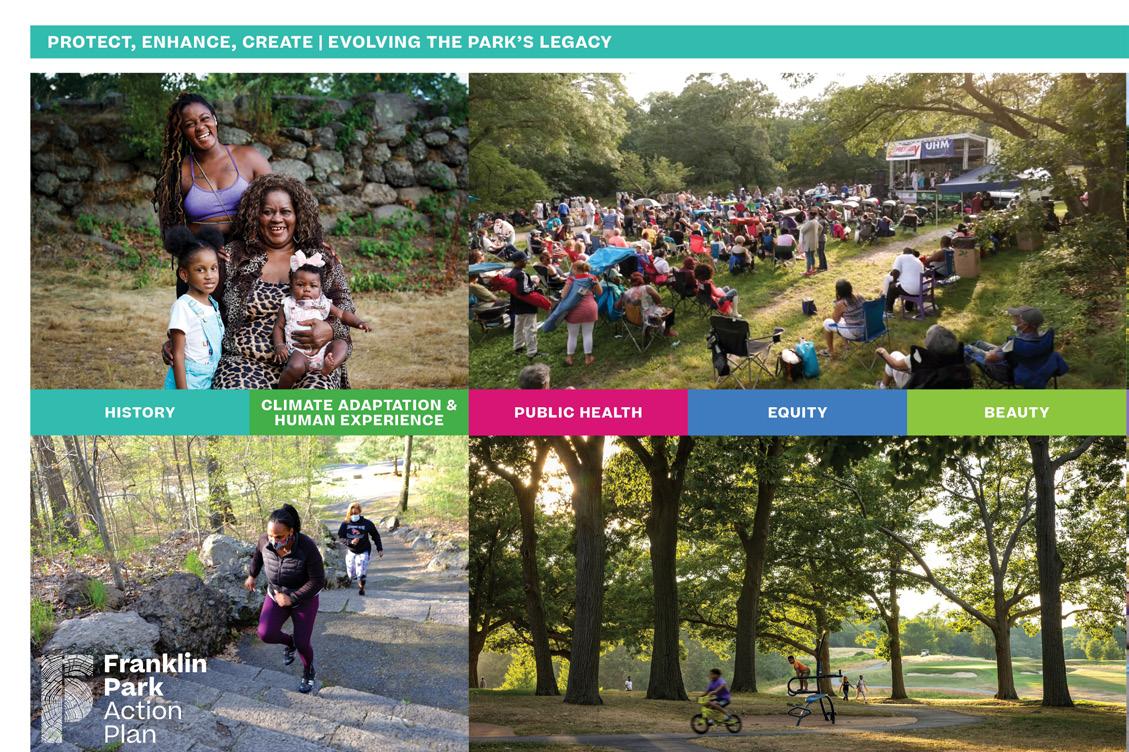

ON THE COVER

“The

climate is terrifying if you stare it down, but there’s a lot of opportunity for new ideas and innovation and making our communities more beautiful. - Julie Wormser

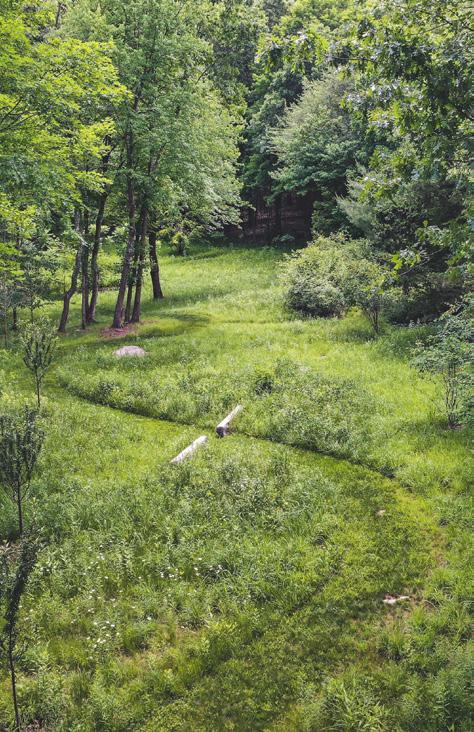

Kincaide Park, Quincy, Massachusetts, performing as intended after days of heavy rain, March 2024. The constructed wetland is full: storing, slowing & filtering water, as kids play. Bishop Land Design.

#ThisIsLandscapeArchitecture

BSLA

Fieldbook. Issue

13. Theme: Climate

. Including the 2022 + 2023 BSLA Design Awards. Online at www.bslafieldbook.org

Guest Editors, “CLIMATE”

Liz Luc Clowes, ASLA

Jason Hellendrung, ASLA

Scott Bishop, ASLA

Jessica Montgomery, Student Affil ASLA

The BSLA Fieldbook Editorial Advisory Board

Tom Benjamin

Matthew Cunningham, ASLA

Aisha Densmore-Bey

Michael Grove, FASLA

Nicole Holmes

Jessalyn Jarest, ASLA

Kate Kennen, ASLA

Robert Marzilli

Patricia McGirr

Liza Meyer, ASLA

Barbara Nazarewicz, ASLA

Trevor Smith

Tim Tensen

BSLA Executive Committee

Luisa Oliveira, ASLA, President

Kaki Martin, FASLA, Past-President

Michelle Crowley, ASLA, President-Elect

Maria Bellalta, FASLA, Trustee 2022-23

Tom Ryan, FASLA, Trustee 2023-25

Jef Fasser, ASLA, Treasurer

Members at Large

Liz LucClowes, ASLA (through 2024)

Jessalyn Jarest, ASLA (through 2025)

Carolina Carvajal, ASLA (through 2026)

Haipeng Zhu, ASLA (through 2026)

Managing Editor + Executive Director

Gretchen Rabinkin, Affiliate ASLA; AIA

Western Mass Section Chairs

Nate Burgess, ASLA

Jeff Dawson, Affil. ASLA

Maine Section Chairs

Johanna Cairns, ASLA

Steven Mansfield, ASLA

The Boston Society of Landscape Architects is the first local chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects. Since 1913, BSLA has served as the landscape architecture professional community of Massachusetts and Maine.

Today BSLA includes 700 landscape architects, students, and emerging professionals from Portland to Provincetown, the Berkshires to New Bedford, Bar Harbor to Boston.

This book is a community production.

Fieldbook is published by the Boston Society of Landscape Architects. Articles do not necessarily reflect the view or position of the BSLA Executive Committee (ExComm) or BSLA members. Permission to advertise does not constitute endorsement of the company or of the advertiser’s products or services. No part of this publication may be reproduced in print or electronically without the express written permission of BSLA. ©2024

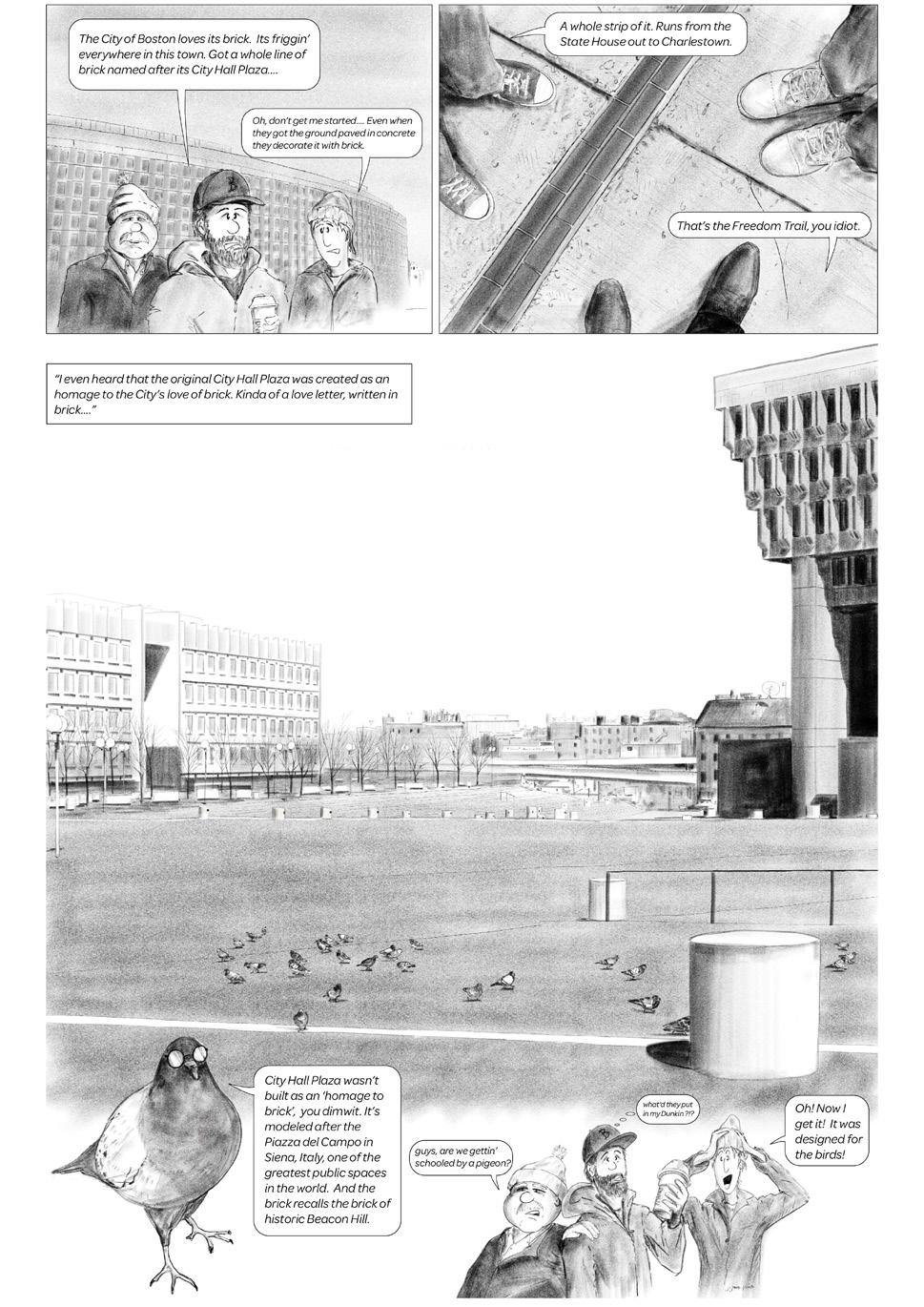

CONTACT

Boston Society of Landscape Architects PO Box 962047 Boston, MA 02196

The Editorial Board aims to reflect the diversity of our chapter in every way.

If you’re interested in participating on the Editorial Board, or have comments, questions, critique, or suggestions about Fieldbook, we want to hear from you. Please be in touch! Email gretchen@bslanow.org

www.bslanow.org email chapteroffice@bslanow.org

instagram @BSLAOffice linkedin @BSLA

1 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

Boston Society of Landscape Architects thanks our annual partner sponsors. The support of these companies helps make possible the events, programs, and initiatives of BSLA as we work to support landscape architedcts and advance landscape architecture in Massachusetts and Maine. Their generousity is appreciated.

Thank you.

2 BSLA BSLA / PARTNER SPONSORS

Dear Members & Friends,

Global Warming, Climate Change, Climate Crisis. Regardless of the term used throughout the years, awareness has exploded in the face of recent and widespread catastrophic weather. The events we have been warned about are coming to fruition and harming communities everywhere. Finally, people accept the need to act and advocate that slow-moving governments and organizations come up with solutions quickly.

As Landscape Architects, our medium is nature and our knowledge base is rooted in science. We have always been keenly aware of environmental shifts. Soil, water, vegetation, temperature, air, geology, and geography are the basic elements of our work. The recent “green infrastructure” and “nature-based solutions” buzzwords have described our profession since its beginning. Put in popular parlance: Landscape Architects are the OG’s of nature-based solutions.*

This issue of Fieldbook contains important conversations on the changing climate and the work we do to respond and build resilience to it. The book in your hands also features two years of our chapter’s award-winning projects from practitioners in Massachusetts and Maine. Throughout the Design Awards, you’ll see elegant approaches to dealing with too much water and too much heat, capturing carbon, and increasing biodiversity in ways that offer beauty and delight at every scale. And these pages are just the beginning. We’ve had such an outpouring of response to this topic that a second edition is already in the works, coming out later this year.

I encourage you to read Fieldbook CLIMATE and pass it on. Give it to someone who doesn’t know what Landscape Architects do. Give it to an elected official in your town or city. Give it someone considering a career in landscape architecture or someone with no hope –or an abundance of hope– for our future.

Landscape Architects are poised to offer solutions to the present crisis, and we are being called to do so at all scales. This is our time. This is the time to lead with landscape.

Luisa Oliveira, ASLA President Spring 2024

Luisa Oliveira, ASLA President Spring 2024

*OG: “Original Gangster.” Slang, someone or something that is an original or originator and especially one that is highly respected or regarded (Websters Dictionary).

In the photo: BSLA President Luisa Oliveira (at left, in red pants) in conversation with Professor Patricia McGirr and students at University of Massachusetts Amherst Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, February 2024.

3 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT / BSLA

3 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

Editors, when did you first feel the climate crisis?

Jason: June 12, 2008. I was in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for the project kickoff of the Cedar Rapids Riverfront Plan, which aimed to link downtown to the riverfront. I was a principal at Sasaki. We were in City Hall on Mays Island in the middle of the river, and by the end of the meeting, the city was flooding. We were stranded in our hotel and had to be evacuated. And for the next two and a half years, we helped Cedar Rapids rebuild their city after this flood. It was about a physical flood, but really about the impact on the town, community, and neighborhoods. We emphasized engagement. And soon after that came Superstorm Sandy and Rebuild by Design. Then, Preparing for the Rising Tide and the Boston Living with Water International Design Competition and, ultimately, Climate Ready Boston

Jess: I’m 20. I haven’t lived through anything other than the climate crisis. I grew up in Atlanta, a city I’ve only ever heard called ‘Hotlanta’ by outsiders. But yeah, it’s hot. My mom taught me that the sweltering summer onslaught was a new norm. Unease seeping through her sentences into the thick humidity, she’d tell me days like these hanging around 95° represented maybe a week of the year in the ‘90s. The understanding would punch me in the gut every time; I couldn’t remember a year with less than a month of such days. Climate change isn’t a distant contrast for me to apprehend; it’s the unfortunate backdrop of my generation’s existence. The scorching summers, ever more erratic weather, flood after flood, kids and older people confined indoors– these memories punctuate my conception of my hometown and its future. Things have gotten worse, but they can get better. It’s been two decades of relentless heat; how will we work to prevent another?

Liz: I was in Harvard Forest, in Petersham, Massachusetts. I was standing on top of the flux tower, which measures the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. As a conservation commissioner in my town, I was in an in-depth training to learn about ecological solutions. I had already made a mid-life career pivot to becoming a landscape designer. I remember climbing up and up and up, standing 70 feet in the air, overlooking a hemlock forest – a forest under threat from climate change and disease and insects. Standing on the flux tower, I felt a powerful emotion that the forest around me may not be here for long, and then I thought that somehow, in my short window on this planet, I could do something about it. I felt the potential power in collective knowledge. That’s when I enrolled in the Master’s in Landscape Architecture program at the Boston Architectural College. Now, a few years later, I work for the Boston Food Forest Coalition and am on the boards of Speak for the Trees and BSLA as I work toward licensure.

Scott: I grew up in the suburbs of Michigan. An oak forest abutted the housing developments, and a stream ran through it, common to the glacial topography of Michigan. I played in the forest; that was my Nintendo. By third or fourth grade, I was aware of environmental issues. I started to read the Whole Earth Catalog and subscribed to Garbage Magazine, which asked, “What are we doing with all this waste on the planet?” We were close to Lake Michigan. I used to watch the giant icebergs float by as it got warmer in the early spring, and then slowly, those went away. I was a swimmer and sailor, too, and I became interested in water systems, pollution, and climate and how they are all connected. I went to college for marine biology, realized I was a generalist, and then became a human ecologist and then an applied human ecologist – a landscape architect. I am the immediate past chair of the American Society of Landscape Architects’ Climate Action Committee (now the Biodiversity and Climate Action Committee) and currently serve as the subcommittee chair of BCAC’s Climate Action Network.

Fieldbook CLIMATE aims to add New England layers to the larger ambition of the ASLA Climate Action Plan.

In this photo: the Harvard Forest from the top of the flux tower, taken by Liz LucClowes.

4 BSLA

Dear Reader,

Do you remember when you first felt the climate crisis?

Our title as ‘designers’ acknowledges our role in environmental alteration and deterioration yet also positions us to intervene within these deteriorated systems.

Fieldbook CLIMATE entangles in provocative discussions as we consider climate impact on gradients: Gradients of known and unknown. Of science and feeling. Of despair and hope. Of beauty and control. Of work that has been done, is being done, and that might be done.

We begin Fieldbook CLIMATE with conversations about changing practice, forests, connecting across boundaries, and tools and tactics to measure impact. These discussions offer a range of voices and views, aiming to celebrate and catalyze as we collaborate to move the work of landscape architecture forward.

In every way, these pages are just the beginning. Fieldbook CLIMATE will be two issues (at least!). Thanks to the outpouring of interest from you, our landscape architecture community, this book in your hands will be followed in a few months by another.

The essays, discussions, and Design Awards in these pages are only the tip of the proverbial iceberg of work underway by landscape architects, designers, builders, suppliers, clients, students, and more to address the challenges of a changing climate in ways that mitigate environmental impacts, improve health, and offer joy -- at every scale.

We are actors with agency in this crisis. The landscape is a continuous system of which we are all members and stewards and participators and designers. Designing the outdoor spaces of our homes, our neighborhoods, and our region to help humans and the environment adapt to climate change with health and beauty is the grand project of our lifetimes – the grand project of landscape architecture.

We hope that you’ll be challenged and inspired by this Fieldbook. We hope that you’ll find reflection, invigoration, a sense of shared mission, and optimism. Roll up your sleeves. It’s not hopeless. Landscape architects are the only ones who design with living things and living systems. And don’t take for granted how beautiful our planet is daily.

Thanks for joining us in these conversations and in our collective work ahead.

Scott Bishop, ASLA

Jason Hellundrung, ASLA

Liz Luc Clowes, ASLA

Jessica Montgomery, Student Affil. ASLA

Fieldbook CLIMATE Guest Editors

5 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS / BSLA

Jason

Liz

A conversation with Andrea Barella, Sam Coplon, FASLA, Tom Hand, ASLA, Deborah Myers, ASLA, Michael Radner, ASLA, and Bernice Wahler, ASLA 30

Scott Bishop, ASLA in conversation with Pamela Conrad, ASLA, and Christopher Ng-Hardy, ASLA

Rob

Jamie Hark,

Pallavi

Liwei

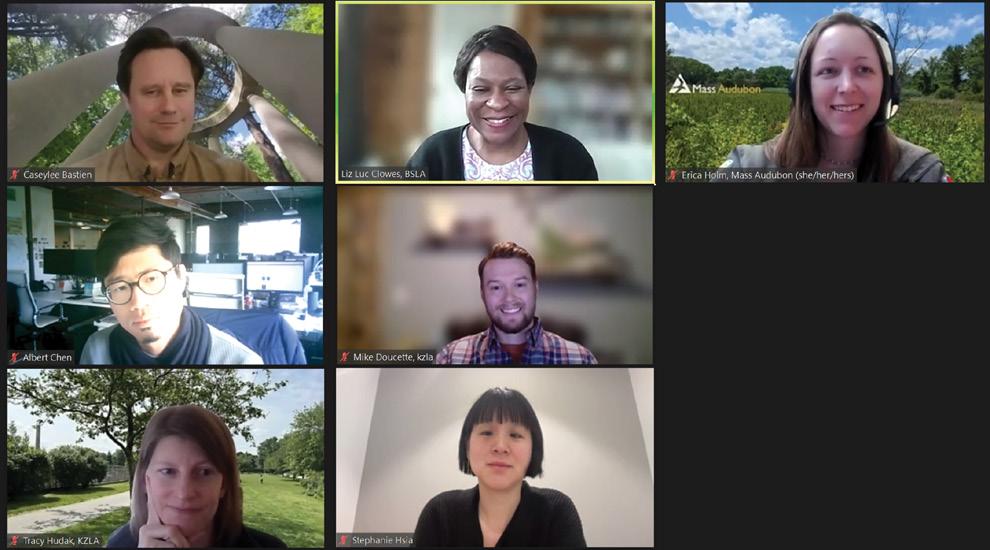

Liz Luc Clowes, ASLA in conversation with Casey-Lee Bastien, Albert Chen, ASLA, Mike Doucette, Erica Holm, ASLA, Stephanie Hsia, ASLA, and Tracy Hudak

Michael

Julia

Jason Hellendrung, ASLA in conversation with Marin Braco, ASLA, Hillary King, Troy Moon, Julie Wormser, and Alysoun Wright

Paths of Entry Conversations 1 ON THE COVER 2 PARTNER SPONSORS 3 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Luisa Oliveira, ASLA 4 LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Bishop, ASLA

CLIMATE

Scott

Hellundrung, ASLA

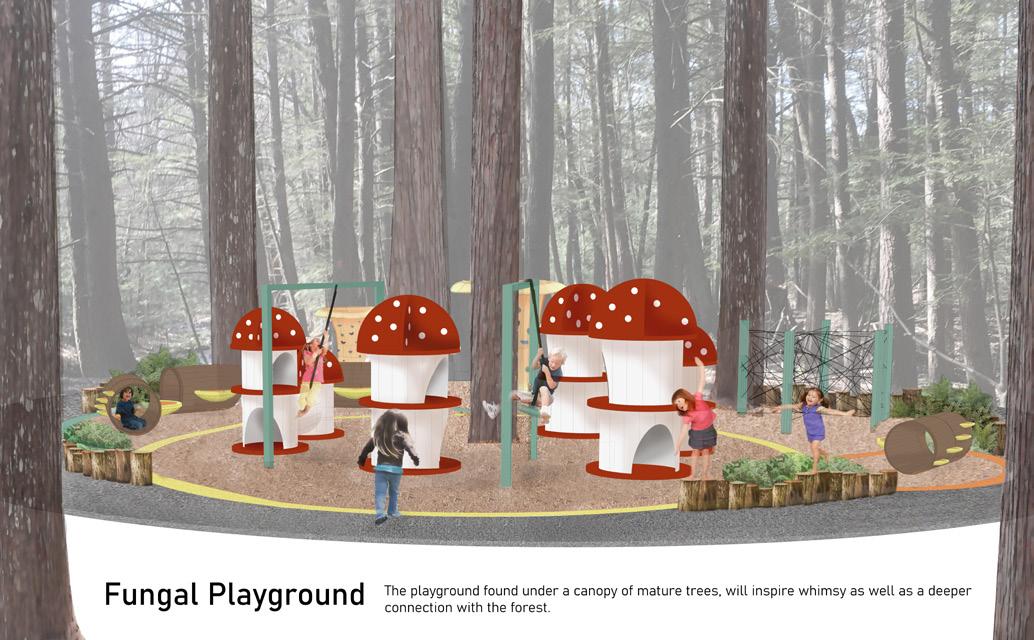

Luc Clowes, ASLA + Jessica Montgomery, Student Affil. ASLA 10 WORK + PLAY

Barella, ASLA

Assoc. ASLA

Mande

Shen, Assoc. ASLA 16 SMALL SITES + BIG IMPACT

Ng, ASLA 26 AN APOCATOPIAN PRIMER Kira Bre Clingen 35 FROM ENVIRONMENTAL TO EMOTIONAL RESILIENCY Emily Scarfe 42 SUSTAINING THE SHORE

Jennifer

Amato

Slater Voices 18 CHANGING PRACTICE

TOOLS +

TACTICS

ON THE FOREST

36 BRING

44 SCALING UP, ACROSS, & BEYOND

6 BSLA

On this page: Plants and trees help cool our communities! Here, a high school student uses an infrared thermometer to measure temperature differences between street trees (at top), the roadway, asphalt, and cars (middle), and the plants of the “Park(ing) Day” installation (bottom). Plants are substantially cooler.

Park(ing) Day is an annual, global festival in which parking spaces are temporily transformed into mini parks. BSLA creates Park(ing) Day parks in collaboration with schools -- in Portland, in Western Mass, and here -- with Boston Green Academy.

more about landscape architecture’s

and commitment to climate action. Check

the

7 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

impact

out

ASLA Climate Action Plan 54 2022 DESIGN AWARDS 56 Student 64 Communications 68 Analysis & Planning 80 Residential Design 96 General Design 130 Special Recognition 134 Landmark Award 137 2023 DESIGN AWARDS 138 Student 148 Research 150 Analysis & Planning 162 Residential Design 170 General Design 186 Special Recognition The

50 CIRCLE OF SUPPORT 52 ON A LIGHTER NOTE COMIC RELIEF Joe James, ASLA 190 DIRECTORY OF ADVERTISERS www.asla.org/climateaction TABLE OF CONTENTS / BSLA

Learn

Chapter Design Awards

8 BSLA

MASSACHUSETTS | CONNECTICUT | RHODE ISLAND landscapecreationsri.com | 401.789.7101 LET’S BUILD SOMETHING EXTRAORDINARY Our full-service landscape construction team has decades of experience bringing exceptional design to life across every aspect of the outdoors. Gregory Lombardi Landscape Design | Neil Landino Photography 9 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

WORK + PLAY

ROB BARELLA, ASLA

Climate change can be overwhelming. Yet landscape architects are professional optimists, trained to envision a better future. What’s one thing that you’re optimistic about?

Lives in landscape architecture

I am by no means a professional optimist. Admittedly, it is easy to feel overwhelmed when thinking about climate change. The book, All We Can Save, is a good place to look for inspiration. I also find it helpful to visit parks -- especially projects recently completed -- and people watch. Seeing people enjoy these places reassures me that it is worth caring about these landscapes, and I am optimistic that the public cares about the health, quality, and longevity of their outdoor spaces.

What do you think are the most pressing challenges in design for climate change?

Representing different ages, geographies, and practices, practitioners from across the region were asked to respond, in their own words and from their own personal perspectives, to intentionally open-ended inquiries about topics both serious and silly, offering glimpses into the life of a landscape architect.

Cost and maintenance are obvious challenges. We shouldn’t have to accept losing green infrastructure features during the value engineering process, and designed landscapes can only be successful if they are properly maintained. The third challenge I would include is the image of the idealized suburban landscape, both commercial and residential: the manicured lawn, paved driveways, the alien ornamental plants that don’t provide much for biodiversity, red mulch, and more. While the third challenge may seem inconsequential, it’s a huge population that could make changes in their own backyard that would collectively work towards mitigating the impacts of climate change on a larger scale. We need to change the perception of what these landscapes “should” look like, and better communicate what the landscapes want to be.

Is there a climate-related project that you’re working on now that you’re excited about?

We are currently working on Codman Square Park with Boston Parks. The design for this passive park has evolved into a great educational resource and testing ground for various forms of green infrastructure: replacing impervious surfaces with pervious pavement, creating rain gardens, and adding a bottle filling station and misting poles to help mitigate urban heat.

What books have you read recently? Books not about landscape architecture?

Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World by Mark Kurlansky was fantastic. If you live near the New England coast, are interested in learning about the impacts of overfishing, or have ever eaten bacalhau, then you should read this book. You’ll gain a wealth of cod knowledge in time for your next dinner party.

10 BSLA

JAMIE HARK, Assoc. ASLA

What’s a hidden superpower of landscape architecture that you’d like more people to know about?

I’ve always felt that landscape architects are time travelers. In any given day I’m researching 300-million-year-old rock, acknowledging rich Indigenous histories on the land, designing for exponential sea level rise in the coming centuries, and advising when clients should cut-back their ornamental grasses next year. It’s a wild ride, and there isn’t a job quite like it.

Is there a climate-related project that you’re working on now that you’re excited about?

Our office is thinking a lot about how the work we do relates to the bigger picture of addressing climate change in Maine. I’m working on a cool brownfield- project near Portland with seams of living shoreline woven into an otherwise armored coast. It’s the stuff you see in magazines and big cities but now it’s supporting smaller communities in Maine.

On the other side of the spectrum, we’re looking at how coastal residents can feasibly protect their assets with soft techniques – thoughtful plantings, subtle earthwork, wave attenuation. Here in Midcoast it’s not just McMansions on the water, but modest multi-generational homes, farms, and working waterfronts. We’re doing some pro-bono work with a sheep farm, giving the clients a plan for what they can do with their own two hands as their shoreline changes. I love this stuff.

What does a day in your life look like? How do you strive for work-life balance?

I get to wake up every morning in the woods on a peninsula in Casco Bay, so my day looks pretty good. I work as hard as I can but carve a lot of time out for what matters most. For me that’s time with my family, getting outside and giving back to the community. Big plug for getting more young landscape architects on conservation commissions, non-profit boards and in local politics in your towns. You can’t help your communities when you’re overworked at your day job!

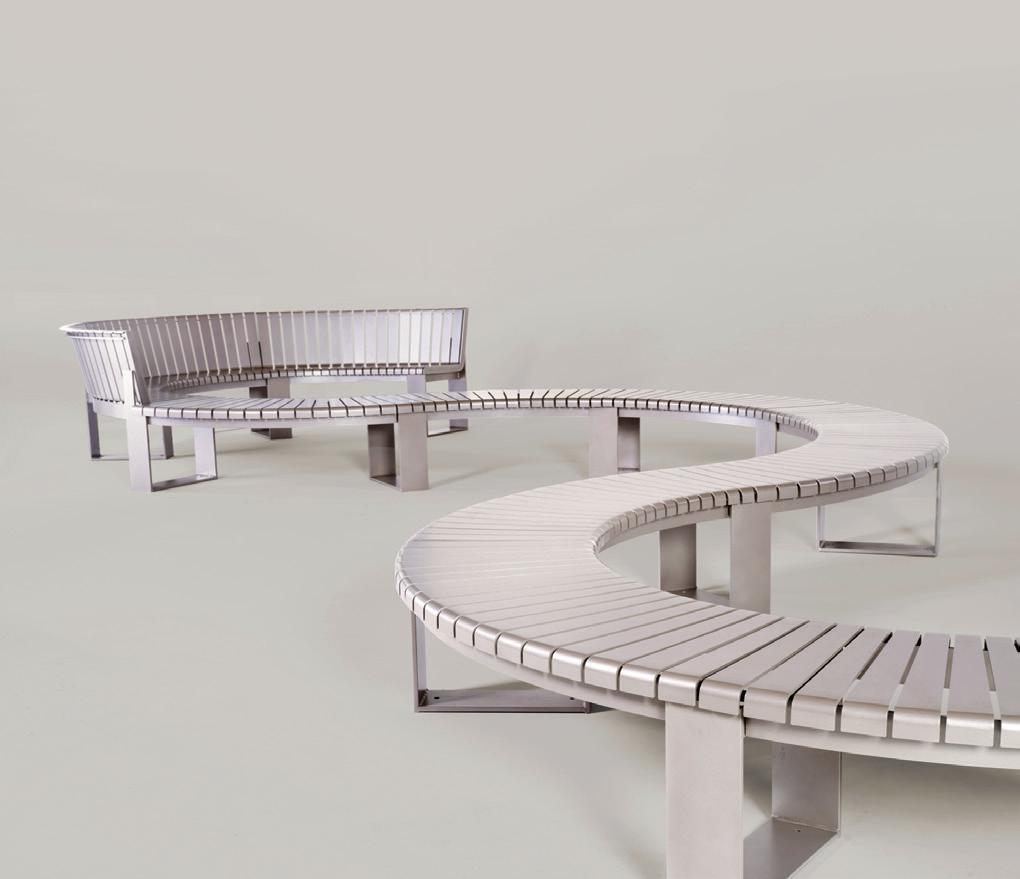

What’s one thing that you’re optimistic about?

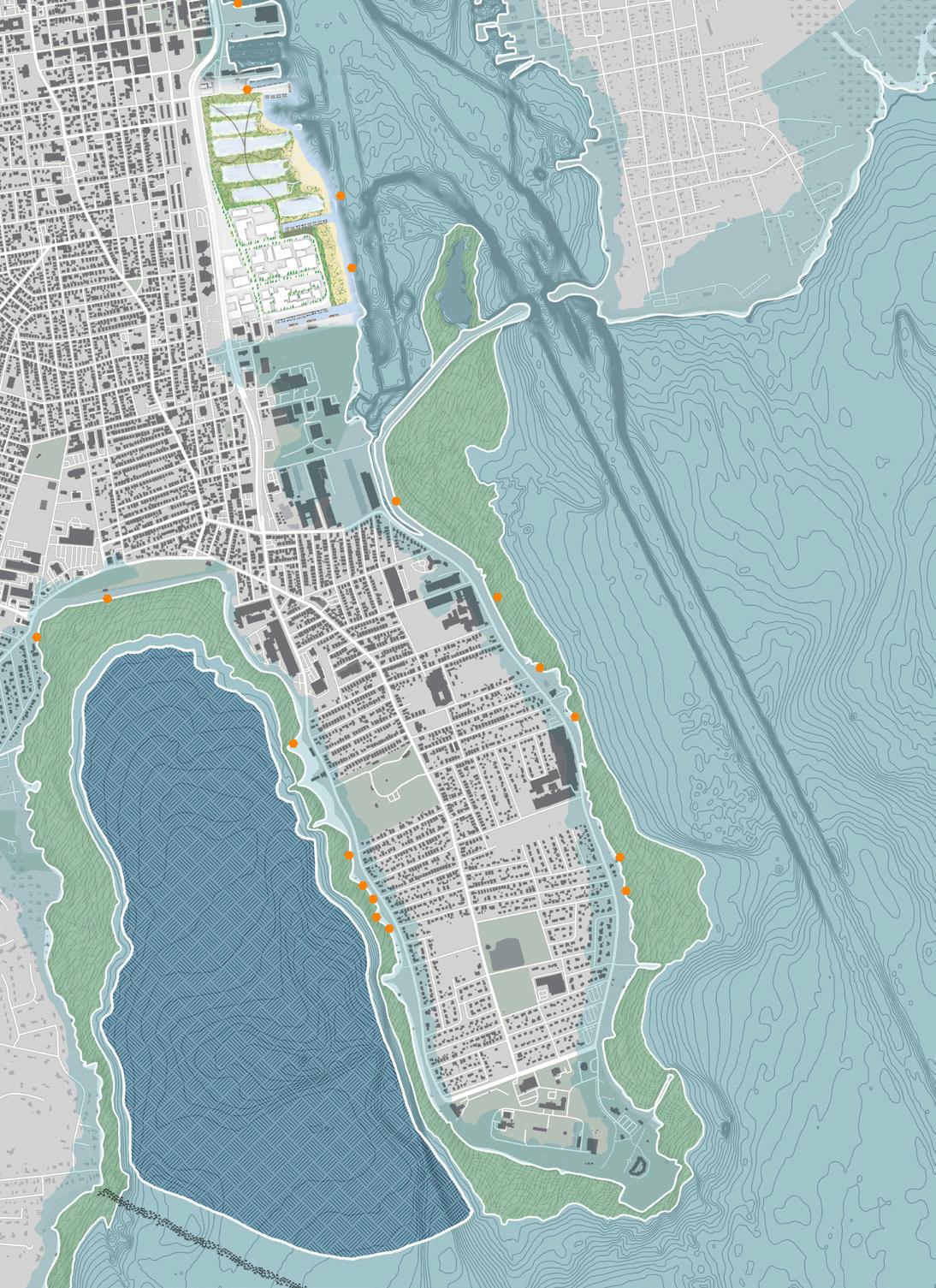

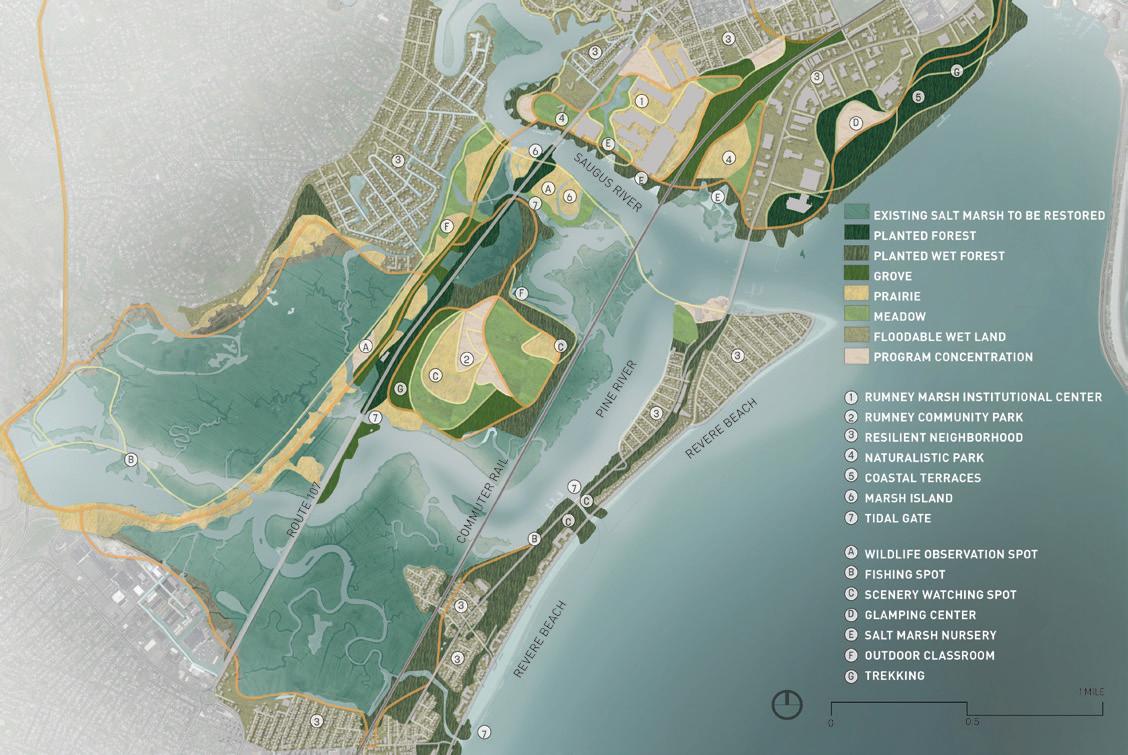

I’m excited for a fundamental shift in how we think about coasts. Until now, the coast – whether on an ocean, river, or lake – has been thought of as a solid line with great views. With rising seas and erosive flood events, we are forced to think of the coast as a threshold, where heavy development just won’t work. As landscape architects this gives us an amazing opportunity to redesign and reorganize our coasts, prioritizing adaptation, biodiversity, and community use. To be clear, we’re headed towards a bleak future, but landscape architects are going to be integral in the days ahead.

PALLAVI MANDE

How is climate change changing your work?

As an architect, the interface between water, landscape, and cities has always inspired me. Looking back at my journey over the past two and a half decades, I can trace a common theme of striving to understand the relationship between nature and our built environment that has created and sustained our habitat over time. A relentless desire to enhance and restore this interface has shaped my career as an urban designer, water practitioner, and advocate for climate justice. My design practice in the Boston area has been heavily grounded in an understanding of watershed science and engineering. As I increasingly worked with environmental justice neighborhoods, I found myself becoming an advocate for climate resilience.

Restoring the ecological health of our land and water resources is critical to improving the quality of life of our most vulnerable communities.

Is there a climate-related project that you’re working on now that you’re excited about?

I am currently working on several, but one that I’m especially proud of is the Climate Resiliency Master Plan for Stow Acres located in Stow, Massachusetts. In addition to a wonderful client (Town of Stow), I love that I have an extremely talented team of ecologists, wetland specialists, landscape architects, soil scientists, invasive species managers, and environmental planners collaborating on ecological restoration and climate resilient design solutions.

What do you think are the most pressing challenges in design for climate change?

There is a direct correlation between the impervious cover in our cities and the quality of our natural water resources. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is only one part of the equation. We need to focus on replicating the natural water cycle in urban areas and restoring the predevelopment hydrology in our cities. Despite progress in “accommodating” climate change adaptation strategies in standard urban design and planning toolkits, we are still not fully integrating the natural water cycle into the way we think about creating resilient infrastructure.

What’s one thing that you’re optimistic about?

I am optimistic about the paradigm shift across sectors. I am especially proud of the leadership that state agencies and local municipalities have shown by investing in adaptation and resilience efforts across the region. Implementing naturebased solutions and using a watershed-based approach for environmental restoration has finally gained momentum.

PATHS OF ENTRY / BSLA 11 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

LIWEI SHEN, Assoc. ASLA

Is there a climate-related project that you’re working on now that you’re excited about?

I’m currently exploring a project about landscapes of weather. It seeks to understand how people perceive weather, utilize rain, appreciate the sky, and adapt their lifestyles and interactions in response to changing weather patterns. I found some interesting traditions during the ethnographic review. For example, rain-praying landscapes have served as community centers in North China’s agricultural societies for centuries. These sites, often centered around a temple, play a crucial role in upholding Confucian social norms.

Climate change can be overwhelming. Yet landscape architects are professional optimists trained to envision a better future. What’s one thing that you’re optimistic about?

I am optimistic about creating new aesthetics for nature appreciation. Climate change introduces us to new experiences with temperature, humidity, and weather events in the coming times, and landscape design is about designing the new spatial experiences shared by all within that. It is intriguing to think about future landscape spatial patterns: what can be inherited, what can be broken down, and what can be reconstructed.

What is your favorite landscape, anywhere?

I like the ancient dwellings in Mesa Verde National Park. I appreciate how the original inhabitants ingeniously utilized the natural fissures in the rock, leveraging local materials and the unique topography to construct delicate castles nestled within the cliffs. It represents a primitive, humble, and elegant way of living and responds gracefully to natural conditions.

What books have you read recently? Books not about landscape architecture?

I read The Tale of Genji. It is a long, beautiful, peaceful, and sometimes sad, ancient Japanese novel that spans four generations of emperors during the Heian period. It weaves together the landscape’s seasonal changes, the atmosphere, and the characters’ emotions and life stages. I found it delicate and rare. I also read The U.S. Supreme Court: A Very Short Introduction by Linda Greenhouse. It’s an incredibly useful book for me to understand the evolution of mainstream legal and public opinions.

What is your favorite thing to do when you aren’t at work?

I like riding my unicycle. I learned this in my childhood, and it reminds me of my family and past friends. I spend a lot of time drawing on my iPad, too.

We get to tell stories and make the world a more beautiful place, while being paid to adapt to climate change, educate communities and improve biodiversity. What could be better than that?

Jamie Hark

Rob Barella is an Associate at Kyle Zick Landscape Architecture. He received his BLA degree from the University of Rhode Island. Rob has a strong interest in placemaking and tactical urbanism and has created several pop-up installations in the Boston area.

Jamie Hark is a Landscape Designer at Viewshed in Yarmouth, Maine. He received his Masters of Landscape Architecture from the University of Virginia. He works with communities and ecologies across Maine, designing and planning on the front lines of climate change.

Pallavi Kalia Mande is the Director of Climate Resilient Design at BSC Group. Pallavi’s planning and design practice is heavily grounded in an understanding of watershed science and engineering. With over 20 years of experience in environmental planning and green infrastructure design, she brings expertise in developing nature- and community-based solutions for climate resilience.

Liwei Shen is a Landscape Designer at Sasaki and received a Master of Landscape Architecture degree from Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2022. She likes her work because it makes the physical world more beautiful. Recently, she has enjoyed watching Seinfeld while cooking, eating, and working out.

12 BSLA

WWW.AURORALIGHT.COM WWW.BIGCONNECT.COM - INFO@BIGCONNECT.COM - 508.653.2144 13 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

Landscape Construction | Masonry | Maintenance R.P. MARZILLI & CO., INC. | (508) 533.8700

RPMARZILLI.COM 14 BSLA

Gregory Lombardi Design | Neil Landino Photography

ECOLOGICAL LAND CARE | EDIBLE GARDENS | MEADOWS Bring Sustainability Home botanicalandcare.com A division of R. P. Marzilli & Company 15 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

“Change happens at the site scale.”

Jennifer Ng, ASLA, is a Senior Associate at Klopfer Martin Design Group with a passion for community-driven design. The consistent theme in her projects is to create a sense of home. Stewardship of the environment and culture is an everyday, every project opportunity.

16 BSLA

©Christian Phillips Photography

JENNIFER NG, ASLA

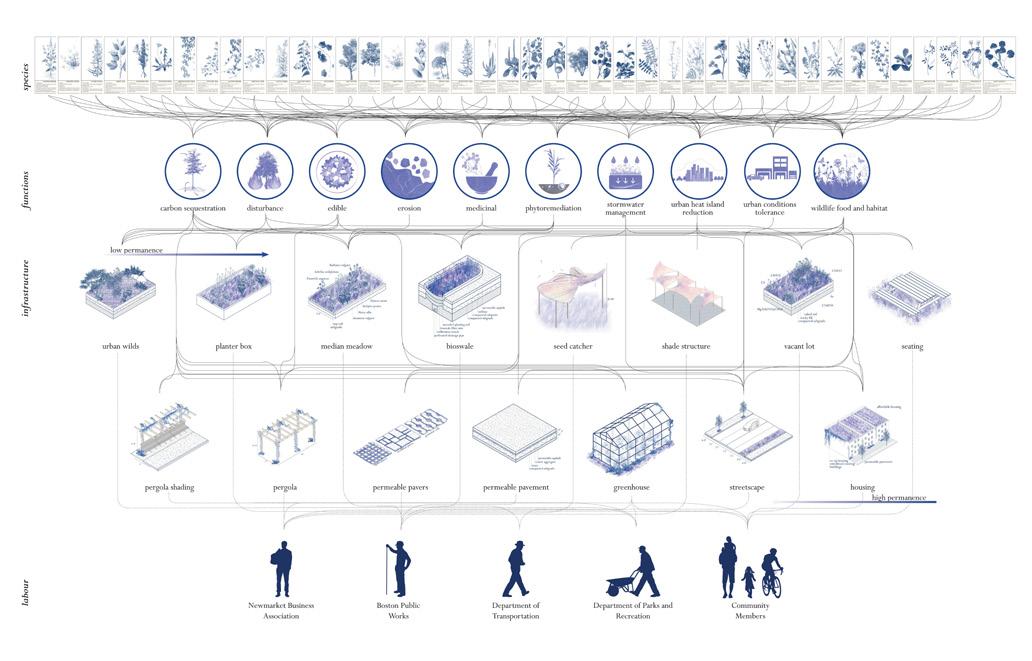

Small Sites + Big Impact Building a Network of Climate Action

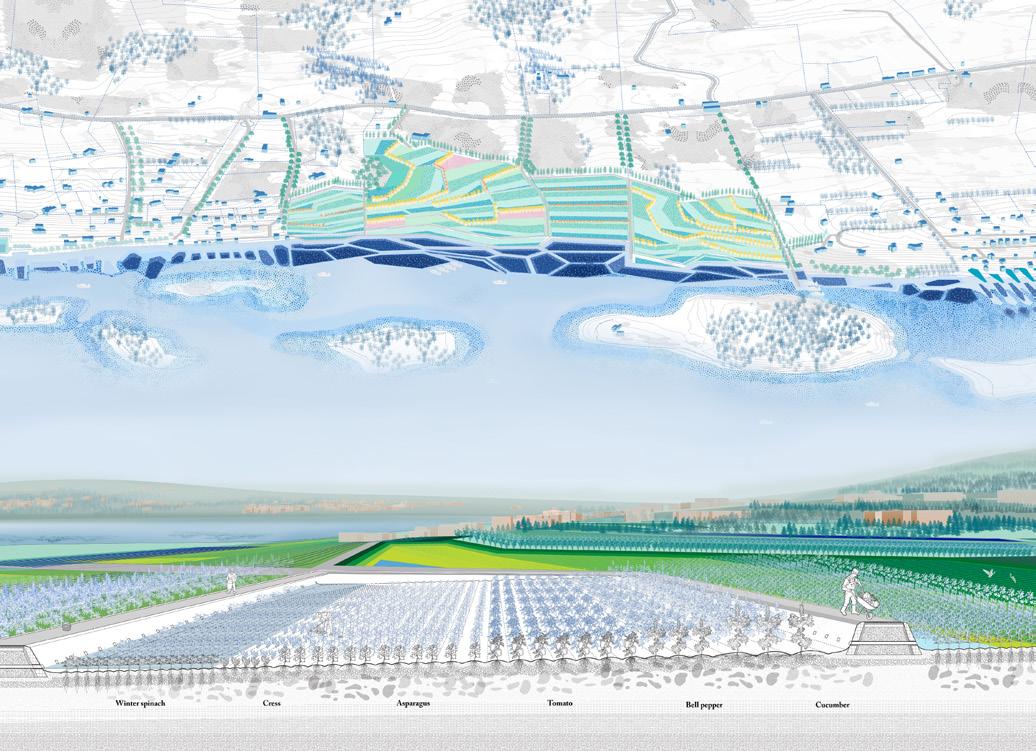

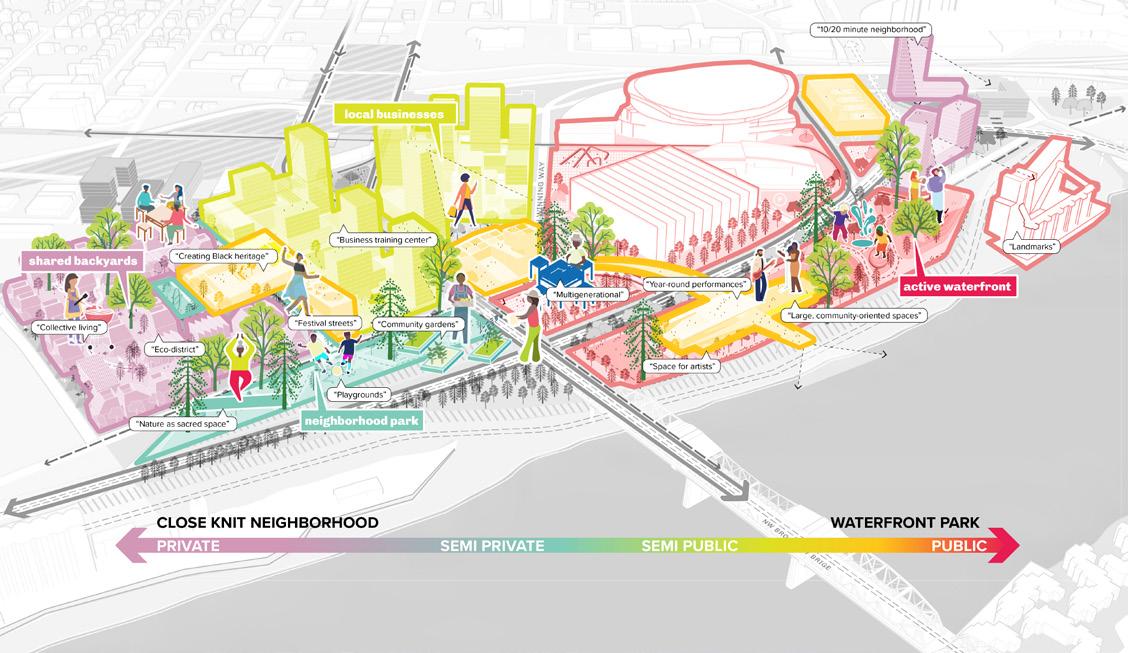

With the focus on climate change and the role landscape architects can have in resiliency planning, there has been a galvanizing energy on large-scale resiliency plans that span the neighborhood, district, and city-scale. Small sites are largely untracked and under-represented in the climate change conversation. But change happens at the site-scale: incremental changes that collectively have a big and measurable impact.

Issues such as urban heat island, carbon footprint, stormwater management, watershed management, and biodiversity are all addressed at the site. The spider web of our projects is vast.

Small sites also help with resiliency fluency. A big challenge is getting buy-in from clients who may not always prioritize resilience. These clients span all project types: government

agencies that have interest but maybe don’t have the tools for long-term maintenance or need help coordinating across agencies; developers who are interested in the story but need to hit a bottom line; and residential homeowners who don’t see the contribution their home can have for the greater system. Building a personal connection to the issues and to the solutions starts locally: our schools, our favorite street, our favorite outdoor space, our home.

Resiliency must start with the site scale and can be achieved regardless of our seat at the table. We all have a part to play in our shared resilient future. Small steps lead to big impact. The transformation can be empowering and breathtaking.

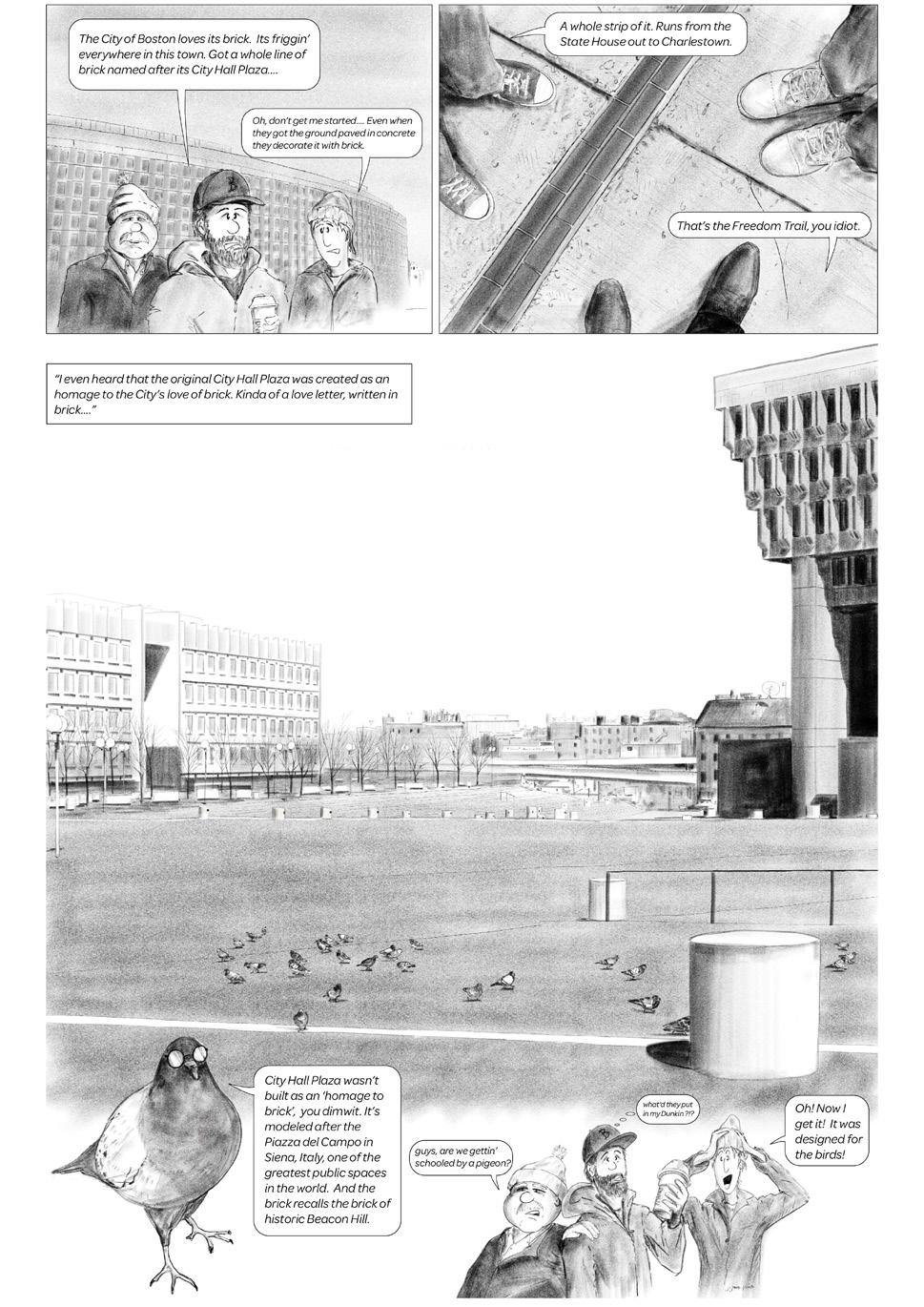

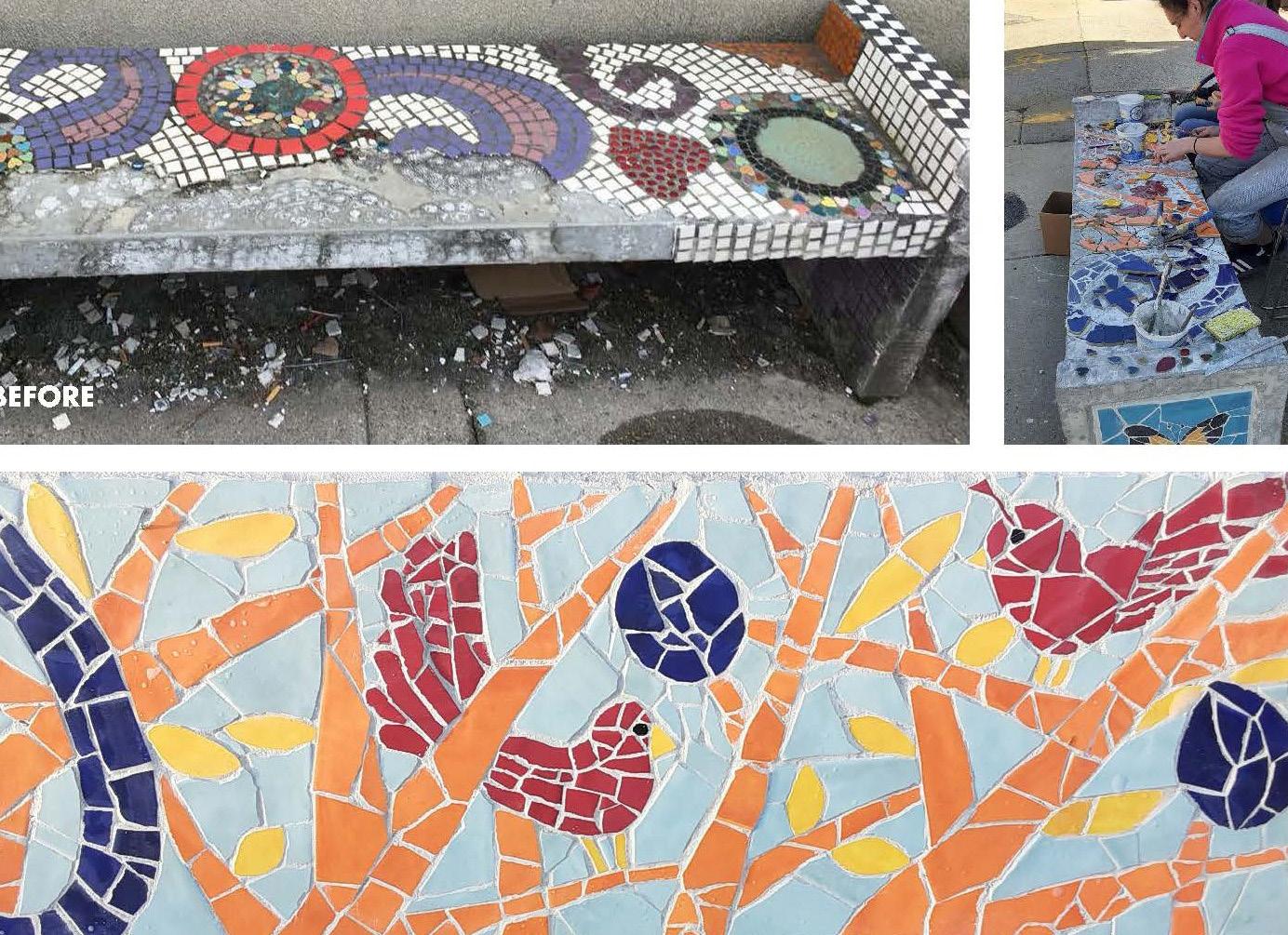

At Central Square in East Boston, a 19th century Olmsted Brothers’ design included an elliptical, fenced park within a commercial square. Over the 100+ years since, it had become an inaccessible traffic island surrounded by vast pavement. In 2010, the Boston Transportation Department called for a redesign of the vehicular mess, which ultimately became a public space renovation too.

Public space was expanded, lanes for vehicles redefined. The original ellipse was reinterpreted as a low granite seat wall supporting informal play and gathering. The historic tree canopy was restored and 97 trees added to address urban heat. The project became a City of Boston pilot site to test urban rain gardens and stormwater infiltration -- green and blue infrastructure. 95,000 gallons of stormwater are now stored here, minimizing overflow to Boston Harbor, and similar strategies are now used on other small sites throughout the city. Perhaps most importantly, it is a safe, vibrant neighborhood space with yearlong activity.

After 17 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

Before

A conversation with ANDREA BARELLA , SAM COPLON, FASLA

TOM HAND, ASLA

DEBORAH MYERS, ASLA

MICHAEL RADNER, ASLA, and BERNICE WAHLER, ASLA

Changing Practice

Landscape Architects from across New England discuss how climate change is changing the work that they do

Changing perceptions of “ideal”?

Here, a homeowner converted lawn into meadow, and hired landscape architect Andrea Barella to provide a more designed aesthetic because the town thought the property was abandoned. This new lawn reduces water and chemical use and improves biodiversity.

18 BSLA

Welcome.

Mike: Hello. I lead Radner Design Associates, a two-person firm based in Dedham, Massachusetts. I’ve been practicing since I graduated in 1990, starting my firm in 2001. I focus on small to midsize commercial work, with occasional public and residential projects.

Deb: Hi. I’ve worked in the Boston area for 28 years (including with Mike, early on). Nine years ago, I started DMLA. We’re a four-person landscape architecture practice focusing on multifamily housing, affordable housing, parks, open space, and the rare occasional single-family home.

Andrea: I recently started working at Kenton Frost Landscape Architecture in Mystic, Connecticut, but I have been in Boston for the past eight years. I’m working on public parks, institutional, and commercial work now. Previously, I had been doing more residential.

Bernice: I have a small practice on Cape Cod in Sandwich, Massachusetts— just across the Sagamore Bridge. I’ve practiced on the Cape for 15 years under my own name and have been in the Boston area since 2001. I have an office of four designers, plus myself. We primarily work on high-end residential because that’s the work that surrounds us, with a few institutional projects.

Sam: I live in Mount Desert, Maine, and am in the next phase of my career. I had an office in Bar Harbor, across the island. I have no employees now; I have collaborators. Our practice has primarily focused on projects with discernible public benefit. We did a lot of public work, a lot of institutional work, a lot of work for nonprofits and conservation groups. I’ve been here since 1987.

Bernice: That’s a good long time to be up in Maine.

Sam: But I’m still not a native.

Bernice: <Laugh>. No, we never are. I’m not a native of Cape Cod, either.

Tom: I’m definitely still a flatlander up here in Vermont. Like others, I had my early training in the Boston area. I’ve been in the resort design space, recreation, and outdoor planning. I recently opened my own firm, SiteForm Studio, in Stowe. It’s a fun town to be in because there are a lot of people coming through and a lot of visitors. I started my own practice to get more into residential.

On the changing climate

Sam: It’s an appropriate day to discuss this because it’s February 28th, 46 degrees, and it’s raining. Crazy.

Mike: Yesterday I was outside without a jacket. It was 60.

Bernice: And then it will freeze again. Plants that are zoned to survive here are having a hard time. We’re supposed to educate our clients, but we’re all learning together. I have a rhododendron that’s blooming in the fall because it was such a crappy summer, and then it got warmer and rained. All kinds of funny things happening with the swings in the weather. That is changing how we think about things and has created an unsettled, less-studied road.

Sam: We’ve been working for Acadia National Park for the last 25 years and

Terrace at Orient Heights was the renovation of 300+ units of mixed income housing. Throughout the 45 foot grade change, concrete and asphalt were replaced with planted open spaces for gathering and play. 69 new plant species were added, enhancing biodiversity and improving shade in this heat island neighborhood. DMLA

Before After 19 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

Overlook

have done many projects there, many of which involve planting. One requirement is that you can only install plants that are native to Acadia—a pretty small palette. We’re installing plant material now that may be supplanted or not appropriate for the lifespan of that material.

Bernice: What is the changing definition of natives? It is changing in front of our eyes. One thing that landscape architects could lean into is creating more mobility in the definition of natives.

Our regulations here on the Cape are pretty stagnant, much like in many other areas. We’re restricted to a specific list of approved plants for planting. As a Town of Sandwich conservation board member, we’ve seen instances where these approved plants didn’t thrive as expected. The regulations don’t allow planting non-native species, even if they might be more suitable alternatives.

Andrea: Has Acadia been receptive to you planting more shifting zones? How can we educate? There are such strict requirements for natives, but the climate is changing. I’ve noticed the same thing.

Sam: Typically, no. So, I try to find plants that are native here but have a broad range and are viable in the southern reaches of the zone. Acadia is an excellent example because it’s regulated. What makes it more challenging is maintenance.

Deb: What I’m finding in Boston and the Eastern Massachusetts region, and certainly with the re-publication of the hardiness zones, is that we’re encouraged to “plant-forward” for 20 years from now and warmer weather. Hopefully, other cities and towns will follow suit. As we all know, plants cannot adjust on their own in time in terms of succession of plant communities. The conservation commissions are quite knowledgeable. I’m on the board in Brookline, and it’s even in the code.

Tom: The cities may be well-established and understand the issues. But it’s not very much on the radar where I’m working now, in smaller towns. Part of my practice is to bring that more into the conversation. However, it’s still very common for someone to say, “I want to do this because of the environment,” but what they suggest is antithetical to the environment.

Mike: I find that interesting, Tom. I’m seeing a wider recognition and acceptance of climate-forward solutions. I’ve seen the attitudes of our clients change over the long term. They seem to be getting younger as I age, <laugh>, but now, when I talk about climate change, I don’t get a blank stare anymore.

I have real estate developer clients who are totally on board, and it’s not just the plantings; it’s landscape as

The Long Pasture Discovery Center, Mass Audubon, Barnstable. A formerly ornamental garden is transformed into a landscape with native plants and natural materials. New grading, seat walls, and paths provide spaces for learning and recreation and ensure that everyone can use this community amenity. Bernice Wahler Landscapes.

green infrastructure, landscape as infrastructure. And the homeowners are aware of it as we do residential work. Clients are one of the drivers of how we change our design approach. Everybody is much more accepting of it.

The other drivers I see are the approval boards and codes. It’s not just conservation commissions; people serving on planning boards are much more sophisticated in their approach to green infrastructure and pushing this agenda of native plantings. I don’t have to explain what a rain garden is anymore. It’s not only us pushing from the design and professional end of it. The media is constantly talking about this. Tom, I’m surprised; with all of the stormwater damage in Vermont, how we plan should be at the forefront of everybody’s mind.

Tom: Stowe has a huge population of second homeowners, and I have a lot of people who come in and want to spend a lot on their architecture and a sustainable structure but then do not put much thought or budget into a sustainable landscape. There are lots of cleared forests and new lawns.

Andrea: I agree. Clients like sustainable solutions, but maintenance or perception can be an issue. Sometimes, there is pushback regarding how we’ve always perceived the residential landscape. I worked with a client who grew out their

Sanborn Road Garden, Stowe, Vermont. A two-tiered terrace is separated by a linear raingarden that captures and treats stormwater from the roof. A bridge crosses the garden and steps down to the lower fire-pit terrace. A linear stone wall separating the two spaces and acts as a natural seatwall. SiteForm Studio.

20 BSLA

lawn, and they had neighbors come and petition them to clean up their yard. This city had regulations supporting pollinator landscapes, but people who went to the house thought the yard was abandoned. We were hired to beautify and formalize things.

The homeowner told me that what made it worth it was a girl who would stop by on her way to school. She said it was her favorite place, and she would take pictures of all the butterflies and pollinators she saw in the yard. There are shifting ways of getting other people to get on board with these practices, I guess.

Deb: A similar thing happened in multifamily housing that we did. I was there, and one of the grandmothers asked me if I was responsible for all these plants. And I said, yes, <laugh>. And she wondered, “Why all the bees?” So we created a signage campaign: “Why bees?” We tried to make it fun and educational. I wonder if an individual homeowner would also put up a sign, “This is not a mess. Look for the nesting bird, look for the… “ It’s education, and hopefully, those young kids who have the wonder and joy of seeing wildlife will be our future clients –or future landscape architects.

CONVERSATIONS /

directions. But if there’s no framework, it’s up to us to try to introduce these strategies into our designs. Meadows versus all-mown lawns seems to be a pretty popular one.

In Vermont, the state does regulate stormwater, but only at a certain scale. Many individual properties aren’t required to manage stormwater. Over time, these small nicks and cuts to the landscape have accumulated, leading to increased runoff. These smaller sites aren’t effectively absorbing or handling stormwater, contributing to excess

See more project examples in Design Awards and at www.bslafieldbook.org.

seen a generational sea change (not to make a pun). For a long time, civil engineers wanted to put everything in a pipe and drain it away. But now I’m seeing acceptance of soft solutions and landscape solutions.

While we’ve experienced heavy rains and floods before, we’re beginning to understand that the broader implications of unchecked development on individual properties are adding up.

Tom Hand

water flowing into valleys and rivers. While we’ve experienced heavy rains and floods before, we’re beginning to understand that the broader implications of unchecked development on individual properties are adding up.

Deb: I find that civil engineers can be my greatest advocates. They support us when we suggest a green solution, a porous pavement, or reduce pavements to make more efficient vehicular and pedestrian pathways through our sites. They ask, “How can we ensure that this can’t get value-engineered out? Let’s, let’s make it an engineering solution.” If they put it into their bucket, it doesn’t get touched. Generally, the architects and engineers we work with are on board and working on these issues, too.

Sam: Integrating “no mow” areas into landscapes that people frequent raises concerns about pests, ticks, and Lyme disease. Proper management involves keeping vegetation short. Don’t provide the habitat. But that’s a challenge if you want to minimize the amount of lawn. Minimizing mowing and putting in the right seed mixes becomes very important, and that quickly leads to a discussion of management and rightsizing the management for the use.

On adopting green instructure and landscape strategies

Tom: We’re facing two things here. From a regulatory perspective, there’s a clear obligation to adopt climate-positive strategies and embrace good design practices. There’s a prevailing public perception that we’re transitioning from old practices to new, more sustainable

I want lawmakers to recognize naturebased solutions and green infrastructure. In Vermont regulations, I still see a lot of reliance on typical belt and suspenders engineering and hard surfaces. For a long time, I think we’ve gotten away with humans encroaching on the native natural landscape, and now it’s coming back to bite us. Let’s work and adapt around river corridors and flood zones and not push our will on the natural areas.

That was my advice to a client recently who wanted to dry out their yard and get rid of a wetland. I pointed out that the wetland is there because it’s serving a function. We can still achieve the client’s goals, just not in that spot. She wasn’t very receptive to that idea.

Bernice: In residential, I find that it varies. If the green solution is more budget-friendly, clients will be more interested. Our job is to find that balance:

Mike: This brings up a good point about our collaborators. We work very closely with civil engineers, and I’ve

Penobscot River Trails, Grindstone, Maine. Development of 20 miles of Nordic skiing and recreational cycling and visitor services along the East Branch of the Penobscot River, and provides outdoor education and recreation for grades 4-12. Coplon Associates.

21 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

BSLA

to find the compelling reason for them to want to do it and a compelling reason that is also good for the environment. We get into that when we discuss coastal bank erosion. Many invasive plants cause erosion and a lack of habitat. And our clients, while they may not understand initially, we educate them on the benefits of a more native plant palate, and the perk to them is that their view is enhanced. We look for those sweet spots. I’ve never had a client come to me and say, “I want the most maintenance possible.” Every client asks for low maintenance. But then you lean into the native plant palettes because they can grow in more starved soil. It fits low maintenance goals and climate purposes. The trick of our work is finding that place where it makes everybody happy.

Sam: One of the challenges from a regulatory standpoint at the state level is that we have statewide environmental permitting for projects over a certain scale. Most of it deals with stormwater, but it’s not driven by site specifics. For instance, if you have fractured bedrock where you will have a lot of natural infiltration, that in situ information is not considered. The regulations are well intended, but often, they’re not landscape-driven and are not applied to the benefit of actual conditions.

Tom: In Vermont, we have an extensive stormwater manual, and every project ultimately just gets a gravel wetland. What about all of the other infrastructure benefits and opportunities with green infrastructure?

Sam: And if they are not doing it in Vermont or Maine…?

Tom: As landscape architects, could we have positive input into developing regulations that allow for more of a paintby-number approach to sites within the framework of a regulatory process, ultimately allowing for more site-specific needs?

Sam: Right. There are historic regulations that started at the dawn of time and keep getting amended. Is there a comprehensive look at effectiveness? We now have a lot of empirical data about how they perform and whether or not there’s a better way to do it.

On making change

Tom: We’re seeing success in municipalities like Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville because we have landscape architects as advocates making some of those policy decisions. There are other cities and towns where we need to get our act in gear and get to that level.

Andrea: How do you reach the smaller towns? How do you reach the towns that are doing it the way they’ve done for the past 50 years? Is it by us, as landscape architects, joining these boards and providing advocacy? Once you get out of the cities, there are often more traditional approaches, and that’s where the change needs to happen to reach a broader audience.

Mike: And a lot of these towns are underresourced.

Tom: In Vermont, many towns are grouped under our regional planning commissions. We’ve had conversations in our chapter about approaching the RPCs with these landscape-forward strategies, and hopefully, that can filter down to the towns.

Mike: I wish we had regional planning commissions in Massachusetts. Then, we could do watershed planning instead of town-by-town.

Bernice: I’m new to this place of figuring out how to make change. That’s what brought me to join a conservation board in the town that I live in. Through that, I’ve learned that many people are making these decisions on these boards, and not all are educated in anything remotely related to landscape architecture.

on a bigger understanding of those things. I’m over here trying to unbundle that onion and understand where information is coming from and how to make a good change.

On maintenance

Mike: What are others seeing as we specify more meadows, more native plantings, and more things that require a longer growing period? This also requires special expertise in on-site preparation, et cetera, et cetera. How are you dealing with landscape companies or contractors with varying levels of understanding and expertise in building and maintaining these things? Maintenance is the BIG thing that we’re starting to deal with a little bit more with our clients in the long-term, following up to ensure that things are growing properly in long-term maintenance and management plans.

Bernice: For us, technology is helpful. Apps that clients can use, like Picture This, where they take pictures of plants and then can see if it’s a weed or something that you’re trying to encourage. Part of the issue with meadows is that a bunch of stuff is growing everywhere. Sometimes, I don’t even know if that’s supposed to be there or not supposed to be there. Technology has been able to help in the maintenance

I’m still learning how to navigate this. It’s hard to understand how to create an actual code or regulation because it’s buried, and the system is not self-explanatory. Understanding how local jurisdictions work and operate has been eye-opening. Then, get to the next layer and the next layer. Tom, it’s great that you’re taking

Bridgewater State University. Four acres of asphalt paving were converted to a major green space that now offers pedestrian connections across campus. Underground stormwater pipes were daylighted to proved more capacity...

22 BSLA

and creation of a meadow. But not everyone has that in their pocket when doing the work.

The struggle is real with maintenance because it’s not valued. How do you expect an expert to come in and do that job when you don’t want to pay for that? Maintenance is always more than most clients want to take up. They want low maintenance. Again, education is essential. The price point of meadows is very favorable initially, for example. Still, we need to educate clients to factor in the need for that maintenance for at least three or four years before they get to anything sustainable.

I don’t have a great answer, but technology has helped.

Deb: Another thing I’ve been doing is that instead of my fee and services ending at construction administration, I’m trying to have a longer maintenance period where I’m still on contract, advising the team to take care of the landscape. That’s been super helpful.

you manage trees that will be down in 20 years. A book that clients can look through progressively over time that explains how we see the landscape evolving and how to keep it in tune with their goals.

On optimism

Bernice: We’re primarily residential and smaller-scale practitioners here. That does not reduce our positive effect on environmental change. A few of our lots together create the size of a park, and that impacts the same river system

See more project examples in Design Awards and at www.bslafieldbook.org.

realm.

Deb: We advertise climate resilience and seek clients who want to do that work. I’m super optimistic. I would encourage everyone to get involved in their local community, especially smaller communities without professional expertise or budgets. Grassroots is the next level for community awareness.

Climate resiliency is the core tenet of what landscape architects do. We’re the pointy end of the spear in that we are the ones bringing it to the fore, whether it’s a direct and celebrated approach or it’s quiet and subtle. Either way can be effective, and we are the leaders in this realm.

Sam Coplon

or salt marsh. We’ll have six projects in the same neighborhood, which will have a big influence overall. As you said, grassroots—tackling it on a small scale builds to the bigger picture.

Andrea: We’ve also created succession plans for future projects, such as how

...while native plantings enhance wildlife habitat while adding species diversity. Radner Design Associates + Nitsch

Opposite page: Before, and above, After

Andrea: I agree. Residential projects are such a big part of our practices. Little by little, you take on these properties; slowly, a wider audience of people see and experience positive changes. A trickle-down approach from one person to the next to the next. I’m optimistic. More people are talking about this, and more clients are receptive and open to making positive change.

Sam: Climate resiliency is the core tenet of what landscape architects do. We’re the pointy end of the spear in that we are the ones bringing it to the fore, whether it’s a direct and celebrated approach or it’s quiet and subtle. Either way can be effective, and we are the leaders in this

Tom: I’m hoping that climate alarmism is fading. I know that some people probably get energy from it. I’m not a big fan. I like the optimistic view. The themes of our conversation today: what can we do? How can we do a better job than we have in the past? And being aware of those practicing or regulating around us what’s working and what’s not. I’m motivated to get out into communities, advocate more, and be a loud drum for this. Thank you everyone.

Mike: I’ll close by saying that we’re talking about the land and the environment, and that’s great. We do all this for people. I’m optimistic that we’re doing the work that we need to do to bring a little more justice and equity to communities that have been ignored for many years. It’s the intersection of environment, social justice, equity, and climate; it all works together.

23 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook CONVERSATIONS / BSLA

® 24 BSLA

25 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

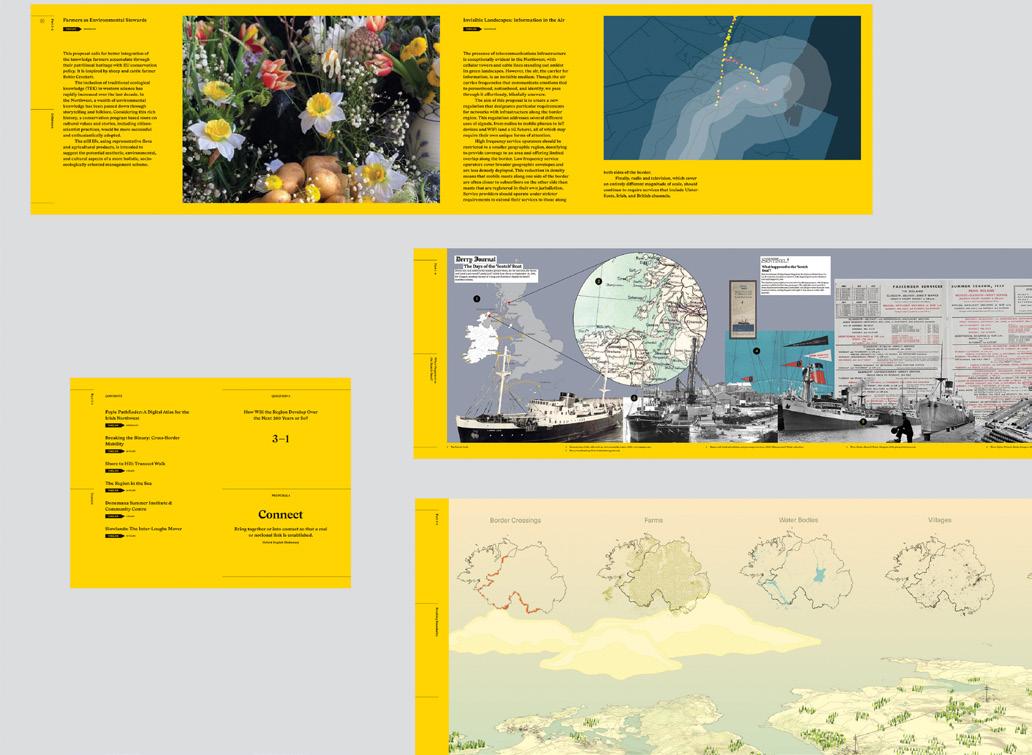

An Apocatopian Primer

A new bookshelf for landscape architecture + climate action

“In the face of ‘everything change,’ the design disciplines continue to bet that fragmented disciplinary histories will prepare designers to address global crises.

This is a losing bet.”

Kira Clingen is the Daniel Urban Kiley Fellow and Lecturer in Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and is a climate design researcher.

In the photo, a big mix of students and practitioners listen at a BSLA “Inside/Out” site tour of Triangle Park, Cambridge, fall 2023 -- another means to break out of silos and learn together in order to move beyond discourse to action.

KIRA BRE CLINGEN

26 BSLA

Science fiction author Margaret Atwood writes, “It’s not climate change - it’s everything change,” to describe our planetary crisis. Canadian wildfires turn our skies orange and keep us indoors with air quality warnings. Increasingly intense storms destroy the hard boundaries humans have erected between land and sea. City and town managers host intense discussions around concepts like managed retreat and technologies like heat pumps. People argue online and in person how much of recent heat waves can be attributed to climate change. Moving beyond discourse and debate to adapt to climate change is extremely difficult.

As designers, we are tasked with action. Our choices contribute heavily to carbon emissions pushing our planet further toward climate extremes that our society is unprepared for. Yet, for a crisis already here, the design disciplines are slow to respond. Zoning codes, permitting processes, and material supply chains are partly to blame, but so are egos, a pipeline to design that rarely includes designers from frontline communities, and silos between professions.

These silos are first introduced to future landscape architects in our educational institutions. The demands of accreditation require studios and syllabi to be framed around formal exploration, skill-building, software literacy, and preparing students for professional practice. Landscape architecture pedagogy, therefore, relies on a limited canon of readings and precedent projects specific to our practice. As Rosalea Monacella and Bridget Kane write in their volume, Designing Landscape Architectural Education: Studio Ecologies for Unpredictable Futures, design education is plagued by “a desire to limit ideological differences and knowledge [which] becomes the paradigm, rather than considering cross-pollination and cross-sections.” Architects study Le Corbusier and Rem Koolhaas. Landscape architects rehearse Frederick Law Olmsted’s projects and move on to the theory of landscape urbanism. Put another way: in the face of “everything change,” the design disciplines continue to bet that fragmented disciplinary histories and projects will prepare designers to address global crises. This is a losing bet.

As Billy Fleming writes in Monacella and Keane’s volume, “Before we ask the world to view design as an urgent necessity, we must look at those [discrete] sites, [incrementalist] tools, and [unjust] structures and remake our disciplines to be more useful, in the moment, for the movements and ideals we aspire to serve.” Intense specialization is not the answer. Designers must cast a wider net into different disciplines and discourses to supplement their learning, both in school and in practice.

An Apocatopian Primer

An Apocatopian Primer -- on the following two pages -- is a list of climate readings for the design disciplines. The list is an attempt to break out of our disciplinary silos and bring other, urgent perspectives on climate into design. The list’s title references British speculative fiction writer China Miéville’s essay, “The Limits of Utopia.” Miéville warns that utopias can be part of, and organized within, unjust societies and systems.

Miéville further writes, “rather than touting togetherness, we fight best by embracing our not-togetherness.” Jesse M. Keenan translates this idea to the design disciplines in his essay “Climate Core,” writing “The various professions of the built environment need translators just as much as they need specialists” to understand the shifting baseline of social and environmental values that design education does not address. Keenan notes the risk if “climate competencies are not developed in emergent professional classes, then the business-as-usual alternative” quickly emerges.

The question is: how do we build those competencies?

Some of the 52 (and growing!) titles in this Primer are produced within the design disciplines. Many are not. These books include works of fiction and non-fiction from around the globe that might inform acts of design. Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains by Kerri Arseneault, a place-based memoir on toxic dioxins released at a Maine paper mill. Oak Flat by Lauren Redniss is a graphic novel exploring support and opposition for a proposed open-pit copper mine on the land of the San Carlos Apache tribe. Understanding Disaster Insurance: New Tools for a More Resilient Future by Carolyn Kousky describes how insurance markets are being adjusted in the climate era. Bay Lexicon by Jane Wolff is a tour of San Francisco Bay that seeks to build landscape literacy for designers and interested readers alike.

These books describe the myriad ways our shared environment is already changing. An Apocatopian Primer challenges the idea that designers are somehow apolitical or removed from the systems and contexts in which we operate.

Instead of classifying titles by subject matter, genre, or discipline, the list uses characterizations based on the reader’s familiarity with the climate crisis:

• Tip of the Iceberg titles assume little to no background knowledge.

• Treading Water titles assume climate literacy and familiarity with the broad strokes of climate policy.

• The Deep End titles assume a broad conceptual understanding of the climate crisis as a slow-moving global catastrophe that will impact all facets of life on Earth.

Each book is further classified by the type of research, form of narrative, or action proposed in each book:

• Complicity and Denial titles focus on historical analysis of unjust systems and practices.

• Coming to Terms titles look at ways to understand the climate crisis, including philosophy and science reporting.

• Change-Making titles are books filled with ideas and speculative futures.

The Primer allows readers to choreograph new transects through climate knowledge as it provokes practitioners and educators to expand the ideological and disciplinary contradictions in landscape thinking while building climate literacy.

27 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

28 BSLA

29 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook See full bibliographic inforatmion at www.bslafieldbook.org.

SCOTT BISHOP, ASLA in conversation with PAMELA CONRAD, ASLA, and

CHRISTOPHER NG-HARDY, ASLA

Tools + Tactics

COUNTING CARBON IN THE LANDSCAPE

Scott: Last year, the theme of our Landscape Architecture & Climate Action in New England virtual summit was “Just count it.” This conversation is an extension of that. You have created fantastic and interesting tools to help us count carbon in landscape architecture projects.

Let’s start by acknowledging the emotional and sociological dimensions involved. I’m interested in what motivated you to develop these tools. Was it purely necessity, or did emotional responses play a role?

Pamela: I grew up on a farm in Missouri, instilling a deep connection to nature and sustainability from a young age. The ethos of “Take care of the land, and it takes care of you” was ingrained in me. About seven years ago, I noticed a glaring absence of discussions around the carbon footprint of our landscape architecture projects. Out of curiosity and frustration, I created the Pathfinder Tool and the Climate Positive Design challenge to address this gap in our sustainability toolkit.

With my connection to nature, I also feel a deep responsibility for its care. When

This transcript has been edited to fit in these pages. Read the full conversation at www.bslafieldbook.org

I began measuring the carbon impact of my projects, I was shocked by the extent of our emissions. It triggered an emotional response—I felt surprised, embarrassed, and even ashamed, given my belief that my work was environmentally friendly. Creating a tool to address this issue allowed me to take action and alleviate my climate anxiety. The more I can do, the more empowered I feel to combat the overwhelming challenges of climate change and the biodiversity crisis on our planet.

Chris: Raised in rural Michigan, I pursued environmental science and conservation biology in college. I was on a PhD track, but it felt like documenting the end of the world. I ultimately came to design because it seemed more optimistic, leading me to graduate school and eventually practice. We applied Pathfinder and Tally to projects in our office, and our findings mirrored Pamela’s: our projects fell short of expectations. Her tool facilitated these realizations, highlighting areas for improvement in both the structural systems of buildings and design choices.

We discovered radically different carbon outputs within similar projects and similar design intents. This oversight revealed our blind spot: while we excel at considering user experiences, sociological issues, design aesthetics, and client budgets, we lack an intuitive understanding of the climate impacts of our work. I realized that we needed to have a better sense early in the design phase when we could fundamentally change the framework of the project. This involves challenging clients on aspects like excessive parking and building footprints while advocating for ecosystem restoration and preservation. I hoped that if we had carbon data assigned to land uses early in the design process, we could start moving the needle. That’s what led to my research, which is distinct in that it has architectural data sets with landscape data sets at a much cruder resolution -- at a planning scale -- so that you can try to challenge the urban design framework of a project and start advocating for landscape systems early on.

Scott: Would you compare the two tools, and what might support one approach?

Chris: Our focus with the Carbon Conscience research white paper and its subsequent tool is to accurately inform planning and concept design. We intentionally use one square meter of resolution, making aggregated landuse assumptions based on typologies and compositions. This simplifies comparisons between large-scale land uses. As we progress beyond concept design, our workflow involves transitioning from carbon-consciousness in the sketch phase, where we play with overarching frameworks, to Pamela’s Pathfinder Tool, when detailed bills of quantities are available in technical design phases. For architecture, we recommend starting with the Epic Tool first and then Tally as a workflow.

Pamela: I’ll briefly mention that we’re preparing to launch a new version of Pathfinder in the fall. We’ve collaborated closely with Chris and his team to ensure a seamless transition for projects, particularly during the master planning

30 BSLA

or early concept stages. Chris’s extensive landscape-specific research will be integrated to enrich our knowledge base. We’re developing an application programming interface (API) to facilitate the direct transfer of quantities from Carbon Conscience into Pathfinder. We aim to streamline things and make it easier for users moving forward.

Chris: We’re also setting up a community where information can be shared between our tools. And between us and Epic, an architectural application. It’s all in the spirit of making it easier to do this work and having fidelity and consistency across datasets and models.

Pamela: Our primary task is merging datasets from Carbon Conscience and Pathfinder. Additionally, we’re working on a connection to the Building Transparency EC3 tool, an EPD (Environmental Product Declaration) database.

Many manufacturers have inquired about integrating EPDs into our tools as they develop them. EC3 is ready to act as a clearinghouse. Manufacturers are to provide their EPDs to EC3 for standard vetting. Once approved, EC3 will list them on their website, allowing a direct

link from Pathfinder. So, when you’re in Pathfinder, if there’s a product you are looking for but don’t see, you can directly search in the EC3 database and then pull that value into Pathfinder.

As EPDs become more prevalent, we recognize the need for a larger process. We’re also expanding into related metrics such as biodiversity, equity, heat, and water. We’re aligning with SITES and supportive of the guidance from Biohabitats. Acknowledging that this is one piece of the conversation, we broadly discuss holistic design for the climate and biodiversity crisis. We’re working towards expanding the tools to serve that purpose.

Scott: Would you discuss some surprises and challenges you’ve encountered? For example, discovering that a project may never achieve carbon payback. How do you approach discussions with clients in such cases?

Chris: After examining over 220 different landscape land uses and conducting takeoffs from numerous hardscape-oriented projects, I concluded that when considering all elements like lighting, infrastructure, drainage, civil engineering, and site preparation,

landscape architecture can be as carbon-intensive as architecture on a per-unit area basis. For instance, one square meter of a building typology can be equivalent to one square meter of an urban plaza. Maybe not every project will be carbon-positive, especially in highly urbanized areas. But every project can do better.

Many things that would improve performance clients don’t care about. Many things are hidden in technical data, such as using wax additives for asphalt or advocating for recycled materials in rebar that clients don’t pay attention to. There’s room for improvement on every project I touch or advocate for within my office; we can always do better. I also see an opportunity to advocate more effectively with municipalities, particularly in ambitious cities like Boston. We can emphasize the creation of high-quality landscapes that support dense, operationally efficient urban living, making cities desirable places to reside with the lowest possible carbon footprint.

Investing in sustainable urban landscapes is a worthy monetary investment and a valuable carbon investment. However,

31 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook CONVERSATIONS / BSLA

Clockwise from top left: Chris Hardy, Pamela Conrad, Scott Bishop

we can broaden our perspective by supporting larger-scale restoration projects such as salt marsh restoration and reforestation in the surrounding hinterlands. Viewing carbon as a resource, like water, allows us to invest in protecting and enhancing these landscapes outside the city. These efforts can significantly contribute to carbon sequestration and storage, buffering our urban metabolism and moving towards achieving whole-project net-zero goals. Cities, with their political agency, offer a unique opportunity for advocacy, which we should all consider advocating for.

Pamela: Understanding the concepts is critical. What are the strategies first? Then, start applying metrics and tools. I recommend exploring the Climate Positive Design toolkit, which we recently updated with contributions from Chris and others.

The ASLA Field Guide offers valuable resources, too. Chris has published the Carbon Conscience white paper. The strategies we’ve learned along the way are well documented, and we’ve done our best to share them.

do we get cement substitutions? How do we increase recycled content in steel and other high-emitting materials like plastics and synthetics? If we start from an order of magnitude perspective, many of those emissions are in our paved services and structures. Target those first. It’s great that we have trees and plants and landscapes that can sequester and store carbon, but the reality is that it takes time. That’s an unfortunate trade-off. First and foremost, we need to protect the resources that we have. Keep that carbon where it belongs and then really target those high-impact materials.

The good news is that there’s a wealth of natural materials for landscape architects to use, like stabilized crushed stone paving, gabions, rammed earth, cobble, straw, wattle walls, and compressed earth blocks. Repurposing materials from the

on the contractor and logged more rigorously, which may be coming as carbon accounting matures. However, we understand that a restored Spartina wetland, for instance, will outperform a lawn in terms of carbon impact. When making projections, we rely on the fidelity of available data, and by transparently stating our assumptions and methods, we can confidently offer recommendations to clients and communities.

Scott: Let’s talk more about materiality. As landscape architects, how do we think about materials differently, given that our materials are living?

As landscape architects, we have a responsibility to enhance the quality of life, which not only contributes to happier, healthier living but also helps preserve natural ecosystems and retain carbon where it belongs.

Pamela Conrad

Chris: There’s a lot of good work coming out. The ASLA Climate Action Committee is preparing a decarbonizing specification guideline to be released at the fall conference, which will be a good resource. Additionally, Meg Calkins is crafting a comprehensive book that delves deep into decarbonization, exploring landscape assemblies and detailing methods. However, there’s still much research to be done. While digging into the literature, I found huge gaps, particularly in our field. For academics seeking dissertation topics, addressing the need for decarbonizing landscape design presents a compelling opportunity.

Pamela: While I agree that more research is needed, it’s also essential that we don’t let perfection become the enemy of the good. It’s well documented that built environment emissions largely come from three materials: concrete, steel, and aluminum. Addressing these materials offers the most bang for the buck. How

site, like concrete and asphalt, can be crushed into base boulders. Meadows serve as substitutes for high-maintenance lawns. We know that lawns could be net sequesters, yet if they’re high maintenance, they could be net emitters. NASA estimated 49,000 square miles of lawns in the United States. The potential for transitioning lawns is enormous!

Other strategies include incorporating pine forests, green roofs, or cool roofs. While many of these strategies have been used for some time, we still must be thoughtful. For instance, when installing a green roof, it’s essential to consider emissions from lightweight foam and calculate to make sure that it serves your overall purposes. That’s the balance: know the strategy, measure it, and then gut-check and double-check that it won’t be worse off than you intended.

Chris: It’s important to recognize that the tools we develop for carbon accounting are projections, providing a means to compare datasets consistently. We may never have accurate carbon accounting in the built environment unless it’s put

Chris: There are two big differences between landscape and architecture in terms of materiality. First, we work extensively with living systems capable of sequestering carbon and providing various ecosystem services. Second, landscape architecture often specifies raw materials for custom fabrication, such as bulk aggregates and heavy stones, in contrast to architecture’s reliance on finished products assembled into structural systems. This fundamental difference affects how we account for carbon changes and underscores our role as advocates in decarbonizing design. In addition, both living and non-living materials that we specify are heavy, leading to substantial transportation costs that sometimes exceed the embodied carbon of the materials themselves. Advocating for local sourcing and procurement is a big part of reducing carbon footprints.

Pamela: In terms of changing aesthetics, better carbon performance doesn’t have to look that different. Some things -- like adding cement substitution to your concrete or recycled content in your steel -- look the same. On the flip side, it’s a real opportunity if you can communicate the WHY to those you’re working with and help them become the champions of the effort.

Start the conversation as early as possible, even in the interview. I often find that the

32 BSLA

client’s excited to be a part of it when you explain that we know how to measure and ways to support biodiversity. You might even get selected because you bring that conversation. The world is changing. Awareness is increasing. More and more people want to be on board. Be an advocate. When people start to understand why native plants or why lower water usage materials and understand the connection to issues like species decline, food security, or chemical contamination in water systems, then people start to come on board; once you have made that connection, and then once you start facing challenges of costs or other things, the client might be the champion to keep these in the project. It makes that a lot easier when you can rely on somebody else to help you advocate for a low carbon footprint.

Chris: There’s a question of how to change baseline expectations, even on a small scale. Often, it comes down to individuals reviewing projects and a reluctance to deviate from established norms due to fear of responsibility and potential risk. Take, for example, the situation in many towns and cities where parks predominantly feature concrete paving, lawns, and trees due to maintenance concerns. Anything different can be daunting for the maintenance team, as they fear complaints about upkeep. “Mown and blown” landscapes look tidy. Changing expectations may require a public education campaign to redefine aesthetic expectations, which will also help agencies accept those aesthetic changes. Similarly, big agencies, like the Army Corps of Engineers, have to protect health and human safety with their work. But if they can do that and make more effective natural systems, then that will be a win for them. Getting early adopters is tricky. I’m working on a project where the local agency doesn’t believe in green infrastructure. We lost the battle on a major corridor to daylight a pipe, but they let us do it for a smaller area. So, we will have a demonstration area where they can study it, and the risk is lower. Hopefully, that’ll set a standard for that municipality to be able to consider scaling up those ideas in the future.

Scott: As landscape architects, what can we offer in terms of hope?

CONVERSATIONS / BSLA

Chris: With what’s happening in material innovation, construction standards, and our understanding of natural systems, I have a lot of hope that we can decarbonize the built environment over the next 10 to 20 years. Amazing things are coming out, like net carbon sequestering concrete startups. We understand carbon storage capacity better for long-term ecosystem sinks, specifically salt marsh wetlands, as being much more resilient even in flooding scenarios than people had realized. I also think that we have a great opportunity as landscape architects to make our cities more livable because, at the end of the day, if we can have dense urban living, that’s going to be a lot more sustainable for reducing the overall carbon footprint per citizen of our country.

Pamela: Yes. Cities must be wonderful, walkable, and bikeable environments for people to thrive. As landscape architects, we have a responsibility to enhance the quality of life, which not only contributes to happier, healthier living but also helps preserve natural ecosystems and retain carbon where it belongs. We play a critical role in this larger puzzle.