12 minute read

Dental Management of a Talon Cusp on a Permanent Incisor in Traumatic Occlusion

Dental Management of a Talon Cusp on a Permanent Incisor in Traumatic Occlusion

Bret Lesavoy, D.M.D.; Richard Yoon, D.D.S.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to report the case of an 8-year-old female with occlusal interferences involving the permanent maxillary right central incisor (PMRCI) due to a Type 1 dens evaginatus, also known as a talon cusp (TC), causing displacement of the affected tooth. Clinical concerns related to TCs include occlusal interferences and increased risk for dental injury, displacement of the affected tooth, caries, tongue irritation and esthetic concerns. The TC in this report was reduced periodically over two months. Following each reduction, 5% topical sodium fluoride varnish was applied as a desensitizing agent. Upon completion and removal of the TC, sealant (Ultra Seal XT R plus TM, Ultradent Products, Inc. USA) material was applied to the lingual surface of the affected tooth. The patient was evaluated five weeks after treatment completion, during which time, no clinical signs or symptoms related to the reduction were reported.

Dens evaginatus, also known as talon cusp (TC), is a relatively uncommon dental anomaly in which an accessory cusp-like structure projects from the lingual or facial surface of the crown of a tooth. A TC resembles an exuberant tubercle of tooth structure that includes an enamel outer surface, dentin core and an inner extension of pulpal tissue

of varying size. While TCs are thought to be more prevalent in males, both sexes are affected, with an overall incidence of 1.67% and a greater predilection in the maxillary permanent dentition.[1,2]

Although these dental tubercles range in size, several clinical problems can result from TCs, including but not limited to, tongue irritation, occlusal interferences, esthetic concerns, malocclusion and displacement of the affected tooth, cusp fracture, caries, and pulpal inflammation and necrosis.[3,4]

Talon cusps may also present diagnostic and resulting treatment complications, as the radiopacities of the cusps in unerupted dentition may bear resemblance to a compound odontoma or a supernumerary tooth, which may lead to unnecessary surgical procedures.[1,6]

The purpose of this report is to document a case of Type 1 dens evaginatus involving an 8-year-old girl with increased risk for displacement of the affected tooth and dental injury.

Case Description

An 8-year-old female of Hispanic origin with an unremarkable medical history presented to the community dental clinic for children at a large academic medical center with a referral for comprehensive dental care with a chief complaint of odontogenic pain. The parent also reported a “tooth-like horn” extending from the palatal gingiva of the permanent maxillary right central incisor (PMRCI) (Figure 1a).

The patient’s medical and family history was noncontributory. Extraoral examination revealed a convex facial profile with no marked signs of pathology. Intraoral examination revealed a Class 1 molar occlusal relationship, unremarkable soft tissue and normal eruption pattern in the early mixed dentition with mild crowding of the mandibular arch. Hard-tissue examination revealed generalized carious lesions of the primary molars (International Caries Detection and Assessment System classes four and five), as well as a prominent cusp extending from the palatal gingiva of the PMRCI. The palatal cusp extended to the incisal edge of the PMRCI and was in traumatic occlusion with the opposing permanent mandibular right central incisor.

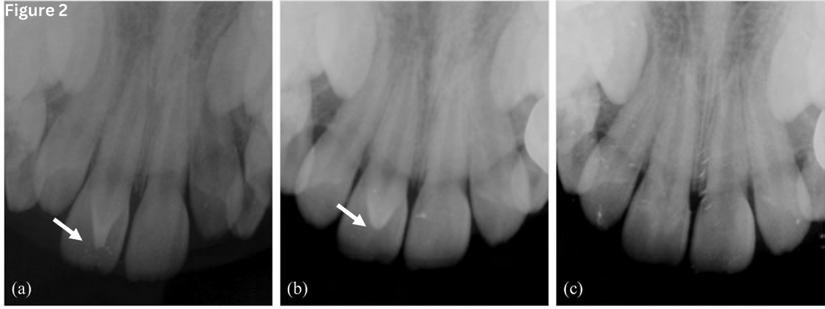

The permanent right maxillary central incisor was distally rotated and was approximately 2 mm less erupted than the partially erupted permanent maxillary left central incisor. The permanent right maxillary central incisor presented with a slightly increased overjet relative to the permanent left maxillary central incisor. Figure 1a shows the patient at initial new patient examination with occlusal interferences. Radiographic examination shows a radiopaque V-shaped structure arising from the cementoenamel junction of the PMRCI with what appears to be a slight extension of the pulpal tissue into the inner region of the V-shaped radiopacity (Figure 2a).

The patient reported symptoms consistent with reversible pulpitis in the areas of the carious posterior primary molars. The patient denied any symptoms involving the maxillary anterior teeth, but did complain of frequent trauma to the anterior tongue when eating.

Beyond addressing the patient’s symptomatic carious teeth, the providing dentist was also concerned with the occlusal interference and resulting malocclusion due to the TC of the PMRCI. Treatment options were provided and the decision was made to move forward with gradual reduction of the TC to minimize risk of pulpal exposure and to remove the source of occlusal interference and lingual trauma. Incremental reduction of the TC was planned to accompany appointments for simultaneous comprehensive dental rehabilitation of the carious dentition.

Roughly 1.5 mm to 2 mm of tooth structure was removed with a football-shaped fine diamond bur on a high-speed handpiece, with copious irrigation, at each visit roughly sixweeks to two months apart from each other. Local anesthesia was not administered in the area of the PMRCI, though a combination of 30% nitrous oxide (N2O) and 70% oxygen (O2) was utilized for TC reduction.

Figures 1b, 1c, 1d and 1e show the patient’s improving occlusion after each incremental 2 mm reduction, revealing the patient no longer with occlusal interferences and with improved eruption pattern and alignment of the PMRCI. Figure 2b also reveals the radiographic appearance of the PMRCI roughly halfway through the treatment protocol after two incremental reductions of the TC were complete, with no signs of radiographic pathosis. Five percent topical sodium fluoride varnish was applied locally to the reduced TC after each visit to minimize tooth sensitivity.

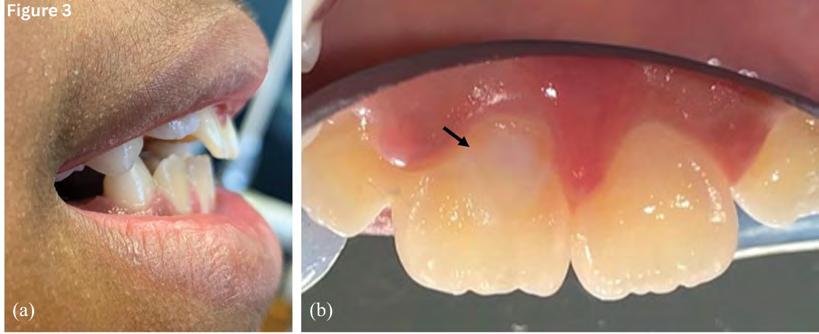

Figure 3a shows the patient after complete reduction of the TC with no occlusal interferences and improved overbite and overjet relationship. The lingual surface of the PMRCI was sealed after the fifth and final reduction to ensure a sealed and smooth surface (Figure 3b). Total time of treatment was roughly eight months.

Figure 1e illustrates the patient’s occlusion one month after final TC reduction. The patient was asymptomatic at this visit and no signs or symptoms of pulpal inflammation or sensitivity were noted. Further eruption of the PMRCI was observed after removal of the interference. The patient also reported no additional trauma to the tongue following removal of the patient’s TC. A radiograph was taken to confirm no pathosis (Figure 2c). Subsequent clinical and radiographic examination revealed no adverse signs or symptoms of the permanent right maxillary central incisor, and the patient was recommended for sixmonth routine oral hygiene maintenance visits.

Discussion

Though the precise etiology of dens evaginatus is unknown, TCs are a rare odontogenic malformation that are thought to result from environmental or genetic factors during the morphodifferentiation phase of tooth development.[5,6] TCs are also associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome, RubinsteinTaybi syndrome, Mohr syndrome, incontientia pigmenti achromens, Ellis Van Creveld syndrome and BerardinelliSeip syndrome.[7] Environmental factors (i.e., trauma or ectopic tooth positions) that could interfere with the morphodifferentiation stage of tooth development or genetic components are also suspected to be an associated factor in the etiology of TC presentations. The patient in the present case, however, had none of the above-mentioned syndromes, no known environmental stress at the time of morphodifferentiation and no known family history of TC.

Hattab et al., in 1995, evaluated and categorized the features of TCs into three distinct subtypes based on the degree of cusp formation and extension.[8] Type 1, also known as a TC, consists of a well-defined, exaggerated accessory cusp-like structure projecting from the palatal surface to at least half the distance between the cementoenamel junction and the incisal edge of the affected tooth. Type 2, also known as a semi-TC, characterizes a dental tubercle that is greater than 1 mm in size, but extends less than half the distance from the cementoenamel junction to the incisal edge. Type 3, also known as a trace TC, is a diffuse and not well-delineated enlargement of the cingulum that may have a conical, bifid or tubercle-like appearance.[8]

TCs may be unilateral or bilateral, in primary or permanent dentition, and can affect both males and females. It is rarely present in mandibular teeth, and rare on the facial surfaces. According to Decaup et al., TCs occur in approximately 1.67% of the population.[2]

The patient in the reported case presented with occlusal interference secondary to the prominent Type 1 TC. Occlusal interferences produce injury to the periodontium and pulp, which can cause tooth mobility, tooth displacement, temporomandibular joint pain, pain on mastication and periodontal disease.[9] There is also increased risk for caries development with the additional grooves present and an increased risk of fracture of these accessory structures. Early diagnosis and treatment of occlusal interferences can help prevent associated signs and symptoms.

Many treatment modalities are discussed in the literature depending on the size and disturbance(s) created by each TC. Gradual reduction of a TC is a safe, conservative and effective treatment for problematic TCs. Other proposed treatment modalities include pit and fissure sealants, pulpal therapy, restorative treatment, full-coverage crowns, extraction or no treatment.[9,10] Treatment should be determined only after careful evaluation of the size and configuration of each TC, as well as after in-depth discussions with patients and parents to assess the optimal approach for each individual.

Little information is known about TC anatomy and how the pulp communicates with the main chamber.[11] Due to concern for pulpal extension, gradual reduction of the affected cusp was considered the best treatment option for this patient. With gradual reduction, reparative or tertiary dentin is allowed adequate time to form between treatments. The tertiary dentin is formed by odontoblasts in response to a stimulus (i.e., manual reduction of the TC with a high-speed handpiece).[12]

According to Stanley et al.,[13] the average rate of tertiary dentin formation is 1.49 um/day and is highest in the interval between 27 to 48 days. By waiting six to eight weeks between cusp reductions, the provider allowed for sufficient tertiary dentin formation prior to subsequent reduction, to avoid iatrogenic pulp exposure.

Early diagnosis and intervention were instrumental in eliminating this patient’s occlusal interference, which if left untreated, could have progressed to more extensive malocclusion and irreversible pulpal and periodontal harm. This case report supports the use of gradual reduction as a safe and effective treatment for TCs. It is a minimally invasive procedure that can successfully relieve symptoms with nominal preparation of the tooth and no local anesthetic. This is particularly important for dentists who may be among the first oral health providers to identify TCs in young patients and for whom cooperation and possibility of continued growth and development may make full coverage crowns difficult.

All authors have made substantive contribution to this case report and all have reviewed the final paper prior to its submission. Queries abut this article can be sent to Dr. Lesavoy at bretlesavoy@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

1. Kalpana R, Thubashini M. Talon Cusp: a case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2015;6(1):594-96.

2. Decaup PH, Garot E, Rouas P. Prevalence of talon cusp: systematic literature review, metaanalysis and new scoring system. Arch Oral Biol 2021;125:105-112.

3. Yoon RK, Chussid S. Dental management of a talon cusp on a primary incisor. Pediatr Dent 2007;29(1):51-5.

4. Mellor JK, Ripa LW. Talon cusp: a clinically significant anomaly. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1970;29:225-8.

5. Babaji P, Sanadi F, Melkundi M. Unusual case of a talon cusp on a supernumerary tooth in association with a mesiodens. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects 2010;4(2):60-3.

6. Sharma G, Mutneja AR, Nagpal A, Mutneja P. Nonsyndromic multiple talon cusps in siblings. Ind J Dent Res 2014;5(2):272-74.

7. Davis PJ, Brook AH. The presentation of talon cusp: diagnosis, clinical features, associations and possible aetiology. Br Dent J 1986;160:84-88.

8. Hattab FN, Yassin OM, al-Nimri KS. Talon cusp in permanent dentition associated with other dental anomalies: Review of literature and report of seven cases. J Dent Child 1996;63:368-78.

9. Saravanan R, Babu PJ, Rajakumar P. Trauma from occlusion: an orthodontist’s perspective. J Indian Soc Periodontol 2010;14(2):144-145.

10. Liu JF, Chen RJ. Talon cusp affecting the primary maxillary central incisor in two sets of female twins: report of two cases. Pediatr Dent 1995;17:362-4.

11. Tsai AI, Chang PC. Management of talon cusp affecting the primary central incisor: a case report. Chang Gung Med J 2003;26:678-83.

12. Smith AJ, Cassidy H, Perry H, Begue-Kirn C, Ruch JV, Lesot H. Reactionary dentinogenesis. Int J Dev Biol 1995;39:273-80.

13. Stanley HR, Conti AJ, Graham C. Conservation of human research teeth by controlling cavity depth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1975;39:151-6.

Bret Lesavoy, D.M.D., is a private practitioner in Pennsylvania. He is a former postdoctoral residency fellow (in pediatric dentistry), Columbia University Medical Center, Pediatric Dentistry Division, College of Dental Medicine, New York, NY.

Richard Yoon, D.D.S., is associate professor of dental medicine (in pediatric dentistry) at Columbia University Medical Center, Pediatric Dentistry Division, College of Dental Medicine, New York, NY.