CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL VOLUME 48 2023 URBAN ANALYTICS

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics

The Carolina Planning Journal is the annual, student-run journal of the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

COPYRIGHT AND LICENSE

© Copyright 2023, Carolina Planning Journal. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

PRINTING

A Better Image

Durham, North Carolina

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this publication was generously provided by the Nancy Grden Graduate Student Excellence Fund, which supports graduate students working directly with the department’s Carolina Planning Journal, the John A. Parker Endowment Fund, and the North Carolina Chapter of the American Planning Association, and by our subscribers.

CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

Department of City and Regional Planning

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

CB #3140, New East Building Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3140 USA

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Lance Gloss

EDITORIAL BOARD

Abigail Cover

Kathryn Cunningham

Asher Eskind

Walker Harrison

Sarah Kear

Cameron McBroom-Fitterer

Jo Kwon

Henry Reed

Christopher Samoray

Nicholas Stover

Emma Vinella-Bruscher

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Lance Gloss

COVER PHOTOGRAPHER

Emma VInella-Bruscher

CONTRIBUTORS

Cynthia Albright

Candela Cerpa

David Dixon

Christy Fierros

Ryan Ford

Henry Maher

Isabel Maletich

Gianluca Mangiapane

Kayla Myros

Jiwon Park

Amy Patronella

Preeti Shankar

Malcolm Smith Fraser

Avinash Srivastava

Isabel Soberal

Jun Wang

www.carolinaangles.com

carolinaplanningjournal@gmail.com

SPECIAL THANKS

The Carolina Planning Journal would also like to thank the many people who have helped us all year long. These people and organizations include ________ from the North Carolina Chapter of the American Planning Association; our faculty advisor Dr. Allie Thomas; DCRP Chair Noreen McDonald; Mike Celeste and the entire team at A Better Image Printing; former Carolina Planning Journal Editor-in-Chief W. Pierce Holloway and Angles

Managing Editor Emma Vinella-Bruscher; Planners’ Forum student leaders Jen Farris, Cameron McBroomFitterer, Maggie Simon, and Laurina Bird; and, of course, all of our subscribers.

2

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Department of City + Regional Planning

VOLUME 48: URBAN ANALYTICS

CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

3

CONTENTS

FEATURE ARTICLES

10 CITY OPEN DATA PORTALS IN THE UNITED STATES

Kayla Myros

18 REDEFINING SMART: THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY AND GOVERNANCE IN INNOVATION

Malcolm Smith-Fraser

26 INTERROGATING SMART CITY PRACTICES: THE SIDEWALK LABS’ QUAYSIDE PROJECT

Jun Wang

32 STRATIFIED COLOMBIA: FORCED DISCRIMINATION OR EMPOWERED SOCIAL HIERARCHY?

Gianluca Mangiapane

38 USING DATA ANALYTICS TO SUPPORT COMMUNITY-BASED ORGANIZATIONS

Cyatharine Alias, Preeti Shankar, and Anna Wolf

48 ERRORS OF OMMISSION: UNDERCOUNTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND TRIBAL HOUSING

David Dixon and Harry Maher

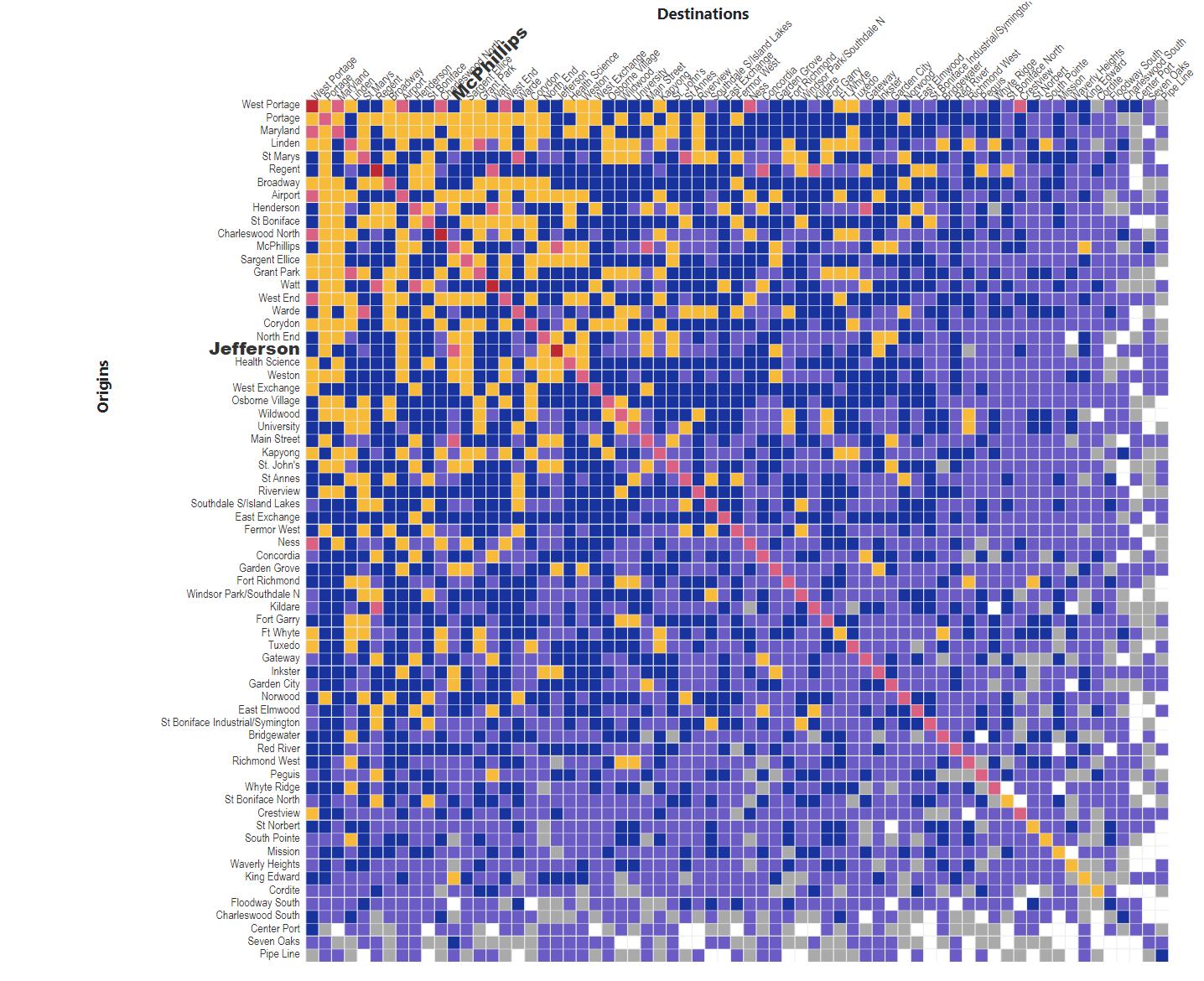

56 THE VALUE AND APPLICATION OF DIGITAL DATA FROM LOCATION-BASED SERVICE VENDORS

Cynthia Albright

64 EXPLORING OPTIMUM HOMELESS SHELTER SERVICE DELIVERY

Jiwon Park

DATA VISUALIZATION FEATURES

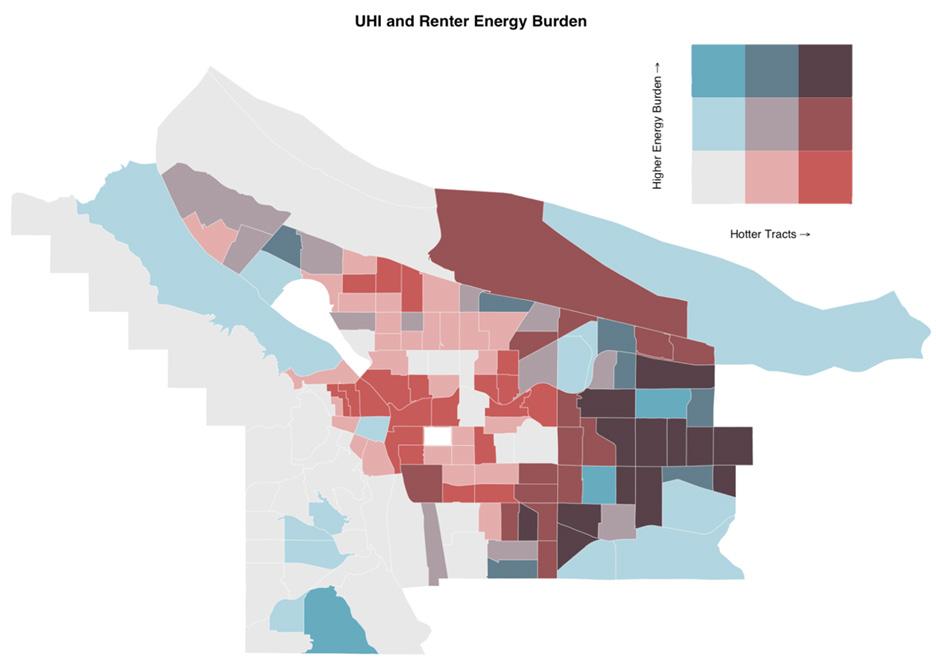

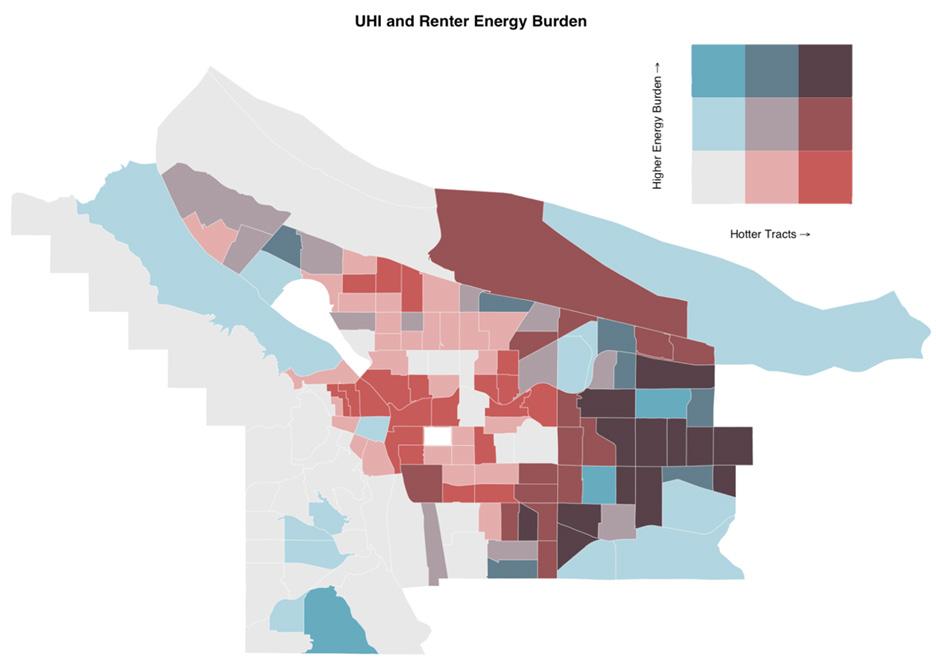

76 IMPACTS OF URBAN HEAT ISLAND ON RENTERS IN PORTLAND, OR Melissa Ashbaugh

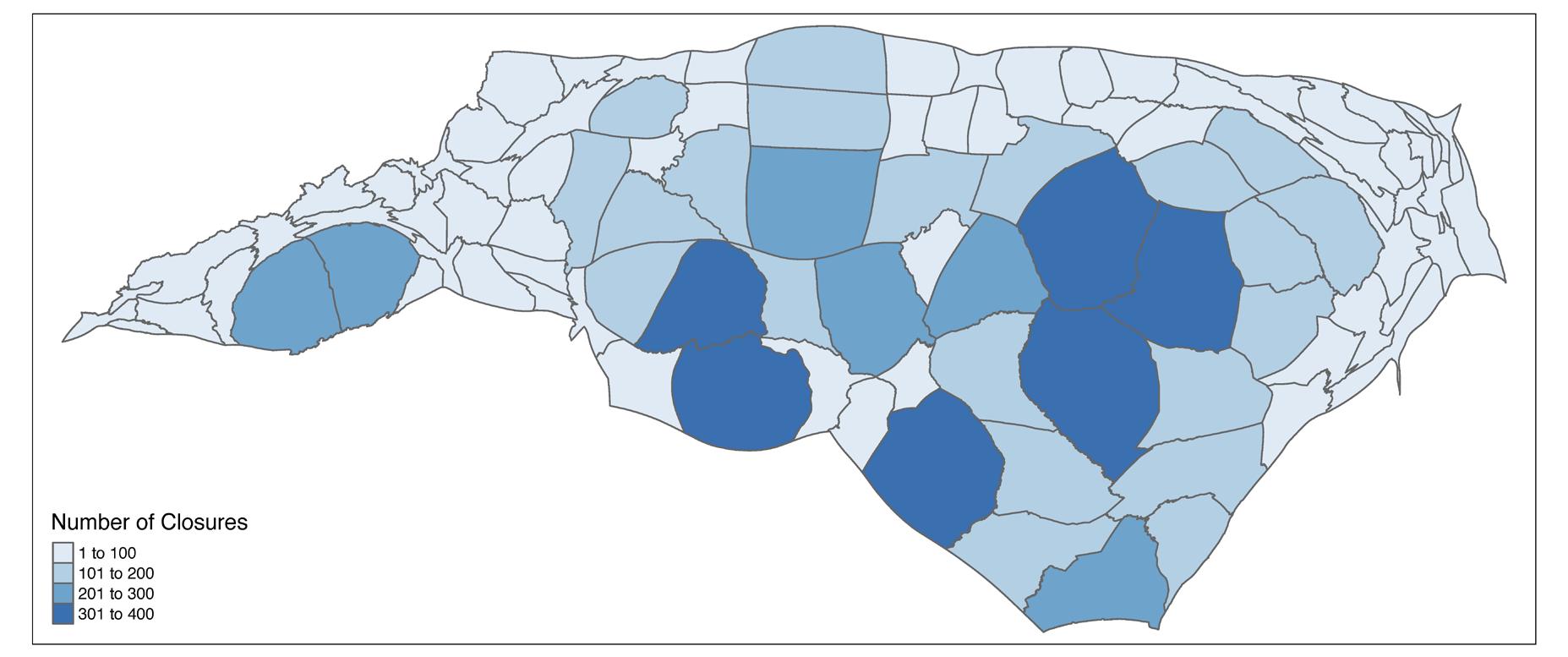

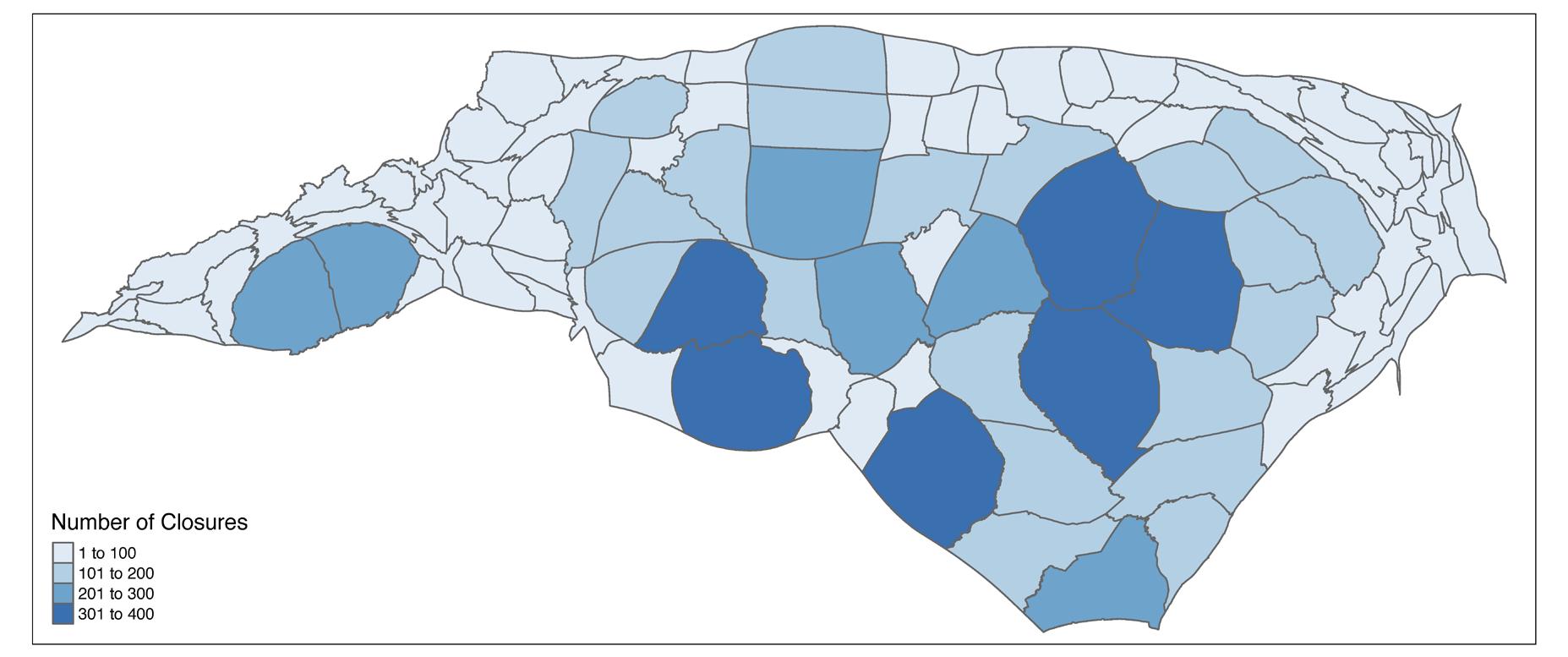

78 VISUALIZING WEATHER-RELATED ROAD CLOSURES IN NORTH CAROLINA

Julia Cardwell

80 NAVIGATING THE PULSE OF SHANGHAI’S DAILY TRANSIT

Xijing Li

06 FROM THE EDITOR 08 EDITORIAL BOARD

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 4

BOOK REVIEWS

82 SOUL CITY: RACE, EQUALITY, AND THE LOST DREAM OF AN AMERICAN UTOPIA

Book Review by Candela Cerpa

84 THE MINISTRY FOR THE FUTURE

Book Review by Isabel Soberal

86 UNDOING OPTIMIZATION: CIVIC ACTION IN SMART CITIES

Book Review by Ryan Ford and Isabel Maletich

88 ARBITRARY LINES: HOW ZONING BROKE THE AMERICAN CITY AND HOW TO FIX IT

Book Review by Amy Patronella

90 BICYCLE / RACE: TRANSPORTATION, CULTURE, & RESISTANCE

Book Review by Lauren Caffe and Kathryn Cunningham

STUDENT WORK

92 BEST MASTER’S PROJECTS

84 MASTER’S PROJECT TITLES Class of 2023

98 YEAR-IN-REVIEW: AN UPDATE FROM NEW EAST

100 NC-APA CONFERENCE ANNOUNCEMENT

VOLUME 49 CALL FOR PAPERS

5

FROM THE EDITOR

LANCE GLOSS is the Editor-in-Chief of the Carolina Planning Journal and a second-year Master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. His work spans natural resources, planning, and economic development. He received a B.A. in Urban Studies from Brown University, where he was Managing Editor of the Urban Journal

DEAR READERS,

Times change, these days faster than usual. We live in a world we would not have recognized a decade ago. New technologies infuse every facet of life. Social media, Zoom meetings, artificial intelligence, and cryptocurrencies shake the earth. We all have a high-powered computer in our pocket… unless it happens to be in our hand.

Volume 48 of the Carolina Planning Journal, titled Urban Analytics, takes a close look at how the digital era is transforming the planning profession. Cities, organizers, and businesses across the across the country have more information than ever. They also have new means of analyzing that datathat may offer solutions to age-old problems .

To help our readership come to grips with this change, we assembled work that examines both the best applications of new analytical tools and the ethical conundrums that these tools present.

Some of our authors assess iconic examples of big data in urban planning.

Kayla Myros performs an innovative assessment of Open Data Portals. Municipalities use these platforms to make datasets about urban issues publicly available. She measures the goals of these Open Data Portals against their functionality, showing us which cities get it right.

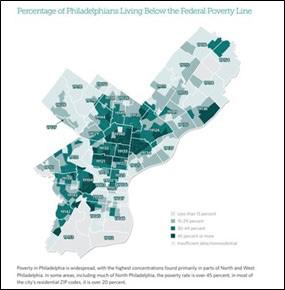

Zooming out, Malcom Smith-Fraser offers a data scientist’s view on the relationship between innovation, technology, and governance. Crossing borders, Gianluca

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 6

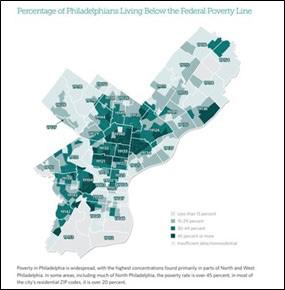

Mangiapane shows how a spatialized approach to public goods provision might be transplanted and adapted from Colombia to Philadelphia, PA.

Jun Wang walks us through the high-profile Quayside smart cities project in Toronto. We learn how Sidewalk Labs—a subsidiary of Alphabet—saw their vision of a data-driven urban future collapse under community pressure.

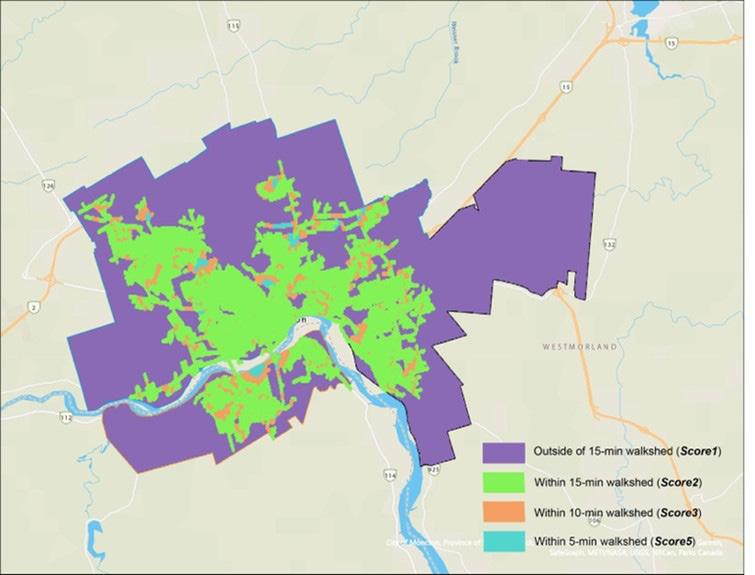

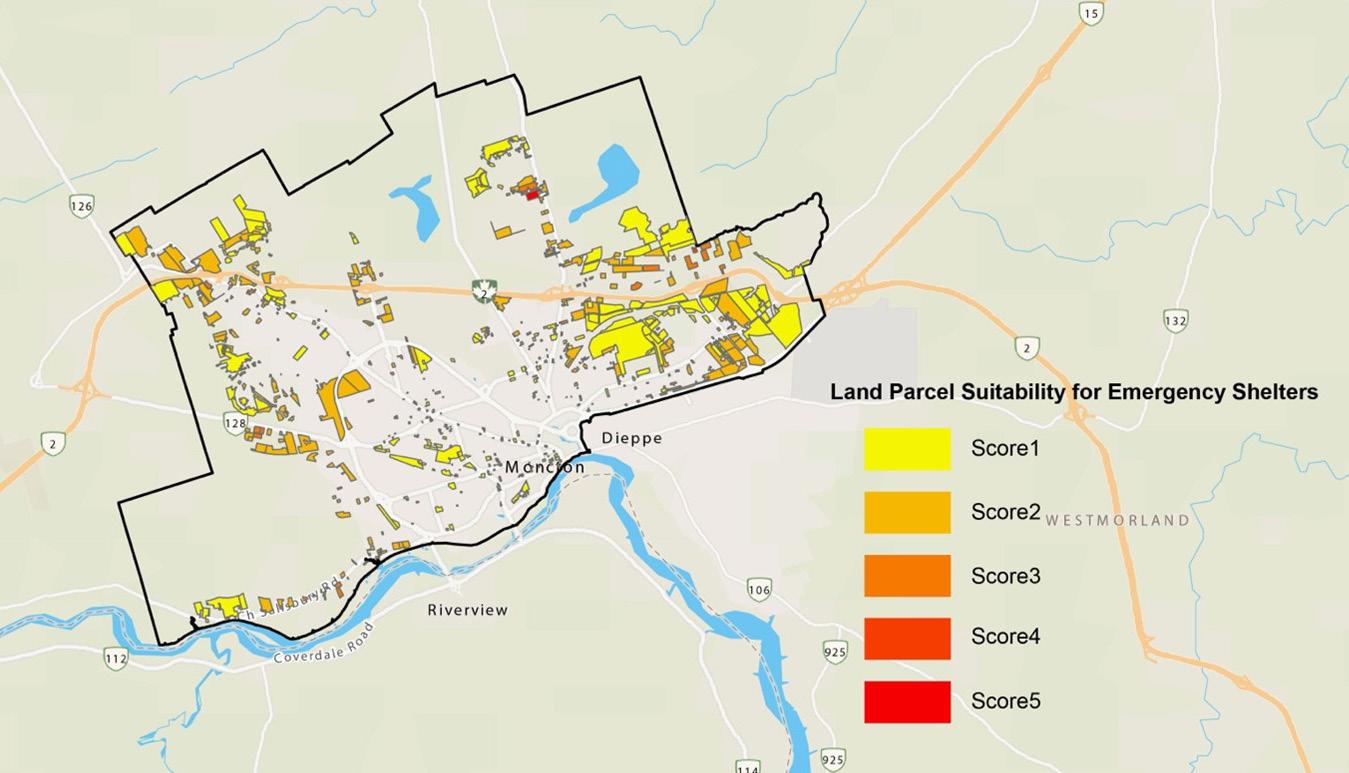

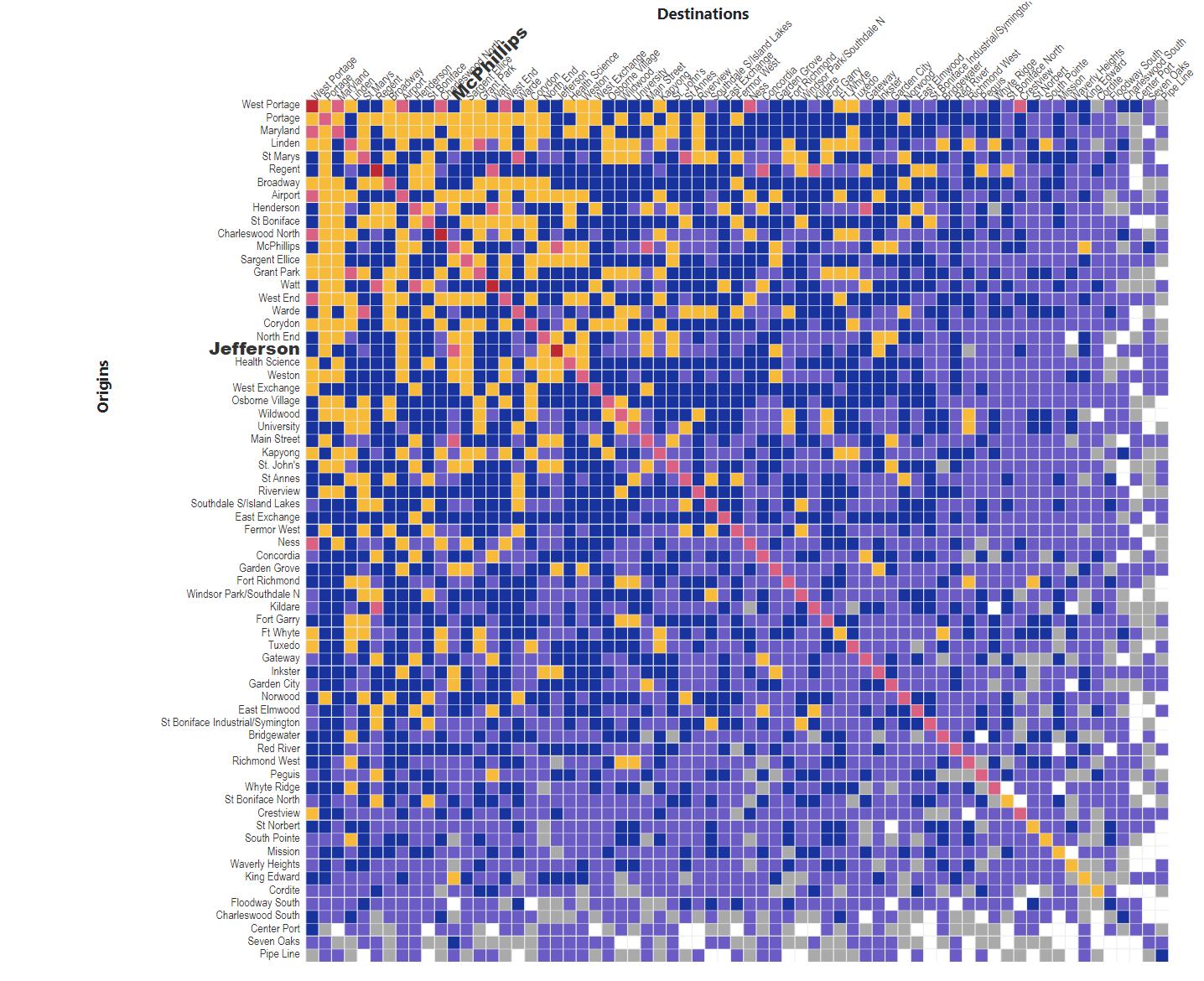

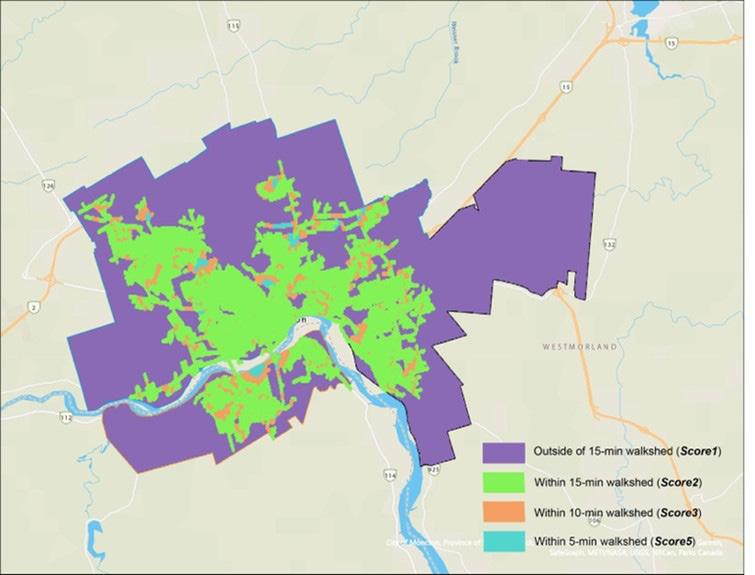

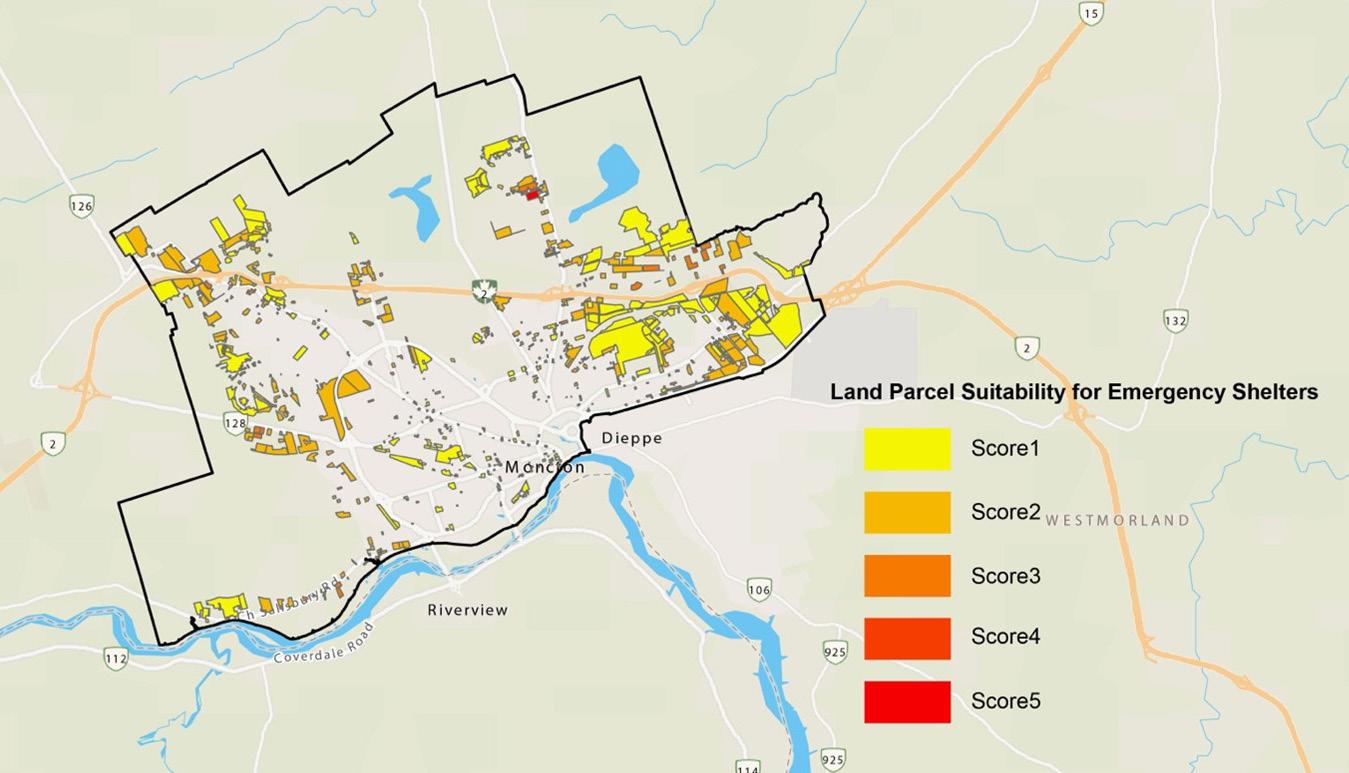

For a look at how cities and non-profits can leverage technology for the public good, we have articles from the Center for Neighborhood Technology and Jiwon Park. Preeti Shankar and Anna Wolf share what the Center has learned about integrating big data with community knowledge, wherein members of the public participateas co-experts. Jiwon Park offers an excellent example of how GIS technology can make the most of investments in services to the homeless.

For planners working with third-party vendors to use location-based service data, Cynthia Albright provides a detailed guide that clarifies this booming and complex field. Rounding out the volume’s feature articles, David Dixon and Harry Maher dive into the 2020 US Census, showing how the resultant dataset managed to miss fully 5.6% of indigenous Americans living on tribal land.

In a new section this year, we also showcase four innovative applications of data visualization in planning. As always, we bring you a set of book reviews addressing the best work in the field from recent years—including some fiction. Online, you can dive deeper with our Angles blog, managed by the incredible Jo Kwon (a PhD candidate at DCRP).

This year’s cover photo comes from Emma Vinella-Bruscher (a DCRP Masters student and former Managing Editor of Angles). It prompts the same questions that anyone engaged in the digital transformation of urban planning will have asked. As our infrastructure becomes more complex and increasingly abstract, what will be the role of human residents? Will there be room for agency? Or will residents be reduced to shadows, imprinted in abstract form on the digital architecture of the future?

I hope that readers find this volume stimulating and challenging. We are in uncharted territory. While the CPJ cannot hope to provide a map, we have tried to assemble a compass.

Thank you very much for reading.

Lance Gloss

7

EDITORIAL BOARD

The following people are integral to the success of the Journal and its online platform, CarolinaAngles.com:

JO KWON / Managing Editor of Carolina Angles

Jo (Joungwon) Kwon is a fourth-year Ph.D. student in the Department of City and Regional Planning. She is interested in using visuals in plans, specifically in environmental planning. She has been a part of CPJ since 2019. With a background in Statistics and English Literature, she received her M.A. in Computational Media at Duke University. In her free time, she enjoys indie films, live performances, climbing, and drinking coffee.

IAN BALTUTIS / Online Contributor

Ian Baltutis is an inventor, serial entrepreneur, planner, and Master’s student at UNC DCRP. After founding Burlington Beer Works, the first co-operatively owned brewery and restaurant in NC he made the jump into public service when he was elected Mayor of the City of Burlington, NC in 2015. He served 3 terms leading the launch and expansion of the city’s Link Transit bus system, construction of a greenway network, and modernization of planning, zoning, and development ordinances. He is passionate about place-making, walkable communities, and trains. He loves riding trains and visiting railroad museums all around the world.

CANDELA CERPA / Online Content Editor and Incoming EIC

Candela Cerpa is a first-year master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UNC-Chapel Hill. She is interested in equitable disaster planning, particularly around floods. Born and raised in Uruguay, she received her bachelor of science in Environmental Science and Policy from the University of Maryland, College Park. Outside of work and school, she enjoys cooking and eating good food, listening to audiobooks, and organizing around climate and social issues.

ABBY COVER / Content Editor

Abby is in her first year of the City and Regional Planning Master’s Program, and is looking forward to sharing all she has learned with her future employers. She previously studied Sociology and Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. Before coming to UNC, Abby could be found galivanting through her native Philadelphia (Go Birds!). Her planning interests include climate adaptations, sustainable development, and fostering community engagement. Outside of planning you can find her grabbing a bagel sandwich, watching horror movies, and wishing for better public transit.

KATHRYN CUNNINGHAM / Content Editor and Incoming ME of Carolina Angles

Kathryn Cunningham is a first year Master’s student with the Department of City and Regional Planning whose interests include climate change adaptation, parks, and public space. She studied Environmental Studies at Williams College, and before coming to graduate school, she was in the San Francisco Bay Area managing sustainability projects for a law school. When not in class, she enjoys reading, running, and exploring the Triangle.

ASHER ESKIND / Content Editor

Asher is a first-year DCRP master’s student specializing in transportation planning. He grew up in Charlotte and earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Colorado Boulder in 2021. His interests within planning include active transportation, rural planning, public land management, and the effects of physical geography on urban spatial organization. You might see him out of breath after biking up Raleigh Road or in the computer lab late at night perfecting a map in ArcGIS Pro. Outside school, Asher is an avid skier and a big road-tripper, having traveled to over forty states and over twenty national parks.

RYAN FORD / Online Content Editor

Ryan Ford is a Master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UNC Chapel Hill. He is interested in the intersection of urban design and transportation specifically around active mobility. Outside of classes, you can find Ryan playing tennis or catching a movie at Varsity Theater.

WALKER HARRISON / Content Editor

Walker is a second-year master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning. He is interested in sustainable mobility, pedestrian safety, and climate resiliency. Walker worked as a planner for Spindale, North Carolina before joining DCRP and currently works for Chapel Hill Planning Department. He enjoys playing mandolin and planning his next bike adventure.

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 8

SARAH KEAR / Content Editor

Sarah is a dual master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and in the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University. Sarah has interests in sustainable and equitable transportation and its intersection with energy. She received her undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in political science, gender and women’s studies, and Chicanx and Latinx studies. In her free time, Sarah enjoys trying out different recipes and collecting pottery.

CAMERON MCBROOM-FITTERER / Content Editor

Cameron McBroom-Fitterer is a second year Master’s student in City and Regional planning whose interests include climate change adaptation, coastal hazards, and mass transit. Before moving to Carolina, he was raised in Miami, FL, where he earned an undergraduate degree in History from the University of Miami in Coral Gables. In his free time, Cameron enjoys playing music, watching good films, and supporting his hometown sports teams.

AMY PATRONELLA / Online Content Editor

Amy Patronella is a second year Master’s student in City and Regional Planning. Her upbringing in Houston, TX informs her interest in the nexus of mobility, green space, and climate resilience. She received an undergraduate degree in Political Communication with minors in Public Policy and Sustainability from George Washington University. In her free time, she enjoys reading, biking, and talking Texas politics with anyone who will listen.

HENRY READ / Online Content Editor

Henry Read is a Master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning, with a focus on land use policy. He is fascinated with the minutia of development regulation and doesn’t understand why so many people think zoning is boring. He hopes to work in the public sector after graduation and would like to be remembered as the guy who got your town to stop requiring bars to have customer parking and start planting native fruit trees in parks.

NIK REASOR / Online Content Editor

Nik Reasor is a first-year Master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at Chapel Hill where he specializes in Land Use and Environmental Policy. In particular, Nik is interested in climate change adaptation and how to best help disadvantaged communities survive the challenges the future presents. Previously, Nik earned his BA in Sociocultural Anthropology, Medieval studies, and Urban Planning at UNC. You can usually catch him around Chapel Hill biking to local cafes to catch up on work or at the gym coaching UNC’s boxing team.

CHRISTOPHER

SAMORAY / Content Editor

Chris is a doctoral student in the Department of City and Regional Planning specializing in land use and environmental planning. His research interests relate to issues at the coast, including sea level rise, flooding, and storm surge. Chris has a background in marine biology and science communication, having published in several science outlets. Chris earned his Master’s in landscape architecture at the University of Maryland.

NICHOLAS

STOVER / Online Content Contributor

Nicholas Stover is a first-year master’s student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in the Department of City and Regional Planning. At UNC, he concentrates on land use and environmental planning with interest in the intersection of design and policy. In this area, he is most interested in the effect of policy outcomes on resilience in the built environment, and sustainable development. In his free time, he enjoys woodworking, movie going, and drinking good coffee.

EMMA VINELLA BRUSCHER / Content Editor

Emma Vinella-Brusher is a third-year dual degree Master’s student in City and Regional Planning and Public Health interested in equity, mobility, and food security. Born and raised in Oakland, CA, she received her undergraduate degree in Environmental Studies from Carleton College before spending four years at the U.S. Department of Transportation in Cambridge, MA. In her free time, Emma enjoys running, bike rides, live music, and laughing at her own jokes.

9

CITY OPEN DATA PORTALS IN THE UNITED STATES

KAYLA MYROS

Kayla Myros is currently a master’s student at Harvard University Graduate School of Design, where she is studying urban analytics and planning theory. Her work at the Boston Planning and Development Agency informs her studies on how data and technology are used in planning processes. An advocate of qualitative and quantitative analyses, Kayla explores how technology can create new avenues for participation and co-creation of data between planners and communities.

ABSTRACT

Digital technologies have transformed governance. Open data initiatives are one such major innovation. Also called open government data portals, these platforms publish free, publicly available datasets relevant to the local government, changing the way the residents obtain information from their government. Such initiatives are characterized as fostering government transparency and public participation, and these values are reflected in the missions of government initiatives. But do open data portals embody their mission statements? This study examines the extent to which U.S. municipalities incorporate features into their open data portals that support the stated goals of the initiative. Results show that most cities do not include features to support public participation on their open data portals, with the exceptions of Austin, TX, New Orleans, LA, and Philadelphia, PA. This study calls on planners to become more involved in local open data initiatives. The planning profession has data-analysis and public engagement skills that are critical to the success of open government data.

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 10

OPEN DATA PORTALS

Digital technologies have altered governance and changed what the public can expect—and demand—from their government. Open data initiatives are an example of new forms of government-to-public communication channels. Open data refers to collections of data both publicly-available and government-owned. These datasets are accessible for use and distribution within the public domain (Boston, n.d).

The movement for opening government data has its origins in Web 2.0—also known as the internet-era—in the mid1990s (Chignard, 2013). The internet ethos of this era was for open source, open access, and unrestricted knowledge sharing (Chignard, 2013).

Moving into the new millennium, interest grew to “open up” government data. The broadly stated purpose of open data is to foster government transparency and civic engagement, with the loftier aim of encouraging innovation

and economic development (Janssen 2011, Schalkwyk et al. 2017, Zhu and Freeman 2019, U.S. Data).

In 2009, the Obama administration signed an executive order for an Open Data Policy (ODP), which required that federal government agencies make their data open, readable, and accessible to the public. The policy led to federal agencies publishing internal datasets on publicfacing repositories known as open data portals. The datasets to which the Open Data Policy gave rise became broadly popular and saw quick adoption at the local level.

This growth of open data initiatives prompts us to examine their effectiveness. Immediately, we can see that open data portals have superficially similar designs and functions. This may correspond to the pressures of the open data software market, and aligns with evaluations made by consultants and NGOs.

But are all open data portals in U.S. municipalities the same? Or do cities tailor their open data portals to

FEATURE ARTICLES

FIGURE 1- A map of 34 US cities with open data portals.

11

Credit: Kayla Myros

reflect differing missions and goals? To what extent do US municipalities design their open data portals to support their stated goals?

(HOW) DO OPEN DATA PORTALS WORK?

Open government data is a 21st century phenomenon addressed by a growing body of academic research. In the recent years, evaluations of open data portals addressed in terms of their implementation, quality, and use. Benchmarking open data at the national level is broad, scoring portals primarily on ease of use and quality of data (Lourenco 2015; Máchová and Lnénicka 2017).

Such benchmarking processes have been adopted at the municipal level in the United States. The foundational study for benchmarking U.S. municipal data portals was Thorsby et. al (2016), which focused on surveying features and content. While Zhu and Freeman (2018) adopted similar metrics, their analysis was weighted to understanding the user interaction interface of open data portals.

Beyond comparisons across different open data portals,

researchers have also evaluated use and outcomes. Wilson and Cong (2021) conducted semi-structured interviews to understand who uses open data; they found that successful open data portals prioritize usability, such as by incorporating easy-to-use features that fosters user interaction and engagement. Lock et al. (2020) researched use-cases for participatory features on open data portals and urban dashboards, such as participatory mapping, realtime surveying, and participatory budgeting to create, in many instances, real-time data.

Leveraging city digital technologies can improve communications between bureaucrats and the public, and it creates a system wherein the public can have more influence over service delivery and in the planning process. Hivon and Titah (2017) and found that public participation is central to the success of open data initiatives. These studies indicate the academic interest in the performance of open data initiatives.

By contrast, only limited research investigates the match between goals and outcomes of municipal open data initiatives. The purpose of this study is to assess

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 12

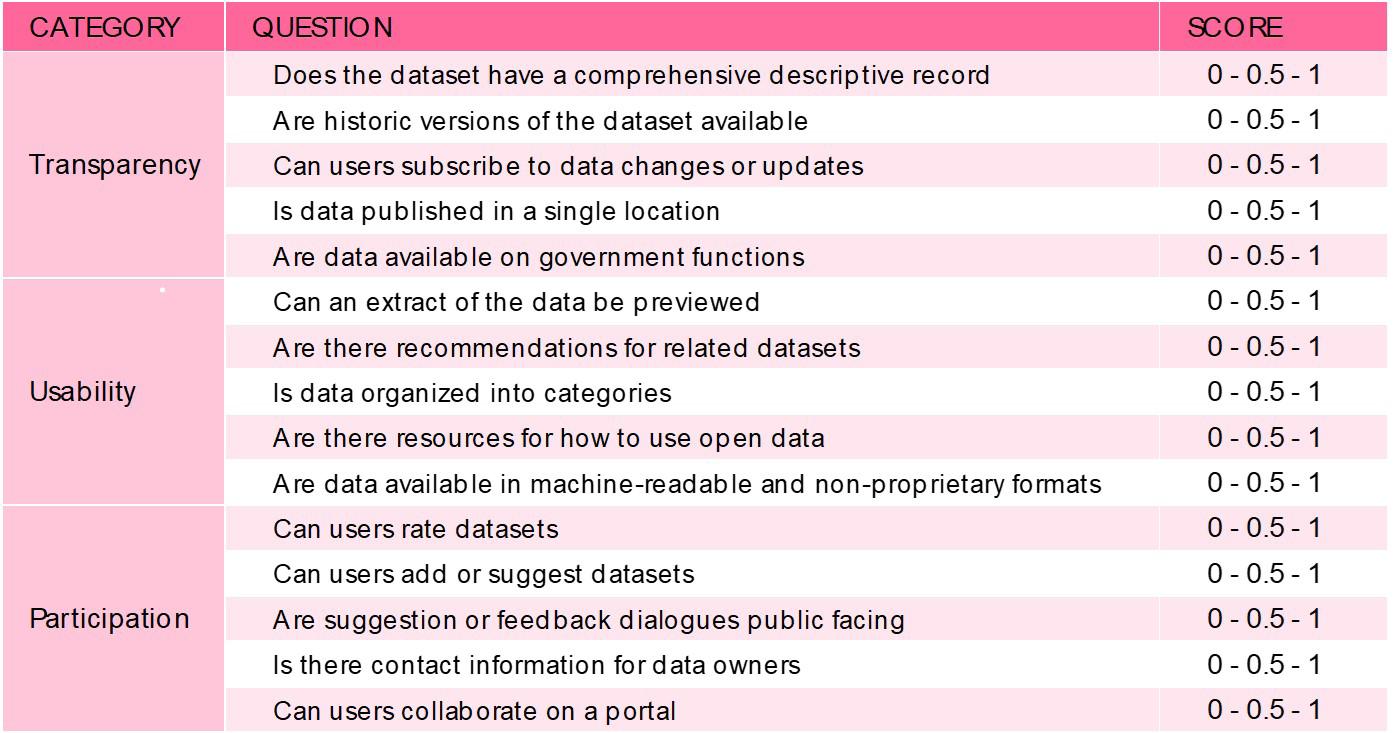

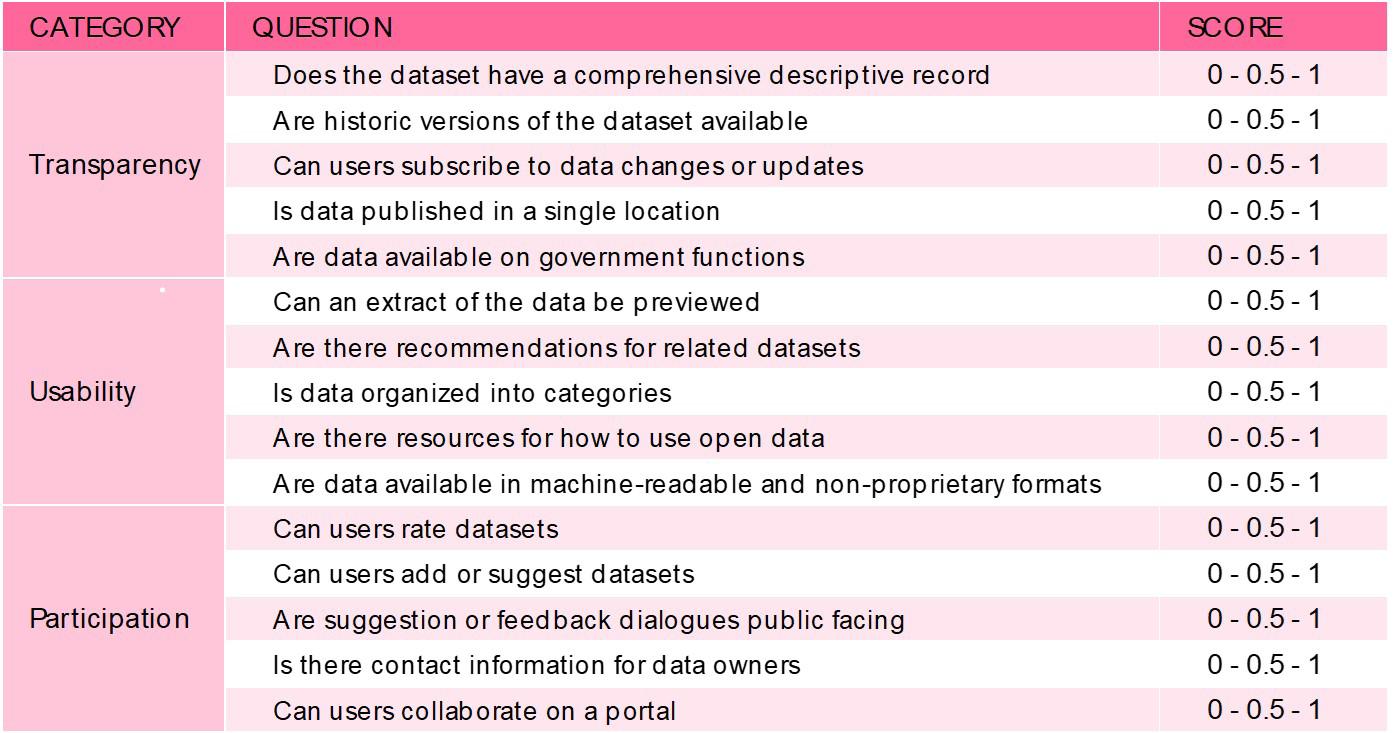

FIGURE 2- The portal evaluation scorecard.

the priorities of municipal data portals for three values: transparency, usability, and participation, and evaluate whether the features on municipal data portals align with the stated goals.

MEASURING FEATURES AND MISSIONS

To measure how well municipal data portals match their stated objectives, this study analyzes features and mission statements for U.S. municipalities. A common study sample for research on U.S. municipal open data is the national register of open data portals from data.gov (Nahon 2015; Thorsby et al, 2017; Zhu and Freeman, 2020). The sample involves 34 cities and towns across the United States, as shown in Figure 1.

Key actors of the open data movement such as the Sunlight Foundation, Open Knowledge Foundation, Code for America, and the U.S. Open Data Initiative identify core values for open data portals. These values are to foster government transparency, end-user accessibility, and public participation. This study aims to qualitatively analyze U.S. municipal open data portals based on if the features and functionality upheld these core values.

It draws from benchmarking and evaluation studies completed by European Commission (2020), Zhu and Freeman (2019), and Máchová and Lnénicka (2017).

The original scorecard below allowed this assessment of features on municipalities’ portals. The sample set of U.S. municipalities’ open data portals are scored for the clear presence (1 point), infrequent presence (0.5), or absence (0) of the features listed in Table 1. A municipality could score a maximum of 15 points if all features were consistently present.

To measure a municipality’s values, mission statements sourced from each portal were rated by three reviewers for the presence of participation, usability, and transparency values. To determine how mission statements aligned with the criteria, raters again used a three-point scale: clear presence (1 point), vague reference (0.5) or clear absence (0).

A given city can receive a top score of three points per value per review, and nine points combined points across all reviewers. Municipalities with no description received a score of zero for the mission statement coding. The mission statements provided to the reviewers were

FEATURE ARTICLES

13

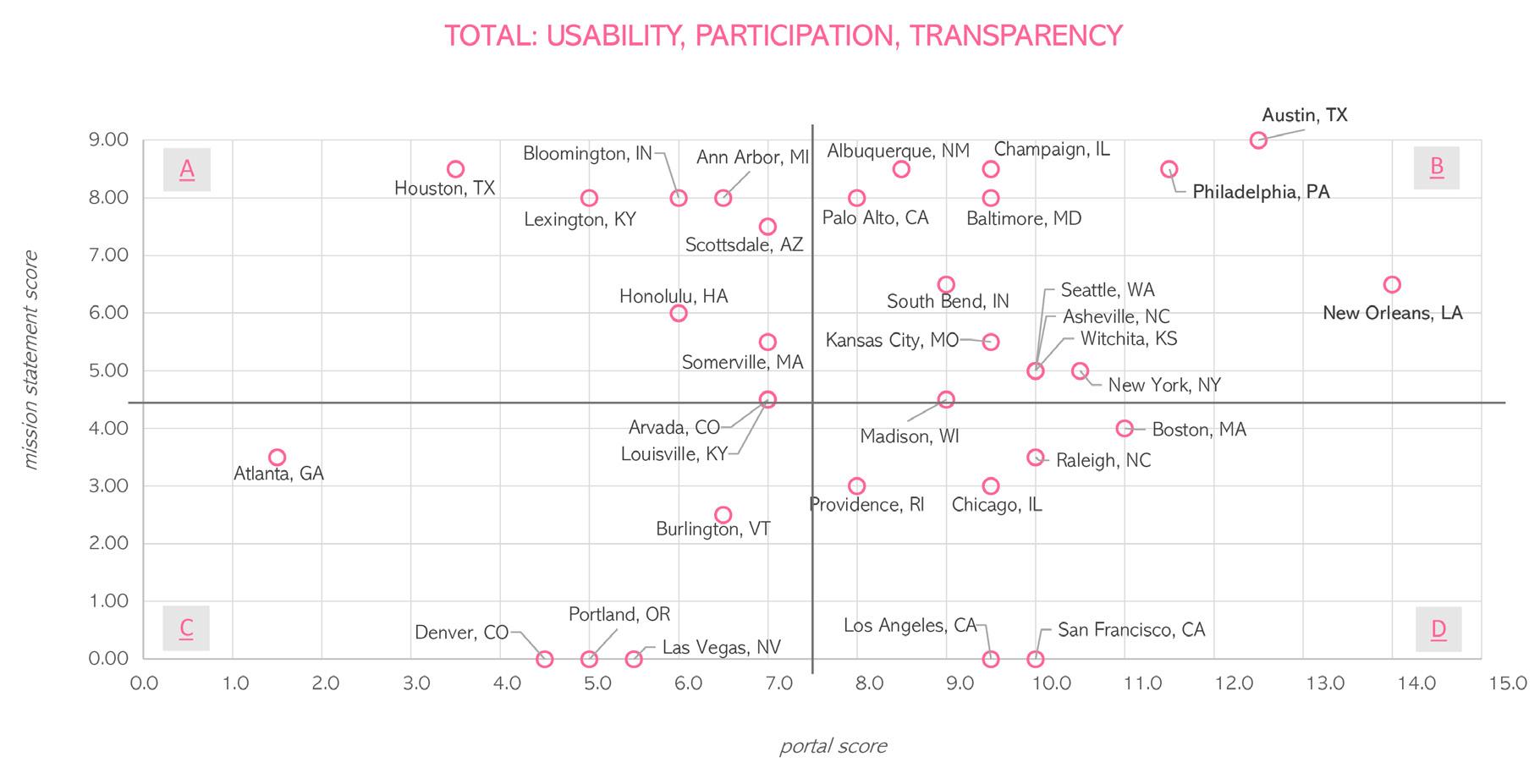

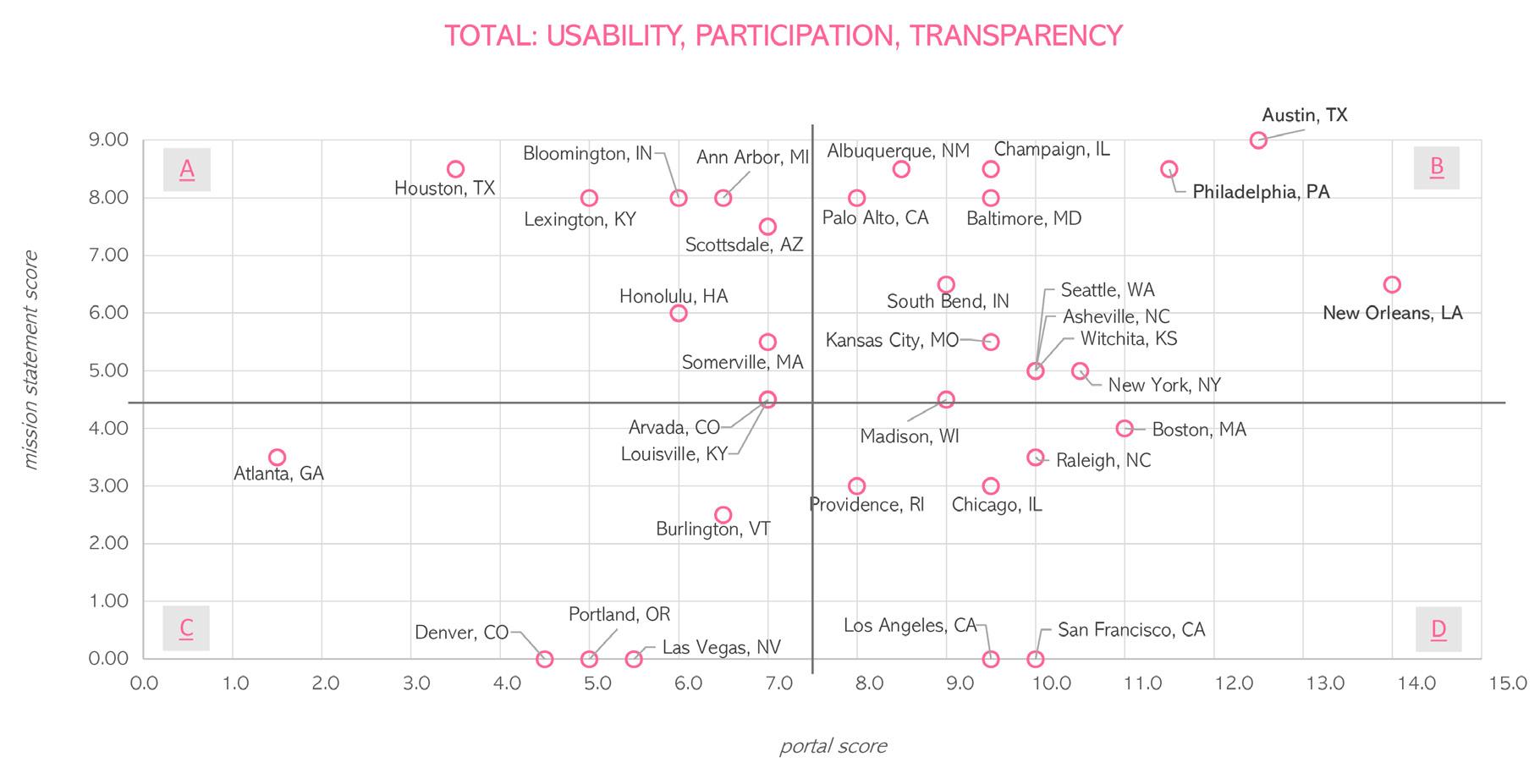

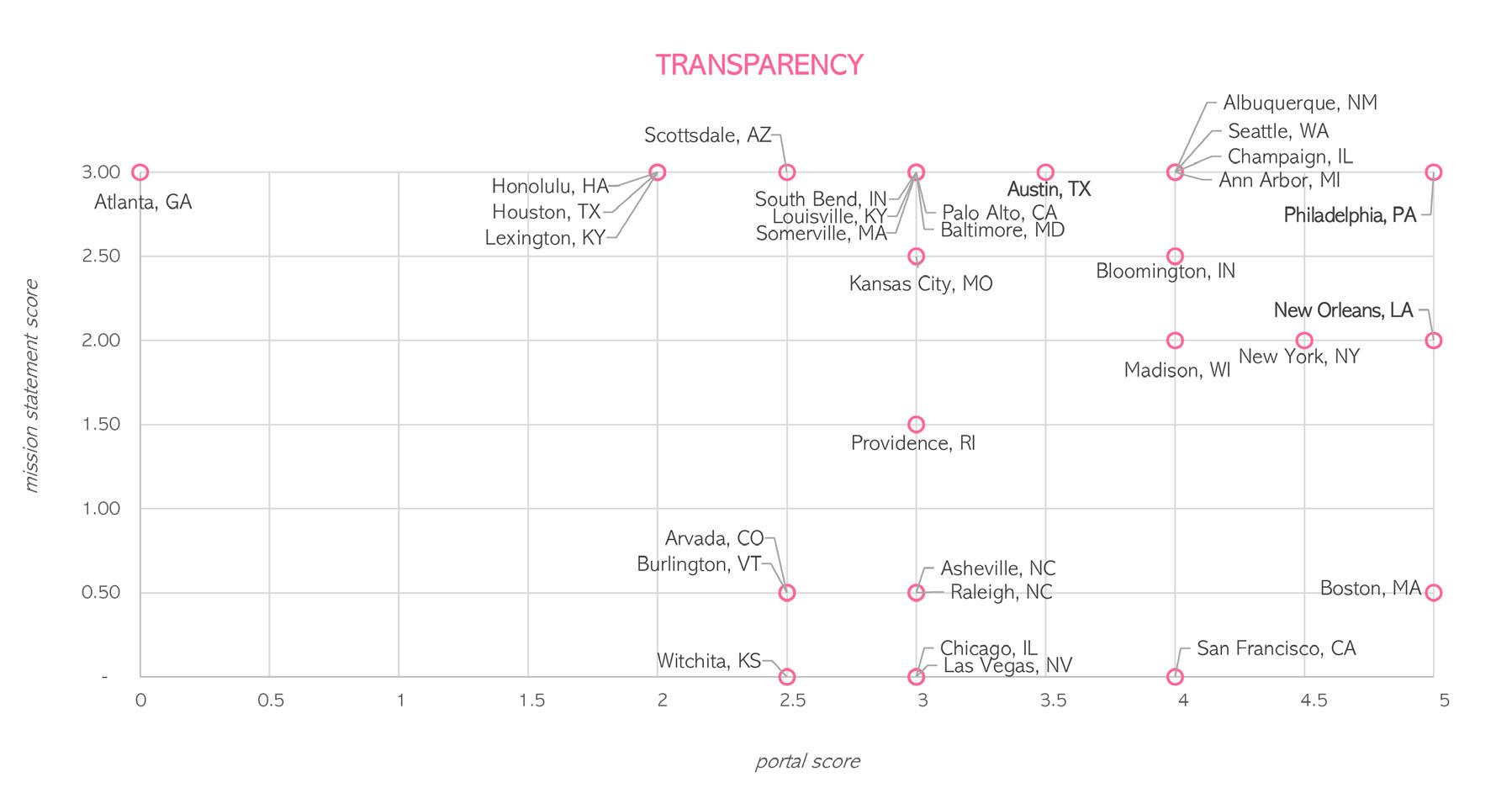

FIGURE 2- Combined value outputs for open data portals against their mission statement scores.

anonymized to limit affinity bias or preconceptions associated with different municipalities.

Thirteen cities had a high match between mission statement values and portal features, as shown in Figure 2. Quadrant B shows a high indication on mission statement and a high indication of portal features, referred to as match. Quadrant C is the inverse of this relationship.

Quadrant A has a high indication on the mission statement but a low portal score. This is a mismatch. The other mismatch shown in quadrant D shows the inverse relationship, with high scores for portal features and low indication on the mission statement.

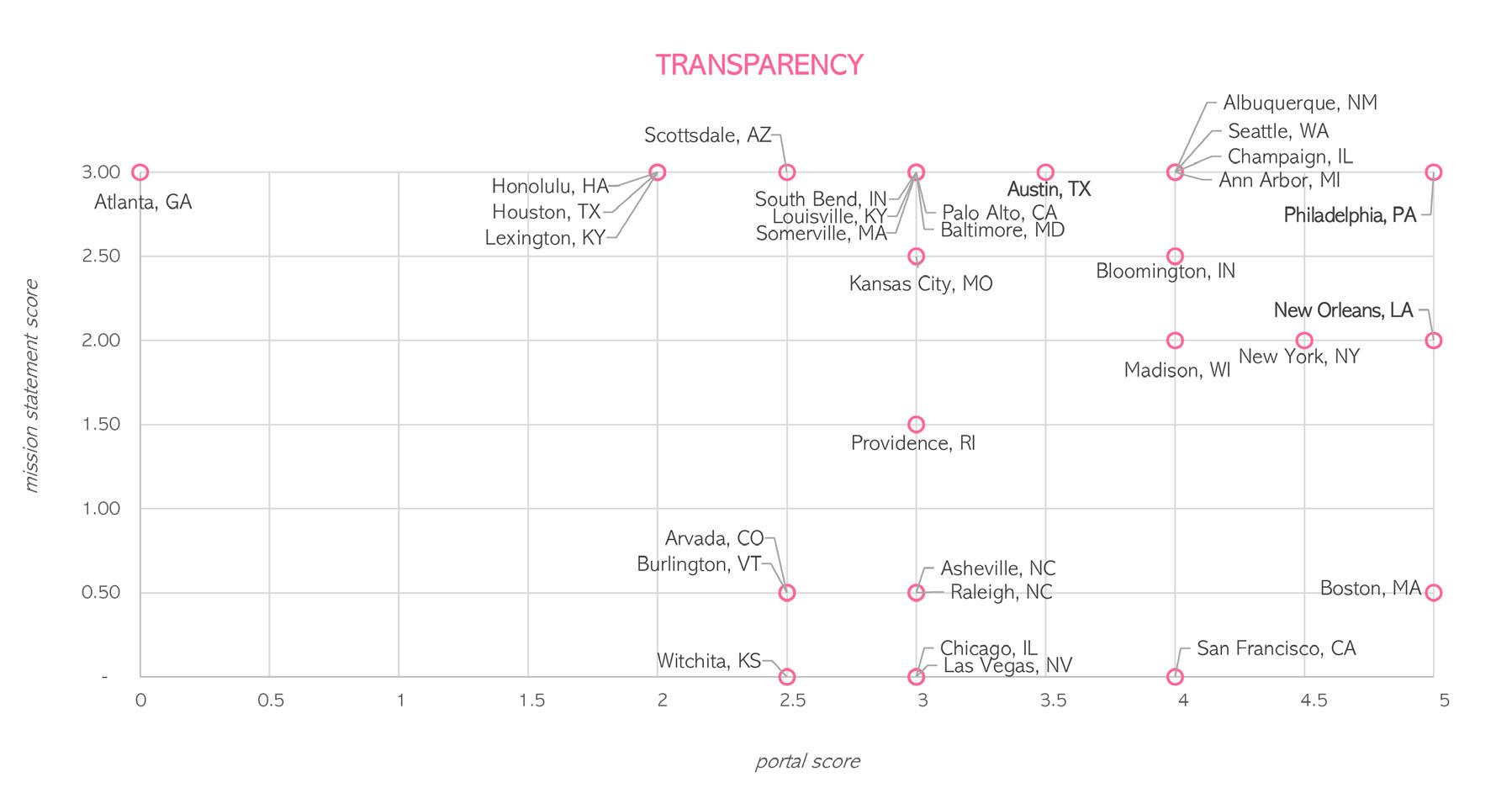

Most cities surveyed identify transparency as a goal for the open data initiatives. Since government transparency is the

FIGURE 4 - Transparency value outputs for open data portals against their mission statement scores.

FIGURE 4 - Transparency value outputs for open data portals against their mission statement scores.

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 14

FIGURE 5- Usability value outputs for open data portals against their mission statement scores.

foundational goal for open data initiatives, it is a promising result to see the majority of cities incorporating features that foster greater government transparency. These features include having datasets regarding government operations, budgeting, and decisions. They also offer clear and forthright details about the data origins, owners, and history.

Baltimore, MD and Austin, TX received “perfect” scores in terms of matching usability features on the cities’ open data portals and identifying usability as a goal for their portals. Usability is an inherently necessary feature of open data portals. However, for some cities their portals may function more like a repository of data than an interactive website. The more use-functions that are built into the portal, the wider the audience that is likely to access and use the portal. Correspondingly, a majority of these cites prioritize usability in their portal features as an overall goal of their open data initiative.

Most cities identify public participation or civic engagement as a goal of their open data portals, however few have features to support engagement directly on the

portal. Uniquely, three cities, Austin, TX, New Orleans, LA, and Philadelphia, PA, prioritize engagement as a goal and incorporate participatory and engagement features on the portal. Such features include the ability to suggest a dataset, publicly communicate with data owners, and a public forum or discussion board. A limitation is that this study does not measure how well engagement is achieved, but simply whether it exists as a function on the data portal.

LESSONS FROM EFFECTIVE PORTALS

We see that, while it is a commonly cited goal, participation rarely corresponds to user-friendly features on portals. Open data portals, apparently by default, are designed for a one-way flow of information, despite participation being an explicitly stated goal or outcome of open data initiatives. Very few municipalities or states prioritize a two-way flow of information between the public and the government with open data (Ricker et al, 2020; Lock et al, 2015).

However, the results of this study also emphasize that

FEATURE ARTICLES FIGURE 5 - Participation value outputs for open data portals against their mission statement scores. 15

some open data initiatives succeed in actively fostering usability, transparency, and participation. The three edge cases noted above help us to understand the portals of cities that aspire to accessibility in their missions and deliver in their portal designs. Austin, New Orleans, and Philadelphia are the matches with highest scores on both mission and portal features, but their participatory features look different and are tailored to suit the needs of its constituents.

New Orleans’ portal focuses on engaging residents to improve service delivery. The city’s mission statement includes actionoriented descriptions, such as building an app or developing a website to foster engagement and solve local problems. New Orleans has many interactive dashboard features that demonstrate how one could start these endeavors.

Austin has a growing tech industry, and its mission statement identifies “establishing a system of public participation, collaboration, and accountability.” This is exemplified on the portal’s “Suggest a Dataset” discussion board, where viewers can see suggested datasets and whether they were accepted by the review board. Additionally, Austin has a separate community board where users can discuss data, share information, and post meeting-group details. This site enables users to collaborate and participate in analyses and other programs that use government data.

Philadelphia also features a public-facing discussion board, and it is moderated by both the city and volunteers. Philadelphia’s tech sector is active in shaping the product as the portal was created with a partnership from a local technology non- profit. A further analysis that could be completed is determining the presence of a tech-sector and if it has any influence on the portal design and offerings.

These high-match edge gases reflect aspects of various open data initiatives across the world. In the UK, residents of a Brighton neighborhood were equipped with energy meters to monitor their household’s electricity usage. The individual household data was made public, a local artist painted the streets of the neighborhoods according to the block’s energy consumption. Seeing the results of their energy consumption right outside of their homes, participants were motivated to reduce their usage (Lock et. al, 2020).

In Cape Town, South Africa, activists fostered partnerships between the data-savvy and the general public to understand the current state of service delivery and propose new systems to their local government (Ricker et. al, 2020). Findings from Hivon and Titah (2017) support these engagement projects, suggesting that more hands-on public participation with governmental data is essential for the success of open government initiatives.

PLANNERS’ ROLES IN PARTICIPATORY DATA

This supports a case for planners to further involve themselves in open data to improve public engagement. Planning professionals possess a unique skillset that is valuable to the effectiveness and success of open data initiatives. Whether or not a planner is employed in their local municipality, there are many ways that one can become involved to elevate the usefulness and power of open data within their communities. For example, planners have data-analysis skills and can work to develop tools and resources that makes using data more approachable and accessible.

When open data initiatives began in the late 2000s, there was not much guidance beyond ‘make internal datasets public facing’ on a website. The call to action came and was executed before there were proscriptions on what to include and how to design the platform. Now, as many of the initiatives are mature, it’s a perfect time to reflect and evaluate how the initiative is successful and how the portals are useful to the public.

Open government data initiatives are complex; they involve many government agencies and require data analysts and IT specialists to prepare data and launch a site. For this reason, evaluations have come from a technologist perspective—but planners have formal training in meaningful public engagement and the value of transparent government processes.

For that reason, planners should get more involved in thinking about, designing, and promoting open data initiatives in their municipalities. Imagine, a planner can support local open data initiatives by joining the team or

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 16

giving feedback; they could leverage open data in planning initiatives; or planners could use the portal as a tool to engage with communities—like co-creating data about a community issue.

Planners should be inspired to assess the state of their local open data initiative. If your city showed up on this analysis with less than stellar results, maybe this is a sign to work with your local municipality. Or if your city didn’t show up at all, perhaps this is the sign to start an initiative in your town or city, guided by some precedent setting cities. Planning is an iterative process as is creating a useful and successful open data portal, it is an exciting prospect to think about the evolution of the portals as more planners become actively involved.

Kuk, George, and Marijn Janssen. 2011. “The Business Models and Information Architectures of Smart Cities.” Journal of Urban Technology 18 (2): 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2011.601109.

Lock, Oliver, Tomasz Bednarz, Simone Z. Leao, and Christopher Pettit. 2020. “A Review and Reframing of Participatory Urban Dashboards.” City, Culture and Society 20 (March): 100294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ccs.2019.100294.

Lourenço, Rui Pedro. 2015. “An Analysis of Open Government Portals: A Perspective of Transparency for Accountability.” Government Information Quarterly 32 (3): 323–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.05.006.

Máchová, Renata, and Martin Lnenicka. 2017. “Evaluating the Quality of Open Data Portals on the National Level.” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 12 (1): 21–41. https://doi. org/10.4067/S0718-18762017000100003.

Nahon, Karin, Alon Peled, and Jenniver Shkabatur. 2015. “OGD Heartbeat: Cities’ Commitment to Open Data.” JeDEM - EJournal of EDemocracy and Open Government 7 (2): 116–36. https://doi.org/10.29379/jedem.v7i2.410.

“Open Government Data: Towards Empirical Analysis of Open Government Data Initiatives.” 2013a. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance 22. Vol. 22. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k46bj4f03s7-en.

“———.” 2013b. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance 22. Vol. 22. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance. https://doi. org/10.1787/5k46bj4f03s7-en.

Publications Office of the European Union. 2020. Sustainability of (Open) Data Portal Infrastructures: Open Data Portal Assessment Using User Oriented Metrics. LU: Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/ doi/10.2830/51660.

Ricker, Britta, Jonathan Cinnamon, and Yonn Dierwechter. 2020. “When Open Data and Data Activism Meet: An Analysis of Civic Participation in Cape Town, South Africa.” The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien 64 (3): 359–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12608.

WORKS CITED

Bennett, Abbie. “Sunny day flooding’ worsens at NC beaches — a sign sea Chignard, Simon. 2013. “A Brief History of Open Data,” Paris Tech Review.

Gagliardi, Dimitri, Laura Schina, Marco Lucio Sarcinella, Giovanna Mangialardi, Francesco Niglia, and Angelo Corallo. 2017. “Information and Communication Technologies and Public Participation: Interactive Maps and Value Added for Citizens.” Government Information Quarterly 34 (1): 153–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.09.002.

Hivon, Julien, and Ryad Titah. 2017. “Conceptualizing Citizen Participation in Open Data Use at the City Level.” Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 11 (1): 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-12-2015-0053.

Hoe‐Lian Goh, Dion, Alton Yeow‐Kuan Chua, Brendan Luyt, and Chei Sian Lee. 2008. “Knowledge Access, Creation and Transfer in E‐government Portals.” Online Information Review 32 (3): 348–69. https:// doi.org/10.1108/14684520810889664.

Thorsby, Jeffrey, Genie N.L. Stowers, Kristen Wolslegel, and Ellie Tumbuan. 2017. “Understanding the Content and Features of Open Data Portals in American Cities.” Government Information Quarterly 34 (1): 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.07.001.

Wilson, Bev, and Cong Cong. 2021. “Beyond the Supply Side: Use and Impact of Municipal Open Data in the U.S.” Telematics and Informatics 58 (May): 101526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101526.

Zhu, Xiaohua, and Mark Antony Freeman. 2019. “An Evaluation of U.S. Municipal Open Data Portals: A User Interaction Framework.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 70 (1): 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24081.

Zuckerman, Ethan. n.d. “What Is Digital Public Infrastructure?,” 20.

Zuiderwijk, Anneke, and Marijn Janssen. n.d. “Participation and Data Quality in Open Data Use: Open Data Infrastructures Evaluated,” 9.

FEATURE ARTICLES

17

REDEFINING ‘SMARTNESS’

Urban Technology and the Need for Collaboration

MALCOLM SMITH-FRASER

Malcolm currently works as a machine learning data scientist at DoorDash. He is skilled at applying a variety of data analysis tools and programming languages, including Python, SQL and Matlab. Prior to DoorDash, Malcolm has worked in international development roles with Sankofa and through internships in Ghana and Kenya, focused on promoting innovation and entrepreneurship among youth, and assisting in agriculture and biosciences research. Malcolm holds a Master’s in Interdisciplinary Data Science from Duke University and a Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Engineering from California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo.

ABSTRACT

The development of effective urban technologies requires that we center thoughtful problem solving rather than blind technological integration. In pursuit of this goal, conversations around urban tech could benefit from extending beyond theory towards intentional application. This is not a recommendation, but a requirement for ensuring that new technologies are problem focused, and context specific—and thus deserving of being labeled “smart.” Furthermore, data, engineering, and urban professionals all need a seat at the table during every phase of the development process, from design to deployment and monitoring. Urban analytics presents opportunities for innovating established systems and creating more efficient cities. In addition to this, innovative technical collaboration methodologies should be explored.

Thankfully, urban and data researchers have developed a compatible set of tools for appropriately directing the “smartness” of our initiatives. In showing the similarities between the smart urban governance framework developed by Jiang et al. and ethical data and AI practices, this article hopes to empower data and urban professionals to initiate the cross-sectoral conversations needed to direct contextual-tuning and guardrail-setting processes.

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 18

REDEFINING ‘SMARTNESS’

No matter the amount of wishful thinking, algorithms and technology are not magic. ChatGPT the conversational AI, DALLE-2 the AI artist, and other neural networkbased models are all the rage—but their capabilities are enabled by a robust, intentional training and guardrailsetting process designed to meet a relatively standard and generalizable set of expectations. As these technologies make their way into products we regularly interface with, their utility and fairness will depend on how they are finetuned and on the thoughtfulness of the guardrails coded into them. Unfortunately, many smart initiatives do the opposite—emphasizing tech as a source of truth rather than a thoughtful solution that leverages technology as the powerful tool it is.

The urban sector is not safe from these challenges. In fact, many smart urban governance initiatives are isolated from the governance frameworks into which they are deployed. This reality is often rooted in the divergent goals of local governance actors seeking solutions and their tech partners tasked with building tools. From the technologists’ perspective, such a disconnect can result in undesirable effects such as algorithmic bias or trust and privacy issues. For urbanists, it means technocratic decision-making that ignores the intricacies of the diverse populations they support.

Concerns around technocratic governance are often rooted in ethics, and thus the teachings of ethicists from technology and urban sectors are rife with lessons. A prominent recommendation centered by emergent strategies from both domains is that of an effective governance structure. Without effective structure, the end result is the same: a technological intervention that not only fails to achieve its desired outcome, but that enables the perpetuation of the underlying biases and inequities we often look towards technology to eliminate.

A FRAMEWORK FOR SMART URBAN GOVERNANCE

In 2019, urban scientists at Utrecht University proposed a smart urban governance framework made up of three components . Born out of an analysis of smart city projects from across the globe, the framework is designed to help urban governance practitioners avoid the pitfalls of technocratic governance by integrating “the ‘smart’ from smart governance literature” with “the ‘urban’ from urban governance literature”(Jiang et al., 2020b). Importantly, the role of technology within the framework is that of a tool to support the process, rather than a source of “smartness.”

SPATIAL COMPONENT

The spatial component relates to what interventions are targeting, promoting the idea that the focus of any urban project should be on addressing specific urban challenges. Rather than merely focusing on the problem-solving powers of technologies (e.g., big data solutions, city sensors, or intelligent infrastructure), practices might focus on how urban challenges demand the functional support of technological innovations.

While this might seem straight forward, we must consider the complex requirements for effectively addressing urban issues - including but not limited to problem identification, prioritization, and resourcing. For a city whose explicit goal is to “grow the economy, distribute growth fairly, and in the process not degrade the ecosystem,” the spatial component involves balancing economic, social, and environmental goals (Jiang et al., 2020b).

FEATURE ARTICLES

19

FIGURE 1 - Smart Urban Governance Framework, adapted from Jiang et al., 2020b.

INSTITUTIONAL COMPONENT

The institutional component is based on the idea that continuous input and contribution from various groups is required for an intervention to truly be “smart.” More than just town halls centered on discussing proposed initiatives, the authors of the framework emphasize that in order to successfully address the most pressing urban issues, “actors from the state, market, and civil society have to collaborate in innovative ways.” This position contrasts with the technocratic notion of smart governance, which focuses on either the government or the private sector to provide innovative solutions.

The Smart Ulaanbaatar Program and the Hangzhou City Brain Project —two of the case studies that guided the development of the framework— both illustrate the importance of a balanced institutional component and demonstrate how that balance varies in different urban contexts.

Smart Ulaanbataar was a 2014 initiative with the goal of revitalizing Mongolia’s capital city. Fighting a stagnant economy since the fall of the Soviet Union and deteriorating infrastructure due to disorderly expansion, Ulaanbaatar officials sought to address a wide range of urban challenges. Ulaanbaatar’s plan had an adequate spatial component— targeting core needs like public housing, emergency services, social welfare, food subsidies, and energy.

Unfortunately, the institutional component of the plan was lacking. A gap in local technological capacity resulted in state partnerships with foreign tech companies who, in turn, took full control of introducing and implementing technological innovations in the city. Voices representing the perspectives of residents were not included, resulting in a suite of technologies that the local population did not have the digital literacy nor the connectivity to fully utilize (Jiang et al., 2020a).

In 2017, city officials in Hangzhou, China proposed the City Brain initiative with the help of local tech giant, Alibaba. The goal of City Brain was to address challenges caused by the city’s rapid economic development. A major idea behind the initiative was to diagnose challenges in the city, in particular

serious traffic congestion, like one would diagnose a disease. This would be achieved with a big data approach to the collection, processing, and analysis of traffic operation data. Similar to Smart Ulaanbaatar, the City Brain initiative also lacked a participatory component for local residents. However, the outcomes highlight the importance of local context. Hangzhou is a city with well-established ties between universities, tech companies, and the government. Even though this network of relationships has historically not prioritized input from the general public, it was able to be successfully leveraged to address Hangzhou’s goal of decreasing traffic congestion (which has been cut by 15 percent) (Jiang et al., 2020a).

Both of these examples demonstrate a technocratic approach to addressing a specific urban challenge. Where Smart Ulaanbaatar fell short in meeting an explicit need, City Brain failed in achieving a solution that also fostered local trust, with one survey reporting that nearly 80 percent of respondents were concerned with the impact of City Brain on their privacy (Toh & Erasmus, 2019). Researcher Ezra Ho points out that “the neoliberaldevelopmental logics of the state [to a large degree] facilitate authoritarian consolidation” (Ho, 2016).

This is a reality that could result in an initiative’s catastrophic failure if implemented in a local context that is openly hostile towards authoritarian governance. A desire to avoid technocratic governance is rooted in a

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 20

FIGURE 2- Spatial component of the Smart Urban Governance framework, adapted from Jiang et al., 2020b.

belief that equity and fairness are core values, and it is through the institutional component that local values can integrate into solutions.

TECHNOLOGICAL COMPONENT

The technological component relates to the functional intelligence of a tool. In essence it stresses that technology does not have to (and often should not) be the primary solution to the challenge at hand. Rather, how we use technology should serve to facilitate robust spatial and institutional components by providing urban actors with the proper support capabilities to deal with the diverse urban challenges they face. These technologies are categorized into three groups: informing; communicating; and analyzing and designing.

Informing technology is designed to make governancerelated knowledge and information accessible and interpretable. This could be a website or public application that interfaces with a project. Communicating technology is designed to facilitate communication and discussion processes between those involved in governance by supporting those flows of information. It is these first two goals that enable the innovative collaboration required by the institutional component.

Analyzing and designing technologies, often referred

to as planning support systems (PSS), are “intended to facilitate the advanced processing of data to detect urban patterns and the underlying processes, in order to facilitate the perception, creation, and presentation of design ideas” (Jiang et al., 2020b). For example, if an urban governance initiative aims to reduce homelessness, technology in this category would aid in measuring and tracking homelessness in the city.

The components of the smart urban governance framework are intended to work together to help urban governance practitioners create impactful innovations that are community-based, context-driven, and fair. As we look towards further integrating analytics and other forms of data-driven technologies into the urban sector, it is important to understand how the components in this framework align with strategies within the tech sector to better enable collaboration.

ETHICS, FAIRNESS, AND BIAS

As the applications for data-driven technology continue to broaden, the ethics of artificial intelligence has been a popular topic. Questions around algorithmic bias and transparency are two areas where data ethics research has been focused.

Technology might often be considered the holy grail of unbiased decision-making. In reality, any recommendation output by a piece of technology comes coded with the same biases present in the data or the scientist. When outcomes are systematically less favorable to individuals in a particular group and when there is no relevant difference between groups to justify such harms, the system generating those outcomes is considered biased. We might define unbiased (or at least bias-aware) technology more succinctly as fair technology.

Bias finds its way into our algorithms and systems in a wide variety of ways, but avoiding algorithmic bias begins with asking the right questions (Mehrabi et al., 2022). As Vincent Warmerdam, a founder of PyData Amsterdam points out in his appropriately titled presentation The profession of solving (the wrong problem), “algorithms

FEATURE ARTICLES

21

FIGURE 3 - Institutional component of the Smart Urban Governance framework, adapted from Jiang et al., 2020b.

are sort of starting to distract us from what we’re actually supposed to do.” While there can be a great deal of hype surrounding the next new algorithm, Warmerdam makes the argument that “it’s all the stuff around the algorithm that is actually the solution” (Warmerdam, 2019).

While Warmerdam focuses primarily on challenges in tech industry operations, data ethicist Ruha Benjamin brings this same perspective to challenges faced by urban governance practitioners. Benjamin—whose work on innovation and equity focuses on the intersection of race, justice, and technology— states that truly fair technology is not achieved by attempting to rebalance biased outcomes downstream, but must start at (or before) a problem is defined. Creating or searching for a dataset without obvious biases may be necessary to a point, but this should never overshadow the need to evaluate why the systems we attempt to automate have left us with so many biased datasets to begin with. This theme is echoed by clinical technology ethicists such as Llana James and Dorothy Roberts (Tang, 2021; Roberts, 2011).

In the context of urban technology, predictive policing systems like PredPol have been viewed as controversial because of runaway feedback loops and their potential to perpetuate historical biases in the criminal justice system (Ensign et al., 2018). Additionally, the rapid adoption of these tools suggests bias towards the assumption that increased law

enforcement and mass incarceration are adequate proxies for how safe a city is.

Regardless of any personal perspectives around that assumption’s validity, a common theme in data ethics literature is the importance of revisiting our guiding assumptions and North Star metrics. Another tool, The City of Boston’s Street Bump application that uses crowdsourcing to better identify potholes for maintenance prioritization, was also a victim of unintended algorithmic bias (Niu & Silva, 2020; Crawford, 2018). Street Bump relied on data from drivers actively using the smartphone app. Without an adequate focus on ensuring broad access and usage of the application, it inadvertently excluded more elderly and resource-poor parts of the city, where first adopters of the app did not frequent and where smartphone ownership is lower.

Tackling issues in this domain requires a focus on questions and design—a focus that can be gained through the smart urban governance framework. Systems like Ziad Obermeyer’s Algorithmic Bias Playbook move beyond the planning stage, laying out strategies for stakeholder engagement as well as techniques for target variable identification, bias evaluation and avoidance, and best practices for retraining or terminating a model (Obermeyer et al., 2021). These aspects of the playbook directly map to the institutional and technological components of the smart urban governance framework, just within a new problem space of data and technology.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Trust is an often-overlooked aspect of an interaction. Central to trust is accountability, which demands access to information. Our ability to peek inside the black box and interrogate inputs and outputs, along with a governance structure that enables actors to make changes when things behave undesirably, is crucial for accountability. Transparency, auditability, and feedback loops are three practices that data ethicists point to as a means to hold data-driven systems accountable.

Transparency defines our ability to look inside a process

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 22

FIGURE 5 - Technological component of the Smart Urban Governance framework, adapted from Jiang et al., 2020b.

or algorithm. Closely related is the idea of auditability, which focuses on the collection of data to enable robust interrogation of the system. Feedback loops relate to our ability to protest or challenge an algorithm when an output seems erroneous. In the face of a complaint claiming bias in an algorithm, it is not enough to conclude that a system is void of racial and gender bias simply because information on race or gender was never collected.

This is because factors like ZIP code or height and weight can be proxies for race or gender, respectively. To make any conclusion, we need to have the ability to compare outputs across race and gender, which requires that we collect information about these characteristics. This capacity to make an evidence-based conclusion is what we call auditability. Not only do these three factors emphasize the importance of moving away from “magical” black box algorithms, but they also emphasize addressing the power dynamics in the development process.

Outside of the tech giants, technology development is typically outsourced, with access to algorithms often blocked by proprietary clauses. Northpointe’s (now Equivant) COMPAS system, an algorithm designed to predict recidivism for inmates up for parole, is a perfect

illustration of the challenges this can present. Since it was deployed nearly a decade ago, multiple articles and papers have been published arguing the ethics and effectiveness of the COMPAS algorithm. Most notably, a 2016 analysis by ProPublica found that the algorithm was racially biased (Larson et al., 2016). In 2020, Cynthia Rudin, a renowned machine learning researcher at Duke University, published a contradictory report that called out a deeper issue: the system’s lack of transparency (Rudin et al., 2020).

This lack of transparency eroded trust at two levels. First, defendants and their lawyers were legally denied access to any information about how the risk scores that played pivotal roles in their judgments were generated. Take the case of Glenn Rodriguez, who was denied parole almost entirely on the basis of a high COMPAS score despite having an otherwise clean record. Rodriguez and his attorney suspected that the high score was due to a clerical error in one of the 137 inputs to the algorithm, but without access to the inner workings of the COMPAS system they were unable to investigate that claim (Wexler, 2017).

Second, the proprietary nature of the algorithm severely limited the rigor in which any third-party investigation

FEATURE ARTICLES

7 - xxx 23

FIGURE

could be conducted. Blocked from accessing the true design, ProPublica investigators made various assumptions about how the 137 COMPAS inputs generated risk scores. Rudin elaborates that “faulty assumptions about a proprietary model led to faulty conclusions that went unchecked until now. Were the model transparent in the first place, this likely would not have occurred” (Rudin et al., 2020). Regardless of what is true or effective, the tool’s lack of transparency has severely impacted its reputation. Even today, the top result when researching the COMPAS algorithm is ProPublica’s report.

Similar to fairness and bias, strategies for ensuring accountability in data-driven technologies closely map to the smart urban governance framework. Central to the framework’s technological component is the dissemination of information about how systems work and the facilitation of feedback. Auditability aligns well with these tenets and enables practitioners (i.e., auditors) to do their jobs effectively.

CONCLUSION

In our push to build smarter cities and better urban governance tooling, how we define “smartness” is of critical importance. A definition that centers context specific problem solving is likely to lead to the creation of effective and equitable solutions. On the contrary, a definition that centers rapid technological infusion can lead us down the path of technocratic governance.

In healthcare, medicine, education, and agriculture, a prefix of “smart” is synonymous with increased precision in addressing core needs. Rather than being an industry that tackles specific and urgent urban challenges, smart cities are too often limited to existing as consumers of solutions dreamt up by billionaires and tech giants. In her work on uneven innovation, Jennifer Clark argues that the sector of urban technology should be viewed as an industry and should behave as such when expanding and integrating into incumbent systems. To this end, she emphasizes the importance of valuing regional differences as the constraints around which these technologies are defined, rather than just another problem to solve in search of a one-size-fits-all answer (Clark, 2021).

Jiang et al.’s smart urban governance framework suggests that cities do not need the newest algorithms; they need data and urban governance professionals collaborating in innovative ways. As data and urban practitioners, we have the tools to define the trajectory of what “smartness” means in our cities—a definition that depends on how we ask questions, understand the unique contexts of our communities, and creatively leverage technologies to enable new solutions.

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 24

WORKS CITED

Crawford, K. (2021, August 27). The hidden biases in big data. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://hbr.org/2013/04/ the-hidden-biases-in-big-data

Elish, M. C. (2020, September). Repairing innovation: A study of integrating AI in clinical care. Data & Society. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https:// datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Repairing-InnovationDataSociety-20200930-1.pdf?trk=public_post_comment-text

Ensign, D., Friedler, S. A., Neville, S., Scheidegger, C., & Venkatasubramanian, S. (2018, January 21). Runaway feedback loops in predictive policing. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/ensign18a.html

Ho, E. (2016). Smart subjects for a smart nation? governing (smart) mentalities in Singapore. Urban Studies, 54(13), 3101–3118. https://doi. org/10.1177/0042098016664305

Jiang, H., Geertman, S., & Witte, P. (2020). A sociotechnical framework for Smart Urban Governance. International Journal of E-Planning Research, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijepr.2020010101

Jiang, H., Geertman, S., & Witte, P. (2020). Smart urban governance: An alternative to technocratic “smartness.” GeoJournal, 87(3), 1639–1655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10326-w

Larson, J., Angwin, J., Kirchner, L., & Mattu, S. (2016, May 23). How we analyzed the compas recidivism algorithm. ProPublica. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-analyzed-thecompas-recidivism-algorithm

Mehrabi, N., Morstatter, F., Saxena, N., Lerman, K., & Galstyan, A. (2022, January 25). A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. arXiv. org. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.09635v3

Niu, H., & Silva, E. A. (2020). Crowdsourced data mining for urban activity: Review of data sources, applications, and methods. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 146(2). https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce) up.1943-5444.0000566

Obermeyer, Z. (2021, December 2). Algorithmic bias playbook presentation. Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.privacydesign.ch/2021/12/02/ziad-obermeyer-universityof-california-at-berkeley-algorithmic-bias-playbook-presentation/

Roberts, D. E. (2011). What’s Wrong with Race-Based Medicine?: Genes, Drugs, and Health Disparities . The University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository . Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?httpsredir=1&article=1095&context=mjlst

Rudin, C., Wang, C., & Coker, B. (2020). The age of secrecy and unfairness in recidivism prediction. 2.1, 2(1). https://doi. org/10.1162/99608f92.6ed64b30

Tang, H. (2022, June 6). Race, medical data and AI with University of Toronto’s Llana James. AIMed. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https:// ai-med.io/essential-listening/race-medical-data-and-ai-with-universityof-torontos-llana-james/

Toh, M., & Erasmus, L. (2019, January 15). Alibaba’s ‘City brain’ is slashing congestion in its hometown. CNN. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/15/tech/alibaba-city-brain-hangzhou/ index.html#:~:text=Alibaba%27s%20%27City%20Brain%27%20is%20 slashing%20congestion%20in%20its%20hometown&text=Traffic%20 used%20to%20be%20a,to%2057th%20on%20the%20list.

Warmerdam, V. (2019, June 24). Vincent Warmerdam: The profession of solving (the wrong problem) | PyData Amsterdam 2019. YouTube. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kYMfE9u-lMo.

Wexler, R. (2017, June 13). When a computer program keeps you in jail. The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.nytimes. com/2017/06/13/opinion/how-computers-are-harming-criminal- justice. html

FEATURE ARTICLES 25

INTERROGATING SMART CITY PRACTICES

JUN WANG

Jun Wang is a Ph.D. candidate at the Georgia Institute of Technology specializing in Urban Design and Transportation. Jun earned her Bachelor of Engineering in City and Regional planning at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in China. She also earned an MS in Urban Design and an MIS in GIS Technology at Georgia Tech. Jun’s work involves interdisciplinary theories and practices in urban design, city planning, GIS technology, and transportation modeling.

ABSTRACT

This article uses Sidewalk Labs’ Quayside project in Toronto, Canada as a case study to elaborate on the challenges that smart city projects face in the real world. The controversial project faced challenges with data privacy law, loss of trust among agencies and the public, as well as insufficient communication. These appear to be generalizable obstacles impeding success of smart city projects. The project sheds light on future smart city practices with strategies proposed for the public and private sector, as well as planners and designers.

The failure of the Quayside project prompts future smart city practices to build trust among the designing agency, the public sector, and residents. Design firms should be transparent with the public, and they must be responsible for the techniques they apply. The government shoulders responsibility for initiating appropriate data privacy laws and monitoring collaboration with the private sector in smart city contexts. Designers and planners, must be alert to tech chauvinism and technological solutionism. The actual demands of the residents should always be prioritized.

A VISION UNFULFILLED

Originally billed as a first-of-its-kind “smart city” prototype, Sidewalk Labs promised a new kind of IT and IoT-laden district for Toronto. Sidewalk Labs partnered with Waterfront Toronto, a public-private partnership, in 2017 to redevelop 12 acres of former docklands on the Toronto waterfront. Sidewalk Labs is linked to Google, and serves as Alphabet’s urban innovation organization aimed at designing, testing, and building tech-centric projects to help cities overcome persistent challenges.

Sidewalk Labs envisioned Quayside as a neighborhood infused with experimental technology that could eventually change how humans everywhere live, work, build, commute, and make use of public space. In this sense, it was a pilot project for a far more global vision.

In an extensive master plan, Sidewalk Labs depicts the scene of future waterfront residents playing among the wooden skyscrapers on the site. In a deja-vu of spinning rural space-habitats from 1970s futurism, the plan shows the Quayside project in its completed state. In a verdant

The Sidewalk Labs Quayside Project

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 26

low-carbon city, plants proliferate, people and their pets stroll along the riverside avenue. There’s no clear sign of high technology. The message appears to be that this smart city is no different from any other place—except that it is, perhaps, better. Aspirations toward a “sense of community” take center stage. Sidewalk Labs uses the familiar language new urbanism to show a comforting, familiar scene, avoiding cyberpunk-style unsettledness.

The organization’s vision statement made lofty claims to design a “place with safer streets. More breathable air. More walkable sidewalks. A place where people are more engaged with their world than with their phones... A place where, quite simply, everyone who wishes to call it home, can” (Sidewalk Labs, 2019). The company also aspired to tremendous economic impact. They estimated that it would create some 44,000 jobs for locals, generate $4.3 billion in annual tax revenues, and spur at least $38 billion in private sector investments by 2040 (Sidewalk Labs, 2019).

Such claims generated a flood of media attention. Some eagerly endorsed this potential gamechanger for Toronto’s housing, transportation system, and employment market. Others noted the potential for controversies now familiar in the smart cities debate: personal privacy; data security; and the power of private companies over public assets. Skeptics believed Sidewalk Labs’ smart master plan— packaged in a series of beautiful street view renderings— masked intentions to collect and manage sensitive data.

In the end, controversy overtook aspiration. Sidewalk Labs terminated its effort to design and build a smart community in Toronto in May 2020, blaming unprecedented economic uncertainty (Doctoroff, 2020).. Was economic uncertainty truly to blame? Or was the leap from smart city concept to smart city development too large?

DATA PRIVACY AND PROFIT MOTIVES

Smart cities rely on data—lot’s of data. The Quayside project required huge amounts of personal information from citizens in order to achieve promised efficiencies. This was especially true of certain tools such as Replica,

a movement modeling approach based on cellphone data, which would have let Sidewalk Labs monitor realtime traffic volume in suggesting navigationroutes. The generative design tool, like Replica, could optimize urban design patterns with machine learning, potentially supporting decisions of the local planning department. Such tools could even monitor the energy consumption of every building, allowing improved performance standards for city buildings.

Many raised their eyebrows at the project’s total scope. Unlike existing smart city projects that often only focus on one aspect of urban governance, the Quayside project presented a complete plan addressing architecture, urban design, city management, transportation, stormwater, logistics, and even waste management. Ambition abounded. “It’s never been possible to bring everything together in one place,” said Dan Doctoroff, CEO of Sidewalk Labs (Bliss, 2019).

But compounding concerns about scope, critics fretted about proprietary data access. Many Canadian residents expressed distrust of Google. Concerns arose over Sidewalk Labs’ refusal to publicly disclose their data collection, usage framework, or privacy protection measures during the first year and a half of the Quayside project, resulting in widespread concerns over personal information security (Devlin, 2019).

MANAGING SKEPTICISM

Sidewalk Labs sought to thread the needle of data privacy restrictions. Per Canadian law, private information cannot be sold or leased to third-party profiters without authorization. Thus, after a series of discussions and negotiations with Waterfront Toronto, Sidewalk Labs made efforts and actions to protect personal information. On March 23rd, 2019, Sidewalk Labs published an article describing the mechanism of data collection and protection and insisted that collecting data is not part of Sidewalk Labs’ business model. All original information collected was to be anonymized and managed by a thirdparty organization Urban Data Trust. By incorporating third-party data management by the Urban Data Trust,

FEATURE ARTICLES

27

Sidewalk Labs sought to ensure that urban data would be used in a way beneficial to the community without losing its opportunity to pilot this tool.

The pivot did little to assuage concerns. Sidewalk Labs discussion of third-party management were highly conceptual, leaving suspect the management structure and composition method (Walker, 2019). Although Sidewalk Labs completed a Responsible Data Impact Assessment as an accessible resource for cities, the company subsequently removed the assessment from its website. Suspicions that third-party management would not resolve privacy concerns were well-founded. Sidewalk Labs claimed that data is minimized, secured, and de-identification occurs by default. However, data can be relatively easily reidentified by using neural network and other predictive algorithms. For example, researchers at MIT and the Université Catholique de Louvain analyzed data on 1.5 million cellphone users in a small European country to demonstrate this potential. They found that, with just four points of reference and a low spatial and temporal resolution, one could retroactively identify 95 percent of de-identified data (Lubarsky, 2010 & Cecaj et. al, 2014).

CANADA’S FAILING DATA PRIVACY LAW

This flaw in the privacy arrangement stems from outdated and inadequate provisions in Canada’s privacy laws (Scassa, 2019). Much of the data Sidewalk Labs required was personal travel data and real-time movement data of all citizens on this site, whether a person walked or drove. But personal travel data is not protected in Canada’s Privacy Act, which limits government use of data. Moreover, this Act has extremely weak law enforcement. In many cases, public harm due to algorithmic bias and manipulation of personal data stems from the use of personal information. The ethical use of data requires a better framework, such as the consent-based mechanism of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

In many respects, Canada’s legal infrastructure has siloed various aspects of data privacy. Critics have called on the government to develop laws and policies to address the ambiguities in managing and utilizing public and private

data, promote remedial measures, and minimize judicial barriers (VanDiver, 2019). In the absence of such legal reforms, Toronto residents cannot depend on laws to protect their data security. They also cannot confirm whether Sidewalk Labs sought to take advantage of legal loopholes. This did much to undermine public confidence in the Quayside Project.

UNEXPECTED SITE EXPANSION

Those already observing the project with a critical eye found still further cause for concern with a surprising development on June 24, 2019. Sidewalk Labs proposed a 16-fold expansion of the site footprint for the experimental Smart City. No one expected this—not even Sidewalk Labs’ public partner. As the actual landholder, Waterfront Toronto failed to fulfill its responsibility to monitor the progress of Sidewalk Labs’ work, and Sidewalk Labs ran with their concept. They did so without agreement from either the local government or the public.

The most plausible explanation is that the original site was too small to realize a complete smart city plan—especially one so comprehensive as Sidewalk Labs’ envisioned. Perhaps the larger site was genuinely necessary to realize the full services that the initiative pursued. It was, however, a fatal mistake to exclude the users of the proposed design. The sudden change triggered an outpouring of dissent on Internet forums and in the media. The move elevated already widespread distrust from the public.

PUBLIC BACKLASH

To understand the scope and evolution of public backlash, consider the #BlockSidewalk campaign. These citizen activists alleged that the project handed over what was meant to be a democratic, government-led development process to a private company. The movement emerged from a Twitter group of 30 locals who held their first public meeting in April 2019. Many members saw inspiration in the grassroots movement that caused Amazon to cancel its plan to build a second headquarters in Queens, New York. According to Professor Shauna Brail at the University of Toronto, the size and scale of #BlockSidewalk is challenging

Carolina Planning Journal : Volume 48 / Urban Analytics 28

to estimate (Personal conversation with Professor Brail on July 23, 2020).

Nevertheless, #BlockSidewalk was no isolated event and shares much with other campaigns that stigmatize smart cities projects. Conservatives in the United States have long associated Silicon Valley and technology firms with liberal elitism. In 2012, talk show host Glenn Beck fired up his conservative base against “sustainable development” and “smart growth” with his dystopian novel portraying conspiracy theories about Agenda21, the United Nation’s Millennial goals. This politicization of smart city concepts and sustainable development has further complicated understanding and public acceptance.

The #BlockSidewalk group continued to be organized and vocal, but they appeared to struggle against prevailing disinterest. The majority of the citizens didn’t know anything about Sidewalk Labs. Certainly, the presence of an internet-based opposition usually cannot be credited with the cancellation of such a large project, as most large projects seem to generate such groups. However, when Sidewalk Labs eventually cancelled the project, #BlockSidewalk claimed that the withdraw of the Quayside project was a victory for democracy over “surveillance capitalism.”

FAILURE AND LESSONS FOR FUTURE SMART CITY PROJECTS

The failure of the Quayside project leaves planners and designers with three lessons for the era of smart cities. First, governments must take responsibility for protecting the interests of citizens. Second, all involved must commit to actions that will foster trust, and avoid secrecy and disruptive actions like the surprise site expansion. Third, planners and designers must be alert to chauvinistic bullying by big tech, and should be wary of elitist wouldbe managers of smart city mega-projects.

LESSON 1: GOVERNMENTS MUST TAKE RESPONSIBILITY

The Quayside project teaches us that the public sector has a lot of work to do to earn the public’s trust when dealing with smart city technology. Policy-makers need to take

data and intellectual property seriously. Data is used to determine everything from traffic flows to access to welfare. The government should prepare data and intellectual property laws before starting partnerships with private entities that specialize in data.

Canada’s Privacy Act is too rigid and narrow. The Privacy Act defines personal information as any recorded information about an identifiable individual. Personal mobility data does not meet the Act’s definition of personal privacy, and mobility data is a huge part of what Sidewalk Labs requests. Under these terms, citizens have no privacy rights for their own mobility data. Further, under this Act, no clear plan exists to implement, monitor, and enforce its provisions. Should new legislation emerge, it must be accompanied by clear enforcement.

Governments must also act in ways that reflect the public will when corporations show an interest in circumventing it. Google CEO Larry Page said that “[t]here are many exciting things you could do that are illegal or not allowed by regulation…we don’t want to change the world, but maybe we can set aside a part of the world…we need some safe places where we can try things and not have to deploy to the entire world” (Ingraham, 2013).