HOME BOSTON SOCIETY OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTSFIELDBOOK ISSUE 12 2021 The Massachusetts and Maine Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects

“As we continue to navigate territories both familiar and strange, let us each be anchored in our landscapes of home.”

-- Robyn Reed, ASLA

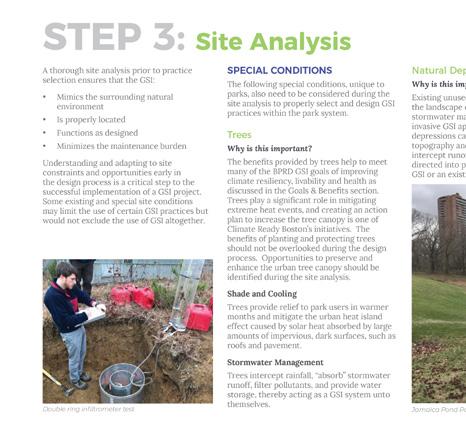

ON THE COVER

Detail from a dreamscape landscape, painted at home during quarantine. Naomi Cottrell, ASLA. Watercolor on cold press paper. Spring 2022.

BSLA Fieldbook. Issue 12. Theme: Home. Including the 2021 BSLA Design Awards. Online at www.bslafieldbook.org

Guest Editors, “HOME”

Jessalyn Jarest, ASLA

Emily Menard, StudentASLA

Corrina Rosetti, StudentASLA

Jen Stephens, ASLA

The 2021 BSLA Fieldbook Editorial Advisory Board

Tom Benjamin

Matthew Cunningham, ASLA Aisha Densmore-Bey

Michael Grove, FASLA

Nicole Holmes

Jessalyn Jarest, ASLA

Kate Kennen, ASLA

Robert Marzilli

Patricia McGirr

Wayne Mezitt

Liza Meyer, ASLA

Barbara Nazarewicz, ASLA

Tim Tensen

Steve Woods

BSLA Executive Committee

Kaki Martin, FASLA, President 2020-2022

Luisa Oliveira, ASLA, President-Elect

Cheri Ruane, FASLA, Trustee

Jef Fasser, ASLA, Treasurer

Members at Large

Michael Radner, ASLA (through 2021)

Carolina Carvajal, ASLA (through 2022)

Carol Moyles, ASLA (through 2023)

Liz LucClowes, ASLA (through 2024)

Managing Editor + Executive Director

Gretchen Rabinkin, Affiliate ASLA; AIA

The Boston Society of Landscape Architects was the first local chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects and today includes 750 landscape architects, students, and emerging professionals from Portland to Provincetown, the Berkshires to New Bedford, Bar Harbor to Boston.

Western Mass Section Chairs

Nate Burgess, ASLA

Jeff Dawson, Affil. ASLA

Maine Section Chairs

Dan Danvers, ASLA (through 2021)

Johanna Cairns, ASLA (starting 2022)

Steven Mansfield, ASLA (starting 2022)

Fieldbook is published by the Boston Society of Landscape Architects. Articles do not necessarily reflect the view or position of the BSLA Executive Committee (ExComm) or BSLA members. Permission to advertise does not constitute endorsement of the company or of the advertiser’s products or services. No part of this publication may be reproduced in print or electronically without the express written permission of BSLA.

The Editorial Board aims to reflect the diversity of our chapter in every way. If you’re interested in participating on the Editorial Board, or have comments, questions, critique, or suggestions about Fieldbook, we want to hear from you. Please be in touch! Email gretchen@bslanow.org

Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

CONTACT

Boston Society of Landscape Architects PO Box 962047 Boston, MA 02196

www.bslanow.org

email chapteroffice@bslanow.org

twitter @BSLAOffice instagram @BSLAOffice facebook @BSLAnow

3

ON THE COVER / BSLA

Dear Members and Friends,

As this book goes to press, we are witnessing the displacement of millions of people due to armed conflicts around the world, as well as increasing numbers displaced due to climate change.

The dramatic volume of humans being forced from their homes is in sharp contrast to the experience that many of us have had this past year: spending more time at home than ever. It’s hard to reconcile. It’s also an opportunity to reflect, learn, and be reinvigorated by the positive contributions our profession makes toward climate change and in providing spaces of comfort to others in need.

Our colleagues who focus on residential design are positively transforming experiences of home for so many. The transformation is not simply about pleasure and beauty, but educating and leading residential clients to be good stewards of their home landscapes and by extension, good stewards of their communities and the world.

This year’s Fieldbook theme of “Home” was borne out of year two of the pandemic and the intensity with which we are all navigating hybridized lives, not to mention the air of lingering uncertainty. We have begun to leave our homes and return to “normal” with a mix of joy and apprehension. We find ourselves walking the optimistic but squishy terrain of transition from pandemic to endemic.

Pre-pandemic we lived two lives -- home and office -- and they overlapped only when direct intention and effort was applied. In our COVID world, those lines have blurred beyond imagination. We have observed each other’s pets, children, house plants, and pandemic-triggered renovation projects because of our collective technological adaptation. And I feel grateful that connectedness within the Chapter is as robust as ever! In one of the most overt and generous statements, Matthew Cunningham stepped forward with a pledge of substantial financial support over three years and challenged others to do the same. So far 31 companies or individuals have pledged an additional $46,725 over Matthew’s gift. This expression of care and belief in this community and its potential is both humbling and highly motivating.

Over the past year, from Western Mass to Maine to Boston, over 400 people joined us outside to participate in our COVID-born “Inside/Out” series of outdoor walking tours -- more than twice as many as we ever saw in an indoor conference. Attendees also broadened well beyond our chapter members to include “civilians”! The word is getting out about the power of landscape architecture.

Our first ever (virtual) BSLA Town Hall drew robust numbers of our community, and online views continue to tick up. Firm leaders have been meeting monthly to

4 BSLA

share support of each other, and, by extension, our remarkable employees and office families, as we navigate leading our firms and our hybridized lives in what seems like one of the biggest boom times of our professional careers. BSLA K-12 engagement is as multi-dimensional and far-reaching as ever as we aim to diversify and positively impact the future of the profession. Similarly, our Advocacy Committee is mapping strategy on issues from professional licensure to climate change. Emerging Professionals are generating a renewed sense of mission and community as well. And as I write, Design Awards season is in swing; we are proud that for the second year, we are bringing in a prestigious leading practitioner from outside of the chapter as guest jury chair and that we’ve made other adjustments to clarify and simplify the process.

This all just scratches the surface of the enormous volume of hard work, creativity, and passion that is brought by the elected “ExComm” and Maine and Western Mass Section chairs and the many, many volunteers at all stages of career, students to emerging- to mid- to “seasoned” professionals. THANK YOU. Thank you for showing up and encouraging others to do the same.

Finally, the BSLA would not be where it is today without the unwavering passion, vision, and tireless work of our executive director, Gretchen Rabinkin. Luisa Olivera is serving as incoming President and I will be transitioning to Past President in November. It’s been an honor to serve this remarkable and inspiring community and I look forward to supporting Luisa and her vision when she steps into the role, as we continue this extraordinary journey in landscape architecture. Thank you for being part of our community.

Kaki Martin, FASLA President Spring 2022

Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT / BSLA

BSLA / LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Dear Reader,

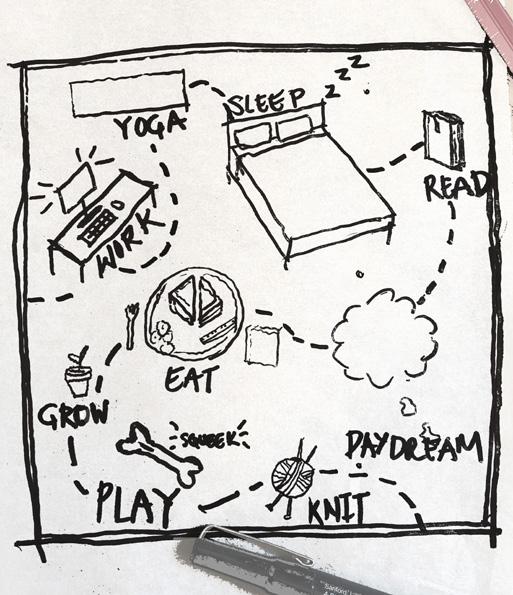

As we enter the third year of an ongoing global pandemic, we have looked inward to our homes to keep us safe, rested, entertained, recharged, and productive.

During these extraordinary times, “home” took on a deeper meaning for many, becoming a place to live, work, learn, and play. While home may be a physical place for some, its meaning transcends the physical boundaries of space. Home is our childhood landscape, and the sensory experiences buried deep in our subconscious. Home is the neighborhood park, and sense of community. Home is the shared experience between different cultures and continents. Home is a place that many long to have.

What does HOME mean to you?

This year, more than ever, seemed like the perfect opportunity to explore the concept of HOME within our BSLA community. As practitioners of landscape architecture, we are often empowered to design the spaces that people call home, whether it be the landscape of an apartment building, single-family house, university campus, or neighborhood park. Perhaps there is a universal language of placemaking that we can apply?

This issue of Fieldbook combines a collection of crowd-sourced pieces, distilled roundtable discussions, thought-provoking essays, and imagery that we hope will inform and inspire. It has given us an opportunity to reflect, reconnect with our roots, and form a clearer understanding of the places that have shaped us. It gives voice to seasoned landscape architects, emerging professionals, students, teachers, contractors, designers, planners, homeowners, and the houseless.

Home is unique to each of us and yet its meaning unifies us. This issue highlights the myriad of meanings of home -- from the physical spaces and sensory environments that shaped our understanding of place, to the profoundly intangible sense of belonging undefined by physical bounds.

We’d like to thank everyone who shared their unique perspective and contributed to a collective narrative of HOME.

Sincerely,

Jessalyn Jarest, ASLA

Emily Menard, Student ASLA

Corrina Rossetti, Student ASLA

Jen Stephens, ASLA

Opposite page and following spread: Details from the Lynn Wolff Memorial Garden at the Womens Lunch Place, Boston, Massachusetts. Photos courtesy Kate Kennen and Offshoots.

Fieldbook HOME Guest Editors

Above, clockwise from top right: Jen Stevens, Jessalyn Jarest, Emily Menard, and Corrina Rossetti.

7Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

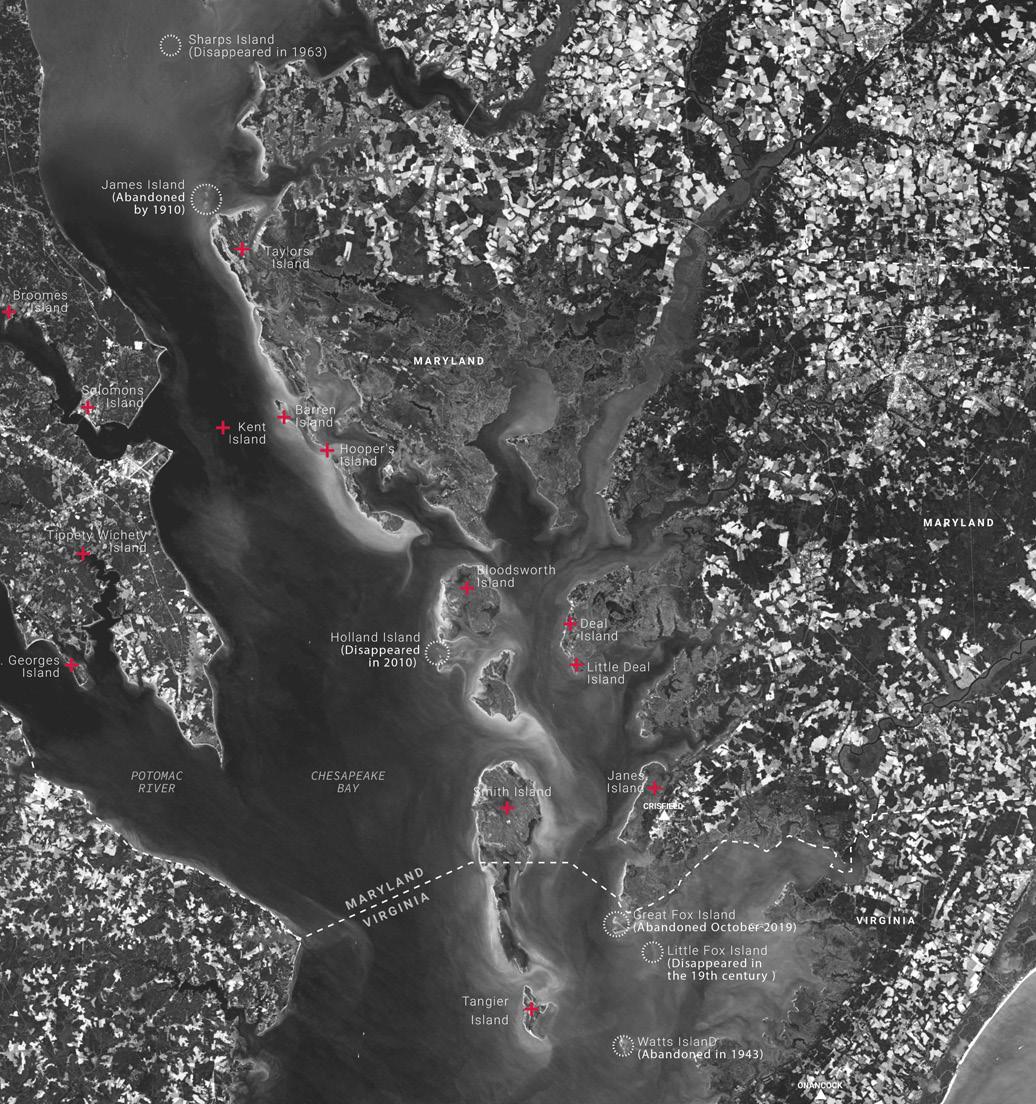

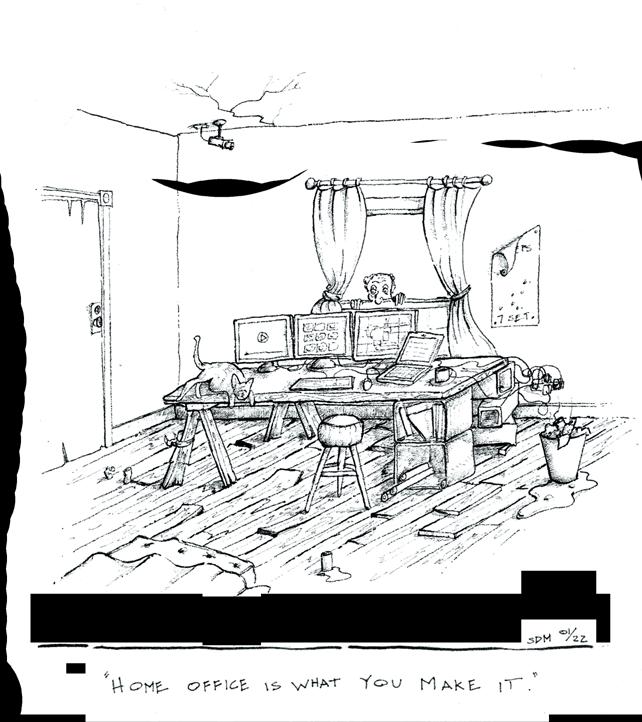

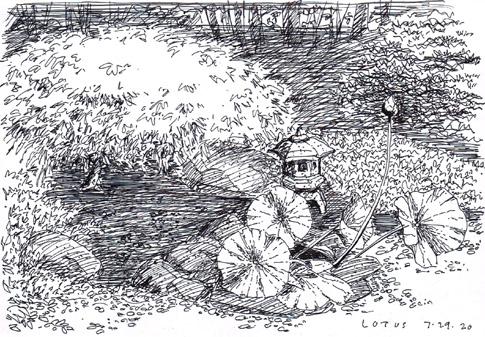

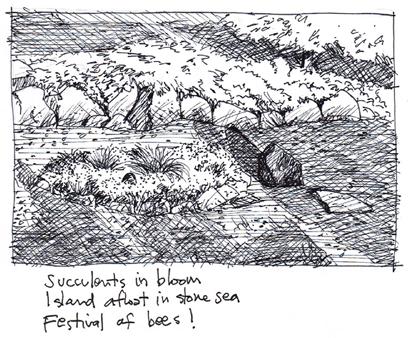

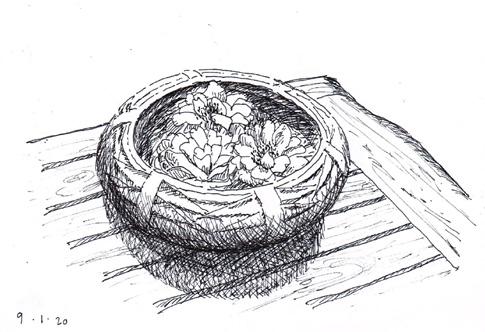

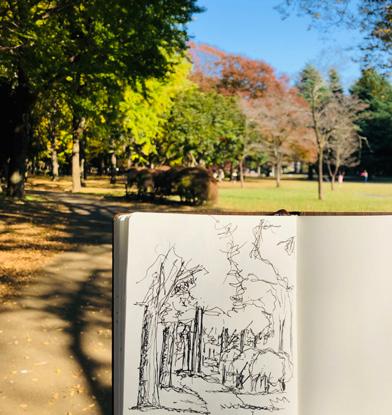

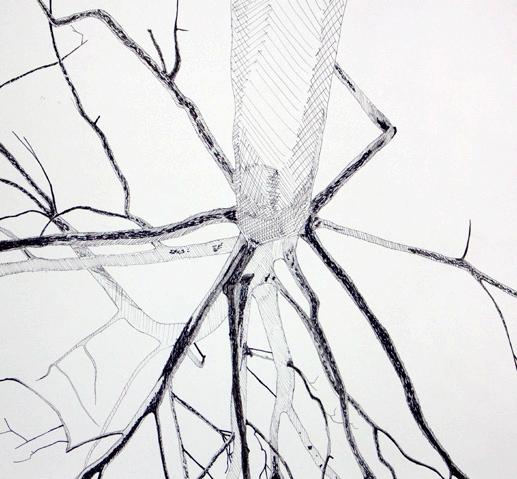

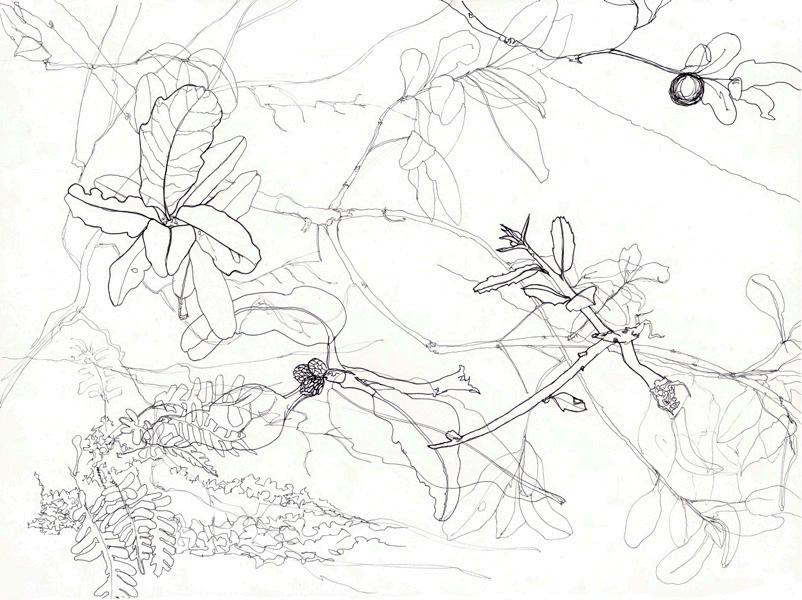

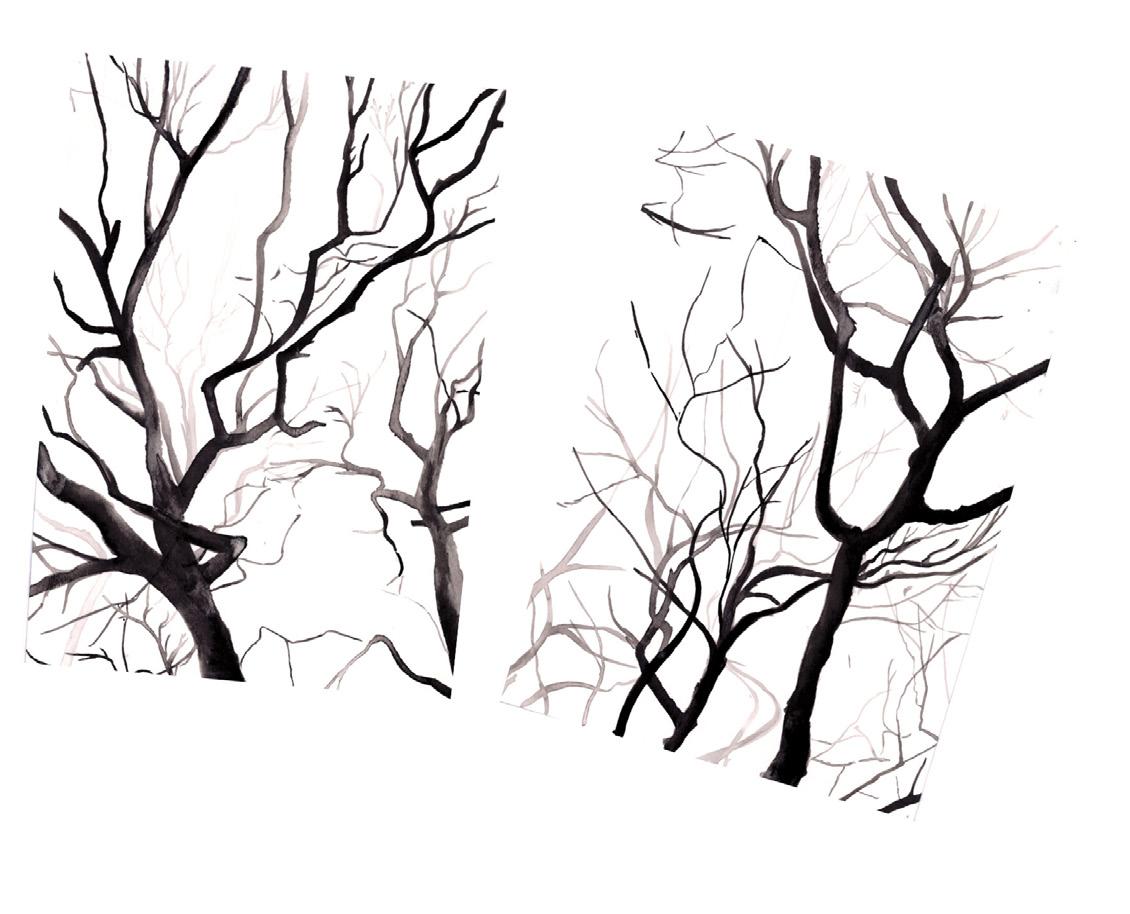

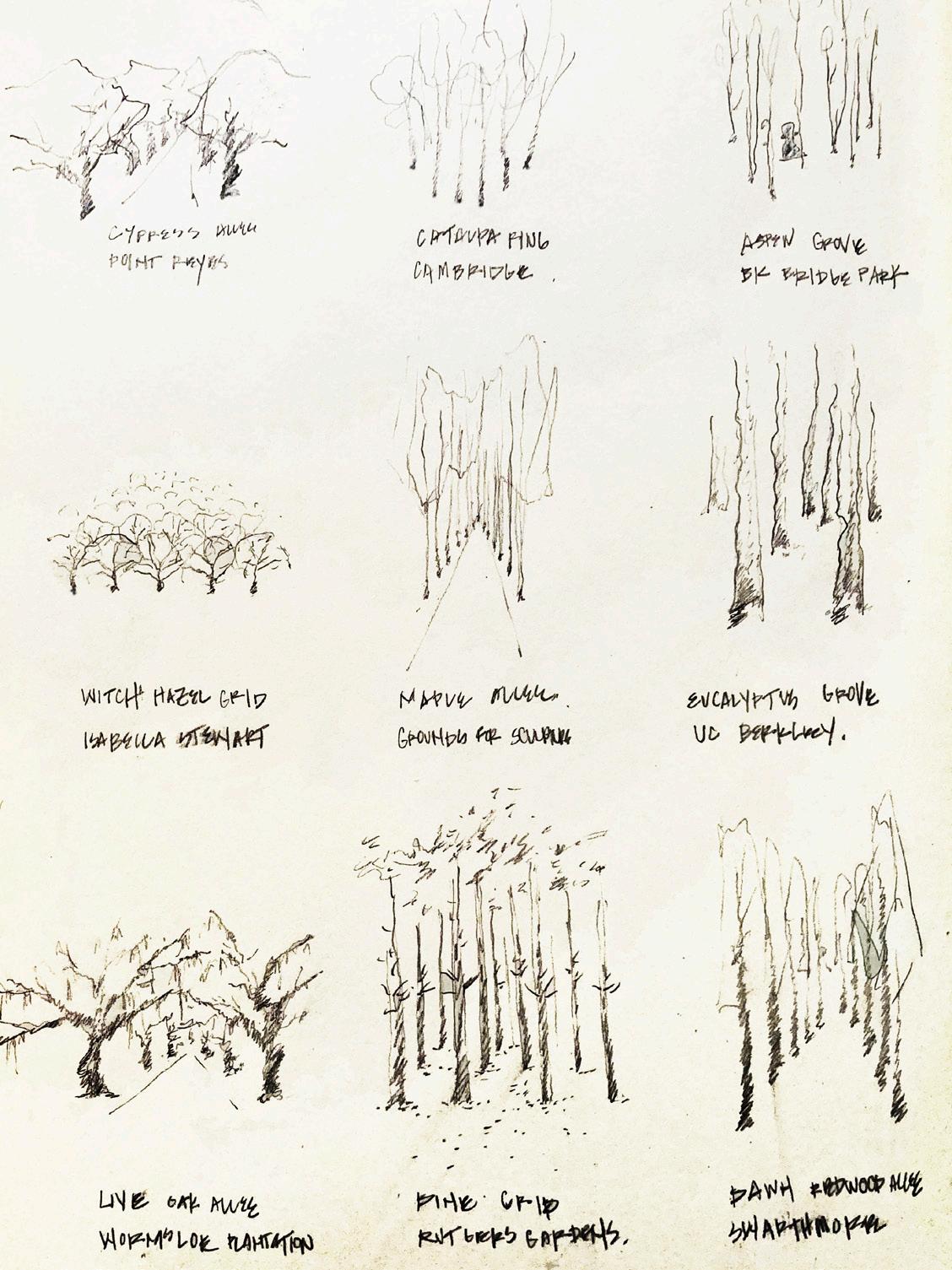

Thinking, Being, Teaching, and Making FROM THE EDITORS Jessalyn Jarest, ASLA Emily Menard, SASLA Corrina Rossetti, SASLA Jen Stephens FROM THE PRESIDENT Kaki Martin, FASLA ON THE COVER WORK + PLAY A BRIEF SNAPSHOT OF DAYS Margo Barajas Inge Daniels, ASLA Yinan Liu Emily Guertin, ASLA John Haven, ASLA Larry Johannesman, ASLA Huyen Nguyen Michael Hunton, ASLA 1 2 4 22 10 HOME 8 Paths of Entry 18 106 28 32 34 38 40 44 52 62 74 78 82 88 102 108 PROMPT: RESIDENTIAL 101 A few things to know, from: Jeremy Martin, ASLA Gigi Saltonstall, ASLA Peter Hunt 104 THE CUMULATIVE EFFECT OF RESIDENTIAL LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE Matthew Cunningham, ASLA A PLANTSMAN’S HOME GARDEN Adam Woodruff PLACEMAKING AND PLACEKEEPING Jennifer Ng THE NATURE OF DWELLING Ellen Merritt, ASLA QUARANTINE GARDENING Gavin Ratliff HOME ON THE IRISH NORTHWEST BORDERLANDS Estello Raganit, Assoc. ASLA NATURE MORTE Supriya Ambwani A HISTORY OF DISAPPEARED GROUNDS Isabella Frontado PROJECT: Unity Park Lisa Giersbach ASLA & Gigi Saltonstall, ASLA PROJECT: The Lynn Wolff Garden Nelle Ward & Kate Kennen, ASLA DRAWING AS DISCOVERY Allyson Fairweather, Assoc. ASLA, Patricia McGirr, and Students of UMass LARP WHAT WE THINK AT HOME Lauren Stimson, ASLA, and Steve Stimson, FASLA TREES ANCHOR LIKE HOME Robyn Reed, ASLA, and Students of LSU THE RESIDENTIAL DESIGN STUDIO Janice Rolf with Michael Davidsohn, ASLA, and Dan Gordon, ASLA PROJECT: Hattie Kelton Apartments Cate Oranchak, ASLA THE DIRT FROM A LANDSCAPER’S PERSPECTIVE Laura Harri 98 PROMPT: RESIDENTIAL = NEW IDEAS Sketches & photos from Fred Anderson Keith LeBlanc, FASLA April Maly, ASLA 70 PROMPT: HOW TO KEEP THE WALLS FROM CLOSING IN? Paintings, drawings & words from Naomi Cottrell, ASLA Kevin MacNeill, ASLA Steven Mansfield, ASLA Christopher Ramage Sydey Trottier

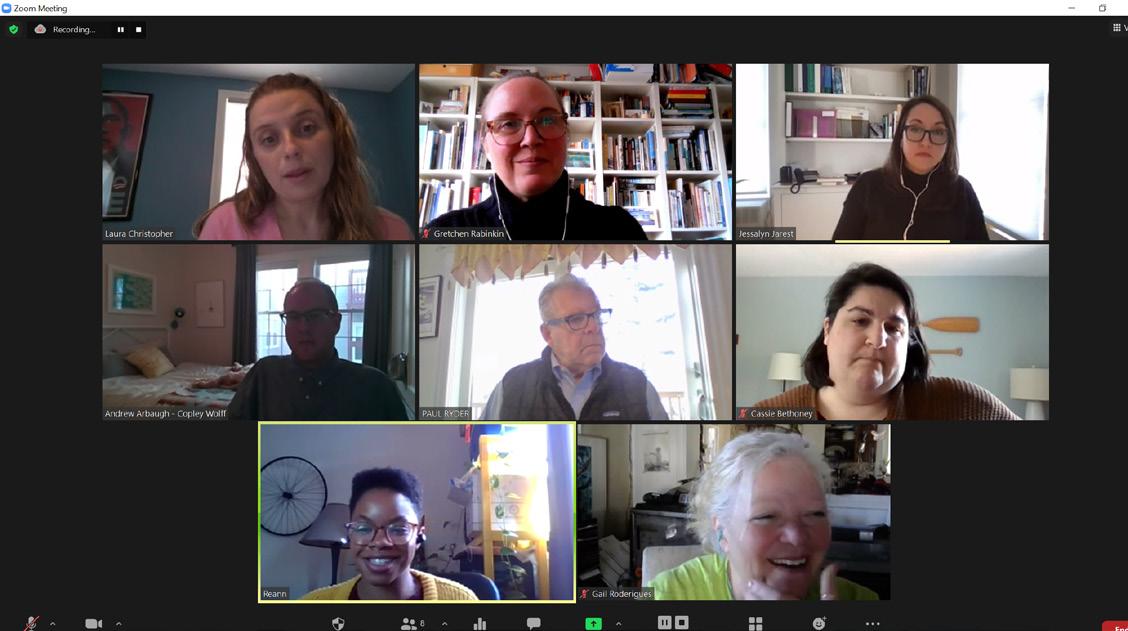

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Chaper Design Awards INDEX TO ADVERTISERS 2020 DESIGN AWARDS 120 130 132 138 190 THE CUNNINGHAM CHALLENGE110 9 On this page Detail of the Lynn Wolff Memorial Garden at the Women’s Lunch Place, Boston, Massachusetts Photo: Kate Kennen, ASLA, Offshoots, Inc. HONOR AWARDS MERIT AWARDS AWARDS of EXCELLENCEPRACTICE TODAY AN INTERVIEW WITH OUR CHAPTER’S 2021 ASLA FELLOWS Yinan Liu interviews Shauna Gillies-Smith, FASLA Eric Kramer, FASLA Dou Zhang, FASLA 146 SPECIAL RECOGNITIONS184 ON THE LIGHTER SIDE COMIC RELIEF Joe James, ALSA 128 NEIGHBORHOOD PARKS JESSALYN JAREST, ASLA, in conversation with ANDREW ARBAUGH, ASLA, CASSIE BETHONY, ASLA, LAURA CHRISTOPHER, ASLA, REANN GIBSON, PAUL RYDER, GAIL RODERIGUES 46 HOUSELESSNESS ADDY SMITH-REIMAN in conversation with NICK ACETO, ASLA, JOHANNA CAIRNS, ASLA, STEVEN MANSFIELD, ASLA, GRACE MCNEILL, BRIAN TOWNSEND 54 MULTIFAMILY DESIGN BARBARA NAZAREWICZ, ASLA, EMILY MENARD, SASLA, CORRINA ROSSETTI, SASLA, in conversation with SHAUNA GILLIES-SMITH, FASLA, DAWN MOTTRAM, TAMARA ROY, AIA, JILL ZICK, ASLA IMMIGRANT EXPERIENCES DANICA LIONGSON, ASSOC. ASLA in conversation with MAHARSHI BHATTACHARYA ISABELLA BROSTELLA, LUIS PEREZ DEMORIZI, LUISA OLIVEIRA, ASLA, SHAINE WONG 66 92 / BSLA HOME

10 BSLA C O N S T R U C T I O N M A S O N R Y M A I N T E N A N C E R . P . M A R Z I L L I & C O M P A N Y 2 1 T r o t t e r D r i v e M e d w a y , M A 0 2 0 5 3 w w w . r p m a r z i l l i . c o m ( 5 0 8 ) 5 3 3 - 8 7 0 0 GREGORY LOMBARDI DESIGN, NEIL LANDINO PHOTOGRAPHY

Boston

Boston

11

Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook Walsh Park, Springfield, MA Your inspiration. Your playground. AREA REPRESENTATIVE 17 PO Medw OFFICE TO FA m obrienandsons www.obrienandsons.complaylsi.com Play shapes us. That’s why we want to help you create the playground of your dreams. Wherever your ideas come from, whatever your vision, we can bring it to life with our unparalleled design capabilities. Learn more by contacting your local playground consultant, O’Brien & Sons, Inc. at 508.359.4200. ©2021 Landscape Structures Inc.

WORK + PLAY

MARGO BARAJAS

Lives in landscape architecture

What originally drew you to landscape architecture? I’ve always aimed to do something creative as a profession. I studied photojournalism as an undergraduate, then became interested in agriculture and apiculture. At some point, I saw a landscape architect give a presentation at a beekeeping conference and that was the first I heard of the profession. A few years later, I was living in Oregon and decided to pursue my MLA at the University of Oregon.

Representing different ages, geographies, and practices, practitioners and students from across the region were asked to respond, in their own words and from their own personal perspectives, to intentionally open-ended inquiries about topics both serious and silly, offering glimpses into the life of a landscape architect.

Do you have a memory of a childhood landscape that you keep with you? A small portion of the Libby River ran through the property where I grew up in Scarborough, Maine. My sister and I were constantly exploring there -- wading to an “island,” stomping on skunk cabbage, and ice skating when it froze in the winter. One summer day we decided to set sail in a boat made from a fish tote. Fish totes have drainage holes. We didn’t make it very far.

What is your favorite thing to do when you aren’t at work? In the winter I read as much as I can. In the summer, I’ll putter awWorking in my garden! I love experimenting with different perennials and bulbs… and my husband and I keep an impressive vegetable garden. I’m known to come in after dark covered in dirt. In the winter I love cooking…. and planning my garden.

What books have you read recently? The Dutch House by Ann Patchett is my favorite read in recent memory. I need to read more! The Tree Book by Michael Dirr and Keith Warren is my favorite landscape book these days. Love Dirr. What it the last meal that you cooked at home? We just made chicken satay with peanut sauce. It’s always been a favorite part of Thai takeout so we re-created it at home… came out great and we will make again.

12 BSLA

INGE DANIELS, ASLA

What is your favorite thing to do when you aren’t at work? In the winter I read as much as I can. In the summer, I’ll putter away in our garden. When we first moved to our home in Boston’s Metrowest, I sketched up a master plan and converted a third of our lawn to native perennial beds and wooded areas. A few years later my husband, Joe, got into gardening too, but was all about a productive landscape (ie. huge vegetable garden, chickens, hop vines) and he poo poo’d my “unproductive” beds. But then he started beekeeping and our interests coalesced! One evening he came home from Bee School and handed me a list of plants we needed as nectar sources. Of course, I’d already planted most of them in my “unproductive” beds.

What is your favorite part of your home landscape? Our back yard is a rather unsightly mish-mash of experiments in progress (plants and management techniques I’m trialing) as well as Joe’s sustainability projects (rainwater collection tanks, solar pool heater and homemade solar dehydrator). The front yard keeps up appearances a bit better! My favorite element is an apple/cherry/pear espalier I designed and have nurtured over the years. It runs along our driveway and turns a residual strip into an interesting, productive and neighborly screen

What books have you read recently? At the moment it’s a little smarty plants stuff, a little classic fiction, and a little selfimprovement: Richard Mabey’s Cabaret of Plants (absolutely fascinating), George Elliot’s Daniel Deronda, and Atomic Habits by James Clear. I recommend them all.

What do you think are the most pressing issues in the design of residential landscapes? The most pressing issue in the world is the climate catastrophe and its subsequent impact on human and non-human habitats. As we all know, there are many ways landscape architecture can make a difference, at all scales. My practice is focused on mitigation at the residential scale, whether it’s adding high-value native plants; rain gardens; converting lawns to woodlands or meadows; or connecting habitat areas with abutting greenways or woodlands. Arguably the greatest way landscape architects can make an impact at the residential scale is by engaging clients in the conversation. I’ve had terrific discussions about the importance of wetlands, singular canopy trees, and even mulch.

YINAN LIU

Can you describe your childhood landscape? Chongqing (China), the city I lived in my childhood is filled with surprising landscapes: buildings leaning on mountains, a peninsula embraced by two rivers, a “vertical street” consisting only of steps, multiple layers of crisscrossing roads and monorail trains passing through buildings. It is even common to see that the foundations of high-rise buildings on one side of a road are higher than the roofs of ten-story buildings on the other side.

What is your favorite thing to do when you aren’t at work? Sleeping till I wake up naturally, reading books, watching TV shows, calling my family and friends.

What books have you read recently? Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harar

What originally drew you to landscape architecture? Even though the dramatic topography often hinders the development of the city that I grew up in, the citizens and builders are enthusiastic about creating a better home. Born and raised in that city, I cultivated an interest in spatial design from an early age. I realized that the design and utilization of space created magic results that turned plight into opportunity. This was what originally drew me to landscape architecture. What do you think are the most pressing issues in the design of residential landscapes? Outdoor space of residential landscape should be the good connection and continuation of indoor space. The pandemic might increase the demand for multi-purpose outdoor spaces that could seperate people to different size of groups and support different activities, such as seating, working, gathering and so on.

13Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook PATHS OF ENTRY / BSLA

EMILY GUERTIN, ASLA

Can you describe your childhood landscape? I think of myself as a New Englander whose sense of place and design sensibilities have been shaped equally by myriad of diverse spaces, both built and natural environments that make up the region. That said, there is no doubt that the paths I frequented in Vermont’s rural Champlain Valley are imbedded in me. Acres of craggy wetlands, pristine orchards, bright meadows, and rolling hayfields dotted by sculptural shade trees and delineated by stonewalls or hedge rows were commonplace. As a kid, the vastness along with clear organization and patterns drew me in to look closer and more broadly as I traveled outside of my small Vermont town. I loved the edges where two different spaces met – often in harmony but sometimes in harsh contrast. Sitting in those edges, perhaps picking berries, I began to learn New England is full of stubborn commonality and adaptability

Do you have a memory of a childhood landscape that you keep with you? The soft symphony of marcescent trees immediately transports me to the many adventures spent in woodlands. Specifically picturesque, quiet morning walks unexpectedly interrupted by snow cascading off limbs and boughs. Those fleeting moments were magical on so many levels – a glimpse to hidden fauna – a darting rabbit or a perched owl would take flight. Certainly I learned to have a keen eye during those walks.

What is your favorite thing to do when you aren’t at work? Exploring with my daughters –their curiosity is contagious and inspiring.

What originally drew you to landscape architecture? The concept of being able to make the world a better place; I still truly believe in this! I am grateful that my daily practice allows me to celebrate, explore and collaborate through design at the intersection of art, ecology and sustainability.

What is your favorite part of your home landscape? My garden is my underfunded laboratory! Large plantsman endeavors are planned and the whole family experiments and observes together. Last year’s biggest excitement was watching a praying mantis create a home and lay eggs.

Wouldn’t it be great if every homeowner manipulated part of their landscape to exist as a native garden patch to see what else is possible in this world?

Larry Johannesman

14 BSLA

JOHN HAVEN, ASLA

Do you have a memory of a childhood landscape that you keep with you? ? We would visit my grandparents on Martha’s Vineyard every summer and they had the most eclectic garden and landscape. There was no lawn on their property. The house was surrounded with native vegetation and the small gardens they had created. We would pick and eat blueberries, gather wild daisies, and deliver the food scraps to the compost heap. My Gram would experiment with plants and would always be trying something new or taking me to the nursery to shop around. The memory of this wild and experimental landscape definitely inspires some of my work today. Not everything is perfect!

What is your favorite landscape, anywhere? TThis is a bit odd, but I love seeing and observing the naturalized landscapes along roads and highways. I spend a good amount of time in my car driving to projects on the Cape and to New York and the Berkshires, and I’m always amazed at the spontaneous blending of plant colonies, naturalized groves, and seasonal color. Such great inspiration for planting design! Driving down the winding Taconic Parkway when the meadow grasses are at their peak is just amazing.

What is your favorite part of your home landscape? The previous owners planted Rosebay Rhododendron along the hill behind our back yard. They tower 10’-15’ high. It’s unlike anything else in the neighborhood, and I could never replicate it! It’s spectacular when it blooms in June. We also have a small parcel of woodland area in the back of our property that has essentially remained untouched. The kids have used it to build fairy houses, forts, and even a small bike trail. It has naturalized over the years with Hemlock, White Dogwoods, Pennsylvania Sedge, and Aster. My neighbor recently cut down some trees along the property line that allowed more sunlight to come through. The explosion of native plants that emerged was unreal!

What is the last meal you cooked at home? Chicken pot pie from scratch. Two thumbs up from daughter, Two thumbs down from son. This rating system consistently switches back and forth between them with whatever I make.

LARRY JOHANNESMAN, ASLA

Can you describe your childhood landscape? I have vivid memories of escaping from the house with friends to play in the “Little Woods” or the “Big Woods” in Lake Ronkonkoma, New York. We biked and ran around on the trails and even made sled runs there in the winter.

Do you have a memory of a childhood landscape that you keep with you? In the woodsy, back corner of our suburban house lot, my friends and I built a fort that started with a Saint Bernard double doghouse and ended up having twelve rooms. We used every scrap piece of lumber we could get our hands on. My friends and I pretty much lived in the thing all summer.

What is your favorite landscape, anywhere? Wow! There are so many. Two come to mind quickly: Joshua Tree and Fletcher Steele’s Camden, Maine Library Amphitheatre. One natural and one built and both are so inspirational.

Is there a place that you’ve rediscovered? Working from home for two years now, I keep rediscovering my own three acres in Mount Vernon, Maine. I see the huge trees, stone walls, different wildflowers and all the critters coming and going. It’s been amazing to visit and manipulate the same landscape over and over. Oddly, it’s challenged me to look more deeply at what’s familiar or just taken for granted.

What’s the last change you made to your home landscape? I have a rural three acres that backs up to 500 acres of woods. To decrease mowing grass, I love playing with letting different size patches grow wild and study what happens. Dragonflies galore in one, waves of hawkweed in another and last summer an eye-popping 150’ x 20’ Queen Anne’s lace swath.

What is your favorite part of your home landscape? A giant, unbelievable, spectacular in every season black walnut tree. What do you think are the most pressing issues in the design of residential landscapes? We need to do way less mowing, weed whacking, and leaf blowing and all that comes with those activities. I held the line on two of the three since becoming a homeowner, but still have mowing guilt every week. Wouldn’t it be great if every homeowner or residential community designed and manipulated part of their landscape to exist as a native garden patch to see what else is possible in this world?

15Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook PATHS OF ENTRY

/ BSLA

Michael Hunton

“QUINN” HUYEN NGUYEN

What is your favorite thing to do when you aren’t at work? I really enjoy walking in my free time, especially on sunny days. Previously, I lived in Cambridge, and last summer, I spent hours every day walking along the Charles River from Cambridgeport to the Cambridgeside shopping center. Sometimes I walked to Assembly Square or Harvard School in Allston, had a drink from Starbucks, then walked back home. I missed that time like crazy! Recently, I have moved to live next to Fenway Park. Although the weather has been colder and darker, I still keep my habit of walking to enjoy sunny days. I believe walking can help with keeping me both physically and mentally healthy.

What books have you read recently? I am reading Structures of Coastal Resilience by Catherine Seavitt Nordenson, Guy Nordenson, and Julia Chapman. The book is very inspiring and informative as I look at coastal protection strategies for my thesis research at school.

What does a day in your life look like? I always try to get a work-life-school balance not to feel overwhelmed because of work or school. I like switching different kinds of activities, which keeps me healthy and positive. I wake up around 7:30 am to prepare breakfast. I also cook for lunch simultaneously so I can save time. After having breakfast, I start working at 9 am. I am working for a landscape architecture design firm in Waltham, but we mostly work remotely as some folks have kids, and they are afraid of spreading the virus to their kids. I usually take a break around 2 pm, and if the weather is nice, I will go out for a short walk.. On the way, I will grab a matcha latte from my favorite store. Then I have lunch and come back to walk until 5:30pm or 6pm.

After work, I usually spend 30-40 minutes working out before having a light dinner. I have classes twice a week;7pm – 10pm are my class hours. Then, I call my mom in Vietnam until I fall asleep.

What is your favorite landscape, anywhere? I love the Assembly Square that I came to nearly every day last summer.

My definition of home has never been a place, really. Now, more than ever, home is when I am at peace.

16 BSLA

MICHAEL HUNTON, ASLA

Do you have a memory of a childhood landscape that you keep with you? I grew up in a family of six on a dead-end street up the hill from a local park. Our house was a loud bunch of Italians, so it was fun to escape from the noise every now and then with my older brother and run down to the park to kick the soccer ball around. Ah, the smell of freshly cut grass…

Is there a place that you’ve rediscovered? What’s one way that your thinking of home landscape has changed? I’ve traveled quite a bit for work and music, and during my time serving in the military overseas. My definition of home has never been a place, really, now that I think of it.

Going back to me as a kid too. But I think my experiences have solidified that notion, and now, more than ever, home is when I am at peace. Home is a space in time where everything makes sense. It could be anywhere really, absolutely anywhere. Home is a peaceful place where I can just be..

What is your favorite thing to do when you aren’t at work? Writing songs / playing guitar, cooking, or going for a hike. Anything that doesn’t involve a screen!

What originally drew you to landscape architecture? As a teenager, the pocket parks of Jersey City and New York City always served as a place of solace for me. I honestly had no clue what landscape architecture was then, but I already liked it. I always loved sketching and city plazas and getting out into nature for backpacking trips. When I stumbled upon the landscape architecture program at Rutgers at a friend’s summer barbeque, the focus of study seemed to align with everything I enjoyed, so it made it an easy decision to investigate further!

What is your favorite landscape, anywhere? A fried haddock sandwich, a pint of beer, and a view of the ocean!

Margo Barajas, is a Landscape Designer with Aceto Landscape Architects. She is a 2018 Master of Landscape Architeecture graduate from the University of Oregon, and a 2017 Boasberg Fellow of The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Inge Daniels, ASLA, leads her own landscape architecture practice, Inge Daniels Design, and is a founding principal of the landscape collective, COLLAB. A graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, she was Senior Designer at Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates before she went out on her own.

Emily Guertin, ASLA, is a Senior Landscape Architect at Gregory Lombardi Design where her concentration of residential design is influenced by her sense of humor, adventure, and New England sensibility.

John Haven, ASLA, is Senior Associate at LeBlanc Jones Landscape Architects. He has served for many years on the Design Review Advisory Board in Dedham, Massachusetts, and is a graduate of the landscape architecture program at Purdue University.

Michael Hunton, ASLA, is New England Landscape Architecture + Planning studio lead at LANGAN. A former captain in the US Marine Corps, he received his BS in Landscape Architecture from Rutgers University.

Lawrence Johannesman, ASLA, is a Landscape Architect with the Maine Department of Transportation Multimodal Program. He is a graduate of the landscape architecture program at Louisiana State University.

Yinan Liu is a Design Associate at Ground, Inc. She holds a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture from Lousiana State University and an MLA from Harvard GSD.

Huyen Nguyen, is a Junior Landscape Architecture Designer at G2 Collaborative, and a current student in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the Boston Architectural College.

17Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

PATHS OF ENTRY / BSLA

18 BSLA

19Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

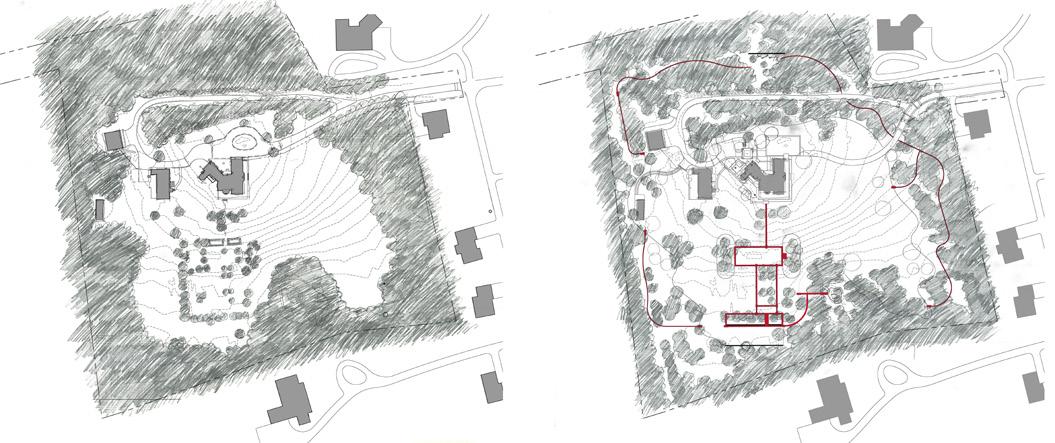

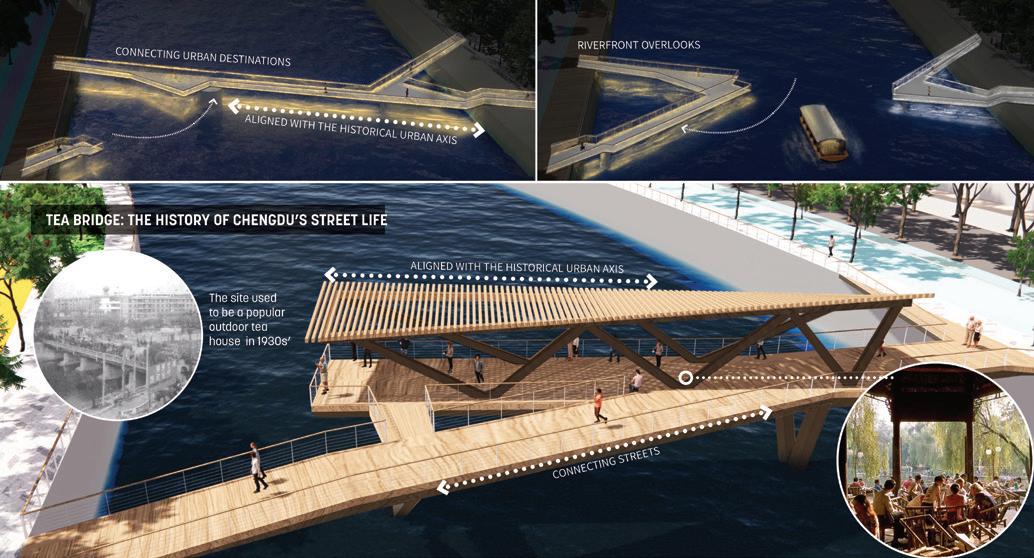

A New Suburban Ecology. Landscape Architects: Matthew Cunningham Landscape Design. 2020 BSLA Honor Award in Design.

A New Suburban Ecology. Landscape Architects: Matthew Cunningham Landscape Design. 2020 BSLA Honor Award in Design.

20 BSLA

MATTHEW CUNNINGHAM

THE CUMULATIVE EFFECTS of RESIDENTIAL LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

In the face of crises spanning global pandemics, political upheaval, and degradation of the planet’s natural systems, all with a backdrop of human inequality, the power and importance of the work of landscape architects has never been clearer to those outside our profession. Our place in this moment is unprecedented. The cumulative impacts of residential landscape architecture are just beginning to be more widely understood, and residential practitioners have the potential to play an enormous local role in these global transformations.

With professions and trades actively redefining themselves and evolving, technology plays a stronger role than ever in our lives. The remote/hybrid work-life blur continues to force all new patterns of living. “Home” has an entirely new meaning, and we collectively expect more from our domestic environments than ever before. What used to be a place almost exclusively for private life must now anticipate and accommodate the known and unknown. Beyond fluctuating work and school patterns, home must support multiscale social activities, incorporate areas for exercise and rejuvenation, and adapt to literally everything in-between. As humans “retribalize“ in this digital era, as Marshall McLuhan

arguably predicted, we must carefully consider where, why, and with whom we live.

As we question our previous use patterns and reconsider how we engage with our surroundings, we need to take a moment to listen and observe. Erosive pressures from increasing populations with corresponding climate changes have placed urban, suburban, and rural ecologies, and those who live in them, under assault. Yet, abundant and resilient life still adapts and flourishes in most places. What are our plant and animal communities telling us? What can we learn through careful observation of our local environments and ecological systems?

Vegetative communities evolved for millennia and successfully adapted to ever-changing weather patterns. Unfortunately, the accelerated pace of change is happening far too fast for our fragmented suburban landscapes to keep up with. Suburbanites have maintained strange relationships with their land, focusing more on aesthetic values rather than biological function. We should seize this opportunity to reinvent and reinvigorate our relationships with nature, because frankly, everything depends on it.

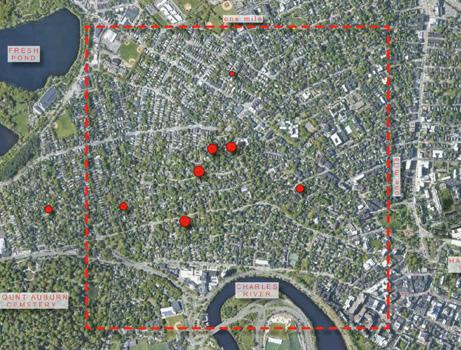

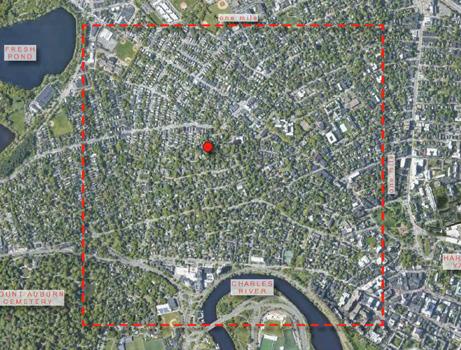

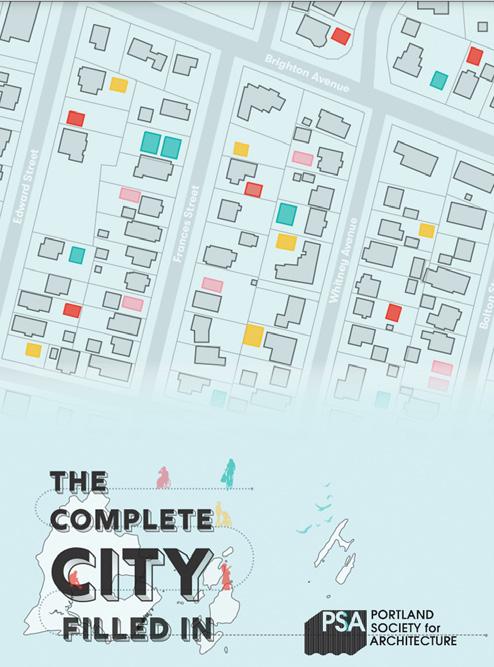

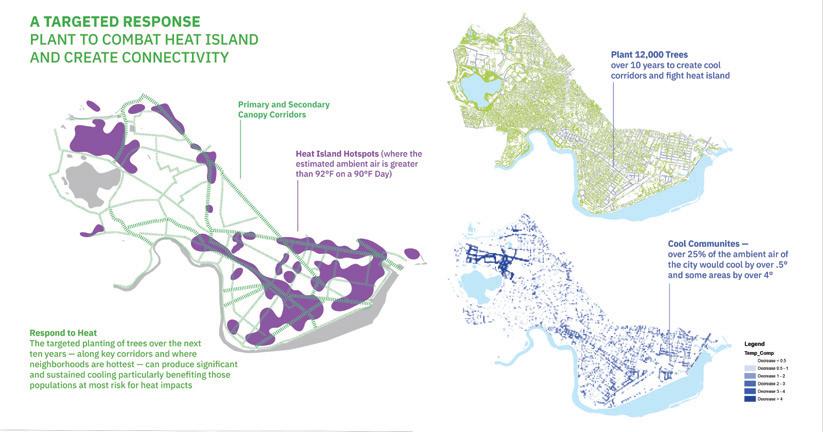

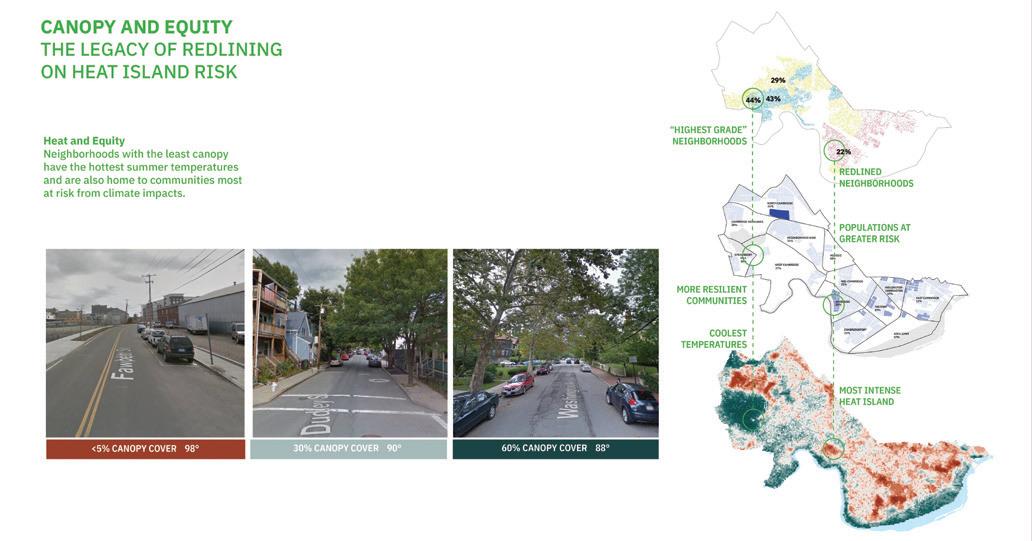

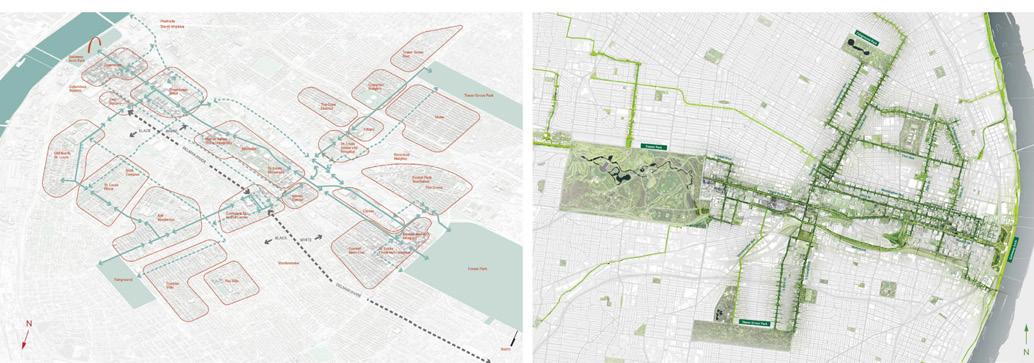

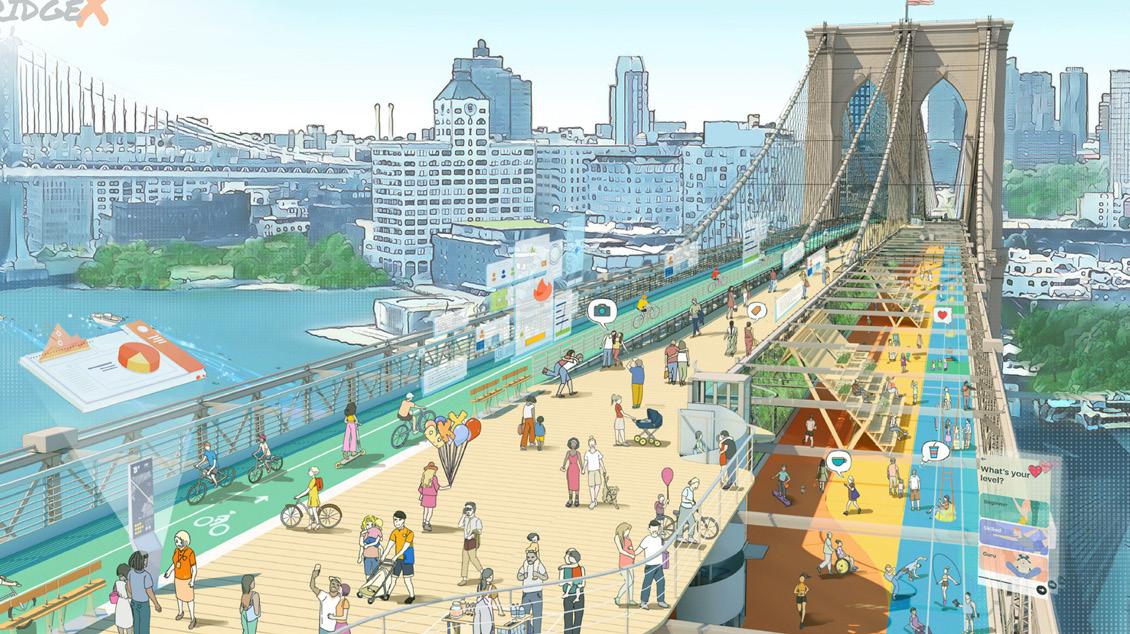

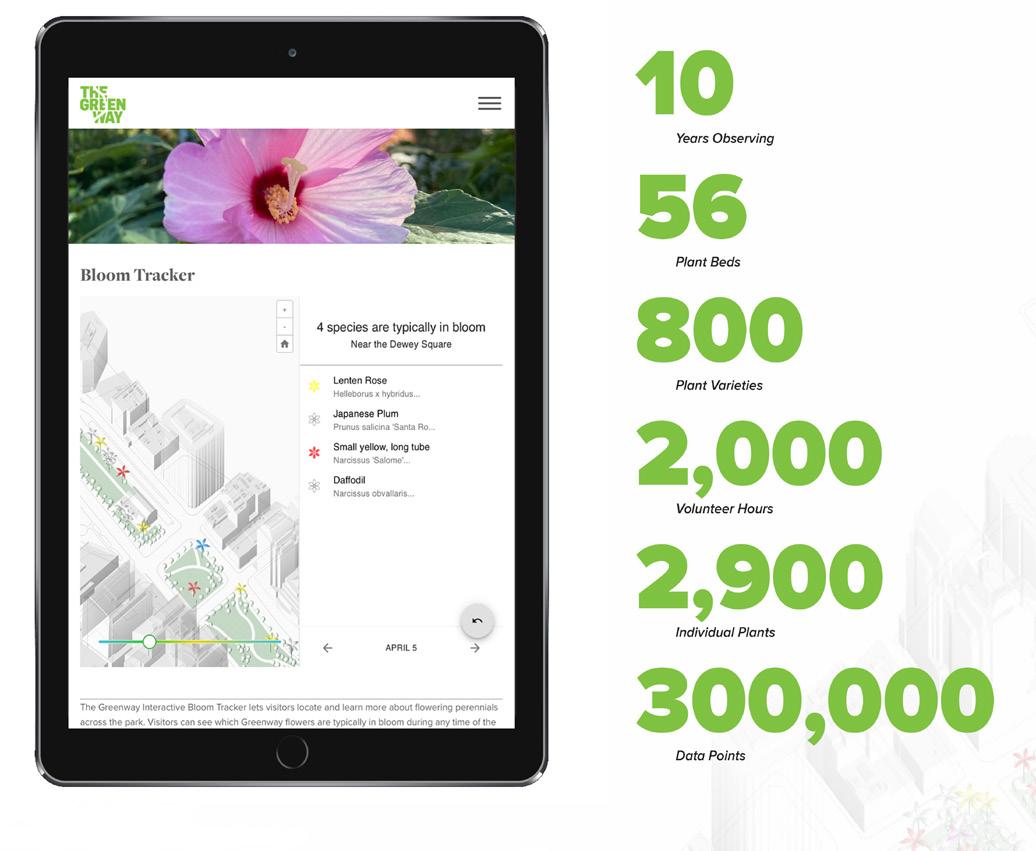

The growing impact of single family residential landscape architecture over time. The red squares indicate one square mile in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the red dots show MCLD projects. Left, in 2010; right, in 2014...

21Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

Residential landscape architects are shaping an enormous, rapidly growing, multi-billion-dollar industry, and we are a driving force of innovation. By transforming the visual and built narratives of garden design, we shift the public’s perception of the importance of being connected to outside spaces, proving the vital role that domestic landscapes should play in our collective well-being. The demand for residential landscape architecture has never been greater, and it appears this trend is here to stay as various residential markets suggest continued growth to keep up with increasing populations, and accommodate the ever-changing realties of the new workfrom-home culture we’ve adopted.

Over the past two decades, I have watched the scale and complexity of my firm’s work grow at a tremendous rate. The problems we tackle are incredibly nuanced, and the transformations often require multi-year commitments. We regularly assemble and lead sizable multidisciplinary teams, navigate complicated zoning bylaws and environmental regulations, and coordinate sophisticated permitting processes. We work directly with individual homeowners to protect their investments and oversee tens of millions of dollars’ worth of landscape construction contracts annually.

We are business leaders, entrepreneurs, employers, educators, advocates, and active participants in shaping communities.

We actively steer clients away from symbolic “greenwashing” gestures by putting our expertise to work to piece site-specific

ecologies back together, one garden at a time. With these newly informed perspectives, we have ample opportunities to repair fragmented natural systems; preserve, restore, and create habitat; design systems that sequester carbon and build healthy soils; dramatically improve water quality and reduce irrigation demands by specifying native and indigenous plant communities; and help buffer communities from destructive weather and climate. We do all this while embracing the realities of how people gather, work, and live. The health of all communities in all regions depends on square-foot, squareacre, and square-mile interventions because it will take efforts at all scales to shape the most resilient future.

Climate change is not one person’s, or even one group’s, problem to fix. The smallest interventions can add up over time in meaningful ways. In our field, there are generalists and specialists each adding legitimate value to the roles they perform. For the first time in my career, I find myself not having to defend the work I do within my own profession, and it is becoming more and more clear that residential landscape architects are transforming the visual and built narratives of garden design by shifting the public’s perception of the importance of being connected to nature, further proving that “home” has never been more important, inside and out.

The next generation of landscape architects has unprecedented opportunities ahead, and our profession is positioned to create real solutions to the support the fight against of climate change.

Above left, in 2022. Over time, the environmental benefits of these renovated residential landscapes -- such as the restortion of native habitat, or mitigation of urban heat -- stitch together to improve the ecology of the city...

22 BSLA

Our futures depend on their collective and individual abilities to explore and adapt to our ever-changing environment. We have a responsibility to teach residential landscape design in our academic programs, and we must reinforce the valuable roles landscape architects play.

The medical, psychological, and social benefits of living in communities with healthy and resilient landscapes are vast—from decreased cortisol levels, improved mental health, and a general sense of well-being by enhanced connections to the land and nature. We blend art and science and share a collective responsibility to lead and teach the vital role that plants and considered design play in shaping the human experience.

There are skeptics who suggest that our yard-by-yard impact is not enough to make a measurable impact on climate change, but this is a limited view. Design is not just about reversal but also directing and confronting new systemic forces together. By reconnecting fragmented ecologies, residential landscape architects not only demonstrate valuable lessons about land stewardship; they also have unprecedented positive effects on the health and ecological balance of our communities. To maximize our impact, we must do this work together.

THOUGHTS ON HOME

Matthew Cunningham, ASLA, is the founder of Matthew Cunningham Landscape Design and derives immeasurable passion from the landscapes of the region and from his rural roots in the verdant, rocky coast of Maine. MCLD is dedicated to merging design excellence with ecologically sustainable principles. Based in Stoneham, Massachusetts since 2004, MCLD recently opened a second studio in Portland.

...of the metro region, and, even, New England. Together, the cumulative impact of residential landscape architecture goes well beyond property lines. It’s part of the essential infrastructure to address climate change.

23Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

/ BSLA

Adam Woodruff is a garden designer working throughout the United States. His work has been featured in several recent books on naturalistic planting design as well as in Gardens Illustrated, Architectural Digest, Fine Gardening, Horticulture magazine, Better Homes & Gardens and other publications.

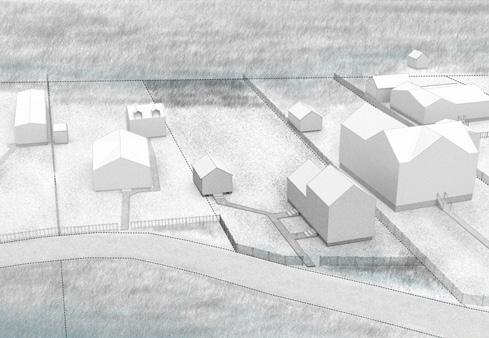

This photo is his home landscape, in construction. The photos on the following pages show the plants through the seaons. All photos by Adam Woodruff.

24 BSLA

ADAM WOODRUFF

A PLANTSMAN’S HOME GARDEN

I am a garden designer. Plants are my passion and they play a central role in my projects. Depending on the size and scope of a project, I find design solutions are often accessible through thoughtful planting design.

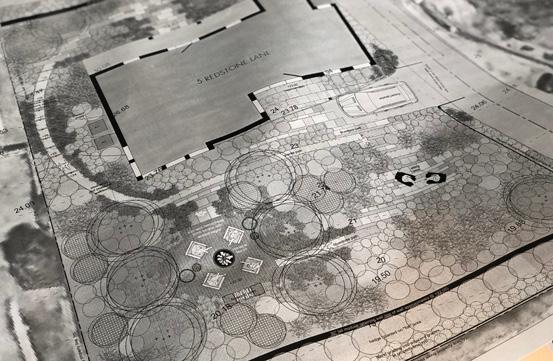

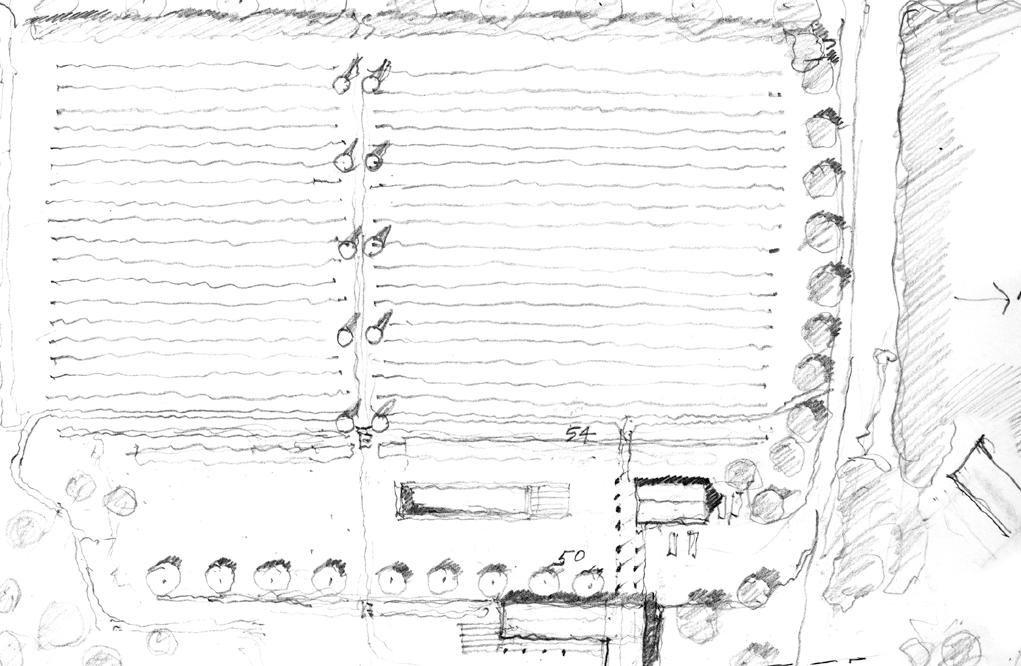

I routinely partner with landscape architects to provide landscape architectural and master planning services to my clients. My personal garden is an example. It was de signed in collaboration with landscape architect Matthew Cunningham. It was built by Robert Hanss and I planted the garden in the summer of 2020.

Our property is situated behind a public boatyard in historic, Marblehead, Massachusetts. Access to the harbor is via a right-of-way using our drive. Substantial grading and screening were needed to create an intimate space, free from distraction, that would also make the most of the borrowed landscape and long views.

A modular concrete block retaining wall was installed along the south property boundary to level the grade and accommodate off-street parking. Cunningham designed a herringbone-patterned brick terrace to function as the main seating area. It is anchored by four ‘Royal Purple’ smokebush, chosen for their rich color and ability to be coppiced. The terrace was installed with an eroded edge allowing it to float in the space. Linear bands of reclaimed granite curbstone act as pathways through the garden and serve as a secondary seating area. Crisp hedges of yew and columnar hornbeam were installed atop the retaining wall and along the drive to improve privacy.

Planting design considerations for the project included the ability to thrive in a seaside environment, the aes thetic value of each plant (e.g., flower, foliage, seed-head, fragrance), the length of bloom and seasonal interest, views of the garden from higher floors in the house as well as one’s experience when in the garden.

The rear garden evokes a stylized meadow. An ex perimental main planting of approximately 30 taxa (low-growing perennials, grasses, bulbs and annuals) flows between the two seating areas. It is a matrix, com posed of three plant groupings, organized in repeating diagonal bands. Several key plants emerge from strategic positions within the bands to give a feeling of sponta neity. The arrangement creates an illusion of depth in the small space. The pattern also ensures that a semi-skilled gardener or homeowner with limited knowledge of plants can maintain the garden. Between the main planting and the yew hedge, a neutral band of grasses was planted to obscure a slight depression in the grade. In addition, the grasses act as a foil for the more complex main planting in the foreground. Cool-season grasses were favored for our location, with a few exceptions, because they emerge early in the spring, and cover the ground more quickly than their warm-season counterparts.

While this style of planting is forgiving, it requires supervision and editing in the establishment phase. If individual species under-perform or over-perform, they are easily replaced or adjusted to bring the display back into balance.

25Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

THOUGHTS ON HOME / BSLA

REAR GARDEN PLANT LIST

Matrix Band 1

Emilia javanica

Angelica gigas

Allium caesium, Allium tripedale

Tulip ‘Spring Green’, Tulip ‘Black Hero’, Tulip ‘Paul Scherer’

Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Eragrostis spectabilis

Asclepias tuberosa

Echinacea pallida

Kniphofia ‘Apricot’

Limonium latifolium

Stachys ‘Hummelo’

Veronica longifolia ‘First Glory’

Matrix Band 2

Eryngium x zabelii ‘Big Blue’

Gaura lindheimeri ‘Whirling Butterflies’

Geranium ‘Azure Rush’

Salvia nemorosa ‘Caradonna’

Matrix Band 3

Achillea ‘Hella Glashoff’ died in 2021. Replaced with Achillea ‘Walther Funcke’

Allium ’Summer Beauty’

Allium cristophii, Allium sphaerocephalon

Calamintha nepeta ‘Montrose White’

Echinacea purpurea ‘Pow Wow White’

Geum ‘Mai Tai’

Muscari paradoxum, Muscari armeniacum ‘Valerie Finnis’ Origanum laevigatum ‘Herrenhausen’ Polianthes tuberosa

Sesleria autumnalis

Neutral Band of Grasses

Briza media

Camassia leichtlinii ‘Blue Heaven’ and ‘Caerulea’ Dianthus carthusianorum

Eremurus ruiter ‘Cleopatra’

Molinia caerulea ‘Poul Petersen’

STREET SIDE GARDEN PLANT LIST

Allium ‘Purple Rain’

Chionodoxa ‘Blue Giant’

Narcissus ‘Bridal Crown’

Matteuccia stuthiopteris

Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Hakonechloa macra

Molinia caerulea subsp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’

Sesleria x ‘Greenlee’s Hybrid’

Acanthus mollis ‘Morning Candle’

Actaea x ‘Queen of Sheba’

Alchemilla mollis ‘Thriller’

Amsonia ‘Storm Cloud’

Anemone ‘Andrea Atkinson’

Aquilegia vulgaris var. stellata ‘Black Barlow’

Asarum europaeum

Astilboides tabularis

Ceratostigma plumbaginoides

Euphorbia amygdaloides var. robbiae

Galium odoratum

Geranium ‘Azure Rush’

Podophyllum peltatum

Polygonatum odoratum ‘Angel Wing’

Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Erica’

BSLA

THOUGHTS ON HOME / BSLA

Nothing surpasses the natural beauty and timeless durability of domestic granite

East Otis,

800-832-2052 Fax: 413-269-6148 www.williamsstone.com info@williamsstone.com

28 BSLA

Celebrating 75 Years of Superior Domestic Granite Dimensional Steps Curb Seatwalls WILLIAMS STONE COMPANY WS Williams Stone Company Inc. 1158 Lee-Westfield Road P.O. Box 278

MA 01029-0278 Tel:

29Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook OUR FINE GARDENING SERVICES CULTIVATE BEAUTY AND BOUNTY WHILE IMPROVING THE ENVIRONMENT WE LIVE IN. ACCREDITED ORGANIC LANDSCAPE PROFESSIONALS Edible Garden Design & Maintenance | Fruit Tree & Shrub Care Cold Frames | Pollinator Gardens | Chicken & Chicken Coop Care Organic Land Care | Ecological Landscape Solutions 774-277-2575 BotanicaFineGardens.com A DIVISION OF R.P. MARZILLI LANDSCAPE PROFESSIONALS ORGANIC LAND CARE ACCREDITED PROFESSIONAL MarzilliBotanica_BSLAfieldbook_Full.indd 2 10/13/20 1:56 PM

Willie ‘Woo Woo’ Wong Playground, shortly after opening day February 2021. This photo: courtesy Jensen Architects. Photos left and right, below: courtesy CMG Landscape Architecture.

Willie ‘Woo Woo’ Wong Playground, shortly after opening day February 2021. This photo: courtesy Jensen Architects. Photos left and right, below: courtesy CMG Landscape Architecture.

JENNIFER NG

PLACEMAKING AND PLACEKEEPING

Finding a Sense of Home in Your Work

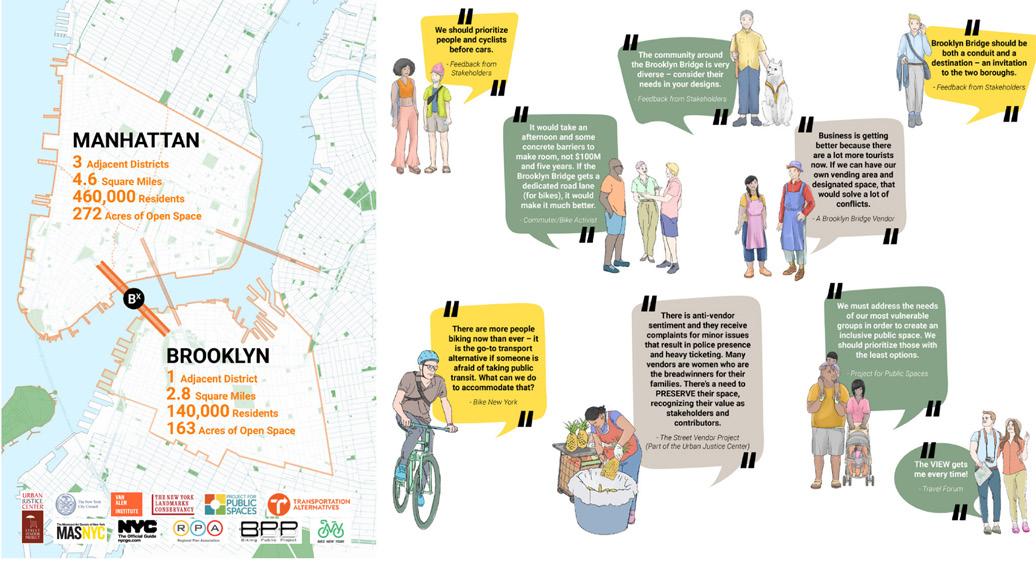

For me, the practice of landscape architecture is at its core, the practice of finding home, and creating a sense of belonging within the public realm. If I think critically about why landscape and home are intertwined in my mind, I think it stems from being raised in quiet Upstate New York, with family memories of state parks, learning to ride bikes in the neighborhood, and endless summers at playgrounds; and being equally raised in Chinatown Manhattan, with the constant hum of people and activity, and with the public realm making itself known in every square inch of the neighborhood.

Over the years, I have had mentors who have shaped this idea that landscape architecture is the practice of “finding home,” and each has taught me their own values around designing for belonging and community.

After graduation, I worked at a small residential landscape architecture firm in New York City. There, I met Heather Morgan, a landscape architect and landscape archaeologist. She believes that we all must be stewards of the land, and landscape architects have a responsibility to empower our clients and the people who use our spaces to develop a sense of connection and responsibility. What better way to create an intimate connection to the land than through residential work? She believes that fostering a land ethic begins at home and we must cultivate that sensibility uniquely for each client.

As a starry-eyed graduate, I learned to search for this meaning in all of my tasks, to find the bigger picture and to remember the end goal.

While at New York City, I worked for Hargreaves New York. At the time, the New York office was small, and the Great Recession’s silver lining is that I had many opportunities to spend time with firm leadership and Mary Margaret Jones. Through our project work, Mary Margaret describes the importance of balancing program with an open framework. To her, the stillness and quiet are just as important to a community’s mental health as the connection to people and activity.

After New York City, I moved to San Francisco and started working at CMG Landscape Architecture. On my first day of work, Chris Guillard took me for a walk in the neighborhood. He pointed out a city that grows over time: one that is equally ever-changing and ever lasting, and one that absorbs the fingerprints of all its users creating a tapestry that we, as designers, could not have predicted. Over the years, I worked on a series of large-scale campus projects, redevelopment projects, and park projects. . Through those projects, I found a commitment to the idiosyncratic landscape – the idea that each site is unique as a space, and distinct from moment to moment. The site should be special and one-of-a-kind, not because of the design, but because of how the people enhance and evolve the place. I realized that design is the framework for accrual and change—that the design shouldn’t be a perfect ending to a problem, but rather a starting point for dialogue and habitation. It is an opportunity for people to take ownership and even possibly change the design over years of being in that space.

31Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

THOUGHTS ON HOME / BSLA

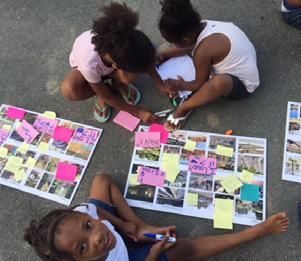

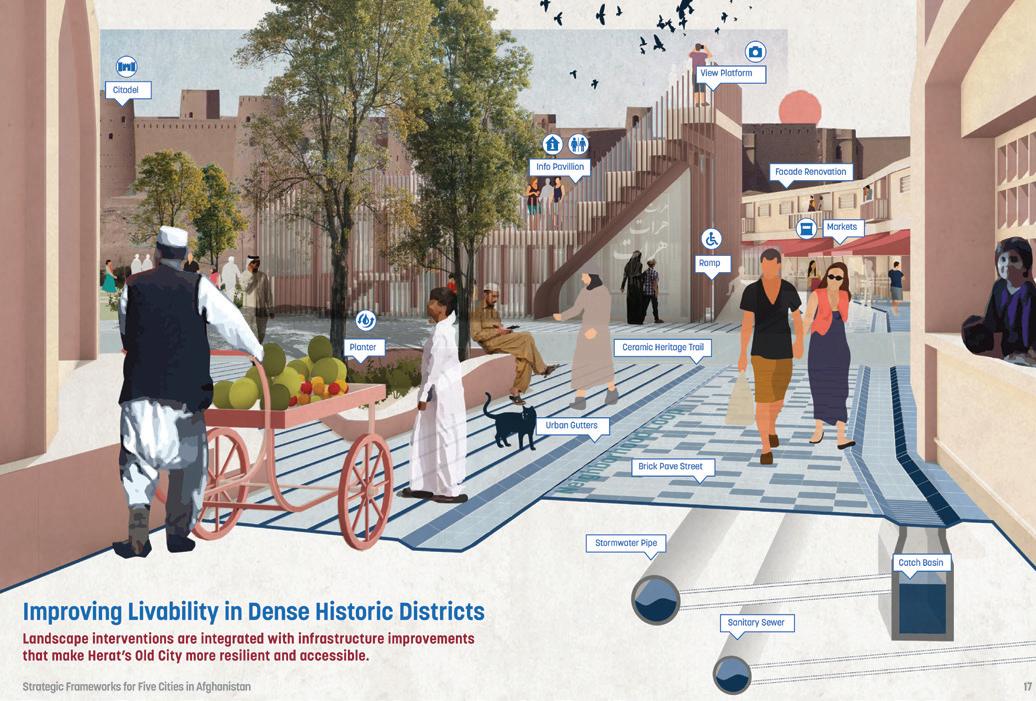

While at CMG, I had the honor of managing and designing the Willie ‘Woo Woo’ Wong Playground in Chinatown San Francisco, led by Willett Moss (CMG) and Cara Ruppert (SF Rec and Park). It is a playground and community space for Chinese immigrants and Chinese American kids. Ironically, as a Chinese American of immigrant parents, I felt simultaneously like this was my dream project and like an immediate outsider. How could I capture the Chinese American diaspora and reflect a shared experience in one physical design? In search of design conviction, I started volunteering with Abby Chen from the Chinese Culture Center (CCC) and Tan Chow from the Chinatown Community Development Center (CCDC). They gave me a connection to a greater community and empowered me to find the deeper stories beyond the stereotypes. They showed me that the meaning of “home” actually changes many times over our lifetimes and that equally powerful to “home” is to foster a sense of belonging. Through this project, I learned that meaningful design comes from deep listening and that the most rewarding process can happen when we genuinely integrate with the community and connect with the people we hope to serve.

Family brought me back to the east coast, and I met Mark Klopfer and Kaki Martin at Klopfer Martin Design Group (KMDG). And within my second conversation with Kaki, she said to me that our work means something to someone, always. They may not know our design intent, and we may never meet them, but the work means something for the everyday experience and is the context for life milestones. KMDG demonstrates this value commitment in all their projects. Through the work, we strive to create landscapes that ground the users to the present, while connecting the users to the history of place. It is a careful balance between placemaking and place-keeping.

Today I am a mid-level landscape architect at KMDG with teams of my own, and a new generation of interns and design staff. In my practice, and the practice I hope to share with my teams, I hope we carve out spaces that offer wonder and delight, regardless of the scale. These spaces should make people feel welcome and that they have a sense of belonging. Designing with a sense of home provides an intellectual framework for prioritizing community, collective memory, and individual attachment to place.

When we start new projects, or head on to a new phase, I try to take the time to find the larger picture with my team. We talk about the goals and what this project could mean for the people we serve. It is my hope that this serves as a constant motivator for myself and for my team. It is a reminder of why we do our work and is a “life vest” when projects dive deep into the vortex, whether it be permitting, detailing, or construction. And through the process, great design can be as much about building a home for others, as it is about building connection and belonging with each other.

Jennifer Ng is an Associate at Klopfer Martin Design Group in Boston.

Above, landscape architecture practice during the pandemic: daily morning check-ins with the full KMDG team

Jennifer Ng is an Associate at Klopfer Martin Design Group in Boston.

Above, landscape architecture practice during the pandemic: daily morning check-ins with the full KMDG team

32 BSLA

THOUGHTS ON HOME

Left: Norwell Street Park, Boston. Open House October 2021 to kick-off the design process. Photo courtesy of KMDG.

Middle row, left to right: Wille ‘Woo Woo’ Wong Playground – shortly before opening day February 2020; and Hunters Point Hillpoint Park - Taking a pause during a final field visit to celebrate our shared achievement. Photos courtesy of CMG Landscape Architecture.

Bottom row, left to right: Willie ‘Woo Woo’ Wong Playground, using virtual reality to demonstrate the community’s preferred design option; and RISE-UP: Game of Tides Community Event. Photos courtesy of CMG Landscape Architecture.

/ BSLA

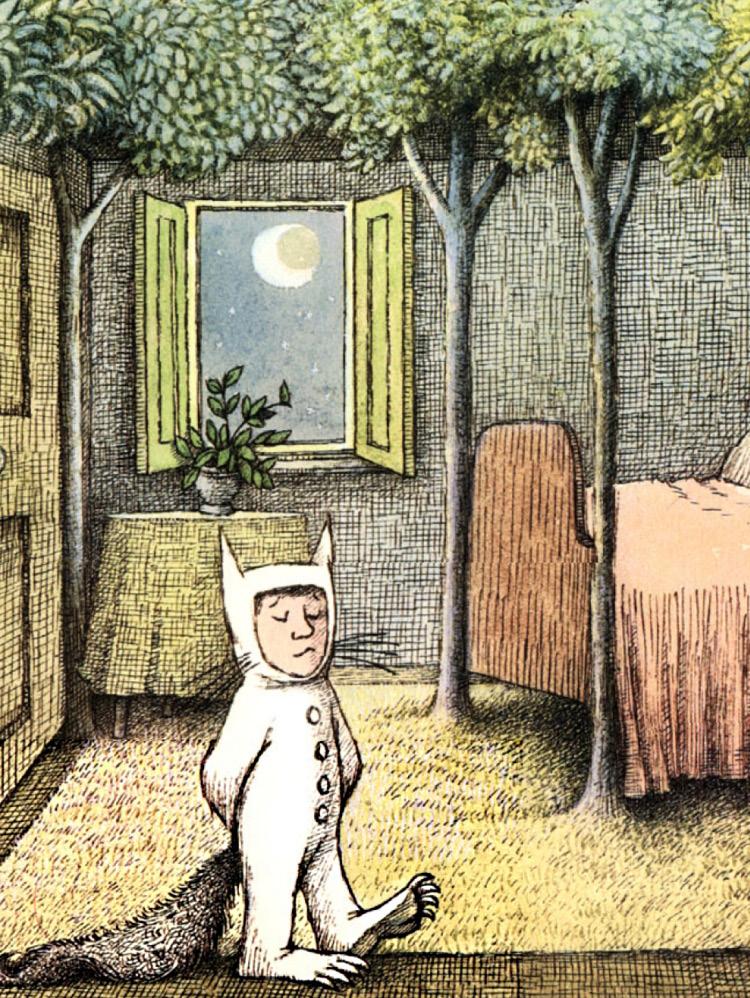

Detail from Where the Wild Things Are. Written and illustrated by Maurice Sendak, 1963.

Detail from Where the Wild Things Are. Written and illustrated by Maurice Sendak, 1963.

ELLEN MERRITT

THE NATURE OF DWELLING

Home is where the imagination dwells, where the senses are recollected and instinct resides. Like Max’s transformational bedroom it is Where the Wild Things Are or, as Anne Spirn so succinctly suggests when she states “Landscape was the original dwelling,” landscape is home. Shaped, measured, and embodied by our responses to environmental forces home for some, is the boundary of the skin; for others a shelter in which they are centered. Yet for others it is the unbounded space of the imagination through which we move with transparent ease.

The dissolution of the ceiling in Where the Wild Things Are opens Max’s room to the landscape imagination. As the ceiling and walls give way to a forested moonlit night, a feral surround of shaggy lawn, shrubby furniture, embedded trees, hazy clearings, and stars reveal a cosmic understory and a climate as rambunctious as Max in his wolf-skin suit. In the story, an abridged colonnade of trees unites earth and sky. The canopy grows toward the stars and the meaning of the bed as the genius loci of dreams, becomes more transparent. Immersed in the celestial sphere in a bed that is a boat Max sails away. His mood easily shifts and the scale of the room takes on cosmic proportions. The conception of the faded ceiling as a celestial dome in this story expresses the limitations and protections of his parent’s house. However, in his dreams his home is elsewhere.

A transparent sphere is one conception of the sky as a protective skin. As seen in the watery nature of snow globes turbulence renders the invisible, beyond-my-control forces visible. Consider the snow globe in Citizen Kane where the agitation is contained and the globe in hand registers how shaken or still we might be. Here, dreams of the childhood home are stirred in a sea of sugary dots that, depending on the color of the dome, toggle between a snowstorm and the movement of stars. The climate, like the wild beasts, is atmospherically immense. The motion liberates us and yet absorbs us in a desire to belong - to feel at home.

In a passage from Malicroix, about a house in a storm, the phenomenal nature of the event is conveyed as a fierce body in motion that ultimately proves resilient enough to tame the inhabitant’s fears. Henry Bosco writes,

“The house was fighting gallantly. At first it gave voice to its complaints; the most awful gusts were attacking it from every side at once, with evident hatred and such howls of rage that, at times, I trembled with fear…Everything swayed under the shock of this blow, but the flexible house stood up to the beast.

No doubt it was holding firmly to the soil…by means of the unbreakable roots from which its thin walls of mud-coated reeds and planks drew their supernatural strength…The already human being in which I sought shelter for my body yielded nothing to the storm. The house clung close to me, like a she-wolf…”

Max was sent to his room to dwell on his beastly nature. For us it was a viral pandemic that compelled us to move home outdoors where personal space became increasingly transparent and the outdoors increasingly personal. In response to the viral landscape, social distancing measures surfaced. Hoopskirt-like devices mediated boundaries six feet away from the body.

Outdoor yoga classes in Toronto dotted public spaces with domes of clear plastic resin like candy buttons on paper, while in Brooklyn’s Domino Park, socially distant circles regulated constellations of human occupation. In 2003, visitors to The Weather Project were brought together in a dematerialized habitat that highlighted their spirited responses. Noting that our perceptions fluctuate as readily as the weather, we see them raised to the sky in a reflection of the floor on the ceiling which reminds us that the universe in fact, is at our feet.

As Diane Ackerman observes in A Natural History of the Senses,

“The air is always vibrant and aglow, full of volatile gases, staggering spores, dust, viruses, fungi, and animals, all stirred by a skirling and relentless wind. There are active flyers like butterflies, birds, bats and insects, who ply the air roads; and here are passive flyers like autumn leaves, pollen, or milkweed pods, which just float. Beginning at the earth and stretching up in all directions, the sky is the thick twitching realm in which we live. When we say that our distant ancestors crawled out onto the land, we forget to add that they really moved from one ocean to another, from the upper fathoms of water to the deepest fathoms of air.”

How we make sense of the world is the essence home. It is instinctual, habit and habitat, the refuge and deep knowing of the constancy of change where the imagination runs wild.

Ellen Merritt, ASLA, is founder and principal of ECOLOGIES / Ellen Merritt Design, based in West Barnstable, Massachusetts.

35Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

THOUGHTS ON HOME / BSLA

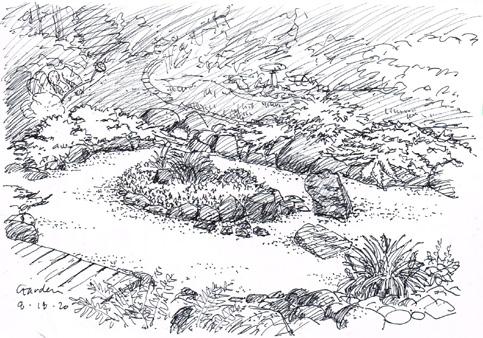

Morning frost in the garden.

RATLIFF

RATLIFF

QUARANTINE GARDENING

Being case number seven in the state of Vermont back in early March 2020, when the Coronavirus was still new, I found I had extra time on my hands. With a hefty two-week quarantine above the garage at my parents’ place and our landscape construction business on standby during the national lockdown, I had never felt a greater need to get my hands in the dirt.

I didn’t really appreciate how little time I spent at home until a global pandemic forced me to take stock. I had made dozens of plans for my parents’ garden over the years—ideas for new stonework, new beds—but work and time spent elsewhere kept most of these plans unrealized. Two weeks closed off from everything else helped kick start a few of these plans into action. Despite the pain of the pandemic for many, I was also given a remarkable opportunity to slow down and conduct the deep and thorough site analysis I always talk about. When else, but during a forced isolation period with a window overlooking the yard, could I (or would I) have observed and analyzed a space long enough to understand its needs, conditions, and quirks to such a degree?

I found I wasn’t alone in this heightened awareness of our outdoor spaces. There was—and still is—a collective movement to rediscover our own backyards. Some have spent more time in their vegetable garden; others turned to chickens and small-scale homesteading; and a people found ways to bring the outdoors in. The dramatic increase in demand for patios, outdoor kitchens, and general landscape improvements at home is a telling by-product of this pandemic. Clients who had been pushing off the big project were suddenly ready to go. On properties where lawn was king, homeowners were asking for larger plant lists, and ways to add more usable spaces into their yard. At a time when we were at our most insular, it became necessary to turn to our gardens for respite. And with the work-from-home lifestyle gaining traction this year, it made sense for people to create spaces that they actually wanted to spend time in. Thomas Church would likely be thrilled to see families blur the line between house and garden as we are right now, despite the significant decrease in kidney-shaped swimming pools.

In my own space I began working on a few distinct areas. First, I created a new vegetable garden behind the old hemlock hedge. Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ grasses now delineate organized rows of vegetables from wild, unmown meadow behind. I wasn’t much of a vegetable guy before the pandemic, and then I became the zucchini king.

Second came the entry garden with which I had become so well acquainted through my quarantine window. I chose to follow the lead of some of the naturalistic plant designers I admired by putting in my own matrix of perennials and grasses. While there are a host of styles that I enjoy and attempt to emulate in my clients’ gardens, there is something I find especially calming and safe about meadow-style landscapes. Thomas Rainier translates this innate feeling well in his book Planting in a Post Wild World, suggesting that humans have a primordial draw towards savannah-type landscapes, given how long we have evolved as a part of them over the millennia. Tall grasses were places of shelter. Despite being far removed from the dangers of yore, we are still hardwired for these experiences. I feel this intensely in a well-made natural garden, and I’ve set out to create my own version here.

Sitting in the living room now, writing this, I can look out the window at new ecosystems and garden spaces that weren’t there two years ago. Where the lawn would typically be blanketed by snow this time of year, there are now strong silhouettes of uncut perennial stalks hosting wintering birds. Cardinals and chickadees go back and forth from the hemlock hedge to the blackened echinacea seed heads. Dried grasses move with the wind and somehow fend off winter’s efforts to squash them.

Our space didn’t really change. The property isn’t any bigger; the windows are all where they always were. But I was given the time to look more closely than I did before. Every plant has moved and morphed, growing or giving into their neighbors in the dense perennial communities they form. Ever-changing, the beds are both a reminder of what 2020 meant to us, but also a promise that nothing is stagnant and things will be different soon. Things will be better soon.

37Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

GAVIN

THOUGHTS ON HOME / BSLA

38 BSLA

THOUGHTS

With a background in landscape construction and environmental humanities, Gavin Ratliff’s love for gardens grows out of long days in the dirt and the belief that plants have the power to make our lives better. With a degree in landscape architecture from Cornell University, Gavin is constantly pursuing his own environmental ethic in the office, in the mountains, and in the garden. All photos by Gavin.

Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

39

ON HOME / BSLA

40 BSLA

ESTELLO RAGANIT

HOME on the IRISH NORTHWEST BORDERLANDS

The series of photographs presented here emerged from ethnographic fieldwork conducted alongside Courtney Wittekind in Donemana, a small farming village in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland to understand how the borderlands in the Irish Northwest produce varying conceptions of “home.” The project asked: Are notions of “home” defined by political boundaries or are they altogether reinscribed by other socio-cultural parameters? Are the markers of home physical, or do they exist primarily in the imagination?

During the time of my fieldwork in Ireland and Northern Ireland in March 2019, Brexit and its impact on the IrelandUnited Kingdom land border appeared to be the largest threat to the Irish Northwest. It was an all-too-real possibility and fear that armed checkpoints would be reinstalled along the 499-km border, unearthing traumas that stemmed from the often violent political and nationalistic conflicts between Ireland and Northern Ireland in the late nineteenth century in a period known as “the Troubles.” This period of time was marked by militarized border crossings that were often sites of civil unrest; and though peace was achieved with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in April 1999, these zones along the border continue to serve as monuments of deep cultural significance and loss for citizens on both sides of the border.

To produce this collection of photographs, we distributed disposable cameras to volunteer members of the Donemana community and tasked them with capturing what “home” looks like to them. This exercise in engaging with the community allows us to, quite literally, see the landscape

through the eyes of its inhabitants. In compiling images taken by multiple members of the community, we receive a more complete understanding of their lives lived, a reminder that home, like landscapes, oscillate to fit the needs of those inhabiting them:

Home is picking your child after a work shift

Home is the neighborhood rugby pitch

Home is a packed cafe at the top of the hill

Home is the energy of a crowded stadium

Home is shuttling a windswept daughter to school

Home is the church

Home is the dappled sunlight

Home is the fields

This set of photos ultimately informed a regional-scale design and planning proposal for the Irish Northwest that rejects hyper-development, instead focusing on embracing and preserving a lifestyle of slowness that stays true to the unique, pastoral charm captured in these stills.

This project was produced for the Harvard GSD course entitled, “Design Anthropology: Objects, Landscapes, and Cities,” taught by Professor Gareth Doherty and sponsored by Derry City and Strabane District Council and Donegal County Council.

Estello Raganit, Assoc. ASLA, is a landscape designer at Agency Landscape + Planning. A 2019 graduate of Harvard GSD, he was born in the Philippines, grew up in Las Vegas, and has lived in the northeast for the past decade.

41Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook

THOUGHTS ON HOME / BSLA

Photo of the gate to the Park, locked with barbed wire.

Photo of the gate to the Park, locked with barbed wire.

42 BSLA

NATURE MORTE

Most nights at 10 pm last spring, my mother and I dressed in black to break into a neighbourhood park. It was the Indian Covid surge of 2021, when our city was locked down and ambulances blared around the clock. Under strict orders to stop us from entering, security guards patrolled the streets. We timed their movements precisely. Our contraband was buckets of water. We surreptitiously hauled them over a fence taller than me. The casualties were our mud-encrusted clothes and mosquito-bitten skins. Our criminal act was desperately trying to keep over one hundred trees and shrubs alive.

A twisting saga that involved a pandemic, a vengeful neighbour, a coup, and a local municipal corporation culminated in my mother and I risking life, limb, and freedom for plants. The beginning of this story, like most other absurdities on this planet, predates my birth. It raises questions about public space, ownership, vegetation choices, community involvement in landscape design, and human stupidity.

I will begin with the house my family lives in. My grandparents bought the land my house sits on decades ago. A few years after their deaths, two branches of my family continue to live there. Multigenerational families living in ancestral homes are common in my culture.

Our neighbourhood is small and refreshingly verdant—a tiny hidden oasis in a city of 20 million. It started as a cooperative colony for refugees from Sindh (like my grandparents) and is now home to a fascinating array of characters whose lives provide fodder for absurdist fiction. It is a great place to call home. The house sits at the end of a block next to the contested patch of land (hereafter called “the Park”) in question.

When my grandparents bought the land, this patch of land was a dump yard. My grandmother, determined to deal with the eyesore, hired people to clear it out and turn it into a garden. She filled it with dozens of trees and flowers, particularly roses, transforming it into a park.

The municipal corporation of my city technically owned the land and was happy to have somebody else manage it. The

corporation signed a public-private partnership contract with my grandfather, granting him the right to maintain it in exchange for advertising rights that he never used. Soon after, the corporation’s employees locked the entrance from the main road, signed off on an official gate from inside my driveway, and handed over maintenance rights to my family.

This arrangement was a relief for the municipal corporation, which maintains thousands of parks around the city, helping it focus limited resources on larger public spaces. At the same time, it worked well for my grandparents because they could now look at flowers and greenery instead of a landfill.

And that is how we peacefully chugged along for decades until a neighbour (hereafter called “the President”) launched a coup on our neighbourhood’s Residents Welfare Association (RWA).

RWAs in my city are primarily responsible for organising neighbourhood parties and coordinating trash collection. In short, they are not ideal forums for chasing fame and power. Yet that did not deter our fearless leader as she forced her way into the RWA’s presidency. Buoyed by various illegalities and without a single vote from her subjects, she was widely ridiculed. Her response was to attack those who had opposed her pathetic power grab. My mother was unfortunately first on the list, and the Park was the perfect battlefield.

The President’s reasons for attacking the Park were twofold. First, she decided that my family no longer deserved to look upon a beautiful green space from our windows. Second, and more importantly, she and her allies found native trees and shrubs offensive to their aesthetics. Much like British colonisers a couple of centuries ago, they prefer waterguzzling, ecologically destructive lawns of imported grass over local fruiting and flowering trees. This ideology is particularly alarming in my city, which lacks groundwater, is in a drought, and consistently ranks among the world’s most polluted places. Unfortunately, there are few cures for ignorance and colonial hangovers.

43Boston Society of Landscape Architects Fieldbook SUPRIYA AMBWANI

THOUGHTS ON HOME / BSLA

After ensuring we were away, the President descended on the Park with an army of men equipped with shears and strong fists. They ripped out saplings and lopped off all the branches they could reach.

As we stood outside the Park in shock to assess the damage, a neighbour pointed out that she had never seen our house from that angle before—the dense foliage had previously rendered the house invisible from the street. Immediately, the sun began to scorch our balconies, driving up the house’s temperature by several degrees. For the next few weeks, the usual diversity of bird species that graced the Park dwindled to those that could thrive in reduced canopies—mostly crows and pigeons.

We railed against the destruction; the President and her minions countered by claiming that the overgrown garden was an eyesore. By making it easier for grass to grow (in the middle of a drought), they claimed to have done our neighbourhood an aesthetic service. Yet they destroyed a thriving ecosystem. Centuries ago, British colonizers ripped apart gardens, appalled by the unpruned trees and riots of colours and scents that filled the spaces. They yearned for lawns bordered by flowers that reminded them of Old Blighty, an aesthetic that appears to have taken root amongst my country’s urban middle and upper classes with little regard for climate and culture.

I recognise that landscapes evolve over time and must respond to changing conditions. However, I refused to allow the President to continue destroying the plants I had grown up with. After a fair amount of sleuthing and long conversations with lawyers, we found that she could get away with her actions because my family’s contract to manage the Park had expired with my grandfather’s death. It was an oversight that could be corrected with a simple application to transfer the Park’s management rights to my mother.

We prepared an application and submitted it to the municipal corporation; I was assured of final approval to adopt the Park within a week. Simultaneously, our elected city councillor enthusiastically signed off on our application.

The corporation rapidly dispatched a team to the Park to take inventory of its plant species, turning up an astonishing variety for such a small space: a testament to my mother’s tireless work.

Nonetheless, the President’s sheer perseverance and an explosion in Covid-19 cases helped her win the battle. As the number of patients infected with Covid-19 shot up in my city, straining hospital infrastructures and oxygen reserves, the corporation pivoted to saving lives instead of fighting illegitimate RWA Presidents.

My city entered a lockdown. Unlike in the rest of the world, where indoor places were shut but outdoor public spaces opened, my government closed parks to the public, refusing to allow the lockdown-weary population any respite from their homes (and grocery stores). In a dense city in which most people lack personal space, let alone private outdoor space, the lockdown seemed targeted at annihilating the mental health of those not privileged enough to have gardens on their property.

I have long been critical of this appalling policy, but we were forced to live with it for an inhumanely long time. Fortunately, many neighbourhoods chose to ignore this rule, leaving smaller parks open for residents as hospitals filled up with those who could not breathe. My neighbourhood also had a similar unspoken policy of keeping public parks open until our delightful new President assumed power.

Furious that my mother and I had ignored her wishes and continued tending to the plants, she made her team chain shut the gate from our driveway to the Park, topping it with barbed wire for good measure (while leaving every other park in the neighbourhood unlocked). The President had essentially signed the Park’s death warrant by blocking us from entering it. The Park had survived for so long only because my mother diverted some of our house’s limited daily water supply to the plants.

And that is how my mother and I ended up dressing in black, breaking into the locked Park every night for a month and a half. We could not let the plants die, even at the risk of criminal records. Sometimes it felt like the plants sensed our

44 BSLA

I struggle to justify how my idea of what the Park should look like is more valid than theirs.

Which community members can and should have a say in how their neighbourhood looks? How do these debates affect our profession’s celebration of public participation?

desperation to keep them alive: they responded by growing taller and stronger, reproducing more prolifically than usual, and helping make up for their fallen brethren. I watched the President pace furiously outside, trying to figure out why the plants were not dead.

When the lockdown was lifted, she refused to open the gate and ordered her team to repeat the earlier carnage. Many plants that had survived our clandestine visits succumbed to this latest assault, breaking our hearts even more.