April 2025 • Volume 13 Issue 4

We are delighted to share with you C Magazine’s first ever themed issue! The C Mag staff has been dreaming of creating a special issue for over five years. We chose to discuss the environment because it is not only a broadly pressing matter but also a central topic in both arts and culture stories from nearly every issue we have created. So, after an exhaustive, collaborative brainstorming process where we sought to produce the issue that would leave the greatest impact on our Paly community, the “Eco Issue” was born. Thank you for supporting us to reach this point, and we hope reading this edition will be as touching for you as it was for us to create.

Opening the issue, “No Place Like Home” on page 6 explores the deep connection Indigenous communities have with their ancestral lands and the lasting impacts of colonization, displacement and environmental destruction. Written by Kaitlyn Gonzalez Arceo, Silvia Rodriguez and Sophia Zhang, this piece highlights the ongoing efforts of many passionate individuals at Paly who bring light to protecting Native culture and land for future generations.

In response to growing anxieties about the environment’s health, “My Therapist Says it’s the Planet.” written by Estelle Dufour, Maia Lin and Amalia Tormala on page 15 explores the impact of climate change on youth mental health and how people can channel their fears into advocacy. Tormala expands on this issue in her perspective “Leave Nature Alone” on page 19, detailing the unforeseen consequences of government policies on national parks which threaten their accessibility and sustainability. She reflects on her personal

connection to these spaces and emphasizes the urgent need to protect them for both people and the planet.

This issue’s poster on page 24, a photo illustration created by Talia Boneh using photos by Anika Raffle and Gin Williams, shares the beauty of nature found in the Bay Area. The saying “we breathe in the air we create,” written by Anika Raffle, aims to reflect a central message from the issue: that our action or inaction today directly contributes to the environment we will live in tomorrow.

Stepping into spring, senior Leo Terman, this issue’s featured artist, expresses his creativity through the art of flower arranging. “In Full Bloom,” by Talia Boneh, Ria Mirchandani and Ellis Shyamji on page 36 explores how Terman’s passion allows him to bring beauty and comfort to others while supporting local environmental efforts.

As we step down from our roles as Editors-in-Chief, we want to express our deepest gratitude to our incredible staff, readers and everyone who supported our journey along the way. We have grown so much while creating the last five issues, and we are so proud of everything we have accomplished together. While this may be our final issue in these roles, we know that C Magazine is in amazing hands and will continue to thrive with our next leadership team. Thank you for being part of this experience with us — we can’t wait to see what the future holds and the talented voices that will shape it next.

Happy reading!

Kayley Ko, Katelyn Pegg, Anika Raffle and Gin Williams

Maruwu Seicha Review

By Sonya Kuzmicheva

By Zoe Ferring

Eva Arceo

Aidan Berger

The Boneh Family

Cindy Brewer

Yi Cao

Pei Cao

Jennifer DiBrienza

Linda Farwell

Ryan Greenfield

David Karel

Binoo Kim

Grace Ko

Kirill Kuzmichev

Jesse Ladomirak

Geunhwi Lim

Yueun Lim

Perry Meigs

The Pegg Family

Carol Replogle

Diego Rodriguez

Vimal Shyamji

The Sheffer Family

Vijayashree Srinivasan

Greg Williams

Allison Wong

The Williams Family

The Yeni-Komshian Family

Publication Policy

C Magazine, an arts and culture magazine published by the students in Palo Alto High School’s Magazine Journalism class, is a designated open forum for student expression and discussion of issues of concern to its readership. C Magazine is distributed to its readers and the student body at no cost.

Printing & Distribution

C Magazine is printed 5 times a year in October, December, February, April and May by aPrintis in Pleasanton, CA. C Magazine is distributed on campus and mailed to sponsors by Palo Alto High School. All C Magazine stories are available on cmagazine.org.

Advertising

The staff publishes advertisements with signed contracts, providing they are not deemed by the staff inappropriate for the magazine’s audience. For more information about advertising with C Magazine, please contact business manager Lily Jeffrey at businesscmagazine@gmail.com.

Editors-in-Chief

Kayley Ko, Katelyn Pegg, Anika Raffle, Gin Williams

Managing Editors

Abbie Karel, Disha Manayilakath, Amalia Tormala, Sophia Zhang

Online Editors-in-Chief

Sophia Dong, Kaitlyn GonzalezArceo

Social Media Manager

Dylan Berger

Staff Writers

Talia Boneh, Alice Sheffer

Business Manager

Lily Jeffrey

Multimedia Director

Ria Mirchandani

Table of Contents

Gin Williams

Adviser

Brian Wilson

Estelle Dufour, Zoe Ferring, Ella Hwang, Annie Kasanin, Sonya

Kuzmicheva, Luna Lim, Maia Lin, Fallon Porter, Silvia Rodriguez, Ellis Shyamji, Maria Uribe Estrada

Cover

Alice Sheffer

Poster

Talia Boneh

The C Magazine staff welcomes letters to the editors but reserve the right to edit all submissions for length, grammar, potential libel, invasion of privacy and obscenity. Send all letters to cmagazine.eics@gmail.com or to 50 Embarcadero Rd., Palo Alto, CA 94301.

Dylan Berger, Talia Boneh, Paul Brisson, Sophia Dong, Estelle Dufour, Maria Estrada Uribe, Zoe Ferring, Sasha Kapadia, Abigail Karel, Luna Lim, Fallon Porter, Anika Raffle, Alice Sheffer, Scott

Table of contents

Indigenous communities have long fought to protect their homelands while preserving their cultural roots

For thousands of years, Indigenous nations and communities across the United States have maintained a deep connection to their homelands, which serve as the foundation of their daily lives, art, food and cultural traditions. But what happens when that land is taken, scarred or denied to those who cherish it the most?

Once pristine forests and plains have faced damage from Western colonial greed and expansion, forcing many Native American communities off of their ancestral homelands and onto reservations that lack environmental stability and resources, separating them from their families and cultural traditions. As a result, traditional cultural beliefs and practices have been often actively discouraged, but the enduring bonds of

1500s. Frankie Gilmore, Sariah’s grandfather, is a veteran, artist and former Navajo language teacher and school administrator. He believes that using the name Diné holds a deeper meaning than labels imposed by outsiders.

“I was always taught to introduce myself, of who I am, as a Diné,” Frankie Gilmore said. “Diné meaning ‘the people,’ which is the word that we use instead of Navajo or whatever they want to call us. Look at the whole story of why we were called the Indian Nations — the United States government even has a law that says that we are to be called Indians instead of the Diné or Navajo.”

“We always try to strive for a balanced life, and that means taking care of the land, taking care of ourselves.”

Sariah Gilmore, 12

In the 1860s, the U.S. Army forcibly removed the Navajo people from their land by carrying out a scorchedearth campaign, burning their lands

forced exile endured by the Diné is a constant reminder of their struggle for the rights to their land.

“I tend to not like to say reservation,” Frankie Gilmore said. “I just don't like the idea that another group of people can take over another group of people. We call it colonialism.”

After being forced to leave the land which had sustained their people for thousands of years, the Navajo people’s return and reunification with their ancestral land in 1868 was critical in regaining connection to the places that hold significance and strength in their culture.

“One of the stories that really resonates with me is when [the Navajo] were released back to go back to the land,” Sariah Gilmore said. “Identifying the Four Sacred Mountains was really powerful, and that's where this prayer comes from. There's a prayer that was said to thank the land that came before and after them.”

name of Ralph Gilmore. When he went to that school, they said, ‘What's your name?’ and he gave them a Navajo name. They said, ‘You can't have that.’ They had a list of names alongside whoever was collecting the census of the Navajo people that were going to school, so he [the agent] just gave him a name, right there. So that's how we came up with the name Gilmore.”

Frankie Gilmore himself spent years of his childhood away from his family.

“I don’t like the idea that another group of people can take over another group of people. We call it colonialism.”

The Navajo people established themselves as the sovereign Navajo Nation through the Treaty of 1868, where they worked to preserve their way of life. Despite regaining their ancestral land, the connection formed by living on that land was at the risk of being destroyed. According to the National Museum of the American Indian, boarding schools, operated by the government, began forcibly taking Indigenous children from their families to attend schools where they were abused, forbidden from speaking their native languages and forced to assimilate into Western culture.

“My first day of school was at a government boarding school,” Frankie Gilmore said. “I grew up going to school in a place called Kayenta. It was a military style type of education where you got up at four in the morning, breakfast at five and school at six. I did that for six years. So if you look at my life from the time I was four years old, when I first went to the government boarding school, I was in the boarding school not living with my parents for six years.”

Frankie Gilmore, Navajo veteran and artist

“In the [Treaty of 1868] that was with the Navajos and the United States government, there's 13 articles within the treaty, and there is a part where it says, ‘We will train your children from here until the end of time,’” Frankie Gilmore said. “So they brought up all these boarding schools, and they started sending the younger

The story of being removed from Native culture and land impacted the childhoods of generations of Navajo.

During his time at the boarding school, Frankie Gilmore was placed in an environment with crowded, unfavorable conditions.

“At the time, there were almost 1,000 kids that were from kindergarten all the way to sixth grade,” Frankie Gilmore said. “You were all clumped together. … There was a lot of bullying going on, and a lot of gangs were there.”

Summertime became a much-needed respite for the nine months of the year Frankie Gilmore was away from home. Each summer, Gilmore returned to spend time with his parents where he found solace in connecting with the Navajo land.

“When I want to hear peace, I don't go to listen to the ocean,” Frankie Gilmore said. “My peace is up in the mountains where I can hear the animals. I can hear the flying people. I can hear the wind, the soft wind and the little fluttering of the trees. You can hear the trees talking and swaying back and forth. You see those kinds of things. It gives me peace.”

Frankie Gilmore learned the Diné language and traditions

at the birds and whatnot. There's a lot of training involved.”

Through his family, Frankie Gilmore learned of the mindset of the Navajo people when interacting with the land which is exemplified by the Navajo word “Hózhó.” Frankie Gilmore has passed that understanding down to his granddaughter Sariah.

“‘Hózhó’ means balance,” Sariah Gilmore said. “Everything has a connection. The moon and the sun are Hózhó. The different land aspects [are Hózhó]. Everything is just in balance. So we always try to strive for a balanced life, and that means taking care of the land, taking care of ourselves.”

The balance and beauty of Hózhó extends to all living things on planet Earth.

“Everything is connected to Mother Earth, and you can't live without Father Sky,” Frankie Gilmore said. “What the animals do helps the environment, what the feather people do helps the environment, what the plants do helps the environment. We are all of those things because how do we eat? Where does it come from? From the ground, and when we say the ground that's pretty sacred to us — when we say the ground that's Mother Earth. She provides for us. She provides so much for us, the minerals that we take in. And you know, the process of the ecosystem of Mother Earth is powerful, and you can't include that without Father Sky because he provides the air, the wind, the rain.”

lot of them, are still there,” Dade said. “My dad is the oldest of eight — most of his siblings are still there and we would go every summer for powwows and to visit.”

This upbringing has formed Dade’s perspective on living with the land.

“A big part of the cultural way of looking at the land is respect,” Dade said. “If you're going to use the land, then you treat it well. After people hunted, they would use every part of the animal. You didn’t discard. There was a respect for the cycle of life, and the land is another part of that.”

The idea of being on equal terms with the land is seen in other Native nations as well. Frankie Gilmore keeps Hózhó in mind, conserving nature’s beauty rather than exploiting it.

“My peace is up in the mountains, where I can hear the animals.”

“When you go to the mountain and someone is ill, you pick a plant that helps you get better,” Frankie Gilmore said. “But you never get the best plant. You never, even though it is the most beautiful flower up in the mountain, pick that flower. It's the one that has the offspring that bring in the most beauty so you don't want to grab that one; you'll take the next one, and then you offer something back, and you always say ‘Thank you for allowing me to take you.’”

Frankie Gilmore, Navajo veteran and artist

The boarding school system disrupted the cultural knowledge that passes down through generations. However, Sariah Gilmore has found that visiting the reservation helps her to stay in touch with Navajo culture.

“Even if you go back to the reservation, there are many Native children that don't know their culture fully, and they usually rely on elders [for cultural knowledge],” Sariah Gilmore said. “But then again, there's that traumatic experience that they have that they don't really share their culture anymore. So I personally don't know my own native language or a lot of aspects because of those boarding schools that came in place. Just going back and experiencing different things firsthand on the reservation really helps [me] connect with that.”

Similarly, Paly math teacher Alexander Dade, a member of the Hidatsa tribe, part of the Three Affiliated Tribes that reside on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota, learned more about Native culture through his family and a local tribe in Washington

This approach to using the land differs from the waste that runs rampant in mainstream American culture. Christopher Farina, a Paly Ethnic Studies teacher, attributes European settlers’ exploitation of ancestral lands to colonialist motives.

“The European conception of land is that it should be thought of as property that you can possess, that you can own and that you use,” Farina said. “It could turn into a view that's very extractive. It [land] becomes commercialized and feeds into a capitalist idea that we should treat this as a resource that we should be able to profit from as much as possible.”

This idea of viewing land as a commodity has carried over to modern-day society. Dade believes that this capitalist mindset is disrespectful towards the land from which Native nations such as the Hidatsa Nation come from.

“A lot of our [American] culture is centered around temporary possessions and consumption,” Dade said. “There's not a lot of thought about where all that stuff comes from and treating that with respect. Everything from consumerism to just the prominence of littering in America is something I personally take issue

of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which would transfer crude oil from North Dakota to Illinois, was announced. The potential desecration of cultural sites prompted multiple Native nations to advocate for the protection of their land.

“There were protests against this pipeline [Dakota Access Pipeline] that was supposed to be built under a lot of the lakes and rivers in North Dakota, even near my tribe,” Dade said.

The Standing Rock Sioux were among many tribes whose land the pipeline would run through, and they fought back and sued the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Eventually, construction of the pipeline was halted. However, when President Donald Trump came into office in Jan. 2017, he sped up the building process of the pipeline, which was completed in April 2017.

United States, and so there are a lot of social justice aspects that go into the art,” La Fetra said. “There are pieces that show the Indigenous customs, but it also has some social justice things built into it, as far as meaning goes.”

“The land is part of our life and the way that we all are. The land is considered sacred.”

Alexander Dade, member of the Hidatsa Tribe

“There's a lot of oil on a lot of reservation land,” Dade said. “That's something that people live with and in some ways coexist with. It does provide a lot of money for people, which is arguably beneficial, but you have to contrast that with the potential environmental damage.”

These pipelines lead to an increased risk of water, soil, animal and plant life contamination of Native land.

“The Keystone XL pipeline burst a few years ago,” Dade said. “That was the pipeline after which the Dakota Access Pipeline was modeled. The land is part of our life and the way that we all are. The land is considered sacred.”

Native resilience and activism against environmental harm form a crucial aspect of ensuring that ancestral land will be preserved for future generations. This pro test can also be expressed through art. AP Art History teacher Sue La Fetra leads her class through a unit fo cused on Indigenous art forms, with some of the artwork pushing back against and exposing the injustices faced by Native communities.

“The Indigenous people have endured a lot from the

The class curriculum explores the work of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes.

“The piece that we study in class is called ‘Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People)’,” La Fetra said. “The point of that piece is that from the white person's perspective, they understand that they've traded the land that belongs to the Indigenous people for trinkets that the white people have given them.”

Smith mixes mediums and blends contemporary art with facets of Indigenous culture to bring a new perspective on how Native history in viewed in the United States.

“This [‘Trade’] is a great piece that has a canoe, which is a traditional means of transportation for the Indigenous people, but then they incorporate these modern things that bring up issues that were unfair to them as well,” La Fetra said.

As Native communities have found ways to maintain their identities through hardships, their connection to ancestral lands has been vital in strengthening their ties to their cultures.

“Life never ends,” Frankie Gilmore said. “What you give your kids and your grandkids will be passed on. So how do you treat Mother Earth? How you treat Mother Earth is very, very important. How you treat Father

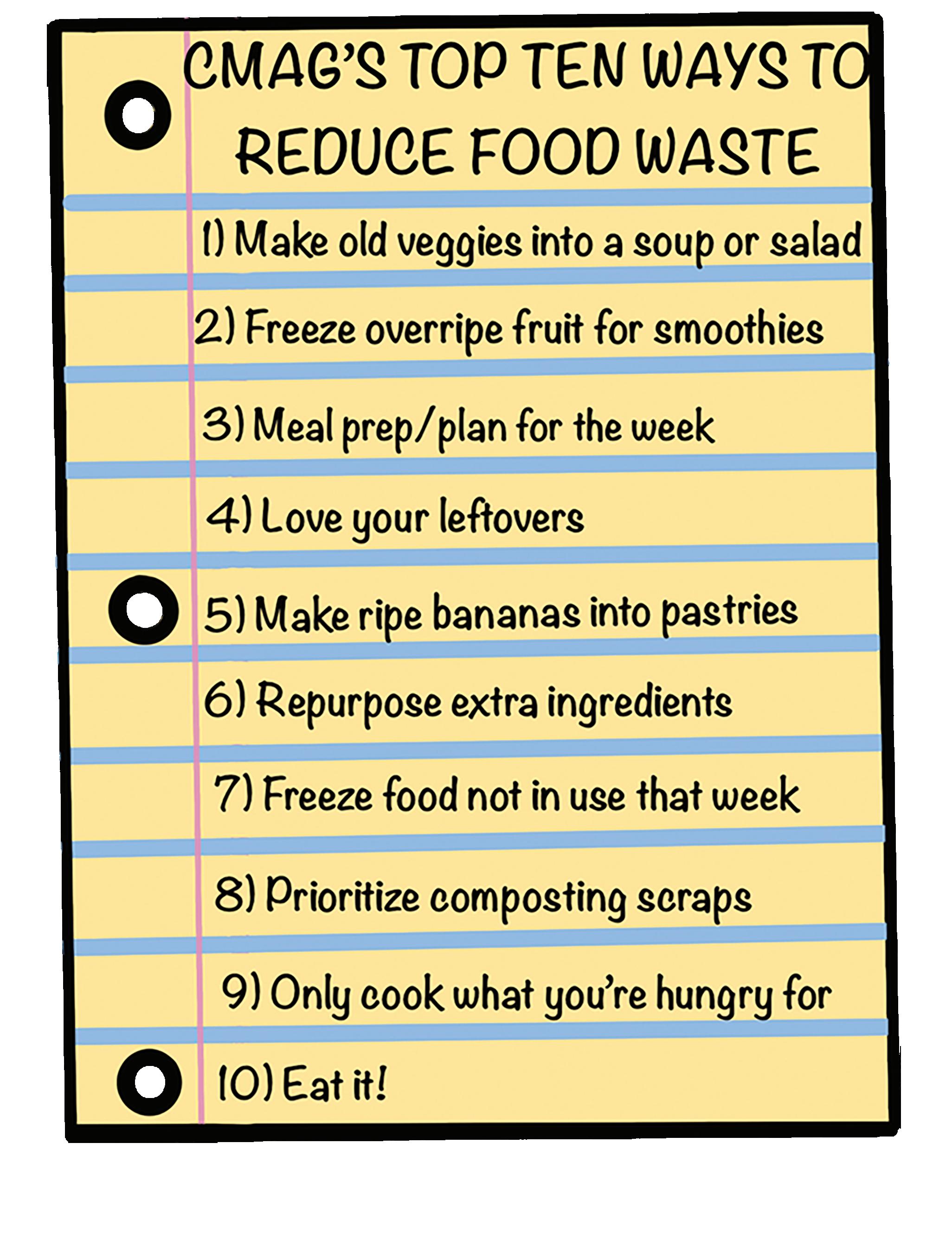

In a world where social media dictates trends and consumer actions, food trends fueled by influencers have emerged as a factor contributing to global environmental issues. Platforms such as TikTok and Instagram are popularizing content from extravagant mukbangs — directly translated to “eating shows” — to luxury grocery hauls. Although these videos are entertaining for millions of viewers, they can also contribute to a cycle of overconsumption and waste that leads to real-world problems.

One of the roots of overconsumption stems from social media turning food into a spectacle. When online creators purchase food with the intention of “binging” on massive quantities for views, it often leads

“There’s a mukbang culture going on right now where you just eat a ton of junk food, and it’s pretty unrealistic.”

Emma Yang, 12

Social media influencers promote food trends that drive overconsumption, but individuals can choose sustainably and lessen their impact

to ample food waste while simultaneously encouraging viewers to participate in similar actions.

Many social media users, including Palo Alto High School senior Emma Yang, have experienced videos that promote consumption culture firsthand.

“There’s a mukbang culture going on right now where you just eat a ton of junk food, and it’s pretty unrealistic,” Yang said “It definitely doesn’t make it enjoyable to watch. It’s also influencing a lot of people to purchase mass amounts of food that they’re not going to be able to finish in one sitting.”

cial media presents can lead influencers to promote certain products, even when the quality may be overstated.

“Eating locally grown, organic foods that are in season is the best way to reduce the environmental footprint of food consumption.”

Nicole Loomis, AP Environmental Science teacher

Due to the accessibility of social media, some influencers focus on making money rather than what is really healthy for their bodies and the environment.

“Using mass eating clickbait gets more views,” Yang said. “They’re making more money and could be influencing other content creators to slowly hop on the trend.”

The economic opportunities that so-

“There’s a big controversy going around right now with the supplement Bloom,” Yang said. “With their superfood supplement, we have a ton of young influencers — people in their mid-20s, people in their mid-30s — swearing by this product. But I’ve tried it, and it totally didn’t work for me.”

Senior Aria Shah believes that just as influencers may promote products like Bloom, trendy, upscale grocery stores such as Erewhon, which are also recommended by influencers, are key promoters in encouraging excessive waste.

“Right now there is a trend where people are buying a single strawberry for $19, and it’s definitely a scam,” Shah said. “Each is packaged in a plastic container, and it has definitely contributed to plastic waste.”

While some social media influencers may primarily be focused on economic gain, they also have the power to encourage positive change by guiding their audiences toward making more sustainable choices.

“I follow Nara Smith because I love how she makes everything from scratch,” Shah said. “It shows that you don’t need to buy all the processed food to make food that you enjoy at home.”

“Familieswilloftenspendan excessof$1,500peryearon foodthatisnevereaten.” BrianRoe,professoroffarmmanagementat TheOhioStateUniversity

“Families will often spend an excess of $1,500 per year on food that is never eaten while the production and discard of food that is not eaten generates substantial greenhouse gas emissions,” Roe said.

Roe believes that companies are also key to promoting sustainable purchases, as their choices can influence the amount and type of food customers have access to.

Choosing to take the environmentally friendly option of making food at home often means buying produce from grocery stores. Yet, economics teacher Grant Blackburn believes that grocery stores have a major effect on waste, both for their customers as well as for the environment as a whole.

“From a business perspective, grocery stores don’t care about food waste,” Blackburn said. “If anything, they benefit from it — they want you to buy as much as possible, throw it away and come right back to restock. But on a larger scale, food waste creates greenhouse gases and drives up demand, which raises food prices. That, in turn, hurts lower-income communities the most.”

“If [wasted food] gets into landfills, it releases methane when it breaks down, and that is a powerful greenhouse gas.”

Nicole Loomis, AP Environmental Science teacher

“Companies could avoid using buyone-get-one-free offers for perishable foods, which tend to increase the odds of food going uneaten, and influencers can point to hacks and tips that permit people to save money by better managing and preparing their food,” Roe said. Every product in the food supply — whether it’s a bag of chips, a piece of fruit or a rotisserie chicken — requires energy, water and labor resources to produce. The more waste there is, the higher the demand for these already limited resources. This exacerbates climate change, increases food insecurity and depletes essential natural resources.

AP Environmental Science teacher Nicole Loomis believes food waste is a common and damaging phenomenon.

According to Brian Roe, a professor of farm management at The Ohio State University, average food waste in a household can lead to large-scale negative impacts.

“If [wasted food] gets into landfills, it releases methane when it breaks down, and that is a powerful greenhouse gas,” Loomis said. “There are also the emissions associated with picking up food

Infographic provided by Brian Roe

waste and bringing it to the waste facility.”

Apart from viewers being influenced by social media and related sources, schools can also can be an important source of information to advocate for food sustainability.

“I’m a big advocate for schools to teach more life skills if that makes sense,” Yang said. “So knowing how to budget your groceries, knowing what to do with leftover food. I [had] never thought to check my cabinets for food that could expire soon to donate it to a food shelter or to a homeless shelter — places that are in dire need of food.”

There are many ways individuals can limit the amount of food that is wasted in their household, most of which are minor lifestyle changes.

“Shop your fridge first to ensure you

don’t buy excess goods,” Roe said. “Love your leftovers. Find [food] prep tips so you use up items in your fridge before they go bad. Learn to store produce items the right way so they have longer shelf lives.”

Although making specific changes can be challenging, there are a variety of ways people can tweak their actions to make a positive impact.

“We all need to eat, so eating locally grown, organic foods that are in season is the best way to reduce the environmental footprint of food consumption,” Loomis said. “From a climate change and water use perspective, eating less meat is also a good way to reduce the environmental footprint of food.”

Awareness can also motivate people to make more environmentally friendly choices.

“Tracking food waste at the municipal or home levels can stimulate people to reduce waste,” Roe said. “Certainly [awareness] can affect their decision making, but it might not necessarily help the food waste problem because you have to change their habits.”

Ultimately, the ripple effects of overconsumption extend far beyond a 10-second video. By recognizing the influence of social media and the benefits of making conscious choices, individuals can reduce waste and contribute to a more sustainable future.

“The way we perceive food affects how we consume it, which affects waste, which affects prices,” Blackburn said. “It’s all interconnected.”

Text,

design and art

by ZOE FERRING and ABIGAIL KAREL

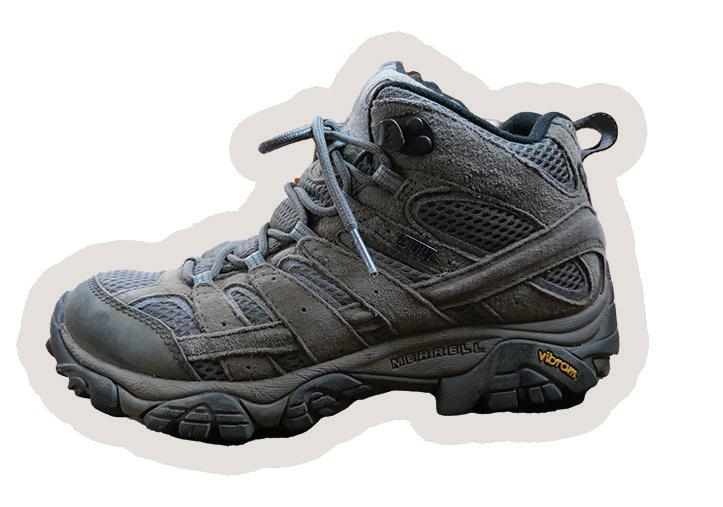

Outdoor athletes are battling

climate change to preserve their sports’ enviroments

For many athletes at Palo Alto High School, sports are not just about competition — they enable a connection to movement and nature itself. Whether skiing through fresh powder, surfing as the sun rises or embarking on a mountain biking trail, these activities are not purely physical. They provide a way to escape stress in everyday life, forming a sense of belonging and connection with the environment in a way that feels meaningful.

Junior Alessio Dorigo, who has been surfing since he was young, highly values outdoor hobbies.

“I think it’s super important to have a hobby in nature … the elements really just make an experience so much better,” Dorigo said.

For senior Tyler Kramer, these outdoor activities serve as a much-needed mental break.

Outdoor sports allow people to connect with nature, but they are also vulnerable to environmental changes. The environments that athletes depend on for their sport are transforming dramatically and the impacts are becoming harder to ignore. According to AP Environmental Science teacher Nicole Loomis, global warming has severe implications for polar regions.

“The effects of global warming are being seen the most in the Arctic where temperatures that would typically be below freezing are staying above freezing, resulting in the melting of land and sea ice and permafrost in the Tundra,” Loomis said.

These changes in the Arctic contribute to rising sea levels, which are already impacting coastlines and surf breaks. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, ocean temperatures are currently at their peak. This is directly affecting the reliability of surf conditions.

“Spending time working on rivers, surfing and hiking has given me a deeper appreciation for time spent in nature.”

Austin Davis, history teacher

“It definitely takes my mind off things,” Kramer said. “If I’m out surfing or skiing, I don’t really have time to think about all the other things that are stressing me, which is really, really nice.”

The outdoors offers similar respite for history teacher Austin Davis.

“When I go out to the Baylands, or when I go up into the Santa Cruz Mountains … I feel like I can slow down a little bit, and not think about all the stresses,” Davis said.

The rising temperatures make surf seasons more uncertain, with less predictable waves.

In addition to the unpredictable wave trends, rising sea levels are taking over beaches and wiping out surf breaks. To help combat these challenges, the Surfrider Foundation tries to maintain ocean health through three primary fronts: reducing plastic pollution, fighting water pollution and preserving coastal ecosystems.

Junior Nathan Lee, a co-founder of the Environmental Service Club at Paly, has experienced firsthand how these changes affect oceans and mountains.

“In terms of skiing or surfing, you can see shorter winters which means less skiing time, or we see rising sea levels that change the waves and the level,” Lee said.

These shorter winter seasons mean that ski resorts are now increasingly relying on man-made snow to extend their seasons. The Environmental Protection Agency has observed that the snowpack in the West has declined by 20% since 1955. Sophomore Melitta Pieper has noticed the impact of such changes.

“Some resorts use artificial snow, which isn’t ideal since skiing is connected to real snow, ultimately making me worried for the future of the sport,” Pieper said.

As with most sports that take place outdoors, cross-country runners have a keen connection with the environment, and as the seasons grow more unpredictable and the weather more volatile, they notice and experience the impacts of climate change in the very landscapes they love to race on firsthand.

As cross-country courses grow more vulnerable to weather conditions, athletes like junior Amaya Bharadwaj are also more aware of how much their sport depends on the environment’s well-being.

“When we were racing at Crystal Springs, which is known to be the hardest course … I almost fainted afterward; there was an

ambulance at the finish line because a lot of people got sick be cause of the heat,” Bharadwaj said.

While these issues may appear to be overwhelming, there is growing momentum among athletes to save the natural environment that they love. Pieper believes the position that athletes hold in influencing their audiences and the general public goes beyond just sports fans.

“Athletes have a big platform; therefore, by talking about it [the environment] on social media or interviews, they can spread awareness and set an example for others,” Pieper said.

This influence is not limited to the sports world; athletes are using their platforms to inspire environmental activism.

Organizations like Leave No Trace and Protect Our Winter (POW) are joining forces with athletes to promote environmental activism.

POW, founded by professional snowboarder Jeremy Jones, is focused on helping athletes take action on the issue of climate change. The organization advocates for policies that reduce carbon emissions, promote renewable energy and protect natural habitats from further destruction.

With this work, POW has brought together a team of athletes that includes Olympic skiers, international-level climbers and more who are using their stature to make a difference and initiate policy reforms. But beyond large-scale advocacy, change also happens through the small, everyday choices individuals make.

“I try to do small things in my day-to-day life to help with the issue, such as reducing waste and recycling,” Pieper said. “Hopefully, these small actions can play an overall bigger part.”

The outdoor sporting world is filled with people who are passionate about their sports and the world they are living in.

“The Environmental Service Club has worked with Grassroots Ecology and is planning on working with Save the Bay,” Lee said.

As the outdoor sports community fights to ensure there is a future for the planet, the next generation of competition stars will be remembered not just for what they can do on the pitch or in the mountains but for what they can do to help preserve the environment for future competition.

These athletes are leading the charge toward a greener future — one in which the connection between sports and the environment becomes more personal than ever before. For them, the outdoors is vital for their passion and appreciation for nature.

“Spending time working on rivers, surfing and hiking has given me a deeper appreciation for time spent in nature,” Davis said. “There is a sense of peace and calm that comes from being in an environment with no cell or internet service. I find that I can better tune in to my environment and the people that I’m with.”

A sense of impending environmental collapse fuels a unique and pervasive mental health challenge

In 2050, it is estimated that there will be more plastic than fish in the sea (by weight). By that same year, global temperatures are projected to increase by 1.5 degrees Celsius, increasing the frequency and magnitude of extreme weather events. In just 25 years, around 35% of existing wildlife could become extinct.

Hearing statistics like this is relatively common; it has been widely publicized that Earth’s climate is heading downhill with no foreseeable end. Climate scientists, researchers and news outlets all agree — climate change is real, and its consequences are imminent. Much of the media the public consumes paints a picture of no return; dread and anxiety about the planet’s future are more prevalent than ever.

“IT'S ABOUT WORKING TOGETHER. ... IT'S ABOUT COMING TOGETHER AND HAVING AN IMPACT.”

As biologist and Stanford professor Deborah Gordon highlights, there is no longer a threshold of climate change that is waiting to be passed.

“The climate will never return to the conditions of 50 or even 20 years ago,” Gordon said.

who use social media, around 69% of Generation Z reported they “felt anxious about the future” after seeing content addressing climate change. This is roughly 10% higher than Millennial users and around 20% higher than Gen X and Baby Boomers. Elsa Lagerblad, a junior and Head Chair of the Youth Climate Advisory Board, explains the root of this phenomenon.

“[Climate anxiety is] definitely deeply connected to the rise of social media,” Lagerblad said. “People get really scared when they hear that their planet is burning. So along with the rise of social media, we’ve seen a rise in people consuming content that is … so bad for their sense of trust and faith in the future.”

In general, climate anxiety has seen a steady upward climb over the last decade. A 2021 survey by The Lancet demonstrates that nearly 60% of respondents aged 16 to 25 reported feeling “extremely worried” about the current state of climate change.

For adolescents who spend much of their time on social media, an apocalyptic picture often takes shape, causing feelings of anxiety and dread. This phe-

Dread is just one of the many symptoms brought on by climate anxiety. Director of Education in the Division of Geriatric Psychiatry at McLean Hospital Stephanie Collier stresses that climate anxiety can manifest in a range of ways.

“Some people feel anger,” Collier said. “Some people feel guilt, shame or anxiety. Of course, it can be physical. It can be thoughts that are racing and don’t let people sleep.”

Despite its impacts on the body and the psyche, Collier highlights one key facet.

“Climate anxiety is not a mental illness and it doesn’t require treatment, but it is distress, and it’s related to something that’s real as well,” Collier said. “Generally, with anxiety disorders, anxiety sometimes can overwhelm a person so that they feel like they can’t take action.”

Large, intimidating statistics can be one trigger of climate anxiety that causes people to freeze according to climate psychologist

climate anxiety is overall hopelessness.

“The second effect is that it [climate anxiety] can be very depressing,” Davenport said. “It can make you anxious.”

According to Collier, teenagers and women are the groups most impacted by climate anxiety, though all demographics show augmented numbers of people reportedly anxious about the future of the planet.

While it may appear that the Earth’s future is dire, Palo Alto Student Climate Coalition Projects Lead Brendan Giang believes that human impact on the environment is not irreversible.

“We have made a lot of progress right now, [but] is it enough?” Giang said. “We’re getting there, and we have made progress. We have realized that this [climate change] is an issue, and we have done things right.”

Laberglad agrees, emphasizing the contrast between progress and harmful actions.

“There are a lot of big strides being made in the realm of climate advocacy and climate action,” Lagerblad said. “Just because there may be some unfortunate things going on doesn’t mean that we aren’t still making progress.”

Just over one decade ago, Davenport realized how serious of an issue climate change was, and she decided to do something about it. Until that point, Davenport already had ample experience using psychotherapy — an emotion and behavior-based treatment plan often used to address mental illnesses — to treat patients. When she began to address climate anxiety with patients, it was a seamless transition.

“I looked at the things we’re already trained in, like working with grief and complex emotions, breaking through denial, supporting lifestyle change and facilitating conversations that can be difficult,” Davenport said. “I realized all of that is really applicable ment would be to take action so that the person feels like they’re

social media. There are benefits to having access to media, as junior Chiara Martin explains.

“[Posting on social media] spreads consciousness … so others might feel morally obligated to do environmentally conscious activities,” Martin said.

While some may assume that social media purely depicts the negative side of the climate, many Paly students are exposed to positive media. A new genre of social media known as ‘hopecore’ is growing in popularity.

Hopecore is defined as a genre of videos that invokes a feeling of hope, glee and positivity in its viewers. According to a 2025 article from Saas Magazine, hopecore is a positive mindset that helps viewers navigate challenges and reduce the stress associated with it.

Junior Nalani Walsh believes that hopecore videos are created from a less attention-seeking perspective than other inspirational videos, which gives them a more impactful and personalized feel. Walsh also highlights that hopecore videos can inspire hope and faith in the general population, which can ultimately lead people to take action.

Exposure to positive movements such as hopecore videos can propel communities to implement the same procedures. As English zoologist and activist Jane Goodall writes in her book, “The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times,” “Hope is contagious. Your actions will inspire others.”

As Goodall explains, change begins with small actions that get repeated by increasing amounts of people. This is why Martin believes raising awareness is so vital — it broadcasts the message over a larger expanse.

“If everyone is urging for change, change will happen,” Martin said. “We just need to get everyone on board.”

In accordance with Martin, Gordon alludes to the importance of action.

“It’s really important to understand that everything that we do helps and that there’s never a moment where we should just give up and say it’s too late,” Gordon said.

“Hopecore videos inspire faith in humanity and show teens who easily get lost in the negativity and comparative aspects of social media that reality has more to offer than you may think,” Walsh says.

According to junior Cailey Quita, these videos also act as a tool to motivate viewers.

“[Hopecore videos] shift the focus from fear to action — instead of feeling overwhelmed, viewers can see real world examples of progress and advancements,” Quita said. “They provide a hopefulness for the future, showing that solutions exist and that individual and group actions do have results to empower people to act.”

11

According to the New York Times, if every American cut 10% of their car usage a year, it would prevent roughly 110 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from entering our atmosphere. This is just one example of climate activism possible in many people’s day-to-day lives. According to Lagerblad, making these daily shifts can wind up having a bigger, positive impact on the environment than some would presume.

“I’ve become a lot more conscious about how I get around the city,” Lagerblad said. “I’ve opted not to drive, even when it is somewhat of an inconvenience, and instead use public transit because we have such awesome electric public transit in the Bay Area. It would be such a waste to not take advantage of it.”

Of all the ways to reduce the impact of climate change and therefore counter climate anxiety, there is a common denominator — actually taking action. Giang elaborates on other things that can be changed about our everyday routines.

“Let’s not buy from these fast fashion brands,” Giang said. “[Let’s] re-wear the clothes that [we] have more often and stop to think before [we] buy plastic water bottles … or choose organic produce.”

Giang also emphasizes the power and importance of community when making a change.

“It’s about working together,” Giang said. “It’s about coming together and having an impact. We don’t have to leave climate change up to the politicians at the global conventions and … fusion scientists … if every person just does their small part.”

As climate anxiety becomes more and more prevalent, students like Martin find it imperative to take action and attempt to conquer this anxiety with tangible effects.

“We can’t predict the future,” Martin said. “All you can think about is what you’re doing now.”

Text and design by ESTELLE DUFOUR, MAIA LIN and AMALIA TORMALA • Art by SASHA KAPADIA

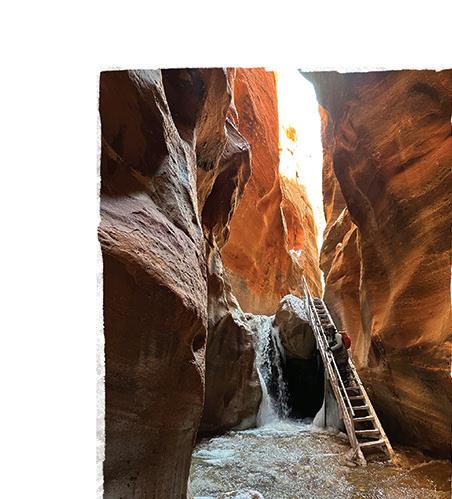

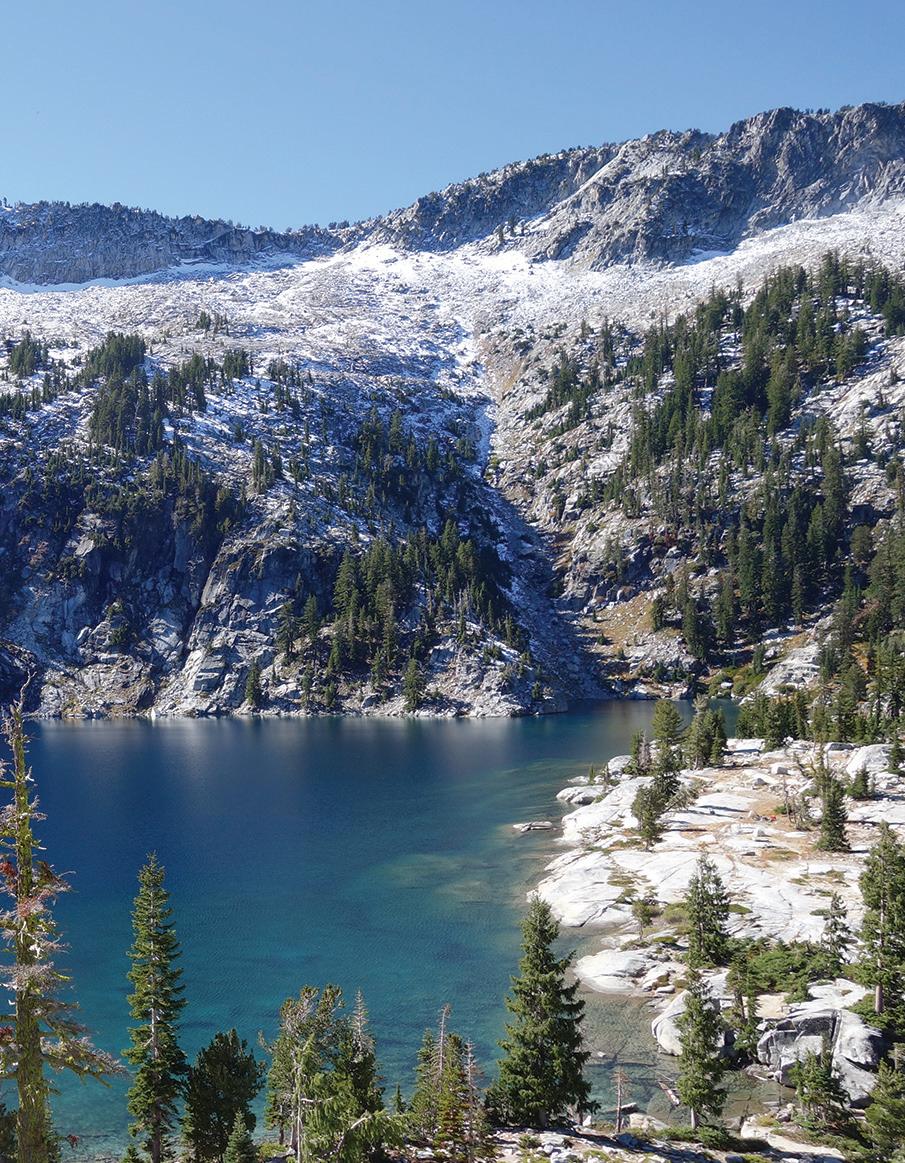

National parks are shutting down. This is not a post-apocalyptic statement, nor is it my prediction for the future; it is the United States’ current state of affairs.

Since President Donald Trump took office on Jan. 20, his slew of executive orders has disrupted universities, social services and federal employees across the nation. From putting a temporary pause on foreign aid spending to halting many divisions of government work altogether, the daily headlines stating “Trump shuts down” followed by the name of an agency now seem increasingly common.

In a Feb. 26 memo written by Direc tor of the White House’s Office of Man agement and Budget Russell Vought and acting Director of the Office of Personnel Management Charles Ezell, it is stated that the government is currently “costly, ineffi cient, and deeply in debt.” The memo re affirms Trump’s statement that all agency heads must reduce staff sizes and develop reorganization plans before March 13 and then goes on to disparage how the United States is spending its money.

“Tax dollars are being siphoned off to fund unproductive and unnecessary pro grams that benefit radical interest groups while hurting hard-working American cit izens,” the memo said.

Given that national parks are a fed erally-funded system, they too were hit

with the dilemma of cutting staffers to cut government spending. Due to a March 20 court order, the 1,000 staffers whose jobs were terminated are to be reinstated into their original roles.

Despite the court’s decision, I still pose a question to Trump and his administration: Is attempting to remove something so integral to the American people really helping us?

The answer, as I see it so clearly in my eyes, is no — placing park rangers and staffers on leave to promote government “efficiency” has a distinct negative effect on the nation’s citizenry by removing hundreds of

dent, considers the feelings and well-being of his people?

Excluding my own disappointment, Trump’s recent policies have caused an entirely new feeling to resurface: a dormant nostalgia that I’ve been harboring since a very young age.

As my father often reminds me, the reason he and my mother chose to raise me in California was because of the immediate access to natural beauty we Californians have. Now, that is not to say that my fiveyear-old self understood or appreciated the natural beauty so accessible to me in the Bay Area, but after years and years of regu-

fondness for spending time in nature.

Windy Hill Open Space Preserve, Foothills Nature Preserve, Henry Cowell State Park — I’ve just about hiked them all.

When I later conquered Yosemite National Park as an adolescent, I felt as though I was on top of the world. Upon exiting the Wawona Tunnel, I was greeted with the staggering El Capitan on my left, Half Dome on my right and a long, gushing waterfall off in the distance. Not only were these mountains the most beautiful natural structures I’d ever laid my eyes upon, but Yosemite’s winding rivers, dense greenery and rocky hikes were unparalleled by any local state park I’d ever set foot in. My father and I embraced this extraordinary trip, a culmination of our mutual love

With this freeze, park employees, who are regularly entrusted with making decisions and purchases for their respective national parks, are no longer able to spend their money on water, electricity or repairs to benefit their places of work. Without the ability to pay for the well-being of national parks, I see national parks’ futures growing dimmer and dimmer by the day.

However, this is not the first time government shutdowns have impacted national parks and their employees: From December 2018 to January 2019, national parks were completely unfunded by the government. During this bout, just over 3,000 “essential” employees retained their roles and were responsible for managing millions of acres of national parks. Based on data from

parks and their neighboring areas.

Today, during this stretch of indefinite shutdowns, when the possibility of reaching a permanent compromise in the near future seems marginal, it is crucial that we do what we can to preserve national parks. Access to nature can dramatically reduce levels of stress and anxiety, thus improving mental health, according to “Nurtured by Nature,” a study by the American Psychological Association. For me and so many others, spending time in nature is an escape. As the United States continues to become even more city-oriented and industrialized, getting a break from the constant commotion and immersing oneself in nature is an incredibly rewarding experience.

To their employees, to our many citizens

Order Now: Visit StickySticker.shop or email hellostickystickershop@gmail.com

GardeninG offers a fulfillinG and peaceful experience that nurtures a connection to nature and a sense of togetherness

There’s a sense of satisfaction and responsibility that comes with watching a tiny seed grow into something bright and full of life, and the rewards go beyond just personal benefits.

Palo Alto, known for its green look, is home to many diverse gardening communities containing corridors — shared spaces for growing plants — and organizations contributing to its rich biodiversity and a strong sense of community.

Primrose Way Pollinator Garden Group is one of many Palo Alto gardening communities. The group gathers on the weekends and volunteers at the eight different pollinator gar-

the space.

“For Earth Day, for example, we harvested some buckwheats from the corridor, but usually, it’s mostly just keeping the weeds down,” Leung said.

The gardens in Palo Alto offer more than just a community building experience; they play an essential role in fostering environmental education. Through their focus on local plant species and the broader ecosystem, these spaces provide visitors with the opportunity to deepen their understanding of the region’s natural diversity.

“They [the gardens] help the community learn about the species that live here and how diverse California is,” Leung said.

the luxury of a large backyard to engage in gardening and contribute to preserving local biodiversity.

These gardens not only benefit the Palo Alto community, but also the overall health of the environment by fostering important pollinators like bees and butterflies, which are key in sustaining the overall local biodiversity.

Rinconada Garden Liaison Annie Carl believes that gardening in the community provides many benefits.

“Community gardening provides a range of ecological benefits, but without a doubt, the most significant is its positive impact on biodiversity,” Carl said. “By cultivating a variety of native plants and creating habitats for local wildlife, community gardens help preserve the natural diversity that is crucial to the health of our ecosystems.”

While not currently listed as endangered, the monarch butterfly population in California is facing a severe decline and is considered a species of greatest conservation need. These small gardens provide habitat for many monarch butterflies, with the Rinconada gardens having dedicated monarch butterfly sections, containing milkweed, a crucial plant for monarch butterfly caterpillars.

While these gardens may not have as large an impact as larger ecosystems like mangrove forests or jungles, they contribute significantly to environmental preservation.

“It [a garden] allows for an increase in biodiversity and creates a habitat for a lot of native species,” Leung said. “When we lose native species, we can have whole ecosystems collapse, and this helps prevent

However, gardening is a hobby that requires space, which poses a challenge for some. To address this, Palo Alto offers com

Beyond the ecological benefits, community gardens also play a key role in supporting mental well-being. Gardening is a calming, peaceful activity that helps reduce stress and improve mental health. The time spent tending to plants fosters a connection to nature, offering a mental escape and relaxation. A 2023 study by the Mayo Clinic shows that gardening can lighten mood and lower anxiety.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many utilized gardening as a way to acquire a sense of community, helping relieve the isolation they felt. Gardening provided a safe space for people to unite in an outdoor environment, away from the many limitations that COVID caused.

“During COVID, people took advantage of gardening, and the community garden was the only activity allowed outdoors,” Carl said. “This was such a great mental health benefit.”

While gardening became more popular during the pandemic, it has driven many to continue what they

pandemic keep up with this hobby even today.

Sophie, a Rinconada Com munity Garden user who asked to remain anonymous, watched the influx of people in the Rinconada Community Garden during the pandemic and notes how its presence continues to benefit many to this day.

“Even now with the pandemic over, people are still out here, and I think it really helps senior citizens,” Sophie said.

has especially gained popu larity among the older gen erations, pro viding a good creative outlet.

nior citizens] don’t have a whole lot of stuff to do, but you should see some of their gar dens — they’re fabulous,” Sophie said.

for anyone, as the gardening community welcomes all ages.

elementary schools’ curriculum for many years, with many elementary schools imple menting classroom gardens on their cam puses. Amy Sheward, principal of Lucille M. Nixon Elementary School, shares the inclusion of gardens in the school envi ronment.

the garden] and do some lessons,” Sheward said. “For instance, sec ond graders usually do a plant unit so that ties in really nicely.”

to many kids through parents or

As plastic pollution increasingly affects the public’s daily lives, taking action, no matter how big or small, has never been more important

Sipping Boba Guys, shopping for fish at Whole Foods or ordering a meal at the Stanford dining hall may all seem harmless, but they all involve the consumption of microscopic pieces of plastic. Recent reports by PlasticList, a team of environmental advocates and experts, revealed dangerous levels of microplastics in food from local places in the Bay Area. While their prevalence is only becoming better understood, microplastics’ impacts on human health and the planet are just beginning to be uncovered.

“We are full of microplastics,” Deng said. “What effect does that have? Who knows? We have longitudinal studies happening right now, but what are the results? We don’t know yet.”

“The problem [with microplastics] isn’t the size — it’s the fact that they take hundreds to thousands of years to decompose.”

While the size of the plastic is a concern for human health, other factors, including chemical composition and longevity, cause greater harm to ecosystems and food chains. Paly Ocean Awareness Club Co-President and sophomore Caroline Lee emphasizes the lasting impact microplastics have on ocean life.

Caroline Lee, Ocean Awareness Club co-president

Today, microplastics can be found everywhere: in food, oceans, forests, animals and even bodies and cells. Palo Alto High School’s marine biology teacher Margaret Deng highlights this.

“Turtles, fish, anything that you can catch — they [researchers] have done studies on them and asked how many of them have plastic in their stomachs [and] basically all of them do,” Deng said. “Even marine birds such as seagulls will eat plastics and things like that. Plastics are everywhere.”

Although research on microplastics is still new, scientists are beginning to predict and hypothesize about possible health impacts, such as endocrine disruption, inflammation and chronic illnesses. However, the long-term impacts of ingesting microplastics are still largely unknown.

“The problem [with microplastics] isn’t the size — it’s the fact that they take hundreds to thousands of years to decompose, and until then, they’re just floating around in our ocean, which is harming marine animals that consume them,” Lee said.

Marine animals’ health is not the only one at risk here, and the consequences of microplastics are far reaching.

but they also absorb and carry harmful chemicals.

“One problem with plastics in general is that they can act as little sponges for harmful substances and chemicals such as metals, pesticides [and] medicine that have made their way into waterways as runoff or via wastewater treatment systems,” Schworetezky said. “Plastics are also made of a large number of chemical compounds that can leach into the environment or, in the case of something like a plastic bottle, into the container and whatever it is holding.”

“We have federal and state waste management laws that require proper disposal of plastic waste, so it is important to hold up and enforce those laws.”

Nicole

Loomis,

AP Environmental Science teacher

According to Henry M. Gunn High School AP Environmental Science teacher Navneet Schworetzky, microplastics are not only extremely persistent in local ecosystems,

For Bay Area residents, their impact is becoming increasingly tangible. According to the Dec. 2024 PlasticList report, Boba Guys was found to have some of the highest levels of microplastics in their products out of more than 300 food products in the Bay Area. Since then, the company has taken measures to reduce its plastic use and has switched to Bisphenol A-free receipt paper and packaging for its brown sugar. For some students, learning about the prevalence of microplastics in the area and the Earth has led them to reevaluate when and how they interact with plastic in their daily routines.

“I feel like it’s hard to avoid places like

Eco-friendly! Farm fresh! Sustainable! Organic! Green! Bio!

These slogans are rampant throughout social media, online platforms and physical packages as companies attempt to brand themselves as supportive of environmental efforts. Most of these slogans are merely for clout and are often untrue, used for marketing or profit.

greenwash can be accused of doing so.

“Greenwashing puts a bad name on companies that are truly environmentally friendly,” Nance said. “It promotes businesses to use this practice to keep prices cheap while gaining customers who usually buy sustainably sourced goods.”

Known as greenwashing, this marketing tactic is becoming an increasingly prevalent issue. Brands try to appeal to their target audience by labeling themselves as more sustainable and environmentally friendly.

According to Robert Little, a Sustainability Strategy Lead at Google, greenwashing is a nebulous term with no compact definition and many complex layers.

“It [greenwashing] can be really intentional, like saying that a product or service is made from 100% recycled content, and it’s just flat-out false,” Little said. “The spirit of greenwashing is trying to take advantage of a consumer’s desire to have a lower [environmental] impact … and using that as a competitive advantage when you’re selling a product.”

A company’s competitive edge via greenwashing stems from the increased awareness of the climate crisis and how everyday consumers can mitigate climate change by purchasing sustainable products. When it comes to the climate crisis, Aaron Nance, Palo Alto High School senior and member of Palo Alto’s Youth Climate Advisory Board, thinks that companies take advantage of a consumer’s dogooder mentality.

Even outside of the corporate world, many younger citizens feel the impact of greenwashing. Eco Club Vice President and sophomore Avroh Shah believes some misconceptions are associated with greenwashing, and these biases could potentially harm progress in the fight against the underhanded tactic.

“One common misconception about greenwashing is that it is limited to the fashion industry, which is simply not true,” Shah said. “Greenwashing is very prevalent with industries across the board, ranging from aviation to banking, especially as consumers increasingly seek environmentally-conscious habits.”

“The spirit of greenwashing is trying to take advantage of a consumer’s desire to have a lower [environmental] impact … and using that as a competitive advantage when you're selling a product.”

“This is happening because companies notice people are starting to care for the environment more,” Nance said. “So, they start greenwashing to gain customers who have this care for sustainable practices.”

Additionally, in many industries, companies that greenwash also have adverse effects on companies that are genuinely environmentally friendly. In the worst cases, companies that don’t

Even if a consumer is not consciously picking a product based on its ecological footprint, today’s increased awareness of the climate crisis will inevitably impact consumers. Google

Sustainability Marketing Manager Logan Chadde shares the belief that consumers may consciously choose to pick an ecofriendly product over an alternative if they believe they are doing good.

“If deciding between otherwise similar products, [a consumer] will choose the one that is perceived to be more sustainable,” Chadde said. “It’s seen as an easy way to ‘vote with your wallet’ or make an impact.”

Since many companies typically only focus on increasing their profit margins, there are not many incentives to slow the practice of greenwashing. Audrey Sullivan, Paly senior and president of the Business and Finance Club, suggests that the concept of greenwashing is more complex than it initially appears, especially from an economic perspective.

“[Greenwashing] is essentially a negative externality that isn’t accounted for by business costs,” Sullivan said. “Firms have no incentive to do anything to offset the impact they have on the environment. The only potential incentive lies in consumer demand

NS TO ASK YOURSELF:

Is the brand making sustainability your responsibility or theirs?

Are their environmental claims vague, generic or non-specific? How much evidence do they provide to back up their claims? Do they give money to causes that align with your values?

5. Have they been accused of greenwashing previously?

6. Is it easy to find and access relevant information?

7. How sustainable is their supply chain?

8. How do they transport goods?

9. Do they use clean energy?

10. Long term goals?

product, the consumer will have to complete many extra steps.

“[Companies] claim that you can recycle [products],” Little said. “Of course, that’s true, but it has to be in a specialty program; it’s not in your curbside collection bin. Also, a thing that’s less than two inches is going to fall through the grates at a recycling facility. So, it is recyclable, but not in the way that consumer thinks about it.”

who have this care.

Similar to recyclable packaging, there are other ways to use more savory language to incentivize consumers to purchase a product.

“Promising to plant trees is another one [tactic] to be a little wary of,” Chadde said. “It’s not just the planting that’s important — you also need to ensure the tree stays alive and healthy for many years.”

“Environmental Product Energy Labeling, or Energy Label, is a very easy-to-interpret labeling system,” Little said. “It’s backed by the EU as well; it’s like a government label. I wish everybody had to have this [grade], and everybody was on the same scale. With this, as a consumer, I don’t have to do a ton of research to figure out if a product is good enough.”

In addition to supporting initiatives like labeling, Little believes governments have an important role to play in driving widespread change. This can be achieved by implementing policies that promote sustainability and setting clear standards.

“Governments can subsidize programs that encourage the reduction of waste and sustainable practices all along the supply chain, pass legislation that enforces compliance with environmental goals and educate the public about environmental goals,” Little

said.

Since the general public lacks insight into marketing decisions and business strategies, University of Chicago PhD student RJ Yang points out that a lack of awareness leads to poor consumer decisions when it comes to finding the most eco-friendly products.

“All consumers in today’s society who are buying stuff from these big companies are outsiders,” Yang said. “They have no idea what’s actually going on inside, or no control or any kind of way to even see what’s actually happening under the hood.”

In addition, though it is the brand’s responsibility to create honest marketing, many companies will sidestep ethical concerns of truthful messaging to promote business. Thus, as expected, the purchasing of less eco-friendly products in place of truly environmentally friendly ones can have an adverse effect on both the economy and ecosystems around the world.

“Greenwashing makes people feel good that what they are buying is helpful … but if a company’s practices are actually harmful to the environment, then it can cause long-term damage,” Chadde said. “Wasteful companies will boast about using recycled materials or supporting environmental and climate nonprofits, making it hard to differentiate between eco-conscious companies trying to make a name for themselves and corporations that do a lot more harm than good.”

Because many consumers care about the environment, they will purchase greenwashed products, and the cycle continues, spurring many companies to continue greenwashing. Thus, companies that greenwash are profiting off of consumers and being rewarded for false branding.

“You might be putting money into the pockets of owners of companies who don’t care about the environment,” Yang said. “You’re just rewarding companies that are more willing to lie.”

However, the Internet is a powerful tool in the fight against greenwashing, and it plays a crucial role in exposing this tactic.

“When a business is exposed for something on the internet, it is nearly impossible to sweep it under the rug,” Nance said. “Therefore, almost anyone who searches can find the information that they want, which is, in this case, if a brand is greenwashing or not.”

While governments should play a role in mitigating misleading environmental marketing, Chase comments that companies have an equally important responsibility,

“Companies should be transparent, avoid using misleading claims, set realistic goals and track progress on achieving those goals,” Chadde said.

Though it can be challenging to navigate the rabbit hole of what is sustainable and what is not, there are many simple actions consumers can take to reduce accidental greenwashing, such as briefly looking over a list of misleading labels.

“Promising to plant trees is one [tactic] to be a little wary of. It’s not just the planting that’s important — you need to ensure the tree stays alive and healthy for many years. ”

Logan Chadde, Sustainability Marketing Manager, Google

“It can be hard to figure all this out in a grocery store aisle or online product page, so you can always just focus on the brands you spend the most money on or buy most often,” Chadde said. “Perfectionism isn’t needed. Do what you can, especially for the most impactful purchases.”

Cap made of 100% recyclable materials

Label 30% smaller than average water bottle

Made with 25% less plastic than the average half-liter bottle

Flexible and easy to crush for recycling

COMMON LABELS:

Text and design by SOPHIA DONG and ALICE SHEFFER • Art and photos by SOPHIA DONG WATER EXAMPLE:

CERTIFIED MI

Katsura Garden 1825 Post St, San Francisco

C MAGAZINE VISITS LOCAL PLANT NURSERIES BRINGING NATURE TO THE BAY AREA

“Plants and flowers are a timeless gesture. There’s something so romantic about how ephemeral they are.”

Lauren Brunsvik, florist at Her Urban Herbs

Her Urban Herbs 629A Haight St, San Francisco

206 Filmore St, San Francisco

“Plant shops help create a space for people interested in nature, especially for those without access to nature near their homes.”

Jean Marx, owner of Cove Nursery

Anthropologie 180 El Camino Real, Palo Alto

This issue’s featured artist, Paly senior Leo Terman, connects to nature and his community through the art of flower arranging

In the summer heat, the air is thick with the scent of dahlias and zinnias. Wading through knee-high bursts of color on the Stanford Educational Farm, Palo Alto High School senior Leo Terman gathers handfuls of blossoms, each flower the product of weeks of dedication and consistency.

While others may form a connection to nature by spending time outdoors through camping, journaling or outdoor sports, Terman has found another path — flower arranging.

“There are many ways to [connect with nature], like hiking, and I love to hike too,” Terman said. “But when you’re actually taking care of something and cultivating it, it’s something different — it’s a little bit more intimate.”

Terman first discovered flower arranging in the summer before his junior year, when he quickly became enamored with the activity. It allowed him to interact with his surroundings in a way that helped both the environment and the local community.

“I worked at the Stock Farm at Stanford, where I took care of dahlias, zinnias and other flowers,” Terman said. “I’m not an

ing to learn from the people there.”

Like many students, Terman has experimented with other art forms in the past, but he felt a much closer connection to nature-based art than his previous hobbies.

“I did a little bit of art in middle school, and I like to produce music; I played the piano for eight years,” Terman said. “But in terms of art [in general], I mainly like using nature.”

Along with taking care of flowers, Terman also enjoys flower arranging, which he believes has the power to convey deeper meanings.

“There’s a lot of different ways you can arrange them; they can be more dramatic, or they can be simpler and decorative,” Terman said. “They can definitely reflect how you’re feeling.”

Beyond growing and arranging the flowers, Terman has often delivered them to various members of the Palo Alto community.

“I go to senior centers, and I can bring flowers to people that will improve their lives,” Terman said.

This small act of kindness has proven to be extremely meaningful and symbolic. One interaction Terman had while gifting a flower arrangement particularly resonated with him and made him realize the impact that flowers could have.

“I [delivered flowers] to one of my neighbors in Palo Alto,” Terman said. “She had a neurodivergent kid, and when I brought the flowers over, they were both really happy. It seemed to brighten their day. It was really rewarding to see people enjoying [the flowers].”

Beyond the personal satisfaction of bringing joy to others, Terman advocates for wider student participation in flower arranging through this natural connection.

“People get interested in [the flowers] because they’re very pretty,” Terman said. “It’s a lot more enticing than weeding at Arastradero preserve or a service thing. It’s a small way for people to get involved with [the environment].”

Besides being a simple and beautiful gift, flower arranging helps the farm conduct research and can even result in healthier flowers.

“When I sell the flowers over the summer, they help the

farm raise money for slug bait and fertilizer,” Terman said. “When you’re cutting the flowers, you’re actually helping them.”

While cutting flowers may seem counterproductive to their well-being, it can actually help them grow through a practice called deadheading.

“Deadheading is taking the flowers that have already opened and [are] starting to wilt and cutting them off from the stems so the stems will start branching out and make new flowers,” Terman said. “Making new flowers gets rid of that energy.”

Another aspect of growing flowers Terman discovered was the mutations that they can sometimes express. By approaching them from a scientific point of view, he has been able to understand more about nature and his local environment.

“Another interesting [part] is something called wolf petals,” Ter man said. “White dahlias aren’t actual ly white, they’re ivory. You can only get a pure white petal if small RNA is silencing the pigment pathway. There are so many different mutations in the flowers, and they all look very interesting.”

they’re the freshest.”

Terman finds special meaning in growing the flowers himself, which connects him with every step of the process.

In addition to their natural beauty and scientific interest, Terman appreciates the freshness and authenticity that comes with homegrown or locally-sourced flowers.

“It’s always better quality when you get them straight out of the field because the ones that you buy in the store are driven there,” Terman said. “Buying from local businesses is always better, but when you’re actually picking the flowers, that’s when

“It’s really nice to see the product of the work that you put in: weeding, taking care of the flowers, watering them,” Terman said. “You’re not just getting them from a store — it’s something that you actually grow. It makes it more personal.”

During the summer, Ter man goes to the farm early and spends the morning sharing his passion with the community.

“I [would] go early in the morning, maybe 7 a.m., and sometimes with my siblings,” Terman said. “We [would] go to the field and pick all the flowers. Then we loaded them up into buckets, put them in the back of my car and posted them on neighborhood lists.”

Taking care of flowers, arranging them and giving them to others has shaped Terman’s high school experience. He looks back on his time with the flowers with fondness.

“Flowers will always be something that I would look back on and be really happy that I had the opportunity to take care of [them] in that way,” Terman said.

Working with the flowers has been a comfortable haven for Terman to return to. Every student inevitably encounters challenges or obstacles, and it’s small activities like these that help build a sense of familiarity and tranquility.

“Having a routine to go to the field and express myself … was really important for my control over my life,” Terman said. “The farm and the flowers became a place of solace for me and gave me stability.”

“Have a color harmony — there are a lot of colors that are similar and compliment each other. That makes for a really decorative bouquet that could go in a house.”

“You could also do contrasting colors, where you have colors opposite [each other] on the color spectrum. That makes for a more dramatic bouquet.”

“One tip is that you should use an odd number of flowers for your bouquet. It [should not] look too symmetrical because art is a little bit more dispersed out.”

“A good rule is that you don’t want to see the stems of your bouquet: It’s more professional to use droopier or shorter flowers on the side.”

“When you have all the flowers that you want to put in your bouquet, make sure that when you cut them you are holding them in your hand. [That way], it looks exactly how you’re holding it. Otherwise, the stems will read-

design

Dystopian films serve as a warning of the unpredictable future

The grey, polluted sky looms above a desolate landscape. Once, colorful truffula trees covered the land. Now, nothing but stumps remain, and society is ruined by the greedy needs of the thneeds. This is a scene from “The Lorax,” an animated film that uncovers the unfortunate truth of industrialization and environmental destruction through the lens of a seemingly

dystopian universes seen on screen could reflect the future.

Palo Alto High School junior Brendan Giang, a student film writer and Paly Film Club participant, believes that films have the potential to shape one’s perception of the planet’s future, including the future of humanity.

“Just like parody humor, if we focus too much on the laughing ... it can create this sense of ‘Oh, that’s another world.’”

Sima Thomas, librarian

“[Watching environment documentaries] may give you hope and may give you despair,”

Literature student, believes these films can reveal insights regarding dangers to the environment.

“[Films are] a really interesting way to learn about real-world issues,” Yang said. “It puts into perspective what the worstcase scenario could look like. That’s something people really need because nowadays we can be kind of ignorant towards problems, and I honestly don’t think people will really realize how much harm we’re doing to the environment until something really terrible does happen.”

Similarly, for Paly journalism advisor Paul Kandell, dystopian media is a look into the future and the possibilities that could occur.

apocalyptic films often blur the lines between entertainment and environmental warning.

“[Films paint] a very clear path of how our world could just go into shambles, and that’s kind of scary,” Bapna said. “They’re helpful in the way they help people understand the possibility of these scenarios happening, but it also does create a lot of anxiety.”

Audiences may perceive dystopian films and media as pure fiction due to the uncanny and at times abnormal elements. Librarian Sima Thomas has seen how aspects of dystopia can desensitize the actuality that these movies portray.

“Just like parody humor, if we focus too much on the laughing or the fun aspects that aren’t actually as realistic, it can create this sense of ‘Oh, that’s another world. That’s not our problem,’” Thomas said.

Andrew Brown, president of digital marketing and distribution at Neon, believes that dystopian movies have always been relevant to concerns about the future. Neon is the independent film production and distribution company behind the recent five-category winner at the Oscars, “Anora.” They have recently released var