8 minute read

Kathleen Culman ridder ’45

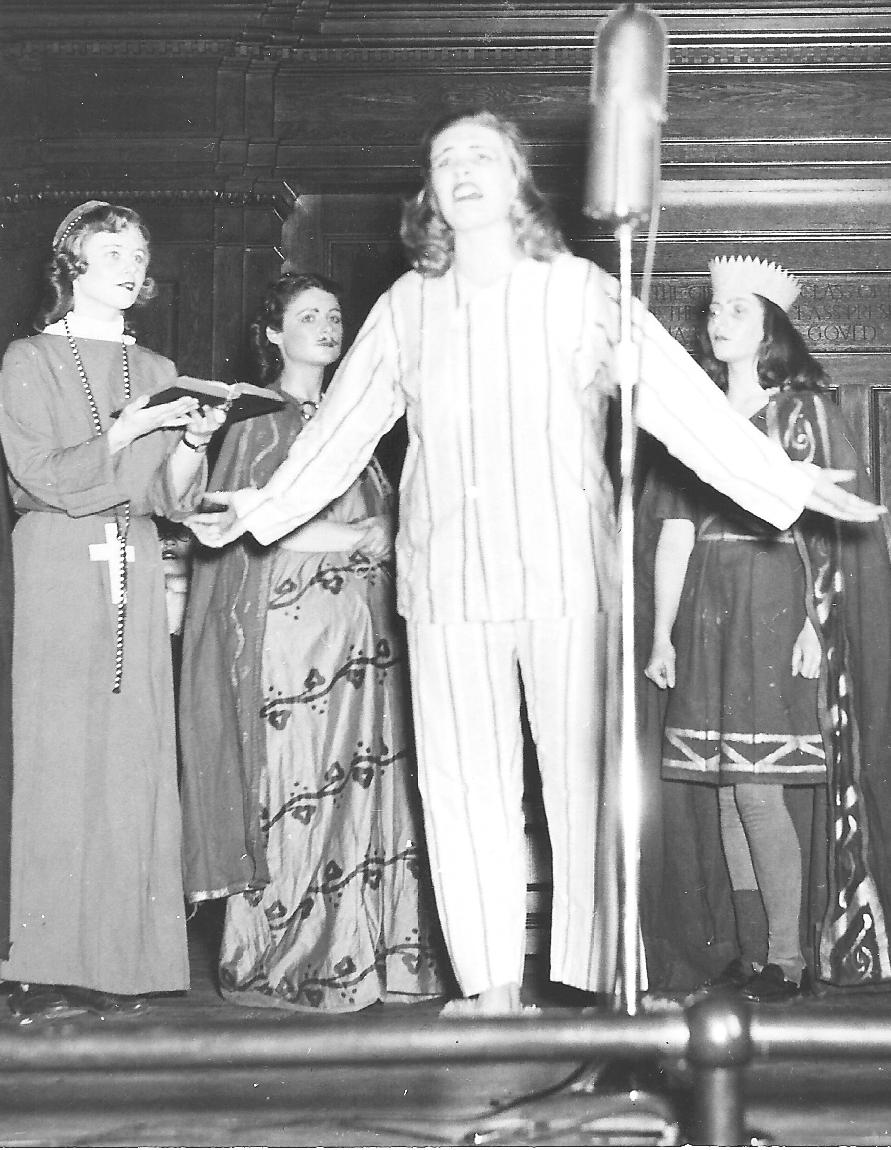

Kathleen (left) was lead skater and organizer of the Rally Day ice show, 1943

her feminist life

Advertisement

Kathleen Culman ridder ’45

interviewed by cynthia borowski dilliard ’79 and sophia lenarz-coy ’07 on April 5, 2008

Kathleen Culman Ridder still has the slight lilt of an Irish lass born in Manhattan in the 1920s. And she definitely still has the feisty determination that has served her well.

She credits her mother with instilling the values that have accompanied her through life: the value of a dollar and the use of connections. These days we might call that frugality and networking.

Kathleen inherited her spunky resolve from her mother, Muriel MacGuire Culman, who was adamant about giving her daughter opportunities she had not had. Focusing on Kathleen’s education, her mother arranged a scholarship to the elite Brearley School in New York as a step to acceptance at a Seven Sisters college. Kathleen’s aunt and mother ran a successful upscale women’s dress shop at 118 East 60th Street. Luckily, Elizabeth Cutter Morrow, former chair of Smith’s Board of Trustees and acting president of Smith in 1939, was a regular customer. Kathleen’s scholarship application was approved.

Does this mean Kathleen’s path was chosen for her? Hardly. She and her Brearley friends had already obtained a lot of inside information about the women’s colleges—they considered Bryn Mawr too intellectual, Vassar too social, and Smith just right for an all-around student who loved athletics.

All this was at a time when the Depression was a recent memory and World War II was looming. As Kathleen frankly puts it, “When I was growing up, your function was to find someone to take care of you … you were supposed to find a husband.”

Much of the two years Kathleen spent at Smith seems a blur of keeping her grades up for her scholarship and making friends. But she recalls organizing the ice show at Rally Day sophomore year. She had been a member of the Junior Figure Skating Club of New York and was able to bring quite a show to Paradise Pond, “complete with gypsy costumes, tambourines, a guest skater from New York, and the Smith graduation hymn as the opening music because of its perfect three-beat waltz rhythm.” The management skills she had absorbed at the dress shop, at a time when few young women had that opportunity, made organizing the event easy.

Within two years, she had met the man she wanted to marry, Rob Ridder, but there was a “problem.” He was a member of the Ridder newspaper family and was needed in Duluth, Minnesota, right away. Leaving Smith to get married, she promised her mother that she would complete her degree. The bride and groom moved to Duluth, where she quickly became acclimated. There were family friends

Kathleen says her regular presence at [gopher] football games reminds decision makers to maintain support for women’s athletics: “they see me; they know I’m here.”

waiting to meet her and the city size was very manageable. She remembers that Sinclair Lewis lived there and liked to stop by to play chess with Rob.

Once settled, Kathleen prepared to finish her degree. Applying to the College of St. Scholastica, she mentioned that she would need a little time off for the birth of her first child. The college told her they couldn’t have a pregnant woman on campus. So Kathleen applied to Duluth State Teachers College, now the University of Minnesota Duluth. “I never told them anything—I just signed up. I had a wonderful time. I even went on strike.”

Went on strike? Yes, it was in Duluth that Kathleen began her 50-some years of political activism. The successful strike was about getting the Duluth State Teachers College to become a branch of the University of Minnesota, allowing returning veterans to study there on the G.I. Bill. She finished her own degree there, proudly fulfilling the promise she had made to her mother.

In 1947, Rob was transferred by the radio and television part of the Ridder family business to the Twin Cities, which necessitated a household move. They settled in Dakota County, south of Minneapolis–Saint Paul. One day in early 1948 an acquaintance asked Kathleen to be the Republican Caucus leader in her area. She replied, “What is a Republican Caucus and how do you know I’m a Republican?” “You are,” came the answer. Kathleen accepted that role and by the fall of 1952 she was the county’s Republican Party chairwoman.

Kathleen’s political activities continued to expand. In the 1960s, she was deeply involved in the civil rights movement and worked for school integration. By 1974 she became active in the State GOP Feminists. She ran for a seat in the Minnesota House of Representatives in 1978 and 1982 but was unable to get the party’s endorsement. Both times she was defeated by men who were pro-life. Her pro-choice position was unpopular in the Republican Party, but she’s quick to observe that she was lucky enough to have a more secure financial foundation than most people from which to take an unpopular stance.

She held various offices within the city of Mendota Heights from 1969 to 1985. She also served on the State Commission on Human Rights from 1969 to 1972, represented District 15 on the Metropolitan Council from 1979 to 1983, and was a member of the State Board of Continuing Legal Education from 1975 to 1981. From 1982 to 1988 she was the public member of the accreditation committee for the American Bar Association, called the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. The William Mitchell College of Law recognized her with an honorary degree in 1985.

During the 1970s Kathleen did volunteer fund-raising at Breck School as well. When John Littleford became the school’s youngest headmaster in 1974, he quickly determined that Breck needed to focus seriously on fund-raising and asked Kathleen if she would start an office of development at the school. “I was thinking at

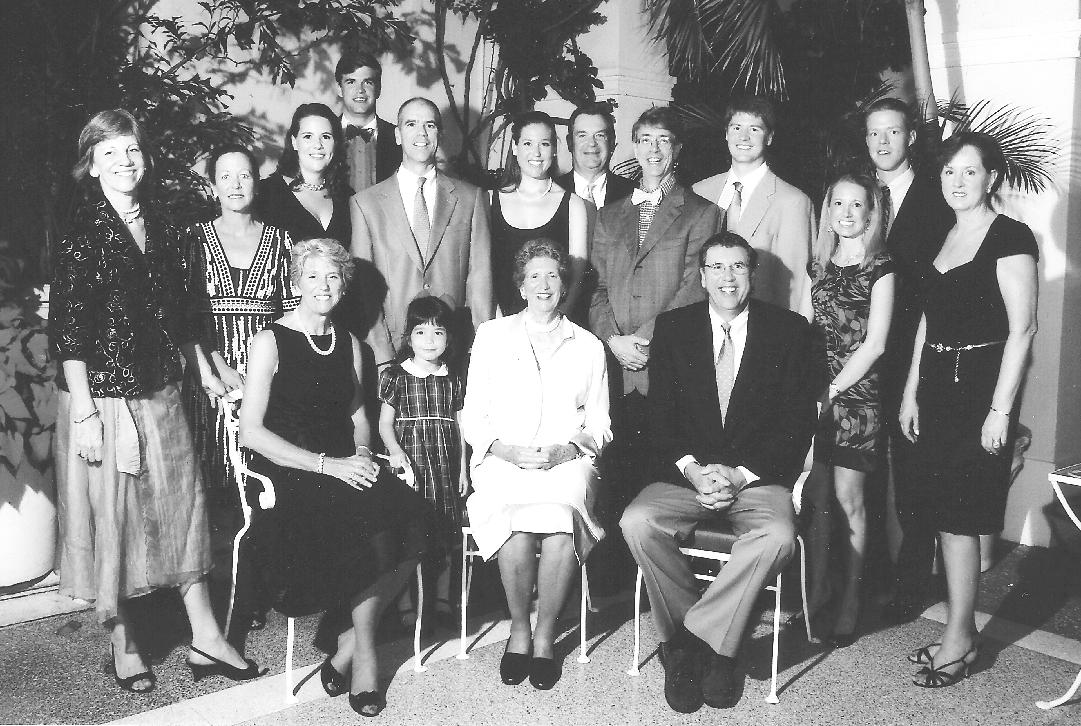

Christmas 2007

the time about getting a job, because I had become aware over time that volunteers did not have the same clout or status as paid professionals in organizations. So when John asked me this, I answered that I’d do it but I’d have to get paid. He said ‘How much?’ I quickly calculated and said ‘$5.50 per hour’—$2 more than I paid my cleaning woman. I knew I was worth it.”

But political advocacy was Kathleen’s real career, a line of work that is, of course, largely unpaid. “I didn’t need to work, but I felt “When I was growing up, your function was to find someone to take care of you … you were supposed to find a husband.”

2004

Sexism is alive and well.”

strongly that as a woman of privilege I had a responsibility to be politically and socially active in the community.”

In 1982, Kathleen worked with several other women to start the Minnesota Women’s Campaign Fund. The board comprised five Democrats and five Republicans, each of whom contributed $1,000. (One of the other founders was Perrin Brown Lilly ’45, a Democrat, whose interview is on page 36.) The money donated by board members was then used to raise further funds to support women candidates from both parties.

Kathleen had decided early on to work as a feminist within the political system. She felt that a disproportionate number of women were working within the Democratic Party, and, because her roots were in the Republican Party, she sought to effect change there. Her 1998 book, Shaping My Feminist Life: A Memoir, recounts her public efforts as well as many private moments in great detail. In an emotional scene from the memoir, Kathleen and her husband have an argument at an elegant hotel. She tells him: “I supported you all through your alcoholism, and now you are going to support me through my feminism!”

In another phase of Kathleen’s life, she turned her energies to avid support for women’s athletics, lobbying hard for funds after the passage of Title Ix in 1972. She is still on the University of Minnesota Intercollegiate Advisory Council and continues to regularly attend Gopher football games. She says her presence reminds important decision makers to maintain support for women’s athletics: “They see me; they know I’m here.”

As a result of her activities and contributions to the University of Minnesota, she received the Alumni Service Award in 1995. The Regents Award followed in 2002, presented on the day the Ridder Arena and Baseline Tennis Facility opened on campus. Ridder Arena is home to three-time national champion Gopher Women’s Hockey, the first women’s collegiate hockey program to play in a facility dedicated to the sport. Kathleen is also a life trustee of the University of Minnesota Foundation.

For Kathleen, the decision to move to Minnesota was one of the major turning points in her life. She readily admits that she would not have had the same opportunities for community involvement had she stayed in New York.

Asked for advice for young women, Kathleen had several observations to share. She talked passionately about the importance of setting up social networks, learning how to market yourself (“what you need is credentials, credentials,

credentials”), and making sure your marriage is a 50-50 deal. She said the feminist movement, which has never successfully incorporated African-American women, needs to reach out to new immigrant groups such as Somali women. She stresses the need for recent graduates to remember ours is a capitalist society, “and that isn’t going to change in your lifetime.” Kathleen offers warnings too: “Don’t think it’s been settled. Sexism is alive and well. Don’t go in thinking it’s going to be a rosy future.”

She speaks critically about Smith for its failure to produce more female leaders at the national level. “How many Smith women are in Congress?” Kathleen asks, noting that Hillary Clinton went to Wellesley. She sees an urgent need for women to become more engaged in politics and thinks that in some very important dimensions, “Smith has lost its way.” She believes the college must shift its focus from inward to outward. Then, she hopes, she’ll be able to name several Smithies in Congress and maybe even one in the White House.t