Sofia Stroe

Senior Thesis | 2025

Sofia Stroe

Ms. Kamen

Senior Thesis

3 March 2025

Expanding the Frame: Diversifying the Female Figure in Art Nouveau

From the 1880s to World War One, the artistic style known as Art Nouveau bloomed in western Europe and the United States. It developed from the Arts and Crafts movement, which was an artistic movement emerging from the most industrialized city in the world at the time: Victorian era England. The Arts and Crafts movement sought to improve decorative designs that had been reduced in quality because of machinery.1 Art Nouveau designers strived to blend fine and applied arts together. Their works took many forms, including decorative furniture, accessories and graphic work. The period took lots of its inspiration from nature, pushing back against the industrial world of the time and returning to handcraftsmanship and traditional techniques.2

Another aesthetic style that had a major impact on Art Nouveau was Japonisme, emerging in the mid-19th century following the expansion of trade between Japan and the West. Japanese art flooded western markets, mainly in the form of Japanese genre painting: Ukiyo-e (“floating world”) woodblock prints. Ukiyo-e artists focused on depicting the preferences of the general public, with common subjects being kabuki actors, famous courtesans, and romantic interactions. Other subjects were contemporary affairs and fashions of city life, both indoor and

1 Monica Obniski, “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–).

2 Cybele Gontar, “Art Nouveau,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–).

outdoor. Art Nouveau designers were attracted by the flat colors, linear perspective, and planar qualities of Ukiyo-e prints.3 Plant and insect based designs on decorative objects from Japan such as ceramics and textiles also played a role in shaping Art Nouveau objects, including jewelry, furniture and glasswork.4

In 1862, Japanese art appeared in London’s World Exhibition, and visitors were able to purchase Japanese art from the exhibits.5 France was influenced slightly later, with many Parisian artists inspired by Japanese art. Émile Gallé, an Art Nouveau glass artist, founded the school “École de Nancy” in Nancy, France. In 1885, a Japanese botanist named Takashima went to study in Nancy, and there became friends with Gallé. Tschudi Madsen believed that Takashima’s presence helped increase interest in Japan and Japanese art in the Art Nouveau realm.6 Japan’s artistic influence on Art Nouveau created a break from European design seen earlier in the 19th century–Neoclassical, Neo-Baroque, and Gothic Revival–allowing designers to part with past conventions and create art more fitting to modern life.7 Now, text and image were fused together, a style that had only previously been seen in medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Alphonse Mucha, a Czech Art Nouveau artist, was heavily influenced by this fusion, and Japanese art generally, in his illustrations and advertising posters. Mucha’s art has similar subject matters of everyday scenes like natural settings and candid portraits, as well as their bolded outlines, detailed designs and floral motifs. All these elements come into play in one of Mucha’s

3 Department of Asian Art, “Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–)

4 National Gallery of Art, Art Nouveau: A Research and Teaching Packet (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, n.d.), 7.

5 Tschudi-Madsen, Stephan. Art Nouveau, 58. McGraw-Hill, 1967.

6 Ibid., 59.

7 National Gallery of Art, Art Nouveau: A Research and Teaching Packet, 6.

posters advertising a luxurious holiday location on the Mediterranean Coast, “Poster for ‘Monaco - Monte Carlo’, P.L.M. Railway Services” (fig. 1). At the top of the poster, in clearly bolded and stylized letters, reads “Monaco・Monte-Carlo,” the vacation destination in question. The very background of the poster consists of a blue sea and mountainous coastline. The female figure in the center holds her hands to her face, looking at the sky in wonder. She is captured in a seemingly candid position, lost in thought. Her clothing seems simple, wearing just a white dress with an orange scarf wrapped around her torso. Despite the outfit’s simplicity, it is detailed with many folds, indicating a soft fluidity of her fabric. She is surrounded by curling stalks and rings of four flowers: violet, hydrangea, dianthus, and lilac. The flowers are arranged with care, condensed together to create detailed patterns circling around the central figure. Such elements are part of the inspiration for my own artworks.

I created seven art pieces for my senior thesis: three paintings and four drawings. The drawings were four designs of decorative accessories. The decorative accessories comb, hand mirror, brush, and brooch were created to increase the confidence of women who used the items. All four designs were colored with alcohol marker, to keep the design lines clear and the colors flat. The three paintings are each in a different style of an influential Art Nouveau artist. Women in Art Nouveau art are typically only portrayed one way: white women with an hourglass figure. I chose to paint only women of color with different body types, to create representation for more women and show every woman they are beautiful as they are.

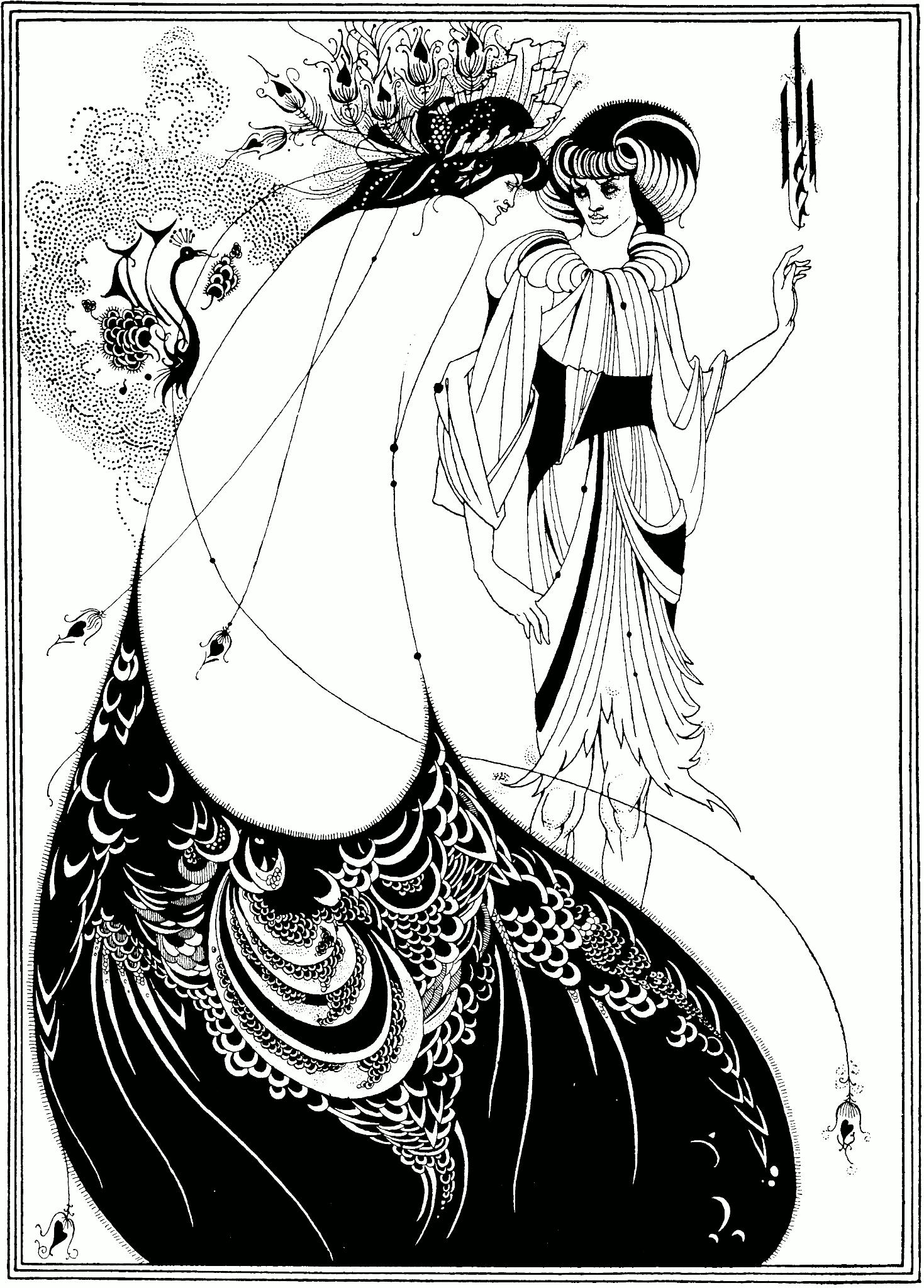

The first woman I painted was in the style of Aubrey Beardsley, using black ink to imitate his illustrations. The clothes his women were drawn in were extravagant, composed of big shapes filling the canvas. I took specific inspiration from his piece “The Peacock Skirt” (fig. 2). In addition to his large, swirling shapes, there were also thin lines and detailed natural forms, all in

black and white. I took these elements as inspiration for my own piece. The skirt of the woman on the left reminded me of Tehuana dresses, beautifully embroidered traditional Mexican dresses patterned with colorful flowers, such as dahlias and marigolds. For this reason, I decided to portray a Mexican woman in a Tehuana dress for my Beardsley inspired piece. I chose to draw her with a thin, lean body type to combat the popular stereotype that Latina women are only curvy. Her dress is decorated with poppies, which are flowers associated with sleep, comfort, and calmness in ancient Greek mythology.8 She is standing to the left of the canvas, gazing at the stock flowers on the right. Stock flowers were a symbol of happy life and contented existence during the Victorian era, so their placement being in her direct line of view represents her content with her existence and therefore, her body.

The second painting I created was inspired by Alphonse Mucha, a Czech artist known for his Art Nouveau posters. I used gouache paint to imitate the matte, opaque finish of Mucha’s posters, and because gouache paint layers easily on itself which allows for outlines as in Mucha’s art. Mucha was inspired by Japanese art and culture, so I painted a Japanese woman in his style for this reason. I made her plus size due to the lack of Japanese plus size representation, and as a form of resistance to Japan’s harsh body standards. In Mucha’s piece “Poster for ‘Gismonda,” the woman depicted is wearing a gown that almost resembles a kimono (fig. 3). The neckline of the gown is in the shape of the letter ‘v’, resembling the ‘v’ shape that is created when wearing kimonos and folding one part of the cloth over the other at the chest. The woman’s gown also has a high waistband and triangular sleeves, similar to kimono sleeves and the obi, a sash worn around the waist. I painted a woman wearing a yellow kimono with sakura flowers on it, the national flower of Japan.

8 Chahine, Nathalie. The Little Book of the Language of Flowers, 58, 126. Paris: Éditions du Chêne, 2018.

They are also a symbol of nature and the beauty in the fleeting moments of life. The woman in my painting is also holding a package wrapped in a traditional Japanese wrapping cloth known as furoshiki. She is standing in a snowy scene, inspired by Mucha’s “The Seasons: Winter” (fig. 4) print. I took specific inspiration from the pastel color palette, bringing in the pastel pink and purples in his piece into my own. I also took the shape of the snow-capped bush as the inspiration for the tree. The reference I used for the Japanese woman’s body was my own, which I also referenced for my third painting.

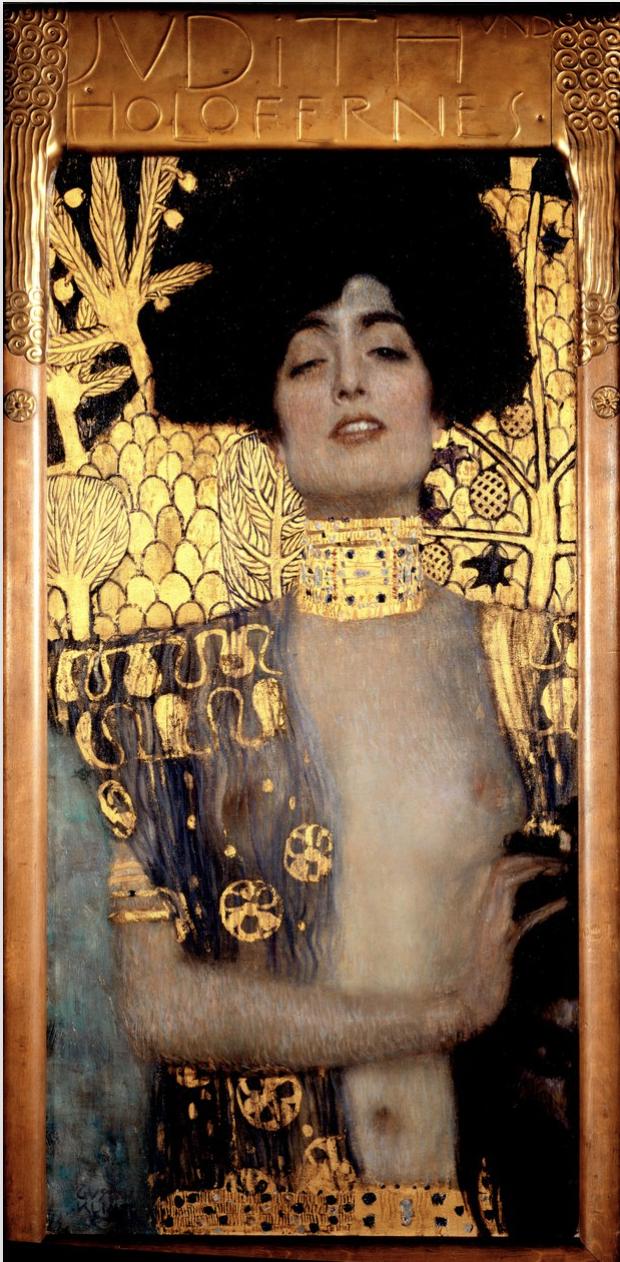

The third piece was a gouache painting of a plus size black woman in the style of Gustav Klimt, another famous Art Nouveau artist. I used gouache paint for this piece to imitate Klimt’s opaque and distinct colors in his pieces. Among plus size representation in media, I have noticed there is typically one body shape depicted. In my piece, I wanted to combat the usual hourglass depicted and give light to bodies of all shapes. I took inspiration for the composition for my piece from Klimt’s “Judith and the Head of Holofernes” (fig. 5). I drew the woman in my artwork with an afro and a layered gold choker necklace, alluding to Judith’s hair and choker. I chose to paint trees in the background, inspired by the golden trees behind Judith. Instead of straight branches, I used the swirling branches of Klimt’s “The Tree of Life, Stoclet Frieze” (fig. 6) in the background and on the woman’s dress. The grass and abstract flowers’ inspiration comes from Klimt’s “The Kiss,” and I put black and white rectangles from the man’s clothing on the dress of the woman. Her dress is also adorned with triangles filled with diamond and zig-zag patterning. This is a call to both the diamond patterning on the dress of the woman in Klimt’s “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” (fig. 7) as well as Ghanaian Kente cloth. It is a traditional fabric woven from strips of colorful silk, cotton yarn, or rayon. It has become a symbol of national identity, expressing a Pan-African identity and connecting individuals who wear Kente to Ghana and even the continent of Africa. Kente is

used on special occasions to mark ceremonies, such as during Kwanzaa celebrations.9 Akan Kente cloth is colorful, adorned with geometric patterns such as triangles, rectangles, and zig-zag patterning.10 Ewe Kente cloth is also colorful and geometric, but also incorporates zoomorphic and anthropomorphic elements.11 Early cloths from the 13th century were done in black and white, but now have incorporated other colors. Each element and color has a specific meaning used to tell certain stories. Each color in Kente cloth has a unique significance. In the town of Bonwire, yellow, the main color of my muse’s dress, represents royalty, preciousness, wealth, and fertility. Bonwire weavers also associate pink, the color of several of the flowers in the background, with the female essence of life as well as sweetness and serenity. I chose these colors to highlight the woman’s elegance and femininity, telling the audience that all women and features are beautiful.12

The first two designs created out of the four decorative accessory designs were the hand mirror and brooch. The mirror has classic Art Nouveau swirling motifs, adorned with dogwood and calla lily flowers. It is colored yellow with green accents, to imitate the look of slightly tarnished gold-plated brass. Gold and silver were popular materials used in Art Nouveau jewelry, as well as cheaper materials such as copper and brass to make jewelry more accessible to customers. Calla lilies symbolize beauty, purity, and femininity. Sigmund Freud saw a sensual shape of the female body in the flower, which popularized the flower among artists of his time.13 The other flower on the mirror is dogwood. In Victorian

9 Atsutse, Kennedy, and Wazi Apoh“A Study of the Akan and Ewe Kente Weaving Traditions: Implications for the Establishment of a Kente Museum in Ghana.” In Current Perspectives in the Archaeology of Ghana, edited by Wazi Apoh, James Anquandah, and Benjamin Kankpeyeng, 222. Sub-Saharan Publishers, 2014.

10 Ibid., 231.

11 Ibid., 232.

12 Ibid., 234.

13 Chahine, Nathalie. The Little Book of the Language of Flowers, 18.

floriography, dogwood was used to symbolize love overcoming adversity.14 In my design, the love that will overcome all trials is meant to be self love, the dogwood flowers serving as a reminder to the user to love themselves just as they are.

The spider lily brooch was drawn to look like it is made of enamel and small pearls on the ends of the stamen, as well as pearls in the middle of the flower to symbolize the beauty of nature. In Japan, spider lilies are commonly known as the flower of death. The most common variation of this flower is red, but other color variations have different meanings associated with the flowers. Pink spider lilies are often associated with femininity, beauty, and grace, and are given as a gift to express admiration and love.15 I chose this flower to remind the wearer of not only their own grace, but also the beauty in the circle of life and new beginnings. I designed my pieces with natural materials to display Art Nouveau’s emphasis on rejecting industrialization.

The brush and comb were the third and fourth designs, and they are meant to be considered as a set. The brush is colored grey and blue to resemble silver, adorned with magnolias and snowdrop flowers. The comb is made of tortoiseshell, decorated with purple orchids and curling stems made of enamel. I was inspired by one of Eugene Grasset’s snowdrop Art Nouveau designs, and incorporated the shape into the brush design (fig 8).16 Snowdrops symbolize consolation and hope, and are seen as a sign that better days are coming.17 Magnolias are a symbol of dignity in

14 Roux, Jessica. Floriography: An Illustrated Guide to the Victorian Language of Flowers, 60. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2020.

15 Writers, Staff. “Meaning of Spider Lily: The Symbolism of Spider Lilies.” GFL Outdoors, September 22, 2022.

16 Grasset, M. Eugene (Ed.) La plante et ses applications ornementales. Second series, 34. Paris: Librairie Centrale des Beaux-Arts, c. 1898

17 Roux, Jessica. Floriography: An Illustrated Guide to the Victorian Language of Flowers, 158.

floriography, and a symbol of beauty and sensuality in China.18 19 Orchids symbolize elegance and beauty, and they are seen as a sign of luxury as only the wealthy could afford orchids in Victorian times.20 Due to their suggestive appearance, orchids also became a symbol of fertility, seduction, and female sexuality in ancient Greece.21 I decided to make the comb and brushes a set because in floriography, the combination of magnolias and orchids create a gift for someone the buyer admires.22

The inspiration behind my senior thesis came from a personal place. The women in my life around me have all been insecure about their physical appearance at some point in their lives, even as young as eleven. Though I have been guilty of this as well, I have been trying to become kinder to myself as I go through life. As an artist, my eye finds beauty in every corner of my everyday world–especially in the people around me. I see my baby brother in Rococo paintings of cherubs and my mother in Mary Cassatt’s paintings. Although I see beauty in the insecurities of my beloved ones, it is often hard to see that in myself, perhaps partially due to the lack of representation of bodies like mine. I decided to create this representation for myself and others through my thesis, using my own body as a reference for two of my paintings. I know the euphoria I feel when I see women that look like me in artwork, so I hope to invoke the same euphoria in others when they see my work. In a life where time never stops, we

18 Ibid., 112.

19 Othoniel, Jean-Michel, and Raphaëlle Pinoncély. The Secret Language of Flowers: Notes on the Hidden Meanings of Flowers in Art, 83. Edited by Benjamin Carteret, Pieranna Cavalchini, Anne Levine, Diana C. Stoll, and Anne-Sylvie Bameule. Translated by John Paul McDonald and Molly Stevens. Boston, Arles: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum ; Actes Sud, 2015.

20 Roux, Jessica. Floriography: An Illustrated Guide to the Victorian Language of Flowers, 134.

21 Chahine, Nathalie. The Little Book of the Language of Flowers, 124.

22 Roux, Jessica. Floriography: An Illustrated Guide to the Victorian Language of Flowers, 112, 134.

should not live our lives in despair, hyper-focused about the way our bodies look. We should focus on the beauty of life and wonderful memories we make with the people we love before they pass right in front of us.

Works Cited

Atsutse, Kennedy, and Wazi Apoh. “A Study of the Akan and Ewe Kente Weaving Traditions: Implications for the Establishment of a Kente Museum in Ghana.” In Current Perspectives in the Archaeology of Ghana, edited by Wazi Apoh, James Anquandah, and Benjamin Kankpeyeng, 222–42. Sub-Saharan Publishers, 2014. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvk3gn0j.19.

Chahine, Nathalie. The Little Book of the Language of Flowers. Paris: Éditions du Chêne, 2018.

Department of Asian Art. “Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plea/hd_plea.htm

Gontar, Cybele. “Art Nouveau.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/artn/hd_artn.htm

Grasset, M. Eugene (Ed.) La plante et ses applications ornementales. Second series. Paris: Librairie Centrale des Beaux-Arts, c. 1898

National Gallery of Art, Art Nouveau: A Research and Teaching Packet (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, n.d.). https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/Education/learnin g-resources/teaching-packets/pdfs/Art-Nouveau-tp.pdf.

Obniski, Monica. “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acam/hd_acam.htm.

Othoniel, Jean-Michel, and Raphaëlle Pinoncély. The Secret Language of Flowers: Notes on the Hidden Meanings of

Flowers in Art. Edited by Benjamin Carteret, Pieranna Cavalchini, Anne Levine, Diana C. Stoll, and Anne-Sylvie Bameule. Translated by John Paul McDonald and Molly Stevens. Boston, Arles: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum ; Actes Sud, 2015.

Roux, Jessica. Floriography: An Illustrated Guide to the Victorian Language of Flowers. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2020

Tschudi-Madsen, Stephan. Art Nouveau. McGraw-Hill, 1967.

Appendix A

Figure 1. Poster for ‘Monaco - Monte Carlo’, P.L.M. Railway Services, Alphonse Mucha, 1897, Color lithograph