* Your sizes. Your selection.

1. Visit our showroom with your room sizes.

2. Order from our roll stock carpet, vinyl and underlay (Full price items only)

3. Arrange the collection or delivery** of your order. **Delivery charges will apply.

* Your sizes. Your selection.

1. Visit our showroom with your room sizes.

2. Order from our roll stock carpet, vinyl and underlay (Full price items only)

3. Arrange the collection or delivery** of your order. **Delivery charges will apply.

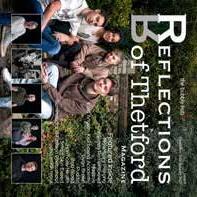

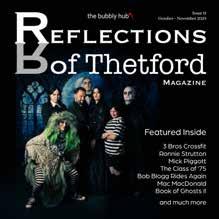

Following on from their highly acclaimed ‘The Welkin’, Magic Floor Productions are about to wow the fair folk of Thetford yet again.

The Addams Family the Musical, Dracula-style set design, magnificent music, stunning lyrics, impeccable vocals, ghoulish charm, dark humour, the most unconventional family await.

Sit back, relax and be dazzled.

https://www.ticketsource.co.uk/magicfloorproductions/e-moeerk

Photography - @mangus.co.uk

Costumes and Cast - @Magicfloorproductions

by Martin Angus (Editor)

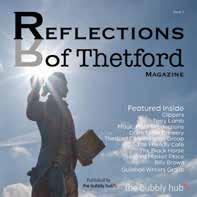

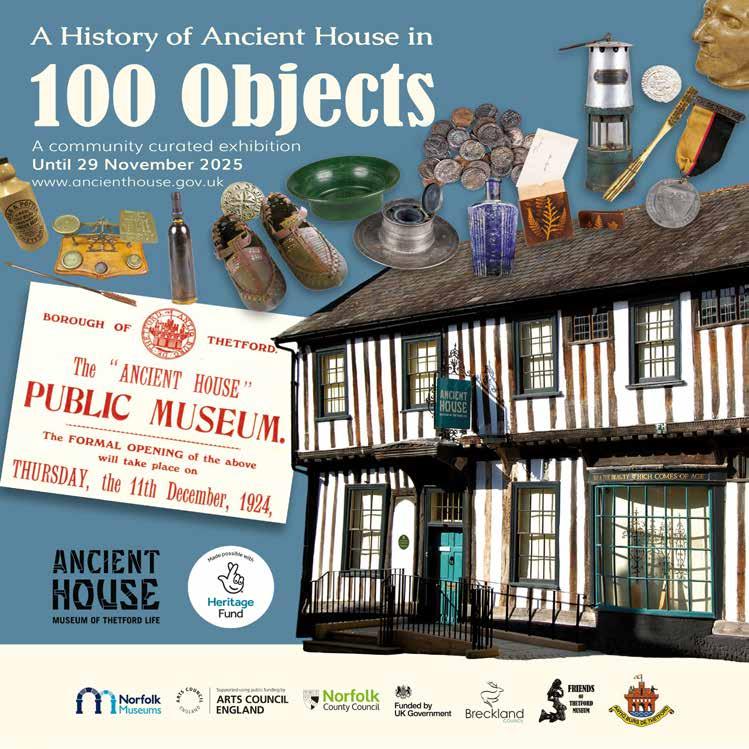

Welcome to Issue 11 of ‘Reflections of Thetford’ magazine.

A bit of a mixed selection of stories, but this is how we like it.

I have to confess that I have never been so nervous of including tales of Thetford, as I was interviewing our very own Ronnie Strutton. How am I going to ensure that it all remains family friendly I was thinking, but I need not have worried as Ronnie shared not only the more raucous stories, but also the quiet silent personal stories he has carried for decades.

Our front cover this edition is thanks to Magic Floor Productions, offering our lovely town yet another amazing production of ‘Addams Family - The Musical’, if you haven’t got your tickets yet you will need to get your skates on as they are selling fast (see page 18 for where to get your tickets).

Yannis appears on our pages this edition, for 40 years being one of the most well known estate agents in town, being someone I went to school with, it was a

privilege to hear his story so far and his sharing of the plans for next chapter in his life.

Tunnels, first hand WWII tales, the joy and positivity of volunteering, are just a few topics covered this edition.

And if you have ever wondered who those two blokes are that stand every day on the corner of the market square, then your question is about to be answered.

Bob Blogg rides again, and we have transcribed the second ghost story which was kindly donated to the magazine, rocketing our reader stats off the chart.

As always there is so much more in the magazine than I have the space to write here, please enjoy!

As I sat down to finish writing this introduction, we received some very sad news, one of our favourite contributors to the magazine has sadly passed away. Ray Hoskins, who appeared in issue 7, as ‘A bit of a Dark Horse’,our love and best wishes go to Joy and their family.

©Reflections of Thetford is published by The Bubbly Hub. All rights reserved 2025. Whilst every care is taken, the publisher accepts no responsibility for loss or damage resulting from the contents of this publication, as well as being unable to guarantee the accuracy of contributions supplied as editorial, images or advertisements. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means or stored in any information storage or retrieval system without the publishers written permission.

3 Bros - Jack Bloss

Who’s this guy? - Ronnie Strutton

Service to our town - Mac MacDonald

50 Years On - Staniforth Class of ‘75

The Medusa Project - Bob Blogg

The Last Lookouts - Graham and Trevor

Four Decades in Property - Yannis Prodromou

A New Life in Norfolk - Ralph Mead Growing Together - Mick Piggott

Volunteering - Chelsea

Wartime Thetford - Terry and David

A Walk Amongst WWII Artefacts - Stephanie, Albert and Fergus

Will They Ever End - Thetford Tunnels

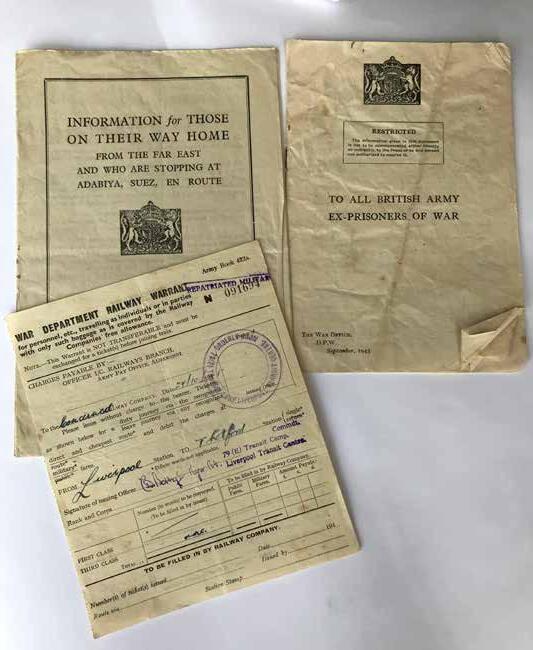

The Journey Home - Sandra Starling

Thetford’s Book of Ghosts - Book II Letters to the Editor

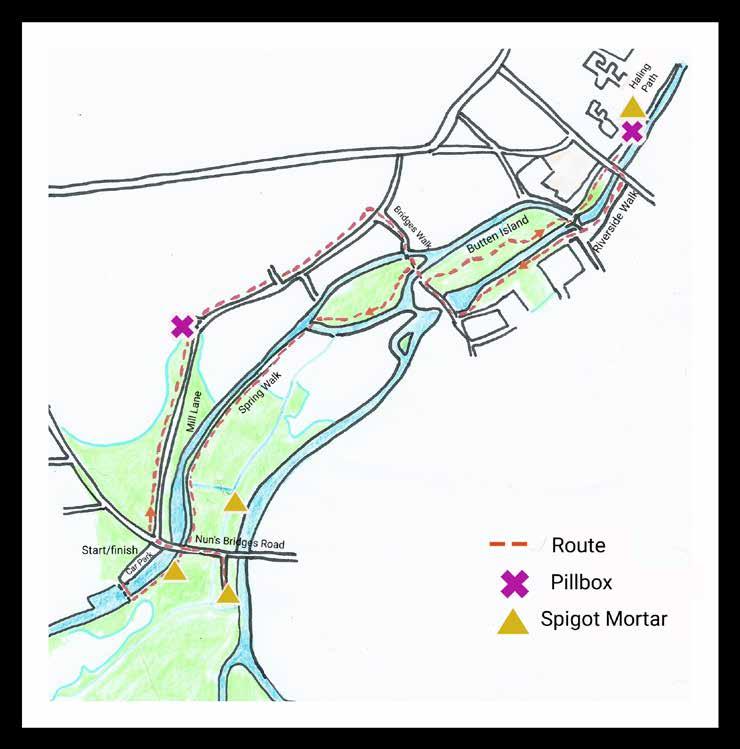

Written by Andy Eden

It is surprising what you can find on an industrial estate, particularly in Thetford. In amongst the small businesses, distribution centres and even some heavy industry, 3 Bros CrossFit has carved itself a niche. This will come as no surprise to anyone who is one of the many regular attendees but it was all new to me. I went to meet Jack Bloss, owner and head coach.

When I arrived, Jack was pounding away on a cycle machine, clearly someone who practices what he preaches. A few minutes later, with a coffee in hand, I asked Jack what exactly is CrossFit?

“It is functional movement performed at high intensity, varied form session to session.” So in simple terms, it’s a fitness program and

methodology. It is based on constantly varied functional movements which aim to improve general fitness, strength, heart health and flexibility. It has combined elements of other exercise and training disciplines to create something new. CrossFit was developed by Greg Glassman in 2000 in America and now has over 10,000 affiliated gyms around the world. Do you have to be fit to do this? I asked. No, everyone can come along. We all have to start somewhere and it won’t take long for your fitness to improve.

Jack first discovered CrossFit back in 2016. He had been serving in the RAF regiment and had just returned from a tour in Afghanistan. Married to Chanelle and with a young family, Jack decided to leave the military. Long periods away, either training or on a tour abroad, were not what any

of them wanted. Now a civilian, the fitness regime of the military was missing from Jack’s life so he looked around and discovered CrossFit.

2018 saw Jack coaching in Norwich and it was that year, after long discussions with Chanelle, that they decided to start the business, 3 Bros CrossFit.

With some money put aside for the startup and plans in place, they were almost ready but then Covid struck. As everyone was locked down there was no possibility of going ahead until the restrictions were lifted. The challenge then was to keep the family financially stable. Chanelle was a nursing assistant at the time, so Jack looked after their boys during the day then worked at Tesco’s during the evening. As with many people during that unprecedented period, it was a question of keeping a roof over their head and food on the table.

When gyms were allowed to reopen, they took the plunge and opened 3Bro CrossFit, originally based in Brunel way. I say ‘they’ because as Jack is only too ready to admit, Chanelle does a lot of the behind the scenes management and is a driving force in the business, that is when she is not running her commercial cleaning business. People were ready to get out again and the number of people attending the gym started to climb. Three years later, in November 2024, 3Bros CrossFit moved to its present premises in Napier Place.

With membership now at just shy of 140 members, obviously Jack could not coach everyone, so he took on extra staff. Now there are three coaches aside from Jack. Charlie, Dave and Phil. I hope Phil won’t mind me mentioning his age. At 63 he is fitter than most people with only half his years

‘3 Bros with dad’ by Mangus Photography

and is an argument against the excuse ‘I’m too old.’

One corner of the gym is covered in certificates and medals from competitions where members of the coaching team and 3 Bros CrossFit have been placed, both here and abroad. It is an impressive testament to the quality and dedication of the coaches and serves to inspire everyone in the gym.

Jack does not just see 3 Bros CrossFit as a place for people to get physically fit and healthy though. When they moved into their present premises, Jack added a coffee percolator to the reception counter, filled from 3pm every day. He explained that he didn’t want people to just come in, exercise and then leave. He wanted to encourage a community spirit, and the coffee played its part. Almost immediately, he found that people would finish their workout then grab a drink. This meant that conversations were started and a sense of camaraderie began to grow.

Now, the gym is a very social place with everyone very supportive of their fellow members. People are encouraged on to achieve the best they can and its often the last to finish that get the biggest cheer. It’s not about doing better than the person next to you, it is about challenging yourself. Parents bring their children and get them into the habit of exercise. Classes for 12 to 16 year olds are held regularly. Spouses are encouraged to come and join in as well as friends and work colleagues making it a real community. Yoga sessions are also held on a Sunday as well.

3 Bros CrossFit works closely with Thetford Academy and runs classes during term time, often for pupils who have had problems getting on in

academic work. Once the training starts, everyone supports each other. Even those who perhaps stood a little apart from the group before. It really helps build team spirit. There is no back chat to the coaches, the physical exercise takes over and everyone wants to do well.

As you would imagine in today’s world, 3 Bros CrossFit has a social media presence on Instagram and Facebook. Jack also coaches online. So, what does the future hold? Well, there is work just starting to convert a store into a shower room for a start. In time, Jack says that they may open a second location but that is some way off. Beyond that, Jack would like to arrange regular competitions that involve all the fitness groups in Thetford. Perhaps something along the lines of ‘Thetford’s fittest’. Once again, the theme of ‘community’ comes to the fore.

So, I asked Jack, one last question. Why is it called 3 Bros CrossFit? The answer is that Jack and Chanelle have three sons, Sonny aged 8, Vinnie aged 11, and Ronnie aged 12 and it is named for them. So, when Jack talks about a family feeling to the gym and wanting to encourage families into exercise and a healthier lifestyle, it is easy to see where that comes from. The gym has become a real community and that can only be a good thing. If you are feeling a bit sluggish and want to improve your health and fitness, this may well be the place for you. https://3broscrossfit.co.uk/ https://www.facebook.com/3broscrossfit/ https://www.instagram.com/3bros_crossfit/

Tel: 07584 414181 jack@3broscrossfit.co.uk

Written by Martin Angus

On Sunday someone will point at a photograph and ask, “Who’s this guy?” If we’re lucky, they’ll keep reading. Because behind the grin is Ronnie Strutton: butcher’s lad turned publican, footballing goalmachine, practical joker, reluctant emigré, occasional inmate, arm-around-your-shoulder friend, and the sort of natural raconteur who can turn a trip to the shops into a three-act play.

He is a man of Thetford now—though it took a while to arrive at that. His story is a mosaic of small-town myth and big-city memories, of scraps and second chances, of farce worthy of Ealing comedies and tragedies that leave a quiet weight in the room. It’s all here: the capers, the kindness, the chaos, and the closing advice he gives his younger self. If an editorial is allowed a thesis, let it be this: communities are knitted together not by perfection, but by people who belong to them loudly. And for better or worse, Ronnie has belonged to Thetford loudly for more than half a century. London to Thetford, 1963: “I Hated It… At First”

Ronnie was born in 1949. By the time he was 14, his parents had decided to swap London’s pace for Norfolk’s promise, landing the family in Thetford in the early 1960s. The move tore him from the teenage gravity well of Notting Hill—friends, mischief, and an early start to working life. He was, by his own cheerful admission, “a pain in the arse at school,” skipping lessons to ride dustcarts and sweep streets in a prized Royal Borough of Kensington cap. When a headteacher essentially offered the deal—find work and you can leave—Ronnie took it. Butcher’s aprons suited him more than algebra ever did.

Arriving in Thetford, he disliked what looked like emptiness. No pavements thrumming with drama, no instant spark of city life. Unless you had a bike, he says, “you didn’t do anything.” So they biked the common and carved little tracks into the scrub, and while his mouth still said “I hated it,” the place slowly began to work its quiet alchemy. You can hear it in the way he tells the story; the complaint is habit, the love is reflex.

t. 07891 294639

thegardenshedflorist.co.uk thegardenshed22@gmail.com

His father found work first at Hobal Engineering, then Thermos, before painting became the old man’s trade for the rest of his working life. His brother didn’t stick— love tugged him back to London—but Ronnie stayed. “Been here ever since. Wouldn’t move away now.” He tried once: a brief, sunny spell in Tenerife with Eve, the woman who would anchor the next three decades of his life. He loved it; she missed home; and a pact is a pact. They came back.

Home, then, is Thetford. But it’s also London in his bones—early impressions formed under the pavement level, literally. He remembers his mum tucking the kids under a bed when the Notting Hill race riots spilled past their basement window, car tyres and shouting at eye level. It’s a small boy’s postcard of fear and fascination, and it tells you something about Ronnie’s lifelong habit of standing close to the action.

The first job in Thetford was a factory post on a fly press—monotonous, unforgiving, “a shit job” in his crisp summary. He didn’t last. But the butcher’s trade pulled him back: Baxter’s down the town, where he put in a few steady years. He can still walk you to the spot—under an arch and along King Street—that’s long since been rebadged and rearranged by time. The landmarks have changed; the muscle memory hasn’t.

From there the CV becomes the full Ronnie: bits and pieces, steady graft and side-hustle favours, a knack for getting on with people who didn’t get on with many. He worked for the late Mick Croxton—Crocky, reputedly the hard man of town—clearing the old stockade whenever a refresh was due. “He was good as gold with me,” Ronnie says, and the sentence sits there, simple and unforced: you could either get along with Ronnie or spend years failing to.

Soon enough he became what some towns are lucky

to have: a publican who is more than a landlord. He ran the Trowel and Hammer for years, then the Rose and Crown, the Green Dragon, a stint holding the fort at the Red Lion in Caston, even a rural place near Sandringham with a glass shortage so dire he had to summon backup. He fixed the glass problem, filled the bar with carrot factory workers finishing shifts and polishing off Pilsner from the bottle, and made the night hum. Good pubs are theatre; Ronnie understood stagecraft.

The work took him outside of pubs too. There was a time subcontracting for TNT, shuttling bank cheques from Suffolk to Milton Keynes. Parked one afternoon, he hears a radio piece on alopecia and rings in. The researcher asks what worked. Straight-faced, Ronnie offers the advice a doctor once gave him—rub the patches with your finger tips while watching telly, something about static—then delivers the punchline: “I ended up with hairy fingers.” The studio collapses; the producer never gets him to air. You don’t put a man like that on a delay and win.

Thetford Then and Now

Ask Ronnie how Thetford has changed and you’ll get the unvarnished version: the wistful defence of a “lovely little town,” the cranky lament for what’s been lost, the grumble about today’s messes, the laughter puncturing the gloom. There’s no politician in him; there is plenty of pride, and some edges, too. Memory is a fierce editor. What remains constant is belonging. Even when he vents about the present, it’s the investment of a man who has given his seasons to this place and raised daughters and grandkids here, who goes down the town and is greeted by name by coppers he once belted—more on that in a moment—and bar staff he trained decades ago.

If this were a civics lecture, we’d footnote the forces that reshape towns—economics, migration, policy, time.

www.ticketsource.co.uk/magicfloor-productions www.ticketsource.co.uk/magicfloor-productions

But this is Ronnie’s editorial, and the truest fact is that he never left. He fought for his place in it (occasionally literally), built businesses in it, found love in it, and is still telling stories that stitch the town together. That’s a kind of citizenship.

Some men mellow with age and erase their own roughness. Ronnie prefers honesty. “Up here, I got known for fighting,” he says, with the shrug of someone who doesn’t particularly recommend it. There were the squaddies, the Americans, the weekly rows that congeal into folklore. If there was a magnet for the Saturday night melee, it was the Rites of Man down Brandon Road—now a hall, once a ring. He, Riggs, and Donut would be barred on Friday and in through the door by last orders, three free pints deep, because the only thing more predictable than a bar ban is the joy of breaking it.

Yet the heat of the night made room for lifelong friendships, and not only with the lads at his shoulder. He tells a story about Horry Bunting, a policeman who rose to inspector and whom Ronnie came to love. Their first meeting ended in a wallop—Horry trying to break up a fight, Ronnie in the mood to oblige no one. Years later at Bunting’s packed funeral in Diss, a speaker recalls the night he was “hit harder than ever in my life,” and a hundred heads swivel quietly toward Ronnie. He had long since gone to see the man in his final days. “Lovely man,” he says—a phrase he uses often, always about people, never about himself.

The police, as it happens, allegedly made allowances for this particular rascal. He played rugby with them and they tipped him off about roadblocks, steering him around checkpoints when his paperwork was more wish than fact. One veteran officer once stopped him just to introduce a new recruit: “This is Ronnie. He’s got no

licence, no tax. Leave him alone.” It reads like myth. It isn’t.

The best measure of Ronnie’s appetite for sport may be the nine goals he once scored in a single match—nine, as in all of them—in a 9–0 thumping of Brandon. The Americans on base invited him to join their inter-base team after he kept leading the line in annual friendlies; he declined rather than swap passports or board a plane. Thetford Rovers, Town, Brandon, Lakenheath, Barningham—he pulled on shirts the way working men in market towns always have, wherever there was a game, wherever a manager thought, “Get Strutton.”

Football held him longest, but rugby had its charms, especially when suspensions in one code encouraged a sabbatical in the other. He loved the third XV, the proud anarchy of it, the afters at the bar. Sport gave him a ladder up into community: a way to sort out disagreements without a court date, to belong to a team sheet, to have his name read out on a Saturday.

Eve walked into the Trowel and Hammer looking for a previous landlord named Ian. She found Ronnie instead. Within weeks she had a job back in London; within months she had Ronnie. He says the dates, then recalculates the dates, then lands on what matters: thirty-five years together, married in 1990 at Watton.

The wedding is pure Strutton theatre. Guests took the invitation “just turn up” literally—eighty people crammed into the registry office. When the registrar reached “any lawful impediment,” a mate in a gorilla mask twice shouted “Yeah!” and found himself educated, briskly, about the seriousness of the moment. Weeks later the registrar shows up to a fancy-dress do at the pub, laughing. “Funniest wedding I’ve ever done,” he said. It’s

not exactly church bells, but those who know Ronnie know the sound of joy when they hear it.

He had been married before; he speaks without rancour about the past and with fondness about the three daughters who stayed local. Eve, meanwhile, is the partner every publican needs: tolerant of late nights, fearless with banter, and—for one brief adventure— brave enough to try Tenerife with a man who absolutely would have stayed. They laugh a lot, Ronnie says. He trusts her. She gives as good as she gets. It’s an ordinary, glowing review of a long marriage.

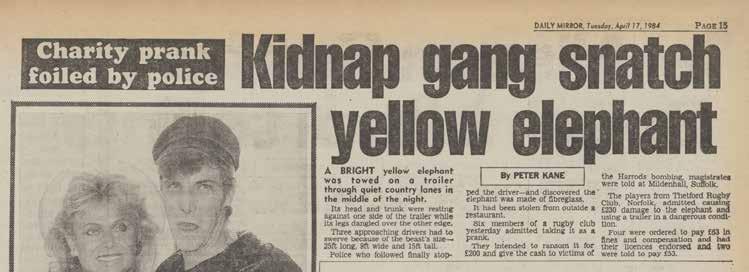

Capers, Collections, and a Yellow Elephant

Every town keeps a cabinet of local legends; Ronnie’s fingerprints are on at least two drawers.

First, the collection. In the wake of the Harrods bombing in 1983, a group of them went pub to pub raising money for the police officers’ families. Ronnie dressed as Father Christmas and waddled into a rugby club packed with a touring side. One bloke resisted the bucket. “Father Christmas says if you don’t put something in,” Ronnie told him, deadpan, “you’re going to get the biggest right hand you’ve ever seen.” Coins flew. In the end they upended a bucket of change onto a police-station desk—no counting, no ceremony—and the tally came back at £71. In small-town economics, that’s a princely sum, and in small-town ethics, it’s the point.

Then, the elephant. Happily, this one is comic and mostly harmless—though the police, the Happy Eater at Red Lodge, and a puzzled manager behind a curtain might disagree. Six of them, a trailer borrowed with a friendly key and a story about picking up paperwork, and a plastic elephant liberated after a recon mission proved it wasn’t bolted. The plan foundered on the bright idea to drive past the base; blue lights arrived, eyebrows raised. “Why didn’t you stand it up?” one officer asked. “We did stand it up,” replied Ronnie’s mate Riggs. “He

The story even made the national press.

was tired. It just lay down again.” In the end they were nicked for damage rather than theft—“someone had to be blamed, I suppose”—and shuffled in and out of court until a magistrate looked at the case, looked at the lads, and decided enough was enough.

Not every stunt ended with a chuckle. Once, as teenagers, they staged a mock post-office robbery with an old starting pistol, scattering shoppers who had no idea the guns were blanks. It was a daftness that reads differently in a post-2000 world, but this was a different time and a different town. Ronnie tells it with obvious shame and equally obvious fondness for the idiot swagger of youth. The point isn’t to excuse; it’s to recognise a life in context.

Shadows and Reckonings

No editorial worthy of the life would skip the darker chapters. Ronnie doesn’t. In his twenties he fell in with three men and took part in a real robbery on base. He calls it out plainly: not what he was, not what he wanted to be, but what he did. He served time. Inside, as outside, he made a kind of family of it—earning a nickname he gleefully repeats (“the poison dwarf,” courtesy of a towering prison guard with a mouth to match) and a Sunday reprieve to play football for the prison staff’s team. On release day a sergeant threatened to haul him back if he mouthed off on the train; Ronnie couldn’t resist a parting volley as the carriage pulled away, then nearly died of fright when Ely was crawling with police for reasons having nothing to do with him.

Years later came the worst night of his life, one he will go to his own grave turning over. Working the door as a bouncer at the Mill, he pushed across a crowded room to head off a row and a young woman—known to him and his family—fell. She was drunk, he says. She died. The charge was ultimately described as an unlawful killing. Ronnie changed his plea to guilty on the judge’s pointed assurance that he would go home rather than

face a long sentence, and he has lived with the scar tissue of that paradox ever since: a legal outcome that stayed his course and a moral result that broke his heart. “One of the worst things that ever happened to me,” he says softly. Years later, a relative of the woman—after long bitterness—approached him in a pub and kissed his cheek. “I’m sorry for all the trouble I caused you.” Forgiveness is never owed; when it comes, it lands like grace. You can hear in Ronnie’s voice that it did.

He tells another story that is harder to set down. When an immediate neighbour allegedly targeted local girls with abuse, Ronnie admits he didn’t wait on process. He went through the man’s door and did what magistrates call grievous bodily harm. The bench fined him the doctor’s fees and remarked, in open court, that the victim “deserved all he got”—a line that will rattle readers who prefer our systems tidier. What do we do with this? An editorial is not a judge. But it is obligated to hold two truths: that vigilantism corrodes us, and that the instinct to shield children is as old as neighbourhoods. The story, like the man, refuses to sit in one box.

Being Known

List the names and it reads like Thetford’s roll call: Crocky, Dougie Nemo, Barry Keymer, the marketplace faces who bantered with everyone’s nan, the rugby blokes who lived for third halves, the coppers who winked and the coppers who didn’t. Some are gone now—“old Riggs,” Ronnie says, voice lowering; it’s the only time you see him appear small—but they populate his stories like saints in stained glass. He is proudest that most of his closest mates were locals. He arrived a London lad; he became a Thetford man.

If you want to feel the social map of those years, ask where people gathered. “Rites of Man,” he says without a heartbeat’s pause. If you want to know what it meant

to be barred on Friday and welcomed on Saturday, to owe a fiver from payday to payday and still have the landlord push a pint your way, to be absolutely skint but fully wealthy in friends, go sit under the old beams in your memory and you’ll get it. Ronnie’s life is civic glue of this kind.

No portrait of Ronnie is complete without the routines and punchlines, the quips that fall out of him as easily as breath. Many of them aren’t reproducible in a family paper; many more depend on timing you can’t print. But the gist of the canon is this: he thinks quick, he puts people at ease, and he tells stories with the precise, mischievous rhythm of a man who has always loved an audience.

He once told a registrar that he would bring half the county to the wedding and did; he once told a rugby forward in a Santa suit that generosity would be a wise decision and proved it; he once told a radio researcher the joke about static electricity and hairy fingers and broke the poor woman clean in half. In pubs and on touchlines and leaning over market rails, he has been running the same show for decades, and the town has been happy to buy a ticket.

The first family home in Thetford was No. 2 Elm Road, new enough that the fences hadn’t gone in. The openness feels symbolic now. He tells a bawdy tale about the parties across the green in those early estate years, complete with a local woman interviewed on national news as if she’d sprung from a convent. The point isn’t the gossip; it’s the music of early Thetford estates, the optimistic chaos, the way a street becomes a family whether it means to or not.

Ronnie’s own family spread out but mostly stayed close.

Two sisters in town, another in London, a cab-driving brother-in-law who commuted from Thetford every day—a fact Ronnie insists is true no matter how many eyebrows shoot up. If the editorial had a soundtrack, it would be the noise of a big clan in and out of one another’s kitchens, kids shoved two-at-a-time in the front of a bike for rides around the block, the ordinary ways a life gets full without anyone noticing the fullness happening.

By the end of any long conversation with Ronnie, two strong impressions remain. The first is that he is, and has always been, gloriously programmable for laughter. He will knock on the window of anyone’s day and leave them lighter than he found them. That matters more than we give it credit for in a time that drifts toward bile.

The second is that he is unblinking about the parts of his life that hurt. He does not pretend he never fought; he doesn’t pretend he never crossed lines; he does not dodge the tragedy that lives in his chest. If a community is honest, it doesn’t idolise or exile such men; it holds them near enough to be complicated. The editorial tone here, therefore, is deliberate: warm, not hagiographic; candid, not cruel.

What advice would he give the younger Ronnie? “Don’t be like me,” he says, and then defines what he means. He never walked away. When trouble came, he stayed, all the others legging it, and that, more than any grand design, is how he ended up where he ended up, again and again. He doesn’t wrap it in false romance. He simply says he’s laughed most of his life and that he’s still laughing now, mostly with Eve, who tells him to behave and doesn’t always expect compliance.

There’s another moral tucked in a smaller moment. Once, he says, the step-daughter of one of his best mates walked into the pub with her first wages. Ronnie grabbed the packet and bought a round for the house.

Nobody who knows him is surprised. It is possible to see this as madness; it is also possible to see it as theology. In the economy that matters most—the one measured in favours and opportunities and people who’ll turn up when you’ve got a skip to fill—Ronnie has always been rich.

An editorial usually ends with a crisp summation, something elegantly phrased and dignified. Ronnie would hate that. He would prefer, I suspect, a line that sounds like him and leaves room for the next laugh, the next pint, the next story told on the marketplace to whoever is new in town.

So here is that ending:

On Sunday, someone will point at a photo and say, “Who’s this guy?” He’s the lad who hitchhiked the wrong way out of Thetford at 14 and still came home. He’s the butcher who knew the archway by heart and the publican who could fill a bar with glasses no one had the first day. He’s the footballer who once scored nine and the rugby scrapper who turned coppers into mates. He’s the bloke who raised £71 in small coins by threatening, as Father Christmas, the biggest right hand you’ve ever seen—and the bloke who knows full well that some chapters of a life do not end in laughter and never will.

He is, in short, a Thetford story. Not tidy. Not exemplary. Unforgettable.

If you want him in one sentence, borrow his own: “Everyone knows me for laughing and taking the p*ss.” It is not the worst epitaph a man could hope for. And it’s not yet time for epitaphs, anyway.

There’s a town still to disagree with, a wife to tease, a joke to ring into a radio show, and, with any luck, an elephant to set back on its trailer, upright this time, so as not to attract attention.

Written by Martin Angus

On the day the Berlin Wall fell, 9th November 1989, Mac MacDonald was 8,000 miles away, standing in the bar of the Upland Goose Hotel in Port Stanley, having said his vows just two months earlier. It was 9 September 1989. He and Sue—both RAF—became, as far as anyone can tell, the first forces couple married in the Falkland Islands. “We rekindled our relationship down there and she asked for commitment,” Mac says with a grin. “I was a young lad. I said ‘okay’—and we did it.”

Such sentences reveal a lot about Mac MacDonald: decisive, practical, prone to underplay the audacious. They also foreshadow the arc of a life that runs on a simple, hard-won fuel: service. Four decades in uniform. A move to Thetford that he’ll tell you was the best decision he and Sue ever made. Years of litter picks and residents’ meetings and speed watches and stubborn committee work. An MBE for building bridges between base and town. And, in the past year, the frank recalibration of a family facing cancer together. Mac’s story is not the tidy narrative of a career politician.

He insists he never wanted politics at all. Yet the town now knows him as an independent councillor who answers emails, sweeps streets, stakes positions, and— when necessary—absorbs the frustration of things that can’t be changed overnight. This is the portrait of how he got here, why he stays, and what he thinks Thetford needs next.

Letchworth to Lossiemouth: the long apprenticeship

Mac was born in Letchworth, Hertfordshire, “in my grandmother’s house on the A505,” he says, the detail offered the way service people track the world by roads and runways. His dad was a double glazing salesman; the family moved with the regional patch to Oxfordshire and settled in Didcot. “All my school years were there— until I was 18, when I joined the Air Force. Shortly after, Mum and Dad moved, so I never went back to Didcot or Oxfordshire again.”

He enlisted on his 18th birthday. The first posting— Lossiemouth—felt like “nosebleed territory… being that

far north.” Then Peterhead, further still. In 1988 came Berlin, behind a wall that came down while Mac was on detachment to the Falklands. “It was a weird feeling,” he says. “You’re away doing your job and the world shifts back in Europe.”

Sue had also been in the RAF, a stewardess. The military’s geography separated them; marriage brought her to Berlin, but female postings in her trade weren’t available there then. She left the RAF to join him and worked as a stewardess at the villa of the Chief of the General Staff. A year later she rejoined; together they began the long, familiar dance of “together postings” that could still mean half a county between you. Wiltshire for her at Upavon, Wiltshire-but-not-really for him at Hullavington—close in military terms, far enough in family ones.

Northern Ireland came with a daughter and the logistical calculus of two serving parents. “By the time our daughter was four, she was on her fifth house,” Mac says. “Something had to give.” Sue left regular service for stability. The postings rolled on: Lincolnshire, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, back to London—and then Bavaria.

Teaching NATO about the unthinkable

Oberammergau, famous for its Passion Play and fairy-tale setting, has another identity: home to the NATO School. Mac spent three years there teaching what no one likes to think about but everyone relies upon professionals to understand—“Weapons of Mass Destruction,” he says plainly. “I taught nuclear plotting and chemical reaction cell control for all of NATO.” The work took him from Washington—where he received NATO’s Military Member of the Year award from General James Mattis—to Moscow’s Combined Arms Academy, to Macedonia.

The job was absorbing, but “isolated for a family.” When promotion called, he returned to the UK in 2008 to

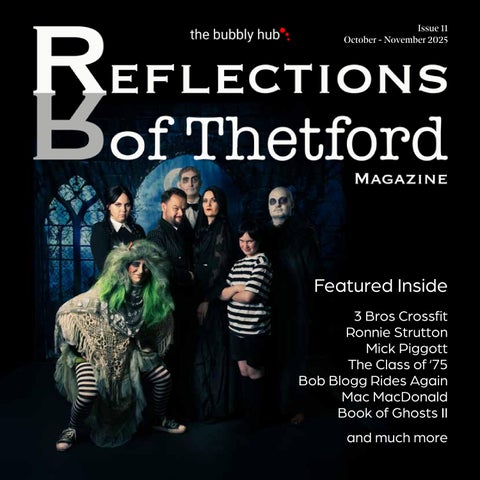

Freedom of Thetford Parade

(Sylvia Armes in the background)

RAF Honington—a posting he admits he didn’t relish on paper. “It’s our depot; can be inward looking,” he says. “But it turned out to be brilliant. I’m still there.” He cycled through six or seven roles, finishing as Station Warrant Officer, the senior Warrant Officer on station—a job that came with responsibilities that mattered locally, including orchestrating the RAF Freedom of Thetford parade.

He left the regulars in 2022 and joined the reserves the next day, initially splitting his week between two days in uniform and three with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. “I loved the War Graves work,” he says. As the reserve role grew, he moved into the RAF’s Land Activity Safety Team—health and safety across the service’s non-flying activity. “Not the most dynamic thing to talk about, but essential,” he says. Vehicle accidents, noise injuries, root-cause analysis and mitigation. “It’s about finding solutions, and keeping our people safe in a job that is often full of risks”

He also manages the RAF Regiment Heritage Centre at Honington, an expansive, behind-the-wire museum that most locals don’t know exists. “About 40,000 square feet,” he says. “We do get a lot of visitors by arrangement. You must come and do a piece on it.”

Alongside all that, Mac serves with the King’s Bodyguard of the Yeoman of the Guard, the sovereign’s ceremonial bodyguard—the ones who look like the Beefeaters but aren’t. “We are summoned for duties such as State Opening of Parliament, investitures, lying-in-state… in fact almost all state ceremonial events,” he says carefully. Protocols restrict social-media fanfare, so he references it quietly, as one of those duties you carry because you were asked and because it’s right. “We wear a cross belt,” he adds, the sort of detail a military mind values. “Designed to hold an arquebus.”

Thetford: reluctant move, joyous belonging

Honington brought the family to Stanton first, then

Walsham: village life, beautiful but “a bit out of the loop” with a teenager in the house and two commuting parents. Sue shopped in Thetford because it had the supermarkets; Bury St Edmunds had the job and the pull of habit. “She said, ‘What about Thetford?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know, I’ve never really been.’ I was reluctant, really. And it was the best move we’ve ever made.”

They arrived around 2011. Fourteen years on, Mac calls Thetford “home” without hesitation. “After all the years of travelling around… we’ve lived in a lot of places and this is good. We’re lucky to live here. Our daughter lives less than a mile away in town, with her husband and our grandson. It’s superb.”

There is a conviction underneath the contentment: Thetford is not a compromise. “People are quick to run it down,” he says. “I’ve lived around the globe. Nowhere is perfect. In Uxbridge we were privileged—and the crime was off the scale. Here, one incident becomes the story. Someone graffitis a chair and it’s huge. We need perspective. The most important thing for this town is positivity. Get involved. Enjoy it.”

Mac’s route into local politics wasn’t paved by manifestos but by bin bags. “There was a lot of rubbish around,” he says. “You can either look at it and say that’s terrible—or you can do something.” He and Sue turned a one-off tidy into a regular, monthly litter pick through the Norwich Road Residents’ Association. “We’d borrow equipment and go out on a Saturday… then the next month on a Sunday. On average, 13 bags each time— sometimes much more, which is sad. But it’s become established, and kids have joined in after school talks. Some now do their own litter picks.”

Practical habits bred practical networks. He joined Community Speed Watch to check the “crazy speeds” on the roads behind his home on Mundford Road. “We

A Snap of Mac on duty at a Royal Garden

had a tragic death there,” he says, the sentence hung with the silence of the avoidable. Speed Watch led to the Safer Thetford Action Group (STAG), which he now chairs, liaising with police and the Police & Crime Commissioner on priorities. “The police have moved to SNAP [Safer Neighbourhood Action Panels]—more of their control—but they’re happy for STAG to continue. It’s about what we can do to make a safer town.”

All roads—litter, speed, streets—run past the same faces, the same doers. Some of those faces belonged to town councillors. Colin and Sylvia Arms. Stuart Wright. Mark Robinson. “Colin in particular—very forceful in a nice way—would say, ‘You should be doing this’,” Mac recalls. “I resisted for ages. Politics, as a word, doesn’t fill me with any desire.” In the end the invitation and the work aligned. He stood.

At first he wore the Conservative rosette—less out of crusade than habit. “Just where my voting had been,” he says. “But I gave it up after a short time. Conservatism isn’t me. I want to do stuff for the town. It shouldn’t have a label. Many people say town councils shouldn’t have party politics at all—and I agree. We’re unpaid. At this level it should be councillors, not factions.” He ran and now serves as an independent.

What a councillor can—and can’t—do

The best councillors learn quickly that energy alone won’t move a lamppost. “You get excited about making change,” Mac says, “and then you discover the levers belong to someone else. It’s somebody else’s budget. Roads are county. Planning authority is district. You don’t have the controls. It’s massively frustrating.”

He offers an honest political economy 101: “People trusted you to be a councillor, and the answer to most things is money. Better service means paying more. That’s the truth. But no one wants to say it and no one wants to hear it.” The structure doesn’t help. “We work

by majority, which is right. But it means sometimes you argue your case, lose, and live with it. And the threetier system—county, district, town—means ownership is muddy. You can spend six months arguing whose job something is.”

He worries aloud about devolution changes on the horizon, the shape not quite set. “It might go from three tiers to two,” he says. “Could make it clearer; could make it harder. We might end up with more responsibility and more of the things that cost money and don’t make any.” He rattles off the unglamorous realities: play parks, public toilets, cemeteries. “Everyone wants them. No income. They cost a lot to maintain and are often vandalised. We’ve worked hard at the cemetery— groundwater issues limited burials. So we’ve looked at planting to help, and at cremation plots. Thinking outside the box. Because we’ll all need that one day.”

Planning: the grit that makes the pearl

Mac chairs the town’s planning committee—an advisory council, not the planning authority. “We have an input; we’re asked for views,” he explains. “We discuss, recommend. Quite often Breckland will do what they’ll do anyway—and that’s frustrating. But sometimes they agree and follow through. We’ve stopped bad things; we’ve enabled good ones. From preserving green spaces that might have been built on to large developments like King’s Fleet. Next (the clothing store) even came to talk to us. You have to keep going. Otherwise the option is to sit back and let someone else do what they want.”

His favourite planning story is a small one with big lessons. On the Admirals Estate, a decommissioned play park on Ramsey Close—abandoned after vandalism and bounded by a railway line—was suggested for allotments. “Some residents liked the idea; many didn’t,” Mac says. “We held a meeting at the Church on the Way. People said: wrong direction. Then we discovered there

was a covenant that prevented it anyway—buried deep in handover paperwork from years ago.” The upshot: the council tidied the site, planned new fencing, and kept it as open space. “If we’d just ploughed on, we’d have been wrong,” he says. “It’s not a ribbon-cutting story. But it’s the right story.”

The town centre, by graft not magic

If planning is grit, the town centre is the pearl—and a fragile one. Across Britain’s market towns, footfall is lukewarm, independent retail precarious, and high streets can feel more like transit corridors than destinations. Thetford has bucked the mood not by conjuring new shops out of thin air but by tending what it has. “We’ve worked hard on the look and feel,” Mac says. “Cleanliness, removing graffiti, planting. Anglia in Bloom. Focusing on the market. Investing in the Market Square. And, yes, the top of the Guildhall—nobody wanted to pay for it, but it had to be done. These things keep Thetford looking like a market town, not ‘another modern place that used to have history’.”

Events help stitch that identity together: remembrance plays that fill halls, parades that fill streets. Mac is quick to credit the town’s officers who “do the heavy lifting,” but he also admits he takes a special interest in remembrance. “I had a lot to do with last year’s,” he says. “Not because it’s ‘my’ project—because it matters.”

The next decade will test Thetford’s capacity to expand without splitting its personality. The King’s Fleet urban extension—already under way—will triple in size if plans run their course. New homes bring new neighbours, more council tax, more footfall, but also pressure on roads, schools and GP surgeries. Integration, Mac says, is everything.

“People moving in often come from outside—Essex,

London, Cambridge,” he says. “They’ve come for better prices and the forest. We mustn’t end up with a ‘new town’ and an ‘old town’. It needs to knit. Transport routes matter—walking and cycling as well as roads. The £20 million [Towns Fund] will help if it’s targeted well. It’s not the scale of the 1960s London overspill; the money and energy aren’t the same. But the effect on identity will be similar if we get it wrong.”

His plea is simple: whatever your postcode, think of yourself as a Thetfordian. “Wherever you’ve come from, it doesn’t matter,” he says. “If you’re here now, be part of here.”

How he shows up—and what he won’t promise

Not everyone lives online. Mac knows this, which is why he pushed for physical noticeboards on estates— on the Admiral’s shopping area, for instance—listing every district and town councillor’s contact details. “So people can get in touch,” he says. The council has sharpened its social media, too, and he’s not above old-fashioned street corner conversations: “I saw a lady this morning—hope I can help her with an issue.”

He has also learned the discipline of candour. “You want to fix everything,” he says, “and you can’t. So don’t over-promise.” Volunteering, likewise, must be spoken of honestly. “People want good communities. They forget they can play a tiny part. Write minutes. Be a treasurer. Turn up with a bag for an hour. You’ll feel better for it. There’s wellbeing in doing.”

The ledger of time—and the love that balances it

If service is the thread, life is the loom. In recent months, Mac and Sue’s world has been redrawn by a diagnosis: breast cancer. “A routine mammogram— no signs other than that,” he says. The treatment is long; the prognosis hopeful. They are frank about it because frankness feels like a way of keeping faith

with those who care. “It makes you re-evaluate how much time you’re putting into other things,” Mac says. “Everything feels important. But you try to thin down where you can.”

Some things are non-negotiable. Fridays are Pop’s Day with grandson Thomas. “I still find myself answering emails,” he admits, “and I’d really like to turn everything off that day.” Other commitments— he chairs the RAF Regiment’s Warrant Officers’ and SNCOs’ Association, helps steward the Corps’ memorial garden at the National Memorial Arboretum—are being pared back. “Handing over is hard,” he says. “People get used to you doing it. But you’ve got to.”

There is pride, too, in external recognition that mirrors the internal compass. In 2022 Mac was made an MBE—a military award, but for profoundly civic work: years of reconnecting RAF units with their host communities after long operational focus overseas. “I’m pleased I got it for that,” he says. “It speaks to what I’m about.”

For a man who works in risk matrices by day, Mac is oddly romantic about history. Not costumes-andcakes romantic—responsibility romantic. He manages a military museum because he believes in telling a regiment’s story well. He loved working with the War Graves Commission because the way a community remembers its dead shapes the way it treats its living. He worries that Thetford underuses its heritage. “We’ve got four museums in town,” he says. “Most people can’t name all four. Have we taken our kids? Our grandkids? We’ve had the first Black mayor in the country. Where’s the statue? We have statues for other things.”

He doesn’t see such commemorations as “nice to

have.” They are the scaffolding of belonging—and a draw for visitors. “Centre Parcs is up the road,” he says. “Sainsbury’s is full of people getting provisions. They should be coming into town for more than groceries.”

What he owes, who he thanks, and why he laughs

When asked for the biggest influence on his life, Mac doesn’t hesitate: Sue. “She’s kept me on the straight and narrow,” he says. “Encouraged me when I’m not enthused. Reminded me where I should be. Supported me all over the world—and still does.” He describes himself as “at heart a military man” and asks the town not to expect anything less. “Honesty, integrity, service,” he says. “If you wanted a golden thread through my life—that’s it.”

There’s humour there, too—dry, occasionally daft, never unkind. As we speak he is midway through a month-long cancer research challenge: 100 pressups a day. “They want a post on social daily,” he says, fretting about boring the internet. “So I’m trying to think of things to dress up in. You have to keep it interesting.” He knows social media can swallow whole days, so he rationed it to two short windows. “Otherwise I’m two hours later.”

The message he’d leave you with

Who is Mac MacDonald, and why does he serve? He winces at the grandness of the question, then answers plainly. “My whole life has been about service,” he says. “Not as a slogan—just what you do to make something better, not necessarily for yourself.” He believes any town thrives when more people share that instinct. You don’t have to join a committee or run for office; you can pick up a bag. You can be kinder on Facebook. You can look at a place and say, “What’s good, and how do I strengthen

it?” rather than “What’s wrong, and who do I blame?”

He will keep showing up—in the council chamber, at STAG, in the museum, and, yes, with a litter-picker— because showing up is the craft he learned at 18 and never unlearned. “Whether I stay on the council or not, it’ll always be about doing the right thing,” he says. “I could see myself litter picking into my eighties. If I could get paid for cutting back bushes and cleaning road signs, I probably would. You walk away and think: that looks better. You’ve achieved something.”

There are bigger achievements on his CV: NATO awards, royal duties, parades planned, a medal from the King, a daughter raised and a grandson cherished. But the quiet power of Mac’s public life is that it invites others into a scale of action they can imagine themselves doing tomorrow. You can lend an hour. You can write a minute. You can make a street safer by watching a speed gun or a son prouder by keeping a promise. You can, as he did in 1989, hear a good request and say “okay.”

And if you are tempted to believe that one person cannot alter the feel of a town, walk the Market Square on a Saturday. Notice the flowers that weren’t there five summers ago, the absence of graffiti on walls that used to be bilious with them, the way the Remembrance parade feels like something a place does together rather than a ceremony people watch. None of that happened by magic. It happened because people like Mac chose, again and again, to spend their free time not being “free” in the usual sense. They spent it on us.

“Positivity,” he says, when asked for Thetford’s most pressing need. “There is so much good stuff going on.” He’s right. Sometimes we just need a nudge from a neighbour who will both tell us so and hand us a bag.

Written by Liz Gibbons

Sally McDonald (née Trett)

When the Class of ’75 came together for their 50year school reunion, it was a milestone for all, but especially for those seeing each other again for the first time in half a century. For Sally McDonald (née Trett), reunions mean far more than just a night of nostalgia. “The 50-year reunion is the third I have helped organise,” she explained. “I think reunions are undoubtedly great fun, but also an important reminder of our roots. It has been wonderful to celebrate old friendships, re-establish links and ultimately remember the ties that bind us.”

Some of those ties stretch back decades. When Sally moved to Thetford in 1965, her neighbour was Rhonda Johnson (née Bailey). The two girls went through Queensway Infant, Junior and Staniforth Upper schools together, later attending N.O.R.C.A.T., and today their friendship has spanned more than sixty years. “With some friends, you just naturally pick up where you left off,” Sally said. That bond carried them through years apart, Rhonda as the wife of an ex-Warrant Officer, Sally rooted

in Thetford, and eventually back into the shared role of reunion organisers. “It has been great fun, sometimes frustrating but mainly rewarding, tracing ex-pupils and organising the last two reunions with Rhonda,” she added, “always accompanied by plenty of reminiscing, and compulsory refreshments.”

Sally’s circle of school friends has remained strong. She still meets regularly with Jan Selley, Lorraine Emeny and Jan Young, friends who, like her and Rhonda, began their journeys together as fiveyear-olds at Queensway. Over the past ten years, the group has kept up regular lunches, now more frequent than ever. “Being friends for so long means we are totally at ease with each other and are always there to support one another,” Sally said. “At heart, we’re still those same five-year-olds, and we never seem to run out of things to talk about.”

The wider reunions, too, have forged new connections and encouraged mini meet-ups, over lunch, coffee, a pint in the pub, or even just a wave in town. They have also inspired people to travel back

to Thetford from Scotland, the USA, and across the country. “It has to be a great indication of what the reunions have meant to us all,” Sally reflected. Just as importantly, they have provided moments to remember and celebrate classmates no longer with us.

For Sally, these gatherings are about more than looking back. They are a celebration of the years that shaped who and where everyone is today.

When Rhonda moved back to Thetford after years away, she thought many of her old school connections were lost. That changed at the 25-year reunion, where she was delighted to reconnect with so many familiar faces. “It was such a joy to catch up with old school friends after so long,” she recalled. A chance meeting years later provided the spark for another gathering. In June 2024, Rhonda was at a pub charmingly called Five Miles from Anywhere No Hurry Inn. Just as she was about to leave, she heard someone call her name, it was Lynne, an old school friend. “We should have another reunion,” Lynne suggested. The idea stayed with Rhonda. That very night she messaged Sally, and together they began planning what became the 50-year reunion. Tracking down classmates proved challenging, especially the women, whose surnames had often changed. Facebook, Genes Reunited, and even the electoral roll were pressed into service. One of the hardest parts was discovering how many classmates had sadly passed away. Still, on 19th October 2024, around 50 people gathered in Thetford, filling the room with laughter, stories, and memories. By the end of the night, everyone was already asking about the next milestone gathering. Family and career have shaped much of Rhonda’s journey since school. She married into the Army, moving to Germany and adjusting to life away from family and friends. “I really struggled at first with the accents and sense of humour,” she admitted

of her husband’s Liverpool and Manchester battalion. Rhonda still adapted quickly and built friendships that have lasted a lifetime. Back home, she worked for Ford for over 30 years, eventually becoming Group Business Systems Manager with responsibility for 54 dealerships across the UK, Ireland, and the Channel Islands. Her proudest achievements, though, are her two children: Amy, now living in Dublin with her teenagers Harriet and Charlie, and Adam, who lives in Thetford with his young boys Tom and Sam.

School memories bring both laughter and a touch of drama. She recalls a terrifying science experiment gone wrong when a mixture exploded, splashing acid onto her face and uniform. “No one even contacted my parents,” she laughed, “so you can imagine their shock when they got home to find me with half my face burnt!” Thankfully, only a small scar remains. Not all memories were so serious: on cross-country days, Rhonda and friends sometimes slipped into her house in Pine Close, waiting until most of the runners had passed before rejoining the course. On one occasion, she rejoined too soon, finishing near the front, and was promptly selected for the county team!

Like many, Rhonda looks back on the 1970s with a smile. A devoted ‘Bay City Rollers’ fan, she remembers wearing tartan-trimmed outfits to concerts. She also loved her Oxford trousers and Crombie coats. Discipline at school, though, was far less light-hearted. “Most of the boys admitted to receiving the cane or slipper from Mr. Briggs or Mr. Hull at some point,” she said. “There was definitely a stronger sense of discipline and respect for teachers back then.”

Reflecting on how the world has changed, Rhonda sees her generation as one that has adapted to extraordinary shifts. “We grew up without the internet or mobile phones, and now both are part of everyday life,” she said. She also values how society has opened up around issues like equality, diversity,

and mental health, things rarely spoken about in their school days.

Above all, she feels grateful. “It’s been truly wonderful reconnecting with so many old friends after all these years,” she said. “The friendships we shared back then have taken on new meaning now, there’s something really special about picking up where we left off, but with the perspective and warmth that comes from experience.”

Alongside the evening itself, a short questionnaire was sent out ahead of the reunion. The replies received give a fascinating glimpse into the lives of classmates since leaving school. One respondent, who wished to remain anonymous, shared a story filled with travel, sport, and unexpected turns. When asked if he married a classmate, he revealed that he did not but in fact married a girl from a younger year. Together they raised two children and now enjoy two grandchildren. His career took him into transportation and shipping, working in countries across the globe. “I gained confidence and worked in a number of countries,” he explained, recalling highlights such as time spent in Kuwait. Alongside his career, sport played a central role. Twice East Anglian karate champion in the 1980s, he also taught the discipline, eventually being invited to run classes at UEA and Wymondham College. He captained the university rugby team, too, and remains proud of having pursued education through night school to achieve his goals. In retirement, he’s discovered new skills, enjoying cooking and gardening.

When asked about his school memories, he recalls “the cane on a number of occasions” and the prediction from a teacher that he “wouldn’t make anything” of himself, something he’s clearly proved to be quite the opposite. His favourite teacher, though, was remembered fondly: “Mr Llewellyn, by a country mile.”

Reunions, he said, were a chance “to see everyone”, though he admitted he had not stayed in touch with school friends over the years and no longer felt deeply connected to his hometown. Yet, looking around at the gathering, humour and fun were the strongest emotions.

Looking ahead, he hopes to keep travelling, Japan remains high on his bucket list. “I love the clothes, cars and music of the ’70s,” a reminder that some passions never fade.

Janice Butler (née Selley)

Janice reveals that she never dated anyone from school and has no children or grandchildren, but her life since leaving has been full of change and achievement. She married, studied for a Business Management degree, and enjoyed a career in financial accounts, office management and international credit management. She is especially proud of how her studies helped her rise through her profession, and of the home she and her husband owned in Spain for 11 years, mortgage-free, before selling it so she could retire early.

Travel has featured strongly in her life, with cruises and holidays in many countries, but her most unusual passion has been exploring graveyards as part of three decades of genealogy research. She jokes: “I investigate dead people…!” In retirement, she has embraced new skills and hobbies, from woodworking, quilting and ornament restoration to photography and gardening. “Driving hubby mad with my obsession with all things wood,” she laughs. School memories are mixed. She recalls being taught to swim by a stand-in teacher in the last term and admits she was often the target of bullying: “I was the very shy, quiet, tall, skinny kid that everyone sniggered at. Now I am much more self-confident and often seen as quite gregarious.” She still meets up with three school friends every five or six weeks, though she has tried in vain to reconnect with two others.

•

•

•

•

•

•

Reunions, she says, are a chance to “reminisce and rekindle friendships that could, or should, have continued after school years.” While she disliked much about school at the time, she now finds joy in seeing classmates again, both the “nice” ones she remembers fondly and in overcoming her “long-held dislike of the nasty kids.”

Looking back, Janice believes her generation had more opportunities than those before them, though she laments the decline in self-respect and respect for others since school days. Looking forward, she wants more of what she has enjoyed since retiring: time to enjoy life, recoup her pension contributions, and tick a few more things off her bucket list, like riding a jet ski and mastering a dovetail joint. Her message to classmates is simple: “I disliked school and many of its pupils, but here I am; loving the reminiscing which makes me appreciate my own journey and where I’ve ended up. I do hope many of you can say the same.”

As the evening drew to a close, it became clear that this reunion was more than just looking back, it was about strengthening ties for the future. “One of the loveliest outcomes”, Rhonda reveals, “has been the creation of a Facebook group, Staniforth Class of 1975, where classmates can continue sharing stories, photos, and memories.”

Reunions remind us that while time may have passed, experiences and bonds formed in our childhoods are a part of who we are. Whether through laughter over old stories, remembering those no longer with us, or simply exchanging a smile across the room, each moment has shown how much the Class of ’75 still means to one another.

So, here’s to friendships old and new, to the memories that shaped us, and to the chapters still to come. Until the next time, cheers to the Class of ’75!

Photography, high jinks and words by Bob

Blogg

Firstly: The Medusa Trail

Afew issues ago, we took our mobility scooters on a road trip to Warren Lodge to test their off-roading abilities and just to see if we could get into the forest by that route.

We could! But far from fulfilling our wanderlust, it has just cranked it up.

Right, we decided, these sissy cyclists have got their routes in the forest, so why can’t we have one for our mobility scooters?

They have got the Shepherd Trail (green), graded easy, suitable for families and kiddies; the Beater Trail (blue), graded moderate, a basic mountain bike track with the odd tree root in the way; and the Lime Burner Trail (red), graded as difficult, featuring dropoffs and rocks, and not suitable for child seats and tagalongs.

Pah - amateur stuff!

We created the Medusa Trail (purple) for mobility scooters, graded as insane, and featuring grass, gravel and bullets.

Also, where all the cycling trails at High Lodge just go around for several miles in boring loops, we go to the pub!

We start at Warren Lodge, duck around the Thetford Rifle Range and onto fire-road 7 and out at the B1106 and into Elveden.

It’s just under 5 miles, according to the maps we looked at, and do-able on scooters as far as we could tell according to Komoot, the route planning app for hikers and cyclists. The only uncertainty is the exit at the end of fire road 7.

We can’t be sure if our scooters will squeeze out onto the B1106 until we try.

So, without further ado, we set off from Warren Lodge on our grand adventure, having got there by whizzing over the A11 with such familiarity that it was almost like a daily commute.

Our scooters got up the hill, across the sand and into the forest at the hurry up.

We then settled in for the first part of our journey: a straight drive down the path from the Lodge to the entrance to the Thetford Rifle Range. At least that’s what it was according to the Map.

This section was about a mile along a wide avenue with dappled shade, criss-crossed with the odd cycle path and smaller trails.

We had to make a slight detour when the path reached a fenced-off area that forced us to turn right and zig-zag for a bit, but we safely reached the rifle range with my camera only falling over once!

From there we set off alongside the rifle range on fire-road 10. This section is a gravel sea and very noisy.

It eventually reaches the Shepherd Trail cycle route and becomes much quieter and grassier.

From there we pressed on, and at one time we reached the junction of fire-roads 9 and 12. It was the first, and probably the only time that we knew where we were in the forest!

We then had a drag race, and we now know for sure which of our mobility scooters is the fastest. One of us is not a very happy bunny!

After all this excitement, we got lost and went for the best part of a mile in the wrong direction.

Eventually, we pulled ourselves together, found fire road 7 and escaped onto the B1106. We then raced down to the Elveden Inn and had a well earned beer or two.

It is a hell of a trip. If you are adventurous and up for a challenge, I strongly recommend that you try this route.

You are out in the middle of nowhere, exploring new grounds, and with no real idea where you are. It’s true escapism.

The tricky bits are just getting to the start point at Warren Lodge and the end point at the Elveden Inn. These are the road sections and they require confidence and certainty.

The forest is the orangey bit in the middle – so go for it!

Scan the QR code below to explore The Medusa Trail

Tiglet, my faithful boot scooter, had a ‘Doctor Who’ moment and has been reborn.

He got a bit tired of all the abuse he was getting so, after his last journey to the museums in London, he decided enough was enough. His batteries were faltering and his wheels were weary. It was time for a change.

With a big grin, he morphed into a full-on T-Sport X05 Auto-fold mobility scooter!

And what better way to celebrate his rebirth than having yet more Thetford retail therapy.

Anyway, as a birthday present, I wanted to get him a cup holder so off we went to Halfords.

Halfords is a great shop to take your mobility scooter into. The entrance is easy, even on a big scooter, and the aisles are quite wide. The only down side is the bicycle section.

It’s upstairs and there is no lift, escalator, or funicular railway option – yet!

The staff told me they hope to have a lift sometime in the future.The good news is that I did find him a cup holder.

Next on my shopping list was a chew toy for my friend’s dog, Paddy.

And, conveniently enough, Jollyes is right next door to Halfords.

Still sitting dreamily on my reinvigorated Tiglet, I went to get the dog a bone so to speak.

I soon ran into a problem: Jollyes have got a great big, wide, automated door, like Halfords, but they haven’t got direct wheeled access.

They have got a gigantic kerb in the way and car parking right in front of the door?

If you want to get in, you have to squeeze onto the narrow strip of paving either on the left or right of the doorway.

To further hinder you, there are shopping trolleys on the left and flatbed trolleys on the right.

Alternatively, if you have a good road scooter, you can just ram-raid the kerbed entrance, providing there isn’t a car in the way!

However, I did make it into the shop eventually. Once you’re into the shop there is plenty of room to drive around on a mobility scooter, even a road scooter. It’s a great fun shop to run around’ A toy shop for pets, well their owners really, and I got Paddy a peanut butter rubber bone!

Next on my shopping list were chips. I wanted frozen microwave chips because I’m lazy and I haven’t got a chip pan.

And next door to Jollyes is Farmfoods.

The first thing to say is that Farmfoods hasn’t got an

automated door. They have got two narrow doors, and one was bolted closed. Tiglet had terrible trouble getting through the door and it was through the help of a customer, who unbolted the second door that I managed to get in.

Secondly, there is the same access problem as Jollies before you even get to the door: A big kerb with cars in the way; and shopping trolleys blocking the narrow pavement.

Once inside the shop, you can get about the aisles alright on a little scooter, but you certainly couldn’t get a pavement scooter around.

The bad news also was that they had sold out of my favourite brand of chips, so I had to have a healthy lunch!

So, come on Jollyes and Farmfoods put a ramp on the kerb outside your front doors. It’s not rocket science, it is called common sense.

My Lucky Rat I have just got a last minute thing to add – it’s not really retail therapy. I wanted to tell you about my lucky rat!

A few weeks ago a huge rat invaded my flat. I was terrified. It was running around eating everything, including my window frame. I think he ate himself out of house and home in the end.

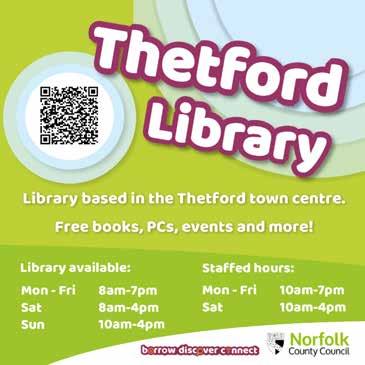

My landlord came around and rebuilt the frame and we got talking. He told me about the Pressreader app that Thetford Library gives you access to, so that you can read newspapers and hundreds of magazines online for free.

As a result, I was reading the New Scientist magazine (which I love and always used to read when I worked

for the BTO) when I saw the New Scientist Live 2025 event advertised.

It’s my seventieth birthday next month and thanks to that rat and Thetford Library, I am now going to the event at the Excel Centre in London. Thanks Ratty.

Shopaholics, scan the QR code here for a quick fix! The X5 Files and Retail Therapy

Finally: High jinks at High Lodge.

Right! It’s easy everybody said.

Phone up High Lodge and book their mobility scooters for the day.

And, as my antipodean friends would say: ‘no wucking furries!’

They mucked it up big time.

We got there at 12; they said we were expected at 9; we said we had booked 2 scooters from 12; they said we had booked them from 9 until 12, we said can we have our scooters please?; they said no you can’t; we said why not?; they said because you’re late so you

can only have one; we said you couldn’t organise a p£$$%% in a b£$%^; they said sign here...

So we did.

Now let me clarify things.

We had phoned up High Lodge and arranged to hire their two mobility scooters for the day a while ago. It was arranged and timed.

We had done it two weeks in advance because we wanted both scooters and we were told that would ensure the deal. I had even spoken to them a few days prior to that because someone else had phoned me up asking if I had had a response to the query that I had left on their answer phone a fortnight or so ago?

That should have rang an alarm bell!

That’s why we only had one scooter.

We knew their second scooter was a TGA Breeze S4 just like Adrian’s – so no big loss there!

But the other scooter was/is (never too sure about grammar tenses) a MK2 Tramper.

This is a serious, no nonsense, off-roading mobility scooter used by farmers and the like.

It even has bull-bars for heaven’s sake!

Me and Adrian just wanted to get our hands on it and give it a serious test drive.

Anyway, we did get our grubby hands on it eventually but not quite how we envisage.

We couldn’t follow each other around and one of us

NMV Sweet & Savoury

& Desserts

At NMV Sweet & Savoury, we create stunning wedding cakes, birthday cakes, and custom cakes for any occasion. Our menu also includes French mousse mini cakes, desserts, and appetizers, perfect for adding a touch of elegance to your celebration. Delivery available.

Visit us online: www.nmvsweetandsavoury.co.uk

Follow us on social media: Facebook @nmvsweetandsavoury

Instagram @nmv_sweetandsavoury 07936 612846

had to sit and watch while the other was racing around.

You can see Adrian having fun and watching in the photo below!

Despite all that, the Tramper is a serious piece of kit. It is one of the best built, most robust and strong mobility scooters I have ever seen. Its ground clearance is huge – you could drive it over a large sack of potatoes.!

The wheels are enormous, its footplate is solid metal, its lights are big and bright, and its controls and dashboard clear and easy to use.

We were severely limited with how we could test it because we couldn’t follow on another scooter. So we did the next best thing and drove it straight across all obstacles from our position in the car park to the information point in High Lodge. It didn’t miss a beat.

So, how fast is it? We have no idea. High Lodge or Forestry England to use a broader term has done their best to cripple it.

The Tramper is a beautiful mobility scooter, one of the best that Adrian and I have ever seen, and will do 8mph minimum and more probably.

The lame beast we hired in the forest could barely make 1mph. We suspect this is partly because of health and safety, and mainly because of the fear of litigation.

The MK2 Tramper is a phenomenal mobility scooter, it needs to be delimited and let loose, and I want one.

Scan the QR code on the right for some high jinks at High Lodge.

Happy Scootering!

Written by Martin Angus

Every morning, except Sundays and bank holidays, if you walk through Thetford’s market square you’ll see them. Two old boys, side by side, watching the world go by. They’ve become such fixtures that strangers notice their absence before their presence. “If one of us isn’t there,” Trevor Kenny chuckles, “folk come up and ask if the other’s dead.”

They laugh, but there’s truth behind the joke. Thetford’s heart beats a little differently without Trevor and Graham posted up on the corner. For over seventy years, the two have been inseparable. Born in Thetford in the mid-1940s, they met at Norwich Road School in 1950. “We used to look at the old buggers standing on the square,” Graham admits with a grin. “Now we’ve become them.”

This is their story—and through it, the story of a town.

Who Are Trevor and Graham?

Trevor Kenny was born on St Margaret’s Crescent, just off Bury Road. Graham Fayers first saw daylight on Wells Street. Both are 80 now. They’ve watched Thetford change in ways that would astonish anyone who only knows the town of supermarkets and bypasses.

When they started school, there was only Norwich Road unless you passed the eleven-plus and went to grammar. Thetford was smaller then, tighter-knit. “Everybody knew each other,” Trevor recalls. “And if anything went wrong, everyone knew about it.” The market square was the heart of it all.

Over the decades, they’ve seen buildings rise and fall, pubs turn to flats, and the old dances disappear. But they’ve stayed. “There used to be more of us,” Trevor says. “My brother, Tommy Peck, John Waldron… they’re all gone now. Two big ones gone. Now it’s just us.”

In that loss is part of the reason they stand there.

The question everyone asks: why do two octogenarians make the daily pilgrimage to the same spot? The answer is deceptively simple.

“If I don’t come,” Graham says with a mischievous glint, “my family think I’m dead.” It’s partly a joke, partly true. Their daily presence is a check-in with the world.

“You’d be surprised how many people we see every day. Same faces. Some we don’t even know their names,

but they stop and talk. Ask after the other if one’s missing. Where else are we going to go? You can only go shopping so many times.”

They stand there to watch life unfold: kids on their way to school, shopkeepers setting up, tourists lost and asking where Castle Hill or Dad’s Army museum is. “We’re like unofficial tourist information,” Trevor says. “We’ve probably made that museum a fortune.”

They stand there for the laughs too: “We’ve seen a big blow-up screen for the King’s Coronation take off in the wind, a leaf-blower chasing the same leaves in circles, lorry drivers asking directions to streets they pass every day. You couldn’t make it up.”

And maybe, most importantly, they stand there because someone has to bear witness to the life of the town. “We see the town going downhill,” Graham laments. “Very fast. We talk about what’s happening, what’s not happening. The memorial’s been without its chains for nine months. People walking over it. No respect. We notice these things.”

The Market Square as a Stage

Listen to Trevor and Graham long enough and the square comes alive as a theatre. They recall fights outside the Angel and Dog & Partridge when paratroopers came in on Saturdays. They remember where they were sitting when news of JFK’s assassination reached them—in the window of the Red Lion pub.

They point out where Mrs. Ellison sold sweets out of her front room, where the red phone boxes stood, where “Dinger Bell,” the local bobby, kept watch and occasionally pulled a prank. They laugh about the sergeant who barked at Graham to “get in that gutter, son,” and got a dressing down from Graham’s dad. It’s more than nostalgia; it’s living memory of a town that has always been in flux. They’ve seen London overspill families arrive in the late 50s and early 60s, worked at

The corner of Thetford Market square has a long history of being a place of social gathering.

Photograph circa 1920, from The David Osborne Collection - by kind permission of Joy Osborne.

some of the factorys who employed hundreds, locals and migrants alike side by side. They’ve watched small shops disappear, replaced by empty flats and chain stores. They grumble about Amazon hollowing out the High Street and banks closing branches. “They don’t want people like us. We ain’t got any money any way,” Trevor shrugs.

But for all their complaints, they remain stubbornly, lovingly present.

A Social Lifeline

Trevor and Graham aren’t just passive observers. Their corner has become a social hub, a lifeline not just for them but for others. A Polish girl newly engaged stops by to share her news. A Turkish couple bring them smiley faces. Children wave from across the street.

“We talk to everyone,” Graham says. “Little foreign kids born here, old locals, tourists. It doesn’t matter. If you