65 minute read

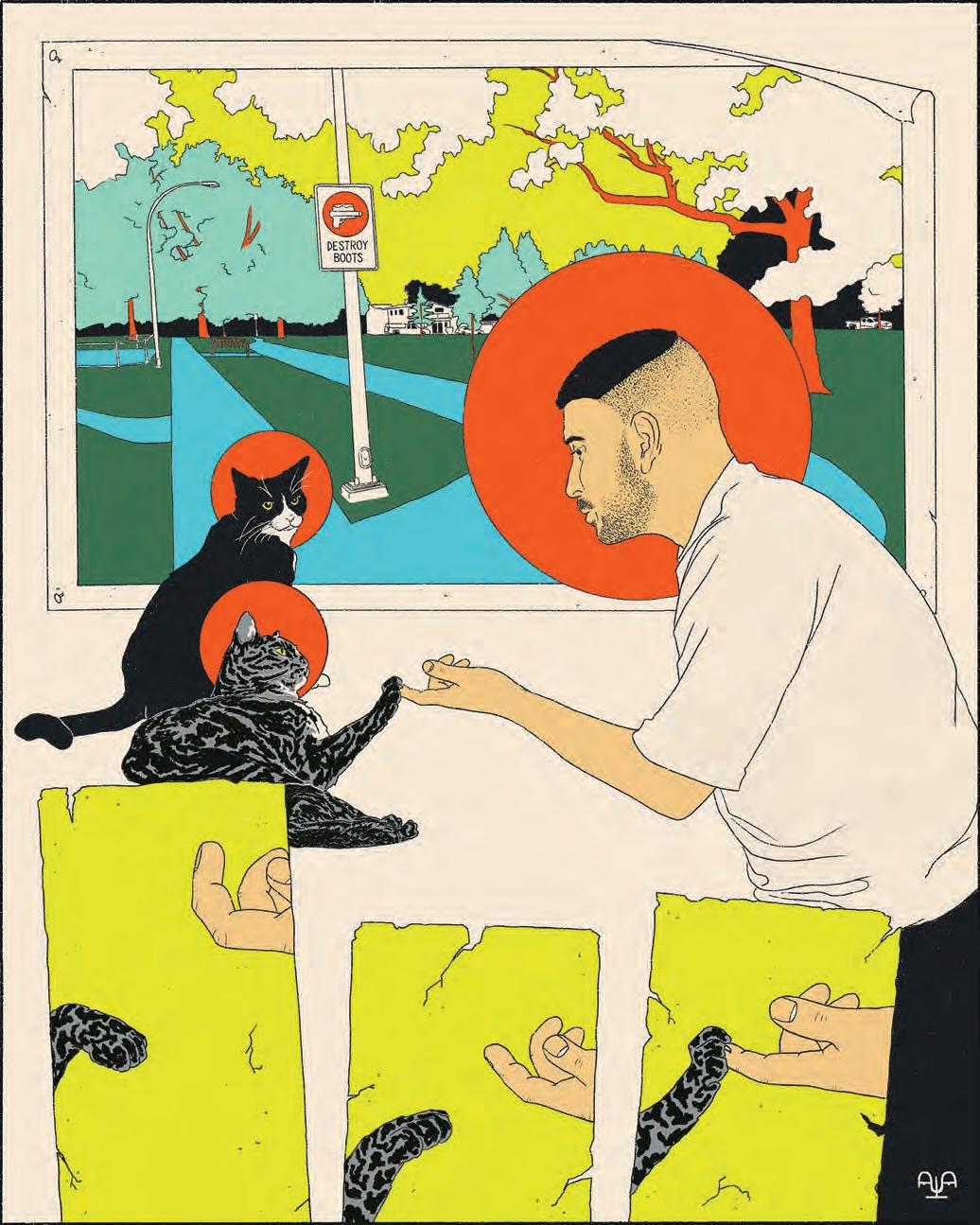

The Future of Hogan’s Alley

Hogan’s Alley Society continues to work towards building a future for Black Canadians amidst Vancouver’s history of structural racism

SARAH ROSE Features Editor VALERIYA KIM Staff Illustrator

Advertisement

The Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts tower over the streets below like tombstones, artifacts of a stolen future—the future of Vancouver’s Black neighborhood. They represent the buildings and homes of over 800 residents in Hogan’s Alley (East Strathcona) that were razed in the name of urban renewal. Last June, the viaducts were the site of a peaceful protest where seven demonstrators, such as Capilano University (CapU) student Feven Kidane, were arrested for standing in solidarity with defunding the police and honouring Black life. Hogan’s Alley wasn’t the first vibrant Black community to exist in Vancouver, but if the city continues to halt progress, it could be the last.

In East Strathcona, between Union Street and Prior is a trail of colourful graffiti. Follow it down past the shadow of condos to an overlooked shop that once was an unofficial shrine to Jimi Hendrix. Beneath the coat of fire-engine-red paint lay the remains of Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, a legendary Hogan’s Alley haunt for jazz era icons like Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole. Strumming further through these streets of the past reveals one of the fastest women in the world, Barbara Howard, who later became the first visible minority hired by the Vancouver School Board. Keep going, now stop. Look down from the pedestrian overpass on Raymur Avenue. Fifty years ago, a group of mothers from the Raymur Social Housing Project blockaded the train tracks below. The overpass is a memento of the fight for their community, so that over 400 children wouldn’t have to dodge trains to get to school. These remarkable stories fall like winter rain among a sea of voices that will never be heard from, frozen in time.

Today, Kidane can’t sit still—but that’s not unusual for the ADHD Gemini-rising. She wades through the rooms of their home, putting together a quick meal. “Do you mind if I eat my lunch?” she asked between bites. As the Capilano Students’ Union (CSU) Students of Colour Liaison, Kidane works tirelessly to be present in multiple spaces. Between assisting in organizing Black Lives Matter protests throughout the year, they also worked as a Youth Advisory Council Member. Echoing the spirit of the Militant Mothers of Raymur, as part of their work with Black Lives Matter, Kidane supported 13-yearold Marquice Jeffers-Harris’s mother in her fight to change hit and run laws in Canada when no charges were laid for the driver who hit Marquice with an SUV. Jeffers-Harris was left outside of his home by the teacher at his school in Surrey with nothing but a towel, unable to walk.

Of everything Kidane does, what underpins their work is a message that if uplifted and held closer to more people, they might not have to work so hard for; “I’m just trying to join the fight for Black Liberation.” Yet Kidane’s presence within the city is something she is forced to think about all the time, because being Black in Vancouver is about sharing a language of isolation. “I should not have to walk through life like, ‘oh, there’s a Black lady that lives in my building? … Wow, I got lucky.’”

Somewhere at the heart of Black displacement is Vancouver are the viaducts. Built in 1971 as part of an uncompleted plan for an eightlane freeway system, they separate what is now East Strathcona from Chinatown. Despite the city voting to remove the viaducts in 2015, they remain in place as monuments to an industrialist manifest destiny of highways and highrises. Through extensive lobbying, civic activism and resistance, the community prevented the remaining six lanes of the freeway system from being built. Protests, such as those Kidane was involved in during the summer, as well as activism against speculation—the practice of buying property and leaving it vacant for the purpose of reselling at higher prices in the future—as well unaffordable condo development. These are some of the ways marginalized communities in Vancouver continue to resist urban renewal.

There’s a book in Kidane’s house, The First Vancouver Catalogue from 1970, that contains nothing related to Hogan’s Alley. She says she once borrowed an extensive history book from a friend, which revealed only three sentences about the community, and “it’s all about the crime!” Look anywhere, and most—if not all—books dedicated to the history of Vancouver lack any record of Hogan’s Alley. “Go into the City archives—all you’re going to find [are] pictures of houses, of some people,” said Kidane. “It’s purposely erased so that people don’t have to feel like they were robbed of something.”

“When Hogan’s Alley was destroyed, Black people lost their core. People scattered all over the place, some residents returned to the [United States] because they felt safer with their own people. The displacement has exacerbated our isolation,” said Lama Mugabo, a community planner and activist. Mugabo currently serves as a board member for the Hogan’s Alley Society.

In Metro Toronto, the Black population is four per cent higher than the national average of three-and-a-half per cent, largely due to the presence of enclaves—geographical areas with high concentrations of a minority group. “An enclave is a place of calm and a place of protective identity,” said geography Professor Dan Hiebert for The Tyee.

The 1970’s in particular were a period punctuated by urban renewal and gentrification sweeping through many major cities in North America. In addition to destroying whole neighborhoods the way the viaducts did, it also comes with the cost of rising rent, higher taxes and displacement by a largely affluent white population.

“When people dig deeper, they quickly realize that the paucity of the numbers [in Vancouver] is not by accident. It’s by design,” Mugabo said. For marginalized identities that experience greater discrimination in society, having a space to call home, to take refuge, is everything. “I think about it all the time…Maybe I wouldn’t feel so weird being the only Black person in many, many spaces where there should be more Black people because the space and Earth demands that,” Kidane said.

After the City voted to demolish the viaducts in 2015, Hogan’s Alley Society proposed a Memorandum of Understanding and a 99-year lease with the intention of using a Community Land Trust (CLT) as a tool to begin revitalizing the land. CLTs are community owned non-profit organizations that can operate on a variety of scales, but are designed to keep land in perpetuity for the use of the community. The proposal includes a cultural center, childcare services as well as commercial space.

Six years later, and the city has made little progress despite continued efforts towards other projects. This could largely be due to the cities reliance on sales from a maze of new highrises and condos from developers that are intended to front the cost of removing the viaducts, which due to the pandemic, remains unclear when the city could see developers submitting applications. But Kidane worries it’s an issue of ongoing displacement in practices like redlining, or restrictive land title covenants. “If we were beyond redlining, Hogan’s Alley would be [already] here,” Kidane said.

In 2018, the ambitious Northeast False Creek Plan (NEFC), which won the American Planning Association Award, was approved. The NEFC plan is a 20-year proposal that would include building upwards of 25 highrises inside 58 hectares of land which encompasses Hogan’s Alley. It’s equivalent to a town the size of Prince Rupert. Green Party Councillor Adriene Carr voiced concerns in the four hour approval meeting for the NEFC that the proposed housing wouldn’t meet a realistic degree of affordability. “I feel 80 per cent [of the housing will be] high-end condos,” said Carr. The rate of affordable for-profit housing set by the city of Vancouver as of 2018 started at $1,903 for a one-bedroom unit in the West Side.

“The invasion of condo development gradually erodes [the] community of any sense of livability and heritage,” said Mugabo in an interview for The Volcano. According to the NEFC plan, the social housing proposed by Hogan’s Alley Society would sit on the East block of Main Street, opposite of the proposed condos on the West block.

“Community Land Trust is the best mechanism that will bring Hogan’s Alley back to life, in dignity,” explains Mugabo. The CLT would not only protect the land from speculation—preventing it from being resold to the highest bidder—but ensure access to real affordable housing, with all revenue made invested back into the community.

“A lot of cities are watching Vancouver. What happened here happened in Montreal, in Halifax, and other places in Canada,” said Mugabo. “We want real changes and a message to future generations that the city has atoned to its injustice against Black people.” Without a CLT, those like Kidane worry about what kind of place the land will be and for whom: “If it’s owned by the city, what is it really, who does it serve, will it be accessible?” If Vancouver wants to promise equality, then the first step should not be to rely on the whim of private developers—It should start with reparations. General Manager Gil Kelley discusses the NEFC plan for the American Planning Association Award as if he discovered the existence of Hogan’s Alley by accident through the project. In 2018, the city council issued a formal apology to the Chinese community for past racist policies, while the Black community is still waiting for acknowledgment.

Outside, Kidane catches their breath in between soft plumes of fog pierced by the winter sun. The need to just breathe for a moment—to

experience life in a space we can call home—is felt in every shared moment of silence. Still, she always carries a sense of joy and hope. “There is nothing hopeless when it comes to wishing that you had people that looked like you because that’s wishing that you had more life in your life.”

For all of us, the appreciation of beauty is coupled with a sense of loss, even if it’s not immediately visible. Buildings can never be just buildings. They can be havens of protection—they can also imprison and oppress. Buildings have the power to be tools for cultural destruction, to reinforce the colonial desire for expansionism. We look to buildings to embody the ideas we respect, to cradle us, like a mold where we become the visions of ourselves.

Architecture isn’t just a product of technological capability but a reflection of values and ideas. Often, buildings go unnoticed, until a silent explosion like losing the home, job, or family built within leaves an indelible mark on our lives.

Kidane believes in the heart of transformative justice, and in healing past wounds. “When I think about things like whiteness, I’m shocked how many people don’t look at that and think it’s heartbreaking because that’s self-inflicted cultural erasure,” Kidane said.

“[Black] People nod to each other in this city—It’s just acknowledgement. … It’s like; ‘good to see that I’m not alone.’” She paused for a moment. For Mugabo, breathing life back into Hogan’s Alley is one step towards building the communities of the future, but the viaducts remain artifacts of a future that was already stolen. A future that is already over. The idea of fully imagined cultural futures is a privilege of the past. As Han Kang writes in The Vegetarian, “faced with those decaying buildings and straggling grasses, she was nothing but a child who had never lived.”

We carry a critical responsibility to insure the living conditions for future generations, and it will remain out of reach so long as Canada’s foundation rests on a society built to sustain white supremacy. Many Black-led organizations in Vancouver struggle to meet the criteria for grants, and without more substantial widespread support, there is a real worry that the needs of the Black community could once again fall through the cracks.

Every day, we’re surviving historical events that spike closer together on the calendar like tachycardia on a heart monitor—ecological disaster, a pandemic, the public emergency of racism, and the collapse of work as we know it. The need for survival, family, and community faced by Black diaspora is nothing short of a crisis.

Learn more about Hogan’s Alley Society, volunteer or donate at www.hogansalleysociety.org

Ana Maria Caicedo @anamariacaicedo_

The Last Great American Queerbait

Why a “ship” on a genre television show is Why a “ship” on a genre television show proof of decades of queer erasure is proof of decades of queer erasureCLAIRE BRNJAC Arts & Culture Editor THEA PHAM Illustrator To understand the fervour behind queer “ships”—a term used to connote a wish for two characters to begin a romantic relationship—is to realize that there has been a long-running effort to erase or belittle queer people and relationships in media. In the 1930s, during the waning of the movie industry in America, the Motion Picture Production Code—also known as the Hays Code—was a set of rules established to change the public’s perception of movies to a more sanitized version due to mounting studio pressure. This code included rules like not showing interracial relationships, no childbirth or sex scenes, no positive criminal portrayals, and no taking the Lord’s name in vain. In the beginning, homosexuality in any sense was not allowed to be shown, but by 1941, a homosexual could be gay on screen but must be punished somewhere in the metanarrative in order to pass through the guidelines and be shown in theatres. Due to this code’s nature, characters believed to be gay had to show it in subtle ways, if any ways at all. Depicted and cast as “interior decorators” or “hairstylists,” these “pansies” had few ways to show their queerness—usually confirmed years after the movie had come out, through conversations with the actors or directors—or they are portrayed as serial killers or misfits from society, like in Silence of the Lambs. The Hays Code died out in 1968 when the Motion Picture Association of America created four well-known levels of ratings for moviegoers: G, PG-13, R, and X. But the effects of this code have been felt well into the present, especially concerning ideas around “public safety” and what a “good character” must present themselves as, which brings us to now. Social media exploded on Nov. 5 with the news that a male character, an angel named Castiel in the long-running horror/ fantasy television show Supernatural, professed his love to a human male named Dean Winchester. Before fans could rejoice, Castiel was immediately killed for that action and sent into a void of nothingness called the Empty, where he was to presumably suffer for all eternity.

Dean and Castiel’s relationship had been fraught with sexually suggestive dialogue throughout the twelve years since Castiel’s first appearance, constantly being called “boyfriends” by other characters throughout the seasons, and subtext frequently suggested by the actors of the characters themselves. In part, this relationship sustained the show, as many viewers tuned in to see Castiel and Dean interact. This directly ties into the notion of “queerbaiting,” a phenomenon in which producers will tease a queer relationship between two characters to attract and sustain viewers without making an effort to canonize the relationship— thereby avoiding the loss of more conservative or homophobic viewers. The writers and showrunners could tease that they know about it in an episode by mentioning it directly but do not seem to give it any actual thought in the show’s canon.

It seems, in a word, dated. As the years go on, queer people are making and writing their own content in the face of potential backlash from more conservative fanbases. With the death of Castiel, it seems Supernatural had unintentionally followed a Hays Code-era guideline—for their queer character to exist, he had to suffer for it. Queerbaiting will never be as strong as an actual queer relationship, with all the risks that come along with it. While it is excellent that this confession was made, it was cheap to immediately rescind it and regulate Castiel’s fate to a single line in the show’s finale.

The real motivations behind Castiel revealing his love will never truly be known, whether it is a loving reference to the fans who supported the ship, a last-minute viewer grab by the studio, or an honest decision by the writers and actors. Maybe Supernatural’s parent company, much like in the 1930s, forbade the relationship in fear of freezing out other viewers. In the end, we can mourn what would have been, and push for more well-written gay relationships in the future that hopefully don’t take 12 years to come to fruition.

THERE IS MORE TO ROMANCE THAN MEETS THE EYE

Romance novels: the domain of swooning, windswept heroines, heaving bosoms and shirtless, long-haired Fabios; ripped bodices, Harlequin novels, and poorly written smut. They’re that half-smushed paperback you found stuffed down the side of your grandma’s couch—something shameful and not worth acknowledging in the open.

Perhaps we should reevaluate that. Instead, jump into a media genre that guarantees a happy ending, increasingly pushes for more representation of all types and has a loudly unashamed and passionate readership community.

That probably sounds pretty fun to you, and if you’re thinking so, you’re far from alone.

Romance is an old, expansive genre where prolific writers are the norm, so there’s something to suit every desire. All kinds of storytelling are represented, and every trope remixed: nothing is sacred. Not only does this lend romance a willingness to innovate and play, but this also means there are miles of temptation with which to lure in new readers. As it happens, years of listening to a persistent friend finally wore down this now-devoted fan. I’ve never regretted giving in and have joyfully dabbled in many styles of romance, knowing there’s always something exciting on the horizon. So why is the romance genre routinely dismissed?

The short answer comes down to the genre’s core: it is typically written by women, for women and, as a result, mostly deals with the female experience. You will not have to search far to find long, florid descriptions of breathtaking heroes and heroines arriving to save the day and sweep someone off their feet. Romance oozes with the female gaze, and that’s one of its bestdefining features.

The female experience, however, is routinely seen as lesser by a patriarchal society that thrives upon ramming male-as-default down our collective throats. Men’s experiences of the world are considered the norm. Everything from medical studies to crash test dummies has assumed this and further consigned nonmale experiences of the world to a dusty little niche in a dark corner of the basement where there’s only one sad, dim lightbulb for ambiance.

As a result, an entire book genre is dismissed because they are completely and utterly entwined with women and their lives. When you think about it like that, it feels pretty crappy to dismiss stories about the lived experiences of a large proportion of the people on this rock simply because of sexism.

It’s time to stop referring to romance as a guilty pleasure and embrace the genre for the joy it brings

STEPH BLISS Contributor KARLA MONTERROSA Illustrator

Predictability is a similar method of dismissing romance because we all know how it ends, of course. People meet, they fall in love, and there’s a happily ever after. It seems rather boring. Turn that on its head, and you have a feature: there’s never any doubt that the characters will work it out by the end, and there’s freedom in being along for the ride when assured a good outcome. When the real world we live in is often confusing and alarming, a guaranteed happy ending is a balm to soothe those ills.

Despite these criticisms, romance is here to stay. It is quietly one of the biggest genres in publishing and has been a force in the industry for many years. Think about it like those Harlequin novels you have been semi-terrified of for years, but notice everywhere once you start to see them. Better, look for novels by authors like Nora Roberts, who is widely perceived as queen of the genre. Publishing multiple books a year, wealthy, and well respected, she typifies long-term success in a genre that subsists on it.

The romance community on social media is loud about their love for the genre and are only getting louder. They’re here to have the discussions about the thing they love, including the hard ones about diversity, representation, and the many other complex topics that romance often deals with. At its heart, people find joy in romance and wanting to improve the thing you love can be seen as the highest form of respect. Romance’s popularity can be seen in Netflix’s recent adaptation of Julia Quinn’s famous Bridgerton series. With high profile backing from Shonda Rhimes, you can be sure that the characters will have us all swooning for years to come. Those paying attention to viewers' responses can guess that this is only the beginning of a long and hopefully delightful trend of adaptations.

So the next time you come across a romance book, question your presumptions and perhaps give it a try. Find some happiness in a million different worlds that always end on a good note. Maybe one day soon, you can join that persistent friend and me on our mission to bring a little bit more romance to Vancouver, one book at a time.

You can follow Steph and her friend Denise’s dream of bringing a romance specific bookstore to Vancouver on Instagram @primerosebooksyvr.

Mistrust of Vaccinations

A Nehiyaw Perspective

TRISTIN GREYEYES Contributor JAIME BLANKINSHIP Illustrator

To understand why some Indigenous people hesitate to take the COVID-19 vaccine, you must understand the longstanding historical and ongoing systemic racism and discrimination they are dealt with by the government, western medicine and health care professionals.

As you may have learned in school, diseases were used as biowarfare to take land from and control Indigenous people. First Nations people did not have the antibodies to fight these foreign diseases, thus forcing nations to sign treaties in order to access the western medicine that would help save their people. This did not apply to all nations. West Coast First Nations did not sign treaties but were also impacted by the diseases.

What you might not have learned in school is that many residential school survivors have testified that children were being experimented on. There are too many other examples of racism that can be found in the healthcare field to list, but here are some modern-day examples: Mothers having their children stolen from them immediately after birth (birth alerts); First Nation children unable to access adequate health care that they need because of payment disputes (Jordan’s Principle); people dying in waiting rooms (Brian Sinclair); downplaying and minimizing patients concerns of wellbeing or over-medicating (Joyce Echquan); being accused of drug and or alcohol abuse and being sent home; and more recently, medical staff have been reported for gambling at the percentage of First Nations’ alcohol levels.

Now that we’ve established the racial inequalities and marginalization within Canada’s healthcare system, the hope is that you might understand where their mistrust lies when having a conversation with a skeptical Indigenous person about vaccines. Often, conversations around vaccination come off patronizing, but having a kinder, gentler approach when speaking about the importance of vaccinations, using plain words, is more constructive and positive. There are many ways to educate without making someone feel crazy for feeling scared. If you don’t have the patience, let Indigenous health care professionals do the talking.

All that being said, there are many Indigenous people and First Nation communities who are taking the vaccinations at their earliest convenience. First Nation communities across socalled Canada have taken the necessary steps to protect their community since the beginning of the pandemic. When it was understood that the older generations were the most vulnerable, leaders took immediate action to protect their elders. Elders are vital to our communities because they hold so much of our cultural knowledge and native language. In Indigenous law, which carries from one nation and culture to another, is that utmost care and respect we have for our elders. This law is a universal responsibility and kinship that we have. We keep our elders in our communities comfortable until it is their time to leave us for the spirit world. Many First Nation communities are being vaccinated, and so are their elders. This pandemic has tested the strength and resiliency of Indigenous people and First Nation communities, but they persevere yet again and continue to put the health and care of their communities as their top priority.

I hope everyone considers others’ well-being and future generations when deciding whether or not to take this vaccination. I do not judge anyone for fearing vaccinations. Fears are legitimate and can impact our livelihoods. I hope those who fear the worst find courage through others to take the vaccination. I want to go back to the ceremony, round dances, powwows, cultural activities with my family, and visit again without fearing passing on a deadly virus. I am so thankful this isn’t going to last forever. I am so excited to go back to those important parts of my life and to be able to raise my children in it.

The Trials and Tribulations of Online Sex Work

Support sex workers in a world where influencers can use their bodies to sell products but sex workers can’t use theirs to survive

SARAH MOON Contributor NAOMI EVERS Illustrator

With everyone and everything being offered on social media nowadays, we have seen an incredible rise in online sex work— especially in the wake of this global pandemic.

Online sex work has been a saving grace for many of us sex workers, even before the pandemic. It’s especially wonderful for folks with disabilities and/or mental health issues that make it difficult to do a regular nine-to-five job.

The pandemic has seen a surge in “survival sex workers”— those who have now hopped on the bandwagon with the idea that slangin’ pictures of their feet is going to be enough to pay the bills—and that’s just not true. Many of these people do very little research into the cause and effects of online sex work and how it can change your life forever.

Unfortunately, there is still a massive amount of stigma surrounding sex work and the individuals who provide it. Whether it’s hate, cyberbullying or the inability to post promotional pictures to social media without getting flagged. It’s clear these apps discriminate against sex workers—why else can an otherwise unremarkable John Doe pose nude with a trombone covering his genitalia on Facebook without a second thought?

It is a daily battle for sex workers just to be allowed to post on the internet advertising services and content to survive and that’s only one singular aspect. Online platforms are making it harder for folks to survive with shadowbans—a censoring tactic used on many of these platforms—and unclear Terms of Service.

Sex workers have to fight for their rights in multiple ways. We have to hustle every day in a social media world that doesn’t allow us to have or use our female form to our advantage—we are punished for it. I’ve had to delete so many memories, so much of my work and any media that gives the slightest hint that I have the female form or that I am a sex worker.

I have used ridiculous nicknames, different spelling and cheeky suggestions just to promote my work to prevent my social media accounts from being deleted. Such pet names as “Lonely Hams,” “Only Cans,” or “Onlee Fawns” to refer to OnlyFans, one of the most popular websites for independent online sex work. Having to resort to hilarious taglines like “L1NK 1N b10” to trick the social media bots into thinking I’m not selling content.

The Kim Kardashians of the world can post nudity freely and without consequence, while the rest of us are policed by bots and coding that removes our posts unless we cover our bodies or risk deletion, shadow banning or worse. These double standards are ridiculous.

When celebrities, and others with privilege and power, dip a toe into sex work without doing any research, it can cause real harm to sex workers dependent on those platforms. When

Bella Thorne made an OnlyFans account, she sent out a $200 USD pay per view (PPV) for pictures of her naked in bed. Thorne was able to post a direct link from her Instagram account, which is something us bottom feeders aren’t able to do. When the photos never materialized, the amount of refunds demanded resulted in OnlyFans setting a tip limit for PPV’s of $100 USD. They also introduced payment processing delays for creators in many countries.

Thorne considers herself a trendsetter for starting an OnlyFans, when the reality is she irreparably damaged the platform for all of us that have been grinding to survive in an online climate that doesn’t even allow us the ability to promote in any real way. Thorne’s wealth and power should mean that she deserves to be giving more than those bottom feeder sex workers struggling just to have a voice.

As it stands, all sex workers are going to be fighting censorship and demonization for a long time. You can help sex workers by sharing their content, tipping them, signing sex worker positive petitions, repealing bills like FOSTA-SESTA and speaking out against the censorship of women’s bodies on the internet, as well as in real life. It’s time we become pro-sex worker and pro-women.

An offical petition has been has been put forward by repel Bill-36 and decrimalize sex work in Canada. You can sign it at petitions.ourcommons.ca by Mar. 31.

Ignorance and Bliss in Vancouver, BC

The recently concluded New Leaf Project gave $7,500 to homeless people living in the Downtown Eastside, but was it enough?

JOSS ARNOTT Staff Writer ETHAN WORONKO Illustrator

There are two epidemics in the city of Vancouver: drugs and apathy.

My mother volunteered in the Downtown Eastside (DTES) while she was pregnant with me. It’s been twenty-one years since then, and the issue of homelessness still stands. Indeed, it’s gotten worse. We all know the sights and sounds; used needles and desperate screams, dried blood and distant police sirens. With an air of practiced ignorance, we see and then unsee the awful conditions that exist in the DTES. That’s because homelessness isn’t going away—empathy is.

It’s telling that it took less than a month for Vancouver to reinvent society when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Monetary aid was given freely, and we made sacrifices for the good of everyone. So how is there a decades-long homeless epidemic in the same city?

In 2020, over 1,500 people died from a drug overdose in British Columbia. In that same time frame, the COVID-19 pandemic claimed 988 lives in BC. In collaboration with the University of British Columbia, Foundations for Social Change launched the New Leaf Project in 2020. This pilot program tested the effectiveness of universal income for homeless people living in Vancouver. One hundred and fifteen participants were selected within specific parameters to maximize the study’s effectiveness: participants were required to have been homeless for less than two years and have no history of mental illness or substance abuse. Of the 115 newly homeless people chosen for the study, 50 were given a one-time bank deposit of $7,500.

The money was dispersed with no strings attached, and all participants had access to classes that taught basic finances. The study’s goal was to showcase that people can and will turn their lives around for the better when given a chance—and it worked. Those who received the money had better food security, found permanent housing faster and had more savings than their counterparts in the study who did not receive the lump sum.

Traditional social welfare is an IV drip: a little money given each month to keep people alive but it doesn’t let them live. That’s because it’s difficult to worry about rent, clothes or education when you can barely feed yourself. That’s why the New Leaf Project is so revolutionary. It offers trust and opportunity freely. An upfront, lump-sum gives someone the chance to find their feet. Suddenly, you don’t have to worry about surviving until tomorrow. You can plan for next week or next year, whether that means finding an apartment, going to school or getting a job. The choice is their own, and that’s why this project is so special. While the New Leaf Project helped fifty people get their lives back on track, over 2000 people in Vancouver identify as homeless. The idea behind the project is hopeful, but it alone will never be enough to solve the systemic problems inherent to this city’s core epidemic. The project’s goal is to stop people from getting absorbed by the DTES—not fixing it. Until we can address the substance abuse and mental illness rampant in the core of this city, it can never heal. Social housing gets people off the street, but it sure as shit doesn't stop addiction.

We don't need increased policing. We don't need to close more tent cities. We don't need any more band-aids. We need the municipal, provincial and federal governments to work together to help these people. And to do that, people need to start caring again.

We need to treat homeless people as people. You can’t glaze your eyes and stare straight ahead as you cross Hastings. Something has to change, and that something has to be radical. Clean injection sites, more social housing, the New Leaf Projects and even Vancouver City Council’s move to decriminalize drugs are all great initiatives, but these are band-aids being placed upon a gushing wound. The Downtown Eastside won’t change until we stop pretending that it isn't there. People are dying, and we’re not doing enough to stop it.

Cautiously Optimistic

What campus goers can expect the return to a new normal to look like

NIROSH SARAVANAN Contributor JANELLE MOMOTANI Illustrator

As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on, it has become increasingly clear that students are receiving the short end of the stick.

With a lack of resources, a shrinking job market and the other unique challenges facing the student demographic, campuses and student groups need to step up and help ensure that the new normal is more equitable than before.

One thing should be made abundantly clear: most students are not on the priority list to get vaccinated. Many Capilano University (CapU) students also live outside Vancouver Coastal Health’s jurisdiction, limiting their feasibility to return to campus. So, students should not bank on returning to physical classes soon. Instead, schools need to embrace this as a time to change and grow, and students need to speak up, voice their needs and provide feedback to their instructors to foster a better learning environment. Students and their representatives need to pressure the provincial and federal governments to safely and efficiently roll out the vaccinations—even as Canada ranks below its peers in terms of vaccination rates.

The new learning environment we’ve been subjected to can lead to the creation and proliferation of non-traditional education, which needs trial and error to develop successfully. It’s a great time to introduce new learning models, such as gamification (applying game design concepts into non-game areas such as a point system or dynamic role-play into the class). Another useful concept is the idea of a reverse classroom that strictly uses the physical classroom only for activities that require in-person participation and reduces the amount of contact required. This makes the classroom a more dynamic experience and could potentially alleviate some mental health hardships. Learning in a social, novel manner while being distant is a challenge, but one we can rise to.

CapU also needs to invest in ways to improve hygiene on campus. One method is improved air circulation. Another is fostering a culture of self-care, allowing students to take the necessary time to heal and recover when they are ill or suspected to be a carrier. By allowing students to isolate and manage their illness, it reduces the chance of transmission. Other new technologies are taking off now, such as UV lights capable of killing pathogens while not causing cancer.

However, these solutions should not come at the cost of environmental responsibilities. Littering has become a huge issue during the pandemic due to disposable PPE, but it is just one example of the pandemic’s impact on the environment. It’s everyone's responsibility to ensure that our recovery is not to the detriment of the environment.

Education isn’t the only area where the pandemic has affected students. The pandemic’s economic impact has also hit students hard. Initially, students didn’t qualify for the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). While the creation of the Canadian Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) addressed this, it was evident the priority of those eligible for relief were in the job market and arguably more financially secure. This contrasts against the employment patterns of many students who often work seasonal positions.

The pandemic has also had a significant impact on the mental health of students, which is already an underrepresented area. The grief and strife brought on by the public health crisis has hit students particularly hard. More resources need to be made available for students to help them cope during this dire time. On and around campus, counselling, helplines and The Foundry; a group of clinics focused on the well-being of folk aged 12 to 24, are all available to students.

Things will not be the same when students return to CapU— assuming they do. Many have reached the milestone of graduation during their pandemic, marking a shift in their life. Much like life after graduation, life after returning will have new directions and opportunities for the Capilano community at large.

Gianmarco Luele @giannimarx

Gianmarco Luele @giannimarx

Sexless in the City: Lessons Learned From a Toxic Tale

JAYDE ATCHISON Columnist

In 2016, I seemed to gravitate towards men that wanted my body but couldn’t appreciate my brain. I was left shaken after being told, “you’re not the kind of girl I could be in a relationship with, but if you want to just have sex, I would be cool with that.” Five different people had stood me up in six months, and my standards dropped so low, I considered it a successful date if the guy just showed up.

When I matched with a handsome guy on Tinder, my hopes were high, but my expectations were low. We had yet to meet, but I knew of him through mutual friends, so I felt safe agreeing to a date. The nature of the dating apps meant I had swiped right because I was attracted to his looks, but on this date I became attracted to his wit, intelligence, and life goals. It ended with a butterfly-filled kiss and a promise to see each other soon.

I thought maybe this was what everyone was talking about when they said, “when it’s right, you just know.” We sprung headfirst into a relationship, and three weeks in, we exchanged sentiments of our love. At a girl’s night, I found myself picking the lint off throw pillows just to hold myself back from gushing about the man I wanted to map out the rest of my life with.

We lived harmoniously, and I spent my 24th year feeling like the universe was finally on my side. Around my 25th birthday, something shifted; my rose-coloured glasses fell off and shattered beneath his feet. Slowly, I was being exposed to a different man, one that I didn’t recognize. The man who once appeared career-driven and goal-oriented became someone who pre-scheduled his tweets to make it look like he was up at five each morning getting a workout in, while in reality, he remained unconscious and hungover after another night out. I still felt love for him, and we spent Sunday mornings discussing how many people we would want at our eventual wedding. When I hit my social meter on a night out, I would whisper in my partner’s ear if he wanted to leave soon to go home and cuddle, but more often than not, he chose closing out the bar over me. Our relationship began pilling like my favourite sweater, slowly becoming unwearable. Fights over how busy I was became a trend and turned into arguments about how the idea of drinking until 3 am, on the one free evening I had, was a more attractive option than hanging out with me.

Sometimes a flicker of our fresh beginning would show when I would find little cheesy notes on my apartment door. I would catch myself smiling before I was reminded of the argument we had the night before. Gradually, I would hear his plans to spend the night out with friends whose names I had never heard before. I found myself having to fake laugh and offer excuses when mutual friends asked why I hadn’t come to an event I was never told about it to begin with. I had given all my trust to this human, so I had never suspected cheating until these moments arose. When I would ask, he would accuse me of being crazy, jealous or a poor listener because he most definitely mentioned these outings or friends to me. I would anxiously pick at my nails and question my reality, trying to convince myself my gut feeling was just paranoia, and if he said he loved me, that was the truth.

Our relationship faded as many do, but it didn’t go gently into the night. It left stains like the uneaten dinners thrown at my feet during an argument. I told myself I had to stay—things had to work out; they just had to. He was the first person to utter those three pretty words to me, and I was scared that no one would say them again. I chanted internally that these rocky times were normal in every serious relationship, but maybe people never talked about it. Looking back, there was nothing normal about feeling the rush of air next to my face as a fist hit the wall I was leaning against. Normality does not consist of telling your partner they are boring and that they wished they had a better girlfriend than you. Being made to feel less than isn’t something healthy couples go through.

As we kissed our final kiss, wet from both our tears, I was scared for what lay ahead but relieved that I could start to breathe again. It took two hard years after the break-up to be ready to be vulnerable with someone again. It felt like I slipped down a gutter, left alone with a Pennywise-sized hole in my heart. He pulverized my idea of love, left me ruined and convinced that I was always going to be left alone. Each time I saw someone demonstrating romantic interest, I felt my stomach curdle like old milk. What if they also screamed at me on Denman Street that I would never be enough?

I recently had someone confirm all those “paranoid and crazy” thoughts I had about his new nighttime friends while we were dating. It hurt, but it taught me to always trust my gut and be confident enough to walk away when the time presents itself. Despite all the toxicity that came with my first love, I have rewired my mind and am open to beginning a healthy relationship with someone that celebrates my achievements instead of putting them down out of jealousy and resentment. I am excited to eventually start a new journey with a person that sees me for all my quirks and imperfections and still chooses me every night. In the meantime, I will remind myself I am worthy of love.

Virtual Reality: Offline Means Left Behind

HASSAN MERALI Columnist

When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down much of daily life in March 2020, educational institutions were faced with a question: how will educators continue to deliver classes and other services when people can’t be in the same room together? Students and faculty were three-quarters of the way through courses that had already been paid for and funded. The end of the academic term was near, and students and faculty wanted certainty about how they would continue to learn and work. With few other options available, post-secondary institutions across Canada made a consequential decision— shift everything online.

Lectures, labs, assignments, tests, quizzes, and exams—everything went online. Even group projects went online (you’re excused if a shudder just went down your spine). It’s where much of modern post-secondary education takes place anyway. Almost all post-secondary institutions offer some fully online classes, and many have “mixed mode” classes that are half online, half in person. Even classes held in person must normally access resources and “fourth-hour” activities on eLearn.

From an administrative perspective, it was a familiar method of course delivery that could be expanded from some courses to all of them. With the unfamiliar nature of an evolving public health emergency and the challenge of hosting in-person classes that would comply with public health orders, it’s hard not to empathize with academic leadership here—there literally wasn’t much else they could do. Regardless, we should examine the cost of technology for accessing basic services at school.

If you were to look around the Capilano University Library on any given day prepandemic, you'd see tables full of students working on their laptops. But you’d also see many students working at one of the desktop computers available for use. For some students, those computers are the only way to get schoolwork done. It’s easy to slip into the mindset of thinking that every student has access to a device and a reliable Internet connection, but not everyone has that privilege.

You can get cheap laptops for a couple hundred bucks that handle basic word processing and connect to the Internet, but those are slow and typically struggle to run more than one program at a time. A laptop with enough memory and processing power to handle the demands of modern school life costs around $1,000.

Although some internet service providers lifted data caps because of the pandemic, home Internet plans are still costly for the average student. Cheap Internet plans in Vancouver start at $25 per month, but barebones plans like that often have data caps and very low download and upload speeds. For reference, the BC Government says something like remote education requires a minimum internet speed of 6-15 megabytes per second (mbps) both ways. This becomes important for online lectures, where some instructors require students to keep their cameras on to verify attendance.

There are supports for students, allowing Internet access and a device to work on, but they're limited. Through its Internet for Good program, the CSU partnered with TELUS to provide subsidized Internet access for up to 200 students. Under this program, students can receive Internet for only $9.95 per month with download speeds up to 25 mbps, but they must apply and demonstrate financial need. The CSU has a program called Device Doctor, where repair services are provided for free and students only pay for parts. For students without a device at all, the IT Help Desk in the library has some laptops available for long term loans.

When my laptop broke at the start of the Fall 2019 term, I didn’t have the money to get a new one that was halfway decent, so I decided to save and wait. Being without a computer was a situation I thought I’d never find myself in. For six months, I used my phone and the desktop computers at school to do my assignments. It gave me a whole new level of appreciation for the number of available computers on campus, and how late they keep some of those computer labs open (again, pre-pandemic). Not having a computer is a tenuous situation in normal times. During a pandemic when everyone is relying on digital technology and communications services for everything from school, to doctors appointments, to socializing and dating, it’s practically untenable.

It’s also a situation that’s probably been worsened by the economic pain caused by the pandemic. Many students work service jobs that no longer provide sufficient income due to the public health situation. Service workers receive fewer hours, less in tips, and can no longer rely on the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). Although the Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) helped many get through the summer, up to $1,250 or $2,000 a month doesn’t replace the amount students would have earned if they were working full-time. And the proposed Canada Student Service Grant (CSSG) program that sought to pay students for volunteering never materialized because of the Trudeau-WE Charity controversy.

Factoring in the cost of living in Metro Vancouver, alongside the fact that many students have to support themselves, it’s not hard to see how some students are not on a level playing field when it comes to technology. Many have predicted a shift to a more digital education for a while now, and if the last year has taught us anything, it’s that events like a pandemic accelerate transformations already underway. We don’t have to ever move to a completely online educational experience, but if we do, more support will be needed to make sure that those who are offline don’t get left behind.

Stories from the Long Walk: A transcendent moment on a long, dusty road

When I decided to join my mother on the long walk in Spain, known as the Camino de Santiago, I was excited to escape the damp autumn in Vancouver and spend it outside in the sun. Most of all, I was excited about the adventure.

For many, the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage is about seeking or discovering or questing. Some walk as a way of remembering, those who are grieving. Some walk with a partner, others walk alone—sisters, widows, longlost and life-long friends. People walk as part of their religious beliefs or for a spiritual experience. There are individuals in crisis, freshly out of a marriage, recently left a high ranking job—it’s people who need to escape. In just over a month of walking 20 to 30 kilometres a day, I met all of these people. As for my mother and I, we just wanted to walk together.

The word “pilgrimage” usually suggests a religious or spiritual connotation to attain a closer connection with a higher being, or to encounter God. The Camino’s origin is both religious and spiritual, but that is not always what draws people.

On the Camino, you will undoubtedly encounter a wide array of people such as the 19-year-old German girls ready to socialize over a few beers or the ever-quip-ready Irish folks laughing their way along the path. But ultimately, an air of reverence transcends the banter that happens along the way—most people had a quietness within them. There is something about walking all day, every day, only as fast as your feet can carry you, that brings moments of individual contemplation and bursts of pure, joyous laughter with others.

I noticed those there with a purpose—to spread ashes along the Camino or on a personal spiritual journey—were quite serious. Given the physical nature of walking, it was remarkable how focused these individuals were. It was hard to comprehend not laughing or joining in for a glass of vino tinto and patatas bravas in a town square. It seemed those were the moments that made the long walk worth it; the socializing and the feeling of absolute satisfaction upon arrival in each town.

Two weeks into walking, my mind slowed down to welcome every thought. My chest felt as if it had begun to open from the inside, and I could breathe more deeply. The air tasted sweeter. The blue chicory I walked by was seemingly bluer, and the pack on my back felt lighter.

This shift in my state of mind might have been a breakthrough but could easily be chalked up to sleep deprivation and genuine deliria from heat and all that walking.

After two weeks of walking, we came upon a fork in the road. There in the middle of nowhere, was an easily missed small stone chapel with its ancient stones crumbling at the edges. My mother noted that the door had been locked both times she had walked by on previous trips. We walked across a small courtyard, under the terracotta tiled porch to peek in the small door window. To my mother’s delight, the heavy wooden door swung open.

I left my backpack outside and stepped through the arched doorway onto the uneven stone floor. I stopped at the threshold—the atmosphere within was thick, palpable and heavy with the smell of incense and burning candles. The sweat on my back cooled with the absence of my pack. I closed my eyes and breathed. I opened them again to see a few plain wooden pews and a small stone altar covered with flowers and burning candles. Warm afternoon light from a small high window filtered in through the moted air. A light breeze tickled my face, and I breathed in the fragrance of incense and roses, feminine and soft. Turning, I saw a tiny nun sitting in the chapel’s darkened back corner. She stood as I approached, took my hands in hers, and softly said a prayer in Spanish before laying her old, gentle hands on my head. After a few moments, she grasped a small medallion hung on a light blue thread and I bent down as she placed it around my neck.

She seemed to have stopped time with hardly a word spoken—the only time was now, the only place was here. I thanked her before turning back to the front of the chapel. I sat in the nearest pew as hot tears stung my face. I could not stop the tears. I did not know where this wave of emotion had come from. Had I needed to have a big cry or was I just tired? It felt like quietude.

Later, when my face finally dried, I tried to understand why I had such a reaction in the chapel.

I considered the size and grandios ity of the churches and cathedrals we had visited over the last several days. Ornate buildings with breathtakingly beautiful stained glass and high ceilings, majestic pipe organs and echoing apses. None of them met me in the way that humble stone church had. As we walked on, I kept returning to the idea that perhaps I had found the kind of spiritual quietness—if only for a brief, weepy moment—that so many people seek when they embark on a journey far from home.

I sometimes reflect upon that day in the chapel as I walk to work in the mornings or back home in the evenings. I want to remember that at any moment I might be gifted with a return to that feeling of what I’ve come to call the “chapel feeling.” To be open to the possibility of finding something I did not expect or seek. Something that was waiting for me, a gift, if only I would push open the door and enter.

CHARLOTTE FERTEY Columnist

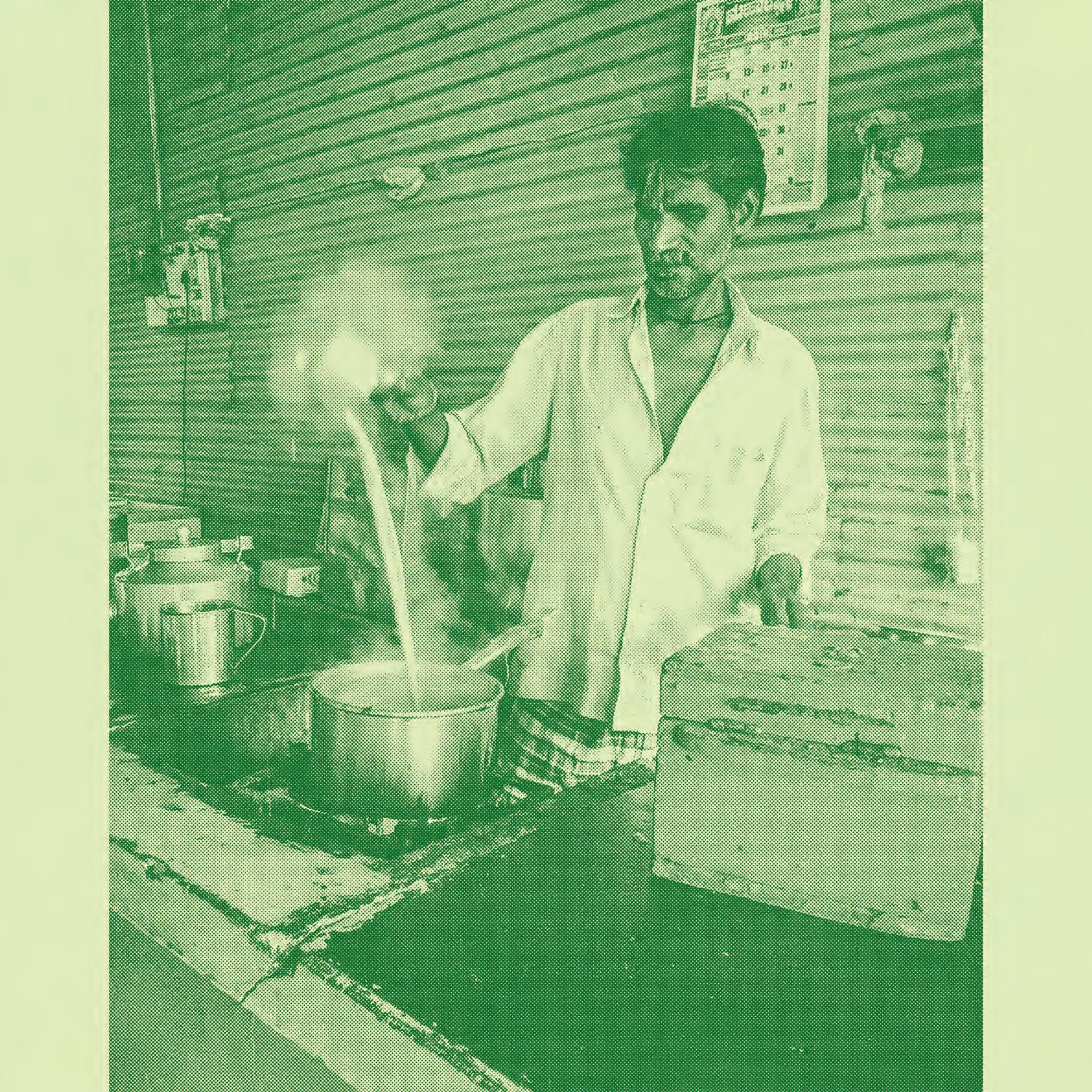

What's Brewing? Masala Chai: sweet, spiced tea with a bitter origin

CAM LOESCHMANN Columnist

Tea is a truly ancient plant—humans have been drinking it for thousands of years— but the teas of antiquity look much different from the beverages we drink today. As with any human invention, changes in time and place had various effects on tea. The biggest change, however, came with European colonialism.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Dutch East India Company started bringing tea to Europe to sell. Its popularity only grew when sugarcane plantations in the Americas started selling sugar back to Europe to sweeten the slight bitterness that tea naturally had. This sugar was inexpensive since the labour needed to grow and process sugarcane was provided primarily by enslaved West African people.

As camellia sinensis (tea) became more popular, it became necessary to grow it on huge plantations as sugar had been. This required expanses of land and populations of cheap labour. Since the British East India Company had power in India since the 1750s, they saw an opportunity in the region of Assam and started the first tea estates there in the early nineteenth century. “At first, this valuable commodity was strictly for export,” writes Justin Rowlatt for BBC News, “but as production grew and the price fell, Indians began drinking tea too … and they followed the example of the British and drank their tea with milk and sugar.”

As wonderful as it would be to travel to India to speak to a chaiwallah at the source, there is unfortunately, a pandemic going on. Fortunately, Shivam Jaiswal came to Vancouver four years ago and, unable to find authentic Chai here, started selling his own. Follow @ChaiWagon on Instagram for a daily update on where the carts are so you can try some for yourself! Jaiswal sells dairy and non-dairy versions, as well as snacks and tins of tea that you can make at home.

“Chai is not just a drink—it is a culture in itself,” said Jaiswal. “In India, Chai is much more than a drink to begin your day with. It has become an integral part of the culture and life of every Indian. In fact, if you take a walk around any local Indian road, you will definitely find chaiwallahs (tea sellers) steaming up a hot Masala Chai for their customers.”

Of course, Chai is somewhat different from typical black tea with a spoonful each of milk and sugar. “A regular cup of Chai in India is made by boiling water, milk, sugar and black tea together,” says Shivam. “We make our Chai as authentic as possible. We add fresh organic ginger and crushed green cardamoms in our Chai.”

This simple blend of two spices surprised me when I first tasted the tea from Chai Wagon. “Chai making process is really very simple. It has been made ... complicated here in the west.” The Chai blends made by the tea company I work for, for example, use many different blends of spices, including nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon, peppercorns, anise, fennel, allspice and chilli.

Jaiswal has a major pet peeve about Western Chai, aside from sugary Chai-flavoured syrups that are easily found in cafes and grocery stores. “Chai is an Indian word for tea. So when you say ‘Chai Tea,’ it sounds really weird. So I have a very humble request to all of you reading this … please forget the [term] Chai Tea, because it does not exist.”

In fact, Chai (and similar words) is the word for tea in many languages, with a few interesting exceptions, such as English. The origins of this discrepancy go back to China. Nikhil Sonnad writes for Quartz, “The Chinese character for tea, 茶, is pronounced differently [in] different varieties of Chinese, though it is written the same in them all. In today’s Mandarin, it is chá. But in the Min Nan variety of Chinese, spoken in the coastal province of Fujian, the character is pronounced te.”

It was these coastal areas of China and Taiwan that traded with early European merchants, so those seafarers brought back tea as well as the word that many languages now use for it, including “thé” in French and “tii” in Maori. Meanwhile, places that got their tea from anywhere else in China via the Silk Road, like Russia and India, still use the “cha” word root.

The old saying might be “for all the tea in China,” but nowadays, it might be more accurate to speak of all the tea in India, which “was the second-largest producer of tea in the world after China” in 2020, according to Sandhya Keelery for Statista. About a billion kilograms of tea were consumed within India’s borders—much of this is classic, sweet black tea known as Masala (“spiced”) Chai.

What makes Chai have such phenomenal staying power around the world, not just in its place of origin? We can talk about how dark, tannin-heavy tea plays well off of milk and sugar or how the rich spice flavours linger on the tongue. What keeps me, personally, coming back to the Chai Wagon closest to me is the warm conversations that I have with the people who make my Chai and the other people waiting in line next to me. Drinking tea by oneself is okay, but tea is made for keeping you company and making you new friends with whom to drink it.

Overlook, BC: A Wild Ride from BC to Beirut

DAVID EUSEBIO Columnist

I lived an hour away from Canada’s Wonderland in Ontario, so when my family moved to BC, I was disappointed by the absence of a theme park—Playland didn’t cut it. However, a second theme park was once proposed in BC, but the attraction behind this story isn’t the rides—it’s the owner.

Eddy Haymour immigrated to Halifax from Lebanon in 1955, worked as a barber, married, and had children. But it was after the family moved to Peachland, BC and fell in love with Rattlesnake Island that Haymour had a vision.

Haymour envisioned the island as a place that fused Middle Eastern and Canadian culture. Morrocan Shadou was to be decorated with mosques, pyramids, fountains, ice cream parlours in camel bellies, mini-golf and horse carriages. The only ride proposed was a submarine approaching a talking sea monster. Peachland residents were skeptical. “[It’s] impossible to bring into fruition. Almost like a kid’s fantasyland.”

Another resident said, “It’s always annoyed me that anybody would want to take an aspect of the Okanagan and turn it into something else.”

The mayor saw no issue, allowing the project to continue. However, when Haymour bulldozed part of the island to start constructing his theme park, Des Loan, the Minister of Health’s brother, wanted to halt the project for environmental reasons. BC Premier WAC Bennett listened to his aggravated constituents and stopped it. No septic or building permits were issued, and Haymour’s workers were denied dock access.

Haymour continued building his island, opening it up to the public prematurely— fifty people ventured to the theme park. How’d visitors get on the island? A sketchy ferry shuttled people, until a storm passed through and sank the ferry.

Haymour was sued, losing his island. The BC government gave him $40,000 for the loss—it was $140,000 when he bought it. Haymour was convinced it was a government conspiracy, but no one believed him except for a man named Ralph Schouten. He ranted to Schouten over dinner about how he “wish[ed] somebody blew up [Bennett’s] house.”

Unfortunately for Haymour, Schouten was an informant. Haymour was taken to court again on multiple charges with no evidence: conspiring to bomb Okanagan Lake bridge with Russian grenades; disfiguring his wife’s face with acid; access to M16 machine guns, and contacting a former explosives expert. Only one charge was accepted in court: brass knuckle possession.

Haymour pleaded insanity—not by his lawyer, but by the Crown, who likely realized that brass knuckles wouldn’t warrant a life sentence but an insanity charge would lock him up in a psychiatric ward for life. So, because of brass knuckles, Haymour was sent to Riverview.

One of Haymour’s friends found humour in this. “Anybody who went through what he [Haymour] went [through], he would lose his mind.”

Haymour wanted revenge but love must have come first because he danced with a nurse before meeting a new patient smuggling a hand grenade. Eleven months later, Haymour plotted to go to Victoria with the nurse and blow up the Legislature,but he didn’t go forward with the plan after a few dates.

Onto plan B: take over the Canadian embassy in Beirut.

He returned to Lebanon as civil war loomed and recruited his cousins. Eight people joined Haymour armed with AK-47s and prepared to take over the embassy—but only after a few games of backgammon. On the day of the operation, they stopped for a sandwich at a deli—I guess you can’t do a hostage takeover on an empty stomach. The group wore pantyhose over their heads and entered the embassy, approaching the unfazed passport officer.

Haymour ordered him to get down, and the group soon held thirty-four people hostage. All this happened without ambassador Alan William Sullivan’s knowledge until a bullet hit his office carpet. Haymour has a different story. “No bullet was shot through any door. No bullet was shot, period.”

“I still have the bullet,” Sullivan claims.

Haymour asked Sullivan to come out of his office. When he approached, Haymour kissed him on the lips. “I want[ed] to show them that I’m not a bad guy.”

Sullivan notified Ottawa about Haymour’s embassy takeover. Haymour’s demands were simple: he wanted his island, money, his children sent to Lebanon, and a psychiatrist to prove his sanity. That last one was a big ask at this point.

The embassy was soon surrounded by a hundred soldiers, but Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau told the army to stay out of it. Nine tense hours later, Sullivan quickly fabricated a telegram from Ottawa. He sent it from the embassy’s communications centre, stating, “we will do everything possible to help you in your problems.” Deputy Prime Minister Allan MacEachen’s name was used sans consent, but it worked as Haymour signed the telegram.

When asked if traumatizing all those people was justified, Haymour answered, “We didn’t

kill nobody, and we succeeded. So, that’s victory to everyone.”

The Lebanese Military Court charged Haymour for misdemeanour, slapping him with a $200 fine! He was allowed to return to Canada because, apparently, capturing a Canadian embassy wasn’t a crime. With federal government assistance, Haymour paid his legal expenses and faced BC Chief Justice John Farris. The court proceeding dissatisfied Haymour, so he flipped the judge the bird and bought a machine gun. When asked if he planned on killing the judge, he responded, “Yeah. What, I’m going over there to play a game or something?”

Haymour didn’t follow through, leaving the gun with his lawyer. Instead, love swooped in again when he met his second wife, Pat. On one of their first dates, they went hunting, and she shot twenty-seven bears. Pat wasn’t impressed with Haymour’s lawyer, “That guy is as useless as tits on a boar.”

When the CBC obtained confidential documents, they gave them to Haymour to forward to his lawyer, and guaranteed that he wouldn’t lose. Haymour went to trial again with the Harvey Specter of cross-examiners: Jack Cram. One of his arguments was this: how can Haymour be deemed insane enough to go to Riverview but be well enough to sign over his island to the BC government? Valid point.

Haymour won the trial, and the BC government paid him $200,000 for his losses. He was pleased. “At least the world knows that I was right, and that’s good enough for me. For now.”

He used his settlement to immortalize his vision of the island as a castle hotel near Okanagan Lake. Each room had a Middle Eastern theme, and a statue of Haymour was erected on the lawn, pointing towards Rattlesnake Island, “That’s a sign to the government saying ‘You bastards, that’s my island. And will remain mine.’”

After five years, Pat left him, and he abandoned the castle. Peachland obtained it for under $16,000. To this day, Haymour continues to try reclaiming Rattlesnake Island. I’m sure John Horgan gets voicemails from him daily with his new vision for the island. “I want to make it the best cemetery in the world.”

Cyberpunk 2077 Release Gives Local Man Hope He Can Still Be Loved Despite Being Deeply Broken

SARAH ROSE Features Editor VALERIYA KIM Staff Illustrator

Mike Jones, 29, is one of the millions of players eager to play the long-awaited Cyberpunk 2077 since it’s announcement at E3 in 2012. The dystopian game, which appreciated almost a decade of unparalleled hype, swept several prestigious Game of the Year awards leading up to a delayed and disastrous December 2020 launch.

Jones, a Metro Vancouver native, with reportedly 400 hours of playtime logged in the controversial game told reporters he had never related to anything more personally and existentially than Cyberpunk 2077. “It’s the only thing I have ever seen as profoundly broken as I am that’s still loved by millions despite its flaws,” said Jones, holding back tears.

Jones shared how his girlfriend, Samantha, broke up with him seven years ago, after two dates. He says that he too was considered “broken” by many of his close friends on various pickup artist forums. After the launch of Cyberpunk 2077, however, Jones felt renewed inspiration.

From being completely emotionally stunted, to a nostalgia machine for 30-year-old genre classics, to having a 4-terabyte hard drive of trans chaser porn involved somehow, “I just really related to that,” said Jones.

The game's release inspired Jones to start a streaming channel under the username ‘Based_Kekistani_1488’ on popular platform Twitch to share his views. He’s hopeful that he, too, despite having a sudden inability to function if he sees a woman with a similar hair colour to Samantha walking within one hundred yards of him, can find a supportive fanbase that find his flaws quirky and appealing. Sources confirm that as of January, Jones had made friends with popular like-minded Twitch personalities such as JonTron and PewDiePie. The following month after launching Cyberpunk 2077, developers watched billions casually shaved off their stock value. Similarly, Jones explained how he was “devastated” after learning through catfish accounts—used to monitor Samantha’s social media— that the 25-year-old appeared to be in a relationship with a new man named Dan. Described by Jones as “a blue-pilled soyboy beta cuck,” Dan allegedly has a full-time job and appears functional in public places without breaking down.

The 29-year-old looked weary from the dim lighting of his parent’s basement in Surrey as he pointed to a caption on one of Samantha’s Instagram posts. The caption details her appreciation for Dan listening to her concerns and making an effort to fix his problems. “See? It’s just like Doctor Jordan Peterson says, feminism is chaos.”

“People assume that because I’m a licensed pickup artist, I don’t respect women, but it’s not true,” explains Jones. “Ready Player One taught me the perfect cyberpunk girl-next-door that caters to all my white male tokenistic fantasies is out there waiting for me, and she’ll love me despite my deep character flaws.”

Polish studio CD Projekt Red went on to confirm last month that any racist and transphobic content that players may find in Cyberpunk 2077 is just part of the plethora of countless bugs. Amongst other well-known glitches, such as non-functional graphics, objects exploding and defending police officers, Jones expressed his ongoing, steadfast solidarity with the studio. “I totally get it. It’s crazy, you spend so much time trying to make sure every little thing about your game works and you can still get ‘canceled’ by females for, like, a casual line about crime statistics that might just be a dog whistle for white supremacist talking points!”

Dan couldn’t be reached for comment.

I won't tell you

Ok I will tell you about the wild apple trees and how I raced against squirrels and ants to taste the fallen apples

I will tell you about how once I treated myself with wild cherries so full that I hiccupped and how despair I was staring at the cherry tree as tall as a multi-floor building or the one hanging over the waters I will tell you about how the poplar leaves fell and the crisp sound of them breaking away from the branches and what a dance t h e y

d a n c

e d

a l l

WEN ZHAI Contributor VALERIYA KIM Staff Illustrator

I will tell you about the squirrel that decided to run towards me on a narrow bridge

I will tell you about the duck that patiently led my way on the forest path

I will tell you about the raccoon that approached me and stood on its hind legs to carefully observe me

T h e

w a

y

to the ground as if they were not coming to their deaths but to join a party celebrating life

I will tell you about the grey heron that met me three days in a row on a beach at dusk Standing or walking up and down in the water meters away from me until I became confused of who was taming and who was tamed I will tell you about the two seagulls stopped in mid-air in front of me as if inviting me to a show dropped clams on the pebble beach and cracked them open for lunch Twice on a hot summer day while I was reading barely in the shade on a bench not far away I will tell you about how a deer casually crossed the path before me to join its friend without one bit of fear as if I was one of them

Maybe I will also tell you the sound of a group of geese flapping their wings flying along the shore so low that if I wasn’t behind a tree I might be able to touch them But I won’t tell you Where all these happened

No Way

Virgo Aug. 24 - Sept. 23 Get yourself something new. It could be anything! Just make sure it fits. If you’re overthinking it, remember that your picky ass won’t like it as soon as you get home anyway, so really, anything goes.

scorpio Oct. 24 - Nov. 22 Get a new hobby or two. Distract yourself from whatever rage you’re still holding onto from when you were five. I’m not saying to get a therapist, but you could benefit from confessing your sins to someone.

Capricorn Dec. 22 - Jan. 20 I know you’ve got your Instagram set to private (or maybe you just muted me), but I’m here to tell you it’s okay to open up. Unblock me so we can talk about your abandonment problems like real adults.

Pisces Feb. 20 - Mar. 20 I love the energy you’re giving lately. Wearing your heart on your sleeve, I see. Whatever’s got you in a different mood these days gives you a glow that pregnancy could never. Keep it up.

Taurus Apr. 21 - May 21 Get off your ass and get a job. You don’t need this new thing or that new thing—you need health insurance.

Cancer Jun. 22 -Jul. 23 Homemaking is in big focus for you. You can’t help it when we’ve been under lockdown on and off for quite some time, and your yellow wallpaper starts to have a new appeal. Try talking to it. Libra Sept. 24 - Oct. 23 All’s fair in love and war—and Twitter beef. Don’t take the things your ex says and does so personally. You don’t need to play nice. In fact, go argue in the Vice News comment section for practice.

Sagittarius Nov. 23 - Dec. 21 Go to your local Home Depot and chop some wood. Build a tiny home, then decorate it with your grandma’s heirlooms. Commit arson. Blame your cat. Profit.

Aquarius Jan. 21 - Feb. 19 Stop throwing rocks and then hiding your hands. No more avoiding consequences, put your big boy pants on—no seriously, change pants. The ones you have on...yikes.

Aries Mar. 21 - Apr. 20 Health at this time may be a priority for you. I hope you’ve been healing the way you’ve needed for so long. Consider adding this to your new regimen: a smoothie made of Red Bull, Monster, and 5-Hour Energy.

Gemini May 21 - Jun. 21 Take things slow for now, Gemini. I know you have a lot on your plate, but do you see what your cousins, Donald Trump and Azealia Banks, have been up to? Call a Gemini team meeting and fix it.

leo Jul. 24 - Aug 23 You’re quiet lately, Leo. Don’t forget your shine, baby—we love to see you glow! Except for that time you puked at the club, crying because no one bought you a drink all night, and we had to escort you home.

Ata ojani @___atatata___