MAGAZINE No 57

Winter 2024/2025

The Louise Tower rises again I’m Leuven it: The city’s universities are 600 years old. Sort of Why Belgium’s new sex worker law has yet to change life on the street

MAGAZINE No 57

Winter 2024/2025

The Louise Tower rises again I’m Leuven it: The city’s universities are 600 years old. Sort of Why Belgium’s new sex worker law has yet to change life on the street

Once a motoring trailblazer, Belgium’s carmaking prowess is fading. How did it happen – and who’s left?

During the autumn and winter period, our coastal town offers an extensive and varied program for young and old. Whether it’s a cozy family outing, achieving sporting performances, enjoying gourmet food in one of the many delicacy shops or restaurants, Christmas and year-end shopping with family and friends, or skating on an ice rink with real ice... Knokke-Heist has something for everyone during the autumn and winter months.

Discover this and many more activities in our free winterbrochure or at mykh.be/winter.

You can find the winter brochure in all public buildings and various public places.

Who knows, it might have even landed in your mailbox.

WANT TO INVEST OR LIVE IN A NEW CONSTRUCTION ?

Les Promenades d’Uccle is an exceptional project, both in terms of its location and its services.

We offer houses and apartments in a contemporary, elegant style within an environmentally conscious residential area that combines the latest building technologies with advanced energy performance.

For you, as an investor, this means a future-proof investment with significant added value in the long term.

It may sound unlikely, but Belgium was once a carmaking trailblazer. In the early 20th century, Belgian car brands like Minerva and Imperia were elegant and exquisitely engineered. They were innovative too: Miesse pioneered steam motors and Delecroix developed the reverse gear. And they were fast: in 1899, Belgian engineer Camille Jenatzy’s Jamais Contente was the first car to exceed 100 km per hour.

Even when Belgian brands faded after the Second World War, the country’s reputation for manufacturing meant it was a top choice for factories churning out cars for others.

In the late 1990s, Belgium produced 1.2 million vehicles annually, making it the world leader in per capita production.

Those days seem long gone now. Car plants have closed one after the other: Renault Vilvoorde (1997), both Opel factories in Antwerp (1988 and 2010), and Ford Genk (2014). This year, Audi announced it would leave its massive car factory in Brussels, and Mechelen bus maker Van Hool filed for bankruptcy.

In this issue, we look at Belgian carmaking from its pioneering origins to its success stories and its setbacks. James Morrison, author of ‘Twenty Cars that Defined the 20th Century’, starts it off by charting the Belgian tinkerers, inventors and entrepreneurs who helped make the country a byword for carmaking.

Dennis Abbott looks at the failure of Audi’s venture in Brussels, with its state-ofthe-art plant producing high-end electric vehicles that the market was not ready for. Helen Lyons writes about Van Hool, which still makes top-of-the-range buses for all occasions but faces an uncertain future under new ownership.

The harsh new automotive era is not just a challenge for Belgium. Carmaking is still a totemic industry for Europe, for both its economic importance and for its symbolic value. Yet it is being buffeted by unprecedented forces. The green transition is supposed to herald a new emissions-free era, but Europe has been slow to roll out affordable models - while China has gained a vital foothold in the market.

Belgium’s once flourishing industry has shrunk. But it has not expired. Volvo’s plant in Ghent is rolling out a new generation of electric vehicles, as Lisa Bradshaw reports, while Volvo Trucks, also in Ghent, is cranking out units at a prodigious pace. And D’Ieteren, which has long been a major car importer and distributor, has expanded to become a €10 billion business, as Ellen O’Regan writes.

Elsewhere in our issue, Ciara Carolan accompanies a special police unit as it does its rounds in Brussels checking on homeless people – and treating them with sympathy and support. Also out on the street, for very different reasons, are sex workers. Their precarious situation should have improved when Belgium decriminalised prostitution in 2022, but as Marie-Flore Pirmez reports, change has been slow.

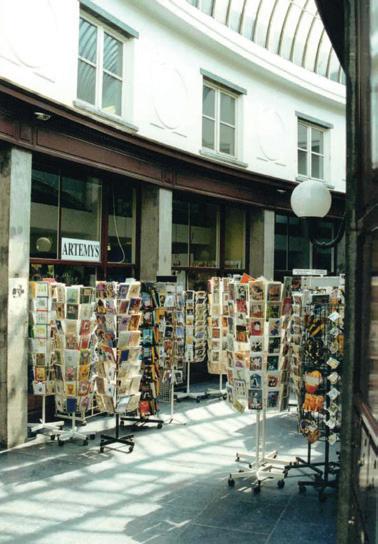

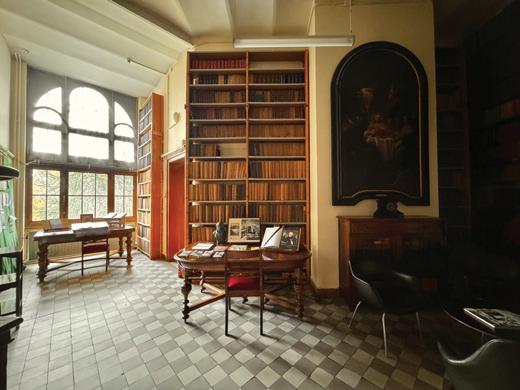

We have three features on august Brussels venues that are due to reopen soon. Frédéric Moreau writes about the Louise Tower, one of the first skyscrapers in the city, a sleek, modernist, 1960s monument that has been stripped and remade for the 21st century. Angela Dansby visits the Grand Hotel Astoria, a glamourous Belle Époque icon that is reopening after a deep clean. And Sabine Zednik-Hammonds reports from Galerie Bortier, a hidden gem for book lovers for 175 years but undergoing a controversial transformation into a gastronomic hub.

Leuven is Belgium’s oldest university, established in 1425, and is due to celebrate its 600th birthday next year, but as Philippe Van Parijs says, it has a complicated history. Pope Francis, who visited Leuven for the anniversary in September, also called on the Bollandists, the barely known religious group behind the world’s most authoritative collection of works on saints, as Rory Watson writes.

Angela Dansby takes a weekend break to Bastogne, the Ardennes town widely known as the epicentre of the Battle of the Bulge, as it prepares for the 80th anniversary of the brutal clash. Richard Harris reports on Belgium’s unexpectedly thriving circus culture, which ranges from big top shows to mesmerising avant-garde performances. And our senior tram correspondent Hugh Dow joins King Philippe on the new tram 10 as it sets off on its maiden voyage through the northern neighbourhood of Neder-Over-Heembeek.

Breandán Kearney meets brewer Claire Dilewyns in Dendermonde and uncovers the story of a hidden winter beer; Hughes Belin tries out chillis, sake, the Goods café and store, and the spectacular Entropy vegetarian restaurant; and Isabella Vivian highlights current and upcoming events worth checking out.

As part of our partnership with the Writers Festival of Belgium, we are publishing the winning entry from their 2024 short story competition, by Elisabetta Giromini, on a childhood weekend in the countryside that takes a dark turn.

And finally, while there may be threats to Belgian carmaking, Geoff Meade ponders more pedestrian perils as he crosses the street.

Leo Cendrowicz

Editor, The Brussels Times Magazine

Winter 2024/2025

The Brussels Times

Avenue Louise 54

1050 Brussels

+32 (0)2 893 00 67

info@brusselstimes.com

ISSN Number: 0772-1633

On the Cover Illustration by Lectrr

Editor Leo Cendrowicz

Publishers

Jonadav Apelblat

Omry Apelblat

Graphic Designer Marija Hajster

Sales Operations Managers

Caroline Dierckx

Gidon Tannenbaum

David Young

Contributors

Dennis Abbott, Hughes Belin, Lisa Bradshaw, Ciara Carolan, Angela Dansby, Hugh Dow, Richard Harris, Breandán Kearney, Lectrr, Helen Lyons, Geoff Meade, James Morrison, Frédéric Moreau, MarieFlore Pirmez, Ellen O’Regan,, Philippe Van Parijs, Isabella Vivian, Rory Watson

Photo Credits

Lectrr: Cover, 144, Belga: 8-11, 22-27, 32, 36-38, 48, 60, 66, 72, 74, 78, 92, 100, 102, 103, 106, 112-116, 145, 146 Lysiane De Galan - Rétine et Capteur: 12-13

Lisa Bradshaw: 39

Ellen O’Regan: 44, 46

Leo Cendrowicz: 46, 76-77

STIB-MIBV: 78

123RF: 56, 60, 70

UNAIDS/Miguel Soll: 58

Frédéric Pauwels: 58

Ciara Carolan: 64

Arnaud Siquet: 120-121

Angela Dansby: 122-126

Ashley Joanna: 128-129

Advertising

Please contact us on advertise@brusselstimes. com or +32 (0)2 893 00 67 for information about advertising opportunities.

The sunlight starts its first dance across the water. Time to reawaken your senses. Waves of tranquillity wash over you, as yesterday floats away.

Join the club with feeling. Aspria.

Frédéric

Marie-Flore

Ciara

108 The whole sky in the countryside is bigger

Elisabetta Giromini 110 The hidden keepers of saintly histories

Rory Watson 114 Tram 10, from the Military Hospital to Churchill

Hugh Dow

Battlefields and beyond in Bastogne

Angela Dansby

Breandán Kearney

Hughes Belin

Sabine

Philippe

Richard

Isabella Vivian 144 Breaking pavement news

Geoff Meade

Pope Francis arrives for a holy mass at the King Baudouin Stadium in Brussels on September 29 at the end of his four-day visit to Belgium, mainly to celebrate the 600th anniversary of the KU Leuven and UCLouvain universities. However, the trip was overshadowed by his dismissive comments on women, calling them "fertile hosts, carers and vital devotees”, and on abortion, calling Belgium’s legislation a ‘murderous law’ and doctors who perform abortions ‘contract killers’. He also failed to address King Philippe and Prime Minister Alexander De Croo’s calls to take more concrete actions to help survivors of abuse by the Catholic church.

Sporting Charleroi football fans pictured waving flares during a match against Standard de Liege. Flares are now a regular sight on the stands and are easily bought online. However, their increasing use is raising concerns amongst officials, who have underlined that it is against the law to enter a football ground carrying fireworks, flares, smoke bombs or any sort of pyrotechnics.

A solar storm created this dramatic Aurora Borealis – or Northern Lights - in the sky over Sivry-Rance in Hainaut.

Who knew that Belgians were carmaking trailblazers, whose ingenious innovations helped spark the €3 trillion industry that drives the world? For more than a century, a clutch of Belgians set the pace for luxury, sophisticated engineering and new technologies to help provide transport to the masses. As carmaking reinvents itself in the electric vehicle age, James Morrison, author of ‘ Twenty Cars that Defined the 20th Century’, charts the Belgian success stories

Jenatzy was more than just a thrillseeking speed addict. He was also a shrewd businessman who understood that the publicity he gained from breaking the land speed record would give his firm a competitive advantage over their bitter rival, the French coachbuilder Jeantaud, in the rapidly growing Parisian electric carriage market.

Yes, I did write the headline for this article and no, it isn’t the first of April.

It is a fact that Belgium was one of the early pioneers not only of the automotive industry but also of the electric car industry long before net zero had become the imperative that it is today. Add on top of this the fact that a Belgian-designed and manufactured electric vehicle – the Jamais Contente – set the land speed record in 1899 at Yvelines near Paris, recording a top speed of a giddy 105.882 km per hour, and there is a story worth telling. At the turn of the last century Belgium with its powerful industrial base and great wealth was the epicentre of automotive innovation.

So, who were these motoring pioneers, what were the lost Belgian marques and manufacturers and what happened?

It’s a historical lesson in start-ups never quite fully reaching sustainable scale up, of Belgian ingenuity being either too far ahead of its time – the equivalent of Betamax losing out to VHS – or swept away by the competition from its larger neighbours. It is nevertheless a proud track record of entrepreneurship and innovation.

The story began in the 1880s, after German Carl Benz developed the first practical automobile and the concept was quickly copied by engineers around Europe. Belgians were quick to spot the potential of these horseless carriages. As a rich country, there was a market for the fantastically expensive, coachbuilt creations that began to grace the former stable blocks of the well-connected and the well-to-do.

The Jamais Contente was the creation of Belgian engineer Camille Jenatzy nicknamed Le Diable Rouge for his fiery ginger beard and love of speed. But Jenatzy was more than just a thrill-seeking speed addict. He was also a shrewd businessman who understood that the publicity he gained from breaking the land speed record would give his firm a competitive advantage over their bitter rival, the French coachbuild-

er Jeantaud, in the rapidly growing Parisian electric carriage market.

The fact that the fastest car in the world was an electric vehicle may come as something of a surprise to many, but the internal combustion engine had yet to establish its dominance. The jury was still out in a threehorse race (with no actual horses obviously...) between steam, electricity, and petrol. Like many other developments at the time – tiller steering versus steering wheels; the Levassor principle, where the engine is in front of the driver, versus rear engine – this was an age of experimentation. In terms of propulsion, on the streets of Paris and Brussels, electricity was in pole position.

Even at this early stage some of the current limitations of electric vehicles were present. While range was not an issue for a car built solely to go as fast as possible in a straight line, weight was.

The Jamais Contente sought to offset the huge weight of the lead-acid accumulator batteries needed to power it by having revolutionary partinium alloy bodywork made from a mixture of magnesium, aluminium and tungsten – another innovation that would take many years to re-emerge having lost the car bodywork battle to steel. Aerodynamic, low coefficient of drag coachwork – albeit severely compromised by the ridiculously high driving position and the fact that the streamlined torpedo bodywork sat on an old-fashioned cart-sprung chassis – was an innovation that would take a further 30 years to become mainstream.

Unlike today’s electric vehicles, Jenatzy’s creation did not benefit from frictionless direct drive, but instead its twin Postel-Vinay 25kW electric motors were channelled to the rear wheels by an energy-sapping cog and chain drive. This, coupled with the tiller steering and unyielding suspension (despite the Michelin tyres) must have made the 68hp vehicle quite a handful and 100 km/h feel something like the equivalent of Mach 1. Indeed, when interviewed afterwards, Jenatzy

said of the experience that it the car felt like a "projectile ricocheting along the ground.” While it may have won races, it certainly wouldn’t have won any prizes for driver comfort.

Not all early Belgian manufacturers opted for electric propulsion. Miesse, a Brussels manufacturer based in Rue des Goujons in Anderlecht, favoured the tried and tested technology of steam. Founded by Jules Miesse in 1874, Miesse’s early cars were powered by three-cylinder steam engines from 1896 until 1900. The chassis were made of reinforced ash hardwood and the boiler located under the bonnet.

The first Miesse petrol engine car appeared in 1900 and by 1904 the company had branched out into the motorised taxi market offering either a four-cylinder 2.0 litre or an eight-cylinder engine – the latter being an elongated version of the former. The firm also produced trucks to be exported to the Congo Free State. Miesse’s son took over the business in 1927 and decided to specialise in trucks and buses discontinuing car production. By 1929 Miesse had bought the Bollinckx works, allowing for an increase in its Junkers diesel-powered truck production to 100 per year. The firm survived for a century with the last vehicle – a bus – leaving the production line on July 12, 1974.

The list of early Belgian manufacturers is impressive but largely unfamiliar today –there were by some estimates more than 200 – a familiar picture across the industry glob-

ally at the time as former bicycle and armaments manufacturers sought to diversify into the newly emerging market.

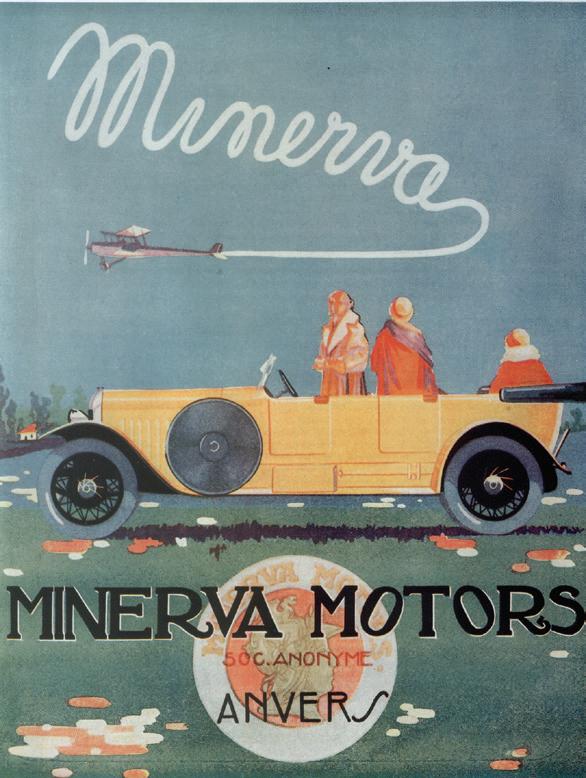

As was the case in Britain, mergers and acquisitions had radically pruned the number within a decade. Production was not concentrated in Brussels either but distributed across the country with one of the longer surviving marques, Minerva, based in Antwerp, and Imperia and Nagant in Liège.

Belgian manufacturers were not only pioneers in the field of electric propulsion but also the first with inventions like the electric cigarette lighter and the hybrid engine (Adrien Piedboeuf’s Imperia), and reverse gear (Delecroix). The Imperia factory at Nessonvaux, built in 1907 in the style of a medieval castle, even featured a one km rooftop test track years before the famous Lingotto Fiat factory in Turin or the Chrysler factory in Buenos Aires. Unlike Lingotto, Nessonvaux was not purpose-built but was a former armaments factory: the rooftop test track was added later following complaints from local residents about the factory’s tendency to road test their vehicles by driving around the town’s narrow streets at high speed. The key early Belgian manufacturers were:

• Bovy, who produced trucks and light cars until the 1950s,

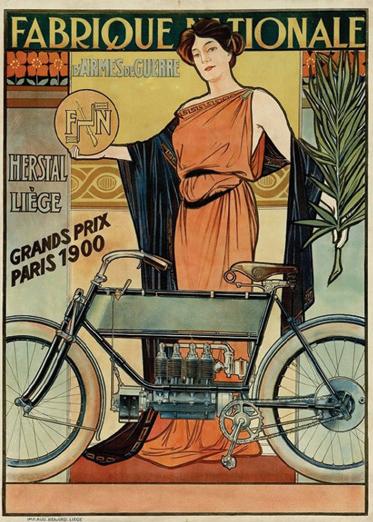

• FN, originally a weapons manufacturer (like the UK’s BSA), produced passenger cars until 1930,

• Excelsior, who lasted a similar length of time and produced sports and racing cars,

• Imperia, set up in 1904, who built sports and passenger cars until 1948,

• Nagant, another weapons manufacturer turned car manufacturer Metallurgique, focussed on the high-performance market segment until 1928,

• Minerva, the ‘Belgian Rolls Royce’ and one of the longest surviving of the original Belgian pioneers,

Belgian manufacturers were not only pioneers in the field of electric propulsion but also the first with inventions like the electric cigarette lighter and the hybrid engine (Adrien Piedboeuf’s Imperia), and reverse gear (Delecroix). The Imperia factory at Nessonvaux, built in 1907 in the style of a medieval castle, even featured a one km rooftop test track years.

• Vivinus, who sold German cars with Belgian coachwork,

• Delecroix, who pioneered the reverse gear,

• Pipe, a successful early race car manufacturer whose products competed in the Paris-Berlin races of the period.

Indeed, before the outbreak of World War II, Belgium had approximately 100 car manufacturers and a thriving export industry. At Autoworld, the car museum in the Cinquantenaire Park, a section dedicated to Belgium's automobile heritage displays 20 emblematic vehicles, including the Minerva, FN, Imperia, Belga Rice and Excelsior – and celebrates the inventors, industrialists, engineers, designers and even race car drivers that built Belgium’s car reputation.

Post Wall Street Crash however, US protectionism spelled the beginning of the end of a sector that produced vastly more vehicles than its domestic market could ever consume.

Consolidation was inevitable with Imperia taking over Metallurgique in 1927, Excelsior in 1929 and Nagant in 1931 before merging briefly with Minerva in 1934 only to get divorced five years later in 1939. Post-war, firms like Bovy the truck manufacturer and Brossel Freres the bus and coach builders found themselves merging before being taken over by the UK’s Leyland group.

Imperia eventually assembled Standard Vanguards in the late 1940s and 50s at its Nessonvaux factory until Standard Triumph built a new factory at Malines in Mechelen which opened in 1960 effectively putting Imperia out of business. The Malines Leyland Triumph factory was renowned for the quality of assembly (the full range from Heralds to TR4 sportscars being built there) with engines bench tested before being fitted and a legendarily good paint shop.

The British Motor Corporation meanwhile bought the factory at Seneffe in 1965 in Hainaut which had been built two years earlier by the Belgian MG main distributor. This became the main hub for British Leyland’s European operations employing 30,000 workers and running assembly lines producing over 3,000 Austin Minis, Allegros and Morris Marinas a day at its height in the mid-1970s. As Leyland Triumph was forced by the British government to merge with the insolvent British Motor Corporation in 1968, two factories were no longer required, and the smaller Malines plant eventually closed in 1975. The parlous state of the UK British Leyland, parent company led, in turn, to Seneffe’s closure in 1980.

Minerva’s story is an interesting one. As with Rover in the UK, Minerva’s origins lay in the manufacture of safety bicycles and sub-

sequently motorbikes – a promising coincidence as the two companies were to go into partnership in the early 1950s when Minerva won the contract from the Belgian army to build a version of the British Land Rover under licence.

This utilitarian, noisy and uncomfortable workhorse was a far cry from Minerva’s pre-war products which were very much at the luxury end of the market and were the transport of choice not only for the Belgian royal family but also for Hollywood stars and American industrialists.

Minerva’s first foray into internal combustion power had taken the form of motorised bicycles known as motorcyclettes: a small engine bolted onto the frame of a standard bicycle providing power to the wheels by a system of belts and pulleys. These ingenious motorbikes were the equivalent of today’s e-bikes: a relatively cheap and amazingly economical form of mass transportation. They were hugely popular far beyond Belgium’s borders – indeed the first British Triumph motorcycle was powered by a Minerva engine.

However, it was in luxury car production that Minerva excelled. Such was the quality of Minerva’s earliest offerings that before joining forces with Henry Royce in 1904, Charles Rolls was a luxury car dealer in London selling Minerva cars. The breakthrough for Minerva came when it secured the worldwide licence to produce American Charles Yale Knight’s ‘Knight’ engine. This, thanks to extra sleeving on its overhead valves, was virtually silent as well as both smooth and powerful. Engine sizes grew from straight six to straight eight cylinders and in the interwar period Minerva was a serious rival to Rolls-Royce with growing sales in the US and across Europe. This was all before the Wall Street Crash which forced its short-lived merger with Imperia.

Post-war, the Minerva Land Rover – a locally bodied (in steel rather than the UK equivalent’s Birm-a-Bright aluminium) was built under licence from Land Rover. Distinguishable to the trained eye by the sloping front wings (unlike the slab-fronted UK version) and different grille, Minerva Land Rovers not only mobilised the Belgian armed forces but also the Rijswacht. All was well until a breach of contract court case between Solihull and Antwerp – which Minerva won – soured the relationship and Land Rover decided to revoke the production licence.

Minerva’s demise soon followed in 1956 and with it seemingly the end of the Belgian pioneers. Seemingly, because even after the first pioneering wave, the Belgian motor industry continued to innovate. APAL produced sportscars using fibre-reinforced plastic (APAL standing for Application Polyester Armé de Liege) from 1961 until as recently as 1998.

The move away from the domestic pioneers towards Belgian assembly plants for foreign-owned manufacturers began in the interwar years with General Motors (Chevrolet and Cadillac) at Antwerp; Ford initially at Antwerp in the 1930s then subsequently at Genk; and Renault at Vilvoorde. Along with Leyland Triumph and the British Motor Corporation, these were mainstays of the Belgian automotive industry in the interwar and postwar periods. Not to mention the Audi Brussels assembly plant, which started out assembling Studebakers and VW Beetles in 1948, and has cranked out some eight million vehicles.

Belgian engineering skills, and high-quality production standards coupled with the country’s convenient geographical location and membership of the-then European Common Market made it an attractive choice for volume production. Ford at Genk was churning out 470,000 Sierras and Mondeos in 1994, the General Motors factory in Antwerp which became the European centre of Opel production until its closure in 2010 had originally opened on April 2, 1925, producing CKD Chevrolets and Cadillacs. This may explain why, following the demise of Minerva, the Belgian royal family opted for Cadillacs in the 1950s and 1960s as the preferred royal transport.

So, what happened?

A process of adaptation and specialisation kept, and still keeps, the Belgian motor industry flame alight. Indeed, the Belgian automotive industry, in all of its branches, still employed 160,000 skilled workers in 2022 (over 2.6% of Belgium’s GDP). Belgium remains a centre of innovation and quality yet only has one remaining domestic car manufacturer – Gillet - as well as a bus manufacturer, Van Hool.

Such was the quality of Minerva’s earliest offerings that before joining forces with Henry Royce in 1904, Charles Rolls was a luxury car dealer in London selling Minerva cars.

The Belgian automotive industry, in all of its branches, still employed 160,000 skilled workers in 2022 (over 2.6% of Belgium’s GDP).

Gillet is a niche manufacturer based in Gembloux and founded in 1992 by Belgian racing car driver Tony Gillet. Its product, the Vertigo, is a handbuilt ultra lightweight supercar. Van Hool, the global bus and coach manufacturer, was founded in 1947 by Bernard van Hool (1902–1974) in Koningshooikt, near Lier filed for bankruptcy in April of this year and was saved a few days later when its trustees accepted a takeover bid from the Dutch company VDL (see separate article).

Despite foreign manufacturers closing their factories due to global overcapacity and internal rationalisation – Renault in the 1990s, Opel in early 2010 and Ford in 2007 –the industry survives. There may be question marks over Audi in Brussels, but Volvo Cars and Volvo Trucks in Ghent are both cranking out top-of-the-range vehicles.

This is largely because the remaining assembly plants remain world class. Volvo Trucks in Ghent has an annual production of over 45,000 units. And Belgium is also a hub

for sophisticated component manufacture. Ferrari and AMG high-performance transmissions are designed and produced in Zeldegem by Tremec. Automatic transmissions are built in Braine L’Alleud by AWEurope. Millions of components are manufactured by companies like VALEO, Continental and TYCO Electronics.

In addition, Belgium is the home of key research and development centres including Toyota in Zaventem and Ford in Lommel. On top of this are the customizers like Jem Design in Brakel, who are world leaders in aftermarket bodywork kits.

The success of Addax the e-truck manufacturer in Deerlijk shows clearly that today the focus has come full circle back to the zero-emission vehicles of Belgium’s automotive pioneers – they were 125 years ahead of their time.

If Jenatzy were here today, he surely would be smiling wryly. Far from being “jamais contente” he would say, “très contente.”

The smart charging station. And design as well. There are charging stations, and then there’s Smappee. Smarter. Better looking. And more cost-effective too. Smappee combines all the good things you wish for in a charger. Beautiful design that you can be proud of backed by sophisticated technology. That is why those who want to smartly save, choose Smappee.

Would you like to know which charging station perfectly fits your business? Contact us via smappee.com

More than ever, it is crucial to reinforce the right of EU mobile citizens to vote and stand as candidates in elections in the EU country where they reside.

The opportunity to freely travel, reside, work, and pursue education in any EU country has been transformative for citizens and is a core aspect of European Union citizenship. This year, a record-breaking number of elections will take place in 50 countries, attracting over 2 billion voters globally.

More than ever, it is crucial to reinforce the right of EU mobile citizens to vote and stand as candidates in elections in the EU country where they reside. While a significant 74% cherish the ability to vote while living abroad, many EU mobile citizens lack interest in their host country's political landscape, resulting in low political participation.

Under the same conditions as nationals, every citizen of the Union has the right to vote and to run for office in municipal and European elections in the country they reside in, as enshrined in Article 40 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

In the current political sphere, elections are a pivotal defence against rising anti-democratic forces that threaten our core freedoms and the foundational principles of the European Union, including the rule of law and human rights.

The European Union boasts approximately 11 million mobile EU citizens of who are eligible to vote, constituting over 2% of the total voting demographic across the EU. Yet, numerous barriers impeding the political engagement of EU mobile citizens need proactive solutions to enable their active involvement in the democratic process.

In recent years, the European Citizen Action Service (ECAS) has conducted several focus groups in Member States holding municipal elections. These sessions aimed to uncover the reasons behind the lack of engagement of EU mobile citizens in their host countries and explore solutions that can foster their political rights and encourage them both to vote and stand as candidates.

The findings from the focus groups indicate that the main barriers to political engagement of EU mobile citizens can be categorised into four groups:

1) Language barriers.

2) Administrative burdens (including lack of training of civil servants).

3) Lack of precise data on participation.

4) Limited awareness of citizens on the role of the EU institutions.

Efforts to engage EU mobile citizens in political awareness campaigns are lacking. This is compounded by language barriers that hinder access to vital information on voting procedures and political manifestos that are often not translated into English or the most widely spoken language of the EU mobile community.

Further action is also needed to alleviate administrative burdens and streamline procedures, as registration processes are often complex, with deadlines set months before the voting day, and options like proxy voting or e-voting are very limited in most Member States, if not non-existent. Moreover, municipalities fail to engage with the EU mobile community to inform them about their right to vote and stand as candidates for both EU and municipal elections. Enhanced training of civil servants dealing with EU mobile citizens would be needed to ensure adequate knowledge about EU political rights and effectively inform newcomers.

To understand why political participation is low, it is also essential to gather precise data on the political participation of EU mobile citizens in municipal and European Parliament elections in their host Member State. The EU mobile community does not constitute a hetero-

geneous group. Therefore, understanding the level of participation in each sub-group (e.g., age, duration of the stay in the host country, language proficiency, etc.) can provide insights into specific barriers each group faces.

The EU mobile community is the embodiment of an integrated European Union that gives each citizen the right to freedom of movement and residence, a cornerstone of EU citizenship as established by the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992.

The new European Commission and Members of the European Parliament are urged to promote awareness, facilitate the political involvement of EU mobile citizens, and address current barriers. This is an essential demographic with the power to make an effective difference in elections. Streamlining processes in all Member States and informing EU mobile citizens about their political rights upon arrival is crucial to make it easier for them to feel empowered in their rights when settling in a new Member State.

We at the European Citizen Action Service (ECAS) remain committed to advocating for better and higher political participation of the EU mobile community in both municipal and EU elections, providing training to civil servants at the local level, increasing awareness of EU rights, and driving collective action to empower EU mobile citizens' democratic participation in their host countries.

Marta Azevedo Silva, Communications Manager at the European Citizen Action Service (ECAS)

Streamlining processes in all Member States and informing EU mobile citizens about their political rights upon arrival is crucial to make it easier for them to feel empowered in their rights when settling in a new Member State.

Cars have been built at the Brussels assembly plant in Forest for the past 75 years, starting with the American Studebaker, but the current owner, Audi, is set to leave next year. The decision has sent shockwaves through Belgium’s automotive industry, leaving almost 3,000 workers uncertain about their future. With no new buyer in sight, it looks like the end of the road for carmaking in Brussels, Dennis Abbott asks what went wrong

Audi blamed its decision on a sharp drop in orders for its flagship Q8 e-tron models, amid increasing competition in the electric luxury class market where the fourring brand is up against Tesla, Volvo, Mercedes, BMW, Jaguar and Porsche, as well as subsidised Chinese makes.

The slick opening promotional video on the Audi Brussels website gives little hint of impending doom.

Far from it. Against the backdrop of a suitably propulsive soundtrack, the footage begins with a dramatic aerial shot of the sprawling urban plant in Forest (Vorst), located to the west of the city centre next to the ring road. The camera pans down to the carbon-neutral factory’s expansive roof-top, covered in solar panels. It’s a message. In case the viewer doesn’t immediately catch on, the word “sustainability” pops up, followed by “we set the course…for a sustainable future.”

It’s a line that hasn’t aged well.

The camera then takes us inside the stateof-the-art, 1.5 km long, spotless assembly hall, capable of producing nearly 200 Audi Q8 e-tron models a day. We see lines of gleaming, dancing yellow robots, busy building out the skeletons of each car – lifting, drilling, fixing and welding hundreds of the parts which go into the construction of each electric vehicle (EV).

There are humans in the picture, too, doing highly skilled things. Men and women of varying ages and from different backgrounds. This diversity is highlighted in the video with a series of beaming portraits of smiling employees, overlaid with the word “together”. A happy worker peers through a partially built car and forms a heart shape with his hands.

Just over two minutes long, the film ends with the line: “Audi Brussels. Where we create masterpieces with passion” – a nod perhaps towards Belgium’s artistic heritage.

It seems a tad surprising no-one has thought of taking it down, in view of recent developments which have left nearly 3,000 workers facing a precarious future.

The bombshell news of the plant’s “restructuring” – in the eyes of many a euphemism for its likely permanent closure – came in the second week of July, just before it shut for

the summer break. By late October, Audi confirmed the worst: it would end production at the Brussels plant in February 2025. The management has also promised that there will be no redundancies in 2024 and is continuing its search for a buyer.

Audi blamed its decision on a sharp drop in orders for its flagship Q8 e-tron models, amid increasing competition in the electric luxury class market where the four-ring brand is up against Tesla, Volvo, Mercedes, BMW, Jaguar and Porsche, as well as subsidised Chinese makes. The German carmaker also pointed to “long-standing structural challenges” which have dogged the site in Forest.

Production of the Q8 e-tron is expected to move to Audi’s newest plant at San José Chiapa in Mexico, where labour costs are substantially lower – average monthly pay is about a quarter of the level in Brussels.

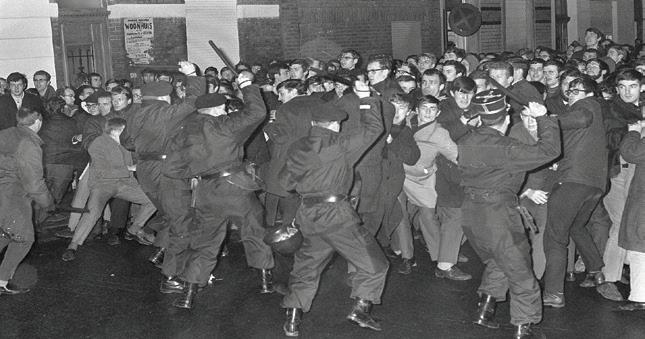

Audi’s restructuring announcement sparked a furious response.

Sor Hillal, general secretary of the FGTB (fédération générale du travail de Belgique) trade union, blasted what he called “rampant deindustrialisation.” As tensions threatened to spiral out of control, workers at the plant, returning after the summer, were locked out after seizing the keys to nearly 300 new and unfinished cars.

While Audi management and unions agreed to resume production, thousands of demonstrators took to the streets of Brussels to express solidarity with the Forest workforce.

New investors or buyers have been sought, with longtime Volkswagen Group importer D’Ieteren and Chinese carmaker NIO mentioned as possible white knights.

D’Ieteren was thought to be considering turning the site into a reconditioning centre for used cars, also known as recon, which is the process of repairing and restoring all aspects of the vehicle before resale. And while NIO was linked to the plant, CEO William Li

dismissed the notion. “How could NIO afford a factory that Audi cannot afford,” he told a Chinese news site.

Audi says that it has already looked at more than 20 alternative business models but found no economically viable solution for the plant.

In the meantime, it has launched talks with unions under the so-called Renault Act, introduced in 1998 after the sudden closure of the French carmaker’s factory in Vilvoorde with the loss of around 3,500 jobs. The law states that advance notice must be given of mass redundancies and that the government can demand repayment of state subsidies (which could amount to at least €20 million in tax incentives and aid for greening and training at Audi Brussels).

The Brussels plant was built in 1948 by D'Ieteren, and since then, countless models have been made there, from the American Studebaker to the VW Beetle and Golf to the Seat Toledo and Porsche 356 to electric Audis. The plant changed hands in 1970 when it was sold to Volkswagen, and again in 2006, when Audi took it over. But this time, it looks like the end of the road for carmaking in Brussels.

So where did it all go wrong?

I asked four experts for their views on the Belgian carmaking sector and whether Audi could have done anything to avert the present crisis.

First up is Professor Paul De Grauwe, a former senator and one of Belgium’s most distinguished economists, who describes himself as “an avid reader of the Brussels Times”.

He believes Audi made a “strategic mistake” in focusing on high-end electric vehicles. With a range of up to 600km, and prices starting at €91,690, the Q8 e-tron is not cheap. “They made the wrong bet. The problem is they are addicted to the luxury market. The Chinese are much cleverer in developing smaller electric cars and aiming for a mass market.”

De Grauwe, who is an emeritus professor at KU Leuven and lectures at the London School of Economics (LSE), has long predicted a decline in the Belgian auto sector, for three main reasons: globalisation, delocalisation and technological progress. “We shouldn’t be surprised about what’s happened,” he says.

He points to a collapse in domestic car production since the closure of Renault, with Opel shutting its Antwerp base in 2010 with the loss of 2,600 jobs and Ford ending operations in Genk in 2014 with 4,000 redundancies, not to mention thousands more jobs which have vanished in supply chains.

Part of the problem, De Grauwe explains, is that the Belgian industry has concentrated on assembling cars rather than on making them. “We’re a small country and import a lot from our bigger neighbours. The value-added from

assembling cars is relatively small.”

Even if the workforce at Audi was to increase its productivity, this would not have helped. “When productivity goes up, it just means prices will fall and so will employment levels.”

He sympathises with Audi, however, over the constraints it has faced due to the site’s location in a congested, built-up inner-city area, where there is no room for further expansion. In contrast, the 78-year-old professor points out that Elon Musk’s Tesla plant at Gruenheide, outside Berlin, has “plenty of space” to grow.

Asked whether the Belgian government should step in and provide additional subsidies to Audi, De Grauwe shakes his head. “No, that’s a very foolish policy. If firms run into trouble they leave anyway. Governments should invest in public goods like education and R&D – not in trying to pick winners.”

Although he paints a rather gloomy picture, De Grauwe insists that there is hope. He is confident Belgians will find “new outlets”, especially, but not only, in the services economy. “I remember people were very pessimistic in the 1970s when the steel and textile industries were struggling, but industry continued,” he says.

Leo Van Hoorick, curator of the Autoworld museum in Brussels, shares De Grauwe’s diagnosis of a sector in decline.

“The car manufacturing industry is very sick – not only in Belgium but in the rest of Europe, too. At the end of the 1970s, Belgium was the biggest car producer per capita in the world. But then production began to move to eastern Europe and Turkey where labour costs were cheaper,” he says.

Despite a proud manufacturing history its brands such as Minerva in Antwerp, Excelsior

They made the wrong bet. The problem is they are addicted to the luxury market. The Chinese are much cleverer in developing smaller electric cars and aiming for a mass market.

At the end of the 1970s, Belgium was the biggest car producer per capita in the world. But then production began to move to eastern Europe and Turkey where labour costs were cheaper.

in Zaventem and Impéria in Nessonvaux, Van Hoorick acknowledges that the seeds of the industry’s problems go back a long time.

It was more than a century ago that the government brought in a law which forced foreign carmakers selling more than 250 vehicles in Belgium to build an assembly plant in the country. It seemed a good idea at the time.

Ford arrived in 1922, followed soon after by GM, Citroën and Renault, with Peugeot joining them just before the Second World War. The plants created thousands of jobs.

“It was easy to import parts through the port at Antwerp – and, thanks to tax breaks, it was much cheaper to assemble cars in Belgium than to import the finished product,” says Van Hoorick.

But this also meant there was less incentive for Belgian firms to design and build their own brands. Excelsior was bought by Impéria which shut in 1948, and Minerva disappeared in 1956.

If poor decisions with unintended consequences were made in the past, Van Hoorick points to two much more recent, inter-connected “major errors”.

“One of the biggest mistakes we’ve seen is the fault of the European Union,” he says, referring to a law which will require all new cars and vans sold in Europe to be zero-emission from 2035. “The infrastructure for electric vehicles wasn’t there and the market didn’t follow. They hoped the market would expand, but it hasn’t yet,” he states.

Audi’s decision to focus entirely on electric cars at its Brussels plant was equally misguided, in his view. “Audi had to build a completely new assembly line. Electric cars are much heavier than their internal combustion engine equivalents. The battery alone typically adds 500-600kg, so the floor in the factory had to be strengthened. In fact, they built a completely new building within the building – and only five or so years ago. It was a very big investment.”

Van Hoorick also highlights what he describes as long-term workforce issues at Forest. “I’m not surprised the factory is closing.

There were always problems there, with strikes being called for ridiculous reasons like a shortage of coffee. You never hear of union trouble at Volvo in Gent,” he adds.

Looking at the bigger picture, he predicts that Audi’s factories in Germany will also come under increasing competitive pressure. “Manufacturers prefer to close factories abroad first so they will keep plants in their home market open for as long as possible. Remember, the same happened with Renault at Vilvoorde. It was said to be the firm’s most efficient factory in Europe, but headquarters shut it rather than close plants in France,” he says.

Jude Kirton-Darling, general secretary industriAll Europe, a trade union federation, takes a different view. She insists a solution must be found to save the plant and avoid what she terms “destructive restructuring”.

While acknowledging that Audi was “slightly ahead of their time” and “bet on the wrong horse” when making the decision to transform its Forest site for EV production, she says it would be “wasteful to allow the plant to close and see everything stripped away.”

“If production capacity is lost, it’s a significant loss for Belgium more generally,” she warns, while taking issue with “liberal economists” who question the validity of subsidies.

“In my experience, if you’re trying to steer a transition to emission-free vehicles, you need an industrial policy that allows the stimulation of that transition. It’s naïve to think you can stimulate such a transformation and the massive cultural shift required without doing this,” she says.

To prove her point, she refers to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and its tax incentives to boost electric vehicle production. The 2022 law also benefitted the car sector in Mexico and Canada because they are part of a free-trade bloc with the US. “The IRA actually encouraged Audi to build its smaller A6 in

Mexico,” she adds.

A former member of the European Parliament, Kirton-Darling is scathing about what she sees as the lack of a continent-wide industrial policy. “What we’re seeing is the rhetoric of an industrial policy but with resources stripped away - and a return to austerity.”

She also criticises the EU law requiring all new cars to be zero-emission in just over a decade. “We’ve never taken a policy on a specific date, but a target without a plan will always fail. Without a plan, you don’t get to your destination. It’s like going on a journey without a map.”

The fourth expert is Brieuc Janssens, Brussels manager for Agoria, the Belgian federation of technology companies. Like the others, he is “unsurprised” by the developments at Audi.

“The context is tough – we see less and less manufacturing in Brussels. But we need to create jobs here which aren’t just in services or administration,” he says.

Janssens, who took part in recent hearings on the current crisis at the national

Parliament (Audi’s management was also invited but failed to attend), fears that it could be very difficult to find an investor who will come up with a satisfactory offer.

“It might be that the region will end up buying the plant,” he suggests. “This happened with the Ford site in Genk and Caterpillar at Charleroi which were sold for a euro. What we don’t want is to see the land sold off for housing. We need to keep manufacturing jobs in Brussels.”

In the case of Genk, the site was transformed into various units including logistics operations. It was “very dynamic, involved a lot of upskilling and saved jobs,” says Janssens. The initial regional ‘takeover’ at Charleroi was less successful with many jobs lost and the authorities have since decided to follow Genk’s example by splitting up the site and targeting the logistics sector.

For Janssens, the ideal long-term solution for Forest is a public-private partnership, based on a strategic plan that focuses on three priorities: industry (“retaining manufacturing jobs”), R&D (“creating more sustainable jobs”), and close links with high schools and universities (“to give opportunities to the young”).

Audi was founded in 1909 by German engineer and automobile pioneer August Horch, five years after creating a business he named after himself. In the early 1930s, Audi and Horch merges with DKW and Wanderer to form Auto Union, which uses four interlinked rings as its logo.

Richard Bruhn, a committed Nazi party member, is chairman of Auto Union from 1932-1945. Released from captivity after the war, he relaunches the business with support from the US Marshall Plan. (In 2014 Audi commissioned a study into Auto Union’s wartime record. It found the company worked with the SS to build seven camps where at least 3,700 prisoners were put to work. It also employed 16,500 forced labourers at its factories in Zwickau and Chemnitz).

In 1958, Daimler-Benz takes an 87% holding in Auto Union, increasing its stake to 100% a year later.

In 1964, Volkswagen acquires 50% of the business and relaunches the Audi brand.

The infrastructure for electric vehicles wasn’t there and the market didn’t follow. They hoped the market would expand, but it hasn’t yet.

In 1969, Auto Union merges with NSU Motorenwerke, creating Audi NSU Auto Union, which ultimately becomes Audi.

In 1970, Hans Bauer, a member of Audi’s advertising department, comes up with the slogan ‘Vorsprung durch Technik’ (Progress through Technology).

In 2015, Audi admits that at least two million of its cars are involved in the Volkswagen diesel emissions testing scandal.

Today Audi produces cars in many worldwide locations. In addition to Brussels, there are three Audi plants in Germany at Ingolstadt, Neckarsulm and Zwickau, and others in Mexico, Slovakia, Spain, Hungary, Spain, Russia, Brazil, India, and China (six locations).

What we don’t want is to see the land sold off for housing. We need to keep manufacturing jobs in Brussels.

In October, outgoing Prime Minister Alexander De Croo met management and union representatives, and called for a social plan to pro-

1948: Pierre D’Ieteren lays the first brick for a new car plant on the outskirts of Brussels. He signs a contract with Volkswagen to become its official Belgian supplier.

1949: The first car rolls off the assembly line, a Studebaker.

1954: The plant starts producing the Volkswagen Beetle.

1961: Among a roster of brands, the factory also assembles the Porsche 356.

1970: Volkswagen takes over the Forest plant. It produces its millionth VW Beetle.

1975: Pierre D’Ieteren and his wife die in a car crash – in his Audi.

1980: The plant starts producing the VW Golf.

2001: Production of VW Lupo begins.

2004: Production of the Audi A3 starts.

2005: Foundations laid for a state-of-the-art automotive park for supply and logistics. A bridge connects it to the production halls.

2006: Volkswagen moves VW Golf production at Wolfsburg and Mosel. Following a restructuring agreement, partly brokered by then-Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt, 2,200 jobs are saved in Forest as it is sold to Audi.

2007: Audi takes over the plant. It continues to produce the VW

tects Audi Brussels employees and suppliers.

Former Belgian Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo, now an MEP, made his views clear about the stark situation facing Audi Brussels in a question to the European Commission, co-signed by fellow socialist MEPs Estelle Ceulemans, former general secretary of the FGTB Brussels trade union Kathleen Van Brempt and Bruno Tobback.

It calls for “the preservation of jobs and production, and safeguarding and further developing of green innovative technologies and industry within Europe”, adding that the “reindustrialisation of Europe needs to go hand in hand with measures that encourage local manufacturing”.

The MEPs asked the Commission to spell out how it plans to prevent the closure or relocation of manufacturing sites crucial for sustainable transition and what incentives it will create.

At the time of writing, the Commission was yet to reply.

Meanwhile, back at the plant, spokesperson Peter D’hoore confirms that around 85% of Audi Brussels’ 3,000 employees have now returned to work. Of those, around 2,000 are directly involved in production. “We have two shifts working e ight hours. Our current target is for each shift to produce 12 cars per hour,” he says.

Asked what the mood is like among the workforce, D’hoore is surprisingly buoyant. “I have a positive outlook,” he insists. “We’re not at the end.”

Polo for two years.

2010: Start of production of the Audi A1, the first model to be made exclusively in Brussels.

2013: Commissioning of 37,000 square meter photovoltaic power plant.

2014: Celebrations to mark the 500,000th Audi A1 produced at Forest, with a visit by King Philippe.

2018: Audi e-tron, the brand’s first fully electric-powered SUV (sports utility vehicle), goes into production. Assembly of Audi A1 moves to Martorell (Spain).

2019: Expansion of automotive park and photovoltaic power plant.

2020: Audi e-tron Sportback in production. Audi Brussels receives ‘Factory of the Future’ award.

2021: Audi Brussels builds its 100,000th e-tron.

2022: Q8 e-tron and Q8 Sportback e-tron go into production.

2024: The first Q8 e-tron edition Dakar rolls off the production line. Thomas Bogus succeeds Volker Germann as Managing Director of Audi Brussels after it announces restructuring plan. Since the end of 2018, Audi has produced 250,000 electric cars in Brussels.

The World Health Organization’s Pandemic Agreement is a historic opportunity to reshape global public health, yet it risks falling into an outdated charity-based model if Europe and high-income nations continue to treat pandemic preparedness as an issue of North-to-South aid. True global health security requires collective resilience, not

dependency. As we enter the final phase of negotiations in Geneva this November, European leaders must recognize that a successful agreement must prioritize equitable access to life-saving technologies and resources for all countries. We cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the past.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine distribution was a glaring example of ineq-

uity. While countries like Germany, France, and the UK quickly secured vaccines for their populations, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Global South were left struggling. Over 85% of African nations were unable to provide even a single dose to their populations by mid-2022, while many Western European countries double-vaccinated more than 70% of their people. This imbalance led to unnecessary deaths, perpetuating a global divide where lives in the Global North were deemed more valuable than those in the Global South.

To break this cycle, the Pandemic Agreement must not just offer high-income countries the opportunity to donate surplus vaccines but actively support the creation of regional production hubs in the Global South. The future of pandemic preparedness should be built on shared resilience, with knowledge, technology, and resources flowing in both directions—not through charity but through partnership.

One of the most crucial aspects of the Pandemic Agreement is the commitment to ensure the transfer of knowledge and technology to LMICs. High-income countries, including many in the EU, have historically defended pharmaceutical companies' interests, which prioritize profit over public health. This defense of monopolies and intellectual property rights during crises has devastating consequences, as seen with COVID-19 vaccines.

For the Pandemic Agreement to be successful, it must include binding provisions for technology transfer, intellectual property sharing, and the establishment of local manufacturing in LMICs. Europe, as a leader in global health, must champion these commitments. If the current text remains focused on “voluntary” or “mutually agreed terms,” we will see the same inequities repeated, leaving the Global South dependent on handouts instead of being self-sufficient in the face of future pandemics.

The negotiations for the Pandemic Agreement have, thus far, been riddled with vague commitments and unenforceable promises. European leaders must push for clear, binding financial commitments from high-income nations. Voluntary contributions are insufficient to support the necessary infrastructure and health systems in LMICs. Article 20 of the agreement, which addresses sustainable financing, must include concrete obligations for European nations to contribute long-term, reliable funding for pandemic preparedness in the Global South.

Financing should not be viewed as charity but as an investment in global security. A pandemic that starts in one part of the world will inevitably spread. The COVID-19 pandemic showed that when one region fails to contain a virus, the entire world suffers.

Sustainable, predictable funding will help all countries prepare for and respond to future health crises, ensuring that no nation is left behind.

Europe is at a critical juncture. By leading the way in advocating for these changes, the EU can help redefine global health policy for the 21st century. Moving away from the outdated, paternalistic model of aid and charity to a model based on shared responsibility and equity will not only benefit the Global South but will also strengthen Europe’s own health security.

The stakes are high. The Pandemic Agreement is our chance to prevent the kind of vaccine hoarding, technological monopolization, and funding gaps that have left much of the world vulnerable. A global health crisis does not respect borders and neither should our response. Now is the time for Europe to demonstrate its commitment to equity by ensuring that the Pandemic Agreement prioritizes the needs of the Global South— not as an act of charity, but as a necessary step toward building a resilient global public health system that protects us all.

As the final negotiations approach, Europe must commit to equity as the foundation of this agreement. By supporting regional production hubs, transferring technology, and guaranteeing sustainable financing, the EU can ensure that the Pandemic Agreement does not simply reinforce old patterns of dependency but instead builds a robust, global response network. European leaders must push for a transformative agreement that leaves no one behind—because true global health security is only possible when every nation, regardless of income status, can stand on its own.

By Daniel Reijer, Ph. D., AHF Europe Bureau Chief

Financing should not be viewed as charity but as an investment in global security. A pandemic that starts in one part of the world will inevitably spread.

The team from 80 nations at Ghent’s Volvo plant is a factory of efficient ambition, producing a car every 79 seconds. From a storied past – with a deals sketched on a menu – to a future powered by zero-emission EVs, the Ghent facility remains a resilient outlier in Belgian car manufacturing. Lisa Bradshaw sees heritage meet high-tech

Lars sketched the design for the plant on the back of a menu.

Bikes whizz by as you wait at a pedestrian crossing. On the other side, you wave at your friends from all over the world. You pull on a cable above your head to play some music before stopping by a lunch stand. Finally, you are off to witness a “marriage” and go for a trim.

Sounds like a charming little village, right? In a way, it is. It’s the Volvo car manufacturing plant in Ghent, home to 6,500 workers made up of 80 nationalities. With a car rolling off the line every 79 seconds, it is run with an efficiency that most village mayors would envy.

Volvo Cars Gent has been running continuously since the first car – the Amazon – rolled off the belt in 1965. It was the second Volvo car manufacturing facility, and the first outside of Sweden.

“A young engineer, Lars Malmros, was sent to scout sites in Europe,” explains Pieter Philips, my tour guide at the colossal plant in the city’s harbour. “They visited Hamburg, Bremen, Berlin. They visited Antwerp and Rotterdam. They did not come to Ghent.”

Buoyed by the fact that an independent im-

porter was doing some light assembly of Volvo cars in Brussels, Ghent’s city councillor responsible for the port invited the engineer for a visit. As the story goes, there was an evening of wining and dining, and the question was asked: “What do you need from us to build this plant here?”

“Lars sketched the design for the plant on the back of a menu,” says Philips. “He said, ‘That’s what I want’. And they said, ‘OK, we’ll arrange it.’”

And they did. While Ghent is 30 km from the sea, its connection via the Ghent-Terneuzen canal and Scheldt river is solid. It had the road and rail connections and the technical schools it needed to make the new plant a success.

The Ghent facility operates 24 hours a day, five days a week in three shifts. Philips himself worked in the steel division at Volvo Cars Gent for more than 35 years until his retirement. Tours of the plant are often given by former workers because no one knows it better than they do.

Cars start out in the welding division, before moving to painting and then final assembly and trimming. In the assembly section, Pieter walks me past the wall of fame – models that have been cut in half from top to bottom and mounted high on the wall. Belts bring undercarriages past workers who grab tools and parts to perform various tasks. If they are missing a part, they pull a cord above their heads, which plays a specific piece of music, alerting the supervisor that help is needed.

Thousands of robotic arms of varying sizes do the heavy lifting and precision work, like placing the windshields. One of the most impressive feats in assembly is the joining of the body of the car to the undercarriage. It’s fully automated and referred to as “the wedding”.

Volvo Cars Gent – part of Volvo Car AB, now owned by China’s Geely Holding – is currently manufacturing the luxury crossover SUV XC40 (hybrid and electric) and the fully electric compact SUV EX40, as well as the crossover electric cousin EC40. The V60 hybrid body is manufactured in Sweden and sent to Ghent for painting and trimming. Ghent will also produce the fully electric subcompact EX30 starting next year. New Volvos are only built once sold to a customer, so workers might see an XC40 one moment, and an EC40 the next.

Defaming remarks and inappropriate suffering entertainment are omitted, because even the Swedish/Belgian subsidiary the Chinese Geely Holding knows from experience that these kinds of doom scenarios can just fall out of the blue. With an annual production of 230,000 passenger cars and a workforce of 7,000 employees, Volvo Ghent is currently one of the most important (and largest) employers in Belgium, but even that offers no guarantees, as the bankruptcy battlefield from the past teaches us.

The Chinese car conglomerate is already anticipating the high import tariffs for Chinese cars that the European Commission wants to introduce in the short term, ranging between 20 and 50 percent. China is competing in unfair competition by subsidizing its own manufacturers and supplying cheap raw materials, said Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who said she hoped to “be able to somewhat dam the overflow of over-subsidized Chinese electric cars. In response to that penalty levy, Volvo immediately announced that it would no longer build its new small electric SUV EX30 only in China, but also in Ghent. Volvo Ghent will still be able to benefit from the increased import tariffs in the coming years, but the decision to build the EX30 in Europe is completely independent of the increased import tariffs, according to Volvo CEO Jim Rowan. "We build our cars where we sell them and the Volvo EX30 is a greater success in Europe than in China." In the Belgian market alone, the mini-SUV caused a sales increase of no less than 30 percent.

Volvo Car Ghent was already the largest factory of the brand, but it goes without saying that the Chinese family expansion cannot be realized without heavy investments in capacity expansion and personnel.

How can people recognise a Volvo? Philips points to the taillights. “They’re shaped like Thor’s hammer,” he says.

One by one, car manufacturing plants in Belgium have shut their doors: Renault Vilvoorde in 1997, General Motors Antwerp in 2010, Ford Genk in 2014. In 2007, Volkswagen restructured the plant in Brussels to produce its Audi brand. And now Audi is in trouble.

Conversely, Ghent’s Volvo facility pumps out more than 230,500 cars a year – as many (and in some years more) as the headquarters in Gothenburg. Together the plants produce two-thirds of all the brand’s cars, despite there being four more manufacturing plants – one in the US and three in China. In the face of it all, Volvo Cars Gent isn’t just surviving, it’s thriving.

Which begs the question: Why? “Because of that,” says Geert Bruyneel, laughing and pointing to a large-scale photograph of a Volvo vehicle. I get his point. It’s the car, stupid.

We’re sitting in a conference room at the plant, which Bruyneel ran from 2010 to 2013. A Belgian, he joined Volvo in the 1980s as an engineer and has since worked from Sweden, Ghent and China, managing quality control and global supply chains. These days he’s back in Sweden acting as a senior advisor to the brand’s Scottish CEO.

But today Bruyneel is in Ghent to talk to me about what makes Volvo Cars tick.

“I have always said that there are two things

that are important,” he says. “We continue to invest in this plant to make sure it’s up to date and capable of launching new cars. You have to continue to be relevant to the company. This plant has always been a hub of highly competent people, both on the production lines and in engineering.”

He points to employee recruitment and development, which he sees as a crucial aspect of Ghent’s success. “More and more we are a tech company, so we have to recruit people with the right background - and of course we continue their development here. We stimulate this enormously, working to empower people to grow in their jobs, to take accountability and ownership.”

The second thing, he says, is location, location, location. “Belgium is an excellent hub for both trade and the supply chain. The majority of our customers are in Western Europe. And because we are close to the sea, we export to the US. We’ve benefitted from that since the beginning. With the disruptions that go on in the world, it’s important to have a low-risk supply chain.”

More and more we are a tech company, so we have to recruit people with the right background - and of course we continue their development here.

If you are not an industry

you cannot comprehend how strong that safety culture is. We continue to try to be a pioneer in that, and it is keeping us at the top of the pyramid.

All of Volvo’s new cars are either hybrids or fully electric, with the goal of producing only fully electric models by 2030. On the very day of my visit to the plant, receives – with much ceremony – the customer who bought the one-millionth XC40/EX40. It is the first time any Volvo plant has produced one million units of the same model.

Still, Volvo’s electric models are being outsold by Tesla and Volkswagen in the European car market. “We are producing premium cars,” says Bruyneel. “We’re not competing for the last euro. We are not trying to get the highest market share or the highest volume. We want to stick to the roots of our brand.”

A key factor in Volvo’s reputation is safety. In 1959, it invented the seat belt, handing out the design freely to other manufacturers. Each car contains 400 different kinds of steel – from crush-proof boron alloys to impact-absorbing crash steel – a high number for the automotive industry.

“We are pioneers in safety,” Bruyneel states, as he points to the future of self-driving vehi-

cles. “You really have to trust a car if you’re not driving it,” he chuckles. “That requires extreme confidence. We’re not there yet.”

The implication is that Volvo will get us there. “If you are not an industry insider, you cannot comprehend how strong that safety culture is. We continue to try to be a pioneer in that, and it is keeping us at the top of the pyramid.”

Considering Belgium’s strong union culture and the size of Volvo Cars Gent, the lack of industrial action is quite remarkable. So infrequent are labour disputes that everyone is still talking about the big three-week strike of 1978. “It was then that the foundation was laid for future labour negotiations,” explains Dirck Bogaert, one of Volvo’s ACV union representatives. “The CEO at the time made the firm decision to position unions as partners rather than the enemy. The idea was: No more strikes.”

Since then, conflicts have led to temporary work stoppages at most. According to Bogaert, this is because a typical top-down approach has been abandoned. Union members are in close contact with the board of directors, and decisions are made with their approval before they are implemented.

Even when Volvo sold the car division to Ford in 1999, and when Ford sold it to the Geely group a decade later, work continued as usual. “We were of course worried when the company was sold to the Chinese,” says Bogaert. “But it quickly became clear that they respected the way we operate. Nothing changed. Quite the opposite: Geely said to stay Volvo, to stay who we are.”

Bruyneel refers to this identity as well in explaining Volvo’s appeal. “There’s this Scandinavian heritage in design and materials but also this special thing, this mystery. It’s a kind of feeling in the brand. It’s more than just metal. You can’t copy that.”

It sounds a bit over the top. But the other evening, my partner and I were sitting at a traffic light. That’s a Volvo in front of us, I mentioned. It was too dark to see the logo, but I saw the taillights – shaped like Thor’s hammer.

From a modest Brussels workshop founded in 1805, the D’Ieteren family has grown its enterprise into a global powerhouse valued at over €10 billion. It now spans car distribution, glass repair, and even stationery, writes Ellen O’Regan

From humble beginnings in a Brussels workshop more than two centuries ago, the D’Ieteren family has grown its car-centred empire into an international success - and one of Belgium’s most valuable companies, worth over €10 billion.

Since 1805, the business has survived Napoleon’s march across Europe, Belgium’s independence revolution, two World Wars and, of course, the transformative arrival of the internal combustion engine.

At D’Ieteren Group’s headquarters on Rue du Mail in Brussels, a private showroom is filled bumper-to-bumper with glittering models.

The 2,300m² gallery floor showcases around 100 vehicles, from luxury horse-drawn carriages decked out in ivory and mahogany, to iconic motors like Studebakers and Volkswagen Beetles.

The gallery tracks not only how personal transport evolved through decades, but also how the D’Ieteren family adapted their business to survive.

“It’s the history of the family and the business, with the touch of art history to appreciate the pieces itself,” explains gallery curator Danaë Vermeulen, as we begin the tour that she usually gives to visiting car fanatics, motor clubs and companies.

The family business has been handed down from father to son for seven generations, with each new era for the business bringing its own trials and triumph (the D’Ieteren women also “did interesting things”, Vermeulen says, adding that she hopes to someday give them greater prominence in the telling of the family and company history).

Jean-Joseph D’Ieteren started in 1805 making wooden wheels at a central Brussels workshop on Rue de Marais, for both car-

riages and bicycles, catering to the busy passing trade on the nearby Allée Verte along the canal.

Step by step, the ambitious wheelwright worked his way up to crafting full wooden carriages, pouring his heart into a Tilbury wooden model that was showcased at the ‘Exposition generale des produits d’Industrie’ held in Brussels in 1830.

“It was a success. We have the newspapers that were very positive about his project,” explains Vermeulen as we pass a replica of the meticulously crafted wooden carriage.

Unfortunately for Jean-Joseph, praise for his model did not convert into sales. The following month, Belgium was upended by its independence revolution, and he would die shortly after, in January 1831, aged 45.

After his death, Jean Joseph’s two eldest sons took over the business. Guillaume continued to run the workshop, while Alexandre went to Paris to study design and absorb Parisian good taste. With the Belgian economy picking up, the brothers began to craft luxury carriages for the country’s burgeoning upper classes.

The family moved the workshop to Chaussee de Charleroi in Saint-Gilles in 1873, and shortly after, Alexandre’s sons Alfred and Émile took over the business, renaming it D’Ieteren Frères.

These brothers “take the business to the next level” according to Vermeulen, landing a contract to supply and maintain carriages for the Belgian Royal Family in 1887, and spearheading the move from horses to horsepower.

As the automobile business picked up

Unfortunately for Jean-Joseph, praise for his model did not convert into sales. The following month, Belgium was upended by its independence revolution, and he would die shortly after, in January 1831, aged 45.

To cater to rapidly growing demand, D’Ieteren built a production plant in Forest in Brussels, next to a Citroën factory, with the first car assembled there in 1949, a Studebaker.

around the turn of the century, the D’Ieteren family used their coachbuilding expertise to build the bodies for luxury cars. While some carmakers supplied a finished product, others just manufactured the engine and chassis, leaving customers to find a coachbuilder to ‘equip’ their car according to their desires.

D’Ieteren was ideally placed for these commissions. They delivered their first car body to Belgian race car driver Camille Jenatzy in 1897, before relocating to a new workshop at Rue de Mail in Ixelles (where it is still based to this day, although in modernist 1960s offices), to expand and keep up with orders.

D’Ieteren would spend more than 30 years in the luxury bodywork-making business, equipping chassis from 105 different brands including Minerva, Renault, Rolls-Royce and Mercedes. The transition to motor power at the beginning of the 20th century continued despite grumblings from more traditional

Belgian customers about the move “de la voiture à crotin à la voiture à potin” (from horse manure to exhaust fumes).

However, the First World War, followed by the Great Depression, hit demand for luxury vehicles: staff numbers dwindled from 500 to 73, and D’Ieteren had to find a way to diversify its business.

Lucien, the grandson of Alfred, took over the company, renaming it Anciens Établissements D’Ieteren Frères.

In 1931 D’Ieteren secured a contract to import American car brands Studebaker, and Piece and Arrow, joined by Auburns in 1934. The last luxury bodies crafted by D’Ieteren left the factory in 1935, as the family turned instead to shipping American cars into Antwerp.

When European import taxes on completed cars began to eat into margins, D’Ieteren rejigged their Rue de Mail workshop to assemble the vehicles in Belgium, using as many local Belgian suppliers as possible.

“The fewer pieces that had to come from America the better. That’s how they kept the cars accessible – and they were very popular cars. It wasn’t luxury like we had before, and the demand was so high that producing in the workshop wasn’t enough,” says Vermeulen.

To cater to rapidly growing demand, D’Ieteren built a production plant in Forest in Brussels, next to a Citroën factory, with the first car assembled there in 1949, a Studebaker.

By the mid-20th century, the idea of the mass-produced popular car was beginning to take off, and the company signed a pivotal contract with Volkswagen to bring the German car brand to the Belgian market. The factory's activities evolved with the assembly of VW’s iconic Beetle, as well as the Transporter, the Karmann Ghia and even the Porsche 356.

D’Ieteren also ventured into the car rental market in the 1950s, offering the option for visitors to rent a Beetle which they could collect at the airport or train station in Brussels. And by the 1960s, the company branched out into insurance, financing and car rental.

There were bumps in the road. Studebaker ceased trading in 1965, Congo gained independence from Belgium in 1960 and subsequently nationalised D’Ieteren’s operations there, and the Forest factory had to be radically overhauled to make the VW Golf.

“The Beetle was a very simple car to produce,” Vermeulen explains. “The Golf was much more modern and complicated, so you needed different machinery.

In 1970, some 22 years after it was built and a few months before the millionth Beetle made in Belgium left the plant, Lucian’s son Pierre sold the Forest factory to Volkswagen.

Treat yourself or a loved one to the ultimate gift: a relaxing day at the sauna, away from the pressure of everyday life. It’s the perfect way to recharge and enjoy pure luxury. Until December 31, 2024, receive a free day pass with every €100 in gift vouchers purchased. Gift vouchers are available both online and on-site.

However, the company is keen to show that it is much more than a car importer and distributor. Next to its flagship offices on Rue De Mail, the huge ground floor showroom that once exhibited Volkswagens and Audis is now Lucien, a shop selling bicycles.

“Losing the Congo business, and having to modernise the factory, the bank wasn’t very happy,” says Vermeulen. “Pierre had to make the difficult decision to sell the factory. Apparently, he really cried. That was the end of the industrial activities of D’Ieteren.”

After the death of Pierre in a car accident in 1975, his son Roland D’Ieteren took over the family business. A “car maniac”, according to Vermeulen, during college and his early career Roland tinkered with race car body designs anchored on VW Beetle engines.

He also began to diversify the family business, gaining a controlling interest in car