The Carolina Planning Journal is the annual, student-run journal of the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

COPYRIGHT AND LICENSE

© Copyright 2025, Carolina Planning Journal. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons AttributionNon-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

PRINTING

A Better Image Printing Durham, North Carolina

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this publication was generously provided by the Nancy Grden Graduate Student Excellence Fund, which supports graduate students working directly with the department’s Carolina Planning Journal, the John A. Parker Endowment Fund, and the North Carolina Chapter of the American Planning Association, and by our subscribers.

CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

Department of City and Regional Planning

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

CB #3140, New East Building Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3140 USA

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Samantha Pace

EDITORIAL BOARD

Joe Wilson

Candela Cerpa

Noah Ellington

Nicki Harris

Benjamin Jacobs

Mohammad Haider

Kamaruzzaman

Helen Klass-Warch

Jo (Joungwon) Kwon

Annie Oommen

Jazmine Pritchett

Aditya Roy

Josh Salzburg

Sarah Slay

Joseph Womble

CONTRIBUTORS

Alejandro Cotté Alsina

Kristi Brantley

Sofia Cardamone

Candela Cerpa

Zhiyuan Chen

Audrey Compiano

Lee Corum

Jackson Dille

Emily Ensminger

Lyndsay Gavin

Anya Grahn

Nancy Grden

Sylvie Guezeon

Andrew Holland

Renata Pouton Kamakura

carolinaplanningjournal@gmail.com

www.carolinaangles.com

Anna Lynch

Jim Miller

Samantha Niven

Erick Peña

Tony Perez

Aaron Sinclair

Nea Strawn

Roger Waldon

Joseph Womble

Lizbeth Woodby

SPECIAL THANKS

The Carolina Planning Journal would like to thank the North Carolina Chapter of the American Planning Association; DCRP

Chair Todd BenDor; DCRP staff members Diana Devereaux, Elle Hughes, Sandra Lazo de la Vega, and Sarah Ward; and, of course, all of our subscribers. COVER PHOTOGRAPHER

Jo (Joungwon) Kwon

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Department of City + Regional Planning

To George Hemmens, the chair of UNC’s City and Regional Planning Department from 1974-1978, for his unwaivering support of this journal’s launch, 50 years ago.

Jackson Dille, Emily Ensminger, and Lizbeth Woodby

FORM-BASED

Zhiyuan Chen and Aaron Sinclair

REDEVELOPING

Sofia Cardamone, Nea Strawn, and Audrey Compiano

REFLECTIONS: 50 YEARS OF CAROLINA PLANNING

Kristi Brantley and Anya Grahn-Federmack

Nancy Grden, Jim Miller, and Lee Corum FORM-BASED

STUDENT WORK

FROM THE EDITOR

SAMANTHA PACE is the Editor-in-Chief of the Carolina Planning Journal. Samantha is a third year dual master’s student in City and Regional Planning at UNC Chapel Hill and Environmental Management at Duke. After receiving her undergraduate degree in Industrial Design from North Carolina State University, she worked at a sustainable building materials start-up in Research Triangle Park. She is passionate about resilience planning, urban design, and sustainable infrastructure.

DEAR READERS,

This year marks a momentous occasion as the Carolina Planning Journal (CPJ), the oldest student-run planning publication in the nation, celebrates its 50th anniversary. We are excited to celebrate this milestone with you, the CPJ community, through this volume.

Volume 50 offers several featured articles investigating the theme of Design in Planning and the Environment, a collection of student work showcasing place-based planning and urban design, Reflections on 50 Years, an interview with the founders of CPJ, and concludes with highlights from the UNC Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning (DCRP), the next NC-APA Conference, and the Volume 51 Call for Papers.

Authors of the featured articles explore design as a topic or framework within planning and the environment. The disciplines of design and planning are intertwined through their overlapping impacts and focus on urban form and the environment - built and natural - as well as their approaches to address challenges. The strategies we use to define, design, and plan for the challenges we face, ultimately shape the world we inhabit and ourselves. These papers demonstrate how a design amplifies the values of its designers, and how who is impacted is often not who is empowered in the design process. The design lens makes space for both critique and creativity, helping us to begin to imagine the path between what is and what could be.

In “Designing Living Things,” Candela Cerpa and Dr. Renata Poulton Kamakura explores the relationship of humans and non-human species in our cities. Examining nature-based solutions and green/blue infrastructure, they argue that these frameworks generally center on the utility of non-human species for human interests and overlook the agency of non-humans. They offer ideas of how we can better design spaces for non-humans’ agency to co-exist with human interests, drawing on case studies in Colombia and Hawai’i.

In “Reimagining Paper Streets in Durham,” Andrew Holland, Lyndsay Gavin, and Erick Peña discuss how the City of Durham has approached tapping into the potential of paper streets, roads that were planned but never constructed, as opportunities to support community needs. They demonstrate how redesigning these spaces intertwines with community empowerment, city staff and leadership, and existing and potential policies.

In “The Cost of a Degree,” Samantha Niven argues that universities often fail to build meaningful relationships with the neighboring local communities, leading to their exclusion from the university’s design and planning decisions. Samantha evaluates key moments of growth in two mid-Atlantic universities, discerning circumstances in which communities experienced displacement and harm, or collaboration and inclusion.

In “It’s (50 Years) Time to See the (In)visible,” Sylvie Guezeon investigates the absence of university students’ participation in the design process of campus transportation through firsthand research at the University of Minnesota TwinCities. Through a participatory development process, she offers a pilot transit ambassadors program addressing this gap, building capacity for student riders to co-design the transportation system, making the process more engaged and inclusive.

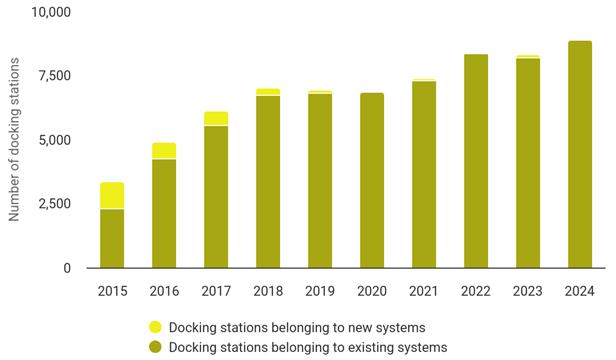

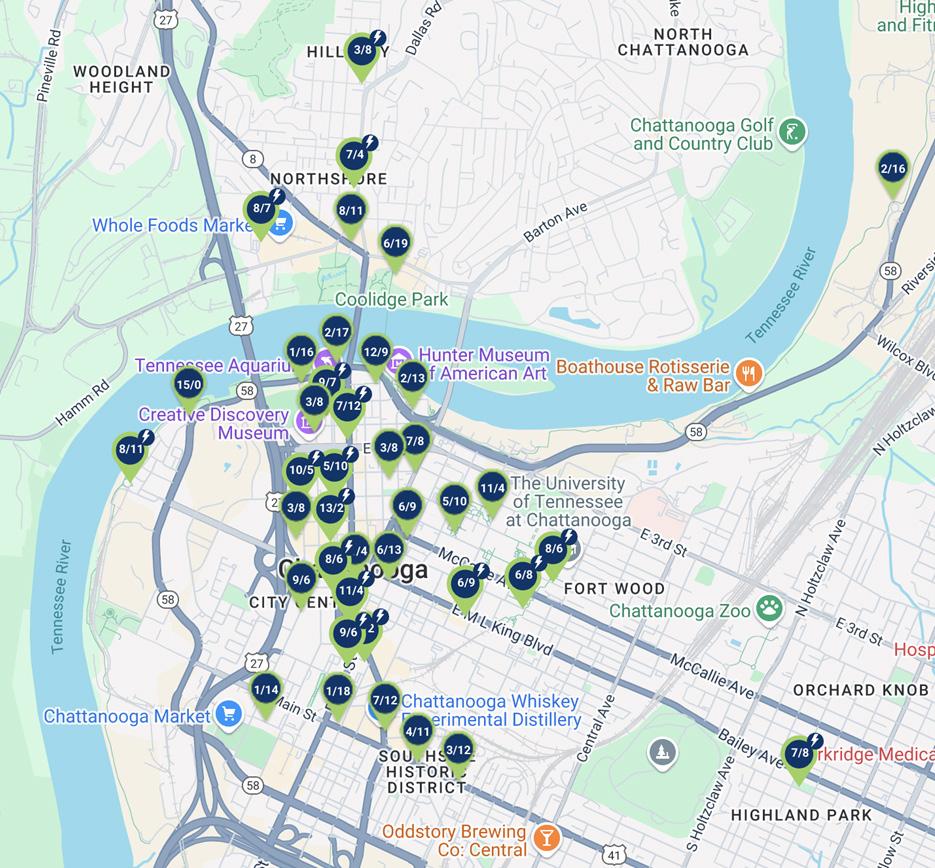

In “Principles to Design a Successful Bike Share Network in a Small or Medium City,” Joseph Womble evaluates bike share systems located in Chattanooga, TN, Aspen, CO, and Pittsburgh, PA, synthesizing insights for how to design bike share systems for municipalities with less than 500,000 residents.

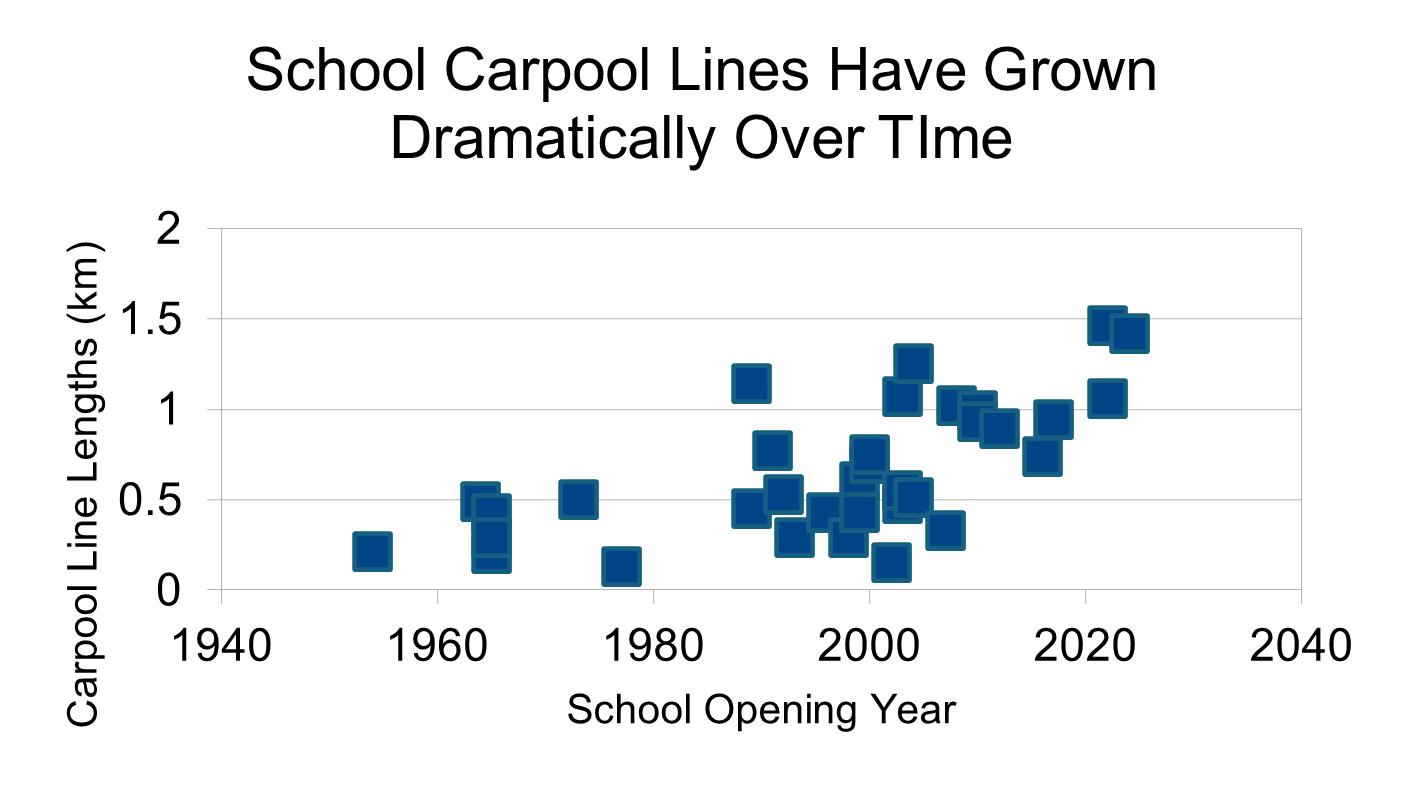

In “How the Sprawling Designs of Today’s School Carpool Lines Make Traffic Worse,” Anna Lynch applies the idea of induced demand to the lengthening carpool lines in the design of schools. She asserts that lengthening carpool lines is not easing the congestion, as it was designed to do, and continues to create negative impacts for students and parents. Drawing this observation to our attention, she assesses school transportation alternatives, providing healthier and safer options.

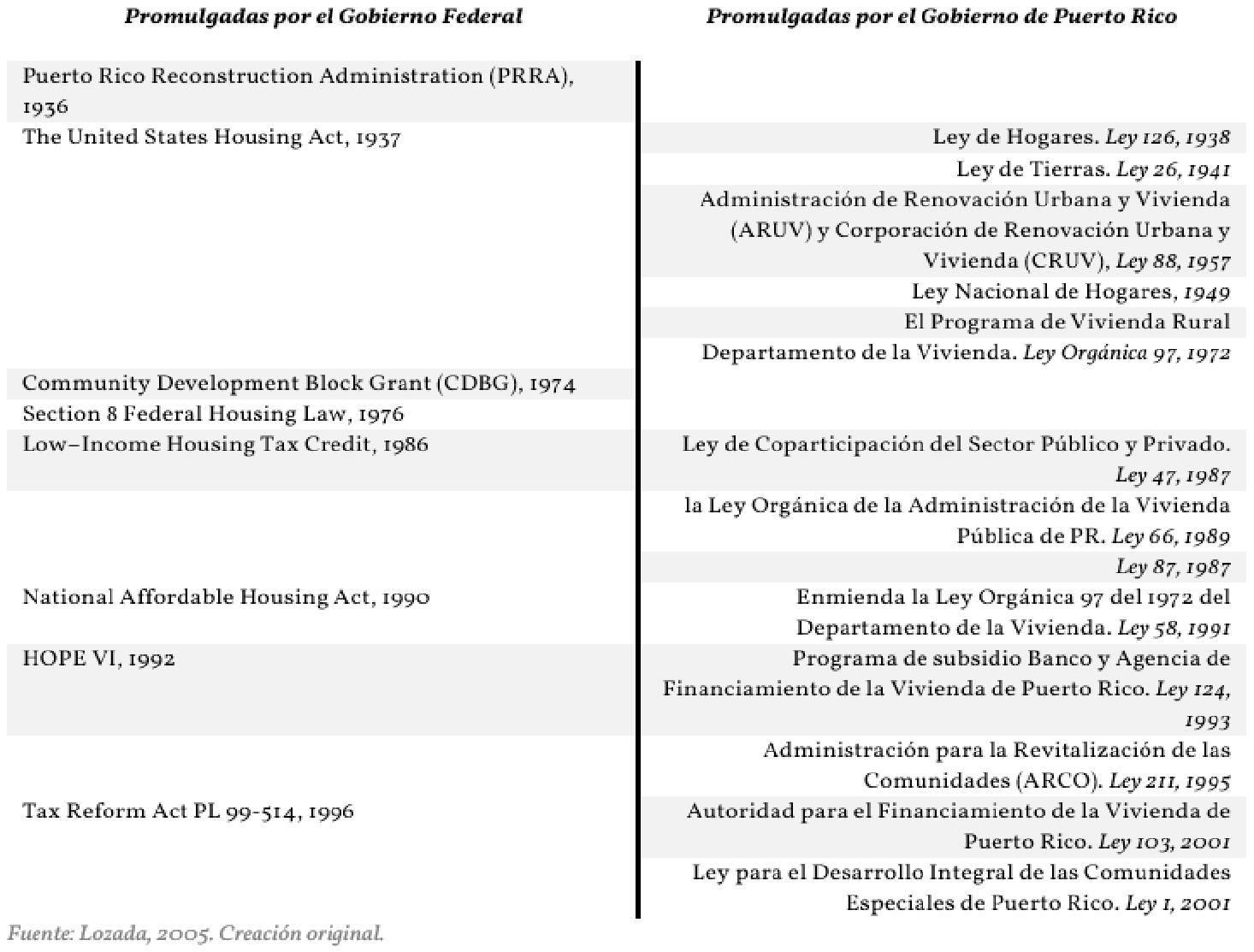

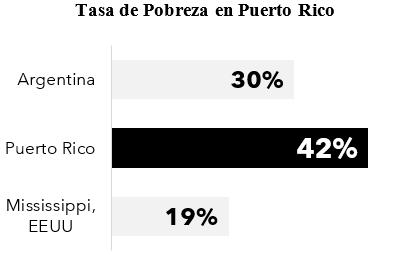

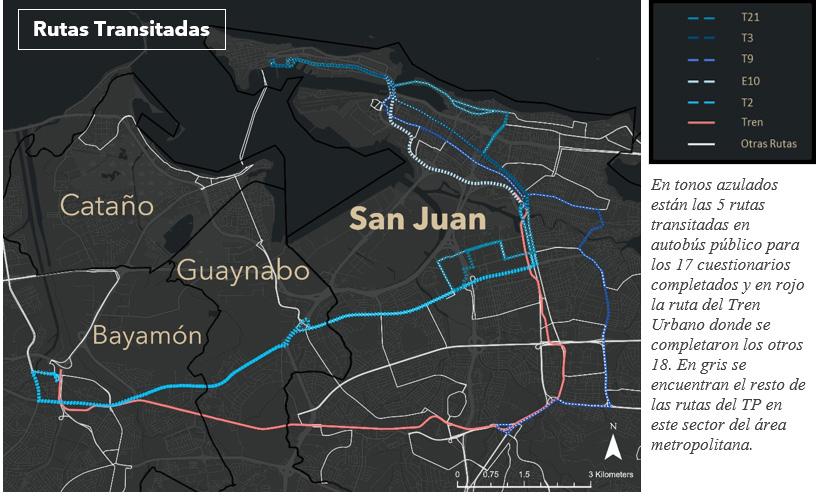

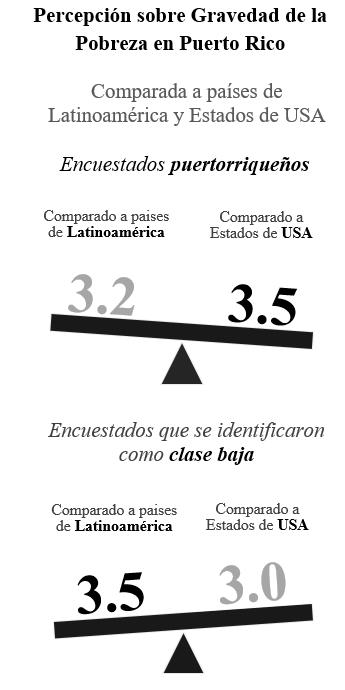

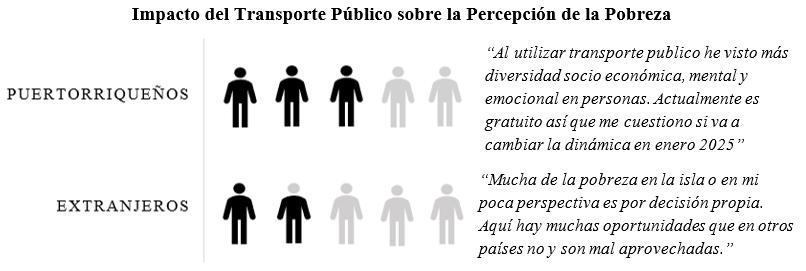

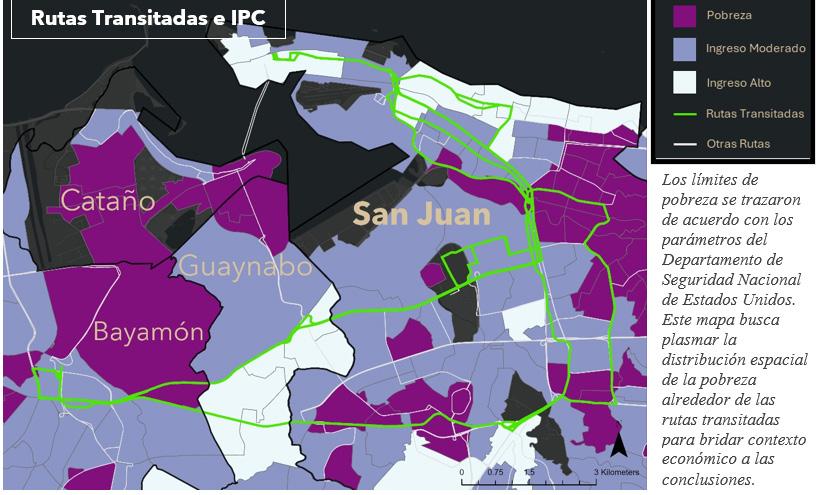

In “El Transporte Colectivo,” Alejandro Cotté Alsina presents his findings on the perception of poverty among public transportation users in San Juan, Puerto Rico after the Integrated Transportation Authority made services free in March 2024. Transportation systems and development policies in the area have reduced the contact zones of social classes, and a substantial increase in users of the free public transportation created a new opportunity for social classes to engage with each other. Alejandro proposes that designing public transportation as spaces of engagement between social classes can reshape how residents view poverty in Puerto Rico.

Turning now to the Place-Based Planning and Urban Design section, we feature the work of three student teams applying place-based planning tools and urban design frameworks on selected sites across the country in a new class taught by Tony Perez of Opticos Design.

We bring you a special section in this volume, Reflections: 50 Years of Carolina Planning, for which we asked contributors to be in conversation with CPJ’s history and its previous articles. In “Evolving Perspectives in Historic Preservation: A 35-Year Reflection,” Kristi Brantley and Anya Grahn-Federmack engage with ideas from Robert Stipe’s 1989 piece on historic preservation from CPJ Volume 15.1, providing a modern perspective and weaving together key developments on the topic. In “What it Meant for Me, and the Planning Practice,” Roger Waldon reflects on the role of UNC’s Department of City and Regional Planning and CPJ in his 50 years in the planning field. This section concludes with an interview with the founders of CPJ – Nancy Grden, Jim Miller, and Lee Corum – who recount the beginning of the journal, how it has changed over time, and their hopes for the future. As we celebrate this milestone, we aim to honor our history. In so doing, this volume is dedicated to George Hemmens (1932-2024), the chair of DCRP in the 1970s, whose invaluable support helped to bring the journal to life.

To conclude Volume 50, we celebrate the achievements of DCRP and look to the upcoming join NC-APA/SCAPA Conference and Volume 51. Online, you can dive deeper with our Angles blog, managed this year by Joe Wilson. Thank you for reading, and thank you to our authors and editors for all their efforts to make this possible. Here’s to many more years of the Carolina Planning Journal.

Warmly, Samantha Pace

EDITORIAL BOARD

The following people are integral to the success of the Journal and its online platform, CarolinaAngles.com:

SAMANTHA PACE / CPJ Editor-in-Chief

Samantha (she/her) is a third year dual master’s student in City and Regional Planning at UNC Chapel Hill and Environmental Management at Duke. After receiving her undergraduate degree in Industrial Design from North Carolina State University, she worked at a sustainable building materials start-up in Research Triangle Park. She is passionate about resilience planning, urban design, and sustainable infrastructure.

JOE WILSON / Angles Managing Editor

Joe is a second year master’s student in City and Regional Planning specializing in housing and community developoment. His research interests include community stability, access to social services, and the development of social capital in neighborhood contexts. His master’s project, The Functions of Neighborhood Schools, examines the intersections between educational policy and city planning.

CANDELA CERPA / Editor & Writer

Candela is a third-year dual master’s student in City and Regional Planning at UNC-Chapel Hill and Environmental Management at Duke University. She is interested in equitable natural hazards planning and urbanism in the Global South. Born and raised in Uruguay, she received her B.S. in Environmental Science and Policy from the University of Maryland, College Park. Outside of work and school, she enjoys learning new recipes, listening to audiobooks, and fostering cats.

NOAH ELLINGTON / Editor

Noah Ellington is a dual MPA/MCRP student at UNCChapel Hill, focusing on local government, housing, and community development. He works on the NC Benchmarking Project and is passionate about using data and public engagement to improve municipal services. Originally from North Carolina, Noah enjoys live music, running, and exploring small towns across the state.

NICKI HARRIS / Editor

Nicki is a master’s student in City and Regional Planning at UNC-Chapel Hill. She is interested in housing policy and financing tools. Prior to graduate school, Nicki worked at a nonprofit affordable housing developer in DC. She is a graduate of Carleton College.

BEN JACOBS / Editor

Ben is a first-year in the City and Regional Planning at UNC Chapel Hill. He is interested in active transportation planning, emergency service transportation planning, and creating safe and effective multi-modal networks. Outside of class, he enjoys playing music with friends, spending time with family, and hanging out with his dog, Willow.

MOHAMMAD HAIDER KAMRUZZAMAN / Editor

Haider is a PhD student in City and Regional Planning at UNC Chapel Hill. He is particularly interested in how data-driven methods can support sustainable transportation planning. His work aims to inform policies that promote equity, accessibility, and environmental sustainability in urban mobility. He is passionate about integrating advanced modeling tools with real-world transportation challenges.

HELEN KLASS-WARCH / Editor

Helen Klass-Warch is a second-year master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UNCChapel Hill specializing in Transportation and Natural Hazards Planning. She has worked for the Coastal Resilience Center under Dr. Miyuki Hino studying and cleaning datasets related to equity in public funding programs for flooding mitigation in North Carolina. Last summer she lived in Merida, Mexico, researching how flooding affects people’s mobility during Merida’s annual rainy season, studying behavior response, and governance issues. Helen was born and raised in Saint Paul, Minnesota and holds a BA from Wesleyan University in biology and history.

JO (JOUNGWON) KWON / Editor

Jo (Joungwon) Kwon is graduating from the Department of City and Regional Planning with a PhD. Having been a part of CPJ since 2019, her research interests include visualizations and augmented reality (AR) in plans, urban informatics, and plan evaluation. With a background of Statistics and English Literature, she received her MA in Computational Media at Duke University. Outside of her planning expertise, Jo enjoys indie films, live performances, designing t-shirts, and a good cup of Joe.

ANNIE OOMMEN / Editor

A proud double Tar Heel, Annie is from the Triangle area in North Carolina. After completing her BA in Public Policy in 2020 from Carolina, she taught English in Nantes, France and worked in health policy in Washington, D.C. Annie’s research and professional interests include youth mobility, complete streets, and active transportation. She is passionate about leveraging the built environment to promote climate resiliency and social connectivity.

JAZMINE PRITCHETT / Editor

Jazmine is a dual maseter’s student in Environmental Management at Duke University and City and Regional Planning at UNC. Her academic interests include climate resilience, environmental justice, and the use of planning tools to support equitable adaptation in communities.

ADITYA ROY / Editor

Soon to be double Tar Heel with a passion in comprehensive long-range planning, sustainable development, and making the future more certain.

JOSH SALZBERG / Editor

Josh Salzberg (they/them) is a dual degree student in the UNC Chapel Hill Master of City & Regional Planning and Duke University Master of Environmental Management programs. They conduct research on the political economies of electric grid planning, natural hazard resilience, and multilateral planning. Josh is a graduate of Hampshire College.

SARAH SLAY / Editor

Sarah is a first-year dual master’s student with the UNC MCRP and Duke Master’s of Environmental Management. Her research interests include freshwater resource management and land use changes in urban environments. She’s thrilled to contribute to the 50th anniversary edition and hopes that CPJ will inspire planners for another 50 years.

JOSEPH WOMBLE / Editor & Writer

Joseph is a first-year student in the Master’s of City and Regional Planning program at UNC Chapel Hill. His studies focus on transportation systems and their intersections with housing and broader land use. Previously, he provided technical assistance to local governments seeking to advance clean energy and clean transportation goals.

DESIGNING LIVING THINGS

Human Relationships with Nature

CANDELA CERPA (SHE/HER/ELLA)

Candela is a third-year dual master’s student in City and Regional Planning at UNC Chapel Hill and Environmental Management at Duke University. She is interested in equitable natural hazards planning and urbanism in the Global South. Born and raised in Uruguay, she received her B.S. in Environmental Science and Policy from the University of Maryland, College Park. Outside of work and school, she enjoys learning new recipes, listening to audiobooks, and fostering cats.

DR. RENATA POULTON KAMAKURA (THEY/THEM)

Renata is a 2024-25 National Academy of Sciences Science Policy Fellow at the Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ocean Observing System. They completed their Ph.D. in Ecology at Duke University in 2024 studying urban forest health and structure in Chicago, IL and Durham, NC. Their current work focuses on the impacts of marine heatwaves on coastal ecosystems, communities, and industries in the northern Gulf of Mexico region. Their hobbies include running, trying to learn how to watercolor, and exploring small museums or exhibits in local neighborhoods and libraries.

ABSTRACT

Cities house over half of the global human population and are home to a diversity of nonhuman species. In the ongoing climate crisis, there is increasing interest in ensuring urban areas are designed to survive increasing climate extremes while supporting conservation goals and limiting resource use. This urban resilience depends on our ability to plan for, and with, an increasingly volatile climate, historically degraded ecosystems, and non-human species surviving in increasingly fragmented habitats. Nature-based solutions (NbS) and Green/Blue infrastructure (GBI) are two examples of approaches that incorporate non-human entities as part of urban planning for more sustainable cities. However, these frameworks generally focus on the usefulness of and ability to control and shape non-humans for human needs. Human needs are important; however, this approach does not account for the challenges and opportunities that come from the agency of non-humans, like tree root network expansion, human-wildlife interactions, and changes in river courses. This paper investigates how NbS and GBI support (or not) the needs and interests of non-humans alongside humans. Then it describes some frameworks for how non-human needs and agency can be understood and incorporated into urban planning/design projects using both theoretical frameworks and practical case studies. The case studies highlight the opportunity to learn from a mix of Western and non-Western approaches both in the Global South (Barranquilla, Colombia) and Global North (O’ahu, Hawai’i). In doing so, we provide ideas for how, in designing more resilient cities, we can treat non-humans as active participants in healthy, thriving, urban communities.

INTRODUCTION

Cities are often seen as human realms, designed with humans primarily in mind. Yet a walk around a city quickly shows that they are home to more than just humans. Be it an ibis in Victoria, Australia, burrowing through trash in search of food, a troop of macaques in Shimla, India, stealing food at tourist sites, or mature oak trees pulling up sidewalks in Houston, U.S., nonhuman species are constantly interacting with humanbuilt infrastructure. Like people, non-humans seldom do what planners expect: they have agency. Ignoring non-human agency risks not just the consequences of unplanned interactions, like in the examples above, but also overlooks the potential benefits humans and nonhumans can derive from our cohabitation. To facilitate more beneficial and less tense interactions, our planning practices should account for both human and non-human agency in city design.

The literature on human-non-human relationships, especially in the context of conservation, has highlighted the challenge of non-human agency and its consequences for decades (Nyhus 2016; Soulsbury and White 2014). Beyond basic city functionality, our ability to coexist with non-humans is critical for human health and wellbeing (Elton 2021; Kirk, Pemberton, and Quick 2019; Soulsbury and White 2014; ‘Āina of Ka ‘ōnohi et al. 2023) as well as biodiversity conservation and ecosystem health (‘Āina of Ka ‘ōnohi et al. 2023; Nyhus 2016; Pineda-Pinto, Frantzeskaki, and Nygaard 2022). Simultaneously, humannon-human relationships can come with tensions, including inconveniences (like wildlife-caused littering), injustices (like inaccessible sidewalks due to root growth), and even death (like mountain lion attacks). These realities call for plans that are not naively optimistic about humannon-human interactions but recognize their importance all the same.

In response to the challenges of human-non-human interactions, some frameworks argue humans and nonhumans should be largely separated. For example, Wilson’s Half Earth theory (2016) argues that humans should be concentrated in cities to allow for large national parks and wildlife reserves that are ceded entirely to non-humans. More broadly, the term “nature” is sometimes used to

reference that which is separate from human influence, something “pristine” that humans would “ruin” (Nash 2014, Turner 2011, 27-8). Large areas with regulated human access do provide vital ecosystem services, including necessary habitat for some non-human species (Pfeifer et al. 2017, Gray et al. 2016). However, there is growing recognition that nature does (and should) exist in cities too.

In light of this shift, urban planning has increasingly recognized the importance of building with and alongside regional ecosystems (Frantzeskaki 2019; Pineda-Pinto, Frantzeskaki, and Nygaard 2022). Concepts like Naturebased Solutions (NbS) and Blue-Green Infrastructure (BGI) encourage incorporating nature/non-humans into urban systems to improve sustainability, cost-savings, and human health (Pineda-Pinto, Frantzeskaki, and Nygaard 2022; Ribbe et al. 2024; An et al. 2024). As we face climate and biodiversity crises, these approaches can play a key role in pushing for more sustainable and resilient cities.

In this article, we review NbS and BGI definitions to explore how non-humans’ agency and needs are or are not considered in these frameworks and more broadly in urban planning. Then, we look at two case studies, one in the Global North and one in the Global South, where human-non-human relationships have been incorporated into urban NbS/BGI projects. We thus hope to examine how common concepts like NbS and BGI can be strengthened by recognizing the need to foster human-non-human relationships and, in doing so, plan for non-human, as well as human, needs and agency.

NbS AND BGI: NON-HUMANS IN URBAN PLANNING

Since at least the late nineteenth century with the Garden City movement, urban planning in the Global North has sought to incorporate non-humans into city design to improve sustainability, cost-savings, and human health outcomes (Howard 2006). Two contemporary examples are NbS and BGI. NbS are interventions that seek to “protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and artificial ecosystems” to address human social challenges and benefit humans and non-humans, such

as habitat protection and ecosystem restoration (Ribbe et al. 2024). BGI are combined networks of natural and designed landscape components that link hydrological functions (“blue infrastructure”) with vegetation systems (“green infrastructure”) to provide socioeconomic benefits, like retention ponds and rain gardens (Ribbe et al. 2024).

The literature on NbS and BGI has recently expanded to include discussions on justice and community codesign. In a review of urban NbS projects in Europe, for example, Frantzeskaki emphasizes how projects should be interdisciplinary, inclusive of diverse ways of knowing and perspectives, and responsive to residents’ needs (2019). Even neoliberal organizations, like the World Economic Forum (WEF), have begun proposing ideas that call for partnerships across local governments, the private sector, and civil society and emphasize the need to tackle inequality through NbS projects. The WEF’s “Nature-Positive Cities” report, for example, highlights both the need for partnership with businesses to adequately “catalyze investments” and stories of policymakers learning how to build resilient and livable cities directly from residents (An et al. 2024).

Despite the growing recognition that incorporating nonhuman elements into cities is important and requires attentiveness to justice, there is less clarity on how those calls for justice translate into human-non-human relationships. “BiodiverCities,” another WEF project, emphasizes that cities should “live in harmony with nature by 2030,” and has a call to “put nature first,” with NbS as the backbone (Khatri et al. 2022). Within a neoliberal, capitalist framework of “optimizing” and “maximizing” value, there is a recognition that humans have to live with nature, but human needs remain the metrics for success. In Frantzeskaki’s review, the need to control and manage the “green infrastructure” is clear starting from the first “lessons learned,” where they describe how designing projects to appear aesthetically pleasing and “natural” heavily influences their success (Frantzeskaki 2019). What it means to appear natural, and the irony of having to design non-humans to create that image, is not examined. This approach is not unique to this review, but was instead integral to, for example, the design work of Frederick Law Olmsted in projects like Central Park in New York City (Godoy 2023; McClelland 1993) and is ultimately the core method through which NbS and BGI are meant to improve human-centric outcomes (Ribbe et al. 2024). In a review of 121 NbS papers, Pineda-Pinto and colleagues

found that NbS approaches are primarily framed from a human-focused perspective, focusing on nature in terms of the services it provides to humans (2022).

BUILDING BRIDGES BETWEEN HUMANS AND NON-HUMANS

To build resilient relationships between humans and nonhumans, we must learn how to listen to non-humans and integrate their agency into decision-making and planning. Pineda-Pinto and colleagues argue for “ecological justice” an approach that develops relationships between ecosystems and humans that are resilient, rather than shaping ecosystems to provide for human resilience (2022). Their approach relies partly on science (especially ecological science) as a means to increase people’s awareness of their relationships with non-humans. They also detail various mechanisms of incorporating the agency of non-humans into planning, from participatory planning methods that include discussion of non-human needs and capabilities to identifying principles for human-nonhuman relationships (Pineda-Pinto et al., 2022). Sheikh and colleagues propose that digital technologies can integrate communication from non-human beings into smart urban governance (2021). They caution that it is not enough to monitor non-humans’ numbers and movement; we must learn how non-humans communicate and how they navigate urban landscapes (Sheikh et al. 2021). This includes finding and facilitating vital relationships between non-humans, like tree-fungi relationships, and learning how to balance human and non-human needs, like designing glass buildings to provide humans with natural light while reducing bird collisions. Taking it a step further, they highlight numerous examples drawn from Indigenous political systems that recognize non-human agency in governing lands and waters. For example, oral traditions within the Tlingit and Tagish First Nations convey the agency and role of glaciers in water governance while maintaining human knowledge of and respect for the glaciers. Perhaps most critically, they argue that

“a truly ‘smart’ urban governance should embrace the fact that humans, technology, and our political institutions do not have all the answers” (Sheikh et al. 2021).

As such, we need to shift away from a framework of complete understanding and control to one of relationshipbuilding and co-management.

RELATIONSHIP-BUILDING AS PLANNING IN PRACTICE

In this section, we present two cities exploring urban human-non-human relationships, one in the Global South and one in the Global North. The first community, Barranquilla, Colombia, presents a traditional example of an NbS/GBI project but shows how human residents are shifting their relationship to non-human life and ecosystem elements even under a neoliberal doctrine. The second community in O’ahu, Hawai’i, presents an Indigenous, non-Western approach to urban humannon-human relationships in the Global North.

BRINGING GREEN BACK: LESSONS FROM BARRANQUILLA, COLOMBIA

The Colombian city of Barranquilla is home to 1.2 million people (Swan 2023). In the past decade, the coastal city has been “shedding much of its industrialized past and seeking sustainable growth” (Swan 2023). In particular, the program “Todos Al Parque” has been making strides in increasing the space that vegetation, water, and wildlife have throughout the city. Beginning in 2011, Todos Al Parque has worked to restore blue-green spaces; so far, over sixteen million square feet of green spaces have been restored and designated as 300 urban parks (Alcaldía de Barranquilla 2024, Maassen 2022). This includes two BGI initiatives: Cíenaga de Mallorquín Park, with paths and bike lanes by wetlands and mangroves, and the Gran Malecón Riverwalk, with a 3.1-mile riverwalk by Colombia’s largest river, the Magdalena (Breathe Life 2022).

Todos Al Parque was created with community engagement, biodiversity protection, and social and spatial equity at its core. The initiative initially aimed to recover sixty parks for those who needed

it the most, which the city defined as young children, women, disabled people, and elderly residents in “a leading example of NbS” (Alcaldía de Barranquilla 2023a, Maassen 2022). The community gave recommendations, like the soccer pitch’s surface material, the size of playgrounds, and the inclusion of space for children’s programming. A symbolic signing ceremony, where residents “approved” the definitive version, was held before construction began at each park (Maassen 2022).

Todos Al Parque also created spaces where non-humans are the sole users, including four urban forests with 39.5 acres exclusively designated to grow 15,714 trees (Alcaldía de Barranquilla 2023b). Some of the twelve tree species planted include bonga (Ceiba pentandra), lluvia de oro (Laburnum anagyroides), ceiba blanca (Hura crepitans), caucho morado (Ficus elastica), alistonias (Alstonia scholaris), and mangle plateado (Conocarpus erectus; Alcaldía de Barranquilla 2023b). Cíenaga de Mallorquín Park recorded fifteen species of marine invertebrates, nine fish and amphibian species, seven reptile species, eighty-one bird species, and four mangrove trees (Alcaldía de Barranquilla 2023b). Ecological restoration efforts and social initiatives are likely to bring more species back to Barranquilla or create new habitats.

The reports focus on the human benefits of the NbS projects. For example, residents saw improved healthcare through pop-up vaccination sites, higher rates of recreation and socialization through sports programs, increased economic diversity through markets, and more (Breathe Life 2022). There are some brief mentions of improved water quality and the presence of vegetation and local and migratory birds, mainly from the perspective of birdwatching and the ecotourism they bring (Alcaldía de Barranquilla 2024). In 2023, for example, the City reported that more than ten million people visited the Gran Malecón Park for sport and recreation (Swan 2023). However, some of the quotes included in the articles offer insight into how these benefits are tied to residents’ views of the growing presence of nonhumans in the city.

Before the program, residents had an extremely negative perception of blue and green urban spaces, associating them with “drug dealing, crime, and neglect” (Maassen 2022) as well as pollution from decades of industrial development (Swan 2023). After the redevelopment, residents are expressing far more positive views. Barranquilla’s mayor from 2020 to 2023, Jaime Pumarejo, reflected that

“the [Magdalena] river is us. We exist because of it, but we forgot about it and turned away from it” (Swan 2023).

This quote is directly about a human-non-human relationship, seeing how ecological degradation can reflect worsening human conditions. About a lawsuit he filed against the federal government in 2022, alleging it was not doing enough to protect the river from pollution, Pumarejo said that “if we clean up the river, we’re cleaning up the country, bettering people’s quality of life and finding a place where we can unite” (Swan 2023). To heal that relationship, there are calls to “get people back to the river because it had become an industrial zone and we wanted to make them touch the river again, see it, feel it” (Swan 2023).

With the projects, there has also been a significant shift in the literal space that non-humans now use in Barranquilla. Today, 93 percent of households live within an eight-minute walk to a green, public space (Breathe Life 2022). This approach not only benefits more people while decreasing the need for transportation to those green spaces, but it also places urban nature as a neighbor rather than a faraway destination.

URBAN ‘ĀINA IN O’AHU, HAWAI’I: CITIES AS SOURCES OF SACRED RELATIONSHIPS

‘Āina of Ka ‘ōnohi and colleagues offer urban ‘Āina in O’ahu in Hawai’i as an example of urban landscape engagement that emphasizes human-non-human relationships by drawing on Native Hawaiian practice and knowledge (2023). ‘Āina, a foundational Hawaiian concept, encompasses physical, psychological, and spiritual dimensions that describe relationships between people, homelands, identity, god/goddess, and family. In this framework, “humans are kin to all that is the universe.” Urban ‘Āina then, despite the colonial realities of urban landscapes in Hawai’i, defines urban areas as a “source of sacred relationships among humans, land, water, sky, and ancestors” (‘Āina of Ka ‘ōnohi et al. 2023). The paper and the case studies (offerings) presented are an opportunity to (re)create relationships in urban Hawai’i. Cities are not described as human-centered but, instead, a shared space of kinship.

We here focus on one of their case studies, a restoration at the edge of a residential area in the Wai’anae mountain range. Following expert guidance, stewards from the Mālama Learning Center initially planted trees ten feet apart with shrubs between the trees and ground cover throughout at the Pālehua dryland forest restoration site (‘Āina of Ka ‘ōnohi et al. 2023). This approach aims to reduce competition and thus allow the trees to grow. Instead, stewards found high rates of tree mortality and low plant health. In response, they tried a different approach. In “community-style” planting, native species are planted in high density in a newly cleared area, a more energy-intensive approach that is restricted to a smaller area. However, by listening to what the plants were telling them and changing their planting practices, they found that the plant communities flourished, facilitating each other’s growth (‘Āina of Ka ‘ōnohi et al. 2023; Mālama Learning Center 2024). In line with Mālama Learning Center goals, the crews who listened and learned from the plants were primarily nearby residents and students. The Center aims to support local communities in “understand[ing] the significance of the resources of this area [...] and feel a sense of belonging as well as kuleana [responsibility, privilege] to care for their home” (‘Āina of Ka ‘ōnohi et al. 2023; Mālama Learning

Center 2024). This case exemplifies how urban greening initiatives can build relationships with both human and non-human kin and foster a practice of listening to what non-humans (in this case, plants) are telling us. More broadly, urban greening projects that include residents in the process and encourage them to look for signs of stress or thriving in nearby plant (or other non-human) life can serve as both an opportunity for relationship-building and as a monitoring and alert system to encourage adjustments in management approaches. It requires both the opportunity for residents to engage in the project work and an openness from project managers to try alternative approaches that might better suit the local project context (e.g. “community-style” planting).

Both this project and the other offerings in the paper talk about relationship building as essential to the health of both human and non-human communities. Human benefits of the urban ‘Āina projects include food access and

the preservation of traditional foodways, spiritual and cultural reconnection with ‘Āina, and various ecosystem services vital to human health and well-being. Some of the projects emphasize the agency of non-humans more than others. However, all provide concrete examples of how to rehabilitate human-non-human relationships and how that supports human community well-being.

Drawn from Native Hawaiian theory and practice, the Urban ‘Āina case studies are deeply place-based (or, more accurately, ‘āina-based) and built from the knowledge and traditions of communities with longstanding relationships to the non-humans in O’ahu. Even the structure of the paper emphasizes the importance of relationships, opening and closing with ceremony.

While applying a specifically Native Hawaiian approach to other contexts would not be appropriate, these offerings highlight that there is a diversity of nonWestern practices, traditions, and ways of knowing that

guide how to rehabilitate human-non-human relationships, even within the settler colonial context of the United States. For urban NbS or BGI, a more pluralistic approach that recognizes the power of local knowledge and traditions would require planners to cede some power to local communities (particularly Indigenous communities) that have long-standing relationships to place. Collaborative projects can draw from both Western understandings of technology and engineering and place-based (often non-Western) understandings of ecology, history, and relationships. Such a pluralistic approach can use a variety of tools and practices to first understand/see/hear and then account for the needs and agency of non-humans.

CONCLUSION: CITIES OF THE FUTURE

If trends continue, future cities will incorporate nature (whether through NbS or GBI) into their design. How this is done, and whether non-human as well as human needs and agency are considered, is yet to be seen. This piece considers some of the ongoing discussions about how urban planning can create spaces where humans and nonhumans can coexist and, ideally, build generative and healthy relationships. NbS and GBI provide opportunities to bring non-humans more fully into urban spaces, though they often imply the need to control non-humans to do so. Frameworks related to ecological justice push planners to move beyond controlling non-humans for human needs and instead plan for the needs and interests of both humans and non-humans. Digital technologies can provide some tools that facilitate our ability to listen to and adjust for non-human needs, but technology alone cannot replace the need for healthy human-non-human relationships. Our case studies highlight that, both within the Global South and Global North there are both Western and non-Western approaches, traditions, tools, and knowledge that can foster human-non-human relationships and inform planning approaches. Because of our limited scope, we only focus on two theoretical approaches and two case studies. We offer this paper as part of the conversation on how to consider human-nonhuman relationships in urban planning, especially in the context of NbS and GBI. We hope readers are encouraged to explore local possibilities alongside their human and non-human neighbors.

WORKS CITED

‘Āina of Ka‘ōnohi, Anthony K. Deluze, Kamuela Enos, Kialoa Mossman, Indrajit Gunasekera, Danielle Espiritu, Chelsey Jay, et al. 2023. “Urban ʻĀina: An Indigenous, Biocultural Pathway to Transforming Urban Spaces.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 15 (13). https://doi.org/10.3390/ su15139937

Alcaldía de Barranquilla. “El modelo de gobernanza para la sostenibilidad que Barranquilla destacó en la COP16.” October 29, 2024. Accessed January 1, 2025. https:// www.barranquilla.gov.co/mi-barranquilla/modelo-degobernanza-sostenibilidad-cop16

Alcaldía de Barranquilla. “Barranquilla, ejemplo latinoamericano en soluciones basadas en la naturaleza.” July 28, 2023a. Accessed January 1, 2025. https://www. barranquilla.gov.co/mi-barranquilla/barranquillaejemplo-latinoamericano-en-soluciones-basadas-enla-naturaleza

Alcaldía de Barranquilla. “Barranquilla, una ciudad verde que no para de crecer.” December 11, 2023b. Accessed February 16, 2025. https://www.barranquilla.gov.co/ mi-barranquilla/barranquilla-una-ciudad-verde-queno-para-de-crecer

An, Esther, London Breed, Arjun Dhawan, Nollaig Forrest, Yoo Jeong-Bok, Cha-ly Koh, Marie Lam-Frendo, et al. 2024. “Nature Positive: Leaders’ Insights for the Transition in Cities.” https://www.weforum.org/publications/naturepositive-leaders-insights-for-the-transition-in-cities/

Breathe Life. “Barranquilla’s Thriving Green and Blue spaces: Successes in Urban Planning.” September 12, 2022. Accessed January 1, 2025. https://breathelife2030. org/news/barranquillas-thriving-green-blue-spaces/ Elton, Sarah. 2021. “Relational Health: Theorizing Plants as Health-Supporting Actors.” Social Science and Medicine 281: 114083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114083

Frantzeskaki, Niki. 2019. “Seven Lessons for Planning Nature-Based Solutions in Cities.” Environmental Science and Policy 93: 101–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envsci.2018.12.033

Godoy, Eric S. 2023. “Every Tree Fixed with a Purpose: Contesting Value in Olmsted’s Parks.” Environmental Values 33 (5): 511–28. https://doi. org/10.1177/09632719231220425

Gray, Claudia L, Samantha L L Hill, Tim Newbold, Lawrence N Hudson, Luca Börger, Sara Contu, Andrew J Hoskins, Simon Ferrier, Andy Purvis, and Jörn P W Scharlemann. 2016. “Local Biodiversity Is Higher inside than Outside Terrestrial Protected Areas Worldwide.” Nature Communications 7 (1): 12306. https://doi. org/10.1038/ncomms12306

Howard, Ebenezer. Garden Cities of To-Morrow, ed. F.J. Osborn. London: Routledge, 2006. https://doi. org/10.4324/9780203716779

Khatri, Akanksha, DIego Bustamante, Marina Ruta, Cristina Gómez Garcia-Reyes, Fraser Thompson, Shivin Kohli, Heleni Pantelidou, Matthew Free, Giacomo Magnani, and Stephanie Schemel. 2022. “BiodiverCities by 2030: Transforming Cities’ Relationship with Nature.”

Kirk, Robert G W, Neil Pemberton, and Tom Quick. 2019. “Being Well Together? Promoting Health and WellBeing through More than Human Collaboration and Companionship.” Medical Humanities 45 (1): 75. https:// doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2018-011601

Maassen, Anne. “In Barranquilla, Colombia, Urban Parks Revitalize a Declining City.” World Resource Institute. December 7, 2022. Accessed January 1, 2025. https://www. wri.org/insights/barranquilla-colombia-urban-parksrevitalize-declining-city

Mālama Learning Center. 2024. “Palehua Erosion Control and Restoration.” 2024. https://www. malamalearningcenter.org/p257lehua-erosion-control-restoration.html

McClelland, Linda Flint. Presenting Nature: The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916 to 1942. United States: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Cultural Resources, Interagency Resources Division, National Register of Historic Places, 1993.

Nash, Roderick. Wilderness and the American Mind: Fifth Edition. United Kingdom: Yale University Press, 2014.

Nyhus, Philip J. 2016. “Human–Wildlife Conflict and Coexistence.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 41 (Volume 41, 2016): 143–71. https://doi. org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085634

Pfeifer, M, V Lefebvre, C A Peres, C Banks-Leite, O R Wearn, C J Marsh, S H M Butchart, et al. 2017. “Creation of Forest Edges Has a Global Impact on Forest Vertebrates.” Nature 551 (7679): 187–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nature24457

Pineda-Pinto, Melissa, Niki Frantzeskaki, and Christian A. Nygaard. “The Potential of Nature-Based Solutions to Deliver Ecologically Just Cities: Lessons for Research and Urban Planning from a Systematic Literature Review.” Ambio 51, no. 1 (April 16, 2021): 167–82. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01553-7

Ribbe, Lars, Greta Dekker, and Gaurav Thapak. 2024. “Chapter 6 - Urban Wetlands and Water Bodies.” In Managing Urban Rivers, edited by Victor R Shinde, Rajiv Ranjan Mishra, Uday Bhonde, and Hitesh Vaidya, 91–107. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-32385703-1.00007-9

Sheikh, Hira, Peta Mitchell, and Marcus Foth. 2023. “More-than-Human Smart Urban Governance: A Research Agenda.” Digital Geography and Society 4: 100045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diggeo.2022.100045

Soulsbury, Carl D, and Piran C L White. 2016. “Human–Wildlife Interactions in Urban Areas: A Review of Conflicts, Benefits and Opportunities.” Wildlife Research 42 (7): 541–53. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR14229

Swan, Esan. “Barranquilla shakes off industrial past in bid to protect biodiversity.” Financial Times. May 16, 2023. Accessed January 1, 2025. https://www-ft-com. ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/content/a745faac-5c1d-44e1ab43-a69119151ad3

Turner, Matthew D. 2011. “Production of Environmental Knowledge - Introduction.” In Knowing Nature: Conversations at the Intersection of Political Ecology and Science Studies, edited by Mara J. Goldman, Paul Nadasdy, and Matthew D. Turner, 25–31. United Kingdom: University of Chicago Press.

Wilson, Edward O.. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. United States: Liveright, 2016

REIMAGINING PAPER STREETS IN DURHAM

Unlocking Urban Potential Through Collaboration and Community Engagement

ANDREW HOLLAND

Andrew Holland serves as Assistant Director for the Budget and Management Services Department and Director of Performance and Innovation with the City of Durham. He leads the Office of Performance and Innovation, which includes the City’s Innovation Team (I Team), Strategy and Performance, Participatory Budgeting, and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) program. He and his team focus on improving outcomes by working collaboratively with staff, residents, local businesses, and partner organizations. Previously, Andrew served as Assistant to the County Manager in Mecklenburg County, where he led the Enterprise Risk Management and Compliance program. He also worked as Assistant to the City Manager in Fayetteville, a Business Analyst in Durham’s Fleet Management Department, and as an Environmental Protection Specialist with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Washington, D.C. Andrew holds a Master of Public Administration from North Carolina Central University and a Bachelor of Science in Urban and Regional Planning from East Carolina University. He is currently pursuing a Doctor of Design at North Carolina State University’s College of Design. His research explores the use of immersive tools to support participatory design processes, particularly in reimagining paper streets as vibrant, community-centered public spaces.

LYNDSAY GAVIN

Lyndsay manages the City of Durham I-Team, where she works to bridge the gap between research and public services. Previously, she was a senior behavioral scientist at the Center for Advanced Hindsight, where she used applied research to bring behavioral insights to public policy. Lyndsay previously studied the health impacts of climate change for the California EPA Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment and worked as an Environmental Engineer for an oil company before discovering a passion for local government, à la Leslie Knope. She holds an MPH from Yale and a BS in Biological Engineering from the University of Wisconsin. hobbies include running, trying to learn how to watercolor, and exploring small museums or exhibits in local neighborhoods and libraries.

ERICK PEÑA

Erick Peña is a local government employee and proud Durham native. He has a Bachelor’s in Communications from UNC Charlotte and a Master’s in Public Administration from Villanova University. Erick’s work is focused on improving resident-municipal interactions and outcomes through human centered design and user experience.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Melissa Amoabeng

INTRODUCTION

Paper streets are roads that were planned but never built. These unused spaces could potentially help solve important problems in cities. These neglected areas often contribute to issues such as littering, illegal dumping, and the lack of accessible green spaces. However, they also offer opportunities for diverse uses, including recreational spaces, ecological restoration, walkable pathways, and even affordable housing. As city planners and officials increasingly seek innovative solutions for neglected land, Durham’s approach emphasizing communityled design and sustainable development serves as a framework for transforming these spaces into community assets, especially for marginalized neighborhoods that have experienced disinvestment. This article explores Durham’s efforts to reimagine paper streets through interdepartmental collaboration, community engagement, and design innovation. It also outlines the challenges, potential use cases, and potential policy implications tied to the inclusive transformation of these neglected urban spaces.

In 2023, to better understand the scale and complexity of the issues tied to paper streets, the Durham’s Innovation Team (I-Team) initiated a collaboration with the Code Enforcement team to learn how these spaces impact their daily operations. These discussions helped clarify the physical and geographic nature of paper streets and the illegal activities that frequently occur there, including littering and illegal dumping. Based on these conversations, the I-Team recognized that enforcement alone may not be a sustainable solution. However, there is potential to deter such activity through thoughtful interventions. One promising approach is to reimagine, repurpose, and redesign select paper streets in ways that reflect community needs and values - transforming them into safe, usable spaces that discourage misuse and strengthen neighborhood identity.

“Paper streets” are designated on city maps but remain undeveloped, leading to their frequent misuse for littering, dumping, loitering, and the presence of invasive vegetation. Such activities place a significant strain on the City’s Code Enforcement and Impact Team, as these areas fall outside the city’s maintenance obligations.

Paper streets often lack official ownership which creates legal ambiguity and complexity, making conversion efforts costly and time-consuming. Consequently, many governments view these areas as challenges not worth addressing.

Despite these hurdles, paper streets hold untapped potential. Some serve practical purposes such as informal walkways or community cut-throughs. Durham alone has over 600 paper streets with approximately 600 located within city limits, amounting to over 200 acres of unused space. This amount of acreage is equivalent to thirty times the size of Durham Central Park.

Recognizing this potential, the I-Team partnered with other city departments to implement innovative strategies to shift perspectives on paper streets. The work focuses on transforming these neglected spaces into valuable community assets, fostering equitable development and revitalization in underserved neighborhoods. Through initiatives like the Love Your Block grant and community cleanups, Durham is pioneering a model for how cities can reimagine and repurpose underutilized urban spaces for the greater good.

LITERATURE REVIEW

To better understand the intricacies of paper streets, the I-Team reviewed existing literature about paper streets. The research centered around how local municipalities have approached paper streets, both in terms of the legal ramifications and creative applications of the spaces. Currently, there is little literature on the state of paper streets in North Carolina. The North Carolina state legal code provides a definition of paper streets but offers little guidance on how to deal with them (N.C. Gen. Stat. § 136-96. 2001). North Carolina law firms have documented how to apply the state statute, both through private and governmental closings, but there are few publicly available examples of closures (Bennington 2001).

Many documented instances of city intervention in paper streets arise from legal disputes and complaints from residents. The ambiguous legal definition of paper streets often leads to confusion and debate over responsibility

for the spaces, particularly among property owners whose lots abut them (Simms 2022). Issues surrounding paper streets vary in severity and scope, sometimes involving entire neighborhoods, city councils, and developers (Shorey 2020; Bouchard 2017). Legal implications remain unresolved due to the lack of solid precedents, creating challenges for residents and developers alike.

Most city interventions involve vacating the disputed area, allowing adjoining property owners to absorb the land (Bellano 2016). Some cities have abandoned undeveloped portions of streets and added them to adjacent nature preserves, while others have repurposed them for pedestrian and bicycle pathways (Brashares et al. 2015; City of Falls

Church n.d.). Although some cities have transformed unaccepted or undeveloped streets into street parks or general green spaces, research suggests these instances are rare.

PROJECT GOAL AND EXECUTION

To effectively address the challenges and opportunities presented by paper streets, the I-Team recognized the need to collaborate with experts who had deeper knowledge and experience in this area. Understanding that these spaces intersect multiple city functions, the I-Team conducted a series of interviews with internal departments, including the General Services Real Estate

Division, the City Attorney’s office, Neighborhood Improvement Services, Planning, Parks and Rec, and Transportation, to assess the complexities.

Through these discussions, it became evident that paper streets were far more intricate than initially anticipated. Legal ambiguities, maintenance responsibilities, zoning regulations, and infrastructure constraints all contributed to the complexity of repurposing these spaces. Given the multi-faceted nature of the issue, the I-Team established a Core Team to systematically address the challenges.

The Core Team consisted of representatives from the General Services-Real Estate Division, Parks and Recreation, and Transportation, while the City Attorney’s Office, Neighborhood Improvement Services, Public Works, and Planning served as auxiliary members providing specialized support. This cross-departmental collaboration was essential to navigating the regulatory, legal, and logistical barriers associated with paper streets.

A critical first step in the process was identifying and cataloging all paper streets within Durham. With assistance from Public Works, the team retrieved a Geographic Information System (GIS) layer that mapped out paper streets within city limits. The findings were striking-- over 600 paper streets were identified, covering more than 200 acres of unused land.

Beyond mapping their locations, the team recognized the importance of understanding the characteristics and attributes of each paper street to determine their best potential uses. Utilizing GIS analysis, they assessed key factors such as:

• Length and width of each paper street

• Topography and terrain

• Zoning classifications and land-use restrictions

• Proximity to bus shelters and transit routes

• Floodplain status and environmental constraints

This data-driven approach brought the paper streets to life, transforming them from abstract spaces on a map into tangible opportunities for urban revitalization. By

analyzing these attributes, the team gained valuable insights into how different sites could be repurposed— whether for green spaces, pedestrian pathways, or community-focused projects.

While this foundational research provided critical information, the team also recognized the need to integrate design into the process to visualize the potential of these spaces more effectively. To achieve this, the I-Team reached out to the North Carolina (NC) State University College of Design’s Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning program for their expertise in landscape design, planning and environmental management. Moreover, their involvement helped translate raw data into actionable design concepts, allowing the city to explore how paper streets could be reimagined as vibrant, functional community assets. This collaborative approach combining data analysis, cross-departmental coordination, and design innovation laid the groundwork for developing creative, communitycentered solutions for Durham’s underutilized paper streets.

EXPLORING THE URBAN POTENTIAL OF PAPER STREETS

To further explore the urban potential of paper streets, the I-Team partnered with NC State Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning program. Led by Professors Carla Delcambre and Andy Fox in Fall 2023, the studio challenged students to develop proposals for three selected sites in Durham, integrating sustainable design with ecological considerations.

As part of this initiative, professors and students conducted site visits to paper streets in downtown Durham, bringing a level of design and environmental expertise to assess these vacant lots. Their evaluation went beyond just the physical characteristics of the sites; they also considered the topography, historical significance of surrounding areas, and environmental conditions. This comprehensive approach allowed them to develop strategies that honored the cultural and ecological context of each space while ensuring that redevelopment efforts met the needs of Durham

residents. It should be noted that these student proposals were conceptual and exploratory in nature and did not go through the City of Durham’s formal development review process.

In addition to assessing the feasibility of redesigning these spaces, students explored ways to enhance urban resilience and mitigate environmental impacts. Although these paper streets were located in highdensity urban areas, students identified opportunities to introduce native plants and vegetation to provide much-needed greenery and combat the urban heat island effect, an issue that often accompanies rapid urban growth. Their proposals emphasized how landscape interventions could improve environmental sustainability while also creating functional and aesthetically pleasing spaces for the community.

would be necessary to move from concept to pilot. These conversations deepened mutual understanding between emerging designers and city officials and helped ground the design process in both creativity and practicality.

At the conclusion of the semester, students had the opportunity to present their designs in a final critique session attended by city staff, College of Design professors, and design professionals from the Triangle. This critique provided valuable feedback, allowing students to refine their proposals based on practical considerations and real-world implementation challenges. The discussion prompted important questions around zoning limitations, long-term maintenance responsibilities, community ownership models, and how to balance ecological restoration with safety and usability. City leaders and designers also engaged in thoughtful conversations about how these ideas might scale and what types of partnerships

PAPER STREETS AS A POTENTIAL OPTION FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Building on the earlier design collaborations with NC State, the I-Team also explored how paper streets might conceptually support other pressing needs in Durham, with a particular focus on the city’s ongoing housing challenges. It is important to clarify that the City of Durham does not currently have formal plans to convert paper streets into parcels for affordable housing. Instead, the I-Team’s objective was to explore paper streets as theoretical sites, examining how these constrained

landscapes could inform design thinking related to transitional housing, urban resilience, and community well-being.

In 2019, Durham passed a $95 million affordable housing bond, prompting the I-Team to explore how underutilized paper streets could contribute to housing solutions, particularly for the unhoused population. Given the legal and spatial complexities of paper streets, the team sought innovative ways to integrate housing, green infrastructure, and community well-being into the redesign process.

Building on the earlier work, the I-Team collaborated with NC State’s Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning program on a second design studio, led by Professors Carla Delcambre and Dong-Jae Yi. This studio focused on identifying paper streets on the periphery of downtown Durham that could accommodate tiny homes, offering a practical and scalable approach to transitional housing. Over the course of the semester, students conducted site visits and worked closely with the Community Safety Department to ensure their designs were not only feasible but also aligned with the needs of Durham’s unhoused residents.

A critical component of these designs was the strategic use of native vegetation to enhance both the livability and therapeutic benefits of these spaces. Recognizing the importance of mental and emotional well-being, some students intentionally incorporated sensory-friendly plants known for their calming and restorative qualities. In addition to improving air quality and mitigating urban heat islands, the integration of greenery intended to create a healing environment for individuals experiencing housing insecurity or mental health challenges.

At the conclusion of the semester, students presented their paper street designs during a design critique attended by city staff, College of Design professors, and local design firms from the Triangle. Their proposals offered creative, human-centered solutions for transforming paper streets into housing opportunities for Durham’s most vulnerable populations. This critique

not only provided students with feedback from industry professionals but also allowed city officials to explore the feasibility of incorporating these ideas into Durham’s long-term affordable housing strategies.

FUNDING AND GRASSROOTS ENGAGEMENT

Expanding the paper streets initiative required more than just policy development and design expertise. It demanded direct involvement from the communities most affected by these underutilized spaces. Ensuring that residents had both a voice in decision-making and the resources to take action became a key priority. To build momentum and empower local leadership, the I-Team sought funding opportunities that would place revitalization efforts directly in the hands of community members.

The I-Team applied for the Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation’s Love Your Block grant; a program designed to enhance public spaces in economically distressed neighborhoods. The $100,000 grant is intended to provide funding to community members and organizations to transform abandoned spaces into community assets. These grants will enable residents to lead initiatives such as cleaning up vacant lots, creating green spaces, or developing recreational areas in underutilized paper streets. The remaining funds support a full-time project management fellow from the community, ensuring that local voices drive the initiative. The program’s first phase focuses on Durham’s Walltown neighborhood, where grassroots engagement will shape the reimagining of these spaces.

As part of these efforts, the I-Team engaged the community in a Martin Luther King Jr. Day litter cleanup in collaboration with Keep Durham Beautiful. Before the cleanup, volunteers received an overview of paper streets and the potential redesign efforts within Walltown. They learned about the significance of these underutilized spaces and how they could be transformed into green areas, pedestrian pathways, or community hubs. The cleanup also provided an opportunity for Walltown residents to participate in a survey about revitalization

efforts for vacant lots in their neighborhood. The survey gathered community perspectives on pressing needs, potential uses, and any concerns regarding redevelopment. This approach encouraged direct engagement, ensuring that residents played a pivotal role in shaping the future of these spaces.

As a two-year commitment, this initiative will require continued engagement and collaboration to ensure the long-term success of these revitalization efforts. Sustaining momentum will involve ongoing partnerships with residents, local organizations, and city departments, reinforcing a community-driven approach to transforming paper streets into vibrant, functional, and inclusive spaces across Durham.

THE BLOOMBERG HARVARD CITY LEADERSHIP INITIATIVE

Durham was selected to participate in the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, a collaboration between the Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard Business School, and Bloomberg Philanthropies. This initiative is designed to equip city officials with tools to address complex urban challenges through data-driven decision-making, innovative governance, and resident engagement.

As part of the Innovation Track, Durham’s cross-functional team is working to standardize definitions for paper streets, prototype innovative land-use solutions, and engage residents in shaping the future of these spaces. The initiative includes leadership training, policy development strategies, and access to a network of city leaders nationwide who are implementing similar projects. Durham officials are participating in workshops and research efforts that help refine approaches to neglected urban spaces, leveraging insights from other municipalities.

Through this initiative, Durham is exploring best practices in urban planning and design, sustainable land use, and community engagement. City officials are working to develop policies that not only clarify ownership and responsibility for paper streets but also create opportunities for long-term redevelopment. The goal is to create

a replicable framework that can be applied to other municipalities, ensuring that paper streets become valuable community assets rather than liabilities.

CONCLUSION

Durham is embarking on a bold initiative to reimagine paper streets and transform them into valuable community assets. This effort is not without its challenges, but with the commitment of city departments and the leadership of Mayor Leonardo Williams and city officials, Durham is demonstrating that innovative urban planning and equitable development are worth the investment. The city is leveraging cross-departmental collaboration, community engagement, and forward-thinking policies to address long-standing issues associated with paper streets.

Hoping to turn neglected spaces into integrated components of future land use, Durham is spotlighting the potential of paper streets in sustainable infrastructure, recreation, environmental resilience, and affordable housing. These spaces also present opportunities for ecological restoration and thoughtful design, incorporating native vegetation, improved stormwater management, and placemaking strategies that enhance connectivity and walkability.

The insights gained from this work will help shape longterm policies and urban strategies, ensuring that paper streets are no longer overlooked but instead recognized as key assets in creating more equitable, sustainable, and well-designed communities.

WORKS CITED

Bellano, A. 2016. “Paper street causes real life controversy in Moorestown.” Patch, November 30. https://patch.com/ new-jersey/moorestown/paper-street-causes-real-lifecontroversy-moorestown

Bennington, D. A. 2001. “Erasing the paper street.” Investors Title. https://www.invtitle.com/docs/articles/ nc/Erasing%20the%20Paper%20Street%202001.pdf

Bouchard, K. 2017. “Waterfront access dispute divides Cape Elizabeth enclave.” Portland Press Herald, October 2. https://www.pressherald.com/2017/10/02/waterfrontaccess-dispute-divides-cape-elizabeth-enclave/

Brashares, J., Weiner, J., Suresh, S., & Freeborn, N. 2015. Street Parks Manual, June. https://sfpublicworks.org/ sites/default/files/4970-SF%20Street%20Parks%20 Manual_Final.pdf

City of Falls Church. n.d. “Paper streets in the city of Falls Church.” The City of Falls Church Virginia. https://www.fallschurchva.gov/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/ Item/199?fileID=6235

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 136-96. 2001. https://www.ncleg.net/ enactedlegislation/statutes/html/bysection/chapter_136/ gs_136-96.html

Shorey, E. 2020. “Hines road residents shocked as ‘paper street’ gets asphalt.” The Valley Breeze, January 15. https:// www.valleybreeze.com/news/hines-road-residentsshocked-as-paper-street-gets-asphalt/article_b5a3cce81807-5138-9a2a-1f10a1b8626c.html

Simms, J. 2022. “Beacon’s paper streets.” The Highlands Current, February 18. https://highlandscurrent. org/2022/02/18/beacons-paper-streets/

THE COST OF A DEGREE

A comparative case study of urban universities in major mid-Atlantic cities and their impact on surrounding communities

SAMANTHA NIVEN

Samantha Niven is in their final term at the Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy in pursuit of their Master’s in City and Regional Planning with a concentration in Equitable and Resilient Community Development. They received a bachelor’s degree in Global Studies with a concentration in Global Health and Sustainability and minors in Spanish, Management Information Systems, and Business Administration from Drexel University. They are interested in communitycentered planning solutions, especially as they relate to Environmental Justice issues and communities.

ABSTRACT

Universities in the United States often rely on relationship-building when differentiating themselves from other universities competing for the same resources, but the relationship they often omit, which can cause complex and often overlooked impacts, is to the communities they abut. In this paper, we observe two universities located in two major mid-Atlantic cities: Drexel University, a private research university in Philadelphia, PA; and Rutgers University, a public university in New Brunswick, NJ. The social-ecological systems (SES) framework is applied to different past, recent, and future development at each university and analyzed based on their outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Universities have a deep history in the United States, for longer than the United States has been a country. Originating from modest, religious backgrounds, the average college student was white, wealthy and male, until the Morrill Land Grant College Act was passed in 1862 to include students interested in the agricultural and mechanical arts in the university population (United States Senate n.d.). As their offerings and student bodies continued to diversify, universities found the need to distinguish themselves from one another, finding success in marketing strategies similar to those employed by for-profit businesses. While university colors, mascots, and sports teams are tactics that have given universities a strong sense of identity, some of the flashiest marketing used have been the physical design of university campuses. This has led to several patterns arising, such as state-sponsored universities having sprawling campuses in rural areas, prestigious northeastern universities becoming associated with the beautiful ivy climbing up the walls of their academic buildings, and southern universities boasting large buildings reminiscent of their lavish, albeit morally abhorrent, pre-Civil War days.

Nowadays, universities across the country compete for every component of their institution: students, faculty, rankings, sports titles, funding, etc.. Acquiring and maintaining these different components has required intentional relationship-building between universities and stakeholders like alumni, local businesses, and state and municipal governments. While several strategies are implemented for relationship-building purposes, one way that many universities have found particular success has been through the intentional and often radical physical design of their campus. The one group that seems to be consistently omitted from the relationship-building process, and thus the design process, tends to be one of the most physically prominent populations: the existing local community that resided in the space long before the encroachment of the student population. In this study, two universities, Rutgers University and Drexel University, are observed, and prominent events in their histories determine the extent to which university development and design positively and/or negatively impact the surrounding environment, community, and its historic population.

METHODOLOGY

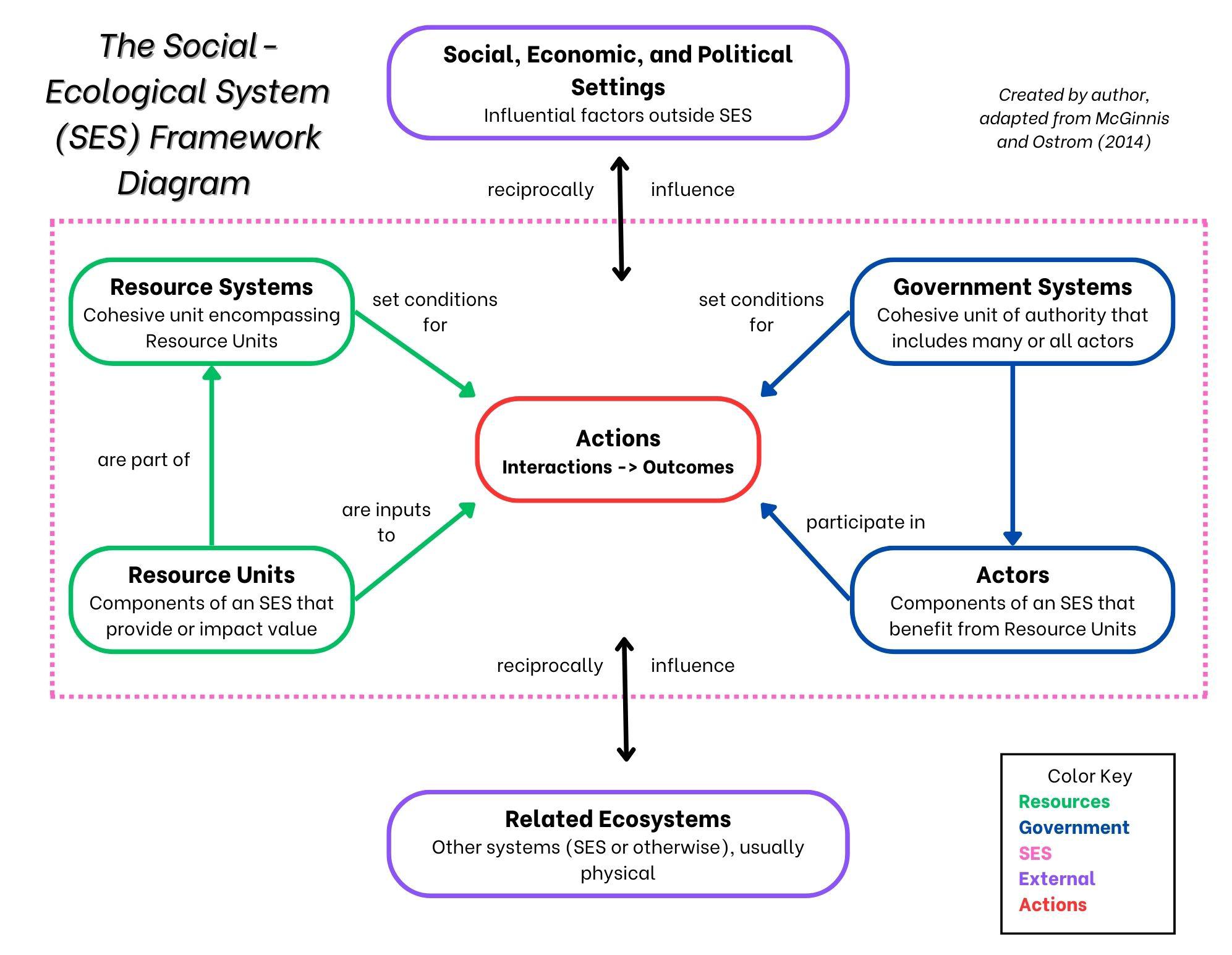

For this comparative case study analysis, a place-based strategy is employed to reduce confounding factors; both universities observed are located in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States in urban settings. There is also a temporal component to the analysis, with each university case consisting of one event occurring in the mid-20th century, one event occurring in the recent past, and one event that is currently ongoing. The framework used in this analysis is the McGinnis and Ostrom (2014) Social-Ecological System (SES) Framework, as illustrated below:

Planning, as an inherently intersectional field, requires a framework with the capability for intersectional analysis, which the SES framework provides. By analyzing the dynamism between and within Government, Resources, and Externalities, a sense of the nuanced interactions and their proceeding outcomes is more easily developed.

CASE 1: DREXEL UNIVERSITY

Founded in Philadelphia in 1891, Drexel University started small; the first 40 years of its existence saw all aspects of university life housed within its first and only building, aptly named the Main Building. As the years passed and the university became a prominent, accredited 4-year private research institution, the university grew in both population and acreage; today, Drexel boasts a student population of over 20,000 in-person students and a whopping 96-acre campus (Drexel University n.d. (a)).

EVENT CONTEXT

In the late 1960’s, University Redevelopment Area Unit 3, located on a main thoroughfare of West Philadelphia, was set to be the site of urban renewal (an activity funded by the federal government to address “blight”). The West Philadelphia Corporation (WPC), a newly formed development corporation that included Drexel as well as other academic institutions, planned a “scholarly urban oasis” in what was, at that time, the neighborhood of Black Bottom (Heritage West n.d.), a historically Black neighborhood with Victorian-style homes and many Black-owned businesses. This project displaced anywhere from 2,000 (Heritage West n.d.) to 10,000 (Susaneck 2024) Black Philadelphians to make way for the “precision medicine Tech Hub” (Huffman 2024) that housed biomedical, telecommunication, startup, and research companies.

Similarly major redevelopment has been needed to house Drexel’s 13,000+ undergraduate students who must complete a two-year on-campus living requirement (Drexel Univeristy n.d.(b)). Being just one of three major universities housed in West Philadelphia, housing has

become a commodity requiring increasingly more space. Drexel and UPenn’s expansion westward was already contentious, but in July 2021, a management group with connections to Drexel decided against renewing its 40-year contract to manage the University City (UC) Townhomes as Section 8 Housing (De Forest 2023) to make way for new apartments targeted to students. The demolishing of the townhomes meant displacing nearly 70 families. Sympathetic students held a massive protest at Drexel, while the “Save the UC Townhomes” coalition formed and mobilized against this development decision. Ultimately, the demolition proceeded, and the townhomes were destroyed. However, upon the completion of the new buildings, 74 units will be preserved as deeply affordable housing (meaning that those that make only 30 percent of the average median income could reasonably afford rent) (De Forest 2023).

As an attempt to discern the ways in which future university projects will impact the surrounding community, the third case event taken into consideration is Drexel’s Master Plan. Adopted in 2017, it outlines the design and development vision for the university and provides maps and mock-ups of changes crucial to “transforming the modern urban university” (Drexel University 2017).

SES BREAKDOWN

University Science Center Development

Social, economic, and political settings

Related Ecosystems

Resource Units

• Federally backed Urban Renewal

• The Black Bottom neighborhood

• Center City Philadelphia

• Black culture

• Black businesses

• Historical housing stock

• Available land

• Section 8 Housing funds

Resource systems

Actors

Government Systems

• The Black Bottom neighborhood

• Universities (incl. UPenn)

• Developers

• Businesses (Biomedical, telecommunications, startup, research)

• West Philadelphia Corporation (WPC)

• U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

Interactions

• University City Science Center planned

• Residents and sympathetic students protest

• Federal money awarded to WPC for construction

• Building constructed and is the first of many to come

Table 1 continued on page 33.

University City Townhomes Demolition Drexel Campus Master Plan

• Growing university populations

• Federal subsidies for Section 8 Housing

• The COVID-19 Pandemic

• Townhomes

• Townhome residents

• Tuition-paying university students

• Community organizations

• 40th street subway station

• Housing/land value

• The “neighborhood”/ district of University City

• Universities (incl. UPenn