Perfume: The Scent of Fashion

By Carla Seipp

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree Master of Arts in Fashion Studies

Primary Advisor: Francesca Granata

Secondary Reader: Christina Moon

MA Program in Fashion Studies

School of Art and Design History and Theory

Parsons the New School for Design

2015

Abstract

This thesis examines scent in its relation to the fashion system and Susan B. Kaiser’s concept of style-body-dress through the example of fragrance advertising. More specifically, it aims to answer the question of how subject and gender formation are created through perfume. It explores the psychological effects that perfume has on subject formation, and its specific influence on gender and sexuality in a neoliberalist and postfeminist context, using the theories of Pierre Bourdieu on habitus, Eva Chen on neoliberalism and Joanne Entwistle on the body. This theoretical groundwork will serve as a basis for the final chapter, which utilizes the semiotic theories of Roland Barthes to dissect five fragrance advertisements. They are Marc Jacobs Oh Lola!, Christian Dior Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet, Versace Crystal Noir, Estee Lauder Beautiful and Byredo M/Mink, each of which underscores a specific notion about perfume in relation to nostalgia, sexuality, femininity and gender boundaries. All of these conclusions will be summarized in order to reflect on the role of perfume in an academic discourse and the development of its commercial landscape for the future.

KEYWORDS: Scent, Perfume, Style, Fashion, Dress, Semiotics, Neoliberalism, Postfeminism

Introduction

The routine process of dressing is a process of layering. The typical individual begins their day not with placing and fastening clothes around their body, but with hygienically preparing their body. This tends to include the following: showering and washing of the body with soap, shampoo and conditioner, applying deodorant and moisturizer post-shower, and the application of beauty products such as hair spray and perfume, among other products. Each of these steps, these elemental layers, are scented, making the process of getting dressed much more intricate than it appears, and it also makes how one presents themselves to the public much more complex than just appearance; they are presenting how they smell. In short, they are fashioning their identity through scent.

Though not a ‘visible’ component, scent is part of someone’s style. Where fashion is a visible way of self-expression, perfume is a presentation of self that is invisible to the eye. What people smell is not as prominent as what they see. The aim of this thesis is both to prove and convince that perfume is worthy of a deeper integration into the field of fashion studies. Discussed within Westernized contemporary culture, an analysis of the following is presented in correlation to one another: existing fashion theory, components of women’s studies and gender studies, the psychology of scent, fashion branding and marketing and image analysis through semiological technique.

Perfume has been selected as the focus of this thesis because of its strong connection to theories on the fashion system, subject formation, and gender and sexuality. Perfume has two points of significance when it comes to subject formation. Firstly, it is the final layer of fashion-style-dress one applies to the body and also applied directly to the erogenous areas of the skin, making it not only the sealing of subject formation, but also a fashioning of gender identity and sexuality. Scent appeals to the most primal human instinct while also being a site of scientific and industrial revolution and development. Another dichotomy to note is the fact

that scent evokes nostalgic memory recall but also can stand for an archetype of what the subject wants to become in the future, i.e. a seductively scented siren, an innocent smelling adolescent, etc. In terms of temporality, it fuses the past and the future to become a marker of identity in the present.

Secondly, fragrance is deeply embedded within fashion and vice versa. As Annette Green (2010) writes: “Perfume, from the Latin per fumum, meaning through smoke, has been a barometer of society and its mores throughout recorded history. Like fashion, it provides a road map to people's strivings for individuality, self-aggrandizement, social standing, and feelings of well-being”. The fact that a majority of brands support themselves through perfume sales proves that scent is also vital to the life of the fashion industry. Chanel may not sell copious haute couture garments, however its signature scent, the floral aldehydic Chanel No. 5, has been on bestseller lists for decades. In his publication The Perfect Scent: A Year

Inside the Perfume Industry in Paris and New York perfume critic Chandler Burr recalls: “A man I know once sat next to Yves Saint Laurent at a Paris dinner party. He asked, ‘What portion of Yves Saint Laurent revenues are accounted for by perfume?’ Saint Laurent replied, ‘Eighty-three point five’” (Seipp, 2014). Perfume offers brands an extension of their marketing identity and provide an accessible route for consumers to own part of the brand.

Furthermore, as Marina Geigert (2008) writes, “The history of fragrance in the 20th century follows the same model as fashion: from exclusivity, high price and made-to-measure quality to the focus on middle market, mass production and democratisation (sic)” (32). This accessibility is not only in terms of price point but also venue location; rather than having to visit an upscale designer boutique, many consumers can simply purchase a bottle of high-end perfume at a discounted price in a duty free shop. Therefore the creation of a brand’s olfactory identity is just as important as its fashion identity. The definition of olfactory is “anything relating to our sense of smell” (Merriam-Webster), which indicates just how

expansive this opportunity for identity formation is. It can come packaged as a fragrance, a body lotion, a room spray, or even a candle. The rise in popularity for high-end candle brands such as Diptyque indicate a desire for even the scent of our homes to be reflective of a certain olfactory identity and social status.

Chapter 2, “Psychology of Scent and Its Influence on Subject Formation” places perfume into the discourse of style-fashion-dress. As explained in Susan B. Kaiser’s text Fashion and Cultural Studies (2012), ‘subject formation’ is the terminology for how one is in a constant state of ‘being’ and ‘becoming’(20). It positions scent as an extension of style-fashion-dress that not only reflects the individual’s identity, tastes and desires, but also that of their surroundings, or in the words of Pierre Bourdieu, habitus.

Chapter 3, “Selling the Myth: An Image Analysis” interprets five fragrance advertisements chosen for their correspondence with individual themes discussed in Chapter 1. Four out of the five advertisements are for a fashion fragrance, as the combination of the designer label, perfume and said perfume’s scent provoke certain attainable fantasies in the consumer, such as fashion capital, glamour, sex appeal, confidence, and so on and so forth.

“It [perfume] creates an image system, which the culture of fashion sustains in the form of costly scents, luxuriously designed flasks, richly poetic names, and erotically charged symbols” (Stamelman, 2006: 22). Perfume, especially in terms of how it is marketed, is an outlet for one’s desires to be socially accepted via scent. The examples used in this thesis are: Marc Jacobs Oh Lola! (nostalgia), Christian Dior Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet (gender formation), Versace Crystal Noir (postfeminist female sexuality), Estee Lauder Beautiful (hetero-performative female sexuality) and Byredo M/Mink (shifting gender identities). Each image is unpacked using the semiotics theories presented by Roland Barthes, which will be explained in the methodology portion of this chapter.

Jim Drobnick describes the influential importance of scent in his text The Smell Culture Reader, in saying:

Often delimited as a mere “biological” sense, scents are, on the contrary, subtly involved in just about every aspect of culture, from the construction of personal identity and the defining of social status to the confirming of group affiliation and the transmission of tradition (Drobnick 2006,1).

Drobnick’s quote provides a link between theories in the study of fashion and the study of scent by illuminating that scent, like fashion, is intrinsically embedded into our culture in various ways. Scent is also not just confined to the present, but can be an indicator of aesthetics carried on through generations. For example, if a young woman fondly remembers the fragrance her grandmother used to wear, when she herself reaches a senior age, she will, by nostalgic association, be more inclined to initially reach for the fragrance that her grandmother wore. Even if she does not end up wearing this scent, the perfume itself is a time marker of reaching an elderly age.

Drobnick goes on to explain that “The near future promises to contain an everincreasing use of rationalized scents in industry, the public sphere and everyday life” (Drobnick 2006, 3). Scent has already begun to infiltrate other arenas outside of the fragrance store; designers such as Joseph Altuzarra and Meadham Kirchhoff have commissioned perfume companies to create bespoke fragrances for their runway shows in the past, while Le Cinema Olfactif is a scented film screening experience that links the olfactory with the visual senses. The fact that the future is likely to contain even more enmeshment of fragrance in daily life requires a deeper investigation of, not only, the psychological effects that scents have on the individual and society as a whole, but also how scent is an incorporate of the interdisciplinary field that is fashion studies.

Despite its far-reaching influence, there is little humanities literature on scent. Director of the Social Issues Research Center, Kate Fox, explains that

The emotional potency of smell was felt to threaten the impersonal, rational detachment of modern scientific thinking. This demotion of smell has had a lasting effect on academic research, with the result that we know far less about our sense of smell than about more high-status senses such as vision and hearing (Fox 2009, 25).

However scent is far from being detrimental to scientific thinking, in fact, it is actually deeply intertwined with it; advances in one area benefit the other and vice versa. Utilizing the roughly five to six million olfactory receptors at our disposal (Fox 2009), humans are capable of identifying up to one trillion odors (Morrison 2014). This biological human trait evolved for the purposes of smelling out danger, sexual partners and nourishment, and triggering appropriate natural responses. Furthermore, our scent-memory recall mechanism is the fastest way for past memories to be triggered in the brain, making it superior to sound or vision in this aspect. Perhaps another explanation for the lack of academic writing on scent is its ephemerality; a fragrance cannot be captured in a photograph or perfectly replicated in words on a piece of paper.

There are various sources on the scientific aspect of scent, but unfortunately the implications of smell in other academic areas is less developed. This thesis aims to address this gap in this chapter, as well as in “Psychology of Scent and Its Influence on Subject Formation” and “Selling The Myth: An Image Analysis”.

While there are published humanities texts on scent — examples consulted for this thesis include Scent and the City: Perfume, Consumption and the Urban Economy, Japanese Fragrance Descriptives and Gender Constructions: Preliminary Steps Towards an Anthropology of Olfaction, and Gender Categorization of Perfumes: The Difference between Odour Perception and Commercial Classification — a synthesized analysis on the subject matter has yet to be presented in terms of the following: fashion theory, psychology of scent and image analysis. This thesis is a presentation of analyzed interdisciplinary research to

demonstrate the significantly notable influence scent and the perfume industry has on fashion and, ergo, fashion studies.

Literature Review

In my exploration of scent within the field of fashion studies, I will draw on the texts of several key scholars who have provided a theoretical framework for my research. As a visual analysis of five advertisements constitutes the core of this thesis, Judith Williamson’s seminal work, Decoding Advertisements, proved to be a crucial source for unpacking the symbols presented in each image. Williamson’s precise dissection of advertising images provided an outline for the layers which need to be addressed such as visual components, layout, text, color, cultural context, etc. Williamson (1978) also points out the need to tie advertisements into the existing social and ideological values in place at the time it is produced by stating that “This is the essence of all advertising: components of ‘real’ life, our life, are used to speak a new language, the advertisement’s” (Williamson, 1978, 23).

She also looks at two fragrance advertisements, both with celebrities in them, which provided additional help in the analysis of the first two examples in this thesis. While Williamson’s example was a Chanel No. 5 advertisement featuring Catherine Deneuve, the following points were nonetheless very helpful: “So what Catherine Deneuve’s face means to us in the world of magazines and films, Chanel No. 5 seeks to mean and comes to mean in the world of consumer goods” (Williamson, 1978, 25) and

“The ad is using another already existing mythological language or sign system, and appropriating a relationship that exists in that system between signifier (Catherine Deneuve) and signified (glamour, beauty) to speak of its product in terms of the same relationship; so that the perfume can be substituted for Catherine Deneuve’s face and can also be made to signify glamour and beauty” (Williamson, 1978, 25).

These two quotes provided further analytical insight into the reason for the popularity of celebrity fragrance endorsement: the ability for the viewer to connect with the product on a further emotional level. Finally, Williamson (1978) states: “The product is always a sign within the ad: as long as you are not in possession of it or consuming it, it remains a sign and a potential referent; but the act of buying/consuming is what releases the referent emotion itself” (Williamson, 1978: 36). These emotions can range from happiness to nostalgia, but are the prime reason for product consumption. The stronger of an emotion an advertisement can generate, even if it is simply shock value, the more effective it is on the consumer.

Discussing the more internal motivators for product consumption, fashion scholar

Susan B. Kaiser’s book Fashion and Cultural Studies (2012) explores the relationship between subject formation and style-fashion-dress. As suggested in the book’s title, Kaiser aims to demonstrate that fashion is a product of cultural influence, and thusly, that culture is influenced by fashion. With this intermediation, subject formation ensues. An individual’s application of style-fashion-dress documents and expresses their identity both as a moment in time and how their subject formation fluctuates and evolves constantly through time. To explain such notions, Kaiser discusses the theories of agency, habitus, and performativity.

Agency is described as “the freedom or ability to exert one’s ‘voice’ and to resist power relations in some way” (Kaiser 2012: 30-1). She references Pierre Bourdieu’s term, ‘habitus,’ from his 1984 text Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste and also incorporates Carol Tulloch’s concept of style narratives. Habitus entails the social, cultural and physical spaces the individual navigates on a daily basis, whilst style narratives give the art of self-fashioning an autobiographical importance of expressing multiple aspects of the individual’s life. “Habitus is one of the ways in which people navigate issues of agency and structure in everyday life, through situated bodily

practices that are culturally ingrained but that also have their own personal spin” (Kaiser 2012: 31). One of these bodily practices is the application of scent. Smelling ‘good’ indicates a practice of proper body hygiene, one of the most basic requirements of modern day society. However, how this good smell is created is where personal agency comes in. The fragrance we wear can express just as much about us as the clothing we wear. Depending on the scent, one can simply smell fresh and clean, thanks to an aquatic eau de toilette, or take on an entirely different, more seductive character through a floriental scent containing vanilla, musk and sandalwood notes. The fact that fresh notes indicate cleanliness and more animalic notes seduction are a cultural construct, whereas the choice the individual makes between the two indicates personal agency.

The act of constructing one’s style-fashiondress becomes a daily ritual which stakes out the individual’s place and identity, including their gender and sexuality, within society. This performance of self-fashioning can therefore be seen as a direct reflection of the tastes of his or her surroundings, which “is regulated by cultural discourse, but it becomes part of the ongoing experience of fashioning the gendered body on a personal and social level, as well” (Kaiser: 123). A woman will wear a fragrance to abide to society’s requirement of smelling ‘good’, and in wearing a women’s scent, which clearly differentiates itself from a male fragrance through the use of stereotypical feminine fragrance components such as white florals, vanilla or fruit accords, she is also adhering to her culture’s idea of what a female should smell like.

Kaiser’s theories prove to be an essential foundation for this thesis, for scent can be seen as a crucial component in this constantly fluctuating construction of self. A fragrance not only expresses an individual’s identity, but can also be seen as a reaction to the beauty aesthetics of their surroundings. It is not only the what but the how which is important to note. One cannot fully address the concept of style-fashion-

dress without the inclusion of scent.

According to cultural theorist Joanne Entwistle, in her text The Fashioned Body, to dress oneself is to experience a metamorphosis of the body. The subject fashions the body in order to assume their place in society, with dress building the single degree of separation between the individual and society, and between the private and public spheres. Scent is a part of this layer of separation and therefore can be seen as an external representative of the individual. The perfume we wear says as much about our own individual identity as it does about our place in society. Not only can the choice of scent be molded by the expectations and aesthetic values of one’s surroundings, but also by the price class of the fragrance, be it an affordable drugstore scent or a higher-priced niche product.

When discussing the fashioning of the body, Entwistle illuminates the importance of sexuality and sexual identity, which are expressed through scent but also reflect society’s ideal incarnation of sexuality. In advertising, this fashioning of the body and sexual identity is further heightened in order to sell not only a product but also an ideal aesthetic. This thesis’s dissection of contemporary women’s fragrance advertisements makes the context of the society in which these images were created all the more important. In terms of modern-day society, the exponential growth of the perfume market was also mirrored in the development of neoliberalism.

In her essay, “Neoliberalism and Popular Women’s Culture: Rethinking Choice, Freedom and Agency” (2013), Eva Chen defines neoliberalism as a philosophy based on the idea that the individual has an unrestrained ability to choose what benefits him or her the most. However this individual agency ultimately ends up being confined within the frame of the norms of their environment. It is not the power of social norms that determine the individual’s choice but

rather the underlying conditions of their environment, making this a more subconscious power. Chen explains,

As a new form of self-governance, where the only guiding principle is marketization and self-interest, neoliberalism encourages individuals to willingly and freely choose to follow the path most conducive to their selfinterest: the path which often turns out to be the normative one, the one for which the state has provided the best conditions (Chen 2013, 443).

This idea of subconscious manipulation is also prevalent in advertising, which sells the image of the liberated woman to the consumer, but whether or not this woman is actually liberated remains debatable. For example, Angela McRobbie states:

Women disguise their bid for power by means of masquerade and patriarchal authority absents itself from the scene of judgement and delegates this power to the beauty and fashion system which requires constant self-judgement and self-beratement, against a horizon of rigid cultural norms. This makes it look as though women are ‘doing it for themselves” (McRobbie 2004: 68).

In terms of fragrance consumption, this means that although the consumer may feel like she is purchasing the perfume by her own choice, she is in fact buying into the normregulated ideals which are being sold to her through the image. Purchasing the perfume is not necessarily solely about whether she likes its smell or not, but also the desire to fit into a social and aesthetic ideal. Furthermore the act of purchasing a product for oneself is an act of staking one’s existence, in line with the ideology behind Barbara Kruger’s seminal artwork I Shop Therefore I Am

Another crucial author to this thesis is Jim Drobnick. The Smell Culture Reader, edited by Drobnick (2006), is a collection of essays which are categorized under the following sections: Odorphobia, Toposmia, Flaireurs, Perfume, Scentsuality, Volatile Art, and Sublime Essences. During the research for this thesis The Smell Culture Reader was the only volume which collected a variety of essays depicting and analyzing smell in a theoretical light, making it an important marker in the evolution of scent as an academic subject.

According to Drobnick, scent influences the daily social interaction between the self and society. This includes the perceptions of others, the concept of self-fashioning and beauty norms. Therefore, the examination of scent requires an interdisciplinary approach.

Continuing this notion, “Chapter 2: The Sociology of Odors,” by Gale Largey and Rod Watson quotes Georg Simmel’s 1908 text Sociologie [sic] which states that an individual’s smell forms one of the foundations for modern human sociology.

That we can smell the atmosphere of somebody is the most intimate perception of him and it is obvious that within the increasing sensitiveness toward impression of smelling in general, there may occur a selection and a taking of distance, which form to a certain degree, one of the sentient bases for the sociological [sic] reserve of the modern individual (Simmel, 1908: 658)

Scent is a component in this Darwinian process of selection, as smelling good is likely to attract more individuals than repel them. Therefore, one could say that the scenting of the body has an underlying primal instinct to it, that of socialization.

“Chapter 23: The Eros and Thanatos of Scents,” by Richard H. Stamelman utilizes the Greek terms eros (love) and thanatos (death) to discuss fragrance. Stamelman states that the erotic image of the fragranced woman is marked by counterparts concerning morality, civilization, seduction, spirituality, etc.. She is neither one or the other, but instead exists in a constant movement between these two. Thus, the boundaries of sexuality and identity are now more fluid, as evidenced in the images sold to us by modern-day fragrance advertising. The counterparts in morality (good versus evil), civilization (barbaric versus cultured), seduction (virgin versus whore) and spirituality (physical versus ethereal) are dependent on the image, but still prevalent.

In Past Scents: Historical Perspectives on Smell, (2014) Jonathan Reinarz explores the history of smell and fragrance from history to modern times. While Reinarz discusses scent in relation to categories such as religion, race and social class, it is his writing on

gender that is relevant to this thesis. Reinarz states that it is specifically the female sex which is marked and articulated through scent and putrescence, with both positive and negative representations. He notes that historically, heterosexual females are primarily presented in fragrance advertisements, but as sexual boundaries expand so too do the women that are featured. While the notion of this gender representation will be further discussed through the examples in Chapter 3, the statements made by Reinarz are the reason for this thesis focusing solely on women’s fragrance advertisements. Not only are cosmetic rituals such as fragrance more of a construct targeted towards women (the recent rise of the metrosexual can be seen as a development of this ritual in the male sphere), but the female target market is also a more lucrative one. The final example in this thesis, a unisex scent by Byredo, features only the female body but also addresses the expansion of gender boundaries, not only in fragrance but also in society.

In Media and Nostalgia: Yearning for the Past, Present, and Future (2014), Katherine Niemeyer states that modern-day society’s romantic relationship with nostalgia implies a dysfunctional relationship with time. Nostalgia represents an attempt to curtail the speed of life caused by new technology, and the desire to travel afar (Wanderlust) or back home (Heimweh) through the use of media and consumerism. In turn, media both re-enacts and generates nostalgia, resulting in a reciprocal relationship. Niemeyer’s theory helps to set the analyzed fragrance advertisements in this thesis into a wider context. Fragrance acts as a strong indicator of nostalgia not only because of the phenomenon of scent memory recall, which allows the mind to travel to different times and places, but also because it is a product whose form has rarely changed since it was first invented, making it a point of familiarity in an otherwise ever-changing world. As such, scent can be both a satisfier for Wanderlust but also a trigger for Heimweh. These roles can be reenacted through advertisements as well, for

example an exotic scent advertised through tropical settings and colors or a comforting scent which is sold through the use of soft clothing made of wool and a roasting fireplace. The former case speaks to the consumer’s desire for Wanderlust, the latter for his or her desire for Heimweh.

Methodology

This thesis consist of a visual analysis and quantitative research of primary sources. Image analysis constitutes the core of this thesis, as demonstrated by the five advertising examples in Chapter 3. Williamson’s body of work provided a template for the process of dissecting each advertising campaign, while Kaiser’s theories of style-fashion-dress and subject formation were highly applicable as each image constructs an ideal identity prototype through its visuals that is sold to the consumer.

Roland Barthes is an esteemed figure in the field of semiotics and another author whose method of image analysis was consulted, specifically his chapter “The Advertising Message” from the text The Fashion System. Barthes specifically uses the following terms: signifier, signified, connotation, denotation and mythology. Explained simply, a signifier is something which denotes and the signified is something that is connoted. The mythology is the overall image that is being sold. Putting this into the context of a fragrance advertisement, the signifier of a model would denote feminine beauty, therefore beauty is the signified. In conjunction with a bottle of perfume in the picture, the mythology is that buying this fragrance will make you as attractive as the model is connoted. Utilizing these terms, along with my own subjective interpretations of the advertisement, constitute the majority of this thesis.

II. Scent and Its Influence on Subject Formation

Perfume is an elemental layer in the process of dressing, but, it is also so much more. Yes, in terms of getting dressed as a whole, the application of perfume is just one of the many layers, but while this chapter looks at perfume in the context of dressing in the style-fashion-dress system, it also looks at perfume in terms of its psychological influences upon the wearer and the smeller, i.e. how perfume contributes to subject formation and social interaction. Within the discussion of subject formation, how scent affects the cultural and social discourse of gender and sexual identity is revealed. The framework for this analysis is built through postfeminist theories within the neoliberalist construct, as it is explained by Eva Chen, who states that through the act of consumption a ‘false’ sense of free agency is created, for this consumption is ultimately steered by the ideological guidelines of their society.

Understanding dress (note that the body is also to a certain extent ‘dressed’ in scent) means understanding the constant dialect between the body and self. As Entwistle writes:

Dress is both an intimate experience of the body and a public presentation of it. Operating on the boundary between self and other is the interface between the individual and the social world, the meeting place of the private and the public (Entwistle 2000, 7).

One could say the same about perfume. It is also an intimate experience as it is sprayed directly on the naked skin of the individual. Furthermore, when one wants to smell the fragrance of another person, the personal boundaries of distance are crossed to a certain extent when leaning in for a whiff of that person’s neck or wrist. A public presentation of the self through scent can either be almost silent in the form of a delicate or lightly applied scent or extremely loud through the use of a bold or over-applied fragrance. Either way, the perfume an individual wears explains to the public a part of their personality or mood by leaving a trail of scent behind.

The area between the self and other is the operating ground for gender. Feminist theorist Judith Butler (1990) refers to this “gendered interplay between cultural discourse and everyday habitus as performativity” (Kaiser, 2012: 123). As it is a crucial part of subject formation, gender functions in an identical way, not only reflecting the individual, but also the cultural and social space within which it functions. Throughout history, especially the female sex has been marked through olfactory identity, both in a positive and negative light (Reinarz 2014). One can speculate that the reason for this is that beauty capital has played a stronger role for women than it has for men, as body maintenance is more highly scrutinized for the female sex. Quoting psychologist Havelock Ellis, Kate Fox writes in The Smell Report: “Until the late 18th century, he claims, women used perfume as a means of emphasizing, rather than masking, their natural body odor. Animal perfumes such as musk had the same function as corsets which were used to exaggerate the female form. It seems that men by contrast, have throughout history felt less need to advertise their masculinity with perfumes, or indeed any other devices” (Fox 2015, 23). Here, Fox draws an interesting link between fragrance and fashion. While both offer a variety of styles for women to wear, they nonetheless still adhere to a certain fashion dictated by society, and a manipulation of the body to an extent.

Another reason for only focusing on one specific gender of fragrance advertisements is the stereotypes associated with female fragrances. As fragrance firm consultant Bodo Kubartz writes in his article “Scent and the City: Perfume, Consumption and the Urban Economy”,

Cultural anthropologists have pointed out that these two civilized senses [vision and hearing] are morally constructed and equated with masculinity, economic rationality, the mind, and modern capitalism. The three lower senses of taste, touch and smell are aligned with femininity, irrationality, and the body (Synnott, 1993; Classen et al., 1994; Classen, 1998; Howes 2003). (Kubartz, 2009: 443)

As psychologist Anna Lindgvist (2013) writes: “Whether a fragrance is interpreted as feminine or masculine is probably related to stereotypical associations with the feminine gender (represented as e.g. ‘flowery, fruity, sweet’) and to the masculine gender (represented as e.g. ‘smoky, leather’)” (221). In the present day, this gender-marked style of selffashioning can be seen as part of this form of self-governance, in an attempt to adhere to social norms and the personal ability to operate within the fashion/beauty system. Fashionstyle-dress therefore is a perpetuator and result of postfeminism. Women move from being objectified to having a personal agency of choice (Gill 2007). “So significant are clothes to our readings of the body that they can come to stand for sexual difference in the absence of a body” (Entwistle 2000, 141). In smelling a perfume, be it at a department store or the passing of a perfumed woman on the street, the scent indicates the sex of a woman and her sexuality in absence of her physical body.

“Despite the fact that the individual stakes out their identity within the confines of their habitus and cultural space, there is nonetheless room for personalization within this arena” (Kaiser 2012). What perfume one chooses to wear as ‘their’ scent is their personal spin. The choices made are embodied choices. This desire for social acceptance, which Kaiser explains as being an essential part of subject formation, plays a highly influential role in deciding your perfume, for how you smell to others could very well determine the longevity of interaction; a scent can either repel or attract.

Fashion theorist Carol Tulloch’s concept of style narratives, which Kaiser explains as being “part of the process of self-telling, that is, to expound an aspect of autobiography of oneself through the clothing choices an individual makes” can be augmented to incorporate perfume, because what perfume one chooses to wear is a form of self-telling through the sense of smell (Kaiser 2012, 6). Furthermore, in hindsight, scents are later attributed to a certain time period in an individual’s life, be it their first fragrance as a teenager or the scent

of their mother whilst growing up. An important aspect of perfume in the discourse of subject formation is that what scent a woman wears involves a great deal of agency. Choosing what perfume to wear is much more of a commitment than when choosing what clothes and accessories to wear, for there is a frequency and regularity component in perfume wearing. Selecting your ‘scent’ requires a great deal of agency, but also a great deal of exterior influences, especially in the form of perfume advertisement.

Kaiser states: “Part of dressing or fashioning the body is a kind of ritual experience or personal conditioning that occurs in everyday life”(31). Part of this ritual experience is perfuming. A majority of today’s consumers may simply spritz on their fragrance as the ‘final touch’ for their outfit before they walk out the door, however these seemingly nonchalant act is a ritual in itself. Through this personal conditioning and therefore subject formation, one defines oneself within the inhabited habitus. Habitus is a phrase coined by Pierre Bourdieu and entails the social and class surroundings one inhabits and ultimately attempts to adapt to. This adaption for the sake of social acceptance is especially crucial when it comes to the creation of one’s olfactory identity, which is a reflection of the individual’s desires and therefore of one’s habitus. Oud fragrances are a useful example of habitus adaption.

Originating in the Middle East, where a stronger, more oriental smell is desirable, these types of scents slowly started infiltrating the Western market in the late 2000s with scents such as Oud Wood by Tom Ford. Although these fragrances were still altered to fit the Western market, the popularity of oud scents has since risen. Similarly, when Shalimar was launched by Guerlain in 1925, it was the first perfume of the oriental category; in 2013 woody oriental scents proved to be the top-selling perfume category for prestige brands (NPD, 2013).

III. Selling the Myth: An Image Analysis

By means of the Eros of scent, woman becomes a hybrid, a hyphenated being: visible-invisible,proximate-distant, corporeal-spiritual, ephemeral-

enduring, earthy-celestial, base-sublime, primitive-civilized, expressivemute, innocent-seductive” (Stamelman 2006, 263).

Scent is a literally transformative medium. It is a fascinatingly fleeting object, so ephemeral that it disperses in seconds, yet its emotional associations can last a lifetime. Perfume, its enduring, commercially commoditized incarnation, capitalizes on this power. Stamelman (2006) writes: “Insofar as it is a phenomenon inseparable from dress and fashion and is a social reality essential to culture and civilization, perfume eloquently expresses the psychological needs, social values, and symbolic associations of its age” (32). Perfume has the power to transcend one merely from a sensory experience to a psychological experience and one of desire. It was in the early 1920s that Edward Bernays, nephew of Sigmund Freud, first introduced the idea of marketing driven by desire (The Century of Self, 2002). This seminal approach shaped the landscape of marketing as it is today. A component of the image analysis in this chapter illustrates how perfume advertising capitalizes upon Bernays’ approach.

The advertising campaigns which sell it to the consumer are faced with the challenge of recreating the olfactory experience of smelling the fragrance through other channels. “The olfactory economy works through a combination of the symbolic part of a brand and the elusive, evanescent aspect of a fragrance” (Bubartz, 2009: 445). Therefore, typography, color palette, props, lighting and the model come together in an attempt to activate the consumer’s olfactory, and pecuniary, interest. Roland Barthes’ semiotic theories will be utilized in order to unpick the different layers in five advertising campaigns. The signifiers (what is connoted) and signified (what is denoted), and how these images tap into the consumer psyche, are analyzed in this chapter. The advertisements used are: Marc Jacobs Oh, Lola!, Christian Dior Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet, Versace Crystal Noir, Estee Lauder Beautiful and Byredo M/Mink.

When speaking of the concept of recreating fragrances for

advertising, nostalgia is an important term to keep in mind. Academic author Katherine Niemeyer notes: “Media produces contents and narratives not only in the nostalgic style but also as triggers of nostalgia” (Niemeyer 2014, 7). Niemeyer’s term of ‘media’ could also be seen to include perfume, since this object is not only a trigger of nostalgia but often marketed in a nostalgic style.

It is not only nostalgia that is essential to the analysis of perfume advertising, but also sexuality and gender representation. Jonathan Reinarz writes that “Traditional gender divisions also map directly onto the organization of the scent industry,” (Reinarz 2014, 216).

This is not only evident in the choice of whether a fragrance is marketed towards men, women or unisex, but also in the type of formulation, i.e. men’s cologne or women’s perfume. Furthermore, certain olfactory notes such as rose are attributed as being feminine notes, whereas a scent such as vetiver is generally seen as a masculine one. The choice of gender influences the smell, packaging, bottle shape, typography and scent strength of the product. Citing Some Notes on the History of Perfume Types by Gerrit Willem Ovink, typography expert Charles Bigelow explains:

“In describing the mood created by such perfume types, Ovink suggests that the letterforms themselves suggest personality traits such as narcissism, selfishness and sensuality.’ Furthermore, ’perfume is marketed as an agent of communication of social messages and, par excellence, of sexual messages – romance, aphrodisia, seduction – and it is not surprising, therefore to find that gender is strongly marked in perfume typography’” (Bigelow 1992, 246).

For example, a cursive font in the context of an advertisement can either read as artisanal as it mimics the handwriting of a human being rather than a machine, or as sensual and feminine as it evokes the curves of the female body. Exploring gender messages and sexuality is one of the crucial elements in analyzing fragrance advertising campaigns, with this thesis focusing on those marketed towards women. Jonathan Reinarz (2014) states that

While heterosexual women clearly have been the prime targets and subjects of perfume advertisements, the types of women depicted in such media have recognizably changed over time” (115).

As the following examples will show, modern-day fragrance advertising has multiple layers when it comes to the woman being represented in it. After all, to go back to Chen’s description of postfeminism in a neoliberalist context, the point here is to sell the product to female consumers as a choice of their own, whereas perhaps older, traditional fragrance advertisements were more catered towards women wanting to smell good for the sake of attracting a husband. It isn’t just the woman being presented in the image that is of importance, but also whose gaze she is being captured with. The concept of the male gaze is most prominently discussed in Laura Mulvey’s text, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. Mulvey not only speaks of the external male gaze, but also of the male gaze internalized in the female subject, resulting in a self-policing of the self in order to appeal to the incoming gaze (Mulvey, 1975). Reinarz discusses this topic by stating that “It has been suggested that women have been as frequently subjected to a ‘male nose’ as they have to the more familiar, predatory ‘male gaze’” (Reinarz 2014, 114). This indicates that women’s perfume choices, and therefore the advertising for these scents, are based on the idea of appealing to the male nose. Thus, the fragrance advertising image is not exempt from female objectification within patriarchal society. However, as several of the following examples will show, subversive counteracts to this can be found in modern-day advertising.

Nostalgia: Marc Jacobs Oh, Lola!

Illustration 1

Oh, Lola! is a floral-fruity women’s fragrance released in 2011 under the Marc Jacobs brand. Marc Jacobs was founded in 1986 in New York City and is known for its modern American sportswear. The company launched its first fragrance in 2001 with actress Sofia Coppola as its face (Marc Jacobs), photographed by Juergen Teller. Oh, Lola! was created by Yann Vasnier, Calice Asancheyev-Becker and Ann Gottlieb (Basenotes). Its is a flanker to the 2009 Marc Jacobs fragrance, Lola.1 It has head notes of pear and raspberry, heart notes of peony, magnolia and cyclamen, and base notes of sandalwood, tonka bean and vanilla (Basenotes).2 The scent is described by the company as “flirtatious and charming with a sparkling personality. It leaves you feeling light-hearted and youthful” (Marc Jacobs) and as “More of a Lolita than a Lola” (Lidbury).

1Flanker is the industry term for a fragrance which is not launched as an independent scent but as a continuation in the range of a previously launched product

2 Every traditional perfume composition contains a head (top), heart (middle) and base note. The order is determined by the silage of each component, which means how long it lasts on the skin. Therefore lighter scents such as citrus are often found in top notes and heavier scents such as musk and oakwood are found in the base notes.

The coordinating advertising campaign is photographed by Juergen Teller and features actress Dakota Fanning, who was 17 years old when the image was taken (Illustration 1). The advertising image was banned in the UK by the Advertising Standards Authority for being “sexually provocative” and sexualizing a minor. The campaign in question features the trademark Marc Jacobs type font, an Arial-esque lettering which is fairly gender neutral but has rounded edges. The color white creates a rectangular frame around the campaign image, with ‘The New Fragrance for Women’ written above it and the text ‘Oh, Lola!’ ‘Marc Jacobs’ written underneath it.

Dakota Fanning sits on the floor in a rose colored space wearing a light beige and white polka dot dress with scallop edged hems at the bottom and sleeves, as well as across the chest. Her blonde hair is straightened and parted in the middle, and she is wearing minimal, neutral makeup. Her chin is pointed slightly downward and her eyes are looking directly into the camera. Her legs are stretched out in front of her in a parallel position and her left arm is positioned behind her, with Fanning leaning slightly back. Between both legs she holds a large perfume bottle of the Oh, Lola! scent in her left hand. The bottle is a transparent rose colored, vase-shaped container with Oh, Lola! and Marc Jacobs written on the upper third of container. This section is topped with a cylindrical silver component. A large rubber rose constitutes the bottle cap. The rose consists of three layers in a shade of red, pink and purple respectively. A large green leaf juts out of the lower left side of the flower. The lighting of the image is in Juergen Teller’s signature style, with an overexposed, bright light facing the subject head on. The harsh lighting has a color-fading effect on the image, evoking a nostalgic, 70s-esque feel.

According to Katherine Niemeyer (2014), “‘Nostalgia’ is the name we commonly give to a bittersweet longing for former times and spaces” (1) and “very often expresses or hints at something more profound, as it deals with positive or negative relations to time and

space. This related to a way of living, imagining and sometimes exploiting or (re)inventing the past, present and future” (2). This specific case further underlines nostalgia due to the fact that it is a flanker fragrance. As Bubartz (2009) notes: “Flankers-as-sequels are ways for producers to facilitate continuation of communication and media strategies and thereby create identities. This [produces an] aspect of heimat-creation in products” (448). Dr. Heike Jenss, in her essay Cross-temporal Explorations: Notes on Fashion and Nostalgia, states that “the stimulation of memory and nostalgic feelings has certainly become an important practice in marketing and consumer culture,” and “Survivals and representations of the past are not just passively viewed or consumed; they are open to new interpretations and become integrated and synthesized with new experiences in the present” (Jenss 2013, 112). The faded color of the photograph and the style of Fanning’s dress are signifiers which give the image a nostalgic effect. The color choice hints at an old photograph that has faded with time, or that the image was taken on a less advanced camera model that is unable to offer a better color payoff. The white frame around the image, paired with the overexposed lighting, are reminiscent of a Polaroid camera, which is outdated technology in comparison to modern-day technology. In accordance with Niemeyer’s theories, this longing for an image taken in decades past could be seen as a result of the fast-paced image turnover of today’s internet generation. Therefore, this advertisement represents a longing for images that are consumed at a slower and more thoughtful pace. Additionally, throughout their lifetime, women’s different developmental stages are accompanied by specific scents which not only help form their individual identity in each period of time, but also create ‘scent triggers’ that mark each episode and can be found later on in life, thus triggering memory recall. this nostalgia for decades past may incite the consumer to buy the product if there is a certain connection to the 70s-esque vibe of the image, and once she sprays on the fragrance and creates her own memories with it, this

creates a newly synthesized experience connected to the scent, a merging of the past and present through the same, or more likely similar, scent. As Judith Williamson (1978) writes: “There is no real present in advertising.You are either pushed back into the past, or urged forward into the future.” (Williamson, 1978: 154-155)

This supports John Berger’s (1972) notion that “Publicity is, in essence, nostalgic. It has to sell the past to the future” (139). Williamson (1978) adds: “Since it is impossible for them to invoke the actual, individual past of each of their spectators — the past that does go to make up personality — they invoke either an aura of the past, or a common undefined past” (158). Perfume advertising transforms the present (the ad) into the past (nostalgia) by activating memories and associations in the consumer when he or she smells it, or by the imagery utilized in the ad. Similarly, retrotyping, a term introduced by Katherine Niemeyer (2014), curates an image of the past which only incorporates facets of it that benefit the aim of selling said picture to the consumer. In this case, the era of the 1970s is evoked, but only its stylish incarnation, not the economic crisis of the decade, Vietnam war, women’s continuing struggle for equality, etc.

Moving on to the analysis of Fanning’s pose, it is understandable why the advertisement was deemed controversial. The phallic shape of the perfume bottle positioned in Fanning’s crotch area, combined with her come-hither look, can be seen as sexualizing a minor. Her leaned pack pose denotes nonchalance, but also passivity as a sexual object.

Furthermore the overexposed lighting and bare background can be interpreted as the image being taken in the studio of an inexperienced, and sexually predatory, photographer. While the rose bottle cap, along with the rose and pink color palette, connotes a symbol of femininity, given Fanning’s age, the rose in bloom can also be a signifier for the blossoming young woman. Flowers are also often associated with female genitalia, for example as evidenced in the Flowers series by Robert Mapplethorpe, giving the blooming rose an even

more sexualized undertone. Marc Jacobs emphasized the Lolita-esque figure meant to represent the perfume. This term is derived from the character in Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel of the same name about a young girl that seduces an older man, her stepfather to be exact, giving an added sexual layer to the image. The advertisement is contradictory to an extent: it is marketed as a women’s fragrance, yet features an adolescent girl in its campaign. Perhaps this choice was simply a provocative one, or it can also be seen as reflecting on society’s obsession with youth. Furthermore, in conjunction with the aspect of nostalgia, the image may be attempting to trigger the consumer to reminisce about their adolescent, rebellious years and cause her to purchase the product.

The fragrance’s name, through the explanation mark, indicates that this Lola character being evoked has done something outrageous or shocking, while the scent’s notes of fruit, light florals and vanilla underline the youthful and innocent feel of the scent. This duality underlines the codes of the Marc Jacobs brand. The designer himself is most famously know for bringing the heroin-chic, grunge look to the high fashion world, which at the time was deemed as shocking despite the fact that these were very wearable, casual clothes being presented. In a similar vein, the Oh, Lola! fragrance has a provocative undertone in the way that it is marketed, yet at the same time, the fragrance itself is constructed as a lighthearted, feminine scent. Whether it is grunge or perfume, the Marc Jacobs brand markets itself with a hint of irony.

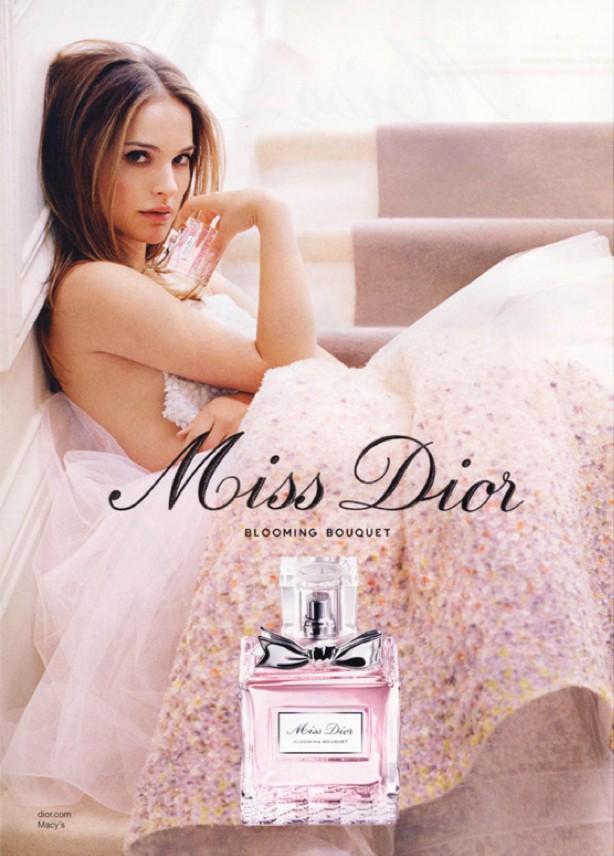

“The Extreme Elegance of Gentleness”: Christian Dior Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet

Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet is a fruity floral eau de toilette launched by the fashion house of the late Christian Dior, founded in 1946 (Berg). As one of the most influential designers of the 20th century, Dior’s fashion innovations include the New Look, comprised of an extravagantly full tulle skirt paired with a waist cinching T-bar jacket. For the past three years the brand’s creative director has been Belgian designer Raf Simons, who is most wellknown for his minimalist work at Jil Sander. The fragrance was composed by Dior’s exclusive perfumer François Demachy. He states that

“Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet is a smooth and carefully formed perfume, not a sensory assault, but rather a halo, like an aura. It’s a ‘bubble’ perfume, one possessing the extreme elegance of gentleness” (Fashion Gone Rogue).

The fragrance contains head notes of Sicilian orange and citrus, heart notes of Damask rose and peony, and base notes of white musk and patchouli (Basenotes). The scent was launched in 2008 as Miss Dior Cherie Blooming Bouquet and then relaunched as Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet in 2014. It is a flanker to the original Miss Dior scent, which was launched in 1947.

Illustration 2

The corresponding advertising campaign features actress Natalie Portman and was photographed by Tim Walker (Illustration 2). The image features Portman sitting on a white stairwell with beige carpeting, presumably in an affluent building given the pristine condition of the walls and carpeting. There is an overhead light source lightly shining into the scene, presumably sunshine from a window. Portman is leaning against the wall with her knees bent, wearing a Christian Dior haute couture dress made of tulle and silk featuring hundreds of floral embroideries both on the top and skirt. The dress starts off white at the top and has an ombre effect going into the mauve and pink embroideries at the bottom of the skirt, while the underskirt is white. The voluminous skirt is draped all across Portman’s lower body and torso. The bustier part of the strapless gown is left unzipped, exposing Portman’s upper ribcage.

Her left arm is positioned over her upper stomach and her right arm is bent, holding a bottle of the pale pink colored perfume to her chest. Her brunette hair is parted in the middle and has a straightened yet slightly unbrushed appearance, while her eyes are adorned with a classic flick of black eyeliner and her lips colored in a pale rose. The bottom half of the image features the words Miss Dior in a cursive black font with the words blooming bouquet printed in a small font underneath. Beneath the text is a fragrance bottle. It is composed of a clear acrylic rectangular cap bearing a silver bow and a rectangular glass bottle with a white label.

The house of Dior is one of the most widely recognized names in fashion, and one of the top French ready-to-wear, as well as haute couture, design labels. A classic design of the house, the New Look, is represented through the full skirt and corseted upper body of the design featured in the image. Its longstanding legacy is echoed in the classic cursive handwriting on the bottle, which perpetuates the myth of an elegant, educated, upper class character, and also underlines the aforementioned smooth character of the scent It also

underlines the ideal of French chicness which the brand is known for. Typographer and historian Charles Bigelow states that

“The typographic image of a perfume name is a form of symbolic synaesthesia that connects visual, auditory and olfactory images — the graphic forms of the written name, the sound of the spoken name, and the fragrance” (243)

The Miss Dior cursive typography is very languid, almost to the point of appearing fragile, and curved, much like the body of the woman that is depicted in the image. This typography reinforces the myth of a romanticized feminine ideal. Demachy’s statement about the fragrance includes words like “aura, halo, extreme gentleness”. The light which shines on Portman from behind and above is a literal interpretation of this halo/aura aspect, while the subdued notes of light citrus, feminine rose and understated white musk support the extreme gentleness the fragrance is meant to convey. The pastel color palette not only supports this notion of lightness, but also a younger woman, by choosing a pink color over a more classic color such as rose. Also the name Miss Dior, as opposed to Mrs., indicates an unmarried and younger woman. Despite this innocent demeanor, the unzipped bustier, Portman’s seductive gaze, which is drawn extra attention to due to her eye make-up, ‘bedhead’ hair and the placement of the perfume bottle near an erogenous zone (her chest) all add an element of seduction. In conjunction with the square bottle (an update from the more rectangular bottle of the original scent) that bears a bow on top, one could read the image as presenting Portman as a sexual gift for the male gaze. Bearing in mind Demachy’s comments about the olfactorial message of the fragrance, the pastel colors are a signifier and the aura of gentleness the signified. Similarly, the delicate material of the dress and Portman’s introverted pose denote a certain type of vulnerability. The bow and classic cut of the ballgown, as well as Portman’s retro make-up look (all three reminiscent of 1950s style markers) connote classic femininity. On the other hand, the slightly unruly hair and

unzipped bodice of Portman’s dress are subtly seductive and allude to a more relaxed female image that isn’t primed to perfection or posing rigidly like a mannequin. Portman’s almost slouchy posture and ruffled dress present a disruption of the symmetrical and highly organized background. The Miss Dior we see here is has an underlying, anti-bourgeoisie tone to her because of these ‘wild’ aspects. This laidback attitude, as well as the more modern codes of the fashion design and styling depicted in this advertising image, break with what could otherwise be a stiffly traditional aesthetic and create a hyperreality of an educated, upper class woman, who is liberated but at the same time demure and well-mannered. The fact that Portman herself is a Harvardeducated, well-spoken and successful, Academy Award-winning actress further bestow the fragrance with these properties. Her sexuality is not overt but seductively subtle. Overall, we see here a contemporary image rooted in past ideals.

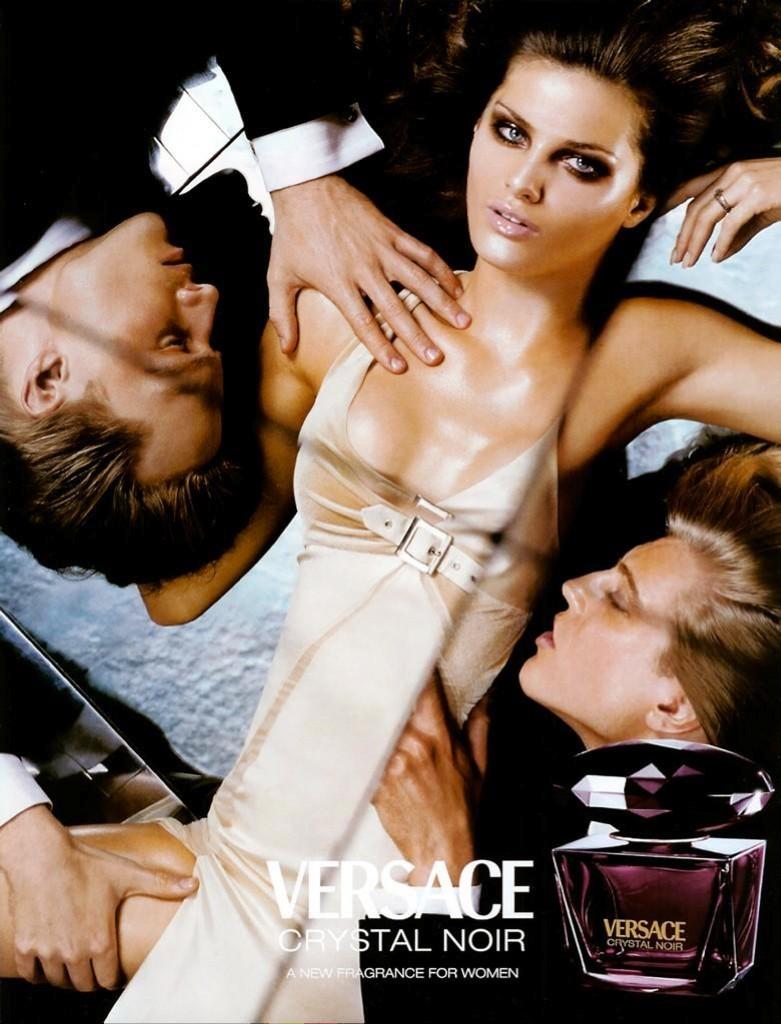

A Study of Female Sexuality: Versace Crystal Noir vs. Estee Lauder Beautiful

Illustration 3

The modern fashion system “commodifies the body and sexuality. In other words, the fashion obsession with the sexuality of the body is articulated through particular commodities which are constructed as sexual” (Entwistle 2015: 187)

As the following two examples will show from two opposite angles, the commodification of the body and sexuality is not only limited to fashion but also applies to fragrance. The above image is an advertisement for Versace Crystal Noir, a floriental women’s eau de parfum launched in 2004 and created by perfumer Antoine Lie. The house of Versace was founded in 1978 in Milan by Gianni Versace, with his sister Donatella taking over creative direction after his death in 1997. The house is known for its daringly sexy evening wear and glamorous daywear designs (Berg).

Versace Crystal Noir contains head notes of ginger, cardamom and pepper, a heart note of African orange flower, gardenia, peony and coconut, and base notes of musk, sandalwood and amber (Fragrantica). Versace describes the Crystal Noir woman as follows:

She has presence. She walks with her head held high, and she has that certain smile. She has an innate ability to always be sexy and confident. She has a sure sense of fashion and elegance, and she loves the lavishness, eccentricity and glamour of haute couture spirit. She’s a Versace woman. She wants a sumptuous fragrance, the olfactory equivalent of a long train on a fabulous evening dress. It must be a “red carpet” fragrance, multi-faceted like a diamond. It is a unique fragrance inspired by the virtuosity and creativity of Versace and its modern interpretation of luxury (Versace).

The accompanying ad campaign was photographed by Steven Meisel and features model Isabeli Fontana (Illustration 3). She is wearing a nude colored, halter dress with a thigh-high slit, made of what appears to be silk and velvet fabrics. The dress has a squareshaped belt buckle in the middle of the chest, which draws attention to the already enhanced (either through surgery or a push up bra) breasts. Fontana’s chest area is made to appear dewy through the use of oil or sweaty from physical activity. Her makeup has an equal sheen to it. The look consists of a nude glossy lip and dark brown smokey eye, which is both smudged out and topped off with a gloss on the lids. Fontana is lying on her back with her

dark brown hair in voluminous waves spread out on the silver colored surface she is lying on.

There are two male models dressed in black and white tuxedos in the image as well, the first on the left side of Fontana, lying upside down and touching her shoulder and upper chest area with one hand and grabbing her inner thigh with the other, and the second to her right, with his left hand underneath the right side of her ribcage. Both men are shot in profile and are gazing up at Fontana, their mouths slightly open. There are two blurred diagonal lines in the image, one running vertically and the other diagonally. This could be a window through which the viewer is looking, creating a sense of voyeurism.

In the bottom part of the image is the text “Versace, Crystal Noir, A New Fragrance for Women” in a Helvetica-style font. Next to this, in the right-hand corner is a bottle of perfume. Versace states “The jewel-like bottle is inspired by the facets of a diamond. Made of garnet glass, it is understated yet sumptuous” (Versace). The garnet bottle bears the name and logo in the same font, except in gold instead of white. This color choice echoes the luxurious feel of the diamond-inspired bottle. Therefore wealth is signified through the packaging of the product.

The notes of the fragrance can be interpreted as follows: the top notes of ginger, cardamom and pepper all fall into the spice category. Spices are used to add dimension and often heat to something, so employing these products olfactory can be seen as supercharging the fragrance and making it hot (which is repeated in the ‘hot’ woman in the form of Isabela Fontini). African orange flower and coconut are two ingredients that comprise the heart note of the scent. Both are ‘exotic’ ingredients connoting the glamor of traveling. Finally, the sandalwood and amber in the base note of the fragrance add a warm and seductive finish to the fragrance.

Versace interprets the myth of the seductive woman in this advertisement, and the uncompromisingly glamorous lifestyle the brand is known for The

notions of glamor are echoed in the jewel color and design of the fragrance bottle as well as the evening wear styles worn by all three models. The men’s gazes (a literal interpretation of the male gaze), groping hands and open mouths connote their lust for this female figure, which builds a carnal contrast to their formally civilized, covered up clothing. The fact that the female model is the main focus of the image sells the consumer the hyperreality that this an empowered, presumably heterosexual, woman who is so confident in her looks and sexuality that the opposite sex is unable to resist her. Her gaze is not directed towards her male counterparts but instead at the viewer, indicating that she is independent. Her dewy appearance indicates physical exertion, in this context sex, or simply a body which is maintained not only through diet and exercise, as denoted by her body shape and tone, but also a make-up regime including highlighting products and body oils.

However, the image can also be read as objectifying the female body, not through self-objectification, but both the external and internalized male gaze. The men grabbing her various body parts, while she is statically placed on the table, brings up the question of which sex is being empowered here. On one hand it could be Fontana, but on the other hand, she could simple be fulfilling a hetero-performative function of looking beautiful, not for herself, but in order to evoke the desire of men. Her erotic appeal is heightened through the emphasis of her bust, the slightly ajar legs, full glossy lips and seductive eyes. The nude color of her tight dress denotes a nearly naked look. The dark color of the fragrance bottle, with noir, the French word for black, printed on it and her evening wear clothing connote that this is a woman of the night, a glamorous vamp. Her evening dress and wellmaintained appearance can be seen as further signifiers of wealth and glamor.

Overall, the codes of the Versace fashion house are represented in this image of an openly sexual, unabashedly feminine woman. The advertisement also

brings up the problematic contradictions of the postfeminist generation, where the boundaries between sexually empowered and sexually objectified are blurry.

4

The campaign imagery for Estee Lauder Beautiful eau de parfum, photographed by Mario Testino and featuring model Anja Rubik presents a completely different version of female sexuality (Illustration 4) Estee Lauder founded the company in 1946 with only four skincare products and with “a simple premise: that every woman can be beautiful” (Lauder). The Beautiful fragrance was first launched in 1985, but this campaign debuted in November 2006. The fragrance has head notes of rose, mandarin, lily, tuberose and marigold, a heart note of orange flower, muguet, jasmine and ylang-ylang, and base notes of sandalwood, vetiver and amber. Estee Lauder describes the fragrance as follows:

Estée Lauder's vision, carried out by Evelyn Lauder, was to create a fragrance that made every woman feel she was the most beautiful woman in the room. Ever romantic, Beautiful is represented by a bride to symbolize a woman at her most feminine, romantic and beautiful (Estee Lauder).

The corresponding advertisement features Rubik on her wedding day, wearing a white presumably strapless wedding dress and a long veil with floral embroidery trimming. She is sitting down with her legs crossed and a bouquet in her lap while smiling and looking straight

Illustration

on at the viewer. Her right elbow is propped up to expose her wedding ring. Her long blonde hair is parted in the middle and styled in a natural, slightly wavy style while her makeup consists of a thin application of black liquid eyeliner and a neutral lipstick. She is sitting in the left corner of the image and behind her we see her husband in a classic black and white tuxedo, leaning forward with a gentle smile on his face. The background consists of an antique style stone balcony decorated with white flowers and greenery. The right side of the image reads “This is your moment to be beautiful.” underneath of which is the fragrance name, Beautiful, the Estee Lauder logo and website address and a bottle of the fragrance. It is worth noting that this advertisement is the only example with a tagline, presumably because this is a longstanding product as opposed to the newly launched examples of the other advertisements. The packaging is a long oval shaped glass container with a golden colored fragrance inside and a bronze bottle cap. The name and logo are written in white on the bottle.

While the typography used is surprisingly gender neutral by not using any rounded or cursive font, almost every other signifier in the image, from the Rubik’s long, flowing hair to her wedding dress to the white floral arrangements, indicates traditional femininity. The white wedding dress and doting husband-to-be in the background connote heteroperformativity and a life of domesticity. “This is your moment to be beautiful” connotes the pressure for every woman to look her utmost perfect on her wedding day, or as it is popularly known to most women, ‘their day to shine’. Hence all the elements of the image are signifiers for a bride’s wedding day, while what is signified is society’s expectations of a bride on her wedding. The white roses in Rubik’s bouquet are a signifier for eternal love but also echo the floral-heavy composition of the fragrance. Overall this image is selling the myth for brides to be that if they wear Estee Lauder Beautiful eau de parfum on their wedding day, they will not only be the most beautiful they can be, but also have a lifetime of peaceful marriage, financial

security (denoted by the gold perfume bottle and large wedding ring) and happiness. Not only is the Estee Lauder Beautiful perfume a longstanding tradition, but so is the concept of heterosexual, monogamous marriage. By sitting down and having her husband lean in toward her from behind, Rubik’s body language signifies a domesticated housewife who is inferior to her husband and his orders. Just as her husband is behind her as a support and leaning in to whisper something to her on their wedding day, so too will their marriage be marked by him giving her orders. However, her gaze towards the viewer as opposed to her husband could indicate that she is indifferent to these orders and independent, or that in fact the gaze of others on her wedding day and being the center of the spectacle are more important than her solidified romantic relationship with her husband. In this sense, her smile can be interpreted as mischievous. A vital text on the discussion of weddings and domesticity is Chrys Ingraham’s White Weddings: Romancing Heterosexuality in Popular Culture (1993). Ingraham (1993) brings up the concept of the heterosexual imaginary, “a belief system that relies on romantic and sacred notions of heterosexuality in order to create and maintain the illusion of well-being” (16) which is performed through the white wedding. In the Beautiful advertisement, the romantic notion of heterosexuality is reinforced through the married couple, and well-being is indicated through the bride’s large wedding ring, fancy dress and the idyllic setup of the wedding location. Furthermore, “patriarchal heterosexuality makes use of the ideology of romantic love in the interests of male dominance and capitalism. Creating the illusion of plentitude and fullness, the ideology of romantic love produces a belief that sexual objectification and subordination is both natural and justified” (Ingraham, 1999: 86).

Applying this statement to the image above, not only is the male the dominant partner in the relationship but also the one who is presumably offering his bride financial stability, indicated through the above average sized wedding ring which the groom is responsible for

buying. Of course one could also argue that the bride could be just as financially well off as her husband, however by being seated she becomes an object to be admired, i.e. a trophy wife, indicating less independence and more financial dependence. While as previously mentioned the bride’s mischievous gaze towards the viewer can be interpreted as a subversion of these norms, the other elements of the image build a strong case for Ingraham’s theories on heteroperformativity of the wedding spectacle.

This and the Versace campaign provide two very different representations of female sexuality. The latter shows an overtly sexual woman who is not afraid of being polygamous or displaying her body in provocative clothing. She is relying on the men around her for sexual pleasure, not romance. The Estee Lauder woman is far more conservative. She is monogamous and getting married at a young age to a presumably longtime partner. Therefore the fragrance she wears is a more innocent, floral counterpart to the sensual, animalic notes of the Versace fragrance. Nonetheless, both still conform to a certain extent to the expectations of a patriarchal, male-dominated society. The Versace woman adheres to the notion of self-surveillance and physical upkeep, while the Estee Lauder woman can be seen as living out heteronormative expectations. The final example of this chapter will provide a more provocative case of subverting societal norms.

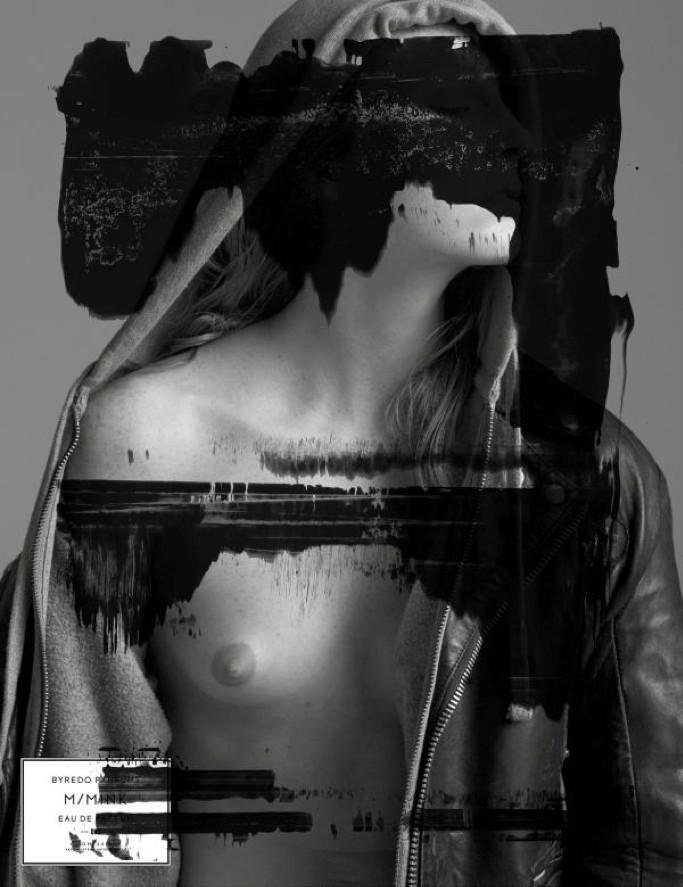

Unisex Subversion: Byredo M/Mink

5

M/Mink is a woody aldehydic unisex perfume launched in 2010. It is a collaborative effort between the perfume brand Byredo and the creative agency M/M (Paris). Byredo is a

Sweden-based independent company founded in 2006 by Ben Gorham. The story behind the brand’s founding was explained as follows: “With no formal training in the field, Gorham, a 31-year old, sought out the services of world renowned perfumers Olivia Giacobetti and Jerome Epinette, explaining his olfactory desires and letting them create the compositions” (Byredo). M/Mink was inspired by

A block of solid ink purchased in Asia, a photograph showing a Japanese master practicing his daily calligraphy, and a large utopian formula that [M/M (Paris) co-founder] Mathias [Augustyniak] drew on Korean traditional paper (Byredo).

The scent was created by Epinette and contains a head note of adoxal and aromatic notes, a heart note of honey, cloves, oliban and animal notes, and a base note of patchouli leaf, a leathery note, patchouli and amber (Byredo). Overall this fragrance is highly

Illustration

conceptual compared to the aforementioned fragrances, and even the way this scent is marketed underlinea this. As opposed to photographing a campaign for the product, M/M (Paris) reworked existing photographs by Inez van Lamsweerde & Vinoodh Matadin. M/M (Paris) founders Michaël Amzalag and Mathias Augustyniak explain their decision as follows:

The common rule in the perfume industry is to create a perfume and then produce an image to promote it. It is for us evidence that a scent should be inspired by an image and not the opposite (Ads for Adults).

This is the first instance of the creation of the fragrance subverting typical procedures of the fragrance industry. As Bubartz (2009) notes, “Non-mainstream examples also exist that challenge the dominant practices of marketing and branding. Niche producers of perfumes have a longstanding tradition in which a scent, in contrast to a brand, is the center of attention” (448). So minimal is the brand name here that it is literally covered in ink. Another point of subversion is the female image that is being presented (Illustration 5). A stereotypical women’s fragrance advertising campaign would include traditional signifiers of femininity such as an elegant, full-skirted dress or a female subject with an updo gazing gently at the viewer. Instead, here we have a black and white image of a woman wearing a hoodie and leather jacket over her free-flowing long hair, which is resting behind one shoulder and resting in front of the other, connoting an asymmetry and relaxed, natural styling. Both jackets are unzipped, exposing her left shoulder, chest and upper stomach. In the left lower corner of the image is a rectangular shaped black and white label, which reads “Byredo, M/M, Eau de” in an Arial-esque type font with slightly rounded edges. The rest of the label, as well as the middle and upper portion of the image, is obscured by horizontal black ink splotches which cover almost the entire face of the model (except for her jawline). The model’s face is turned to the right, away from the viewer, only showing the left side of her face.

The black, white and grey color palette denotes the Asian ink and Japanese calligraphy inspiration behind the scent, as well as the past, i.e. a time when there was no color photography despite this being a recently launched product. The third inspiration, a utopian formula written by a French man (Augustyniak was born in the town of Cavaillon) on traditional Korean paper exemplifies the East-meets-West aspect of this product, which incorporates time-honored methods into a modern, commercial product. This ties into the idea of the past and future being combined in the present as discussed with the Marc Jacobs Oh, Lola! scent, but with a dramatically different result. The use of ink covering both the image and the logo in the left-hand corner connotes a chaotic, broken and distorted feeling. The covered logo could also signify that commercial success is less important for this niche brand, for rather than pushing its own name or that of the product, the artistic message gains priority. Furthermore, a black and white palette, as well as the type font connotes a gender neutral message. The typography is straight but also has curved letter endings, striking a balance between a rigid and soft typeface.

Due to a complete lack of depicting the actual product, we are here faced with the concept of evoking a scent completely through color, image content and typography. These become all the more important in translating the message of the fragrance to the viewer. It also creates a mystery around the packaged product, which in turn creates a desire in the consumer to see the actual physical perfume. There is also a sense of mystery in the advertisement through its model whose eyes are obscured through blots of ink. There is an interesting ‘lack’ in comparison to the stereotypical advertisement: not only a lack of showing the actual product but also a certain lack of human connection between the ad and the viewer. Through this disconnect, the lack of color, and the unisex, casual garments, the image connotes a cool, almost cold, aloofness towards its viewer, whilst also perpetuating the myth that this niche, conceptual product is only tailored towards a certain type of intellectual

individual who craves a non-traditional product.

In his book The Erotic History of Advertising, Tom Reichert states:

“Sexual content in fragrance advertising is manifest in the usual ways as models showing skin — chest and breasts, open shirts, tight-fitting clothing— and as dalliances involving touching, kissing, embracing, and voyeurism. These outward forms of sexual content are often woven into the explicit and implicit sexual promises discussed in Chapter 1: promises to make the wearer more sexually attractive, more likely to engage in sexual behavior, or simply “feel” more sexy for one’s own enjoyment” (Reichert 2003, 242).