Costa Gay-Afendulis Roads Not

Senior Thesis | 2025

Costa Gay-Afendulis

Senior

Thesis

January 17, 2025

Roads Not Taken: The Legacy of Boston’s Unbuilt Urban Freeway

As a BU student walks down Commonwealth Ave from East Campus to West Campus, or a biker enjoys the view from the Memorial Drive mixed-use path, or a group of Cambridge residents explore Central Square on foot, Boston presents itself as a city built for people instead of cars. These three locations seamlessly intertwine into the rest of Boston’s fabric, however, they also all intersect an imaginary line cutting through the Boston area that would have changed the city forever. There is a world, which was only narrowly avoided, in which Cambridgeport’s dense row houses and diverse background would no longer exist. The aforementioned people-friendly spaces would be relics of the past, because in this world, Boston would have sent a clear message for the opposite point of view; that cars should take precedence over people. In just that neighborhood, almost 1235 homes and thousands of community members would have been removed so that the space could be occupied by a hulking piece of automobile infrastructure1. Cambridgeport was only one of many neighborhoods threatened by immense damage. It serves as a window into the mass destruction and displacement that could have been a reality in swaths of Boston, such as the South End, Roxbury, and Somerville. This piece of infrastructure that would have brought this damage was the Inner Belt, a highway that would have permanently altered the fabric of Cambridge and Boston.

1 Robert Samuelson, “Cambridge and the Inner Belt Highway: Some Problems Are Simply Insoluble: News: The Harvard Crimson,” The Harvard Crimson, June 2, 1967, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/6/2/cambridge-and-the-inner-belt-highway/.

In the 1950s, Boston’s mayor John Hynes wanted a “New Boston”. This involved a greater drive to build housing, clear slums to boost the economic life of the city, and provide new transportation options, a spirit that would be a contributor for the push for the Inner Belt highway2. Boston developed the Metropolitan Master Plan in 1948, an outline for eight highways in the Greater Boston Area that would connect the suburbs to the inner city3. The city had fully embraced the automobile. Highways and the growing technology sector enabled an entirely suburban life for wealthy Bostonians who would otherwise live in the inner city. Boston was far from the only city with this ideal. In the PostWar era, the American strategy around cities changed as part of the New Deal. No longer were cities places for natural growth and development; urban spaces needed to be pruned, revitalized, and optimized both for citizens and for the country’s own cosmetic needs. This also came from a desire for greater efficiency, a desire that was satisfied by the Federal-Aid Highway act. Highways were both a way to clear slums, or “blighted” areas of cities, and also a way to serve richer residents who wanted to move to the suburbs.4 Crucial to Boston’s plan was one highway in particular: one that would relieve the expected congestion on the central artery, and instead be a ring road to provide an alternate route to bypass the center city. However, this highway was unique because it bisected more densely populated areas of the city. As soon as the central artery was built and proved to be even more congested than

2 Courtney Humphries, “Reversal of Fortune?,” Boston Society for Architecture, January 2020, https://www.architects.org/stories/reversal-of-fortune.

3 Megan Nally, “The (Unrealized) Metropolitan Master Highway Plan of 1948,” Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, September 19, 2022, https://www.leventhalmap.org/articles/visualizing-change-in-boston-activism-over-time/.

4 Crockett, Karilyn. People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw

expected, The Inner Belt, or I-695, became urgent5. However, the Inner Belt had one issue; there were few existing right of ways, so the roads had to cut through neighborhoods6. This ultimately led to its demise. The Inner Belt was never built due to community resistance, and its ultimate defeat illuminates a unique story in the history of urban renewal; one where community-first development beat intrusive infrastructure. The Inner Belt freeway illuminates the pitfalls of intrusive top-down infrastructure, and the decision to discontinue the project decision to discontinue the Inner Belt freeway is a unique choice because it valued people over cars.

The Inner Belt highway arose in a national context of highways creating battles between bottom-up and top-down development, which is crucial because the former would uniquely prevail in Boston. This dynamic is exemplified by New York’s highway battles. By the 1950s, the automobile became more than a method of transportation; it was the framework through which cities were designed. This was an era often referred to as putting cars before people.7 Two opposing figures in New York City represented a national battle that would make its way to Boston: Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs. Urban renewal and highway projects were seen as beneficial by Moses’s administration. Moses, the long-standing leader of the Triborough bridge and tunnel authority, presided over New York’s highway building craze. He laid parkways and highways as he saw fit onto the dense fabric of New York because he valued the efficiency they would provide for automobile travelers. He claimed that his “arterial highway

5 Plotkin, A. S. 1959. No immediate relief in sight for overloaded central artery. Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960), Sep 27, 1959.

6 Megan Nally, “The (Unrealized) Metropolitan Master Highway Plan of 1948,” Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, September 19, 2022

7 Jane Jacobs, 1993, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York, NY: Vintage Book

system” would create a “better, more livable city”8 . These were the same ideas that motivated Boston’s move to build highways in the region, but in both places, they overlooked the communities that were in the path of these roadways.

Jane Jacobs was a grassroots activist who successfully stopped many of Moses’s projects, which is important because her rhetoric would make its way to Boston in resistance to the Inner Belt. For example, one of the plans that Moses did carry out was the Cross Bronx Expressway, which destroyed 1500 families' homes and left the predominantly black community with decreased air quality and higher traffic9. These projects allowed for richer white suburbanites to enter the city by cutting through poorer communities. Jacobs organized opposition and successfully shut down many of Moses' later plans, often speaking for minority communities, including a large Puerto Rican community, an Italian community, and people from a wide variety of social classes10 . She became a symbol for grassroots urbanist movements where any individual could influence development11 , advocating for cities to build from the “bottom-up”, with community input and voice, instead of from the “top-down” by laying highways wherever they saw fit. In Jane Jacobs’s 1961 Book The Death and Life of Great

8 Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, "Your New York of Tomorrow" New York Public Library Digital Collections, Accessed February 20, 2024. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5080cee0-ee14-0133-4f4b-00505686a51c

9 Micheal Caratzas, “Cross-Bronx: The Urban Expressway as Cultural Landscape.” In Cultural Landscapes: Balancing Nature and Heritage in Preservation Practice, edited by Richard Longstreth, NED-New edition, 62, University of Minnesota Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttnzq.7.

10 Anthony Paletta, “Story of Cities #32: Jane Jacobs v Robert Moses, Battle of New York’s Urban Titans.” The Guardian, April 28, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/28/story-cities-32-new-york-jane-jacobsrobert-moses.

11 Anthony Paletta, “Story of Cities #32: Jane Jacobs v Robert Moses, Battle of New York’s Urban Titans.” The Guardian, April 28, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/28/story-cities-32-new-york-jane-jacobsrobert-moses.

American Cities, she describes the community-first perspective that would soon also permeate highway discourse in Boston. “Traffic arteries…are powerful and insistent instruments of city destruction. To accommodate them, city streets are broken down into loose sprawls, incoherent and vacuous for anyone afoot. Downtowns and other neighborhoods that are marvels of close grained intricacy and compact mutual support are casually disemboweled”12 . Jacobs prioritizes natural urban development over forced types. Her text echoes the climate present in many American cities at the time, including Boston; one where top-down intrusive infrastructure was being built to cut through existing communities like she refers to13 . The contrast between Jacobs’ and Moses’s viewpoints illuminates the broader battle that had arisen at the time. The same era of intrusive highways would soon arrive in Boston, and the resistance would mirror New York’s situation.

A variety of factors contributed to the forces pushing for the Inner Belt, making the project more powerful and harder to thwart. These included suburbanization, new urban planning ideologies, the technology belt, and subsequent white flight. The European ideal of “modernist” urban planning valued the most efficient, rational, and understandable way of revitalizing cities14. Boston’s dense lower-income areas which were less polished and more decrepit were put on the chopping block, like the New York Streets and the West End. The dirty “blighted” areas could only be fixed by being razed or being replaced with an idealistic neighborhood15 .

12 Jane Jacobs, 1993, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York, NY: Vintage Book

13 Jane Jacobs, 1993, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York, NY: Vintage Book

14 Crockett, Karilyn. People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw.

15 Courtney Humphries, “Reversal of Fortune?,” Boston Society for Architecture, January 2020, https://www.architects.org/stories/reversal-of-fortune.

This philosophy was influenced by Le Corbusier, who believed in a greater organization for urban spaces: roads should be straight and direct, and areas that were currently dense or impoverished needed to be polished into finely regimented neighborhoods16. Boston’s highways were agents of this goal: soon after the Federal highway program was launched in 1956, cities began expanding highways into urban areas. Highways in urban areas were said to provide easier access to declining inner cities, but they were also used to eliminate decrepit neighborhoods. In Boston, this included places like Chinatown, Roxbury, and Cambridgeport17. This, of course, was the antithesis of what anti-renewal activists like Jane Jacobs valued. The Inner Belt was important, and also debated so extensively, because it cut through dense areas; but the need for the Inner Belt only arose because of the original radial highways in the region. In the Post-war era, automobiles allowed wealthy whites in math and science to move to suburbs like Lexington, Concord, and Lincoln to work at office parks18. Route 128 was constructed as an outer ring road to connect the office parks in what was now known as the “technology belt”. The creation of highways enabled an entirely suburban lifestyle. The Inner Belt was built for the same reason; to improve connectivity for suburbanites accessing Boston and moving through it. However, at the same time, the city started

16 Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw

17 Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw.

18 Garret Dash Nelson. “Developing the Boston Suburbs.” Bending Lines, May 27, 2020. https://www.leventhalmap.org/digital-exhibitions/bending-lines/why-persuade/1.1.2/

to be seen as dirty and declining1920, which became another reason for the Inner Belt. This became a self-fulfilling prophecy; highways aided white flight, and the dwindling inner city population and tax base led to the decline of central city neighborhoods. The Inner Belt proposal helped to “renew” these neighborhoods because it would clear slums. One of the other ways in which suburbanization influenced the Inner Belt pertained to race. Now that white populations had left central Boston, those who stayed were predominantly black20. Thus, the highway’s destructive impacts would fall disproportionately on minorities. Suburbanization and white flight contributed to the push for the highway because the Inner Belt would have been a tool to destroy some of these slums instead of reinvesting in them.

19 Amy Dain, “Exclusionary by Design.” Boston Indicators, November 2023, 32 https://www.bostonindicators.org/-/media/indicators/boston-indicators-reports/reportfiles/exclusionarybydesign_report_nov_8.p df.

20 s–1975: Impact of Rte 128 & Rte 495.” Boston Fair Housing, Accessed March 4, 2025. https://www.bostonfairhousing.org/timeline/1950s-1975-Suburbs.html.

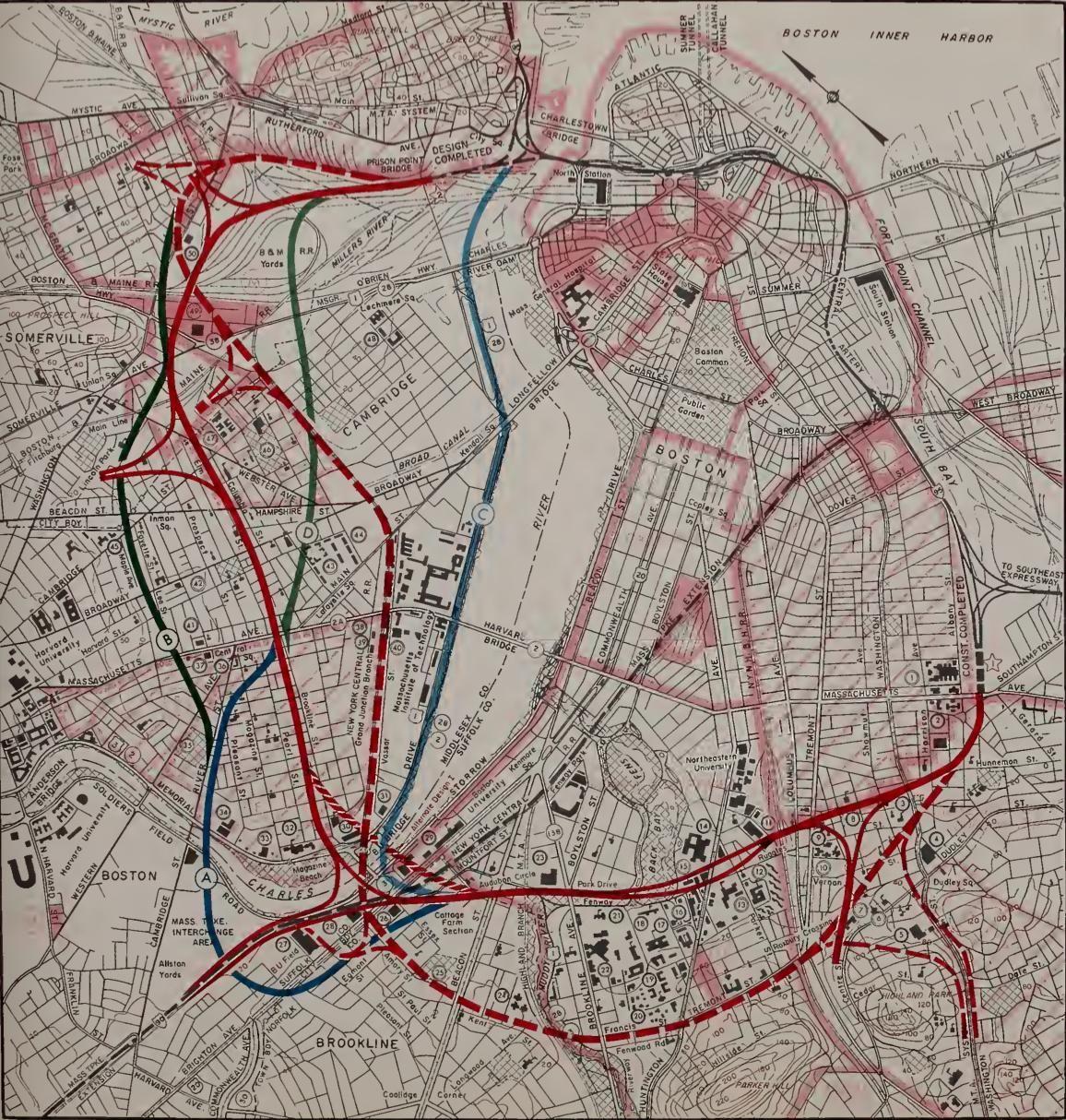

The Inner Belt and other planned highways on Metropolitan Master Plan21

When Boston unveiled its Highway Master Plan in 1948, the Inner Belt would be included as a crucial link for relieving congestion, which would contribute to the ruthless push for it to be built. The East Boston Expressway, Northeast Expressway, 21 Pete Stidman, “Casey and a Brief History of Highways in Boston,” Boston Cyclists Union, January 18, 2012, https://bostoncyclistsunion.org/casey-and-a-brief-history-ofhighways-in-boston.

Northern Expressway (I-93), Northwest Expressway, Western Expressway, Southwest Expressway, Southeast Expressway, Central Artery, and Inner Belt22 . The board that created the plan stated “"If the industrial, social and economic life of the area is to be preserved…it must be freed from the transportation strangulation it now faces."23. The Inner Belt served this unique purpose for the Metropolitan Master plan. The central artery, which cut through the center of Boston quickly developed congestion24. The belt allowed cars to deviate through Boston’s neighboring cities and towns to bypass downtown, and also to access destinations in those places. The Inner Belt was similar to Route 128, which had been built as a “Ring Road”: a circumferential route meant to connect multiple spokes of radial highways. The metropolitan master plan outlines the Belt’s purpose as both a “collector-distributor of vehicular traffic…having origin or destination in the core area of Metropolitan Boston… and an inter-connector for the transfer of vehicular traffic between the radial expressways for traffic with origin or destination either in Metropolitan Boston or on any part of the Interstate System”25. For example, the Inner Belt would help a Cambridge resident access the radial highways to leave the city, and it would also help a resident of a northern suburb like Lynn move quickly through the

22 Megan Nally, “The (Unrealized) Metropolitan Master Highway Plan of 1948,” Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, September 19, 2022, https://www.leventhalmap.org/articles/visualizing-change-in-boston-activism-over-time/.

23 It's Easy to Understand the Main Idea of the Metropolitan Master Highway Plan: Think of those Expressways as a Hub with Eight Spokes”, Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960), Feb 26, 1948, https://ezproxy.bu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistoricalnewspapers%2Feasy-understand-main-id ea-metropolitanmaster%2Fdocview%2F839611185%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9676.

24 Plotkin, A. S. 1959. No immediate relief in sight for overloaded central artery. Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960), Sep 27, 1959.

25 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

city to access a southern suburb. The expressway would mainly get suburbanites through the city and aid in regional trips, but the city also claims it would serve the neighborhoods it would pass through. Boston leadership stated, “That it not only makes for traffic sense; it would be a tremendous boost in the future for all the communities it would traverse.” However, this is hard to believe. The claim is double sided; while the Inner Belt would indeed have exits in areas like Cambridgeport and Roxbury, the route would also aid in urban renewal efforts to bulldoze communities that were already identified as blighted zones.

The Inner Belt planned to ruthlessly plow through dense neighborhoods in the name of efficiency and convenience, making it more destructive as it would have a significant impact on urban areas. While Route 128 had mainly cut through undeveloped land, the Inner Belt had to cut through 3 of Boston’s densest neighborhoods, characterized as “heavily built-up, complex, urban areas”26. It would pass through places that today feel essential to Boston: crossing the Charles River, coming dangerously close to the MFA, and almost entirely engulfing the Back Bay Fens. Noisy car and truck traffic would be moving through Cambridge, Somerville, and Brookline. The philosophy of renewal at the time stated “The modern city “lives by the straight line. . . . The circulation of traffic demands the straight line”27 . This explains the intrusive nature of the project; efficiency and convenience was prioritized, and areas that would have to be bulldozed were just collateral damage. The expressway first passed through the South End and Roxbury. Roxbury was a core part of the inner city, and

26 Megan Nally, “The (Unrealized) Metropolitan Master Highway Plan of 1948,” Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, September 19, 2022, https://www.leventhalmap.org/articles/visualizing-change-in-boston-activism-over-time/.

27 Micheal Caratzas, “Cross-Bronx: The Urban Expressway as Cultural Landscape.” In Cultural Landscapes: Balancing Nature and Heritage in Preservation Practice, edited by Richard Longstreth, NED-New edition, 62, University of Minnesota Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttnzq.7.

had become a predominantly black community. However, it was also declining at the time. A rapid population drop that also affected other areas of the inner city had hit Roxbury, and there was less investment in housing and infrastructure. The area had become a target of urban renewal efforts, and many residents were uprooted for the construction of the southwest expressway and Inner belt 28 . Again, the Inner Belt was intertwined with urban renewal, as it seemed justified when surrounding neighborhoods were already characterized as slums. Next, the highway would skirt the Museum of Fine arts and run through the Back Bay Fens29 . While Roxbury had to face the brunt of an elevated highway, the section near culturally significant landmarks would be tunneled, demonstrating a flaw in the design: people and communities were not considered in the routing of the project. The expressway would then reach a stretch in residential Brookline, and cross the Charles River at the only point possible by the dense area of Cambridgeport30. It would then reach the Cambridgeport Urban Renewal Area, where it would do the most damage to the surrounding environment.

The Cambridgeport Renewal area exemplifies how the Inner Belt was interwoven with existing urban renewal projects, adding to its destructive effect. In this area, there were no existing large thoroughfares or parks to cut through; the right-of-way had to be created. Yet again, I-695 was cleverly intertwined with an urban renewal project to make this process easier. The two initiatives

28 “Roxbury,” SEGREGATION BY DESIGN, accessed March 5, 2025, https://www.segregationbydesign.com/boston/roxbury.

29 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

30 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

would have displaced 13,000 Cambridgeport residents combined31 . The expressway would also pass Central Square, a major business district in Cambridge. However, in this case, the city acknowledges the dense development that already exists. Cultural centers would be preserved while slums are pushed aside by the highway. The plan states, “the Recommended Location serves as a desirable physical divider between the proposed Cambridgeport Renewal Area, which will be primarily developed for residential purposes, and the existing and proposed commercial and industrial areas”32 . The Inner Belt wasn’t just a transportation method, it was a tool to rebuild the city with. The areas that Boston had identified as undesirable could conveniently be eliminated by routing a highway through them, limiting urban development and manipulating the city however they see fit. In places like New York, highways that divided communities did not help to distinguish commercial districts from residential districts. Instead, highways like the CrossBronx turned its surrounding areas into ghost towns with plummeting property values and pollution because of the inhospitable infrastructure33. The Inner Belt’s character as an urban highway put it at risk of the same issues.

31 “A Very Short History of the Inner Belt Highway in Cambridge,” Cambridge MA, accessed March 5, 2025, https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/InnerBelt/innerbelt_shorthistory_version5_40est.p df.

32 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

33 Adam Paul Susaneck, “The Cross Bronx Expressway.” SEGREGATION BY DESIGN, Accessed February 8, 2024, https://www.segregationbydesign.com/the-bronx/the-crossbronx-expressway.

The Inner Belt proposal was contested and ever-changing, reflecting the core flaw of the project: it tried to find the most optimal alignment out of a set of mediocre options, instead of realizing that the highway passing through Cambridge was too intrusive to be feasible in the first place. Different alignments provided more or less intrusiveness to different communities, and some arose because of activism. However, it was clear that each alignment was a bad option for the community. There were 6 main alternative alignments through Cambridge that were considered throughout the life of the Inner Belt idea. The five original

34 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

alignments that were proposed in 1948 with the Master plan were: The Brookline-Elm alignment, Grand Junction alignment, The two River Street alignments, and the Memorial Drive alignment35. The decisions made around these alignments reflect how communities and public spaces were valued. Importantly, no alignment was optimal due to the dense nature of the area, but the Master Plan insisted that the highway must be built. Some residential spaces and recreational spaces were held higher than others. The River/Lee Alignment was scrapped because it “[passes] almost entirely through an established residential area, resulting in an undesirable division of neighborhoods”36. The planners realized the impact of the roadway, and were willing to offload it to the least valued spaces. Similarly, the Memorial Drive alignment was deemed suboptimal because it “would greatly reduce the scenic and aesthetic attractiveness of the area adjacent to the Charles River, and would decrease the value of the river for recreational purposes”37. The master plan falls into the fallacy of justifying the highway because of urban renewal, not realizing that constructing the inner belt precludes further healthy development. The plan explains the positives to the selected Brookline-Elm alignment, which conveniently excludes any mentions of the physical impacts on the surrounding community. It is clear that any location is suboptimal, but this is the least because it “will eventually be affected by urban renewal activities, and that the tax losses and the numbers of households displaced, jobs lost, and businesses affected

35 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

36 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

37 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

by the Recommended Location are substantially offset by the fact that many of these…would occur under urban renewal activities”38 . Again, the Inner Belt and urban renewal was a way for the city to do two things at once: provide better suburban connectivity, and increase the momentum of slum clearance. It was easy for the city to mask their ignorance of lower income communities, because they could claim that urban renewal would have disrupted their neighborhoods either way. With this justification, the city could argue that it was a good idea to pick a destructive alignment instead of reconsidering the project itself.

A strong and vocal resistance soon emerged to these plans, causing the division that would eventually be the end of the Inner Belt project. This mainly came from the Cambridgeport area. The success of this resistance is important, because Cambridgeport wasn’t previously politically unified and had little voice in city affairs39, which is likely one of the reasons the city selected it to route the Belt through. The Brookline-Elm route became preferred in 1957, but it was nowhere near optimal. It would destroy 1235 homes and displace thousands of people40, but when it was brought to their attention, the board only stated the alignment was optimal because it passed through “blighted and deteriorated areas in need of urban renewal and redevelopment”41. But the Cambridge community resisted this rhetoric, and acknowledged the ignorance

38 Massachusetts Dept Of Public Works, “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962, https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

39 Stephen Kaiser, Inner Belt Stepone Report citizen opposition to the ..., October 14, 2017, https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/innerbelt_kaiser.pdf

40 Robert Samuelson, “Cambridge and the Inner Belt Highway: Some Problems Are Simply Insoluble: News: The Harvard Crimson,” The Harvard Crimson, June 2, 1967, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/6/2/cambridge-and-the-inner-belt-highway/.

41 H.W. Lochner, Inc, “Interstate Route 695 Inner Belt Highway, Boston, Cambridge and Somerville: Location Restudy,” Internet Archive, May 1, 1967, https://archive.org/details/interstateroute600hwlo.

of urban renewal programs. They instead espoused a perspective that valued real people who lived in Cambridgeport, speaking of the diversity and tight-knit nature of the immigrant community. The activists spoke of “relationships with relatives and friends living nearby, often on the same block, even in the same multi unit house, with churches and clergymen in the neighborhood, with schools and teachers”42. By humanizing those who lived in the path of the Inner Belt and Urban Renewal, they could make the argument that the alignment needed to be reconsidered. Additionally, resistance from Cambridgeport raised the point that only 10% of homes in the area were actually considered dilapidated, illuminating a gaping hole in the city’s logic. Yet because the advocates felt like the Belt would inevitably get built, they began searching for alternative routes rather than trying to shut it down all together. The route they landed on was Portland-Albany, one that compromised an industrial sector rather than homes43. The fear was that Brookline-Elm would essentially ruin the neighborhood fabric, not only by removing homes, but instead because it would divide the area. There would be a strip of homes completely isolated from the rest, a divide that would alter the community and neighborhood fabric.

One of the main advocacy groups in Cambridgeport was Save Our City, which humanized Cambridge residents and shed light on the existing community to portray the belt as a destructive

42 Robert Samuelson, “Cambridge and the Inner Belt Highway: Some Problems Are Simply Insoluble: News: The Harvard Crimson,” The Harvard Crimson, June 2, 1967, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/6/2/cambridge-and-the-inner-belthighway/.

43 Robert Samuelson, “Cambridge and the Inner Belt Highway: Some Problems Are Simply Insoluble: News: The Harvard Crimson,” The Harvard Crimson, June 2, 1967, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/6/2/cambridge-and-the-innerbelt-highway/. 44 Stephen Kaiser, Inner Belt Stepone Report citizen opposition to the ..., October 14, 2017, https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/innerbelt_kaiser.pdf.

force. It was founded and led in the 1960s by Bill Ackerley, Anstis Benfield, Henrietta Jackson, and Steve Goldin44. The organization united many constituencies in Cambridgeport across religious and class lines. The two catholic churches leveraged the progress made by Save Our City to involve their congregation in activism. There were a few city officials involved in the resistance also: Fred Salvucci, Tip O’Neill, and Kevin White. Throughout the 60s, East Cambridge and Cambridgeport would strip away highway plans, but the process was slow. The first step to beat urban renewal and the inner belt was to humanize the Cambridge community.

Cambridge had come to be seen as a declining industrial city, and Cambridgeport was at the center of these critiques. In Town Hall meetings, misrepresentative photos often depicted Cambridgeport as in worse shape. One of the primary issues that activists addressed was to rewrite this narrative; one of the main slogans was “Cambridge is a City, not a highway”44. Advocate Pearl Wise, after shutting down another urban renewal project in Cambridgeport, would state that critiques of Cambridge are pieces “of social arrogance about, and class ignorance of, people who live in the Donnelly Field area and who form such an important and respected segment of our community”45. This was a struggle of people versus cars, and Save Our City was crucial in giving the impacted neighborhoods a voice.

Community outrage understandably arose quickly, as the city had landed on the Brookline-Elm routing without any consultation of residents. Planners united hoping to at least propose

44 Stephen Kaiser, Inner Belt Stepone Report citizen opposition to the ..., October 14, 2017, https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/innerbelt_kaiser.pdf.

45 Stephen Kaiser, Inner Belt Stepone Report citizen opposition to the ..., October 14, 2017, https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/innerbelt_kaiser.pdf.

a better alternative routing to the Belt, and ideally to eliminate the idea. Many residents of Cambridgeport were unaware of the belt until they were alerted by advocacy groups. Again, Cambridgeport was overlooked in the city; it was underrepresented in city council, and never before had residents been pushed to advocate for where they lived46 . After the Cambridge committee presented street-level views and maps showing where the belt would be, residents “would see and say, 'What, that damn thing is going to be close to me!' It was very effective in getting people [involved]”47 . Leveraging the previously overlooked community in Cambridgeport allowed the committee to propose other alternatives to pass through the area. The Portland-Albany and the Grand Junction alignment proposed to offload the impact of the highway onto industrial areas and MIT. The committee was rushed and makeshift in their proposal, reflecting the ongoing panic about the impact that the Inner Belt would have in Cambridgeport48 . Crucially, the Portland-Albany alignment acknowledged that real people lived in Cambridgeport and didn’t portray the area as a lost cause just because it was soon to be renewed. The original proposal would ensure that Cambridgeport was divided into a residential and an industrial/recreational district, but moving the highway away from the area altogether allows the neighborhood to naturally develop. In fact, the resistance was so powerful that the city seriously considered the alternative alignment. However, when

46 Stephen Kaiser, Inner Belt Stepone Report citizen opposition to the ..., October 14, 2017, https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/innerbelt_kaiser.pdf.

47 Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw

48 Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw.

proposing moving the highway, the truth of who really had an impact on the routing came to light.

This new route would destroy some MIT fields and prevent campus expansion, but the university was quickly able to shut it down, illuminating how corporate interests had more sway than actual residents did. A Harvard Crimson article from the time correctly identified the hypocrisy in this situation, “one wonders how the importance of the athletic fields stacks up against the moes of the 3000-5000 people who would be displaced by the BrooklineElm St. route”49. This was the truth of the situation; the Inner Belt only came under true scrutiny when it infringed on large institutions. The Polaroid company also had a factory located in the path of the alignment, which caused an uprising from that constituency50. This would lead to the Portland-Albany alignment being seen as worse for the city, as leadership wanted to keep and improve “Cambridge's attractiveness as a home for electronics, engineering, and research-oriented companies”52. Brookline-Elm would soon become the preferred alignment51. This choice essentially altered the borders between residential and industrial zones, to allow more space for laboratories and commercial activity and less space for Cambridgeport residents. The route was further west, meaning that it isolated a small pocket of residential Cambridgeport. This was an intentional choice, as the

49 Robert Samuelson, “M.I.T. versus the Inner Belt: News: The Harvard Crimson,” News | The Harvard Crimson, February 24, 1966, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1966/2/24/mit-versus-the-inner-belt-puntil/.

50 Robert Samuelson, “M.I.T. versus the Inner Belt: News: The Harvard Crimson,” News | The Harvard Crimson, February 24, 1966, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1966/2/24/mit-versus-the-inner-belt-puntil/. 52 “Inner Belt: I: News: The Harvard Crimson,” News | The Harvard Crimson, May 15, 1967, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/5/15/inner-belt-i-pthe-statedepartment/.

51 Stephen Kaiser, Inner Belt Stepone Report citizen opposition to the ..., October 14, 2017, https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/innerbelt_kaiser.pdf.

city hoped MIT would expand and make a larger industrial district out of this52. Although Save Our City and Cambridgeport residents fought mercilessly against the Belt, large institutions like MIT and Polaroid soon demonstrated the sway they had on infrastructure in the city. This suggests that the eventual defeat of the Inner Belt was not only because of Cambridgeport resistance, but also because MIT did not allow an alternative alignment.

Citizens did not back down from resisting the belt, and their eventual success would demonstrate that an average neighborhood can have an immense impact on urban development. Although the decision against the Portland-Albany alignment had put the interests of institutions first, it wasn’t the end of the story for the power of grassroots organizing in cities. In the late 1960s, the antihighway activism movement would not die down. Protests in front of the state house were common, but they only began making a difference with a leadership change and an ideology change. The 1970s would mark a shift in how American cities thought about renewal and revitalization, as they began to see the mistakes of the automobile and slum clearance craze of the 1950s and 1960s. In Boston, this would come in the form of a new governor, Francis Sargent. Sargent was a conservative, which made many lose hope that their grievances around highways would be heard. However, what is crucial is that the grassroots activists persisted. Their persistence would pay off in 1969 when one of the many protests at the state house would finally get through and elicit something more than ignorance from the state government. The governor would speak and address their concerns calmly, and this one protest would be the first step to rapid progress.53 Just a year later, Sargent

52 Robert Samuelson, “Cambridge and the Inner Belt Highway: Some Problems Are Simply Insoluble: News: The Harvard Crimson,” The Harvard Crimson, June 2, 1967, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/6/2/cambridge-and-the-inner-belt-highway/.

53 “Inner Belt: I: News: The Harvard Crimson,” News | The Harvard Crimson, May 15, 1967, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/5/15/inner-belt-i-pthe-state-department/.

would make an announcement showing that anti-highway activism actually had sway on city decisions. He would state, “"Four years ago, I was Commissioner of the Department of Public Works our road building agency. Then, nearly everyone was sure highways were the only answer to transportation problems for years to come. We were wrong”54 . He would go on to announce a study to reallocate transportation funds to places where they weren’t as costly to the city; both in terms of dollars, but also in terms of displacement and pollution. This plan would halt all plans to build the Inner Belt. This was unprecedented because not only has grassroots activism shut down the Inner Belt, it ushered in an entirely new people-first era of urban design in Boston.

Governor Sargent would allocate Inner Belt funds for Mass Transit, an indicator of a shift in priorities. One of these transit projects that replaced highway plans was the Southwest Corridor project, which converted a planned highway corridor into a green walking space and a new Orange Line. The Red Line to Alewife served more of Cambridge, a city that would have faced the brunt of the Inner Belt55. This was a crucial step forward because it shifted the narrative around finding a highway alignment that minimized costs to communities, and instead questioned why the highway had to be built in the first place. Sargent wanted a transportation plan based not on “where an expressway should be built, but whether an expressway should be built."56. In the case,

54 Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw

55 Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw

56 Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw.

this fallacy arose when the Brookline/Elm alignment was being pitted against the Portland/Albany alignment. It was clear that both alignments were very detrimental to the surrounding communities, as there was no clear right of way through Cambridge. Instead of acknowledging that Cambridge might not be served by a highway, the debate was about how to best cut the losses that would come with building the belt. Sargent’s statement is a massive pivot from this mentality. Suddenly, bottom-up community driven urban development had an advocate in the State House. In his next address in 1972, Governor Sargent would lean even more into this shared idea of urban development, using the pronoun “we” in his speech to describe how his team would navigate these issues. He would state, “Massachusetts, indeed America confronts the same old problem now complicated by a growing paralysis on our superhighways. The old system has imprisoned us. We've become the slaves and not the master of the method we chose to meet our needs.”

57 . Sargent included himself with the community of Boston in his speech, in order to identify with the needs and views they were expressing. His shift in ideals was powerful, because it ensured that Boston would prioritize people over cars.

Boston’s Inner Belt was a unique case, in the context of the country, of a highway project that got stopped before it could do irreparable damage. One can compare the prosperity of the neighborhoods which the Inner Belt would have passed through with neighborhoods in the city where highways were built, and understand the power of stopping the belt. Cambridgeport and Central Square rapidly changed from blue collar to white collar areas in the 1980s reflecting how MIT and Cambridgeport meshed in a way that created more job opportunities for those living in the

57 Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018, 129. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw

area58. Today, Central Square is a thriving commercial district, and the Mass Ave corridor reaches from there to MIT without any interruptions. On the other hand, in places like Charlestown and Somerville where I-93 was built, the story is not similar. A 2017 Tufts study illuminates the extent of noise pollution in the areas. It sought to fix the loud sounds created by the highway, to try to fix some of the surrounding areas that had seen drastically decreased property values and less inviting business districts59. The efforts to repair the damage done by I-93 suggests that it had a negative impact on the neighborhoods it passed through areas. With this information, it is easy to imagine a world in which the Inner Belt would have had similar or worse negative consequences for Cambridge, Brookline and Somerville. Boston’s Inner Belt proposal is a warning, demonstrating the danger of highways and how they can tear apart urban environments. However, the story of the Belt is ultimately hopeful. It is a testament that even an overlooked community lacking influence can unify against a common threat, if people are driven enough to stand up for where they live. It is a strong argument that any citizen can, and should, have true power over how their city is developed.

58 Paul Hirshson, Globe Staff, "A Time of Change in Cambridgeport." Boston Globe (1960-), Jun 17, 1983, https://ezproxy.bu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistoricalnewspapers%2Ftime-change-cambridgep ort%2Fdocview%2F1639243594%2Fse2%3Faccountid%3D9676.

59 Doug Brugge, “Noise Barriers in Somerville: A Health Lens Analysis,” Tufts University, 2019, https://sites.tufts.edu/cafeh/files/2019/03/HLA_Report_Final.pdf.

Works

Cited

“A Very Short History of the Inner Belt Highway in Cambridge.” Cambridge MA. Accessed March 5, 2025.

https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/InnerBelt/innerbel t_shorthistory_version5_40est.pdf.

“1950s–1975: Impact of Rte 128 & Rte 495.” Boston Fair Housing. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://www.bostonfairhousing.org/timeline/1950s-1975Suburbs.html.

Bedrosian, Shosh. “Bronx Organizations Pushing for Environmental Justice with High Asthma Rates in Community.” CBS News, April 20, 2023. https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/bronx-asthmarates-environmental-justice/.

Brugge, Doug. “Noise Barriers in Somerville: A Health Lens Analysis.” Tufts University, 2019. https://sites.tufts.edu/cafeh/files/2019/03/HLA_Report_Fin al.pdf.

Caro, Robert A. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf, 1974.

Caratzas, Micheal. “Cross-Bronx: The Urban Expressway as Cultural Landscape.” In Cultural Landscapes: Balancing Nature and Heritage in Preservation Practice, edited by Richard Longstreth, NED-New edition, 55–72. University of Minnesota Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttnzq.7.

Crockett, Karilyn. People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. University of Massachusetts Press, 2018.

https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv47w9bw.

Dain, Amy. “Exclusionary by Design.” Boston Indicators, November 2023.

https://www.bostonindicators.org//media/indicators/boston-indicators-reports/report-files /exclusionarybydesign_report_nov_8.pdf.

Gehl, Jan. Cities for People. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2010. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10437880.

Humphries, Courtney. “Reversal of Fortune?” Boston Society for Architecture, January 2020.

https://www.architects.org/stories/reversal-of-fortune.

Inner Belt: I: News: The Harvard Crimson. May 15, 1967. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/5/15/inner-belt-ipthe-state-department/.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1993.

Kaiser, Stephen. Inner Belt Stepone Report Citizen Opposition to the…, October 14, 2017.

https://www.cambridgema.gov//media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/innerbelt_kaiser.p df.

Lochner, Inc, H.W. “Interstate Route 695 Inner Belt Highway, Boston, Cambridge and Somerville: Location Restudy.” Internet Archive, May 1, 1967.

https://archive.org/details/interstateroute600hwlo.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “New York City with Proposed Brooklyn Battery Bridge Project in Red.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 20, 2024.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/76781bf0-ee110133-3557-00505686a51c.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Robert Moses at the Placing of Final Steel, Fire Island Inlet Bridge.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 20, 2024.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/711a85c0-f95f013a-138d-0242ac110003.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Your New York of Tomorrow.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 20, 2024.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5080cee0-ee140133-4f4b-00505686a51c.

Massachusetts Dept. of Public Works. “Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area.” Internet Archive, January 1, 1962.

https://archive.org/details/innerbeltexpress00mass.

Moreno, Carlos. 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet. Wiley-Blackwell, 2024.

Nally, Megan. “The (Unrealized) Metropolitan Master Highway Plan of 1948.” Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, September 19, 2022.

https://www.leventhalmap.org/articles/visualizing-changein-boston-activism-over-time/.

Nelson, Garrett Dash. “Developing the Boston Suburbs.” Bending Lines, May 27, 2020.

https://www.leventhalmap.org/digital-exhibitions/bendinglines/why-persuade/1.1.2/.

Paletta, Anthony. “Story of Cities #32: Jane Jacobs v Robert Moses, Battle of New York’s Urban Titans.” The Guardian, April 28, 2016.

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/28/storycities-32-new-york-jane-jacobs-ro bert-moses.

Paul Hirshson, Globe Staff. “A Time of Change in Cambridgeport.” Boston Globe (1960-), June 17, 1983. https://ezproxy.bu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww. proquest.com%2Fhistorical-n ewspapers%2Ftime-changecambridgeport%2Fdocview%2F1639243594%2Fse2%3Fac countid%3D9676.

Plotkin, A. S. “No Immediate Relief in Sight for Overloaded Central Artery.” Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960), September 27, 1959.

https://ezproxy.bu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww. proquest.com%2Fhistorical-n ewspapers%2Fnoimmediate-relief-sight-overloadedcentral%2Fdocview%2F250817112 %2Fse2%3Faccountid%3D9676.

Roxbury. Segregation by Design. Accessed March 5, 2025. https://www.segregationbydesign.com/boston/roxbury.

Samuelson, Robert. “Cambridge and the Inner Belt Highway: Some Problems Are Simply Insoluble.” The Harvard Crimson, June 2, 1967.

https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/6/2/cambridgeand-the-inner-belt-highway/.

Samuelson, Robert. “M.I.T. Versus the Inner Belt.” The Harvard Crimson, February 24, 1966.

https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1966/2/24/mit-versusthe-inner-belt-puntil/.

Susaneck, Adam Paul. “The Cross Bronx Expressway.” Segregation by Design. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.segregationbydesign.com/the-bronx/the-crossbronx-expressway.

“The Inner Belt.” The Harvard Crimson, February 26, 1966. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1966/2/26/the-innerbelt-pcambridge-politicians-and/

Stidman, Pete. “Casey and a Brief History of Highways in Boston.” Boston Cyclists Union, January 18, 2012. https://bostoncyclistsunion.org/casey-and-a-brief-historyof-highways-in-boston.