Alejandro Latorre

Senior Thesis | 2025

Criticisms of the Field of Impostor Phenomenon Research: Evaluating the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale

Alejandro Latorre

Boston University Academy

BUAST80: Senior Thesis

Ms. Olive Brown

May 10, 2025

Abstract

In this literature review of texts on Impostor phenomenon which I will be referring to as IP for the duration of this review, I intend to bring to light three issues with the current literature on IP brought up by Daniel Gullifor (2024). The first is the wealth of inaccuracies and inconsistencies caused by Clance and Imes’ (1978) description of IP as a trait rather than an experience and the unwillingness of the Psychology community to fully adjust to the new corrected classification as a trait. Even though Clance herself called IP and experience in her original study, the way she described it seemed more like a trait. The second criticism is the ambiguous reasoning researchers use when explaining the results of their IP studies, the assumptions regarding the effects of IP on work performance, mental state, and many other correlations. The last is that a sizable portion of IP research is reliant on crosssectional survey designs which comes with some disadvantages that have hindered IP research (p. 235). Specifically, I will discuss the shortcomings of the Clance Impostor Phenomenon scale, which I will refer to as CIPS, which has been the primary method for quantifying IP tendencies since it was created in 1978. These three issues are the main challenges to furthering IP research, and hinder it to this day.

Conceptualizations of Impostor Syndrome (Phenomenon)

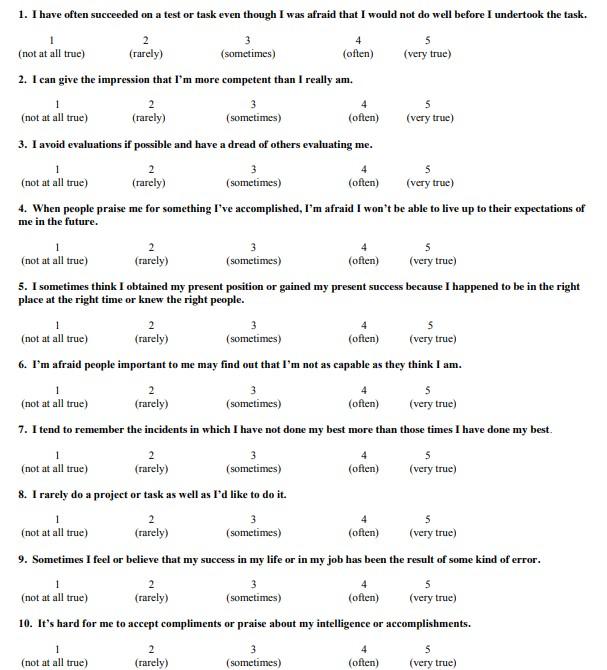

Have you ever noticed one of your loved ones deprecating themselves and saying that they’re not good at a task or career that you believe them to be very skilled at? They’re likely experiencing what is commonly referred to as Impostor Syndrome, otherwise known as Impostor Phenomenon (IP). Impostor phenomenon is a term coined by Dr. Pauline Rose Clance and Dr. Suzanne Ament Imes to describe an “internal experience of intellectual phoniness” (1978). Clance observed that women who were high-achieving in their workplaces and had received accolades for their successes at times believed that they were undeserving of the praise they received. IP, in addition to creating a feeling of unworthiness or not belonging, caused those women suffering from it to believe that they were actively defrauding their peers. When evidence was offered to counteract their feelings of phoniness it did “not appear to affect the impostor belief” (Clance and Imes, p. 241). Even though the study by Clance and Imes only focused on women in the workplace, the phenomenon was found in later research to affect all groups of people but was especially prevalent in marginalized groups. The measurement Clance used to quantify the severity of cases of IP was a self-report measure specially created for the study called the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS) (see Appendix A).

Since the conceptualization of IP by Clance and Imes there have been other conceptualizations of IP but by far the most prevalent in both popular media and scientific research has been that of Clance and Imes. According to Daniel P. Gullifor, approximately 84% of work (Articles, journals, media portrayals) use the Clance and Imes definition of IP, followed by 17% using the Harvey and Katz conceptualization (2024).

Dr. Joan C. Harvey and Cynthia Katz defined Impostor Phenomenon as “a psychological syndrome or pattern [...] based on intense, secret feelings of fraudulence in the face of success and

achievement”, therefore defining it as a mental affect similar to the original conceptualization created by Clance and Imes rather than the modern claim that IP is an experience more akin to an episode or event (p. 2, 1985). Harvey created a measure for gauging IP called the Harvey IP scale, which asks questions similar to the CIPS but measures the levels of IP in individuals based on three factors: feelings of being an impostor, unworthiness, and inadequacy (see Appendix B).

The next most significant approach to IP was that taken by the researcher Ket De Vries in 2005. According to Gullifor in 2024 approximately 7.4% of work which either focused on or contained mention of IP used the definition of IP created by De Vries. Instead of defining IP as either an experience or a mental disorder, it describes “neurotic impostors” as people who are predisposed to feelings of fraudulency. They believe that they are bluffing their way through life and that any praise they earn is simply proof of how good at lying they are. According to De Vries, the experience of IP is not created by the social context surrounding an individual, but rather a preexisting condition is amplified by the social context.

The final conceptualization of IP of any significance in modern IP research is that of Mark R. Leary et al. Leary’s article titled “The Impostor Phenomenon: Self-Perceptions, Reflected Appraisals, and Interpersonal Strategies” focuses on the relationship between self-appraisals and reflected appraisals. He claims that there are two types of impostors: “true impostors” and “strategic impostors” (p. 725, 2000). Leary and his colleagues conducted 3 studies. The first was one where Participants were asked to complete two measures of IP: how they perceived themselves and how others perceived them. The results of this study were that “High Impostors” had both low self-appraisals and low reflected appraisals. This was surprising because common conceptualizations of IP often portray Impostors as those who are highly regarded by others but have low self-esteem but “no

research [in the past] has directly tested the assumption that persons characterized as impostors actually evaluate themselves less positively than they believe others do” (Leary, 728). In other words, people who were found to be “impostors” did not actually believe that others praised them highly. In his second study, after the surprising results of the first study, Leary aimed to figure out why people may appear to be impostors but not experience the feeling of being an impostor. Leary discovered that it is socially advantageous to claim that one is an impostor because that way they won’t be ridiculed when they fail, but they will garner praise if they succeed at something. In the third study, Leary expands his conceptualization of IP to include two types of impostors: “True Impostors” and “Strategic Impostors”.

Notably, IP is not included in the DSM-5 because it is not classified as a mental disorder. The decision to omit IP was a correct one, but it contributed to the decentralized ideas about IP because each researcher is free to include their own conceptualization of IP.

The Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale as a method for Quantifying Impostor Phenomenon

As stated earlier to collect empirical data on the personal experiences of women and to interpret it as either IP or not. Dr. Clance developed the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS). The CIPS is a self-report questionnaire developed by Clance in 1985 that aims to quantify the prevalence of IP tendencies in an individual (Erekson, 2022). It contains 20 questions that inquire about the participant’s perception of themself in relation to other people. An example of one of the questions in the CIPS is “I often compare my ability to those around me and think they may be more intelligent than I am.” (Clance 1986, pp. 20-22). Each question on the CIPS is scored on a five-point scale ranging from “Not True at all” to “Very True”. It has been used by psychologists

studying IP to quantify the number of IP traits in individuals since its creation in 1985.

Impostor Phenomenon’s Correlation to Poorer Mental Health

Studies utilizing the CIPS have also used other self-report measures such as the Mental Health Inventory (MHI), created by Viet and Ware in 1983 which “assesses psychological distress” and the Test of Self Conscious Affect (TOSCA), created by Tangey and Dearing in 2002 which measure the participant’s proneness to shame to ascertain whether or not there was any connection between IP and other negative mental affects (Stone-Sabali et al., p. 3637). In Steven Stone-Sabali’s paper titled “Impostorism and Psychological Distress among College Students of Color: A moderation analysis of Shame proneness, Race, Gender, and Race Gender Interactions” (2024) he found that no matter the participant’s disposition to shame, there was always a positive correlation between IP tendencies and levels of anxiety (pp. 36323648). A positive correlation between IP and poorer mental health was assumed after the original Clance study and the empirical data supports this assumption.

Criticisms

of Impostor Phenomenon

Research

as described by Daniel P. Gullifor (2023)

Dr. Gullifor and his colleagues highlighted three valid criticisms of IP research. His first criticism is that psychologists assume that IP has a trait-nature as Clance did in her original study with Imes. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5) defines the five domains of traits as Negative affectivity, Detachment, Antagonism, Disinhibition, and psychoticism. In the DSM-5 traits are classified as clinical diagnoses. Clance and Imes believed IP to be a clinical diagnosis rather than an experience which warped future IP

research. The point that Gullifor is making is that psychologists place an over-reliance on the research of Clance and Imes without bothering to explore the concept further and highlight other causes or effects of IP. Clance and Imes theorized that IP was a personality trait and should be treated by intervention because they believed it to be a phenomenon. Clance later backtracked on that statement in an interview saying “if I could do it all over again, I would call it the imposter experience, because it's not a syndrome or a complex of a mental illness, it's something almost everyone experiences” (Cuddy, 2015, p. 95). Psychologists such as Dr. Ronit Kark have suggested that IP may have contextual causes rather than causes rooted in mental illness. In essence, the issue is not with the mental state of the women suffering from IP but rather the social context that created the experience of Impostorism. This understanding of IP which was accepted by Clance has not received recognition, in favor of the definition of IP created by Clance and Imes in 1978. This lack of further development creates confusion in the field of IP research. Gullifor stated that “the lack of conceptual development has resulted in a rudimentary understanding of the construct itself, as evidenced by the inconsistent terminology used to describe it (e.g., phenomenon, syndrome, and feelings)” (p. 235).

The second criticism Gullifor levies is that throughout IP research the phenomenon is mired in “a muddle of confusing and atheoretical relationships with other constructs dispersed across disciplines” (p. 235). Because IP is so widely applicable in many different fields, published works that mention IP do not always do so with scientific rigor. This leads to unspecified connections with other constructs such as burnout, poorer workplace performance, etc. These connections are “at best, underspecified, and at worst, misspecified or inaccurate”

(Gullifor, p.235). An example of this can be seen in Dena M. Bravata et al.’s article titled “Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: a Systematic Review”.

“Impostor syndrome is increasingly presented in the media and lay literature as a key behavioral health condition impairing professional performance and contributing to burnout. However, there is no published review of the evidence to guide the diagnosis or treatment of patients presenting with impostor syndrome”(Bravata, 2020).

IP is portrayed in the media to affect work performance and cause burnout but this claim of correlation of constructs has no basis in actual research. Even if it is true at best it is simply an assumption. Furthermore, the treatments available for IP are not proven by published reviews to help negate the experience of IP. Because of the conceptual misunderstanding that IP is a trait Gullifor stated “too many have been overzealous in their rush to examine the relationship between IP and their respective field's most prominent outcomes, glossing over the conceptual foundations upon which IP is built” (p.235). Drawing connections with IP and other phenomena across disciplines is a result of the lack of scientific rigor Gullifor was referring to. These sorts of assumptions are common across IP representation in research and media alike.

Lastly, the third criticism he offers against contemporary IP research is too reliant on cross-sectional survey designs. This is in part because IP has been popularly conceptualized as a trait-based phenomenon, but also because cross-sectional studies are by far the easiest and cheapest to conduct. When comparing cross-sectional survey designs to other designs, most notably the longitudinal design, we can see that cross-sectional surveys eliminate the issues of selection attrition, and cost, while ceding the accuracy of the results over time. A longitudinal survey design is when you repeatedly collect data from the same group of participants over an

extended period of time. This type of research yields better long term results, and more accurate ones, but as stated earlier it is far more expensive than a one time survey. In addition to that people intentionally drop out of the studies which means that the remaining people are there deliberately and not by random chance, which creates bias in the sample. the methodological rigor and variety of IP studies have been greatly limited. This insistence on a trait-based model for studying IP has resulted in “a significant body of research relying on student-based samples utilizing crosssectional survey designs” (p.235). A cross-sectional survey design refers to a data collection method in which data about a population is collected at a specific point in time, in other words, a “snapshot”. These “snapshots” do nothing to observe the effect that IP has on individuals over time, or whether or not these feelings are isolated instances or persist in the long term. IP research has been married to the CIPS, which was developed in 1985, but does not capture the full picture of IP.

To certify whether Gullifor’s three criticisms are founded or not, the following section of the article will cross-reference three articles that mention or are surrounding IP. According to Gullifor, there are inconsistencies across the field of IP research so to illustrate those inconsistencies, these articles will represent a microcosm of what the field as a whole looks like. The articles selected for the comparison are those written by Steven StoneSabali et al., whose work was mentioned earlier, Wendy L. Sims and Jane W. Cassidy, and Susmita Paladugu.

Applying Gullifor’s Criticism to “Impostorism and Psychological Distress among College Students of Color: A moderation analysis of Shame proneness, Race, Gender, and Race Gender Interactions” (Stone-Sabali et. al)

In their 2023 article Stone-Sabali and his colleague’s article, he discuss how “shame-proneness” in university students of color, where shame is defined as a “self-conscious emotion in which individuals believe they are inherently flawed and feel disgusted towards their core self” (p. 3648), has a moderating effect on IP severity. His article uses the CIPS as one of its measures when determining whether or not an individual has IP.

Gullifor’s first criticism is present in this article. In only the first paragraph of the article, Stone-Sabali uses both “Impostor Phenomenon” and the term “Impostortism” to describe IP. This is the “inconsistent terminology” that Gullifor referred to in his article. In the article, Stone-Sabali denotes that IP is an experience rather than a phenomenon but the muddling of term is still present. If it was classified as purely an experience he should’ve only used the term “Impostorism” and not “Impostor Phenomenon”. In the article, he measures how the likelihood of experiencing psychological distress in the form of mental disorders such as anxiety and depression is affected by experiencing IP. This experience is congruent with the modern definition of IP supported by Kark(2021). Even though Stone-Sabali’s definition of IP is correct the effects of the common misconception are still present in his research in the inconsistent terminology.

The second criticism Gullifor raises is that a relationship between negative mental health effects and IP is generally assumed without any scientific explanation. Stone-Sabali’s article manages to sidestep this issue, as its primary focus is to measure that very relationship, but the relationship between poorer mental health and IP is usually assumed as seen in the next article.

Gullifor’s third criticism that psychologists conducting IP research overuse “cross-sectional survey designs” is present in Stone-Sabali’s article because, to quantify IP in the students of color that he studies, he uses the CIPS, which is a cross-sectional survey, that also has the added detriment that it was created with the supposed trait-based nature of IP in mind. Even though StoneSabali describes IP as an experience, the method he employs for finding out whether or not one of his participants has experienced IP is a method that assumes that IP is a trait or trait-like. In other words, Stone-Sabali uses a self-report measure that aims to find out whether someone is “suffering from” IP, as one would suffer from a mental illness.

Applying

Gullifor’s Criticism to “Impostor Feelings of Music Education Graduate Students” (Sims and Cassidy)

This 2020 study by Wendy L. Sims and her colleague Jane W. Cassidy aimed to “investigate the IP feelings of music education graduate students” (p. 249).

Gullifor’s first criticism is founded in this article in the inconsistent terms used by the two psychologists. They use the terms “Impostor Feelings” and “Impostor Phenomenon” interchangeably providing yet another example of the disorganized nature of IP research. These terms cause confusion because “Impostor Feelings” implies an experience conceptualization of IP, whereas “Impostor Phenomenon” is more ambiguous. The variance in terminology is not necessary because Sims and Cassidy use the Clance and Imes definition of IP as an experience rather than a syndrome.

Gullifor’s second criticism is also present in Sims and Cassidy’s article when the two researchers claim that IP among graduate music students can be “Frequent and intense impostor feelings can affect an individual’s well-being by producing detrimental symptoms such as anxiety, stress, depression,

procrastination, and job burnout” (p. 250) without defending that claim. To make a claim such as that they would need to show that the individuals they studied were affected by IP, which is challenging because of the confusion around what being affected by IP entails, and also find a method to prove that their work performance was affected by IP and not some other factor in their life.

Gullifor’s third criticism is validated in this article because, in the first study they conducted, Wendy and Sims used the CIPS to determine whether or not each graduate was affected by IP. As stated earlier, the CIPS is a “cross-sectional survey design” as Gullifor put it, meaning that it is only able to take data about how the student is feeling at a specific point in time (2024, p. 235). In the second study the two researchers conducted, they used another survey they titled the “Graduate Music Student Scale” (GMSS) which contained questions that were more specific to graduate music students. Though it was a better survey for gathering information about IP in this specific population it was still only a snapshot of their mental states. Both of these studies would’ve been improved with a longitudinal survey design because they could’ve gained information on the graduate student’s mental health over the course of a school year, or around the time of final exams.

Applying Gullifor’s Criticism to “Impostor syndrome in hospitalists- a cross-sectional study” (Paladugu et al.)

In 2021 Paladugu and his colleagues Tom Wasser and Anthony Donato studied levels of IP in hospitalists at an undisclosed United States hospital and the effects that mentoring programs had on IP in hospitalists.

Addressing Gullifor’s first criticism one can see that Paladugu and his colleagues refer to IP as “Impostor Syndrome” which is another example of inconsistent terminology. In the three

articles examined thus far, the terms “Impostor Phenomenon”, “Impostorism”, “Impostor Feelings” and “Impostor Syndrome” have all been used to describe IP, which validates the claim that there is little consensus on what IP is referring to. Whether IP is a trait or an experience remains yet to be determined. This is not an issue of outdated terminology because all of these papers were written in the past five years, longer after the term Impostor Phenomenon was coined by Clance and Imes in 1978.

Gullifor’s second criticism is that claims are made about IP that are not backed rigorously. That is not to say that the claims are incorrect but making assumptions is still damaging for IP research. This criticism is present in Paladugu’s article as he assumes a negative correlation between work success and experiencing feelings of IP. Paladugu says that because those affected by IP have feelings of fraudulency and self-doubt they “often lack motivation to lead or plan their careers” (p. 212).

Gullifor’s third criticism is prevalent in Paladugu’s article as it is in Stone-Sabali’s and Sims’. To determine whether or not one of his participants was affected by IP he used the CIPS which is a cross-sectional survey design. There is no way to ascertain if that was simply how the hospitalist felt on that day or whether they’ll experience those feelings in the future. Perhaps having been asked if they perceive these feelings may have affected the severity of these feelings, making them either more or less severe, now that it had been brought to their attention, but there is no way to find that out because the CIPS only asks for how they’re feeling at that point in time.

Conclusion

Described by Clance and Imes as “an internal experience of intellectual phoniness” in 1978, the conceptualization of IP has changed since then but there’s a pressing need to centralize ideas in the field of IP research. IP research uses different terminology which creates confusion about the nature of IP. Terms such as “Impostor Phenomenon” and “Impostor Syndrome” seem to suggest a trait like nature while other terms such as “Impostorism” and “Impostor Feelings” suggest an experience of IP rather than a disorder. All four of these terms were in use by psychologists researching IP in the past five years alone. This confusion is due to the myriad of conceptualizations of IP. The conceptualizations of Harvey and Katz, Ket de Vries, and Leary each have significant representation in IP research along with the original conceptualization of Clance and Imes or sometimes no conceptualization at all, simply assuming that the reader knows what IP is already (Gullifor, p. 238). Essentially, there’s no consensus on what IP is, even though there’s strong evidence to suggest that IP is an experience rather than a trait. That sentiment is even shared by Clance herself who lamented her original traitconceptualization of IP. IP research is also plagued by assumptions about the effects of IP across disciplines. A common assumption made about IP is that it causes burnout in the workplace, but this statement is often made without any proof to back it up. These assumptions about IP have also made their way into media, as most depictions of IP in television or film assume that it causes deleterious effects on the individual's work performance, displaying the prominence of these misconceptions. Lastly, IP research is limited by cross-sectional survey designs which only capture a snapshot of the mental state of those who take them. The main offender is the CIPS, on which a vast portion (44.5%) of the IP research community had been relying to gauge levels of IP in individuals (Gullifor, p. 239). Other surveys had been developed

that tried to improve the CIPS, such as the Harvey IP Scale and the Leary IP Scale, but none of them acknowledged the shortcomings of only using one method of data collection. None of these surveys give information about the effects of IP over time, only in the instant they took the survey. As a result of Impostor Phenomenon’s omission from the DSM-5, there is no resource for which psychologists can look to create their own research on IP, leaving them to use differing definitions of IP, and stagnant methods such as cross-sectional survey designs, further contributing to the muddle that is IP research.

Appendix A Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale

Appendix B Harvey IP Scale

References

Bravata, D. M., Watts, S. A., Keefer, A. L., Madhusudhan, D. K., Taylor, K. T., Clark, D. M., Nelson, R. S., Cokley, K. O., & Hagg, H. K. (2020).

Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: a Systematic Review. Journal of general internal medicine, 35(4), 1252–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05364-1

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women:

Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15, 241 – 247. https://doiorg.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1037/h0086006

Clance, P. R., (1986). The Impostor Phenomenon: When Success Makes You Feel Like A Fake. Bantam. Cuddy, A. (2015). Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges. Little, Brown & Company

Erekson, D. M., Larsen, R. A., Clayton, C. K., Hamm, I., Hoskin, J. M., Morrison, S., Vogeler, H. A., Merrill, B. M., Griner, D., & Beecher, M. E. (2024). Is the Measure Good Enough? Measurement Invariance and Validity of the Clance Imposter Phenomenon Scale in a University Population. Psychological Reports, 127(4), 1984–2004. https://doiorg.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1177/00332941221139991

Gullifor, D. P., Gardner, W. L., Karam, E. P., Noghani, F., & Cogliser, C. C. (2024). The impostor phenomenon at work: A systematic evidence‐based review, conceptual development, and agenda for future research. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 45(2), 234–251. https://doiorg.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1002/job.2733

Harvey, J. C., & Katz, C. (1985). If I'm So Successful, Why Do I Feel Like aFake?: The Impostor Phenomenon. St. Martin's Press

Kark, R., Meister, A., & Peters, K. (2022). Now You See Me, Now You Don’t: A Conceptual Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Leader Impostorism. Journal of Management, 48(7), 1948-1979.

https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063211020358

Paladugu, S., Wasser, T., & Donato, A. (2021). Impostor syndrome in hospitalists- a cross-sectional study. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, 11(2), 212–215.

https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2021.1877891

Sims, W. L., & Cassidy, J. W. (2020). Impostor Feelings of Music Education Graduate Students.

Journal of Research in Music Education, 68(3), 249–263. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48740457

Stone-Sabali, S., Uanhoro, J. O., McClain, S., Bernard, D., Makari, S., & Chapman-Hilliard, C. (2024). Impostorism and Psychological Distress among College Students of Color: A moderation analysis of Shame-proneness, Race, Gender, and Race-Gender Interactions. Current Psychology, 43(4), 3632–3648.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1007/s12144-023-045790