The Dardennes' guide to grit, silence and unexpected joy Blades beat fossils: Why Belgium is betting on wind

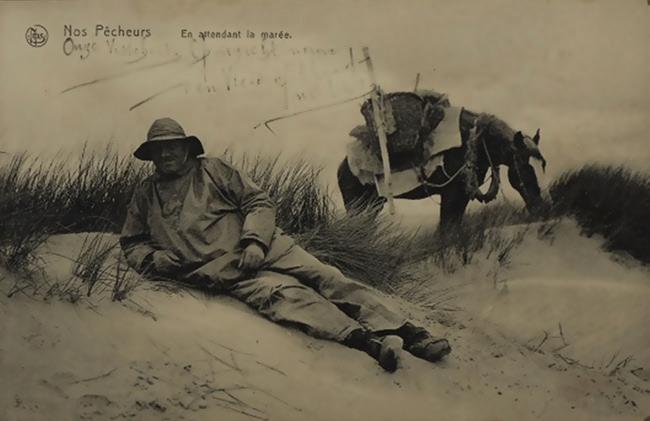

The North Sea horseback shrimp riders

The Dardennes' guide to grit, silence and unexpected joy Blades beat fossils: Why Belgium is betting on wind

The North Sea horseback shrimp riders

We’ve made our packaging lighter.

As part of our sustainability efforts we’ve reduced the weight of our packaging by more than 40%* .

*average weight per delivery since 2015. Visit aboutamazon.eu/sustainability

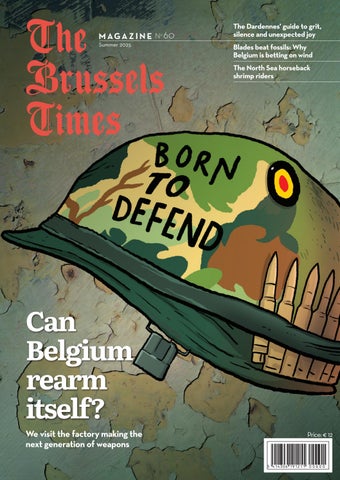

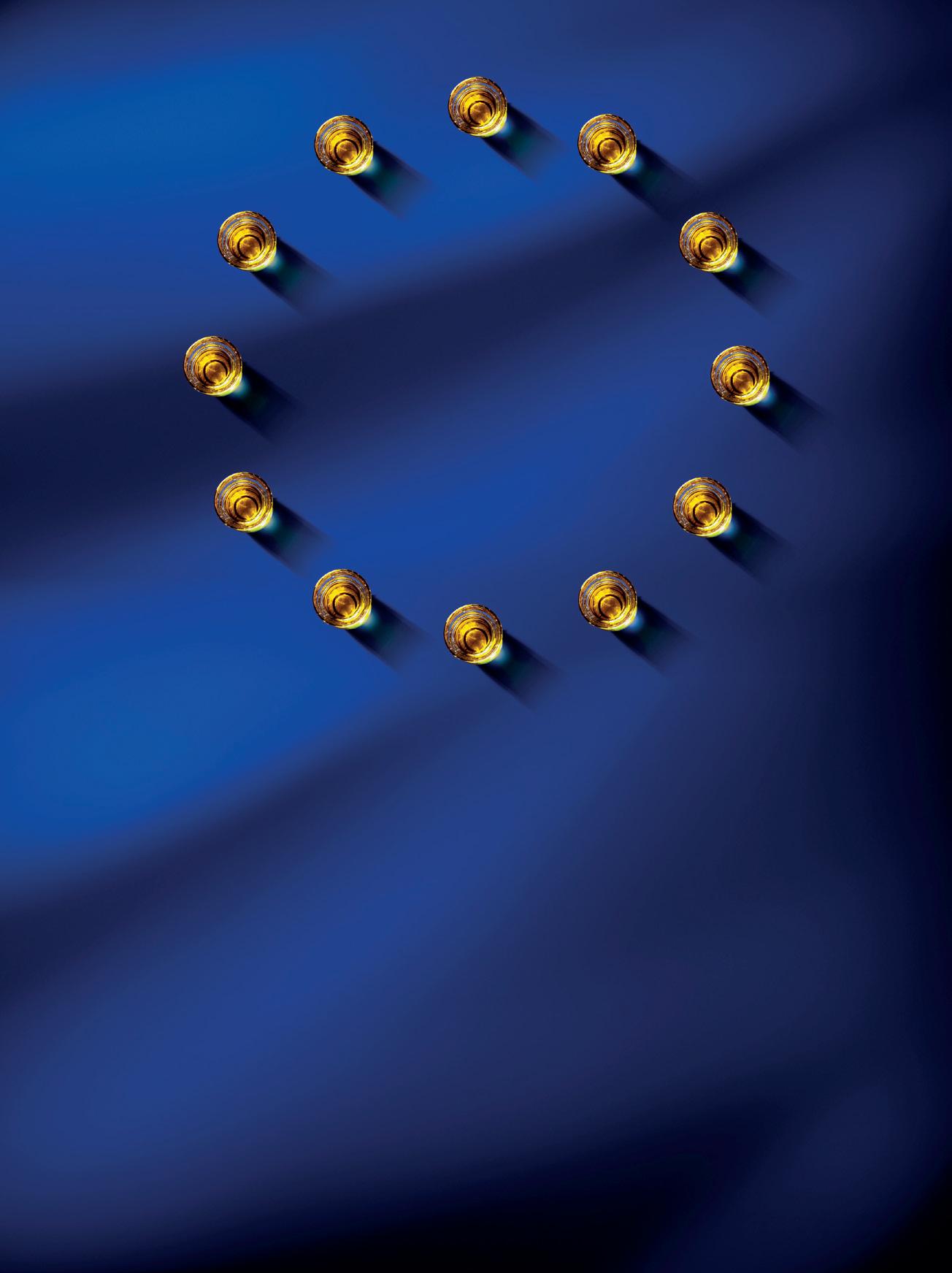

Belgium’s most paradoxical export isn’t beer, chocolate or surrealism. It’s firepower.

A trip to the FN Browning weapons plant in Herstal, the country’s quietly world-class arms factory, reveals more than just precision engineering. It’s a crash course in Europe’s rearmament angst. A continent that dreams of peace, dithers over policy and reluctantly reaches for a gun — made in Wallonia. FN’s assault rifles may be sleek, but Europe’s defence strategy is still a work in progress.

At FN, pacifism is welded to pragmatism. High ideals meet hard steel. The aim is to build up defences through deterrence. As Jon Eldridge reports from the workshops in Herstal, FN is bracing itself to meet the moment (cover by 2024 European Cartoon Award winner Lectrr).

We also have commentaries on the challenges Belgium faces to rebuild its defences after decades of decline, from retired Belgian army Lieutenant-General Marc Thys and Egmont fellow Wannes Verstraete

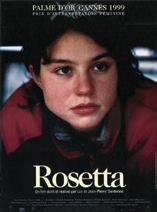

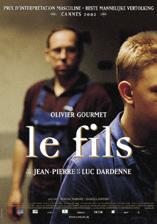

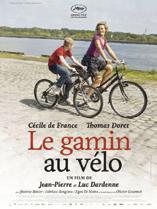

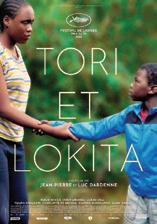

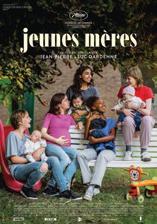

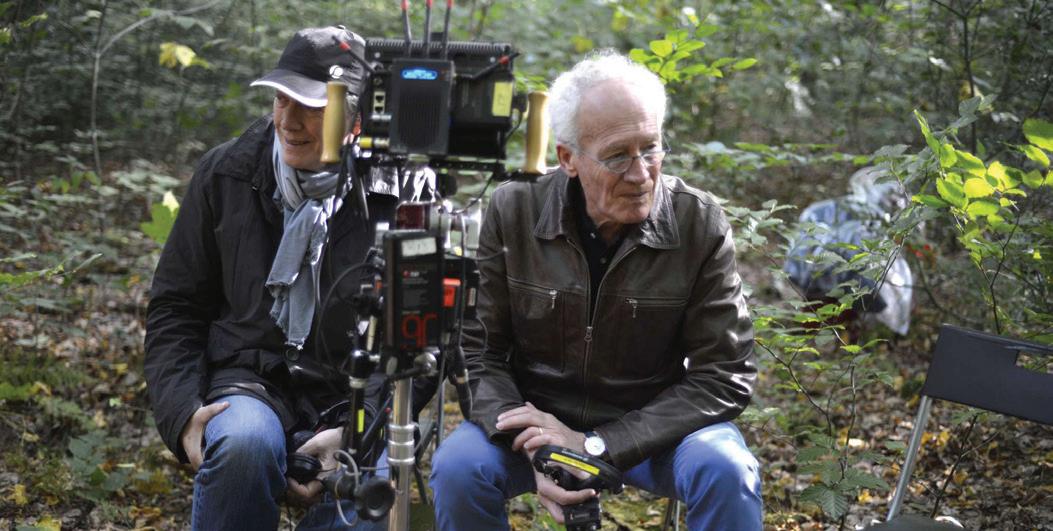

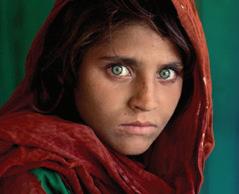

Staying in Liège, Dennis Abbott meets the Dardennes brothers, whose awardwinning movies, mostly set in the Seraing neighbourhood, have shone a light on gritty personal dramas.

Belgium’s ambitions for wind power are tangled in red tape, regional rivalries — and even Dutch accusations of meteorological theft, but as Dafydd Ab Iago reports, the country is slowly building its wind capabilities. Meanwhile, as technology catches up with snail mail, Derek Blyth wonders how the Belgian postal service can survive the modern era.

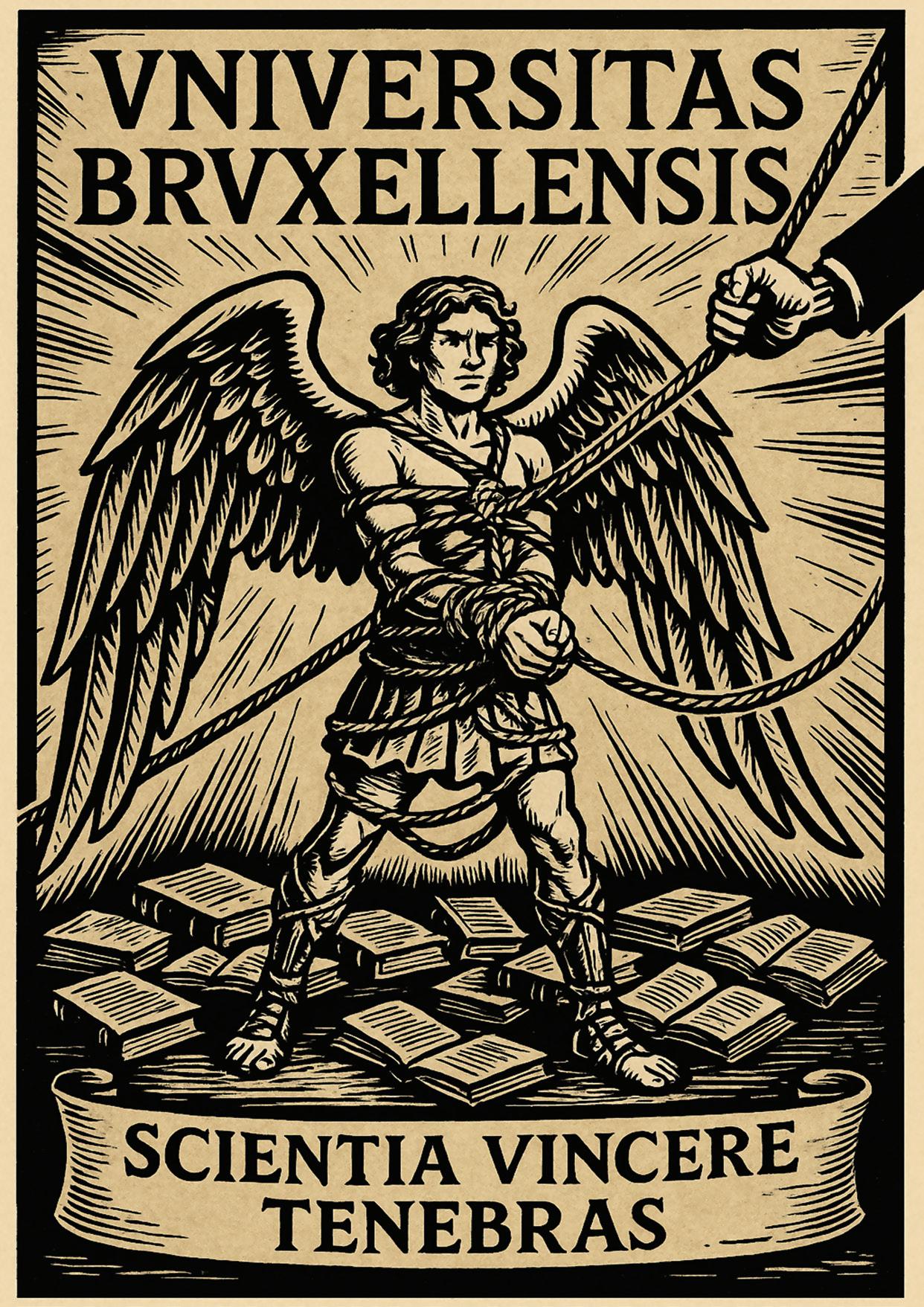

As universities in the US face unprecedented threats from the Trump administration, Philippe Van Parijs, a veteran of both Harvard and Leuven universities, looks at how Belgium has dealt with questions of academic freedom.

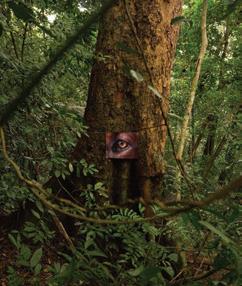

On the edge of the forest, the Tournay-Solvay Park in Boitsfort is a hidden gem in Brussels. David Labi ventures into the green idyll and admires the once-crumbling château at its heart, now restored as a research facility. David also previews the new galleries in the Art & History Museum in the Cinquantenaire that celebrate Art Nouveau and Art Deco.

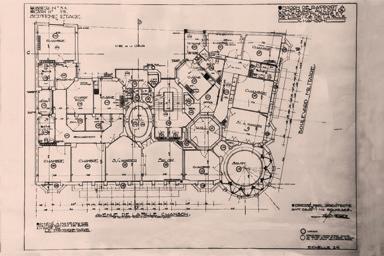

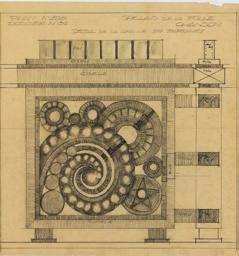

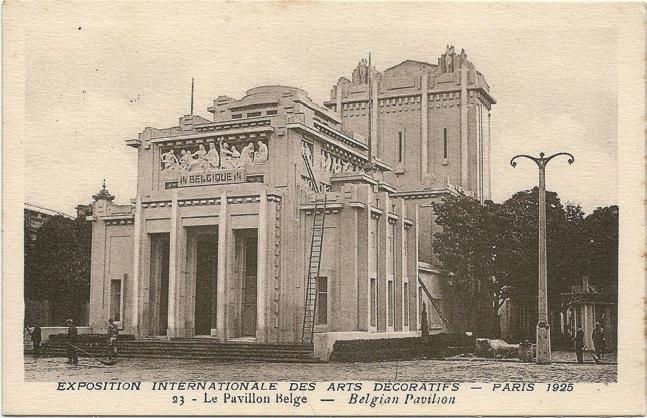

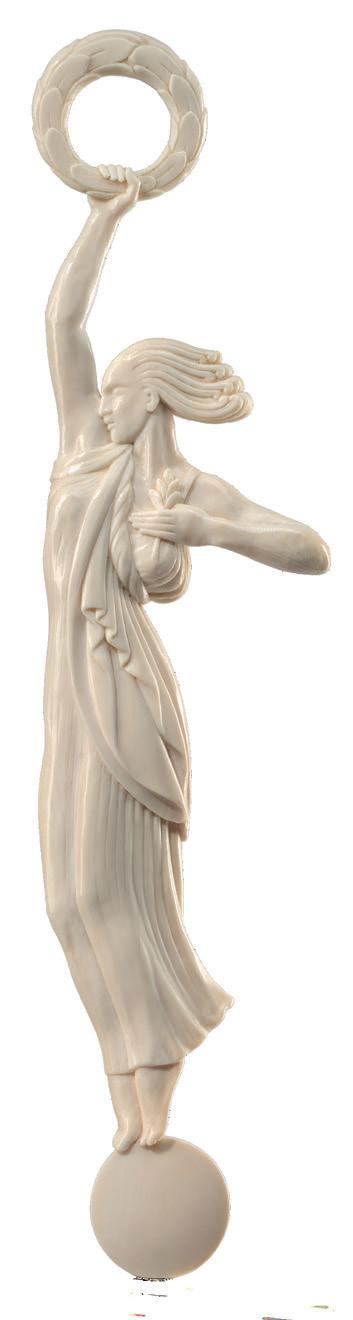

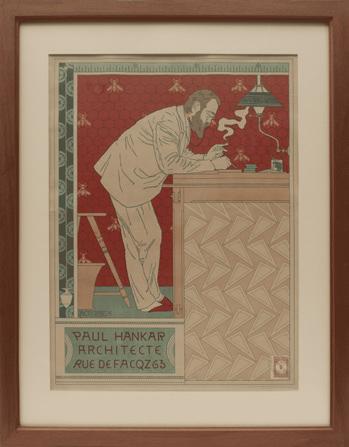

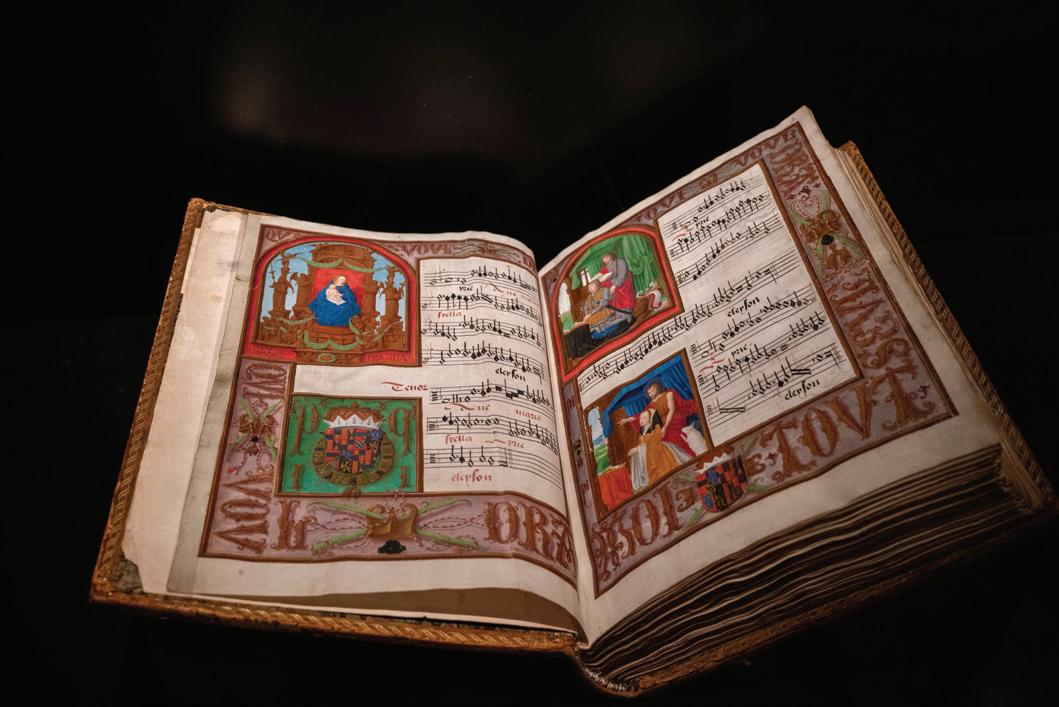

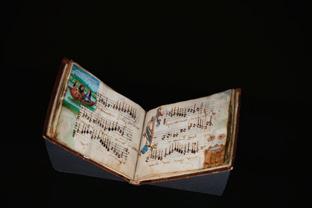

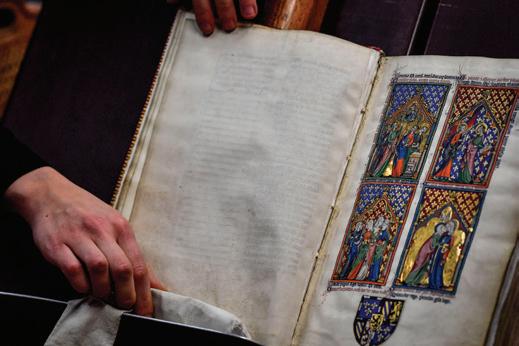

Antoine Courtens created some of the most memorable buildings in Brussels, and they are receiving renewed recognition in this centenary year of Art Deco as Frédéric Moreau writes. Simon Taylor, meanwhile, discovers how Renaissance polyphonists created new sounds as the Museum of the Royal Library of Belgium (KBR) reopens.

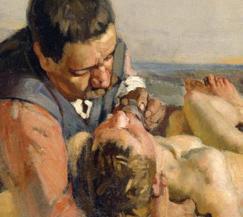

Angela Dansby takes a weekend break to Hasselt, which fancies itself as a fashion city along the Albert Canal. And she reports from the coast on the hallowed tradition of horseback shrimp fishermen (and fisherwomen). Also at the beach is photographer Jorge Gutierrez Lucena, who offers a perspective on the dunes, piers, hotels, monuments, amusement parks and forgotten campsites.

Having exhausted the entire Brussels tram network in his travel dispatches, Hugh Dow embarks on a new role as our Senior Cemetery Correspondent, beginning with the Laeken graveyard, and the Salu funerary workshop.

Breandán Kearney examines how Belgian brewers are meeting the challenge of becoming more sustainable; Hughes Belin tries out the Frank restaurant, SCOB tea, Kafei café and Nats Rawline cakes – and checks out the newly-opened Frietmuseum; while Kurt Karlsson highlights current and upcoming events worth checking out.

And finally, Geoff Meade returns to his old hunting ground, the Berlaymont, as the Eurocrat HQ opens its doors to the hoi polloi on Europe Day.

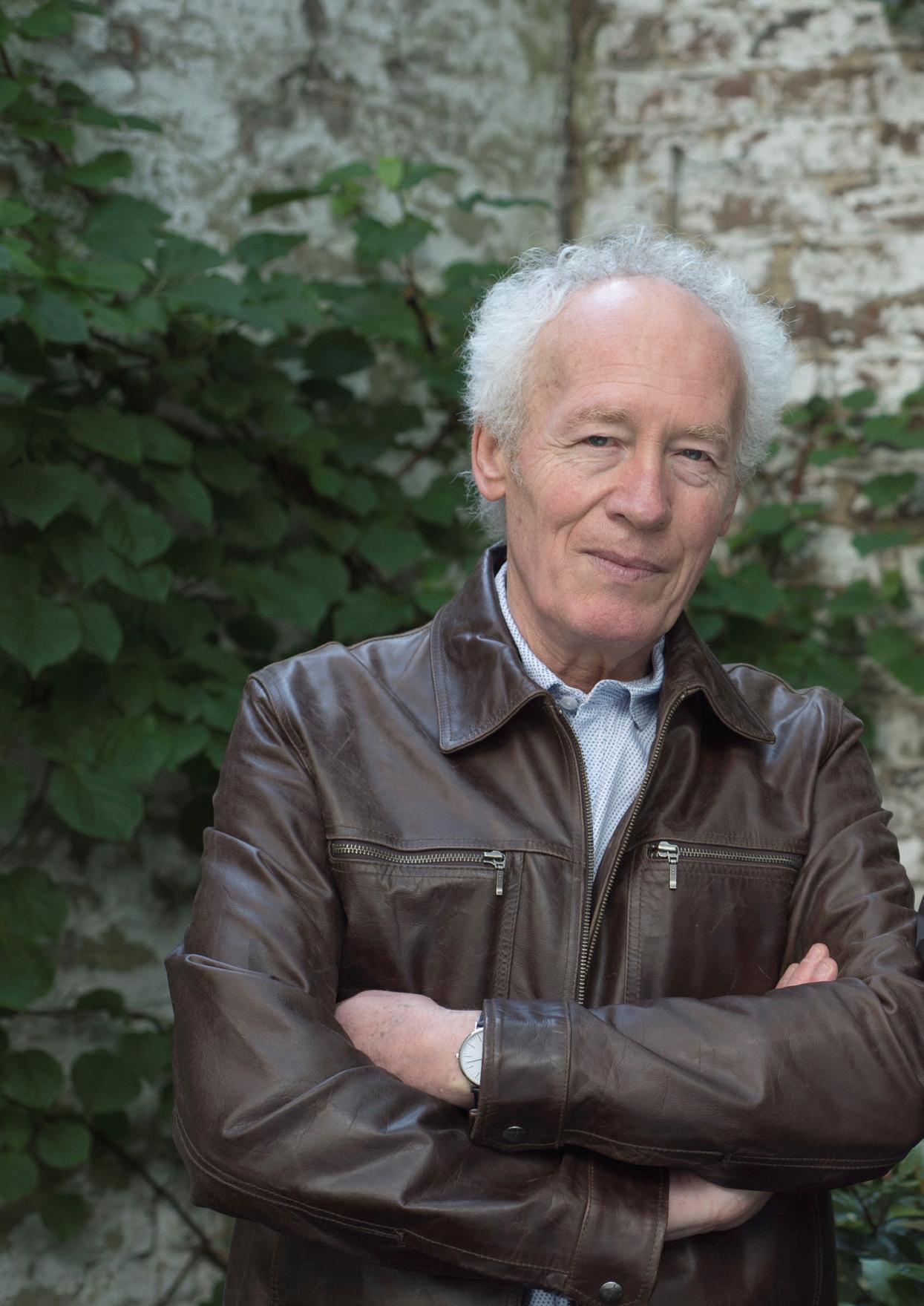

Leo Cendrowicz

Editor, The Brussels Times Magazine

Summer 2025

The Brussels Times Avenue Louise 54

1050 Brussels

+32 (0)2 893 00 67

info@brusselstimes.com

ISSN Number: 0772-1633

On the Cover Illustration by Lectrr

Editor Leo Cendrowicz

Publishers

Jonadav Apelblat

Omry Apelblat

Graphic Designer Marija Hajster

Contributors

Dafydd Ab Iago, Dennis Abbott, Hughes Belin, Derek Blyth, Angela Dansby, Hugh Dow, Jon Eldridge, Jorge Gutierrez Lucena, Kurt Karlsson, Breandán Kearney, David Labi, Lectrr, Geoff Meade, Frédéric Moreau, Simon Taylor, Marc Thys, Philippe Van Parijs, Wannes Verstraete

Commercial Partnerships Director

David Young

Advertising

Caroline Dierckx

Nataliya Moroz

Klaas Olbrechts

Ilham Rzayev

Gidon Tannenbaum

Please contact us on advertise@brusselstimes.com or +32 (0)2 893 00 67 for information about advertising opportunities.

Photo Credits

Lectrr: Cover, 144 Belga: 6-3, 31, 40-44, 131-132

Angela Dansby: 6, 80-82, 85-85, 111-116

Ars Mechanica: 18, 22-23

FN Browning: 6, 18-21, 21, 23

Bpost: 28

Leo Cendrowicz: 32, 76-79, 114, 119-123

Christine Plenus: 58-60, 64, 65

© Sofhie Legein - Municipality of Koksijde: 83

Jorge Gutierrez Lucena: 86-87

Admirable Facades/Jean Jacques EVRARD: 90-92, 94-95

Art & History Museum: 100-105

Royal Library of Belgium (KBR): 106-107

123RF: 124-125, 130

European Commission: 145-146

17

Trigger points: How FN Browning could lead Europe’s rearmament

Jon Eldridge

26 How many more wake-up calls do we need?

Wannes Verstraete

27 Why Belgium needs to rearm

Marc Thys

29 The last post: Can the Belgian postal service survive the digital age?

Derek Blyth

41 Why Belgium’s energy future is blowing in the wind

Dafydd Ab Iago

49 Academics under attack: When professors are pushed out

Philippe Van Parijs

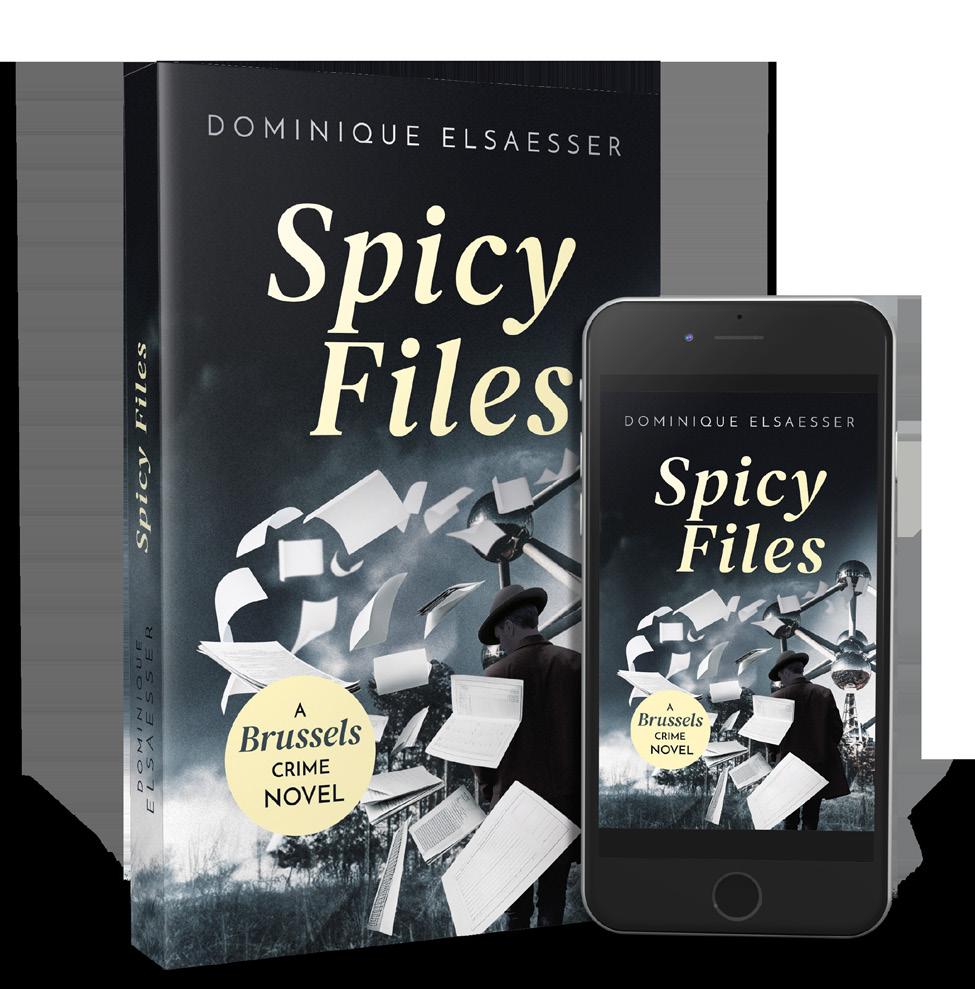

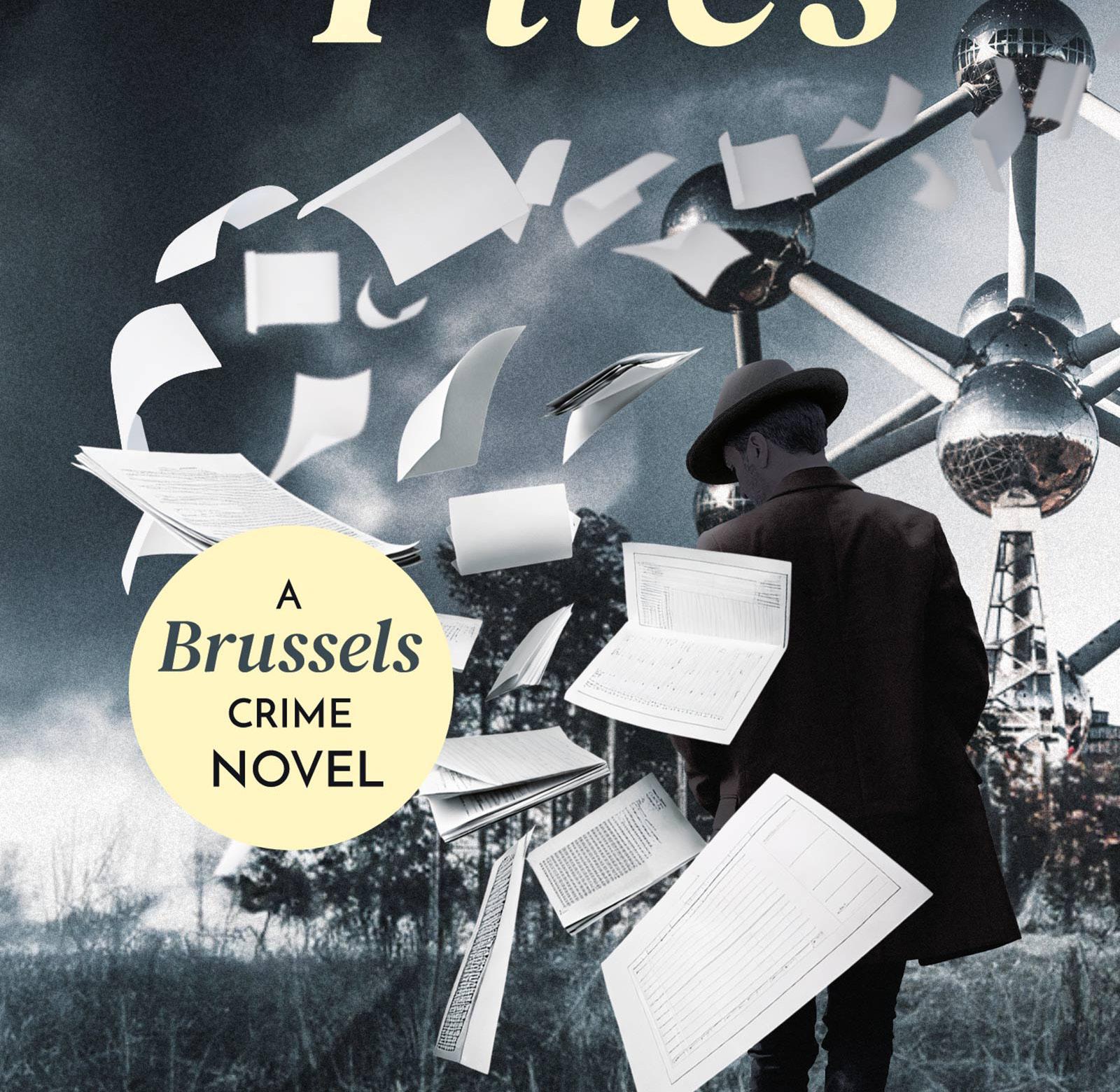

59 Roll camera, cue grit: The Dardennes keep it real

Dennis Abbott

71 The recycled city

David Labi

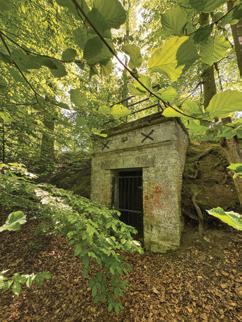

77 Park apart: The forgotten gardens of Tournay-Solvay

David Labi

81 Shrimp riders of the North Sea

Angela Dansby

86 Along the Belgian coastline

Jorge Gutierrez Lucena

91 The Art Deco disciple: Antoine Courtens reclaimed

Frédéric Moreau

101 Echoes in bronze and glass: Inside the lavish revival of Belgium’s Art Nouveau and Art Deco heritage

David Labi

106 A Golden Age reheard

Simon Taylor

111 Sass in Hasselt

Angela Dansby

119 Stone, silence and solstice light: The hidden histories of Laeken Cemetery

Hugh Dow

125 From grain to green: The sustainable shift in Belgian brewing

Breandán Kearney

130 Golden obsession: How Belgium built a culture around chips

Hughes Belin

134 Food & Drink

Hughes Belin

138 Art and events

Kurt Karlsson

144 Ursula, Moomins and me: My day in the Eurocrat funhouse

Geoff Meade

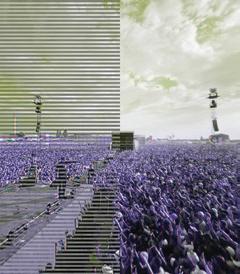

Royale Union Saint-Gilloise star Promise David celebrates with his teammates after securing the Jupiler Pro League title on the last day of the season. It was the first time Union had been Belgian champions since 1935. The club, whose Joseph Marien stadium is next door to Saint-Gilles, in Forest, only returned to the Belgian Pro League in 2021, after 48 years outside Belgium’s top tier. Next season, they will play the likes of Barcelona, Liverpool and Bayern Munich.

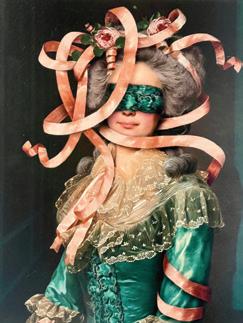

A riot of colour on legs, the Brussels Pride parade sashayed through the city with all the subtlety of a disco ball in a library. Sequins shimmered, flags fluttered and somewhere beneath a feather boa, someone was almost certainly quoting Cher. It’s part protest, part party, all pageantry — a jubilant reminder that LGBTQIA+ visibility never goes out of fashion, and that love, when properly accessorised, really does conquer all.

Some protests take to the streets; this one took to the cliffs. Dangling somewhere between defiance and vertigo, Jeff Roba clung to the rock face of the Citadel of Dinant with the tenacity of someone who really, really wants to make a point — and preferably not fall while doing it. It was a protest against a court ruling ordering him to demolish his illegally built hut in the Freyr forest near Dinant. After seven days on the cliff face, he climbed down, saying he was "fed up".

Amid growing recognition across Europe of the need for states to reinforce their defences and increase military spending, Jon Eldridge visits the Herstal headquarters of Belgian arms group FN Browning, which is celebrating its colourful history with an exhibition in Liège Jon Eldridge

A war is not something that’s very easy to deal with for a factory like ours. We don't have a second factory waiting for a war to start.

In the assembly section of the 13-hectare manufacturing site of FN Browning in Herstal, Liège province, the atmosphere is one of relaxed concentration. A handful of men, mostly wearing smart black T-shirts featuring the company logo, are putting together by hand the separately manufactured parts of the firm’s latest order. The completed firearms will then be tested for accuracy in an adjacent 50-metre corridor.

Automation has significantly slashed the size of the company’s workforce – from 12,000 in the 1980s to 1,500 today – but Henry de Harenne, head of communications, tells me that robots cannot replace these employees, who have around five to seven years of training. And unlike their co-workers in other noisier rooms of the factory, these skilled hands can enjoy the radio over the hubbub (although the incongruous strains of Billie Eilish’s latest hit bring a smile to this visitor’s face).

The employment of women becomes more apparent in the packaging area of the same hall. Indeed, the company does not shy away from acknowledging their role in its 136-year story.

In 1966, around 3,000 women at the factory, more than a third of the workforce, staged a 12-week strike demanding equal pay under the 1957 Treaty of Rome, the EU’s founding treaty.

Their action was both bold and unusual: led by rank-and-file women, not union leaders, and infused with the rhetoric of both economic justice and feminist awakening. Their chant – “À travail égal, salaire égal” – became a rallying cry, putting the issue of gender pay inequality on the national agenda.

The FN Herstal strike is featured in the group’s history display panels jotted around the factory, alongside other company landmarks, like the acquisition of Japan’s Miroku a year earlier and the establishment of the Browning Viana subsidiary in Portugal in 1973.

The group’s latest acquisition, Sofisport, was agreed last November and is expected to be completed in September. De Harenne points out that the purchase of the Paris-based softshell manufacturer, which has facilities in France, Italy and Spain, aligns with the recommendations of last year’s report on European competitiveness authored by former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi. “The Draghi report highlights the need for European companies to consolidate,” he says. “Since 1989, most European countries have not invested heavily in defence, and many have paid little attention to the origin of their equipment.”

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 reversed this downward trend in investment in Europe, although at the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine eight years later, some 80% of the ammunition of European armed forces was still produced outside the EU, according to the European Commission. The European defence sector had become reliant on exports, but that situation has changed. “Ten years ago, orders from European countries comprised just a minority of our production. Now they represent the overwhelming majority,” says de Harenne. Indeed, the assembly plant lists deliveries to Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

The company is steadily scaling up production to meet rising demand, but de Harenne emphasises that the group’s priority is to understand a country’s long-term approach to defence. He says the policies of FN Herstal’s clients – state defence departments, along with security forces – determine the size of the future market and not the outbreak of war.

“You do not build new production lines because of a war,” he says. “I hope, pretty much like you, that the war in Ukraine will stop tomorrow. But a war is not something that’s very easy to deal with for a factory like ours. We don't have a second factory waiting for a war to start. We have our people, our production tools, and for a defence company like ours, you can only invest if you have some commitment from your clients.”

The €1.3 billion, 20-year contract to supply the Belgian army that FN Herstal agreed in June of last year is a good example of the long-term commitment that the group is seeking, with FN Browning Group CEO Julien Compère saying it will give

them the visibility need to invest in new production lines (see separate box). The geopolitical uncertainty has not changed the company’s bottom line much: in June this year, it posted turnover of €934 million in 2024, up from €908 million in 2023. However, the Walloon region also said it would inject an extra €100 million into the group.

Amnesty International, among other NGOs, has criticised the sale of arms to countries with poor human rights records by FN Herstal, among other arms manufacturers in Wallo-

nia. Published last year, the latest Observatory of Walloon Arms report singled out the sale of machine guns to the Nigerian army despite allegations of attacks on the civilian population and called on the Walloon government to cancel the issue of certain export licences.

De Harenne says he respects that NGOs are “doing their jobs”, but he insists that it’s not the responsibility of arms manufacturers to determine the countries to which they can export. “We are a tool for the state, first, for their security; and we are also a tool for diplomacy – with countries that are your allies,” he says, although he acknowledges that it can happen

Hard target: FN’s plans to lead Europe’s defence renewal

The world has changed profoundly since FN Browning Group was set up in 1889 as Fabrique Nationale d'Armes de Guerre, but for its CEO, Julien Compère, the aim remains the same: to make dependable and innovative defence and security solutions for governments.

Compère the former head of the Liège University Hospital for eight years, including during the Covid-19 crisis, took the helm of the group in 2021, before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but as European countries were already boosting their defence budgets.

He points to contracts like FN’s recent 20-year deal with Belgium’s Ministry of Defence as key to the group’s growth. “This commitment gives us the visibility we need to invest in new production lines, which we are currently doing,” he says. “It will guarantee the strategic autonomy and security of supply of Belgium in the field of small arms and ammunition.

The 47-year-old who studied law at the University of Liège (ULiège) and later became chief of staff of Walloon Economy Minister Jean-Claude Marcourt, has led a more open approach to the media and politicians: before he arrived, the group did not have communications or government relations departments.

Compère does not shy from inevitable questions about the ethics of weapons manufacturing, insisting that FN always carries out due diligence analyses for each project – and notes that the Wallonia region is responsible for ensuring that export licences meet national, European and UN standards. “No firearms manufactured by our company leave Belgium without such an export licence,” he says. “It is then up to the states to comply with their obligations and international law.”

He also champions European defence programmes, citing projects supported by the European Defence Fund, including the MARTE (Main ARmoured Tank of Europe), E-CUAS (European system to

Company employees readily repeat the on-brand message that FN Herstal, as both a manufacturer of arms and ammunition, has been uniquely placed to drive innovation in the industry over the years.

Counter Unmanned Aerial Systems) and SAAT (Small Arms Ammunition Technologies), which FN coordinates with ministries in nine European countries. “These projects are good examples of how the EU can support cutting-edge innovation and bring European countries and industries closer together,” he says.

And while he is cautious about offering a political stance, he does suggest that Europe’s increasingly unstable security implies more coordination amongst the continent’s NATO members.

“The continent's peace and security are linked to its defence capabilities in the broadest sense, which requires a local, competitive and innovative defence industry,” he says. “There is a very clear awareness of this in Europe. The strategic autonomy and security of supply of European states is an essential element of their security. In other words, there can be no peace without security, no security without defence, and no defence without defence industries.”

In the company showroom, I’m handed one of the company’s latest cutting-edge developments: the ‘less lethal launcher’ FN 303 MK2, which has been designed for law enforcement uses such as crowd dispersal or individuals violently resisting arrest.

that the company chooses not to supply a certain country for other reasons.

The FN Browing group describes itself as one of the largest players in the small arms sector for military suppliers, with annual sales revenues of between €900 million and €1 billion. While its income may be a fraction of that earned by major companies such as the UK’s

Rearming Europe: An investment opportunity?

Belgium’s Defence Minister Theo Francken announced earlier this year that the federal Belgian government plans to increase investment in defence by €4bn this year to hit the current NATO spending target for member countries of 2% of national GDP.

The government had previously committed to raising the current level of 1.3% to this target by 2035. Francken says some of the extra money will go towards buying more ammunition, noting that NATO requires members to have a 30-day supply and not, in his words, a few days at best at present “before throwing stones”. The government has clearly been bounced into going further and faster by US President Donald Trump’s perceived lack of commitment to NATO and his administration’s wavering support for the defence of Ukraine against Russian aggression.

On a wider scale, the European Union has unveiled its ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030, which aims to mobilise up to €800 billion for defence investments by issuing bonds and loosening regulations. The plan includes a new financial instrument, Security Action for Europe (SAFE), for carrying out urgent and massive

BAE Systems, its importance to the regional economy should not be underestimated.

Two years ago, FN Herstal asked the University of Liège to carry out an analysis of its supply chain, recognising the need to ensure its security. The study highlighted the large number of local companies that have depended on FN for the past 80 to 90 years, noting that 90% of the

defence investment through common procurement. It will provide member states with up to €150 billion in loans backed by the EU budget.

Regardless of how member states such as Belgium decide to fund additional defence spending – whether through taxation or cuts to other departments – a significant question is raised: what will Europe’s new-found urgency to rearm mean for arms manufacturers including FN Browning?

The STOXX Europe Aerospace & Defence Index jumped 7.5% on March 3, its largest rise since 2020, with major players recording gains of around 15%. Although stocks plummeted in the week after President Trump’s so-called ‘reciprocal’ tariff announcements, they have continued to rise. It should be noted that FN Browning is 100% owned by the Walloon Region, and since shares are not publicly traded, it is not possible to gauge any increase in value of the group by following its share price.

The growing trend in investment, certainly before Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, has been sustainable finance – for example, investing in funds that align with environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria. ESG-oriented funds often avoid investing in the arms sector or apply strict criteria for doing so. However, some analysts argue that since defence companies play a role in securing peace and protecting democratic value, investing in the sector is therefore not incompatible with ESG principles.

Investing in defence companies, needless to say, is not without risks, and the market has a high degree of volatility. Since major contracts could be awarded to a rival firm to the one invested in, financial advisors commonly suggest spreading investment in the sector. European and global exchange traded funds focusing on defence and aerospace have been launched that allow investors easy access to a broad range of stocks. However, caution is advised. While share prices have risen steadily for the past couple of years, buoyed by the promise of future growth, a disappointing announcement, or any such unexpected intervention, could trigger a market correction.

company’s 1,200 suppliers are based in Belgium and neighbouring countries, with just 2% from non-European states. According to De Harenne, the industry’s supply chains are much more local than those of other sectors. He says that government investment in new production lines also benefits local companies that are not directly involved in the defence sector.

Company employees readily repeat the onbrand message that FN Herstal, as both a manufacturer of arms and ammunition, has been uniquely placed to drive innovation in the industry over the years. In fact, de Harenne enthuses that innovation is “in the company’s DNA”, pointing out that the group spends between 10% and 15% of its revenues on R&D activities, supporting more than 200 people. He says that such investment levels are more typical of an innovative start-up.

The company is proud of the role it has played in defining standard calibre cartridges for NATO. It should be remembered that allied forces could not share ammunition during World War II due to a lack of standardisation. The two most important calibres – the 7.62 x 51mm calibre adopted in 1954 and 5.56 x 45mm in 1980 – were developed at Herstal.

One of its most influential weapons, the 7.62 x 51mm calibre FN MAG machine gun, has been adopted by more than 90 countries since its launch in the 1950s. It was created as a General Purpose Machine Gun (GPMG) by an FN team headed by Belgian firearms designer Ernest Vervier. The resulting design, the Mitrailleuse À Gaz (gas-operated machine gun) with belt feed and quick-change barrel locks was even adopted by the US Army in the 1970s for the M1 Abrams tank and the M2 Bradley infantry Fighting Vehicle.

In 2011, the group acquired Finnish optoelectronics company Noptel, which specialises in laser range finders. The subsidiary is an integral part of the group’s strategy to remain ahead of the curve.

In the company showroom, I’m handed one of the company’s latest cutting-edge developments: the ‘less lethal launcher’ FN 303 MK2, which has been designed for law enforcement uses such as crowd dispersal or individuals violently resisting arrest. This is part of a range of weapons that aim to neutralise without causing severe or permanent injury whilst maintaining a safe standoff distance.

Kevin Criekemans, product and field promotion manager, tells me FN 303 MK2 uses compressed air rather than pyrotechnics and fires plastic projectiles that break up on impact with a force four times that of a standard paintball.

The model is a good example of how the company is applying artificial intelligence solutions, Criekemans says. “The gun will look for human features and create a safety area around

Top: One of FN’s ‘less lethal’ weapons. Below: Marvel’s Justin Hammer brandishing an FN gun. Above: The ‘less lethal’ projectiles

the head, blocking the system when it's pointing towards it,” he explains.

Many such interesting items – from the early Mauser rifles to the FN FAL rifle that Sir Winston Churchill advised the British Army to adopt in the 1950s – are currently on display to the public at the La Boverie, a grand exhibition space near the Liège-Guillemins railway station. The exhibition, Ars Mechanica – La Force d'innover/Driving innovation, was curated by the group’s foundation and traces the manufacturer’s long and prestigious history, featuring examples of its bicycles, motorcycles, cars, jet engines and even typewriters and milking machines (it runs until July 27).

The company’s capacity for invention brings to mind the quip of Sam Rockwell's weapons manufacturer, Justin Hammer, in Iron Man 2, as he wields an FN 2000: “They do make something better than waffles!”

In other words, there can be no peace without security, no security without defence, and no defence without defence industries.

From Mauser deals to mopeds and a Mormon gunsmith, the story of FN Browning is a very Belgian mix of precision engineering, foreign intrigue, and stubborn reinvention, says Jon Eldridge

In 1896, the German group Ludvig Loewe acquired a majority stake in FN, a transaction that kicked up a stir in the Belgian press. Le Soir, for example, questioned whether the company should be still called Fabrique Nationale.

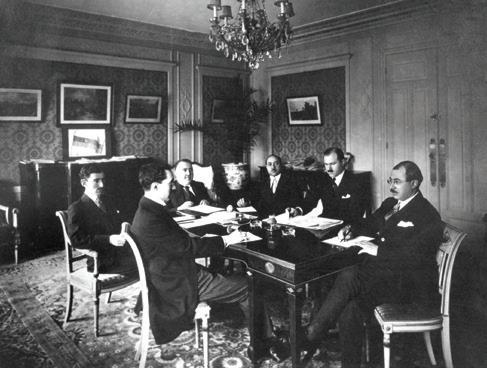

The FN Browning Group has its roots in a limited company incorporated by a group of leading arms manufacturers from the Liège region who decided to join forces in 1889 to help win orders. Seven of the industrialists behind the company, Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre had formed an earlier partnership, but it wasn’t until alliances with another syndicate that the group acquired enough heft to become a competitive player on the scene. The prize: the award of a contract to supply the Belgian army with 150,000 Mauser rifles after the state acquired the licence.

At this time, the development of a rifle capable of firing several shots in succession without reloading, the repeating rifle, was reaching maturity, and Belgium, along with neighbouring countries, was seeking to upgrade its firearms. High-precision parts were in demand that could be easily interchanged, providing a distinct advantage on the battlefield.

Advances in mechanisation were turning high-skilled craftsmen – working from home or in the suburbs on specific aspects of gun production – into manufacturing specialists. And industrialised Liège, with its coal mines, found-

ries, blast furnaces and steam engines, was at the heart of this development.

In 1890, FN bought six hectares of land in Herstal for 50,000 Belgian francs for the site of its first factory. But right from these early days, the company sought to diversify to ensure its long-term survival. A year later, FN snapped up manufacturing equipment to produce cartridges for the Mauser rifle, announcing that it was capable of “producing 25,000 war cartridges in 10 working hours”. Through a Russian contact, the company also secured an order to convert 400,000 rifles for the Russian army.

In 1896, the German group Ludvig Loewe acquired a majority stake in FN, a transaction that kicked up a stir in the Belgian press. Le Soir, for example, questioned whether the company should be still called Fabrique Nationale. However, the takeover ended the threat of legal action from the parent company, which was contesting whether FN was licenced to supply Mauser rifles outside Belgian and meet an order from Chile for 60,000 items. Nevertheless, the disadvantages of now belonging to an effective cartel were also apparent: some markets became closed to the company and orders could also be shared among the group’s businesses. Hence, FN would follow other arms manufacturers in further diversification – beginning with the production of bicycle parts.

The chance encounter in the US in 1897 between FN’s commercial director and firearms inventor John Moses Browning looms large in the FN story. Many of his patents were being manufactured in the US by Winchester, Remington and Colt, but a year after the meeting, the inventor left his hometown of Ogden, Utah, and the family arms business run by his brothers, for Herstal to oversee production of his automatic pistol. As many as 500 a day were being produced, and soon all officers in the Belgian army would be equipped with the gun.

In 1902, Browning tried to interest US manufacturers in his automatic shotgun, a world first, but it was FN that would acquire the licence, firming up the relationship with Browning Bros. FN was granted the right to use Browning as

a trademark several years later. John Browning would later die from a heart attack on the premises of FN in 1926.

Towards the end of 19th century, FN began developing its bicycle business, from initially producing ‘nipples’ that fix wheel spokes to the rim to designing a bespoke frame – and in 1898 the company produced a chainless bicycle, which found a regular customer in the Belgian gendarmerie. That same year, the company hired a motor specialist to develop a voiturette, a small car with a three-horsepower engine.

The manufacture of mopeds – attaching a motor to a reinforced bicycle frame – followed suit, along with a four-cylinder engine motorcycle in 1905. Some 9,000 copies of the model, the first of its kind to be mass produced, were sold in the three years leading up to the outbreak of World War I, with the Belgian and Russian armies regular clients.

The occupying German army requisitioned FN machinery at the start of the war, but the company’s board resisted the German government’s attempts to restart production, despite most of the directors being German. Managing director Alfred Andri was later imprisoned in Germany for this act of defiance, while chairman Georges Laloux endured a similar fate for his part in resisting German intentions. At the end of the conflict, German-held shares in FN were sold, and the company embarked on a process of restoration, mainly focused on its depleted range of machine tools.

The interwar years for FN were marked by the challenge of responding to a changing commercial environment of fluctuating retail prices, custom barriers and the protectionist policies of key export markets, and the depre -

ciation of the Belgian franc and unfavourable exchange rates.

Faced with the mass production know-how of US carmakers like Ford, General Motors and Chrysler – which all established assembly plants in Antwerp in the roaring twenties – FN refocused its automobile business on luxury, highend models. It produced 20,000 cars in 1927, making it the second-largest Belgian manufacturer after Minerva. However, the company could not compete with international rivals and ceased making cars in 1935. Nevertheless, production of specialist trucks, motorcycles adapted for the military and the three-wheeled Tricar (the Belgian army acquired 300 copies of this large motorcycle capable of transporting goods and people) continued…until another period of turmoil was heralded by the onset of World War II.

Recent historical landmarks:

1938

Ammunition factory in Bruges moves to a site in Zutendaal that is still in operation.

1952

Manufacture of engines and valves for aircraft and rockets begins (ending in 1990s).

1977

The group acquires Browning Arms Company.

1991

FN Herstal restructures around holding company, Herstal SA.

1997

Walloon Region acquires 100% stake in the almost bankrupt group for a symbolic Belgian franc.

2021-22

FN Herstal launches production line for electronic boards.

2024

Herstal Group formally changes its name to FN Browning Group.

HIV, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections are causing unnecessary suffering across Europe – it is time to take action.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by the United Nations in 2015, offer a shared global vision for a more prosperous and equitable world.

SDG 3 focuses on ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all, and Tar-

get 3.3 sets the ambitious aim of ending the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), and combating hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) by 2030.

Although preventable, 820 000 people were living with HIV, 3.2 million with hepatitis B and 1.8 million with hepatitis C in the EU/EEA as of the end of 2023, and tens of thousands were diagnosed with TB or STIs such as gonorrhoea, chlamydia or syphilis. While Europe has made strides in public health, progress towards SDG 3.3 reveals a critical moment requiring renewed focus and urgent action.

The data that the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has collected and presented in its newly released progress report shows a concerning picture. While

progress has been made in reducing new HIV and TB infections, the current pace is insufficient to meet the 2030 targets. Alarmingly, some STIs, such as gonorrhoea and syphilis, are also resurging across Europe, and a lack of crucial data obscures the true scale of the challenges posed by chronic hepatitis B and C.

More than a quarter of a million cases of HIV, TB, viral hepatitis, and STIs were reported last year in the EU/EEA, but these aren't just statistics. The numbers represent human suffering, lives at risk, families impacted, and a significant burden on healthcare systems and economies. Despite being preventable, every year, over 57 000 people in the EU/EEA die from AIDS, TB, and hepatitis – a high toll for a continent with available resources, knowledge and effective tools for prevention and control.

The path forward needs courage and commitment, requiring a ramping up of efforts across three key areas:

Prevention: Proven interventions like condom use, PrEP for HIV, preventative TB treatment, needle exchange programs, and hepatitis B vaccination should be scaled up and equitable access ensured.

Testing and treatment: Early detection and effective treatment are crucial, both for the health of the individuals impacted and to stop onward transmission of these infections. We must break down barriers to access and ensure everyone receives the care they need.

Monitoring and surveillance: Robust data collection and surveillance systems are essential to tailor interventions effectively for everyone, including vulnerable populations.

Addressing these challenges requires focused action. Greater emphasis must be placed on scaling up proven prevention measures and ensuring equitable access to testing and treatment. Sustained efforts are needed to reduce mortality from preventable diseases, and improving the availability and quality of surveillance data is fundamental to track progress accurately.

Europe needs a strong and united effort at all levels to accelerate progress, securing health for all today and the years to come.

Despite

being preventable, every year, over 57 000 people in the EU/EEA die from AIDS, TB, and hepatitis – a high toll for a continent with available resources, knowledge and effective tools for prevention and control.

From Putin’s early sabre-rattling to Trump’s demands for NATO burden-sharing, Belgium has ignored one warning after another. Wannes Verstraete, Associate Fellow at Egmont, the Royal Institute for International Relations, says the country must finally confront its chronic underinvestment

That complacency shattered in February 2022. Russia’s fullscale invasion of Ukraine forced even the most sceptical to confront a new era of collective defence.

Europe’s security landscape has shifted dramatically over the past two decades, yet while most of its neighbours have gradually adapted to the wake-up calls, Belgium remains locked in a slumber — always reaching for the snooze button.

In hindsight, the early warnings were unmistakable. One of the first came in February 2007, when Russian President Vladimir Putin used his now-famous Munich Security Conference speech to lambast the unipolar world order and NATO’s eastward enlargement – or “expansion”. A year later, Russia launched a military assault on Georgia — its first act of cross-border aggression in the 21st century. Yet Belgium and much of the West remained preoccupied with the financial crisis and the ongoing global war on terror.

The next wake-up call came in 2014. Following Ukraine’s pro-European Maidan Revolution, Russia responded by illegally annexing Crimea and funnelling weapons and troops into eastern Ukraine. Even then, it failed to prompt serious Belgian reflection.

When Donald Trump first entered the White House in 2017, he made it abundantly clear: Europe had to do more. NATO’s burden-sharing was no longer optional. Belgium responded with modest gestures. Prime Minister Charles Michel’s first government, from 2014–2018, laid out a ‘Strategic Vision’ and committed to upgrade some air, land, and maritime capabilities. But there was little sense of urgency — and no serious attempt to meet the NATO benchmark

of 2% of GDP on defence.

That complacency shattered in February 2022. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine forced even the most sceptical to confront a new era of collective defence. Belgium launched the STAR plan, under the Alexander De Croo government, which set modest increases in personnel and capability investment, alongside a limited rise in spending — to just 1.3% of GDP.

This year saw another wake-up call: Trump’s return to the White House. Once again, he pressed European allies to boost their defence spending. His demand? That NATO allies raise their defence budgets to 5% of GDP.

Belgium’s Arizona coalition under Prime Minister Bart De Wever initially aimed for 2% by 2029 and 2.5% by 2034. But the rapidly changing geopolitical climate, both within Europe and across the Atlantic, renders those timelines obsolete. In April, the government pledged to hit 2% this year — but without securing long-term structural funding.

Meanwhile, the pressure has been mounting. On May 9, following a meeting with Belgian Defence Minister Theo Francken, US Under Secretary of Defence Elbridge Colby publicly called on Belgium to step up. “As a founding member of NATO, host of NATO headquarters, and one of Europe’s wealthiest societies, we look to Belgium as an example for our European allies by increasing its defence spending to 5%,” Colby said.

Germany, a key European ally and neighbour, already signalled its willingness to increase their budget towards 5% of GDP. In Belgium, however, political fault lines are emerging. The Flemish Christian democrats (CD&V), a coalition partner, insist that 2% must remain the ceiling. Foreign Minister Maxime Prévot, from the Francophone centrist party Les Engagés, hopes to soften both the target and the timeframe ahead of the June 24-25 NATO summit in The Hague.

Realism must prevail. Belgium cannot keep lagging behind. With the global order in flux, a defence budget of 3% or more is no longer an abstract ambition. It is a strategic imperative to address legacy shortfalls, meet NATO’s capability targets and preserve Belgian influence.

Wannes Verstraete

As hard power returns to the global stage, Belgium faces a reckoning. Decades of defence neglect have left the country ill-equipped for today’s threats. With rising NATO expectations and hollowed-out institutions, rearming is no longer optional—it’s essential to preserve sovereignty, stability, and the safety of future generations, says retired Belgian army Lieutenant-General Marc Thys

The world has changed since the start of 2025. The changes are real and will have long-lasting implications: this is no black swan moment. Today’s global order is no longer shaped by treaties and trust, but by coercion and confrontation. Great power politics have returned – and yet Western Europe, and Belgium in particular, are woefully unprepared.

From Ukraine to Taiwan, from Greenland to the Arctic, hard power has eclipsed diplomacy. The rules-based system is yielding to the rule of force. Europe is relearning a lesson it long preferred to forget: soft power is a hollow promise without the steel of military strength beneath it.

That rediscovery has triggered a belated defence reawakening across the continent.

But decades of neglect cannot be reversed overnight, least of all in Belgium, where the atrophy was most acute. After the end of the Cold War, Belgium raced to cash in its peace dividend. Between 1989 and 2024, European Union countries cut defence personnel by an average of 40%.

Belgium slashed it by 78%. This is in a country that ranks seventh in GDP and eighth in population among EU member states. In 2016, the added value of the presence of international institutions in Brussels exceeded €5 billion — more than the combined budgets of Belgian defence, diplomacy, and development cooperation at that moment. Little wonder Belgium was labelled a free rider.

That legacy left the country ill-equipped for the threats of a new era.

In recent years, however, Belgium has begun to shoulder its responsibilities. The Vandeput Plan of 2017 pledged €9 billion in defence investment; the STAR Plan of 2022 added another €10 billion. Both were aimed at bringing Belgium into line with the NATO benchmark agreed in 2014 of 2% of GDP. This year, Belgium’s so-called Arizona government met that 2% target. On paper, the country has caught up.

Yet the goalposts are already shifting. At the NATO summit in The Hague this June, a new target of 5% might be set. For Belgium, that would mean more than doubling current expenditure — an eye-watering prospect. The structural fault lines in Belgium’s

fiscal architecture, especially the imbalance between federal and regional competencies, would be brutally exposed.

Defence is only one pillar of resilience. A nation capable of weathering this century’s storms must have strong, responsive institutions across the board. In Belgium, those too have been hollowed out.

Diplomatic capacity has dwindled to its lowest since 1945. The judiciary struggles to function. Core public services are chronically underfunded, despite public spending levels that exceed the EU average. Belgium spends 52.1% of its GDP on public expenditure (compared to the EU’s 47%) yet remains structurally unable to finance its sovereign functions effectively.

To its credit, Belgium’s current political leadership recognises the scale of the challenge. But few NATO or EU states face a steeper climb. Belgium has long benefited from a favourable status quo, one that let it enjoy peace and prosperity without paying the full price. We may even have financed our internal peace with money we didn’t have.

But there is no more room for finger-pointing. The past is a shared responsibility. The only way forward is together. If we are to safeguard our prosperity and security, we must invest — collectively, courageously and in solidarity – for the generations to come.

Decades of neglect cannot be reversed overnight, least of all in Belgium, where the atrophy was most acute.

Once the nerve centre of a Habsburg empire, Belgium’s postal service helped shape Europe’s first communication network. But in the digital age of emails, NFTs and dwindling letters, Bpost is fighting to stay relevant. From glorious Neo-Gothic post offices to stamps destined for Mars, this is the story of a proud institution struggling to deliver its future, as Derek Blyth writes

ot many people stop to read the two bronze plaques on the corner of a Brussels building in the Sablon neighbourhood. One is in French, the other in Dutch. Translated, they read, “Up until 1872, this was the site of the Tour et Tassis Mansion near which François de Tassis established the first international postal service in 1516.”

The greenish plaques are worn with age. Yet you can still make out the features of the young Emperor Charles V with his unmistakable pointed chin on the French plaque, while the Dutch plaque is decorated with a portrait of chubby François de Tassis.

The postal service was initially launched by the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I to deliver letters from Innsbruck, the seat of the emperor, to Brussels, where the Habsburg governor was based. This postal monopoly was granted to the Italian François de Tassis. Born Francesco Tasso, he came from an aristocratic family known as the Tassos or Tassis. The family later added Taxis to their name, which became Thurn und Taxis when they moved to Germany.

The imperial mail was delivered by a relay of horses that were changed every 28 kilometres. The system grew into a network of postal routes that spread from Brussels across much of Habsburg Europe, linking Germany, Spain, the Low Countries, France and Italy. A letter posted in Brussels would arrive in Innsbruck in precisely five and a half days. A letter to Blois in France took 60 hours to reach its destination, while a message to Rome would be delivered after an exhausting 250 hours on the road.

The Habsburg system might seem quaint compared to email or text messages. But the imperial post marked the emergence of a new communications network. Like the internet today, the postal service made communication faster and more reliable. Its arteries stretched over much of the European mainland, ensuring the sprawling empire could be efficiently managed. It also marked the beginning of Brussels’ ambition to be at the heart of Europe.

The city would go on to become a rail hub in the 19th century, a motorway hub in the 20th century, and a political hub in the postwar years. But it began with the mail.

Sadly, Brussels has almost forgotten that it was once the information hub of the 16th century. Most traces of the Tour et Tassis family disappeared after the family moved to Regensburg. The palace overlooking the Sablon church was torn down in the 19th century. It was replaced by the Royal Music Conservatory. Two baroque family chapels inside the Sablon church are the only reminders of the Tour et Taxis connection.

But the city did mark the 500th anniversary of the postal service. In 2016, a small crowd gathered in front of the plaque on the Sablon to mark the event that happened five centuries earlier. The guests included Archduchess Anne Gabrielle of Austria as well as Prince Dimitri della Torre e Tasso, who lives in Brussels. According to his LinkedIn profile, Prince Dimitri co-founded the fashionable Ixelles wine bar Etiquette.

The Tour et Taxis name also survives in the waterfront neighbourhood next to the Brussels canal. It stands on the site of a meadow where, according to some historians, the imperial post horses were put out to graze. The meadow was later turned into a vast industrial site occupied by railway yards, customs warehouses, and a post office.

As you might expect, Belgium has some exceptional post office buildings. Mechelen’s main post office occupies a 12th century building that was once a hostel for pilgrims. It then became the town hall before it was converted into a post office. Outside, an iron sign has the old Dutch word Posterijen, post office. The grandeur continues with an elegant rococo staircase leading into the building. Sadly, the interior is as functional as any other post office.

Many other impressive post office buildings were built at the end of the 19th century when everyone depended on the postal service to deliver letters, postcards and gifts. The main post office in Ghent is one of the most striking. With its

Derek Blyth

Like the internet today, the postal service made communication faster and more reliable.

The grandeur continues with an elegant rococo staircase leading into the building.

turrets and Gothic windows, it might almost be mistaken for a mediaeval palace. But look carefully and you notice tiny sculptures of carrier pigeons with letters in their beaks.

There was once a fascinating Post Museum on the Sablon that focused on the story of the postal service. But the museum closed. And then the country’s post offices, one by one, were shuttered.

The internet has made a huge dent in the post office’s revenue. People now send emails rather than letters. They post photos on social media rather than sitting down to write a postcard. And the government sends out invoices by email rather than using the post. As a result, the volume of mail has dropped dramatically over the past two decades.

Almost every historic post office building in Belgium has been sold off to developers. The main post office in Ghent has been converted into a shopping centre with a luxury hotel nestled in the upper floors. The modernist post office Ostend has also gone. Designed in 1953 by Gaston Eysselinck, the post office was an impressive building where tourists once queued up to send postcards or use payphones to call distant relatives. The airy building is now a cultural centre called De Grote Post. All that remains of its original function, apart from the name, is a row of wooden phone boxes in the café now used to frame giant photos of Flemish writers and artists.

The Grand-Poste in Liege is a magnificent Neo-Gothic building on the Meuse waterfront

designed by Edmond Jamar. It closed down in 2002 and stood empty for the next 14 years while various plans were proposed and subsequently rejected. Finally, the building was renovated to create a coworking space with a food hall and rooftop bar.

Other post offices have been left to rot. The modernist post office in Ixelles commune closed down some years ago. There was talk of converting it into a museum, or affordable housing, or maybe an extension to the architecture school next door. But despite its prime location behind Place Flagey, the building remains empty and covered in graffiti.

The future now looks bleak for post offices all over the world. In March, Denmark’s staterun postal service PostNord announced that it would end all letter deliveries at the end of 2025. Beginning in the summer, the company will remove all 1,500 Danish letter boxes. And it will also phase out postage stamps.

The situation in Belgium is not so dire. You can still find a local shop or supermarket with a Bpost counter. And the Belgian postal office continues to deliver letters and issues colourful stamps.

The first Belgian stamps were issued in 1849 with the head of Leopold I and the country named in French. For more than 150 years, the stamps have been printed at a production plant in Mechelen. It’s now one of the last printing facilities of its kind in Europe, with more than one hundred million stamps rolling off the presses

every year. As well as Belgian stamps, the production line produces stamps for Luxembourg, Portugal, Austria, Gibraltar and the Vatican.

The printing works known as Het Zegel (The Stamp) moved into an abandoned candle factory on Mechelen’s Vaartdijk in 1868. The canalside site lay close to Mechelen’s main station, which formed the main hub of the country’s dense rail network. It meant new stamps could be sent rapidly by train to every corner of Belgium.

The printing works finally closed down in 1993. For the next 30 years, the landmark brick building was left to rot. The decayed interior became a popular destination for urban explorers until the building was finally acquired by a project developer to create an office and apartment complex.

The passion for collecting postage stamps looks like it won’t survive. The Rue du Midi in Brussels was once dotted with dealers who sold exotic stamps from distant countries, along with vintage postcards sent a century ago. But hardly any of the dark little shops have survived. The philately clubs that once flourished all over Belgium are struggling to find younger members.

Yet Belgium continues to issue new stamps. These limited editions are not sold in post offices, but they can be ordered online. This year sees the issue of a stamp commemorating 600 years of Leuven University, along with a stamp illustrated with cartoon Smurfs promoting the United Nations sustainable development goals. There’s even a stamp coming out later this year to celebrate the number pi.

Other recent themes include Belgian bandstands, the country’s choreographers and the buildings of Hasselt. Meanwhile, Belgium’s weird surrealism is expressed by a limited-edition stamp illustrating a Tom Frantzen sculpture featuring a woman wearing only riding boots and a hat riding a flying pig.

Determined to shake off its stuffy image, Bpost recently launched a cryptocurrency stamp that combined a physical postage stamp with a collectable NFT that only exists as a digital token. It has also issued stamps that glow in the dark, a stamp dedicated to underwater species that is printed with a varnish that makes it seem that fish are swimming, and a 2024 stamp to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Universal Postal Union that includes 2,024 words (a world record).

Bpost might also be one step closer to a daily delivery to Mars. It has issued a series of stamps celebrating Belgian contributions to space exploration printed with the tariff region ‘Universe,’ to add to the existing three rates of Belgium, Europe and World.

There’s one topic that Bpost still hasn’t celebrated. “For a brief period, cats delivered mail in Belgium,” according to a recent post on X that went viral. “During the 1870s, the city of Liège ‘hired’ 37 cats to deliver mail in waterproof bags. As expected, the cats weren’t effective mailmen.”

Bpost might also be one step closer to a daily delivery to Mars.

The story relied on a long-forgotten article published in 1876 in the New York Times by the writer William L. Alden. The author claimed the cats were being trained to replace Belgium’s carrier pigeons. It was picked up and widely circulated on internet sites. But the Belgian broadcaster RTBF recently investigated the story and pronounced it an urban myth. The broadcaster went on to explain that cats were sometimes set loose in post offices to catch mice that might chew the mail.

For all its rich history and innovative stamps, the Belgian postal service is struggling to survive. It has seen a massive drop in letters sent, along with stiff competition from competing parcel delivery services. In a bid to remain relevant, Bpost has invested massively in parcel

lockers where customers can drop off and pick up parcels. It has already established 3,000 pickup points with a further 1,000 planned.

The semi-privatised company with a turnover of €4.4 billion is still in deep trouble. Earlier this year, the share price slumped by 60 percent, leading to comments that a Bpost share is now worth less than a postage stamp. The dramatic drop was caused in part by Bpost losing a lucrative contract to deliver newspapers worth €167 million, along with a bloated workforce, and a series of strikes in sorting centres across Brussels and Wallonia. “I was ready for a marathon when I started this job,” declared Bpost CEO Chris Peeters, “But I’m suddenly having to do it with a rucksack filled with ten kilos of rocks.”

The Belgian post office likes to believe it might one day deliver mail to Mars. But maybe it’s more likely that Belgium will follow Denmark and close down its postal service. If so, it would be the end of a rich history that began more than five centuries ago in the heart of Brussels.

2010: La Poste/De Post becomes bpost

2011:

After a gradual lifting of the postal monopoly, the Belgian postal market was fully liberalised: anyone meeting certain conditions can offer postal services in the country

2013: bpost SA is listed on the Brussels Stock Exchange

2016:

New parcel sorting centre in Neder-overHembeek is built

2017:

Acquisition of American company Radial, putting bpost group on track to become an international player in e-commerce logistics.

E-commerce is booming.

In 2016: Number of parcels processed per day was, on average 148,000, but by 2022, the last year bpost has figures, it was 549,000. The end-of-year period is bpost’s busiest, from Black Friday to Christmas. The peak of 813,000 packages processed per day was reached on December 4, 2024.

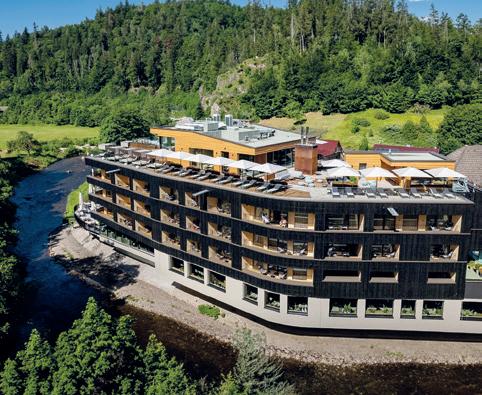

Your city spot to relax

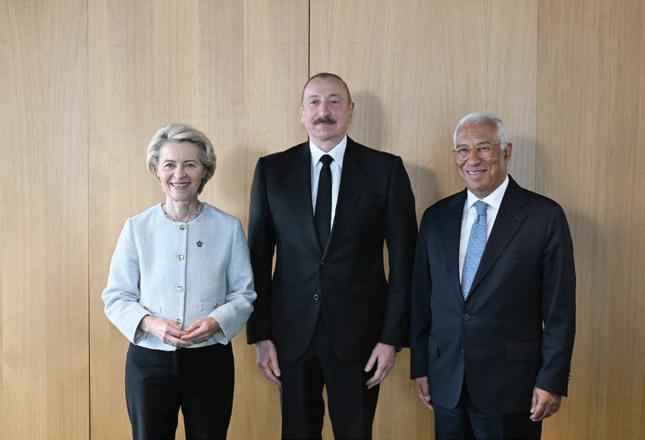

Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan to the Kingdom of Belgium and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Mission to the European Union

The EU is Azerbaijan’s largest trading partner, accounting for a substantial share of the country’s foreign trade.

Next year, Azerbaijan and the European Union will mark 30 years of formal diplomatic relations, commemorating the signing of the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) in 1996.

This milestone highlights a relationship built on mutual interests in energy, trade, and regional stability.

Celebrating its 107th year of independence, Azerbaijan marked the occasion on 28 May with a reception hosted by its Embassy in Brussels. The event brought together dip-

lomatic representatives, EU officials, and key partners, reflecting the country’s enduring ties and strategic cooperation with the European Union.

Since the early years of its independence, Azerbaijan has steadily built a strong and multifaceted partnership with the European Union, reflecting a shared commitment to political dialogue, economic cooperation, and regional engagement.

What initially began as a pragmatic collaboration in essential areas such as energy and trade has gradually evolved into a

broader, more strategic relationship that now includes diverse sectors like security cooperation, connectivity infrastructure, governance reforms, educational exchanges, and cultural initiatives.

Over the decades, this evolving partnership has strengthened mutual understanding and established Azerbaijan as a key political and economic partner for the EU in the South Caucasus region, where it plays a growing role in contributing to both regional stability and Europe’s long-term strategic goals.

Azerbaijan’s unique geographic location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, combined with its substantial energy reserves, has positioned it as an essential contributor to Europe’s energy diversification efforts. This role has been particularly important in the context of recent shifts in global energy supply dynamics, where ensuring reliable, secure, and diversified sources of energy has become a central concern for European policymakers.

In this context, the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) stands out as one of the most ambitious and strategically significant energy infrastructure initiatives of the past few decades. This multi-phase project, which connects Azerbaijan’s gas fields in the Caspian Sea to European consumers, has become a cornerstone of the energy relationship between Azerbaijan and the EU.

The corridor, which includes major pipeline systems such as the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) and the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), allows Azerbaijani natural gas to reach European markets directly for the first time, bypassing older and less stable supply routes. This not only enhances the EU’s energy security but also underlines Azerbaijan’s importance as a reliable and stable energy exporter. The strategic value of this partnership was further elevated in July 2022, when Azerbaijan and the European Union signed a memorandum of understanding to double gas exports to Europe by 2027. This forward-looking agreement signals a deepening of the energy alliance and reflects a shared interest in long-term cooperation amid global energy uncertainties.

At the same time, Azerbaijan is not limiting its energy policy to fossil fuels. The country has begun broadening its energy portfolio by investing in the development of renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power. These initiatives are not only part of Azerbaijan’s own national strategy for energy diversification and sustainability, but they also align closely with the EU’s climate objectives and its broader strategy for a green transition. By moving in this direction, Azerbaijan is opening up new possibilities for future cooperation with the EU in clean energy technologies and sustainable infrastructure development.

Beyond energy, economic and trade relations between Azerbaijan and the EU have grown increasingly significant, underpinned by mutual investment and a shared interest in economic diversification. Today, the European Union is Azerbaijan’s largest trading partner, accounting for a substantial share of the country’s foreign trade. Over the past few years, this relationship has expanded beyond hydrocarbons to include cooperation in sectors such as logistics, digital infrastructure, agriculture, and technology. European businesses are increasingly active in Azerbaijan, supported by an improving investment environment and gradual reforms aimed at modernizing the economy.

At the institutional level, negotiations are ongoing for a new EU–Azerbaijan Comprehensive Agreement, which is expected to further deepen bilateral ties. Once finalized, this agreement will replace the older Partnership and Cooperation Agreement and provide a modern legal and regulatory framework for bilateral trade, investment, and sectoral collaboration. It is also expected to promote regulatory alignment, improve access to European markets for Azerbaijani companies, and increase confidence among foreign investors. For Azerbaijan, this agreement represents not only a step forward in its economic development but also a means of consolidating a diversified and innovation-driven economy, which is seen by both sides as essential for long-term stability and mutual prosperity.

Transport and logistics represent another key pillar of cooperation between Azerbaijan and the European Union. Azerbaijan’s strategic location along the so-called Middle

Azerbaijan’s geographic location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia enhances its role in global connectivity.

Azerbaijan is opening up new possibilities for future cooperation with the EU in clean energy technologies.

Corridor—a key segment of the trade route that connects Europe with Central Asia and China—has significantly increased its geopolitical and economic importance. As global supply chains adapt to evolving geopolitical circumstances and seek alternatives to traditional routes, Azerbaijan’s reliable infrastructure and connectivity offer valuable opportunities for Europe’s eastward trade expansion.

Notable infrastructure projects, such as the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway, have already made a measurable impact by enhancing freight transport efficiency between Europe and Asia. Supported in part through cooperation with EU institutions and partners, this railway provides a faster and more secure overland link that reduces transportation time and supports regional economic integration. In parallel, the Port of Baku, situated on the Caspian Sea, has evolved into a major regional logistics hub, serving as a critical

node for the smooth transit of goods across both land and sea. These improvements are not just national achievements for Azerbaijan but also contribute directly to the EU’s broader objectives of strengthening trade connectivity and infrastructure across the region.

Looking ahead, the prospects for deeper Azerbaijan–EU cooperation are strong. As both partners continue to engage on strategic issues such as energy security, green transition, infrastructure development, and digital innovation, the foundation for long-term collaboration continues to strengthen. Ongoing negotiations for updated legal frameworks, combined with continued European support for Azerbaijan’s economic and institutional modernization, ensure that the partnership

On May 28, 1918, following the collapse of the Russian Empire, Azerbaijani national leaders declared the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR).

The ADR is considered the first parliamentary republic in the Muslim world and one of the first to grant women the right to vote—preceding even many Western nations. It embraced liberal democratic values and took initiatives that were remarkably advanced for the time, especially within the region.

Though the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic lasted only two years (1918–1920), the country made significant progress during this time with the creation of democratic institutions, promotion of universal suffrage, development of education, and active diplomacy, which laid the foundations of Azerbaijan’s modern statehood.

Every year on May 28th, Azerbaijan celebrates Independence Day, commemorating the founding of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) in 1918. This significant date marks the birth of the first secular democratic republic in the Muslim world. It is a moment not only of national pride but also of reflection on the country's journey through turbulent times, progressive achievements, and a forward-looking vision that connects Azerbaijan to the global stage.

In addition to industrial and scientific advancements, Azerbaijan experienced rapid urbanisation and infrastructure development. Cities like Baku, Sumgait, and Ganja became major industrial hubs, with factories producing machinery, chemicals, and consumer goods. The establishment of Sumgait as a major petrochemical center further strengthened Azerbaijan’s position in the Soviet economy.

Culturally, Azerbaijan saw a revival of literature and music in the examples of composers like Uzeyir Hajibeyli, Fikret Amirov, and Gara Garayev, who blended Azerbaijani folk music with Western classical traditions. Azerbaijani cinema also flourished, producing films that became popular across the USSR.

Despite these achievements, the Soviet period also brought political repression, restrictions on national identity, and economic dependency on Moscow. However, the advancements in industry, science, and culture laid the groundwork for Azerbaijan’s development after gaining independence in 1991.

The decline of Soviet influence in the late 1980s ushered in a period of uncertainty and upheaval for Azerbaijan. The crisis had already begun before independence, with one of the most tragic events in Azerbaijan’s history on January 20, 1990—a night that is remembered as “Black January”. In an attempt to crush Azerbaijan’s growing independence movement, the Soviet army launched a brutal military operation in Baku, opening fire on unarmed civilians. At least 147 people were killed and hundreds more injured. The massacre was meant to instill fear, but instead, it deepened the people’s determination for independence.

At the same time, Azerbaijan was completely isolated internationally, lacking strong diplomatic ties or economic partnerships. Foreign investment was non-existent, and even humanitarian aid was scarce. With the global community paying limiting attention, the country had to face its crisis alone.

Following Heydar Aliyev’s election as the president of the Republic of Azerbaijan in 1993, Azerbaijan entered a period focused on national development.

In international affairs, Azerbaijan pursued a balanced and strategic foreign policy, strengthening its global partnerships and positioning itself as an important player in the regional and global energy markets. Diplomatic relations were expanded, and the country became an active participant in various international organisations. These efforts contributed to Azerbaijan’s growing reputation as a stable and reliable partner on the world stage.

In more recent years, Azerbaijan began a new phase of development with stability and economic momentum. Large-scale

will remain adaptable and resilient in the face of future global and regional challenges. The shared goals and interests that bind Azerbaijan and the European Union—ranging from energy and trade to connectivity, governance, and culture—provide a comprehensive and durable foundation for cooperation. In an increasingly interconnected and uncertain global landscape, the partnership between Azerbaijan and the EU serves as a valuable example of constructive engagement, balancing strategic priorities with mutual benefit. As Azerbaijan continues its integration into global economic and political systems, its evolving relationship with the European Union will undoubtedly remain a key element in shaping both its domestic development and its international role.

infrastructure projects, economic diversification efforts, and increased engagement in international affairs all lead to the strengthening of the capacity of the state.

From the outset, economic modernisation was a central focus of the government. Building on the foundation laid by earlier energy agreements, Azerbaijan directed revenues from oil and gas exports toward development initiatives.

The completion of key energy infrastructure projects such as the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline in 2005 and the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) gas pipeline in 2006 enhanced the country’s role in regional energy supply. These efforts were later expanded through the Southern Gas Corridor, including the

European businesses are increasingly active in Azerbaijan, supported by economic reforms and investment incentives.

TANAP and TAP pipelines, which strengthened Azerbaijan’s energy connections with Europe.

Infrastructure development gained momentum during this period. Investments in transportation and logistics transformed Azerbaijan’s connectivity. Projects like the Baku International Sea Trade Port contributed to Azerbaijan’s growing role as a transit and trade hub in the Caspian region.

Azerbaijan’s increased visibility in the international arena was furthermore reflected in its role as host of major global events and its active participation in multilateral platforms.

The country successfully hosted Eurovision 2012, the inaugural European Games in 2015, the annual Formula 1 Azerbai-

jan Grand Prix, and matches during UEFA Euro 2020. It also welcomed world-class events such as the Islamic Solidarity Games in 2017 and the International Astronautical Congress in 2023.

In 2024 Azerbaijan hosted the COP29 event that marked a new commitment to channel $1.3tn of climate finance to the developing world each year.

In the cultural sphere, Azerbaijan is regularly hosting the World Forum on Intercultural Dialogues. Baku has also served as a venue for high-level international forums, including the Non-Aligned Movement Summit and various UN, OIC and OSCE conferences, underscoring Azerbaijan’s commitment to international cooperation.

Wind energy now powers nearly one-fifth of Belgium’s generation mix. Yet the road to greener energy is proving far from smooth. A mixture of interregional squabbles, ballooning infrastructure costs, and confounding permitting delays continues to slow the country's progress. Even Belgium’s neighbours are complaining, as Dafydd Ab Iago reports

Earlier this year, Dutch firm Whiffle, specialists in atmospheric modelling, accused Belgium of a novel offence: wind theft. Belgian offshore wind farms, they argued, are disrupting wind patterns and reducing yields for turbines off the Dutch coast. “You’re often stealing some of our wind,” claimed Whiffle’s CEO Remco Verzijlbergh in an interview with Flemish broadcaster VRT. Delft-based Whiffle, which advises the Dutch government, insists its stance is apolitical. But its message stirred a breeze of nationalist indignation.

The phenomenon, known as the "wake effect", is well-documented: turbines alter airflow, reducing wind velocity downstream. And with Belgium’s newest wind farms placed southwest of the Netherlands’ offshore clusters, a clash of turbine trajectories was perhaps inevitable.

Belgium currently has 2.3 gigawatts of power capacity from offshore wind—out of 5.6GW in total wind capacity. Another 3.5GW is planned through the Princess Elisabeth Island project, a vast artificial energy island rising 45km off the coast. Construction began in April, with engineers submerging concrete blocks to form its perimeter.

But dreams of a sleek North Sea energy hub are already snagging on reality. The project's modular offshore grid, MOG2, was originally costed at €2.2 billion. Latest estimates put it between €7 and €8 billion. Energy regulators have issued warnings; politicians are muttering about fiscal recklessness.

Underlying these challenges is Belgium’s unique political structure — federated, fragmented, and frequently fractious. Unlike in the Netherlands or France, there is no single minister or national body coordinating wind energy strategy. Offshore wind remains the federal government’s remit; onshore is the domain of the regions. The result is a patchwork of overlapping policies, inconsistent

incentives, and sluggish execution.

“Of course, it’s a pity we don’t have a national strategy,” says Fawaz Al Bitar, director general of Edora, Belgium’s Walloon and Brussels French-speaking federation for renewable energy. “We need more coordination. But you know how it works in Belgium.”

Despite this, each region has made its own pledges. Flanders, currently with 1,858MW of onshore capacity, aims to reach 2,640MW by 2030. Wallonia, with 1,528MW today, wants to hit 2,500MW. Offshore wind capacity is expected to jump to 5,800MW nationally by the end of the decade.

But the Brussels capital region remains off-limits to large turbines. “You are in the vicinity of the airport with a radar, and so it’s not possible to install a large wind turbine in Brussels — for the moment,” Al Bitar says.

Wallonia is showing signs of ambition. Its 2030 target is expressed not in capacity but production — 6,200GWh of onshore wind power to be produced annually. That could incentivise the deployment of more efficient, high-output turbines. But turning ambition into infrastructure is no small feat. As of January, Wallonia had 589 turbines across 152 projects, totalling 1,528MW of installed capacity. Reaching the 2030 wind production target would require doubling capacity within five years – and only a quarter of project permits are currently approved. “It’s a major challenge. The commitment is a first positive step. Now the Walloon government has to do everything to make it possible,” Al Bitar says.

The region faces hurdles, particularly in permitting, with only 25% of wind project permits approved. “It is really a pity,” Al Bitar says. He blames both local opposition and government inertia. “We still have a sort of nimby approach to wind projects.”

Dafydd Ab Iago

In 2024, Flanders installed just 12 new wind turbines — the lowest number in a decade. To hit its goal, it needs 35 large turbines per year, according to the region's Energy and Climate Plan.

Flanders still needs to decide on the rules, but the tallest 250-meter-high turbines would have to be at least 750 meters away from the nearest home.

Flanders faces similar obstacles—though of a more contradictory nature. The regional government has revised its onshore wind capacity target upwards to 2.8GW by 2030, from its previous goal of 2.6GW.

With approximately 1.8GW installed today, the region must commission 200MW annually for the next five years. There is scope for more ambitious targets, but the wind energy sector is concerned that there is no plan to realise them.

In 2024, Flanders installed just 12 new wind turbines — the lowest number in a decade. To hit its goal, it needs 35 large turbines per year, according to the region's Energy and Climate Plan.

Despite challenges, Belgium has built a world-class offshore wind sector. DEME and Jan De Nul lead in logistics and installation. Parkwind, part of the Colruyt Group, is active across Europe and beyond. ZF Wind makes turbine drivetrains at its Lommel plant.

Recent developments, though, raise concerns about contradictory signals. Energy Minister Melissa Depraetere, from the centre-left peat of the previous overcompensation for renewable producers. Consumers’ energy bills will remain unaffected.

Yet just days later, Environment Minister Jo Brouns, from the centre-right CD&V, proposed stricter distancing rules. Under the proposed rules, turbines would need to be placed at least three times their tip height from residential areas. Taller turbines can generate up to three times more energy than first-generation windmills, but stricter planning rules for turbines over 200 meters would threaten Flanders’ ability to meet its wind energy targets. The rule would also increase the cost of green energy certificates for wind.

Flanders still needs to decide on the rules, but the tallest 250-meter-high turbines would have to be at least 750 meters away from the nearest home. The rules could severely limit viable sites in densely populated Flanders. “It’s a contradiction,” says Maarten Dedeyne of the Flemish Wind Energy Association (VWEA). “A minister announces good news one day. Three days later there’s bad news for the sector. Regulation cannot change every one or two years. That’s very difficult for projects that need several years from scratch to build.”

Depraetere has since tried to reconcile with her government colleague. “Minister Brouns also agrees with the ambition to install more wind turbines. He might have been somewhat shocked himself by the concrete impact of the ‘three times tip height’ rule, which essentially means you’d hardly be able to place any wind turbines anywhere,” Depraetere told the Flemish Parliament. “No decision has been made about that either. It would also mean that Flanders would practically become a red zone for those wind turbines.”

Depraetere underscored the point that large wind turbines require less financial support and generate more energy than smaller models. The Flemish Energy and Climate Agency (VEKA) has calculated that smaller turbines still need about €20.8 per megawatt-hour in support, though savings on energy costs would outweigh these subsidies.

Nuclear or wind?

Meanwhile, nuclear power is creeping back into the mix. In May, Belgium repealed parts of its nuclear phase-out law, reopening the door for new nuclear development.

“It is no longer a matter of pitting energy

sources against each other in a binary, sterile debate, but of using them pragmatically and in complementarity,” Federal Energy Minister Mathieu Bihet, from the right-wing MR, told us. “You need electricity to phase out fossil fuels. You need it for heat pumps, for electric vehicles, for industry. And we don’t have enough of it.”