Menorca

Menorca

WALKING means travelling—moving from one place to another. Advancing, exploring, and innovating. The Walking Society is a virtual community open to everyone from all social, cultural, economic, and geographical backgrounds. Individually and collectively, TWS champions imagination and energy, offering valuable ideas and solutions to better the world. Simply and honestly.

CAMPER means “peasant” in Mallorquin. Our brand values and aesthetics are influenced by the simplicity of the rural world combined with the history, culture, and landscape of the Mediterranean. Our respect for the arts, tradition, and craftsmanship anchors our promise to deliver original and functional high-quality products with aesthetic appeal and an innovative spirit. We seek a more human approach to doing business, striving to promote cultural diversity while preserving local heritage.

MENORCA feels adrift in the Mediterranean Sea. There is a stillness to this UNESCO Biosphere Reserve that remains as unspoilt as the proudly enduring Menorcan identity.

THE WALKING SOCIETY The sixteenth issue of The Walking Society Magazine is a journey into a world that has undergone conquests, exchanges and transitions of power yet has emerged culturally enriched in spite of it all. A wild and resilient island that inspires travellers to this day.

OMAR SOSA

The co-founder of the influential interior design magazine Apartamento opens the doors of his Menorcan country house. P. 19

LÍTHICA

An abandoned sandstone quarry transformed into a mystical open-air museum—part installation, part labyrinth. P. 27

ILLA DEL REI

A few minutes by boat from Maó is the Illa del Rei, a tiny island that is now home to Hauser & Wirth Menorca and a perennial garden designed by Piet Oudolf. P. 37

CUINA MENORQUINA

Recipes from land and sea echo the different peoples who have docked at this port: a glimpse into Menorcan cuisine. P. 45

QUARANTINE EVENTS

An artistic residency that operates like a quarantine: isolating creatives since spring 2023 in an old llatzeret on a paradise island. P. 55

S’ÀVIA COREMA

Homage to one of Menorca’s most famous folkloric characters, an old lady with seven legs. P. 62

CAMÍ DE CAVALLS

An illustrated journey along the scenic path that forms the perimeter of the island, featuring Junction.

P. 76

GEGANTS

Menorca is known as the island of giants. We visited a two thousand year old megalithic structure, “Sa Naveta Des Tudons”.

P. 90

BETTINA CALDERAZZO & MATT WESTON

From Australia and England, with a detour via Paris, they finally landed in Menorca—and their innovative art gallery was born.

P. 105

CAVALL MENORQUÍ

The indigenous island breed that steals the show at the Festes every summer.

P. 112

MAIONESA

One of the world’s most famous condiments originated here in the 1700s: a story of conquest, love and, of course, culinary inspiration.

P. 121

SUNNY’S DONKEYS

A shelter for abandoned donkeys in the island’s countryside is an oasis of beauty and tranquillity. And in summer, it’s open to visitors.

P. 128

The sun rises earlier in Menorca than in the rest of Spain. This is because it is the easternmost point in the country, further east than Cap de Creus in Catalonia and further than Capdepera on the neighbouring and larger island of Mallorca. By comparison, the sun rises over an hour later in La Coruña, Galicia. The point where the light arrives first is Maó, the capital of Menorca. Maó is also home to the second-largest natural harbour in the world, more than 6 kilometres deep, resembling a long corridor carved through the island’s rock by the Mediterranean Sea. Much more about this island cannot be so precisely ranked, representing the nuanced and intangible things that make Menorca unique. Most importantly, nature. Menorca, all 700 square kilometres of it, was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1993.

In the roadside groves, as far as the eye can see, is the star of Menorcan flora, the ullastre, also known as the wild olive tree. It covers a third of the island’s territory and can grow up to several metres tall unlike other Mediterranean olive trees. Its gift to the community has always been not so much its fruit (production is scarce, though valuable) but its robust wood. In ancient times, ullastres were used to make agricultural tools and are still used today for traditional gates, known as arcaders, which mark the driveways to houses.

And then there’s the history, so different from its Balearic companions. You feel it in Maó as soon as you disembark. At the port, there is the sensation of having landed in a Caribbean cove, thanks to the trees that remain green and lush from summer to winter, a long fjord that resembles an equatorial river, and architecture that is not typically Mediterranean but more eclectic and cosmopolitan. Entering the city, you cannot fail to notice the bay windows of English origin and the guillotine windows, quite unique at these latitudes and more typical of northern Europe. The island belonged to Great Britain from 1708 to 1802, and that century left its mark on the architecture and much more.

For example, it is traditional on the island to produce and drink the local gin and to eat a reworked English steam pudding called greixera dolça, and grevi, a classic gravy.

Walking through the narrow inner streets of Maó or around its long perimeter, you might be surprised by how vast the sky above Menorca is. The area was preserved from tourism and speculation long before it became a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, thanks to a political issue in the first half of the 20th century. During the Civil War, it was the only island in the archipelago that remained firmly Republican, and the subsequent dictatorship decided to take revenge by allocating all funds to the other islands. A blessing, in retrospect.

Menorca is exposed to eight different winds, the strongest of which is the north Tramuntana. It is said that the other Balearic islanders consider the Menorcans more unpredictable because of this constant wind. Superstitions aside, this element is Menorca’s triumph: a sky that opens and closes like a dance, a horizon free from outsized constructions and left to the olive trees and the sea, which announce the sun to the rest of Spain.

What

OMAR SOSA

The bougainvillaea on Omar’s house is perpetually in bloom, part purple, part orange. We are in the quiet streets towards the end of Sant Lluís, just a few kilometres and minutes from the sea. Here, the low villas hide lush gardens behind their walls, and palm trees and maritime pines perfume the air. Omar Sosa was born in Barcelona but he has a long relationship with Menorca, which is complicated as all deep bonds are. He spent his childhood and adolescence here, only to discover a new chemistry with the island in adulthood. Omar does and has done many things. He is a graphic designer; he co-founded the now cult interior magazine Apartamento; he started The Natural Wine Company wine club; and most recently became the artistic director of BD Barcelona, a Barcelona-based design brand founded in 1972. At the entrance to his house stands a long series of Menorcan chairs, typical of the island. The house is simple and functional, balancing modernity with a highly rural appearance. Omar sits on one of the two sofas, which is covered with a raw cotton throw as white as the walls.

Of all the things you do, Apartamento magazine is probably the best known. And since we’re visiting you at home, let’s start there. How did you find this place?

It was 2006. I was looking for a flat in Barcelona and it was hard work. I couldn’t see myself anywhere. There were several interior magazines around at the time, but they all felt too aspirational, aimed at architects or professionals. They didn’t show the world I wanted to see. It was around then that I met my partner, Nacho Alegre. He shot for magazines and I was doing graphic design. It was an easy match.

Did you share the same vision?

He was also interested in interior design and couldn’t find any magazines he liked, so we talked for a while and decided to start a publication, without a clear idea of what we were going to do. After a while, we made a mock-up with four ideas, in the format that would go on to define Apartamento, with the masthead and everything. Then, one day Nacho went to Milan for work and met Marco Velardi, who became the third musketeer. He was extremely important because we were two guys from Barcelona, but Marco was Italian, and with him on board, Apartamento instantly became an international magazine. We immediately started thinking about how we could create a dialogue with the Salone del Mobile, which is held in Milan. We gave ourselves a deadline and in 2008 we presented Apartamento at Spotti in Milan.

It is a magazine that shows how people live in their homes, rather than focusing on architecture and design.

The person is always at the centre for us. Interiors were an excuse because people are always curious to see how others live, so the stories are about who lives there, not the interiors.

Has seeing so many houses changed the way you look at your own?

Yes, it changes everything. It has made me a bit more aware. I’ve noticed that I did things more casually ten years ago, and I’ve become more organised and precise with time. In the end, I don’t think I know anything about anything, but people often call me thinking I’m some kind of design guru. They ask: I need a sofa, what should I buy? And I say: I have no idea, I can tell you what I like, but I’m not an interior designer.

Apartamento has a strong print identity. What are your thoughts on the future of paper?

This almost feels like a vintage question. When we started out fifteen years ago, we were unsure what should be digital and what should be print, but now I think print has found its place. A natural separation has been created that will remain in place for a long time. And there are a lot of incredible magazines. The book-object is another matter. By buying them and collecting them, you say: I identify with this, I am this. That’s what it’s like for me. My approach to books has always been from the perspective of the object.

Newspapers are a different story, though.

You say that, but my guilty pleasure in Menorca is reading the local paper. It has to be read in print, sitting on the sofa or at the bar. That’s a treat that never gets old.

How have you managed to stay contemporary after all these years?

It amazes me that we are still so relevant and that people still want to find out what we are putting together every six months. But when I think about it, traditional interior design magazines were born to show and explain a certain style, and those styles usually changed after a few years. Without ever having formally decided it, Apartamento has no real editorial voice. Our voice is that of all the people we include in the magazine: they are the ones talking about their world. Our job is more like that of curators: bringing different people together to create a collective voice, not a single one. More than not going out of fashion, Apartamento has never been in fashion. It’s different. In terms of style, it is true that 15-20 years ago, interiors were shot differently, in a more “clean” way, and many interior design magazines have now started shooting more naturally. Apartamento is exactly the same as it’s always been. Everything has grown out of curiosity and fortunately, we are still curious. It is important to mention that we have a very young team who help us see things differently and not grow old. Maybe that’s the magic formula.

When did your relationship with Menorca start?

Very early on. My father came here in the 1960s. He used to sell encyclopaedias and took them all over Spain to places where books didn’t arrive. When he came to Menorca, he fell in love with the island and sold a lot of books here. As a kid, we would come here all the time, then in 2000 he bought a house. I was a teenager and it was very easy to get here from Barcelona, so I came here often until I was in my thirties. Then I started travelling to different cities and something broke: Menorca seemed boring and predictable. I didn’t come back for 10 years; I would go to Greece on holiday instead. I spent five years in New York until 2020, when the lockdown came. That summer I went back to Spain and my partner Nacho said: Come to Menorca, you need some sea. And when I got here, I saw the island with brand new eyes.

You picked up right where you left off.

Two friends suggested we rent a house and I thought it was a great idea because we didn’t know if there would be another lockdown, and I wasn’t going to spend it in the city. We stayed in Maó and I moved my domicile to Menorca. Then I came back for two more summers with my wife Patricia and we had no intention of buying a house. We looked at ads for the fun of it, but we had no money. There were only two that interested us: the first was ugly and the second was this one. We liked the people who lived here, two elderly English people who had filled the house with flowers and suddenly wanted to sell it. We bought it without thinking. It’s crazy, but it happened. And now, living in Barcelona, it’s easy for us to come here.

“I often hear friends say that my house is empty. But to me, it’s not! It just doesn’t need anything more. I kept the previous tenants’ sofas, for example. It was a question of simplicity because I was tired of having precious houses where you are always worried that something is going to get broken. This is a place that can accommodate everyone.”

What convinced you?

We started meeting people straight away. Both people who live here permanently and those who come here from time to time, and they were all kind and interesting. More people have moved here and it has become more international.

How long did you work on this house?

Not long. I didn’t have the time or money. Luckily, we bought it from two people who had been living here, so it wasn’t abandoned or in disrepair, as is often the case. It was simple and functional, and I did the bare minimum. More than anything, our task was to remove things.

Do you prefer an empty house to an overly full one?

I often hear friends say that my house is empty. But to me, it’s not! It just doesn’t need anything more. I kept the previous tenants’ sofas, for example. It was a question of simplicity because I was tired of having precious houses where you are always worried that something is going to get broken. This is a place that can accommodate everyone.

What do you prefer about Menorca, compared to the neighbouring islands?

Each island is different, but Menorca is still very rural, sparsely built and natural. And the architecture is interesting, with a lot of English influences.

Do you think that the desire for quieter, more intimate places is a question of age?

It’s also the call of nature. After five years in New York, I missed nature. I had the immense fortune to spend the first lockdown in Mexico, in one of the most beautiful places in

the world, where I had a beach practically all to myself for three months. After that experience, I couldn’t go back to New York. That’s also why I started seeing Menorca with different eyes. I missed the sea, I missed driving, I missed having space.

Does having a house mean putting down roots?

It’s interesting to think about what it means to have a house in this era. You pay a lot of money for a place that essentially brings you more hassle and headaches. It’s impossible to come here and not work all the time. First I need to install a heating system in the bathroom, then it’s the garden. Something needs doing every week. But that’s the beauty of a house like this.

You also co-founded the natural wine club and shop, The Natural Wine Company, and designed the labels for the natural wine Vivanterre, which has been a big hit, especially in the United States. There is a connection between the pleasure of being at home, a love of nature, and a love of food and wine.

Yes. In the end, it’s a way of meeting people, of ensuring constant dialogue with other people.

What are your favourite objects in the home?

I have a fetish for lamps, but not ceiling ones.

And in this house?

Perhaps the chairs they make here on the island, the Menorcan chairs. They are made entirely by hand from island pine. Having local chairs is lucky because when you have a house, you need a lot of them. And chairs usually cost a lot and are often ugly. These are fantastic.

LÍTHICA

Arriving in Líthica, it is difficult to work out these black lines etched into the pale stone. Horizontal marks of the same size extend tens and tens of metres high and deep along these thick and crumbling walls that resemble monumental structures. This is Líthica. Before becoming what it is today—a natural park, an open-air installation, an architectural and educational complex—it was a sandstone quarry. This marès stone was Menorca’s traditional building material between the 17th century and the 1970s and the lines remain from where the stone was cut. The quarries began to close in the 1980s when the competition from brick became too strong. In those same years, a young French architecture student, Laetitia Sauleau Lara, visited Menorca one weekend. She was taken to see the still-active quarries and it was love at first sight. She contacted the site manager and learned all about the language, techniques and culture of the quarry. In 1994, Laetitia founded an association to save the quarries from being filled in. This marked the birth of the Líthica foundation. Today, the old quarries, cleared of machinery, form an open-air museum that tells the story of the island of Menorca through its geology and living traditions.

The northern part of the island is highly heterogeneous, made up of the oldest materials: sandstone, clay, limestone and dolomite. In the south, the geology is much more uniform, consisting almost entirely of limestone.

Easy to work, sandstone is historically one of the most commonly used stones for construction. The type found in the Balearics, known as “marès”, has always been the main building material and can be spotted in many of the island’s towns.

ILLA DEL REI

THOSE WHO ARRIVE IN MAÓ BY BOAT, AS ARMIES, COMMERCIAL FLEETS AND DIPLOMATIC SHIPS ONCE DID, ENTER THE LONGEST NATURAL HARBOUR IN THE ENTIRE MEDITERRANEAN. A LONG CORRIDOR OF SEA THAT RUNS FOR KILOMETRES FROM THE SOUTHEASTERN FLANK OF THE ISLAND KILOMETRES DEEP UNTIL THE DOCKS OF MAÓ COME INTO SIGHT.

ALONG THIS ROUTE, YOU ENCOUNTER VILLAGES, OTHER PORTS AND ISLANDS. THE LARGEST COMES FIRST, THE ILLA DEL LLATZERET, FOLLOWED BY THE ILLA DE LA QUARANTENA. FURTHER ON, ROUND IN SHAPE AND DROPPED RIGHT IN THE MIDDLE OF THE MARITIME ROAD, IS THE ILLA DEL REI. A MILITARY HOSPITAL WAS BUILT HERE DURING BRITISH RULE IN THE 18TH CENTURY. OCCUPYING A LARGE PART OF THE ISLAND, IT WAS FREQUENTED UNTIL THE 1960S AND THEN ABANDONED. TODAY, THAT STRUCTURE HAS BEEN ENTIRELY RENOVATED AND IS HOME TO SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT: THE HAUSER & WIRTH ART GALLERY, ONE OF SEVERAL AROUND THE WORLD.

HAUSER & WIRTH WAS FOUNDED IN ZURICH IN 1992 BY IWAN WIRTH, MANUELA WIRTH AND URSULA HAUSER, MANUELA’S MOTHER. IT WAS A FAMILY BUSINESS AT FIRST, BUT THIS NEVER LIMITED ITS VISION. PRESIDENT MARC PAYOT JOINED THE TEAM IN 2000 AND CEO EWAN VENTERS IN 2021. TODAY, 39

HAUSER & WIRTH REPRESENTS MORE THAN NINETY ARTISTS AND ORGANISES EXHIBITIONS, GRANTS, RESIDENCIES AND RESEARCH PROJECTS. FROM THE VERY BEGINNING, THE STARS OF THE ART WORLD— CONTEMPORARY AND OTHERWISE—HAVE ALWAYS GRAVITATED TOWARDS HAUSER & WIRTH. THE FIRST EXHIBITION, HELD IN ZURICH BACK IN 1992, COMBINED SCULPTURES (CALLED “MOBILES” BY MARCEL DUCHAMP) AND GOUACHES BY ALEXANDER CALDER WITH OTHER SCULPTURES AND PAINTINGS BY JOAN MIRÓ. TODAY, THE GALLERY HAS BRANCHES ALL OVER THE WORLD: FROM NEW YORK AND LOS ANGELES TO HONG KONG, VIA ENGLAND, FRANCE, SWITZERLAND AND SPAIN.

THE ART SPACESHIP LANDED ON ILLA DEL REI IN JULY 2021 AND MADE NO SECRET OF ITS AMBITION TO TRANSFORM MENORCA INTO A CENTRE OF GRAVITY FOR CONTEMPORARY ART. WHILE THE PROJECT WAS AWAITING THE GREEN LIGHT FROM THE SPANISH AUTHORITIES, THE GALLERY INVITED A DELEGATION FROM MENORCA TO VISIT ITS HEADQUARTERS IN SOMERSET, ENGLAND. THE VILLAGE OF BRUTON, HOME TO THE HAUSER & WIRTH DIVISION IN QUESTION, HAS BECOME AN IMPORTANT DESTINATION FOR ART ENTHUSIASTS: OPENED IN 2014, IT ATTRACTS OVER ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND VISITORS EVERY YEAR. BACK ON MENORCA, HAUSER 40

Piet Oudolf’s garden at Hauser & Wirth Menorca

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Daniel Schäfer

‘Untitled’ (1981) by Hans Josephsohn

amid Piet Oudolf’s garden

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

© Josephsohn Estate. Courtesy the estate of the artist and Kesselhaus Josephsohn

Photo: Daniel Schäfer

‘Le Père Ubu’ (1973) by Joan Miró

amid Piet Oudolf’s garden

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

© Successió Miró, 2024

Photo: Daniel Schäfer

Piet Oudolf’s garden at Hauser & Wirth Menorca

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Carlos Torrico

& WIRTH CHOSE TO RENOVATE A PRE-EXISTING BUILDING AND THE ART COMPLEX COVERS A TOTAL OF 1,500 SQUARE METRES. THIS IS SURROUNDED BY A GARDEN DESIGNED BY THE DUTCH LANDSCAPE GARDENER PIET OUDOLF, WITH SCULPTURES BY LOUISE BOURGEOIS, JOAN MIRÓ AND EDUARDO CHILLIDA.

A WORK OF PLANT ART SET AMONG THE OTHER EXHIBITS, PIET OUDOLF’S GARDEN IS ONE OF THE MANY REASONS TO VISIT HAUSER & WIRTH’S MENORCAN HEADQUARTERS. THE PRINCIPLE BEHIND THE GARDEN HAS CHARACTERISED OUDOLF’S CAREER AS A GARDEN DESIGNER FOR DECADES: THE USE OF PERENNIALS, THIS TIME OF MEDITERRANEAN ORIGIN. “WHEN I FIRST VISITED MENORCA, I WAS INSPIRED BY HOW PERIODS OF FLOWERING SPREAD THROUGHOUT THE YEAR, WHICH MAKES THE GARDEN INTERESTING IN ALL SEASONS,” EXPLAINS PIET OUDOLF. “I AM MOST INTERESTED IN THE STRUCTURE OF PLANTS, AND I USED PERENNIALS ADAPTED TO THE CLIMATE TO CREATE A GARDEN RICH IN SHAPE AND TEXTURES,” HE EXPLAINS ABOUT THE GARDEN ITSELF.

OUDOLF TELLS US HE COMES TO MENORCA ONCE A YEAR TO MEET WITH LOCAL GARDENERS AND DISCUSS CHANGES AND IMPROVEMENTS. 43

OUDOLF IS THE MOST FAMOUS MEMBER OF THE MOVEMENT KNOWN AS THE “NEW PERENNIAL”. BORN IN 1944 IN HAARLEM, IN THE NETHERLANDS, HE THEORISED THE CREATION OF GARDENS THAT ARE ALIVE ALL YEAR ROUND, TRANSFORMING MONTH BY MONTH INSTEAD OF DEPENDING ON A SINGLE FLOWERING SEASON. THIS PUTS LIFE BEFORE MERE ORNAMENTATION. HIS DESIGNS, ALL HAND-DRAWN IN DIFFERENT COLOURS, HAVE BEEN LIKENED TO ARCHITECTURE. BEFORE THE GARDEN FOR HAUSER & WIRTH IN MENORCA, HE MADE HEADLINES FOR A GARDEN IN THE LARGER CONTEXT OF BATTERY PARK, NEW YORK CITY, AND ABOVE ALL FOR HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE HIGH LINE: AN ABANDONED, ELEVATED RAILWAY ON MANHATTAN’S WEST SIDE TRANSFORMED INTO A ONE-OF-A-KIND NATURE WALK BETWEEN SKYSCRAPERS AND THE HUDSON RIVER.

AMONG THE GROVES OF WILD OLIVE TREES, OUDOLF’S GARDEN ON THE ILLA DEL REI IS HOME TO SUCCULENTS, LONG STEMS OF AGAPANTHUS, FRAGRANT LAVENDER AND THYME, PRICKLY THISTLES AND SOFT GRASSES SUCH AS STIPA TENUIFOLIA .

Menorca can be a cold and windy island, so warmer, wintery dishes are an important part of its culinary tradition. Broth, for example, made with vegetables or meat, is typically eaten on Wednesdays. Since 2014, the “Els dimecres és dia de Brou” initiative has standardised the price of broth across many of the island’s restaurants. But only during the coldest months of December and January and, as tradition dictates, only on Wednesdays.

Just a few simple ingredients, those strictly necessary for a soup: onions, garlic, tomatoes, peppers, oil and parsley. And lobster, of course. Of those found in Menorca, rock lobsters are preferable: bright red ones, that are smaller and tastier than those living on the seabed.

Caldereta de llagosta (lobster soup)Another popular seafood dish in Menorca is octopus. Here in an extremely simple version: seasoned with onion. The prep time is long because the octopus has to be frozen the day before, a step needed to soften the fibres, but the actual cooking takes no more than an hour and a half. Serve with a little jus.

Pop amb ceba (octopus with onion)

A recipe for strong palates that is simple but lengthy. The snails are prepared the day before and left to cool. Then the crab claws and legs are cooked in a blend of garlic, onion, pepper and tomato, before the cooked snails are added at the end, with plenty of broth.

Caragols amb cranca (snails with crab)

An island rich in nature and shrubs is, traditionally, an island rich in rabbits. That is why this rabbit in sauce, a legacy of British rule, is typical in Menorca. It is cooked with garlic, onion and bay leaf, enhanced with bacon fat, and finally reduced in a little sherry.

Conill amb salsa (rabbit in sauce)

Conill amb salsa (rabbit in sauce)

A traditional Mediterranean seafood dish that has toured all the major European ports, from Genoa to Naples to Menorca. A cuttlefish stew flavoured with garlic, onion, parsley and tomato. The peas are added at the end to keep them crisp and fresh.

Sípia amb pèsols (cuttlefish with peas)

Despite its name, this dish is not made with rice but with wheat, very similar to bulgur, which is pounded in a mortar. After soaking the wheat, the recipe calls for the addition of sweet potatoes, tomatoes and pieces of pork, two typical Menorcan sausages in particular: botifarró and sobrassada

A typical dessert throughout the Balearic Islands that is not that sweet, or rather: not always. Shaped like a spiral or a snail, ensaïmada is made with water, lard, sugar, flour and yeast. The classic version comes without a filling, but it can be filled too. Perhaps with sobrassada , a Balearic sausage, cheese or cream. The most famous of all is cabell d’àngel , a special pumpkin jam.

For centuries, Menorca’s ports have been some of the most important in the Mediterranean, which has inevitably influenced its language, architecture and cuisine. Arab, English and French influences are recognisable in the most typical dishes, hybridised with peasant, Spanish and European traditions. Today, for example, a pounded wheat similar to bulgur, evidently from North Africa, is eaten with typically country-style pork sausages. The Menorquin menu also leaves plenty of room for the bounty of both sea—think lobsters, cuttlefish and crabs—and land, such as squash, tomatoes and… snails. Tying it all together is that golden thread that has woven its way through the centuries: olive oil.

The dishes shown on these pages are displayed in ceramics by Blanca Madruga, a ceramist based in Menorca. Blanca was born in Madrid and grew up in Barcelona. She worked as a lawyer before leaving it all behind and travelling the world, working on social projects in Ethiopia and Madagascar before landing here. She finally stopped thanks to the island’s slow and compassionate lifestyle and the Menorcan winter, which she considers far superior to the chaos of summer.

Dana, Pelotas Ariel S/S 2024

Dana, Pelotas Ariel S/S 2024

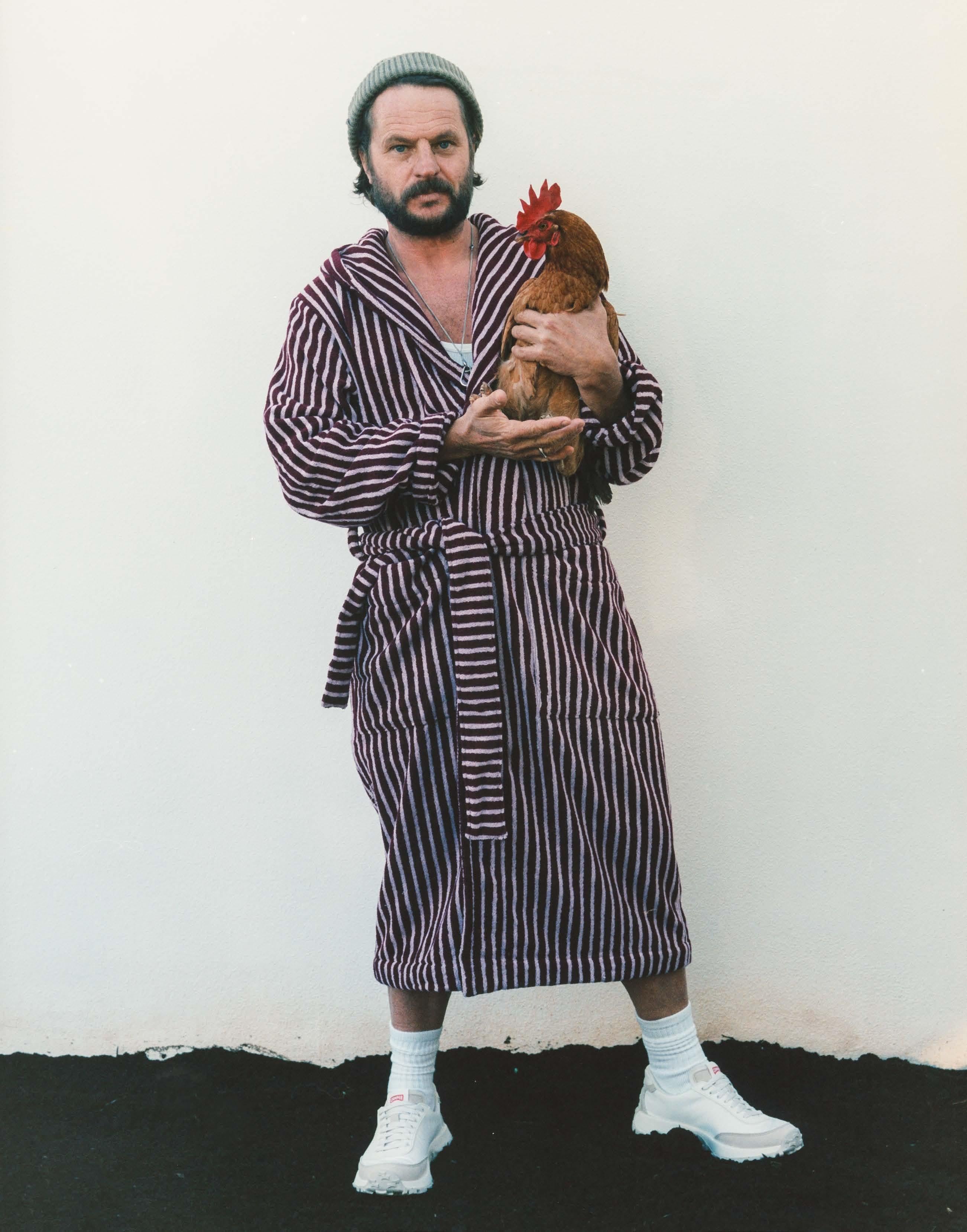

QUARANTINE EVENTS

The island where the Llatzeret of Maó is located was once a peninsula called Sant Felip, connected to the mainland by a narrow strip just over 100 metres long. Upon the completion of the Llatzeret in 1700, this was destroyed to ensure total isolation, with no chance of escape or contact. Today, it takes just a few minutes to get there from the port of Es Castell on one of the two boats that service the route daily. The historical building has been magnificently preserved, looking more like an architectural masterpiece than an isolation hospital. Surrounded by palms and maritime pines, visitors can explore the 140 cells as well as warehouses, purification rooms, the chapel, cemetery and observation towers. Since spring 2023, the Llatzeret has also been home to an unusual artist residency, appropriately named Quarantine, the independent organisation founded by Carles Gomila, Joan Taltavull, Itziar Lecea and Darren Green. Quarantine aims to offer an art experience unlike any other existing workshop or residency: using isolation as a driving force for inspiration and practice through a truly unconventional approach.

How would you describe the project in a few words?

CG A purgatory for artists.

And how does this purgatory work?

CG We place artists under quarantine. Real quarantine. We are trying to question the concept of art education, which requires a change of consciousness. It takes a lot of work, the help of great artists and a secret programme that is not revealed to participants in advance. This ensures that they arrive unprepared. Smartphones are banned as well, which creates a useful withdrawal syndrome.

How is the team organised?

JT Carles is the creator and director. He is behind the original idea.

CG Joan is a dancer who takes care of the artistic direction and some of the workshops and courses; Darren handles management and is also a translator; and Itziar is in charge of communication.

CG Before Quarantine, I ran an art retreat called Menorca Pulsar, named after the star. It consisted of international painting workshops with excellent professors from all over the world teaching painting techniques, and it ran from 2016 to 2021. It worked very well and attracted international interest but I realised that the artists who enrolled were just imitating the techniques of their role models, their idols. That’s an issue for creatives. I was faced with an ethical dilemma and started planning more radical workshops. I wanted to break away from the kind of audience whose only goal is pure achievement. All this transformed Menorca Pulsar into more of a bootcamp than an art retreat. Then came an opportunity to take the leap, change the format and radicalise it even further. That’s when Quarantine came about.

When did this all happen?

IL The first edition was in April 2023, the second in October.

Has Menorca welcomed the initiative?

CG Very much so. We had 180 applicants for this last edition and we had to narrow it down to 70. We chose the people who we thought would be the most committed to the programme. This initial selection process is necessary because people might take Quarantine too lightly, when in reality it’s very tough.

IL These numbers only take the students into account; you’ve got the staff and mentors on top of that.

What kind of artists are accepted to Quarantine?

CG Mostly painters, but there is a broad spectrum. They aren’t necessarily all figurative painters. There might be people who work in illustration, tattoo art or the film industry, but they all have a connection to plastic art.

How did you meet?

IL Carles and I met at an opening in 2009. I am a journalist and I was interviewing him. We’ve been together ever since and we’re married now. We’ve known Joan for years.

CG And Darren, the fourth member of Quarantine, had a bar in Ciutadella and I was a client. I was looking for somebody very practical who could oversee all the concrete aspects of the undertaking and I thought he was the perfect person for the job.

How did the public react when you first announced Quarantine?

IL The Menorca Pulsar brand was well-known internationally and we used that platform. We worked mostly through Instagram and a newsletter that already had a good database. It is fundamental to clearly communicate what Quarantine is and what we do because that’s the first filter to ensure that people who aren’t suited to the project don’t apply. We don’t want Quarantine to come across as a holiday or a week of relaxation in Menorca. It’s an intense and, in some ways, difficult experience.

How did you end up on this island?

CG In 2016, I had the chance to visit. Since then, I’ve always known that I wanted to do something here because it made such a strong impression on me. I started to have recurring dreams about the island. I’d already imagined everything that we have implemented, including the logo. I designed it in 2016 and then found the same symbol engraved in the stone in one of the cells. Let’s put it this way—a series of coincidences convinced me that it was a good idea to come here.

You must have asked permission from the municipality.

IL Yes, we collaborate with the municipality of Es Castell, the town opposite, which sends boats every day. It’s not easy because it’s a large space that’s hardly ever used. Plus, the logistics are complicated—if you forget something for lunch, you have to get a boat back to town!

Did the format and the place come together at the same time?

CG This was a sanitary prison specifically built to isolate people. What we do here is isolate artists from the external world so they can be quarantined with their ideas. The setting influences the format that can only exist here. It is born of the sensation of being surrounded by walls and crossing the sea by boat every day, like a rite of passage.

Will the format remain the same in the future? Do you have any plans to expand it further?

CG We will hold one annual edition in 2024, before probably returning to two editions in 2025. We are not thinking of expanding because Quarantine works well with smaller groups of people. It would be exciting to use this format for other specialisations, especially writers.

“This was a sanitary prison specifically built to isolate people. What we do here is isolate artists from the external world so they can be quarantined with their ideas. The setting influences the format that can only exist here because it is born of the sensation of being surrounded by walls.”

The idea of disconnecting and isolating from social media and smartphones is interesting. After ten years of unchecked use, there is now discussion about their negative impact.

CG We have observed that abstinence from smartphones starts to take effect around the second day. We have all introjected an instinctive impulse to record things, to photograph them. On the second day, this disappears and is replaced by a kind of reluctance to return to it, as if people feel liberated. The level of attention is very different. Artists use their memory differently. They focus differently. The head functions differently; you enter a different state of mind. All this is on top of the fact that the programme is secret—nobody knows what to expect and the challenges we present have more than one solution, so people have to engage creatively.

IL One of the participants in the latest edition, Lyda, told me that it was also significant that people were really talking to each other. And talking demands listening.

It might be intimidating, in a way.

CG The programme is built on two pillars. The first is that fear is a compass. We should not avoid fear but understand why

it exists and where it is pointing. The other is that vulnerability in art is power. On these grounds, there is no one way to place value on what an artist is doing. There is no need to receive applause or any other way to qualify a piece of work. This lack of pressure allows errors to become constructive.

What is a typical day at Quarantine?

CG Masterclasses in the conference room in the morning. Here, the invited artists reveal their own vulnerabilities and this shows the other participants that they are just like them. Then art workshops where we question some of the rules imposed by traditional art education systems. This is followed by lunch together so that the group can bond. Then we have different activities to decompress, including concerts and body expression sessions. There is also a mental health segment designed in collaboration with psychologists. Finally, mentorship with the invited artists. Those one-to-ones are especially important.

And when you finish, there are no marks, no report cards?

CG The complete opposite: we burn everything at the end.

S’Àvia Corema, or “Grandmother Lent”, is one of the most famous characters in Menorcan folklore, and she comes alive every year during the seven weeks of Lent. Unlike the average grandmother or even the average person, S’Àvia is enormous: her cardboard statue, which parades through the streets of Maó every Saturday until Easter, is three and a half metres tall and weighs about 65 kilos. What makes Grandmother Lent even more special is that she boasts seven legs. One for each week of Lent. During the parade, the island folk sing and dance to traditional local music. At the end, the procession arrives at a plaça where a child is chosen to remove one of S’Avia’s feet. Every Saturday, one foot is removed until none are left and Grandmother Lent, like winter, can make way for Easter and spring.

S’ÀVIA COREMA

CAMÍ DE CAVALLS

A PATH DATING THE 14TH CENTURY TRACES THE

OF THE ENTIRE IT TRAVERSES BEACHES, CLEARINGS HILLS, NEVER SIGHT OF

DATING BACK TO CENTURY THAT PERIMETER

ENTIRE ISLAND.

TRAVERSES MEADOWS, CLEARINGS AND NEVER LOSING THE SEA.

AMONG MENORCA’S MANY NATURAL WONDERS IS ONE THAT IS MAN-MADE AND ESTIMATED TO BE AT LEAST FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OLD. IT DOES NOT STAND OUT ON THE HORIZON, NOR IS IT AN ARCHITECTURAL WONDER OR AN ANCIENT CASTLE, BUT A ROAD, OR RATHER A PATH. THE CAMÍ DE CAVALLS IS AN UNPAVED ROUTE THAT TRACES THE PERIMETER OF THE ISLAND, BUILT IN THE 14TH CENTURY TO CONNECT ALL OF MENORCA’S LIGHTHOUSES, CANNONS AND DEFENSIVE FORTRESSES. IT CAN BE TRAVELLED ON FOOT, BY BICYCLE OR, OF COURSE, ON HORSEBACK. IT TRAVERSES BEACHES, MEADOWS AND FOOTBRIDGES, NEVER LOSING SIGHT OF THE SEA. OVER THE CENTURIES, LARGE PARTS OF THE PATH ENDED UP IN PRIVATE HANDS AND WERE MOSTLY ABANDONED, BUT IN THE 1990S, THE PEOPLE OF MENORCA BEGAN LOBBYING THE AUTHORITIES TO MAKE IT PUBLIC AGAIN. THEY SUCCEEDED IN 2000 WITH THE LLEI DEL CAMÍ DE CAVALLS (CAMÍ DE CAVALLS LAW). THE RENOVATION PROCESS LASTED UNTIL 2011 AND SINCE THEN THE PATH HAS ONCE AGAIN BEEN A PUBLIC ASSET.

Some people know Menorca as the island of giants. And giants are indeed a part of the island’s folklore traditions and celebrations, especially in Maó, where they are also known as capgrossos, after the enormous papier-mâché heads that walk the streets on stilts up to a metre high. But the giants also belong to more ancient legends, which is the real reason for the island’s nickname. The legend refers to an ancient megalithic construction by the name of “Sa Naveta des Tudons”, which dates back to a millennium before the year zero. Popular tradition has it that two giants who lived where Ciutadella is today were in love with the same woman. She was undecided, however, and the two young men resorted to a contest of

strength and skill to resolve the matter. One of the giants set about building a “naveta” while the other dug a well to find fresh water. The first to finish his work would marry his beloved. When the naveta was just one stone away from completion, the other giant struck water. Enraged by the futility of it all, the first giant hurled that final stone into the well, killing his friend. Wracked with guilt, he killed himself shortly afterwards. The naveta was discovered in the 1950s, thought to be a form of megalithic chamber tomb, and is estimated to be between 2200 and 1750 years old. It is one of the oldest and best-preserved megalithic monuments in all of Europe.

The importance of changing course for

BETTINA CALDERAZZO & MATT WESTON

In Greek, they are known as the “Etesians”, but other languages prefer “Meltemi”. The words refer to a group of dry winds that blow in from the Aegean Sea in summer. Winds that can be strong and dangerous. A historical Mediterranean force that inspired the name of Bettina Calderazzo and Matt Weston’s contemporary art gallery in Ciutadella, which is an exhibition space and much more.

Before founding Etesian, Matt and Bettina travelled the length and breadth of the Mediterranean coast before finally finding a home in Menorca. Etesian is the organic evolution of these experiences, thoughts, and attempts. Today, it is a gallery that has exhibited international artists such as Alexandria Coe, Lemos-Lehmann, Lauren Doughty and Toni Salom, but it is also an atelier for artists and a residency project. Ever-evolving and as open to change as Bettina and Matt were on their travels.

After hopping from port to port, you ended up in Menorca.

MW Yes. In the end, we settled in Menorca. It was here that our idea first took shape and we found the perfect place in Ciutadella. It was really run down so we renovated it: a lot of cleaning, painting and mending. We didn’t know exactly what it would become and over time it transformed into a gallery— mostly—with a store attached.

What did you both do before embarking on this adventure?

BC I worked in London as an art director in advertising. It was a pretty crazy working environment, very intense and fastpaced with constant 3-day deadlines.

MW I was a jewellery designer, something I started doing in Mexico as a travelling artisan, which evolved into a proper shop on Sydney’s Bondi Beach in Australia. I later moved to London to design for a brand and then set up on my own, with my own brand.

How did you meet?

BC I am half Australian and half Italian. I lived in Australia, then moved to Paris for five years and that’s where I started working as an art director. Then I met Matt and went to live with him in London and we eventually moved to Menorca. Matt lived in Australia for ten years. When we were in London, we were planning quite a radical change. That’s when I started thinking about the environment I had grown up in and what my childhood had been like. I wanted to go back to something like that, but without going so far away.

What was your childhood like?

BC Very typically Australian: beach before school, beach after school. But because my father is Italian—from Naples originally, but he moved to Australia in his thirties—my parents had a wonderful group of European friends. So I had this Australian background on my mother’s side and this huge European influence and lifestyle on the other. We would go to someone’s house for lunch and dinner every week. Art, culture and philosophical conversations were very important in my house. I grew up surrounded by all that and it inevitably influenced me. We went to Italy every summer for two months and that helped create a strong connection with Europe.

Why did you decide to make such a radical life change?

BC It was a somewhat obvious choice for me. I was doing something that I was not completely satisfied with; it was a job that I found myself in, without really choosing it. I was good at it and I liked many of my colleagues, but in the end the work wasn’t something that gave me deep satisfaction. Your creativity, in these jobs, is often exploited and put at the service of an idea that isn’t yours, to sell a product that you wouldn’t even buy. So we decided to travel. It worked at first: we were both working freelance. It was pre-Covid and every-

thing was fine. But as soon as I arrived in Menorca, it was clear that our lives didn’t fit in with where we were. I was spending 12 hours a day in front of the computer and at a certain point, I said to myself: this is not the life I want to live. Then Coco, our daughter, came along. She was the main reason for the change.

How did you find the place that is now Etesian?

BC We spent six months travelling around the island, slipping postcards under the doors of all the places we liked. One day, I met an old man who owned this space. He was a very peculiar character: he had lived in Japan for eight years because the boat he was sailing on had had an accident while he was there. We sort of courted him for six months because as soon as we saw this space and the whole building, we fell head over heels.

How did you connect with the art scene in Menorca?

BC In the beginning, we had help from Mallorca, too. We had some friends there so thanks to them, we started bringing over artists from Mallorca and then an artist from London. We wanted to introduce our own perspective, so initially we were interested in bringing artists from outside Menorca. I felt that what I personally had to offer was this different perspective, rather than trying to do something I wasn’t quite prepared for. But several years have passed and now we invite more and more Menorcan artists.

What are the differences between a gallery like Etesian and a more traditional gallery?

BC I think Etesian is quite unique for several reasons. One is my Australian perspective, which allows me to mix a focus on the new with graphic and indigenous art, hybridising everything with the more poetic and romantic aspects of European culture. Once, while planning an exhibition that brought all these threads together, I talked with somebody who said it would never work. But, in the end, the two paths came together. The other thing is that, in terms of physical space, this gallery consists of three different spaces. That means we can create unique experiences: one of the most recent artists, for example, used the cave in the basement to create a sound experience in a completely dark space. You don’t get the feeling of entering the classic empty white box, which many other galleries evoke, when you come to Etesian.

MW The walls are a metre thick and there are tunnels on the lower floor. Plus, a turret on the side, which was a watchtower used to detect the arrival of potential invaders in the harbour. It has a lot of history and this space has been a journey for us. It would have made no sense to approach it with a closed mind and elitism. Instead, we are constantly learning new things, growing and having fun.

BC When we organise an exhibition, we also try to make it an immersive experience: we organise dinners where you can meet the artists or participate in their work. For one exhibition, we turned Etesian into the exhibiting artist’s atelier, so you could watch them working. That kind of storytelling and immersive experience is something I don’t see in many

galleries. Of course, I’m not saying we are the only ones in the world doing these things, but we get a lot of positive feedback about this open and inclusive attitude towards art.

What made you fall in love with Menorca?

MW It’s hard to name one single thing. It seems naive to say, but it just felt like the right thing to do. As soon as we left the airport, the first time we set foot on Menorca, we immediately felt more relaxed, as if we had arrived. From that moment on, we immediately started looking for a place to live. It was the first time we had felt so at home in all the places we visited. That feeling has never changed. I can make a list of all the extraordinary things about Menorca, from the beaches to the food to the inhabitants, but what made the difference was a feeling.

BC There were, of course, several things on our checklist. The sea. Not having to drive two hours to get from one place to another. A place with culture but also things to do. A town that wasn’t too small, with more than just a post office and a café, but equally the presence of nature and open skies.

MW One thing we realised after a short time was that Menorca has a life independent of tourism. If the tourists disappeared from one day to the next, life would continue in the same way. There is a very strong cultural identity here, unlike other places we have visited around the Mediterranean. The concept of community is extremely important to us. The small town where we live is big enough not to know everyone, so there are always new people to meet, but at the same time, it is small enough that you know a lot of people.

Where did this original love for the Mediterranean come from?

MW I left England in 1990 to live in Eivissa. That was my first experience of the Mediterranean and I have carried it with me ever since.

BC For me, it’s almost a duty to love the Mediterranean. I feel my Italian roots very, very deeply. I spent every summer of my youth on the Amalfi Coast. The Balearic Islands have the Mediterranean and something more: something to do with the light and the energy you feel. It is also a very young island, full of people who want to experiment with interesting things. There is an international mentality and its proximity to Barcelona helps. Ideas flow easily here, which is important.

Menorca is attracting a lot of attention from around the world. Are you afraid that it might be too much?

MW There is indeed a spotlight on the island right now and you do notice it when you’re out and about, but it doesn’t scare me, honestly. The world’s attention tends to focus on something for a minute and then quickly move on to something else.

BC I think the Menorcans are very resilient and there is a strong resistance to external pressure here.

“One thing we realised after a short time was that Menorca has a life independent of tourism. If the tourists disappeared from one day to the next, life would continue in the same way. There is a very strong cultural identity here, unlike other places we have visited around the Mediterranean.”

The horses’ black coats gleam in the summer sun. Their bridles are decorated at the jaw, muzzle and tail, but what shines the brightest are the little silver hearts in the centre of their chests. They parade through the town, as if in a procession. The riders, or caixers, wear black and white. Celebrations begin when they reach the main plaça. These are the Festes de Menorca, held throughout the summer, 13 in all, as each village celebrates its patron saint over two days. On the first day, the festivities are held in the evening and continue until midnight. On the second, they take place in the morning and this is the most eagerly awaited moment. The horses (cavalls menorquins, a breed indigenous to the island) and their caixers make their way through the streets and emerge in the main plaça, which is covered in sand for the occasion, only to discover hundreds —if not thousands—of people waiting to welcome them. A band fills the air with music. The first to enter the plaça is the fabioler on a donkey, playing a flute and beating a small drum. Then come the riders, bearing the flag of the town or village, followed by everyone else. It is time for the jaleo: the horse rears on its hind legs, as if leaping in exultation. This is the culmination of the Festes. At the end of the parade, the knights receive the canya verda, a young bamboo stalk, a symbol of longevity and good fortune, tied to a small silver spoon, the cullera.

Cavalls menorquins are an indigenous breed related to the cavall mallorquí and the cavall català

Highly valued for their work in the fields and for riding, the breed was officially recognised in 1988.

Thanks to their leading role in the island’s festivals, the number of cavalls menorquins is constantly growing. The current number is around 3,000, with an average of 250 born each year.

ONE OF THE MORE ‘FRANCOPHILE’ THEORIES SPEAKS OF MAYENNE, FORMERLY MAÏENNE, A DEPARTMENT IN THE NORTHWEST OF THE COUNTRY, A FEW KILOMETRES FROM THE ENGLISH CHANNEL.

THE PROBLEM WITH THIS THEORY IS THAT THERE HAVE NEVER BEEN ANY OLIVE TREES IN THAT AREA.

The freshest egg yolks, lemon juice and oil, followed by salt, vinegar and a pinch of pepper in small but essential quantities. Oh, and some people add mustard. The ingredients of mayonnaise are few and easy to remember. Does this mean the sauce has a simple origin story? Quite the contrary. Embedded in this seemingly simple recipe are wars of conquest, clandestine loves and culinary intrigue. It is a story that begins in Maó, the capital of Menorca. Did you hear that sound? Say it again. Maó. Maionesa. That’s right.

It was in 1756 when Louis François Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu and commander of the French troops in the Battle of Menorca, docked in Ciutadella, along with over ten thousand men on 200 ships. The British were defeated for now, although it was not a definitive French victory: the troops retreated to Gibraltar, but this was one of the first acts of the Seven Years’ War, which would end with a British triumph in 1763. Stone cold facts, so far, but now various forks in the road tell us different tales. It has long been a challenge to distinguish between legend and truth, as the two are often mixed and blended, much like the oil, lemon and yolk.

One of the stories passed down about Richelieu’s stay in Menorca would have it that one night the worried duke was wandering around Maó, so absorbed in thought that he forgot to have dinner. It was very late when he noticed the rumbling in his stomach and decided to pop into a small

tavern. Having run out of food but fearful of appearing inhospitable, the innkeeper presented him with some sorrylooking leftover meat. “Sir, this is all there is, but it is not suitable for your excellency,” he told him. Richelieu replied: “Season it as best you can, for in times of hunger there is no bread too hard.” The innkeeper then served the meat covered in a sauce that the duke liked so much he asked for the recipe. “But sir, it is only an egg sauce,” came the reply. The duke insisted and jotted down every step. Upon his return to France, he took that sauce with him, introducing it as maionesa.

This is not, however, the most authoritative version of the origin of mayonnaise. Another story, told by Pep Pelfort, a scholar of gastronomic history and director of the Centre d’Estudis Gastronòmics Menorca, seems more likely. This one goes that Richelieu encountered the sauce on 21 April 1756, a few days after landing on the island, at a banquet held in honour of the French troops at a large estate. Pelfort’s research shows that there were not many large families who collaborated with the French or were openly Francophile. Of these, it would appear that only two produced olive oil, a key ingredient in mayonnaise: one in Sant Lluís and the other in Alaior. This well-conducted investigation reveals that the lady who served the famous sauce must have been either a Mrs Joana or a Mrs Rita.

Naturally, the French dispute these versions of events. According to the more ‘Francophile’ theories, the sauce may have originated in Richelieu’s homeland, where clues are also sought in the name. One claimant speaks of Mayenne, formerly Maïenne, a department in the northwest of the country, a few kilometres from the English Channel. The problem with this theory is that there have never been any olive trees in that area, which is far too northerly for the production of this fundamental ingredient. Another geographical theory takes us to Bayonne, where a slight spelling change over the centuries turned the “b” into an “m”. Another hypothesis comes from Marie-Antoine Carême, chef, writer and “inventor” of the haute cuisine style. He writes that the sauce’s original name was “magnonnaise”, a derivation of the French verb manier, “to mix”, a clear nod to the constant stirring required in its preparation.

The dispute may have been settled once and for all in 2022, when the family recipe book of the Caules, from Maó, was found in Menorca. The discovery was made by Pep Pelfort, who followed the breadcrumbs left by one of Richelieu’s Menorcan mistresses. The duke was famously said to have appreciated the island’s women as much—if not more—than its cuisine. She owned the house that hosted the famous April 1756 banquet for the French. Following a trail of letters and after months of research in the family archives, historian Pelfort finally came across the recipe

book. From there, it was analysed by calligraphy specialists, bibliophiles and historians until the definitive proof was found: the menu for Richelieu’s banquet on a page at the end of the manuscript. The mayonnaise recorded there, however, was not at all like the one we know today: it was called “salsa per a peixos crus” and was served with bits of onion, herbs and parsley. There is a passage in one of Duke Richelieu’s letters that reads: “And should I forget you, Madame, this amorous sauce, with which you have delighted my palate on so many occasions, will recall you to my memory and given the impossibility of calling it by your name, I will christen it Maionesa.”

“AND SHOULD I FORGET YOU, MADAME, THIS AMOROUS SAUCE, WITH WHICH YOU HAVE DELIGHTED MY PALATE ON SO MANY OCCASIONS, WILL RECALL YOU TO MY MEMORY AND GIVEN THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF CALLING IT BY YOUR NAME, I WILL CHRISTEN IT MAIONESA .”

SUNNY’S DONKEYS

Sheltered by olive trees and drystone walls, they graze, seemingly waiting for time to pass, surrounded by the chirping of cicadas, the soundtrack of a Menorcan summer. They are curious: if you approach them, they too draw closer in search of something to eat or a hand to stroke them and scratch behind their ears. The donkeys at Menorca Donkey Rescue are looked after by Gundi, who was born in Germany but has lived in Menorca for almost thirty years. She dedicates every weekend and much of her free time to this sanctuary, which has saved 20 donkeys from abandonment. She is not alone: Sunny, an Englishwoman, opened the colony eight years ago with just four donkeys on this piece of land owned by a friend. At first, Gundi popped in every so often, but found she liked it more and more. “I like the idea of being able to offer handson help, not just a long-distance donation,” she tells us. During the summer, the donkey sanctuary opens its doors to visitors, mainly families. This is an excellent way to finance the project so it can continue to house more donkeys here in the shade of the olive trees.

His name is Sam in everyday life, but for just one day a year he is also known as s’homo des bé. In Menorcan, this means “the sheep man”, an important folkloric and religious figure, especially in Ciutadella. The week before the feast of Sant Joan, s’homo des bé, dressed in a sheepskin cloak with a live lamb draped over his shoulders, wanders between houses in the countryside, knocking on doors. He is shoeless, with a red cross painted on each foot and another traced across his forehead. According to tradition, he represents the figure of Sant Joan Baptista, and his task is to announce the arrival of the most important festivity of the year to the people of Menorca. He is like an ancient town crier, walking from street to street to make announcements on behalf of the public authorities. But he is not alone: he is accompanied by the junta de caixers, the riders, and the fabioler, who plays the flute on donkeyback to get the festivities started. Sam’s task is not an easy one, as s’homo des bé has to cover around 35 kilometres a year with a lamb on his back.

S/S 2024 Thelma

S/S 2024 Casi Myra

S/S 2024 Thelma

S/S 2024 Casi Myra

S/S 2024

S/S 2024 Kobarah

Kobarah Flat

S/S 2024

S/S 2024 ROKU

Casi Myra

S/S 2024

Casi Myra

S/S 2024

S/S 2024 Kobarah

Kobarah Flat

S/S 2024

S/S 2024 ROKU

Casi Myra

S/S 2024

Casi Myra

S/S 2024

Dina

S/S 2024

S/S 2024

Pix

Thelma Sandal

S/S 2024

Dina

S/S 2024

S/S 2024

Pix

Thelma Sandal

S/S 2024

S/S

S/S 2024

S/S

Edition

Brand Creative Director

Achilles Ion Gabriel

Brand Director

Gloria Rodríguez

Photography

Valentin B Giacobetti

Styling

Francesca Izzi

Illustrations

Angela Kirkwood

Copywriting

Davide Coppo

Production

Hotel Production

Special thanks to

Maria Barceló Pons

Chimera Sleepwear

Cristine Bedfor Hotel

Hauser & Wirth

Lessico Familiare

Miguel Ángel Martorell Mancebo

Álvar Ortega Alonso

Asja Piombino

Olivier Simille

Spaccio Maglieria

Via Piave 33

Image credits

© Valentin B Giacobetti

© Angela Kirkwood: pp. 77-88

© Fele La Franca, video stills: pp. 142-147

© Daniel Schäfer, © Carlos Torrico

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

© Josephsohn Estate. Courtesy the estate of the artist and Kesselhaus Josephsohn.

© Successió Miró, 2024

pp. 37-44

Print House

Artes Gráficas Palermo, Madrid

ISSN: 2660-8758

Legal Deposit: PM 0911-2021

Printed in Spain

Alcudia Design S.L.U.

Mallorca

camper.com

© Camper, 2024

Join The Walking Society