THE FUTURE OF HOGAN'S ALLEY Hogan’s Alley Society continues to work towards building a future for Black Canadians amidst Vancouver’s history of structural racism SARAH ROSE Features Editor VALERIYA KIM Staff Illustrator

The Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts tower over the streets below like tombstones, artifacts of a stolen future—the future of Vancouver’s Black neighborhood. They represent the buildings and homes of over 800 residents in Hogan’s Alley (East Strathcona) that were razed in the name of urban renewal. Last June, the viaducts were the site of a peaceful protest where seven demonstrators, such as Capilano University (CapU) student Feven Kidane, were arrested for standing in solidarity with defunding the police and honouring Black life. Hogan’s Alley wasn’t the first vibrant Black community to exist in Vancouver, but if the city continues to halt progress, it could be the last. In East Strathcona, between Union Street and Prior is a trail of colourful graffiti. Follow it down past the shadow of condos to an overlooked shop that once was an unofficial shrine to Jimi Hendrix. Beneath the coat of fire-engine-red paint lay the remains of Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, a legendary Hogan’s Alley haunt for jazz era icons like Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole. Strumming further through these streets of the past reveals one of the fastest women in the world, Barbara Howard, who later became the first visible minority hired by the Vancouver School Board. Keep going, now stop. Look down from the pedestrian overpass on Raymur Avenue. Fifty years ago, a group of mothers from the Raymur Social Housing Project blockaded the train tracks below. The overpass is a memento of the fight for their community, so that over 400 children wouldn’t have to dodge trains to get to school. These remarkable

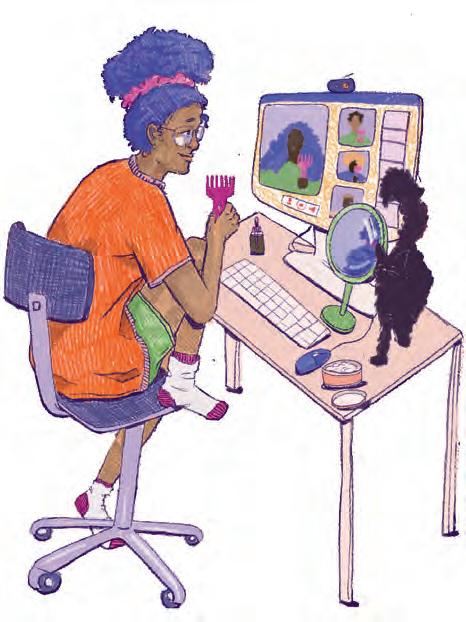

stories fall like winter rain among a sea of voices that will never be heard from, frozen in time. Today, Kidane can’t sit still—but that’s not unusual for the ADHD Gemini-rising. She wades through the rooms of their home, putting together a quick meal. “Do you mind if I eat my lunch?” she asked between bites. As the Capilano Students’ Union (CSU) Students of Colour Liaison, Kidane works tirelessly to be present in multiple spaces. Between assisting in organizing Black Lives Matter protests throughout the year, they also worked as a Youth Advisory Council Member. Echoing the spirit of the Militant Mothers of Raymur, as part of their work with Black Lives Matter, Kidane supported 13-yearold Marquice Jeffers-Harris’s mother in her fight to change hit and run laws in Canada when no charges were laid for the driver who hit Marquice with an SUV. Jeffers-Harris was left outside of his home by the teacher at his school in Surrey with nothing but a towel, unable to walk. Of everything Kidane does, what underpins their work is a message that if uplifted and held closer to more people, they might not have to work so hard for; “I’m just trying to join the fight for Black Liberation.” Yet Kidane’s presence within the city is something she is forced to think about all the time, because being Black in Vancouver is about sharing a language of isolation. “I should not have to walk through life like, ‘oh, there’s a Black lady that lives in my building? … Wow, I got lucky.’” F E AT URES

31