7 minute read

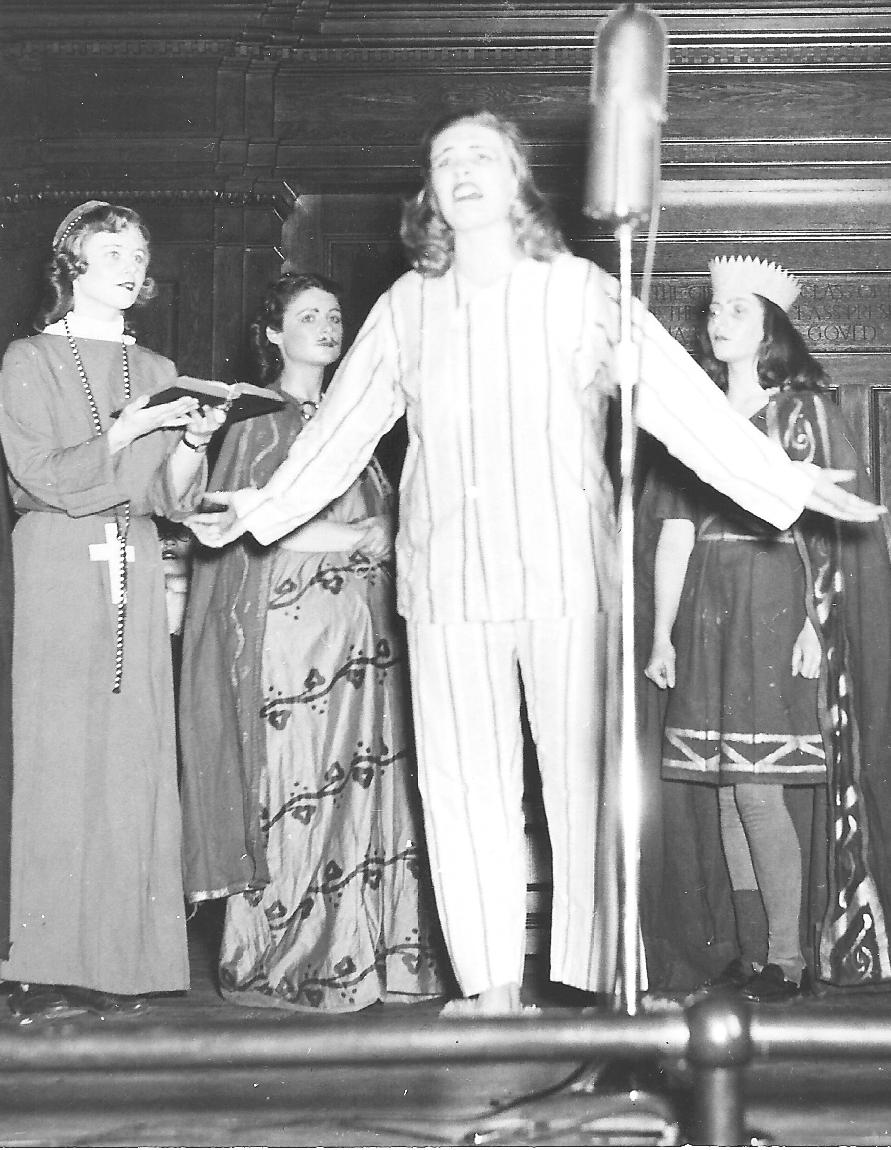

Helen Woodhull kramer ’34

Helen demonstrating a dance move from her senior class play, The Bacchae, 1934

“take the time to Extend yourself!”

Advertisement

Helen Woodhull kramer ’34

interviewed by barbara bockhaus Klaas ’74 and mary ward gover ’56 on may 6, 2008

At age 95, Helen Woodhull Kramer truly lives her own advice to “Keep active, keep interested, keep working on the things that matter.”

Although we arrived 15 minutes early for the interview, Helen was ready and greeted us with a bright smile. A slim, upright woman with short white hair, smartly clad in black slacks and turtleneck under a bright pink vest, she promptly urged us to call her by her first name.

Being positive, optimistic, active, and caring— Helen’s core values—were taught her by her mother and her church. Helen’s parents came to Minnesota from Pennsylvania, hoping her father would find a job through a friend. The couple settled right near Westminster Presbyterian Church. “They got attached to Westminster right away,” she commented. The church, which reinforced the family’s values, would play an important role in the family’s life and in Helen’s.

Unfortunately, Helen’s father was unable to hold a job for very long. Consequently and much to her husband’s discomfort, Helen’s mother, Agnes, had to support the family, first selling a “beautiful line of girls’ clothes” to clientele near Lake Minnetonka and later giving talks for the Foreign Affairs Council. “We weren’t really poor, but we were frugal so we could do the things that mattered.”

Helen’s parents set high standards for their four children. They were gracious hosts, and Helen’s mother taught her daughters etiquette. The words “quit,” “ain’t,” and “sure” were not allowed. The children were urged to be kind to others who were not like themselves, and to avoid making others unhappy by criticizing.

The children also were taught the value and importance of learning. As a young man, Helen’s father had been unable to follow his family’s tradition of attending Princeton because of the death of his father. Instead, he was tutored at home by his grandfather and uncles. Once in Minneapolis, he continued to study geology, archaeology, and architecture on his own. He started a club for teenage boys— the Fujiyama Club—through Westminster.

Helen’s mother came from a family, the Pattons, where two of the three sisters attended Smith, Agnes graduating in 1901 and her sister Helen in 1899. When it was time for Helen Woodhull and her sisters to seek out colleges after attending Central High and Northrop Collegiate, Agnes told them, “Girls, you have only two choices: either the University of Minnesota or Smith.” Helen and her older sisters, Patsy and Caroline, all chose Smith. Their education was financed by an inheritance from Helen’s maternal grandfather, John W. Patton, a professor of law at the University

of Pennsylvania—funds her mother had set aside for the children’s education and for travel.

Helen recalls that she had “a wonderful education” at Smith, which she commented then cost $490 for tuition and board! The college opened her eyes to new worlds of art and art history, and she took a wide variety of courses, including one on Paradise Lost, one in geology, and several in Latin before majoring in history. Helen remembers taking literature classes from Mary Ellen Chase. “She was like nobody else in the world. She’d walk like somebody on a deck; she looked like a sailor and filled a class period with tales old and new!”

Helen also liked the house system, and somewhat sheepishly mentioned that their evening meals in those days were served by maids. Some of the foreign students who lived in Helen’s house (Martha Wilson) became real friends. The housemother, a wise and witty Scotswoman, was a fine advisor, and everyone admired Smith President William Allan Neilson.

She remembers being invited to spend Thanksgiving in New Haven with her friend Molly Bennett. There, they attended a dance. “I had a white satin dress and blue gloves and I was the belle of the ball. … The Minneapolis Yalies discovered I also was from Minneapolis so they gave us a rush!”

Although her parents were lifelong Republicans, Helen came to support Franklin D. Roosevelt, seeing him as more caring for those in need during the difficult Depression years. Helen even became president of the very liberal Why Club at Smith. In fact, when asked what events or period most changed her life, Helen named living through the Depression, FDR’s improving the economy, and World War II.

After college Helen taught in various private schools since she did not have a Minnesota teacher’s license. Working at one school in particular she found to be a very boring experience. “I quit! Mother’s not here, so I can say that word now!” Another year, coming off the boat from a European voyage—a trip she paid for by renting out books aboard ship—she accepted a teacher-exchange job in Connecticut. That turned into “three wonderful years” at Spring Hill, an extension of the experimental Little Red Schoolhouse movement in New York.

Considering the important role the church played in her upbringing, it was no surprise Helen was active in religious activities at Smith and later. In the 1960s, Helen worked with the Westminster Task Force for Race and Religion, including participating in a protest march down Plymouth Avenue in north Minneapolis. And she broke the gender barrier in the governance of her church. Among her proudest moments was being elected an Elder—one of the first two female Elders at the church. She also served on the board of the YWCA, helping with outreach programs to the minority and low-income populations of the city.

Music was another key part of Helen’s life. She enjoyed playing duets with her piano teacher and singing in the choir at Smith. During her senior year, while home in Minneapolis, she

Five Smith women, Ivy Day 1931: Helen Woodhull (Kramer) ’34, sister Caroline Woodhull (Ernst) ’31, sister Patsy Woodhull (Raudenbush) ’28, mother Agnes Patton Woodhull ’01, aunt Helen Patton Beers 1899

memorably met famed violinist Nathan Milstein at a tea, after which he asked her for a date. They went to a movie, and “Oh boy, his hands were active!” After Milstein brought her home, Helen’s father came downstairs in his bathrobe to tell Milstein—as if he were any ordinary young man—that it was time for him to go home.

When Helen was close to completing an M.A. in education specializing in remedial reading, violinist Henry Kramer came to Minnesota to play in the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. Within a few weeks, they were engaged. This was a turning point in her life. She finished her degree right after they were married, but was happy to set aside her profession to focus on her husband and the children who soon followed.

She regrets never obtaining a Minnesota teacher’s license, which would have allowed her to teach in the public schools, but she did use her talents by teaching piano and mentoring. Years later, she plunged into helping others less

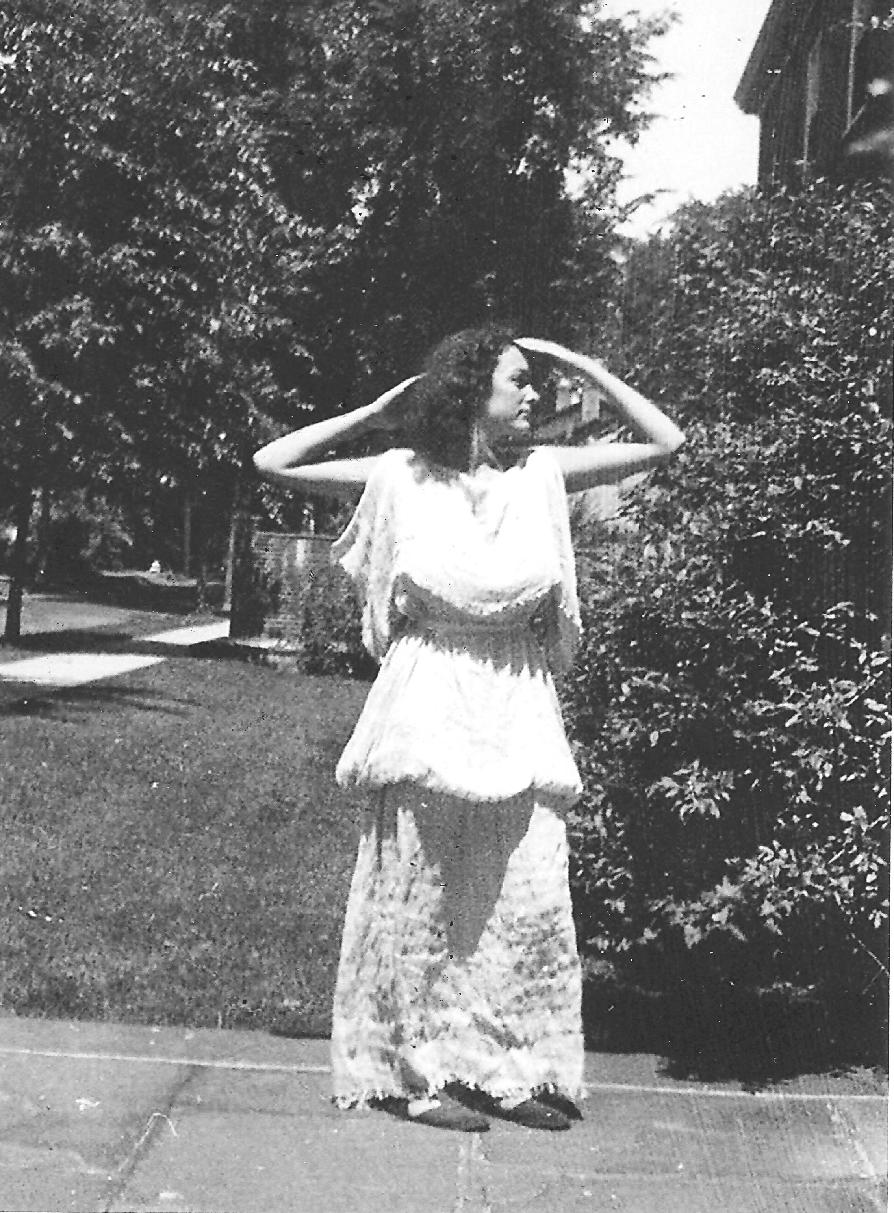

Ready for college in new clothes, summer 1930

fortunate than she, including trying to get high school dropouts to finish their education.

Living since 2000 in an assisted living facility in Stillwater, Helen exudes interest in the world around her. She continues to take classes in new areas, and has been participating in writing classes for about 10 years. Her coffee table is covered with books, including bestsellers Water for Elephants and Thirst. She’s concerned about current issues such as global warming and immigration. She admires as visionaries the framers of the Constitution, Rachel Carson, and Gandhi.

Asked what advice she would give to Smith graduates today, Helen quickly said, “Keep active. Keep interested. Keep working on the things that matter. Watch the country’s—the world’s—future. Be accepting but don’t refuse to look at new ways.”

Helen rounded out our time together by relating a story illustrative of her philosophy. While taking an art class at Smith, she told the professor she did not like the “new” art, especially Cezanne. Her professor suggested she stop in at the art museum every time she went by and look at the Cezanne there. She did, and after studying it for a while found that she liked it. “In other words, take the time to extend yourself. This is good advice!”t “Keep active. Keep interested. Keep working on the things that matter. Watch the country’s— the world’s—future. be accepting but don’t refuse to look at new ways.”