11 minute read

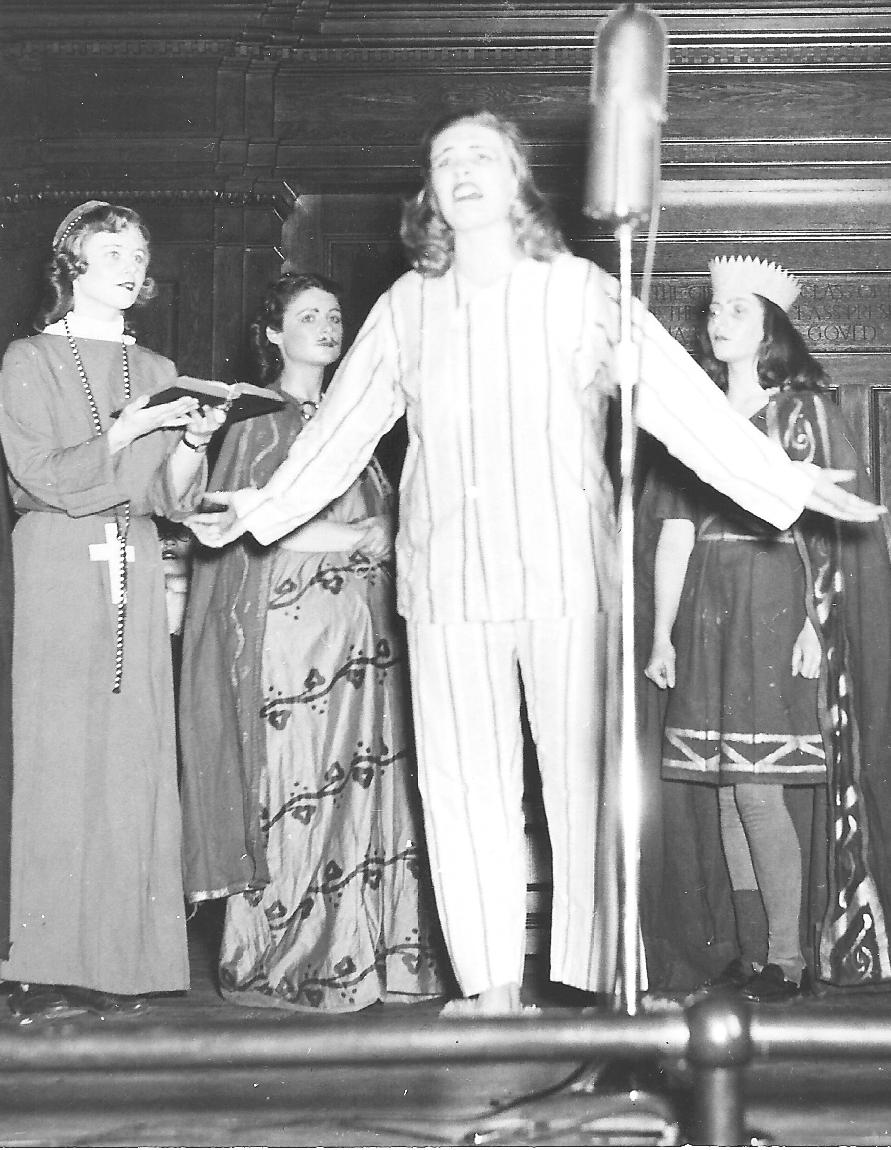

Ann Mitchell pflaum ’63

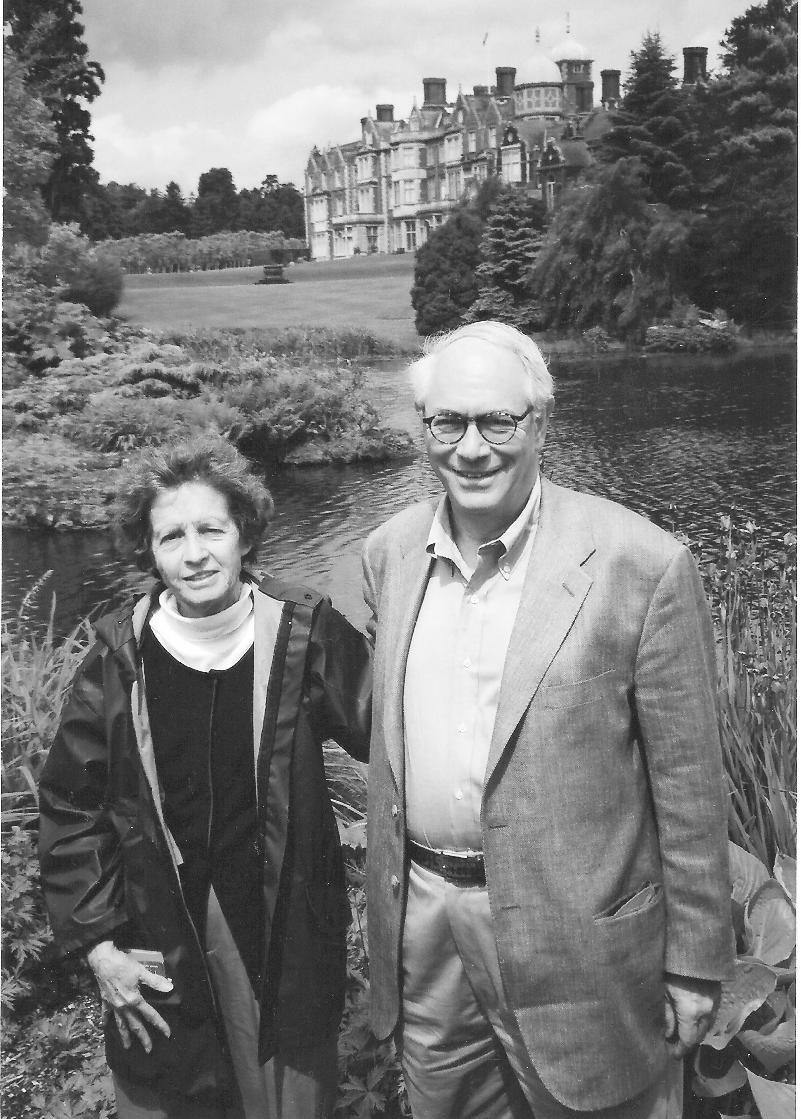

Ann at Sandringham in Norfolk, England, with husband Steve, 2006

A diminutive historian with an Expansive Sense of history

Advertisement

Ann Mitchell pflaum ’63

interviewed by mary ravlin gould ’50 on march 16, 2008

Ann Mitchell Pflaum is a font of information. She seems to remember everything and basks in the tales and details of the past as well as the present. It’s not surprising she has a doctorate in history and is writing her second history book.

Ann’s own family history in Minnesota began when several ancestors ventured west in the 1880s and ’90s. The Shevlins, an Irish family from Albany, New York, went into the lumber business here. Like other lumber operations, the company moved to the West Coast about 1910 when there were no more tracts of lumber to cut in Minnesota. But the Shevlins remained in Minnesota.

Ann’s maternal grandfather, David Tenney, operated a company that loaned money to farmers for seed and equipment. “When farming went ‘belly up,’ my grandfather lost everything. But since his wife, Florence Shevlin Tenney, had money, they were able to carry on.” Florence and David Tenney’s daughter Alice was Ann’s mother.

Ann’s paternal grandfather, Robert Mitchell, was initially in the saddle business, then in the shoe business. Even though he didn’t do well in the economic depression of the late 1800s, his son Bob, Ann’s father, was able to attend Harvard on a scholarship and later became a lawyer.

Ann’s mother had an unusual career for the 1930s. She was an artist. Her parents respected that and didn’t press her to go to college. She moved to New York City to pursue her painting career, holding a number of one-woman shows. Returning to Minneapolis at the end of the decade, she married Bob Mitchell in 1940. The Navy moved the couple to Massachusetts, where Ann was born in 1941. At 2½ pounds, she was the second-smallest baby ever to survive at the Boston Lying–In Hospital.

Alice painted three murals in Minneapolis which no longer exist—one for the Westminster Church Sunday School, one for the Jolly Miller room in the now defunct Nicollet Hotel, and the third for what was then called the Warner Hardware.

The values Ann was raised by were “balance, fairness, accuracy, and bemusement over the foibles of people. I learned early on that there aren’t many people who like to laugh at themselves, or like to laugh at their own culture. A great story I’ve always loved—it was probably apocryphal—is of the man who got up at a Minneapolis School Board meeting and objected strenuously to the introduction of foreign languages. ‘If English was good enough for the Lord Jesus, it’s good enough for us!’”

Ann recalls she was one of only three Democrats in the Northrop Collegiate Lower School at the time of Adlai Stevenson’s 1952 presidential run. “I remember crying all the way to school the morning after the election. I had

2001

a fistful of quarters because I had to pay off all my bets. Stevenson lost, and I learned then that your father isn’t always right.”

Ann’s introduction to Smith came through Northrop friend Susan Dalrymple Wilson, whose grandmother Bernice Dalrymple ’10 had gone to Smith. Her family had a big farm in North Dakota and Ann was invited to visit. “It was arranged that I was to travel there by train with Mrs. Bernice Dalrymple. I was in the fifth grade and instructed that I was to find out that Smith College is a wonderful place, ask nice things about it, and learn gin rummy.”

“Once on the train, Mrs. Dalrymple took me to the dining car. She was wearing a blue jacket with a demurely open front. The train lurched and the waiter spilled water all over her. Calmly, and without interrupting our conversation, she pulled the linen tablecloth off the table and put it down her front. I was agape. If a Smith graduate could handle such a catastrophe without a moment’s hesitation, Smith must be a good place to go.”

By the time Ann was ready to apply to college, she and her family had moved to California. Not many girls went to Smith from California, but it was her first choice, she applied early, and she was accepted.

She acclimated to her new experience with characteristic zest and enthusiasm. “I love history, and I loved the history department.” Ann’s advisor, Jean Wilson, was from Minnesota and had graduated from Smith in 1924. “I also studied geology with Marshall Schalk, and he was a lot of fun. I was not a great geology student, though, and I’ve never forgotten my first geology paper. It came back with C minus minus minus, with the minuses made to look like a trail of tears by the teaching assistant— meaning I knew no geology at all.”

Of her relationships at Smith, Ann says, “I lived in Chapin House and loved my roommates and friends. Our housemother was humorous Nannie Glidden from Maine. Also living with us in Chapin was Dorothy Bacon, an economics professor and Nixon supporter. I loved debating with her about Nixon!”

After graduating with honors from Smith, Ann earned her master’s degree at Harvard in 1964. She then returned to Minnesota, and in 1976 received her PhD in history from the University of Minnesota.

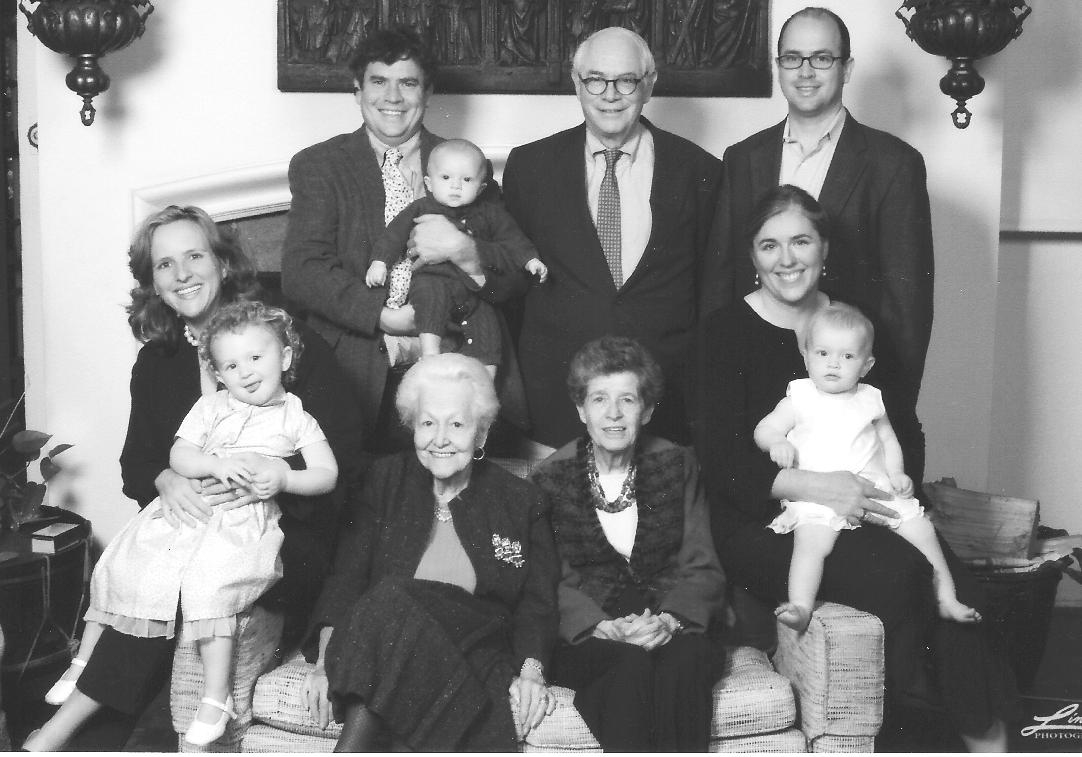

Meanwhile, in 1965, Ann had married fellow Minnesotan and Amherst alumnus Steve Pflaum. They have two sons, Bruce and Andrew, both of whom are married and live away from Minnesota. One daughter-in-law, Hanne Barnes, is a 1994 graduate of Smith. Ann reports finding her “little commutes” back

Celebrating mother-in-law Rosalynd Pflaum’s 90th birthday, 2007

and forth to visit her children and the three grandchildren “a great thing!”

Ann described many volunteer efforts during that period and later. “I tended to find my niche on boards, particularly on what are called nominating committees, their task being to look for new trustees. I could do that because I know a lot of people and have pretty good judgment, but I’m not the type who’s going to be chairman of the board or treasurer or secretary.”

Among her first board memberships was a stint with the Minnesota Opera. “That was a wonderful experience—the frenzied drama of opera plots made the academic life in my future more comprehensible.” She also served on the board of the Guthrie Theater. “Ah, that’s a cast of characters,” says Ann.

Ann claims that the most wonderful board experience she’s had was as an Alumna Trustee of Smith from 1977 to 1982. It was an interesting period at the college. “Smith was sort of in two worlds—the world of the students was a little more progressive than the world of the Alumnae Association [AASC]. Gertrude (Trudy)

Stella headed up the AASC and was very proper, set on form, and perhaps not particularly tuned-in to modern student life. I remember firsthand when the president of the Board, Dorothy Marshall, a Smith grad and faculty member at Boston University, joined Smith’s graduation parade wearing the traditional white dress but with a sprinkling of blue flowers. You would have thought from Trudy Stella’s expression that Dorothy had chosen to march nude! That’s when I realized it was kind of the end of an era.”

Fascinated by history, Ann has found a number of connections between the Smith world and Minnesota. “Ada Comstock came from Moorhead, Minnesota. She graduated from Smith in 1897, accepted an assistantship in the University of Minnesota’s department of rhetoric and oratory in 1900, and in 1907 became the first Dean of Women at the University of Minnesota. While at the University, Comstock helped persuade my great-grandfather to donate money for a Women’s Center at the University— Shevlin Hall.”

“There’s a romantic story about Comstock. Wallace Notestein, a professor of English history (initially at Minnesota and later at Yale) asked her to marry him. She said, ‘No, I intend to complete my career!’ She returned to Smith in 1912 as the first Dean of the College. From Smith, she was recruited in 1923 by Radcliffe to become its full-time president. (Smith would not have a female president until Jill Ker Conway in 1975.) In 1943, when Ada was 67 and both she and Wallace were retired (she from Radcliffe, he from Yale), Ada Comstock finally married Wallace Notestein and they lived happily until her death in 1973. That shows deferral is not a ‘no’ forever!”

“Another Minnesota connection who was quite extraordinary was Anne Morrow Lindbergh. She was at a Trustees dinner being introduced around. Someone said to her, ‘This is Ann Mitchell Pflaum, and she is from Minnesota.’ Mrs. Lindbergh and I are both about the same diminutive height. She looked at me, her eyes brightened, and said, ‘You know my husband was from Minnesota!’”

“Perhaps Smith alums who studied under Mary Ellen Chase don’t know that she also had a connection to Minnesota. She was probably the most beloved English professor at Smith, teaching Bible literature and history. She had earned her PhD at the University of Minnesota because she had been advised to travel here from Maine where she had grown up. This advice came because she had ‘pre-tuberculosis,’ and the Minnesota climate was then considered beneficial to health! At the University she realized she wasn’t going to be promoted beyond assistant professor, because the University was not ready in the 1930s to promote women. So she headed east to Smith, and soon after was made a full professor.”

Ann’s own professional life has centered on the University of Minnesota, where she is “a long-term administrator—I’m almost invisible.” Her career at the University began in the mid-’70s when they needed someone to do an

Ann’s volunteer experience with the Minnesota opera “was a wonderful experience—the frenzied drama of opera plots made the academic life in my future more comprehensible.”

institution-wide study for Title Ix, and it had to be done right away. “‘If you can come in Monday we’ve got a job for you.’ That was the turning point, and I never left the University.”

“Two years later we did a similar survey for what is known as Section 504, which involves access for handicapped students. I was on the Waseca campus visiting a welding lab when a man lifted up his welding visor and asked, ‘Why are you here?’ I answered, ‘We’re doing an inventory and studying access for persons with disabilities.’ He looked at me and said, ‘We’ve never had a disabled here, but we had a girl here once….’”

In 1988 Ann became Associate Dean of Continuing Education, which she found “most enjoyable.” Then, in 2000, “I had the chance, just before the University’s 150th anniversary, to be named University Historian and work on a biography of the institution, completed in 2001.”

Ann is now part of a team working on a new history of Minnesota, which will essentially replace Theodore Blegin’s Minnesota: A History of the State, published in 1963. In addition, she organized four public panels at the University to celebrate Minnesota’s 150th birthday. “They were our way of looking at the state’s past and at what may lie ahead.”

Ann’s love of Minnesota is palpable. “Minnesota is a place where, because of its relatively small size and compactness, people can cross barricades and have an impact unlike what’s likely in much larger cities. An example I love from our own History of Minnesota: A demonstrator told me that he and a professor went up to Jim Binger [former president and CEO of Honeywell] and talked to him about the cluster bombs his company was making. They had a very civilized discussion, and at the end of the meeting, Binger said he was going to continue making bombs but that the visitors had ‘every right to protest.’”

Ann’s no-nonsense advice for young Smith grads is the same she gives University students who wander into her office periodically. “I ask them to sit down with a paper and pencil and compute the year they will be 70. Then I say ‘Everything we read tells us that you will have five completely different careers by the time you are 70, so as you’re thinking about preparing yourself, think of what is going to give you the greatest flexibility—you’re going to need a lot with five different careers.’”

Though she claims not to be the board chair type, Ann has utilized her quiet leadership skills for the benefit of the Smith Club of Minnesota. She served as club president from 1975 to 1977. And in 1983, she co-chaired the 50th anniversary celebration of Smith Day in the Country, the club’s annual fund-raiser.

Still petite, Ann claims to do all her clothes shopping at Smith Day. She enjoys hunting for treasures from the past—not surprising for an historian.t

during an assessment of accessibility at a welding lab at a university of Minnesota campus, a welder told Ann,