URBANOASIS

Rewilding Obsolescence in Downtown Cincinnati

Libby Graef

Libby Graef

Growing up, conservatories, parks, and the woods behind my house were my favorite places to visit. Walking through these places I remember feeling rejuvenated by the greenery and immersion into nature. In urban environments, the opportunity to become fully immersed in nature is limited. There may not be a greenhouse to visit nearby, and optimal hiking trails may be hours away. Many cities have parks and greenspaces with flowers, grass, and a few trees, but fully escaping the urban landscape sensorially is impossible. The effects of not spending enough time in natural environments can manifest as increased stress and poor mental and emotional health. Residents of cities need opportunities to experience the earth’s beauty and restorative elements in a space that doesn’t require them to wander far from home.

By looking at biophilia’s benefits and how to blur the lines between interior and exterior, architecture and landscape, to create a space for immersion into nature in a familiar yet unexpected way, the environment becomes a thing to be experienced. The Earth is a work of art that engages all the senses. Capturing this notion and bringing the best of its elements into a human centered space to foster creativity and promote mental well-being is my goal. The deconstruction of the obsolete through rewilding entertains the idea of nature taking back what once was, occupying obsolete spaces that have been devoid of life for many years. The rewilding within the space can become a respite for city dwellers and allow them to experience the rejuvenation I feel, and hopefully shift their perspective on the need to protect our natural landscapes.

What would happen if nature were allowed to reinhabit urban spaces that no longer have purpose to humans?

QUESTIONS

How does rewilding affect spatial experiences and biophilic design for humans?

What is the future for obsolete places and how do we steward them while returning them to nature?

Can the line between architecture and landscape be blurred?

CATALYST Obsolescence

A primary catalyst in this project is the notion of obsolescence. In Cincinnati alone there are several examples of buildings and structures in disuse and disrepair because of their functions becoming obsolete. Factories, churches, hotels, and even a standpipe are places that once housed significant purposes and have been left to decay or stand preserved yet inaccessible to public use. For example, the Crosley Building was a warehouse manufacturing radios and other electronics beginning in the 1930s. Because the radio and other early technologies are obsolete, the building no longer has purpose and sits today vacated and crumbling. A different type of obsolescence in the city is the Brent Spence Bridge. The bridge is still in use yet functionally obsolete because it was not built to handle the amount of traffic required of it today.

Across the country there are many abandoned industrial buildings such as World War II era factories, grain elevators, and other manufacturing plants. Many of these were built for one purpose and built to last, which makes adaptation difficult when they no longer serve our needs. Andrew Winters looked at well-built structures such as concrete grain elevators that are costly to destroy and nearly impossible to adapt. Industrial facilities have sunken into obsolescence because of economical shifts and technological advances. Often, they have been torn down in favor of constructing high end residential communities, severing the nostalgic presence from the community, and removing all possibility of adaptation, (Winters 2019).

Industrial and manufacturing buildings are at a higher risk of obsolescence, and I would venture to say that infrastructure is at risk as well. Stefanos Antoniadis investigates the problem of waste stemming from architectural obsolescence and subsequent destruction. His journal article is focused on reuse of these sites and preservation. Antoniadis points out that buildings designated as “cathedral” or “basilica” or even “the Colosseum,” have “become a recognizable urban fixture that should by all means be preserved, (…) Therefore, even before deciding by means of an architectural project to tamper with a building in order to prolong its shelf-life, it is obvious that well-known and established artefacts such as the Basilica or the Cathedral will be less liable to become obsolete,” (Antoniadis 2020). Because of this mindset in society, we prevent obsolescence in buildings that hold meaning to us rather than stewarding bridges, factories, warehouses, and more. These spaces are all subject to falling out of use yet will likely be demolished and replaced rather than preserved and adapted.

What do we do with obsolete spaces? Historic landmarks such as the Crosley Building cannot be destroyed but allowing them to rot is doing the city and its people a disservice. Contested spaces such as the Brent Spence Bridge aren’t easy to navigate and are financially difficult to settle. Because abandoned places can become overgrown, it raises the question; what if we let the environment take it back? Instead of destroying what stands, there must be a way to adapt structures into landscapes that can grow and change based on the needs of its users and inhabitants.

CATALYST Rewilding

When imagining a city or any dense urban area, what typically comes to mind is many buildings made with combinations of concrete, glass, and steel. There are streets and bridges with many cars, construction sites, and the noises that accompany all of it. This environment is not one conducive to plant and animal life, nor is it beneficial to the health and overall mental or emotional well-being of humans. Studies have been done on the concept of rewilding, where elements of wilderness are restored at various scales to allow the regrowth of ecosystems with minimal interference. One way of doing this is by creating space to accommodate native animals with bird houses, beehives, bat boxes etc., or adding more greenspace and pollinator friendly plants to urban landscaping. In some cases, a keystone species is reintroduced to bring balance back to the ecosystem.

The natural environment, (or lack thereof in urban settings), informs the secondary catalyst: rewilding. While Cincinnati has several parks and greenspaces available to the public yearround, the urban core lacks significant exposures to nature on a large scale. Industrialization and growth of the city effectively removed much of the existing environment. Through the concept of rewilding, positive change can be made. According to Siân Moxon, rewilding the city would mitigate urban overheating, surface flooding, and poor air quality due to traffic and appliance use. Biodiversity is incredibly important to the health of the environment and human well-being, and as climate change progresses, the damage done to ecosystems will only continue to worsen. By creating space for nature to heal, urban Cincinnati can heal. Moxon notes that many cities in Britain have embraced domestic urban gardens to support wildlife diversity and regrowth despite their small size, (Moxon 2019). When looking at Cincinnati, obsolete spaces are the perfect place to give nature a second chance.

Often, abandoned places become overgrown and unmanageable after several years when nature stakes its claim. Unintentional “rewilding” in this way is common, but in order to allow humans space to interact with nature in a previously obsolete space, safety and intentionality must be prioritized. How can native flora and fauna be reintroduced in a way that celebrates their beauty, gives wildlife more space, and affords urban populations the opportunity to be immersed within it all? Intentional rewilding of the obsolete would engage not only nature but also the community, and curb waste linked to redevelopment of the space.

As a catalyst, I chose to look at rewilding because of the success it can have when paired with obsolescence. Rewilding is also a beneficial practice for urban areas on many different scales. According to Donald C. Dearborn, “Often, cities do not contain large enough habitat blocks to sustain viable natural populations of most plants and animals, but small blocks can link with surrounding habitat on the city margins,” (Dearborn et al. 2010). He describes the importance of these blocks as steppingstones to bridge the gap between the environment and dense urban areas. If an obsolete building or structure housed one or more of these natural corridors, cities could potentially have a network of these rewilded spaces which would benefit humans and other living things.

The most hands off approach to rewilding is to completely let nature swallow up an obsolete space or building and reinvigorate life in its own way. While letting plants and animals take over an abandoned building and letting people immerse themselves into the space sounds like a good idea, without some human interference it could get out of control and become dangerous or be seen as an eyesore. The more curated form of greenspaces in cities involve parks and occasionally conservatories with massive tropical plants, both of which require frequent attention and maintenance to preserve the serenity and beauty that attracts people to them. There must be a balance in allowing nature to rewild in its own way and be attractive to urban dwellers as a safe immersive experience to reconnect with the environment. This approach requires intentionality, which moves into biophilic design.

FIELD OBSERVATION

Publicness: Devou Park

In a search for publicness, I sought a place that excludes few people, offers exposure to nature, and provides rest. Devou Park in Northern Kentucky is that place for me. Walking along the pathways I could feel the sun on my skin as it filtered through the treetops, hear the breeze in the leaves, and witness strangers enjoying a run or reading a book on a bench. All around me, greenery reached up to meet the bluest sky with little interruption by manmade structures. Many of the benches were made of flat stones stacked to a comfortable height, and picnic tables were painted green in an attempt to blend with the surroundings. I found a tree that was the perfect shape to lounge under and quietly observed everything around me. It was a very peaceful experience that allowed me to take a breath and pause from life’s busyness. Most people around me I believe were there for similar reasons, and that is what draws us all to parks from time to time.

Natural environments help us to destress and feel at peace because they are so drastically different from the inorganic structures and artificial light we spend our days in. At Devou, there are spaces that foster community such as the amphitheater and playground, as well as picnic tables and benches for 1-2 people. The vast program of the park in addition to its publicness allows for anyone and everyone to immerse their senses and find respite at most times of the year.

When collaging my experience, I wanted to focus on the spaces for respite within the park and how serenity is created by nature with human help. The proximity to an urban environment is highlighted, and the lattice structure symbolizes the possibility for natural growth among it. Blue and green are natural and calm colors duotoned to emphasize how I felt in the place.

FIELD OBSERVATION

Interior Urbanism: Krohn Conservatory

Unlike a fully outdoor city park, the Krohn Conservatory protects people and nature from the elements year-round. While walking through the indoor jungle, I noticed how much this interior space behaved like a park that could be found in the exterior. The rainforest environment, walkways paved in outdoor materials, and park benches gave the space an urban feel. The glass walls and ceiling make it a true interior but allow sunlight to filter through, further exuding an exterior environment. Upon entering the palm house, trees tower overhead as they reach for the ceiling, while smaller plants occupy the beds along the path.

The space presents itself as an overwhelming display of over 3500 species of flora and fauna, yet the intentionality with which each one was planted provides a feeling of calm and safety. The many textures, colors, sounds, and feel of the air within the room created a perfect condition for immersion. I was filled with awe and wonder at every turn of the winding path and felt at peace among nature so beautifully curated yet still uncontrollable. The wild nature and sometimes unmanageable growth of plants is still evident in such a controlled space. I walked around noticing vines that had latched onto the structure itself and begun to climb, and small shoots of new growth beneath the grates for drainage. There were even thin roots growing down from the ceiling creating a natural drape over the path. The idea of nature vs. control manifested itself in the conservatory in many ways.

For this collage, I chose a monochromatic approach to represent the tension between natural and manmade. In the conservatory, many vines climbed on the mullions of the glass structure as if seeking escape. The indoor garden is a human effort to contain nature’s beauty, but I challenged the notion by showing plants breaking the ceiling and billowing out.

FIELD OBSERVATION

Adaptive Reuse: MadTree Brewing

Going back to rewilding, an adaptive reuse project presents the framework to allow nature to reinhabit available space and connect the built environment with nature. MadTree Brewing in Cincinnati, Ohio took an existing airplane hangar adjacent to a manufacturing facility and repurposed it as a brewery and taproom/beer garden respectively. The industrial materials of the existing facility are celebrated in a way that shows the layers of history within the space, while also giving identity to MadTree. The roof and two walls were removed on part of the factory to allow the space to become outdoor patio seating. Because one brick wall with window thresholds remains, the patio still has an interior quality while being completely open to the elements. The string lighting hanging from the old structure gives the massive space a more human and intimate scale, allowing a change in spatial dynamic from day to night.

On the interior part of the taproom, green walls and ferns suspended from the open ceiling are utilized in a way that adds color and life to a very industrial setting. The windows operate as garage doors and allow air and sunlight to flow through the interior while connecting occupants to the outdoors. Adaptive reuse allows the juxtaposition of old and new, and even presents opportunities to use nature as surface. Reusing a building benefits the natural environment as well because the structure already exists, and therefore fewer resources go to waste.

In each of these spaces where publicness, interior urbanism, and adaptive reuse are exemplified, nature has a strong presence. Various pathways and the biophilic principles of prospect, refuge, sensorial connections to nature, and the presence of water (Browning et al. 2014) created serenity and put my mind at ease. Being surrounded by nature formed a desire to live amongst it and reap the benefits such as reduced stress and mental fatigue, increased happiness, lowered blood pressure, better concentration, and improved attention span, (Satılmış et al. 2022). When designing this project, I would like to ensure occupants experience the benefits of biophilic design. It is also a goal of mine to transform an urban obsolete space into an environment for both architecture and landscape to symbiotically coexist.

In the final collage, I used tritone coloration to explore three elements. Historic, new, and nature collide to create a space that provides many uses and can be appreciated in various seasons. I wanted to question how nature can take back a structure as well as perfectly coexist with a manmade space.

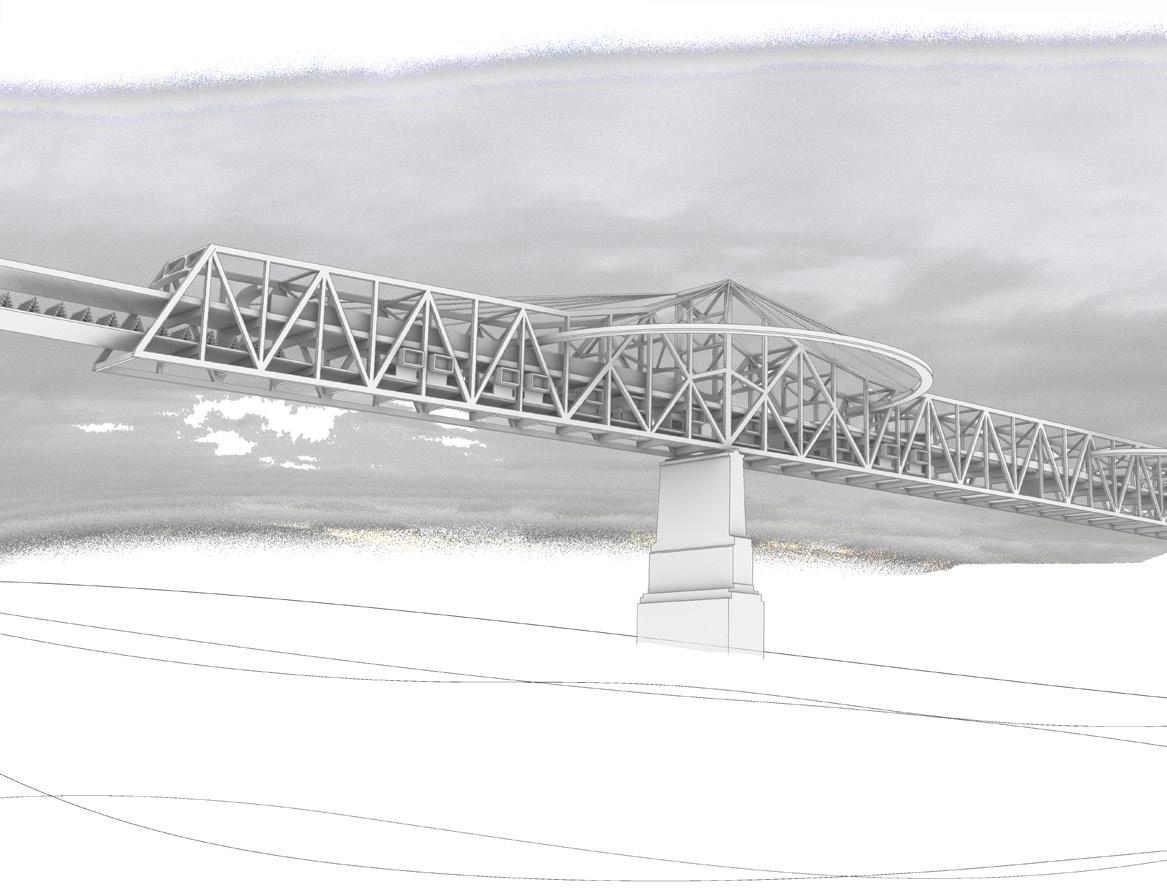

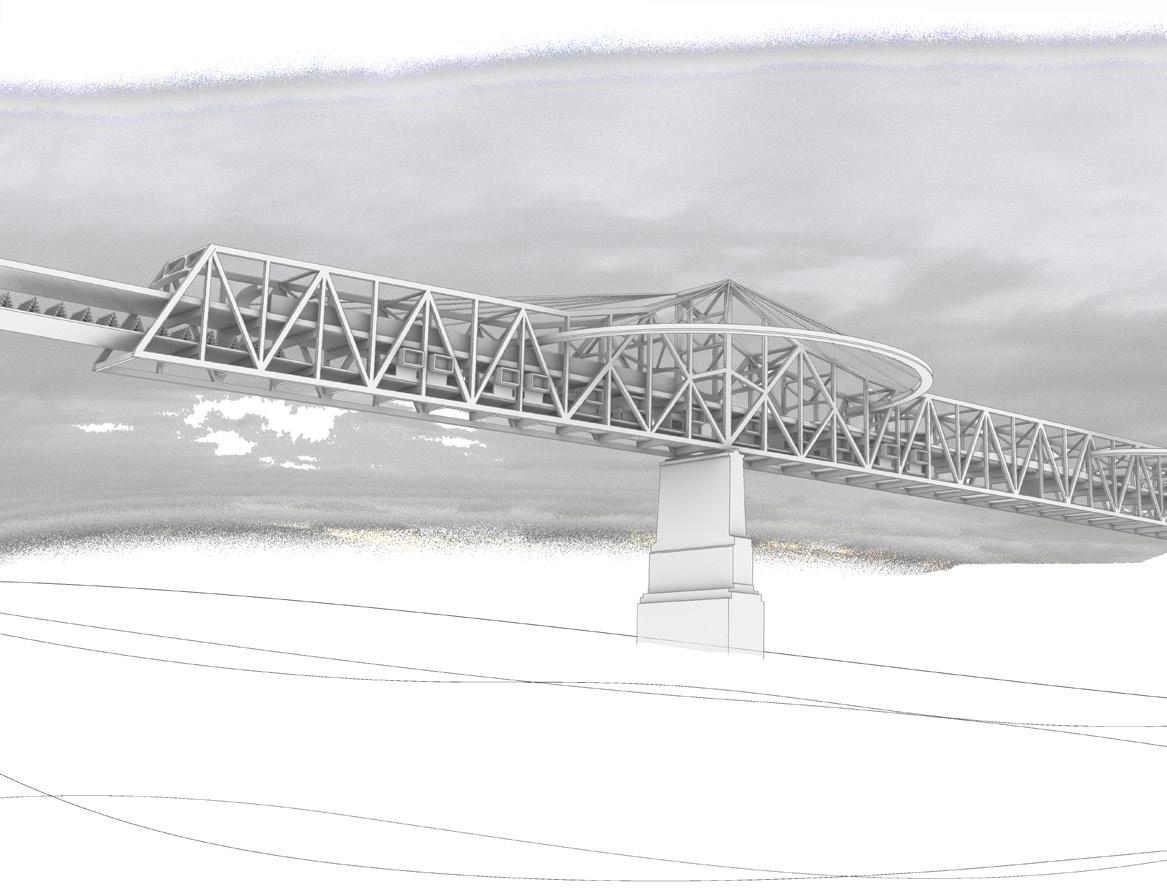

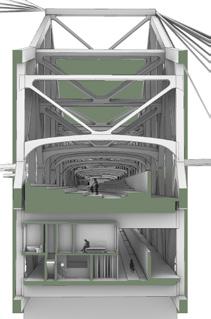

SITE Brent Spence Bridge

When thinking about sites for this project, obsolescence is a key influence. The Brent Spence Bridge, which connects Cincinnati, Ohio to Covington, Kentucky is still in use but is considered functionally obsolete by today’s capacity needs. The bridge opened in November of 1963 as a three-lane bridge meant to carry about 80,000 vehicles per day. It is a cantilever warren through truss bridge spanning 1,736.4 feet across. There are two traffic levels, one heading Northbound and one moving Southbound. Because of congestion, the emergency shoulders were removed to provide another lane. Today the bridge supports over 160,000 vehicles passing over it, and it is projected to increase each year. While the Ohio Department of Transportation deems the bridge safe structurally, the danger lies in its lack of emergency shoulders, narrow lanes, and overcrowding.

For years, talks of replacing the Brent Spence Bridge or building a companion bridge to reduce the highway bottleneck have occurred to no avail. What would happen if this bridge was given back to nature? It crosses the Ohio River, a major waterway and ecosystem. It could be integrated into this ecosystem and become a natural corridor for humans to interact with the environment, while supporting the needs of native flora and fauna. The intersection between the obsolete, multileveled steel structure and its natural surroundings creates opportunities for rewilding and intentional habitat restoration in an urban setting. The Brent Spence Bridge would be the landscape that an urban industrial Cincinnati is lacking and could be grounds for experimenting with deconstruction of the obsolete.

INITIAL IDEATION

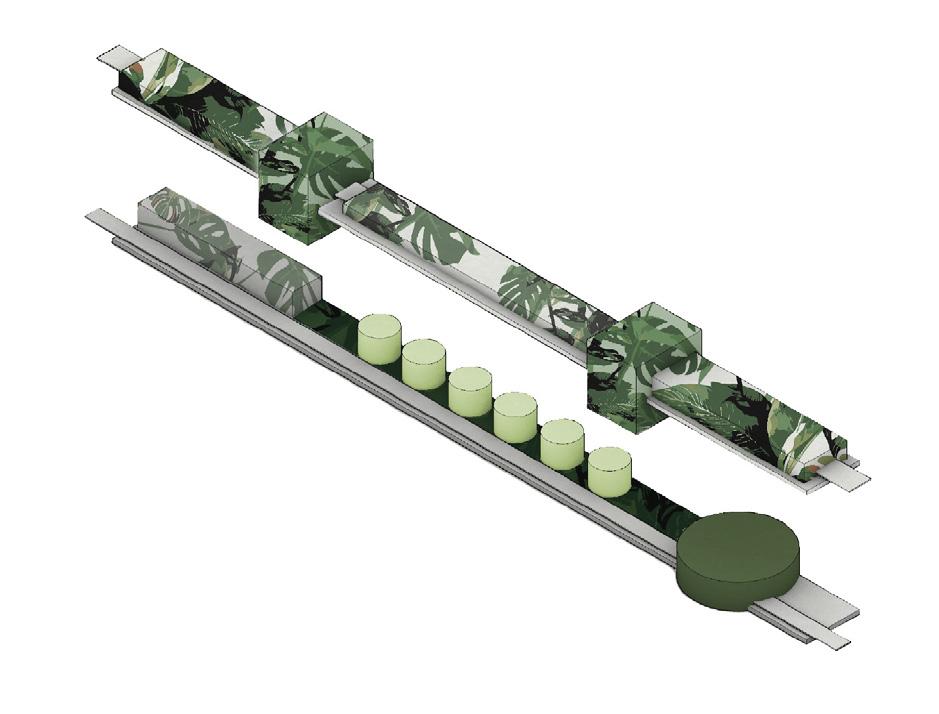

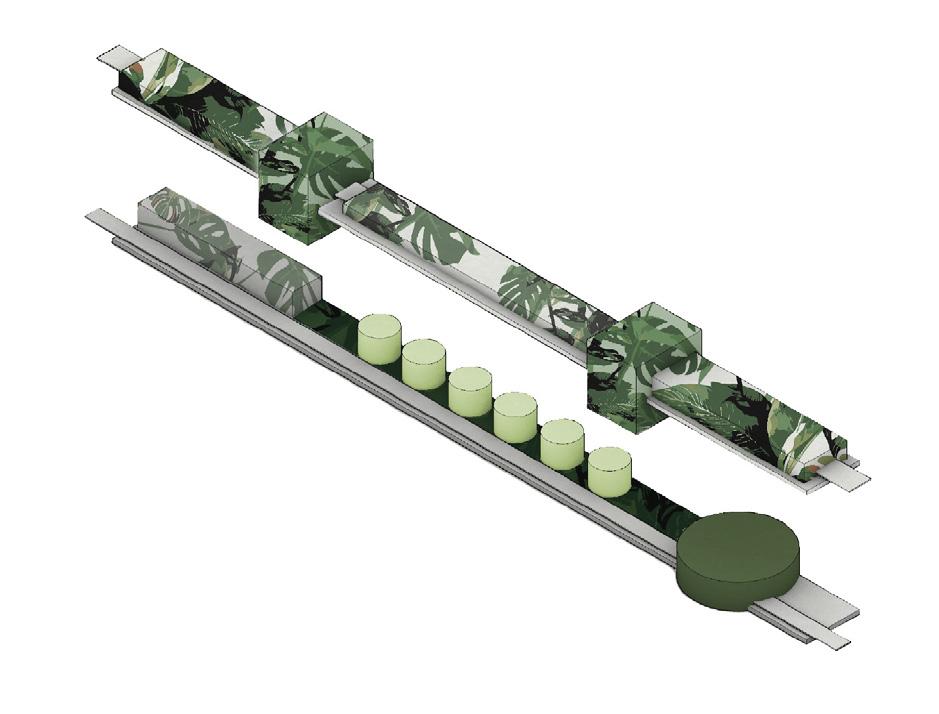

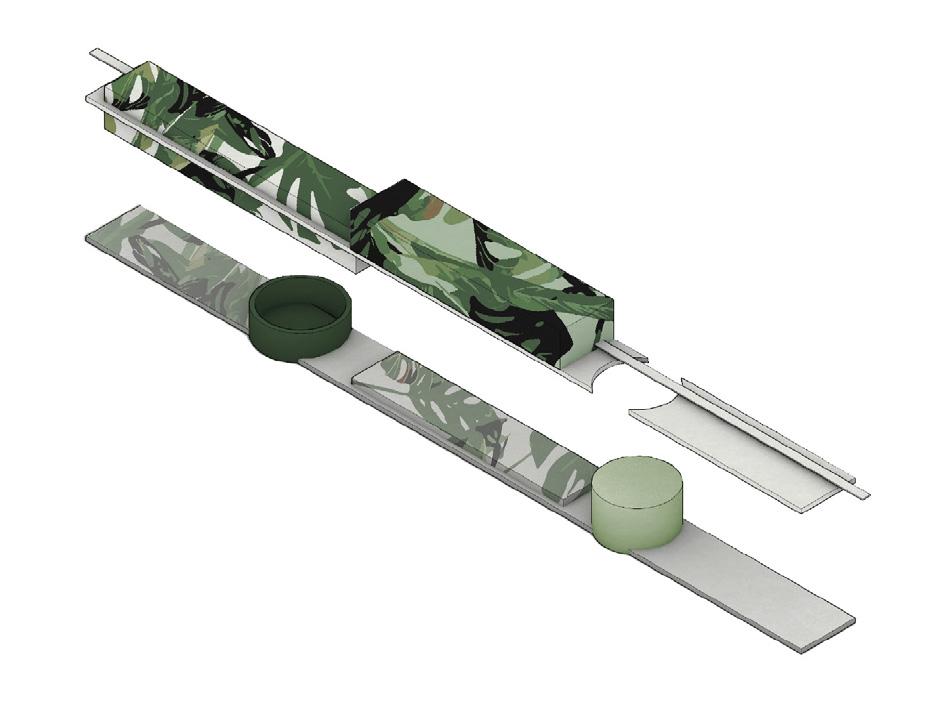

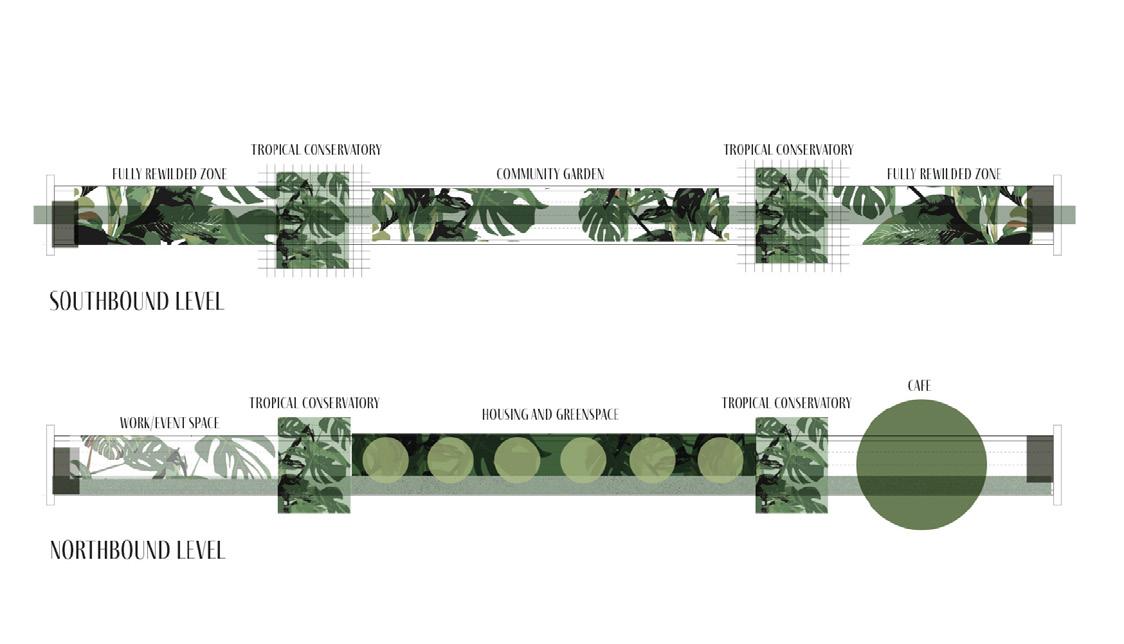

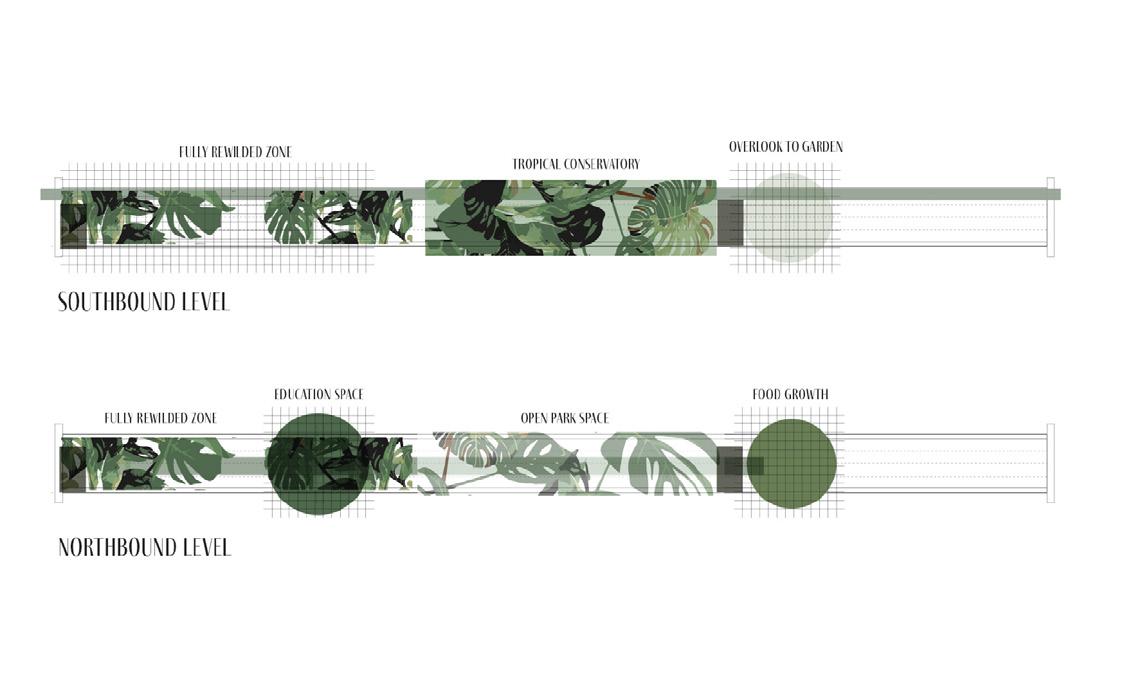

Program Diagrams

DESIGN CONCEPT

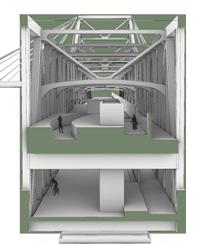

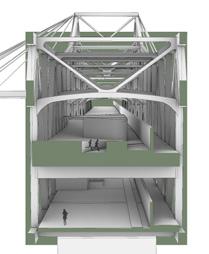

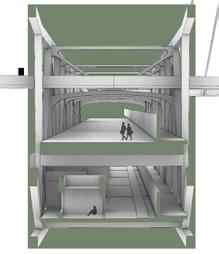

Rationale and Conclusion

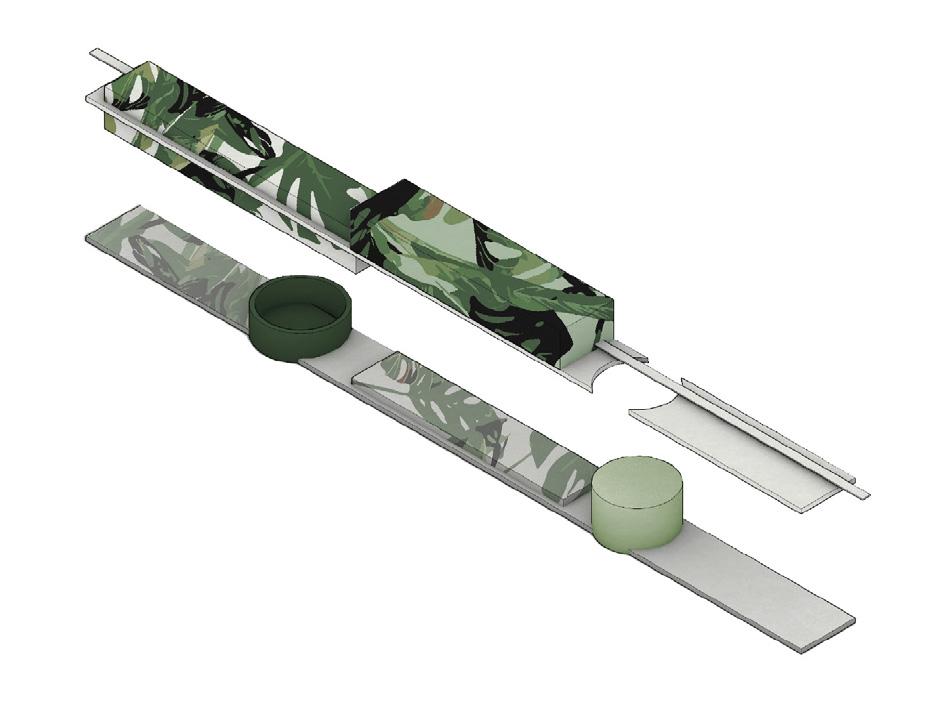

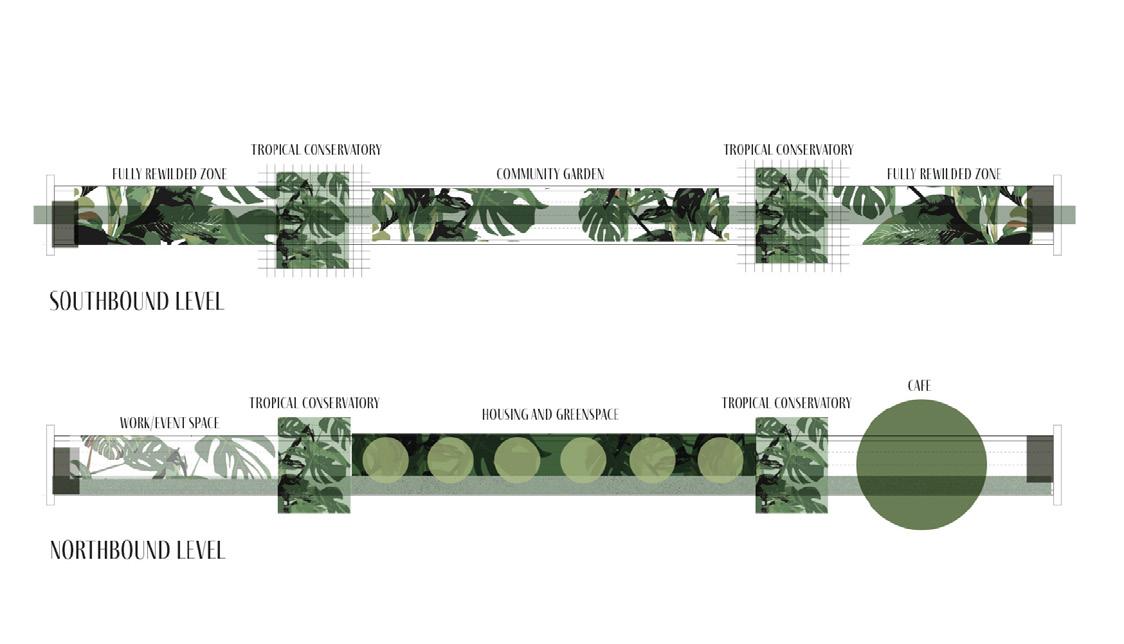

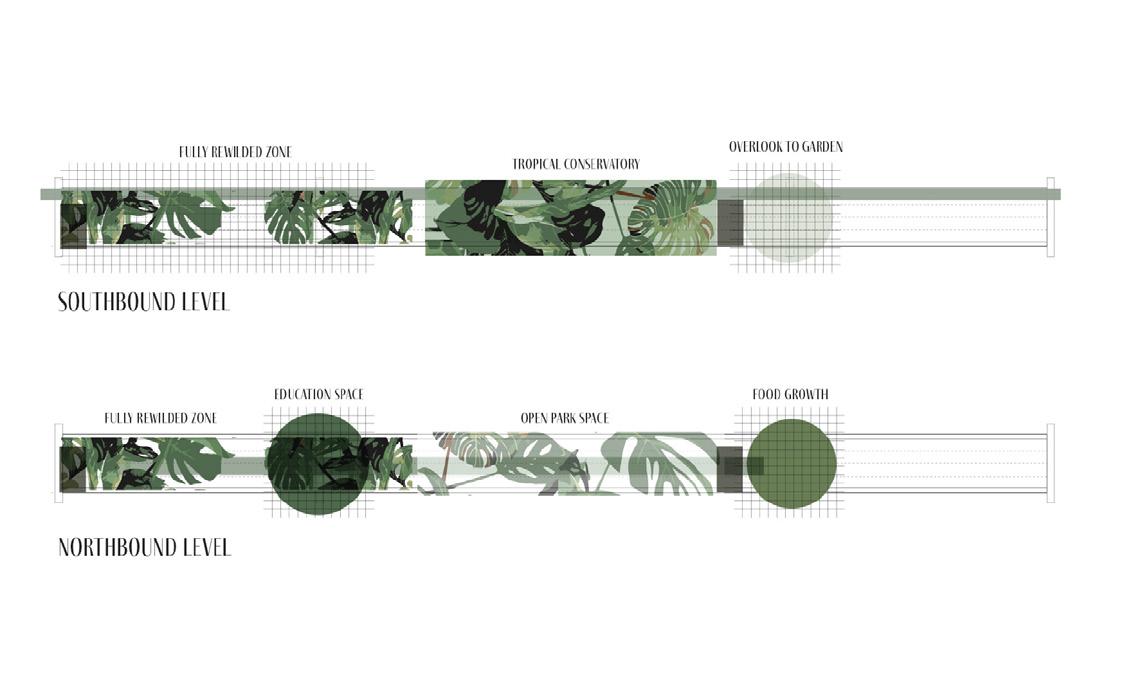

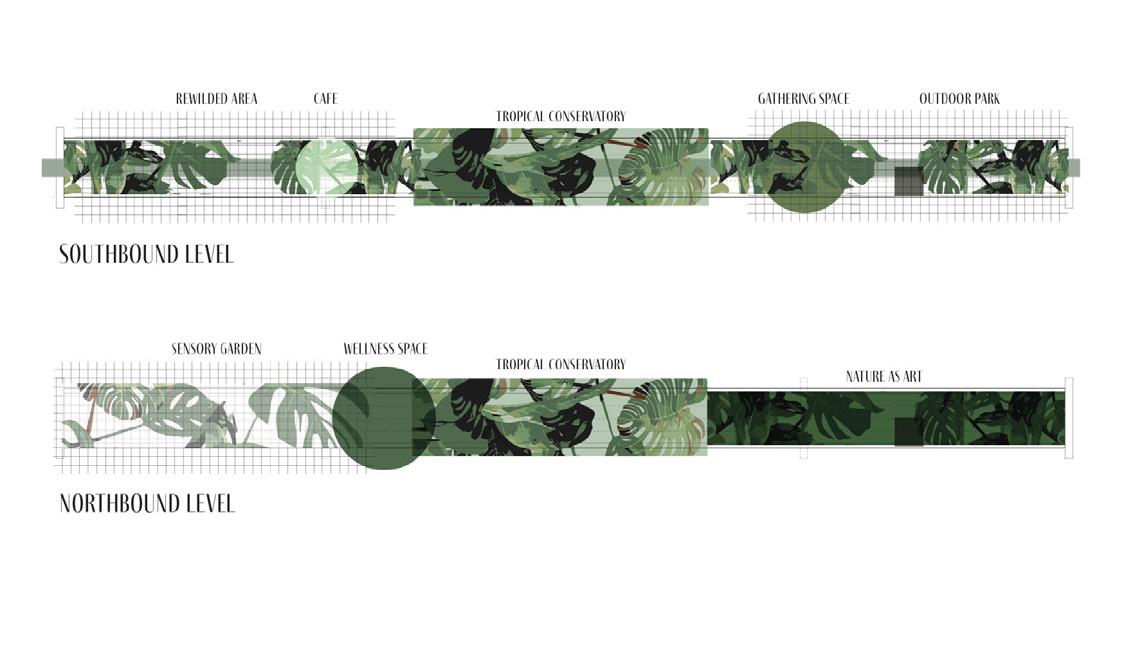

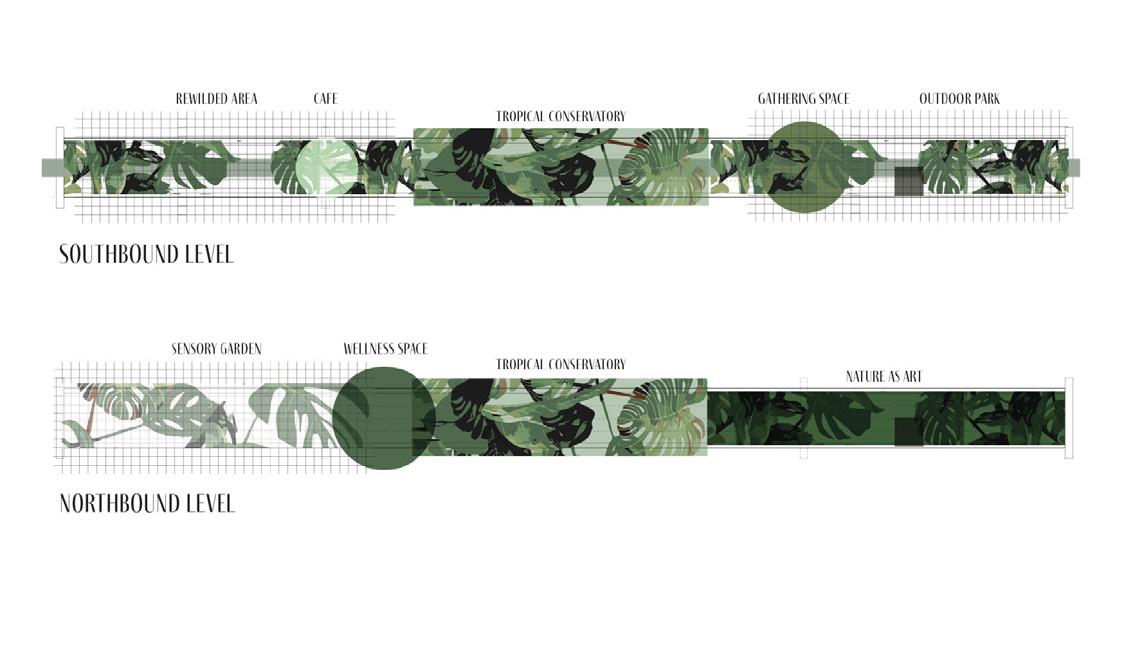

Using the Brent Spence Bridge as the site, I focused on catalysts of obsolescence and rewilding. My design adapts the bridge into a pedestrian and nature focused space that allows urban residents to inhabit and experience the structure in a surreal way. By connecting the Cincinnati streetcar and pedestrian pathways throughout the bridge, the space can be activated at all hours of the day and provide easy access to locations within. Programmatically, the space follows a progression. As occupants move through the bridge from North to South, natural installations begin to shift from heavily manicured with a high level of human influence to practically untouched, allowing native plants to freely grow and occupy the structures.

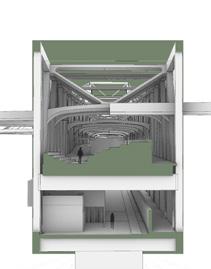

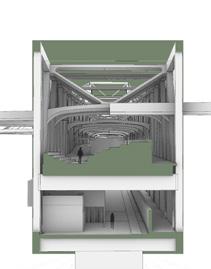

The upper level, formerly I-75 South, is entirely filled by three sections of greenspace. The first is a terraced pathway that serves to facilitate publicness and draw people into the space. Terraces have various species of Ohio trees intermixed with shrubs and florals growing along the stepped path. These steps allow occupants to lounge amongst nature in a heavily urban area while taking in views of downtown Cincinnati or the Ohio River beyond. As one is drawn southward, a tropical conservatory is set in the center of the site, encased between the two towers of the bridge.

Within the conservatory’s garden is the northbound streetcar stop. Whether someone has traversed the meandering paths or just stepped off the train, they can access a stair or elevator down to the lower level as well as restrooms located inside two tourist centers. The tourist centers are adjacent to the station and surrounded by tropical foliage. Each one is designated to the state it is nearest to, one for Ohio and one for Kentucky. Inside, there is an information desk similar to one that can be found at a national park visitor center, a seating area, literature on the Brent Spence Bridge and state history, and large panoramic windows offering views to the botanical garden.

Finally, as one exits the conservatory to the southernmost section, a path extends through trellises allowing plants to grow freely without human intervention. Shrubs and small trees begin to take back the bridge while vines reach for the trusses overhead, creating a surreal experience of walking through uninhibited growth. This space is a stark contrast to the urban surroundings, providing a home for small animals, birds, and insects in what formerly was dangerous and uninhabitable.

The lower level, formerly I-75 North, is more human centric while still providing opportunities for natural growth. The streetcar runs south on this level, stopping in the center just below the conservatory. Occupants will find a restaurant and bar with views of downtown Cincinnati. Adjacent to the restaurant is a coworking office space that includes administrative offices and leasing offices for the housing units. Housing units are prefabricated and stacked to provide a single bedroom space with views to the river and both Cincinnati and Covington. To address a lack of light within the lower level of the bridge, LED panels mimicking bright natural light are installed as “skylights” in most rooms. In addition to housing, two hydroponic farms are located on the northern and southernmost ends of the lower level, providing fresh produce to the restaurant and housing residents.

Biophilia, publicness, interior urbanism, and adaptive reuse informed the study of how obsolete infrastructure can be given back to nature and the community. Through the concept of rewilding, the Brent Spence Bridge transforms into a pedestrian focused space that blurs the line between structure and landscape. Terraced gardens, hydroponic farms, a tropical conservatory, and space for plants to grow uninhibited immerses occupants into nature. Increasingly untouched natural installations at both a human and utopian scale intermix with housing and community space, reflecting the resilience of a landscape to reclaim urban spaces and the innate human need to coexist with nature.

SITE CONTEXT DIAGRAM

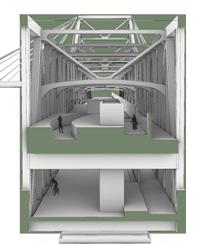

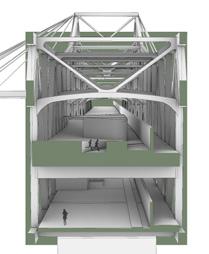

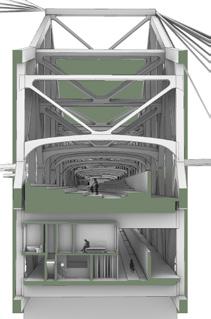

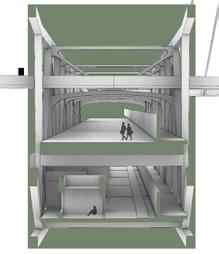

DIAGRAMMATIC AXON

PLANS

Suspended Pathway Main Level Lower Level

Sustainability Parks and Greenspaces in the Urban Core Existing and Proposed Streetcar Route Existing and Proposed Interstate Route and Pedestrian Ramps Upper Level Plan Lower Level Plan Section Section Section Section Section Section Section Section Existing Southbound Level Brent Spence Bridge from West Covington, KY View from below I-75 & I-71 Merging Existing Northbound Level Holiday Inn Covington Adjacency Longworth Hall Looking East to I-71 and Downtown Cincinnati View of northbound streetcar stop inside conservatory View of rewilding zone trellis pathway Interior view of seating and conservatory observation area inside tour booth Interior view of bedroom inside housing units Interior view of kitchen, dining, and living space inside housing units 20 50 Ohio tour booth callout plan Lower level southbound streetcar stop and restaurant plan callout Housing Unit Second Floor Housing Unit Main Floor 10 URBANOASIS Rewilding Obsolescence in Pursuit of Publicness in Downtown Cincinnati 20 50 10 OHIO RIVER KYOH View of terraced garden pathway Interior view of hydroponic farm View of tour booth info desk View of restaurant banquette seating

Libby Graef

Libby Graef