4 minute read

Our Legacy of Scholarship

Scholarship Scholarship Our Legacy of

By Dr. James Watson

Advertisement

The idea of a “Christian liberal arts university” may, at first blush, seem like an inherent contradiction. In fact, when I was first asked to write this brief reflection on the legacy of scholarship at NCU, a friend asked me whether it wouldn’t be wiser to avoid the term “liberal arts” altogether, for fear that some readers might take it amiss. Of course, I hold our readership in higher regard than that, and so let me begin by saying it flatly:

Northwest Christian University is a Christian liberal arts university—and that is precisely what she ought to be.

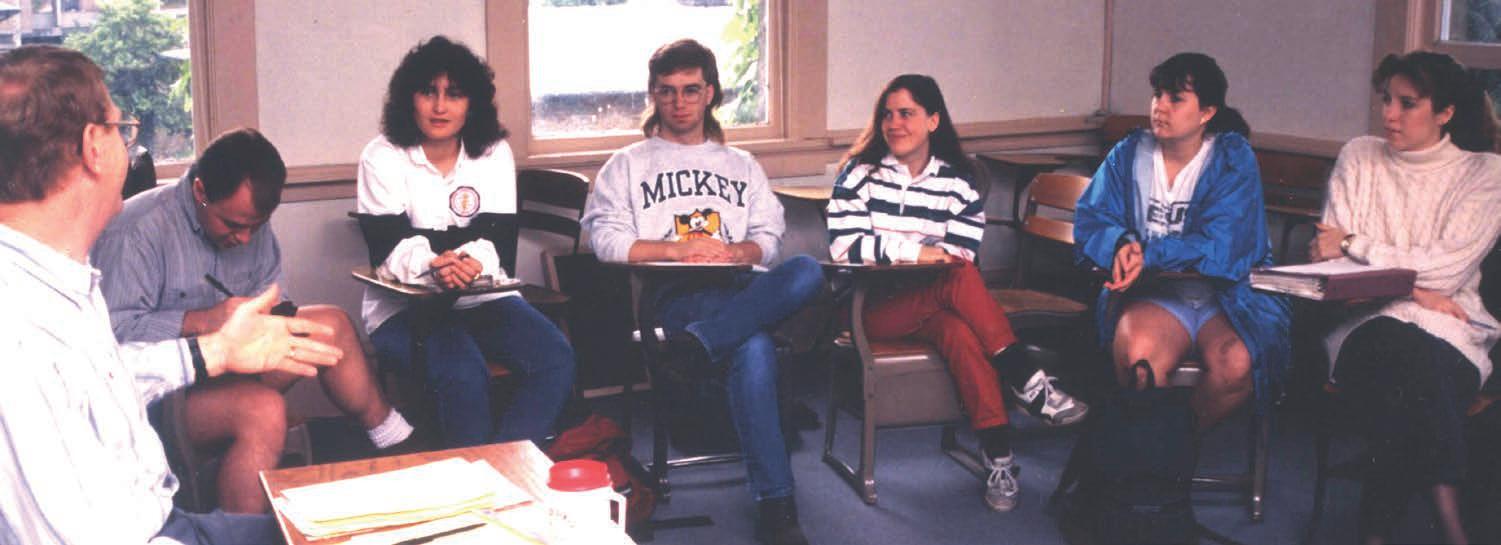

During the first week of my freshman writing and research classes, I write the words “liberal arts” on the whiteboard, and then ask the students to define them for me. Sharp as the students are, I’m usually met by an uncertain silence. The confusion stems from a mis-parsing of the phrase itself, which, etymologically, has nothing to do with the modern connotations of either “liberal” or “art.” And so I begin to trace the history of the phrase on the board: “ artes liberales” comes into English from the medieval Latin, and refers to the seven branches of study that made up all of classical education (no “hard” versus “soft sciences” dichotomy here).

The real revelation, though, is that the word “liberales” does not describe the artes (studies, skills) at all, but rather the nature of the scholars themselves who are undergoing the task of acquiring them—that is, free persons. And so “liberal arts” actually means “the studies befitting a free person.” A slave or serf had no need of knowledge beyond basic mechanical utility. As I remind the students, they are by definition “free

persons” (whether they feel like it or not) simply by virtue of having been granted the historically rare privilege of pursuing knowledge at a university. And thus in our writing classes, we begin our apprenticeship in “rhetoric” with an awareness of the mantle of responsibility attendant to this privilege.

But this does not remove the question: how can a Christian—purportedly concerned with things “not of this world”—spend her time pursuing truth and beauty for their own sakes, when there is so much “practical” work to be done?

This tension is not new. The leaders of the Stone Campbell Movement out of which our university was birthed wrestled with the same questions. The very cornerstone of their ideology was a rejection of ecclesiastical complexity in favor of “getting back to the basics” as they saw them. “No creed but Christ; no book but the Bible” was their battle cry. We can hear an echo of this in today’s various evangelical philosophies. This outlook would seem to preclude much in the way of university study. However, both Barton Stone and Alexander Campbell did value

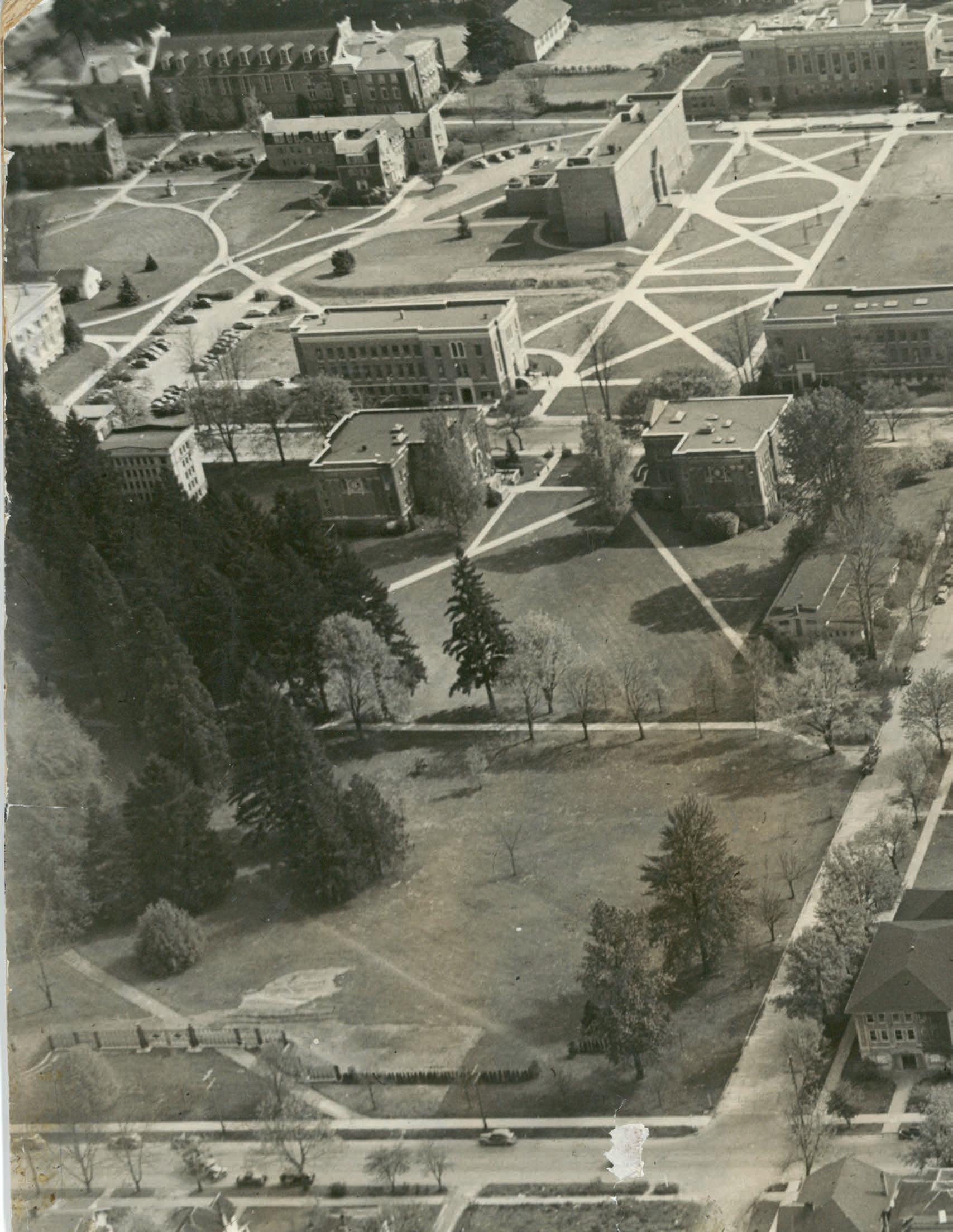

education, influencing Eugene Sanderson and James Bushnell to found Eugene Divinity School, intentionally locating it across the street from the University of Oregon in order to benefit from its robust liberal arts resources. How are we to reconcile these dynamics?

St. Augustine wrote that “a person who is a good and true Christian should realize that truth belongs to his Lord, wherever it is found.” The upshot, if we are to believe this, is that we may dive unafraid into the ocean of truth—that we may truly “be in the world,” as Christ commanded—knowing that there is no back alley of truth we may find that, rightly understood, would not be a facet of Truth itself. Scripture bears this out emphatically; the very nature of the Incarnation demands that it be so—Christ being “the radiance of [God’s] glory and the exact representation of His nature,” and the one who “upholds all things by the word of His power.” It is in the light

of this freedom that Christian scholarship has always thrived.

True inquiry, humbly undertaken, leads not away from Christ but towards him. This is why so many professors over the past hundred and twenty-five years have spent decades laboring on the corner of 11th and Alder. A Christian university affords a truly unique environment for learning—one that transcends the function of a Bible college or seminary. And so these teachers have sought to throw open the rooftops over their classrooms, pointing out the brilliance and grandeur of God’s green earth, whether by means of theology or geology; economics, philosophy or literature. Names such as Herb Works, Song Nai Rhee, George Knox, Michael Kennedy, and Anne Maggs still reverberate through the lives of countless students who have gone on to change the world while living out their vocation. In my first four years at NCU, I have seen this faith in God’s presence in the world vindicated in my classrooms. I am content that unearthing the small truth in a particular literary text, or getting at a shade of meaning in a poem, or grappling with just how a novel achieves its beauty, are in themselves enough. And it is from this place of resting in Christ’s immanence that the larger conversations do in fact arise, naturally, and with a groundedness that they would not otherwise have had.

C.S. Lewis famously has his Professor in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe ask the children in dismay, “Don’t they teach logic in the schools anymore?” This, of course, is why the world needs the “artes liberales” perhaps more than ever—civilization depends upon leaders who have learned how to think before deciding what to think. But we who are Christians need the liberal arts even more desperately: for they are the birthright of those who have found joy in the Truth.