10 minute read

Joanne Witmer von blon ’45

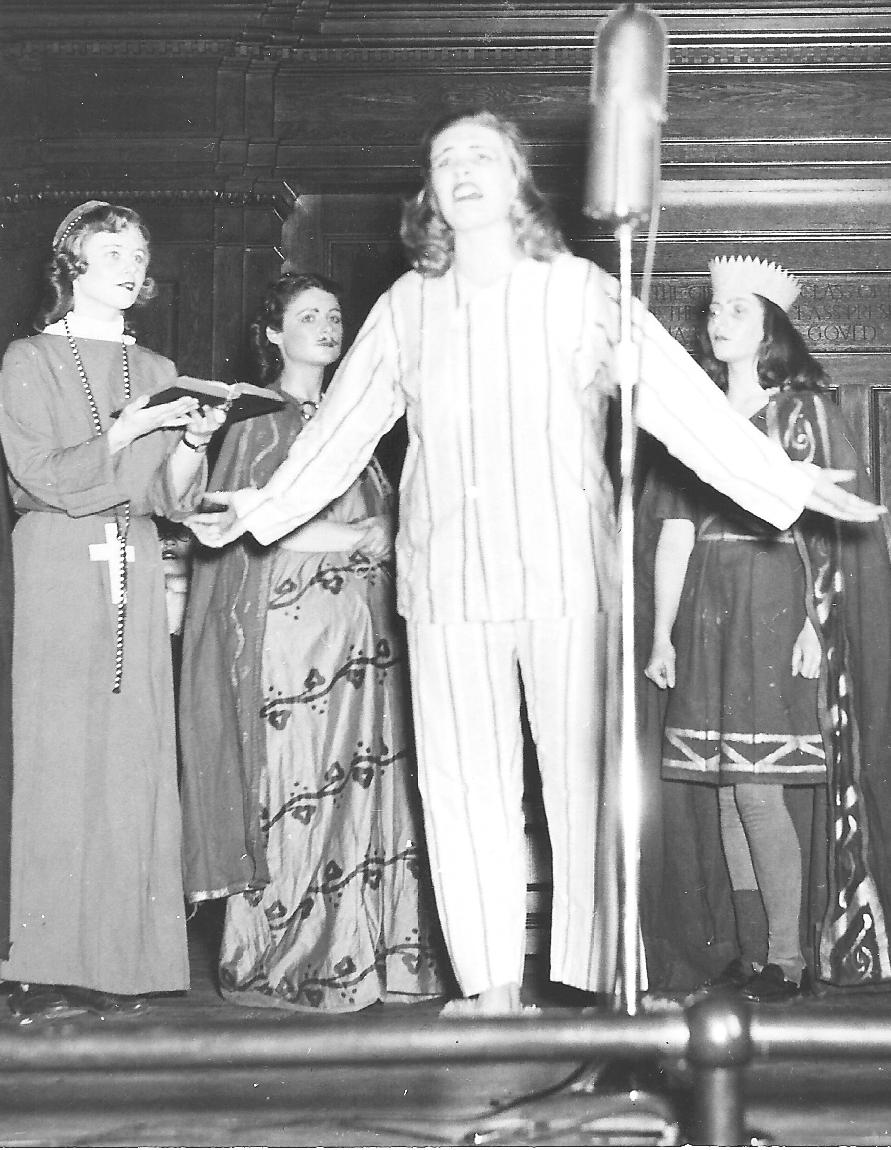

Joanne (left) with Jane Deacon ’44, Park House housemate and a member of the very prestigious “Grass Cops” —students who patrolled campus to keep people on paths and off the grass

rethinking Values, upending Intolerance

Advertisement

Joanne Witmer von blon ’45

interviewed by Judy neiswander ’69 and molly duff woehrlin ’53 on July 11, 2008

With a volunteer résumé of community service, activism, and advocacy as thick and impressive as any professional’s, Joanne Witmer Von Blon’s passions are diverse and still going strong.

Joanne credits attitudes and friends at Smith not only with inspiring her lifelong love of literature (she majored in English and philosophy) but also her fierce advocacy of social justice, “upending” some of her family’s intolerance that was so typical of the times. She has remained true to both passions.

She was born in Minneapolis, but knows little about her father’s or mother’s families. “I was so closed that I never asked why my family came to Minnesota.” She does know that her mother was from Iowa (her grandfather owned a shoe store there) and her father from Pennsylvania, the only boy with 13 older sisters. After her parents divorced, she grew up in “a sort of stepfamily … probably not the best childhood from my point of view. I didn’t care much for my stepfather, although when I was an adult I learned to love him.”

What Joanne learned from her parents was that “It wasn’t good that Jews were moving into the neighborhood,” that “Catholics had a hard look around the mouth,” that we should “Feel sorry for poor people,” that “Negroes were just not in the picture,” and that “Republicans were much better than Democrats.”

Those values were overturned at Smith. “I’ll never forget on one of my first days at Smith walking down Elm Street with a housemate, Judy Stavitsky. She said something about being Jewish. …Here was this nice girl I wanted to be friends with, and she was Jewish. The whole world opened up.”

“By the time I graduated, I was practically a Communist!” (Now she calls herself a “moderate Democrat.”) “But we learned in college that some things were wrong—that you should question them. Being at Smith with other young women who were rethinking their values changed us all.”

Joanne’s mother, who briefly attended the University of Minnesota before going to work, planned “that I would grow up to be and do something more than she had—although she had accomplishments of her own, being a champion golfer. But she sent me to Northrop Collegiate to get educated.” Joanne believes she may be the first person in her family to finish college.

Joanne chose Smith because it had a wonderful reputation and a good English department, and “I had wanted to be an English major from the time I was a little kid.” She was impressed that Harold Faulkner, author of a history text used at Northrop, was a professor at Smith. And Minneapolis had a lot of respected Smith alumnae.

1927

When her mother took her to visit colleges, she thought “Vassar looked very snobby … and Wellesley, well, all the buildings looked the same. When we got to Smith, I loved the diversity and combination of old and new. I really felt at home there from the beginning.” The option of coeducation did not sway her. “I wanted the prestige of going to one of these women’s colleges. I’m still proud of them.”

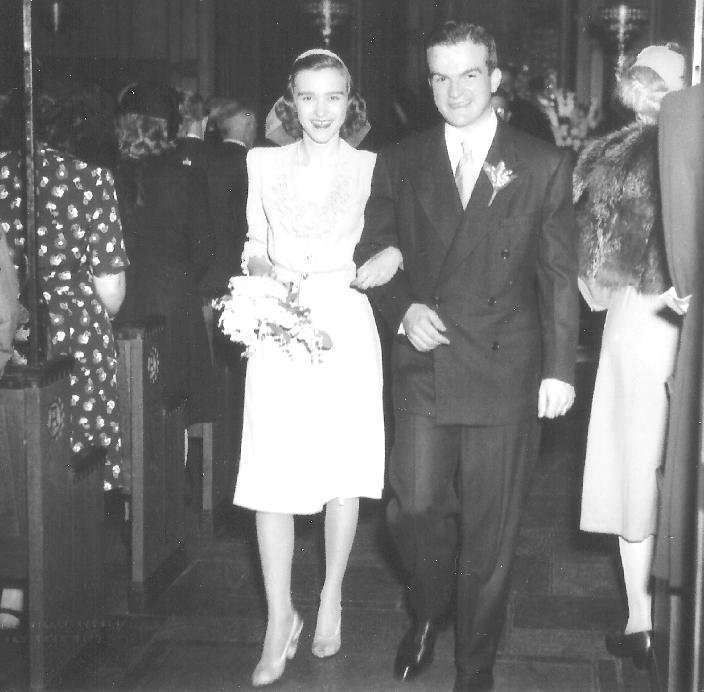

Joanne’s Smith class of 1945 was “accelerated,” since it was wartime, by including two summer sessions. In college she met Philip Von Blon, “a scholarship kid at Amherst” and “very smart.” The two were married in 1945 while Joanne was still at Smith. This situation, according to Joanne, was “simply horrible.” By then, Phil was living in New York; he was classified 4F so instead of going to war had a head start on the first of his three careers. He would come for a weekend during summer school. “We all lived in the Quad, and the smoking room was right outside the guest room, where he would have to stay. So we would trot into bed together with all these girls next door. I can tell you it was not conducive to a good honeymoon relationship.”

One or two professors at Smith had a lasting effect. “Mary Ellen Chase—I can still see her crossing back and forth in front of the room, proclaiming, ‘There are three types of lit-rachah: ma-jah, mi-nah, and medi-o-cah lit-rachah.’ She started me down this road. I’ve always been a voracious reader, and to this day I just swallow books whole.”

Philosophy classes also challenged her thinking. “Smith really set me on the path toward my belief system—or in my case, my unbelief system. In Mr. Lazerowitz’s philosophy course, we studied, among others, the transcendentalists. I thought Emerson was just fabulous, but then I got to Thoreau (I learned to pronounce it THOReau). I decided that was it—nature and I as part of one universe and our closeness to wilderness and animals.”

“That has stayed with me to this day, and I have fiercely called myself an atheist because it is true, and also because it is a word that shocks people.” Joanne’s grandson, when she told him she was an atheist, said, “Granny!” Joanne responded, “Look, if I told you I were a humanist or a secularist, it wouldn’t bother you a bit.” Joanne notes that “Our beliefs evolve over years, but I think Smith set me on the track.”

Another influence at Smith was Joanne’s “alter-ego” Joan Mitchell, a housemate and an artist who became a friend forever. “Joan said early on, ‘You have to look at modern art. You have to look and look and look, and then you’ll begin to understand.’ So Phil and I began to

look and look and look, and art turned into a lifelong interest and love.” Phil has been on the Walker Art Center board for years, and their own art collection is extensive.

After college, Joanne joined Phil in New York, where she went to work at Irving Trust Company at One Wall Street in the foreign operations department. Today, when her husband teases her about working for a bank, she tells him it paid $25 a week more than either Time or Newsweek, where she’d also applied. “In my day, it was the unusual woman who had a career. You went to college. You got married. You had children. And Smith Professor Hans Kohn used to say, ‘When you educate a woman, you educate an entire family.’”

Moving back to Minneapolis in 1945, Joanne put her English major to good use. For 12 years she reviewed books for the Minneapolis Star and Minneapolis Tribune. She was a founding member of the Center for Book Arts and also of nonprofit publisher Milkweed Editions. She was on the board of the Loft Literary Center and co-chaired that organization’s $1 million endowment campaign to match a Ford grant. Now, in 2008, she’s an active member of the board of Graywolf Press and a member of two book clubs—in Minneapolis and in Tucson, where the Von Blons spend winters.

Recalling the experience that spurred her other passion, social advocacy, she is still emotional: “In the late ’40s, I was asked by my mother’s friend to drive her two maids from Tucson to White Bear Lake [Minnesota]. They were black. And I think that changed my life. Driving those two nice women across the bowels of Jim Crow country and trying to find rooms and restaurants was absolutely horrifying. I learned how cruel people can be, and how generous strangers can be.”

Race relations became a focal part of Joanne’s social justice advocacy. In 1954–55 she chaired the mayor’s Joint Committee for Equal Opportunity, working on employment policies and housing. She won an award as a volunteer for the Urban League and lobbied the legislature in support of the Fair Employment Practices Commission. She and the director of the state NAACP were attending a University of Minnesota Board of Regents meeting, urging them to change discriminatory student housing policies, on the day in 1954 that the Brown v. the Board of Education decision came down from the U.S. Supreme Court. Joanne did public speaking and gave seminars on institutional racism in later years. She believes attitudes are changing now, “But I still think we are victims of stereotypical thinking.”

With “High Hope”

According to Professor Mary Ellen Chase,

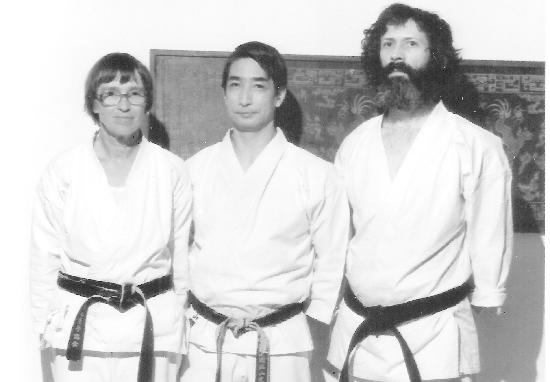

Receiving her 2nd degree black belt from Japan Karate Association

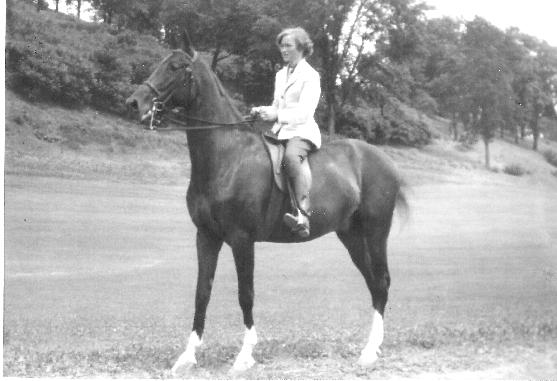

Joanne’s interest in the environment has led to work with several organizations, including the Nature Conservancy, where she has served on the board of the Minnesota chapter. It also led to wilderness travels—treks in the Sinai and all over Africa, scuba diving off the coasts of Israel and Australia, and solitary hikes in Wyoming. She even went to mountain climbing school in the Grand Tetons and climbed “The Grand.”

Two special moments, one celebratory and one frightening, surfaced during the interview. When Phil was chairman of the Minnesota State Arts Board, they were invited to Lyndon Johnson’s White House. “Everybody there was famous except us.” In the reception line, “We had to wear long gloves and take off one, and all we were allowed to say was ‘Good evening, Mr. President.’ Dinner in the state dining room was absolutely delicious. …As the President gave a toast, we were to stand up, and I knocked my chair over backwards with a crash. Gregory Peck, seated behind me, got up and picked up my chair, and of course I was horrified. After dinner, Lyndon Johnson came down off the dais, took my arm, and led me out as the group moved on to another room for dancing. It was the kindest gesture. I danced with Hubert Humphrey. It was all wonderful!”

Not so wonderful was a near-death accident in Alaska at the end of a small-boat trip with the National Resources Defense Council. A group of seven took a little skiff to get closer to a glacier. “It was such a lovely pale blue-green.” After they heard “a kind of hissing” noise, the ten-story top of the fascia broke away and came down on top of them, overturning the skiff and tossing them into the icy water—heavy clothes, life preservers, and all.

“FROOM, I’m thrown deep into this water and get stirred around like iced tea, then pop to the surface. I look out and there is a sea lion looking at me. I remember thinking two things: one, I am not frightened, and two, I am going to survive this.” She remembers seeing Phil, graycolored and with his head bleeding. “We were probably in the water 20 or 25 minutes—one man had a heart attack, another a punctured lung, and Phil couldn’t breathe because his camera strap was caught across his neck.” They were eventually rescued and all survived. The experience taught her that “At the time of a sudden death there is no fear.” This knowledge comforted her when her first grandson died tragically in a mountaineering accident.

Joanne’s words of wisdom for recent grads include these: “Keep your body moving and

Mr. and Mrs. Philip Von Blon, 1943

read, read, read.” Other words that she lives by are: “Show up, pay attention, tell the truth, and don’t become attached to an outcome.” She comments, “When you show up, you say yes to people who ask you, and by doing that you can open up whole new worlds. By paying attention, you are aware of what you love and where that can take you. And tell the truth— absolutely. Probably the most important is don’t become attached to an outcome; if you think you know how things are going to happen, you are closing yourself off to a lot of possibilities.”t “driving those two nice [black] women across the bowels of Jim Crow country and trying to find rooms and restaurants was absolutely horrifying. I learned how cruel people can be, and how generous strangers can be.”