media partner of the year

United nations

2015 environmental Media Award leadership award 2008

BusinessMirror

www.businessmirror.com.ph

A broader look at today’s business n

Sunday, July 16, 2017 Vol. 12 No. 276

2016 ejap journalism awards

business news source of the year

P25.00 nationwide | 2 sections 16 pages | 7 days a week

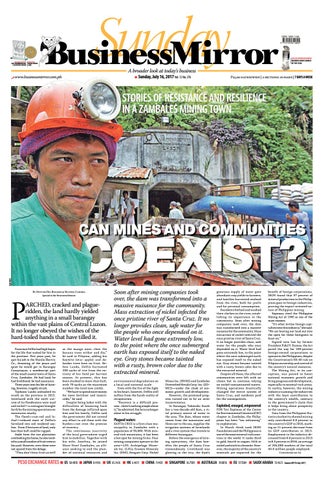

Stories of resistance and resilience in a Zambales mining town

Can mines and communities

FILE PHOTO

coexist? By Denver Del Rosario & Beatriz Zamora

P

Special to the BusinessMirror

ARCHED, cracked and plagueridden, the land hardly yielded anything in a small barangay within the vast plains of Central Luzon. It no longer obeyed the wishes of the hard-toiled hands that have tilled it.

Francisco Delfin had high hopes for the life that waited for him in the province. Five years past, he quit his job in the Manila Electric Co., dreaming of the peace and quiet he would get in Barangay Canaynayan, a nondescript part of the small coastal town of Santa Cruz, Zambales. He had land, he had livelihood, he had assurance. Three years into his life of farming, however, tragedy struck. Typhoon Lando unleashed its wrath on the province in 2015. Interlaced with the swift current of its floodwaters were mud and nickel—a contagion brought forth by the mining operations on mountains nearby. The flood—rust-red and lethal—reduced most of Delfin’s farmland into soil rendered useless. From 3 hectares of land, only less than half could be tapped. Aside from the rice plantation overlooking his home, he also tended to a small number of fruit trees in his yard. However, even these were not spared from the deluge. “ They don’t bear fruit as well

as the mango ones...then the banana trees wither and die,” he said in Filipino, adding his kaymito (st a r apple) a nd dalandan trees bore no fruit. Before Lando, Delfin har vested 200 sacks of rice from the entirety of his field per har vest season. At present, t his has been slashed to more than half, with 70 sacks as the ma ximum number the land now yields. “We have to spend more money for more fertilizer and insecticides,” he said. Despite being laden with the difficulties of bouncing back from the damage inflicted upon him and his family, Delfin said the government did not extend any effort to aid them with the burden—not even the promise of recovery. T he cont i nuou s i n ac t iv it y of the loca l gover nment urged him to mobilize. Together w ith his w ife, Josefina, he joined Move Now! Zamba les, an a l liance seek ing to end the plunder of nationa l resources and

PESO exchange rates n US 50.4810

Soon after mining companies took over, the dam was transformed into a massive nuisance for the community. Mass extraction of nickel infected the once pristine river of Santa Cruz. It no longer provides clean, safe water for the people who once depended on it. Water level had gone extremely low, to the point where the once submerged earth has exposed itself to the naked eye. Gray stones became tainted with a rusty, brown color due to the extracted mineral. env ironmental degradation on a loca l and nationa l sca le. Even with the fire of the fight in his heart, however, Delfin still suffers from the harsh reality of recuperation. “Recovery is a difficult process...there’s nothing simple about it,” he admitted. But he is no longer alone in his struggle.

Plagued waters

SANTA CRUZ is a first-class municipality in Zambales with a population of 59,000. With mineral-rich mountains, it has been a hot spot for mining firms. Four mining companies operate in the area—LNL Archipelago Minerals Inc. (LNL), Eramen Minerals Inc. (EMI), Benguet Corp. Nickel

Mines Inc. (BNMI) and Zambales Diversified Metals Corp. Inc. (ZDMCI)—under the cloak of economic growth and development. However, the promised progress turned out to be an utter inconvenience. In Barangay Tubotubo South lies a two-decade-old dam, a vital primary source of water in the area. The dam, whose water comes from the mountains and flows out to the sea, supplies the irrigation systems of farmlands and a river system that travels to different barangays. Before the emergence of mining operations, the dam benefits the people of Santa Cruz tremendously. Livelihood was glowing in the city; the dam’s

generous supply of water gave abundant crop yields to farmers; and families harvested seafood from the river, both for profit and for personal consumption. Residents bathed and washed their clothes in the river, establishing its importance in the community. Soon after mining companies took over, the dam was transformed into a massive nuisance for the community. Mass extraction of nickel infected the once pristine river of Santa Cruz. It no longer provides clean, safe water for the people who once depended on it. Water level had gone extremely low, to the point where the once submerged earth has exposed itself to the naked eye. Gray stones became tainted with a rusty, brown color due to the extracted mineral. Despite all these, the affected communities were left with no choice but to continue relying on nickel-contaminated waters. Mining operations drastically changed the entire system of Santa Cruz, and residents paid for the consequences.

Exploited, enraged, empowered

FOR Teri Espinosa of the Center for Environmental Concerns (CEC) chapter in Zambales, the Philippines has been “too welcoming” to exploitation. In March think tank IBON Foundation said the Philippines is one of the most mineral-rich countries in the world. It ranks third in gold, fourth in copper, fifth in nickel and sixth in chromite. However, the majority of the country’s minerals are exported for the

benefit of foreign corporations. IBON found that 97 percent of mineral production in the Philippines goes to foreign industries, proving the export-oriented nature of Philippine mining. Espinosa cited the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 as one of the main reasons. “It’s what invites foreign capitalists into this industry,” she said. “We are leaving our land out into the open for these foreigners to feast on.” Signed into law by former President Fidel V. Ramos, the Act paved the way for 100-percent foreign-owned corporations to operate in the Philippines, despite the Constitution’s 60-40 rule on Filipino ownership and control of the country’s natural resources. The Mining Act, in its conception, was poised to boost national economic growth and bring progress and development, especially in mineral-rich areas. In reality, however, the mining industry is among the industries with the least contribution to the country’s wealth, contrary to the government’s claim that it helps bring about prosperity to the country. Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority showed mining only contributed 0.8 percent to the country’s GDP in 2016, marking an 11-percent decrease from its GDP contribution in 2015. Employment in the industry decreased from 0.6 percent in 2015 to 0.5 percent in 2016, an average of 204,000 workers of the total 40.8 million people employed. Continued on A2

n japan 0.4456 n UK 65.3426 n HK 6.4651 n CHINA 7.4403 n singapore 36.7509 n australia 39.0016 n EU 57.5584 n SAUDI arabia 13.4623

Source: BSP (14 July 2017 )