How a Safe Step Walk-In Tub can change your life

Remember when…

Think about the things you loved to do that are dif cult today — going for a walk or just sitting comfortably while reading a book. And remember the last time you got a great night’s sleep?

As we get older, health issues or even everyday aches, pains and stress can prevent us from enjoying life.

So what’s keeping you from having a better quality of life?

Check all the conditions that apply to you.

Personal Checklist: Arthritis

Insomnia

Diabetes Mobility Issues

Lower Back Poor

Then read on to learn how a Safe Step Walk-In Tub can help. Feel better, sleep better, live better

A Safe Step Walk-In Tub lets you indulge in a warm, relaxing bath that can help relieve life’s aches, pains and worries.

A Safe Step Tub can help increase mobility, boost energy and improve sleep.

It’s got everything you should look for in a walk-in tub:

• Heated Seat – Providing soothing warmth from start to nish.

• MicroSoothe® Air Therapy System – helps oxygenate and soften skin while offering therapeutic bene ts.

• Pain-relieving therapy – Hydro massage jets target sore muscles and joints.

• Safety features – Low step-in, grab bars and more can help you bathe safely and maintain your independence.

• Free Shower Package – shower while seated or standing.

Merrifield

Features

20 OVERLOOKED

A trio of courageous acts of war left unrecognized

By Stephen J. Thorne

30 THE CANADIAN SAMURAI

Great War Sergeant Masumi Mitsui never stopped fighting for right

By Russ Crawford

34 PROFESSOR HEALY AND THE PARTISANS

Canadian Captain Dennis Healy, a peacetime university prof, played a pivotal role alongside locals in the liberation of the Italian city of Ravenna

By Mark Zuehlke

40 HELP WANTED?

Exploring the trials and tribulations of Canadian liberators in Europe

By J.L. Granatstein

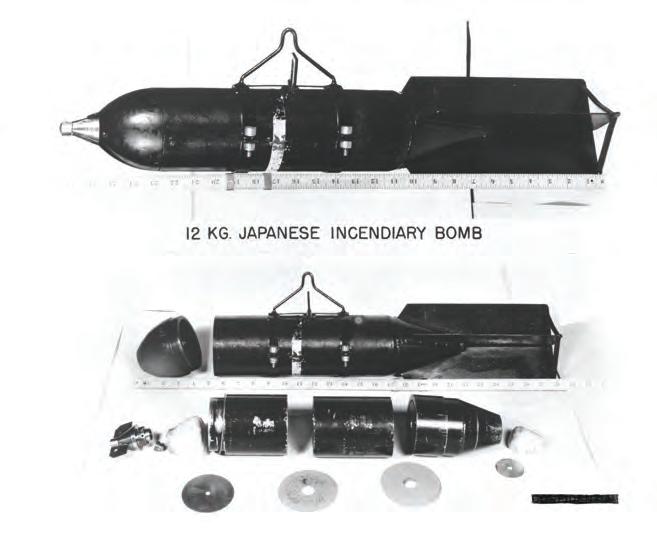

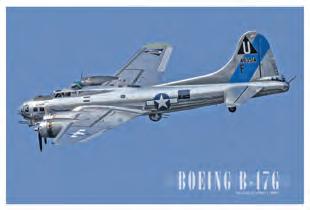

46 BOMBS AWAY

The wild story of Japanese balloon bombs floated over North America

By Alex Bowers

52 FIRST CALL

The Royal Air Force’s all-Canadian 242 Squadron finally gets into action. An exclusive excerpt from Battle of Britain: Canadian Airmen in Their Finest Hour

By Ted Barris

58 KING OF NECESSARY

Looking back on Prime Minister Mackenzie King as Canada’s wartime leader

By J.L. Granatstein

64 MOVING TOWARD

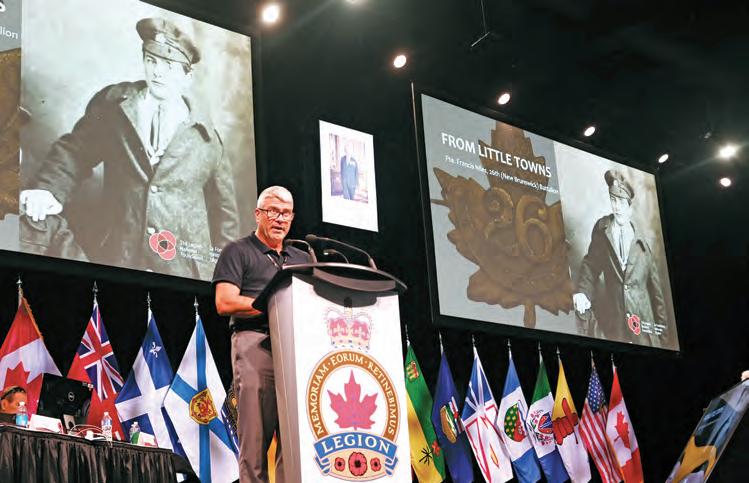

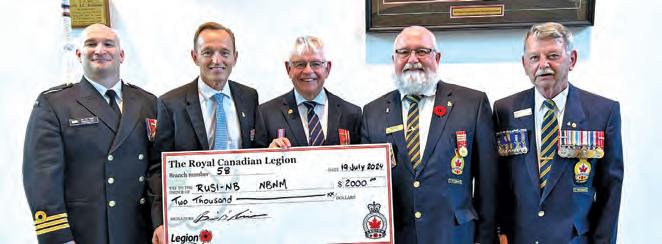

From technological innovation to membership growth and beyond, The Royal Canadian Legion shows no sign of slowing down as it approaches its centennial By

Aaron Kylie

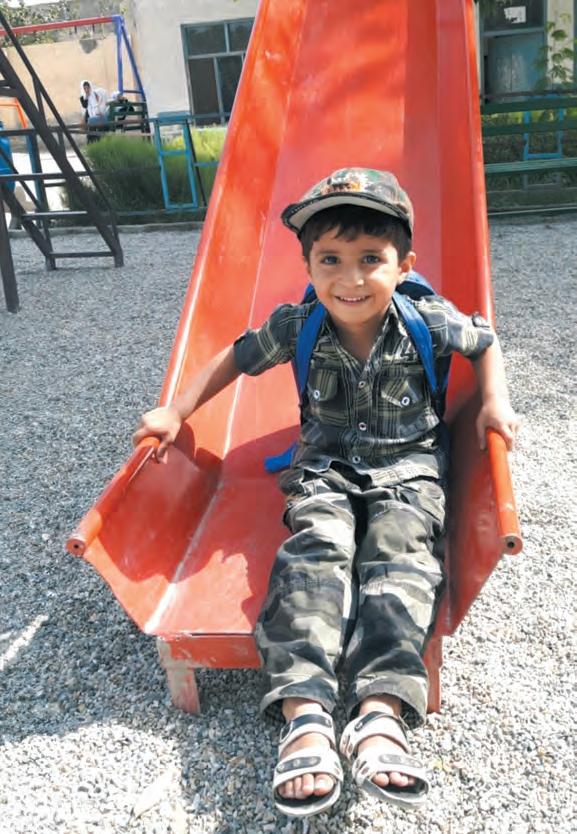

72 WAR AND PLAY

A Canadian charity works to build playgrounds in wartorn areas around the world

Words by Leslie Anthony

THIS PAGE

Locals welcome their liberators in Utrecht, Netherlands, on May 7, 1945. J. Ernest DeGuire/DND/LAC/PA-171747

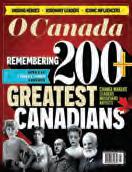

ON THE COVER

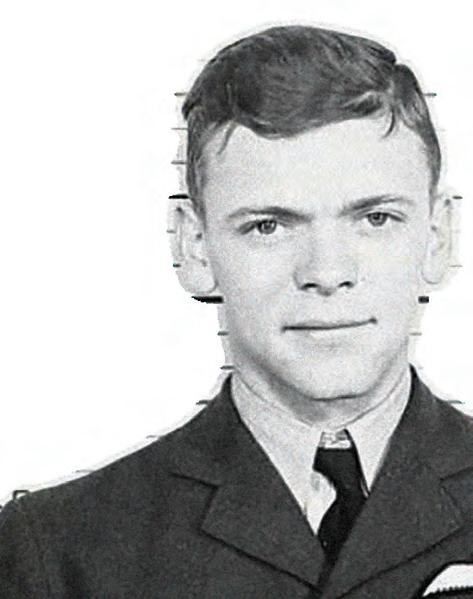

Members of 242 (Canadian) Squadron, Royal Air Force, in 1940. Imperial War Museums/CH1413/Wikimedia

78 FACE TO FACE

After early Canadian-led attempts to advance across the Netherland’s Walcheren causeway were unsuccessful, should the move have been abandoned?

John Boileau and Stephen J. Thorne

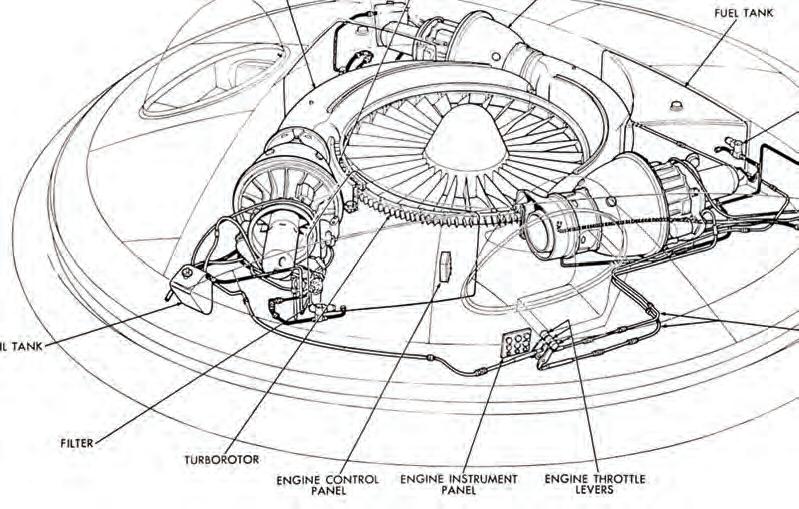

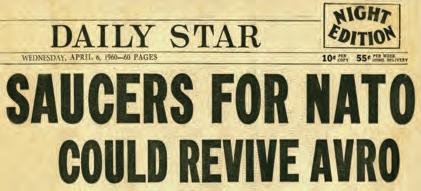

Mars attacks!

2025 WALL CALENDAR

Board of Directors BOARD

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin

SALES/

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

EDITOR

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Alex Bowers

|

Sophie Jalbert

DESIGNER

Serena Masonde SENIOR

| advertising@legionmagazine.com MARLENE MIGNARDI 416-843-1961 | marlenemignardi@gmail.com OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

AND MARKETING CO-ORDINATOR Dyann Bernard WEB DESIGNER AND SOCIAL MEDIA CO-ORDINATOR

Ankush Katoch

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2024. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $9.96 per year ($19.93 for two years and $29.89 for three years); prices include GST. FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $10.91 for one year ($21.83 for two years and $32.74 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $10.72 for one year ($21.45 for two years and $32.17 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Change of Address

Send new address and current address label, or, send new address and old address. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com/change-of-address. Allow eight weeks.

Editorial and Advertising Policy

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $9.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of Alliance for Audited Media and BPA Worldwide. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and e-mail magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

Give ’em

shelter

The Royal Canadian Legion is experiencing a post-COVID membership bounce, and it couldn’t have come at a more opportune time.

Innovative marketing and easier sign-ups combined to boost RCL membership to 256,524 in 2023, a 5.3 per cent increase over 2022, when total paid membership was already up 3.8 per cent from the year previous. They are the first membership increases in decades.

“ VETERANS ARE TWO TO THREE TIMES MORE LIKELY TO EXPERIENCE HOMELESSNESS COMPARED TO THE GENERAL POPULATION.”

While Legion numbers are on the rise so, it appears, are the number of homeless veterans.

In his report to the RCL’s national convention, Dave Gordon, adviser to the Legion’s Veterans, Service and Seniors Committee, suggested demand for services to homeless veterans is greater than ever. This despite— or perhaps because of—increased awareness of and efforts to document and address the homeless veterans issue in Canada.

Drawing on data from the Leave the Streets Behind Homeless Program and reports from the RCL’s provincially based resources, Gordon said the total number of homeless veterans identified and assisted rose to 1,234 in 2023.

In their 2023 paper “Addressing veteran homelessness in Canada” for the Max Bell School of Public Policy at Montreal’s McGill University, however, Anmol Gupta, Alison Clement, Sandrine Desforges and Taylor Chase put the issue in perspective.

“Veterans are two to three times more likely to experience homelessness compared

to the general population and are disproportionately represented among individuals experiencing homelessness,” they write, noting that estimates of the number of unhoused veterans in Canada varies widely from 2,400 to more than 10,000. While veterans’ homelessness “is not unique to Canada,” they add, “countries like the U.S. have made significantly more progress in reducing the number of veterans experiencing homelessness.”

In 2023, Ottawa announced a $79.1-million veteran homelessness program, establishing two funding streams to support civil society and sub-national governments to provide rent supplements, deliver social services and improve research.

But more action is needed, say the authors.

“With fragmented and siloed programs across the country, poor understanding of the scale of the issue, and the incredibly diverse nature of the causes and experiences of veteran homelessness, it is not clear that more money—without clear federal leadership and co-ordination— will bring about meaningful change.”

With the growing housing crisis, they warn, “more veterans will disproportionately fall into homelessness should the federal government not take a more proactive and human rights-based approach to this issue.”

The paper cites a lack of federal departmental leadership on the issue and blames the discrepancies in numbers on the unique nature of veterans’ homelessness: the preponderance of ‘hidden homelessness,’ such as couch-surfing or living in vehicles, and the fact many veterans tend not to interact with shelters and food banks, which comprise the most common data-collection sites.

The RCL is uniquely positioned to overcome these obstacles. Fundamental tenets of its existence are its role in advocating and assisting veterans. Its national programs rely on the efforts and intelligence provided by grassroots members.

Among the more encouraging elements of the recent membership rise is the fact that the new recruits are coming from younger demographics—21 per cent are 45 or younger and 30 per cent are 50 or younger. Their energy and ideas will be invaluable to the efforts to better serve Canada’s veterans. L

ATTENTION CANADIAN MILITARY FAMILIES

Did you or a family member receive VAC disability benefits between 2003 and 2023?

A class action settlement may affect you. Please read this notice carefully.

On 17 January 2024 the Federal Court approved a settlement in a class action involving alleged underpayment of certain disability pension benefits administered by Veterans Affairs Canada (“VAC”) payable to members or former members of the Canadian Armed Forces (“CAF”) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) and their spouses, commonlaw partners, survivors, other related individuals, and estates (the “Settlement”).

If you received any of the disability-related benefits listed below at any time between 2003 and 2023, you may be entitled to compensation under the Settlement. As the executor, estate trustee, administrator, or family member of a deceased class member who collected VAC-administered disability benefits, you may also be able to claim on behalf of the estate. If you are entitled to compensation under the Settlement and you have an active payment arrangement with VAC, such as direct deposit, you do not need to do anything to receive payment. If you are claiming on behalf of a deceased veteran of the CAF or RCMP, including as the executor, trustee, administrator of an estate, or a family member, you must submit a Claim Form to KPMG Inc., the administrator responsible for handling claims available at: KPMG Inc.

C/O Disability Pension Class Action Claims Administrator 600 boul. de Maisonneuve West, Suite 1500 Montréal, Québec H3A 0A3 Online: https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/ E-mail: veteranspension@kpmg.ca

For assistance with submitting a Claim Form, please contact the Administrator’s dedicated call center at 1-833-839-0648, available Monday to Friday, 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM (Eastern Time).

The deadline to submit a claim is 19 March 2025. All eligible claimants are entitled to receive legal assistance free of charge from Class Counsel for purposes relating to implementing the Settlement, including preparing and/or submitting a claim to the Administrator.

You may contact Class Counsel for more information or for assistance with filing a claim, at info@vetspensionerror.ca, or 1-866-545-9920. To see the full text of the Final Settlement Agreement, please visit https://vetspensionerror.ca/court-documents/. WHO IS INCLUDED?

The Settlement covers members and former members of the CAF and the RCMP and their spouses, common–law partners, dependents, survivors, orphans, and any other individuals, including eligible estates of all such persons, who received—at any time between 2003 and 2023—disability benefits based on annual adjustments of the basic pension under s. 75 of the Pension Act (the “Class Members”). The terms of the Settlement are binding on Class Members. The Settlement includes releases of claims asserted in the certified Class Action.

WHAT ARE THE AFFECTED BENEFITS?

The Settlement affects prescribed annual adjustments of the following benefits:

• Pension Act pensions for disability, death, attendance allowance, allowance for wear and tear of clothing or for specially made apparel and/or exceptional incapacity allowance;

• RCMP Disability Benefits awarded in accordance with the Pension Act;

• Civilian War-related Benefits Act war pensions and allowances for salt water fishers, overseas headquarters staff,

air raid precautions works, and injury for remedial treatment of various persons and voluntary aid detachment (World War II);

• Flying Accidents Compensation Regulations flying accidents compensation;

• Veterans Well-being Act clothing allowance.

WHAT DOES THE SETTLEMENT PROVIDE?

The Settlement provides direct compensation to Class Members who receive (or have previously received) any of the Affected Benefits listed above, since 1 January 2003. Class Members will receive a single payment of about 2% of all Affected Benefits they have received since 1 January 2003. The total amount of compensation paid by Canada to the Class could be as much as $817,300,000. This is only a summary of the benefits available under the Settlement. The full text of

the Final Settlement Agreement (“FSA”) is available online at https://vetspensionerror.ca/ court-documents/. You should review the entire FSA in order to determine your entitlement and any steps you may need to take to access compensation.

HOW AM I PAID?

Eligible Class Members who are currently collecting VAC-administered disability benefits or pensions will receive a Settlement payment automatically through the same payment method they currently use to collect benefits, including by direct deposit.

Class Members who received Affected Benefits between 2003 and 2023 but who do not have a current payment arrangement with VAC will be required to make a claim with the Claims Administrator. This includes all Class Members who are deceased, and where an executor, estate trustee, administrator of an estate, or a family member is making a claim on behalf of that Class Member.

However, if a deceased Class Member has a survivor who is in receipt of VAC benefits and has a current payment arrangement, that survivor will automatically receive the deceased Class Member’s entitlement without the need to make a claim with the Claims Administrator.

HOW DO I MAKE A CLAIM?

If you do not have an active payment arrangement with VAC, you must submit a claim form with the Administrator.

You must submit a completed and signed Claim Form to the Administrator within the Claim Period. You are encouraged to use the Claim Form submission link available online at https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/. You may, however, submit your Claim Form to the Administrator using one of the following three methods: 1. online at https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca; 2. by e-mail to veteranspension@kpmg.ca; or 3. by mail to: KPMG Inc.

C/O Disability Pension Class Action Claims Administrator 600 boul. de Maisonneuve West, Suite 1500 Montréal, Québec H3A 0A3

You may download a copy of the Claim Form available online at: https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/download/Claim-Form.pdf.

If submitting electronically, the Administrator must receive your completed and signed Claim Form no later than 19 March 2025. If submitting by mail, your completed and signed Claim Form must be postmarked no later than 19 March 2025. For assistance with submitting a Claim Form, please contact the Administrator’s dedicated call center at 1-833-839-0648, available Monday to Friday, 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM (Eastern Time).

Please read and follow the instructions on the Claim Form. Class Counsel are also available, free of charge, to answer your questions and assist you with preparing your claim form.

The deadline to file a claim is 19 March 2025.

AM I RESPONSIBLE FOR LEGAL FEES?

You are not responsible for payment of legal fees. The Federal Court has approved Class Counsel’s fees (including HST) and disbursements to be automatically calculated and deducted from the Settlement amount you are entitled to receive before the payment is issued.

The Federal Court approved payments to Class Counsel equal to approximately 17% of each payment made under the Settlement for legal fees, disbursements, and HST.

The FSA contains additional details about Class Counsel fees, available online at https://vetspensionerror.ca/court-documents/.

Class Counsel are available to assist Class Members through the claims process free of charge.

FURTHER INFORMATION?

For further information or to get help with your claim, contact Class Counsel at: https://vetspensionerror.ca/ or Call: 1-866-545-9920 or info@vetspensionerror.ca

DO YOU KNOW ANY OTHER RECIPIENTS OF A VAC DISABILITY PENSION?

Please share this information with them.

I say it because I love you I

me in touch with my dad, who served for 20 years in the Royal Canadian Navy, including the Second World War and Korea. I think that he, like me, would have been startled to see the misspelling of the word “valour” on the cover of the latest issue (September/October). We prefer the inclusion of the “u,” as it is spelled on the Victoria Cross.

JEANIE DUBBERLEY WINNIPEG

can

sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

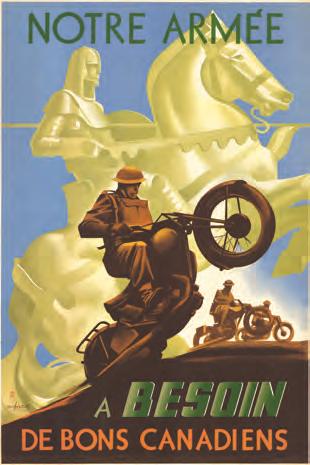

we’re glad to hear you appreciate our work. We deliberately dropped the “u” from valour in this case as “Men of Valor”— valor with no “u”—is the proper name of the poster series (see image above) the story the cover line was referring to is about. Of course, as you undoubtedly know, we otherwise always spell valour with a “u.”

Rock history

I was born in Newfoundland but have lived or worked in almost every province and territory in Canada and, hence, I am a proud Canadian. As such, it never ceases to amaze me how it is that so many Canadian historians exclude Newfoundland from their thinking when they write on matters pertaining to “Canadians.” Admittedly, we Newfoundlanders were late coming to the party, but when we did, I would have thought that our history became Canada’s history. Apparently not, so far as some historians are concerned.

Case in point, the article “Sisters Act” by Alex Bowers (September/October).

Newfoundland was a Dominion during WW I, and hence an equivalent to Canada when it came to

its war efforts, albeit on a much smaller scale. Newfoundland women (including one of my greataunts—Emily Frances Victoria Morry—went overseas as qualified nursing sisters, and many more younger women served as VADs (members of the Volunteer Aid Detachment). Yet, not one word was dedicated to the recognition of these services in this article about Canadian nurses. The author mentions Canadian nurses in Gallipoli, but fails to mention that many of those receiving their ministrations were members of the Newfoundland Regiment, the only North American regiment that served on the battlefields in that campaign. My grandfather, Howard Leopold Morry, was among them. I get it. We weren’t Canadians then. But we are now, and once

Donate Volunteer Register

again, our history is a part of Canadian history and deserves to be treated as such.

Somewhat ironically, in the same edition of Legion Magazine there is a fine article by Michael A. Smith, “The B’ys back,” reporting on the repatriation of Newfoundland’s Unknown Soldier this past July 1. Two entirely different perspectives on Newfoundland’s role in Canadian history.

CHRISTOPHER MORRY ROCKLAND, ONT.

Who’s the villain?

In your latest issue (September/ October), the Heroes and Villains section has James Wolfe opposing Louis-Joseph de Montcalm. It seems to suggest that Wolfe was the hero and Montcalm the villain. Let’s not forget that Wolfe was the one to attack after starving the local population. He did not liberate anyone, instead the British forces oppressed the francophones of New France/Lower Canada/ Quebec in subsequent years. Many historians have since been uncovering Wolfe’s war crimes in Scotland, Gaspé and Quebec. Reading Wolfe’s biography would easily put him in the “villains’’ category. Montcalm’s biography does not report any such account, making him much more a hero.

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham was but one battle in this war covering the known world. Everything was decided at the Treaty of Paris (1763), where territories were ceded, exchanged and swapped not unlike kids trading hockey cards.

You did err in portraying Montcalm as the villain in this instance. History has shown us that winners of a battle are not always heroes.

CLAUDE VADEBONCOEUR SUTTON, QUE.

Exclusive HIGHLIGHT from LegionMagazine.com

It’s no surprise that Legion Magazine readers love history. In particular, the magazine’s On this Date department (see page 12)—which includes select highlight dates for each month—garners a lot of passionate feedback. From omitted events—we can’t include them all!—to additional info—we keep them short to include more of them!—readers regularly let us know what they wanted to see there but didn’t. However, this-day-in-history buffs who aren’t already reading the Military Milestones blog on LegionMagazine.com, will surely want to, as it includes more of

the type of content featured in On this Date. Each week, staff writer Alex Bowers digs into an historically timely Canadian war story, providing detail, context and compelling content. As this issue went to press, for instance, Bowers had recently covered a range of topics from the Canadian military connection to Winnie the Pooh to the 1812 Siege of Detroit, from HMCS Oakville’s daring Second World War attack on U-94 to a Canadian Spanish Civil war veteran, and the life of war chronicler C.P. Stacey to Operation Market Garden. In addition to regular fresh missives from Bowers, Legion Magazine’s

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /newsletter-signup

website has an archive of hundreds of Military Milestones blog entries, hours upon hours of content to satiate even the most ardent of history hounds. Visit www.legionmagazine.com/ category/canadian-military-historyin-perspective/military-milestones/ to explore both the latest and the compendium of collected items. You can also search the thousands of stories on the site. Better still, if you haven’t already, sign up for Legion Magazine’s weekly e-newsletter to keep apprised of the latest blogs, updates and more at LegionMagazine.com. L

November

1 November 1914

Four recent graduates of the Royal Naval College of Canada are among those lost when Germany’s Asiatic Squadron sinks HMS Good Hope. They are Canada’s first naval casualties of WW I.

2-3 November 1951

The Royal Canadian Regiment repels a Chinese attack on Hill 187 in Korea.

4 November 1914

Nurse Margaret Macdonald is appointed matron-in-chief of the Canadian Army Medical Corps. She is the first woman in the British Empire to reach the rank of major.

5 November 1914

Britain and France declare war on the Ottoman Empire.

7 November 1900

Three Canadians are awarded Victoria Crosses for actions during the Battle of Leliefontein in the Boer War.

6 November 1917

Canada and Britain launch an assault on the village of Passchendaele, which is captured by the 27th Battalion late that day.

18 November 1916

Canadian battalions capture Desire Trench on the Somme.

21 November 1916

The largest ship lost in the First World War, sister ship to RMS Titanic, the hospital ship Britannic strikes a naval mine near Greece, sinking within 55 minutes. Thirty die.

11 November 1920

The Cenotaph, the United Kingdom’s official national war memorial, is unveiled. Two unknown soldiers are interred simultaneously in Westminster Abbey and at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

12 November 1981

Space shuttle Columbia launches, carrying the Canadarm.

13 November 1775

Montreal falls to the American Patriot’s Continental Army, led by General Richard Montgomery.

16 November 1857

Under heavy fire, surrounded by dead crewmates, William Hall and his commander use a ship’s gun to free trapped British soldiers near Lucknow, India. Hall is awarded the Victoria Cross.

23 November 2009

During a mortar attack in Afghanistan, Pte. Tony Harris and Pte. Philip Millar run to administer first aid while under fire. Each is awarded the Medal of Military Valour.

24 November 1904

Ross Tilley is born. During the Second World War, Tilley would help redefine plastic surgery while caring for burned and wounded Allied airmen, who called themselves the Guinea Pig Club.

25 November 1953

HMCS Cayuga sails for duty near Korea for the third and final time.

26 November 1940

17 November 1997

Egyptian militants kill more than 60 and injure nearly 100 tourists at an ancient temple in Luxor.

The Toronto Scottish Regiment shoots down a German aircraft in Portslade, England.

28 November 1934

Ten new Atlas aircraft are taken on strength by Canada’s air force.

December

1 December 1959

Twelve countries sign the Antarctic Treaty, declaring the continent a scientific preserve and banning military activity.

2 December 1942

The first controlled self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction is triggered at the University of Chicago, ushering in the atomic age.

3 December 1943

The 1st Special Service Force, the U.S.Canadian commando unit known as the Devil’s Brigade, work to clear German positions on Monte la Difensa, Italy.

4 December 1950

HMCS Cayuga leads six ships on a dangerous night passage to support the evacuation of the port of Pyongyang in North Korea.

6 December 1912

Prime Minister Robert Borden proposes $35 million to help Britain rearm, but the bill is ultimately defeated in the Senate.

10 December 1943

1st Canadian Infantry Division continues its assault across Italy’s Moro River as the first step in a drive on the town of Ortona.

11 December 1941

16 December 1944

Germany launches the Battle of the Bulge, its final major offensive on the Western Front.

17 December 1939

In Ottawa, Canada, the U.K., Australia and New Zealand sign the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan agreement.

18 December 1950

Canada’s first fighting unit— 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry—reaches Korea.

19 December 1813

The British are victorious in a night assault aimed at capturing Fort Niagara in New York.

21 December 1943

2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade, supported by Three Rivers Regiment tanks, enters the town of Ortona, Italy.

23 December 1956

British and French forces leave the Suez Canal after the UN and U.S. force an end to the armed occupation of the region.

Germany and Italy declare war on the United States.

14 December 1915

Arthur Ince is the first Canadian credited with downing an enemy aircraft, shooting a German seaplane near Ostend, Belgium.

15 December 1916

Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd. is incorporated to provide training aircraft for the Royal Flying Corps.

24 December 1944

Minesweeper HMCS Clayoquot is torpedoed by U-806 off Halifax. Eight die while 76 survive.

25 December 1941 Hong Kong surrenders.

27 December 1972

Lester B. Pearson, prime minister from 1963 to 1968 and Nobel Peace Prize recipient, dies.

30 December 1941

Churchill delivers his historic “some chicken, some neck” speech in Ottawa, which helped to galvanize wartime resolve.

31 December 1943

The Royal Canadian Air Force is at its peak with 215,000 people, including 15,000 members of the Women’s Division.

By Alex Bowers

Finding their voices

How a travelling exhibit and writing workshop have enabled veterans and military families to chronicle their experiences

Can you see my Timex watch?” asked Afghanistan War veteran and Canadian Army Corporal Andrew Mullett, “My watch means a lot to me.”

Having once struggled to sleep during his tour of duty, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) soldier recalled placing the timepiece beside his ear and listening to it tick.

The sound, he remembers in a video recorded for posterity, brought great comfort on those difficult nights, evoking memories of his faraway home, his faraway family and the faraway life he had left behind for service: “It was enough to take me away from Afghanistan and focus on something else.”

Meanwhile, Michael Hornburg’s chosen memento for War: In Pieces—a travelling exhibit of written stories by veterans highlighting their individual experiences as former and active military personnel—is a glass of wine never tasted.

“In wellness and good spirits,” the proud father wrote, “I’d talked on the phone to my son for almost a half hour the previous evening from his Forward Operating Base in Afghanistan and he sounded calm and focused.”

Hornburg then chronicled how, after pouring himself a drink the next day, he heard a knock on the door. The wine, discarded on a kitchen countertop, went forever unsavoured as he answered to three Canadian Forces officers.

“How many are the seconds to deliver a few dozen simple words, which contain and shatter a lifetime of befores? Not enough to contain all of eternity.”

Nothing could truly fill the immense chasm opened by Hornburg’s loss. However, in telling his story, he—like Mullett and others—found a new means to channel the memories, unceasingly painful though they remained.

From a bicycle crankset to a single poppy, each item donated to the exhibit—and the often heart-wrenching stories that accompany them—offers an insight into the lives of people shaped by Canada’s military.

The 2014 initiative, a part of the Calgary-based War Stories Society, was the brainchild of founder Melanie Timmons, long a passionate believer in the power of stories and how, at least in the case of some, they may afford catharsis.

Acknowledging that her program is not therapy and emphasizing the merits of professional help,

Timmons explained: “Creating a personal story from events may allow us to take control of those events on our own terms. It is the act of creating a sense of order and producing something tangible— on paper, video or otherwise—from those intangible memories and feelings inside one’s head.”

Focusing on a single object not only hones an author’s ability to express themselves. The practice is also intended to promote empathy with would-be readers and viewers, including attendees of the War: In Pieces exhibit.

“Military women and men are a vital part of our country,” said Timmons, who has no known family connection to the Canadian Armed Forces. “It seems that many civilians have no idea who they are, what their daily lives look like, or what they do to protect us and this nation. In overcoming my own ignorance, I realized that a huge gap existed between Canadian civilian and military communities, and I wanted to do something to help bridge that gap.

“Reading these intimate stories, seeing their related mementoes, allows the public to get to know our military men and women one-on-one.”

Perhaps, too, it affords some storytellers the chance to know themselves.

The success of War: In Pieces prompted Timmons to expand the program to other ventures. In the fall of 2019, she helped kickstart a free veterans’ writing workshop now facilitated by Mike Vernon and Kent Griffiths, both former service members with journalistic backgrounds.

Regardless of experience, aspiring writers can organize, process and find meaning in certain life events. Equally, the nine-month course can enable individuals

to record their military careers for loved ones to learn about.

What prevails is a sense of community in every group and session. Each participant is provided with a safe space to embrace their creativity in an environment defined by constructive feedback and encouragement.

“It’s really across the spectrum in terms of memoir, fiction and more,” noted Vernon of the results. “We’re here to help them find their voice.”

Unfortunately, the initial class encountered a hurdle almost from the start: The COVID-19 pandemic. “That kind of derailed things,” said Vernon, “But it also gave us time to focus on putting together an anthology of the writers.”

Titled A Mile in Their Boots, the since-published book delves deep into a diverse range of military life experiences, including a typical day of basic training, serving at sea, being deployed to another country, facing the challenges of returning from war and dealing with the aftermath of a genocide.

From first to last entry, indeed from first to last page, the writing cohort moves readers with laughter and tears. Nor are they alone in such endeavours.

Beyond the anthology, subsequent classes continue to pour their hearts and souls into writing—something Timmons hopes will continue and signifies the program’s continued growth and outreach to eagerto-write veterans. “My goal is to have free writing workshops across Canada,” she explained.

“Furthermore, Mike [Vernon] has suggested that we create virtual writing programs for those in remote areas. I’d also like to curate and share more of these stories in the form of additional books, public readings, video recordings and pop-up galleries. We just need more resources, and the big challenge is to find the right people to facilitate the workshops and help us move forward.”

Nevertheless, the War Stories Society appears to boast a

strong trajectory, with both the War: In Pieces exhibit and its writing courses generating considerable interest among civilians and veterans alike. It’s what Timmons always wanted.

“Fundamentally, we humans are not so different from one another. When we meet a stranger in a

military uniform on a personal level—through a shared story— we learn how much we have in common. Instead of just saying ‘Thank you for your service’ on Remembrance Day, maybe some civilians will be inspired to start a conversation and get to know these great individuals.” L

For Canadians who are heading south this winter

Unsinkable Sam

One of the epic sea battles of the Second World War, the Battle of the Denmark Strait, was over. HMS Hood was at the bottom of the sea; a stricken HMS Prince of Wales was limping back to port. The German battleship Bismarck, disabled by a relentless barrage from British ships and aircraft, had been scuttled and sunk.

It was May 27, 1941, and after eight days and multiple torpedo strikes from Swordfish biplanes of the Fleet Air Arm along with over 400 hits from Royal Navy guns, just 114 of Bismarck’s 2,200plus crewmen would survive.

One hundred fourteen, that is, and one cat.

HMS Cossack, a Tribal-class destroyer that had joined the hunt for Bismarck during the battle’s preliminaries, was now, in its aftermath, hunting for German survivors to rescue. They found none, but for a lone, soggy cat afloat on a wooden board.

As wartime combatants are wont to do, the swabbies aboard Cossack rescued the frayed

feline, adopted him, and named him Oscar—derived from the International Code of Signals designation for the letter ‘O,’ code for “Man Overboard.”

Oscar—or the German “Oskar,” as some prefer—sailed with Cossack’s crew on convoy duty between Gibraltar and the United Kingdom for five months until the destroyer was torpedoed by U-563

Taken under tow, the heavily damaged ship sank in a storm two days later; 159 of 190 crew died. Oscar survived and became Unsinkable Sam, the black-andwhite ship’s cat of the British aircraft carrier Ark Royal

The relationship didn’t last.

Just two-and-a-half weeks later, the big flattop was sailing for Malta when it was torpedoed and sunk off Gibraltar by U-81. One sailor was killed.

Sam was found by a motor launch, clinging to a floating plank. Described by author William Jameson as “angry but quite unharmed,” the cat with at least three lives was eventually taken aboard HMS Legion, which

happened to be the same ship that rescued the Cossack survivors.

Thus ended the seagoing career of Unsinkable Sam, ship’s cat. He landed in the offices of the governor of Gibraltar, then was taken to the U.K. where he spent a sedate life in the Home for Sailors, a seamen’s retirement residence in Belfast. Sam died in 1955.

Or so the story goes.

Some have questioned whether Sam’s adventurous saga might be the stuff of sea stories—shreds of truth laced with fiction.

The skeptics point to the fact there are pictures of two different cats identified as Sam— or Oscar, as the case may be.

One, says the Royal Museums Greenwich, shows “a tabby claimed to be him and the other a blackand-white cat but clearly wearing a collar tag with the inscription ‘HMS Amethyst 1949’ (which would make that cat ‘Simon,’ not ‘Oscar’).

“Allowing a degree of confusion, however, there is no suggestion ‘Oscar’ was an official mascot on ‘Bismarck’ (so possibly aboard as an illicit crew pet) and no reason for the artist to have done this portrait if he was not.”

Simon, by the way, became ship’s cat aboard HMS Amethyst, a sloop-of-war, after a sailor found him wandering the dockyards of Hong Kong in March 1948.

The People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals awarded Simon the Dickin Medal for gallantry (known as the animal Victoria Cross) in April 1949 after he was wounded by shrapnel during the Yangtze Incident, in which Communist rebels blocked Royal Navy access to China’s

Yangtze River during the Chinese Civil War and opened fire.

An artillery round tore through the captain’s cabin, seriously wounding Simon and his skipper, Lieutenant Commander Bernard Skinner, who died soon after.

Simon climbed out of the cabin wreckage onto the ship’s deck, where he was picked up and taken to the sick bay. The cat was not expected to last the night. Simon nevertheless survived and killed off a rat infestation—which was the primary role of ship’s cats, generally, since time immemorial.

Simon became an instant celebrity, lauded in newspapers the world over, and was the only feline ever to earn the Dickin.

He also received the Naval General Service Medal and was given the fanciful rank of Able Seacat after dispos-

SIMON NEVERTHELESS SURVIVED AND KILLED OFF A RAT INFESTATION.

at an animal centre in Surrey, where he contracted a woundrelated virus and died. Hundreds, including Amethyst’s entire crew, attended his funeral at the PDSA Ilford Animal Cemetery in East London.

His tombstone declares that “throughout the Yangste Incident, his behaviour was of the highest order.”

ing of a particularly vicious rat known as “Mao Tse-tung.”

He received thousands of letters—so many that a lieutenant, Stewart Hett, was appointed “cat officer” to deal with the flood. Simon was honoured at ports of call during Amethyst’s journey home, and a special welcome was made for him upon the ship’s arrival at Plymouth in November. Alas, as was protocol, Simon had to serve time in quarantine

There is apparently no such tribute to or record of Unsinkable Sam. Official documents and histories of the day make no mention of a cat.

The convictions of avowed cat people notwithstanding, the fact that U-boats were known to be lurking after the Battle of the Denmark Strait, forcing Allied vessels to cut short their rescue efforts, casts some further questions as to whether the Cossack crew would have taken the risk, time and effort to save a cat. L

War games

Canada’s posturing toward Chinese aggression could be too late

This past July, Canada and Australia issued a joint memorandum declaring that they would increase naval co-operation in the Pacific for the express purpose of pushing back against Chinese naval expansion. It’s a significant step away from the pretend neutrality that Canada presented the world amid growing confrontation between China and just about every country that borders on the South China Sea.

The announcement from the two nations was not a CanadianAustralian version of AUKUS—the Australian, U.K. and U.S. agreement to pool resources to help the former acquire a small fleet of nuclear submarines sometime in the 2030s.

China currently has the largest navy in the world and there’s no sign of it slowing its growth as the country looks to add a flush-deck aircraft carrier with a magnetic aircraft

launcher to its fleet. And if the country’s ongoing confrontations with the Philippines near the Spratly Islands signify anything, it’s that nothing will stop the country that Napolean supposedly called “the sleeping dragon” from continuing to claim the entire South China Sea as, in effect, its own internal waterway.

Canada has never agreed with the Chinese on that position and continues to claim that the sea is an international waterway and must be open to ships of all countries. But Canada, unlike the U.S., Britain and other countries, has only whispered that position.

This past June, in fact, Global Affairs Canada released a statement condemning “the dangerous and destabilizing actions” of China, indicating the country isn’t following its obligations with regard to international law.

However, mildly worded statements from a country with relatively few military resources in the area don’t seem to faze the Chinese.

Canada’s recent muscle flexing in relation to who owns what in the far Pacific amounts to shifting a single 30-year-old Halifax-class frigate, HMCS Max Bernays, from Canadian Forces Base Halifax to CFB Esquimalt.

When a Canadian warship has occasionally sailed through the Taiwan Strait it was claimed by Ottawa, until recently, that the vessel was merely taking the most direct passage from point A to B. Only in the last two or so years has the Royal Canadian Navy admitted that these sea passages are done for the purpose of asserting that the waterway is international territory.

Although the Australian and Canadian navies are roughly the same size (even though Canada’s population is larger by about 12 million), the Australians take their naval and air resources far more seriously.

For example, Canada has four 1980s-era, British-built submarines, but it’s rare to have two of

them at sea at any one time. The Australians opted to build their own six Collins-class submarines, and while those boats suffer from constant mechanical challenges themselves, at least Australia is moving toward the acquisition of a nuclear-powered option.

While Canada faces the unique challenge of the ice-covered Arctic Ocean, only recently did it announce that it would be looking at trying to acquire a dozen non-nuclear submarines with under-ice capabilities during the next decade. Several other nations—Germany, Israel, Japan, South Korea and others—operate so-called nonnuclear AIP submarines (with air-independent propulsion, hence the acronym) that can remain submered for two to three weeks. Of course, there’s the ongoing debate whether such boats will give Canada the Arctic capacity it needs.

Canadian naval expansion is still much more a dream than a reality. The new Arctic offshore patrol ships have had several major problems, which isn’t promising since only three of the multimillion-dollar vessels have been completed and they only have a 12-month warranty. Meanwhile, the Canadian surface combatant warships that are slated to replace the Halifax-class frigates exist only on paper, and their cost has ballooned even before any steel has been cut. Officials originally said the 15 vessels would cost $26 billion to build, but in June 2024, Parliamentary Budget Officer Yves Giroux estimated the project would total $84 billion. Still, National

Legion and Arbor Alliances

Defence now maintains it will cost no more than $60 billion.

In July, Canada, the U.S. and Finland announced they would form a consortium to build new icebreakers to counter an ambitious Chinese program to develop the vessels. Indeed, this past summer, China dispatched three new icebreakers to the Arctic.

It’s good that Canada is finally recognizing a new world order and threats to the Great White North. The key question: can Canada’s naval program catch up? L

Check out David J. Bercuson’s new book, Canada’s Air Force: The Royal Canadian Air Force at 100, available now from University of Toronto Press.

OVERLOOKED

By Stephen J. Thorne

A TRIO OF COURAGEOUS ACTS OF WAR LEFT UNRECOGNIZED

For the rank-and-file soldier, the grunt, the bloody conduct of war is, aside from the killing, the abject waste and devastation, a noble endeavour, the personification of altruism, the ultimate act of selflessness.

History is replete with stories of battlefield daring and medalearning exploits. Recognition for outstanding acts of courage, innovation and sacrifice serves as reward, inspiration and a source of national pride.

The celebrated would tell you they didn’t do what they did for honour, country, or some lofty ideal. They would likely say they did it for their fellow soldiers, their comrades-in-arms, their brothers. Medals and plaudits don’t factor in the equation when it’s do or die.

Rarely by their own choosing, the doers of these deeds are exalted as national heroes, their faces and accomplishments fodder for recruitment campaigns and bond drives, their stories the subject of poetry and prose, song and cinema.

The best of them count themselves lucky, meeting their praises with the humility of those who know better, who understand what it is to kill and to survive, who count their idols among those lying in the hallowed soil of faraway fields bearing names such as the Somme, Ypres, Hong Kong, Normandy, Groesbeek, Busan.

For some, medals are haunting reminders of ordeals they would rather forget.

They know well, too, that for every Victoria Cross or Medal of Honor, pour tout les Croix de guerres, Soviet orders of Victory and Glory, and German Knight’s Crosses of the Iron Cross, there have been countless others in countless wars whose actions in the face of a hostile enemy went unrecognized and unrewarded.

Humans are flawed, and politicians, bureaucrats and military

brass are certainly no exceptions. The distribution of what British Tommies dismissed as “gongs” and American G.I.s called “chest candy” has never been a pure and unadulterated process.

Historically, factors such as race, rank, politics, quotas, location, service branch and inconsistent and arbitrary standards have all influenced decision-making.

The most recently notorious case is that of Private Jess Larochelle, an Ontarian whose magnificent defence of a strongpoint in Afghanistan earned him Canada’s second-highest award for valour, the Star of Military Valour.

His story spawned a campaign to upgrade his award to a Victoria Cross, which was refused primarily on technical grounds. The Canadian VC has never been awarded since it replaced the British version in the 1990s.

Still suffering the effects of wounds he sustained during the Oct. 14, 2006, firefight, through which he was left alone to defend a forward position, Larochelle died in 2023.

The following are the stories of three other unsung Canadians whose actions in historical wars merited more recognition than they received.

Factors such as race, rank, politics, quotas, location, service branch and inconsistent and arbitrary standards have all influenced decision-making.

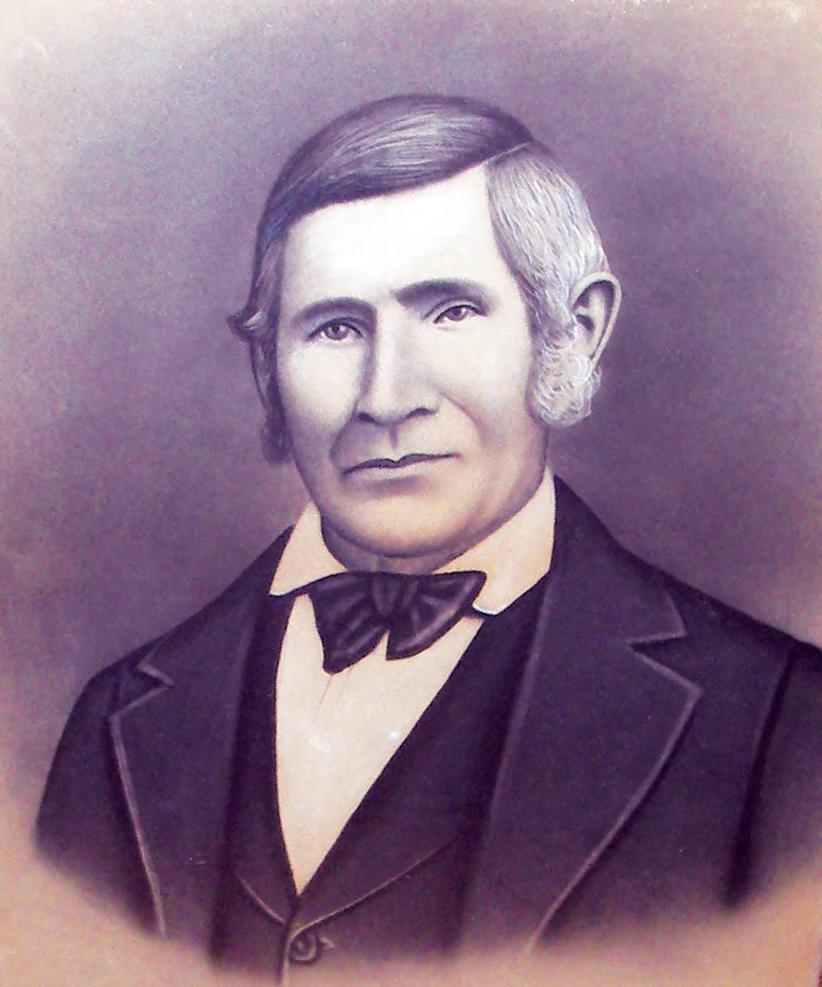

WILLIAM (BILLY) GREEN

On May 27, 1813, American invaders crossed the border into Upper Canada and captured Fort George, less than two kilometres from what is now Niagara-onthe-Lake, Ont. The War of 1812 was less than a year old and the outcome was anything but certain.

Led by British Brigadier-General John Vincent, the fort’s defenders withdrew and encamped about 70 kilometres away at Burlington Heights. Two U.S. brigades set off in pursuit, pitched a roadside camp at Stoney Creek, Ont., and began planning their attack. It was June 5 and Vincent’s troops were about 15 kilometres away.

That evening, U.S. soldiers detained a local farmer, Isaac Corman, for refusing to tell them where local Indigenous warriors

were encamped. They brought him to the American lines near the beach on Lake Ontario. Corman, however, managed to convince some of the U.S. officers that he was a cousin of American Major-General William Henry Harrison, commander of U.S. forces in the northwest.

The gullible Yanks released Corman, who then requested the countersign, or password, so that he could get past the American sentries and go home. They gave it to him—Wil-Hen-Har, after the majorgeneral—and sent him on his way.

Meanwhile, Corman’s wife had reported him captured and her brother, William Green, had already set out to find him.

Known as Billy Green the Scout, the 19-year-old farm boy was born and raised in Stoney Creek, the son

of an Empire Loyalist who had left the United States around 1792.

When the brothers-in-law met on the road outside Stoney Creek, Corman told Green of the American plans and gave him the countersign. The Americans soon discovered Corman’s ruse, however, and promptly recaptured their escapee. Green was already on his brother Levi’s horse “Tip” headed for Burlington Heights to warn the British of the impending attack.

Arriving at the British encampment, he was taken for a spy, detained and interrogated by Lieutenant-Colonel John Harvey, who soon deduced the kid was legit. Acting on Green’s intel, the password he provided, and his intimate knowledge of the countryside, Harvey formulated a plan to launch a nighttime ambush on the American camp. He gave Green a sword and asked him to guide his troops through the fog-enshrouded forest.

They set out just before midnight, encountering their first American sentries at Davis’ tavern in Big Creek. The Americans fired their muskets and fled. The British force stumbled upon more sentries along the way. Green gave one the countersign and dispatched him with his sword. Green stayed with the British troops as they mounted the attack, seized artillery pieces and captured senior American officers. The Americans who could, fled. Green’s contribution was undoubtedly pivotal to the British

After the Americans captured Fort George in Upper Canada, William Green passed critical info about their continuing advance to the British. He fought with the red coats during their subsequent victory at the Battle of Stoney Creek.

victory. But his story has been both questioned and grossly enhanced. Despite much gilding of the lily, however, he never achieved the renown of his contemporary, Laura Secord. Indeed, embellishments of his role during the last 200-plus years have not served him well.

The March 12, 1938, edition of the The Hamilton Spectator called him “the Paul Revere of Canada,” claiming he “sighted the American army massing below the mountain at Stoney Creek” and “felt it his duty to inform the English troops of their nearness.”

“This is a fabrication, as the British knew exactly where the Americans were, and knew they were being pursued by them,”

Philip E.J. Green wrote in an exhaustive analysis and defence of Billy the Scout’s story published in the May 2013 edition of The War of 1812 Magazine

Green the writer said such myths have fuelled theories that the whole story is a fanciful lie. After-action reports by British and American officers make no mention of either Green or Corman, bolstering the case to discredit the story.

But Laura Secord’s role in the British victory won by Indigenous forces at the Battle of Beaver Dams two weeks later was never acknowledged in official reports either.

Secord had overheard American officers at Queenston discussing plans to attack a smaller British force under the command of Lieutenant James FitzGibbon. She then walked some 30 kilometres on a circuitous route through rugged terrain to warn FitzGibbon, who subsequently dispatched Captain Dominique Ducharme, in command of First Nations warriors, to address the matter. They won a quick victory and Secord has chocolates named for her.

Green’s contribution was undoubtedly pivotal to the British victory. But his story has been both questioned and grossly enhanced.

“The primary sources of evidence used to establish the story of Laura Secord are the personal accounts of Laura Secord herself,” wrote Green, whose relation to Billy the Scout, if any, is unclear.

FitzGibbon wrote a certificate 24 years later, in which he said Secord did “acquaint” him with the Americans’ intentions. Mohawk Chief John Norton wrote in his diary that “a loyal Inhabitant brought information that the Enemy intended to attack us that night with six hundred men,” but doesn’t name the inhabitant.

There are several accounts by British and American officers of the Battle of Stoney Creek—and the events preceding it. “As with Secord, none of them mention Billy Green,” the author wrote. “Nor is there a certificate describing his role in the action.

“There are no accounts written by Billy Green himself; he was an illiterate.”

And, notes Green the author, Billy had reasons to stay silent about his role at the time, not the least of which was to avoid unwanted attention from the Americans.

Years later, the local justice of the peace, Peter Van Wagner, mentioned Green in his diary shortly after the scout died. He related the remorse Dr. Thomas Picton Brown said his patient, Billy Green, expressed over killing an American

sentry. The sentry had just fired his single-shot musket and was thus, in Green’s mind, unarmed.

“In a charge on a picquet [sentry] he run a man through who had an empty gun without a bayonet,” wrote Van Wagner. “This was related to me by Dr Brown as he attended Green in dangerous illness where he told the doctor he was very sorry for what he had done, for he knew the US soldier was defenceless for he had seen him discharge his piece.”

Green the author says the scout’s own telling of the events of that night jibes with the general accounts contained in official reports, bolstering the validity of his story. The military accounts weren’t published until decades later and, regardless, could not have been read by the illiterate Green.

The corporal’s sword that Green is believed to have wielded was passed down through four generations of his family and is now in the collection of the Stoney Creek Historical Society’s Reference Library and Archives.

Still, the myths have persisted, fed by the likes of this gem from a 1938 edition of The Mail and Empire newspaper: “And so Canada remained British…due to the cool-headed, yet audacious courage of Billy Green, the farm lad who was God’s instrument in saving Upper Canada.”

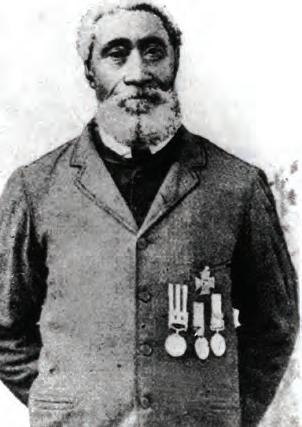

JEREMIAH JONES

Jeremiah Jones, a Black man from East Mountain, N.S., fought Germans in the trenches and racism on Parliament Hill before he finally received muted recognition for his courage decades after he helped Canada win the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

The six-foot-two private was already 58 years old by the time he reached the front in February 1917 as a member of The Royal Canadian Regiment. Two months later, he crossed the bloody battlefield at Vimy and took an enemy machine-gun nest.

Not only did he contribute to a notable victory of the First World War, but the humble giant (the average enlistee measured 5' 6") proved a Black man’s worth in a white man’s army.

“I threw a hand bomb right into the nest and killed about seven of them,” Jones recalled years later. “I was going to throw another bomb when they threw up their hands and called for mercy.”

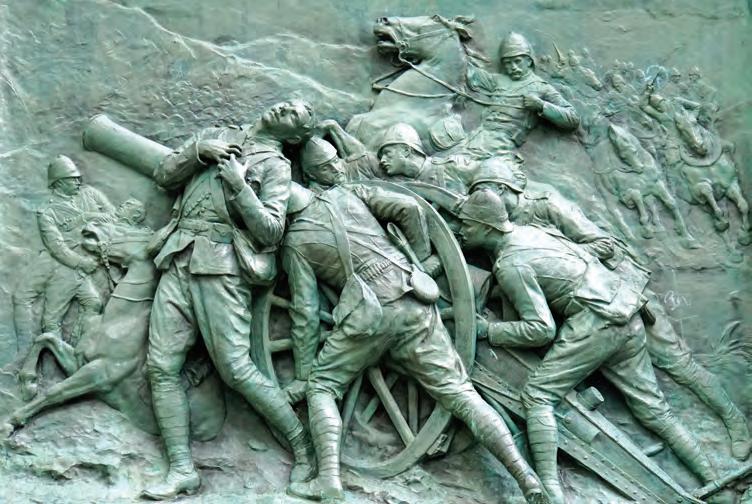

A mortar shell explodes amid trenches on Vimy Ridge in May 1917. Jeremiah Jones was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions during the battle.

Black enlistment. “Coloureds,” they said, wouldn’t make good soldiers.

Blacks had been trying to enlist in the Canadian forces without success. In Saint John, N.B., 20 Black volunteers had no place to serve. “It is a downright shame and an insult to the race,” John Richards, a Black community leader, wrote to federal officials.

Jones ordered the half-dozen survivors out of their hole, then marched them at bayonet-point back to the Allied lines, carrying their weapon. He had them deposit the machine gun at the feet of his commanding officer.

“Is this thing any good?” he asked.

His exploits that day earned him acclaim at home and abroad, but they remained the subject of debate from London to Ottawa for almost a century.

By Aug. 17, 1917, his hometown newspaper was celebrating Jones as “a patriot, brave, powerful and resourceful.” His commander recommended him for a Distinguished Conduct Medal, the second-highest valour award after the Victoria Cross at the time.

But “the lion of the hour” was Black, and to give a Black man a bravery medal in 1917 would have been a political bombshell at a time when the military’s top brass—and some senior politicians—opposed

The response was unequivocal. An officer in Victoria said no white battalion would take Blacks. In Halifax, whites withdrew voluntary enlistments when rumours circulated that they might have to serve with Blacks.

“Neither my men nor myself, would care to sleep alongside them, or to eat with them, especially in warm weather,” wrote LieutenantColonel Walter H. Allan of the 106th Overseas Battalion, which eventually enlisted Jones by order of the federal government.

The matter was debated in Parliament before the military chief of staff issued a memorandum on April 13, 1916, citing what he called the facts.

“The civilized negro is vain and imitative,” wrote Major-General Willoughby Gwatkin. “In Canada he is not being impelled to enlist by a high sense of duty; in the trenches he is not likely to make a good fighter.”

Such attitudes were not limited to matters of military service. The longheld belief among some that racism

Jones was finally recognized on Feb. 22, 2010, when Ottawa posthumously awarded him the Canadian Forces Medallion for Distinguished Service.

was not widespread in the Great White North has been misplaced.

“The treatment received by ‘visible’ Canadians did not originate with the military,” James Walker, a leading scholar of Canadian race relations and Black history at the University of Waterloo, wrote in a 1989 paper.

“Recruitment policy and overseas employment were entirely consistent with domestic stereotypes and ‘race’ characteristics and with general social practice in Canada…. Racial perceptions were derived, not from personal experience, but from the example of Canada’s great mentors, Britain and the United States.”

All this, despite the fact another Black Nova Scotian, Royal Navy gunner William Hall, was awarded a Victoria Cross for his actions at the 1857 Siege of Lucknow during the Indian Rebellion, in which he and an officer continued firing their 24-pounder after the rest of the gun crew had been killed or wounded.

There was righteous indignation among Blacks and whites alike over the rejections of Black volunteers in the early days of WW I.

As early as November 1914, Arthur Alexander of North Buxton, Ont., told Militia and Defence Minister Sam Hughes that “the coloured people of Canada want to know why they are not allowed to enlist in the Canadian militia.

“I am informed that several who have applied for enlistment in the Canadian expeditionary forces have been refused for no other apparent reason than their colour.”

On Sept. 7, 1915, George Morton of Hamilton wrote Hughes “on a matter of vital importance to my people (the coloured), in reference to their enlistment as soldiers.”

Morton wanted to know if Ottawa had an official policy on enlistment of “coloured men of good character and physical fitness.”

“A number of coloured men in this city, who have offered for enlistment and service, have been turned down and refused, solely on the ground of colour or complexioned distinction,” he wrote.

“A number of leading white citizens here, whose attention I have drawn to this matter, most emphatically repudiate the idea as being beneath the dignity of the Government to make racial or colour distinction in an issue of this kind.

“They are firm in their opinion that no such prohibitive restrictions exist.”

Hughes issued a directive confirming and attempting to rectify Morton’s assertions shortly afterward. But it didn’t seem to matter. By Dec. 31, at least 200 Black Canadian volunteers had been rejected.

Allan’s 106th eventually took on 18 Blacks, but most, including Jones, were reassigned once overseas. Jones, who had lied about his advanced age to get in (he said he was 38), went to a reluctant Royal Canadian Regiment.

There, he more than proved his worth.

“Jeremiah Jones put the lie to perceptions of the day,” the late author, historian and eventual senator Calvin Ruck told The

Canadian Press in 1995 amid a campaign by the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia to recognize the soldier’s contributions.

“His actions served to change the view of the ability of Blacks under fire,” said Ruck. “He showed people Blacks could be as good soldiers as anybody else and the majority community didn’t have a monopoly on bravery or devotion to duty.

“Blacks were just as proud and as loyal to king and country.”

The centre’s campaign, however, stalled in Britain that same year.

“Regardless of the right and wrong of the perceived or real discrimination against Blacks in the Canadian Army, there can be no question of a retrospective award,” wrote Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Bird of the British Defence Ministry.

“State awards for both gallantry and meritorious service are announced within a year or so of the citations to which they refer. There were many servicemen like Jones who did not receive recognition for their gallant deeds.”

Jones’ lack of recognition is particularly galling given the number of VCs handed out for the taking of machine-gun positions during WW I, especially given the fact that the private did it solo, took prisoners, and brought back the gun.

But Ruck didn’t give up, and his efforts ultimately paid off—somewhat.

Jones was finally recognized on Feb. 22, 2010, when Ottawa posthumously awarded him the Canadian Forces Medallion for Distinguished Service, which wasn’t created until 1989 and was intended for individuals and groups who aren’t active members of the Canadian Forces.

It was no DCM, but it was a measure of recognition.

Jones returned to Truro, N.S., at war’s end, rejoined his wife Ethel and lived out his life as a woodsman, farmer and handyman. They had a large family. Jones died in 1950.

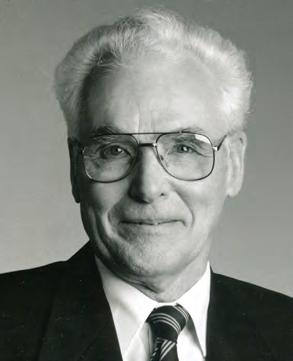

FLIGHT LIEUTENANT JAMES ANDREW WATSON

On the night of April 27-28, 1944, Lancaster R-ND 781/G of 622 Squadron, Royal Air Force, piloted by Flight Lieutenant James Andrew Watson of Hamilton, Ont., set out from England on a bombing mission to Friedrichshafen, Germany.

R-ND would never reach its target but, like Jess Larochelle 80 years later, Watson’s heroic actions that black night over occupied territory would inspire an unsuccessful campaign to award him a Victoria Cross—posthumously.

The seven-member crew—three RAF, four Royal Canadian Air Force—were at 6,000 metres (27,000 feet) as they approached the turning point, 30 minutes out, for their final run into the target. Suddenly, they were attacked from dead astern and below by three Junkers Ju 88 night fighters. It was about 1:30 a.m. and they were a little south of Strasbourg, France.

“The attack was a complete surprise, there was no moon, just complete darkness,” recalled Ron Hayes, the bomber’s midupper gunner. “The aircraft was equipped with H2S radar equipment which transmits pulses and the crew and Intelligence were not aware at the time that the Germans were able to home in on the signal.”

The crew could hear the thuds as the German rounds hit the rear of the aircraft and they saw flashes as the port elevator badly buckled. The rear gunner, RCAF Flight Sergeant Murdock MacKinnon—a Cape Breton native living in Somerville, Mass., when he signed up—later reported that his radio and turret were knocked out.

Flight Lieutenant James Watson poses with his Lancaster crewmates.

RAF Sergeant Roy Clive Eames, flight engineer, said the initial attack had also penetrated the plane’s nose and knocked out its aileron and rear controls. With MacKinnon out of commission, Hayes directed the pilot’s evasive actions. But they were essentially flying blind. From his vantage point atop the Lanc, Hayes couldn’t see their attackers’ approaches and had to make his calls based on the disconcerting volume of tracers arcing past his canopy.

Watson began corkscrewing as the attacking aircraft came closing in again from 350 metres. Hayes described his pilot’s response to his evasive directions as magnificent, but still the bomber was hit in the starboard inner engine. Within 30 seconds, the wing and engine were burning. The fire extinguisher system had no effect.

Watson, at 21 among the eldest aboard and flying his 17th mission, side-slipped the big, lumbering plane to keep

the flames at bay. But the manoeuv re amounted to a trade-off—the fire didn’t reach the crew, but they were losing altitude fast.

“During this time the captain asked the navigator to inform the crew of our position for the purpose of escape,” MacKinnon reported later. “The navigator told us we were approximately on the French border.

“There was at no time any suggestion of panic and this was largely due to the coolness and perfect calm of our captain.”

Throughout the combat, Watson repeatedly asked for news of the rear gunner, with whom he had flown all his missions, and assured the rest of the crew that he would look after him. “Whatever happens, he’ll be OK,” the pilot assured them.

“I then plugged into the intercom system and informed the pilot that…the rear gunner was still in his turret and I would let him know we were getting out,” said Hayes. “The captain’s last words to me were: ‘Yes, OK, but hurry, we’re at 4,500 feet; if he’s not hit he might make it. So long Ron, good luck.’”

Hayes, just 19 at the time, then opened the bulkhead door leading to the rear turret. MacKinnon turned his head and Hayes patted his parachute. The rear gunner turned away without acknowledging the news.

“The aircraft was now at about 4,000 feet when I bailed out,” Hayes said. “The pilot had the aircraft under perfect control, it was still losing height in a sinking fashion and the flames had enveloped the fuselage alongside the burning wing.”

“It is quite clear, that Flt.-Lt. Watson sacrificed his life knowingly and willingly to ensure the safety of his crew.”

At the words “he’ll be OK,’” Eames said in a statement filed July 25, 1946, he realized “with horror…that Flt.-Lt. Watson would not leave that aircraft while there was the slightest doubt that a member of the crew remained [inside] and as a last resort would attempt a crash landing to save that member of his crew.”

As the fuselage seam aft of the burning engine began melting, Watson directed the crew to collect their parachutes. Soon, the wing was almost totally engulfed, and a gaping hole was forming in the side of the plane.

“I’m sorry lads,” said Watson, “but you’ll have to hit the silk.”

In a report on the incident filed May 6, 1945, weeks after they were freed from German prison camps, MacKinnon said the Lancaster was badly damaged. Without intercom, he said he was “entirely ignorant of proceedings” until Hayes appeared.

“Starboard elevator in tail shot off,” reported MacKinnon. “Navigator [Flying Officer William Ransom of Hamilton] stated pilot was last seen holding stick hard to port.

“When I baled [sic] out the aircraft was a blazing mass in a dive so it seems impossible that pilot got out. I baled [sic] out when flames were passing rear turret.”

As Ransom took his turn at the escape hatch, the third to go, he took one last look at Watson, whom he said was having “difficulty maintaining the aircraft in level flight.”

“Leaving the aircraft and releasing my parachute, I was able to watch the burning aircraft almost until it crashed,” Ransom later wrote. “It remained level, latterly, and in a shallow dive for much longer than would have been necessary for F/L Watson to reach the escape hatch and bailout, a fact which leads me to believe that he remained at the controls in order to allow the rear gunner, whom we were all under the impression was injured, as much time as possible to clear his turret.”

MacKinnon, he later learned, got clear “just in time to have his fall checked by his parachute, before reaching the ground.”

Hayes, who had directed Watson through the attack, landed hard in an open field. He blamed the impact on his low-level escape, a disconcerting delay in the deployment of his ill-serviced parachute, and a lack of instruction in its use.

“The action with the German fighter aircraft, the difficulty in evacuating our aircraft and the bale-out [sic] and hard landing in the dark were very stressful experiences, and the right side of my body and lower back [were] aching,” he said.

Dizzy, Hayes rested for a few hours where he had landed, out in the open.

As daylight approached, he rose to search for a hiding place in a wood or a barn, but the pain was so bad he only managed to make it to a nearby ditch, where he was discovered by a local and taken to the village of Guémar.

He was interviewed by a young girl who could speak some English before he was taken to the village hall around 1 a.m. on April 28.

“Here I met a French Schoolmistress, Mme. Lousie Strohl, who gave me tea, biscuits and tobacco, then she told me that Flight Lt. Watson had been found dead at the controls of the aircraft. She went to some length in describing him, even saying he was a Canadian and that he had two stripes on his epaulettes.

“This lady was sympathetic and wanted to cheer me up and make me feel at home, even though she could not help me escape. The village hall had become crowded with the local inhabitants who might have helped me escape if it was not for their fears of the Gestapo.”

A pair of Luftwaffe intelligence officers took Hayes to Colmar, France, for interrogation.

“After the usual questions, I was asked if I could help them in identifying the belongings of a dead pilot,” he said. “The items were those of Flight Lieutenant Watson in an envelope, consisting of his identification bracelet and a ring.

“I knew that the ring had been given to Jimmy Watson by his father. The Germans said that they had taken the articles from a…pilot who was found dead in the pilot’s seat of a Lancaster. I said nothing to them for fear that it might be the beginning of a long interrogation and I also knew that the identity bracelet was sufficient.”

Hayes surmised that Watson had died trying to save the rear gunner, MacKinnon. At Colmar, he saw three of his crewmates, but they didn’t speak to each other in case the Germans were listening.

Eames and Hayes were taken to Stalag Luft VI, while officers Ransom and W.H. Russell were separated. On the way to the prisoner-of-war camp, Eames told Hayes he had seen MacKinnon.

“Seeing him gave me a severe shock as I had convinced myself that he had been killed,” reported Eames.

In fact, all six crew who had escaped the burning plane had miraculously survived and were liberated in the spring of 1945. Hayes, an Englishman, would immigrate to Canada in 1951, largely based on the impressions left by his Canadian crewmates.

In a letter written while still a PoW in January 1945, Ransom asked his father, a padre at the Canadian Army Trades School, to “please see Jimmie’s folks and give them my deepest sympathy. He died like a hero in the fullest meaning of the word.

“He reached the ultimate in courage and devotion to duty that a bomber skipper can reach in that he gave his life that his crew might live, and he was successful, as all of us are safe. I am looking forward to meeting the parents of the grandest guy I’ve ever known—when this war is over.”

Eames called Watson “the bravest and coolest fellow I have ever met,” adding “we all owe our lives to him.”

In 1946 and 1947, five members of the crew put forward recommendations for the Victoria Cross to be awarded to their skipper.

“I firmly believe it would be impossible for an aircraft, in as badly damaged condition as was ours, to remain in such an attitude of flight without any assistance from the controls,” reported Ransom, who had flown many missions with Watson.

“I am convinced that on this occasion he unhesitatingly made his decision and at the cost of his own life remained at his post to ensure that his crew would have every possible opportunity and every valuable second of time to abandon the aircraft and save their lives.”

“It is quite clear,” said MacKinnon, “that F/L Watson sacrificed his life knowingly and willingly to ensure the safety of his crew. His most courageous act,

his great and noble sacrifice in the face of the enemy was beyond the highest ideals of his duty and merits the highest possible award for gallantry and for valour in the face of the enemy.”

Watson’s nomination for a Victoria Cross, however, went nowhere. He received only a Mention in Dispatches, one of an untold number of bomber pilots who died saving their crew and were never given their due.

Except two: a British Halifax pilot named Cyril Joe Barton, and a Canadian.

Squadron Leader Ian Willoughby Bazalgette, a Lancaster pathfinder pilot from Calgary, was posthumously awarded a VC after pressing home his Aug. 4, 1944, run into a target near Senantes, France, in a mortally damaged aircraft.

With his bomb aimer gravely wounded, Bazalgette successfully marked the target for the rest of the attacking squadron, then kept his flaming bomber from crashing into a nearby village and ordered those of his crew who could to parachute to safety.

The 25-year-old pilot, who had earned a Distinguished Flying Cross in Italy a year earlier, subsequently managed a belly landing, but the plane then hit a ditch and exploded. Bazalgette and two wounded crewmates were killed.

“That the attack was successful was due to his magnificent effort,” said his VC citation, published 10 days after he died. “His heroic sacrifice marked the climax of a long career of operations against the enemy. He always chose the more dangerous and exacting roles.

“His courage and devotion to duty were beyond praise.”

James Watson got no such acclaim. He’s buried close to where he died—at Choloy War Cemetery at Meurthe-et-Moselle, France. His family attended a 2009 ceremony when a monument was dedicated to Watson near the crash site in Saint-Hippolyte, France. L

Belleville Brockville Clarington Durham Region Cornwall

Etobicoke Georgina Innisfil Kingston London Mississauga Northumberland North Bay Orillia Ottawa

samurai The Canadian

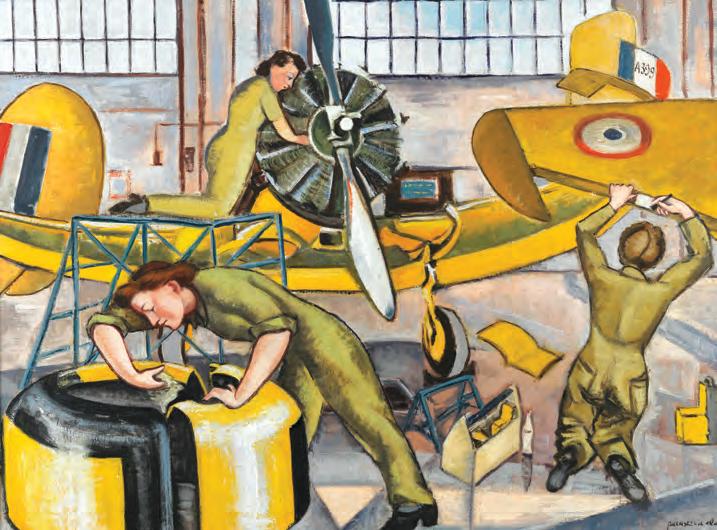

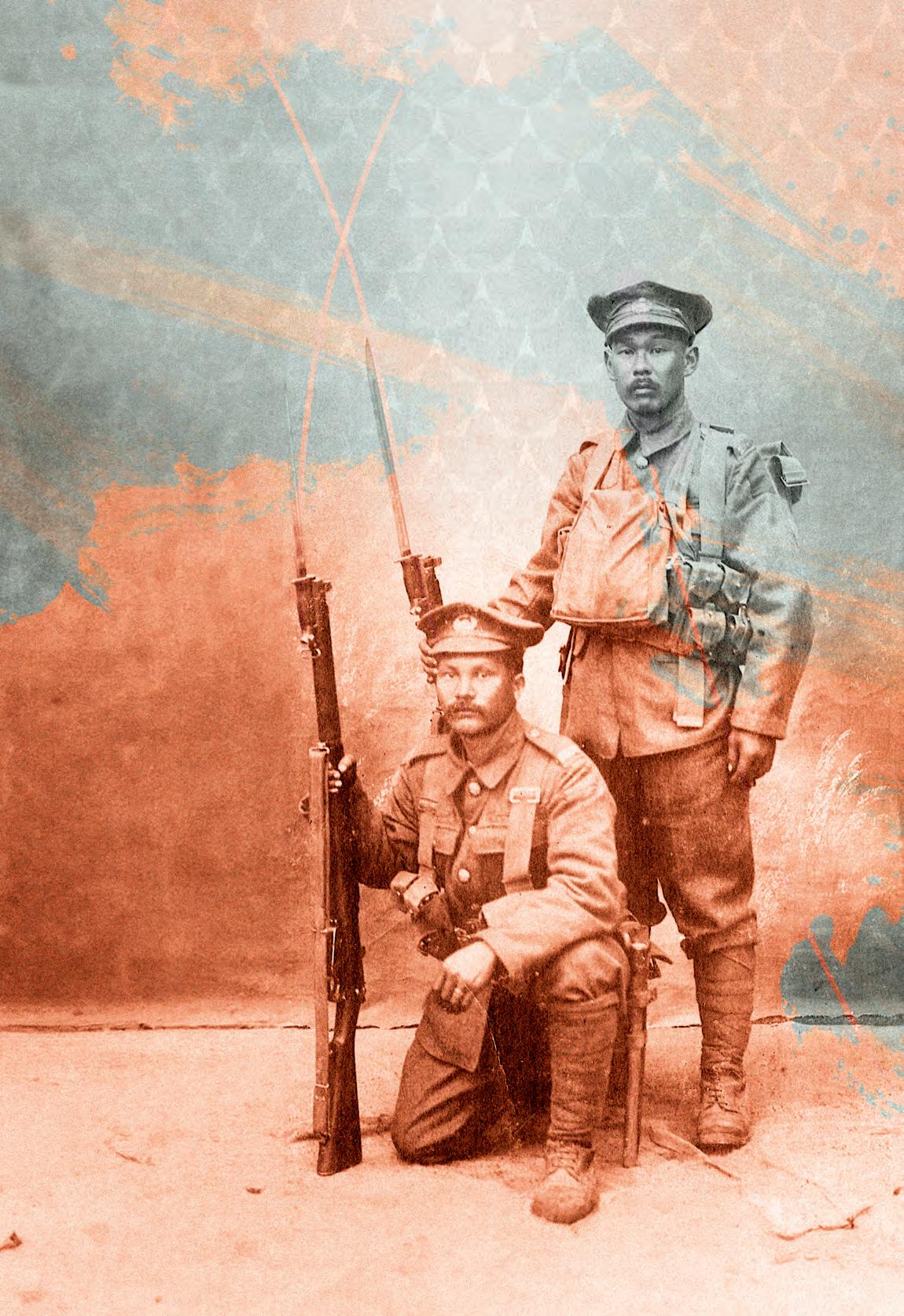

Masumi Mitsui (standing) and comrade Masajiro Shishido pose for a photo in 1916.

By Russ Crawford

Great War Sergeant Masumi Mitsui never stopped fighting for right

The magical and romantic legend of brave samurai warriors and their heroic adventures and unfaltering personal discipline fuelled Masumi Mitsui his entire life. His father was an officer in the Japanese navy and his grandfather was one of the last authentic samurai to serve the emperor of Japan before the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

From early childhood, Mitsui dreamt of being a noble fighter like his ancestors. His aspiration finally came true, not in Japan, and not even in his new home in Canada, but rather on the gritty battlefields of Europe during the First World War.

encountered hostile discrimination and prejudice. Most Asian immigrants had no rights as Canadian citizens and they typically worked for slave wages, often living in substandard accommodations. This wasn’t his dream, however, and like many other newcomers, a return to the homeland simply wasn’t possible. He persevered.

Canadian Japanese Volunteer Corps led by Yasushi Yamazaki, an organizer in Vancouver.

As war continued to rage on into 1916, and with reinforcements desperately needed, Masumi and his fellow Japanese Canadians discovered they could enlist in Alberta, so they travelled to Calgary at their own expense and were welcomed by the 192nd Canadian Infantry Battalion. It wasn’t long before the Japanese volunteers got the call to fight. The group knew they weren’t just fighting for the Allied forces in Europe; they were also fighting for respect and acceptance at home. For most, it was an opportunity to prove their loyalty.