MAGAZINE No 55

Summer 2024

A funky jazz mix of Congo, Expo 58 and spies

Is it revolution or restoration at Place Royale?

Finance Minister Van Peteghem tries to balance the books

MAGAZINE No 55

Summer 2024

A funky jazz mix of Congo, Expo 58 and spies

Is it revolution or restoration at Place Royale?

Finance Minister Van Peteghem tries to balance the books

Special issue ahead of Paris 2024: The Red Lions hockey squad, Belgian Tornadoes relay team, Nina Dewael, Nafi Thiam and other hopefuls

Plus: When Antwerp hosted the Olympics, the Red Devils at Euro 2024 and Belgium’s niche sports

For connoisseurs of the finer things in life and those who enjoy chilling in style! Come, spend some time here and your heart is sure to smile!

Gloriette Guesthouse is located on Bolzano’s well loved local mountain. Once you arrive in Soprabolzano in Renon, whether it be by cable car or by car you will find yourself in another world. It is much more than just first-class comfort which makes each of the 25 rooms special. It is instead the little things, the casual accessories together with a touch of luxury that create an easy-going, overindulgent flair. You also experience this feeling when you dive into the rooftop infinity pool or while having a wonderful meal in the fine dining restaurant of the hotel.

6-9th of June –European elections

Belgium’s national teams are usually red. Or cats. Or both.

The men’s football team is the Red Devils and the women’s is the Red Flames. The men’s hockey team, the current Olympic champions, are the Red Lions, and the women are the Red Panthers. The women’s basketball team is the Belgian Cats, while the men are the Belgian Lions. The men’s 4x400m relay team breaks the theme: they are the Belgian Tornadoes. But the women’s relay runners are back on message as the Belgian Cheetahs.

One might ask what is particularly Belgian about tornadoes – or even lions and panthers. But when you compete at the highest level, you sometimes need to suspend disbelief to imagine yourself winning.

This summer, there is sport galore, and Belgium is very much in the mix. Team Belgium will send over 135 eager competitors to the Paris Olympics, all hoping for their moment of glory, and Isabella Vivian joins me to look at the medal prospects of the fittest and finest.

I also meet Dylan Borlée, who is taking part in his third Olympics as part of the medal-chasing 4x400m relay team. Running runs in the family: his sister and twin brothers are also Olympians. And David Labi meets Belgium’s hockey coach, Michel van den Heuvel, as the Red Lions defend their gold medal.

Belgium’s Olympic credentials go beyond its sports stars: Antwerp actually hosted the games in 1920. It was in the most inauspicious circumstances, less than two years after the end of the First World War, but as I relate, the city pulled it off. And from jeu de balle to gullscreeching, Harry Pearson celebrates the uniquely Belgian games that have yet to be accepted as Olympic events.

Moving to football, Dennis Abbott meets Belgium’s coach Domenico Tedesco, ahead of Euro 2024 to see if the Red Devils can pull it together this time. Jon Eldridge visits Kraainem Football Club, which is bringing young unaccompanied refugees into its squad and helping them take their first steps in the country.

Dennis Abbott also meets Finance Minister Vincent Van Peteghem, who is battling to balance Belgium’s books while spending more on defence and welfare. Philippe Van Parijs says Brussels needs new language rules to reflect how French and Dutch, the city’s two official languages, are spoken less while English is on the rise.

We have four articles tied to Belgium’s mid-century meddling in its African colonies, Congo and Rwanda. Maïthé Chini speaks to Johan Grimonprez, director of Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, about how jazz stars were sent to Congo and other African countries during the independence era to distract from the political turmoil.

Susan Williams, author of White Malice, recounts how Expo 58 became a hive of Cold War intrigue as the CIA worked to undermine Congo’s independence efforts. Richard Harris tells of how he discovered his own father was a CIA agent heavily involved in Expo 58. And as Rwanda commemorates 30 years since the horrendous 1994 genocide, Thimoté Bozzetto explains how the internecine rivalries were partly a legacy of Belgium’s colonial rule.

As Place Royale’s cobbles are pulled up for a major renovation, Frédéric Moreau looks back at its rich history and forward to its bid to become a more people-friendly space. Frédéric also remembers the modernist pioneer Stanislas Jasinski, whose far-sighted vision for modern urban dwelling is recognised at a CIVA exhibition.

Margherita Bassi meets the Flemish designer and Moroccan artist whose wool creations aim to revive a lost craft. Angela Dansby takes a weekend break to Dinant, the Instagram-friendly town between the river and a sheer cliff face, which was the birthplace of Adolphe Sax.

Jon Eldridge cycles between the two Trappist breweries in Flanders, the abbeys of Westmalle and Westvleteren. Hugh Dow takes tram 9 from Simonis to the King Baudouin Stadium – and also tests the section to Groot-Bijgaarden, which the 9 is set to cannibalise from July.

Breandán Kearney relates how Mechelen’s Het Anker became one of Belgium’s most pioneering breweries. Hughes Belin writes about the filet américain as it celebrates its centenary, as well as the Au Vieux Saint Martin restaurant that created it. And finally, Geoff Meade grapples with artificial intelligence, currently threatening his identity as a professional chit-chatterer.

Leo CendrowiczEditor, The Brussels Times Magazine

Summer 2024

The Brussels Times Avenue Louise 54

1050 Brussels

+32 (0)2 893 00 67

info@brusselstimes.com ISSN Number: 0772-1633

On the Cover Illustration by Lectrr

Editor Leo Cendrowicz

Publishers

Jonadav Apelblat

Omry Apelblat

Graphic Designer Marija Hajster

Sales Operations Managers

Caroline Dierckx

Gidon Tannenbaum

David Young

Contributors

Dennis Abbott, Margherita Bassi, Hughes Belin, Thimoté Bozzetto, Leo Cendrowicz, Maïthé Chini, Angela Dansby, Hugh Dow, Jon Eldridge, Richard Harris, Breandán Kearney, Lectrr, Helen Lyons, Geoff Meade, Frédéric Moreau, Philippe Van Parijs, Harry Pearson, Isabella Vivian, Susan Williams

Photo Credits

Lectrr: Cover, 144

Belga: 8-11, 16, 17-18, 20, 24, 26, 28, 32, 34, 36, 42, 52, 54-56, 62-67, 82-83, 85, 87, 132 Louis David at louisdavidphotography. com: 14-15

Province de Liège-Musée de la Vie wallonne: 48, 50-51

Kraainem Football Club: 60-61

Leo Cendrowicz: 68, 80, 90, 93, 116-121

123RF: 88-89, 96, 145-146

Angela Dansby: 108-112

Westmalle Brewery: 122, 124

Sint-Sixtus Abbey: 126

Breandán Kearney: 128-134

Correction

In the Apr/May issue we mistakingly wrote that Belgian elections were due on June 7, whereas it was in fact on June 9.

Advertising

Please contact us on advertise@brusselstimes.com or +32 (0)2 893 00 67 for information about advertising opportunities.

62

16

Belgium’s Olympic dreams

Leo Cendrowicz and Isabella Vivian

24 Sticking with gold

David Labi

32 The relay baton passes to Dylan, the last Borlée brother

Leo Cendrowicz

40 When the Games were in Antwerp

Leo Cendrowicz

48 The brilliant Belgian sports that the Olympics ignored

Harry Pearson

52 Red Devils seeking a reboot at Euro 2024

Dennis Abbott

60 The football club seeking refugee players

Jon Eldridge

62 The numbers man balancing Belgium’s books

Dennis Abbott

68 Why Brussels needs new language rules

Philippe Van Parijs

74 How jazz played out over Congo’s chaotic coup

Maïthé Chini

80 Undercover at the Expo: The CIA's secret mission in Brussels

Susan Williams

84 Expo 58 and my father’s CIA secret

Richard Harris

86 The Belgian seeds of Rwanda’s genocide

Thimoté Bozzetto

88 Royale revival

Frédéric Moreau

The artists finding ways to revive Belgium’s fading wool traditions

Margherita Bassi

The Brussels starchitect that nobody knows Frédéric Moreau

Down to Dinant

Angela Dansby

Tram 9, from Simonis/ Elisabeth to King Baudouin

(and, eventually, to GrootBijgaarden)

Hugh Dow

122 A double Flemish Trappist

beer bike tour

Jon Eldridge

128 Ankerman and the legend of the moon extinguishers

Breandán Kearney

136 Food and drink

Hughes Belin

140 Arts & events

Helen Lyons

Geoff Meade 32 84 88

144 Hey there, what’s up? How can I brighten your day today?

It was a purrade to remember at the Kattenstoet, the cat-themed festival held triennially in Ieper (or Ypres) on the second Sunday of May. Ieper’s relationship with cats has taken many forms. In pagan times, a giant statue of a cat god is thought to have stood where the Cloth Hall is currently in the town centre. But the cat worship turned when locals converted to Christianity and furry friends were associated with witches and demons. Records from the 15th century reveal the festivals were far from fun for felines: the town jester would hurl live animals from the high towers –including the Cloth Hall belfry – to symbolise the exorcism of demons. Only in 1817 were the last cats thrown and the practice banned. Now, there is only applause for the paws.

It is as rare as it is stinky. The titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum) usually takes years to flower, but the Botanical Garden in Meise boasts a remarkable record in fostering them: this year was the 17th time that the plant has bloomed in Belgium. It also has the largest unbranched inflorescence in the world. However, the size and infrequency are not the only reasons titan arum draws crowds. It also gives off arguably the foulest stench nature can produce, akin to rotting flesh. The funky flora is native to rainforests on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, where locals call it the ‘corpse plant’. The one whiffing up the Meise greenhouse in May was 217cm tall – but the flowering lasted only 72 hours.

Pierre and Jennyfer from Drogenbos made a very deep commitment in May when they tied the knot at a diving centre in Limburg. By all accounts, the aquatic wedding went swimmingly.

Belgium will send its biggest-ever team of sporting hopefuls to the Olympic Games in Paris in July and August. Leo Cendrowicz and Isabella Vivian look at their medal prospects

They are Belgium’s fittest and finest. They are heptathletes and hockey players, sailors and swimmers, boxers and basketball players, cyclists and canoeists, triathletes and taekwondo fighters. And they are heading to Paris to test their speed and strength against the greatest in the world in that quadrennial festival of sports, the Olympic Games.

When the Belgian squad marches out in the Stade de France for the July 26 opening ceremony, they will be hoping to seize their glorious moment.

Over 135 eager sportspeople will be competing in Paris this summer. “We have a fine delegation of athletes performing at the highest level," says Jean-Michel Saive, President of the Belgian Olympic Committee. “The team will be bigger than it was in Tokyo.”

Team Belgium won seven medals at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. In Paris, they have a well-stocked team featuring three Tokyo gold medallists: gymnast Nina Derwael, heptathlete Nafi Thiam and the Red Lions hockey squad. They will be bolstered by the Belgian Cats women’s basketball team, the Belgian Tornadoes 4x400m men’s relay runners, as well as world names like cyclist Wout van Aert.

“We are going into these Olympics with our heads held high. We are a strong delegation with lots of ambition. We will experience some incredible moments of emotion during the Olympic and Paralympic Games,” Saive says.

The qualification period for the Paris Olympics ends on June 30, so the final list is still to be determined. But here is what to watch out for from Team Belgium.

Let’s start with Belgium's brightest star, heptathlete Nafi Thiam, who clinched gold in both Rio 2016 and Tokyo 2020. The child of a Senegalese father and Belgian mother, born in Brussels and raised in Namur, she spent years as a teenager getting the train from school to go training in Liège before

returning to her home. She would later juggle athletics with studying geography at the University of Liège (specialist subject: the city sprawl in the sub-Sahara). Now 29, she is aiming for a heptathlon hat-trick in Paris.

There will be four Belgians in the triathlon: Jolien Vermeylen and Claire Michel for the women, with Jelle Geens and Marten Van Riel (fourth place in Tokyo) for the men.

In running events, the qualified women include Cynthia Bolingo in the 400m, Hanne Claes in the 400m hurdles and marathon runners Chloé Herbiet and Hanne Verbruggen.

Among the male runners, Bashir Abdi (who won bronze in Rio in 2016), Koen Naert and Michael Somers are competing in the marathon, Tibo De Smet and Pieter Sisk in the 800m, Alexander Doom in the 400m, John Heymans and Isaac Kimeli in the 5000m, and Michael Obasuyi in the 110m hurdles. On the field, Ben Broeders has qualified for the high jump.

Finally, there are the 4x400 relay teams. The men’s team, the so-called Belgian Tornadoes, includes Dylan Borlée, Alexander Doom, Jonathan Sacoor and (see interview with Dylan Borlée on page 28). The women’s relay team, the Belgian Cheetahs, came seventh in the Tokyo final in 2021 but had not yet secured their qualification at the time of writing. However, the mixed 4x400m relay, which came fifth in Tokyo, will be in Paris.

The women’s team, the Belgian Cats, have qualified and will hope to win Belgium’s first-ever Olympic medal in basketball. This is only the second time the Cats have qualified, after Tokyo, but they have gained ground, coming fifth in the 2022 FIBA World Cup and winning the 2023 EuroBasket Women.

Bucharest-born Vasile Usturoi has qualified in the men’s featherweight (under 57 kg) category, while Roesselare’s Oshin Derieuw

The child of a Senegalese father and Belgian mother, born in Brussels and raised in Namur, she spent years as a teenager getting the train from school to go training in Liège before returning to her home. She would later juggle athletics with studying geography at the University of Liège.

Wout van Aert, a triple winner of both the World Championships and World Cup, is one of the favourites in the road race, where he won silver in Tokyo, and time trial.

will compete in the women’s welterweight (under 66 kg).

Two-time European bronze medallist Artuur Peters will compete in his third Olympics in the canoe sprint K-1 1,000m. while Lize Broekx and Hermien Peters, in the women’s K2 500m sprint, already booked their ticket to Paris last summer.

Belgium has a rich cycling heritage and the squad in Paris has a good chance to add to its 27 Olympic cycling medals.

Wout van Aert, a triple winner of both the World Championships and World Cup, is one of the favourites in the road race, where he won silver in Tokyo, and time trial. Remco Evenepoel is also vying for both the road race and time trial: the 2022 Vuelta a España winner and 2022 UCI Champion will, like van Aert, also be competing in the Tour de France just before the Olympics.

World champion Lotte Kopecky will not be racing at the Tour de France Femmes so she can focus on the Olympics, where the 28-yearold from Rumst is a favourite for the individual time trial and road race.

Meanwhile, Jens Schuermans has qualified for his third Olympics in men’s mountain bike.

Historically, one of Belgium’s strongest sports, but in Paris their only hopeful is Neisser Loyola in the Sword category.

All eyes will be on Nina Derwael, Belgium's first-ever Olympic gold medallist in gymnastics, whose innovative routines have significantly raised the profile of the sport, inspiring a new generation of athletes. The Sint-Truiden-born gymnast, now 24, started at the Topsportschool in Ghent at age 11, and by 15, he had already won her first Belgian senior title. At 16, she made her debut at the 2016 Rio Olympics, finishing 19th, and the next year was crowned European champion. More medals and titles followed, culminating in her Tokyo triumph. Recently dogged by a shoulder injury, Derwael had to drop out of the World Gymnastics Championships in Antwerp last September, later undergoing surgery that sidelined her for three months. While she won gold in Tokyo for the uneven bars, in Paris she has qualified for the all-around – where she is joined by Maellyse Brassart.

Amongst the men, Luka Van den Keybus will compete in the all-around, alongside Noah Kuavita, who has also qualified for the parallel bars.

The Belgian men's hockey team, known as the Red Lions, secured the gold medal in Tokyo 2020 following their first World Cup title in 2018 (see separate article page 20). With a core of experienced players and a smart tactical approach, they are naturally aiming to defend their Olympic title.

The women’s team, the Red Panthers, will be at the Olympics for only the second time after London in 2012, when they came 11th. But their recent form has been impressive: silver medallists in the 2023 EuroHockey Nations Championship and fourth place in the past two seasons in the FIH Pro League.

In equestrian sports, Belgium has a solid base to build on, winning bronze in the team jumping in Tokyo, and this year, they have strong contenders in dressage, eventing and jumping. The likes of show jumpers Jérôme Guéry and Gregory Wathelet have consistently performed well in international competitions and will be

All eyes will be on Nina Derwael, Belgium's firstever Olympic gold medallist in gymnastics, whose innovative routines have significantly raised the profile of the sport, inspiring a new generation of athletes.

joined by Gilles Thomas and Koen Vereecke. Cyril Gavrilovic, Lara de Liedekerke, Jarno Verwimp and Karin Donckers will be in the eventing team, while Larissa Pauluis, Charlotte Defalque, Flore Winne and Domien Michiels will compete in dressage.

Judo is one of the disciplines where Belgium has brought home the most Olympic medals, some 13, including two golds: Ulla Werbrouck in the women's half-heavyweight (72kg) in 1996 and Robert Van de Walle in Moscow in 1980 for half-heavyweight (95kg). In 1996, four of Belgium’s six medals were in judo.

The best hope in Paris is Matthias Casse, who won bronze in Tokyo in the 81kg category and was World Champion in 2021. Toma Nikiforov, who was European champion in 2021 and 2018 in the 100kg, may see Paris as his last Olympic challenge.

Belgium can boast Tim Brys in the single sculls as well as the duo Niels Van Zandweghe and Tibo Vyvey in the lightweight double sculls.

The biggest medal chance is with Ostend-born Emma Plasschaert, a two-time World Champion, in the Laser Radial class, who finished fourth at the Tokyo Olympics. William De Smet is also in the Laser Radial, while duo Isaura Maenhaut and Anouk Geurts will be in 49er FX event.

Lucas Henveaux will swim the 400m freestyle at the Paris Games, while Valentine Dumont has qualified in both 200m and 400m freestyle, Florine Gaspard in 50m freestyle and Roos Vanotterdijk is in the 100m backstroke.

Sarah Chaâri, the 2022 World Champion, will compete in the middleweight 57-67kg. A 19-yearold medicine student at the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), she was also crowned European Champion in Belgrade in May.

Nina Sterckx, 21, has qualified in two categories for the Paris Olympic Games: in the under-49kg (seventh in the Olympic qualification ranking) and under-59kg (tenth). In Tokyo in 2021, aged just 18, Sterckx finished fifth and set a new Belgian record (180kg: 81kg in the snatch and 99kg in the clean and jerk). At the time, to be able to make the category, she had to lose 9.5kg, or 16% of her normal body weight.

Belgium took part in the inaugural 1896 Athens Olympics and has mostly been a fixture since then. Here are some nuggets in numbers.

157

Total medals won by Belgium in summer Olympics (44 gold, 56 silver, 57 bronze)

8

Total medals won by Belgium in winter Olympics (2 gold, 2 silver, 4 bronze)

27

Medals in its most successful summer sport, cycling. Followed by archery (21), athletics (14), equestrian (14) and judo (13)

30

Belgium’s place in all-time summer Olympics medals list

Advocates from the SOS: Save Our Society campaign urge World Health Assembly Member States to negotiate and adopt an equitable Pandemic Agreement that protects all nations at a press conference in Jakarta, Indonesia on May 27, 2024

The renowned scientific journal Nature estimated that vaccine hoarding alone likely costs more than 1 million lives.

After years of back-and-forth talks on how to best protect the world from the next pandemic disaster – World Health Organization

Member States remain at a stalemate – with lower-income countries still lacking access to lifesaving health commodities and the ability to secure vital technologies and know-how during global public health emergencies—issues world leaders must rectify immediately.

As the 77th World Health Assembly (WHA) convened this year in Geneva, there was much anticipation as to the fate of the WHO Pandemic Agreement. For the last two years, Member States have been engaged in negotiations to create an agreement to prevent a repeat of the COVID-19 global health catastrophe – a human tragedy that is less about a virus and more about nationalist protectionism, corporate profit interest, and unacceptable inequity.

In December 2021, after the omicron variant was first identified by South Africa and Botswana, Member States voted to establish an Intergovernmental Negotiation Body (INB) to draft and negotiate a Pandemic Agreement. From the start, addressing equity has been a priority for countries, with calls for equity initially being made even among those countries responsible for many of the very inequities observed during the global COVID-19 response

While initially seeming committed to being guided by noble objectives, European Union nations and the UK have since taken a stance of opposition against proposals aimed at breaking down intellectual property and other barriers to the equitable distribution of vaccines and other pandemic-related health products. This stance has caused an impasse in negotiations, and on the Friday before the assembly, it was announced that countries had failed to reach an agreement by its pre-established deadline of May 24. This, in spite of the fact that, as reported by legal scholars Alexandra Phelan and Lawrence O. Gostin, that “most of the draft treaty text was ‘greened’, meaning it was accepted by the parties.”

During discussions on the INB, which took place at WHA on Wednesday, representatives from Brazil pointed out that financing and equity are the key issues preventing the agreement. This isn’t surprising considering the stated position of powerful Western countries like Germany, whose Health Minister announced at the World Health Summit last year that an “agreement with ‘major limitations’ on intellectual property rights protection will ‘not’ fly for Germany and most of its European Union members.” This announcement was reported and described by Health Affairs, the leading journal of health policy research, as “a victory for the pharmaceutical industry, which has been lobbying hard to influence negotiations.” We agree.

For developing countries, the establish-

ment of binding mechanisms to ensure equitable access and prevent what South Africa has called a “vaccine apartheid”—referring to the rampant hoarding of vaccines, medicines, and other countermeasures by developed countries—has been a top priority. Preventing this from happening again requires nothing less than a binding agreement that specifically addresses critical issues of access and distribution of pandemic-related health products, tech transfer, regional diversification of manufacturing, and financing for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to build capacity and bring their health systems into the 21st century.

The renowned scientific journal Nature estimated that vaccine hoarding alone likely cost more than 1 million lives – 1 million. This is equivalent to wiping out 10 out of every 12 Brussels residents in under two years. In the same article, Nature reports on the stark contrast of such inequity with vaccine rates, which were 75% in high-income countries but less than 2% in some low-income countries.

However, equitable distribution of vaccines only solves part of the problem. Broader access to pandemic-related health products must be guaranteed to prevent the developing world from being “forced to be part of an unequal fight” for access to pandemic-related health products such as personal protective equipment, diagnostics tests, medicines, biologics, and even oxygen. To address this issue, Article 12 of the Pandemic Agreement sought to improve access by creating a Pathogen Access and Benefits Sharing System.

Under PABS, all signatories to the agreement would be required to rapidly share pathogens and genetic sequence data, which are critical for the timely development of diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics, with the understanding that participating countries will set aside a certain percentage of health products for equitable distribution to meet the urgent needs of all nations. During negotiations, an agreement could not be reached regarding percentages and triggering events for the distribution of these products, with a proposed best-case scenario of 20% of pandemic-related health products (10% as donations and 10% to be sold at cost). World-leading scientific journal The Lancet described the proposal as “shameful, unjust, and inequitable.”

At best, this proposal would leave 80% of critical vaccines, treatments, and diagnostics inaccessible to LMICs, which comprise 81% of the world's population, which can hardly be described as equitable. Achieving a PABS on equal footing requires real-time access to a sufficient amount of pandemic-related health products, not only during pandemics but also during Public Health Emergencies of

International Concern and during peacetime for prevention and preparedness.

It is clear that ignoring lessons from our past is done at our collective peril and, as put by AHF President Michael Weinstein, this missed opportunity to address systemic inequality in the global public health order by “giving in to pressure from corporate interests and profit motives at this point is beyond foolish.”

And while preventing infectious disease outbreaks or pandemics from disproportionally ravaging lower-income countries is not an exclusive concern of the Global South, the resolve to find a solution does not appear to come from what WHO Director-General Tedros has called “the Spirit of Geneva.” This is why these future negotiations should be moved to the heart of where equity matters most – to a developing country. This should be done without delay and be concluded before the end of 2024.

The longer we wait, the less pressure and resolve there will be for countries to reach a meaningful agreement on equity. As pandemic amnesia sets in, the odds are greater that countries will fail to take decisive action, ensuring we will again blindly stumble into our next global public health catastrophe.

Guilherme Ferrari Faviero, Director, AHF Global Public Health Institute at the University of Miami

Dr. Jorge Saavedra, Executive Director of the AHF Global Public Health Institute and AHF Mexico

As pandemic amnesia sets in, the odds are greater that countries will fail to take decisive action, ensuring we will again blindly stumble into our next global public health catastrophe.

The Red Lions aren’t sleeping tonight. As Belgium’s men’s hockey players prepare to conquer the Paris Olympics, David Labi spoke to their coach, Michel van den Heuvel

Tokyo Stadium, August 5, 2021. Seconds thud by, the tension hanging in the humid Japanese summer air. The Belgian men’s field hockey team is locked in a 1-1 draw with Australia to clinch the nation’s first-ever Olympic Gold in the sport. The referee blows his whistle for time –it’s penalties!

Years of patient work back home have brought the Red Lions to this moment. Now, all will be decided by a few flicks of the stick.

The black-clad Vincent Vanasch is imperious in the Belgian goal. He advances on the approaching Australian, gets down – it’s a block! The Kookaburras lose the upper hand. Florent van Aubel responds with poise, spinning around the keeper to slot home. Tension ratchets up, a mass intake of breath with each dice roll. Finally, the pressure is on the Kookaburras to do or die. The Belgian goalkeeper is penalised for impeding the player. There’s a retake – but Vanasch saves again and sends Belgium into history.

Gold at the pandemic-delayed 2020 Olympics was the third of a tremendous treble, after the World Cup in 2018 and the European Championship in 2019. Stepping down after the Games, head coach Shane McLeod could scarcely wrap his head around it. “Such stories are not written,” he said. “Nobody believes it.”

Three years on, we believe. Under new head coach Michel van den Heuvel, the team has continued to dine at the top table. In January 2023 they lost out to Germany in the final of the Hockey World Cup, and now the question is whether they can retake the Olympic Gold. With Paris approaching, Van den Heuvel sat down to talk trajectory, squad, strategy and how they plan to defend the podium. Will the Lions roar again?

Belgium was never seen as one of the giants of men’s field hockey. Indeed, the team has only won three medals in the Olympics, one

of each, compared to 12 by the most successful hockey country, India.

The Belgian journey to the Olympian summit was fired by heartbreak. At the 2016 Rio Olympics, they fell at the last hurdle, with silver serving as a potent reminder. In 2015, both New Zealander Shane McLeod and Dutchman Van den Heuvel had been approached. Van den Heuvel had other commitments and joined as assistant, but they’ve been working together, in one role or another, ever since –and McLeod remains on board as assistant today.

Van den Heuvel says they match well. “I'm more demanding and direct,” he says, “bringing a bit of that Dutch culture into my coaching.” This directness is balanced by McLeod’s focus on explanation and individual attention. “We’re really complimentary,” Van den Heuvel continues. “Over the years we’ve got to know each other inside out.”

Their blend permeates the team’s strategy. For example, man-to-man marking has been the traditional norm in Europe, with zonal defending more widespread in the rest of the world. McLeod cut his teeth in the zonal system, with Van den Heuvel coming through man-to-man. The team benefits as a result.

“When you play European teams against the US, India, and so on,” says Van den Heuvel, “we can understand the philosophy of both.”

But the true foundations of success came from Belgium’s decision around 15 years ago to invest in hockey. They built youth programmes, invested in quality coaches and steadily pushed targets. First, the goal was to compete at the Olympics, then to “push to the podium.” In Rio, they reached the final but lost to Argentina, and Van den Heuvel says the pain they felt represented “the vitamins we needed to make that extra step towards Tokyo.”

A virtuous circle was set in play, a self-nourishing structure. Younger players now had successful older role models. “We changed

They need to have the engine, and the capacity and mental ability to perform in a series of games.

With every big event you need to look for the changes you need to be successful. The better the players, the more they can enact tactical changes in big tournaments.

our mentality,” says Van den Heuvel. “We had these athletes investing a lot, but who hadn’t yet won. They made the team that was able to get that treble.”

Gold in Paris will hinge upon team selection, but at the time of writing, the final 16-man squad is yet to be announced. The Red Lions are currently competing in Pro League games in Belgium and the Netherlands against India and others, while the coaches evaluate.

In the last Euros, they had time to blood some newbies, forging “a new group of young and old together, hungry again.”

You need balance, says Van den Heuvel. “The experienced players who’ve been there, with the freshness and power of young athletes.”

The recovery capacity of youth is integral to producing eight quality games over 13 days. “They need to have the engine, and the capacity and mental ability to perform in a series of games.” As well as pure speed, he adds, since “the game is getting faster and faster.”

So as the coaches assess the candidates’ physical and mental resilience, the athletes pray for a spot among the final 16. It’s the hardest part of the job, says Van den Heuvel, disappointing top athletes. He clears his throat. “But it has to be done.”

The road to Paris is strewn with formidable opponents. Van den Heuvel acknowledges the traditional powerhouses: "Holland is leading in the world rankings, because it was the European champion; Germany was world champion. Australia is always competing at the highest level. Team GB has a good programme and good athletes.” But even with the other teams, “you have to produce quality to get results.” Every match is treated with respect, with coaches devising specific game plans for each contender.

That implies tactical wizardry. “With every big event you need to look for the changes you need to be successful," van den Heuvel emphasises. The team can’t rely on past victorious methods. “The better the players, the more they can enact tactical changes in big tournaments.” Though few secrets remain for long in the limelight, staying fresh and surprising will be key. The coaches relentlessly analyse and respond to new trends, like the rise of the aerial game. Hitting the ball through the air is “a low-risk attack and you can have big results.” The Lions must work on using it – and defending it too.

Beyond these intricacies, however, lies strength of belief. How does Belgium deal with the spotlight? “At the level we are working at there’s always immense pressure. Without that, you can't perform,” Van den Heuvel says.

The best investment in Brussels? Your child’s future.

At the level we are working at there’s always immense pressure. Without that, you can't perform.

But he’s wary of a pitfall in the other direction. “Guys who win need to understand they have to do more,” he continues, “but there's a tendency to do less.” Mental conditioning is fundamental to help players use the defence of their title not as pressure, but as motivation.

Talking of motivation – surely the grandeur of the Olympics helps? “For our sport, it’s the biggest event possible,” he says. But it’s way more fun to go as a spectator. “The vibe the city gives you. Everyone is enjoying sport, everyone is equal.”

Attending as a contender is different. “We have to make our world as small as possible,” Van den Heuvel says, by sequestering themselves and foregoing any energy or concentration-sapping interaction. “We start on the Saturday against Ireland. The day before is the beautiful ceremony – but we will not be there,” says Van den Heuvel with a voice like concrete. “For participants, it’s not about glamour. It’s all about really hard work and really hard focus.”

Yet as a Dutchman managing a Belgian team, he embodies in a small way the cross-border vision. “I live in the south Netherlands where Antwerp is closer than Amsterdam,” he says. When he needs urban action, he heads to the Belgian city. “I’ve loved Belgian culture for a long time –that’s one of the reasons I wanted to work here,” he says, name-dropping shrimp croquettes. “The way Belgian people enjoy life, that’s how I want to live my life. I feel connected.”

The connection of a small country coming together to invest in and focus on a game. The fruitful bond between Van den Heuvel and McLeod. The virtuous cycle of young hopefuls and the wizened veterans, fuelling and learning from each other. Van den Heuvel will step down after the Olympics – but he’s been part of a revolution in Belgian field hockey that will not ebb so easily, whether Paris brings gold or not.

The pharmaceutical sector brings unprecedented levels of investment to Europe. In 2022, R&D investment amounted to €44 billion, hiring some 865,000 employees, and bringing €215 billion in added value to the European economy.

In the face of emerging health challenges, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) is working to maintain Europe’s innovative edge. Under the tagline “We Won’t Rest,” EFPIA’s members are leading the drive to innovate and find new treatments for previously untreatable conditions.

To protect the health resilience of ordinary European citizens, innovation, they believe, is key to tackling this challenge. 8,000 new medicines in the pipeline globally and new breakthroughs such as mRNA and gene therapy, will provide novel solutions to rare diseases and conditions. To enable this, European authorities must set the right conditions to allow research to thrive.

In an interview with The Brussels Times, Peter Guenter, CEO Healthcare at Merck, and member of the board of EFPIA, set out the urgent needs for his sector, and for patients in the post-Covid era. European pharmaceutical companies played a pivotal role in the fight against the pandemic.

“Covid-19 has been a case in point,” he told us from Germany.“ It’s only because we

have a very strong and resilient ecosystem in Europe that we have been able not only to immediately find new technology in mRNA with BioNTech, but also scale it up in terms of clinical development and manufacturing.”

Since the start of the pandemic, more than 13.5 billion doses of mRNA-derived vaccines have been administered globally, a feat previously thought impossible. Not only did the pandemic highlight the importance of persistent and sustained innovation of healthcare, Guenter argued, but also revealed inherent health challenges and shortcomings to be solved, which can only be solved with increased investment.

“We are confronted with an ageing population, and the number one challenge now is healthy ageing. How can we better manage diseases like Alzheimer’s, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, or cancers, which typically become chronic diseases,” he said.

Innovation is not limited to curative medicines, but also therapies that improve quality of life or are preventative. Medical treatment, apps, and educational campaigns are an important part of avoiding diabetes and

cancers. Pharma has a role to play in this paradigm shift.

The pharmaceutical sector brings unprecedented levels of investment to Europe. In 2022, R&D investment amounted to €44 billion, hiring some 865,000 employees, and bringing €215 billion in added value to the European economy, according to figures from EFPIA. However, as diagnoses increase, the R&D needs of the sector continue to increase.

Development of the pharma sector, Guenter believes, should be considered an investment into the larger European healthcare ecosystem.“ Medicines are part of the solution. Medicines keep patients out of hospital, avoid surgeries and transplantation, and decrease the burden of care workers,” Guenter explained.

Investment in R&D for new medicines is also important in the treatment of rare diseases. To date, only five percent of rare conditions have a therapeutic option. Merck and EFPIA aim to change that.

Through the Rare Disease Moonshot programme, pharmaceutical companies engage in non-competitive joint research and regulatory science on rare diseases, ensuring “continued progress” in research. “For ultra-rare diseases, the solution will come by pooling resources,” the Merck boss believes. “The Rare Disease Moonshot aims to find new momentum and impetus to address these conditions.”

New technologies employed by Merck and other EFPIA members have already unlocked therapies for the treatment of diseases, such as CAR-T cell therapy for cancers or personalised medicines. Increased use of artificial intelligence (AI) is also helping Merck to unlock new solutions and more efficient R&D.

“The promise of AI and big data analytics is that you will have more shots on goal faster, more cost-effectively, and therefore R&D productivity will significantly increase,” Guenter noted. He remains optimistic that the pace of innovation should further accelerate in the next 20 years.

Innovation, however, is dependent on the regulatory framework. Europe must remain competitive in developing evaluating and approving new technologies, the Merck CEO affirmed. “The definition of unmet medical needs must remain inclusive, recognising the importance of step innovations to improve patient quality of life.”

Under current European Commission pharma-legislation proposals, Europe risks losing a third of its share of global R&D by 2040, EFPIA warned in November 2023. This amounts to €2 billion in lost R&D innovation each year. In the context of increased global economic and geopolitical division, this would risk Europe’s position

as an innovation hub.

“The EC proposed reducing regulatory data protection from eight years to six years, which would result in fewer products being developed and launched in Europe. Intellectual property is the lifeblood of innovation. We need a strong IP system in place to retain our innovative power in Europe, otherwise innovation might move somewhere else or in some cases do not happen at all,” Guenter warned.

Regionalisation also poses a threat to innovation. Far from creating “Fortress Europe”, the Merck boss advocates for “strategic interdependence” with China, converting Europe into an “innovative hub that ensures both European and Chinese patients benefit from mutual innovation.”

Looking forward to the future, Guenter points to initiatives such as the European Health Data Space (EHDS) as a means to further innovation. Medical information sharing will help private companies find new insights, repurpose medicines, discover new targets, and make Europe “a formidable hub for pharmaceutical innovation.” Nevertheless, the EHDS needs to strike the right balance between a broad availability of data and the protection of IP rights. Anything deviating from this principle might have detrimental effects on the attractiveness of the EU as a place for pharmaceutical research and innovation.

“We should continue to be ambitious, striving for a world where future generations can prevent or live well with diseases… benefiting from ongoing advancements in healthcare technology,” Guenter concluded.

Innovation is not limited to curative medicines, but also therapies that improve quality of life or are preventative. Medical treatment, apps, and educational campaigns are an important part of avoiding diabetes and cancers.

For Dylan Borlée, running runs in the family. With his brothers, Jonathan and Kevin, the Borlées made up three-quarters of Belgium’s brilliant 4x400m relay team, but now he is the last one standing. As he hits peak form, he tells Leo Cendrowicz why the Belgian Tornadoes could clinch gold this year

Dylan Borlée saunters into Cook & Book, the sprawling café bookstore opposite the Woluwe Shopping Center, and just a short walk from the Stade Fallon running track where he usually trains. The svelte, handsome athlete is alone, which should not be unusual – but for the fact that he is typically associated with others.

A veteran of the Rio and Tokyo Olympics, Borlée is one of Belgium’s best medal hopes in Paris this summer, as part of the 4x400m relay team (by his own admission, the individual 400m title might be a step too far).

The 31-year-old is also the youngest member of the extraordinary Borlée family. Like his older siblings – Olivia and twins Jonathan and Kevin – Dylan has been on starting blocks and podiums at the world’s top running meets.

The Borlées are not merely a Belgian phenomenon, but a worldwide one. Olivia, 38, was part of the gold-medal-winning women’s 4x100 relay team at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. Twins Kevin and Jonathan, both 36, have been part of relay teams winning countless world and European titles, as well as individual medals since 2010, most recently gold in the 2022 World Indoor Championships (Jonathan’s 44.43 for the 400m in 2012 is still the Belgian record). Their father, Jacques, 66, also their coach, ran for Belgium in the 1980 Olympics in Moscow.

This year, however, Dylan will be without his brothers. Eight years ago, at the 2016 Rio Olympics, Dylan, Jonathan and Kevin accounted for three-quarters of the Belgian relay team that came fourth. Now Dylan is the last runner standing, so to

speak. Olivia retired long ago, and while Jonathan and Kevin still run, they no longer compete at the highest level.

Now on the verge of what he considers his strongest year, Dylan is honing his mental and physical preparation ahead of Paris. "The pressure is immense,” he says as he orders a ginger ale. “Everyone's talking about Paris, but for me, it’s about staying healthy and focused on the present. I take it one step at a time, concentrating on daily routines. A bit of pressure is good; it sharpens my focus."

Just behind him, a big book on Bob Dylan is on display, offering a pleasing ‘Dylan’ next to his head. He laughs at the coincidence. But he wasn’t named after the singer – Olivia, six when he was born, chose the name simply because she liked it.

But now he wants to talk about running. He has new relay partners – Alexander Doom, Jonathan Sacoor and Christian Iguacel – and the aim is to build the best team, whoever he passes the baton to.

"Creating a successful relay team is like assembling a puzzle," he says. "It's not about simply choosing the fastest runners. Each athlete brings a unique quality, whether it's experience, speed at specific points in the race, or the ability to handle the baton with precision. Decisions are often made at the last minute, factoring in tests, current form, and overall fitness."

There is, he says, a delicate balance of individual strengths and collective harmony. "Every athlete has to prove themself, especially when everyone is fit and ready. It's a competitive atmosphere, but it's rooted in mutual support and respect."

Before getting carried away about his prospects, it is worth remembering Bel -

Eight years ago, at the 2016 Rio Olympics, Dylan, Jonathan and Kevin accounted for three-quarters of the Belgian relay team that came fourth. Now Dylan is the last runner standing, so to speak.

It's not about simply choosing the fastest runners. Each athlete brings a unique quality, whether it's experience, speed at specific points in the race, or the ability to handle the baton with precision.

gium has never even been on the podium for either the relay or the 400m individual events at the Olympics. However, they have come agonisingly close in the relay several times: fourth in Tokyo three years ago and Rio in 2016, fifth in London in 2012 and fourth again in Beijing in 2008. In the individual event, only in 2012 have any Borlées reached the final, with Kevin and Jonathan coming fifth and sixth respectively.

Can the so-called Belgian Tornadoes finally catch relay giants like the United States, Britain and Jamaica?

Dylan wryly notes that they have already done so this year, winning the 4x400m relay at the World Indoor Championships in Glasgow in March. And he says they have an exceptional team spirit. “We want to fight for each other. We don't just

think about ourselves we also think about the other guys,” he says. “For example, at the World Relays in the Bahamas, I hurt myself a little and my first thought was the guys in the team rather than thinking that my season might be over through injury. It's instinct that takes over and we think about the team.”

Dylan is also hitting his best form, which is hardly a given during a runner’s career. “This is my strongest year in terms of training, it's going really well, so I'm really confident,” he says. “I had a very good season in 2023, beating my record – and it’s the first time in my career where I did it two years in a row. And I feel capable of beating my record again. But I have to stay focused,” he says, before breaking from French into English: “I don't take this for granted.”

Dylan fell into a slump after the Tokyo games in 2021, stagnating after years of steady improvement. “I couldn't move on to the next level. I couldn't find the key.”

He turned himself around mainly by rethinking his mental preparations. “I learned how to feel good about myself,” he says. “I run a lot with my emotions, with my feelings – I’m not a robot – and I used to find it hard to get in my zone. But now, I know myself a lot better. And I’ve found it is a lot more fun now.”

He is also thinking about the long-term prospects for the Tornadoes, which, he emphasises, do not just involve the Borlées. “We need to sustain the momentum,” he says. "It’s not just about the present but about fostering a culture that thrives even as individual athletes come and go."

It’s easy to assume that Jacques is the driving force behind the family’s running success, akin to Richard Williams zealously pushing his daughters Venus and Serena to become tennis champions. But Dylan credits Olivia, who was Belgium’s flagbearer at Rio 2016. Inspired by sprinter Kim Gevaert, Olivia started her own training regimen, bringing her father in later. In turn, Jonathan and Kevin also caught the bug. Only second sister, Alizia, 33, broke with the family tradition by not competing.

Dylan says running with his brothers was an unbeatable feeling. “It's difficult to even describe this sensation. It was calming being together because we trust each other so much and we know each other so well – it was like playing together in the garden,” he says. “If I don't win a medal with my brothers, it's not the same thing –I don't have the same emotion.”

He knows the window for running glory has been closing for his brothers, but there

OPERA

RICHARD WAGNER

ALAIN ALTINOGLU, PIERRE AUDI

KRIS DEFOORT

KWAMÉ RYAN, TED HUFFMAN

MIKAEL KARLSSON

ARIANE MATIAKH, IVO VAN HOVE

RICHARD WAGNER

ALAIN ALTINOGLU, PIERRE AUDI

CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI’S OPERA TRILOGY REVISITED

LEONARDO GARCÍA ALARCÓN, RAFAEL R. VILLALOBOS

HAROLD NOBEN

DEBORA WALDMAN, MICHAEL DE COCK & CARME PORTACELI

GEORGES BIZET

NATHALIE STUTZMANN,

DMITRI TCHERNIAKOV

Balance is key. It’s not just what your body needs but what your mind needs. So from time to time, I will have a glass of wine, which can help me to relax.

are still opportunities. “I really hope to be able to run again with them. Will it be possible? I don’t know, but I am so grateful and lucky to have done it because I really experienced emotions where I don't know if I'll be able to experience that again.”

Dylan’s training regimen is gruelling and meticulously planned. "In the base building phase, we train 20 to 30 hours a week, including physiotherapy and mobility exercises. As competitions approach, normally all the work must have been done and the focus shifts to quality over quantity,” he says.

Diet also plays a pivotal role. "Each athlete's needs are different and we shouldn’t just copy each other,” he says, before noting that he has to watch that he eats enough as he loses weight easily.

Snacks and fast food are avoided, as well as late-night meals, but the regime is not too strict. “Balance is key. It’s not just what your body needs but what your mind needs. So from time to time, I will have a glass of wine, which can help me to relax.”

He also needs distractions. That can include his cinema and music, but Dylan’s first choice is going out to dinner with his wife and friends. He also mentions playing video games – his current favourite is Apex Legends – and following other sports, like NBA basketball and English Premier League football (he’s an Arsenal fan).

In a few weeks, he will be in one of the most intense sporting environments ever. What is the atmosphere in the Olympic Village like?

“Rio was the first time, so I felt it as a little kid,” he says. “We were closed off from the world in these large buildings where all the athletes are we all eat together in a huge refectory where you bump into superstars like Rafael Nadal.”

But Tokyo, delayed a year because of the Covid-19 pandemic, was overshadowed by health precautions. “In the refectory, there was Plexiglas between everyone, we had to do tests all the time, and there was no crowd in the stadium,” he said. “At the same time, I'm grateful for that because it made me realise that maybe I was putting a little too much pressure on myself.”

Now he’s hoping for something else. “Rio and Tokyo were two completely different experiences but I want Paris to be something else,” he says. “I definitely want to feel this fervour around sport in Paris, to really feel the enthusiasm.”

He also has to think about life after the games. September will be a fallow period when he doesn’t train at all. He says the month-long hiatus before the new season is essential for the body and soul – but after the mental and physical pause, he’ll come back freshly motivated.

He’ll still do sport during the break, but other disciplines – cycling, padel and football – although he has to be careful about injuries. The Borlées long avoided skiing for that reason but did so two years ago. “Sometimes, mentally, we have to find fun things to do and not focus only on athletics,” he says

After that, he has nuptials to think of. His civil marriage to Celine Vrancx, a biomedical researcher, was earlier this year but their wedding with friends and family will be in the autumn. “I have always had difficulty focusing on two big things at the same time, but fortunately my wife takes care of it much more than me,” he says. “What happens next is something to look forward to – it’s a bit scary but it is exciting too.”

The fresh kiss of crisp morning air. Dappled sunlight. Toes touch the baseline. Ready to return.

Join Aspria today.

Of all Subarus produced in the last decade, 97% are still on the road. Mileages of three to four hundred thousand kilometers and more are no exception.

There are only a few car brands with their own character, Subaru is one of them - quirky and for the enthusiast who dares to distinguish themselves. Let’s take a deeper dive into this brand which has safety, reliability, and driving fun in its DNA.

Size does matter, even when it comes to car brands. Subaru produces approximately 900,000 cars per year, with about 70% of the total volume is sold in America, the largest market. The home country, Japan, is the second-largest market and in Europe, the brand sells around 30,000 cars annually. Subaru is seen as a small brand but to put the production numbers into perspective, Subaru is about the size of Opel and twice the size of Volvo.

Subaru is mainly known for its SUVs and Crossovers, all spacious, safe, and very capable cars both on and off-road. The brand is also known for its blue and yellow WRX STI rally cars, which made history by becoming three-time world rally champions. The focus now is on SUVs and EVs. New is the Solterra, the brand's first fully electric SUV.

Subaru embraces differentiating technologies, not for the sake of being different,

but because of the benefits of these unique technologies. Every Subaru with an internal combustion engine has a boxer engine. Due to its flat design, the engine sits low in the car. Safe, because the engine slides under the car in a frontal collision. This construction method also positively influences the road holding with a low center of gravity. The brand has now produced over 20 million boxer engines.

All Subarus come with four-wheel drive as standard, proven to be safe in winter conditions. AWD also has advantages in the wet and the dry, and there is always grip, even when cornering. Additionally, the straight-line stability of cars with AWD is better, the tyres wear more evenly, and there is more driving pleasure. With AWD, Subaru offers peace of mind, the relaxed feeling that the car gives you in difficult conditions. There are no clearer arguments for choosing AWD, especially now that the weather is becoming more extreme in our part of Europe. Subaru has produced more than 21 million cars with Symmetrical All-Wheel Drive over the past 50 years.

Subaru aims for zero road casualties by 2030, thanks to special technology and active safety measures, as well as thick Japanese steel, ring-shaped cage constructions, and a driver support system called EyeSight. This works with two cameras because these cameras see more than laser or radar and estimate contrast better. It acts as an extra pair of eyes for the driver and helps avoid collisions and is truly one of the best safety systems in the industry, according to independent safety organizations. EyeSight is always standard on every Subaru and so far more than five million cars with this safety system have been delivered.

The location of the cameras has been deliberately chosen. Parking damage is easily incurred (think of a reversing car with a tow bar that pulverizes a bumper while parking). For cars with radar or laser, this easily results in many thousands of euros in damage. Not with EyeSight, which sits high and dry behind the front windscreen. You should also take that dryness literally. Have you ever driven with laser or radar in a blizzard? The systems are quickly clogged up and no

longer work. With EyeSight, windshield wipers and heating keep the window cleaner under appalling conditions, so the system works better. Are there limits? If the human eye can no longer see, EyeSight can no longer see either.

Subaru is a brand with an eye for detail, which means that every Subaru is full of all kinds of clever features. How about the thin A-pillar that does not obstruct the view, the large mirrors mounted on the doors, the large glass area, and the narrow C-pillar for optimal all-round visibility? There's more: a step on the sill (Outback and Forester) at the back door makes it easier to load stuff on the

roof. Or a washer on the reversing camera (Forester and Outback). And have you ever tried to operate the AC knobs with gloves on? In a Subaru, it is no issue.

Safe and reliable, that is what Subaru is. Of all Subarus produced in the last decade, 97% are still on the road. Mileages of three to four hundred thousand kilometers and more are no exception. The brand always scores high in reliability surveys, including those from the American JD Power and various national Consumer Associations.

Solterra is Subaru's first EV. Is Subaru late with such a car? Perhaps, but there is a nuance: the brand will never be at the forefront of new developments. That may be the fate of a small and independent brand. It also has to do with the requirements the brand sets for its models. The EV must also be a true Subaru, a car that makes possible whatever you decide to do today. The Solterra will take you wherever you want to go. Therefore, a true Subaru. And 100% electric.

So, Subaru. A brand that attaches great importance to safety. Hence four-wheel drive, boxer engine, EyeSight/SafetySense, and a wealth of safety equipment. Subaru also values Peace of Mind and non-conformity. Subaru looks like a Subaru and has technology that no one else uses. That technology is not there just to be different, but because it works. There is a sacred belief in that technology. Finally, Subaru finds driving pleasure and adventure important. Don't see the car as a limitation, but as a means to reach your goal, in a way that is fun too. That's Subaru.

www.subaru.be

Subaru aims for zero road casualties by 2030, thanks to special technology and active safety measures, as well as thick Japanese steel, ringshaped cage constructions, and a driver support system called EyeSight.

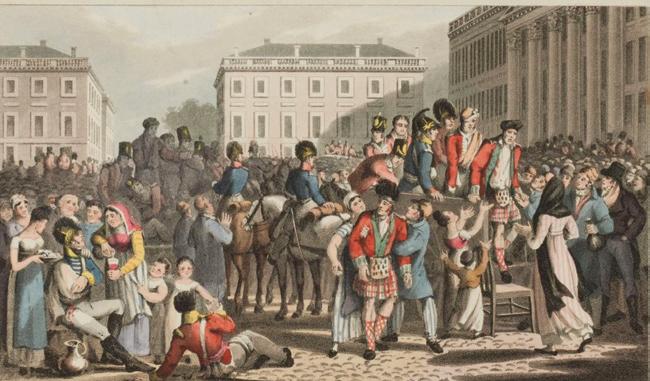

It seems implausible now, but just two years after the end of the First World War, Antwerp hosted the 1920 Olympic Games. It was a miracle of postwar reconstruction and reconciliation, but as Leo Cendrowicz writes, the city pulled off a spectacular show that may well have saved the Olympic movement.

Less than two years after the signing of the Armistice ending what was then known as the Great War, the strongest and fastest men and women of their generation gathered in Antwerp for an unprecedented festival of sport and culture.

One of the most remarkable episodes in Belgian history, the Antwerp Olympic Games of 1920 aimed to draw a line under the war that had so devastated the country.

But the Antwerp Olympics were also extraordinary because they were thrown together at breakneck speed. In April 1919, six months after the end of the conflict and just 12 months before the Games were set to begin, the International Olympic Committee named Antwerp as the host of the seventh Olympiad of the modern era.

While Belgium had been suggested as host nation as far back as 1912, the First World War interrupted the entire Olympic process (the 1916 Games in Berlin were understandably cancelled). Brussels was originally named, but before the war broke out, Royal Beerschot Football Club persuaded the authorities to switch to Antwerp, arguing that the proud city of Rubens was more suited to the Olympic culture.

But confirming Antwerp was a huge risk. Even then, Olympics took at least four years to prepare for, and that assumed the host country had not been ravaged by a war of unprecedented savagery and destruction. Ypres – or Ieper – the site of some of the bloodiest fighting just a few years earlier, had not been cleared of weapons or body parts. Indeed, many of the foreign athletes competing already knew Flanders, having served as soldiers for the Allied forces.

Another disruptive factor was the lingering 1918–1920 Spanish flu, which claimed between

25 and 50 million lives around the world, likely making it even more deadly than the Covid-19 pandemic.

Heavily bombed during the First World War, Antwerp nonetheless responded to the challenge with vigour. The first stone of the transformed Beerschot Stadium, the oldest football field in Belgium, was laid by mayor Jan De Vos on July 4, 1919. The city tried to turn the war into an asset, with advertisements in sports magazines beckoning, “Come visit the battlefields of Liberated Belgium!"

A key political issue was whether to invite the defeated powers from the war. Baron de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic movement, left the choice to the host country. But a demonstration by locals through the streets of Antwerp two months before the official opening indicated how strong feelings were against them. Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary and Turkey were not invited.

Record numbers still attended: there were 29 nations and 2,626 athletes competing in 154 events in 22 sports. Some were from newly created countries like Yugoslavia, Estonia, Czechoslovakia (succeeding Bohemia) and New Zealand (no longer part of a combined team with Australia).

Indeed, the echoes of war were felt throughout the games. At the opening ceremony, many of the athletes were soldiers and marched in uniform. The stadium itself had a plaster statue of a Belgian soldier heaving a grenade.

The games were officially opened on April 20 by King Albert and began with a Catholic

Confirming Antwerp was a huge risk. Even then, Olympics took at least four years to prepare for, and that assumed the host country had not been ravaged by a war of unprecedented savagery and destruction.

Boxing and wrestling were staged in the zoology hall of Antwerp Zoo. The swimming and diving competitions were held in the moat that surrounded the old city, with spectators on benches erected on ancient ramparts.

mass, honouring athletes killed in the war.

There were many firsts at the opening ceremony. The first flight of white doves, symbolising peace and brotherhood, was released - ironically accompanied by the firing of a gun salute. The first Olympic oath was pronounced by former war Belgian pilot Victor Boin, a freestyle swimmer, water polo player and épée fencer. And Antwerp saw the first use of the Olympic flag, one of the most recognisable symbols in the world, with the distinctive five interlocking rings signifying the union of five continents.

Most of the events were held in the newly constructed stadium. But boxing and wrestling were staged in the zoology hall of Antwerp Zoo. The swimming and diving competitions were held in the moat that surrounded the old city, with spectators on benches erected on ancient ramparts. Rowing was held at the end of the Willebroeck canal, amid reservoirs, oil storage cans and factories. Yachting was moved to Ostend, and shooting events were held at an army camp of Beverloo, 60km away – except for running deer shooting and trapshooting, which was near Antwerp.

The Games lasted almost five months, ending on September 12, as they combined both winter and summer events. There were some unexpected events on the programme,

including polo, rugby, tug-of-war and korfball. Perhaps the most unusual of Olympic disciplines were the art competitions: medals were awarded in five categories – architecture, literature, music, painting and sculpture – for works inspired by sport-related themes.

The Belgian public was generally indifferent to the games. Some of the events, such as ice hockey and rugby, had never been seen before and were dismissed as exotic curiosities. Only swimming, boxing, wrestling and football drew big crowds.

The women’s competitions faced particular prejudice. De Coubertin, obsessed with the male, chivalric ideal, was against women taking part and Count Henri Baillet Latour, Belgium’s chief Olympic figure, was a misogynist. Despite this, Antwerp can claim to have paved the way for the greater acceptance of women into the Olympics.

There were other problems. Rain left ruts and depressions on the track surface in the stadium, causing the runners constant worry – and it rained almost constantly during those August days of 1920.

The water for the swimming and diving events was dank, dark and, at just 10ºC, frigid: divers brought woollen stockings, socks and mufflers to keep warm and gave each other rubdowns between dives, while several water polo players were pulled out of the water on the verge of hypothermia

In the final medal count, Belgium came fifth with 14 golds, 11 silvers and 11 bronzes (behind the US, Sweden, Great Britain and Finland). One of the lost important golds was that in football: the Belgians, already nicknamed the Red Devils, won the final after Czechoslovakia stormed off the pitch; in an era before the World Cup, could legitimately consider themselves world champions.

The football triumph was, unfortunately, one of the only upsides to the Olympics as far as the public was concerned. Antwerp lost money on the event – although it is by no means the only Olympic city to do so – as the organisers overestimated the economic benefits to the local economy and few considered intangible benefits like boosting local pride.

But if the games felt like an indulgence in 1920, they would come to be appreciated in time for helping relaunch the Olympics. To have athletes coming from all over the world only two years after the last shot was fired was an almost unbelievable feat of management

Baron de Coubertin was effusive in his gratitude. “Belgium has now succeeded in

Since 1995

700 World Wines

500 World Spirits

50 Belgian Beers

Wide range of belgian products ; wines, whiskies, gins, rums, pekets, liqueurs

Wine & Spirit shop - Online sales

Chaussée de Charleroi, 43 1060 Bruxelles 02/534.77.03 www.migsworldwines.be mig@migsworldwines.be

Follow us !

setting a record of intelligent and rapid organisation or – if I am allowed to speak in less academic but more expressive terms – a new record for its skill in improvisation.”

The Antwerp Olympics - which included both summer and winter events - showcased a new generation of athletes. Here are some of the

sporting highlights:

Finnish middle-distance runner Paavo Nurmi won the first three of his total of Olympic gold medals. The ‘Flying Finn’, whose statue stands outside the Olympic stadium in Helsinki, was forced to quit school at the age of 12 and work as an errand runner. Fellow Finn Joonas ‘Jonni’ Myyrä shattered the javelin record by more than five metres with his 65.78m throw.

France’s Joseph Guillemot, a pack-of-cigarettes-a-day man and wartime victim of poison gas attacks, won the 5,000m title. He nearly repeated his feat in the 10,000m but suffered from stomach cramps and shoes that were two sizes too big after his own were stolen. He still managed to win silver.

The Canadian side that won the ice hockey gold was made up entirely of players of the Winnipeg Falcons. Even more remarkably, all but one of them were Icelandic immigrants, who had cut their teeth playing against each other as none of the other Winnipeg teams wanted to play a squad consisting of "ragtag immigrants."

South America claimed its first gold medal in 1920 when Guilherme Paraense of Brazil won the rapid-fire pistol event.

French ace Suzanne Lenglen, the first real global tennis star, won the Olympic singles gold, losing only four games along the way.

Italian fencer Nedo Nadi won the individual foil and sabre titles and led the Italians to victory in all three team events, for a record of five fencing gold medals.

American diver Aileen Riggin, from Newport, Rhode Island, became the youngest gold medal winner at just 14 years and 119 days. At 1.40m tall and weighing 29.5kg, she was also the smallest athlete at the 1920 Olympics.

At the other end of the scale, 72-year-old Swedish shooter Oscar Swahn won silver in the team double-shot running deer event to become the oldest medallist ever.

American Eddie Eagan is the only athlete to win gold medals during the summer and winter Olympic disciplines. He won the light-heavyweight boxing title in Antwerp and in 1932 at Lake Placid, he was part of winning bobsleigh team.

Jack Brendan Kelly, a 20-year-old manual worker from Philadelphia, won two rowing titles in the space of just 30 minutes. His daughter, Grace Kelly, would later become a Hollywood star and Princess of Monaco.

US swimmer Ethelda Bleibtrey won gold medals in all three women's contests –100m and 300m freestyle and the 4x100m relay – and broke the world record in every one of her five races.

Ukelele-strumming, Hawaiian surfing pioneer Duke Kahanamoku won golds in the 100m freestyle and the relay, while also representing the US in water polo.

Britain’s 1500m silver medallist Philip Noel-Baker would later become an MP and nuclear disarmament activist. In 1959 he became the only Olympian ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

We promise that by the end of your child’s first playtime they’ll have made made new friends.

We all know what it’s like to be new, it can be daunting, particularly for children starting a new school, possibly in a new country. Because of this we make a promise - that by the first playtime your child will have someone to play with and will have made new friends.

The scene is set from day one, the first minutes, the first hours, if a child is going to feel happy, welcome, loved and cared for. In order to build the confidence they need to thrive, they need to have that feeling from the minute they walk through our doors on that very first day.

Confidence is one of the British School of Brussels' ‘Whole School’ principle values, and a core part of our Guiding Statements. Primary School is where it all starts, the beginning of the formative aspect of our values-driven, unified and holistic education.

One of the better ways to learn is through discovery, and our Primary School teachers plan different thematic ‘Units of Discovery’ every year. These themes are based upon key

concepts and central ideas which draw on the children’s experiences to provide a more meaningful context for learning - learning with confidence.

Our academic year is punctuated by so many wonderful events - Book Festival celebrations, drama productions, sports tournaments and concerts - that it feels like something magical is happening every day! The truth is it does.

Our students are simply incredible, and we pride ourselves on providing the best days of learning we know they deserve.

We have a thriving French/English bilingual programme which uses the British curriculum as its foundation, but we’re focused on taking risks and inspiring passions, too. Whilst we have high academic expectations, we give equal weighting to a number of life skills we consider just as important: taking care of ourselves and other people, having respect for the world around us, becoming confident in our own skin and being open to other people’s stories and histories. We work together on cultivating these values every single day.

BSB’s Primary School is the best of both worlds with an inclusive, small-school feel and culture set in an expansive, well-resourced and beautifully- maintained campus.

Students benefit from unrivalled care and support with specialist teachers for languages, art, music and sport, as well as access to our swimming pool, extensive sports facilities and fully equipped theatre.

Ultimately, what sets BSB Primary School apart is the deeply caring environment which many people describe as simply ‘being in the air’. Whilst our academic prowess is evident in our consistently high results, it is the culture of kindness, respect and consideration for others that defines us.

This culture is palpable in every interaction and woven into the fabric of our community. As Neil Ringrose, our Head of Primary, reflects, the positive feedback received from parents encapsulates the essence of our school—a place where joy abounds, hearts are touched, and futures are shaped. “A special part of my job is receiving the glowing testimonials from parents - it makes my job completely worthwhile,” he says. “Just thinking about them makes me smile every day.”

Many of these testimonials highlight the unique feeling at our school. “The atmosphere in your school is special,” one parent said. “It’s joyous; for children and, as importantly, adults.”

Another said: “I don’t think there has been a single day over the past three years where our children woke up and were not looking forward to going to school! Like all parents, we

want our children to be excited to learn, discover and be curious; BSB has certainly nurtured this to the fullest!”

A progressive education

Inclusive and international in our outlook, we create curious, confident and courageous learners and families that chose us because they recognise this progressive, all-encompassing approach.

It’s not only our promise that by the end of your child’s first playtime, they’ll have made new friends; but also that when they leave –whether after a few months or many years – they’ll cherish the values, skills and knowledge they’ve learned here, that they’ll carry with them for life.

To find out more visit www.britishschool.be

When your child leaves BSB they’ll cherish the values, skills and knowledge they’ve learned here and carry them with them for life.

Neil Ringrose Head of Primary School & Vice-Principal

The Olympic Games showcase sporting prowess from 40 separate disciplines, but there are many events that it overlooks. Harry Pearson celebrates the uniquely Belgian games that have yet to be accepted as Olympic events

Belgium boasts Olympic gold medals for both the equestrian long jump (Constant van Langhendonck, 1900) and live pigeon shooting (Leo de Lunden, 1900), as well as for more conventional sports such as the men’s hockey and women’s heptathlon. Yet while the nation has excelled in cycling and judo and punched above its weight on the track thanks to the likes of Emile Puttemans and Ivo Van Damme, there’s little doubt that Belgium’s medal haul in Paris would be greatly enhanced by the inclusion of some of the country’s more singular pursuits and games.

Archery has been part of the Olympics since the first modern games were held in Greece in 1896 and Belgium has done remarkably well at it collecting 21 medals. Sadly, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has steadfastly ignored a less conventional version of the sport, popinjay, or, as it is known in Dutch, staande wip.

This involves firing arrows at targets set on a tower high above your head. Since arrows come down as well as go up, it is by no means the safest way to shoot them, which may explain why popinjay has pretty much died out everywhere in Europe except Belgium, the Netherlands and a couple of places in Scotland.

Flanders is a stronghold of vertical archery and you’ll see skeletal shooting towers looming mysteriously above fields in places like Eeklo and Havre. There’s even an exhibition of historic staande wip artefacts in the Archer’s House in Watten. In Scotland, popinjay is more or less a ceremonial event, but in Belgium, it is different, especially when the Flemish meet the Dutch in keenly contested international fixtures for which the 1970s parental catchphrase, “It’s all fun and games until someone loses an eye” might have been invented.

Golf has been a feature of the games since 2016 (there were earlier Olympic gold tournaments in 1900 and 1904 though sadly the

event scheduled for the Antwerp Games of 1920 had to be cancelled due to a lack of entries). So far Belgium has made little impact, but that might be very different if the IOC were to include one of golf’s ancestors, jeu de crosse (also called jeu de chole and crossage).