CIRQUE

A Literary Journal for the North Pacific Rim

Volume 13, No. 2

Anchorage, Alaska

© 2023 by Sandra Kleven & Mike Burwell, Editors

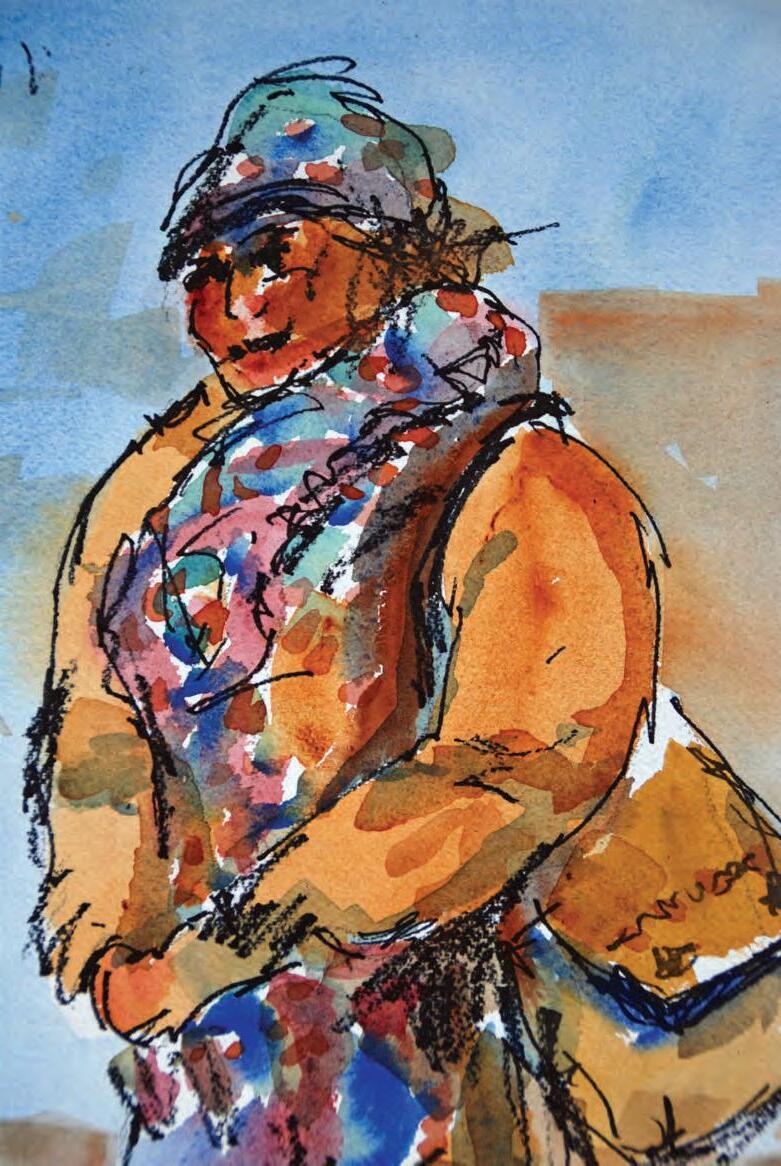

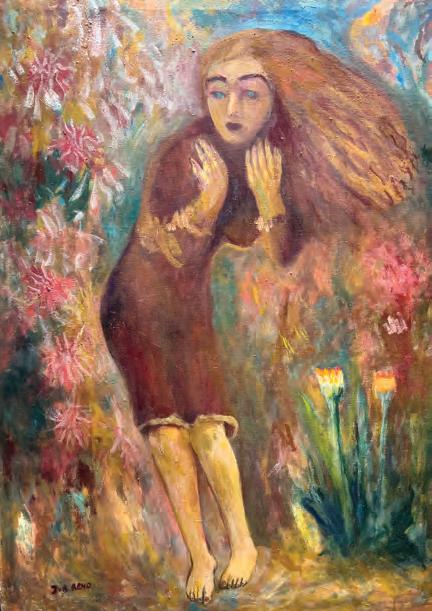

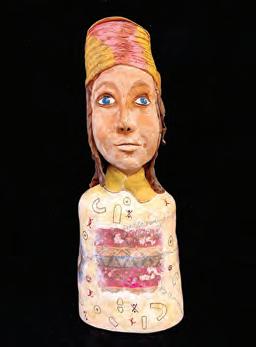

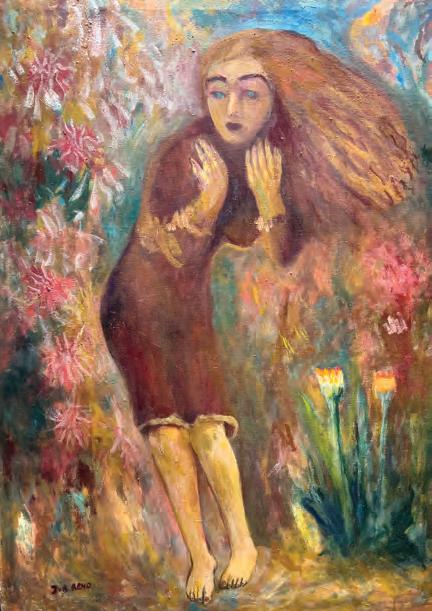

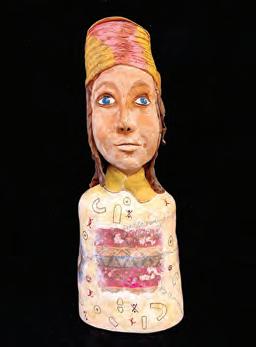

Cover Art: Elizabeth Belanger, "Sarah" Table of Contents Photo Credit: John Coyne, "Yukon" Design and composition: Signe Nichols

ISBN: 9798862101331

Independently Published Published by Anchorage, Alaska www.cirquejournal.com

All future rights to material published in Cirque are retained by the individual authors and artists. cirquejournal@gmail.com

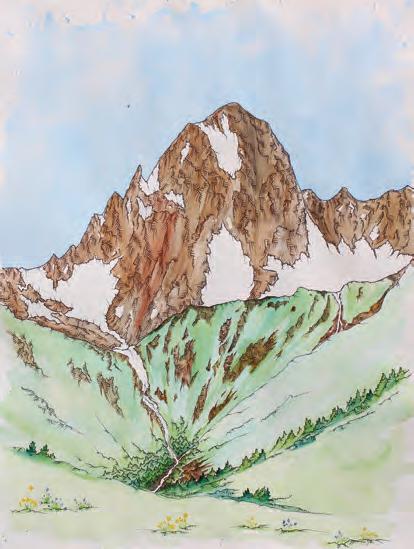

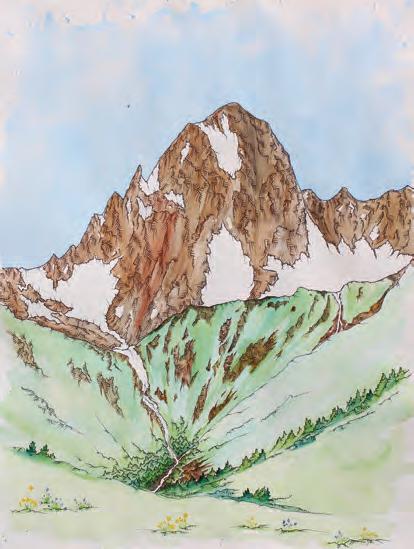

Yosemite Dawning

Poems of The sierra Nevada

By shauNa PoTocky

By shauNa PoTocky

Shauna Potocky’s debut book of poetry takes us from the edge of the Central Valley, California with its wildlife refuges and agricultural fields, through foothills and into the realm of summits within the Sierra Nevada, including colorful and scent-filled meanderings on the Eastside of this spectacular range. It is a journey of landscapes and time—cultural connections, histories, climbing and contemporary questions. The poet connects us to the unseen, to the tangible, to textures and tales, from the dusty past to today, and thoughtfully asks us how we will forge the future.

Shauna Potocky’s book calls us to join her travels through public lands that await us, know us and are part of us—trails, crevices, rivers, animals and mountain peaks. The fauna and the flora in each poem are a discovery, a relationship, a new life and an enlightenment. You will breathe deeply as you trek through her poems and drawings. You will become part of the earth’s true life, you will want to leave behind the manufactured freeze-dried urban-scapes. You will be at peace. Every poem is a new height, an unexpected vista, proof of her deep knowledge and love for the environment and its wiggly lives and grand miracles. The poems and drawings, the trails and compassion all lead us to a magnificent dawn indeed. This is a most necessary collection and a sure prize-winner.

—Juan

Felipe Herrera, Poet Laureate of the United States, Emeritus

Shauna Potocky has a deep love of high peaks, jagged ridgelines and ice. Her poetry reflects a remarkable connection to the natural world and her writings have appeared in a variety of publications and journals both at home and internationally. Her forthcoming book of poetry Sea Smoke, Spindrift and Other Spells is scheduled to be published by Cirque Press. Shauna Potocky is a poet and painter who lives in Seward, Alaska located within the traditional homelands of the Sugpiaq people.

Yosemite Dawning is an epic love poem for Yosemite National Park. These are not sentimental lines but rather a caretaker’s loving astonishment of Nature with one eye towards environmental despair and the other towards hope. The poet finds a legacy among the park’s jagged peaks: “Every route, they say, is a signature line.”

—Tawhida Tanya Evanson, author of Book of Wings

Map and Interior Images by

by Penny Otwell

Published By:

January 2023

$18 on Amazon

In the Winter of the Orange Snow

In the Winter of the Orange Snow captures a era of freewheeling adventure in southwest curiosity and courage, and the phrase “only in Bethel” was coined in response to events

Diane Carpenter captures the spirit, the oddities, the bizarreness of characters and happenings, as well the unique and beautiful environment and indigenous people of the Kuskokwim. She does so with humor, sensitivity, and clear recollections. It’s a tough land. One cannot help but greatly admire this woman. No tourists here in Bethel, Alaska, where primitive ways became modern times in the span of a lifetime.

Sky

Changes on the Kuskokwim

Diane Carpenter’s book is a delightful tramp through the Alaska bush country in the 1950s and sixties through the eyes of a great storyteller. The tales are sobering, hilarious and very informative, each a window into the details of the storyteller’s life and times. For many Alaskans, the book will be nostalgic. For others, it will bridge the gap between those who live on the road system and the bush. For readers in the Lower 48 states, this book will be an astounding ride on boats, airplanes, and dog-sleds through the

James H. Barker, author of Always Getting Ready / Upterrlainarluta: Yup’ik

–

She was a state delegate to the National Women’s Conference in Houston and lead organizer of the Alaska Village Electric Cooperative (AVEC). She taught in public schools and the local college. As she approached retirement, she set up the Pacifica Institute, a non-profit educational organization that developed many innovative programs. In 2007, Diane retired and moved from Bethel to the historic town of Alamos, Sonora, where she renovated a 250-year-old villa. She recently celebrated her 90th birthday there.

$20

Available on

Infinite Meditations

Kleven Michael Burwell Editors & Publishers

Kleven Michael Burwell Editors & Publishers

About the Author

Sue Lium (nee Robinson) was born and raised in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. She moved to Alaska a er graduating nursing school from the Misericordia Hospital in Edmonton, Alberta and worked for the U.S. Public Health Service in hospitals in Kotzebue and Barrow. A er leaving the Arctic, she worked at Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara, California before marrying and returning to Alaska. She retired a er working thirty years at Bartlett Regional Hospital in Juneau, Alaska. Now widowed, she is the mother of two boys and grandmother to ve grandchildren. She can be reached at suelium@hotmail.com.

About Mail Order Nurse

is is the lively memoir of a young, city-bred nurse who ew to Kotzebue for her rst job in 1969. It is an engaging read about ingenuity in medical care, the author’s fascination with the land and her crosscultural pleasures and mishaps. e book covers the rst two years of her nursing career, including time in Barrow [Utqiavik]. It bene ts from the author’s photos and from her current perspective as a longtime Alaska nurse. Highly recommended for readers interested in Alaska history, medicine, and memoir.

—Sarah Crawford Isto, MD, author of e Fur Farms of Alaska: Two Centuries of History and a Forgotten Stampede and Good Company: A Mining Family in Fairbanks, Alaska

Settle in for a fascinating tour of a culture on the edge of the world, the Inupiat people of Northwest Alaska. Join Sue in fun activities from partaking in a caribou hunt, to racing across the sea ice behind a dog team, to learning cultural di erences like why the Inupiat never say goodbye. Sue also shows us another side of life in this remote region, from struggles with alcohol, to culture shock to murder.

—Stan Jones, author of e Nathan Active Arctic mysteries

Sandra

Sandra

❅ ❅ ❅ ❅

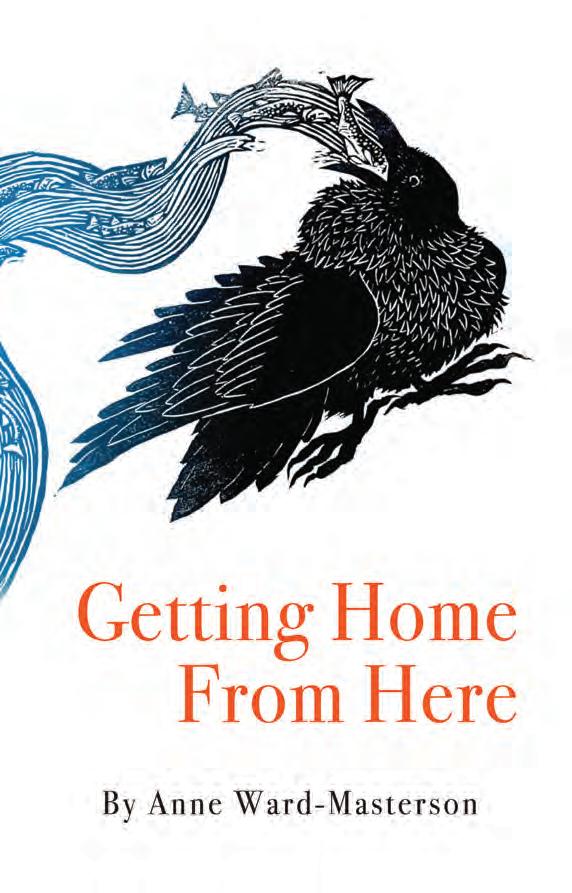

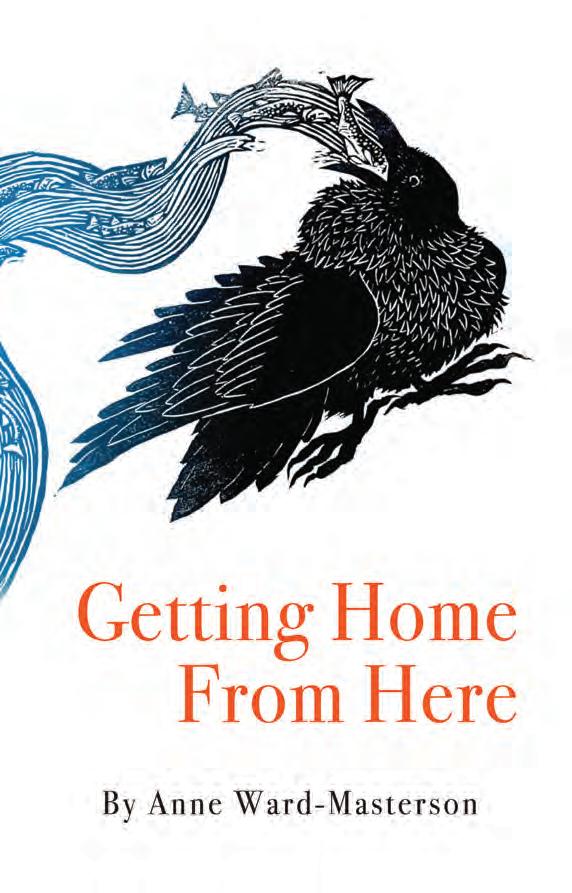

Getting Home From Here o ers forty-seven stunning, thought-provoking poems covering a woman’s life whose personal history re ects much of the ethnic complexity, familial joys/sorrows, social strains, and natural beauty of the U.S. Anne Ward-Masterson writes of her New Hampshire girlhood, Wading into cool water/ sinking soft sediment of the river bed oozes/sucking at our toes. And of Alaska, her home now, Spring cries storms against/My window all through twilight/Sunrise brings damp calm. She also calls out the racist history of the U.S. which foisted shame and confusion upon her mixed-race childhood, but is now a source of pride. An inspiring and compelling read.

—Kerry Dean Feldman, author of Alice’s Trading Post: A Novel of the West, and poems in e Woman Within: Memory as Muse

Anne Ward-Masterson grew up in New Hampshire in the tame woods, shing, canoeing and swimming in the Lamprey River and reading books on cold rainy days. Attending Brandeis University and later marrying into the USAF gave her a broader view of people, religions and food. She currently resides in Eagle River, Alaska, where there are no tame rivers or woods.

In Getting Home from Here, especially her poems about race, Ward-Masterson calls out schools, the military, and people who make assumptions about her. She questions how people perceive blackness (“why won’t I tone it down?”). She describes the cab of a pickup truck or a riverbed with equal clarity through sensory language. Her natural, occasional rhyme threads a consistent, melodic quality through several moments of soft, poignant sadness. A rewarding read.

—Cynthia Steele

Sandra Kleven Michael Burwell Editors & Publishers

Sandra Kleven Michael Burwell Editors & Publishers

BOOKS FROM CIRQUE PRESS

Apportioning the Light by Karen Tschannen (2018)

The Lure of Impermanence by Carey Taylor (2018)

Echolocation by Kristin Berger (2018)

Like Painted Kites & Collected Works by Clifton Bates (2019)

Athabaskan Fractal: Poems of the Far North by Karla Linn Merrifield (2019)

Holy Ghost Town by Tim Sherry (2019)

Drunk on Love: Twelve Stories to Savor Responsibly by Kerry Dean Feldman (2019)

Wide Open Eyes: Surfacing from Vietnam by Paul Kirk Haeder (2020)

Silty Water People by Vivian Faith Prescott (2020)

Life Revised by Leah Stenson (2020)

Oasis Earth: Planet in Peril by Rick Steiner (2020)

The Way to Gaamaak Cove by Doug Pope (2020)

Loggers Don’t Make Love by Dave Rowan (2020)

The Dream That Is Childhood by Sandra Wassilie (2020)

Seward Soundboard by Sean Ulman (2020)

The Fox Boy by Gretchen Brinck (2021)

Lily Is Leaving: Poems by Leslie Ann Fried (2021)

One Headlight by Matt Caprioli (2021)

November Reconsidered by Marc Janssen (2021)

Callie Comes of Age by Dale Champlin (2021)

Someday I’ll Miss This Place Too by Dan Branch (2021)

Out There In The Out There by Jerry McDonnell (2021)

Fish the Dead Water Hard by Eric Heyne (2021)

Salt & Roses by Buffy McKay (2022)

Growing Older In This Place: A Life in Alaska’s Rainforest by Margo Wasserman Waring (2022)

Kettle Dance: A Big Sky Murder by Kerry Dean Feldman (2022)

Nothing Got Broke by Larry F. Slonaker (2022)

On the Beach: Poems 2016 -2021 by Alan Weltzien (2022)

Sky Changes on the Kuskokwim by Clifton Bates (2022)

Transplanted: A Memoir by Birgit Lennertz Sarrimanolis (2022)

Between Promise and Sadness by Joanne Townsend (2022)

Yosemite Dawning by Shauna Potocky (2023)

The Woman Within by Tami Phelps and Kerry Dean Feldman (2023)

In the Winter of the Orange Snow by Diane S. Carpenter (2023)

Mail Order Nurse by Sue Lium (2023)

Infinite Meditations: For Inspiration and Daily Practice by Scott Hanson (2023)

All in Due Time by Kate Troll (2023)

Getting Home from Here by Anne Ward-Masterson (2023)

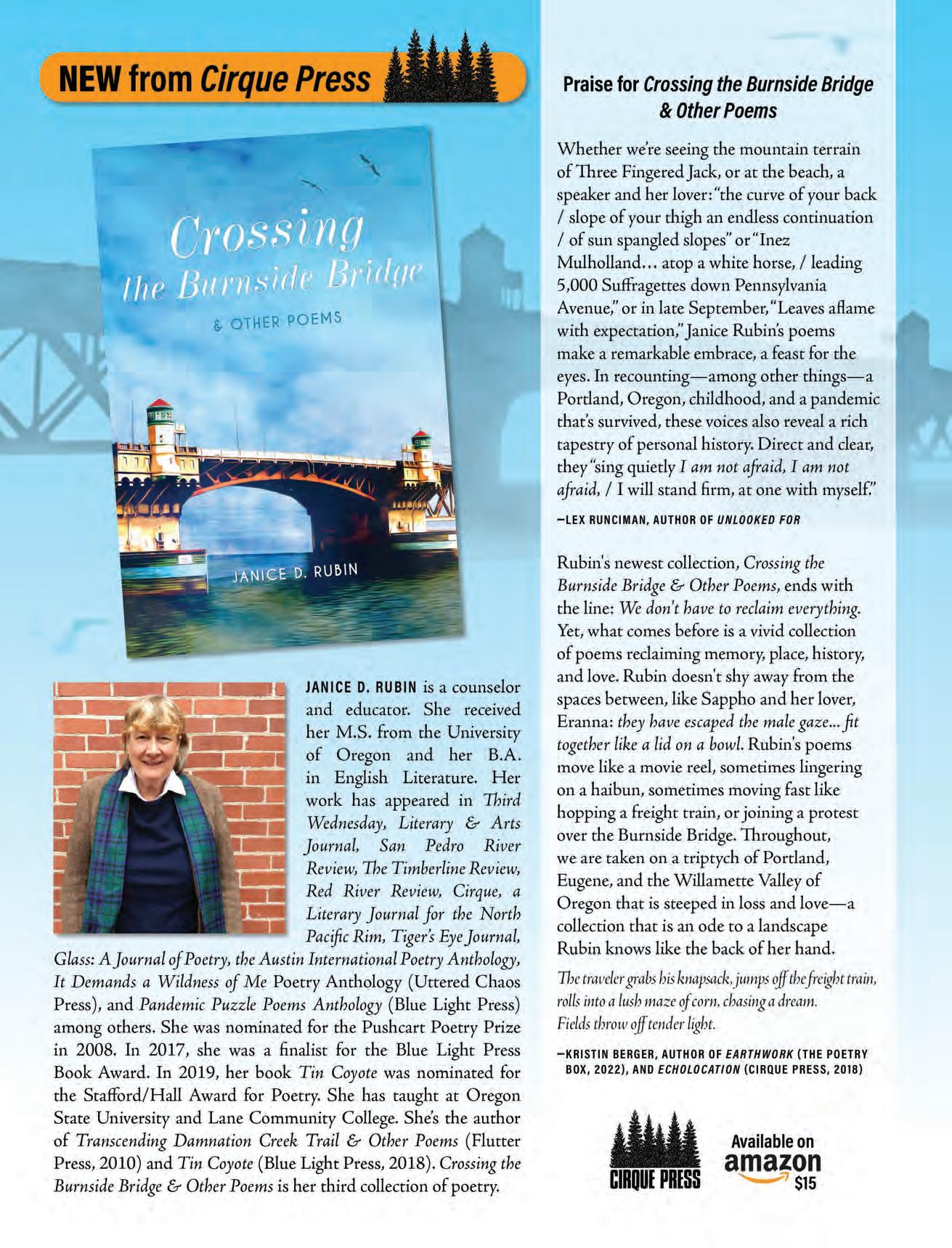

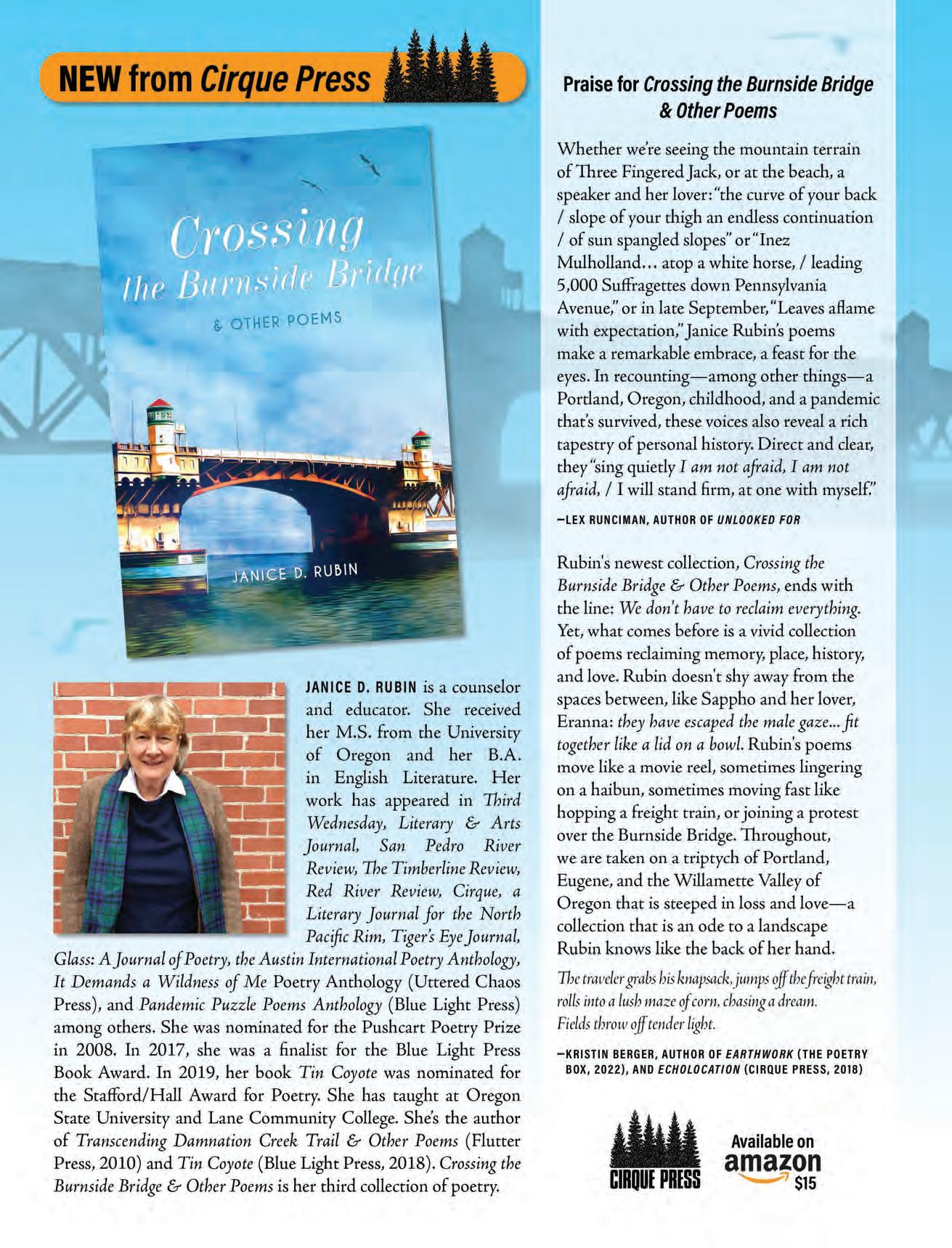

Crossing the Burnside Bridge by Janice D. Rubin (2023)

May the Owl Call Again: A Return to Poet John Meade Haines, 1924 -2011 by Rachel Epstein (2023)

CIRCLES Illustrated books from Cirque Press

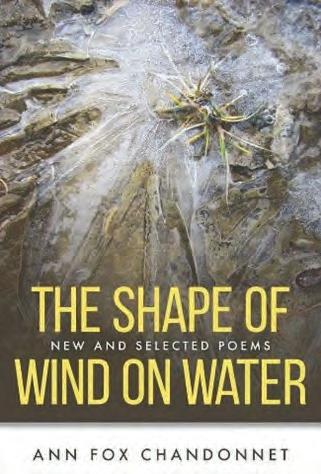

Baby Abe: A Lullaby for Lincoln by Ann Chandonnet (2021)

Miss Tami, Is Today Tomorrow? by Tami Phelps (2021)

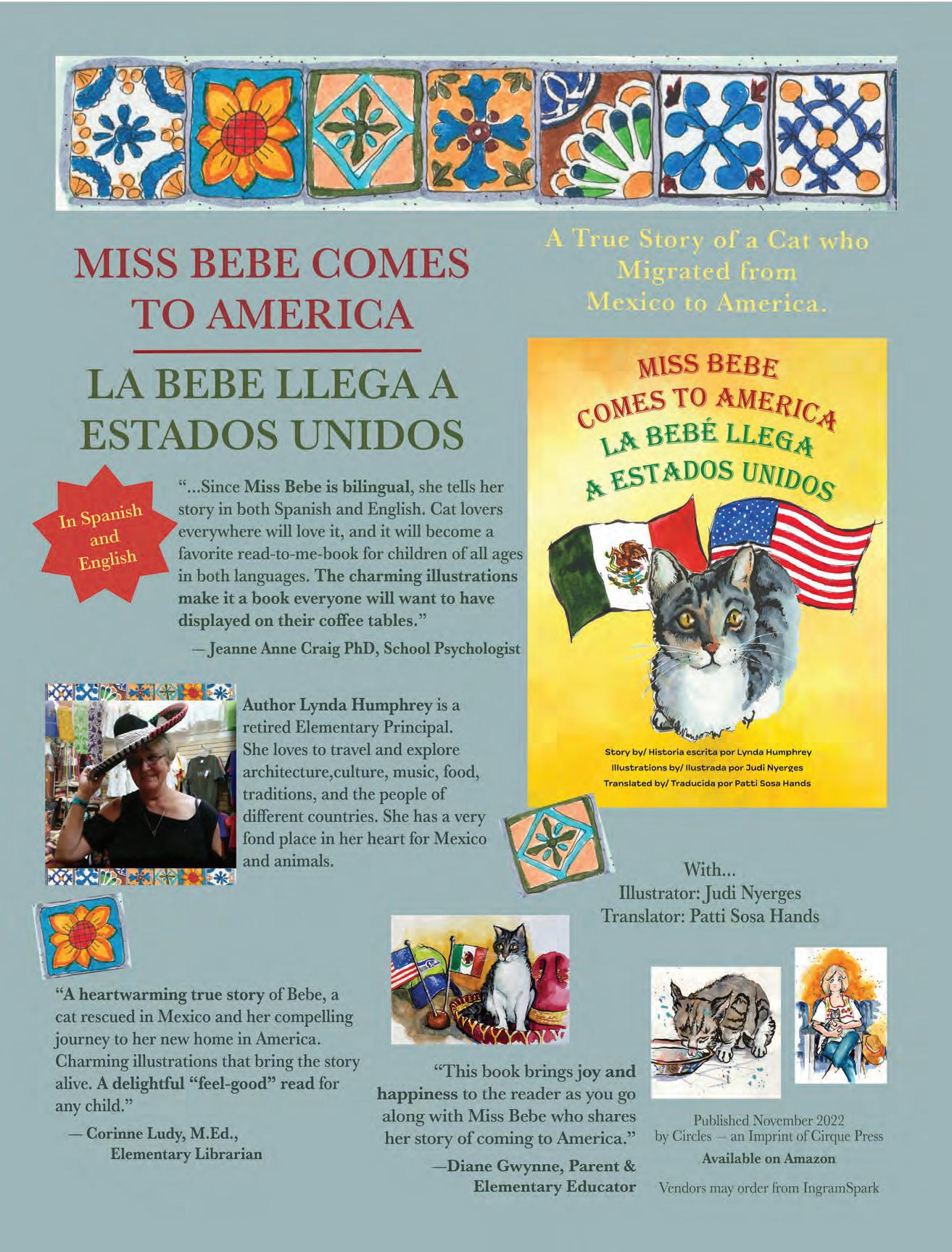

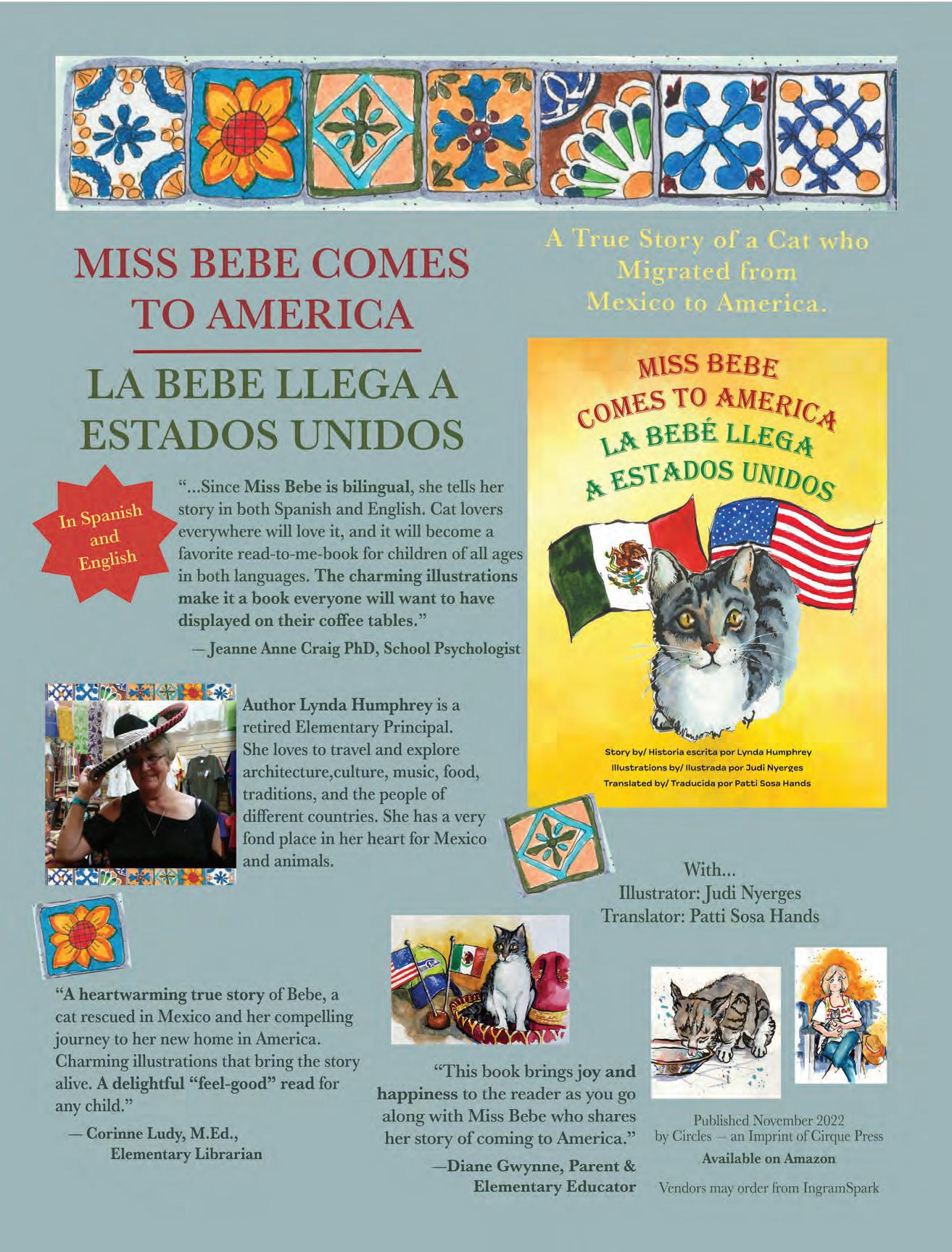

Miss Bebe Comes to America by Lynda Humphrey (2022 )

Order via Amazon or your local bookstore. Venders may order from Ingram or via email to cirquejournal@gmail.com

Keeping Up Jim Thiele

From the Editors

Celebrating the Literary Bio: a paragraph you write in 3rd person making yourself look good

We are embarking on the Cirque Press Book Tour of 2023. Five events are set and the first one is tonight in Bellingham. I have been wrangling bios all week, seeking updates from those set to read. It’s a hassle, especially when fresh printed lists are in hand and an email arrives with a missed update. I correct the master and print again, only to get an email from another reader, delighted to join us. Sure, please send your bio.

This effort assures that everyone knows who’s who. There are few places where you get a brief synopsis of those sharing your space. It doesn't happen at the beach. It doesn't happen at lunch (not in a box, not with a fox). You don’t get this info at a reception where you can make the social error of asking what someone does for a living. Or to avoid talking work, you look for something handy to explore, like “Have you seen any good movies lately? Barbie? Oppenheimer?” No winning entry here.

When we conduct book launches, soirees, and poetry readings, the literary bios we place in your hand help with our central goal of building the literary community. We don’t read them aloud when introducing readers because they sound too similar. They can put you to sleep even when detailing great accomplishment. Held in hand, though, like a Tesla “Easter egg” they offer a bright surprise and shortcut the getting-to-know you process. Like the writers and artists detailed in the concluding pages of this issue, those we feature are the literary lights of Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, honoring Cirque with writing and images. Check out the bios. Great folks there. Get to know them.

Find Inside

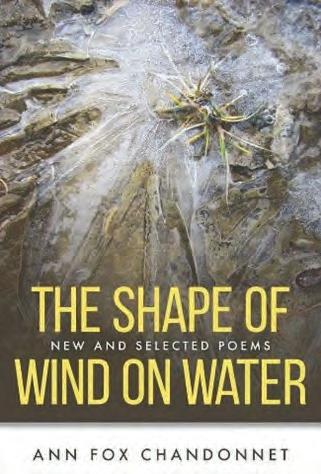

Inside you will find coverage of the Cirque AWP experience and associated readings by Cynthia Steele. Paul Haeder has reviewed The Shape of Wind on Water by Anne Chandonnet. Sandy Kleven interviews Diane Carpenter about her new Cirque Press book In the Winter of the Orange Snow. We continue our feature about the artists of Cirque with Cynthia Steele’s interview with photographer Jim Thiele. Jim has provided us with art for almost every issue of Cirque and many covers. See, too, full page ads for new books from the busy world of Cirque Press.

Sad to Note

We sadly acknowledge the passing of Kathleen Smith a poet published many times in Cirque. From Cirque 10.1, we have these lines by Kathleen. “Time changed the morning I met the moose…Just as I came around the small dunes…her eyes met mine. When I saw the calf, I knew that she would kill me if she had to though she wished me no harm. She looked me straight in the eye, passed on the primal message: all is as it should be. Death need not carry meaning in the wild.”

Cirque: A Literary Journal for the North Pacific Rims

Sandra Kleven and Mike Burwell, Editors

Cynthia Steele, Associate Editor

Paul K. Haeder, Projects Editor

Signe Nichols, Designer

Published twice yearly near the Winter and Summer Solstice

Anchorage, Alaska

Our mission: to build a literary community and memorialize writers, poets and artists of the region.

Our thoughts are with the people of Maui in the aftermath of 2023’s catastrophic fire and the terror filled flight toward safety.

15 Vol. 13 No. 2

Maui Fire

Joe Reno

CIRQUE A Literary Journal for the North Pacific Rim

Volume 13, No. 2

POETRY CONTEST

Vivian Faith Prescott Journeying with Poems of Place 18

Contest Winners 19-20

Finalists 20-35

NONFICTION

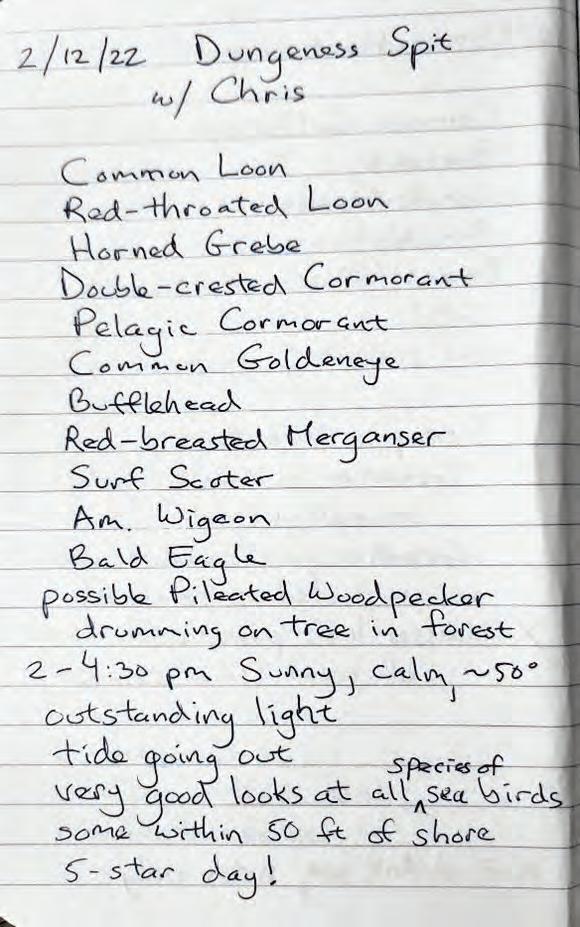

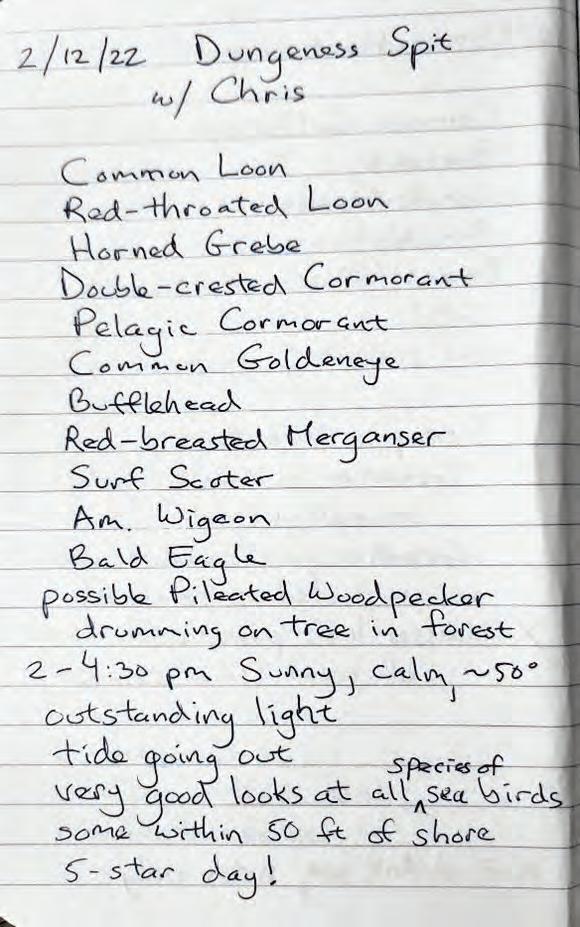

Francis Opila Refuge at Dungeness Spit 37

Connie Feutz All Because of Errol 39

Lisa K. Harris Spastic Dog Woman 43

FICTION

Joe Aultman-Moore Forest Notes 49

Ben Kuntz The Springs of Life 50

Jack Cubria In the Torkel 55

PLAY

Kemuel DeMoville On the Crest of the Wave in the Sea of the Dead 60

POETRY

Luther Allen mary oliver died yesterday 71

Alexandra Ellen Appel My Garden 72

Jennifer Bisbing Release the Hammer, Put Down the Weapon 72

Kristina Boratino Mississippi Cypress 73

Wendy Brooker The Inspiration Cycle 73

Randol Bruns Lace Patterns in The Sand 74

Cindy Buchanan Between the Lines 74 How to Pronounce Grief 75

Abigail Calkin Fog 75

Margaret Chula Potholder 76

Nard Claar Place 77

I.M. Cordova When your tía who’s not your tía has had one too many modelos 78

Mary Eliza Crane After the Bolt Creek Fire 79

Chris Dahl The Stream Beneath Us 79

Nancy Deschu Ephemeral 80

Ann Dixon Scenes from a Wet Life 80

Amelia Díaz Ettinger Siletz River Pantoum 82

Leslie Fried History Lesson 82

Christien Gholson Bees, Faeries, Souls of the Dead, Maitake Mushrooms: how the world was made 84

David A. Goodrum What We Bring to the Ocean 85

Jim Hanlen Between the Creases 86

Scott Hanson A Middle-Aged Love Story in Haiku 86

Lesley Rogers Hobbs My Son’s Namesake 87

Brenda Jaeger My Response to Lorca’s Question in My Dream 88

Marc Janssen The Clock Has Lost Its Way In The Sisyphean Night 88

Jaqualyn Johnson Slaughterhouse 90

Susan Johnson This Fourth of July 90

John Kooistra I Love This House 91

Gary Lark Hannah's Berry Patch 92

Eric le Fatte Steady State 93

Linda Lucky Love Of A Booth 93

M.C. MoHagani Magnetek Falling Star, Make a Wish Gumbo 94

David Mampel When all else fails 94

Malia Maxwell Side Effects 95

David McElroy In Which Mrs. Freizinger and Louie Adams Are Revealed 95

DC McKenzie Untitled Poem no. 238 96

Karla Linn Merrifield Litany of That Time of Year in Kent, NY 97

Al Nyhart Montana Barn 98

Mercedes O’Leary Together We Break Coffee Pots 98

Francis Opila High Desert Rendezvous 99

Shauna Potocky This Clay Earth 99

Diane Ray Pumpkin Alchemy 100

Bethany Reid In the Beginning 101

Richard Roberts The First Blizzard 101

Barbara Rockman New Year Beside The Playa 102

Lois Rosen Mrs. Cooper, 1958 103

Seth Rosenbloom Harbor 104

Ryan Scariano O Beautiful Asteroid 105

Linda Schandelmeier For Our Brittle World 106

Tom Sexton Caw 106 Quiet 106

Craig Smith The Donut 107

Leslea Smith and Bill Wuertz Fire and Ice 108

Mary Lou Spartz Wake Up Call 110

Kim Stafford The Big Empty 111

Kathleen Stancik Yellow Columbine 111

Richard Stokes Emily Wall Reads from her Breaking into Air 112

Jim Thielman Random Beauty 113

Georgia Tiffany Sheltered In Place 114 In The Night The Rain Begins 114

Lucy Tyrrell I witness 115

Devon Van Essen Symbiont 116

Anne Ward-Masterson Fire Not Kindled By Men 117

Allison Akootchook Warden Attata sets the tone 118

Patty Ware Lola 120

Sandra Wassilie Ruby Ring: Its Bond 121

Alan Weltzien Norwegian Wood 122

Robin Woolman Passing Glances 123

FEATURES

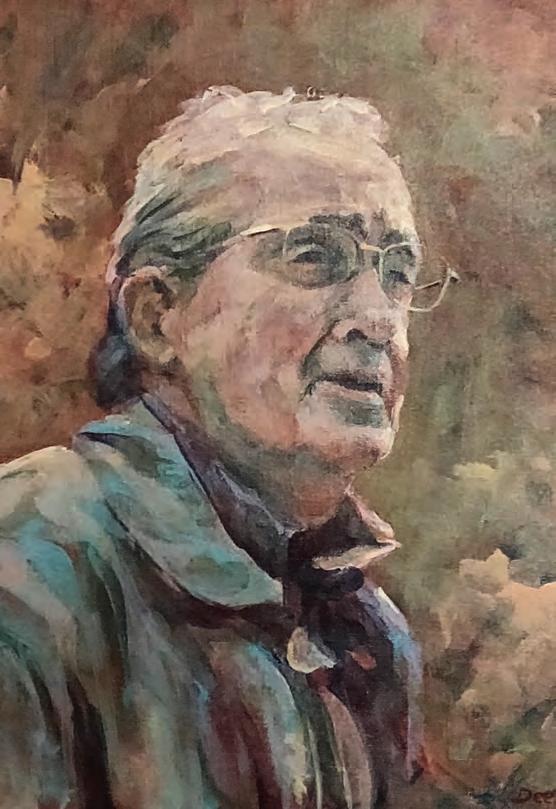

Cynthia Steele Artists of Cirque—The Camera Points Both Ways: A Profile of Jim Thiele—Photographer 127

INTERVIEW

Anne Haven McDonnell An Interview with Anne Coray—Late Fall Bucolics (The Poetry Box, 2022) 132

INTERVIEW AND REVIEW

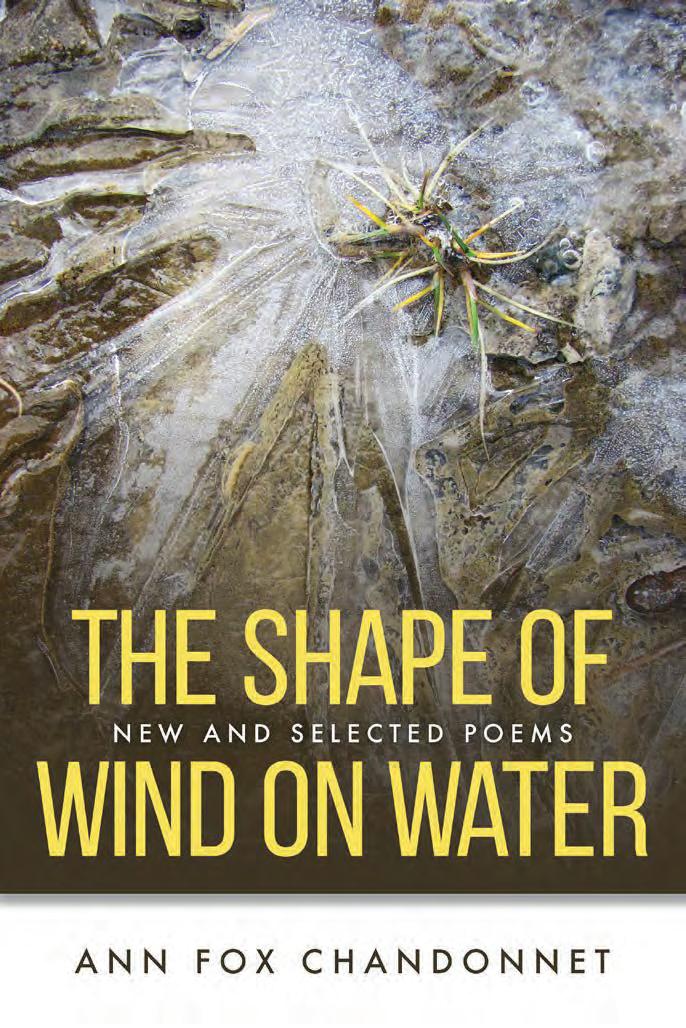

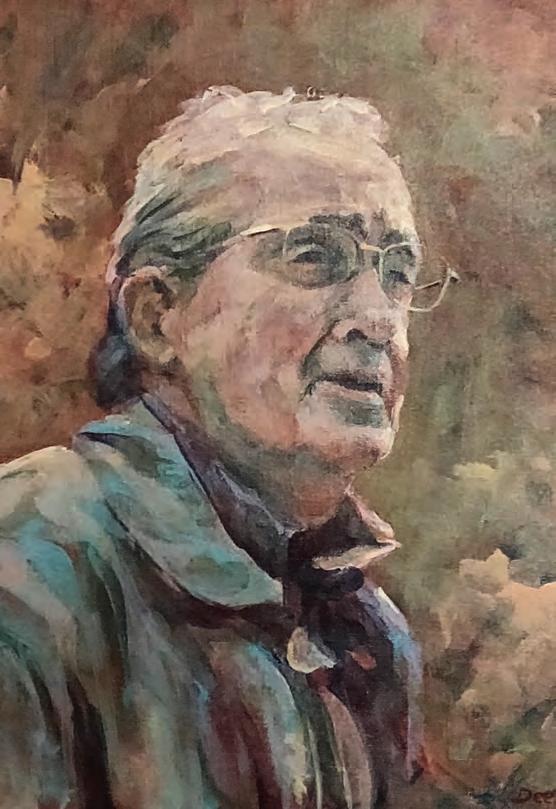

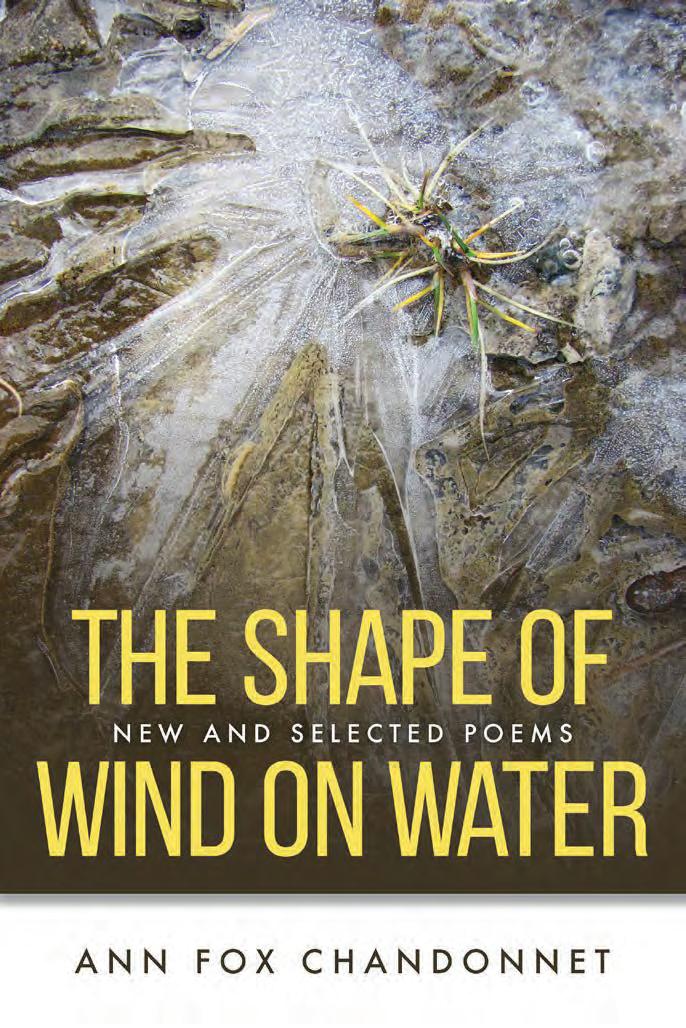

Paul K. Haeder Touching Furrows Toward Understanding a Life in Poetry— A Sandpiper on the Edge of Continents: An Interview with Ann Fox Chandonnet and a Review of Chandonnet’s The Shape of Wind on Water (Loom Press, 2023) 136

INTERVIEW

Sandra Kleven Like a Mountain, She Creates Her Own Weather System: An Interview with Diane Carpenter, author of In the Winter of the Orange Snow (Cirque Press, 2023) 143

REVIEW

Melody Wilson A Review of Bruce Parker’s Ramadan in Summer (Finishing Line Press, 2021) 147

FEATURE

Cynthia Steele AWP: Cirque Press Sparkles in the Emerald City 150

CONTRIBUTORS...154

POETRY CONTEST: POETRY OF PLACE

Vivian Faith Prescott

Vivian Faith Prescott

Journeying with Poems of Place

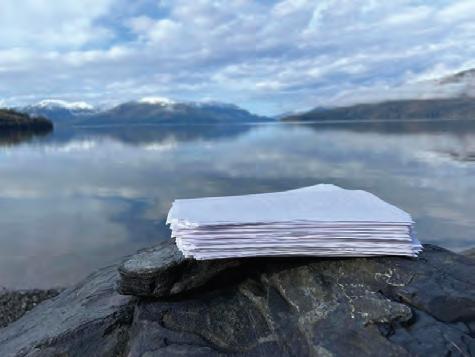

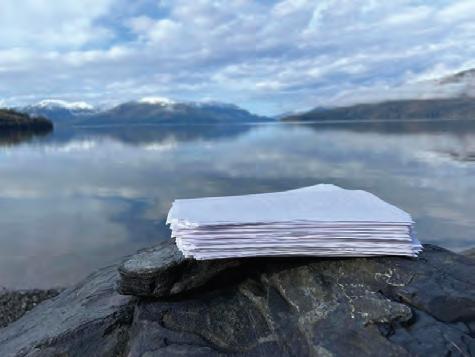

Judging this contest was difficult, but also rewarding. There were hundreds of entries! I printed out the large stack of poems, held them to my chest, and said to the universe: I’m going to take good care of these. Being a poet myself, I know each piece of paper represented a lot of hard work. It takes money, time, effort, and expectation when entering a contest.

Each morning, next to the ocean at my fishcamp, I sat with a handful of entries, drinking my coffee, and journeying with the poems. Some of the poets brought me across the country, some poets traveled to far off places, and others were musing close to home. Many of the poems explored the inside landscapes of being human within the context of place.

Over the last couple months, I read and re-read the poems. I considered how the poem made me feel, what images the poet painted, and what language and form they used. In other words, how “place” was evoked. Numerous poems stuck with me throughout the selection process, and I returned to their images and words, remembering them throughout the day. Congratulations to the three winners and all the finalists. And to those poets whose work I did not choose, I am grateful you shared your beautiful words with me. They are a part of me now. Your entries support the future work of Cirque. For sure, it was an honor to serve as a judge for this contest. Dear Readers, you will enjoy journeying with these poems as much as I did.

18 CIRQUE

Contest Winners

Jim Hanlen

West Queen Street

Ty Cobb lived across the street. That’s what his dad called him but I called him Terry, my friend. When the circus came down Queen St. we sat on the hot curb chewing tar, that the street bubbled up. The calliope swerved like the music. A sweaty man next to the ring master wore full-body, dirty white tights, his arms and chest muscles bulging. We rolled the tar into balls, then covered our two front teeth. When the clown on stilts came by, we smiled. The elephant got big, then bigger and we couldn’t see all of it at one time. What I remember most were its toenails.

Tim Barnes

Urban Renewal

I hate seeing a building torn down where I once made love Jeffrey Lane, about the Goose Hollow neighborhood

where you made love is now a place in the air, angels float there like cumulus over concrete slabs and twisted beams, sinuous now in a certain light.

The old romances are rubble, an archeologist’s dream: history, castles to cobblestones, a shadow romance leaves in the sky blue rooms where you once loved Willow, or Kathy or Paige, beautiful women, vacancies the light stalks through the cracked cement and musty secrets of basements where houses enter the ground.

The bare floors of your toe-touch groan with crowbars and sledge hammers. A wrecking ball busted through the walls that held you close. Those posters of Jimi and Che and Janis burst into dust. Every cobblestone of the castle your loves fashioned in your mind pummeled back now to gravel troubadours trudge from Carcassone to the Goose Hollow Inn.

You loved someone beautiful in rooms now deeply naked in the gaping light of concrete hunks and hulls of broken pipe, swirls of incense ash whirl away in the wind of bulldozers dizzy with dust.

19 Vol. 13 No. 2

Janet Klein

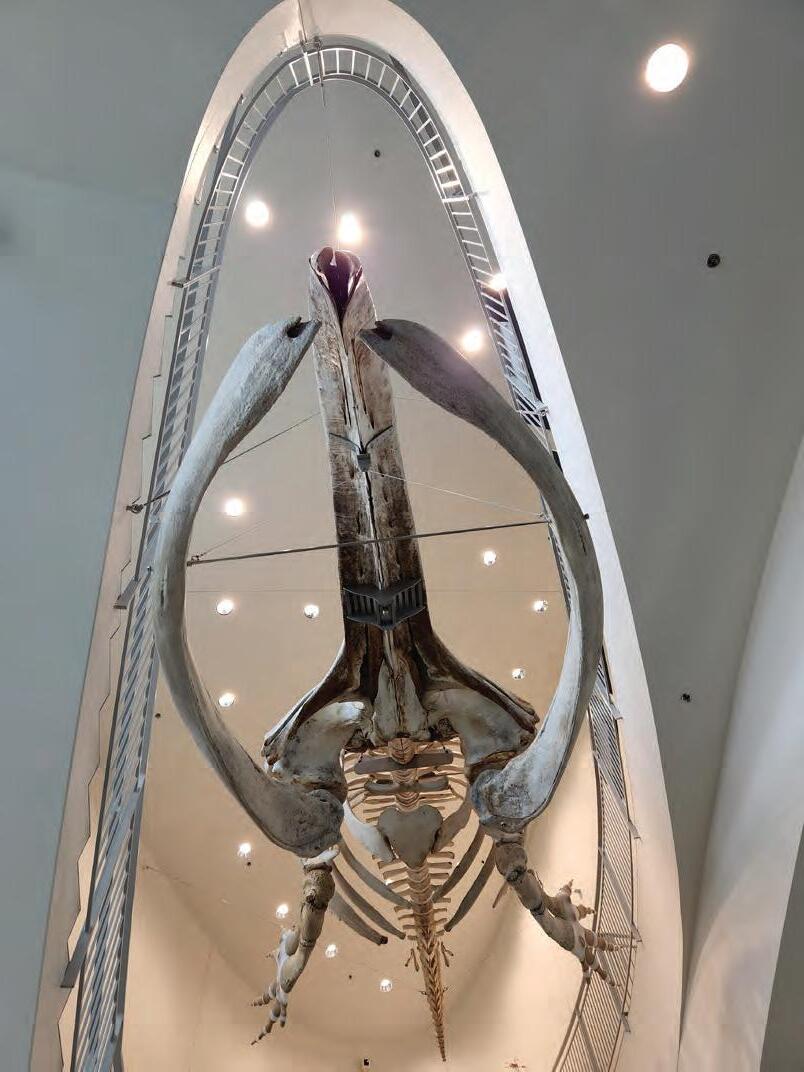

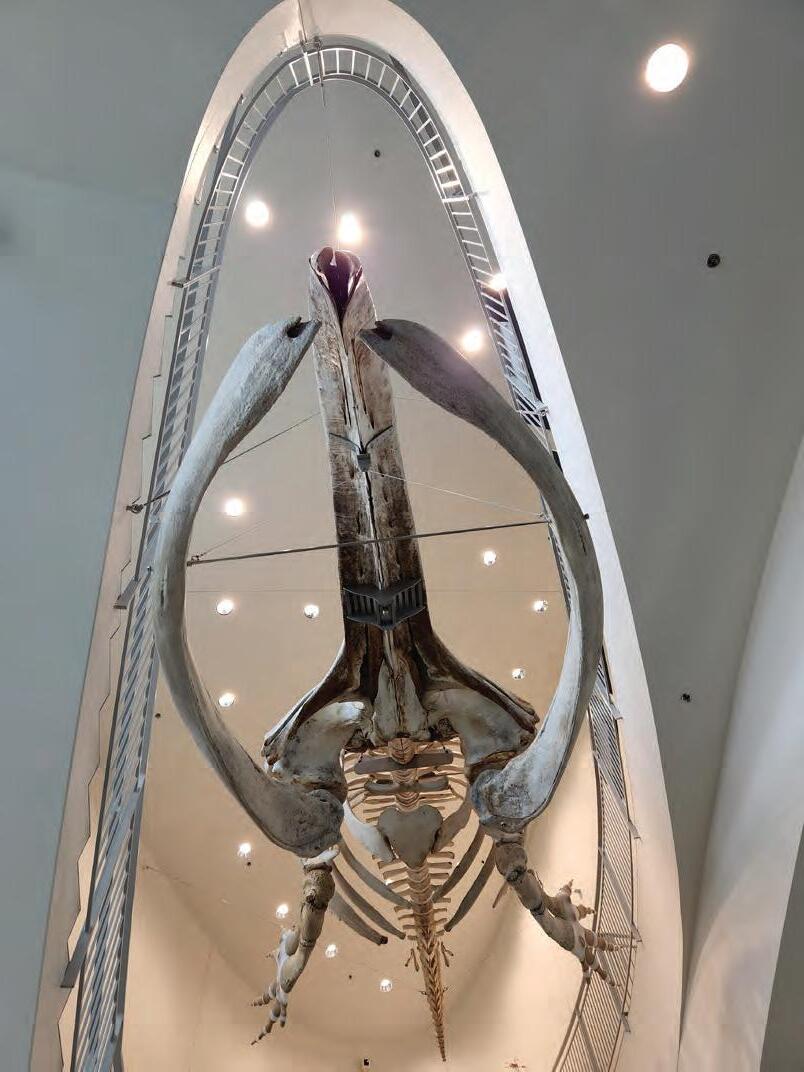

Oval within oval. Bowhead whale skeleton in lobby. University of Alaska Museum of the North

Patrick Dixon

Western Washington November

2:00 pm, dark already— thick blanket between us and the sun, fifth day in a row. This is why friends laughed when told we were moving here from Alaska twenty years ago: Get a good umbrella Why the state’s biggest music festival is called Bumbershoot Winter on the west side.

With it, depression. Lewis and Clark wintered here, named places Dismal Nitch, Cape Disappointment. My first year it rained 105 straight days. I almost slit my wrists, I tell people with a laugh, shake my head. Thing is, it’s true.

The barometer is dropping. Another storm, hard on the heels of this one arrives tomorrow just in time for Thanksgiving. After guests leave, I’m working on a plan: tabbed on my web browser is a page: Washington’s 100 Best Waterfalls I’ll pack a waterproof cover for the camera. Wear raingear. Pretend I like living here.

Finalists

Sarah Aronson

Aubade (In the Garden of a Thousand Buddhas)

Through resin sleep, wake to each other’s weathermaking, wet pennies’ domed offerings: skygod, heartgod, god of chickadee song. Pace like the sucker hole of sky, yawning at each pass of the prayer wheel. Winter droplets bejewel dogwood, shower easily when shook. White stones send back the story of hands in heat. Toss the russet earth worm to tamped weedlings. Be certain it lives. Point child-wise at geese now gone. Catalogue each look on Buddhas’ face. The titter of birds in bare trees. Theirs, but not only.

20 CIRQUE

Annekathrin Hansen

Foggy Morning Near Point Woronzof

Janet Klein

Just beach pebbles

C.W. Buckley

Comedia, Canto III — Next Stop: Paradise

My secret heaven’s only part-way home

I’ll disembark this bus before the end No one’s turned away into the gloam

The one-man kitchen welcomes every friend

His skillet’s music like the spheres soon sings

Mark how upon such grace poor souls depend

There’s bread and wine and Edith Piaf sings

Her pain perhaps like ours, perhaps her own

A gnat above chianti, angel’s wings

Rain slicks the street that soon I’ll climb alone

But first, this meal to Gypsy Kings’ guitars

Bill paid, I shoulder bag and so atone

I’ll gather warmth I pass through window bars

And kiss your brow to sow a dream of stars

Zouave, Ravenna District, Seattle, WA

Gabrielle Barnett

Peninsular Erasure

Can you recall how it started, not an unfolding, as of spring, but more as fog thickening, the alders insisting it’s been here all along, as unremarkable as lichen extruding from cracks in the bark, or dust collecting at the turning of the stairs, while the 99 B-Line shrieks again, dashing to Clark, Cambie, Granville, Alma, Sasamat, Allison and back six times an hour, rushing by raindrops dangling reckless from utility lines, paused on a determined descent seaward, where flotsam and jetsam beach haphazard twice daily with the incoming tide, washing past container ships queued for port, processing along the inlet at a stately pace towards the cranes, their solitary arms swinging girders ever skyward in slow motion, now two blue and four orange beyond the offset shingles marking the corner line of last century's roof, second story view not yet blocked by high rise complex amassing to house ever more of us, though redcedar groves, arrayed horizontal, still line the patient Fraser's mouth, as since long before steel spanned first or second narrows, bridging lands unceded by the Sḵwx wú7mesh, Xwm θkw y' m and Tsleil-Waututh peoples

21 Vol. 13 No. 2

Lindsey Morrison-Grant

Summer Sidewalk Respite

Toni La Ree Bennett

Confetti

The perfume behind me was not you after all; it was only the waitress.

I hear a parade booming and brassing down the street. That might be your breath in a gust of flute. Excited children flash neon past the cafe windows.

I don’t even know what you look like anymore, but you could soon be coming with your baton, leading the rest of the town behind you.

My heart slams against my spine, my breath suspended at the top of this roller coaster. A bus stops, but you don’t materialize. A waiting man

deflates like a disillusioned balloon. After so many wrong buses, he thought his was coming at last. The parade is not coming down this street.

Under the thinning layers of my skin hot blood percolates, threatening to detonate. I will search for you everywhere at once.

I am uncontainable, like those manic asters spreading through your chain link fence to populate ever-expanding galaxies.

And when I finally find you, I’m going to tear you to pieces and throw you in the air like confetti.

22 CIRQUE

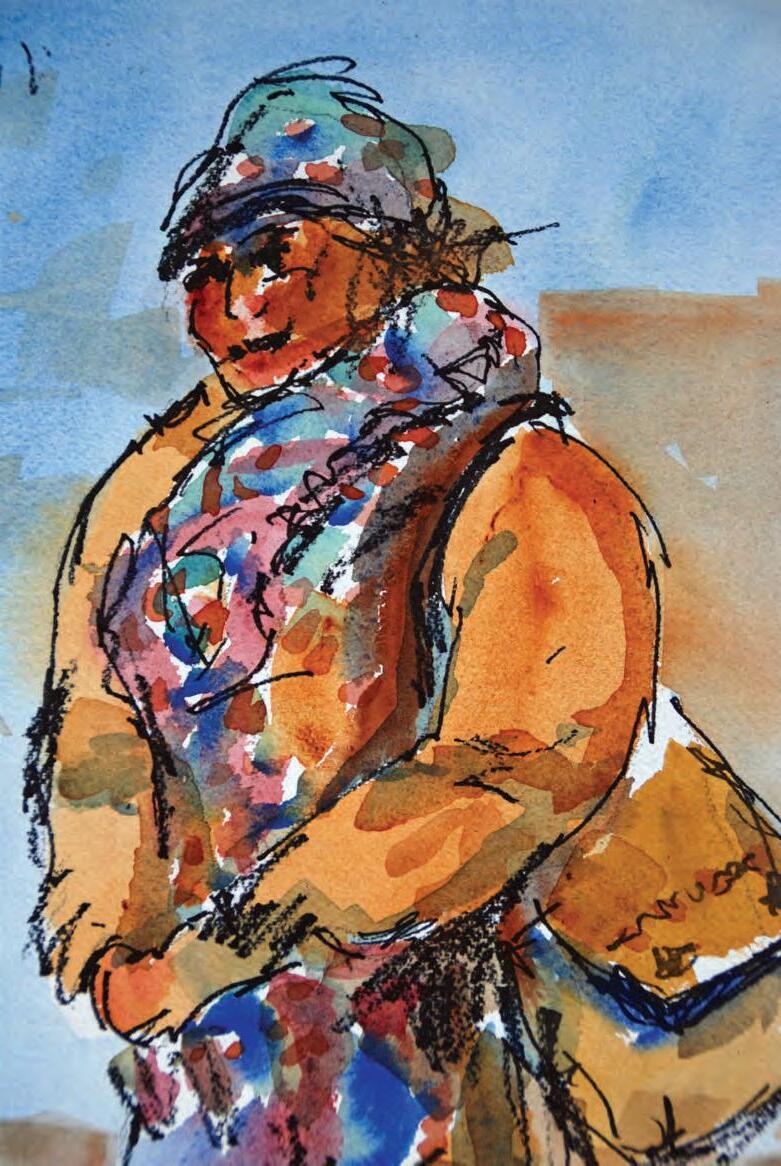

Elizabeth Belanger

What We Remember

Jeffery Brady

The River of Taking

Láx' (heron) rises, taking flight from gravel bar at river’s mouth.

Talk to me, in your old language, which, only now, I seek to learn: Deiyáa, Taiya, Dyea, Dyee Héen—trail river, pack river.

Late, you say, too late to give back.

Your source, deep snow, on the high pass, runs clear in spring through canyon walls; then glacier-fed, grey, slinging silt, uprooting spruce, slamming boulders.

Unseen dangers for those who cross.

And then you rise and take whomever stumbles in: son, daughter, medicine person, soldier, guide, packer, cheechako— they sink under your banks, disappear.

The canoes search upriver, downriver.

And from the water, the Lkoot see: Héen—their river will take their land, not the dléit káa (whites) who think they took it— but the river, forever changing.

Swelling, cutting, widening, jamming.

The first peoples leave the village, graves of ancestors left behind; the white trading post is claimed first, boomtown structures fall down, fall in.

Take your time with the silent graves.

River exposes remains along bank: old wood, cellars, ancestral bones— Héen washes clean, curls in new arc, crossing tidal flats, out to sea.

Gulls on dock ruins fight for spoils.

Flood waters, more frequent now, come spring, summer, fall, even winter— the river takes old trails, new roads, bridges, campsites, park lands, dwellings.

Foolish, you say, but they still build.

The Lkoot from old Deiyáa know. The bald eagles, the raven, even the salmon know—what the river knows and savors from this journey.

Taking back what was never given, as sure as Láx' knows when to fly.

23 Vol. 13 No. 2

Jack Broom

Heron on Fir Island

Helena Fagan

Old Geezers Around the Fire

We borrowed Sally’s wheelbarrow to haul the stones from the front yard to the side lot under the trees, away from the road, carefully selecting the largest with the most promising angles.

The black plastic wheelbarrow, a sissy barely up to the task, flipped often during each trip so that we lifted the same stones over and over before they found their homes in our growing fire pit.

The next night friends gathered for the initiation. One brought wood, one a thermal carafe of spiced cider that most of us drank rather than the merlot. We had marshmallow sticks at the ready, graham crackers and cheap chocolate; rusted deck chairs ringed the pit for those too stiff to sit on stumps.

The night was clear and cool, the conversation of discovery rather than reminiscence, the fire enthusiastic, the bugs nonexistent and yet our new-old tribe disbanded at 8:30, Bob the first to leave, a raised hand his only goodbye. Later, as I lay in bed, I remembered other parties at this house, too many to count during our twenties, the throb of Credence Clearwater, the pot, the Old Bushmills,

the floor littered with guests in the morning, sleeping off the spirits and the night. Now I am pleased to not step over anybody on my way to the kitchen, anticipate drinking coffee in silence rather than making omelets for a crowd. The aroma of the ground beans mingles with timeworn echoes as I breathe in nostalgia free of wanting or regret.

24 CIRQUE

Worn Nard Claar and Sheary Clough Suiter

Nancy Fowler

My World This Morning

Tieton, Central Washington

A woman sits on a concrete wall at the edge of the park, her leather purse held tightly. The sun nears its peak.

In the distance, a loudspeaker announces the end of a shift, muddled from several blocks, but clear enough

to the fruit packers inside the corrugated steel plant. Wildfire ash blankets the nearby orchard of pears waiting to be picked.

Blustery exhaust trails a passing truck. While a lively ranchero song escapes through the open windows of a gun metal gray SUV.

I tap my feet to the rhythm. A red-haired boy waves. He slows his pace to linger behind his mother,

as she pushes a baby carriage across the grass. The aroma of roasting meat to be shredded at the carcineria

fills the plaza. A large yellow Lab, cream to almost white, wags his tail, and drools. A woman with a cane walks out of the grocery

with one small brown bag, and a newspaper folded under her arm. As she crosses the street to sit on the wall with her friend, a crowd of bicyclists swerve around her. Each whoops or hollers

“Good morning!” “Buen dia!” A girl in a white fringed blouse

lifts her arms from the handlebars. The bike keeps a steady course. Angel wings from maple trees spin downward. They touch the grass,

the friends on the wall, the red-haired boy and his mother. They drift into my upturned hands.

25 Vol. 13 No. 2

Wendy Nard Claar

Linn Foster

Guts and Other Internal Mechanisms

A shark washed up on the shore of the black sand beach where the grains are so fine; a walk over a cashmere sweater forgotten on the bedroom floor. I found it lying there, a sad, hollow thing, empty socket gazing skyward, mouth wrenched open. Someone before me saw this primordial work and decided the only value it had were the teeth in its head— ripped out— and the eyes as black as the land it died on, now pried from the skull. Across its belly, a gash, evisceration, intestines strewn across the grains like a map of gore leading to the sea. I stepped aside and watched as the ancient beast lifted itself, following the trail back to a home that did not care. It no longer mattered to anyone but it went anyway, disappearing into the foam.

26 CIRQUE

Deep Fish

Sandra Kleven

James Garland

Cooking Out — Winter in Oregon

1. After seven days of rain

We choose tonight to cook outdoors. Vegetables go on first- they take longer To cook than the chicken. Porch lights and a bottle of red For illumination. There’s a lull in the weather, And for a moment the clouds overhead break, Reveal stars, the Pleiades in velvet black.

Across the valley the Eola Hills, lights blinking on, And all along highway, 22 heading west, to the coast. Then the clouds close back in, Food ready to come off the fire, Rain recommences, Smattering on the porch, Dripping from the somber boughs of Doug Fir, Running into the streets reflecting The night, the rain, the light.

2. My father taught me everything I know About barbeque. I still Hear the sizzle of patties

Atop the hot coals, more summer Weekends than I could count at the grill, The only cooking he ever did, Grease dripping, fire flaring up As he flipped the burgers And turned the dogs.

What would he think — here I am

So many years later, a glass of Merlot

In the dark, thousands of miles away, Blue mountains of the Coast Range, Silhouettes of magnificent Deodar Cedar and Fir, buds on the Big Leaf Maples, And all the heroes gone, Or dead, and the skewers Need turning, what would he say, Mr. “pickle in the middle And mustard on top.”

27 Vol. 13 No. 2

Shauna Potocky

Mount Alice Winter Moon and Jupiter

Mary George (Samson)

Place Name Up the Kasigilagaq River (For John)

It’s autumn again

The trees have turned color

I want you to take me camping

Take me to the Kasigilagaq River

To our fall camp

We can take the skiff up

I’ll pack the grub box, make agutaq (ice cream), brew a thermos of coffee

And pack our jarred and dry fish

I want to fill our buckets with cranberries and wiinaqs (mushy tundra cranberries)

We can sleep along the riverbank

And listen to the beavers’ tails

Lapping against the water

At night.

Our canvas tent will house us and Our wood stove will keep us warm

When the night’s chill chokes our comfort like When the water swallows the land come spring

I need to go and walk beneath the trees

As the leaves fall when the wind blows

Cranberries everywhere reddening the layers of land

Like an artist’s pallet, I want to be there once again.

Up the Kasigilagaq River, around the river bends

Over on the right side where the river rises and falls

And gathers momentum as current and eddies

And then, that slender slough, bringing peace

Last time I wanted to stay and not return back to the Village. But you made me pack up.

I chuckled and told you,

“Let me stay. I’ll marry the beaver and be his bride.”

You didn’t laugh.

Is that why we’ve stayed away?

28 CIRQUE

Beauty in Transition

Mandy Ramsey

Terry S. Johnson Stratum

Mumbai, India

I fall asleep in this huge anthill of a city under an antique ceiling fan. Its mechanical hum, a lullaby. In the morning, I awake to crows cawing in exclamation, wings beating from banyan to sumac. When one lands on the window sill, I am grateful a screen separates me from dark plumage, piercing bill. Street vendors begin their rounds, push unwieldy wooden carts. A few tomatoes, greens of some sort or possibly cheap pots and pans. In between their frequent summons, I detect the swoosh of a street cleaner, resuming her Sisyphean efforts. I can also hear couples chatting as they walk or run, such exercise a luxury for most. Suddenly, an intermittent crack, cricket bat. And if I listen carefully, I perceive the pulse of the nearby slum, one of the largest in the city. A low hum of ceaseless activity, below the soprano car horns, tire screeches, the high-pitched descant of uniformed children rushing to school. Then, chanting. A group of celebrants on their way to a temple? More likely, a funeral procession. Body lifted, enshrouded in white, honored with marigolds, jasmine, roses. Cremation on a bier of timber. Sparks snap into silence.

29 Vol. 13 No. 2

Keep Your Wishes Under Your Wings Monica Devine

Penny Johnson As if the sky can be pressed

As if land can hold still. Look here. Where it bubbles up. Where the elk discriminate between fingertip leaves of sage and bitterbrush. And the soft petals of pink or white. A life cycle that crests in spikes that rip your eyes blind

where wings of wind turbines machete. Knife into the waves of navy blue. Silk rivulets. Pockmarked clouds.

Go ahead. Try.

Hold the sky.

Press the land flat.

The deep fur of us. White dogs. Spice and cream goats. Sweep of their horns. Get out of my path you. I still fight just to walk forward. To keep on while you snake my ankles and tongue my fingers.

And the men that derail. Are they any different? The way they ice over for a flat-rock hand-skipped? The curl of my mother’s cigarette smoke as she watches on. Eggshell promises where I am the raw egg with a broken yoke slipping between ring and middle finger.

All of you crouch with me in this garden that is only allowed catastrophic weeding. All of you cling like sticky vines. All of you whimper in my ears even as I watch you nibble crisp crackers. With salt. Oh this wind is howling. Until at last I will find you all tooth-picked into the corners of barbed wire.

One more fall I will wrap my arms around. These decimated sticks and branches of you. By the bushel-full. These bare bones of you. This brush-fire exploding into the next dry season.

30 CIRQUE

September John Coyne

Charleston Boat Basin

The sky opens up over the Pacific, and I understand for just this moment, things will never be this way again. The little kingfisher flashes over the boats rocking in the surf, a long trail of cirrus clouds shimmers in the diaphanous blue sky.

Three boys coast down the ramp, their fishing poles wobbling, the echoes of their footsteps reverberating off the cedar plank dock, seagulls weaving in and out overhead.

The Jolly Dee eases away from her berth, groaning in increments, stalling, then starting again, trails of black smoke drifting eastward. Her rusty hull slowly revolves into the sunshine.

An old woman rises from her pink -white webbed chair. She’s been straddling the shadow of the Linda Sue all day. Slowly she begins to pull a crab pot to the surface. She sees ribbons of kelp streaming with the tide, sparkling in the foam, and something else, a glimmer of what used to be.

Half a mile out, a red buoy sways in the swells, a study of repetition, its bell reluctantly clangs with each pitch of the waves.

Sue Fagalde Lick South Beach, Oregon

Where is downtown, my mother asked of my patch of ground in the woods. On 101, she’d see flashes of ocean, an occasional house or trailer park, storage lockers, an RV repair shop, the seafood deli, Hoover’s bar, beach signs, the one-runway airport with little planes like dragonflies, but where were the shopping malls, churches, gas stations, and city hall?

At the postal stand, we’d stop, say hello to Valerie, coo at the baby on her hip, nod to the neighbor mailing a box, pause to scan the bulletin board. This is all there is, Mom.

I could see she didn’t understand as we drove down the gravel road and turned right at the Douglas fir. A moss-covered house, an old dog, a circle of mother trees standing guard, a party of robins feasting on worms— downtown as far as I’m concerned.

31 Vol. 13 No. 2

Thomas Mitchell

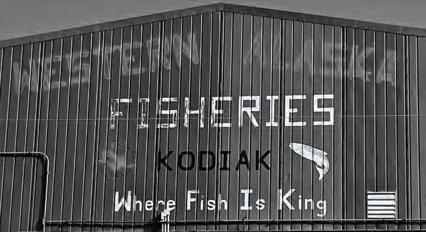

Out back of the hangar Cheryl Stadig

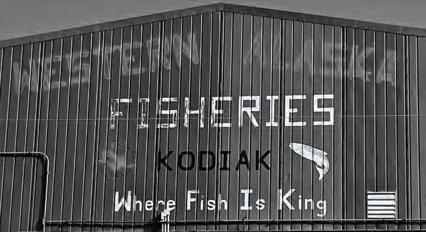

Where Fish Is King, Kodiak Shauna Potocky

kjmunro Yukon summerization

sum-mer-ize – adapt or prepare (a home, cottage, car, etc.) for use in warm weather

√ clean windows

√ vacuum window screens

√ re-install window screens

√ open windows

√ remove grille blanket on front of car replace with bug screen

√ wash winter coats fleece jackets fleece pants hats scarves neck-warmers mitts & gloves from downstairs closet switch with raincoats & summer jackets in upstairs closets

√ trade felt pack boots & ‘goin’ to town’ boots in downstairs hall for sandals & shoes & runners from upstairs closets

√ detach snow basket from walking stick

√ cover ice-spike on walking stick with rubber foot

√ collect snow shovels & sleds from garage & back deck & store in shed

√ move gardening tools from shed to garage

√ shift patio furniture from shed to back deck

√ check supplies of sunscreen

√ stock up on bug spray

• grab a sweater & wait

32 CIRQUE

Along Hart Lake Nard Claar

Justine Pechuzal

Turnagain

You are beginning to bare yourself: tufted, dull, scratched, eroded, scrapped the bones of winter's emaciation.

Day by sun dripped day day, a white shawl frays. Your children use their teeth to scrape towards marrow.

Dark veins crawl up ravines, rivers of melt in steadfast reveal. Newly released rock warms its face in the sun.

The alders probe, bristly fingers thrust through broad snow flanks. Makes a mountainside five o'clock shadow at noon.

Ice floes stranded, shorelines littered with the gravel scattered corpse of cold. High tide shushes, it's time to come home.

Dead grass, leaf litter, dry moss—relics. So many hungers linger in the woods. Even the trees are naked with desire.

Changling landscape, we wait with leaf bud blossom impatience as light dynamites her way through your pass.

Kathleen Stancik

Kathleen Stancik

How I Lost the Wilderness

Flies sip the sweat on my forehead. Him, goading: Go ahead, pee in the trail. I’ve seen little girls before.

The old packer’s chin, tobacco stained, skin leathery as our saddles.

Alpine Lakes Wilderness, fourteen miles deep. (I don’t know the way out.) (I’m only twelve.)

The air so hot I barely can breathe. (His eyes on me.)

Waptus miles behind us. (His eyes on me.)

Stop to rest. (His eyes on me.)

If you want me to show you the way home If you want me to show you the way home If you want me to show you the way home

you’ll have to come kiss me.

No trillium, no lupine, no sparkle on Escondido Lake. Only

tobacco flakes on lower lip, filthy denim jacket, glaze of thirsty eyes.

I walk toward him. I want to go home.

33 Vol. 13 No. 2

Welcome Ashore 2

Tami Phelps

Resilient Mandy Ramsey

Joanna Streetly

Dear Island (location withheld)

You were never much good at letters, preferred the semaphore of the blowhole, geysers of spray— how many? how high?—warning against my solo canoe your outer shore a pinballer’s fancy of reefs detonated by rolling ranks of swell celery heads of sea palms torn from the frontlines tossed aground with stinking mussel shells a no-man’s land of sun-warmed endings, wave-dodging black oystercatchers, shrieking Morse code—grievance & woe!—from tweezer beaks.

Will you take me back after all these years?

I too was torn from you, tossed to a further shore, endured the stink of endings. But still I long for your cliff by the sun-bleached whalebones looking at you with that first gasp, while sunset deer file out to the meadow, ears & tails aflicker, silent in the telescope of memory.

Don’t worry, I know you too have changed —that instead of whale skulls, I might find fragments of the children we raised, the bay still singing with their bones Perhaps that’s what I’m asking for—the tweezer beak of a song to pry me open, expose the grit.

Tim Whitsel

Whosoever

Someone burned the old church down last week. It was not a revival service, it was a volunteer fire department practicing for something more urgent.

Sure, it was only a shabby white shell, the stained glass windows salvaged, replaced with plywood.

A crinkled foil shield as tall as the average man kept the fire from igniting the classroom wing that now belongs to the new imposing sanctuary.

Its hulk had risen in stages, summer by summer. The exterior shows a dark teal so even passersby

in cars or in crew cabs with toolboxes and extra diesel onboard will know this is a new Pentecost.

The building costs would have been unthinkable without a few old timbermen dying and leaving their bequests. What quest? Which flickering calm?

Volunteers barricaded Hella street all burning day. Steps call to the basement, empty wisdom socket.

34 CIRQUE

My Three Secrets Sheary Clough Suiter

Oh, to have seen the barn when red Janet Klein

Tonja Woelber

Dancing at the Seaview Café

Beer-soaked floorboards ripple as river-rafters stomp in time, a toddler does a break dance, rubber boats in rhyme.

Two plump women splice the crowd, tango arms in fleece, scoot their tevas ‘cross the deck to a funky bluegrass beat.

Hippies sporting tie-dye, woozy with delight, fling their partners through the air this bright midsummer’s night.

Singer belts her heart out, sings into the din, a jelly jar with ones and change is stuffed above the brim.

Clouds turn purple over Baldy, against the inlet seagrass waves, slow sunset turns to amber as the last song plays and plays.

35 Vol. 13 No. 2

Sunset on the Flooded Nile (Lake Nasser) Lucy Tyrrell

Arctic Fox Monica Devine

Arctic Fox Monica Devine

NONFICTION

Francis Opila

Refuge at Dungeness Spit

Olympic Peninsula, Washington state

Spit: a small point of land especially of sand or gravel running into a body of water

—Merriam-Webster

everything. Awareness rises beyond thought, imbibes in the brisk breeze, the Olympics out in snow-covered glory, silhouettes of the Vancouver Island Ranges across the strait.

***

***

Sweat is slow to evaporate. Hot hazy sun, no breeze. Rafts of noisy gulls and black scoters feed 200 yards offshore, perhaps following the path of a submerged gray whale. Scores of sandpipers swirl in formation along the beach, pivot onshore, flash black & ivory, vanish in white-washed blur of sand, sea, and sky.

***

Dungeness Spit extends over five miles offshore in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The spit was formed by the action of wind and water on glacial sediments deposited about 10,000 years ago. Sea currents carry sediment along shorelines in a process known as longshore drift. As the current passes the headland, it is diverted offshore, slows down and drops its sediment load. Over time sand is gradually moved out from the headland, creating the spit. It continues to grow about 15 feet per year.

***

We saunter, hand in hand, along the sandy beach. Warm afternoon sun calms our skin, our nerves, our overthinking

For ten thousand years, Native people lived and prospered on the lands now known as the Olympic Peninsula. At the time of European contact, the native Klallam people occupied the ridges, forests, rivers, and shorelines along the northern peninsula. They fished for abundant salmon in the strait and rivers. They gathered camas, bracken fern root, and other plant foods in nearby prairies. ***

Woven ripples of wind & current paint the surface. High tide rolls in, retaking the flat sand, churning smooth pebbles & rocks that fold under the thunder of breaking waves. Harbor seals & mergansers dot the water surface, plovers skitter along the water line, snagging sand flies on rotting kelp. Driftwood, sun bleached & sea washed, lies helter-skelter on brown sand & stone.

37 Vol. 13 No. 2

On April 30, 1792, Captain George Vancouver anchored the HMS Discovery near the spit. He named it New Dungeness Spit after a famous headland on the south coast of Kent in England.

***

In 1874 to avoid forced relocation by European colonizers, Chief James Balch led the Klallam to purchase their own land and create their own community. They purchased 210 acres along the Strait of Juan de Fuca, now called Jamestown, after James Balch. In 1981 the federal government finally agreed to official recognition of the tribe, resulting in the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe of Washington. S’Klallam is a Salish term meaning “The Strong People.”

***

Surf surges with storm, high tide, and spray. Gray clouds are swept on their winter journeys. Today there are no sea birds in the nearshore. We scramble along the backshore over logs and sea worn stones, careful where we place our feet. The south wind propels us until we reach the landmark pole lodged in the sand. We turn back, gusts bite into our faces, we pull up our hoods, listen to this squall—a song in a different key.

***

Dungeness Spit lies entirely within the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge. President Woodrow Wilson established the refuge on January 20, 1915 as a breeding ground for native birds and a wintering refuge for brant, a small sea goose, and other birds. The refuge comprises a variety of habitats, including sand beaches, protected bay waters, seagrass beds, mudflats, along with forested uplands. Over 240 species of birds have been noted in the refuge.

***

Today the Jamestown S'Klallam tribal members live throughout the Sequim-Dungeness Valley. The tribe preserves their cultural and historical legacy. Their work includes restoration of critical habitat for the recovery of salmon and native shellfish. There are several other Klallam groups living on the Olympic Peninsula and in Canada.

***

Dance of sun & shadow, wind & waves, green sea & azure sky. A warmer day, a cloud bank hangs offshore, the bay side calm. As we walk, we shadow a loon who dives out on the strait, surfaces, preens, dives, vanishes for stretched time. We traverse driftwood logs & root wads, tangled piles of giant kelp. The sea breeze croons, we sing along. As fog floats in, our perception wanders. We breathe the spice of salt & sea grass.

38 CIRQUE

***

Connie Feutz

All Because of Errol

I see her every time I walk into my home through the back door. At the end of a short entry hallway, upon a green-painted cupboard is a framed black and white eight by ten photo. Taken in New York City in the summer of 1948. A closeup. She’s twenty-two, in a striped, loose blouse, clasping a photographer’s light stand against her shoulder, its electrical cord gathered loosely in one hand. The photographer caught her in a full laugh; he caught her in her glorious youth at a momentous time of her life. She’d been invited by Life Magazine to come work as a stringer—from Missouri—for the summer. She’s brimming with joie de vivre. She’s beautiful. She’s my mother.

Errol Flynn—yes, the dashing, raven-haired Golden Age Hollywood superstar, known for his love of drink, cocaine and woman, who had starred in more than fifty films such as The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Adventures of Don Juan (1948)—sparked a cascade of events that resulted in Life Magazine inviting my mother to work for them that summer. That same cascade also pulled my parents into one another’s orbit. For evermore.

In the spring of 1948, Errol Flynn got into a public spat at the Los Angeles Airport with his wife, causing him to miss his flight to New York City. At the airport, Flynn ran into Peter Stackpole, staff photographer for Life Magazine Flynn and Stackpole knew each other well as Stackpole had photographed Flynn on numerous occasions, including extended visits on Flynn’s yacht, The Sirocca. Five years earlier, the prosecution in a trial accusing Flynn of statutory rape of two girls called Peter Stackpole in to testify. Stackpole, who had been on the yacht at the time of the alleged assaults, testified that he had driven one of the girls home and that “she appeared ill at ease and cried most of the way home. She talked a lot but it didn’t seem to make much sense. She was very emotional and upset.”

Flynn was acquitted.

Now five years later, Errol Flynn impulsively decided to join Peter Stackpole on his flight to St. Louis and from there, take a train ride west to Columbia, Missouri where Stackpole was on assignment for Life. (Not quite in the direction of New York.) In the narrow confines of a transcontinental airplane, and later on a train, where no doubt the liquor had flowed, one wonders just what these two men might have talked about. Alas, we shall never know. What we do know is they checked into the Daniel

Boone Hotel in Columbia, Missouri.

My mother, Dorothy Jean Estep, grew up in Columbia, Missouri. Her lifelong dream was to be a journalist, inspired by female pioneers in the field such as Margaret BourkeWhite and Martha Gellhorn (who had smuggled herself onto a hospital ship, unceremoniously locking herself in a WC, thus becoming the first woman to report on the landing at Normandy in 1944). In high school, Dorothy began working at the local Columbia newspaper, The Tribune, continuing there throughout her time studying journalism at the University of Missouri in Columbia (Mizzou)—the first University to teach journalism in the U.S. It was, and remains, renowned for its journalism program.

On May 6, 1948, as a third-year student at Mizzou, The Tribune editor, Jack Hamel, called Dorothy into his office. Errol Flynn had surreptitiously checked into the Daniel Boone hotel. He instructed her to get the story.

She found the hotel lobby crowded with local gawkers. Hotel officials were blocking the stairs and elevator, only allowing hotel residents to pass. Through a contact at the hotel’s front desk—someone she had known in high school—Dorothy Jean was able to sneak up a back stairwell, becoming the first reporter on the scene, the first one to file the story. She interviewed the debonair Mr. Flynn as he stood shirtless in front of a mirror, lathering his lean face: a shaving brush in one hand, long razor in the other. We know this because Peter Stackpole snapped her photograph.

Errol Flynn slipped out of Columbia before dawn the next day as stealthily as he had slid in, hiring a driver to take him to St. Louis. Flynn’s life would continue along its well-established trajectory: More movies, more scandals, another marriage. Whereas for this young female reporter, his impulsive decision to descend upon Columbia, Missouri for scarcely twenty-four hours, changed the course of her life.

Peter Stackpole’s assignment for Life was photographing young coeds at the University of Missouri and Stephens College. He hired Dorothy Jean to be his assistant. A week after her piece about Errol Flynn ran in the Columbia Tribune—and was picked up by other national newspapers—Life Magazine sent Dorothy Jean a telegram, inviting her to New York to work as a researcher

39 Vol. 13 No. 2

over the summer.

Ecstatic, she rushed to share the news with her longtime mentor and editor.

A slight, bespectacled man, Jack Hamel read the telegram, raised his eyebrows, then handed it back. “Dorothy Jean, there is no reason for you to go to New York,” he said solemnly. “You’ve got a good job right here until you get married. You’re meant to be someone’s wife—not a career woman.”1 Stunned, she stared at the man whom she had worked for since high school and whom she deeply respected. She turned and left the newsroom fighting back tears.

Confused and heavy-hearted, she walked to the student boarding house where she rented a room. On the front porch, she ran into another student who also lived there, whom she had not yet met, Emil Feutz, aka Fritz. Fritz knew Dorothy Jean was the Tribune reporter who had made it into Errol Flynn’s room and who had scored the first interview. Everyone in town knew that.

He congratulated her. She looked away, eyes swollen. He asked if everything was OK. She shook her head and handed him the telegram, telling him what her editor had said.

Unbeknownst to Dorothy Jean, Fritz Feutz was someone for whom dreams mattered. Obsessed his entire life with airplanes, by the age of seventeen he had acquired a commercial pilot’s license and an instructor’s license. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the FAA grounded all small private planes fifty miles inland from the West Coast. Fritz, not yet eighteen, hitchhiked or hopped trains (paying only when he got caught) from Missouri to California, to buy small planes at rock-bottom prices. He then flew them back to the Midwest—over the Rockies—to sell for a profit. He did this until he received his draft notice in 1942.

Fritz tried to join the Air Force but was denied entry because he had only one kidney (one had been removed because of kidney disease). Missing one kidney did not keep him from being drafted into the army, into the 66th division and stationed at Fort Rucker in Alabama. Not particularly happy about ending up in the Army rather than the Air Force, Private Feutz got into an argument with his commanding lieutenant about the most effective infantry maneuvers. The officer threatened to court-martial him for insubordination. Ever defiant, Fritz wrote a letter to the War Department in DC. requesting his commission as a 2nd lieutenant. As a graduate from an accredited Military Academy, Fritz knew he was entitled to one. He also knew if they didn’t give him the commission—which would put

him on par with the officer trying to court martial him— they would have to discharge him.

The Department of War (as it was aptly called back then) granted him his commission, but on limited service: He could not go overseas. That fluke decision, very likely made by some War Department bureaucrat, in response to this uppity private, saved my father’s life. On December 24, 1944, his division—the 66th—was on a ship crossing the English Channel on their way to France when they were torpedoed. Seven hundred and forty-eight infantrymen and fourteen officers died. No one survived.

Once the war ended, Fritz decided what he really wanted to do was to test airplanes. This meant returning to school to study aeronautical engineering. In the fall of 1947, at age twenty-four, Fritz enrolled at Mizzou and shortly thereafter moved into the basement of the student boarding house where he met Dorothy Jean.

On that front porch in May, he told Dorothy Jean in no uncertain terms, “Life Magazine! In New York City? Are you kidding me? How could you say no to an opportunity like that? Who knows when it will ever come your way again?”

His confidence, his conviction, was startling. “You’re right…”She paused, and with a broad smile added, “You are right. I am going to take this job. I’m going to New York City!”

40 CIRQUE

Joe Reno Goddess

Fritz responded, “Good choice. And I’ll fly you to St. Louis to catch your flight.”

That is how my parents met. Two weeks later, my father did fly Dorothy Jean to St. Louis—in a Stinson Gullwing, pale yellow with grey trim. (This my father easily recalled sixty years later. When asked what my mother had worn that day, he stared at me blankly.)

This is how I imagine it. They drove to a local, regional dirt airstrip. I can see him: 6’4”, lean, wearing dark aviator glasses. Once they were seated (the Gullwing is a small plane) reaching over with a long arm making sure her door was properly latched. With a sharp “Clear prop!” he started the engine.

Her first time ever in an airplane, Dorothy Jean was not prepared for the sudden clamor and shuddering as the propeller ramped up. The din was deafening as they taxied down the dirt runway. At takeoff, Dorothy Jean sat bolt upright, gripping her seat. Fritz flew over Columbia, pointing out their home, the Tribune building, the Daniel Boone Hotel: Everything in miniature, the streets in a perfect grid, the people and the cars so very tiny, moving through their day. The world she had known her entire life was moseying along, without her, while she gazed down from a gracefully banking single engine airplane. She felt a tug, a recognition, that she was now leaving that world behind, for places unknown. For a whole new life ahead.

Beyond Columbia, the colorful and quilted landscape of fields, forest and the rivers had to have mesmerized and captivated her. As did the handsome pilot’s confidence and skill. By the time they had touched down at the St. Louis Lambert airport, Dorothy Jean was smitten.

(This I DO know.)

Life had hired her for an internship for talented and ambitious journalism students. Though they were expected to return to their respective universities at the end of the summer, all hoped—upon graduation—that Life would offer them a position as a staff reporter.

On her return to Columbia in the fall, Dorothy Jean found Fritz friendly, but not interested in dating. To Dorothy Jean, he remained an aloof, attractive and intelligent enigma. And the only man who had outwardly demonstrated support for her intellect, her abilities and her aspirations.

Dorothy Jean Estep graduated in June 1949 with numerous job offers, including one from Life Magazine The pace and the intensity of New York City had been overwhelming, but while there she had visited and

enjoyed Philadelphia. So when The Philadelphia Inquirer offered to interview her, she said yes. She was waiting until after her best friend’s wedding in August, where she was the maid of honor, before leaving for Philadelphia.

In the receiving line at the wedding, wearing an orchid pink, strapless dress, Dorothy Jean turned and was surprised when the next person in line was Fritz. Unbeknownst to her, the groom—who lived in their same boarding house—had invited him. But she was even more astounded when Fritz put his hands on her shoulders and warmly kissed her. It wasn’t unwelcome; it was just so uncharacteristic for him, this public display of affection.

In the days that followed, Fritz, who had one more year at the university before graduating, actively pursued her. They played tennis; they picnicked; they danced to “Night and Day” by Bing Crosby and “Mañana” by Peggy Lee.

Shortly before Dorothy Jean was scheduled to depart for Philadelphia, and on one of her last days working for the Tribune, she was in the newsroom late. Over the Associated Press wire came news that a plane had gone down near LaSalle, Illinois and that the plane had burned. A crop duster by the name of Emil Feutz had been pulled out from the wreckage, with serious burns. Dorothy Jean called the La Salle News Tribune and learned that Fritz had been taken to a nearby hospital.

At dawn Dorothy Jean was behind the wheel of a borrowed car, maps splayed on the passenger seat, driving the three hundred miles to the hospital in Peru, Illinois. She had never before driven outside of Boone County; the trip took her seven hours. At the hospital, she told the staff she was his sister. She found Fritz bandaged and recuperating in a room with three other patients. Amazingly he had not broken any bones, although he did suffer severe burns on his arms and legs.

He managed a weak smile when he saw her. “So, Miss Dorothy Jean Estep. Just what brings you to this neck of the woods? Is Errol Flynn in the next room?”

She cracked a smile as she sat on a chair next to the hospital bed. She asked him what had happened.

He explained he had been crop dusting, killing corn borers. He had let himself get distracted, trying to not dust the farmers in the nearby fields and didn’t see “that bloody telephone cable until it was too late. Pretty damn stupid of me.”

They conversed briefly on other topics when Fritz blurted, “Well, Dorothy Jean. Would you like to get married before school starts in a couple of weeks or wait until Thanksgiving?”

41 Vol. 13 No. 2

She stared at the man before her, still captivating even in the ragged state he was in. This was her fourth marriage proposal. There had been no question that “No” was the correct answer to the other three. Her heart pulsed in her throat. “Are you serious?”

He smiled, squeezed her hand and nodded.

“My… ”She struggled to catch her breath. “Well, Mr. Emil Feutz, I think I might like that idea… Why yes, I think I do. Let’s do it. Before school starts.”

My mother believed that had they waited two months, until the break at Thanksgiving, that Fritz might have changed his mind.

They married three weeks later. My mother wore an elegant green satin dress for her wedding, defying all tradition. Given this storybook beginning, one might assume this was the start of a long and happy marriage. Sadly, no. Once they married, Fritz forbade Dorothy Jean to work (“No wife of mine needs to work.”). Her doctor told her douching was contraceptive. (Well, not exactly). She was pregnant within a few months. Four children within six and a half years, while her husband worked building his career as a test pilot, which included frequent short and extended travel.

My father, a staunch conservative and my mother, a liberal Democrat2 who received The New Yorker until the day she died, fought most nights over the Vietnam War, the fights only ending when she rushed away in tears. I can remember as a child, finding my mother in the basement, holding the door of our huge chest freezer open. She was hanging her head into it crying. It was the only place she could have a sliver of privacy with the blast of cold air aiding her in stopping the flow of tears. When I was seventeen, once over dinner, after consuming too much wine, my mother confessed she had never felt my father loved her (she apologized later for disclosing this to me). After my father passed away at the age of ninety, my mother and I were cleaning out a space where he had had a desk on the second floor. A desk he couldn’t get to for the previous fifteen or so years because of advanced Parkinson’s. The desk drawer was deep: I pulled it out and in the far back found three cheap Hallmark cards with string necklaces. Dopey cards, with goofy dancing dogs saying something like Had a great time last night! Stunned, I showed the items to my mother. Calmly, she shrugged it off, telling me, “I know your father had his women, his onenight stands. None of them were serious, or so I believed,” she told me.

I turned away, blood boiling.

My mother and I were two peas in a pod. We could talk for hours about anything and everything. We cared about books, about world events. She supported me in every interest and endeavor of mine, no matter how hare-brained or pie in the sky. Our laugh is the same as is our love for creating simple, elegant meals shared with loved ones, where you linger for hours. Our time together, our relationship, remains one of the most cherished and meaningful of my long life. I have photos and mementos of hers all over my home. I don her jewelry, her scarves, favored jackets. When she died, she graciously left me her wedding ring. She modeled for me how to be a strong, loving and compassionate woman and mother. Someone who could laugh at herself.

My father and I fought until I left home, and then some. I was not the demure, petite, feminine daughter he wanted: I was more like him (tying sheets around my bed as an eleven-year-old, scaling out the window of our twostory house, dropping onto the attached garage, to dash off into the night; a skilled and reckless horseback rider; challenging him on the rules and curfews bestowed upon me as a daughter that my brothers didn’t have; dropping out of college and traveling solo internationally from the age of twenty for two and a half years, starting with a solo bike trip on the East Coast, from Baltimore to Novia Scotia and back, on a three-speed Schwinn, my calves snug against the cargo pants I had picked up at an Army surplus store.)

Yet now, I do view their sixty-six-year marriage as a good and successful marriage. True, the first forty years were awful, but the last twenty-five or so redeemed that. I know my mother thought so as well. And I have to credit my father for this change. My father in his late fifties and early sixties went through a drawn-out and difficult emotional period. He admitted he had no clue how to love. And it was to my mother that he turned. He saw that his entire life had been wrapped up in achieving his professional aspirations (which he did), and that as a result, he had no meaningful personal relationships: not with his wife, his four children nor any friends. He spoke to me about this as well: how he feared he was creating the same tense and distant relationship with his two sons that he had had with his own father; that he had no memory ever of any tenderness from either parent. He was an only child to a frail woman, who quickly became infirm with kidney failure. She had doctors and innumerable surgeries. My father remembers her as cold, unapproachable and bedridden. Very likely in pain.

My father was born in 1923. The family farm—in the

42 CIRQUE

family since 1865—was foreclosed during the Great Depression (1929-1941). His father, my grandfather, worked two jobs to buy the property back. With an absent father and a sickly mother, my father was on his own. He told me he was “hungry all the time.” Viewed as wild and undisciplined (I’m sure he was), upon the death of his mother, at age fourteen my father was placed into a military boarding school where he was the first cadet to solo an airplane.

No one could have anticipated that graduating from the Missouri Military Academy in 1941, combined with some characteristic headstrong behavior, would later save his life.

After his difficult emotional time, in his own idiosyncratic and at times fumbling way, my father strove to let each of us know just how much he loved and appreciated us. But especially so my mother.

My father contracted Parkinson’s in his late sixties, and my mother was his caretaker until the very end. Her wish was that he would die in her arms: And that wish was fulfilled. Even though he had been restricted to a wheelchair for months, he and my mother still slept together every night.3

A couple weeks before my father died, at the age of ninety, I flew out to Missouri to be with them. Some weeks earlier my mother had been out climbing and pruning fruit trees on the family farm and had fallen and broken an ankle. She was limping around wearing a protective brace.

The guest bedroom was just across the hall from theirs and throughout my first night I heard soft voices. A couple of times during the night I tiptoed over to their door and peeked in to see if either of them needed any assistance. My father’s long arms slowly swayed above them as they whispered and giggled.4 At daybreak I could still hear them, so I stuck my head into their bedroom. “Good morning, you two rapscallions.” They beamed. In turning toward my mother, my father had somehow thrown a leg over her protective brace. Since he no longer had the strength to lift it, she was pinned: My mother could not move. Her head on his shoulder, she said to me, her face as open and innocent as a child’s, “We’ve decided we are entwined forever.”

My father, his arms around her, holding her tight, nodded. “Yep. Yep, that’s right. Entwined forever. Nothing is ever going to pull us apart.”

“I can see that.” Eyes brimming, I said, “Well, just give me a holler when one of you needs to use the restroom.” I gently closed their door and went off to make our morning coffee.

Thank you, Errol.

The author was named after a Howard Hughes’ airplane, The Lockheed Constellation ("The Connie").

1 My mother’s best friend from the age of eleven until her death at eightyseven told me she had met Mr. Hamel numerous times. It was her belief, which she had shared with my mother, that he was in love with her.

2 My mother took me to my first demonstration when I was twelve. I grew up in Ferguson Missouri; we lived one block from a solidly Black community, Kinloch. Our city council wanted to build a wall at the end of our street. My mother took me, signs in tow, to protest that in front of City Council. I was told much later that a member of Kinloch’s City Council had told his Ferguson colleagues, “Go ahead. Build your damn wall. My boys can easily jump it.”

3 My younger brother, who lived nearby, told me when he would visit and either when they were napping or early in the morning, he’d check up on them in bed. He couldn’t see my mother: he wondered where she was. Then he figured out: her 5’4” petite frame was ensconced within my father’s long curved body, his arms wrapped around her.

4 When I asked him the next day about his waving arms, he matter-offactly told me, ‘Oh that. I was waving at my buddies who have gone before me. They’re calling me.”

Lisa K. Harris

Spastic Dog Woman

I set my sights on befriending Retrievers Couple. They live close and their yard is thick with the island’s native plants. Since I’m a biologist, I figure we’ll bond over sourcing hard-to-find rhodies and salmon berries for my developing garden. They’re into animals, too; both retrievers are Best-of-Show material: brushed-out coats, perfect gait, proud form. This late-September Tuesday afternoon, I time Noelle’s walk for 3:15, when Retrievers Couple promenade north-south along our road, hoping to meet at the crossroads.

I fasten the halter onto my Australian shepherd’s slender chest and imagine the conversation with Retrievers Couple. “You’re the woman who built the new house, aren’t you?” the reed-tall husband will ask. After I nod, his curly-haired wife will add, “Beautiful home, you certainly thought through every detail. It’s magnificent.” Well, maybe not this last bit, “magnificent” too fawning for first introductions, although I do hope they see my home as a work of art. Then the wife will say, “We’re so glad we’ve run into you, you must stop by. We’re just down the road.” She’ll pivot and point to their home, four doors down. And because having a glass of wine on the deck watching the sunset over the Puget Sound’s placid waters and the

43 Vol. 13 No. 2

distant Olympic Mountains is what I see them do, the husband will say, “We can have a drink at sundown.”

My friend-making opportunities are few. Most of the homes on Bush Point are vacation rentals or second homes. They’re vacant now, partially because it's fall and partially because Washington’s governor has told everyone to stay home, and their full-time residences are elsewhere. Of those hanging on, most keep to their pandemic pod, so my best shot of meeting anyone may be dog walking.

It’s a serious pastime here, elevated to a spectator sport with not much else to do these days: best groomed, best mannered, best gait; pure breeds alongside rescues. Any sign of malcontent—barking, lunging, even sniffing too long at one spot—is admonished. Poo removal, too, is a medaling event, with handlers folding at the waist and arm scooping with special bags, pick-up within seconds of steam’s first rise. The handlers are impeccable: sturdy shoes for inclement weather, pressed khakis, fluorescent-yellow jackets, wide-brim hats. Outdoorsy attire with matching pooch apparel: glow-in-the-dark collars and leads, and on brisk mornings, yellow fleece-lined rain jackets. Neighbors walk their dogs north-south along my street every day at nearly the same time. Major leaguers all, with Noelle and I at club level, free-style our specialty.

With our house perched upslope, I watch them with Ava, my teenage daughter, from our floor-to-ceiling windows and refer to them as Retrievers Couple, HoundBeagle Lady, Fluffy-Poodle Man. If my neighbors do the same, I am called Spastic-Dog Woman.

“Hurry or you’ll miss Retrievers Couple,” Ava says, not looking up from her phone, “Meet them so you have somebody else to talk to.”

“I’ll change first.” In from the garden to take a work call, I dust leaves from my sweatshirt. “I’m a mess.”

“It’s not like you’re going on expedition to Mt. Everest, which is the only reason anyone should wear the clothes they wear. You’re walking the dog. Be who you are. Don’t change yourself to appease others.”

I hate it when Ava uses my advice to advise me. After clipping the leash onto Noelle’s halter, I scurry out the door.

Noelle does not like to be rushed. She raises her snout vertically and sniffs. Born blind and deaf, her sniffer is all she has to read the world. I tug on her leash. She takes a step left, then right, a zig and a zag, then halts. My anxiety pheromones scream danger to her. I breathe and slacken her leash; hopefully communicating everything is fine, just fine.

But it’s not. “Newbie” emotions percolate: loneliness, insignificance. I'm the new kid in class without anyone to sit with at lunch. I'm skilled, though, at making the first move, as I’ve had plenty of practice, attending nine schools before graduating high school.

After moving to the island, though, I’ve procrastinated on trying to connect with others. Beyond construction workers and our immediate neighbors—both women in homes so close I smell their dinners: stir-fry to the north from Lisa, Hamburger Helper to the south from Elsa—I haven’t met others. We normally live eighteen-hundred miles away in southern Arizona and only visited the island to check on the home’s progress. So caught up in the hubbub of construction, which took three years, I hadn’t the desire to try connecting. Friendships would come after the house was done, I figured as I finagled timelines with plumbers, electricians, and cabinet makers. Eventually, Ava would leave for college; I would graduate to emptynester status and spend long summer days on the island making new friends. But the pandemic changed our circumstances.

Noelle walks on. I gently nudge her forward. But she abruptly squats and pees in the middle of our gravel driveway. I side-step yellow rivulets as they flow downhill and spot Retrievers Couple briskly walking, fast approaching Lisa’s driveway entrance.

“Come on,” I say to my dog’s bladder. But my words don’t register.