17 minute read

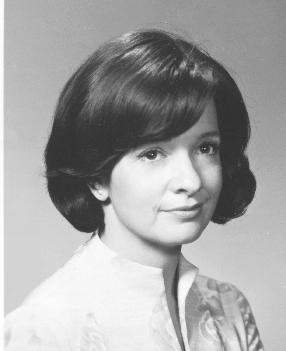

Marilyn Carlson nelson ’61

Marilyn (left) being honored by Queen Silvia and King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden

one of the true “Sheroes”

Advertisement

Marilyn Carlson nelson ’61

interviewed by Jane Anderson Howard ’75 and betsey whitbeck ’71 on June 17, 2008

“My sister and I were mortified when we were little” at having to model an item from their grandfather’s children’s clothing line. “It was something called a ‘tweener,’ which was a lightweight, one-piece suit that children were supposed to wear between winter and summer. It had a belt and a drop seat, so you didn’t have to take it off to use the facilities. My sister and I modeled it, and we had to drop the seat!”

So began our interview with Marilyn Carlson Nelson, Chair and CEO of Carlson, one of the largest privately held companies in the United States, employing nearly 160,000 people in more than 150 countries and territories. Marilyn is regularly recognized by Forbes magazine as one of the world’s 100 most powerful women and was named by U.S. News & World Report as one of America’s best leaders in 2006.Yet, talking with us in her penthouse offices, Marilyn is still the down-to-earth woman the Smith College Club of Minnesota has known since she chaired the club’s Alumnae Admissions Committee in the late 1960s. Over lunch, Marilyn shared stories of her family and upbringing, giving us insight into the process and events that made her an international leader.

“My maternal grandparents actually came to this country at the time of the American Revolution. Through the years they migrated west. My mom was born in Aberdeen, South Dakota. Her father was in the clothing manufacturing business. He manufactured farm overalls, then came to Minneapolis and started a children’s clothing company and had two clothing stores, one in Edina and one in downtown Minneapolis on Nicollet Avenue.” The embarrassment the Carlson girls felt at having to model the tweeners was forgiven “because he had clothing designers who made beautiful things for Barby [Marilyn’s sister] and me and we’ve both had a passion for clothes ever since.”

Marilyn’s paternal grandfather, Charles, left Sweden with his father, Carl Adolf, when he was four. “Of course my grandfather was a ‘Carl’s son,’ as was his father. They came to Minnesota and farmsteaded. Later Charles had a grocery store at 44th and France and my grandmother had the bakery next door.”

Her paternal grandparents cared a great deal about education. They had five children and planned to educate the boys. “My Aunt Aileen, the only daughter, went to Macalester College and graduated at the top of her class, but she had to pay her own way because the expectation was that a family without great means would help the boys rather than the girls. Aileen was always a kind of role model,” said Marilyn, because she was “very lively and interested in education.”

Marilyn’s father, Curt Carlson, attended the University of Minnesota, where he met her

mother, Arleen Martin. Curt was already a budding entrepreneur. “My dad had a paper route from the time he was very young. It’s part of the family lore that he subcontracted to his younger brothers and neighbors. He had a huge region of paper routes and he kept them throughout his years at the University. That was a very formative time for him.”

Also a hard worker, Arleen helped her father as a bookkeeper at the clothing factory. “Like a lot of women of that era I think she had more talent and skill than opportunities, the way the culture was at that point.”

Marilyn’s Swedish grandparents “had lots of energy and ambition and an inability to get hold of capital. I think that characterized my parents to some extent as well. They had a lot of courage and a lot of vision. When my father left his role at Proctor & Gamble, where he had been the top salesperson for the region, it was 1938, World War II was not far away, and people were beginning to get drafted. He had the courage to leave a well-paid job to found a company by borrowing money from his landlord. He’d go out and sell Gold Bond Stamps to clients. My mom had this little drum majorette costume—my grandfather probably made it for her. She was a pretty, smiley blond with blue eyes, and she would pass out the stamp books—that was their marketing plan! Even though my father got most of the attention, I would say my role models were a combination of them both—his energy and salesmanship, her faith, steadiness, and relationship building.”

Reflecting on values she learned growing up, Marilyn said, “I think caring and inclusiveness came from Hennepin Avenue Methodist Church. We attended the large downtown church because my father wanted us to think God was ‘big.’ But I thought it was great because it was a whole second social set. We’ve continued attending because we feel it’s good to pull children out of one setting where they may have one particular group of friends and put them in another. It’s an opportunity to develop different skills and another set of friends—an alternative.”

In 1957, during Marilyn’s high school years, her church was the first one in the country to become integrated, Marilyn explained. “Doing volunteer work in north Minneapolis, members became very close to families at Border Methodist, an African-American church. What is now International Market Square was being built, and the highway was going through Border, which was going to be razed. Our congregation brought them in with ours. It was extremely formative for me. I had been very involved with the church youth group, the University of Life, and was quite literal about the Bible—loving everybody.”

In Marilyn’s extended family, inclusiveness was the goal for holidays. “It was a very loving family. At Christmas we had 50 people, and my Grandma Carlson was always organizing

reunions with huge numbers—50, 60, 70 people,” she remembers.

Marilyn learned early to be an effective communicator and to handle herself deftly in front of an audience. “From the time I was quite young I took dance and drama lessons, and I learned a lot about teamwork. A small group of us were chosen for an acting troupe. We also did puppet shows for grade schools.” Marilyn found another positive effect of her theatrical experience: “It taught me, at a young age, that in theater you start to empathize because you put yourself into someone else’s shoes. It’s almost like in business—you do role-playing in order to learn how to model a certain activity.”

Early on, Marilyn developed a commitment to community activities. “I was a Brownie and a Girl Scout. To get my literature badge I read Shakespeare out loud with my best friend in a closet with a candle—and unfortunately got punished! I love Shakespeare to this day. I performed Romeo and Juliet at Amherst in my freshman year at Smith. I had to get special permission because we were supposed to focus on studies our freshman year. ”

The work ethic was another strong value in the Carlson home. “Work before you play” was a powerful message, according to Marilyn, who adds, “I don’t think we played very much.” But she doesn’t think the work ethic was the only driver in the family. “My grandfather started his own company and was an entrepreneur. My father was an entrepreneur. So it was more than work—it was the fun and the joy of business and being creative and engaged and involved.”

Marilyn’s recounting of why she selected Smith shows her emerging independence. “When I was quite young, my father brought home two T-shirts from a business trip, one that said Wellesley and one that said Vassar. He explained to my sister and me that if we worked really hard and got really good grades and were really smart, then these were the best women’s schools we could go to. I set as my goal to attend one of those schools.” But when Marilyn later went on a college tour, she changed her tune. “Mother fell in love with Wellesley. She thought it looked the way a college should—like a movie campus.” But Marilyn’s take was, “Everything matched at Wellesley, and what if I didn’t? I loved the fact that nothing at Smith matched! I figured that if the student body was as varied and eclectic as the campus, I had a pretty good shot at being successful there. Plus I thought I wanted to be a theater major. And at that time, Uta Hagen, a New York director and actress, was guest teaching at Smith. It sounded like, among the Seven Sisters, Smith would have the best

theater department. And finally, I had a wonderful interview. The woman I met with sat back and said, ‘You will come to Smith and you will not major in theater.’ I remember it exactly— and I thought that was really intriguing.”

As a student, Marilyn had plenty of academic guidance. “Certainly Miss [Dorothy] Bacon was a mentor. I took her economics course. My father said that since he was paying for my education, he should be able to pick one course. And so he picked economics.” But her father began thinking that economic theory at

Curt Carlson turning over the reins of the company to Marilyn in 1998

Marilyn’s father, entrepreneur Curt Carlson, began thinking that economic theory at Smith was rather liberal, so he became his daughter’s “mentor.” “he started calling me at night and giving me tutorials on the free-market system. I had to give up studying at the dorm.”

Smith was rather liberal, so he became his daughter’s “mentor” too. “Right about that time my father put in a WATS line at the company. He started calling me at night and giving me tutorials on the free-market system. I had to give up studying at the dorm and go to the library because it was the only place where I could avoid these lengthy calls.”

Before settling on a major, Marilyn decided she wanted to take her junior year abroad. She thought of going to London to study literature, but “Dad thought English literature was taught as well at Smith as in England.” She then thought about Paris for French literature, but “The French department pointed out that I was ‘just OK’ at French and the private-school kids were a lot better at French than I was.” She then went to Miss Bacon, who wanted her to major in economics and had what she thought was the perfect solution. “She suggested I major in international economics, go to New Zealand, and write about sheep and rural industries. Well, I was excited about economics, but New Zealand and rural industries?” So finally she and I negotiated Geneva, which actually changed my life, because I studied the beginning of the European Common Market. I went to the University of Geneva–Institute des Hautes Etudes Economiques et Politiques and wrote my thesis on the inevitability of Great Britain having to move away from her empire and closer to the Common Market.”

“At graduate school in Geneva, the international nature of the student body was again so enlightening. There were only a couple of women; it was mostly men who were sent from developing countries to prepare for diplomatic or government service. To this day I have friends from Egypt and Iran and various locations in addition to Europe.”

Like many Smith alums, Marilyn developed lifelong friendships with her roommates. She also feels fortunate to have become friends with other Minnesota alumnae in the years since graduation. She mentions Ann Pflaum ’63 (see interview on page 90), Margaret Wurtele ’67, Mary Taylor ’55, Sally Pillsbury ’46 (see interview on page 46), and Joanne Von Blon ’45 (see interview on page 40). “There is a Smith connection,” says Marilyn. “I went to some planning meetings at Joanne’s home, and I’ll never forget seeing on her wall that she was a member of the NAACP. That was before all that

went on in the ’70s. This inclusivity is so important to me.” Musing further, Marilyn remembers organizing things for the local Smith Club fund-raiser, Smith Day in the Country, in the early 1970s. “Copies of Our Bodies, Ourselves in brown wrap were delivered to the Pillsbury home for the sale. I remember asking Sally if she had the courage to put them out. That was a big deal—Our Bodies, Ourselves. Sally, of course, urged me to display the books.”

Mary Taylor and Marilyn created a program called Dare to Dream for the Minnesota club in 1995. “We wanted to raise Smith awareness among able high school students. The program included speakers who had realized their dreams, however improbable—the first woman in the astronaut program, the woman who started the first women’s bank, an actress who had become a producer, and others. We told the girls at the end that the presenters had all gone to the same wonderful school, Smith College, which believes in women and believes they can achieve! We told them, ‘We want you to take yourself seriously, think about your opportunities, and know that you can change the world.’ And we did get quite a few recruits out of this!”

Looking over a list of her many volunteer accomplishments, Marilyn says she was “in-between” in terms of the social movements of the time. “I came after Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem and before the marching. But I was here [in the Twin Cities], involved. I proposed the first black woman for membership in the Junior League, Joyce Hughes Smith. I had to go to Colorado Springs to the national meeting and defend the nomination in front of 2,000 women. One woman from the South said, ‘A dog can come in my front door, but not this person you are proposing to the Junior League.’ I was pregnant at the time and I remember thinking that I was going to have my baby on the spot. Joyce Smith’s membership did end up being approved.”

Marilyn remembers when including women on boards of directors was controversial; women usually led an organization’s auxiliary while the board of directors was all male. “Women had taken leadership roles during the war when there were no men here, but unfortunately that was seen as an aberration.” Marilyn was, she thinks, only the second woman president of the United Way, and she was the first female chair of the United Way Campaign.

“Living in one place your whole life gives you such a wonderful opportunity to do volunteer work. The thing about volunteer positions is that you have a lot of exposure. You raise money from corporations, you raise money from individuals, and you make a lot of friends—it’s natural networking.” For example, when organizing the Symphony Ball in the mid-’70s, Marilyn met Harry Holtz. “He was intrigued with my economics background. I was organizing all the finances and raising the money for the ball, and he invited me onto the board of First Trust—my first experience on a corporate board, and I was the first woman to serve there.”

As a corporate board member, Marilyn was in a position to examine the problems that developed as women entered top management. “There were women who felt they experienced sex discrimination when they were passed over [for promotion]. I watched women who were so full of anger in that period and some who really did self-destruct. What was hard for me was to differentiate between true discrimination and what was the honest selection of the best candidate. I committed to myself that if the day ever came where I was in a position to do so, I would create a real meritocracy.” Marilyn also

decided to emphasize skills assessment early on so women could learn what they would need for top management. “We could then get them ready, rather than have them be constantly bypassed, which is what was happening.”

Asked what Minnesotans need to do to secure our future, Marilyn said, “I think we have to bridge the performance gap in school between Caucasians and our minority populations. Also, it is essential that we start thinking longer term and make some sacrifices to create a transportation system that can get people to work. And, we have to be much more inclusive in our work settings. I’m particularly proud that at Carlson, we have about 49% women executives. We’ve been honored in the restaurant business as being leaders in that regard.”

Like her father before her, Marilyn has been active at the University of Minnesota. “I have been very passionate about starting the Center for Integrative Leadership at the University, a collaboration between the Carlson School of Management, the Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs, the Law School, and others. The idea is to create a graduate level effort that cuts across all these disciplines by developing case studies that examine ramifications of a problem from different points of view. There is an interconnectedness that these silos of study don’t take into consideration when training leaders.”

Marilyn had a number of Truths to pass on. “I was once given a piece of good advice: ‘The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.’ And I think that means knowing yourself, knowing what is really important to you, and being willing to stay centered.” Staying centered has surely helped Marilyn and Glen, her husband of 47 years, deal with many situations in their own lives. “One of our daughters died in an auto accident, our son had a liver transplant and we thought we were going to lose him, our youngest daughter is gay—these are all things that I did not expect to have happen in my life.”

Continuing her words of wisdom: “Anger can be emotionally destructive. Channeling it into positive energy is important. I’d say when you’re dealing with injustice, you can have righteous indignation but use that to make change.”

A final note of advice, especially for women: “Be patient. My daughter, when she was 16, found my love letters to Glen. She said, ‘Mom, you wrote Dad from Europe that you wanted to marry him, you wanted to have four children, you wanted to be an international diplomat, and you might want to go into your father’s business some day. If I had been Dad I just would have laughed getting all those letters.’”

With husband Glen and their grandchildren

The fact is, Marilyn has accomplished all those goals. “But I didn’t get it all done at once. I don’t think you sit at the beginning and plan out all your goals. You just get started. What worked for me was just to try to work with what I had at hand in such a way that I could be proud of the results, and then, if I felt something needed to be changed, I went about trying to help change it.”

Marilyn’s book, How We Lead Matters: Reflections on a Life of Leadership, was published in 2008, but she’s been recognized as a world leader for a long time. She was invested in the French Legion d’Honneur for her exemplary service to humanity. Sweden honored her with the Royal Order of the North Star First Class, presented by the King and Queen. The President of Finland presented her with the Order of the White Rose, Officer First Class. And her business and organizational leadership is exemplified by her service as a member of the board of directors for ExxonMobil, the Mayo Clinic, the Foreign Policy Association, the Center Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy, and the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

Her last comment in our interview focuses on this very oral history project undertaken by the Smith College Club of Minnesota: “There are lots of heroes, you know.” By celebrating the contributions of Smith graduates, Marilyn says, “You are finding the ‘sheroes.’” t