and excess, or a “non-Mediterranean mindset”, to paraphrase Camus. In the face of Greek measure and moderation, immoderation and excess engender conflict, catastrophe and death: these three vases, with their simple shape and form, weave a tale of tragedy.

Born of fire, opaque or translucent, glass either blocks rays of light or allows them to pass through. The work of glass artists reflects the ongoing dance with light and its effects. Pierini combines the play of light with meaningful focus on its symbolism. He sees the library as an essential part of Villa Kérylos: representing the humanist culture and the light of reason. This vast room is sparsely furnished with two work surfaces, closets and shelves that hold books

and antiques. Théodore Reinach designed the library as a haven of peace and meditation, as reflected in the Greek wording found on the walls of the room: “Here, among the orators, sages and poets, I delight in the quiet of eternal beauty.”

In these soothing surroundings, Pierini sought to capture the flood of sunlight striking the reader. On one of the medallions below the mezzanine, we find the names Plato and Aristotle side by side. Nearby, Pierini has hung two words in neon: Haute Lumière (high light). Here, overhead in the library, these words hint at the power of lightning, both creative and dreadful. The imagery is reminiscent of the thunderbolts wielded by Zeus to smite Prometheus and the rebellious titans—an association that has clearly not escaped Pierini. Drawing on his fascination with lightning, the artist chose to work with fulgurite, a natural, non-transparent glass formed when lightning strikes sandy ground.

Pierini also has Albert Camus’ The Stranger in mind here. Haute Lumière is reminiscent of the intolerable solar burden bearing down on the story’s protagonist, Meursault, at that fatal moment in time when he encounters “the Arab” on an Algiers beach in su ff ocating heat, under that burning sun. The sunlight that strikes and blinds Meursault is seen as a hostile presence: Apollo, the god of light, music and medicine, is also a god with a knife, a merciless deity who drives Oedipus to blindness. How could we not think of Sophocles, whose name figures on another medallion in the library, opposite Haute Lumière? When Oedipus unearths the awful truth, the cause of the plague that is ravaging the city of Thebes, he pierces his own eyes, preferring eternal blindness to the sight before him. In The Stranger, Meursault, accused of murder, is also condemned without ever really understanding the motive for his actions, seemingly driven solely by solar fate. Haute Lumière thus evokes a sense of power that contrasts with the moderation and tranquillity sought by someone reading in the library. Pierini’s neon emits a light that is more tragic than comforting.

Light and sun do not convey the same dysphoria in L’Objet du Voyage, the installation found in the Amphithyros, between the library and the Triklinos. Pierini has created nine translucent and opaque glass vases using different techniques, including merletto, invented by a 20th century glassmaker from Murano, Italy, which involves interweaving glass threads in a pattern akin to lacework. These vases, inspired by the amphoras of antiquity, conjure images of peaceful trade between the peoples of the Mediterranean.

However, although glass is historically tied to everyday applications, Pierini has liberated these pieces from the yoke of utility and turned them into what he likes to call “living” sculptures. In sculpting glass by weaving the magic of materials and light, he gives another nod to his favourite author, Albert Camus, who wrote in The Rebel that sculpture is “the greatest and most ambitious of all the arts”, an art that seeks to stylize gestures and movements, to “imprison, in one significant expression, the fleeting ecstasy of the body or the infinite variety of human attitudes”. In L’Objet du Voyage, each vase, with its handles, neck and curves, takes on the appearance of a statuette whose opaque whiteness evokes the colour of archaic female figurines.

The amphora sheds its erstwhile status as a container designed to carry oil, wine or grain, and instead takes on the dignified pos -

ture of an ancient idol, conjuring the memory of pre-Hellenistic art and the Cycladic figurines of the third millennium BC. Pierini has described L’Objet du Voyage as an immersive piece, yet it also symbolizes travel: these objects that seemingly transcend space and time bring to mind a fleeting glimpse of those fateful migrations to which the Mediterranean all too often bears witness today.

Galets are pieces of glass art scattered across the shelves of the library, among oil lamps, vases and Tanagra statuettes. Their full, rounded forms and dark hue give them the look of soft, shiny stones that appear to have been hand-polished, or are perhaps pebbles smoothed by the sea over millions of years. They reflect the immemorial ages of humanity and the action of time, which, through erosion, patiently lends the pebbles their patina. Their warm roundness woos the hand, imparts the urge to touch them and feel their smooth or granular texture, as if the tactile sensation could reveal to us the reason for their mysterious presence among the remnants of antiquity that Théodore Reinach collected in his time.

Like Galets , the organic Collines form two groups with an imposingly enigmatic yet reassuring presence. An initial cluster sits in the Balaneion, near the entrance to the villa. There, the harmonious and homogenous colours of Collines (mauves, blues and pinks alternating

with translucent and gold pieces) line the two sides of the pool, creating an angle with the fountain at its apex. These works—with a soft roundness in keeping with the curves of the pool and the niche—carry special meaning for the artist: they suggest the fertility and fecundity of nature through their feminine form. The other group is installed outside on the rocky ground near the garden. These pieces are reminiscent in form of shells, eggs or rocks, and have been arranged in a straight line. The irregular contours of the organic Collines counter the right angle formed by the two white walls, which tower over these little multi-coloured, fragile objects nestled on the villa floor.

Pierini drew inspiration from Brancusi’s Endless Column and Bird in Space to create Colonnes Roseaux, which imitate bamboo and rise up to six metres in height. They stand in the centre of the villa, opposite an Oleander, sparking a dialogue between vegetable and mineral. Colonnes Roseaux are made up of modules akin to the drums used in classical columns. The circumference of these modules, at the join, is based on the size of the fluting on the Doric columns used for the peristyle. The verticality of Colonnes Roseaux matches that of Arbres Repères , which imitates an emblematic Mediterranean tree: the cypress. These arboreal landmarks stand between two and four metres tall and are a tour de force, testament to the technical prowess of the artist: Pierini created pieces over a metre in length, pushing the glass bubble on the end of the blowpipe to its very limit. The stones used for the base come from various sources, including Spain, Egypt, Greece, Tunisia and Italy, symbolizing the shared heritage of Mediterranean cultures.

The glass trees—at once both fragile and resistant—and Colonnes Roseaux attest to Pierini’s fascination with all forms of transformation enabled by glass, midway between vegetable and mineral. These transmutations are particularly evident in Mer Intérieure, a piece

created especially for the Villa Kérylos Antiques Gallery. The monumental sculpture features a huge glass mosaic that embraces intuition, turning liquid into solid. It captures the movement of a wave as it surges in through a window and rises up in the gallery to form a huge curve. The many cobalt, ultramarine, midnight and purplish blue hues lend the piece a bright, iridescent look, like the sea. Through this combination of abstract components, Pierini has captured the instant when the wave threatens to bring its full force to bear and swoop down on us. Mer Intérieure, attached to a bare stone wall, reflects the wonder of the Mediterranean, so dear to the artist, with its crossroads of cultures. A tragic, violent, solar sea enclosed by land.

The following is an extract from an interview with Antoine Pierini conducted in March 2022 by the art historian and glass specialist Manuel Fadat. It covers the inception of Antoine’s career and the family glass business, and explores the path he has followed since, including the works, accumulations and installations he now produces and presents in museums around the world, and most recently in his home region, at the Museum of Classical Art in Mougins and at the current exhibition in Villa Kérylos.

— Manuel Fadat: Hello Antoine. I think we agree that this sort of interview, or rather conversation, is a good way to contribute to the history of glass art in that it offers an insight and explores a message, a thought, a feeling, while at the same time providing some frame of reference in terms of space and time. Perhaps I should start by confessing I know relatively little about your work, which makes this all the more thrilling for me because we’re about to dive in and no doubt highlight a number of aspects that will interest everyone: inquiring minds, enthusiasts and experts alike.

I’d like to find out about how you got into art, along with your approach, your underlying concerns, your aspirations, your inspirations, your symbolic, poetic and political messages, and your creative and aesthetic processes. We can obviously draw parallels with other artists, both past and present, and I imagine we’ll touch on a few influences, inspirations, tributes and quotes. I may be a little quick off the mark here, but I couldn’t help seeing a hint of Harvey Littleton, Xavier Carrère and William Morris, and

the glassmakers of Murano. And that is in no way a value judgement. Quite the opposite, in fact.

What I do know about you, is that, while you may not be a Bacchus born of Jupiter’s thigh, you are a boy from Biot, a place that boasts its own special glassmaking history—one in which the Centre du Verre Contemporain has played an integral part for two generations. A lot of people in your family have caught the glassmaking bug. I also know you are very active, engaged and proactive in the glass scene, and that you host and take part in a lot of events. I know you do your part for the glass community by supporting artists and residencies, not to mention the fact that you seem to be travelling more and more to the United States for training and exchanges.

Before we began this conversation, we briefly discussed your work, and a few key words stuck in my mind, which I’ll like to recap now. We talked about the fact that you are particularly interested in unembellished forms as a means of exploring the essence of things, as well as movement, material effects, accumulation and monumentality, and you work through the

back to the beginning: the studio glass movement

association of ideas you want to convey. Your work often carries a raft of references, revelations, phenomena and feelings, which express your way of thinking. You strive to be less “conceptual” and instead aim to harness powerful concepts or notions, such as humanism. We also talked about the fact that you have a real interest in (and perhaps even a fascination with) antiquity and the Mediterranean, which is something reflected in your Vestiges Contemporains, which you are showing at Villa Kérylos. In short, we have a lot to talk about!

Let’s start with a fairly open-ended question, focusing on the origin story. How did you get where you are now? How did you end up where you are today?

— Antoine Pierini : First off, I like that you aren’t familiar with my work in any great detail. That gives us a perfect opportunity to delve deeper and get more granular. As for the political side of things, that’s something that resonates throughout my work but which I prefer to evoke rather than tackle head on. I like situations that kindle curiosity and make people think. I prefer to give pointers then leave it up to each person to create their own dialogue. Which brings us to the references you mentioned, whether through connections or kinships. That’s something I approach with a great deal of humility. As for the conceptual aspect of my work, I definitely do look to strike a balance between idea and form. And, last but not least, you’re right about the glass community: I try to move things forward and encourage sharing. I feel it’s my duty. But to get back to your initial question, I think you asked me how I got where I am today, is that right?

— MF: Right. I’d like to hear your take on the history of glass in Biot, what the place was like when you started out, what got you hooked. What made you want to learn more and make it your career. How you ended up where you are now. How it all started.

— AP: We all basically followed in the

footsteps of Eloi Monod. We’re all connected to what he started, one way or another. The great thing about him is the way in which he revolutionized the way we work in the studio and the way we present our profession. He opened up the hot shop to the public, simply because glassmaking is an amazing process to behold. But the most important things are the changes he made within the workshop itself, by breaking away from traditional methods of production. My uncle Jean-Louis Fayard, who ran Eloi Monod’s glassworks, completely changed the production line and its division of labour, which was no doubt initially introduced to safeguard expertise and keep techniques under wraps—a context that created a hierarchy and skewed the balance of power. He introduced a system of production bonuses to motivate workers, but there was no hierarchy tied to expertise.

— MF: This is a story that also includes your father and your uncle, Alain Bégou.

— AP: Yes, my father and my uncles, plural! Robert Pierini, Alain Bégou and Jean-Louis Fayard, who ran the Biot glassworks then set up the Verrerie d’Allex, which built a reputation for its focus on humanism and social issues.

— MF: How did they get into glassmaking in the first place?

— AP: I don’t really know who the instigator was! [ Laughs .] Jean-Louis was in charge of the Verrerie de Biot, Alain came to work on the gas system, since that was his background, and my father came in later as a “composer”—or chemist, if you will—before turning his hand to blowing.

— MF: Your father also worked with Lino Melano, from what I’ve heard, the mosaic painter for Fernand Léger and Chagall, among others.

— AP: That’s right, Lino Melano.

— MF: That’s when your parents opened

the Pierini studio then the gallery of the same name, the year you were born, in 1980. You might say it’s in your blood.

— AP: Totally. As a kid, I grew up surrounded by exhibitions and glassmakers. My parents carted me around among boxes and pieces. I slept under the table when there was a private viewing. I saw the work of glassmakers, I hung out with the children of other glassmakers, I listened to artists interact, talk about their work, create pieces, build furnaces and try out new ideas. Then I started making my own marbles, which I would take to school to play with, and which I often lost! There was a healthy dose of pride in all that, of course. I tried adding leaves of gold and silver. That’s how I first picked up the materials. For fun. To play with them. After, that, I began making paperweights when I was about 12 years old, which I continued to do until I was around 18. At the age of 15 or so, I dabbled in making a few vases and bottles, but it was still really slow going. I was more comfortable with the paperweights, which gave me my first taste of sculpture.

— MF: When you were learning the trade from your father, were you trying to copy him or did you already feel a need to experiment?

— AP: A bit of both. When you work with and for someone, you follow their lead, but at the same time, you want to try new things. And because he let me indulge my childhood curiosity with the paperweights, I already had a taste for adventure… You might start out by copying, but you already hear the call. We had a friend who worked as a waiter at Les Arcades (a hotel and restaurant in Biot). He was an intellectual and he loved glass. Whenever he had the time, he would come round to test ideas at the nearest available workbench. Before I decided to really learn the trade, we conducted experiments and came up with different forms and chemical compositions, using leaves of aluminium and brass. I didn’t know who Marinot was at the time! I just followed my instincts at

first. But one of main things I should point out about that particular “learning process”—and something that makes me who I am today—was the importance of travel. We took a road trip to Italy when I was seven to find the village where my grandfather was born. When we got there, we looked at the civil register and realized it was somewhere else, so we hit the road again between Tuscany and Umbria. That was an amazing time.

— MF: So, you’re actually an Etruscan! [Laughs.]

— AP: Yes! [ Laughs .] At any rate, the name Pierini comes from that region. But we also went to Rome, Naples, Herculanum and Pompei. Then, we took a second trip to Greece, where we visited Athens, and we covered all of Crete. I was awestruck. My mother took me to archaeology museums and I didn’t want to leave. I was fascinated by the design of the vases and other pieces. I’ve always been interested in antiques, archaeology and history. That’s why I loved the work of William Morris, which I discovered when we went to Seattle, and why I was later captivated by the power in Arman’s work.

— MF: How old were you? And why exactly did you go to Seattle?

— AP: I was 15. It’s a funny story. It started when some American glassmakers came to Biot and visited the workshop. They got on really well with my parents, even though my folks didn’t speak English very well. Mark Eckstrand was one of the first, then there was David Bennett, who went to study under Pino Signoretto in Murano and stopped in Biot on the way back. Unfortunately, he and his wife had all their belongings stolen, so my parents put them up and lent them some money, so they invited us to visit them. And we stayed a month. That was when everything fell into place. I discovered Dale Chihuly, we visited the Boathouse, and, as I said, I fell in love with the work of William Morris, especially his Canopic jars with the heads of doe and deer, and his vases showing scenes from prehistory. It was my first time in the United States and I was all about the American dream. That was the time of Michael Jordan, hip hop…

— MF: So, was it this sudden cultural awakening that made you decide to become a glass artist?

— AP: You could definitely say the trip triggered something.

— MF: This next question is on a bit of a tangent, but I feel it’s a natural follow-on. At that age, did you have more of an affinity for the work of Morris, Chihuly or your father? Or did you want to encompass everything?

— AP: I had my preferences. I was really impressed by the monumentality of Chihuly’s work, but I felt that what Morris was doing was remarkable. There’s something unprecedented about his work. He has a way of presenting things. There’s a certain poetry to it. He’s an artist with a vision who brings a team of creators with him. It’s wonderful. There’s something very humanist and universal—two concepts I try to convey in my own work. He tackles powerful themes. He’s worked on figuration, abstraction and light, and his work has a really strong presence. I also do my utmost to push the envelope in creating and sharing.

— MF: You give part of your earnings back to the glass art community. A noble commitment. Is that because you feel it’s important to actively contribute to dynamizing glass art and helping it grow?

— AP: Exactly. Inviting artists, sharing art, providing opportunities to create … It’s an incredible community. I’ve been to some amazing places, I’ve met people who are equally amazing, and I’ve always been made to feel welcome. I think the people who make up our community have really made some life choices. They are committed to their passion. Broadly speaking, we all face very similar challenges. That’s why there’s such a bond between people in the glass community. Sadly, we no longer have the time to stand idly by.

— MF: You mentioned the environment, so let’s talk a bit about Francine, your mother, and her commitment and influences.

— AP: The older I get, the more I realize what a big part she has played in my life. She gave me a taste for culture, civilization, antiquity and humanism, not to mention a love of nature. She grew up on a farm in the mountains of the Drôme region, in southeast France, surrounded by nature. She lived through the Second World War. Her parents fought for the French resistance. My mother is the embodiment of nature and

resistance. That’s a mindset I grew up with. She belongs to 16 associations that work to protect the environment, sits on 11 boards of directors, and is a curator for CEN PACA, an organization that works to protect flora and fauna throughout the south of France. She has had 182 hectares of land in Biot and Villeneuve-Loubet protected under the Natura 2000 initiative. She fights for air and water quality. And she’s determined to have an outstanding archaeological site in Biot listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There’s an old supervolcano below our feet here, so the substrate holds a wealth of hidden geological treasures. She even got me my membership cards! I follow all of this really closely. I keep an ear to the ground and we talk about it. It concerns me and affects me deeply.

— MF: That’s something that really shines through. Especially when you’ve met Francine! I don’t know whether you realize it, but it filters through and permeates your work on every level! She connected you and allowed you to hear the upheaval and the ups and downs in the world, as well as the mysteries of nature!

— AP: You mention mysteries, which makes me think of some sort of pagan spirit. Which makes sense, I suppose. My mother is like a witch. She watches over nature. She’s connected. She has some sort of gift

— MF: That’s a wonderful way to put it. But let’s get back to the younger you. You have the resources: the studio and the gallery. You’re about 20 years old. The bedrock is there. There’s something in the air. You have influences and references. You don’t yet have a huge amount of perspective. But you make up your mind. You go for it. You push on. You make progress. You explore… Can you tell me more about that transition from the day you decided to take the plunge and day you chose to pursue the gallery adventure?

— AP: I started by becoming my father’s assistant. I’d always seen him make massive sculptures, back in the eighties, in addition to making decorative art. But for more than six months, he didn’t make a single piece. He spent all his time teaching me, guiding me, pushing me hard, helping me. I worked on pieces to perfect my technique and I eventually produced my own work. That’s how I ended up with my first exhibition in a gallery in Cologne, in 2001. I sold nearly everything, which gave me my start and made me want to carry on. Then I worked with my father over the next few years, each time doing more and more, to the point where I knew how to make nearly all of his pieces and could do almost everything he was able to do. At the same time, he gave me more and more time to pursue my own research and exploration. He taught me how to learn “by ear”, like some of those Flamenco guitarists. He helped me develop my feelings, my instincts, even when I had lingering questions. But there were still a lot of things I wasn’t necessarily doing well when starting out on a piece, which I realized when I went to Pilchuck in 2010.

— MF: So, you went abroad to polish your training. That must have been an amazing trip. Was that the first time you had studied somewhere else?

— AP: Yes and no. I had also been to Sars-Poteries, in northern France, for a course in fusing and casting with Udo Zembok and David Reekie. That was really interesting. But in the United States I felt a special energy. I felt lifted, supported, connected.

— MF: What sort of pieces were you creating back then?

— AP: They were decorative pieces, inspired by nature, landscapes and floral patterns. Then, in 2002, I started working on larger sculptures, drawing on intuition and exploring with fairly aggressive cuts into a sensual block of glass. I liked the idea of contrasts and abstract sculptures. Then, for a whole period, I made a lot of drawings and came up with Apesanteurs. It started out as weightless, vertical and horizontal bands of colour in a transparent mass, inducing contemplation. But it took me two years to find the right way to apply them. Then, I started to turn them into waves, with more movement. Through trial and error, I came up with forms and results that really appealed to me. As soon as I was able to veer away from my father’s work, I did so. As soon as I was able to get away from the pleating and draping, I followed that path. The goal is always to find the path, the right path, the one that suits us, the one that helps us grow, move forward, break new ground and express our ideas. I’ve always leaned toward sculpture and installation, and that’s what I do today. I’ve also been keen to explore what the Americans call glass “panels”, ever since I began taking more of an interest in the work of Hans Hartung, AnaEva Bergman and Mark Rothko.

— MF: And after Apesanteurs you came up with Collines ?

— AP: Yes Collines

— MF: How did that transpire?

— AP: Well, my mother has been to the Sahara twice and I’ve never been able to go with her. When she came back, she opened her bags and showed us the little things she’d found. She shared her photographs and she told us stories. It was as if we’d travelled with her vicariously from Biot. It was amazing. Nowadays, it’s too dangerous to go. But through the way she talked and the images she conveyed, she

really made me feel the desert, the immense stretches of sand and that sense of infinity. The most striking thing was the sand. Those soft, ever-shifting shapes. At first, I really wanted to capture the sand, the dunes, the contours, the lines and the patterns. But I very quickly moved on to concave and convex shapes, from a less realistic perspective. That’s when I realized I was more interested in playing with the different volumes and the way they fit together, making them into modules and working on accumulation to develop my installations. Through the cumulative material effects and the use of colour, I was able to create a sort of perpetual motion. In the end, the different elements speak to one another, there’s a connection and interaction between the component parts that creates an overall coherency. These notions of motion, interaction, connection, combination, installation, accumulation and material effects are really the guiding principles in my work. They are like a theme that runs through it. A kind of working drawing.

— MF: And there’s also light. You play with the light. It falls on forms, volumes and volutes. It passes through or skims the surface. It creates visual effects. It brings out colours. It highlights the grain or texture. It creates a sense of contrast and clearly develops that impression of movement. The word “impressionist” springs to mind. I would even go as far as to say “percept” in this particular case. The piece is brought to life by all of these combined effects, and conveys that sense of the desert as we feel the wind, the light and that perpetual motion. Which leads me onto another question. What about the history of art? The history of form? Dating back to the cave paintings and even before, with the initial use of symbols. Is that something you delve into? Do you research it and read up on it? Do you use it as a source of inspiration?

— AP: Research and reflection are a key part of my creative process. It can take me years to come up with a project and hone my thoughts. But there’s also a sense of intuition,

which leaves room for more spontaneity, and my choice of style and form. Colonnes Roseaux took me four years. Four years to develop everything and find the right balance. I wanted it to be shown indoors and outdoors. I wanted it to be monumental, modular, drawing on accumulation. I wanted to vary the chromatic and material effects. At first, you always hit hurdles. You lose a lot of time on technique and design. You have to find the right person to work the metal. You need the right diameters, the right proportions. And all the while you’re refining your approach. Now, with time, I tend to hit fewer stumbling blocks from a technical standpoint, which leaves me more room to focus on the storytelling. Some of the great names who have left their mark on modern art have drawn inspiration from other civilizations. Take Brancusi, for example, who drew inspiration from Asian and African forms for his Endless Column, and Duchamp’s famous comments on the aesthetic purity of a propeller.

— MF: How did you approach On the Rock?

— AP: I poured the glass straight onto the rock and added a few inclusions, mainly metal. I also worked on colours and materials. To my mind, these combinations are clearly a metaphor for the transformation of the material. And there are lots of other little associations. The light blue evokes ice-cold mountain streams. The rough-cut rock reflects the power of the streams, the strength of the current, and so on.

— MF: It seems you find balance between your world, your desires, your approach, your technique and your resources. And on the subject of your world, I’d like to talk a bit about another series, which you’ve called On the Rock What does On the Rock represent, with its combination of mineral and synthetic materials? How did you come up with the idea?

— AP: It was quite simple, really. I met a geologist through my mother, who talked to me about natural glass. I already knew about obsidian, of course, but finding out there were various types in their natural state was a real eye-opener. I went to see all his conferences, I invited him to my place and I even bought a few fulgurites. We talked a lot. I came to understand how lightning creates glass. For instance, if lightning strikes and then things cool really slowly, you can get quartz crystals. But if things cool really quickly, you get glass. I gradually grew more and more interested in weaving a story around this relationship between lightning, rock and glass.

— MF: So, beyond the combination of glass and stone, which provided a platform to express an idea, you’re saying these pieces were a metaphor for motion and the transformation of the elements. And, as you say, there were lots of other little associations involved. There’s something demiurgic here. You were providing a small-scale recreation in your own way of something happening on a monumental, metamorphic scale, full of fire, action, reaction and explosion. Does On the Rock perhaps capture the memory of some form of telluric activity?

— AP: There’s a strong connection to the La Vallée des Merveilles (the Valley of Wonders in southern France), which is known for its petroglyphs. There are a lot of interpretations and I’m no specialist, but it’s a place where people conveyed their connection to the cosmos. Some see it as a sort of giant observatory. And it’s also a place marked by lightning. Yet it’s also a mystical and mythological place. Some believe it was home to the original gods: the Earth Goddess and the Bull God harnessing the power of the storm… That could be another interpretation of the engravings. You should definitely visit the Valley of Wonders museum. It’s fascinating!

— MF: So, you draw on these fundamental stories, these things that fascinate you, that astound you, just as they have always fascinated humans—lightning and fire—and you delve into

cultural heritage and local geology to inspire your work. Are we talking contextual art here?

— AP: Yes, I can feel all that flowing through me. It’s a part of me. Just like archaeology and the Mediterranean steered me towards Vestiges Contemporains. But since we’re talking about contextual art, I should also say I did a residency at the Tacoma Museum Of Glass in 2014, mainly involving the On the Rock series, and was even complimented by Walter Lieberman, one of the pioneers of the Studio Glass Movement. So yes, I also worked on the contextual aspect. Mount Saint Helens erupted in 1980. For two months, citizens were on high alert. It was terrible. It changed people’s lives. It transformed the lay of the land. The whole cone exploded. We visited the eruption area and, even though we couldn’t walk around, we were able to gather rocks to create pieces. The museum kept some. One was sold and one is on display. This relationship to the volcano, fire and lighting—those natural forces that dominate us—is really something that resonates with me.

— MF: Very poetic. And before we move onto Vestiges Contemporains , perhaps we could talk about Ivresses?

— AP: With Ivresses , I wanted to move away from the concept of a utilitarian object and divert it from its primary function. I started with the idea of transmission: when you make art, as far as I’m concerned, the goal is to transmit something or at least suggest

something. I’d go as far as to say that if you can strike the right balance between form, effects, colours, materials and so on, you can induce an altered state. Baudelaire and Nietzsche both talked about that sense of euphoria. So, I played with the concept of style, substance, signifier and signified. I wanted to create an installation that produces an optical sense of euphoria through accumulation, movement, material effects and more.

— MF: Let’s move onto Vestiges Contemporains, which is the legacy and the condensation of nearly 20 years of experience, relationships and encounters, as well as a love of the Mediterranean, travel, archaeology, geology and naturalism. Is it fair to say the memory of those traditional earthenware jars flows through your Vestiges Contemporains? Would you call it a tribute, perhaps some sort of symbolic conservation?

— AP: It began as an act of awarenessraising and turned into a project based on a symbolic piece in the shape of the Biot earthenware jar, which can now be found as far afield as the United States and the West Indies, because the containers can hold drinking water longer than barrels. That led me to focus on amphoras, which have an iconic, symbolic power. So, the amphoras are actually imbued with the memory of the Biot jars. Amphoras convey so much. In a way, they are more universal than the jars. We’ve made a wide variety of them all around the Mediterranean. And amphoras are ephemeral. In the past, once they’d been used, they were often broken up and the pieces used in walls and as backfill. You can find amphoras in the subsoil of any city. They come in all shapes and sizes: anthropomorphic, slender and potbellied. They symbolize the connection between civilizations all around the Mediterranean. They have enabled ties and encouraged trade. They take us back to antiquity—a time that saw a wealth of discovery and evolution in every aspect of writing, mathematics, science, medicine, philosophy, astronomy and navigation. They take us back to everything that has happened since the dawn of the Greek, Roman, Arab, Egyptian and other civilizations. The movement of those amphoras naturally brings to mind other cultures and different points of view, as well as conflict and mutual enrichment; we forget about the Western-centric world. What is more, the amphoras bring people together more than they divide them. That’s important to me. They reflect the broad brush strokes of

my approach: humanism, universalism, culture, adventure and travel. They carry messages. They are like bottles thrown into the sea. I would even venture to say this work also draws on the combined influences of some of my spiritual masters, such as Arman with his series on New Atlantis and his archaeology of the future, and Brancusi for his refined, minimalist forms.

— MF: They are at the “crossroads in the labyrinth”, a title I borrowed somewhat unceremoniously…

— AP: Yes, I like that expression. But to follow on from what I was saying earlier, all those projects I work on inspired by past concerns and reflections provide a kind of common theme. A journey though the Mediterranean is a chance to talk about nature and people while at the same time looking at our impact, and to think about what I produce as a person. Which also raises political questions. Because where does the Mediterranean space begin and end today? Is it open? Is it closed? Is this natural space under threat? Without referring to it directly, we’re talking about the situation of those who risk their lives by fleeing their country, those who die and those who are reluctant to welcome others. We’re talking about a place and a sea awash with conflict, domination and of course pollution. Everything is mixed together. The Mediterranean is everything all at once. Amphoras have always been and still are a poetic way to evoke travel, the sea and humanity, not to mention other existential questions.

— MF: The sea that is both limitation and liberty, a symbol of perpetual transformation. The “ever-recommencing sea”, to paraphrase the poet Paul Valéry. But we could also talk about life and death. For some people, it evokes fatality, fate, or whatever else, but the subject is open and far-reaching. What speaks to me is that each series gives you a chance to embrace an issue, explore it in your own way, expand on it, draw parallels, contemplate and share. Each piece is a crystalized facet of contemplation. And, at the end of the day, it’s perhaps less about the series than the search for something; the need to work through something. We often say art is about finding yourself…

— AP: Glass is definitely as much limitation as liberty! [Laughs.] Embarking on a project also means taking a risk, which appeals to me. As I was saying, my projects aim to evoke the human condition, our lifestyles and our impact on nature while avoiding any sort of prejudice, hasty conclusions or common views. Above all, I’m just trying to foster debate.

— MF: Foster debate… I’d like to jump in there to talk about the exhibition and what you’re showing at Villa Kérylos. You work with the place, at the place and in the place, as well as with the spirit of the place. The exhibition interweaves temporalities, as well as references to Classical culture, the Mediterranean and contemporary art, not to mention the existential, social, plastic and aesthetic aspects. It gives us a forum for questioning and debate. It’s like a tipping point, a point of convergence, or even a monumental work in situ that interacts with the spirit of the place. Could you perhaps touch on that and tell us in what way it represents your here and now? Can you tell us about its origins, its history and about what you have on display, what you’re bringing together and the themes you are exploring?

— AP: The opportunity to show in such prestigious surroundings so suited to my work is immeasurable. The villa is not a replica. It’s a recreation of a dwelling from Ancient Greece, with all the modern conveniences available in 1908. It transcends time. And in that sense it is very similar to my own approach. I immediately set out to establish a dialogue with the place, to draw inspiration from and listen to the surroundings, to create pieces as if they were part of the place, as if they had been created by the place. For example, the villa sits on a

rocky promontory and part of it is built on an old customs trail, which is now walled and has a big glass window that the sea crashes against. However, the sea rises up into this space through a special drainage system, which is fascinating to behold because it sweeps in like a guest. Villa and sea live together in perpetual motion. That’s why I set out to create an installation with waves of glass, La Mer Intérieure, featuring different forms, textures and dimensions reflecting this remarkable encounter. All the installations are based on this same approach, drawing on different archetypes. The sea here, the light and sun there. But also the vegetation, and of course the amphoras, which I feel capture the spirit of the Mediterranean. I came up with the idea of creating a series of amphoras in shades of white—opaque, translucent and transparent— onto which I could project moving images. I wanted to provoke introspection, to immerse the onlooker in the experience and take them on a journey inward. By projecting images of the shifting sea—calm, stormy, choppy and raging— along with images of the abyssal depths and the sky, I was looking to create a symbolic journey. The shadow of the amphoras is clearly present and makes a real impression. It’s anthropomorphic and reminiscent of Cycladic art. It’s the positive influence of the past. It’s our legacy.

— MF: You’re right, they do make you think of Cycladic figurines. And of the marble stargazers in Asia Minor, from the Copper Age, which I discovered recently. There’s something hieratic about them. They keep watch. And we encounter these amphoras in several places. You arrange them di ff erently in each setting. They tell many a tale. One of those amphorabased installations is called Après la Bataille Would you tell us more about it?