EDITORIAL

Photography is the most cerebral of all the arts, considering that aesthetic decisions require undivided attention and technical knowledge.

RUBENS FERNANDES JUNIOR

On Fogueira Doce

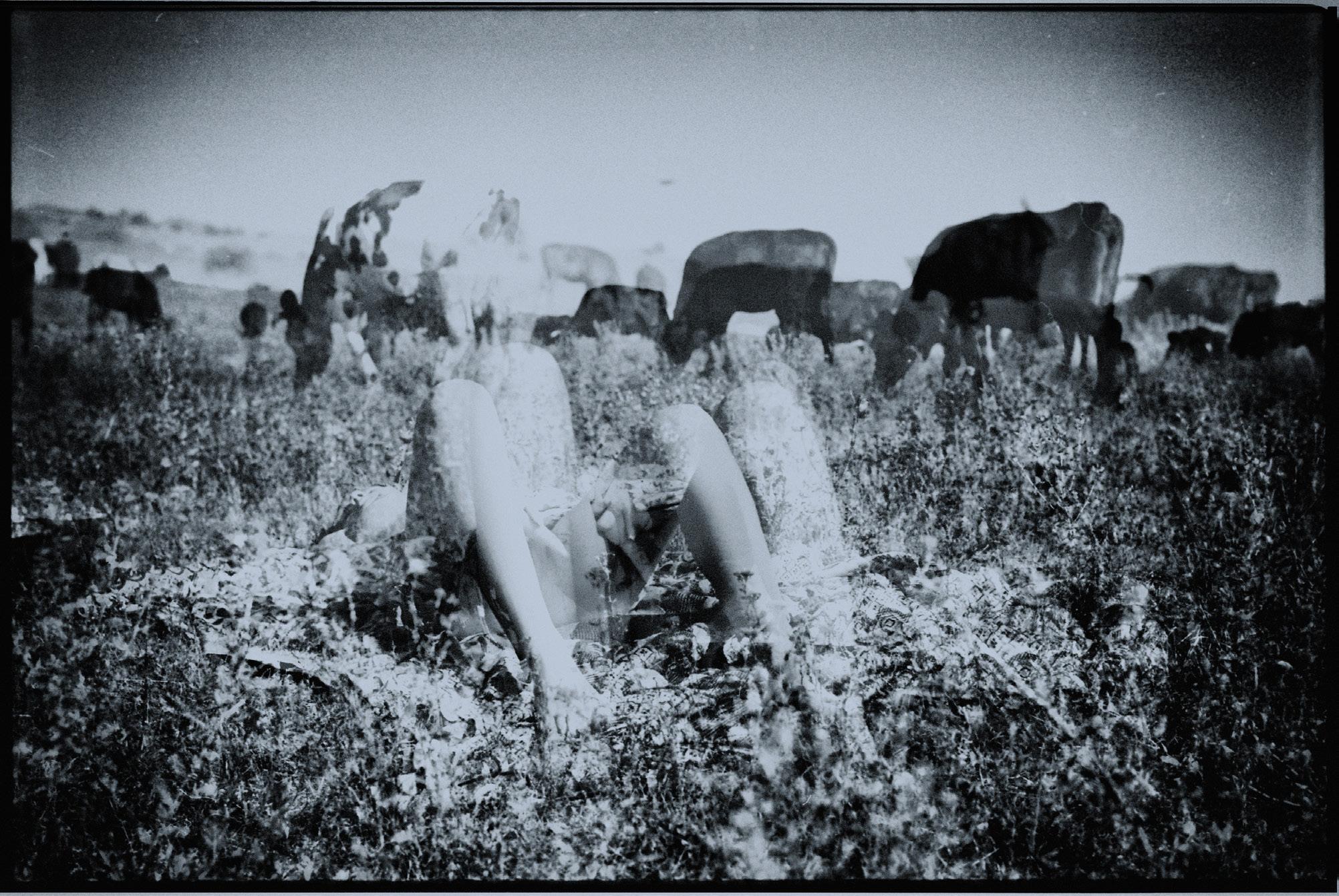

The year is 1991: the Soviet Union (USSR) officially disintegrates and the new 15 independent republics, each in their own way, tread their new paths and narratives. However, it continues to connect them to a past of joint sacrifices during World War II, sacrifices that cost more than 20 million human lives, thus subduing the Nazi beast. An authentically monumental achievement. In order to recall the bravery and martyrdom of the Great Patriotic War – Velikaya Oteschestvenaya Voyna – the designation of World War II in the USSR, which lasted from 1941 to 1945; colossal monuments of women warriors are built throughout the Soviet space; reminiscences of the rodina-mat or motherland. Welcome to Alexander’s Pamyatny Project.

Alexander Iwenicki Manela

Alexander Iwenicki Manela

Alexis Edwards, an Andalusian photographer, works in different countries. His photographs, blunt and surrealist, achieve an unsettling juxtaposition of several stories, made from the composition of images. His projects bring the desire to discover the world beyond the surroundings of his country, going beyond the borders of the photo in order to become theatrical pieces.

Alexis Edwards

Alexis Edwards

The photos of Eva Perón, or Evita, whose authorship is due to the pioneer of contemporary photography Annemarie Heinrich, born in 1912, in Germany, and nationalized as an Argentinian after immigrating with her family in 1926. Selftaught, she set up a “darkroom” indoors and, being taught by her uncle, she fell in love with the art of photography. Her portraits reflected the figure of the author herself, containing objects, novels, scripts and even scores, but also female nudity, something that could not be displayed at the time. Evita, starting her career, decided to hire the artist for a photo shoot, and the photos were selected by several editors for illustrations on covers, notes and reports in the main magazines of Buenos Aires. The photographer passed away in 2005, and her work can be seen at the National Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Modern Art of Buenos Aires, the National Museum of Cinema and the World Museum of Tango.

Annemarie Heinrich

Annemarie Heinrich

Gabriel Chaim was born in 1982 in Belém do Pará (Brazil) and has been working for 10 years, always portraying images of conflicts. His photographs travel through Syria, his first contact with the war, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, Armenia and Ukraine. One of his last works, promoted in the exhibition “Devolve Ouro” (Return the Gold) in 2022, is a collection of photographs in a Yanomami indigenous land on the border between the states of Roraima and Amazonas, about the action of the Army and the Federal Police against illegal mining in the area, a kind of conflict that is different than the ones Brazilians are used to witnessing.

Gabriel Chaim’s work is to bring up the social problems of wars and humanitarian crises, now immortalized in his book “Em Desconstrução: As Guerras de Gabriel Chaim” (In Deconstruction: Gabriel Chaim’s Wars), by Editora Afluente, where he documents, in passing through several fronts, the current time on the front lines of the fight, getting us inside these chapters that must be remembered over and over again as events that should never have happened.

Gabriel Chaim

Gabriel Chaim

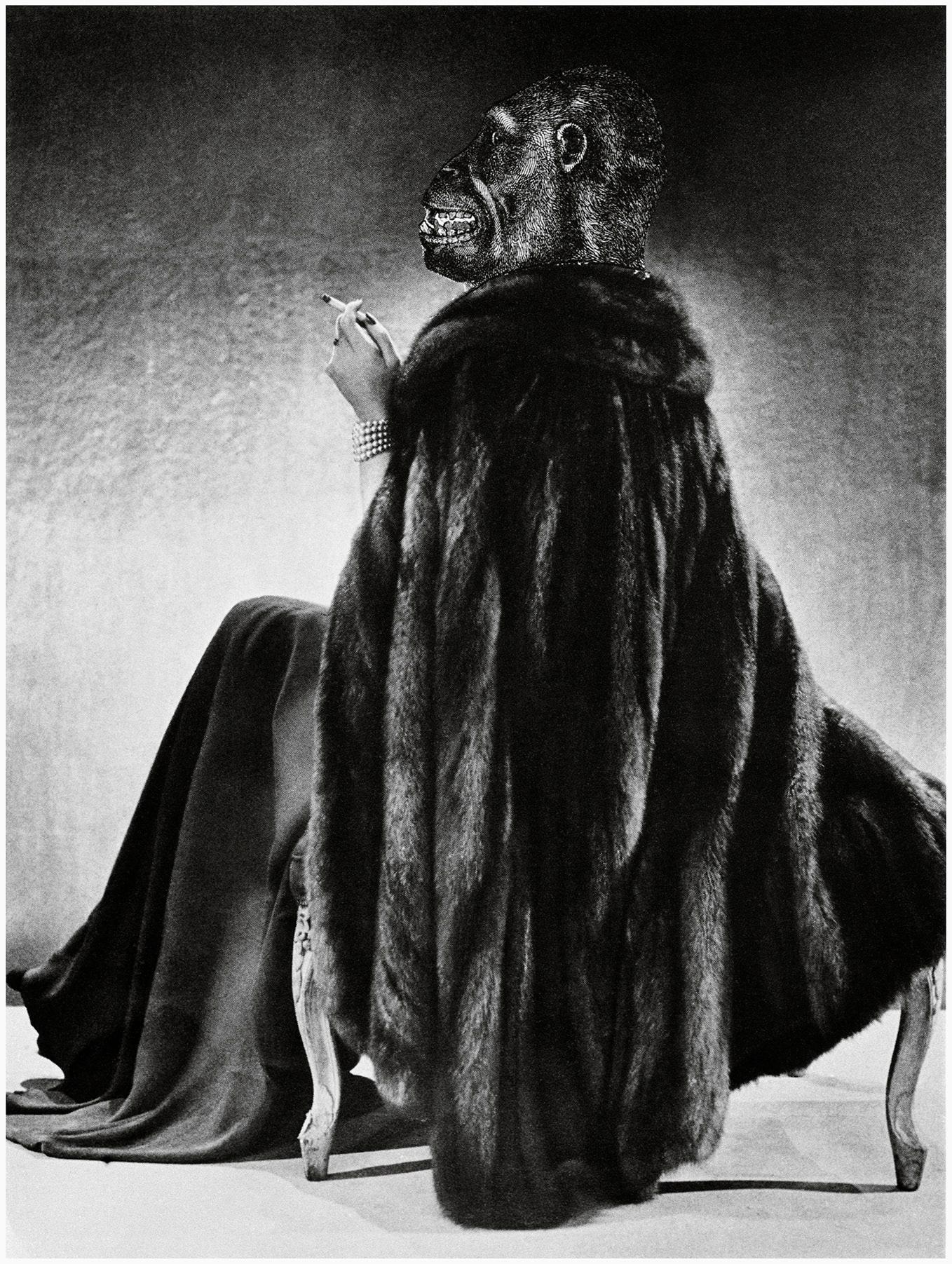

A Pintura em Pânico (Painting in Panic) is a sui generis work in the history of Brazilian art: the series of photomontages made by Alagoan artist Jorge de Lima between the 1930s and 1940s is a pioneer of modern photography in Brazil with its experimentalism in tune with the practices of the European vanguards. Best known as the writer of “Invenção de Orfeu” (The Invention of Orpheus), Jorge de Lima (1893-1953) was a researcher of multiple languages and pursued poetry in the interstices between image and word, far beyond the specificities of the means. Influenced by the book “La Fémme 100 Têtes”, by Max Ernst, he begins an investigation of the possibilities of deconstruction/reconstruction of images extracted from a very eclectic repertoire of publications, having as matrix a mythical, Orphic worldview, populated by enigmatic beings and metaphysical adventures. His unusual perspectives of illusionist universes create non-linear narratives of an epic-lyrical character, causing a twist in our perception, which oscillates between the credible and the unreal, the commonplace and the magical. This set of 11 photomontages, without titles, are reproductions of the only remnants of the “originals” (photographs of the collages) that survived, kept in the archives of Mário de Andrade. Thanks to his recognized effort to preserve the Brazilian cultural memory, these vintage prints could be preserved in the Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros Collection (IEB-USP).

SIMONE RODRIGUES Curator

Jorge de Lima

Jorge de Lima

Lamberto Scipioni is a Roman photographer who has lived in Brazil since 1978. As a collaborator of the Louvre Museum, he photographed its classic marble sculptures. The museum hired him to set up a studio in the technical reserve, recording this material that Carcara now publishes. Lamberto’s works are both about Brazil and Europe, but it is this triangulation between Brazil, Italy and France that draws the most attention.

Levi Tapuia, a 25-year-old indigenous young man, started photographing teenagers on his cell phone and, encouraged by many people around him, decided to study photography. He tells the story of his people through their own eyes, a complete revolution that becomes the main line of defence of many territories by showing what is happening to them in Brazil. His work is, in short, the dissemination of the struggle of his people, the appreciation and strengthening of his culture, so that new generations can learn and also take part in the struggle for their rights and for the planet.

Levi Tapuia

Levi Tapuia

Being a mother is to crumble. The baby brings along, into the womb, the whole universe. Infinity takes over, then rips and tears everything up to accomodate itself. In this disruption, the body remains – obedient, devoted, soaked in pleasure, asleep within the baby´s merciless love. The soul leaves, expands, reaches unimaginable places, unimaginable times. Your call, my love, did not reach the chasms, nor the stars, where I had gone. I can picture your loneliness in the face of my absent presence. The longing that filled you had no place in me. The camera was you way of being there. Your images were screams that tried to protect the frailness of our life together. The cal lis brutal. For the mother, that call will always be premature. One won´t come back in a mere awakening. One won´t come back. I´ve come back, as a diferente person, from my implosion. You, from your exile.

HELENA RIOS On Fogueira Doce

Renato Soares, a photographer and specialist in Brazilian indigenous culture, began his career in 1986, moved by contact, since childhood, with indigenous people who live in remote areas of Amazonas. His works, which aim to give a voice and face to the indigenous cause, have already been exhibited in MASP (Sao Paulo’s Art Museum) and in itinerant exhibitions, reaching Paris in a collective exhibition at the Palais de la Découverte, a museum and French cultural centre. He is currently dedicated to the project Ameríndios do Brasil (Amerindians of Brazil), which seeks to rescue, through photos, the best of Brazil’s ancestral culture, thus creating a large Brazilian ethnophotographic collection.

In his book “Invisible Cities”, the Italian-Cuban writer Italo Calvino (1923-1985) wrote: “It is not known whether Kublai Khan believes everything Marco Polo says when he describes the cities he visited on his diplomatic missions, but the Emperor of the Tartars certainly continues to listen to the young Venetian with greater curiosity and attention than to any other of his envoys or explorers”. Marco Polo describes the beauty of imaginary cities, almost all named after women.

But when we talk about Rome, whose anagram in Portuguese is “love”, we know that this city full of mysteries, which manages to make itself loved by everyone who knows it, exists and its ancient culture is before our eyes when we decide to unveil it.

Immortalized by cinema, literature, music, the city of Rome inhabits the imagination of mankind. With its narrow streets, its cheerful restaurants, its churches, its monuments, it is considered by many an open-air museum, like by filmmakers Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini and even Woody Allen, just to name a few.

Its foundation is legendary and recounted by the philosopher Plutarch and the poets Ovid and Virgil. A story of revenge, fights and deaths, as in all epic poems.

Rome would have been founded by the twins Romulus and Remus, nursed by a she-wolf and then raised by peasants. But Rome was founded by seven villages of peasants coming together. The seven hills of Rome. Its date of birth, known as the Christmas of Rome, was fixed at 21 April 753 BC. On April 21, 2023, Rome turned 2776 years old.

Now, Carcara Photo Art presents a rare collection of colourized postcards from the beginning of the 20th century, which portray some aspects of Rome that remained in time and we still find them in the eternal city: the Colosseum, Piazza del Popolo, the beautiful Piazza del People, the imperial forums, its beautiful views of the Tiber, or Tevere, just to name a few examples. The postcard was created at the end of the 19th century.

Its invention also has numerous different versions. There are more than one version of the history of the invention of postcards. The inventor may have been the American H. L. Lipman who, with J. P. Charlton, patented the so-called “Lipman’s Postal Card” in 1862. Another version suggests that the director of the Post Office of the North German Confederation, Heinrich Von Stephan, would have sold the idea at the GermanAustrian Postal Conference in 1865.

The interesting thing is that postcards, invented to be an alternative to letters, by bringing images ended up creating imaginary cities in us. They began to be collected, travelled the world and we don’t always know how they ended up in our drawers, in our albums. Having a collection of postcards is like listening to Marco Polo’s narratives to Kublai Kan. This issue also helps us to review and think about a city that has hardly changed in its almost 3000 years of history. That’s why it will be eternal!

SIMONETTA PERSICHETTI

Rome, eternal city

Sebastião is a judge, a minister of Brazil’s Superior Justice Court and a photographer. In this interview to Paulo Marcos de Mendonça Lima, from Carcara, he talks about his beginning in photography, his perceptions about incarceration and his book Translúcida, the result of his visits to the Pinheiros II Preventive Detention Center, in the city of São Paulo. After an invitation from the Institute to talk to transsexual prisoners, Sebastião decided to return to the place to photograph them, so that the images and the experience would bring a feeling of dignity both to the detainees and to those who saw the result. In addition to the photos, Sebastião’s book has the collaboration of several personalities, such as minister Luís Roberto Barroso and congresswoman Erika Hilton.

PMML: Sebastião, how did you end up in photography? It is not very common to see a minister who is also a photographer.

Sebastião: There was no “oh, I started taking pictures”... It is relatively recent, about six, seven years ago... It started with me taking pictures while traveling. I had a Nikon 1, which is tiny, white... It was the first camera I had bought and I liked it because you could choose the color of the photograph, so it came out all black and white with the blue sea. This nonsense impressed me at the time, but then I ended up getting a better camera from my wife and I started to really like photography. Today I cannot live without a camera, there is not the slightest possibility of me traveling without one. Then my wife gave me a Leica, so if I go to a rougher place I use the Nikon, if I go to a more civilized place I can go with a Leica. Then I bought a crappy Nikon that takes pictures in water and a simpler Panasonic because when I go to Rio —the last time I took a Nikon my wife almost hit me: “Are you crazy, are you asking to be robbed?! ”, so I bought a tiny Panasonic with a Leica lens, which fits in my pocket, and when I see something interesting I go and photograph it.

PMML: It’s more discreet.

Sebastião: Indeed. In fact, I’ve been in photography

for about five, six years, and the pandemic ended up helping a lot. When everything stopped and the places were deserted, I would go around taking pictures. I woke up at 4 am with insomnia and went to the center of Brasilia to take a picture. Hiking with the machine, for example. I don’t like hiking, but I started doing it because of photography. Today it really is my favorite pastime, I have it in my hand at any time.

PMML: Is Translúcida your first book?

Sebastião: Yes. I have, like, I have a book, actually a little book, even curated by Juan Esteves, but there are only fifty copies. Last year I decided to do something nice for the people at home precisely because of the support they give. We selected about thirty photos and I made a bound book, cute, but like... just for the family. Now, a book that has photography as its motif, this is the first.

Carlo: It will be launched on the 28th, is that it?

Sebastião: Yes, on June 22nd.

PMML: In Brasília?

Sebastião: In Brasília. There will be a seminar here at the Court on the problem of inclusion and at the end there will be several lectures. I’m going to participate in a table with Nany People and at the end, at 7 pm, there will be the book launch.

Carlo: Will it be open, Minister?

Sebastião: Yes.

PMML: Translucida has an impressive density that comes about in several ways. It is not always that one sees a thorny subject, which society does not want to look at and which involves the periphery, not just the geographic one, but the social one. Society has always found it difficult to look at these peripheral issues and tries to push them further and further away. And it’s not every time that we see a book that

has several ways of entries, several ways of talking about this subject, and that pivot around photography. What motivated you initially, I imagine, was to transpose this difficult subject to your photos with the support of texts, poems, illustrations by Laerte… Today I saw on Instagram something about the Gay Pride Parade here in São Paulo, which is the largest in the world - the estimate is four million people - and there were two people who stood out in that parade who are in the book: the minister Silvio Almeida and congresswoman Érika Hilton.

Sebastião: There is Sara Wagner too.

PMML: I didn’t see Sara Wagner. Our conversation is about photography, but how did you come up with the idea of doing this interaction? Because there are some poetic texts, there is the illustration of Laerte, which is a very free thing, there are interviews and there are academic texts, with all the bibliography and references, a very unusual mix, and what is most interesting here for our conversation is that everything is around photography, the trigger for all of this was photography. In your introductory text you say that it’s not much about text, about words, that it’s more about image and photography helps you to communicate in that sense. Which is a contradiction, since a minister writes and speaks a lot. I doubt you’ll get there at the Superior Justice Court and say “my argument is as follows, and then show a picture”.

Sebastião: I am one of those who speak and write little. I try to be objective because, due to my age, I no longer have the patience to read and listen a lot, it’s tiresome. But let me explain. I visited a prison in São Paulo about five years ago. There is an Institute for the Defense of the Right to Defense which works on the study of criminal law and they talk to the prisoners. They asked me if I could go there one day. I spent a whole morning talking to the prisoners and was very impressed. After a while, I saw Nana Moraes’ book. The book is a poem. She works on photos that show precisely this situation of abandonment of the imprisoned in general. And that gave me a start. I said: “Guys,

if Nana, who is not a specialist, did something like that, I think I could do it”. I got back in touch with the people in São Paulo, who had arranged my first visit and I went last year. It was very interesting because I visited, I went inside the cell, I talked to the prisoners, I asked if they agreed to do this project, for me to photograph, for me to spend a morning there… And they agreed, and I said “look, I will only photograph those who volunteer, I will not force anyone to take a photograph”. They agreed, I asked permission from the Security Department, we set a new date and I spent a whole morning photographing thirty, forty prisoners. You will see that there are posed photos and candid photos. At a certain point I started circulating, talking, and photographing. In fact, the trigger for the book was the work of Nana Moraes. It’s not a photography book, I used it to provoke the subject, to provoke debate. In this book there is an artist, a military man, a lawyer, a prosecutor, a minister, a judge, a doctor, a reporter, people from different backgrounds, from the south, north, southeast, northeast, trying to provide as much diversity as possible. And I left people free, each one did what they wanted, wrote what they wanted. Each one chose a photo and produced what they wanted: short stories, technical texts, poetry. There is something that I find very interesting, which is a trial of a trans woman, the lawyers asked for authorization and reported the whole context. It has a hell of a diversity and that was exactly the idea. I know this topic is very heavy and I know I will be beaten. Some trials I went to about three, four months ago, I blocked a police investigation on a girl who had had an abortion and had been reported, that is, the doctor who attended her at the hospital reported her and started an investigation, and we ended up locking it, I

was the rapporteur of the process because I understood that the doctor, in view of secrecy, could not report this fact, could not provoke this investigation. This is what we call “illicit evidence”. His testimony had no validity and since it all started with him, it was worthless. But then what happened was that I was attacked in Congress; some went to the tribune to criticize me. Now I keep imagining a book of this content in the complicated moment we are living in. I believe it’s going to be a hell of a fight, but then I’m carrying a burden, and I’ll be very honest, which is being a minister. I’m going to launch the book here inside the Court, which is something that gives strength, which shows that the Court is supporting me in this book. Minister Maria Thereza, president of the Court, has a wonderful vision. She has already done a seminar on indigenous people, she has done one on gender judgment, and now she is doing this book on inclusion, taboo topics, and she is giving space to talk about it here at the Superior Court. I want to use the natural projection that it will have because I am a minister, as one more reason for us to debate the subject, and then you have this diversity. So there are technical texts, short stories, stories, and it’s a very interesting thing. Valois, who is a minister of the Execution Court in Amazonas, left Manaus and went to São Paulo to talk to the prisoners to write the text that is in the book. Judge Simone Schreiber, from Rio de Janeiro, did the same thing and that gives the book a density and shows people’s connection with it. These are not formal texts “Oh, I’ll write a little text here and that’s it, that’s it”. I think it had a very big emotional charge on the vast majority of people who made all this content.

Carlo: Will the photos be on display at launch?

Sebastião: I don’t know exactly how it’s going to be, but I believe some pictures will be on display. We’re going to take advantage of the fact that it’s June, that it doesn’t rain in Brasília, and we’re going to do it in an open space in front of the Court’s auditorium. A more inclusive launch. One does not have to enter the Court, it is less oppressive, more open, something more

relaxed, more cheerful, more comfortable for someone who is not from the legal environment.

PMML: Undoubtedly. By the way, this is another important point, and that your photos convey, the photos and the book have a lightness, despite the fact that Brazil is the country where the most LGBTQIA+ people are killed.

Sebastião: But then I think that’s the strength of the book, right? I remember that congresswoman Érika Hilton even wrote to me saying that she was very busy, very busy, and it was difficult for her to prepare the text, but she wrote me, by coincidence, one or two days after that congressman from Minas, that Nikolas, or whatever, made that joke [about trans people] in Congress, putting on a wig. Then I said to her, “Madame, I understand perfectly, I know that life is hectic, but I think we are at a point where this matter needs to be seriously discussed. People without knowledge cannot keep talking about it and you, as you are a leader, your participation in the book gains greater weight”, so she ended up agreeing and wrote a wonderful text.

PMML: We talked about the lightness of the photos and the great diversity – there is Minister Silvio, who is black, Congresswoman Érika, who is a trans woman, the judge from Amazonas - there are all kinds of texts and people and that, at the same time that gives a lightness and a diversity and a depth, it will also be the reason, as you can see, for many discussions and seminars. You can pull multiple lines from it.

Sebastião: Exactly. I invited Nana Moraes to participate in a photography workshop at the Talavera Bruce women’s prison with the inmates and then make an exhibition with the photos.

PMML: Excellent. Here’s an invitation to

exhibit this work within the FotoRio Festival program.

Sebastião: It will be really cool if we manage to do this. I’ve seen this kind of work and what’s going on. Last year I visited other prisons to photograph. In São João Del Rei, Minas Gerais, there was a similar workshop, with the photos of the prisoners exposed, they even made some magazines with the photos. It’s an extraordinary job. In this exhibition that we are going to do in Rio at Talavera, we are going to bring the photos of São João Del Rei. It’s a way for us to show that they should be seen with a minimum of dignity.

PMML: That word is very important: dignity. I think we are always in this quest and we have to impose limits on some situations and people so that everyone has dignity. And photos have that dignity too. It has been a tradition since the end of the 19th century, with Lewis Hine, Jacob Riis and later Dorothea Lange, of photography being an instrument of social transformation, what we call Humanist Photography. The photography you take is a very humanist photograph in the sense that it, like art, does not change the world, but it can change a person and that person changes another, who changes another, who changes another, and it becomes a movement that causes social change. Your photography is clearly focused on this aspect. Did the people you photographed feel more worthy, that is, did they feel honoured for being photographed by a minister? You are a photographer, but you are a minister. Did it bring you closer in any way?

Sebastião: One thing that was really cool in São Paulo was that the people who were organizing the photographs brought makeup and everything else. A production. The girl on the cover asked me: “Could you take a picture of me jumping?”. She is a ballerina and the photo, modesty aside, was wonderful. This shows their interaction. Now, I went to photograph a female prison in Minas, a female part, and it was like that, a small prison, almost a school, and the walls are covered with graffiti and stuff. I felt the inmates were a little self-conscious. They were

introducing me to the prison, the administration, the cells, the cafeteria, all those things and all of them were kind of shy with the scene. It’s a different prison where the inmates don’t wear a uniform, they wear their own clothes. They have a badge. It’s something that deserves attention, it’s my idea to write a book just about these APACs, which is a completely different prison. And there was a brunette sitting there in a colorful dress, with a turban, and you could tell that she had a certain amount of leadership over the others. I got close to her and asked if I could photograph her and she happily said “of course, no problem”, and took off her badge, glasses, jacket, and was only wearing a dress and turban. When I finished shooting, I was in the middle of the courtyard, with all the prisoners. The vast majority did manual work and then I shouted “who wants to be photographed?”. It was a rush, it broke the barrier, and the majority of them approached me to be photographed. It was extraordinary. It was one going in, another leaving, the prisoner changing clothes, returning to take a photo and her friends taking a photo together. And then it matches what you said, that is, what they felt at that moment. The big moment was, as I was leaving, an inmate came up to tell me that she had written a poem for me. She read the poem and we hugged, she was covered in ink. You clearly perceive the importance that it had for them, of feeling like people. Someone who doesn’t take advantage of them, someone really concerned about them, who wanted to do something, who wanted to value them. Then I printed the photos and sent them along with a link with all the photos. I think it’s a tiny step, but in those days they felt worthy. This serves to discuss, not only the issue of trans prisoners, but the entire prison system.

PMML: The time has come?

Sebastião: For the love of God...

PMML: It is tragic how much hatred exists, to the point that Brazil is the world champion in the murder of trans and LGBTQIA+ people. How come they don’t think that person also feels love? They are moved by the same thing, affection.

Sebastião: I’m not sure if you paid attention to the CVs of some of the trans people who wrote. It’s impressive. They are extremely prepared people, but who are put in the background without people knowing if they are good, honest, correct, integrated. And it’s not a matter of choice: she’s like that and that’s it. So-and-so’s sexual orientation is their issue and no one else’s. Guys, what’s the problem with that? I can’t understand where all this comes from. So I think the great advantage of the book is that it puts that out in the open. Trans people are just like everyone else, who often make mistakes the same way as a straight person. If they make a mistake, that’s it.

PMML: In the book, there is a sentence by [singer] Caetano [Veloso] that is very precise and tragic: “when you are arrested, you are forever imprisoned”.

Sebastião: You will carry this with you for the rest of your life.

PMML: What is the main cause of the incarceration of these trans people?

Sebastião: In fact, you might ask what is the major cause of incarceration in Brazil. In Brazil we arrest a lot of people, but in a bad way. In twelve years being a judge, I see a vision that prison would solve the issue of criminality. It won’t, it’s a mistake. When you arrest a person, if they don’t have lots of willpower and support out there, the possibility of their life being over is enormous. This does not depend on the kind of crime they commited. You have to take those people who are unable to live in society to prisons. A blood crime, the violent one, the abuse. Now, certain crimes, the occasional one, due to the circumstances of life and the moment, if the case is that

the person’s nature is not to be a criminal or act aggressively, they have to be treated differently. I think you have to see it with different eyes, because without resocialization, they will go back to crime, and often in a much worse situation, much more aggressive, full of hurt, hate, and then yes, the one who was a occasional criminal can become a habitual and violent criminal. The solution to crime is not prison and strict penalties. We don’t have a serious prevention and rehabilitation program, and the trans prisoner has a greater burden for being trans and an ex-convict. Or the big problem is that most feel abandoned by the family. There is a prejudice that begins at home. We need a program to reintegrate these people into society and work on prevention. Oftentimes, a person becomes a criminal due to lack of perspective. A fourteen-year-old child or boy who lives in slums often doesn’t have a father, they have a mother who wakes up at four in the morning to go to work and spends the whole day outside, when she doesn’t sleep at work.

PMML: They are usually Black people.

Sebastião: Yes. What are the references for this child? It’s drug trafficking. They aspire to be the leader of trafficking. The guy with the gold necklace, a ring, a watch, a car, and then he’ll get it into his head: am I going to work? I don’t go to school, I don’t have training, I don’t have anything. What am I going to do with my life? Am I going to work to earn a minimum wage, two minimum wages at most, working myself to death? Here I go, I take a drug here, I work as a firecracker there and I will earn much more. That’s what we have to think. While this problem of lack of better life expectancy is not resolved, of providing education and conditions for a person to progress in life, we are not going to put an end to criminality. It’s

no use thinking that prison is the solution, because when you arrest a person you involve the whole family. Most are in prison today because of the partner who took them to drug trafficking. Often the woman enters to meet a financial need caused by her partner’s imprisonment. This is very complicated and there is no simple, quick, immediate solution. To think that prison is the solution is a complete mistake.

PMML: Many people feel lost in life because they don’t have a father and mother or, worse, they have a father who beats them, rapes them, they have a broken family. It would be important for Brazilian society, the Judiciary, the Legislative, the Executive, all of us, to think about this idea of an extended family. It’s not the blood family, but the idea that it takes a village to raise a child. It’s everyone’s responsibility. Indigenous people say this a lot.

Sebastião: Today, it is the drug dealer who takes care of children. The State does not reach the slums, that’s the truth. It doesn’t provide health, school, anything. It does not give justice. The ones who play this role in slums today are criminals and their leadership, whether militiamen, as in Rio, or drug dealers. They take the place of the State. Which way do you think this person will go in the end?

PMML: To the nearest one, surely.

Sebastião: And the one that gives them comfort, support, protection.

PMML: Érika Hilton wrote about this idea of the double sentence. When a trans woman is arrested, she has a formal sentence, given by the Justice, and then she is trapped inside herself in a certain way.

Sebastião: In this prison where there are only trans people, everyone said that there they were being treated with dignity for the first time. They could wear their hair long, bra, panties. In the male prison they have no right to any of that, they are treated like men. The first thing they do is cut their hair. The vast majority of them undergo hormone treatment outside

the prison and, once inside, they cannot do it because the prison does not have the medical conditions for this, so there is a sudden interruption of the hormone treatment, and this reflects on the health status of the prisoners, which is something very strong. Even in humor. There are physical and emotional reflections.

PMML: That is, it is a third sentence.

Sebastião: Yes. And it’s not that simple. They built a prison in Minas Gerais only for transsexual prisoners. The idea was to solve the problem, but this is the prison with the highest suicide rate in Brazil.

PMML: Why?

Sebastião: Actually, it turned out to be an isolated prison. Minas is a big state. They took prisoners from all over the state and concentrated them in one place, and they started to not have intimate visits, monitoring, because it was difficult for husbands and family to visit. This created a lot of isolation. In theory it’s a wonderful idea. They will live without prejudice, there will not be that problem of an inmate in a male prison or an inmate in a female prison who may also be rejected by other inmates who are not trans. Everything is complicated. You imagine that you are solving a problem, but you create another one.

PMML: We return to this idea of an extended family. The person is not trans to be alone, isolated, they want to participate in society as a different, but normal person. I think Luís Roberto Barroso wrote that in the book.

Sebastião: Exactly. He wrote a poem. He writes about his vote that guarantees that trans women go to women’s prisons, but in the form of a poem. People really bought into the idea. I was really happy about that.

PMML: I think that more than happy, Sebá, you

were moved.

Sebastião: I did, I did, I did. I don’t deny it. I did, when I saw some things. The happiness of the people invited to participate in the book was very nice. There were people who bought the idea at the same time, vibrated “oops, how cool”, fighting for photos. It was very cool.

PMML: “This is mine! This is mine!”

Sebastião: Exactly. It was so nice.

PMML: Susie Linfield says that this huge amount of images we live with today took away the alibi of ignorance. That’s very interesting.

Sebastião: She said that sentence, do you remember that photo, that Syrian child that was found on the seashore?

PMML: A baby.

Sebastião: Yes.There was a huge debate about whether that photo should be published or not. And her phrase was said in this discussion, in this debate about the convenience of publishing it. And then, we already know, it was published, so it ended up winning. Many, mainly on the issue of the newspaper, I don’t know if it was the Washington Post or the New York Times that was responsible for publicizing the image, discussed at first whether they should, given the strength of the photo, publish a photo of a dead child on the seashore. The impact is very violent. In World War II, in a concentration camp, there was a prisoner who was a photographer and the prison director liked to take pictures, so he ended up becoming an assistant to the prison director. He found a way to preserve the negatives for when the war was over, to publicize what was happening inside. The reasoning is this, “I have to photograph and save the negatives, otherwise people will not believe this happened.”

PMML: It was a pleasure talking with you. Thank you very much for the interview.

Sebastião: You are welcome. It was a great pleasure to get out of my routine a little bit and talk about something that I really like, which is photography. I like it more each time.

Sebastião Alves dos Reis Junior

Sebastião Alves dos Reis Junior

The study of the body is what motivates Ukrainian photographer Sergey Melnitchenko, who portrays the freedom of the naked body in different ways, always seeking to distance himself from his other projects. The artist was born in a conservative city, but over the years managed to start a photography school and exhibit his work in the country, as is the case with the series “When I Was A Virgin”, chosen by Carcara, which exposes a personal reflection on the feminine body. Sergey started working in 2009, when his grandmother offered to buy him a camera in exchange for removing a new tongue piercing, and he hasn’t stopped since.

Sergey Melnitchenko

Sergey Melnitchenko

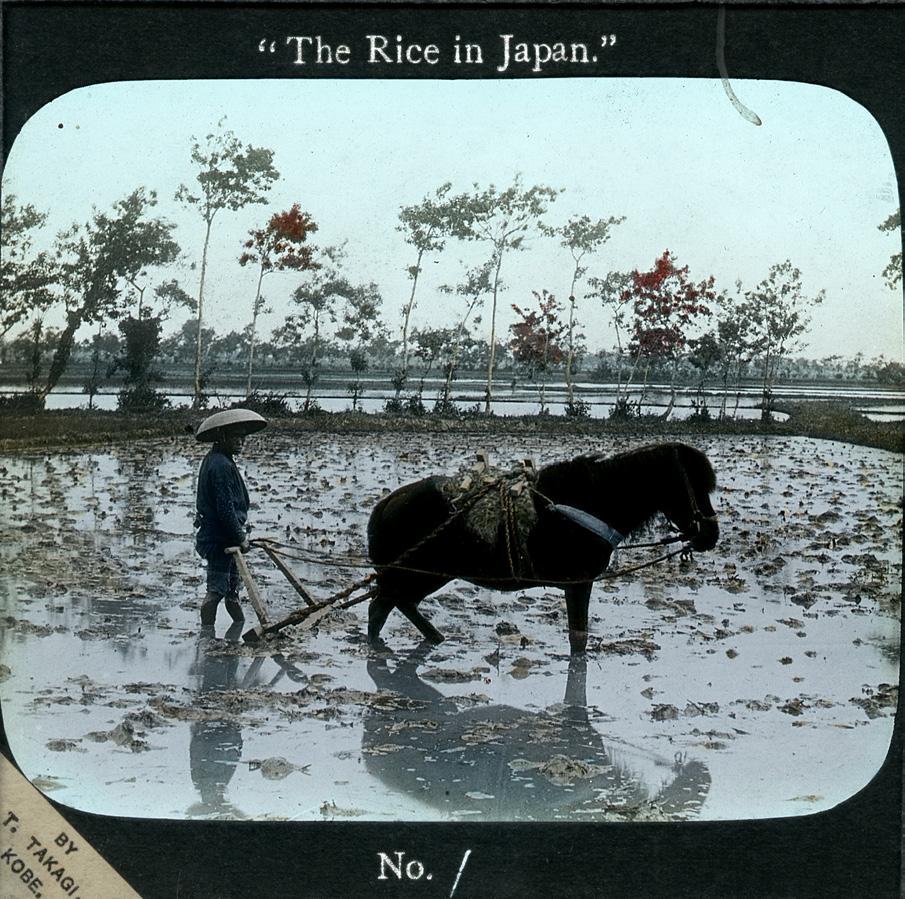

Teijiro Takagi, born in 1875, was a photographer who studied the art of photography with the renowned Kazaburo Tamamura, and helped him manage his shop in the city of Kobe until he became the owner and won the right to use the name Tamamura. The author produced at least 30 photo books, which showed Japanese customs and culture. Teijiro used his mentor’s name until 1914, when he began to sign as T. Takagi Photographic Studio and Art Gallery, where he worked until 1929. His work, which made it possible for the rest of the world to know the culture of his city and Japan, can be seen in this issue of Carcara.

Teijiro Takagi

Teijiro Takagi

EDITORIAL

Fotografia é a mais cerebral de todas as artes, uma vez que as decisões estéticas exigem muita atenção e conhecimento técnico.

RUBENS FERNANDES JUNIOR

On Fogueira Doce