If all 45 billion years of Earth’s history were to be condensed into a single day and played out, more than three million years of footage would go by every minute. We would see ecosystems rapidly rise and fall as the species that constitute their living parts appear and become extinct. We would see continents drift, climatic conditions change in a blink, and sudden, dramatic events overturn long-lived communities with devastating consequences. The mass extinction event that extinguished pterosaurs, plesiosaurs and all nonbird dinosaurs would occur 21 minutes before the end. Written human history would begin in the last tenth of a second

05

Thomas Haliday, Otherlands: A World in the Making, 2022

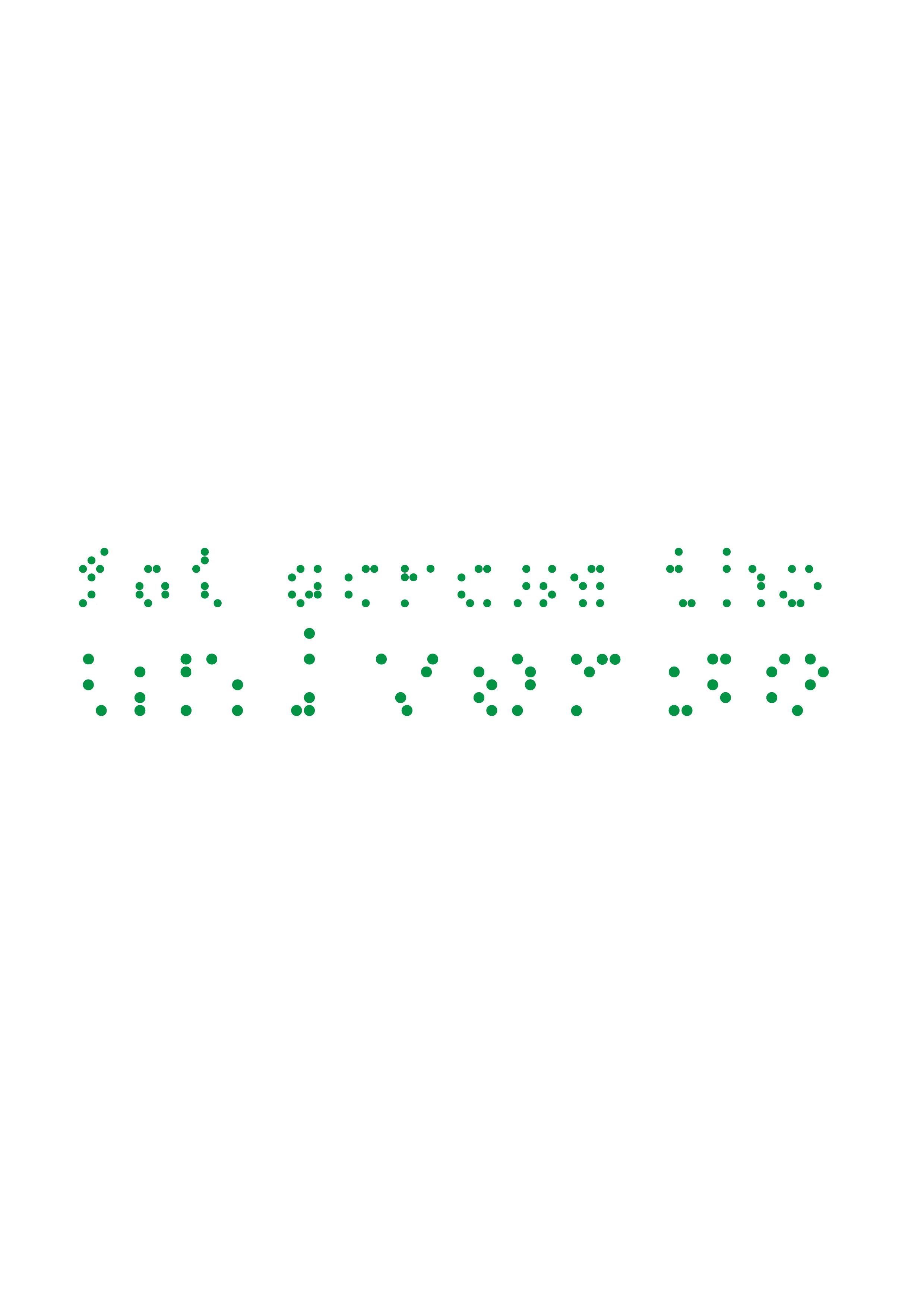

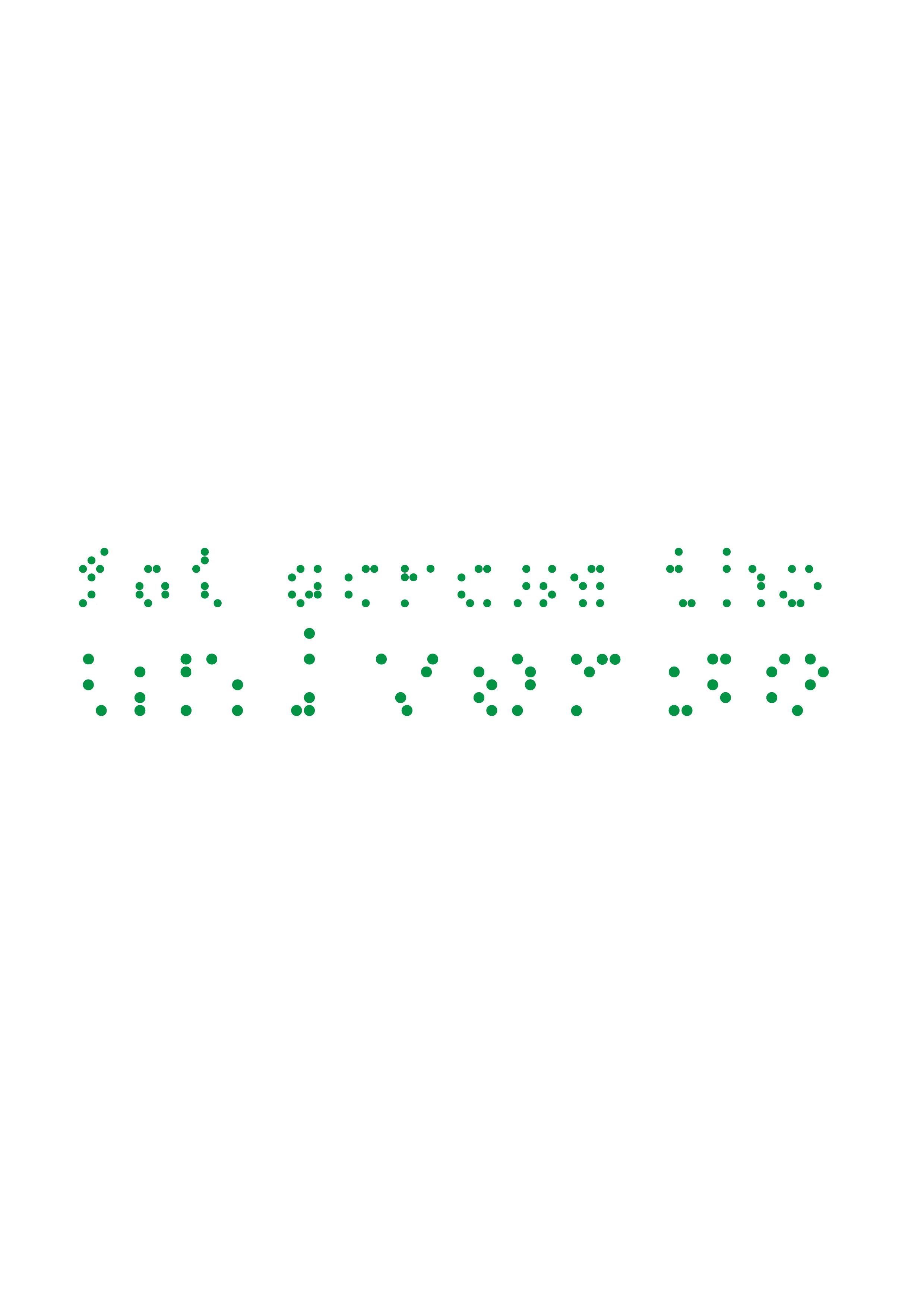

This project served as an exercise in embodied research and developing a deeper relationship to the environment. It urged us to question our role as designers and visual artists. Fat Across The Universe invites its viewers to experience the estrangement and connection towards fat. Not just as a life giving material, but also as a land and world forming entity through which geology, biology and fiction blur into one another. To fully examine the world, or to even begin doing so, we must come back to it. This publication is a reflection of the journey we took that led us to celebrate being part of the universe at large. We treat the earth as our canvas and precedence, in its entirety, an amalgamation of timelines across bodies and histories, a place of encounter and fluidity. A place where the only constant is change itself. 1

07

1. Chicago. Butler, Octavia E. Parable of the Sower. New York :Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993.

Encountering fat as a tangible material demanded that we situate ourselves within it. Where fat becomes the key character, the ‘who’ of the conversations between one another during and after studio hours. One of the first such encounters was with the fat berg in the life sized cylindrical tank in the studio. A soft matter, hardly moving, yet sensitive to temperature that it had to be suspended in a body of water. This particular entry point to thinking about the fat berg as sculptural deeply affected the rest of our process. In her essay titled Sculpture in the Expanded Field, Rosalind Krauss speaks about the rupturing of boundaries within which ideas of sculpture were neatly kept.2 She emphasises on problematizing the nature of sculpture and the fields of art and design within which it can exist.

We set onto countering the sitelessess by using rendered fat to build a site. Challenging our own initial feelings about fat to delve deeply into the ritual-like quality of the task at

09

2. Krauss, Rosalind. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences, The MIT Press 8, no. no. 01 (1979): 30-44. Accessed February 3, 2018.

hand, which was the rendering process itself. Focusing on the repetitive acts of cutting, cleaning and heating. This intimate proximity became a place of gathering observations, the most important ones being about time sensitivity and shift between states of matter.

Working outside the confines of preconceived design and the act of making, a word that kept coming ‘extraction’. Material is always extracted from elsewhere. While building is an additive

procedure, this dichotomy of relocating, rebuilding, adding and subtracting then also became a part of the ritual we were setting for ourselves. We say ritual because of the embodied experience of it all.

11

THE SITE

The reason why a site becomes an important part of the journey is because had it not been for it, the conditions within which we did our work would not have been created. The conditions are important because they allude to the sensorial and ritualistic method of working with fat which gave us the room to acknowledge that space and pace were going to become key factors of our project.

Home

Our everyday lives are fast paced and function on the basis of compartments and separation. That is not simply because we lack the desire to engage more consciously with our surroundings but also because of systems like capitalism and mass production that thrive on this separation. By rendering fat at our homes in our utensils we already began the act of re-familiarising ourselves with it in a domestic space.

Studio

The fat lab became the second place of work, which we entered in a deep thinking phase because the process had

already begun. Having a process meant that our notion of time would change and rely on the work we did. Here

time takes on a different meaning, it warps around the beginning, middle and end of the task of the day instead of morning, evening or night.

In-between:

This third space was everything between the home and the studio. It became our learning ground, a point of reference, a place where we did not directly engage with fat but were able to build acute connections and observations. In the book Speculative Everything, Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby talk about the importance of thought experiments.3 They suggest that in the context of fiction and design, inspiration and willingness to try new things are the main sources of drive.

Fat Across The Universe definitely has fictional overlaps which brought a sense of ease to our process, because it took away the designer’s need to solve problems or invent something.

It was driven entirely by our conversations and the organised yet organic methods of co design. It is also why this publication is divided into sections and two of them are titled ‘In Conversation With Fat’.

17

3. Dunne, Anothony , and Fiona Raby. 2014. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

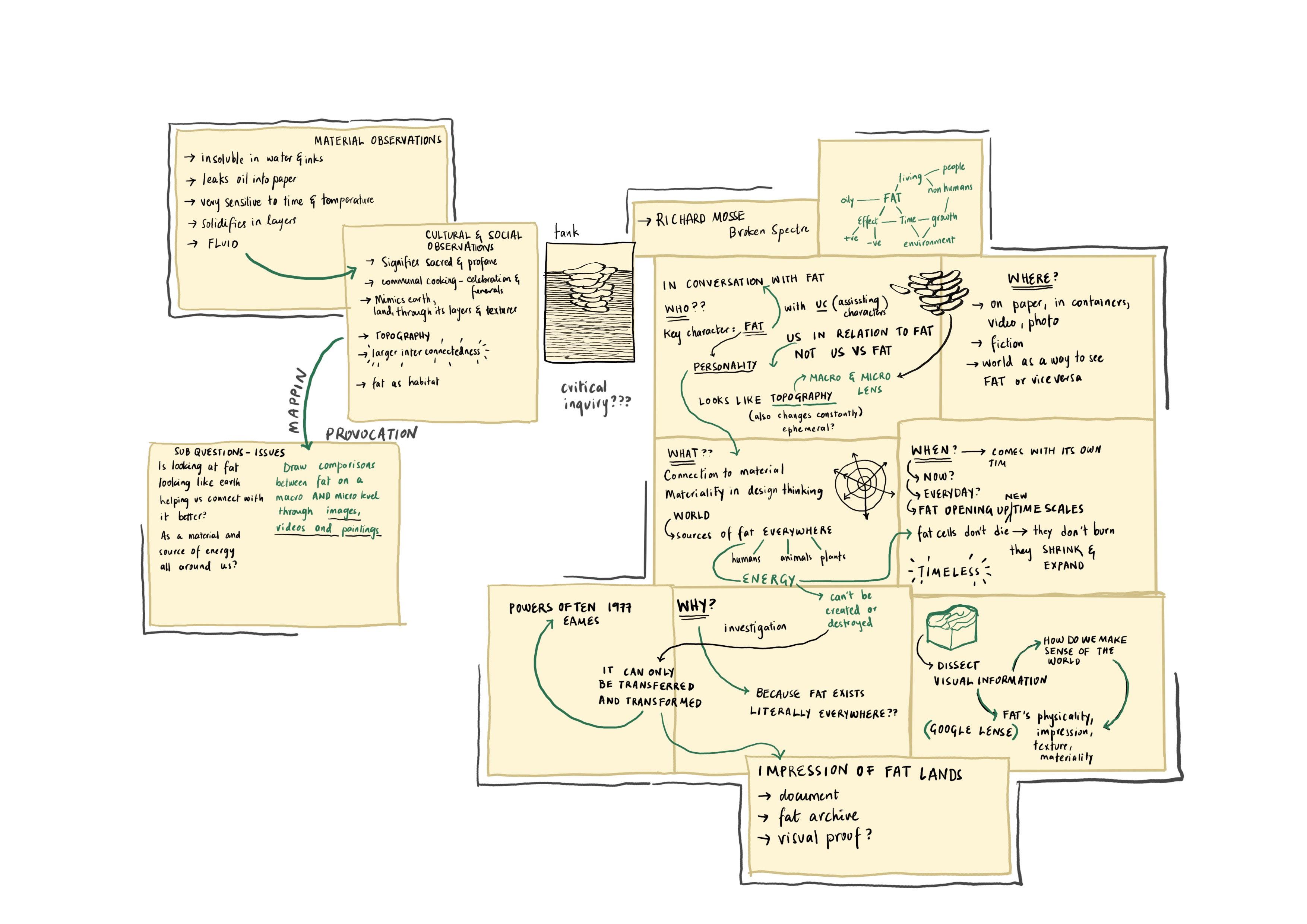

TRAVERSING FAT LANDS

A challenge or inquiry that came up more than once was the field or discipline of the project. While we understood that this was an interdisciplinary platform we couldn’t help but ask questions like ‘are we making deductions here?, ‘does everything we do have to be backed up scientific or social facts and statistics?’. Kees Dorst suggested that

collaborative design, or speculative design exists between what we know as deduction and induction. He used the word abduction for designers, which is a way to frame many ideas together to reach multiple conclusions and designs. 4

A big part of this journey was the constant flux between familiar and unfamiliar territories.

19

4. Steen, Marc. “Co-Design as a Process of Joint Inquiry and Imagination.” Design Issues 29, no. Spring 2013 (2013): 16-28. Accessed March 1, 2023.

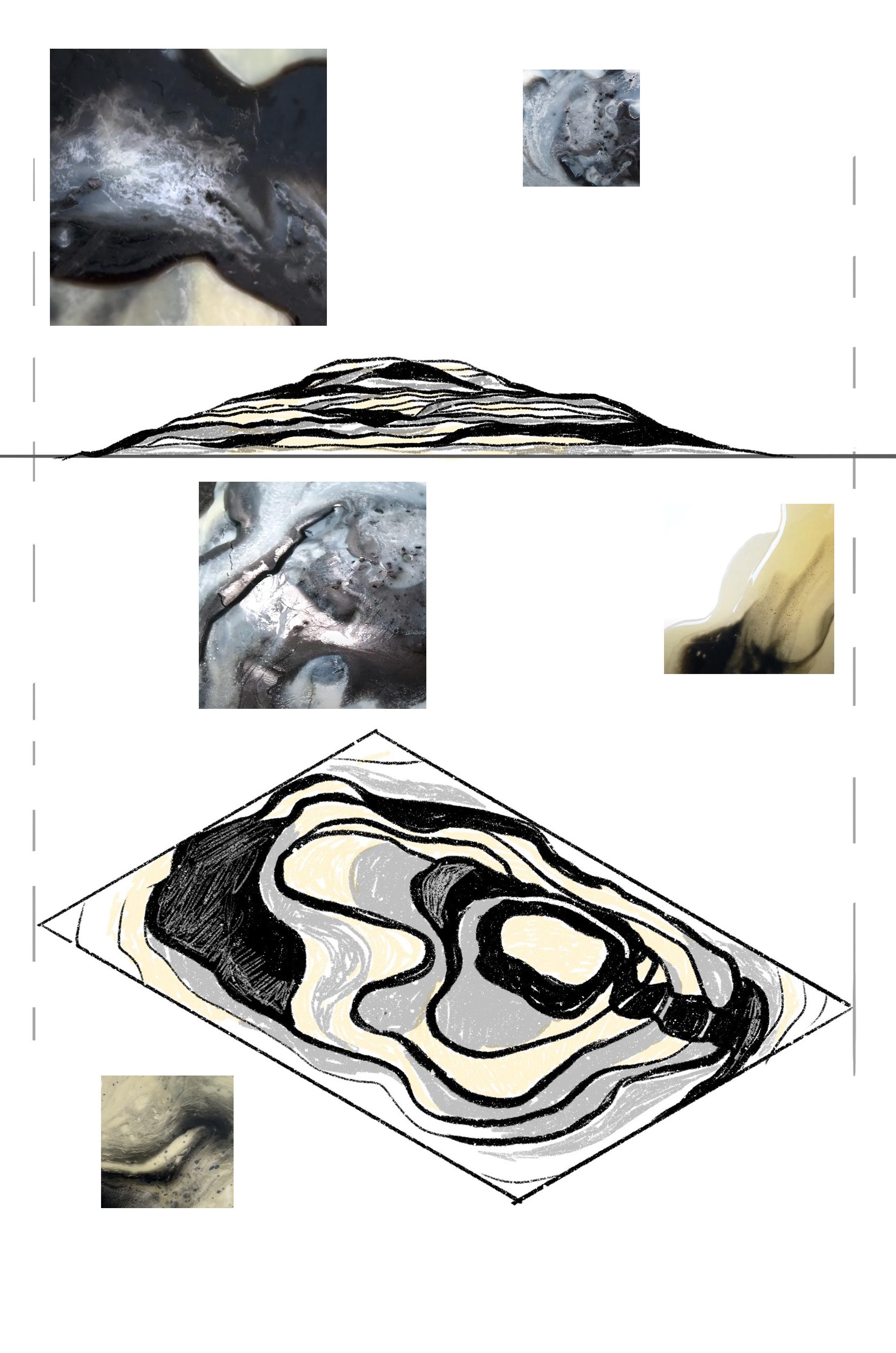

Fat Lands:

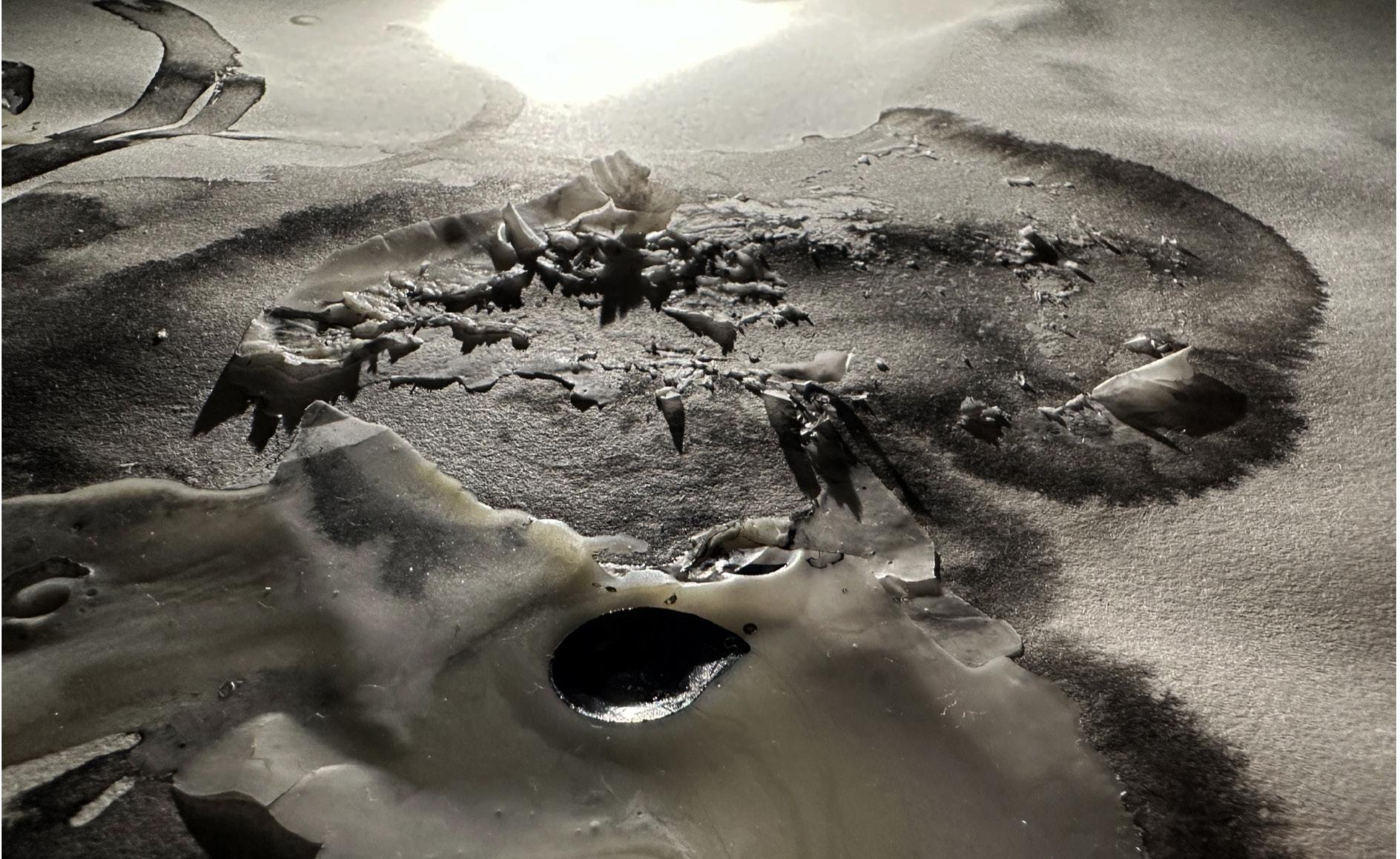

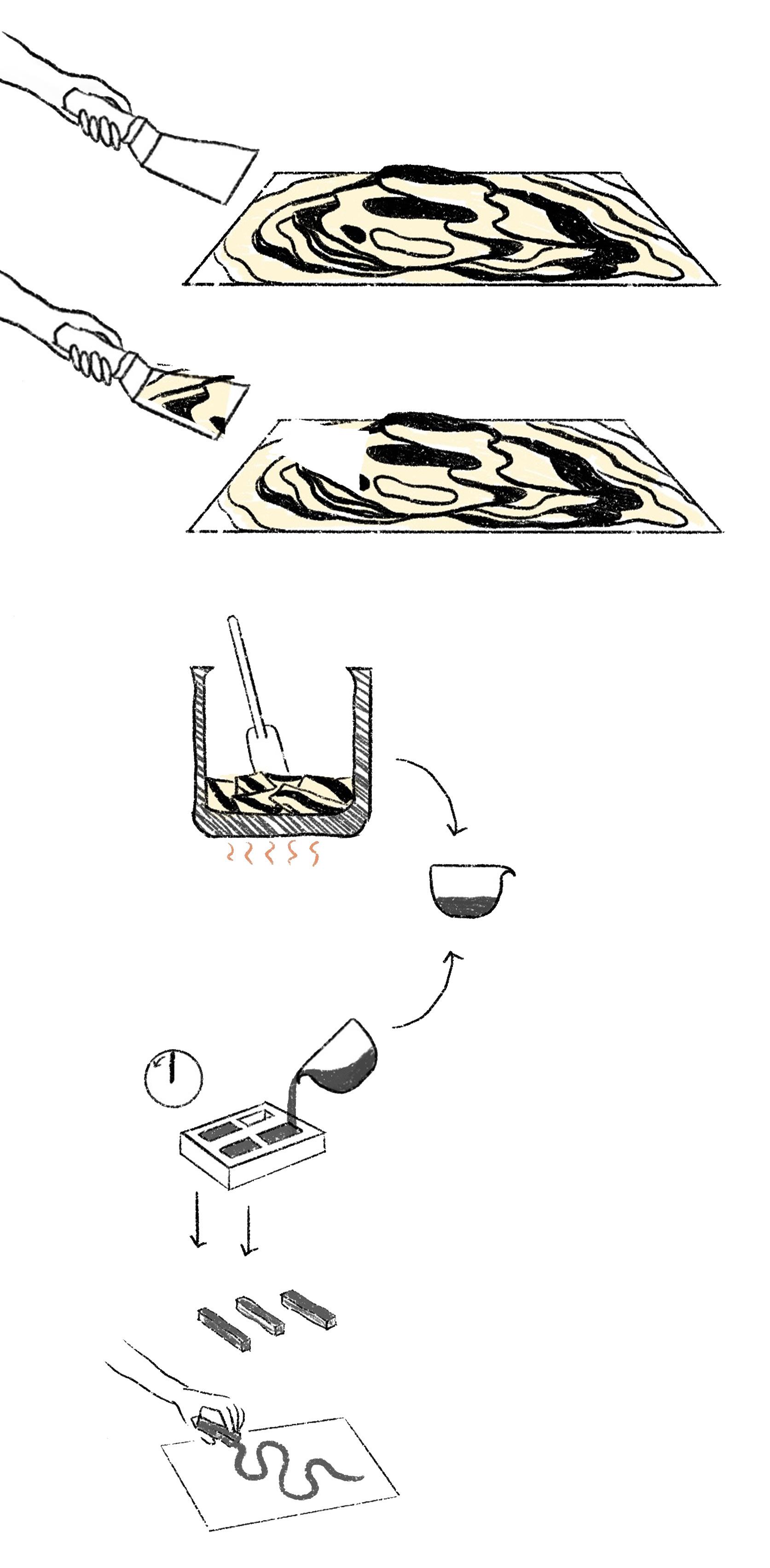

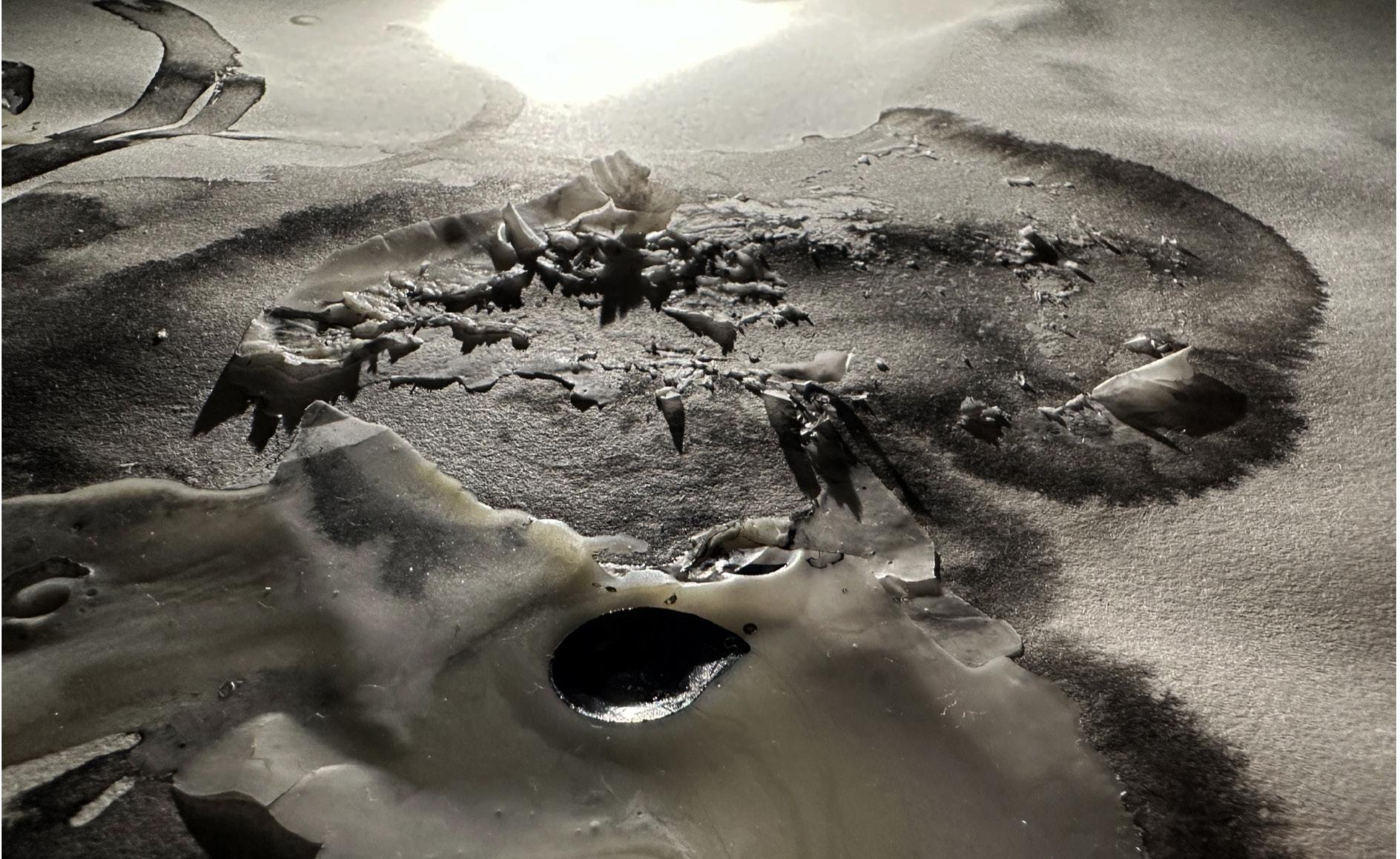

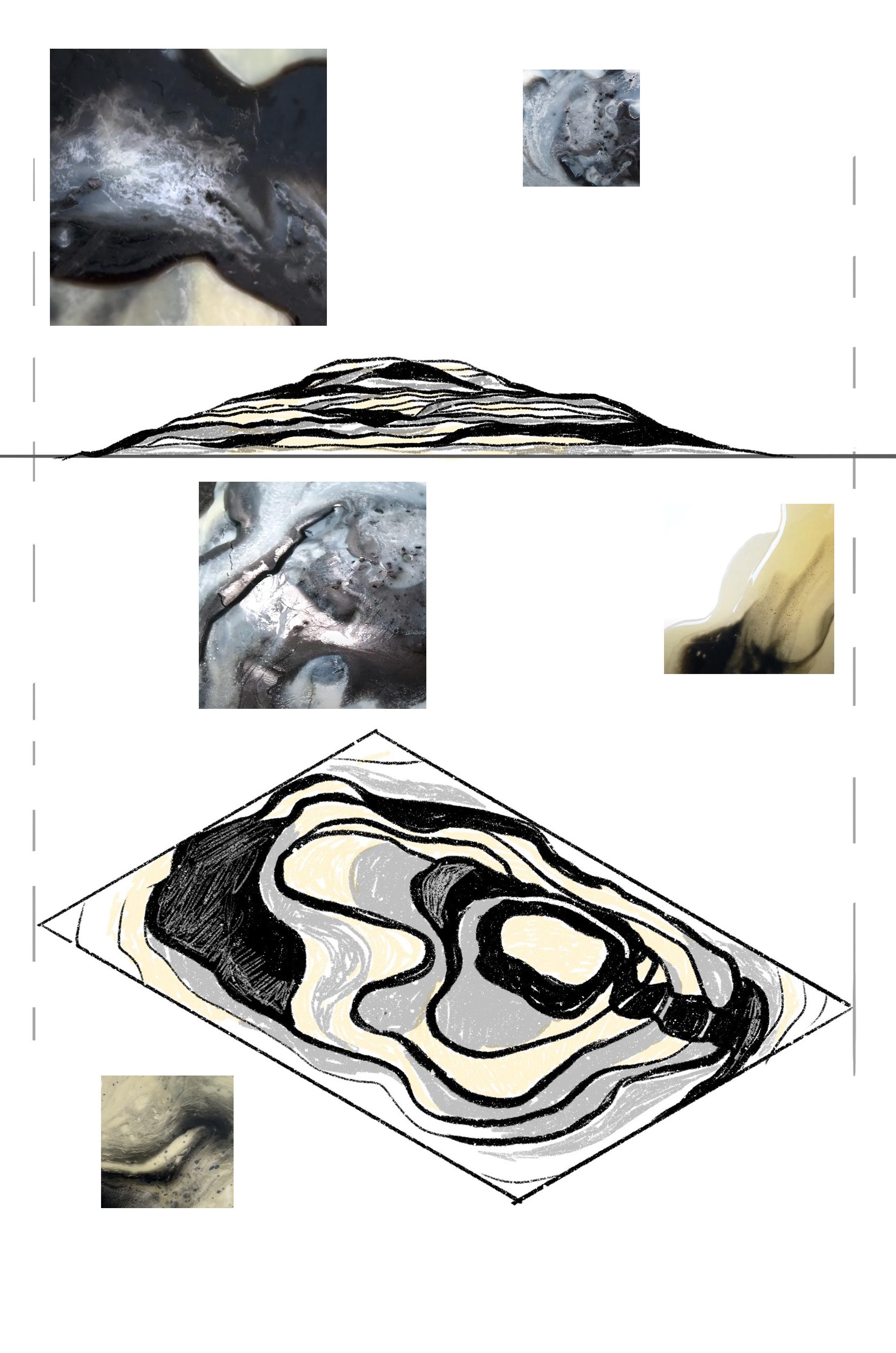

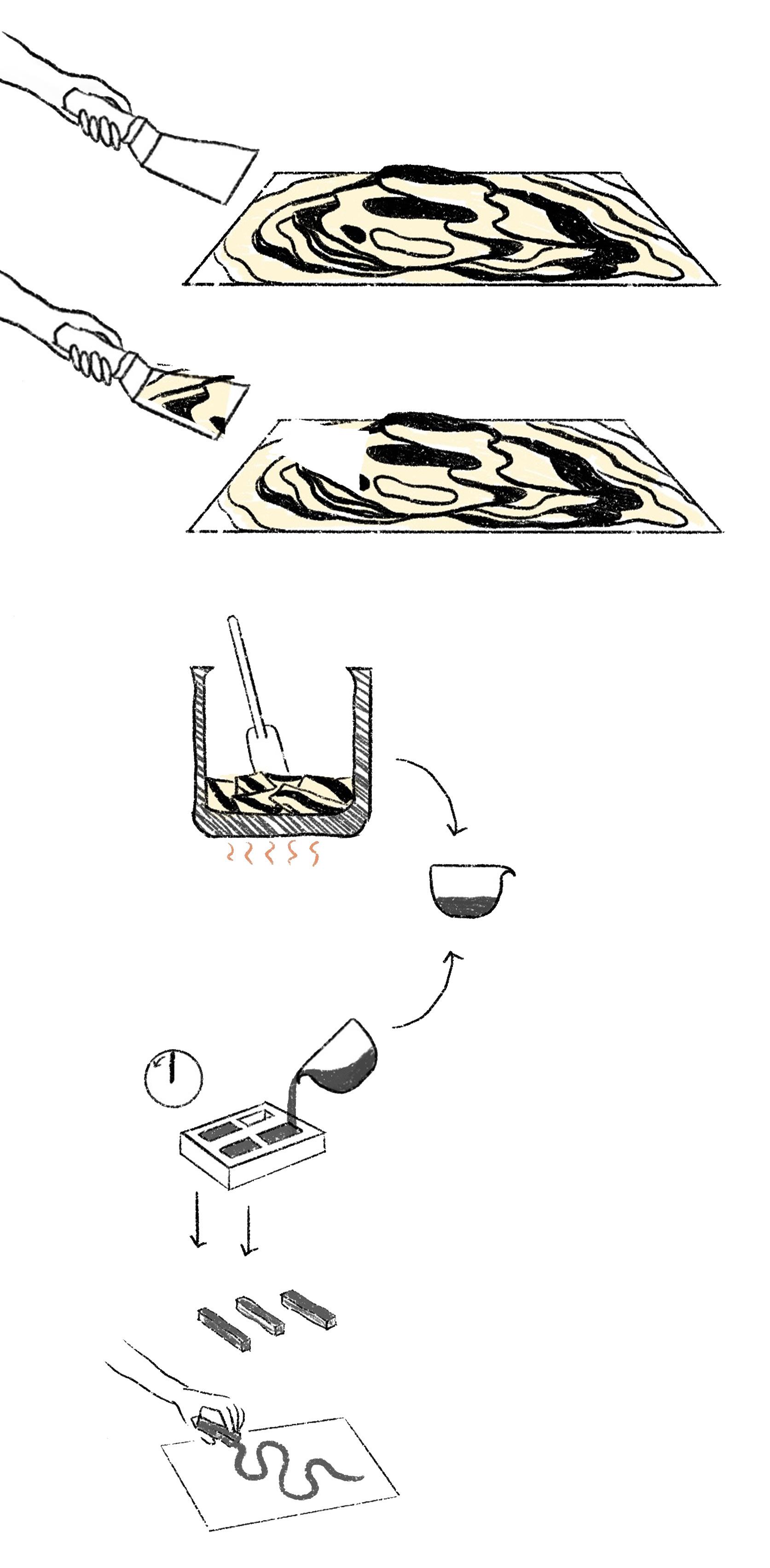

Melted fat poured on paper, sometimes in pure state, sometimes mixed with ink or oil paint. Observing fat in layers reflected the passing of time and movement. This included pouring layers of fat at various intervals and watching it move towards the corners of the paper.

Over days fat continued to seep into paper and travel on it. The thicker layers began looking like land and topography. There was an expansion of time and of our minds caused by the procedure and repetitive act of melting fat. The elasticity and malleability of fat demands vigilance and presence. Since it is mostly soundless the sonic backdrop to traversing fat lands was our own whispering, talking, ushering and breathing.

The sensitivity of fat to every corner of the room depending on what intangible forces it came in contact with was remarkable. From its proximity to the radiator, window, other sources of light or our own bodies. Closely registering this movement by a generally known to be static object creates room for

inner movement and transformation.

Joseph Beuys’ seminal work is directed towards the human consciousness and its ability to transmute.5 His work is specifically able to take such a fragile task and execute it masterfully because of the artist’s absolute conviction that we share a unified complexity, that all things human, animals, plants and the earth are interconnected. Drawing from his work and allowing the material to speak for itself, that is, to exist outside the constraints of language and meanings we give to objects, opened up other narratives and possibilities. It involves a deeper listening, a willingness to be stirred and experiencing everything as an extension of yourself. In a group setting this became a collective exercise, evoking curiosity and emotive responses.

Relating this to the idea of a world, an outer and inner world unfolds further contemplations on visual cultures, globalisation and the way we consume information in the 21st century. Everything we do in this age is followed by the need to be online, searching for answers outside instead of within, at a much higher

pace with millions of answers to one question. This takes us further from the environment and our ability (and possibly need) to engage with it, to bring ourselves to life. This is not to disregard the world wide web but to address the additional layer of our generations’ consciousness and the way we relate to the world. We decided to insert the fat land images on the google image search tab and were overwhelmed with the way it blew up by giving us photo references to every image which ranged from single cell organisms to the geography of Uranus. In some ways traversing through this information felt a lot like the 1977 film titled Powers of Ten.6 That is, a journey across space and time from micro to macro levels.

5. Suquet, Annie. “Archaic Thought and Ritual in the Work of Joseph Beuys.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, The University of Chicago Press on Behalf of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, no. Autumn, 1995 (1995): 148-162. Accessed February 25, 2023.

6. Eames, Charles , and Kees Boeke, directors. Powers of Ten. Eames Office, 1977.

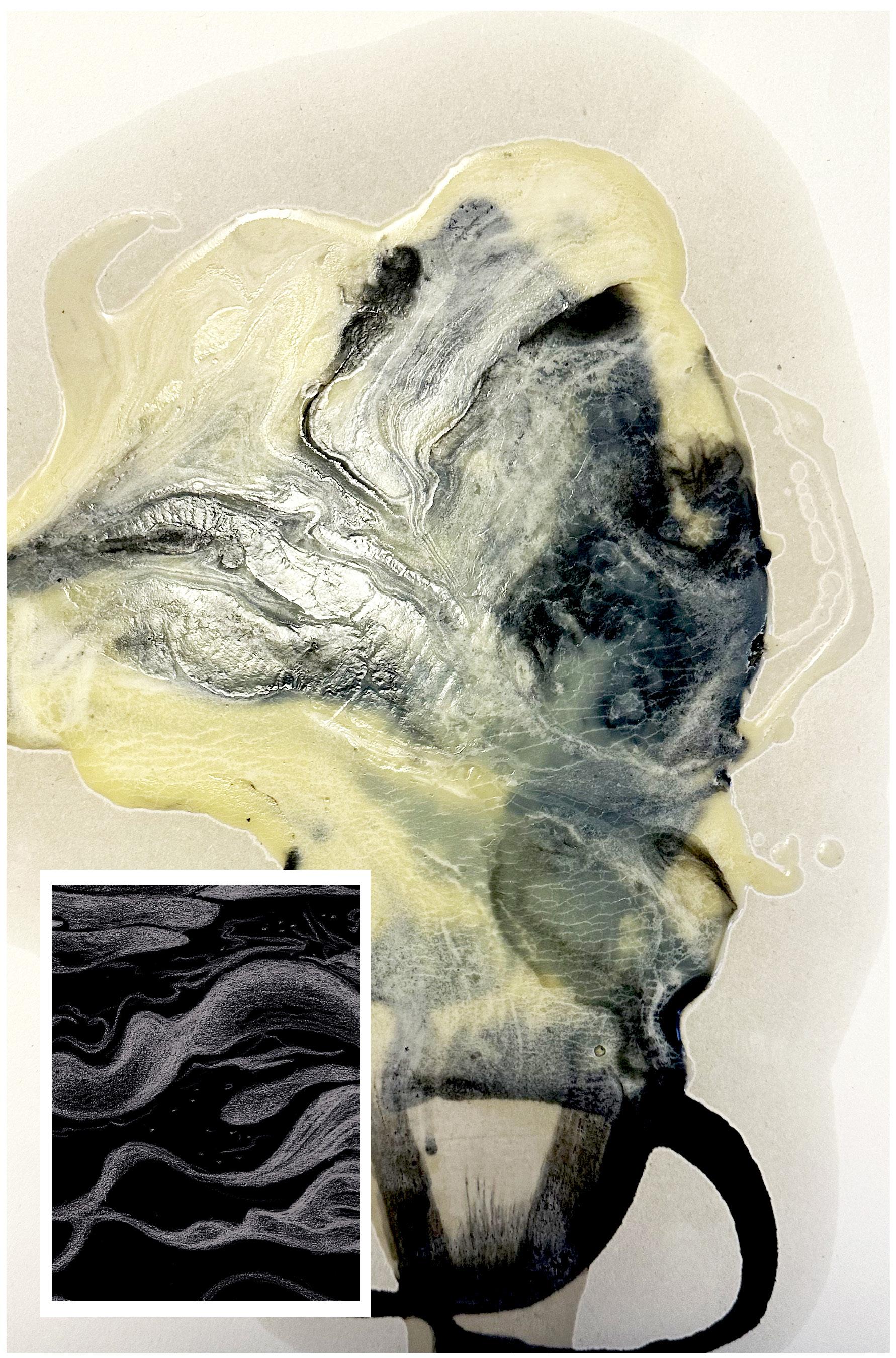

GREASE PRINTS

While the fat islands were being poured on paper, the slow spreading of oil and grease was yet another evidence of time and the change in states of matter. If grease is on paper is it solid or liquid because it is so thinly embedded within paper it is hard to tell. Reflecting on our earlier conversations about making as an act of extraction we took sheets of paper and kept them on top of the island, lightly pressing our fingertips on it, letting the heat transfer some of the grease onto the paper. The slowness and minuteness of this extraction even within the confines of our lab added

to a much larger picture of thinking about topography as contracting, expanding and breaking. This kind of extraction or absorption was only visible against something, a source of light, lighting up like an x-ray or a cyanotype that reacts to the Sun’s UV Rays. Building the fat islands everyday and using paper to build a blueprint of its timeline added another layer to the repetitive actions we were relying on to address our connection to fat. Physicists’ research on condensed matter, for example, David Bohm was inspired by this branch of physics because the freedom that was exhibited by atoms and electrons when matter goes from one state to another was inspiring.7 There is a poetry to physics in the way it relates to the entire universe and that is what attracted us to the idea of using simple tools like sunlight, heat and paper to build these prints that singled out unique information about the lands that were not visible to our naked eye. Narrow fissures, fluidity, sometimes even the thickness of the layer, grains and air bubbles all made an impression on the paper. Using fat to build the earth and then building its map and history gives the project

23

a fictional aspect but fiction is always informed by non fiction.

7. Kojevnikov, Alexei . “David Bohm and Collective Movement.” Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 33, no. no. 01 (2002): 161-192. Accessed March 1, 2023

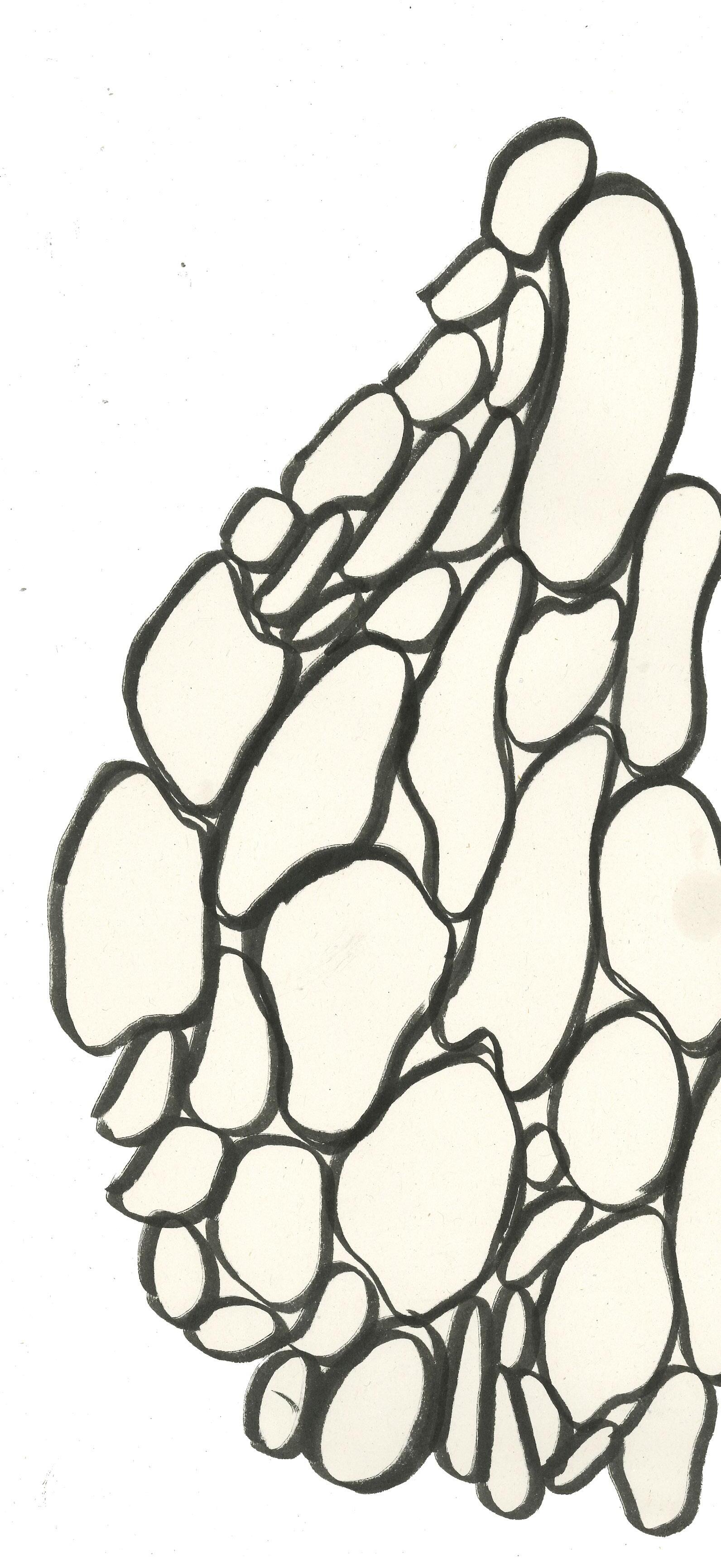

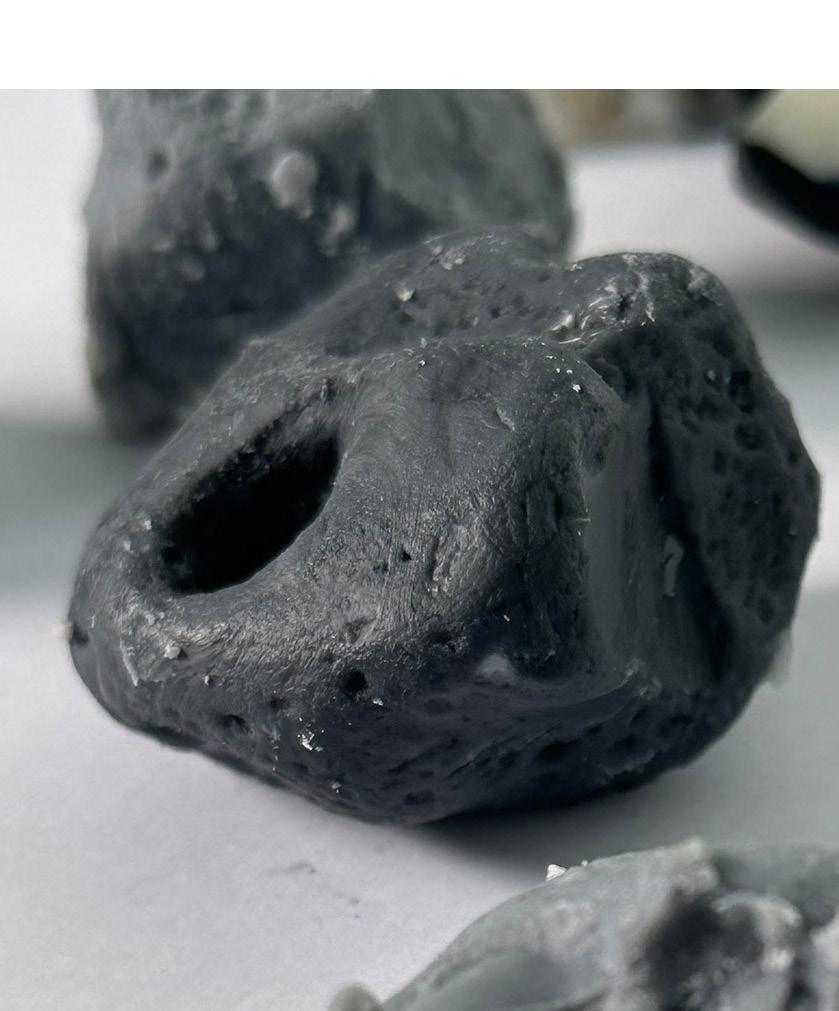

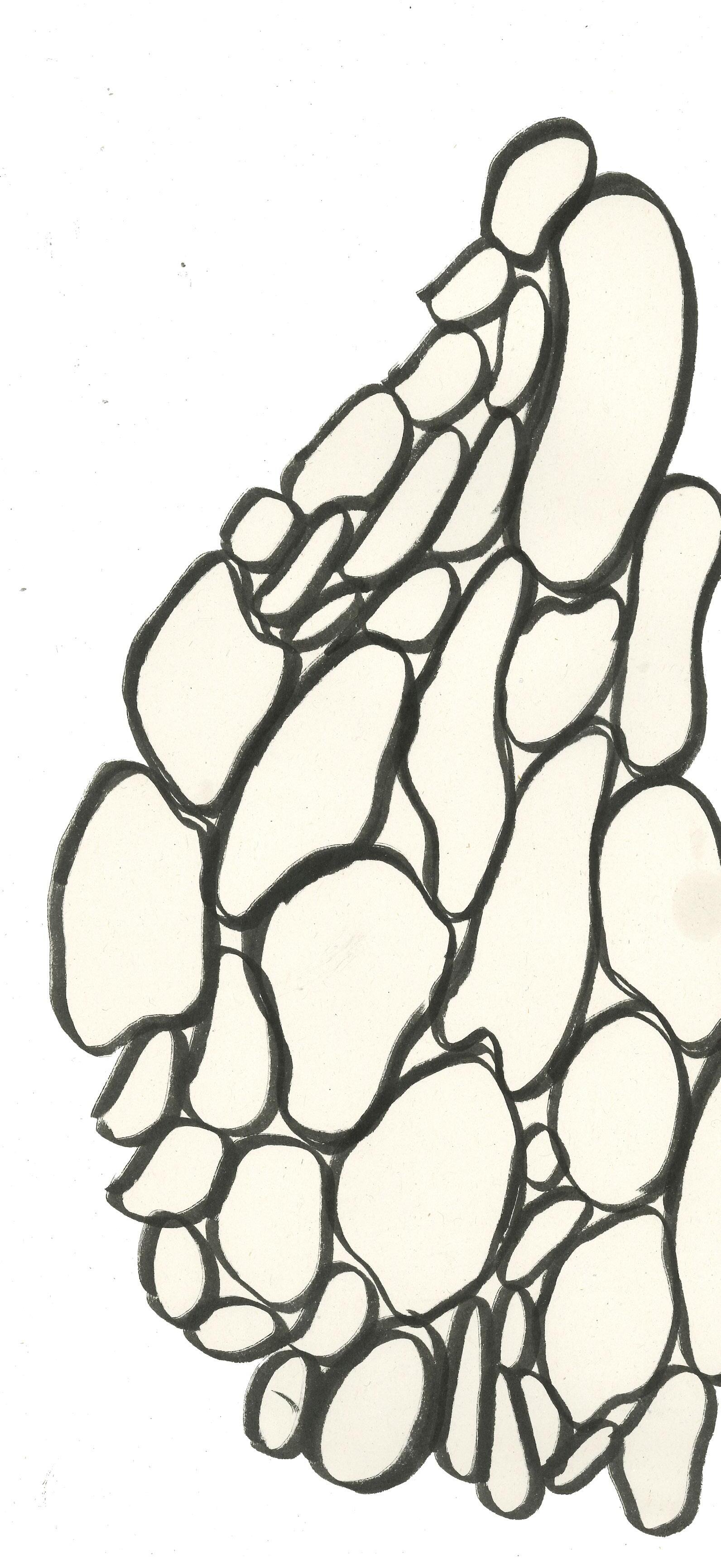

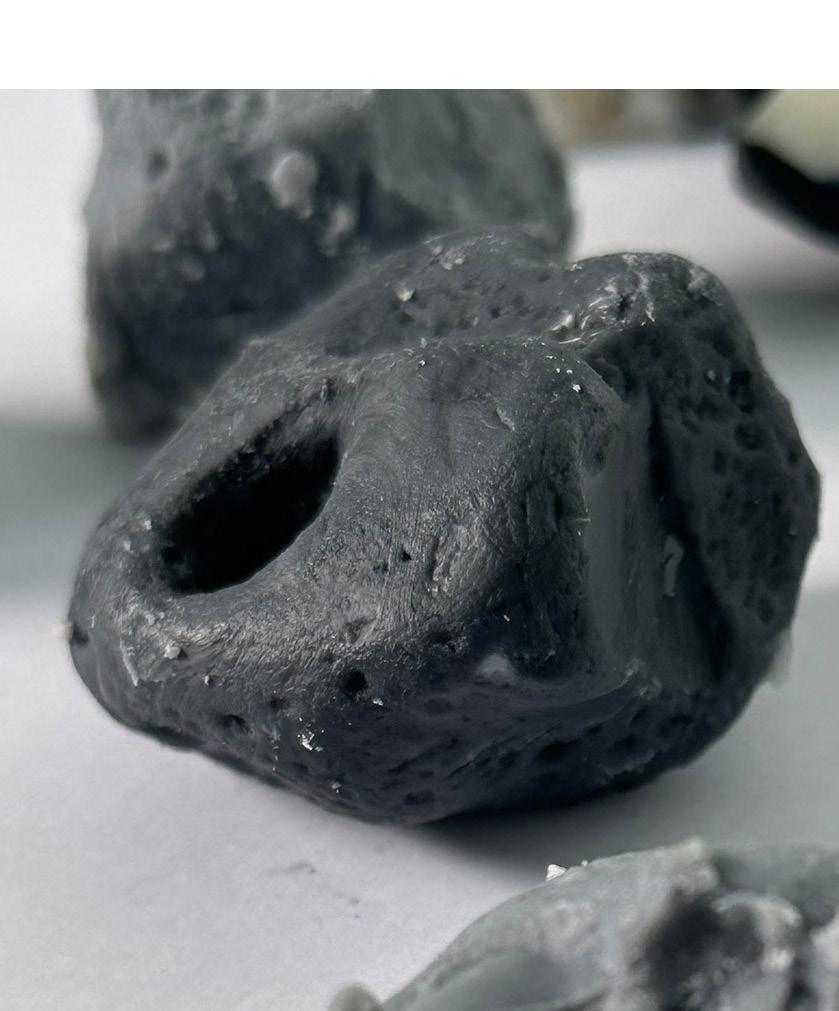

MIMICKING ROCK MATTER

In the book titled Humanising Science, author Rebecca Kamen investigates the nexus of art and science as the route to enlightenment.8 According to her artistic and scientific experiments both come from a place of intuition and the need to make the invisible visible. While we used fat to build islands, or what looks like islands on satellite images of the earth. Zooming in to rocks and pebbles and using them to build fat rocks was a way to give into our curiosity. Rocks carry metal and other minerals within them, which we get access to via extraction and melting. Using fat to mimic rock matter is another way to look at earth, from a more micro or ground level point of view. While fat completely takes the shape of the rocks, it glistens, softens and changes form as soon as we touch it. There is a mystery and poeticism to it, watching our soft bodies affect what seems like rock so quickly. The juxtaposition of the earth and its slow timeline, the slow paced process of fat over the ten weeks, to the sense of slippery urgency that fat puts one in as soon

as it comes in contact with latent energy (from our bodies and its own heat) is what always stands out.

25

8. Kamen, Rebecca. 2020. The Extraordinary Partnerships. Lever Press.

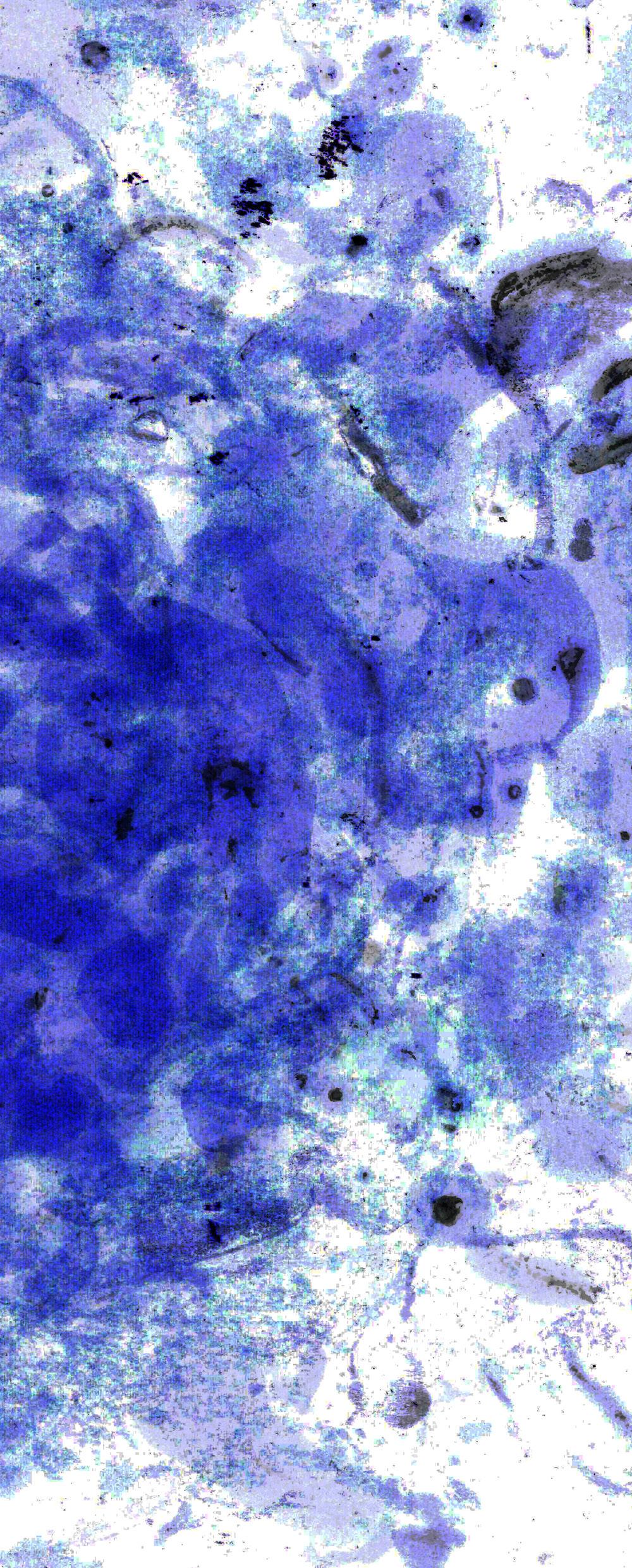

RISO LAYERS

Bushra

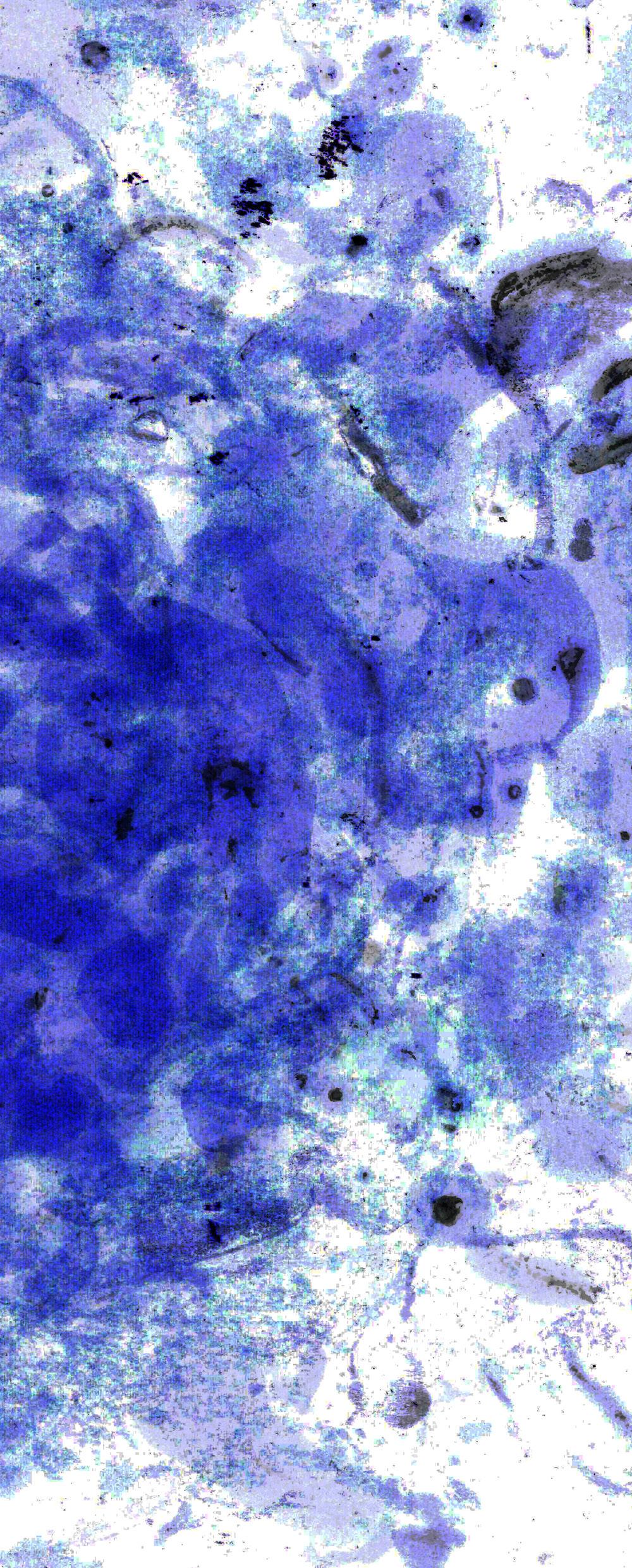

Working within the confines of Riso printing technique helped with the grease prints that were a part of our project. The fat prints carried various films of fat layered on top of each other over time. Dealing with specific aspects of reading visual information and in this case building the fat land again allowed me to undo the process of building the

fat lands through an entirely different medium and expression.

Each mastercopy carries separate information and the precise registeration would lead to an exact reconstruction. These mastercopies alone did not carry similarities to topography but together they created visually gripping images. It brought me back to elementary school when adding pigment to cheek cells and putting them under a microscope was a fascinating method to study fat.

FAT MEDITATIONS

Shraddha More

I came to fat with curiosity and a strange awkwardness of not knowing the material. As we dripped melted fat into the water, I was unsure what I was supposed to look at and what observations I was supposed to make. Even though I continued to stay in this muddle for a while, I was struck by how meditative I found this process to be. I would have never associated dripping fat into the water as meditative. But then we live in a world of connections we don’t make. As much as the process was engrossing I dismissed it as my naivety.

It is not possible to know a subject truly without seeing where it touches other fields of knowledge. Having a fair enough understanding of ink as a material, dripping fat and ink on paper made sense. We witnessed fat and ink converge to take their form and create ever-changing landscapes. Every time we tried to document, the fat landscape would have changed its form. This dynamic nature of the fat was striking. It was clear to us that fat was extremely time sensitive. It was amusing to observe how quickly it changed its terrain. The change remained ever unknown. Fat maintained its enigmatic personality throughout. Witnessing this dynamic phenomenon was again meditative. This nature of fat demanded us to be fully present with it. Having no preconceived notion about the materiality of fat galvanized us to simply watch with intention and not impose our parameters. The science of observing with intention and curiosity made the process meditative. The material demand us to note beyond what we know. Not having agency over the material helped us remove ourselves from the process and focus on fat and

its behaviour. It created a psychological distance between us and the material. It required us to take a step back and transcend the immediate moment in our minds. It was not passively watching but an active mental process to note down its characteristics. It also influenced our decision-making. It helped us to see the full picture, note the details that mattered and gave a direction to further contextualize those details within a broader framework of our process.

LOCATING FAT IN CHINESE POETRY

Xin Li

29

31

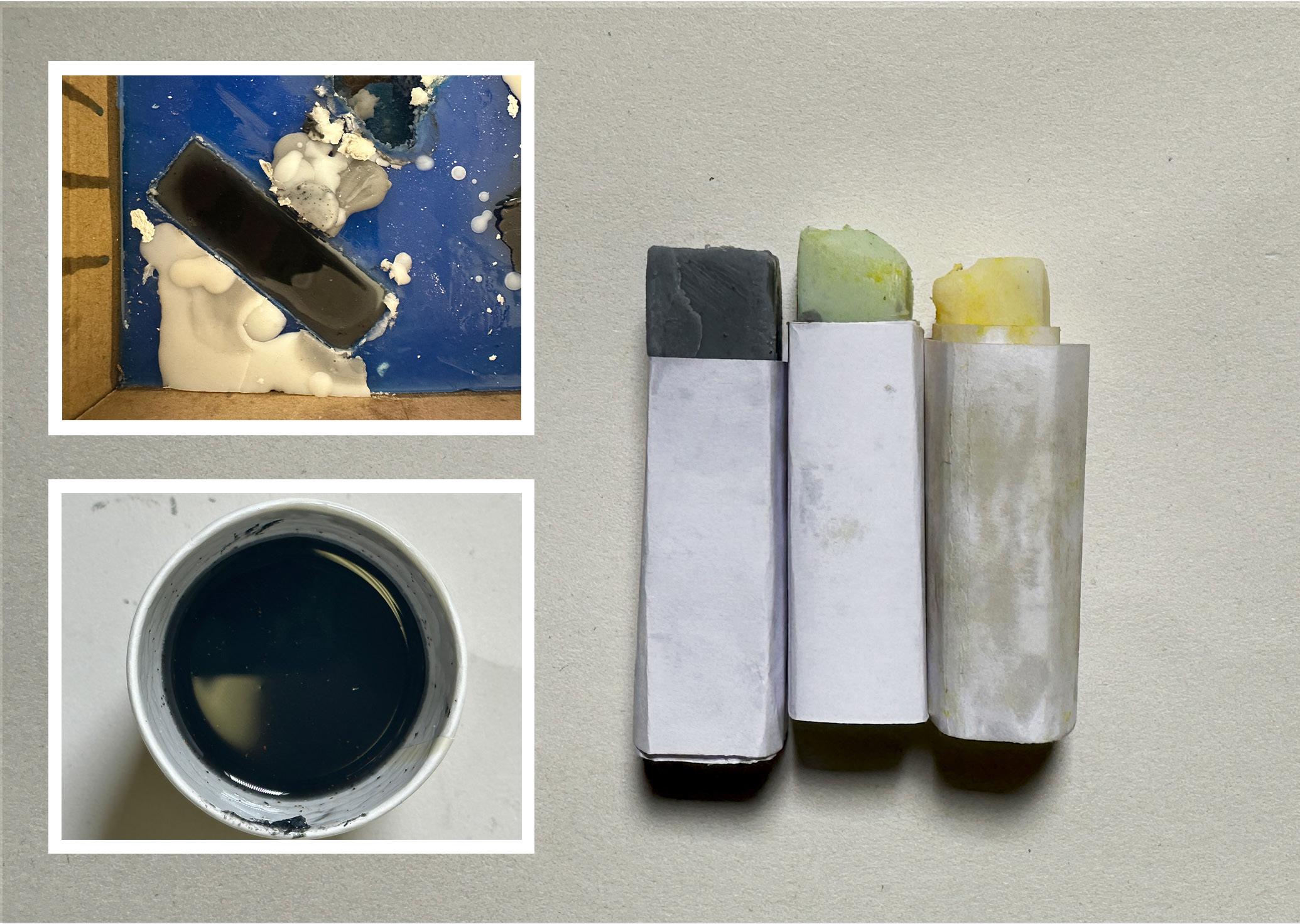

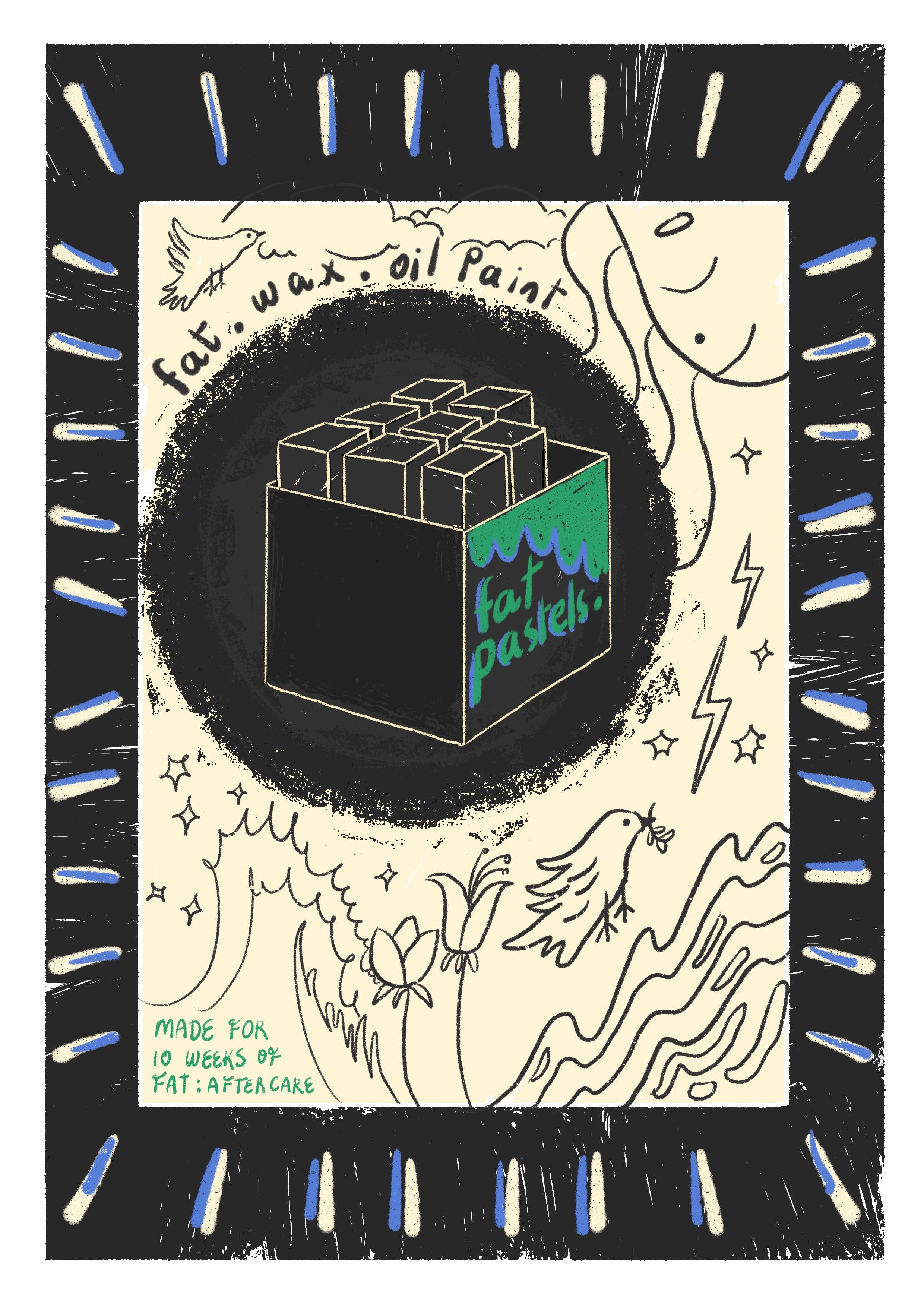

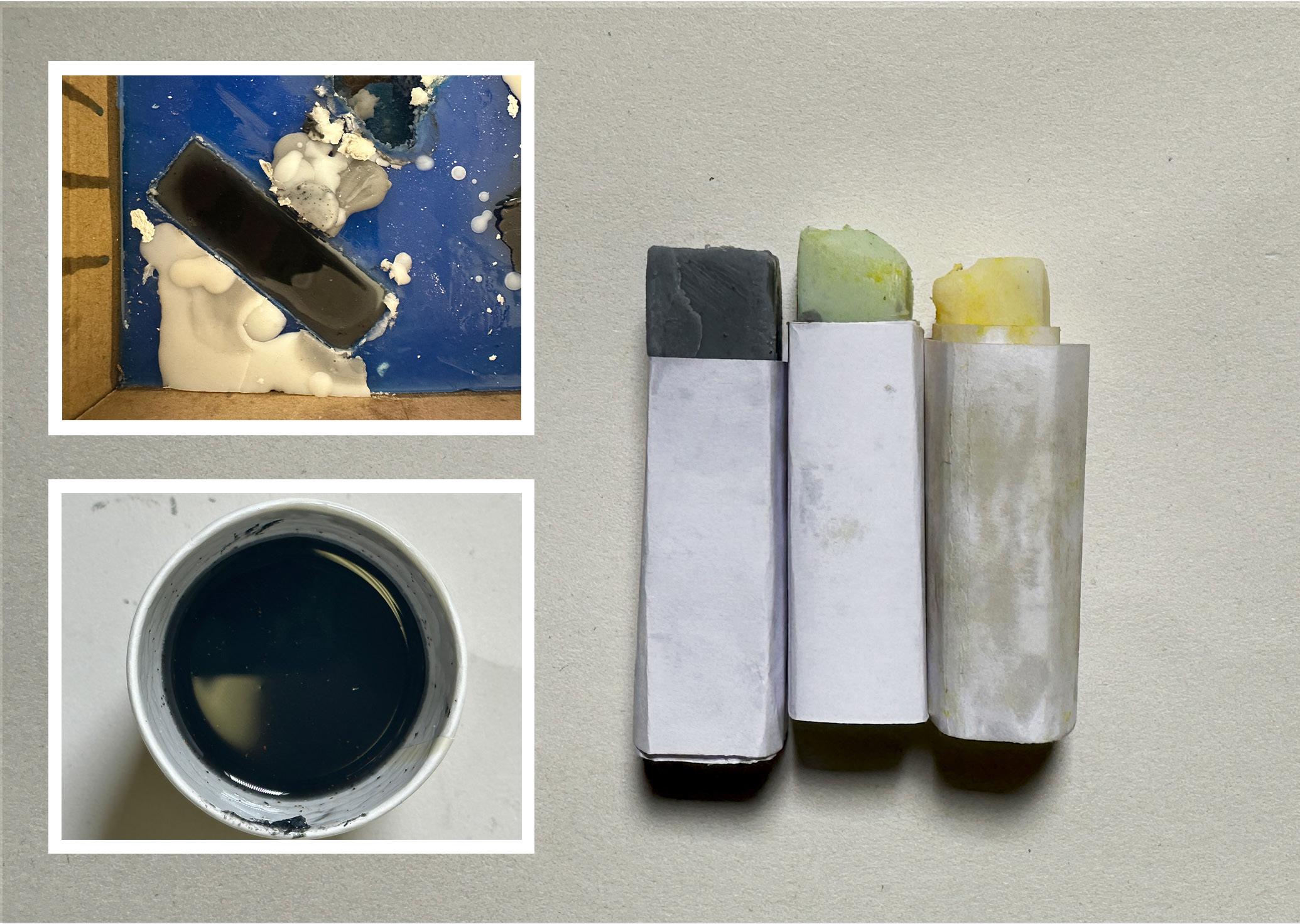

An important part of the project was to stay conscious about our decisions and the responsibility and care with which we had to work with fat. After care then became as important as the rest of the project. Since we used drawing as a way to understand land and fat, and used wax in some of the rocks, making fat pastels seemed like the most effective way to address the concerns of waste. Not just waste, but of use, function and form. We used wood and silicone moulds to build cuboids . The shape had to be big enough to rest in our entire palm for large drawings. since fat is almost translucent, a thicker pastel gets more pigment on the surface to give better information. and the fat pastels that were the result were a part of our performance called If It Jiggles.

33

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Chicago. Butler, Octavia E. Parable of the Sower. New York :Four Walls Eight Win dows, 1993.

2. Dunne, Anothony , and Fiona Raby. 2014. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

3. Steen, Marc. “Co-Design as a Process of Joint Inquiry and Imagination.” Design Issues 29, no. Spring 2013 (2013): 16-28. Accessed March 1, 2023.

4. Suquet, Annie. “Archaic Thought and Ritual in the Work of Joseph Beuys.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, The University of Chicago Press on Behalf of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, no. Autumn, 1995 (1995): 148-162. Accessed February 25, 2023.

5. Kojevnikov, Alexei . “David Bohm and Collective Movement.” Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 33, no. no. 01 (2002): 161-192. Accessed March 1, 2023.

6. Krauss, Rosalind. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences, The MIT Press 8, no. no. 01 (1979): 30-44. Accessed February 3, 2018.

7. Eames, Charles , and Kees Boeke, directors. Powers of Ten. Eames Office, 1977.

8. Kamen, Rebecca. 2020. The Extraordinary Partnerships. Lever Press.

35