Yoni Angelo Carnice received a Master’s in Landscape Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2020. His thesis explored how the design of a mountain trail and gardens weave together stories and ecology of San Bruno Mountain and the Filipino diaspora in the San Francisco Bay Area. Under the Douglas Dockery Thomas Fellowship in Garden History and Design sponsored by the Garden Club of America and the Landscape Architecture Foundation, Yoni is currently conducting research around the work of artist and gardener Demetrio Braceros at Cayuga Playground in San Francisco. The following is an outline of the ongoing work to preserve the cultural legacy of the park.

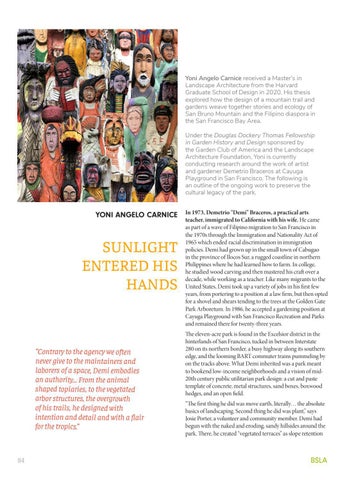

YONI ANGELO CARNICE

SUNLIGHT ENTERED HIS HANDS

“Contrary to the agency we often never give to the maintainers and laborers of a space, Demi embodies an authority… From the animal shaped topiaries, to the vegetated arbor structures, the overgrowth of his trails, he designed with intention and detail and with a flair for the tropics.”

84

In 1973, Demetrio “Demi” Braceros, a practical arts teacher, immigrated to California with his wife. He came as part of a wave of Filipino migration to San Francisco in the 1970s through the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 which ended racial discrimination in immigration policies. Demi had grown up in the small town of Cabugao in the province of Ilocos Sur, a rugged coastline in northern Philippines where he had learned how to farm. In college, he studied wood carving and then mastered his craft over a decade, while working as a teacher. Like many migrants to the United States, Demi took up a variety of jobs in his first few years, from portering to a position at a law firm, but then opted for a shovel and shears tending to the trees at the Golden Gate Park Arboretum. In 1986, he accepted a gardening position at Cayuga Playground with San Francisco Recreation and Parks and remained there for twenty-three years. The eleven-acre park is found in the Excelsior district in the hinterlands of San Francisco, tucked in between Interstate 280 on its northern border, a busy highway along its southern edge, and the looming BART commuter trains pummeling by on the tracks above. What Demi inherited was a park meant to bookend low-income neighborhoods and a vision of mid20th century public utilitarian park design: a cut and paste template of concrete, metal structures, sand boxes, boxwood hedges, and an open field. “The first thing he did was move earth, literally… the absolute basics of landscaping. Second thing he did was plant,” says Josie Porter, a volunteer and community member. Demi had begun with the naked and eroding, sandy hillsides around the park. There, he created “vegetated terraces” as slope retention

BSLA