World Peanut Magazine ISSUE NUMBER / 08 JULY 2023 ARGENTINA PEANUT CHAMBER 08 / 2023

_ Will US Peanuts Save the Day in 2024 Following a Devastating Crop in Argentina? / 02

_ Science and Technology

Finding the Genes / 06

. A decade of progress thanks to the Peanut Genome Initiative

_ Bringing the Industry Together / 10

. Steve Brown, President of The Peanut Research Foundation, talks about ten years of scientific work for the development of the peanut sector worldwide

_ Translating DNA into product development / 18

. Janila Pasupuleti, a lead scientist at India’s ICRISAT, talks about the peanut genome research

Industrial Processing

Packing the Finished Product / 26

Peanut Market Data

Charts & Tables / 33

Peanut Farming

_ Keeping the Peanuts Warm / 36

. Mulching has been an effective practice in China for long, but other countries are now considering it

Market Trends

Peanut sustainability, consumption drivers & crop outlook

featured at 2023 International Peanut Forum / 40

01

index

Nº 08

Will US Peanuts Save the Day in 2024 Following a Devastating Crop in Argentina?

The occurrence of a bad crop every once in a while is not uncommon. In countries with significant agricultural production, the weather is constantly fluctuating, with factors such as flooding, droughts, wind, frost and other phenomena often impacting crop outcomes.

A variation of the crop in the plus or minus 10-15 per cent range is something that the market is generally prepared to handle. What is harder to bear, however, is a combination of unfortunate circumstances that lead to a 40 per cent decrease in production, as experienced by Argentina this year.

The list of factors that contributed to this distressing situation is quite extensive: a challenging start due to an unusually dry winter, inadequate rainfall during the first three months after seeding, a frost on February 18 (approximately 100 to 110 days from planting), further drought throughout the season, and two strong wind events that caused havoc in the fields where peanuts were cultivated.

This series of regrettable issues is indeed astonishing. It not only spells bad news for Argentinian producers, who are now

facing significant losses, but also has severe implications for the overall market, considering that Argentina holds a market share of over 70 per cent in European imports of blanched and raw peanuts. Currently, the pipeline connecting the two sides of the Atlantic Ocean appears to be coping, as shipments from previous crops in Argentina, along with assistance from the United States, are managing to cover at least a portion of the shortfall in peanuts. The crucial question that remains, however, is what will happen in the first half of 2024. The stock situation in southern hemisphere countries is relatively clear, placing the responsibility on peanut-producing countries in the northern hemisphere, primarily the United States. Reports suggest that planting in the US has increased by approximately 10 per cent compared with the previous season, but the ultimate yield is contingent upon the events that unfold in the coming months. All eyes will be on the American weather, as a crop failure in the US is the last thing the market needs. Let us hope for the best.

In this edition of World Peanut Magazine , we dedicate significant space to a momentous event for the future of peanut production: the ten-year milestone of the Peanut Genome Initiative. This initiative involved the sequencing of the peanut plant genome, paving the way for the development of powerful breeding tools and transforming peanut cultivation in the process. We had the opportunity to interview Steve Brown, President of The Peanut Research Foundation, and Janila Pasupuleti, a lead scientist at India's ICRISAT, to gain insights into this groundbreaking accomplishment.

Furthermore, we delve into the International Peanut Forum held in Lisbon, an immensely successful event that brought together over 350 peanut professionals from around the world in April. We also continue our exploration of peanut processing by examining packaging standards and procedures. Finally, we discuss the utilization of mulching, a widely practiced technique in China for peanut cultivation.

03

_ Market Trends

This section of the wpm deals with the dynamics of the demand and supply of peanuts in the international markets. We will try to keep track of the changes in peanut consumption in the main areas of the world, the factors that can affect production, and the price shifts of the various peanut products.

_ Industrial Processing

This area of the magazine focuses on shellers as well as companies transforming peanuts into consumer products. We will focus on current industry standards, quality issues, new technologies and the different industrial solutions adopted by producing countries. A special section will be dedicated to new products and tools for peanut processing developed by the best manufacturers.

_ Science and Technology

The activities of the universities and other research institutes engaged in scientific research on peanuts are of paramount importance for the future of the business. We will follow the main discoveries, from the latest issues concerning peanut genetics to the development of projects on pathogens or the impact of peanut consumption on human health. The consequences of scientific research on the future of the industry are hard to overstate, so we will be putting them in perspective in order to try to understand where the sector is heading in the long term.

04

_ Laws and Regulations

The Laws and Regulations section of World Peanut Magazine analyses the impact of new legislation and regulations affecting the production and trade of peanuts. The main issues treated in this section are governmental measures directly affecting international trade (such as the introduction of tariffs or quotas), health safety issues (such as the establishment of Maximum Residue Limits for certain substances) but also legislation impacting distribution, packaging and sales.

_ Peanut as a Superfood

This section offers peanut professionals news and insights into the world of peanut consumption and all its aspects. Typical news is related to findings concerning the nutritional values of peanuts, the impact of peanut consumption on human health, and the development of peanut-based food.

_ Peanut Farming

The primary production is where the peanut business starts, of course, so we will have a dedicated section for all events, activities, techniques and equipment related to growing peanuts in different parts of the world. The general idea is to bring farming in the producing countries closer to all peanut professionals so that they can have a better grasp of the business from a grower’s perspective and maybe on what the future of peanut farming may look like.

05

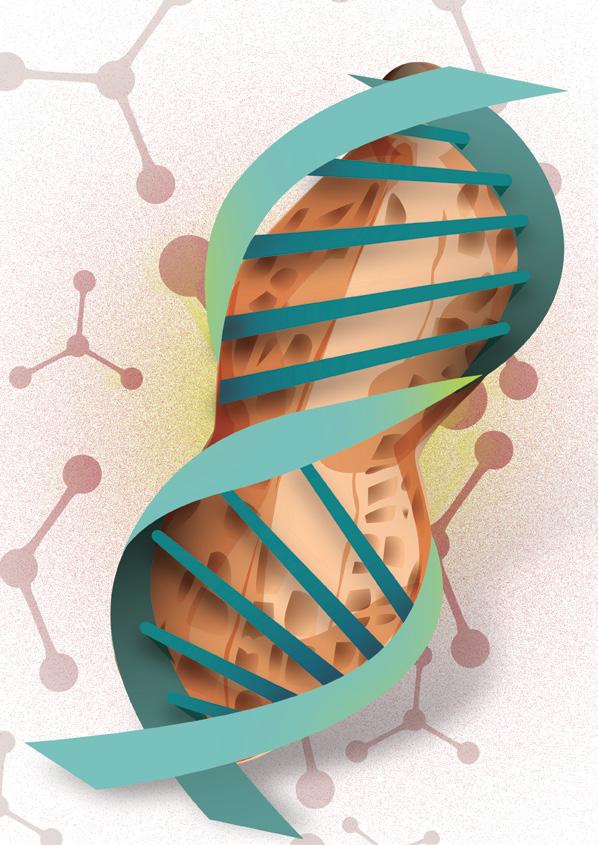

06 — Section — SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

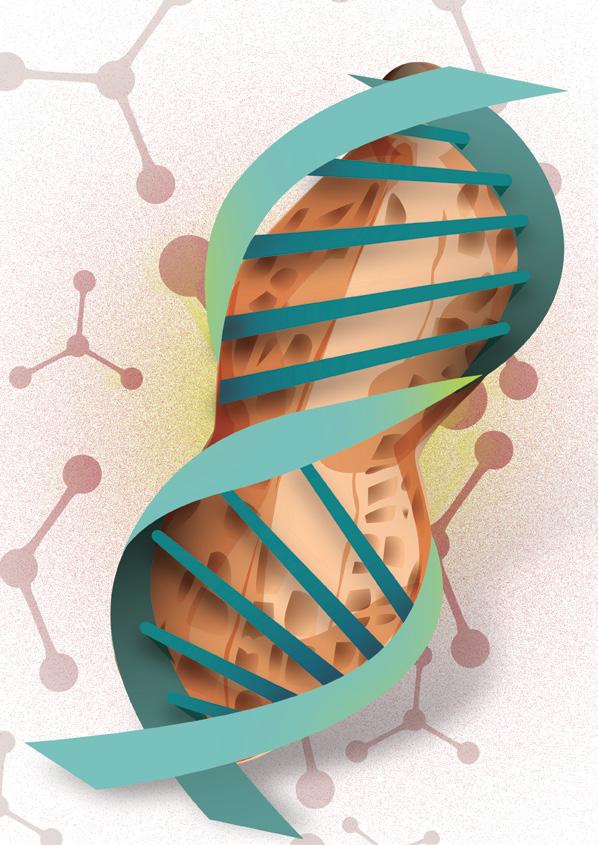

Finding the Genes

A decade of progress thanks to the Peanut Genome Initiative.

Ten years ago, The Peanut Research Foundation (TPRF) embarked on a groundbreaking endeavor known as the Peanut Genome Initiative. The objective was to acquire new insights into the genetic features of peanuts, with the ultimate goal of facilitating more efficient breeding programs. Now, after a decade of dedicated research, the publication of over 150 papers, and numerous domestic and international conferences, the foundation presents a comprehensive report on the achieved results and paves the way for a new chapter of research.

In 2003, the sequencing of the human genome paved the way for studying the genomes of other organisms, offering tremendous potential applications, including crop production. Several years later, TPRF initiated the first phase of the initiative and successfully raised six million dollars, making it the “largest research project ever funded by our industry”, as stated in the report. The costs were shared equally among growers, sellers and manufacturers.

07

The first phase, from 2013 to 2017, resulted in the sequencing of the genome of the wild diploid peanut parents in 2016. This groundbreaking achievement was published in the esteemed journal Nature Genetics. The second phase, the Peanut Genome Initiative II, successfully carried the program forward, culminating in the publication of the cultivated peanut genome sequences in the same journal in 2019.

The initiative has yielded invaluable knowledge across various fronts, with the most significant impact on the peanut sector likely being its ability to identify the genetic basis for peanut traits. This breakthrough provides an essential tool for breeders, enabling them to design programs more efficiently and rapidly through the utilization of genetic markers.

A noteworthy aspect of this research lies in its inclusivity. The genetic markers and other research findings are freely accessible on the website peanutbase.org, which has emerged as a central resource for geneticists, breeders and peanut researchers worldwide. The initiative has also rapidly evolved into an international collaborative effort, with the establishment of the International Peanut Genome Initiative Executive Committee. This committee has provided valuable guidance and direction to the project, fostering participation from organizations in the United States, Brazil, Argentina, China, India, Israel, Japan and Australia.

Markers

A genetic marker refers to specific segments of the genome that can be linked to particular traits, such as a plant's disease resistance or kernel size. By analyzing the DNA of a particular variety, it is possible to identify the presence of genes responsible for the desired trait, thereby greatly expediting the breeding process. Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) has emerged as an invaluable and potent tool for peanut breeders, facilitating their work and enhancing outcomes. Many genetic markers have been identified within the program.

_ Aflatoxin resistance

_ Arachidic acid content

_ Behenic acid content

_ Early leaf spot resistance

_ Gadoleic acid content

_ Late leaf spot resistance

_ Lignoceric acid content

_ Linoleic acid content

_ Oleic acid content

_ Palmitic acid content

_ Pod weight

_ Rood knot nematode resistance

_ Rust resistance

_ Saturated fatty acid

_ Sclerotinia resistance

_ Seed weight

_ Stearic acid content

_ Tomato spotted wilt virus resistance

_ Unsaturated fatty acid content

_ White mold resistance

_ Smut resistance

10 — Section — SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Bringing the Industry Together

Steve Brown, President of The Peanut Research Foundation, talks about ten years of scientific work for the development of the peanut sector worldwide.

11

// I understand that the major achievement of the Peanut Genome Initiative has been the sequencing of the DNA of both the wild and the commercial peanuts…

We’ve had two initiatives, really. The first was called the Peanut Genome Initiative, which was a five-year, $6-million investment by the industry. During those five years, we successfully sequenced the peanut genome. During the second phase, which we called Peanut Genome Initiative Phase Two, we focused on using these newfound tools for four research areas. The first was disease resistance, particularly leaf spot. The other areas were drought tolerance, aflatoxin mitigation and quality traits. Basically, what we’re pushing is this new technology called markerassisted selection. Back in 2012, when this work started, the industry leaders came together and decided that we were getting behind on breeding and we had to modernize it. At the same time people around the world were nervous about genetically modified organisms (GMOs), so with peanuts having a good reputation as a wholesome food, and being a kid’s food like peanut butter, the industry decided they didn’t want to try to market a GMO peanut, which I think was probably a wise decision at the time. Instead, we decided to use the genome to identify markers that breeders could employ in their breeding program. That would not lead to a GMO peanut but would facilitate breeding. So that’s what we’ve done. That has been the greatest accomplishment. There are more markers coming, and the breeders are putting them to work, gaining efficiency in their breeding process.

12

Steve Brown, president of The Peanut Research Foundation.

// From an organizational point of view, what would you say were the main challenges?

Well, just getting the industry together was a challenge. Getting everybody on the same page, to have a common goal took a little while. And that was done before my time, actually. Some of the industry leaders really jumped in there, made some phone calls, and said, “This is important. We’ve got to do this.” And then, of course, we must take into account that scientific research is a complex subject; it is hard to explain to somebody from the outside what exactly you’re doing. When you get proposals, research proposals from the scientist, they’re so technical and so hard for a layperson or a businessperson to really comprehend. So that’s always a challenge. Just trying to defend the decision on what projects you’re going to fund, and why this one is better than that one, has been quite a challenge. The foundation I work for, the Peanut Research Foundation, is an arm of the American Peanut Council, which is kind of an umbrella organization. There are many different peanut organizations, but this one includes everybody in the peanut industry: the manufacturers, the shellers, the growers, and all the allied industries as well. So, everybody comes together under that umbrella. We’re the arm that handles the research part of this sector. The board of directors I report to represents the entire industry; it’s a very diverse group and members have diverse needs. If you look at a manufacturer and ask, “What changes would you make to a peanut to make your product better?” he might say, “…Well, I want a more flavorful peanut, or I want one with more protein content in it.” The shellers might say, “I want one that shells easier, better shelling turnout.” The grower probably wants one with better disease resistance. So, each has different needs, and we had to convince everyone that not only is meeting your needs important to help you directly, but that when you help a grower to become more efficient and produce more peanuts, then it helps the entire industry and, indirectly, everybody benefits. So that’s been another challenge, and I think we’ve been successful in convincing people that, hey, you help one, you’re helping everybody.

13

// And what about the challenges from a scientific standpoint, if you had to mention a single issue that made the work of the initiative particularly difficult, what would it be?

When we first started this process, of course, we relied on some people with a lot of genetic expertise, and they warned us, “Hey, this isn’t going to be easy.” It took over a decade to figure out the human genome. It’s very complex, and the technology at that time was not like it is now; back then, it was very challenging. And when we started the peanut project, the methodology was still developing. Peanut is a tetraploid, which means it’s got four sets of chromosomes. This made it more complicated. Also, the peanut genome is very large; it has about 3 billion letters, about the same size as a human. It was always challenging, and it did take some tweaking. We went down some dead ends, and we had to back up and go a different route. But the technology available was improving. We started using new sequencing machines, and things just eventually fell into place. Eventually, also thanks to help from a company called HudsonAlpha, we managed to do the final assembly. You get these little snippets of the genome, you get little pieces, and then it’s like this huge jigsaw puzzle. You must put them all together in the right place. HudsonAlpha helped us do that. They told us at the time that it was probably the best tetraploid genome ever done at that point. It was really a high-quality outcome, and we were very pleased with the final product.

// An important aspect of the work is that the findings, the markers, are all published on the website peanutbase.org, and so it’s really available for all researchers and breeders. Was that a tough decision to make because ultimately the funding for the project came mainly from the industry…?

Yeah, that was discussed quite a bit, and there were two different angles: the first one is, “You keep it to yourself…It’s a competitive advantage and we paid for it, we’ll keep it.” But the other side was saying, “Well, we don’t really own it.” Besides we weren’t the exclusive funders of that research; there was funding coming from other sources, public funding from USDA, for example. And by the way, the original Peanut Genome Initiative was very international. We had scientists from all over the world participating. So, there was never a clear ownership. And I think the prevailing opinion, in the end, was that we don’t really own this intellectual property. If a private company had done this and they owned it, they would have clear ownership of the intellectual property and could charge for that technology. But we were opposed to that, nobody wanted to see their seed cost double because of some trait that was added in. So, if somebody discovers a marker, we publish it through regular publication, in a scientific journal. But then, once it’s published, it’s on the Peanut Base website. We encourage all the scientists we fund to get

14 — Section — PEANUTS AS A SUPERFOOD

it into Peanut Base as soon as possible so that the finding is in the public domain and no private company can own that technology. In terms of competitive advantage, you must also consider that traits vary according to geographical regions. Even here in the United States, a variety that does well in the southeastern US, where I am, does not do well in West Texas, and vice versa. Just because you have a marker for a trait, your work has just begun to get it into a variety that works for your area.

// Talking about international cooperation, I remember the meeting of the initiative in Argentina in 2017. There were researchers and scientists from China, India, and all the other peanut-producing countries. I imagine that must have been a challenge as well, getting so many professionals from different places to agree on things…

Nevertheless, it worked amazingly well. There were some glitches, of course, but it was a pretty cooperative group. Sometimes scientists tend to want to keep their cards to themselves and get credit for what they do, which is fine. But in this initiative, we said, “Okay, we have a common goal, you do this, I’ll do that, then let’s get back together and talk about it, and we’ll make a decision on which way to go.” That really happened. We had scientists from all over the world that took on different parts of this huge task and would report back what they found. In the end, the senior author for the final genome paper was David Bertioli from the US, but there were like 35 or 40 additional authors from all over the world. I wouldn’t say there was no jealousy at all, but amazingly there was very good cooperation.

// That’s good to hear. How do you assess the current situation in terms of international cooperation on peanut science?

I guess I’d have to say that the international group has kind of disbanded. I mean, there’s still collaboration on specific projects, people work with each other, but that particular entity is not there anymore. That doesn’t mean there can’t be collaboration, there is, but not across the board like it was. The international meetings were called AAGB, Advances in Arachis Genomics and Biotechnology. We funded those meetings for several years; we were having them annually and moved them all over the world. When COVID hit, we stopped, and, for three or four years in a row, we had no international meetings. But we are starting back up again this year. It is going to be at the HudsonAlpha building, the company I told you about, the one that helped us assemble the genome. It is a research institute in Huntsville, Alabama, and they’re going to host the AAGB meeting this coming October. I’m sure there’ll be people coming from all over the world to participate. So, the collaboration is still there, and I hope it continues.

15

// Of course, Aflatoxin for peanuts is a worldwide problem. How do you assess the status of the work on aflatoxin resistance? Can we be optimistic going forward?

The prevailing opinion of the scientists, back several years ago, when we started this, was that we had to control our expectations. They would say: “Look, some things are going to be easier than others.” We think we can do a pretty good job with some disease resistance, particularly, by the way, using some of the wild species. But they warned us that there were some traits that would be very difficult, if at all possible, and aflatoxin was one of those. Of course, aflatoxin is produced by the fungus, not by the plant. So, to make a change in the plant that would affect aflatoxin production is really a challenge. In time we’ve learned more and more about aflatoxin, but we really have gotten almost nowhere in terms of solving the problem. So recently, in my opinion, the genomic work that’s been done has provided some of the most optimistic data that I’ve seen in a long time. We’re certainly not telling anybody that we can make aflatoxin go away with genomics, but we do now have a couple of markers for areas on the peanut genome that control what happens with that fungal interaction. The interaction is a delicate dance between a fungus and a plant. Under certain stress conditions, the plant sends out a signal, the fungus responds, the plant responds with a defense mechanism, and then the fungus overcomes that. It’s back and forth. It’s a very complex metabolic system that’s going on and we are just starting to understand. But there are certain genes within the peanut plant that can help that metabolic signaling that goes on. Some of our researchers have found some of those markers. We don’t know yet how important they are, how much of the variation in aflatoxin and contamination is controlled by those markers, and there are many other factors going on, but it’s under testing right now. We have at least one breeder that’s already got it in his breeding program. He’s looking at it, trying to find varieties that will be less conducive to aflatoxin. It’s very encouraging to me that there’s finally a path that we think might make some headway.

// Before you mentioned GMOs. Many people believe that GMOs can indeed bring many advantages to peanut production and consumption. In this case, the challenges can be considered more and more in terms of public relations than strictly scientific research. What do you think?

I think it’s going to take some time. Yes, you’re right, it’s a marketing issue more than a scientific one. I don’t know of a single scientist that thinks there’s anything harmful in a GMO peanut or a GMO anything. But when it comes down to marketing, there is a negative perception. I don’t see the industry saying, yeah, give me a GMO peanut right now. I doubt that can happen. But there’s another issue: gene editing. GMO means that you’re taking genes

16

from another totally different organism, and you’re bringing them into the peanut, or soybean, or corn plant. All this is very common, of course, with the major acreage crops. Cotton, for example, has BT cotton, which uses genes from a bacteria; it produces a toxin to repel certain insects. Those types of traits come from other organisms. Gene editing is when you actually alter a gene that already exists in the species. You can make a tweak on that gene and possibly turn it off, or turn it on, to create some new trait. Maybe this procedure can be a little more palatable to the public. Although some are still wary of gene editing as well. The European Union has been the one area with stricter standards on this issue. But from what I read, the European Union is at least considering gene editing as being something they could accept. It’s not official yet, but I see that coming down the road. Maybe the pressure will mount and the scientific evidence will demonstrate that these things are safe. When? I don’t know. But a lot of crops are already investing heavily in gene editing, and there are some amazing things that are being done. The fear is that maybe we’re getting a little behind in peanut. Maybe we’re being too conservative and need to be investing, so we can be ready to deploy some of this gene editing technology when the time is right.

// Is there anything you would like to add about the initiative going forward?

Well, one thing is that we really want input on how to go forward. We are actively seeking input from our members, from the US peanut industry. But I would welcome input from the rest of the world as well. Another important issue for the future, for example, is the traceability and segregation of peanuts. As we develop more and more sophisticated peanut varieties that have certain traits, the product gets diversified. We realize that there will never be one variety of peanut, the variety depends on what the market wants. So if we’re successful in all these breeding programs and we come up with really improved varieties for different markets, then all of a sudden, we will have maybe a slate of six or eight different peanuts out there, different varieties that are going to different markets. That means more segregation. And that scares the heck out of the shellers because they’re already having to segregate high-oleic peanuts from non-high-oleic for their customers, who don’t want to mix them. This is going to be an important issue as we become more successful in peanut breeding. That means we’re going to have to keep all these things separate for the different markets. Just another thing to keep in mind.

17

Translating DNA into Product Development

Janila Pasupuleti, a lead scientist at India’s ICRISAT, talks about the peanut genome research

// Please introduce yourself, Janila. I’m a plant geneticist by training, and by profession I do peanut breeding, and this is my twelfth year at ICRISAT. In addition to that, I have a role as a cluster leader, as I oversee the breeding of six crop commodities for ICRISAT. We have three cereals and three legumes, including groundnut, spread across Asia and Africa (both Western and Southern Africa) and a total of 15 breeding programs.

// How would you characterize your contribution to the genome initiative? I should say that I have both contributed and benefited; not only on behalf of ICRISAT, but also for the national programs in Africa and Asia, by using these new genomic tools in the breeding programs. We can now develop the varieties which are required for both markets and production ecologies. I’m basically in the business of translating the advances, the new tools, into product development. That’s my role and that’s how I have been engaging with the partners from both the US and China, as well as with the national program partners in Asia and Africa with whom we work. Of course, I also contributed to the initiative from a technical aspect, in terms of providing guidance, oversight and then giving technical feedback; particularly, again, by translating the use of tools into the final products.

// Did you participate in all the international meetings within the initiative? I did. We are talking about the meeting we called Advances in Arachis Through Genomics and Biotechnology. I participated regularly, and, in fact, I was the one who spearheaded expanding the scope of this work beyond genetics, to make sure that we considered the agronomic issues. That’s because some of the toughest problems, like aflatoxin contamination, will probably not find a solution from genetics only, but also from agronomy and post-harvest management. I know that Steve Brown is also a big fan of this kind of focus and so is David Jordan. The next meeting is going to be in October.

// Right, it is going to be held in the US, in Alabama. We were going to meet during 2020 but then the event was canceled because of the Covid pandemic.

// You mentioned aflatoxin. We talked about it a little bit with Steve Brown and, as you anticipated, he agrees with you that it is a particularly difficult problem to approach because it’s not just the genetics of the plant, but how the plant interacts with the fungus that creates the aflatoxin. So what’s your assessment? Do you think in the future it’s going to be possible to figure out prac-

20 — Section — SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

tical solutions? Yes, aflatoxin is definitely a global problem, and it’s not only a health concern for the consumers, but also a trade concern; a lot of consignments get rejected and that has a significant economic impact. I fully agree with Steve; it can’t just be handled by genetics alone, because the infection can also happen in the post-harvest phase, not necessarily when the pods are attached to the plant, during the processing, in storage, and during the transport. That’s why I think a holistic approach would be very important. We must start off with good agricultural practices; when the crop is being harvested good drying, storage and transport practices. While we do that, monitoring the contamination along the value chain is essential. We should set up an entire ecosystem and build it around peanut production to address this very important problem. Now some countries also use prediction methods, because contamination depends on the interaction between the plant and the fungus, and a lot of this process is affected by the environment, so you can predict that the crops coming from a certain area, depending on the weather, the rainfall temperature, and other variables, bear a likelihood of contamination or not. Of course, genetics has a major role and ICRISAT is investing heavily in it. For example, in the past, we have developed screening protocols and then we moved ahead to develop genetic research as well, and now we are trying to understand the candidate genes which at least give some level of association with the resistance. In this fashion we are ready to move ahead with gene editing and make use of all the modern tools available to address, at least to some extent, this problem.

// Going back to the Peanut Genome Initiative, which just concluded ten years of work, the breakthrough was the sequencing of the genome, both wild and commercial species. But, in general, how would you characterize the work of the initiative, and its relevance? I I mean let me put it this way: unlike crops like rice, wheat, corn and others, in which a lot of investment has been done and a lot of genomic resources are available, peanut is almost like an orphan crop. That was until the peanut genome initiative came in, not only with the US funding but also from other donors as well; ICRISAT, for example, has also invested to reach common goals. Having a DNA sequence is to have a baseline so one can work on it. Establishing the genome sequences of the progenitor species Arachis ipaenensis and Arachis duranensis and then the cultivated species is one of the biggest contributions of the Peanut Genome Initiative. This work enables researchers to identify the genes or the genomic regions for the trait of interest; it could be high oleic, it

21

could be drought resistance, or disease resistance, whatever. That association between the trait of interest and the genome can be fully established only when you have this genome sequence. This breakthrough has opened the floodgates; different researchers are now enabled to develop flanking and diagnostic markers, which we can actually use in the breeding programs to develop the product which is the cultivar. The genome also brought a lot of understanding of the plant itself, its evolution, and how its adaptation developed over time.

// Which markers would you assess are the most important ones for the development of production in general? The most important ones, I would say, are the ones related to foliar fungal diseases: leaf spots and the rust, because these diseases are of global importance, and they can bring down yield if the disease is very severe. At ICRISAT, we define “product profiles” and have categorized resistance to foliar fungal diseases as a “must-have trait”, so we won’t advance any product that does not have a level of resistance. If I take the example of my own breeding program, we could mainstream these foliar fungal disease resistances into our breeding pipeline thanks to the DNA-markers, so that’s the first one. But other markers are important as well. Using DNA-markers, ICRISAT has developed high-oleic acid peanut lines and together with partners in India commercialized the first higholeic acid peanut varieties, Girnar 4 (ICGV 15083) and Girnar 5 (ICGV 15090), in 2020 in India. Subsequently, Spanish-type high-oleic acid peanut varieties, GG 40 (ICGV 16668) and GG 39 (ICGV 16697), were commercialized in India in 2022-23. The high-oleic acid peanut lines developed by ICRISAT were shared and are being tested by collaborators in Bangladesh, Myanmar, South Africa, Malawi, Mali, Nigeria and New Zealand for commercial release.

// One thing that impressed me about the initiative is the scope of the international cooperation: so many countries, so many institutes and researchers and universities participated. I don’t know if this is so common in scientific research in agriculture. What is your opinion? Yes, the collaboration which has gone into the initiative has been fantastic. Once you have the genetic sequence available you can go ahead with research in different specific areas. At ICRISAT, for example, we developed an array with 58k SNP markers which anyone around the globe can use. And similarly, the University of Georgia has developed a 48k array which, again, anybody can use. Right now, we are working on a new array with a different concept which would be very cost-effective; the arrays now available cost around 38 dollars, and this one would cost only about 8 to 10

22 — Section — SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

dollars, making it available also for developing countries. This has been a fantastic international collaboration. I should mention that these kinds of international collaborations do exist for other crops, but wherever it exists it’s mostly through the CGIAR (Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research) initiatives. To have the CGIAR engaged, I think that enables the research to be trickled down to be used for a vast number of researchers across the globe.

// Let’s talk about genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Possibly peanut scientists did not really work a lot on GMOs, perhaps with the perception that the public may not want to go in that direction, even though, from a scientific standpoint, it is possible to argue that there is no such thing as a health risk. Do you think this will change in the future? Especially if we consider that big advantages can come from the development of GMO science for peanuts. As a researcher, I do fully agree that it is a very powerful technology, particularly for the traits which we are not able to handle with the current available genomic or genetic resources. I think that for aflatoxin we may have to move toward GMOs. While we are having these conversations and debates, some progress is happening; we have now a new tool called genome editing tool, I think you are aware of it. That gives another opportunity to researchers to develop these edited products and gene editing does not have the same negative perception as GMOs. More countries have deregulated their gene editing products, so I think that could be a very good opportunity for the future. Having said that, we have to consider that for gene editing to be successful, we need to have a good understanding of the candidate genes; it is fundamental to have clarity. With the genome sequence which we have right now, in a couple of years, we would be at a stage where we can have these edited products, with the additional advantage that we could validate whether this candidate gene is really responsible for the intended trait we are looking for or not. So, there are two powerful applications: one is to really see whether the candidate genes really are the real candidates for the targeted intended trait; the second is for the development of the product itself.

ICRISAT is one of the world’s most important centers of research in peanuts. What are the current priorities of this institute? One important focus is product development, which is the variety of development for the target countries in Asia and Africa. We work alongside the national program partners. Everything starts off with defining the market segments for a particular country that the breeder is interested in. We also work with our national partners so that they can

23

//

use these tools in their breeding programs to enhance selection efficiency. We then test these lines across the different locations and make decisions based on the data we generate. This data is stored in an institutional repository available to researchers. A very important area of focus, as I said, is aflatoxin. Today, for example, we just had a brainstorming session for four hours on this very topic; we all sat together and looked at the results of different streams of science and then discussed what we are going to do next, and how we are going to address this problem. If aflatoxin is the first area of focus, the second one, I would say, is diseases such as stem rot disease; soil bone diseases like stem rot are a big growing challenge. But we are also thinking about smut disease; at the moment smut is confined to South America, but it could spread in the next decade or so, and as a global institute, it is important that we anticipate the problem. Another area we are looking at closely is drought tolerance. Especially for those countries where drought is becoming very severe and, in some cases, combined with heat as well. Another element of focus is product quality; high-oleic acid oil is a very important feature, so is the amino acid profile. In general, we ask what is that profile which the industry is looking for.

// Great! Is there anything you would like to add? A current concern is the free exchange of germplasm internationally. In some cases, sovereign countries are limiting the exchange of germplasm among collaborating researchers, and I think that’s slowing down progress. Let me remind you of the paper you have covered in your magazine by Soraya and David. In many cases we received genetic material from abroad and then developed it and spread the new variety across all the countries; everybody has benefited from it. Of course, we must find the right balance between country-based intellectual property and human intellectual collective property so that we can have a flourishing international collaboration.

24 — Section — SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

25

26 — Section — INDUSTRIAL PROCESSING

In previous issues of World Peanut Magazine, we have covered the various steps of peanut processing up to the point where the product is ready to be shipped. It is now time to cover how the peanuts are packaged before they can be sent to the customers: the size of the packaging solutions, the materials, and how these vary across the producing countries.

Many of the details concerning packaging are negotiated between the seller and the buyer and various issues determine the outcome:

_ Customers’ specific requests

_ Packaging availability in the origin country

_ Size standards

_ Container size availability (40–20ft)

_ Weight restrictions at origin or destination country

_ Transit times

_ Route to follow (a significant choice here is whether the route crosses the equator or not, due to the impact it has on potential condensation)

_ Type of product to pack (raw peanuts, blanched, inshell, or roasted)

In this article we will try to thoroughly address the widest adopted options in the different peanut-producing countries.

27

Type and sizes

There are three main ways to pack peanuts based on size:

2.

3.

Labor and weight restrictions

Within the peanut trade, in the vast majority of cases either bigbags or bags are used, while the rules in the countries of destination play a major role in deciding for one or the other.

In some countries there is a prevailing trend toward minimizing labor costs, and bigbags are a very good option here. In other places, on the contrary, local government regulations are designed to maintain some traditional practices, like the use of smaller bags, as a way of not eliminating jobs for the local communities.

Another element to consider is weight restrictions at origin or in the destination countries. There may be a maximum truck gross weight allowed for circulation on certain roads, which, of course, limits the maximum load in the container.

28 — Section — INDUSTRIAL PROCESSING

— 50 KG 25 KG

Bigbags or totes — 1250 KG 1000 KG 1090 KG (2.400 lb)

Bags

1.

— 909 KG (2.000 lb)

Bulk Bins

10’ CONTAINER

Payload

30,000 lbs

Tare weight

3.500 Lbs.

Cubic capacity

Exterior Dimensions

L. 10’

W. 8’

H. 8’6”

Interior Dimensions

L. 9’ 5”

W. 7’8” -1/8”

H. 7’9” -5/8”

20’ CONTAINER

Payload

48,600 lbs

Tare weight

5.015 Lbs.

Cubic capacity

Exterior Dimensions

L. 20’

W. 8’

H. 8’6”

Interior Dimensions

L. 19’ 5”

W. 7’8” -1/8”

H. 7’9” -5/8”

40’ CONTAINER

Payload

80,350 lbs

Tare weight

8.377 Lbs.

Cubic capacity

Exterior Dimensions

L. 40’

W. 8’

H. 8’6”

Interior Dimensions

L. 39’ 5”

W. 7’8” -1/8”

H. 7’9” -5/8”

Container size

A very important element to consider when designing the peanut-packaging strategy is the type of container to be used, especially its size. Every container has a maximum allowed weight and space availability as shown in the table below.

10ft containers are not commonly used for peanuts. In practice, 20ft containers can be loaded at full capacity only with bags, using bigbags is not convenient due to sub-utilization of the space (only 10 bigbags totaling 12.500kg vs 19.000kg with bags). With 40ft containers the situation is completely different; they cannot be loaded at full capacity due to weight restrictions in the majority of the countries, leading to a maximum load in the 25-28.000kg range.

In conclusion: if the customer requires 25-50kg bags, both 20 and 40ft, containers can be used (20 footers with 18-19Tm of peanuts and 40 footers with 25-28Tm of peanuts). In case the customer wants bigbags, although both options are possible, a 40ft container is the best option, giving the cheaper freight per Tm of peanuts (20-footer with 10-12 Tm of peanuts, or 40-footer with 24-25 Tm).

29

8,6’ 10’ 8’ 8,6’ 20’ 8’ 8,6’ 8’ 40’

Materials

Another aspect to consider is the packaging material.

As for the bags, the options are: jute, plastic and paper.

The bigbags are essentially all made of polypropylene fabric with different characteristics in terms of:

_ Type of fabric: standard type, coated type, breathable type

_ Density of the fabric

Type of fill and discharge spouts

_ Type of handling loops

_ Safety factors

Food-grade fabric and paints (if there is any printing)

_

Bulk bins are used for specific purposes within the US, as they require special installation for loading and dumping the peanuts.

Standardization

Different peanut-producing countries have worked on the standardization of bigbags, aiming to reduce variabilities between suppliers, with all the benefits associated.

In the US, for instance, the American Peanut Council has developed a specification standard for the bigbags as a guideline for the American peanut processors.

The Argentina Peanut Chamber is working to define a common specifications set for the 1250kg bigbag.

30 — Section — INDUSTRIAL PROCESSING

Packing systems

Once the packaging is chosen, another aspect to evaluate is the technical process to perform the filling.

There are different options ranging from manual procedures up to very sophisticated and automatic systems, with many solutions in between.

In all filling systems there are some fundamental points to cover:

_ Packing the product in a gentle way to avoid splitting

_ A scale should be employed to ensure the correct weight in every packaging unit

_ Proper closure of the filling spout (or proper stitching in the case of bags)

_ Proper identification of every packaging unit, including, at a minimum, lot number, producer information, country of origin, weight, type of product.

Some pictures of filling equipment can be seen below:

31

China

JANE ZHENG, from QINGDAO SHENGDE FOODS CO LTD, talks about packaging habits in China.

“Blanched and HPS peanuts are usually packed in same way in China, whether they are shipped abroad or to local customers. The most popular bag is the 25kg vacuum bag made of woven plastic; it has the great advantage of keeping the product fresh during transportation. This item replaced the jute bag, which was widespread until the year 2000. In summer the totes (carrying weights starting at 650kg) are also often prepared with vacuum. The non-vacuum totes, used mostly during winter, range from 850 and 1,250kg. Certain European markets, like Spain, require a special packaging: two 12.5 kg bags in a carton of 25kg in total. It is an expensive way to pack peanuts, and it makes sense for high-end products. To Japan, many companies ship 25kg cartons without vacuum; the trip is relatively short and Japan prefers to avoid vacuums for environmental reasons. Jute bags, in the 25 and 50kg format, are also used for shipment to Japan. Peanut producers also provide tailored packaging, in the 300 grams to 5kg range, for all kinds of peanuts based on buyers’ requirements for Korea, Japan and some European markets. The packaging of inshell peanuts is done either with tote bags, starting at 850kg, with plastic bags in the 15, 25 and 30kg format, or 15kg vacuum bags.”

Brazil

ROBSON FONSECA, from Coplana, tells us about peanut packaging in Brasil:

“Our main export markets are Algiers and Russia, and those markets usually demand 25 and 50kg bags. In some cases, we also ship using 1,250kg bigbags. I would say that about 98% of all peanuts end up travelling between these two types of packaging. Vacuum bags are also in use, for instance at Coplana; we can say it is a Brazilian standard.”

— USA

PETER VLAZAKIS, American Peanut Council, explains the US standars.

“APC has established a system to certify suppliers of tote bags that meet the defined specifications, although use of APC spec bags is ultimately voluntary. The vast majority of blanched and raw shelled kernels are transported in 1 metric ton (2,200 pounds) polypropylene tote bags.” The APC specs can be accessed here: link

—

Argentina

JAVIER MARTINETTO, Argentina Peanut Chamber, tells us about current trends in his country

“Almost all exports from Argentina to Europe are shipped in 1250kg bigbags for both raw and blanched peanuts. Jute bags practically disappeared; however 25 and 50kg plastic bags are still in use for certain destinations, mainly Russia and Algiers. Shellers are working on automated packaging systems due to legal restrictions concerning the maximum weight workers can handle.”

32 — Section — INDUSTRIAL PROCESSING

33 charts tables

peanut exports of brazil - kernels (mt)

2022 2023

50.000

40.000

30.000

& 10.000

60.000 2022 2023

20.000

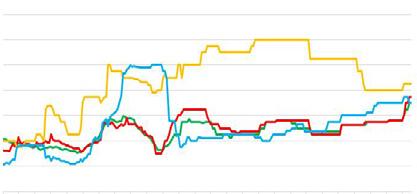

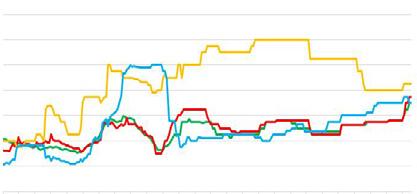

eu 27 imports, tm (shelled - 1202.42) -

eu 27 imports, tm (prepared hs 2008.11)

china future prices (settle value - rbm)

34 — Section — PEANUT MARKET DATA

11.000 10.500 10.000 9.500 9.000 2022 2023500 1.000 1.500 2.000 2.500 3.000 3.500

peanut exports of argentina - kernels (mt)

35

mintec benchmark prices for peanuts delivered to rotterdam. Courtesy of Mintec Global Source: Mintec Benchmark Prices10.000 20.000 30.000 40.000 50.000 60.000 70.000 80.000 2022 2023 2,400 2,200 2,000 1,800 1,600 1,400 1,200 1,000 S/ mt 20192 021 2022 2023 Peanut 40/50 (AR) CIF R’dam (MBP) [Mintec Code: 1S01] | Peanut 40/50 (BR) CIF R’dam (MBP) [Mintec Code: 1S02] Peanut 40/50 (CN) CIF R’dam (MBP) [Mintec Code: 1S03] | Peanut 40/50 (US) CIF R’dam (MBP) [Mintec Code: 1S06] 2020

Mulching has been used effectively in China for a long time, but other countries are now considering it.

— Section — INDUSTRIAL PROCESSING

Mulching, a traditional practice predominantly used in cold weather regions and labor-intensive crops, has been successful in China for a considerable period. Now, other countries are also considering the adoption of this technique.

Mulching, defined as the application of decaying organic material, such as leaves and plant residues, in the soil, provides fertilizing properties. While this technique is not widely practiced in peanut-producing nations globally, China stands out as the largest peanut producer, accounting for approximately one-third of the total yearly peanut production. The term “mulch” typically refers to a layer of protective material, such as plastic or various fabrics, applied to the soil during seeding. The specific method of mulch application varies based on the crop type and environmental conditions, with the primary goals being plant protection, optimization of organic material’s fertilizing effect, and prevention of weed growth.

China has long embraced film mulching for peanut cultivation, yielding excellent results. The use of plastic films contributes to maintaining optimal plant temperature and suppressing weed competition. Initially practiced in the provinces of Shandong and Henan, where peanut cultivation originated, the technique gradually expanded to the northern provinces as peanut production shifted.

37

Presently, approximately 80 per cent of peanut crops in China employ mulching. This technique is avoided during the summer months, however, when excessive heat could hinder proper plant development. Furthermore, hilly areas in Liaoning province, characterized by challenging soil conditions for mechanization, primarily rely on manual planting and harvesting. The higher temperatures allowed by the films usually have a positive effect on the development of the plant, leading to an earlier harvest and better yields, especially in China’s northern regions, where frost can be a serious threat for peanuts.

One additional advantage of mulching is its ability to retain more water around the remnants of previous crops, akin to the effects of direct seeding in Argentina. This water-retention property, coupled with its effective prevention of soil erosion, establishes mulching as an environmentally friendly technique. Chinese farmers prioritize the collection and proper disposal of plastic mulch immediately after harvest to maintain the sustainability of this practice. In a few cases, growers even use biodegradable films to enhance the sustainability of the technique; as proper technologies help reduce the cost of biodegradable materials, we could see a higher percentage of such films deployed for mulching.

38 — Section — MARKET TRENDS

It seems that China's leadership in peanut mulching has attracted the attention of other countries. A recent study from researchers from Vietnam found that, thanks to mulching, “the plant growth parameters (germination rate, growing time, plant height and number of branches per plant), leaf area index, the number of nodules per plant, dry matter accumulation, yield components and yield of peanut were much higher than those of no-mulch control. Among the mulches, plastic mulch was found superior to straw mulch in the pod yields and water-use efficiency and moisture conservation, and thereby can be considered a reliable practice for increasing the productivity of peanut on the coastal sandy land in Nghe An province, Vietnam.” (Effect of Mulching on Growth and Yield of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) on the Coastal Sandy Land in Nghe An Province, Vietnam | Link).

Agronomists from India also explored the impact of mulching on peanut productivity and sustainability, with encouraging results. They found that mulching significantly influenced the yield and yield attributes of peanuts, showcasing its potential as a beneficial agricultural practice.

39

40

2023

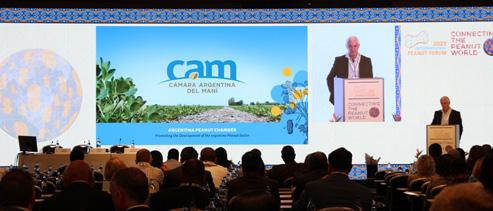

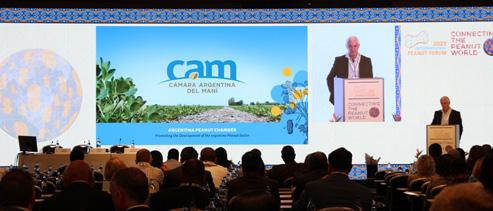

Peanut sustainability, consumption drivers & crop outlook featured at 2023 International Peanut Forum.

'Connecting the Peanut World,’ was the theme of the 2023 International Peanut Forum, which more than lived up to its global moniker. More than 330 delegates from 35 countries converged in Lisbon, Portugal for the industry’s premier event, from April 26-28. The IPF is the only forum where peanut industry leaders from around the globe gather to make connections and conduct business around vital peanut issues. Peanut farmers, shellers, exporters, brokers, dealers, manufacturers and service suppliers from around the world attended.

The 2023 conference focused on sustainability, consumption drivers, using peanuts to fight malnutrition and the popular peanut supply snapshot, which was expanded this year to seven peanut growing origins.

41

The conference kicked off with a panel on sustainability, with voices from each step of the supply chain. Veerle Poppe from the Colruyt Group, a retail chain in Belgium; Irene Moreno with Importaco, a leading snack manufacturer in Spain; Edoardo Fracanzani with the Argentine Peanut Chamber; and Richard Owen with the American Peanut Council discussed sustainable practices and initiatives that their respective organizations are involved in. Topics included strategic peanut sourcing, recycling peanut shells and smarter irrigation practices. Owen highlighted APC’s Sustainable U.S. Peanut Initiative, a U.S. industry-led grower data collection program that’s helping provide the foundation to tell the industry’s sustainability story. Fracanzani highlighted the Chamber’s initiatives to promote the sustainable practices in the sector, for example the adoption, by most members, of the Farm Sustainability Assessment standard.

Afterward, delegates heard from global experts in a carefully curated lineup of speakers and topics on nutrition, messaging, niche peanut products and other consumption drivers. Dr. Samara Sterling, from The Peanut Institute (USA), delved into peanut nutrition messages that drive

42

consumption. Tessa Schoones, from Innova Market Insights (Netherlands) discussed keys to turn on consumer demand. Rounding out the afternoon session, Stu Macdonald, from ManiLife (UK), did a case study on his company’s niche peanut butter, which saw success by bucking the trend and charging twice as much as the competition, with a result of increased market share.

The following day began with a session on feeding the world, both as a cause and a business opportunity. Led by Erwan Chapuis and Monique Chan Huot from Nutriset (France), the discussion focused on fighting malnutrition with peanut-based life-saving foods.

Capping off the conference, the ever-popular peanut supply panel featured delegates from Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Nicaragua, South Africa and the United States discussing supply and projections for the upcoming crop. Delegates learned about current crop conditions and a 2023 forecast from Diego Bracco, Camara Argentina del Mani; Robson Fonseca, COPLANA (Brazil); Peng Zhang, Qingdao Peanut Import & Export Association (China); Nilesh Vira, IOPEPC (India); Joaquin Zavala, Comasa (Nicaragua); Wessel

43

Aside from two days of conference sessions, delegates had the opportunity to meet and engage with exhibitors from across the globe about their products and services, ranging from manufacturing and shelling, to packaging, transportation and more. Receptions, meals and coffee breaks also brought delegates together to network.

IPF organizers thank the following 2023 sponsors: Birdsong Peanuts (gold); AgroCrops Singapore and Tomra Food (silver); AmSpec and Golden Peanut (bronze); Premium Peanut, Comasa, Innova Market Insights, Mazur and Hockman, and JLA International.

Planning for the 2025 IPF is currently underway, with dates and location to be determined.

Higgs, Triotrade Gauteng Pty Ltd. (South Africa); and Collins McNeil, MC McNeill & Co. (USA).

Higgs, Triotrade Gauteng Pty Ltd. (South Africa); and Collins McNeil, MC McNeill & Co. (USA).

44

This issue of the World Peanut Magazine has been completed thanks to the efforts of:

Steve Brown USA

The Peanut research Foundation

Tracy Grondine USA

American Peanut Council

Peter Vlazakis USA

American Peanut Council

Janila Pasupuleti India

ICRISAT

Robson Fonseca Brazil

Coplana

Jane Zheng China

Qingdao Shengde Foods Co. LTD

Kishore Tanna India

IOPEPC

Gabriela Alcorta

Soledad Bossio

Javier Martinetto

Nicolás Cantoro

Martín Gonzales

Edoardo Fracanzani

Sebastián Della Giustina

Argentina

cam (Argentina Peanut Chamber)

Graphic Design and illustrations. Sebastián Della Giustina. Carolina Gaitán. ese-estudio.com.ar · @ese.estudio.ok

Typography. Journalist by Sergio Rodriguez / Cantarell by Dave Crossland / Work Sans by Wei Huang / Noto Sans / Pictures. Image by efe_madrid on Freepik

Cámara Argentina del Maní

20 de Septiembre 855 “A”.

(X5809AJI) General Cabrera · Córdoba, Argentina

Tel +54 358 4933118

cam@camaradelmani.org.ar

www.camaradelmani.org.ar

Higgs, Triotrade Gauteng Pty Ltd. (South Africa); and Collins McNeil, MC McNeill & Co. (USA).

Higgs, Triotrade Gauteng Pty Ltd. (South Africa); and Collins McNeil, MC McNeill & Co. (USA).